THE CALCAREOUS GRASSLANDS are surely among our best-loved plant communities. Many of us must carry a picture in our minds of their short, springy, flowery turf, always well-drained underfoot, perhaps of the first wild orchids we found, or of blue butterflies, or of a favourite ‘bank whereon the wild thyme blows’ – though Shakespeare must have been thinking of other things in the rest of that passage from A Midsummer Night’s Dream! These are semi-natural grasslands in the sense that, apart from grazing, they owe nothing to deliberate agricultural intervention. They have not been cultivated, sown or manured, and all of their species have arrived by natural means. A century ago the chalk downs of the south and east of England were pasture, much of it unploughed since prehistoric times, and grazed mainly by sheep. Some inroads had been made on the extent of the pasture in the course of the nineteenth century, and more again during the two world wars, but at the end of the Second World War a surprising extent of the chalk grassland remained intact. After the war, society and farming were changing. The use of the downs as sheepwalk declined along with the rest of the labour-intensive rural economy of the earlier part of the century, and by 1950 large areas of chalk grassland were kept in being mainly by innumerable wild rabbits. The post-war drive for national self-sufficiency in food production led to the ploughing and conversion to arable of much of the flatter chalk country, and the advent of myxomatosis in 1953 and the ensuing crash in the rabbit population led to rapid invasion of hawthorn scrub over much of the rest. The picture has been similar on the Cotswolds and our other lowland limestones.

The story on the harder and older limestones of the north and west is rather different. Wider open spaces, together with hill-farming subsidies (and planning policies in the National Parks), kept sheep farming economically viable, so the limestone grasslands of the Derbyshire and Yorkshire Dales have changed less in either extent or character than their southern and lowland counterparts. In Ireland the move away from labour-intensive small-scale farming has been more recent, but anyone who has known the limestone country of the Burren over the last half-century cannot fail to be struck by the increase in hazel scrub in recent decades.

THE CALCAREOUS GRASSLAND HABITAT

Soils

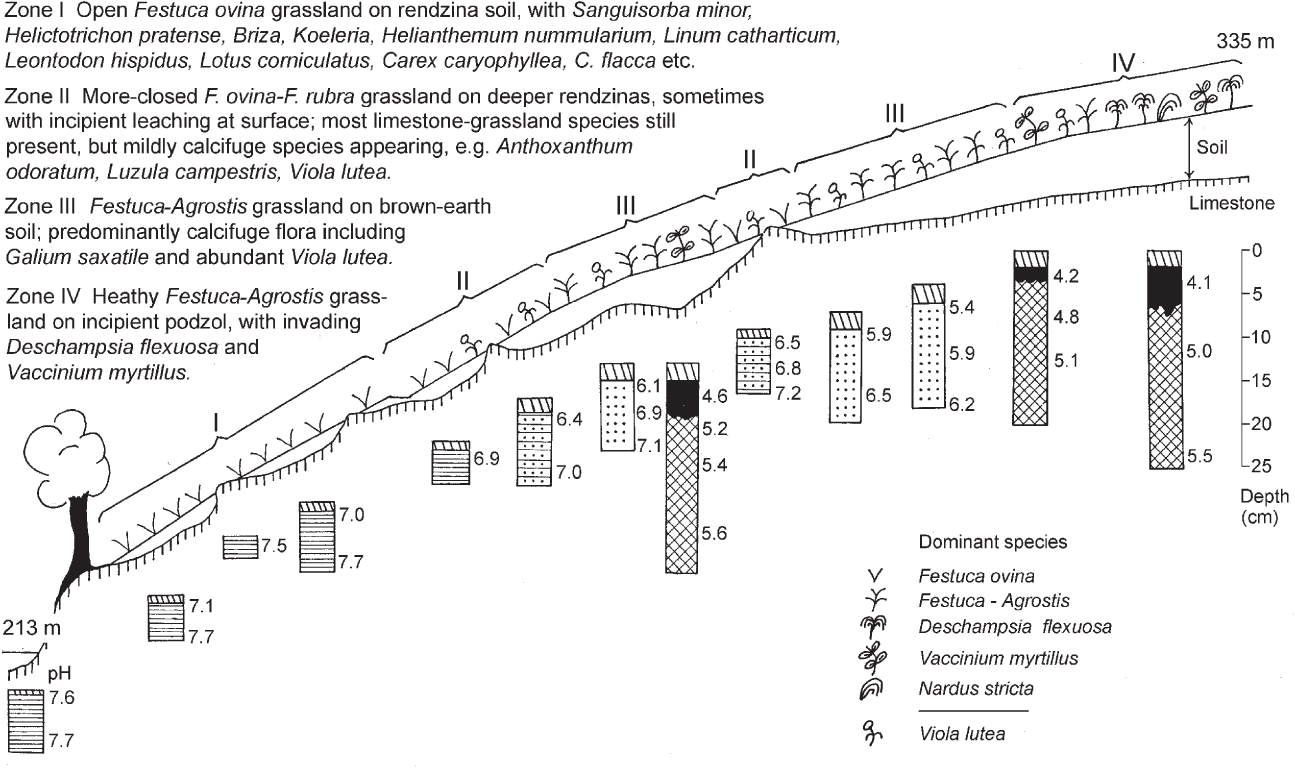

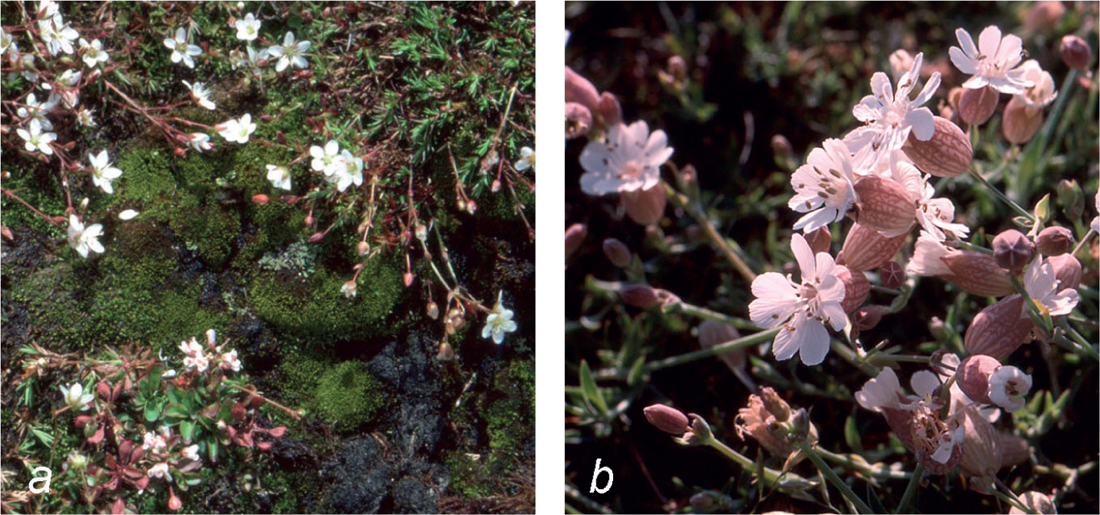

Calcareous grasslands do not occur everywhere that chalk or limestone bedrock appears on the geological map. This is because millennia of solution and soil-forming processes have left a layer of weathering residue covering the calcareous bedrock on any more-or-less level surface. Thus much of the chalk of southern England is overlain by a layer of ‘clay-with-flints’, to which may be added airborne loess deposited as dust in the cold periglacial landscape of the last ice-age. The chalk or limestone is only exposed as the parent-material of the soil on the slopes of escarpments and valleys where surface erosion has kept pace with soil-formation. Calcicole species such as squinancywort (Fig. 132a) and horseshoe vetch (Fig. 132b) map the major chalk and limestone escarpments with considerable fidelity. Calcareous grasslands most typically grow on rendzina soils, which have a near-neutral pH, are rich in calcium, but poor in available nitrogen and (especially) phosphate, and in which iron and other metallic trace elements are in relatively short supply. Often, limestone grasslands form part of a catena, a sequence of plant communities related to topography and repeated wherever similar topography recurs, with deep soils, sometimes leached and acid, on the plateau at the top, and fertile lime-rich soils as the slope levels off at the bottom (Figs 133, 134).

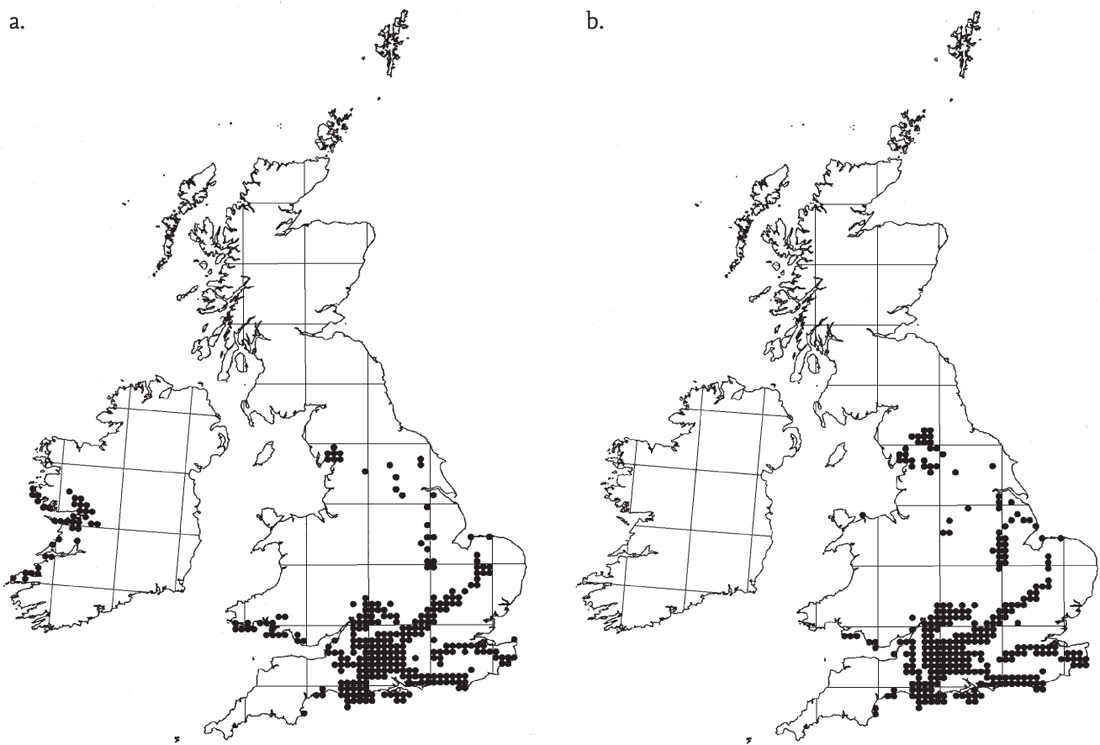

FIG 132. The distribution of (a) squinancywort (Asperula cynanchica) and (b) horseshoe vetch (Hippocrepis comosa). Both species are restricted to dry lime-rich rendzina soils. The southern part of their distributions reflects that of calcareous grasslands on scarp slopes and steep valley-sides on the chalk and the Jurassic, Permian and Carboniferous limestones. To the north and west their occurrences become more scattered. Both are on the limestone around the head of Morecambe Bay, but curiously both are rare or absent on the north Wales limestone. Horseshoe vetch reaches higher on the Carboniferous limestone in the Pennines, and squinancywort alone reaches Ireland, where it is common on the limestone of Clare and Galway, and in calcareous fixed-dune grasslands.

Chalk and limestone grasslands are well drained, and dry. It is an apparent paradox that many calcareous-grassland species – such as dwarf thistle (Fig. 135b), common rock-rose (Fig. 136a) and salad burnet (Fig. 136b) – are deep rooted, and transpire rapidly even under water stress. This is because in a short turf on a sunny day, with a kilowatt of solar energy beating down on every square metre, the surface and leaves close to it would become insupportably hot without transpirational cooling. The grasses, with their finer upstanding leaves, equilibrate more rapidly with the temperature of the air than the broad-leaved herbs close to the soil, so they are often shallow rooted and can restrict transpiration when water is short. Chalk, because of its porosity, provides a greater reserve of water than many other limestones.

FIG 133. Catena on Carboniferous limestone from Cressbrook Dale to Wardlow Hay Cop, Derbyshire. Horizontal shading in soil profiles, limestone rendzina; diagonal shading, surface root-mat and litter; stipple, brown earth; solid black, raw humus; cross-hatching, orange mineral soil of incipient podzol. After Balme, 1953.

FIG 134. Chalk escarpment near Batcombe, Dorset, June 1967. A catena comparable to that shown in Fig. 133. Rendzina soils with chalk grassland on the steep scarp slope, passing into deeper brown earths on the plateau above, bearing bracken and gorse. Cultivated farmland on the deep fertile soils at the foot of the scarp.

FIG 135. (a) The chalk cliffs between Lulworth and White Nothe, Dorset, August 1975. Tor grass (Brachypodium pinnatum) dominates large areas of chalk grassland along this coast. (b) Dwarf thistle (Cirsium acaule) in chalk grassland on Hambledon Hill, Dorset, August 1973.

FIG 136. Some characteristic chalk- and limestone-grassland plants: (a) common rock-rose (Helianthemum nummularium), Carreg Cennen, Carmarthenshire, May 1989; (b) salad burnet (Sanguisorba minor), Anvil Point, Dorset, May 1980: female plant in flower; (c) wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus), Cressbrookdale, Derbyshire, July 1973; (d) squinancywort (Asperula cynanchica), Box Hill, Surrey, July 1990.

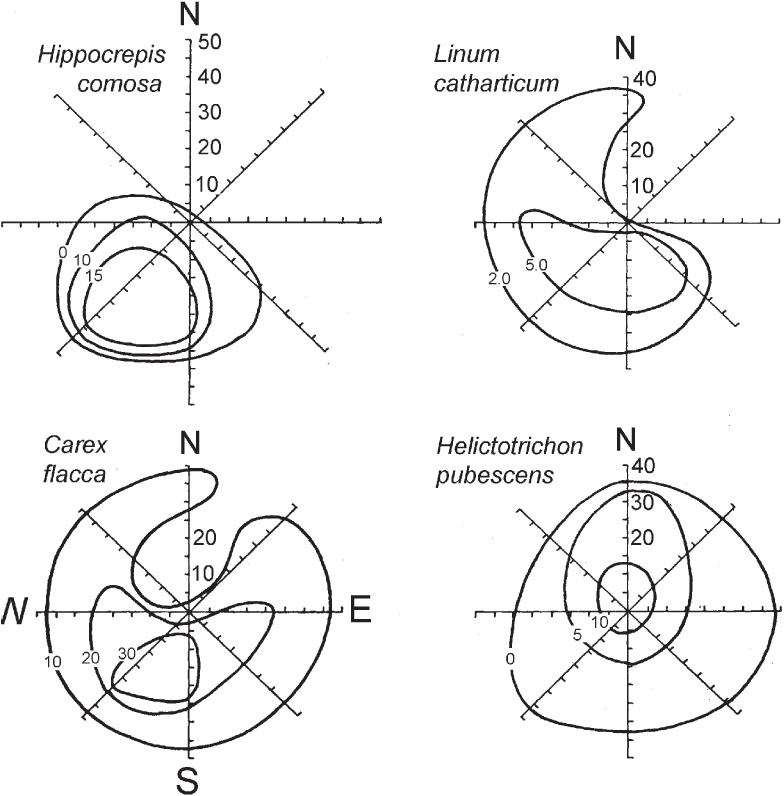

Slope and aspect

The steepness of the slope and the direction in which it faces have profound effects on the climate of a grassland on a hill in sunny weather (Fig. 8). In our latitude, the sun shines roughly at right angles to a 30° south-facing slope at noon in midsummer. At all other times the sun’s rays are more oblique to the surface. On a 30° slope facing north the angle of incidence will be just less than 30°. Consequently, solar radiation at noon will be about half as intense, partly compensated by longer hours of sunshine in the early morning and late evening. An east-facing slope will get its best sunshine in the morning while the air is still cool, and conversely on a west-facing slope sunshine is most intense when the air has already warmed through the day. With a less steep slope these effects are less pronounced. It is easy to see that a south (to west)-facing slope is likely to be most favourable for a southern species. We shall see in Chapter 17 that mountain corries with their arctic-alpine plants occur mostly on the north to east side of mountain summits. These effects are illustrated for a few calcareous grassland species in Figure 137. Horseshoe vetch (Hippocrepis comosa) shows a strong preference for southwest-facing slopes, fairy flax (Linum catharticum) and glaucous sedge (Carex flacca) also prefer slopes (chalky soils), but are less choosy which way they face. Downy oat-grass (Helictotrichon pubescens) favours flattish ground (deeper soils), with some preference for a northerly aspect. Moisture loving calcicoles such as hoary plantain (Plantago media) and mosses such as Ctenidium molluscum tend to favour steepish north-to-east slopes.

Rabbits

Rabbits were the main grazers on many English chalk grasslands until the early 1950s, but are not native to Britain or Ireland. They were introduced to both islands from southern Europe by the Normans, and by the fifteenth century had become very abundant. They were valued as a source of both food and fur, but by the first half of the twentieth century they had become a serious pest of agriculture and forestry in England. Various attempts were made to control or eradicate them, but these foundered because (amongst other reasons) many country people valued wild rabbits as a source of food or sport. The situation changed completely with the appearance of myxomatosis in 1953. This, a comparatively mild virus disease of American wild rabbits, had been found to cause over 99% mortality in laboratory populations of European rabbits, and had been used successfully in 1950 to combat rabbit infestations in Australia. In 1952 infected rabbits were released near Paris, from where the disease quickly spread, and in 1953 it appeared in Kent. By the end of that year myxomatosis was present in almost every part of Britain, and in 1955 it was estimated that the rabbit population had been reduced to 10% of its former level. Myxomatosis has remained common, though irregular in its occurrence, and although the numbers of rabbits are now higher than in 1955 they have not regained anything like their former abundance and show no sign of doing so.

FIG 137. The distribution of some chalk grassland species with slope and aspect in the Blandford– Shaftesbury area of north Dorset. The eight arms represent the points of the compass; slope (º) increasing outwards from the centre. Contours show the areas of the diagram within which the species attain the percentage cover shown. From Perring (1959).

CHALK AND LIMESTONE OF LOWLAND ENGLAND

Sheep’s fescue and upright brome

The commonest kind of chalk and limestone grassland in lowland England is dominated by sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina), which forms a short, somewhat open turf CG2. The fescue is almost always accompanied by crested hair-grass (Koeleria macrantha), meadow oat-grass (Helictotrichon pratense) and quaking-grass (Briza media). We students were taught by the late Humphrey Gilbert-Carter that the first thing you noticed when you sat down on chalk grassland in Cambridgeshire was ‘a pricking sensation, and a smell of cucumber’; the pricking sensation was dwarf thistle, the smell of cucumber was salad burnet. We might also have noticed the smell of another ubiquitous chalk-grassland plant, wild thyme (Fig. 136c). Other constant or near-constant plants in chalk grassland are glaucous sedge, ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata), bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), rough hawkbit (Leontodon hispidus), fairy flax, mouse-ear hawkweed (Fig. 138c) and small scabious (Scabiosa columbaria). Other frequent species include squinancywort, horseshoe vetch, spring-sedge (Carex caryophyllea), self-heal (Prunella vulgaris), hoary plantain, harebell (Campanula rotundifolia), common rock-rose and various calcicole mosses, such as Ctenidium molluscum (Fig. 73b) and Homalothecium lutescens, and the more widespread Pseudoscleropodium purum. Dwarf sedge (Carex humilis) can be abundant on some south-facing slopes in north Dorset and south Wiltshire. The short species-rich turf provides the habitat for our downland orchids, of which the commonest are pyramidal orchid (Anacamptis pyramidalis) and bee orchid (Ophrys apifera). This kind of vegetation is common with minor variations in chalk grassland on the North and South Downs, the Chilterns, the Hampshire, Berkshire, Wiltshire and Dorset chalk (Fig. 135), and northwards through Lincolnshire to the Yorkshire Wolds. It occurs on Carboniferous limestone on Mendip, in Gower, along the north Wales coast and in the Derbyshire Dales, amongst other places.

FIG 138. More calcareous grassland plants: (a) pasqueflower (Pulsatilla vulgaris), near Royston, Hertfordshire, April 1981; (b) carline thistle (Carlina vulgaris), Tenby, Pembrokeshire, August 1955; (c) mouse-ear hawkweed (Pilosella officinarum), Braunton, Devon, June 1990; (d) chalk milkwort (Polygala calcarea), Hambledon Hill, Dorset, June 1963; (e) clustered bellflower (Campanula glomerata), Hod Hill, Dorset, August 1973; (f) yellow-wort (Blackstonia perfoliata), Box Hill, Surrey, July 1989.

Upright brome (Bromopsis erecta) is another common dominant of grasslands on chalk and other limestones of lowland England, including the Cotswolds and the extension of Jurassic limestones northeastwards, and the magnesian limestone of west Yorkshire and County Durham. Upright brome most often dominates sites with little or no grazingCG3. Sheep’s fescue is usually still present, and most of its characteristic calcicole associated species are still to be found, but with lower constancy and cover, especially of the smaller species. Taller-growing species (such as salad burnet), or those with large robust basal rosettes (such as dwarf thistle) continue to do well, and coarser perennials such as the knapweeds (Fig. 139a), field scabious (Knautia arvensis) and wild parsnip (Fig. 139b) are sometimes conspicuous. The shorter downland orchids, such as musk orchid (Herminium monorchis) and autumn lady’s-tresses (Spiranthes spiralis) would be swamped by the taller herbage of the Bromopsis grasslands, but taller species such as the pyramidal orchid and the much rarer man orchid (Aceras anthopophorum) do as well here as in shorter turf, as does the now rare pasqueflower (Fig. 138a).

FIG 139. Common tall perennials of chalk country: (a) greater knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa), Hod Hill, Dorset, August 1973; (b) wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa), Box Hill, Surrey, July 1995.

Other dominant grasses: tor grass and Sesleria

Tor grass (Brachypodium pinnatum) is a vigorous grass with much the same distribution as upright brome, which invades poorly grazed or ungrazed grasslands. With its coarse, yellow-green unpalatable foliage it is a much more uncompromising dominant than upright brome. It occurs locally on the North and South Downs, but is commoner towards the western and northern parts of the chalk outcrop (where it is particularly characteristic of the Yorkshire Wolds), and on the Jurassic limestones of the Cotswolds and their extension northwardsCG4. These grasslands are typically much less species-rich than those dominated by either sheep’s fescue or upright brome, but sheep’s fescue remains as a near-constant ingredient though with low cover, and the only other near-constant species is glaucous sedge. Frequent or occasional species include bird’s-foot trefoil, harebell, salad burnet, fairy flax, quaking-grass, common rock-rose, wild thyme and yellow oat-grass (Trisetum flavescens). A long list of other calcicole species (including some rarities) can occur locally or occasionally, but none with any regularity. A much richer community dominated by various mixtures of upright brome and tor grass is particularly characteristic of the Jurassic limestone of the Cotswolds and sites such as the ‘hills and holes’ of the old quarries at Barnack in NorthamptonshireCG5. This community is home to a notable list of uncommon species, including pasqueflower and purple milk-vetch (Astragalus danicus), as well as some, such as man orchid, chalk milkwort (Fig. 138d) and bastard toadflax (Thesium humifusum), with their main distribution on the southern chalk.

We cannot leave English lowland chalk and limestone grasslands without mention of some sites that appear too dry, exposed and deficient in plant nutrients to have developed a complete vegetation cover. In the pioneer vegetation on the floor of a derelict chalk quarry in Hampshire Tansley and Adamson in 1926 found that the most abundant species was sheep’s fescue, followed by mouse-ear hawkweed, wild thyme, squinancywort, bird’s-foot trefoil, hop trefoil (Medicago lupulina), rough hawkbit and a number of less constant species. Grasslands described by Alex Watt from sharply drained chalky sands on the Suffolk Breckland produced a similar list, with the addition of crested hair-grass, meadow oat-grass, ribwort plantain, lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum), purple milk-vetch, a number of winter and spring annuals such as thyme-leaved sandwort (Arenaria serpyllifolia), whitlowgrass (Erophila verna) and early forget-me-not (Myosotis ramosissima) and a long list of bryophytes and lichens. Other dry nutrient-depleted sites, often with a history of disturbance, produce similar species lists – moss-rich, but often with some ‘weedy’ species such as blue fleabane (Erigeron acer) or wild strawberry (Fragaria vesca) – in which winter annuals and mosses figure prominently. These sites have enough in common to be considered togetherCG7. They support a number of southern and continental species, uncommon with us (e.g. Galium parisiense, Medicago minima, Silene conica), which find a congenial niche in this kind of vegetation in Breckland and elsewhere in dry parts of south and east England.

FIG 140. Berry Head, Devon, May 1983. Rocky dry grassland with white rock-rose (Helianthemum apenninum), horseshoe vetch (Hippocrepis comosa) and thrift (Armeria maritima).

FIG 141. Southern plants of dry rocky grassland: (a) honewort (Trinia glauca), male plant in flower, Berry Head, Devon, May 1970; (b) small restharrow (Ononis reclinata), Berry Head, June 1968.

A better-characterised and more species-rich open community occurs on sunny, dry, usually west- to southwest-facing limestone outcrops close to the south and west coasts of England and Wales. In these places sheep’s fescue is usually the dominant grass, but it makes only a very open cover, often equalled or exceeded by salad burnet, wild thyme, mouse-ear hawkweed and bird’s-foot trefoil, and usually leaving some bare soil (or limestone) visible amongst the foliage. Carline thistle (Fig. 138b) is a conspicuous and rather constant associate, as is cock’s-foot. Ribwort plantain and many of the other common limestone-grassland plants occur more of less frequentlyCG1. This is the habitat of white rock-rose on the headlands around Torbay (Fig. 140) and on Brean Down (Fig. 9) and Purn Hill in Somerset, and of hoary rock-rose (Helianthemum oelandicum) in Gower and along the North Wales coast. This community musters a long list of uncommon plants, including small restharrow (Fig. 141b) in Devon and South Wales, honewort (Fig. 141a) in Somerset and Devon, goldilocks aster (Aster linosyris) in Devon, Somerset, South Wales and North Wales, and Somerset hair-grass (Koeleria vallesiana) on Brean Down and the western end of Mendip, to name only a few of the rarest. The rarer rock-roses seem largely to exclude the common rock-rose from their preferred niche, even though the common species often occupies more run-of-the-mill limestone grasslands nearby.

UPLAND AND WESTERN LIMESTONE GRASSLANDS

With us Sesleria caerulea is a northern, western and largely upland plant of Carboniferous limestone country. It has two main areas of distribution. In Britain, its headquarters is the block of limestone country from the Yorkshire and Cumbrian Pennines between Skipton and upper Teesdale, to the lower ground around the head of Morecambe Bay, with a small Scottish outlier on a few mica– schist mountains in the central Highlands. In Ireland its main area in north Clare and southeast Galway includes the Burren; a somewhat smaller area in Sligo and Leitrim includes Ben Bulben and Carrowkeel. This grass is something of an enigma, because it dominates chalk grassland in the north of France along the cliffs of the Seine valley, as at Les Andelys, but occurs nowhere on the English chalk. The nearest it comes to the English chalk is in a few lowland Sesleria-dominated sitesCG8 on the magnesian limestone of eastern County Durham, with vegetation otherwise similar to southern-English chalk grassland.

The north of England

Sesleria is ubiquitous in limestone grasslands on steep hill-slopes, screes and rock ledges on the limestones of the Yorkshire Dales (Fig. 142). The typical Sesleria grassland of the mid and northern PenninesCG9 is a well-characterised community with clear affinities with the lowland limestone grasslands, but a decided flavour of its own. Apart from the dominant Sesleria, constant or near-constant species include wild thyme, crested hair-grass, limestone bedstraw (Galium sterneri – a northern and upland species with us), harebell, fairy flax, sheep’s fescue, quaking-grass, glaucous sedge, spring-sedge and the mosses Hypnum cupressiforme and Dicranum scoparium. Frequent species include common dog-violet (Viola riviniana), meadow oat-grass, bird’s-foot trefoil, eyebrights (Euphrasia spp.), mouse-ear hawkweed and the striking calcicole mosses Ctenidium molluscum and Tortella tortuosa. A number of species familiar in lowland calcareous grasslands are sparser here (e.g. salad burnet, ribwort plantain, rough hawkbit) or missing altogether (e.g. small scabious, dwarf thistle). Where seepage of water from the underlying limestone creates somewhat damper conditions, flea sedge (Carex pulicaris) and carnation sedge (C. panicea) join glaucous sedge as near-constants, bryophytes and lichens become much more prominent, and a sprinkling of species appear that are more at home in the small-sedge rich-fens of Chapter 14, such as grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia palustris), common butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris) and bird’s-eye primrose (Primula farinosa).

FIG 142. The valley of Cowside Beck near its confluence with Littondale, above Arncliffe, Yorkshire, April 2003. Sesleria grassland on slopes over Carboniferous limestone. Mountain avens (Dryas octopetala, Fig. 146) occurs on northwest-facing crags here, its southernmost English locality.

On the ‘sugar limestone’ of upper Teesdale the Sesleria–Galium sterneri grassland plays host to some of the suite of rarities that grow together here. The rare mountain sedge Kobresia simpliciuscula, hair sedge (Carex capillaris) and spring gentian (Gentiana verna) become near-constant in the short Sesleria–sheep’s fescue–sedge turf on Cronkley and Widdybank fells high in the dale; Teesdale violet (Fig. 143b) is very local (much less common than common dog-violet, which accompanies it) and frequent alpine bistort (Persicaria vivipara), mountain everlasting (Antennaria dioica) and the lichen Cetraria islandica remind us that we are in the uplands. A little to the south and nearer the Pennine escarpment, on the high limestone fells a bryophyte-rich version of this grassland, with frequent mossy saxifrage (Saxifraga hypnoides) and alpine scurvygrass (Cochlearia alpina), is the southernmost British locality of alpine forget-me-not (Myosotis alpestris).

Descending from the high Pennine fells to the lower limestone hills north and east of Morecambe Bay (Fig. 144) we encounter another version of the Sesleria–Galium sterneri grassland. This is drier, warmer and sunnier country, reflected in the occurrence of southern species such as squinancywort and small scabious. Horseshoe vetch is common (near its northern limit with us), and this is one of our strongholds of hoary rock-rose, which grows in the most open, stony Sesleria grassland (recalling the open Festuca grassland of its Welsh localities), while common rock-rose favours the more continuous turf farther back from the cliff edge. There are still reminders that we are in the north of England in the abundance of bryophytes, in species such as bird’s-foot sedge (Carex ornithopoda) in open Sesleria grassland on stabilised scree, and bird’s-eye primrose in seepages below the cliffs of Whitbarrow.

FIG 143. Notable plants in Sesleria grassland in northern England: (a) the lady’s-mantle Alchemilla glaucescens, a very local species of thin turf over limestone, Pen-y-Ghent, May 1982; (b) Teesdale violet (Viola rupestris); (c) rare spring-sedge (Carex ericetorum); (d) hoary rock-rose (Helianthemum oelandicum); the latter three on ‘sugar limestone’ in Teesdale, June 1975.

The Burren and other Irish limestone grasslands

Irish limestone grasslands have much in common with those of northern England, but some familiar species are missing. Common rock-rose is confined in Ireland to a single locality in Co. Donegal, and meadow oat-grass does not occur at all, despite much apparently suitable ground for both. The most-studied and certainly the richest limestone grasslands in Ireland are those of the Burren, in northern Clare just south of Galway Bay. The Burren hills, formed of almost flat-bedded Carboniferous limestone, rise steeply from sea level to a little over 300 m (Fig. 145). Compared to the limestone of the midland plain or the drumlin-covered country to the south, glacial drift is scanty on the Burren. Sesleria is present almost everywhere in the grassland, and commonly dominant. Those who know the Burren will find much that is familiar in the limestone of the Yorkshire Pennines and Cumbria, and vice versa. The big difference is the much more oceanic situation of the Burren, bringing milder winters and cooler summers than in northern England, and a more humid and windier climate.

FIG 144. Underbarrow Scar, Kendal, Cumbria. Sesleria grassland, habitat of hoary rock-rose (Helianthemum oelandicum) and rare spring-sedge (Carex ericetorum). The apomictic whitebeam Sorbus lancastriensis grows on the cliffs, and bird’s-foot sedge (Carex ornithopoda) on the grassy scree slopes below. The limestone hill of Arnside Knott in the distance.

FIG 145. The north coast of the Burren looking towards Black Head from Cappanawalla, July 1963. The vegetation is a diverse patchwork of limestone pavement, calcareous grassland with Dryas and heath subshrubs and limestone heath.

The patchy vegetation on the slopes of the hills of the western Burren is largely made up of a rich and very characteristic ‘grassland’ (named ‘Asperuleto-Dryadetum’ by Braun-Blanquet and Tüxen on their visit to the Ireland in 1949) dominated by varying proportions of Sesleria and mountain avens (Fig. 146), with near-constant squinancywort, glaucous sedge, flea sedge, harebell, sheep’s fescue, slender St John’s-wort (Hypericum pulchrum), fairy flax, bird’s-foot trefoil, tormentil (Potentilla erecta), goldenrod (Solidago virgaurea), devil’s-bit scabious (Succisa pratensis), wild thyme and common dog-violet, with a suite of conspicuous bryophytes including the mosses Breutelia chrysocoma, Ctenidium molluscum, Hypnum tectorum, Neckera crispa, Pseudoscleropodium purum and Tortella tortuosa, and the leafy liverworts Frullania tamarisci and Scapania aspera. Less constant than these but conspicuous almost everywhere are burnet rose (Rosa pimpinellifolia) and bloody crane’s-bill (Geranium sanguineum). Other frequent species include mountain everlasting, heather, carline thistle, Irish eyebright (Euphrasia salisburgensis – an Irish speciality), limestone bedstraw, fragrant orchid (Gymnadenia conopsea), sea plantain (Plantago maritima) and two common species of limestone grasslands elsewhere, ribwort plantain and crested hair-grass. Hoary rock-rose is very local, but abundant where it occurs.

On the exposed crests and limestone-pavement summits of the hills this community tends to pass into a wind-clipped turf a few centimetres high with constant squinancywort, heather, harebell, carline thistle, glaucous sedge, flea sedge, mountain avens, crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), scattered plants of dark-red helleborine (Epipactis atrorubens), sheep’s fescue, Sesleria, devil’s-bit scabious and wild thyme, from which the taller and more drought-sensitive species are missing. Where a substantial depth of organic soil has accumulated over the limestone and leaching has acidified the surface layers, Dryas may hang on for some time, but the smaller and more demanding calcicoles drop out progressively with the increase of the heathers (Calluna vulgaris and Erica cinerea), and the calcicole mosses are replaced by common calcifuge species, notably Hylocomium splendens, Hypnum jutlandicum and Rhytidiadelphus spp. Locally, this limestone heath is colonised by bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), and Arctostaphylos-rich heaths are an important component of the vegetation on the high limestone pavements and gently sloping summit plateaux around Black Head and Gleninagh Mountain. In general, the limestone heaths remain surprisingly species-rich, with near-constant Antennaria, Calluna, harebell, Carex flacca, C. pulicaris, bell heather, sheep’s fescue, slender St John’s-wort, bird’s-foot trefoil, tormentil, Sesleria, devil’s-bit scabious and wild thyme.

FIG 146. Mountain avens (Dryas octopetala), Black Head, Co. Clare, July 1970. Strictly a mountain plant over most of Europe (where it is abundant in the limestone Alps), Dryas comes down to sea level in the Burren and northwest Scotland.

To the east of the high limestone hills of the western Burren, an almost level expanse of lake-studded almost bare limestone stretches from Corrofin to Galway Bay (Fig. 147). In this area the sparse soils generally contain a greater proportion of glacial drift, and the predominant grassland (the ‘Antennaria dioica–Hieracium pilosella nodum’) is rather different. Dryas is often absent, but constant or near-constant species include mountain everlasting, kidney vetch (Anthyllis vulneraria), squinancywort, harebell, spring-sedge, sheep’s fescue, crested hair-grass, oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), fairy flax, bird’s-foot trefoil, mouse-ear hawkweed, ribwort plantain, self-heal, Sesleria, devil’s-bit scabious and wild thyme. Bryophytes are less conspicuous, but Hypnum lacunosum is near-constant, and Ctenidium molluscum, Fissidens adianthoides, Frullania tamarisci, Scapania aspera, Pseudoscleropodium purum and Tortella tortuosa are frequent. Outside the Burren similar grasslands, with or without Sesleria, and generally (not always!) poorer in species, occur widely on eskers and other suitable soils on limestone or calcareous drift.

Perhaps the only other limestone grasslands in Ireland to approach those of the Burren in distinctiveness and species-richness are those of the Ben Bulben massif that straddles the Sligo–Leitrim border, and the limestone country to the east and north (Fig. 148). Braun-Blanquet and Tüxen (1952) recorded species lists from mossy Sesleria grassland here, which have many species in common with Sesleria grasslands both in the north of England and in the Burren. What sets these Ben Bulben grasslands apart is the occurrence of such mountain plants as moss campion (Silene acaulis), fringed sandwort (Arenaria ciliata), purple saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia), yellow saxifrage (S. aizoides) and alpine meadow-rue (Thalictrum alpinum) around the outcrops and cliffs, but they intergrade with grasslands that would be unremarkable on limestone elsewhere.

FIG 147. Mullagh More, Co. Clare. A spectacular synclinal hill in the heart of the Burren, July 1966. Hoary rock-rose grows in the fragmentary limestone turf on the upper slopes, and there is a rich and interesting flora in the lakes, fens and turloughs in the flatter surrounding limestone country.

FIG 148. The Ben Bulben massif, Co. Sligo, at the entrance to Glencar. June 2010.

Dryas-rich communities on limestone in northwest Scotland

Cambrian limestone outcrops intermittently from Skye to the north Sutherland coast, and many of these bear a Dryas–Carex flacca ‘heath’CG13, which lacks Sesleria but has many of its more frequent species in common with the Asperuleto-Dryadetum of the Burren, including Dryas, mountain everlasting, heather, glaucous sedge, flea sedge, sheep’s fescue, slender St John’s-wort, fairy flax, bird’s-foot trefoil, sea plantain, tormentil, wild thyme and common dog-violet, and the mosses Ctenidium molluscum and Tortella tortuosa. Most of the limestone exposures are small and surrounded by acid rocks, so chance may have played an important part in variation between stands. Nevertheless, the average species-list stands up well to comparison with species-rich limestone grasslands farther south. A less common variant on Raasay and the north Sutherland coast lacks tormentil, slender St John’s-wort, flea sedge, heather, devil’s-bit scabious and the two calcicole mosses, but has creeping willow (Salix repens), harebell, lady’s bedstraw and the mosses Pseudoscleropodium purum and Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus.

HEAVY-METAL CONTAMINATION: MINE-SPOIL SITES

The Carboniferous limestone of Britain and Ireland is locally mineralised with seams rich in zinc and lead, which supported an active mining industry in times past, especially in Mendip, Derbyshire and the north Pennines. Lead was usually the metal most sought by the miners, but zinc is generally responsible for most of the toxicity. The distribution of lead-mining in Britain is pretty well mapped by the distribution of alpine penny-cress; much commoner than that species, and almost always accompanying it, is spring sandwort (Fig. 149a). Mine-spoil vegetation on limestone is usually dominated by sheep’s fescue and spring sandwort forming a rather open community, usually with harebell, wild thyme and common bent (Agrostis capillaris)OV37. Bird’s-foot trefoil, common sorrel (Rumex acetosa) and more locally alpine penny-cress and mountain pansy (Viola lutea) are frequent, and sea campion (Fig. 149b) or bladder campion (Silene vulgaris) are locally conspicuous; characteristic mosses include Weissia controversa var. densifolia, Bryum pallens and Dicranella varia. This open turf intergrades on less-contaminated ground with more normal limestone grassland. Of course metalliferous mining (and smelting) was not confined to limestone, and there are many old mine sites heavily polluted with copper, arsenic and other elements in southwest England and west Wales. The spoil from these has often been slow to recolonise, bearing only a skeletal vegetation of common bent, heather and common sorrel over a brownish carpet of bryophytes such as Jungermannia gracillima, Cephaloziella spp., Pohlia spp. and Racomitrium canescens. Larger pleurocarpous mosses and lichens (e.g. Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus, Cetraria aculeata, Cetraria islandica, Cladonia spp., Peltigera spp.) often form a mat above the surface, largely escaping the influence of the toxic soil underneath.

FIG 149. Heavy-metal-tolerant plants: (a) spring sandwort (Minuartia verna) and alpine penny-cress (Thaspi caerulescens, bottom left) growing in a carpet of the moss Weissia controversa var. densifolia on old zinc-mine spoil, Pikedaw, Malham, Yorkshire, July 1980; (b) sea campion (Silene uniflora) growing on old lead-mine spoil, Charterhouse, Mendip, Somerset, June 1989.

WHAT IS THE HISTORY AND ORIGIN OF THE LIMESTONE GRASSLANDS AND THEIR FLORA?

Open limestone grasslands comparable with ours are widely scattered across Europe. Species rare with us, such as pasqueflower, hoary rock-rose, goldilocks aster and others, can be seen in recognisably ‘the same’ habitat in chalk or limestone grasslands in France, Germany, the Czech Republic or Hungary. But there is general agreement that before deforestation by our Neolithic and Bronze Age forebears the whole of northern Europe, including Britain and Ireland, was substantially forested. The lowland grasslands were (along with the arable fields and hay meadows) a part of the cultural landscape, kept in being by centuries of traditional farming. The chalk and limestone grasslands and their flora, which we have been accustomed to take for granted, had ‘never had it so good’ as under traditional agriculture – which demanded a great deal of low-paid human labour. With traditional patterns of farming no longer economic, we have to face up to finding alternative ways to maintain elements of the traditional landscape that we value.

Where did the flora of the chalk and limestone grasslands come from? Naturally non-forested habitats, notably mountains above the tree-line, can tell us something about the possibilities. We can also study the (tantalisingly incomplete) evidence provided by pollen analysis of peats and other deposits (Chapter 2). The Late-glacial flora contained not only the expected arctic and mountain plants, but calcicoles such as salad burnet, wild thyme, bird’s-foot trefoil, hoary plantain, rock-roses and other plants of open grassland. Thus, a calcicole flora that could have given rise to our limestone grasslands was already established in our part of Europe before the spread of the forests. The question then is, where did the light-loving limestone-grassland species escape being overwhelmed by forest, to provide the nuclei for the limestone grasslands that followed forest clearance by Neolithic farmers?

A number of habitats are conceivable candidates. Dry, exposed crests, ridges and summits are one possibility; riverbanks kept open by erosion are another. We know that many such sites can bear closed forest at the present day, but we reckon without wild populations of browsers and grazers – deer, wild boar, aurochs. We do not know in enough detail how much effect these may have had in maintaining openings in the forest. At least fragmentary open communities could have kept a foothold in the crevices and ledges of inland cliffs of the harder limestones, and more extensively on exposed coasts such as the chalk of the south coast of England from Devon to Kent, and the Carboniferous limestone of Gower, the Great Orme, Humphrey Head, Whitbarrow or the Burren. On the exposed Burren coast a rich calcicole flora existed under open pine until about 500 BC (Feeser & O’Connell 2009). Some of these areas have outstandingly rich floras at the present day. Clearly that reflects ecologically favourable conditions for a rich diversity of species at the present time – but it is a reasonable conjecture that biodiversity ‘hotspots’ at least partly reflect historical factors. It seems hard to conceive of the British and Irish distribution of Sesleria being other than a historical ‘accident’, and equally hard not to invoke history to explain some of the widely disjunct distributions of species such as hoary rock-rose, mountain avens and shrubby cinquefoil (Potentilla fruticosa), or the similarities between the Burren and the Swedish island of Öland, which now enjoy very different climates. By contrast, we may think of the vegetation of the English chalk and Jurassic limestone grasslands as less influenced by its Late-glacial origins, and more by recruitment from the Continent over the 4000 years since Neolithic forest clearance began. But these are speculative thoughts, which future molecular genetic evidence may confirm or disprove.