AS ISLANDERS WE ARE VERY aware of our sea-cliffs. The white cliffs of Dover have long been symbolic of England to the returning traveller. Anyone who has been to the west of Ireland (or who saw the film Ryan’s Daughter) will have carried away memories of spectacular cliff scenery (Fig. 316). The sea-cliffs of Wales and southwest England are no less spectacular, and we are constantly reminded on television of the magnificent sea-bird cliffs of the Scottish islands. Sea-cliffs are where land and sea come closest together. Their vegetation is distinctive, not particularly rich in species but sometimes kaleidoscopic in its variety within a small space.

THE MARITIME CLIFF HABITAT

Salt spray, plant growth and vegetation

Sea-cliffs are close to the breaking waves, and many of our west-coast cliffs overlook dramatically rocky, wave-beaten shores. Wave-wash reaches higher than high water of spring tides and wave-splash higher than that. Both reach highest in exposed situations, and in stormy weather. Beyond the reach of wave-splash, fine sea-spray is carried to higher levels and farther inland. Where low cliffs face open ocean, as on the coast of the Burren or locally on the west Cornish coast there is what could be described as a ‘perched saltmarsh’ behind the cliff edge. In the Burren, this is dominated by red fescue (Festuca rubra) with halophytes including thrift (Armeria maritima), distant sedge (Carex distans), sea-milkwort (Glaux maritima) and sea plantain (Plantago maritima) along with such common grassland plants as creeping bent (Agrostis stolonifera), buck’s-horn plantain (Plantago coronopus) and white clover (Trifolium repens). These ‘saltmarshes’ may owe as much to impermeable soil and waterlogging as to salinity. Often, vegetation comparable with this is fragmentary, and more or less halophile species are scattered above high tide mark, frequently where there is a little fresh-water seepage. Apart from obvious halophytes, brookweed (Samolus valerandi), slender club-rush (Isolepis cernua), long-bracted sedge (Carex extensa) and the rarer dotted sedge (Carex punctata) often occur in situations like this.

FIG 316. The Cliffs of Moher, Co. Clare, July 1971. Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus) in the foreground; sea campion (Silene uniflora), bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) and thrift (Armeria maritima) to the left. Roseroot (Sedum rosea) can just be glimpsed to the right of the Silene.

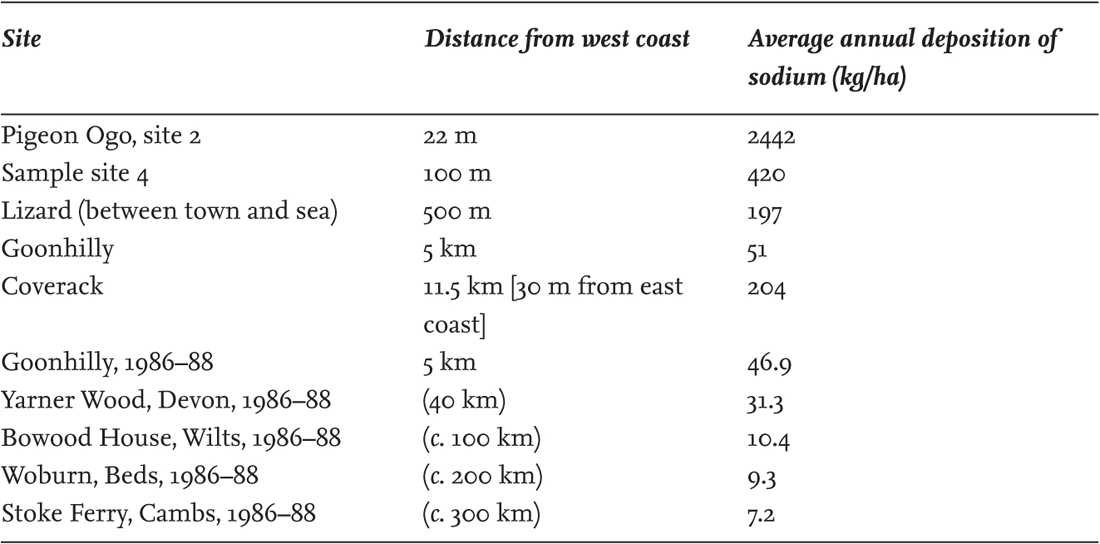

Most of the cliff is affected by only the finer spray, and sea-salt deposition declines rapidly with height above sea level, and distance inland. Table 13 shows the deposition of sodium at sites across the Lizard peninsula of Cornwall over two years at the end of the 1960s, with some comparative figures across southern England for 1986–88. As would be expected, deposition is very much higher on the west coast than the east; the Lizard measurement site, 500 m from the west coast, received almost as much sodium as Coverack, only 30 m from the sea on the east side. Much higher deposition was recorded close to the west-coast cliffs. At both Lizard and Coverack windspeed had a marked effect. Deposition of sodium averaged around 15 kg per hectare per day in periods with around 20% windy days (windspeed > 14 m/s), and only a third of that in periods with < 10% windy days.

TABLE 13. Annual deposition of sodium at some sites on the Lizard peninsula estimated from measurements, January 1968–April 1970 (Malloch 1972), with average wet deposition in 1986–88 at some sites across southern England for comparison (UKAGAR 1990). The Lizard transect started at the edge of the cliff 67 m above sea level at Pigeon Ogo, north of Kynance. (The distances given for sites east of the Lizard are rough indications of distance to the nearest open ocean coast to the southwest.)

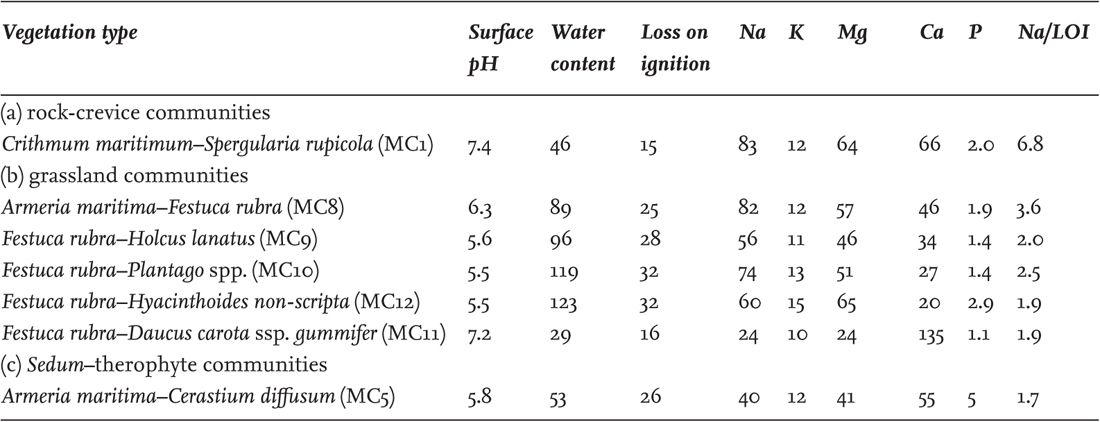

In terms of vegetation, red fescue–thrift (Festuca rubra–Armeria) maritime grassland often received an average of more than 10 kg/ha of sodium per day. Red fescue–cock’s-foot–Yorkshire-fog maritime grassland farther from the sea averaged c. 1.5–5 kg/ha per day, and cliff-top heather–spring squill (Calluna–Scilla verna) heath c. 1 kg/ha per day. However, daily deposition is very variable, and what matters most in the long run for plant growth is the amount of salt in the soil. Table 14 summarises some representative soil-analysis data for cliff grasslands.

Wind exposure

The prevailing winds over Britain and Ireland are southwesterly. All coasts are windier than inland, and exposed sites on the west coast are very windy indeed. This has striking effects on the vegetation, with short wind-clipped turf on exposed west-facing cliff edges, and blackthorn scrub in gullies or around outcrops looking as if it has been sculpted with a hedge-trimmer. Even several kilometres inland trees lean away from the wind. Wind probably affects plant growth more by increasing the rate of water loss and cooling the growing-points than by mechanical damage. Low-growing and prostrate forms of many species are common on exposed sea-cliffs. Sometimes these are just a plastic response of the plant to the harsh environment, but a number have been shown by cultivation experiments to be genetically fixed ecotypes or subspecies, some distinctive enough to be given formal names, such as the prostrate broom (Cytisus scoparius ssp. maritimus), which occurs on exposed cliff-tops in Devon, Cornwall, Wales, the Channel Islands (Fig. 323) and two sites in Ireland, and the corresponding form of dyer’s greenweed (Genista tinctoria ssp. littoralis) in wind-clipped turf on Devon and Cornish cliffs (Fig. 317). Many plants of such habitats are always prostrate; examples are hairy greenweed (Genista pilosa; Cornwall, Pembrokeshire plus a few inland sites), fringed rupturewort (Herniaria ciliolata; Lizard, Alderney) and such common species as wild thyme and buck’s-horn plantain. The intense exposure to wind relieves them of the competition of taller-growing plants, and they are able to take advantage of the few centimetres of more congenial microclimate close to the ground. The effect of wind is often obvious at a larger scale too. In general, on the south coast of Alderney and Guernsey (Fig. 318), gorse is dominant on the crests and exposed faces of the headlands, while bracken is dominant on the less exposed slopes. Blackthorn occurs in areas less exposed again within the bracken, but these are far from being sheltered in any absolute sense, and the blackthorn is often severely wind-cut. The picture is similar on the south Devon cliffs.

TABLE 14. Average characteristics of the soils of some sea-cliff plant communities, summarised from Rodwell (2000). Water content and loss on ignition (a rough measure of organic matter) are expressed as per cent air-dry soil; ions are expressed in ¼equiv/g air-dry soil. The ratio of sodium to organic matter (last column) is a more realistic measure of effective soil salinity than the sodium figure alone. (Cations determined in M ammonium acetate, and phosphate (H3PO4–) in acid 0.03 M ammonium fluoride extract.)

FIG 317. The west coast of the Lizard, Cornwall, looking northwest from near Kynance; thrift (Armeria maritima), sea beet (Beta vulgaris ssp. maritima), dyer’s greenweed (Genista tinctoria ssp. littoralis) and wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus) in the foreground. June 1995.

FIG 318. Common gorse (Ulex europaeus) alternating with wind-trimmed blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) scrub, leafless at this time of year, on the south coast of Guernsey, April 2010.

Aspect: sun and shade

Aspect – the compass direction a cliff faces – is no less important on sea-cliffs than inland. South-facing cliffs are warmer and drier, and it is here that southern species are usually found. Toadflax-leaved St John’s-wort (Hypericum linariifolium) and purple gromwell (Lithospermum purpureocaeruleum) have their maritime occurrences with us on the south coast, the moss Grimmia laevigata grows on sunny south-facing rocks on the south Devon cliffs, and there are countless other examples. Bluebells, common on cliff-slopes in the west, are densest and most luxuriant on northerly aspects. Bryophytes too are generally most luxuriant on north-facing slopes. Sea spleenwort (Asplenium marinum) is at its best with a degree of shade, and the same is true of the salt-tolerant moss Schistidium maritimum towards the southern end of its range.

ZONATION ON SEA-CLIFFS AND ROCKY SHORES

Life between the tidemarks and the splash zone: the province of seaweeds and lichens

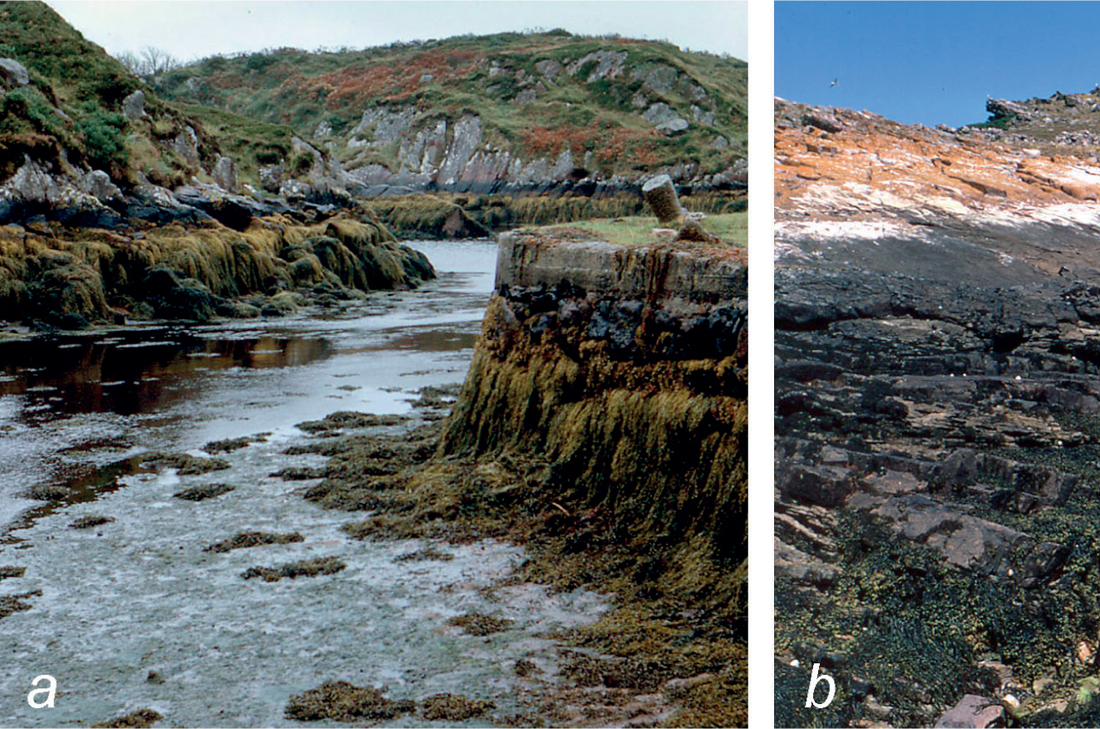

On rocky shores the only plants that can get a foothold between the tidemarks are seaweeds and lichens. At the lowest levels on the shore, around low water of spring tides, kelps dominate almost everywhere – big brown seaweeds (mostly species of Laminaria) forming submarine forests of flexible fronds that can be a metre or more in length. The kelps often shelter a rich flora of delicate feathery red seaweeds. The shore between low water and high water of neap tides is uncovered and covered again at every tide and takes the full force of the waves. Where there is some degree of shelter this zone in dominated by another group of brown algae, the wracks, species of Fucus and their relatives. Serrated wrack (Fucus serratus) commonly dominates the lower part of the intertidal zone, replaced by bladder-wrack (F. vesiculosus) higher on the shore. In sheltered places knotted wrack (Ascophyllum nodosum) covers the rocks (Fig. 319a). This zonation is topped off by a zone of Fucus spiralis, and a narrow fringe of Pelvetia canaliculata wetted only by spring tides. On wave-exposed shores, the fucoids become stunted and sparser, letting in smaller leathery red seaweeds such as Chondrus crispus (carrageen) and Gigartina stellata, until on very exposed shores most of the intertidal zone is left to barnacles, a few small tough red seaweeds like Laurencia pinnatifida and Corallina officinalis, and a few lichens (Fig. 319b). Of these, Lichina pygmaea looks like a tiny black seaweed a few millimetres high; Verrucaria maura grows in smooth black tar-like patches that form a dark zone visible from a distance around high tide mark – giving a graphic demonstration of how much higher wave-splash reaches on exposed headlands than on sheltered shores.

FIG 319. (a) Rocky-shore zonation in a sheltered inlet on the Donegal coast, September 1965. Wave-splash is minimal here. The middle shore is occupied by fucoid seaweeds (see text). The black Verrucaria zone above the seaweeds is narrow, soon giving way to predominantly grey lichens, and grassy and heathy vegetation. (b) A more exposed shore on Burhou, Channel Islands, July 1969. The seaweeds are much less prolific, the black Verrucaria zone is wider, there is a broad zone of predominantly yellow lichens below the grey-lichen zone, and the whole (small) island is affected by salt-spray deposition (see Fig. 326).

Once above the level regularly wetted by spring tides, terrestrial lichens begin to colonise the top of the black Verrucaria zone – first the dull yellow Caloplaca marina, then several bright orange-yellow species, including the common foliose Xanthoria parietina and the neat crustose thalli of Caloplaca flavescens (Fletcher 1973a, 1973b). These pass upwards into a zone of predominantly greyish lichens, some crustose, some fruticose (shrub-like). The commonest of these, Ramalina siliquosa, often forms a shaggy covering on rocks facing the sea. We are now in the region where flowering plants – thrift, plantains, rock samphire – and even a few mosses can become established.

Rock-crevice vegetation

The Earl of Gloucester and his son Edmund in Shakespeare’s King Lear stood above a cliff near Dover:

How fearful and dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low! The crows and choughs that wing the mid-way air, show scarce as gross as beetles. Half-way down, hangs one that gathers samphire – dreadful trade!

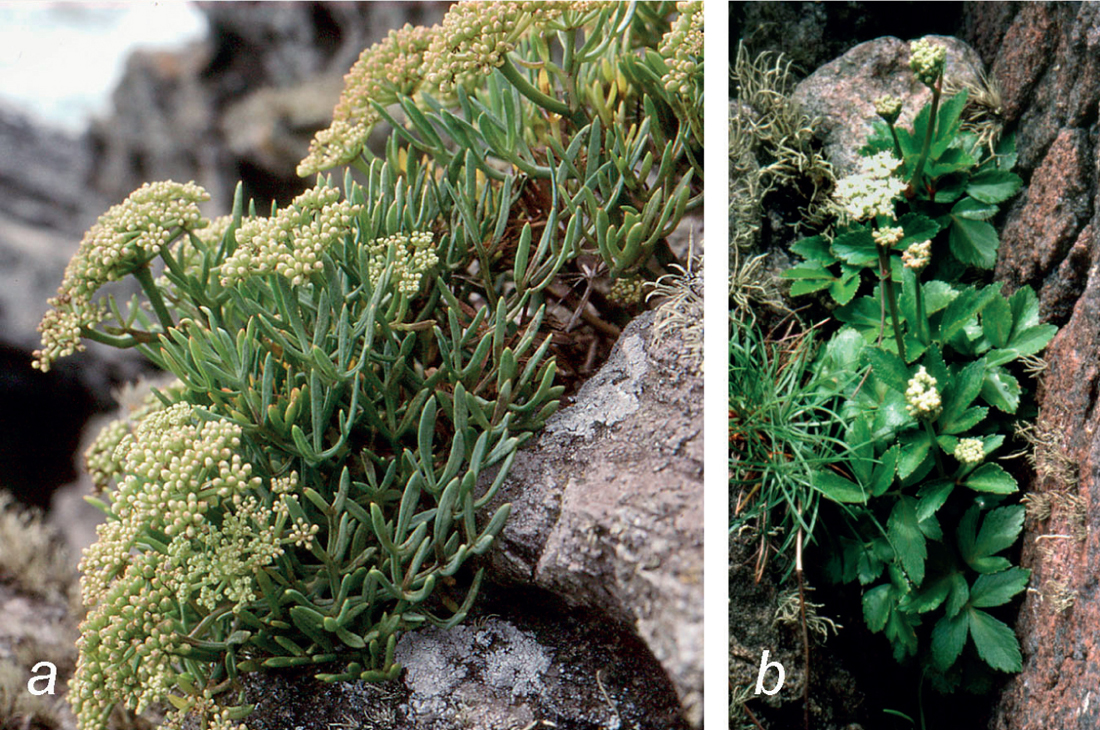

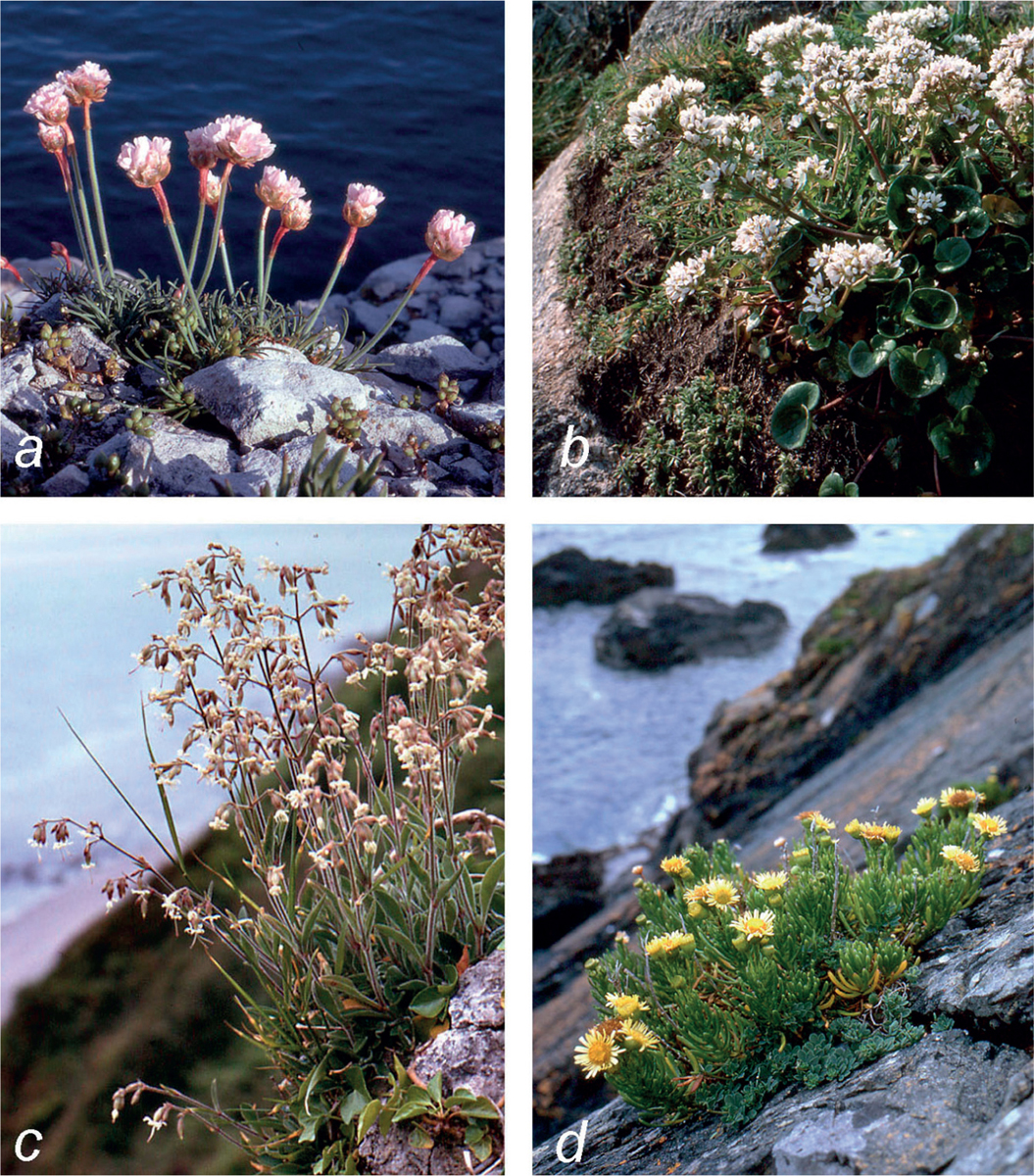

Rock samphire (Fig. 320a) is one of the most characteristic plants of the common rock-crevice community of the south and west coasts of England and Wales, and the southern coast of Ireland. It occurs over a wide range of levels, from cliffs and rocks on the shore just above the zone of wave-splash to high on the cliffs; by no means all the places it grows are ‘dreadful’ in the old literal sense of ‘dread-inspiring’. Rock samphire is often accompanied by thrift, red fescue and rock sea-spurrey (Spergularia rupicola). The only other plants that are at all common, and that only locally, are sea plantain, sea aster (Aster tripolium), golden-samphire (Fig. 321d), common scurvygrass (Fig. 321b) and rock sea-lavender (Limonium binervosum sensu lato)MC1. It is surprising that several of these cliff plants seem to be more frequent on the south and east coasts of Ireland than in the west. A few other species occur occasionally, including sea mayweed (Tripleurospermum maritimum), sea campion (Silene uniflora), sea fern-grass (Catapodium marinum), curved hard-grass (Parapholis incurva), sea spleenwort and, on acid rocks from Cornwall and Devon northwards, Schistidium maritimum, one of our few halophytic mosses.

FIG 320. Maritime rock-crevice plants. (a) Rock samphire (Crithmum maritimum), common round much of the coast of England, Wales and Ireland. Prawle Point, Devon, August 1987. (b) Scottish lovage (Ligusticum scoticum), which replaces Crithmum on the west coast of Scotland north of Galloway. Scourie, Sutherland, June 1981.

Rock samphire is conspicuously absent from the east coast of Britain north of Suffolk, and almost absent from the west coast of Scotland north of Galloway and Ayrshire. It occurs all round the coast of Ireland (except Mayo?), but is commonest in the southern half of the country. Around the whole Scottish coast and on the extreme north coast of Ireland its place is largely taken by Scottish lovage (Fig. 320b), which occupies much the same range of habitats. Lovage characterises the common rock-crevice community of the north and west Scottish coast; its constant (or near-constant) companions are thrift (Fig. 321a), red fescue and the moss Schistidium maritimumMC2. Frequent associates are sea plantain, sea campion, sea mayweed, common scurvygrass and roseroot (Figs 316, 322b). Rock sea-spurrey reaches only the southwest corner of the Scottish coast and the southern Hebrides, so it is not widespread in this community, and this area of Scotland and the adjacent northern Irish coast form a zone of transition between this community and the last.

FIG 321. (a) Thrift (Armeria maritima) in flower and Danish scurvygrass (Cochlearia danica) in fruit on the edge of a Purbeck limestone cliff, Winspit, Dorset, May 1970. (b) Common scurvygrass (Cochlearia officinalis), Lamorna, Cornwall, April 1980. (c) Nottingham catchfly (Silene nutans), Branscombe, Devon, June 1966. (d) Golden-samphire (Inula crithmoides), Annestown, Co. Waterford, August 1974.

Cliff-tops and ledges

Some conspicuous plants have their main habitat on the ledges and edges of sea-cliffs. Wild cabbage (Brassica oleracea) is particularly a plant of chalk and limestone cliffs, but it grows on other rock types in Devon, Cornwall and elsewhere. It is usually accompanied by red fescue, cock’s-foot (Dactylis glomerata), sea beet (Beta vulgaris ssp. maritima) and sea carrot (Daucus carota ssp. gummifer); thrift and cleavers (Galium aparine), groundsel (Senecio vulgaris) and the annual grass Bromus hordeaceus ssp. ferronii are other frequent associatesMC4. In some places, the community intergrades with chalk or limestone grassland, lacking sea beet and thrift, but including such species as common restharrow (Ononis repens), knapweeds (Centaurea nigra and C. scabiosa), Nottingham catchfly (Fig. 321c), kidney vetch (Anthyllis vulneraria), ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) and wood sage (Teucrium scorodonia). Several of the commonest plants of this community are calcicole and southwestern in their distribution in Britain, and are sparse or absent in Ireland. There, their place is filled by the ubiquitous maritime plants, sea beet, sea campion, thrift and red fescue.

In northern Scotland and the Scottish islands cliff ledges may be colonised by plants drawn from the rock-crevice community on the one hand, and cliff grasslands on the other, with constant red fescue, thrift, roseroot, common sorrel (Rumex acetosa), frequent Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus), ribwort and sea plantains (Plantago lanceolata and P. maritima) and occasional sea campion, creeping bent, lovage, wild angelica (Angelica sylvestris), red campion (Silene dioica), sea mayweed and primrose (Primula vulgaris)MC3.

Maritime grasslands

Most sea-cliffs have some grassland in their vegetation, and ‘grassland’ implies soil, not just bare rock. The bulk of the herbage in these grasslands is made up of a very limited range of species: red fescue, Yorkshire-fog, cock’s-foot and creeping bent amongst the grasses, and the broad-leaved herbs thrift, sea carrot, buck’s-horn plantain, ribwort plantain, sea plantain, common sorrel, bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), white clover and common scurvygrass. These are the main ingredients. They are combined in various quantities and with various minor ingredients to make up what at first sight is a bewildering range of intergrading grasslands in which some noda (Chapter 4) can usefully be recognised but within which no sharp boundaries can be drawn. The zone nearest the sea is occupied by a species-poor but often luxuriant turf of red fescue and thrift. Both species are constant, but they vary greatly in relative proportions. The only other species that are at all common are creeping bent and sea plantain, but a notable rarity that occurs occasionally in this community is wild asparagus (Asparagus officinalis ssp. prostratus)MC8. With rather less maritime influence and with little or no grazing a much more varied Festuca rubra–Holcus lanatus grassland developsMC9. This is dominated by any one of red fescue, Yorkshire-fog, sea plantain and cock’s-foot, or some combination of these. The most frequent associated species are bird’s-foot trefoil, white clover, lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), common sorrel, cat’s-ear (Hypochaeris radicata), creeping bent and spring squill (western, but curiously, only on the east coast of Ireland). This grassland is exceedingly variable in moisture, aspect, shelter, degree of saline influence, nutrient status and no doubt past history, but defies formal subdivision. Some areas lean towards inland Festuca–Agrostis pasture (Chapter 16) or agricultural grasslands (Chapter 9), some have a heathy component, while some, with primrose, lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria), common dog-violet (Viola riviniana) and false brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum), show leanings towards scrub. Prostrate broom grows in very exposed sites, probably most often in what is essentially this community but close to the transition with the Calluna–Scilla verna heath discussed below.

This variable grassland, ankle-deep or somewhat more, grades into a much shorter grazed and wind-clipped maritime grassland in which the dominant red fescue is conspicuously accompanied by three species of plantain (buck’s-horn, ribwort and sea plantain). The only other species to occur with any regularity are creeping bent, thrift, eyebrights (Euphrasia spp.), common mouse-ear (Cerastium fontanum) and spring squill, and less commonly carnation sedge (Carex panicea), bird’s-foot trefoil, autumn hawkbit (Leontodon autumnalis), wild thyme and white cloverMC10. Many other species occur more sparsely, or in particular places. Praeger (1934) vividly describes how on Inishturk, 11 km off the west Galway coast, ‘The Plantago formation, here often composed of P. maritima and P. coronopus without any other ingredient, occupies a large area at the W of the island, as close and smooth as if shaved with a razor.’ This Festuca rubra–Plantago community and the Festuca rubra–Holcus lanatus grassland both occur from Land’s End to Shetland and the far west of Ireland, and they are to an extent interchangeable, but the Festuca–Holcus grassland predominates in southwest England and Wales (and, interestingly, on north-facing coasts in northern Scotland), while the Festuca–Plantago grassland predominates in northwest Scotland, northwest Ireland and the Hebrides.

Locally on deep, moist soils, generally on northerly aspects, a community occurs in which bluebell, red fescue, Yorkshire-fog and common sorrel are constant or nearly so, and dominate the ground – sometimes to the virtual exclusion of other plants, sometimes with a contingent of common maritime species and sometimes with a flora that recalls open woodland or a wood-margin but without shrubs or treesMC12. Species that occur in this facies include lesser celandine, cock’s-foot, hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium), bracken, brambles, primrose, common dog-violet, ivy and false brome. Vegetation of this kind is scattered in suitable spots from south Devon and Cornwall to Skye.

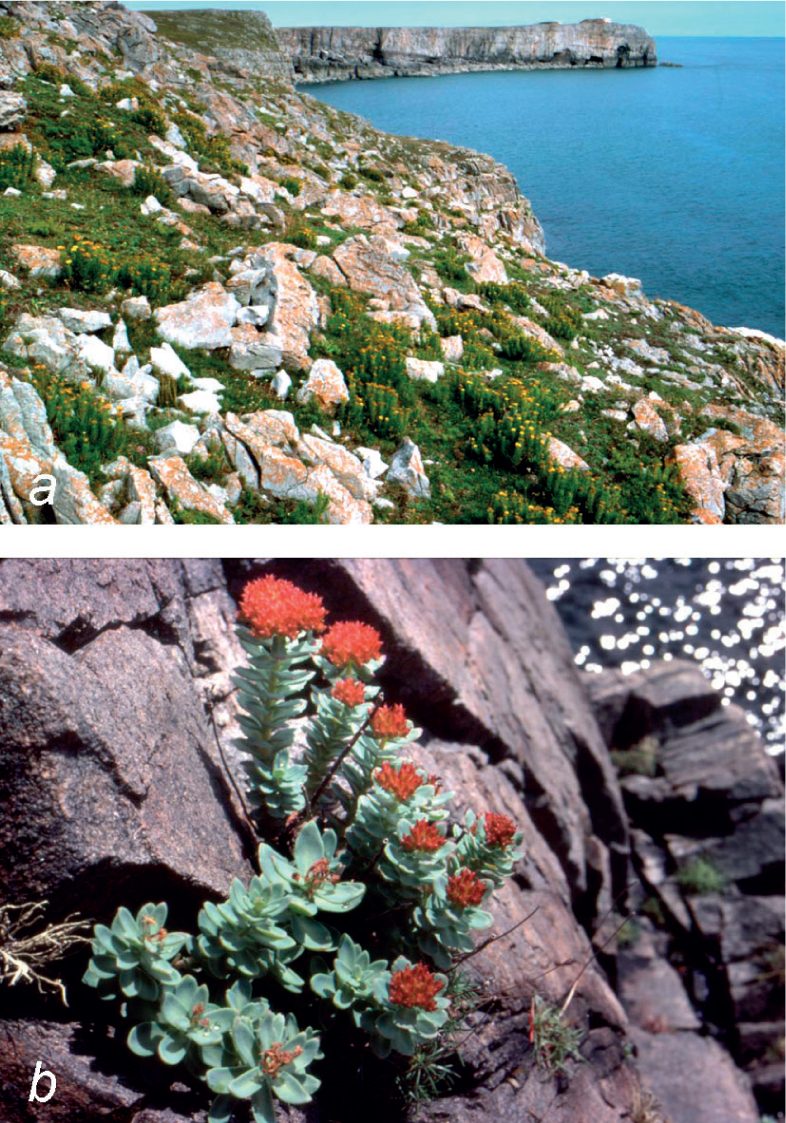

The maritime grasslands that we have considered so far cover most of the possibilities on the hard acid rocks that make up most of our coastal cliffs. Transitions between them (and their soils) are gradual, as is clear from Table 14. Chalk and limestone are different (Fig. 322). Calcium is the predominant ion in the soil, and the dominance of saline influence affects a narrower zone of vegetation on the cliff-top. Some maritime influence remains, but it is heavily diluted by the more calcareous character of the vegetation. Locally, a grassland is found on limestone cliffs dominated by red fescue, with constant cock’s-foot and sea carrot and frequent thrift, ribwort plantain, bird’s-foot trefoil and salad burnet (Sanguisorba minor)MC11. Buck’s-horn plantain, common restharrow, greater knapweed, lady’s bedstraw, kidney vetch, tor grass (Brachypodium pinnatum) and tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) also commonly occur. The maritime element in this hardly amounts to more than the constancy of sea carrot and the frequent presence of thrift and buck’s-horn plantain, but it is there. The affinity with inland calcareous grasslands is very plain, and apparent too in the soil data of Table 14. The red fescue–sea carrot community occurs on the Purbeck and Portland limestone cliffs, on the Carboniferous limestone of Gower and Pembrokeshire in South Wales, and sporadically elsewhere, probably where chalk or blown sand have created suitably calcareous soils. The community (unless redefined) cannot occur outside the range of the sea carrot. A poorly characterised grassland of similar maritime flavour along the west-coast Burren cliffs had constant red fescue, near-constant creeping bent, sea plantain and bird’s-foot trefoil, occasional thrift, and much in common with the neighbouring calcareous grasslands on limestone or boulder-clay.

FIG 322. Contrasting sea-cliffs. (a) Carboniferous limestone cliffs near St Govan’s Head, Pembrokeshire, with golden-samphire (Inula crithmoides), August 1977. (b) Roseroot (Sedum rosea) on a Lewisian gneiss sea-cliff at Scourie, Sutherland, June 1981.

Cliff-top heaths

On hard acid rocks heath often covers the cliff-tops and spurs and broken rocky ridges facing the sea. These heaths are variable amongst themselves, and intergrade with the more acid maritime grasslands: prostrate broom favours grassland–heath transitions on exposed cliffs (Fig. 323). Maritime heaths generally have many more constant or near-constant species than most inland heaths. Heather (Calluna vulgaris) and bell heather (Erica cinerea) are generally dominant. Other species of high constancy are sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina), sea plantain, spring squill, bird’s-foot trefoil, wild thyme, tormentil (Potentilla erecta), Yorkshire-fog, ribwort plantain and cat’s-ear; red fescue and common dog-violet are frequent. Like most cliff communities, this Calluna vulgaris–Scilla verna heathH7 is variable. The variant showing the strongest maritime influence has constant thrift and English stonecrop (Sedum anglicum), and frequent cock’s-foot, kidney vetch and sheep’s-bit (Jasione montana). What might be seen as the ‘central’ form of the community is characterised by near-constant common dog-violet and glaucous sedge (Carex flacca), with frequent common milkwort (Polygala vulgaris), spring-sedge (Carex caryophyllea), devil’s-bit scabious (Succisa pratensis) and heath-grass (Danthonia decumbens). A damp-heath version, with cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix) largely replacing bell heather, near-constant devil’s-bit scabious, heath-grass and common bent, and frequent common sedge (Carex nigra), sweet vernal-grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), red fescue and eyebright species, is common from Anglesey northwards and is the predominant form of the community in northwest Scotland and the Western Isles. A version with crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) largely replacing bell heather occurs in the north of Scotland. Species-poor stands with little beyond the basic list of near-constants can be found throughout the community’s range.

FIG 323. Prostrate broom (Cytisus scoparius ssp. maritimus) on the southwest cliffs of Alderney, with heathers and maritime grassland, in (a) April and (b) July. Notice the parasitic greater broomrape (Orobanche rapum-genistae), just starting into growth in April (bottom LH corner), but tall dry fruiting spikes by July amongst the dry flowering heads of thrift and Yorkshire-fog.

Open communities of (mostly) dry places: stonecrops, clovers and others

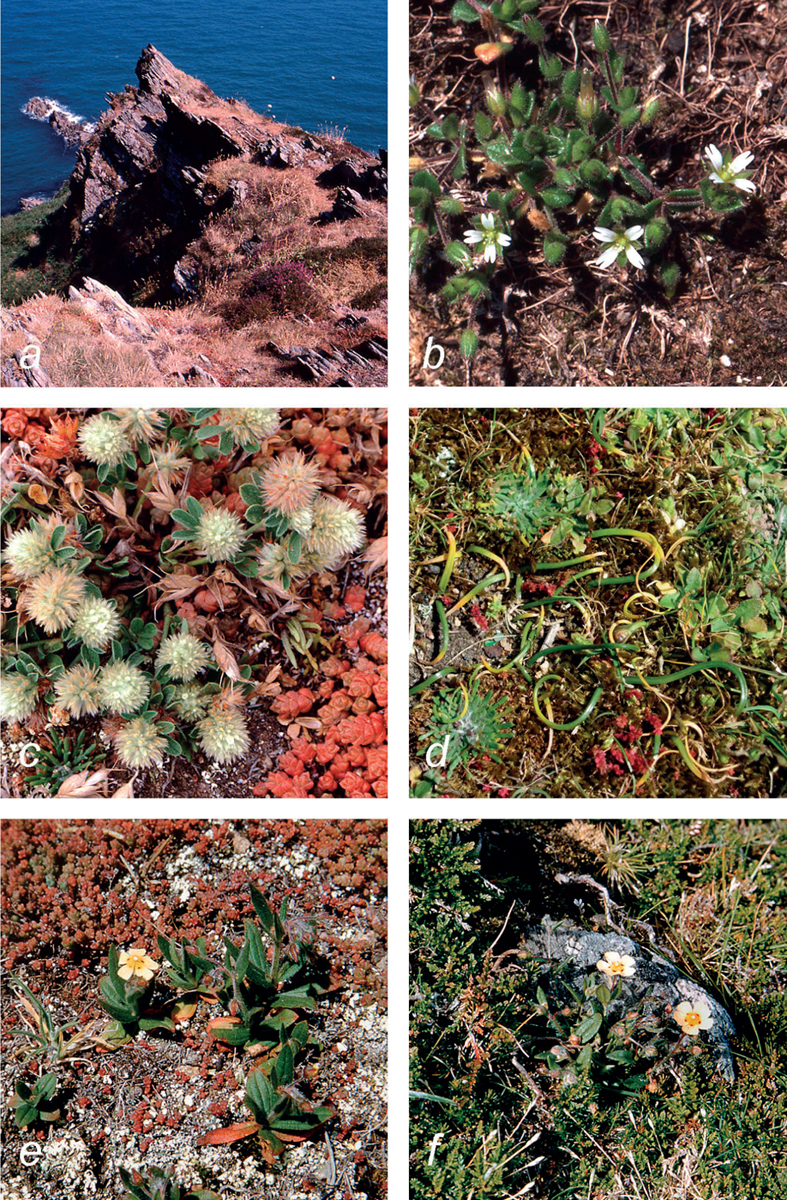

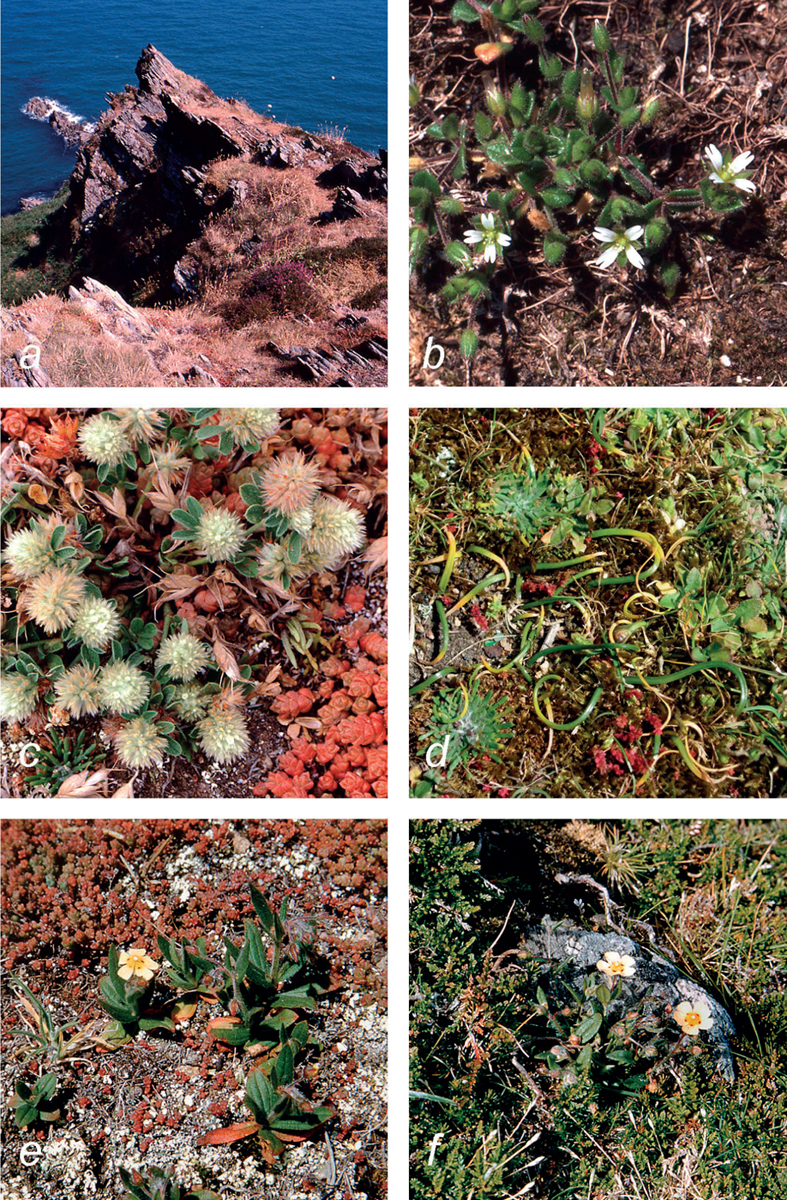

Thin soils on cliff edges, around rock outcrops or on sun-exposed stony slopes often bear low open vegetation, moist and green in winter and spring, largely brown, dry and shrivelled in late summer, in which small annuals are prominent. These communities are very diverse in species composition and ecological relationships.

Braun-Blanquet and Tüxen (1952) described a Plantago coronopus–Cerastium diffusum community from a rocky shore on Achill, low cliffs in the Burren and dunes at Rossbeigh (Kerry), and conjectured that it is common round the Irish coast. This appears to be a near match for part of the Armeria maritima–Cerastium diffusum communityMC5a in Britain. Thrift, buck’s-horn plantain (Plantago coronopus), red fescue, sea mouse-ear (Cerastium diffusum, Fig. 324b) and sea fern-grass are constant in the British community; sea fern-grass seems to have a slightly different but related niche in western Ireland, but the difference may be more apparent than real.

Braun-Blanquet and Tüxen also described from Ireland an ‘Aira praecox–Sedum anglicum association’, of shallow siliceous soils, not specifically bound to the coast. They saw this as related to a complex of communities distributed along the North Atlantic seaboard from mid Portugal north to Ireland and Britain – and probably southwest Scandinavia. In their 11 species-lists, early hair-grass (Aira praecox), English stonecrop (Sedum anglicum) and the moss Polytrichum juniperinum were constant, and silver hair-grass (Aira caryophyllea), squirreltail fescue (Vulpia bromoides), the moss Hypnum lacunosum and red fescue almost so. They found their community ‘particularly common in SW-Ireland, but also in the NW of the island’. It is the habitat of spotted rock-rose (Tuberaria guttata) in Ireland. Essentially the same community is common on coastal cliffs in the Channel Islands, where it is the habitat of sheep’s-bit, sand crocus (Fig. 324d), spotted rock-rose (Fig. 324e), four-leaved allseed (Polycarpon tetraphyllum), hairy bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus subbiflorus), hare’s-foot clover (Fig. 324c) and a number of rarer clovers and other annuals. It is also common on sea-cliffs and cliff-slopes in southwest England and Wales, but (as in Ireland) with a more restricted flora. This community spans a wide range of altitude (and salt deposition) on sea-cliffs. At low levels, where marine influence is greatest, most of the species of the Plantago coronopus–Cerastium diffusum community can occurcf. MC5c. At high levels on the cliffs the two communities have almost nothing in common.

FIG 324. Open communities of sea-cliffs. (a) Habitat, Outer Froward Point, near Dartmouth, Devon, July 1989. (b) Sea mouse-ear (Cerastium diffusum), Durness, Sutherland, June 1981. (c) Hare’s-foot clover (Trifolium arvense), English stonecrop (Sedum anglicum) and the annual grass Bromus ferronii, Alderney, July 1967. (d) Open community by cliff-top path near Le Gouffre, Guernsey, April 2010. Sand crocus (Romulea columnae) is several weeks past flowering; a developing seed-capsule can be seen near the centre of the picture but the curly leaves are already withered and pale brown. The broader leaves of autumn squill (Scilla autumnalis) are still green, though yellowing. Patches of reddish mossy stonecrop (Crassula tillaea) are prominent. (e) Spotted rock-rose (Tuberaria guttata) with English stonecrop and scattered small grasses, Alderney, April 1957. (f) Spotted rock-rose in bare patch in grazed and windcut heather, with early hair-grass (Aira praecox). Inishbofin, Co. Galway, August 1958.

There is a parallel community to this on limestone, with biting stonecrop (Sedum acre) replacing S. anglicum, and small annuals including thyme-leaved sandwort (Arenaria serpyllifolia) and often rue-leaved saxifrage (Saxifraga tridactylites). This too can appear associated with the Armeria maritima–Cerastium diffusum communityMC5d, or in association with other communities of limestone rocks and wallsOV39, OV42.

Although most of the annual clovers (and a number of other rare annuals) can appear occasionally in the Aira praecox–Sedum anglicum community, this is not their preferred habitat, which is something more extended and grassier – but still dry in summer. Many of these species are southern rather than southwestern plants in their European ranges. This shows up too in their distribution patterns within Britain; most have their centre of gravity in southeast England (good examples are Trifolium glomeratum, T. suffocatum and T. subterraneum), or in the southern half of the country (Ornithopus perpusillus, Moenchia erecta). These species seem to need a hot sunny summer, which probably accounts for their rarity in Ireland.

Orange bird’s-foot (Ornithopus pinnatus) grows with us only in short grassy turf in the Channel Islands and Isles of Scilly. Small hare’s-ear (Bupleurum baldense) and small restharrow (Ononis reclinata, Fig. 141b) grow in a few places, mostly on the south coast of Britain and in the Channel Islands. The most celebrated group of plants of this kind are the Lizard clovers. Three species, twin-headed clover (Trifolium bocconei), long-headed clover (T. incarnatum ssp. molinerii) and upright clover (T. strictum) are confined to the Lizard district of Cornwall or nearly so, where they grow along with all the other annual clovers of our flora. The Rev. C. A. Johns (author of the popular Victorian Flowers of the Field) visited the Lizard in 1848, and observed ‘I actually covered with my hat growing specimens of all together Lotus hispidus, Trifolium bocconi, T. molinerii, and T. strictum.’ The twentieth-century photograph (Fig. 325) shows that the Rev. Johns’s hat need not have been large!

The influence of seabirds

Seabirds and sea-cliffs go together, and the birds inevitably have an impact on the vegetation. The impact is most intense in and around the colonies of the gregariously nesting species, but the birds have a more diffuse influence too in manuring the cliff vegetation. The birds must be responsible for much of the nitrogen and phosphate in sea-cliff soils.

In the densest breeding colonies (gannets, cormorants) virtually nothing grows. Gulls and terns like a little more space, and there is generally room for some greenery between the nests. Species that nest in burrows (puffins, Manx shearwaters, petrels) need space between the burrows and vegetation is important to the stability of the ground, but it suffers a lot of trampling, manuring and traffic. Outside the nesting season, bird colonies are often obvious from their conspicuously luxuriant vegetation, and bird islands are often conspicuously green.

Compared with the general run of cliff grasslands, the maritime and ruderal plants are more conspicuous at bird-influenced sites. On the sunnier and more southern coasts of both Britain and Ireland, this shows itself in the abundance of oraches (Atriplex spp.), sea beet, sea mayweed and rock sea-spurrey (Fig. 326). The ubiquitous red fescue remains common, along with thrift, curled dock (Rumex crispus ssp. littoreus), cock’s-foot, knotgrass (Polygonum aviculare), sea stork’s-bill (Erodium maritimum) and common scurvygrass. A conspicuous and beautiful plant frequent in this community is tree-mallow (Fig. 327)MC6. Tree-mallow sometimes grows on exposed sea-stacks. One may wonder how such an apparently soft and vulnerable plant survives in a habitat where even red fescue is wind-cut. Much is possible for a quick-growing annual or biennial, which can take maximum advantage of the warm summer months, and does not have to ride out the full force of the chilly winter storms – perhaps an example of the relative métiers of r-selected and k-selected species.

FIG 325. Lizard clovers. Twin-headed clover (Trifolium bocconei), upright clover (T. strictum), knotted clover (T. striatum), rough clover (T. scabrum), slender trefoil (T. micranthum), lesser trefoil (T. dubium) and common restharrow (Ononis repens). Caerthillian Cove, Lizard, Corwall, June 1968.

FIG 326. Burhou, an uninhabited but seabird-frequented small island near Alderney, July 1969; dominant rock sea-spurrey (Spergularia rupicola) in flower, a patch of wall pennywort (Umbilicus rupestris) in the foreground and bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) in the middle distance. Little Burhou, just to the west, is covered with sea campion (Silene uniflora).

FIG 327. Tree-mallow (Lavatera arborea) on Devonian limestone. Berry Head, Devon, May 1983.

Sea beet, rock sea-spurrey and tree-mallow are all missing from much of Scotland and rather thinly distributed in northwest Ireland. Northwards, bird-influenced sites tend to be increasingly dominated by chickweed and grasses – creeping bent, Yorkshire-fog and red fescue – with thrift, common sorrel, sea plantain, common scurvygrass, curled dock, sea campion and spear-leaved orache (Atriplex prostrata)MC7. However, sites vary greatly with local conditions, and no doubt with the chance consequences of which plant happened to get there first.

Cliff scrub and woodland

The sheltered parts of sea-cliffs are open to colonisation by woody vegetation. Bracken is an occasional ingredient of the red fescue–bluebell grassland of sheltered cliff slopes, and in southwest England it is often prominent on cliff slopes that are not too exposed. Some of this bracken community at higher levels and on acid rocks is of the bracken–heath bedstraw type: essentially an upland Festuca ovina–Agrostis capillaris pasture with a bracken canopyU20. But some is more nearly related to scrub, with a thin understorey of bramblesW25, foxgloves, false brome and occasional low stunted bushes of blackthorn in a matrix of common cliff-grassland species. Bloody crane’s-bill (Geranium sanguineum) grows in vegetation of this general kind both on the Lizard and on hornblende–schist cliffs on the south Devon coast. In more sheltered places blackthorn can grow up to form a continuous scrubW22. On poor, acid soils, the most exposed ground is occupied by wind-cut heather, and where there is deeper soil and some moderation of the exposure patches of common gorse can developW23. The pattern of the main vegetation types on the south coast of Guernsey (Fig. 318) is repeated with variations in many places on the coast of southwest England, Wales and Ireland. Further development to cliff woodland returns us to Chapter 8.

CULTIVATED PLANTS, INTRODUCTIONS AND RUDERALS

Some our most-used vegetables originated on the coast. Sea beet and wild carrot are coastal plants, and wild cabbage on chalk and limestone cliffs is instantly recognisable by anyone who has ever grown or cooked one of its numerous cultivated varieties. Add to that basic list some more esoteric vegetables – asparagus, sea-kale, radish, celery, marsh samphire, fennel – and some that were eaten more in the past than now – rock samphire, scurvygrass, alexanders – and the list becomes quite impressive. Probably the succulence of many halophytes made them a natural choice as food plants. It is easy to see why our ancestors cultivated beet, with its fleshy roots, sweet in autumn (the winter store of sugar is used up by spring). It is less easy to see why man chose to cultivate carrot, with its much tougher woody roots, unless it was for their flavour. Wild celery (Apium graveolens) grows in the brackish upper fringe of the saltmarsh zonation, and its characteristic smell is one of the safest ways to recognise it (though a Dutch family camping in England had their holiday rudely cut short in hospital when they put hemlock water-dropwort, which does not occur in the Netherlands, in their stew). Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum) are generally acknowledged to be introductions, but in crop plants and weeds there is a fine line between ‘native’ and ‘introduced’. Useful plants were traded by prehistoric societies, and weeds went with them. Fennel has been in our gardens (and kitchens) since at least the eighteenth century; it has come into more general use as a vegetable in recent decades. Alexanders was formerly used as a potherb, but has found a congenial niche in our maritime ruderal flora; sometimes it is a major part of the vegetation of seabird islands. Fennel too is often encountered near the sea, where it joins the ruderal flora in which black mustard (Brassica nigra) is often prominent on cliff-tops by the sea. Silver ragwort (Senecio cineraria) is commonly naturalised on cliffs and cliff slopes in southern England; hoary stock (Matthiola incana) less often so. Both are west Mediterranean plants, introduced to English gardens in Tudor times and now naturalised with us. A more recent immigrant is the South African hottentot fig (Carpobrotus edulis), which sprawls over cliff slopes in the Channel Islands and southwest England. It has been in our gardens for several centuries, but was first recorded wild in 1886. Everyone notices its gaudy flowers, and many conservationists view its spread with apprehension. Are their fears justified? It contributes to the seaside ambience, as do slender thistle (Fig. 328), a generally accepted native, tamarisk (Tamarix gallica) from the west Mediterranean, and the Duke of Argyll’s tea plant (Lycium spp.) from China.

FIG 328. Slender thistle (Carduus tenuiflorus), a very characteristic seaside plant in Britain, less so in Ireland. Branscombe, Devon, June 1973.