Chapter 7

L2 Learning Is Mediated by Motivation, Investment, and Agency

Overview

As we discussed in Chapter 6, significant to the development of L2 learners’ semiotic repertoires are their multiple, intersecting social identities. They draw on their understandings of their identities and those of others to negotiate their participation in their social activities. However, while their social identities influence their actions, they do not determine them. Also mediating their involvement at the meso level of social activity are their motivations for participating in their learning environments, their investments in their contexts of learning, both real and imagined, and their agentive capacities to act. In this chapter, we examine more closely how the constructs of motivation, investment and agency mediate L2 learning.

Motivation

One of the most researched constructs in SLA, motivation has been considered a key variable in explaining success in L2 learning. Early research operationalized motivation as a static individual trait, intrinsic to the learner. As understandings of language and learning have changed, so have understandings of motivation. Current understandings view it not as an individual attribute, but as an organic, dynamic construct that is continuously evolving from the interrelations between individuals and their social contexts (Ushioda & Dörnyei, 2009; Al-Hoorie, 2017).

Recall in Chapter 4 we discussed the motivational role that the interactional instinct plays in language learning. The interactional instinct is an innate drive that pushes individuals to seek out emotionally rewarding relationships with others (Lee et al., 2009; Schumann, 2010). As we noted, the older L2 learners are, the more complicated social relationships become and the less intense the reward may be that is derived from such relationships. Consequently, their motivation for seeking out opportunities to use the L2 in interactions with others may also be reduced.

However, as research has shown, there are other motivating factors in addition to forming relationships with speakers of the L2 such as enjoyment of the learning environment, and educational and economic aspirations. The study by Richards (2006) provides an example of how enjoyment of the learning environment can increase students’ motivation. In his study, he showed how when different identities other than teacher and student were made relevant in classroom interactions, the student were more motivated to participate in their classroom activities. Their motivation was displayed in their increased involvement in the interactions and, more specifically, in their apparent willingness to volunteer information, respond to each other’s turns with heightened excitement, and provide help where needed. Likewise, Dobs (2016) found that moments of shared laughter between a teacher and students increased students’ motivation to participate in the class discussions, as displayed in a sustained increase in self-selected turns by the students. As a final example, the study by Henry, Davydenko, and Dörnyei (2015) of unusually successful adult migrant learners of Swedish found that the learners’ positive evaluations of their imagined new identities and life experiences in their new home sustained powerful motivational behaviors for learning Swedish.

To capture the complex dimensions of motivation, Zoltan Dörnyei proposed the L2 motivational self system (Dörnyei, 2009; Ryan & Dörnyei, 2013). The system has three components, each which influences individuals’ levels of motivation. The first two, the ideal L2 self and the ought-to L2 self, are related to self-image. The ideal L2 self has to do with the person one wants to be as an L2 user. The ought-to L2 self has to do with qualities one believes one should have to meet expectations and avoid negative consequences. The two types of selves are presumed to be powerful motivators for learners to succeed in learning other languages because of the psychological desire to reduce the discrepancy between one’s actual and ideal selves. The third component of the L2 motivational self system is the L2 learning experience. This is concerned with the learning environment and includes factors related to the curriculum, the teacher, and instructional activities. A key component of the L2 motivational self system is vision, which is considered “one of the highest-order motivational forces” (Dörnyei & Kubanyiova, 2014, p. 9).

According to Dörnyei (2009), the import of the L2 motivational self system is that it suggests new avenues for motivating language learners. In particular, learners’ desire to bridge the gap between the actual self and future self has been shown to be an effective motivator if learners have visions of their future selves that are elaborate and vivid and are in harmony with the expectations of the learners’ social environments. A key strategy is helping learners to create their visions of their ideal selves. This entails “increasing the students’ mindfulness about the significance of ideal selves, guiding them through a number of possible selves that they have entertained in their minds in the past, and presenting powerful role models” (Dörnyei, 2009, p. 33).

Building on the framework for vision of possible selves and its link to learners’ motivation offered by the L2 motivational system, more recently Dörnyei and his colleagues developed the construct of directed motivational current (DMC) (Dörnyei, Muir, & Ibrahim, 2014; Dörnyei, Ibrahim, & Muir, 2015; Muir & Dörnyei, 2013). A DMC is “an intense motivational drive which is capable of both stimulating and supporting long-term behaviour, such as learning a foreign/second language (L2)” (Dörnyei, Muir, & Ibrahim, 2014, p. 9).

DMCs have several characteristics. First, they are goal and vision oriented. A vision involves tangible images related to achieving the goal. Second, DMCs have a recognizable structure in that there is a clear starting point and behavioral routines related to the accomplishment of the goal. Third, people with DMCs have complete ownership of the process and confidence in their abilities to achieve their goals. Fourth, people experience highly positive emotions toward the process as they progress toward their goals. DMCs are rewarding because they propel the individual in the direction of a personally satisfying, highly valued goal or vision through goal-oriented action. Dörnyei, Ibrahim and Muir (2015) provide examples of DMCs in educational settings in Quote 7.1. The concept of DMCs is useful for understanding how intensely felt motivation drives learning (Dörnyei, Muir, & Ibrahim, 2014; Dörnyei, Henry, & Muir, 2016).

Quote 7.1 Examples of DMCs in Educational Settings

In educational settings, a DMC may be found within a high-school student’s intense preparation for a math competition, in a group of students’ deciding to put on a drama performance at school and giving the rehearsals top priority in their lives, or in the initiation of a school campaign to support a charity or other public cause. These instances involve the establishing of a momentum towards a goal that becomes dominant in the participants’ life for a period of time, and which allows both self and observers to clearly sense the presence of a powerful drive pushing action forwards.

Dornyei, Ibrahim, and Muir (2015, p. 98)

Investment

The concept of investment was conceptualized by Bonny Norton in the 1990s as a complement to the traditional construct of motivation as a fixed personality trait. This understanding, she argued, did not capture the complex relationship between power, identity, and language learning that she had observed in her research with five immigrant women in Canada who were taking an ESL course together (Peirce, 1995; Norton, 2000; 2011, 2013; Norton & deCosta, 2018; Norton & Toohey, 2011). From her year-long case study, which drew on data from diaries, questionnaires, interviews, and home visits, she found that while all the women wanted to learn English, their desires to use English varied depending on the social context.

Norton concluded that learners are best understood as individuals who have complex social histories and multiple desires and whose learning trajectories are therefore complex, contradictory, and ever changing. She argued that conceptions of motivation that were dominant in SLA at the time, which conceived of learners as having unified, cohesive identities, did not, and in fact could not, capture these phenomena. Drawing on a poststructuralist view of identity (Weedon, 1987), she coined the term investment to capture “the socially and historically constructed relationship of the [L2 learners] to the target language and their sometimes ambivalent desire to learn and practice it” (Peirce, 1995, p. 17).

Furthermore, drawing on Bourdieu’s (1977; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977) notion of cultural capital, Norton argued that learners who invest in learning another language may do so with the understanding that they will acquire a wider range of symbolic and material resources, which in turn will increase the value of their cultural capital and social power. By symbolic resources, Norton means language, education, and friendships; material resources refer to money, capital goods, and real estate (Norton, 2000). As the value of learners’ cultural capital increases, so do their desires for the future and their investment in learning. Norton elaborates on the notion of investment in Quote 7.2.

An extension of Norton’s findings on investment has to do with the imagined communities that L2 learners aspire to join. As discussed in Chapter 6, imagined communities refer to “groups of people, not immediately tangible and accessible, with whom we connect through the power of the imagination” (Norton, 2013, p. 8). Norton based this on data from two of the five women participants of her original study, both of whom withdrew from their ESL class during the time of Norton’s original study. One woman stopped attending because she felt that she was being positioned as an immigrant, rather than as a professional, an identity she had before arriving in Canada and a community she imagined joining in Canada. The other student stopped because she felt that her home country and her identity as a member of that country were marginalized in the class.

Quote 7.2 The Concept of Investment

The concept of investment, which I introduced in Norton Peirce (1995), signals the socially and historically constructed relationship of learners to the target language, and their often ambivalent desire to learn and practice it. It is best understood with reference to the economic metaphors that Bourdieu uses in his work—in particular, the notion of cultural capital. Bourdieu and Passeron (1977) use the term ‘cultural capital’ to reference to the knowledge and modes of thought that characterize different classes and groups in relation to specific sets of social forms. They argue that some forms of cultural capital have a higher exchange value than others in relation to a set of social forms which value some forms of knowledge and thought over others. If learners invest in a second language, they do so with the understanding that they will acquire a wider range of symbolic and material resources, which in turn increase the value of their cultural capital. Learners expect or hope to have a good return on that investment—a return that will give them access to hitherto unattainable resources.

Norton (2000, p. 10)

In both cases, the learners’ imagined communities and identities within them conflicted with the identity positions they were ascribed in their ESL classroom, which resulted in their dropping out of the course. Norton concluded that the women’s investments in learning were mediated by their imagined communities, communities that the learners believed offered them possibilities for expanding their resources, including the possibility of taking on new identities. Based on her research, Norton maintains that learners’ imagined communities are as real to learners as their current communities and may even have a greater impact on their investment in L2 learning. However, she cautions, it may be that the people and communities in whom learners have the greatest investment “may be the very people who provide (or limit) access to the imagined community of a given learner” (Darvin & Norton, 2015; Norton & Toohey, 2011).

The constructs of investment and imagined communities have been fruitful to explorations of L2 learning in a range of settings (Darvin & Norton, 2015; Haneda, 2005; Kanno & Norton, 2003; Norton & Gao, 2008). For example, in her case study of two university-level learners of Japanese, Haneda (2005) found that the students were differentially invested in learning to write in Japanese. The differences, she argued, resulted from an interaction among several factors, including their learning trajectories with respect to Japanese, their attitudes toward learning Japanese, their career aspirations, and their imagined future communities.

In their study of university-level students in a Hong Kong university, Gao, Cheng, and Kelly (2008) found that through their participation in a social community named the “English Club”, the students became invested in an imagined community of English speakers. This imagined community consisted not of target language English speakers, but of English-speaking Chinese who, because of their English skills, were considered elite and thus different from monolingual Chinese speakers. They concluded that investing in learning English afforded the group of students “cultural capital”, that is, desired social identities for negotiating their social relationships with their peers.

As a final example, Anya (2017) studied the investments of African American language learners of Portuguese in a study abroad program that took place in the Afro-Brazilian city of Salvador. She drew on findings from her earlier study (2011), which showed that the students who were invested in learning Portuguese were drawn by the desire to connect with and learn more about Afro-descendant speakers of their target language. Findings from her study of the study abroad program showed just how the learners’ investments in particular aspects of the Brazilian culture and communities gave shape to the eventual outcomes of their personal transformations during their time abroad.

Additional work has been undertaken by Norton and her colleagues to better understand student investment in digital literacy and English language learning (Early & Norton, 2014; Norton & Early, 2011; Norton & Williams, 2012; Stranger-Johannessen & Norton, 2017). The findings reveal the power of digital technologies in affording students opportunities to connect with and invest in communities that lie beyond the local and may have been unimaginable before. Norton and Williams (2012), for example, investigated the investment of secondary school students residing in a rural village in Uganda in Egranary, an offline digital library containing millions of multimedia documents that does not require connection to the internet. They found that the student participants became highly invested in the technology because it expanded the range of identities that were possible for them, both at the time of the study and in their imagined futures. As they became more proficient in using the resource, students’ cultural capital and social power increased, which in turn expanded what was imaginable to them. Travel, advanced education, professional careers, and other opportunities became part of the students’ imagined futures and imagined identities.

Individual Agency

Agency is the “socioculturally mediated capacity to act” (Ahearn, 2001, p. 112). “Socioculturally mediated” reflects the view that people are not agents of free will, independent decision-makers, with unfettered power and authority to use their resources to carry out any kind of action they want in any local context of action (Bucholtz & Hall, 2005; Kayi-Aydar, 2015). Rather, individual agency is a social construction, “something that has to be routinely created and sustained in the reflexive activities of the individual” (Giddens, 1991, p. 52). Social actions, then, are both structured and structuring, bound by their resources’ histories of meaning and yet “creative, variable, responsive to situational exigencies and capable of producing novel consequences” (Ochs & Schiefflin, 2017, p. 8).

While all acts of meaning making involve some level of agency, the degree of individual agency we can exert in taking action is not equal across contexts. Rather, the resources we use, and agentive actions we take in shaping our identities and refashioning our relationships with others, are both afforded and constrained by specific historical, social, and contextual circumstances constituting local contexts of action. For example, in many formal learning settings, there is more authority ascribed to teachers’ identities than to students’ identities. Consequently, teachers have greater power and more agency to determine the types of activities and resources to which learners will be given access and the opportunities they will have to engage in the activities and use their resources. As learners’ access to opportunities varies so does their L2 development. Those who are afforded more opportunities are more likely to be more positioned as “good” learners. Others who are afforded fewer opportunities are more likely to be positioned as “poor” or “resistant” learners. In such situations, learners may have little agency to reshape or resist these practices (Hall, 1997; Norton & Toohey, 2011).

The study by Dagenais, Day, and Toohey (2006) is an insightful illustration of the academic consequences of the unequal distribution of agency between teachers and students in constructing students’ identities as students (see Chapter 6). Theirs was a longitudinal study of a learner’s development of the literacy practices comprising her French and English classes in the French immersion elementary program in which the student, Sarah, was enrolled. Their findings reveal that while Sarah was active and verbal in some classroom practices, in others she was quiet and reluctant to speak and that this reluctance was differently interpreted by her teachers. One teacher evaluated Sarah’s participation negatively, attributing an “at risk” identity to her. In contrast, two other teachers interpreted Sarah’s reluctance to perform in large group conversations not as indications of academic difficulties. Rather, they perceived that Sarah was developing at her own pace and who “with encouragement, was poised on the edge of participation” (ibid., p. 215). These different positionings of Sarah were consequential in that the different identities were linguistically reinforced by the teachers in large group activities and small group exchanges. In both cases, Sarah had no agency to affect how she was positioned by her teachers and the academic consequences they engendered.

Many studies of L2 learners’ agency have shown that learners are not always passive participants in the process of learning. Rather, they are active agents who, depending on the context, have the power to make choices, initiate certain actions, resist others, and in other ways take control over their learning in pursuit of their goals in learning an L2 (Miller, 2012, 2014; Norton, 2013; van Compernolle & McGregor, 2016). The study by Baynham (2006) of an intensive ESOL for refugees and asylum seekers in the UK illustrates this. He shows how the learners took agentive steps by disrupting their instructional interactions to raise issues they were dealing with outside of the classroom. He concludes that these “unexpected irruptions of student lived experience” (p. 37) served to create opportunities for students to talk about the ongoing challenges they were dealing with outside of the classroom and help them develop strategies to deal with them.

Such agentive acts do not always enhance learners’ positions, however, as shown in Talmy’s (2008) study of first-year high school ESL classes. Despite the fact that the student population in these classes included local students who were long-time residents of their community and experienced in US schooling contexts, the curriculum was structured for recently-arrived students. This mismatch between the local students’ self-identifications and the ESL student identity embodied in the curriculum led to the local students’ development of a range of actions that worked to subvert their official classroom activities and the identity ascribed to them by their school. These actions included refusing to complete their homework, arguing with the teacher for reduced homework loads and teasing students who did the work. Their actions over the year, however, did little to change the official school practices and to transform their identities. In fact, the students received poor grades and were labeled low-achieving, and the school continued to identify them as ESL students. Their active resistance served not to transform their identities but to reproduce them and the classroom practices they struggled against.

Summary

Motivation, investment, and agency play significant roles in mediating L2 learners’ learning experiences and the development of their semiotic repertoires. Research that draws on these constructs makes clear that these are not constant or fixed properties but rather vary within and across contexts and over time. Depending on contextual circumstances, L2 learners may be differently motivated to participate in their contexts of learning. They may also be differently invested in the practices of their classrooms and the communities to which they aspire to belong. Finally, the degree of agency afforded to learners to create or take advantage of their L2 learning opportunities in specific contexts of use also changes. As learners’ motivation, investment, and degree of agency vary, so do their trajectories of experiences in and outside of the classroom, and, ultimately, their academic outcomes and semiotic repertoires.

Implications for Understanding L2 Teaching

At the meso level of social activity, L2 learning is mediated by ever-changing degrees of motivation, investment, and agency. As these vary, so do learners’ trajectories of learning. From this understanding of L2 learning, we can derive four implications for understanding L2 teaching.

Motivation plays a significant role in L2 learning. Based on his extensive research on the topic, Zoltan Dörnyei (2014) offers three principles for understanding the role that L2 teaching plays in creating a motivating learning environment. Principle One states that there is more to motivational strategies than offering rewards and punishments. Finding ways to promote learners’ visions of themselves as L2 learners and users, in the long run, will be more effective than the “carrot and stick” approach. Principle Two states that once engendered, student motivation must be actively maintained and protected. Otherwise, both the teacher and learners may lose sight of their goal, leading to the gradual diminishment of motivation. Principle Three states that what counts is the quality, not the quantity, of the motivational strategies that are used. Choosing strategies that suit the teacher, the learners, and the learning environment may be sufficient to create and sustain a positive motivational climate.

As noted previously, a directed motivational current is an intensive determination that supports L2 learners’ long-term, goal-directed L2 learning. Based on emerging findings from their developing research program on the topic, Dörnyei and his colleagues (2016; Dörnyei, Muir, & Ibrahim, 2014; Dörnyei, Ibrahim, & Muir, 2015; Henry, Davydenko, & Dörnyei, 2015), believe that L2 teaching can play a role in intentionally generating DMCs in their classrooms by facilitating intensive group projects. Project templates should include 1. a clearly defined target that is relevant and real to the students, 2. a structure that lays out a clear pathway toward the target and has a clear set of subgoals marking students’ progress, and 3. supportive cooperation among the learners that elicits positive emotionality or passion toward the project.

Recognizing the significant role that investment plays in L2 learning, L2 teachers must be ever mindful of how their teaching practices are linked to students’ investments in their future communities and identities within them. To do this work involves regular explorations with students of their investments as L2 learners and users. What and where are their desired communities? Who are their desired future selves and how do they imagine participating in the social groups in which they have the greatest investment? Learning environments should be structured in ways that allow students to critically examine their experiences as L2 learners and users, in and outside of the classroom, and to identify opportunities and possible roadblocks to realizing their visions. More generally, L2 teaching practices should engender a learning environment that is supportive, safe, and meaningful to learners’ real and imagined lives.

Individual agency plays a significant role in L2 learning. Recognizing the key role that learner agency plays in the process of meaning making, a multiliteracies pedagogy is aimed at creating learners who are active designers of their own meanings, and “with a sensibility open to differences, change and innovation”, and, more generally, opening up “viable lifecourses for a world of change and diversity” (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 175). L2 teaching that draws on the multiliteracies framework regards all modes of representation as dynamic processes of transformation rather than processes of reproduction and learners not as reproducers of meaning but as agentive meaning makers, i.e., “fully makers and remakers of signs and transformers of meaning” (ibid.). The goal behind the purposeful choices that L2 teachers make in designing their learning contexts is to lead to the transformation of L2 learners as expert designers of their own worlds (see Chapter 8).

Pedagogical Activities

This series of pedagogical activities will assist you in relating to and making sense of the concepts that inform our understanding of L2 learning as mediated by motivation, investment, and agency.

Experiencing

A. Motivation and Investment

Consider how motivation and investment have played a role in your language learning experiences by discussing your responses to the following questions with a partner or in a small group.

What motivated you to pursue the study of another language?

What role has investment in imagined identities and communities played in your desire to learn another language?

How have you sustained motivation to continue?

How has your investment in your imagined identities and communities shaped your learning opportunities?

What conclusions can you draw from your learning experiences about the role that you, as an L2 teacher, play in promoting learners’ motivation and investment in L2 learning?

B. Agency

Create a visual depiction of your understanding of the construct of agency and its relationship to your learning experiences in a particular learning environment in which you are or have been a student. Then, consider the following questions:

What contextual conditions appear to afford you more agency as a student to design your own paths of learning?

Which appear to constrain your agency?

What conclusions can you draw from your own experiences about the role that you as a teacher can play in promoting L2 learners’ agency as “meaning- maker[s]-as-designer[s]” (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 177).

Conceptualizing

A. Concept Development

Select two of the concepts listed in Box 7.1. Craft a definition of each of the two concepts in your own words. Create one or two concrete examples of each concept that you have either experienced first-hand or can imagine. Pose one or two questions that you still have about the concepts and develop a way to gather more information.

Box 7.1 Concepts: L2 learning is mediated by motivation, investment, and agency

agency

directed motivational current

L2 motivational self system

motivation

investment

B. Concept Development

Choose one of the concepts from the previous activity on which to gather additional information. Using the internet, search for information about the concept. Create a list of five or so facts about it. These can include names of scholars who study the concept, studies that have been done on the concept along with their findings, visual images depicting the concept, and so on. Create a concept web that visually records the information you gathered from your explorations.

Analyzing

A. Directed Motivational Current

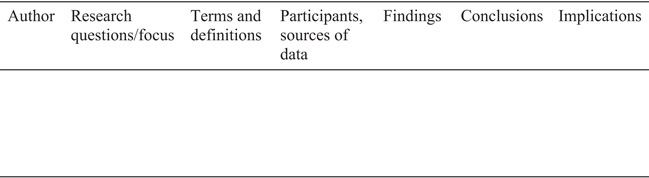

Locate two studies published in the last five years on the concept of directed motivational current. Summarize each study, using the table in Figure 7.1 to organize the information. Based on your readings of the studies, consider the following questions:

What kind of connections can you make between directed motivational currents and the concepts of investment and agency?

How useful is the construct for understanding L2 learning? What are its limitations?

What implications can you draw for L2 teaching?

B. Motivation, Investment, and Agency

Imagine you are the teacher of a high school or adult-level ESL classroom with 20 or so multilingual students who have varied educational backgrounds and come from various parts of the world. You have a few individuals who appear to be resistant to participating. They remain quiet in small group discussions, and they reluctantly respond when called upon. You know how important participation is to their academic success. How do you help them build the academic competence for participating in class that they need to succeed in your course? Design two or three strategies for working with the students that take into account at least one of the following constructs: motivation, investment, and agency.

Figure 7.1 Research study summary table.

Applying

A. Investment

In small groups, create a 5–7-minute audio file directed to L2 learners on the topic of investment and how investment in imagined identities and communities shapes learning. You can decide on the format of the audio file, e.g., interview, multi-host show, roundtable discussion, etc. You can also decide on whether you want to gear your show to a specific group of learners or if your show will speak to a wide audience of learners. For ideas on developing your file, search the internet, using podcast and audio files as search terms. Once completed, share your file with your classmates. As a class, create a plan for disseminating your files to potential users.

B. Investment

Design a 2–3-minute multimodal digital story about your imagined professional identity as a language teacher and your imagined school community. Digital stories are brief personal narratives told through words, videos, images, music, and sounds and using digital technology. Before beginning, gather “how-to” information and tap into available digital resources by searching the internet. In your story, draw on the concepts presented in this chapter and in previous chapters to describe and explain your goals and visions. Once completed, share with your classmates and together design a means to showcase and publish your stories for a wider audience.

References

Ahearn, L. (2001). Language and agency. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 109–137.

Anya, U. (2011). Connecting with communities of learners and speakers: Integrative ideals, experiences, and motivations of successful Black second language learners. Foreign Language Annals, 44(3), 441–466.

Anya, U. (2017). Racialized identities in second language learning: Speaking blackness in Brazil. Oxford: Taylor & Francis.

Baynham, M. (2006). Agency and contingency in the language learning of refugees and asylum seekers. Linguistics and Education, 17(1), 24–39.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information, 16(6), 645–668.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. (1977). Reproduction in education, society, and culture. London/Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 585–614.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4(3), 164–195.

Dagenais, D., Day, E., & Toohey, K. (2006). A multilingual child’s literacy practices and contrasting identities in the figured worlds of French immersion classrooms. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(2), 205–218.

Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2015). Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 36–56.

Dobs, A. (2016). A conversation analytic approach to motivation: Fostering motivation in the L2 classroom through play. Unpublished doctoral thesis/dissertation

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. (2014). Motivation in second language learning. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (4th ed., pp. 518–531). Boston, MA: National Geographic Learning/Cengage Learning.

Dörnyei, Z., Henry, A., & Muir, C. (2016). Motivational currents in language learning: Frameworks for focused interventions. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Dörnyei, Z., Ibrahim, Z., & Muir, C. (2015). Directed motivational currents: Regulating complex dynamic systems through motivational surges. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 95–105). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Kubanyiova, M. (2014). Motivating learners, motivating teachers: Building vision in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., Muir, C., & Ibrahim, Z. (2014). Directed motivational currents: Energising language learning by creating intense motivational pathways. In D. Lasagabaster, A. Doiz, & J. M. Sierra (Eds.), Motivation and foreign language learning: From theory to practice (pp. 9–29). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Early, M., & Norton, B. (2014). Revisiting English as medium of instruction in rural African classrooms. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(7), 674–691.

Gao, X., Cheng, H., & Kelly, P. (2008). Supplementing an uncertain investment?: Mainland Chinese students practising English together in Hong Kong. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 18(1), 9–29.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hall, J. K. (1997). Differential teacher attention to student utterances: The construction of different opportunities for learning in the IRF, Linguistics & Education, 9, 287–311.

Haneda, M. (2005). Investing in foreign-language writing: A study of two multicultural learners. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 4(4), 269–290.

Henry, A., Davydenko, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2015). The anatomy of directed motivational currents: Exploring intense and enduring periods of L2 motivation. The Modern Language Journal, 99, 329–345.

Kanno, Y., & Norton, B. (Eds.) (2003). Journal of Language, Identity, and Education. Special issue on imagined communities and educational possibilities. 2(4).

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). “He’s the star!”: Positioning as a tool of analysis to investigate agency and access to learning opportunities in a classroom environment. In P. Deters, X. Gao, E. Miller & G. Vitanova (Eds.), Theorizing and analyzing agency in second language learning: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 133–153). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Lee, N., Mikesell, L., Joaquin, A. D. L., Mates, A. W., & Schumann, J. H. (2009). The interactional instinct: The evolution and acquisition of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, E. R. (2012). Agency, language learning and multilingual spaces. Multilingua, 31(4), 441–468.

Miller, E. R. (2014). The language of adult immigrants: Agency in the making. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Muir, C., & Dörnyei, Z. (2013). Directed Motivational Currents: Using vision to create effective motivational pathways. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3, 357–375.

Peirce, B.N. (1995). Social identity, investment and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 9–31.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and second language acquisition. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Norton, B., & De Costa, P. I. (2018). Research tasks on identity in language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 51(1), 90–112.

Norton, B., & Early, M. (2011). Researcher identity, narrative inquiry, and language teaching research. TESOL Quarterly, 45, 415−439.

Norton, B., & Gao, Y. (2008). Identity, investment, and Chinese learners of English. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 18(1), 109–120.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44, 412–446.

Norton, B., & Williams, C. J. (2012). Digital identities, student investments and eGranary as a placed resource. Language and Education, 26(4), 315–329.

Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. (2017). Language socialization: An historical overview. In P. Duff & S. May (Eds.), Language socialization, 3rd edition (pp. 3–16). Cham: Springer.

Richards, K. (2006). “Being the teacher”: Identity and classroom conversation. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 51–77.

Ryan, S., & Dörnyei, Z. (2013). The long-term evolution of language motivation and the L2 self. Fremdsprachen in der Perspektive lebenslangen Lernens (pp. 89–100). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Schumann, J. H. (2010). Applied linguistics and the neurobiology of language. In R. Kaplan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 244–260). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stranger–Johannessen, E., & Norton, B. (2017). The African storybook and language teacher identity in digital times. The Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 45–60.

Talmy, S. (2008). The cultural productions of the ESL student at Tradewinds High: Contingency, multidirectionality, and identity in L2 socialization. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 619–644.

Usioda, E., & Dörnyei, Z. (2009). Motivation, language identities and the L2 self: A Theoretical overview. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 1–8). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Van Compernolle, R. A., & McGregor, J. (Eds.) (2016). Authenticity, language and interaction in second language contexts. New York: Multilingual Matters.

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. New York: Basil Blackwell.