Chapter 8

L2 Learning Is Mediated by Literacy and Instructional Practices

Overview

In Chapter 5, we discussed how individual repertoires are shaped by the various processes involved in primary language socialization. While L2 socialization shares the same principles as L1 socialization, the process is more complicated. This is due to the fact that adolescents and adults who are learning another language come to their L2 learning experiences already in possession of diverse repertoires of semiotic resources, cultural traditions, and community affiliations (Duff, 2007). It is also complicated by the fact that for many learners, their L2 learning experiences take place outside of the family, largely in educational institutions where instructional and literacy practices are prime sources of influence on L2 learning. In this chapter we examine the roles that these factors play in mediating both the processes and outcomes of L2 learning.

Literacy

Traditionally, SLA studies of L2 literacy were concerned primarily with the cognitive processes entailed in learning to read and write in another language (Grabe & Stoller, 2011; Young-Scholten, 2013). From the abundance of SLA research on the cognitive complexities of learning to become literate in another language, we know that developing literacy skills in another language depends on general and domain specific cognitive mechanisms such as selective attention, working memory, metalinguistic awareness, and comprehension monitoring. We also know that the development of literate skills and oral skills are interdependent and that the process of becoming biliterate is more cognitively complicated when learning to read and write in languages with different writing systems (Koda, 2005; Tarone, Bigelow, & Hansen, 2009; Tarone & Bigelow, 2005).

During the latter part of the twentieth century a more expanded understanding of literacy emerged in SLA, an understanding that was informed by research from such fields as anthropology, education, linguistics, and cultural psychology exploring relationships between cognition and oral and written social practices (e.g., Barton & Hamilton, 1998; Cook-Gumperz, 1986; Scollon & Scollon, 1981). Contemporary understandings view literacy not just as a cognitive phenomenon, something that happens inside one’s head, but as a social phenomenon as well, as ways of participating in social groups (Gee, 2010). Nor is literacy one set of technical skills for reading and writing; instead it is a set of social practices, of literacies, that are situated within and patterned by their social, institutional, and cultural contexts. Moreover, written texts do not stand alone. Gee (2010) notes that within different practices, written texts are “integrated with different ways of using oral language; different ways of acting and interacting; different ways of knowing, valuing, and believing; and often different ways of using various tools and technologies” (p. 166). Literacies and the ways of reading and writing they make possible are not universal but are multiple and varied, designed for different purposes by social groups and so are “different facets of doing life” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011, p. 13).

Individuals develop skills for participating in their literacy practices just as they learn language: by being socialized into the literacy practices of their social and cultural groups. In their participation, they develop a range of semiotic resources for producing and understanding the many ways of representing knowledge (Jewitt & Kress, 2003; Gee, 2010; Halliday, 1978). At the same time, they develop understandings of the affordances and constraints of the resources, and, more generally, of the values placed on the practices by their social groups. They learn how to act, know, believe, and value in “ways that ‘go with’ how they write and read” (Gee, 2010, p. 167).

This understanding of literacy has informed a substantial body of work comparing the home literacies of learners to the literacies of schools. One of the earliest and most influential studies is the study by Shirley Brice Heath (1983). Heath’s study was a longitudinal investigation comparing the language and literacy expectations, values, and practices of two rural, working-class communities with those found in their schools. She found that in the rural communities, children were socialized into ways of using language and texts that differed fairly significantly from those in schools. School practices more closely mirrored the language and literacy practices of the urban, middle-class communities in which the schools were located. These differences, she argued, resulted in different learning outcomes in school. Children from the rural communities had more difficulty succeeding academically than did their urban counterparts, whose home language and literacy practices more closely resembled those of school. This was so, Heath argued, because the contexts of schooling were a natural extension of the home contexts of the middle-class children. Consequently, the children were able to use what they had learned at home as a foundation for their learning in schools, whereas those from the rural communities could not.

This work has continued to inform research exploring learners’ home and school literacy practices (e.g., Phillips, 1983; McCarty & Watahomigie, 1998; Martin-Jones & Bhatt, 1998; Barton, Hamilton, & Ivanic, 2000; Maybin, 2008; Moll et al., 1992; Ortlieb & Cheek, 2017). Together, the findings are clear: learners whose home and school literacy practices differ do not perform as well as those learners whose practices are more similar. The reason for the differences in performances is not because some home practices are inherently inferior; rather, it is more a matter of compatibility. Learners whose home language and literacy activities reflect the dominant practices of schools are likely to have more opportunities for success since they only need to build on and extend what they have learned at home (Hall, 2008).

On the other hand, learners who are socialized into language and literacy practices that differ from schooling practices are likely to have more difficulty since they will need to add additional repertoires of practices to those they already know. In these cases, institutional perspective also plays a role. In institutions where learners’ home language and literacy practices are perceived as resources to be drawn on, difficulties are often diminished. In contrast, in institutions where learners’ practices are perceived as obstacles to be overcome, difficulties are often intensified (Barton & Hamilton, 1998).

Recognizing the value of learners’ home language and literacies for school-based learning, a growing body of research has explored ways of linking learners’ out-of-school multilingual language and literacy practices more closely to mainstream school practices (Gutiérrez, Baquedano-López, & Tejeda, 1999; Moll et al., 1992; Moje et al., 2004; Kenner & Ruby, 2012; Pahl, 2014). An early example of this is the work of Luis Moll and his colleagues (1992; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 2005). He argued that the home and community practices of students were rich resources of sophisticated language and literacy practices that should be drawn on rather than ignored in the academic practices of schools. He called for research into learners’ funds of knowledge and for the development of innovations that use the funds to transform school curricula.

Linking minority learners’ home and community experiences and their rich multilingual repertoires to those of schools has been proven to increase learners’ motivation and academic success. The study by Kenner and Ruby (2012) illustrates this. They brought together four teachers from complementary schools in the UK with two teachers from mainstream schools to plan lessons that became part of the curriculum in both schools. Complementary schools are supplementary or Saturday language schools in the UK. They offer language instruction to immigrant and ethnic minority learners to help them maintain their home languages. In the United States, they are usually referred to as heritage-language or community-based schools. Through the teachers’ collaborative efforts, they designed a multilingual syncretic curriculum, which included the following topics: poems and stories with parallel themes in different languages; learning about plants through gardening; fruits and vegetables found in different countries; and jobs in different countries. The study demonstrated the key role that the partnership between the mainstream and complementary teachers played in enhancing the children’s opportunities to draw on the full range of their capacities for learning, thereby challenging the “institutional constraints of a monolingualizing education system” (ibid., p. 414).

Digital Literacies

Fueled by the proliferation of digital technologies such as computers, video games, smart phones, and the internet, the shapes and purposes of literacy practices have expanded well beyond conventional print literacies. The ways in which individuals interpret and make meaning via these digital technologies are increasingly multimodal, with graphic, pictorial, audio, physical, and spatial patterns of meaning integrated within or even supplanting traditional written texts (Gee, 2010; Lankshear & Knobel, 2011).

Digital tools have not only transformed the means for producing, distributing, and interpreting meaning via orthographic scripts; they have changed the very nature of what counts as a text. These tools enable individuals to make and interpret meanings in ways that go beyond face-to-face settings and “‘travel’ across space and time” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011, p. 40). Devices such as mobile phones, smart pads and computers, multiplayer online games, and virtual social networking sites such as Facebook and Second Life have not only given individuals access to people and communities, and to information from around the world. They have also given rise to new types of literacies, including texting, tweeting, Facebooking, video gaming, producing websites and podcasting, to name just a few (Gee, 2012; Kern, 2015; Thorne, Fischer, & Lu, 2012). The term digital literacies captures these new literacies. It is defined as “the practices of communicating, relating, thinking and ‘being’ associated with digital media” (Jones & Hafner, 2012, p. 13).

Exploring L2 learners’ digital multilingual, multimodal literacies has become an increasingly important focus of L2 socialization research (Reinhardt & Thorne, 2017). Findings from these studies show how in various digital contexts such as online fanfiction communities, Facebook communities, and online game communities, individuals construct new multilingual and multimodal literacy practices that transcend boundaries and through these practices, create new identities and new relationships (e.g., Chik, 2014; Jonsson & Muhonen, 2014; Lam, 2009; Reinhardt & Thorne, 2017; Steinkuehler, 2008; Thorne, 2008). The term transnational literacies has been coined to refer to the practices that extend across national borders (Hornberger & Link, 2012; Warriner, 2007).

The abundance of digital innovations and the speed at which they continue to be developed have made even more complex the connections between home and school literacy practices. Also adding to the complexity are the changing demographics of communities. Contemporary communities are more linguistically and culturally diverse, comprising families of diverse unions, with members who are bilingual and multilingual and who have ties to multiple cultural groups. Findings from studies examining these communities reveal that their home practices are equally diverse, distinguished by the use of translingual practices, that is, two or more languages and a range of digital tools in addition to print in the creation, distribution, and use of complex transnational texts (Canagarajah, 2013; and see, for example, the studies by Barlett, 2007; McGinnis et al., 2007; Harris, 2003; Lam, 2004, 2009; Moore, 1999; Zentella, 1997).

L2 Socialization in Educational Settings

Scholars interested in L2 learning in schools have used the theoretical framework and methods of language socialization, detailed in Chapter 5, and the comparative studies of home and school practices as a springboard for research on the language and literacy practices found in L2 classrooms and their consequences for learner development (Duff, 1995, 1996, 2002; Harklau, 1994, 2002; Huang, 2004; Kanagy, 1999; Moore, 1999; Morita, 2000; Ohta, 1999; Poole, 1992; Smythe & Toohey, 2009). This research draws attention to the important role that the language and literacy practices of educational settings play in shaping not only L2 learners’ academic success but, as importantly, their understandings of the academic world and their places within it, their status relative to teachers and peers, and the relative legitimacy of their cultural and linguistic resources (Toohey, Day, & Manyak, 2007; Harklau, 2007).

An early study examining the relationship between classroom practices and L2 learning is Harklau’s (1994) comparative study of the language and literacy practices found in ESL and mainstream classrooms. She found significant differences in terms of the curricula content and goals and instructional practices. She argued that these differences had different socializing effects leading to the marginalization of the ESL learners. Willett (1995) and Toohey (1998) reported similar findings. They examined the socialization practices of mainstream elementary classrooms that included ESL learners and found that the teachers’ varying perceptions of the learners’ language and literacy abilities led to differentiation in the kinds of learning opportunities that the teachers made available to the students. This variation, in turn, led to differences in the children’s academic development.

Additional studies have shown that the processes and outcomes of socializing processes in educational settings are not stable, static, or unidirectional. Nor are learners passive recipients. Rather, L2 socialization is dynamic and multidirectional; where L2 learners’ motivations and resources diverge from those of the experts, the processes can be conflictual, and outcomes can vary, ranging from high levels of acculturation to variable levels marked by resistance or ambivalence (Duff, 2012; Miller & Zuengler, 2011). Studies by Hall (2004) and Canagarajah (2004), for example, reveal how students responded to what they perceived to be marginalizing forces of the official classroom practices by creating “safe houses” (Canagarajah, 2004, p. 12) in the classroom, speaking softly to neighbouring seatmates, catching up on work for other classes, and in other ways living quietly on the margins of the classroom (also refer to Talmy’s 2008 study, which was summarized in Chapter 7).

The increasing numbers of L2 learners attending secondary and post-secondary schools over the last two decades or so have presented new opportunities for research on L2 socialization in educational settings. Since the turn into the twenty-first century, research on the socialization processes and outcomes for these groups of students in various discipline-related academic events such as oral presentations, small group work, and thesis and dissertation writing activities has burgeoned (e.g., Duff & Kobayashi, 2010; Kobayashi, 2006, 2016; Seloni, 2011, 2014; Vickers, 2007; Yang, 2010; Zappa-Hollman, 2007; Zappa-Hollman & Duff, 2014).

Yang (2010), for example, examined the various practices by which L2 university-level undergraduate students were socialized into competent performance in their academic oral presentations. Seloni (2014) followed the academic socialization practices one mature multilingual writer engaged in as he completed his M.A. thesis. Zappa-Hollman and Duff (2014) examined the socialization of three L2 students into the academic culture of a Canadian university and found that students’ relationships with peers were key factors in their successful socialization. Together, the findings from this body of research reveal the linguistic, social, and cultural challenges these L2 learners face in their contexts of learning and the high stakes associated with their performances in their disciplinary academic discourses and their academic success. They also show the role that variation in learners’ access to opportunities within a classroom or across classrooms plays in mediating learners’ investment in these contexts (Darvin & Norton, 2015; Morita, 2004). The findings notwithstanding, recognizing the ever-changing demographics of communities world-wide, scholars in this field have called for continued research on academic language and literacy socialization and, in particular, in non-Western communities (Duff & Anderson, 2015; Moore, 2017).

In sum, studies of educational settings that draw on the language socialization paradigm add to understandings of how learners develop the semiotic resources and values of L2 language and literacy practices through their recurring engagement in social activities with other social group members, including peers and more experienced members. The processes are not uniform or stable, but are dynamic and multidirectional, and can lead learners to “new ways of acting, being, and thinking that do not simply reproduce the repertoire of cultural, linguistic, and ideological practices to which they are exposed” (Lee & Bucholtz, 2015, p. 323).

Mediational Role of Classroom Interaction

Interaction between teachers and students in L2 classrooms is one of the primary means by which socialization is accomplished. A great deal of research has focused specifically on the interactional routines of teacher-student interactions. Findings from a wide range of classrooms has revealed that a common instructional routine that mediates student learning opportunities is the specialized teacher-led three-action sequence labeled the IRF (e.g., Duff, 1995; Hall, 1995, 1998, 2004; Haneda, 2004; Lin, 1999a, 1999b; Mehan & Griffin, 1980; Mondada & Pekarek, 2004; Waring, 2008, 2009). The exchange involves the teacher eliciting information (I) from students in order to ascertain whether and how well they know the material. The teacher does this by asking a question or issuing a directive to which students are expected to provide a response (R). The third action provides some form of feedback (F) on student responses by, for example, using positive assessment terms such as good and right, prompting self-correction by the student and so on (Haneda, 2005; Lee, 2007; Nassaji & Wells, 2000; Wells, 1993). The third turns can also do additional work by, for example, asking students to clarify, elaborate, or defend their responses.

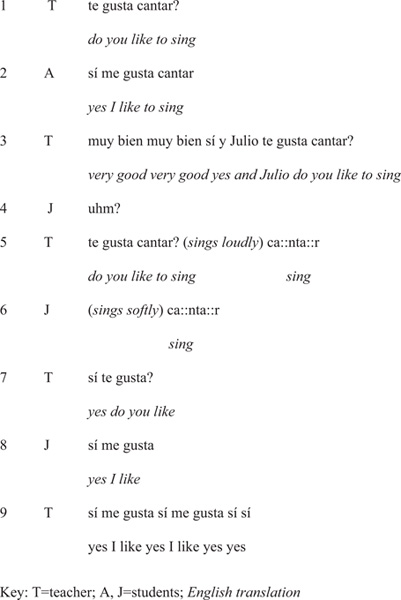

Research has shown that when the third turn is restricted to assessing the student’s response, learning opportunities are limited (Hall, 1995, 2004; Waring, 2008; 2009). For example, in her study of a high school foreign language classroom, Hall (1995) found that learning opportunities in the IRF were pervasively limited to short responses to simple teacher questions that did little more than ask students to list familiar objects or respond to simple yes-or-no questions. Student responses rarely extended beyond short phrases or clauses and, in giving their responses, students rarely had to attend to other students’ contributions. An example of this type of teacher-student interaction is illustrated in Figure 8.1. As shown here, the teacher asks students the same simple question, do you like to sing, which elicits a simple response by the students. In turn, the response elicits a positive evaluation by the teacher in the form of a repetition of the student’s response. Hall concluded that extensive use of this pattern of interaction afforded students very limited opportunities to develop anything other than very linguistically and cognitively simple resources for making meaning in Spanish.

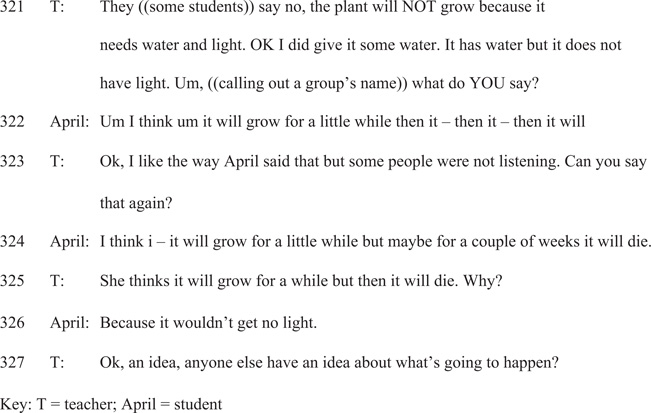

In contrast to the limited opportunities for student participation afforded by the type of interaction illustrated in Figure 8.1, findings show that where the third turn follows up on student responses by asking them to do additional work such as elaborate, clarify, and make connections, opportunities for learning are enhanced (e.g., Boyd & Maloof, 2000; Boxer & Cortes-Conde, 2000; Haneda, 2005; Lee, 2007). For example, in her study of the teacher-student interactions in an ESL science lesson in an elementary school, Haneda showed how teacher uptake of student responses in the third turn provided students with more opportunities to contribute to the lesson. Figure 8.2 is an excerpt from Haneda’s study that illustrates teacher uptake of student responses.

Figure 8.1 Restricted third turns.

Source: Hall (1995, p. 44).

Figure 8.2 Teacher uptake of student responses.

Source: Haneda (2005, pp. 324–325).

According to Haneda, the excerpt illustrates several actions performed by teacher turns following the teacher question in turn 321. First, she asks April to repeat her response, apparently so that others can hear her (turn 323). She then asks April to explain her reasoning for her prediction (turn 325), and after April’s response, she invites others to contribute other alternatives (turn 327). Then the teacher wraps up the sequence by summarizing the preceding discussion (turn 327). Haneda concluded that such actions afforded more opportunities to students to contribute and to provide answers that are more sophisticated, and thus facilitated students’ learning of both content and language.

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a term that has been used to refer to the mediating role of classroom interaction. It was originally coined by Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976) to refer to the process by which experts assist novices to achieve a goal or solve a problem that the novices could not achieve or solve alone. The process comprises six functions, which are used by experts in their interactions with novices to negotiate the parameters of a task, assess novices’ levels of competence relative to the task and determine the types of assistance they need to complete the task. The six functions are (Wood et al., p. 98):

Recruitment: Enlisting the novice’s interest in and attention to the task.

Reduction in degrees of freedom: Simplifying the task by reducing the number of acts needed to complete it.

Direction maintenance: Maintaining the novice’s motivation and progress toward the goals of the task.

Marking critical features: Calling the novice’s attention to relevant aspects of the task.

Frustration control: Decreasing the novice’s stress.

Demonstration: Demonstrating or modeling solutions to the task.

The goal of scaffolding is to eventually hand the responsibility for task completion to the learner. The term has been tied to the concept of zone of proximal development (ZPD), a key term of Vygotsky’s theory of development. Vygotsky argued that determining what a child can do on her own gives an incomplete picture of cognitive development as it only reveals what the child can do. Also essential is determining what the child can do with assistance from others as this provides insight into the child’s abilities that are in the process of forming (Minick, 1987; Lantolf & Poehner, 2004; Vygotsky, 1998). These tasks are accomplishing by finding children’s zones of proximal development. Vygotsky (1978, p. 86) defined the ZPD as

the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers.

McCormick and Donato (2000) drew on Wood et al.’s (1976) notion of scaffolding in their study of teacher questions in a university-level ESL classroom. They found that teacher questions served several purposes, such as marking critical features and reducing the degrees of freedom when there was a breakdown in communication between the teacher and students. Other questions were used to maintain students’ motivation and keep discussions going. Additional studies have found that scaffolding in the L2 classroom is not limited to teacher-student interactions but can also occur in peer interactions, with learners scaffolding each other’s learning to jointly solve problems and complete tasks (e.g., Antón & DiCamilla, 1998; Davin & Donato, 2013; De Guerrero & Villamil, 2000; DiCamilla & Antón, 1997).

Mediation

Some have critiqued the metaphor of scaffolding as being limited in its ability to capture the full picture of the ZPD in that it leads to a view of adult-child interactions as too one-sided with the adult constructing the scaffold alone and presenting it for the use of the novice (Stone, 1998). A related criticism is that it does not emphasize the ways in which the dynamics of scaffolding change as a function of the novice’s involvement (ibid). In fact, as pointed out by Stone (1998), Vygotsky never used the scaffolding metaphor.

James Lantolf, a renowned scholar of Vygotsky’s theory of development in the field of SLA, with his colleagues use the term mediation, a core concept of Vygotsky’s theory (1978, 1981), to refer to the contingent and graduated support that is provided by teachers and other experts (see Chapter 5). According to Vygotsky’s theory, all human psychological processes are mediated by tools such as language, and other semiotic resources. In the course of their activities together, children are socialized into adopting and using the tools, which then function as mediators of the children’s more advanced psychological processes (Karpov & Haywood, 1998; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006).

One of the earliest studies in SLA to examine the role of mediation in L2 development from a Vygotskian perspective is that by Aljaafreh and Lantolf (1994). They report on the L2 development of three university- level ESL students as they received corrective feedback in interactions with a tutor over six tutorial sessions. The goal of the sessions was to promote learner development through provision of such mediational means as hints, cues, prompts, corrections, and explanations on formulating specific L2 grammatical features in the students’ written essays. Such graduated mediation, according to Aljaafreh and Lantolf, allows the tutor and learner to discover and work within the learner’s ZPD.

Analysis of the interactions between the tutor and each of the students revealed 12 levels of help provided by the tutor that ranged from very implicit, e.g., prompting the learner to read the sentence containing an error, to very explicit, e.g., providing corrections and explanations. They concluded that while all types of feedback are potentially appropriate for learning, “types of error correction (i.e., implicit or explicit) that promote learning cannot be determined independently of individual learners interacting with other individuals” (ibid., p. 480).

These findings on the mediational role of corrective feedback were reinforced by Lantolf, Kurzt, and Kisselev (2016), who reanalyzed the original data from Aljaafreh’s (1992) dissertation on which Aljaafreh and Lantolf (1994) is based. They concluded that development in a second language is demonstrated in more than just linguistic performance. Also relevant are shifts in the quantity and quality of mediation provided by the expert interlocutor and the nature of learner contributions in response to the mediational process.

Instructional Approaches

There is a long history of research in SLA examining the efficacy of various instructional approaches. Findings show that while communicative approaches may provide motivation and offer plenty of opportunity for language use, they are inadequate in promoting L2 learning. This is because they do not intentionally call learners’ attention to L2 constructions that learners may not perceive on their own. Recall, in Chapter 2, it was noted that L2 constructions that are not salient in the L2 environment or essential for understanding will be learned very slowly, if at all (Schmidt, 1990; Ellis, 2002, 2008). What learners need are maximum opportunities not only to use the L2 but, as importantly, to focus their attention on constructions that would otherwise go unnoticed and unlearned.

For a number of years, L2 educators have advocated task-based approaches to L2 instruction as the ideal way to bring learners’ attention to particular constructions within meaningful, purposeful communication (Breen & Candlin, 1980; Doughty & Pica, 1986; Ellis, 2003, 2009; Gass, Mackey, & Ross-Feldman, 2005; Long & Crookes, 1993; Mackey & Gass, 2006; Prabhu, 1987; Skehan, 1996). In fact, there is abundant research showing instructional practices that combine explicit instruction that draw learners’ attention to L2 constructions that they may not notice or may be blocked by cues in their first language with meaning-making activities are powerful learning environments (Grabe & Zhang, 2016; Schleppegrell, 2013; and see Bowles & Adams, 2015; Kim, 2015, and Robinson, 2011 for reviews of literature on task-based learning).

One approach that has garnered a great deal of attention from both researchers and teachers for bringing together meaningful tasks and explicit instruction is the Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) approach. What distinguishes TBLT from other task-based approaches to L2 learning is that curricular goals, instructional activities, and assessments are organized around real-world target tasks designated by particular groups of L2 learners as those that they need to or want to be able to do in the L2. Michael Long (2014), one of the first scholars in SLA to bring attention to the importance of real world tasks in the design of instructional approaches, explains what tasks are in TBLT in Quote 8.1. These are different from task-supported approaches, in which activities labeled as tasks are typically unconnected to students’ real-world activities outside the classroom.

Quote 8.1 What Are Tasks in TBLT?

TBLT starts with a task-based needs analysis to identify the target tasks for a particular group of learners – what they need to be able to do in the new language. In other words, ‘task’ in TBLT has its normal, non-technical meaning. Tasks are the real-world activities people think of when planning, conducting, or recalling their day. That can mean things like brushing their teeth, preparing breakfast, reading a newspaper, taking a child to school, responding to e-mail messages, making a sales call, attending a lecture or a business meeting, having lunch with a colleague from work, helping a child with homework, coaching a soccer team, and watching a TV program. Some tasks are mundane, some complex. Some require language use, some do not; for others, it is optional.

Long (2014, p. 6, emphasis in the original)

Rod Ellis (2009, p. 242), a prominent scholar of language teaching research in the field of SLA, offers what he considers to be advantages that the TBLT approach has over other language teaching approaches:

It offers the opportunity for “natural” learning inside the classroom.

It emphasizes meaning over form but can also cater for learning form.

It affords learners a rich input of target language.

It is intrinsically motivating.

It is compatible with a learner-centered educational philosophy but also allows for teacher input and direction.

It caters to the development of communicative fluency while not neglecting accuracy.

It can be used alongside a more traditional approach.

There is clear evidence that how tasks are designed and how they are implemented in classrooms mediate how learners interact during the tasks and that these factors mediate the development of their L2 repertoires. What still needs to be determined is how well TBLT works in diverse instructional settings and with learners from diverse backgrounds and with diverse goals for L2 learning (Kim, 2015).

A broader instructional approach is the pedagogy of multiliteracies (New London Group, 1996; Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, 2015). First proposed in 1996 by a group of international scholars called the New London Group, this approach has been elaborated on by two of the co-authors of that paper, Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. The approach is based on the premise that the goal of teaching and learning is the transformation of learners into active designers of their own meanings. It is organized around the concept of designing, defined as the interested, motivated, and purposive act of meaning making. Design is forward-looking, “a means of projecting an individual’s interest into their world with the intent of effect in the future” (Kress, 2010, p. 23).

In a multiliteracies pedagogy, instruction integrates all semiotic modes of representation and is organized around four knowledge processes that move from the known to the unknown and facilitate concept building and critical analysis, reflection and application of knowledge and understandings (see Chapter 1 for an explanation of how we used the framework to organize the pedagogical activities of each chapter of this text). Unlike traditional pedagogical approaches, the multiliteracies approach considers critical analysis and reflection to be essential to learners’ development of critical stances toward their resources and their development as agents of social change and transformation.

The multiliteracies approach has been the topic of a small but growing body of research in SLA (e.g., Ajayi, 2008; Allen & Paesani, 2010; Hepple et al., 2014; Lotherington & Jenson, 2011; Zapata & Lacorte, 2017). For example, Lotherington (2012) documents the efforts of a group of elementary school teachers in Canada with whom she collaborated on an action research project to refashion their classroom literacy practices using the multiliteracies pedagogy. The study by Hepple et al. (2014) documents how teachers used the multiliteracies approach with a group of adolescent English language learners as a way to meet the students’ diverse language and literacy needs. Zapata and Lecorte’s (2017) book is a collection of empirical studies on the application of the multiliteracies approach to the teaching of Spanish to heritage speakers in the United States.