highlights

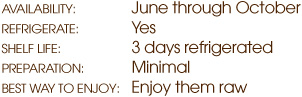

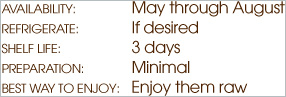

According to the ancient myths, Raspberries were originally white until the nymph Ida pricked her finger while collecting berries for baby Jupiter. The blood from her fingers caused the berries to turn their deep red color and from this came the botanical name for Raspberries, Rubus idaeus, with Rubus meaning “red” and idaeus meaning “belonging to Ida.” Although Raspberries have been around since prehistoric times, it has only been within the past several hundred years that they have been cultivated. Sweet and subtly tart, fresh Raspberries are a great addition to your breakfast cereal or favorite dessert. And because they have a short growing season, remember to enjoy these delicately structured berries while they are in season since they are not available year-round.

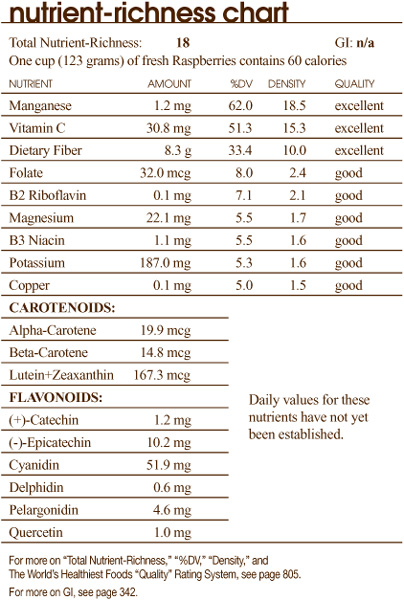

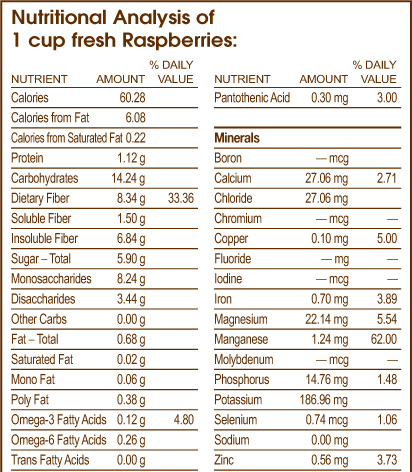

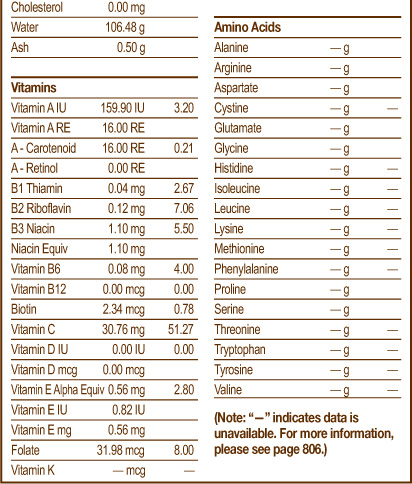

Raspberries are unusually rich in health-promoting nutrients that provide powerful antioxidant protection from free-radicals that can damage cellular structures, including DNA. These include ellagic acid and flavonoids such as quercetin, kaempferol and the anthocyanins, which give red raspberries their deep red color. Like many berries, Raspberries are also exceptionally rich in dietary fiber. Raspberries are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are nutritious and delicious, but also because they are low in calories: one cup of fresh Raspberries contains only 60 calories! (For more on the Health Benefits of Raspberries and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 350.)

Wild Raspberries are thought to have originated in eastern Asia, but there are also varieties that are native to the Western Hemisphere. Raspberries are known as “aggregate fruits” since they are a compendium of smaller seed-containing fruits, called drupelets, which are arranged around a hollow central cavity. Most Raspberries are red, but there are also yellow, amber, apricot, purple and black varieties. Although they may differ in color, they all are similar in texture and flavor.

Most cultivated varieties of Raspberries are grown in California from June through October and are only available during this time of the year.

Raspberries are a concentrated source of oxalates, which might be of concern to certain individuals. (For more on Oxalates, see page 725.

Enjoying the best tasting Raspberries with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 3 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

1. the best way to select raspberries

When you select Raspberries, look for ones that are fully ripe because they will not ripen after they are picked. Fully ripe Raspberries are slightly soft, plump and deep in color. Vitamins and health-promoting phytonutrients, many of which can act as powerful antioxidants, are at their peak when Raspberries are ripe; therefore, by selecting ripe Raspberries, you will also be enjoying Raspberries with the highest nutritional value as well as the best flavor. Since Raspberries are one of the foods on which pesticide residues are frequently found, I recommend selecting organically grown varieties whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid overripe Raspberries that are very soft, mushy or moldy. Make sure that they are not packed too tightly in the container and show no signs of stains or moisture. These are indications that they may be crushed, damaged or spoiled.

I have found it is best to purchase Raspberries no more than 1 or 2 days prior to use as they are highly perishable and do not store well.

If they are deep in color, plump and slightly soft, they are ready to eat. They must be ready to eat when you purchase them as they will not ripen.

2. the best way to store raspberries

Proper storage is an important step in keeping Raspberries fresh and preserving their nutrients, texture and unique flavor.

Raspberries continue to respire even after they have been harvested. The faster they respire, the more the Raspberries interact with air to produce carbon dioxide. The more carbon dioxide produced, the more quickly they will spoil. Raspberries kept at a room temperature of approximately 68°F (20°C) give off carbon dioxide at a rate of 125 mg per kilogram every hour. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different fruits, see page 341.) Refrigeration helps slow the respiration rate of ripe Raspberries, retain their vitamin content and increase their storage life.

Refrigerate Raspberries as soon as you bring them home. Since water encourages spoilage, do not wash Raspberries before refrigeration. While Raspberries that are stored properly will remain fresh for up to 3 days, if they are not stored properly they will only last about 1–2 days.

Like all berries, Raspberries are very perishable, so great care should be taken in their handling and storage. Before storing in the refrigerator, remove any Raspberries that are moldy or damaged so that they will not contaminate others. Return unwashed, whole berries to their original container or spread them out on a plate, cover with a paper towel, and then cover with plastic wrap.

health benefits of raspberries

Raspberries are rich in ellagic acid, a phytonutrient that is viewed as being responsible for a good portion of the antioxidant activity of Raspberries (and other berries). Ellagic acid helps prevent unwanted damage to cell membranes and other structures in the body by neutralizing overly reactive oxygen-containing molecules called free-radicals.

However, ellagic acid is not the only well-researched phytonutrient component of Raspberries. They also contain flavonoids such as quercetin, kaempferol and anthocyanins. Anthocyanins give red Raspberries their rich red color as well as unique antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, including the ability to prevent overgrowth of certain bacteria and fungi (for example, the yeast Candida albicans, which is a frequent culprit in vaginal infections and can be a contributing cause in irritable bowel syndrome).

The antioxidant potential of Raspberries’ ellagic acid, as well as their other phytonutrients, may help promote cardiovascular health since they reduce the oxidation of LDL (“bad” cholesterol) and help to safeguard the function of blood vessels. In addition to their phytonutrient concentrations, Raspberries’ ability to support the heart also comes from the other nutrients that they provide. They are an excellent source of vitamin C and manganese and a good source of copper, three very powerful antioxidant nutrients that also help to protect the body from oxygen-related damage. Raspberries are also an excellent source of health-promoting dietary fiber, which can help to reduce elevated cholesterol levels. Additionally, Raspberries are a good source of folic acid, which reduces heart disease risk by lowering homocysteine levels, as well as a good source of potassium and magnesium, which help to regulate blood pressure.

Research suggests that Raspberries may have cancer-preventive properties. Results from animal experiments suggest that Raspberries have the potential to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and tumor formation in various sites, including the colon and the mouth. In test tube experiments, Raspberries have been found to positively mediate cell signaling as well as inhibit an enzyme whose abnormal production has been linked to metastasis (invasion and spread of cancer cells). Deficiency of niacin, a B vitamin of which Raspberries are a good source, has been directly linked to genetic (DNA) damage.

Since Raspberries contain only 60 calories per one cup serving, they are an ideal food for healthy weight control.

STEP-BY-STEP No Bake Recipes

Properly preparing Raspberries helps ensure that they will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

As Raspberries are very delicate, wash them very gently, using the light pressure of the sink sprayer if possible, and then pat them dry. To prevent Raspberries from becoming waterlogged, wash them right before eating or using in a recipe. (For more on Washing Fruit, see page 341.)

I have discovered that Raspberries retain their maximum amount of nutrients and their best taste when they are fresh and not prepared in a cooked recipe. That is because their nutrients—including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes—are unable to withstand the temperature (350°F/175°C) used in baking. So that you can get the most enjoyment and benefit from fruit, I created quick and easy recipes, which require no cooking. I call them “No Bake Recipes.”

highlights

The popularity of Cantaloupe, with its refreshingly rich flavor and aroma, dates back to ancient Greece and Rome. It is believed that it was named for a former Papal garden near Rome called Cantalou where this variety of melon was developed. Cantaloupes were introduced to the U.S. during colonial times but not grown commercially until the late 19th century. Today, they are renowned for their wonderful flavor and minimal number of calories, making them a favorite snack, dessert or salad, especially among those watching their weight. As with most fruits, Cantaloupe requires little preparation and is ready to serve and eat in a matter of minutes.

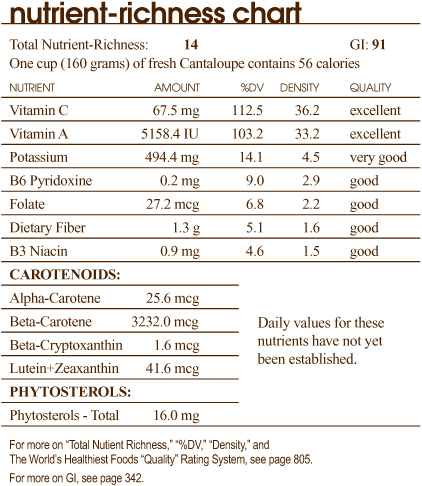

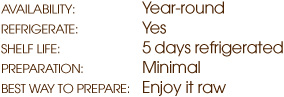

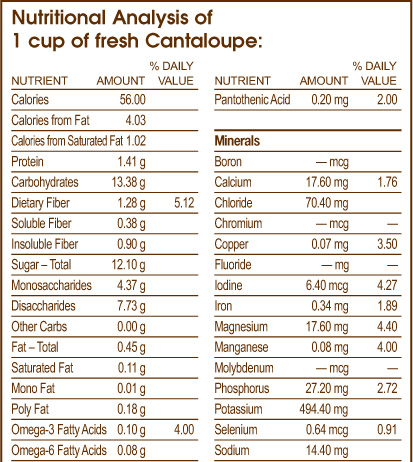

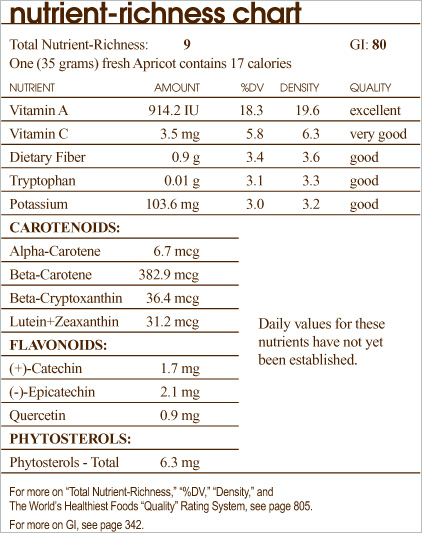

Cantaloupe is an excellent source of vitamins A and C, powerful antioxidants that protect against damage to cellular structures and DNA. The distinctive orange color of Cantaloupe is provided by its wealth of betacarotene, a carotenoid phytonutrient that is a precursor to vitamin A. Cantaloupe is an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because it is nutritious and tastes great but also because it is low in calories: one cup of Cantaloupe contains only 56 calories! (For more on the Health Benefits of Cantaloupe and a complete analysis of its content of over 60 nutrients, see page 354.)

The fruit that we call Cantaloupe is, in actuality, really a muskmelon. The true Cantaloupe is a different species of melon, which is mostly grown in France and rarely found in the United States. Cantaloupe is a melon that belongs to the same family as the cucumber, squash, pumpkin and gourd. Like many of its relatives, it grows on the ground on a trailing vine. The botanical name for Cantaloupe is Cucumis melo. Other popular melon varieties include the honeydew, casaba and crenshaw melon.

Cantaloupes range in color from orange-yellow to salmon and have a soft and juicy texture with a sweet, musky aroma that you can smell when they are ripe.

While Cantaloupe may be available throughout the year, the peak of the season runs from June through August. These are the months when its concentration of nutrients and flavor are highest, and its cost is at its lowest.

Cantaloupe is one of the foods most commonly associated with allergic reactions in individuals with latex allergies. (For more on Latex Food Allergies, see page 722.)

Enjoying the best tasting Cantaloupe with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 3 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

1. the best way to select cantaloupe

You can select the best tasting Cantaloupe by looking for one that is fully ripe with a sweet aroma. Ripe Cantaloupe will not only have the best flavor and texture but will also feature the highest level of vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes. Cantaloupe will not ripen after it has been picked. I have discovered some clues that will help you find a ripe Cantaloupe: (1) tap the melon with the palm of your hand and listen for a hollow sound, (2) look for one that seems heavy for its size, (3) look for rind underneath the netting that is yellow- or cream-colored, (4) look for a “full slip” (the area where the stem was attached) that is smooth and slightly indented, (5) look for one whose end opposite the full slip is slightly soft and (6) you should be able to smell the fruit’s sweetness subtly coming through.

Cantaloupe is so fragrant that you can check for its aroma even when it has been pre-cut and packaged in a plastic container. As with all fruits, I recommend selecting organically grown Cantaloupe whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid Cantaloupe that has no aroma or has green undertones since both indicate it is not ripe. Not only will it not have a good flavor, but it will provide less nutrients. Do not purchase Cantaloupe that is bruised or has spots that are overly soft, two signs of an overripe melon. Be careful not to select a Cantaloupe with an overly strong odor as this also indicates an overripe or fermented melon.

If the Cantaloupe is ripe with a rich, sweet melon aroma, and the end opposite the full slip is slightly soft, it is ready to eat. Cantaloupe tastes best at room temperature.

2. the best way to store cantaloupe

Proper storage is an important step in keeping Cantaloupe fresh and preserving its nutrients, texture and unique flavor.

Cantaloupe continues to respire even after it has been harvested. The faster it respires, the more the Cantaloupe interacts with air to produce carbon dioxide. The more carbon dioxide produced, the more quickly it will spoil. Refrigeration helps slow the respiration rate of a ripe Cantaloupe, retain its vitamin content and increase its storage life.

While refrigerating Cantaloupe will increase storage time and the coolness will make it more refreshing, it may also blunt its flavor. Cantaloupe that is stored properly will remain fresh for up to 5 days; if it is not stored properly, it will only last about 2 days.

Cantaloupe that has been cut should be refrigerated in a tightly sealed container to ensure that the ethylene gas that it emits does not affect the taste or texture of other fruits and vegetables.

3. the best way to prepare cantaloupe

Properly preparing Cantaloupe helps ensure it will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

It is important to scrub Cantaloupe under running water before cutting it. This helps to remove any bacteria on the surface and prevents it from being transferred to the flesh when you cut into the melon. (For more on Washing Fruit, see page 341.)

After washing, cut the Cantaloupe in half, remove the seeds and netting, and cut it into pieces of desired thickness. Alternatively, you can scoop out the flesh with a melon baller.

I have discovered that Cantaloupe retains its maximum amount of nutrients and its best taste when it is enjoyed raw and not prepared in a cooked recipe. That is because its nutrients—including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes—are unable to withstand the temperature (350°F/175°C) used in baking. So that you can get the most enjoyment and benefit from fruit, I created quick and easy recipes, which require no cooking. I call them “No Bake Recipes.”

Q I was told that it is better to not eat fruits, such as Cantaloupe, right before a meal. Is this true?

A Whether to wait a certain time before or after a meal to eat fruit is one of the most common questions I get asked regarding food combining. Although there appears to be no research evidence about when it is best to eat fruits in relation to the rest of your meal, many people report better overall digestion when they follow the practice of waiting about one half hour or so before or after a meal to enjoy their fruit. A number of healthcare practitioners also advocate fruit consumption separate from meals.

health benefits of cantaloupe

As a result of its concentration of betacarotene, Cantaloupe is an excellent source of vitamin A. Both vitamin A and betacarotene are important vision nutrients. One large-scale research study found that those who had the highest dietary intake of vitamin A had a 39% reduced risk of developing cataracts. A study investigating the relationship between the need for cataract surgery and diet revealed that those who ate diets that included Cantaloupe were half as likely to need cataract surgery. Additionally, another study showed that eating 3 servings of fruit per day may reduce the risk of macular degeneration by 36% compared to eating 1.5 servings per day.

In addition to its antioxidant activity, Cantaloupe’s vitamin C is critical for good immune function. Vitamin C stimulates white cells to fight infection, directly kills many bacteria and viruses, and regenerates vitamin E back into its active form.

Cantaloupe contains many nutrients that promote cardiovascular health. It is a very good source of potassium, which enhances healthy muscle contractions and is therefore important for maintaining healthy blood pressure levels and heart function. Its folate and vitamin B6 help keep levels of homocysteine in check; elevated levels of homocysteine can damage artery walls, contributing to the development of cardiovascular disease. Intake of vitamin C is also associated with a reduced risk of heart disease. Additionally, Cantaloupe is a good addition to a fiber-rich diet, which has been found to be beneficial for heart health.

Melons have been found to be one of the best sources of myoinositol, a building block of cell membranes. This nutrient has been the focus of recent studies on treating depression, panic disorder, diabetic nerve damage and liver disease as well as preventing some cancers. Although findings are preliminary, it is certainly an exciting new area of research. Cantaloupe is also a good source of niacin, a B vitamin whose deficiency has been directly linked to genetic (DNA) damage.

Since Cantaloupe contains only 56 calories per one cup serving, it is an ideal food for healthy weight control.

STEP-BY-STEP No Bake Recipes

highlights

Pineapples were named by European explorers who believed they looked like pinecones with the flesh of an apple. Fresh Pineapples were once reserved for the elite, who served them as a sign of prestige since they were very expensive, owing to the costs of transporting them stateside from the Caribbean Islands. Today, since they are more affordable and easily found at most local markets, Pineapples have become second only to bananas as America’s favorite tropical fruit. Exceptionally sweet and juicy with a wonderful flavor, Pineapples are a great way to add a little taste of the tropics to your meal. Friends have asked me why the same batch of Pineapples that taste great in Hawaii don’t taste as good when transported to the Mainland. A Pineapple farmer told me that the reason Pineapples taste best in Hawaii is because they are served or canned the same day they are picked. Pineapples develop an acidic taste after 24 hours.

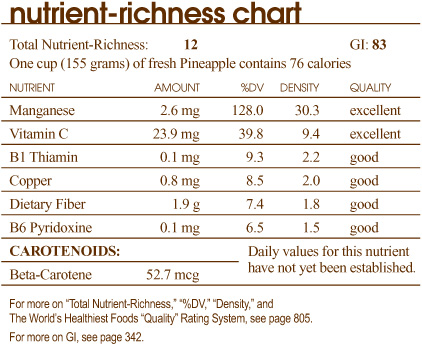

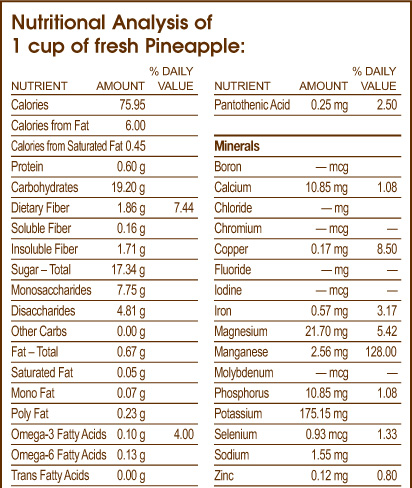

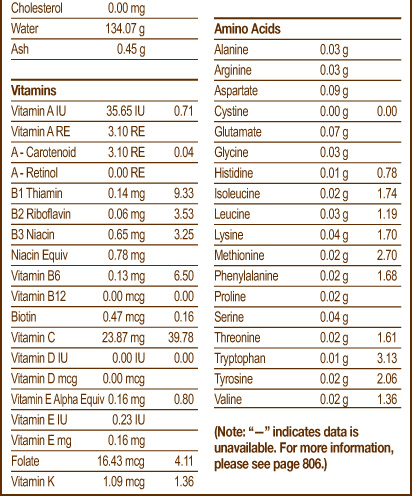

Pineapple contains a special group of enzymes called bromelain, which function both as a digestive aid and anti-inflammatory compound. Pineapple is also an excellent source of the trace mineral manganese—an essential cofactor in a number of enzymes important in energy production and antioxidant defenses—as well as vitamin C, a powerful antioxidant that protects against oxidative damage to cell structures. Pineapples are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are nutritious and taste great, but also because they are low in calories: one cup of Pineapple contains only 76 calories! (For more on the Health Benefits of Pineapple and a complete analysis of its content of over 60 nutrients, see page 360.)

While Pineapples are thought to have originated in South America, they were first discovered on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe by Christopher Columbus in 1493. Pineapple (Ananas comosus) belongs to the Bromeliaceae family, from which the name of one of its most important health-promoting compounds, the enzyme bromelain, was derived. Pineapples are a composite of many flowers whose individual fruitlets fuse together around a central core. Each fruitlet can be identified by an “eye,” the rough spiny marking on the Pineapple’s surface.

This is the most popular, and often considered the best tasting, of the varieties most commonly found in markets. It is a Pineapple grown in Hawaii with a cone-like shape and weighs from 3 to 5 pounds.

A hybrid variety that is exceptionally sweet and has a longer storage life than the Smooth Cayenne.

Small with firmer, less acidic flesh. Drier than the Smooth Cayenne and not quite as sweet.

Grown in the Caribbean, they are similar to the Smooth Cayenne but have a “squarish” shape and tough outer shell.

Grown in Mexico, these larger Pineapples weigh from 5 to 10 pounds.

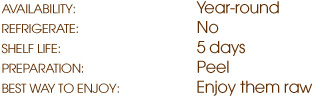

Although Pineapples are available year-round, the peak of the Pineapple season runs from March through June. These are the months when their concentration of nutrients and flavor are highest, and their cost is at its lowest.

Enjoying the best tasting Pineapples with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 3 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

1. the best way to select pineapple

When you select Pineapples, look for ones that are fully ripe. Pineapples will not ripen after they are picked. Fully ripened Pineapples will have a well developed flavor as well as the most developed concentration of nutrients, including vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. It is best to smell the aroma of a Pineapple before you purchase it. Fully ripe Pineapples have the sweet fragrant aroma of Pineapple and give slightly to pressure. While larger Pineapples will have a greater proportion of edible flesh, there is usually no difference in quality between those that are small or large. Leaves should look fresh and green. Vitamins and antioxidants are at their peak when Pineapples are ripe, so by selecting ripe Pineapples, you will also be enjoying Pineapples with the highest nutritional value. Pineapples will soften and become juicier after they are picked, but they will not get sweeter because their starches will not turn to sugar. As with all fruits, I recommend selecting organically grown varieties whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid Pineapples that are too soft or have a sour or fermented smell. If they are green, they will be fibrous, lack sweetness and not contain their optimal concentration of nutrients. They should be free of soft spots, bruises and darkened “eyes,” all of which may indicate that the Pineapple is past its prime. Avoid Pineapples with dry brown leaves because they will have a very sour taste. The flesh of the Pineapple darkens in color as it becomes overripe, an indication of the formation of free-radicals. Overripe Pineapples should not be eaten.

If Pineapples are heavy for their size and have the sweet aroma of Pineapple, they are ready to eat. Since Pineapples do not ripen after they have been picked, be sure to select a ripe one.

2. the best way to store pineapple

Proper storage is an important step in keeping Pineapples fresh and preserving their nutrients, texture and unique flavor.

Pineapples continue to respire even after they have been harvested. The faster they respire, the more the Pineapples interact with air to produce carbon dioxide. The more carbon dioxide produced, the more quickly they will spoil. Pineapples kept at a room temperature of approximately 68°F (20°C) give off carbon dioxide at a rate of 24 mg per kilogram every hour. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different fruits, see page 341.)

Pineapples are most flavorful when served at room temperature. Although refrigeration may enhance the freshness of Pineapples, it will also cause them to get “chill injury” and lose some of their flavor compounds. If you do refrigerate your Pineapple, place it on the top shelf, which is the warmest part of the refrigerator (over 50°F/10°C).

Avoid storing Pineapples in sealed plastic bags. The combination of limited oxygen exchange and the excessive amounts of ethylene gas that the Pineapples naturally produce under these conditions will cause them to rot.

While Pineapples that are stored at room temperature will have more flavor than those stored in the refrigerator, they will have a shorter shelf life. They will remain fresh for 3 days, while those stored in the refrigerator can last for up to 5 days.

Pineapples can bruise easily, so handle them with care.

3. the best way to prepare pineapple

Properly preparing Pineapples helps ensure that they will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Pineapples can be cut and peeled in a variety of ways. Regardless of how you proceed, the first step is always to remove the crown and the base of the fruit with a knife.

Cut off and discard both ends of the Pineapple. Stand Pineapple up on one end on the cutting board and cut off peel by going around Pineapple. If the Pineapple has deep eyes, remove them with the tip of a knife. Cut Pineapple into fourths lengthwise and cut out core from each section. Slice each section lengthwise in half or into thirds. Cut across slices into desired size.

You can also use Pineapple corers that are available in kitchen-supply stores. While they provide a quick and convenient method for peeling and coring Pineapples, they can result in a large amount of wasted fruit since they often cannot be adjusted for different size fruit. Some markets offer devices that will peel and core the Pineapple, but this process may waste a lot of fruit.

I have discovered that Pineapples retain their maximum amount of nutrients and their best taste when they are fresh and not prepared in a cooked recipe. That is because their nutrients—including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes—are unable to withstand the temperature (350°F/175°C) used in baking. So that you can get the most enjoyment and benefit from fruit, I created quick and easy recipes, which require no cooking. I call them “No Bake Recipes.”

Here are questions that I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Pineapple:

Q If I wanted to take advantage of bromelain’s enzyme activity, how much before or after eating a meal should I eat Pineapple?

A The time frame for digestion of our food varies greatly. Pure proteins typically move through our stomach and small intestine in the two to five hour range. Bromelain is a protein-digesting enzyme, so one to two hours before or after eating (so that it’s not sitting in our stomach or small intestine right next to the proteins in our food) would be the best way to make use of its anti-inflammatory benefits.

Q Does the high heat involved in canning destroy the beneficial enzymes in Pineapple? If so, is canned Pineapple not one of the World’s Healthiest Foods?

A That’s a great question you ask since it brings up the definition of a healthy food in general as compared more specifically to a World’s Healthiest Food.

It is true that the canning process does destroy the activity of the bromelain enzyme and reduces the content of other nutrients as well. The nutrient loss that occurs with canning is why I prefer fresh fruit to canned fruit. Fresh fruit is more of a whole food if we include as part of the definition of a whole food one that has the least amount of processing. (It is rare that no processing would occur to a food, as you could even say that the very act of picking the Pineapple is actually processing and takes away from its wholeness—but that’s a whole other philosophical conversation.)

But should the loss of some nutrients disqualify the canned Pineapple from being a World’s Healthiest Food? I don’t think so. If I apply the standard that processing affects the nutrient content of a food and therefore disqualifies it, then I would have to apply that to all of the World’s Healthiest Foods and object to cooking, even light cooking of vegetables, which I think is appropriate. Canned Pineapple is still rich in nutrients, and I would rather see people eat canned Pineapple than not enjoy this food at all. In my view, choosing canned Pineapple that is organic and not packed with sugar water would also make it closer to a whole food.

Fresh Pineapple is rich in bromelain, a group of sulfur-containing proteolytic (protein-digesting) enzymes that not only aid digestion but can effectively reduce inflammation and swelling. A variety of inflammatory agents are inhibited by the action of bromelain. In clinical human trials, bromelain has demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory effects, reducing swelling in inflammatory conditions such as acute sinusitis, sore throat, arthritis and gout, and speeding recovery from injuries and surgery. To maximize bromelain’s anti-inflammatory effects, Pineapple should be eaten alone between meals or its enzymes will be used up digesting food.

Pineapple is an excellent source of vitamin C, the body’s primary water-soluble antioxidant, which defends all aqueous areas of the body against free-radicals that attack and damage cells. Free radicals have been shown to promote the artery plaque build-up of atherosclerosis and diabetic heart disease, cause the airway spasm that leads to asthma attacks, damage the cells of the colon so that they become colon cancer cells and contribute to the joint pain and disability seen in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. This would explain why diets rich in vitamin C have been shown to be useful for preventing or reducing the severity of all of these conditions. In addition, vitamin C is vital for the proper function of the immune system, making it a nutrient helpful for the prevention of recurrent ear infections, colds and flu.

Pineapple is an excellent source of the trace mineral manganese, which is an essential cofactor in a number of enzymes important in energy production and antioxidant defenses. For example, the key oxidative enzyme, superoxide dismutase, which disarms free-radicals produced within the mitochondria (the energy production factories within our cells), requires manganese. In addition to manganese, Pineapple is a good source of thiamin, a B vitamin that acts as a cofactor in enzymatic reactions central to energy production.

Pineapple is also a concentrated source of many other nutrients providing additional health-promoting benefits. These nutrients include heart-healthy dietary fiber and vitamin B6 and free-radical-scavenging copper. Since one cup of Pineapple contains only 76 calories, it is an ideal food for healthy weight control.

Virtually all living things—including those we cook and eat—contain enzymes. Acting as the spark plugs for the vast majority of chemical reactions that make life possible, enzymes are a sine qua non for life.

Although most food eaten in the United States has been cooked, which inactivates the enzymes it contains, all the plant and animal foods in our meals are derived from once-living, enzyme-abundant things.

Over 2,500 different kinds of enzymes are found in living things. All enzymes are very special kinds of proteins that act as catalysts. Enzymes give our body chemistry its vitality, literally giving our metabolism a jumpstart. Plus, as molecules that enable the breaking down of our food, they also play a critically important role within our digestive system. Enzymes in our saliva allow us to break apart starches. Enzymes in our stomach help us break apart proteins. Enzymes in our intestines help us break apart fats, proteins and carbohydrates of all kinds.

When we eat fresh, uncooked foods, those foods can still contain active enzymes. When we chew a freshly picked leaf of lettuce, we break the cells in the leaf apart, releasing its nutrients, including enzymes. Enzymes are not automatically destroyed by the acids or temperatures in our digestive tract. Enzymes in the stomach—called gastric enzymes—are specially designed to function in the stomach’s extremely acidic conditions and are critical to our health. Our bodies can overheat from fever, extreme exercise or summer weather but not to temperatures that will prevent the enzymes inside us from continuing to function.

Our digestive tract has specialized areas for absorbing large molecules, including enzymes, from food into our bloodstream. These areas house our M cells, specialized cells designed to selectively deliver large molecules from our intestines into our cells and bloodstream. The passing of enzymes from a mother to her nursing newborn is a good example of this M-cell function. A mother’s milk contains the milk sugar, lactose. An enzyme called lactase is needed to digest lactose, but an infant’s body is not yet capable of manufacturing this enzyme. So, the mother sends lactase along with her milk, enabling the baby to digest and absorb its lactose.

Ordinarily, we cook food at temperatures at least twice that of normal body temperature. For this reason, fresh, raw plant foods are our primary source of food enzymes. (Due to their high potential for bacterial contamination, most animal foods would be too risky for us to eat raw.) While there have been no largescale, controlled studies to document the impact of enzyme-containing, fresh, raw plant foods on digestion and health, practitioners in the fields of complementary, natural and functional medicine have long advocated for the inclusion of fresh, organic, raw plant foods in the diet.

Plant foods contain many of the same enzymes that humans use to metabolize different kinds of macronutrients. Proteases and peptidases, which help digest protein; lipases, which help digest fat; and cellulases and saccharidases, which help digest starches and sugars, are examples of the kind of digestive enzymes that would normally be secreted in our digestive tract or in nearby organs like the pancreas or liver. However, these same digestive enzymes can be found in the plant foods that we eat.

Like humans, plants must protect themselves against oxygen-related damage, and they depend on enzymes to help them do so. A recently germinated sprout, for example, starts to generate many new oxidative enzymes in preparation for its journey up through the soil and into the open air. Superoxide dismutase and catalase are examples of oxidative enzymes that occur in higher concentrations in young plant sprouts than in the older, mature leaves. Glutathione peroxidase is another example of an important oxidative enzyme that is found in the human body and in the plants we eat.

Digestive enzymes play an integral role in the digestion of proteins, fats and carbohydrates since they catabolize these macronutrients into smaller molecules, which can be absorbed in the intestines. Our optimal physiological functioning depends upon the proper digestion and absorption of these nutrients.

Certain enzymes, such as bromelain (found in pineapple), have anti-inflammatory properties. Bromelain seems to confer anti-inflammatory protection through a variety of mechanisms. It is thought to inhibit intermediates of the clotting cascade, increase fibrinolysis (the dissolution of clots) and reduce the production of inflammatory molecules such as bradykinin.

Enzymes support the immune system in a few different ways. Since enzymes can work on substrates wherever the substrate is found, some of their targets include molecules other than the macronutrients associated with food. For example, protease enzymes can break apart the proteins that are found in unwanted bacteria and therefore reduce our risk of infection. In addition, the enzyme bromelain has been found to increase the production of a host of different immune system messenger molecules, including cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1-beta and interleukin-6.

highlights

While Kiwifruit are associated with New Zealand, they actually originated in China, where they have long been considered a delicacy. They were brought to New Zealand by missionaries in the early 20th century and known as Chinese Gooseberries. They were introduced into North America and other areas of the world in the 1960s when they also took on their new name in honor of the national bird of New Zealand, the kiwi. One of the traditional names for them in Chinese translates into “wonder fruit,” which is definitely one way to describe these little fruits; underneath their brown fuzzy exterior you’ll find bright emerald green or golden yellow flesh that has a creamy consistency and an invigorating, unique taste reminiscent of a combination of strawberries, pineapple and bananas.

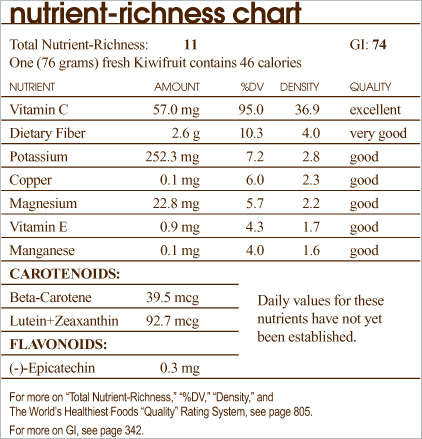

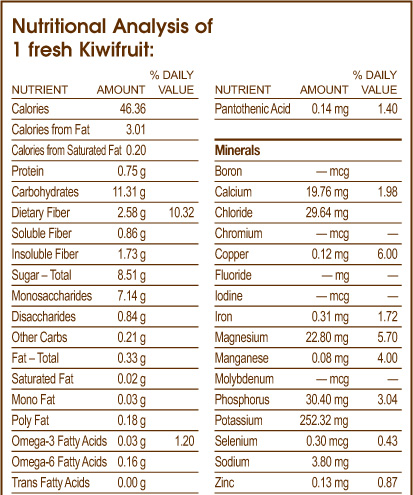

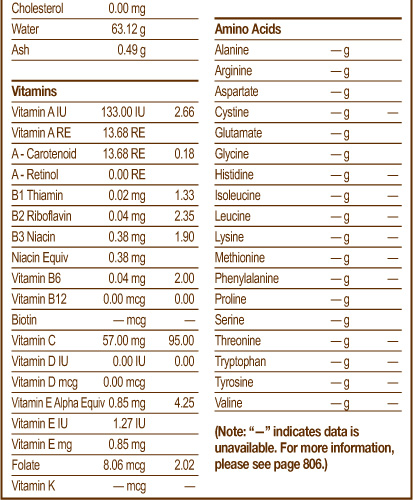

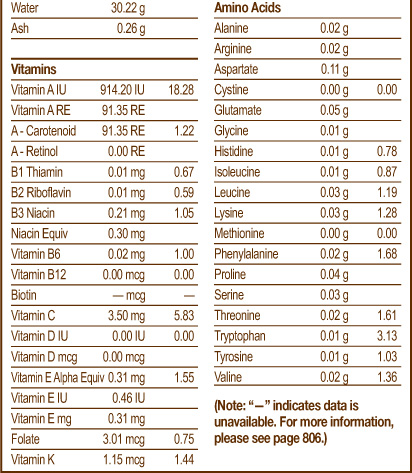

You may be surprised to learn that Kiwifruit actually contain more vitamin C than an equivalent amount of orange! Their rich concentration of vitamin C, combined with the health-promoting carotenoids and flavonoids found in Kiwifruit, provide powerful antioxidant protection against the oxidative damage caused by free-radicals. They are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are nutritious and taste great, but also because they are low in calories: one Kiwifruit contains only 46 calories! (For more on the Health Benefits of Kiwifruit and a complete analysis of its content of over 60 nutrients, see page 366.)

The most common species of Kiwifruit is Actinidia deliciosa, also commonly known as Hayward. This is the type that you most often find in supermarkets, the ones with fuzzy brown skin and emerald green flesh.

With the growing interest in Kiwifruit, other species are beginning to appear in supermarket produce sections and farmer’s markets. They include Actinidia arguta (Hardy Kiwi) and Actinidia polygama (Silvervine Kiwi), two smooth-skinned varieties that are the size of cherries and have a golden yellow-green hue.

Although Kiwifruit are commonly available throughout the year because they can be kept in cold storage for up to 10 months, the peak of their season in the United States runs from November through May. Kiwifruit from New Zealand are available from June through October. These are the months when their concentration of nutrients and flavor are highest, and their cost is at its lowest.

Kiwifruit are one of the foods most commonly associated with allergic reactions in individuals with latex allergies. (For more on Latex Food Allergies, see page 722.)

Enjoying the best tasting Kiwifruit with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 3 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

1. the best way to select kiwifruit

For the best tasting Kiwifruit, look for ones that yield to gentle pressure, a sign that they are fully ripe. Fully ripened Kiwifruit not only taste best but are also highest in nutritional value. Concentrations of vitamins and health-promoting phytonutrients, many of which can act as powerful antioxidants, are at their peak when Kiwifruit are ripe. By selecting the best tasting Kiwifruit, you will also be enjoying ones with the highest nutritional value. As with all fruits, I recommend selecting organically grown Kiwifruit whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid Kiwifruit that are shriveled or have bruised or damp spots. Overripe Kiwifruit will be very soft, may be brown in color and will have reduced nutritional value. Overripe Kiwifruit that have turned brown should not be eaten as they may contain free-radicals.

Kiwifruit that yield to gentle pressure will have reached the peak of their sweetness and are ripe and ready to eat.

2. the best way to store kiwifruit

Proper storage is an important step in keeping Kiwifruit fresh and preserving their nutrients, texture and unique flavor.

Kiwifruit continue to respire even after they have been harvested. The faster they respire, the more the Kiwifruit interact with air to produce carbon dioxide. The more carbon dioxide produced, the more quickly they will spoil. Kiwifruit kept at a room temperature of approximately 68°F (20°C) give off carbon dioxide at a rate of 19 mg per kilogram every hour. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different fruits, see page 341.) Kiwifruit can be either stored at room temperature or in the refrigerator, depending on your personal preference.

Kiwifruit will become sweet and juicy (ripen) at home after they have been purchased, if they have not been picked too green. Kiwifruit can be ripened by leaving them at room temperature from 2 to 7 days. Be sure not to expose them to sunlight or heat. If you don’t want them to ripen too quickly, store them away from all other fruits and vegetables since proximity to these foods will hasten the ripening process.

Another very natural way to ripen Kiwifruit is to place them in a paper bag for 2 to 3 days. The paper bag traps the ethylene gas produced by the Kiwifruit. The ethylene gas helps the Kiwifruit to ripen more quickly, while the paper bag allows for healthy oxygen exchange through the bag. Keep the paper bag in a dark, cool, ventilated place as excessive heat will cause the Kiwifruit to rot rather than ripen. To speed up the ripening, add a banana, apple or avocado to the bag.

Avoid storing Kiwifruit in sealed plastic bags or restricted spaces where they touch each other. Limited oxygen exchange and excessive amounts of ethylene gas naturally produced by the Kiwifruit will cause them to rot.

Kiwifruit are delicate and bruise easily, so handle them with care.

3. the best way to prepare kiwifruit

Properly preparing Kiwifruit helps ensure they will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Cut off the ends of the Kiwifruit, peel with a paring knife and then cut into pieces. Peeling is easier when ends are cut off first.

Alternatively, cut the Kiwifruit in half horizontally and scoop out the flesh with a spoon. Or you can wash off the brown fuzz before cutting and eat the Kiwifruit skin and all.

Kiwifruit should be eaten soon after cutting. Cutting activates enzymes (actinic and bromic acids) that act as food tenderizers and may result in the whole Kiwifruit becoming very soft soon after it has been cut.

If you are adding Kiwifruit to a fruit salad, you should do so at the last minute to prevent the other fruits from becoming too soggy from the enzymes found in Kiwifruit.

I have discovered that Kiwifruit retain their maximum amount of nutrients and their best taste when they are fresh and not prepared in a cooked recipe. That is because their nutrients—including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes—are unable to withstand the temperature (350°F/175°C) used in baking. So that you can get the most enjoyment and benefit from fruit, I created quick and easy recipes, which require no cooking. I call them “No Bake Recipes.”

Here are questions that I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Kiwifruit:

Q How does the small hardy Kiwifruit compare to the large fuzzy ones?

A Hardy Kiwifruit are becoming more and more popular. While it is difficult to find them in many markets because they are very delicate and don’t hold up as readily to shipping as larger Kiwifruit, some specialty markets and farmer’s markets offer them. In addition, more and more home gardeners are growing their own. While I haven’t seen a nutritional comparison between hardy and larger-sized Kiwifruit, I assume that they are very similar and even offer a bit more fiber because their thin skin is readily edible, unlike the skin of larger Kiwifruit’s skin.

Q I don’t like the texture of Kiwifruit. Since it is such a healthy fruit, can I juice it instead?

A Kiwifruit juice will not provide all of the nutrients that whole Kiwifruit does. No juice does. That’s because the percentage of nutrients retained in a pulp-free juice is usually lower than the percentage retained in the pulp. Unless you take all of the pulp that is separated out from your juice and add it back into your juice before you drink it, you are not getting anywhere close to all of the nutrients that you would from eating the whole fruit. For example, virtually all of the fiber remains with the pulp and a significant amount of betacarotene does as well. Yet, if you want to enjoy Kiwifruit and don’t like eating the whole fruit then by all means go ahead and make juice since you will still attain a wealth of nutrients. Try the Kiwi Cantaloupe Soup (page 365) as an alternative way to enjoy Kiwifruit.

Q Can you freeze Kiwifruit?

A You can freeze almost any fruit, although it may not maintain the same taste and texture of the fresh fruit. But if you have more Kiwifruit than you can eat or if you want to freeze them for a recipe (smoothies, for example), by all means go ahead. I would probably suggest peeling them first (unless you enjoy the skin, as some people do) as it would be easier than peeling them once they have been frozen.

Q I have a latex allergy and was recently told that Kiwifruit and latex are somewhat related. Can you clarify?

A Between 30–50% of individuals who have allergies to latex may also have allergic reactions to certain plant foods including Kiwifruit, avocados, bananas and chestnuts. Currently, the most conclusive evidence suggests that foods that cross-react with latex are those that contain enzymes called chitinases, which have similar protein structures to those found in latex. Consult your healthcare practitioner for more guidance on this topic.

The protective properties of Kiwifruit have been demonstrated in a study with 6- and 7-year-old children in northern and central Italy. The more Kiwi or citrus fruit these children consumed, the less likely they were to have respiratory-related health problems including wheezing, shortness of breath or night coughing. The antioxidants found in these fruits may be involved in their health-promoting properties.

The small Kiwifruit may be a big friend to your heart. Kiwifruit are an excellent source of vitamin C, an antioxidant that helps to reduce oxidation of LDL cholesterol; LDL oxidation is one of the first steps in the development of atherosclerosis. Additionally, dietary fiber, a nutrient of which Kiwifruit are a very good source, has been shown to reduce high cholesterol levels, which may reduce the risk of heart disease and heart attack. Kiwifruit are also a good source of potassium and magnesium, two minerals important for regulating blood pressure. Yet, it may not be just their individual components that make Kiwifruit so heart-healthy but the synergy of the whole matrix of nutrients found in these fruits; recent research showed that individuals who ate two to three Kiwifruit per day reduced their platelet aggregation response (potential for blood clot formation) and triglyceride levels.

Kiwifruit has fascinated researchers for its ability to protect DNA in human cells from oxygen-related damage. Researchers are not yet certain which compounds in Kiwi give it this protective antioxidant capacity, but they are sure that this healing property is not limited to those nutrients most commonly associated with Kiwifruit, including its vitamin C content. Since Kiwifruit contain a variety of flavonoids and carotenoids that have demonstrated antioxidant activity, these phytonutrients may be responsible for Kiwi’s DNA protection.

The vitamin C contained in Kiwifruit is the primary water-soluble antioxidant in the body, neutralizing free-radicals that can cause damage to cells and lead to inflammation. Kiwifruit is also a good source of copper and manganese, which are cofactors in the powerful antioxidant superoxide dismutase, as well as vitamin E, an important fat-soluble antioxidant. This combination of both fat- and water-soluble antioxidants makes Kiwi able to provide free-radical protection on all fronts.

Since each Kiwifruit contains only 46 calories, it is an ideal food for healthy weight control.

Seasons form the natural backdrop for eating. All of the World’s Healthiest Foods are seasonal. Imagine a vegetable garden in the dead of winter. Now imagine this same garden on a sunny, summer day. How different things are during these two seasons of the year! For ecologists, seasons are considered a source of natural diversity. Changes in growing conditions from spring to summer or fall to winter are considered essential for balancing the earth’s resources and its life-forms. But today it’s so easy for us to forget about seasons when we eat! Modern food processing and worldwide distribution of food make foods available year-round, and grocery stores shelves look much the same in December as they do in July.

In a research study conducted in 1997 by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food in London, England, significant differences were found in the nutrient content of pasteurized milk in summer versus winter. Iodine was higher in the winter; betacarotene was higher in the summer. The ministry discovered that these differences in milk composition were primarily due to differences in the diets of the cows. With more salt-preserved foods in winter and more fresh plants in the summer, cows ended up producing nutritionally different milks during the two seasons. Similarly, researchers in Japan found three-fold differences in the vitamin C content of spinach harvested in summer versus winter.

What does this mean for you? Eat seasonally! To enjoy the full nourishment of food, you should make your menu a seasonal one. In different parts of the world, and even in different regions of one country, seasonal menus can vary. But here are some overriding principles you can follow to ensure optimal nourishment in every season:

• In spring, focus on tender, leafy vegetables that represent the fresh new growth of this season. The greening that occurs in springtime should be represented by greens on your plate, including Swiss chard, spinach, romaine lettuce, fresh parsley and basil.

• In summer, stick with light, cooling foods as defined in traditional Chinese medicine. These foods include fruits like strawberries, apples, pears, and plums; vegetables like summer squash, broccoli, cauliflower and corn; and spices and seasonings like peppermint and cilantro.

• In fall, turn toward the more warming, autumn harvest foods, including carrots, sweet potatoes, onions and garlic. Also emphasize the more warming spices and seasonings including ginger, peppercorns and mustard seeds.

• In winter, turn even more exclusively toward warming foods. Remember the principle that foods taking longer to grow are generally more warming than foods that grow quickly. All of the animal foods fall into the warming category including fish, chicken, beef, lamb and venison. So do most of the root vegetables, including carrots, potatoes, onions and garlic. Eggs also fit in here, as do corn and nuts.

In all seasons, be creative! Let the natural backdrop of spring, summer, fall and winter be your guide.

As a general rule, it is true that our metabolism slows down somewhat as we age. For this reason, it is also generally true that we need fewer calories. For example, as Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, and author of the book, “What to Eat,” has noted, a woman in her 30s may need 2,400 daily calories, while at 50 she’ll need about 2,100 and at 70, only 1,500 while a teenage boy may need 3,000 calories each day, but when he’s 50 he’ll only need 2,400 and when he’s 70 he’ll only need 2,200.

Calorie needs depend upon age but also upon activity level. One of the best ways to balance your calorie needs is to become more physically active. You definitely need to change your diet; you have to eat more nutrient-rich foods and less nutrientpoor foods.

Requirements for some nutrients increase for adults over 50. These include calcium for strong bones, vitamin D for calcium absorption, B vitamins such as B6 for a healthy heart and protection against the hardening of the arteries (by helping to keep homocysteine levels low) and antioxidant-rich foods to help prevent age-related cataracts and macular degeneration. For food sources of calcium, see page 738; for food sources of vitamin D, see page 796; for food sources of vitamin B6, see page 790; for food sources of antioxidants, see pages 735 and 804.

Research suggests that animals live 50% longer when they consume nutrient-rich foods without excess calories. Reducing caloric intake can lead to nutrient deficiencies if the food you eat is not highly nutrient-rich. By enjoying nutrient-rich World’s Healthiest Foods, you not only won’t ever feel hungry but you can eat large amounts of food at the same time that you are reducing your caloric intake. Enjoying nutrient-rich World’s Healthiest Foods is a great way to meet your nutritional needs as you age while taking in fewer calories to accommodate a slowing metabolism, making it much easier to maintain a healthy weight.

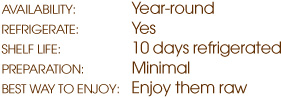

highlights

Oranges were once reserved for special occasions. In medieval times, Oranges and their blossoms were used on a couple’s wedding day, while in England, during the time of Queen Victoria, Oranges were presented as gifts during the Christmas holidays. Spanish explorers brought Oranges to Florida in the 16th century, while Spanish missionaries brought them to California in the 18th century, beginning their cultivation in the two states widely known for their Oranges. Historically, Oranges were also very expensive, but with advances in transportation and better means of utilizing their by-products, they are now affordable, available year-round and have become one of the world’s most popular fruits. Delightful as a snack or as a recipe ingredient, these sweet juicy fruits are easy to pack and fun to eat.

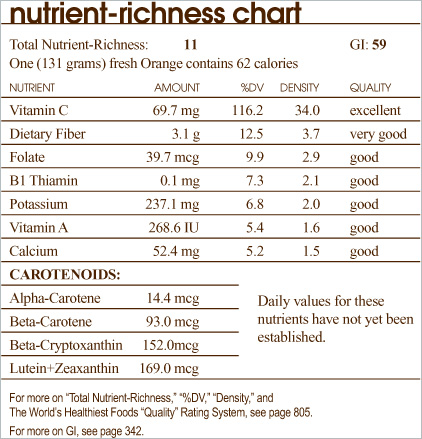

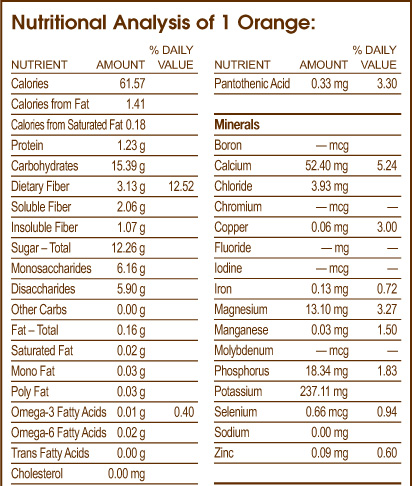

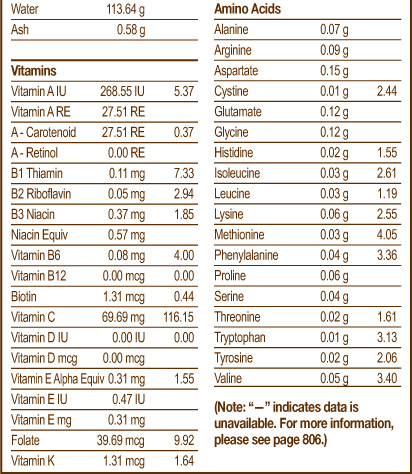

Oranges have been found to contain more than 60 flavonoids that provide powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant protection. These flavonoids work synergistically with vitamin C, of which Oranges are known to be a great source; vitamin C is the primary water-soluble antioxidant, providing protection against oxidative damage to cell structures, including DNA. These are just some of the reasons why Oranges can be an important part of your “Healthiest Way of Eating.” Oranges are not only nutritious and delicious, but they are also low in calories: one Orange contains only 62 calories! (For more on the Health Benefits of Oranges and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 372.)

Oranges originated thousands of years ago in Asia, in the region extending from southern China to Indonesia and spreading to India. They are classified into two general categories—bitter and sweet. Bitter Oranges (Citrus aurantium), such as Seville, are oftentimes used to make jam or marmalade, and their zest serves as the flavoring for liqueurs, such as Grand Marnier and Cointreau. Sweet Oranges are the ones most commonly found in the supermarket. Popular varieties of sweet Oranges (Citrus sinensis) include:

These medium- to large-size Oranges have smooth skin and a round or oval shape. They are the most commonly grown Oranges and can be peeled and eaten or squeezed for their juice. Florida Valencias are considered the best Oranges for juice.

These thick-skinned Oranges are distinguished by a characteristic “belly button” scar on the blossom end. They are seedless, and the inner fruit is easily segmented, making them ideal for eating. Squeeze Navel Oranges for their juice as needed because the juice tends to turn bitter over time.

Imported from Israel, they are similar to Valencias with a slightly sweeter flavor.

As their name implies, these Oranges have blood-red flesh and juice. Imported from the Mediterranean area, they are small- to medium-size Oranges with smooth or pitted skin that sometimes has a reddish hue.

Oranges are available year-round, although their peak season runs from winter through summer with seasonal variations between varieties:

Valencia Oranges – March through June

Navel Oranges – November through April

Jaffa Oranges – December through February

Blood Oranges – March through May

These are the months when their concentration of nutrients and flavor are highest, and their cost is at its lowest.

Oranges are one of the foods most commonly associated with allergic reactions. Conventionally grown Oranges often have a wax coating to help protect their surface and increase their shelf life. Avoiding the wax and the other compounds used on conventionally grown Oranges is one reason to choose organically grown Oranges whenever possible. (For more on Food Allergies, see page 719; and Wax Coatings, see page 732.)

Enjoying the best tasting Oranges with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 3 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

1. the best way to select oranges

For the best tasting Oranges, look for ones that are fully ripe as Oranges will not ripen after they have been picked. Fully ripened Oranges will also have the greatest concentration of nutrients, including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes. Ripe Oranges are heavy for their size. They will have higher juice content than ones that are spongy or lighter in weight. In general, smaller Oranges with thinner skins will be juicier than those that are larger in size. Oranges do not necessarily have to have a bright Orange skin to be good. Oranges that are partially green or have brown russeting may be just as ripe and tasty as those that are solid Orange in color. In fact, the uniform color of conventionally grown Oranges may be due to the injection of Citrus Red Number 2 (an artificial dye) into their skins at the level of 2 parts per million. As with all fruits, I recommend selecting organically grown Oranges whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid Oranges with soft spots or traces of mold.

Almost all Oranges are picked ripe. The best Oranges are heavy for their size.

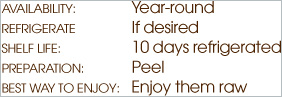

2. the best way to store oranges

Proper storage is an important step in keeping Oranges fresh and preserving their nutrients, texture and unique flavor.

Oranges continue to respire even after they have been harvested. The faster they respire, the more the Oranges interact with air to produce carbon dioxide. The more carbon dioxide produced, the more quickly they will spoil. Oranges kept at room temperature of approximately 68°F (20°C) give off carbon dioxide at a rate of 28 mg per kilogram every hour. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different fruits, see page 341.)

Refrigeration helps slow the respiration rate of ripe Oranges, retain their vitamin content and increase their storage life. Oranges are juicier at room temperature where they will store for approximately 5 days. If you have more Oranges than you can enjoy within a week, it is best to place them in the refrigerator where they will last for about 10 days.

The best way to store Oranges is to keep them loose rather than in a plastic bag or restricted space where they touch each other. The combination of limited oxygen exchange and the excessive amounts of ethylene gas produced under these conditions will cause them to rot.

3. the best way to prepare oranges

Properly preparing Oranges helps ensure that they will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Rinse Oranges under cold running water before peeling. (For more on Washing Fruit, see page 341.)

Thin-skinned Oranges can be easily peeled with your fingers. For easy peeling of the thicker-skinned varieties, first cut a small section of the peel from the top of the Orange. You can then either make four longitudinal cuts from the top to bottom and peel away these sections of skin, or starting at the top, peel the Orange in a spiral fashion.

Recipes often call for Orange juice. Oranges, like most citrus fruits, will produce more juice when they are not cold, so always juice them when they are at room temperature. To get the most juice out of an Orange, gently roll it on the counter top, applying soft pressure, before you cut and juice it.

Cut the Oranges in half and remove the visible seeds from the fruit before juicing or remove them from the juice after you are done juicing.

The juice can be extracted in a variety of ways. You can use a juicer or reamer or do it the old fashioned way, squeezing by hand.

Using a hand grater, grate the skin of the Orange; be careful to avoid the white membrane beneath the peel as it is bitter. Scrape the grated zest off the underside of the grater. Make sure that you use fruit that is organically grown since most conventionally grown fruits will have pesticide residues on their skin and are often coated with wax. If you use conventionally grown Oranges to make zest for your tea, you may find wax residues floating on top.

With a sharp knife, cut off thin pieces of Orange peel, getting as little of the white membrane as possible. Chop with a knife into desired size. Chopped Orange rind used to flavor sauces should be discarded once the sauce is done. Orange rind that is chopped very fine can be incorporated into a dish.

Cut the ends off a seedless Orange just far enough to expose the flesh. Place Orange cut end down and cut away as little of the peel as possible by following the Orange’s shape. Using a sharp knife, cut along the inside of the membranes that separate the Orange segments. Continue around entire Orange cutting out each section.

To eat as a snack, first wash the skin so that any dirt or bacteria residing on the surface will not be transferred to the fruit. Cut Oranges horizontally through the center. Cut the sections into halves or thirds, depending upon your personal preference.

I have discovered that Oranges retain their maximum amount of nutrients and their best taste when they are fresh and not prepared in a cooked recipe. That is because their nutrients—including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes—are unable to withstand the temperature (350°F/175°C) used in baking. So that you can get the most enjoyment and benefit from fruit, I created quick and easy recipes, which require no cooking. I call them “No Bake Recipes.”

In recent research studies, the healing properties of Oranges have been associated with a wide variety of phytonutrient compounds. These phytonutrients include citrus flavanones (types of flavonoids that include the compounds hesperidin and naringenin), anthocyanins, hydroxycinnamic acids and a variety of polyphenols. When these phytonutrients are studied in combination with Oranges’ vitamin C, the significant antioxidant properties of this fruit are understandable. An increasing number of studies have also shown that nutrients such as vitamin C are more readily absorbed when consumed together with the other biologically active phytonutrients contained in citrus fruits than when taken singly as supplements.

The flavonoids in Oranges have been shown to have anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor and blood clot-inhibiting properties.

Oranges are a concentrated source of many heart-healthy nutrients including vitamin C, fiber, folate, potassium and flavonoids. The flavonoid hesperidin has been singled out in phytonutrient research on Oranges and shown to lower high blood pressure as well as cholesterol in animal studies. It has also been found to have strong anti-inflammatory properties. Importantly, most of this phytonutrient is found in the peel and inner white pulp of the Orange, rather than in the flesh used for juice, so it’s important to eat the whole fruit rather than just drinking the juice.

Recent research has suggested that another class of compounds concentrated in citrus fruit peels, called polymethoxylated flavones (PMFs), has the potential to lower cholesterol more effectively than some prescription drugs, and without side effects. In this study, when animals with diet-induced high cholesterol were given the same diet containing PMFs, their blood levels of total cholesterol, VLDL and LDL (bad cholesterol) were reduced. Since these flavonoids are found in a much more concentrated amount in the peel, the best way to receive their benefits is by grating a tablespoon or so of the peel from a well-scrubbed organic Orange or tangerine each day and using it to flavor your meals.

Oranges are also a concentrated source of other nutrients providing additional health-promoting benefits. These nutrients include free-radical-scavenging vitamin A, bone-building calcium and energy-producing vitamin B1. Since a medium-size Orange contains only 62 calories, it is an ideal food for healthy weight control.

Making time for a healthy breakfast sets the stage for healthy eating throughout the day. For most people, breakfast time comes at least eight hours after their previous meal. So, in essence, while sleeping you have also been “fasting.” In fact, the word itself, when broken down, means to “break a fast.” When you wake up in the morning, your blood sugar may be low, and you may feel hungry.

Eating a breakfast that contains a good source of both protein and complex carbohydrates will allow your blood sugar to rise at a steady pace throughout the morning and provide your cells with the energy they need to carry out your morning activities.

Oatmeal topped with fruit and soymilk, along with a generous helping of nuts and seeds, is one good way to start the day. Or, try a poached egg over whole grain toast. For a super-quick “meal on the run,” spread some almond butter on a piece of whole grain toast and eat a piece of fruit along with it.

Try not to eat foods that are high in refined carbohydrates (for example, bagels, muffins or pastries made from white flour), first thing in the morning. These foods can cause a rapid spike in your blood sugar and may give you a short burst of energy but will cause you to “crash” a few hours later.

What happens if you skip breakfast? If you don’t give your body some fuel first thing in the morning, your blood sugar will continue to drop. In addition, you will begin using your nutrient stores to hold you over until your next meal. Over the next few hours, you may begin to feel sleepy or fatigued. And, by the time lunch rolls around, you will probably be so hungry that you will eat anything in sight! At this point, it will be more difficult to select healthy foods, as you will be mostly interested in grabbing something quick to satisfy your body’s need for fuel as soon as possible. These may be some of the reasons that studies have shown that eating breakfast regularly was a common characteristic of people who had lost weight. Researchers involved with the National Weight Control Registry say that there are several possible reasons that regular breakfast eating may be an essential behavior for weight loss maintenance:

• Eating breakfast may reduce the hunger experienced later in the day that leads to overeating.

• Breakfast eaters are able to better resist fatty and high-calorie foods throughout the day.

• Nutrients consumed at breakfast may give people a better ability to be more physically active.

Many people say that they are not hungry first thing in the morning, which makes it difficult to eat breakfast. Begin the habit of eating breakfast by starting with something very small, such as a half piece of whole grain toast with nut butter or a small bowl of whole grain cereal (with no added sugars!) with milk. As your body gets used to digesting food in the morning, you might notice you have a bigger appetite for breakfast.

There’s really no good research evidence to support the practice of food combining. However, many people have found food combining to be essential in their overall health, and many healthcare practitioners continue to support this practice despite the absence of research evidence. Sometimes proper food combining just means avoiding extremes. For example, some food combining advocates recommend eating protein alone or carbohydrates alone rather than protein and carbohydrates together. However, this goal is essentially impossible, since most vegetables, grains, nuts, seeds and legumes contain both proteins and carbohydrates. You would have to eliminate all of the above foods from your diet in order to avoid eating protein and carbohydrates together. However, large amounts of protein (like the 80+ grams of protein that would be found in a 12-ounce steak) together with large amounts of carbohydrates (like the 40+ grams of sugar found in a 16-ounce glass of orange juice) might be a taxing combination for your digestive tract, more difficult than either food alone. Nonetheless, I see the basic problem here as one of going to extremes (too much protein at once and too much sugar at once) rather than food combining.

highlights

Bring the luscious taste and sunlit color of the tropics to your table by adding a ripe Papaya to your meal. Papaya trees are actually herbs that grow 10 to 12 feet high and produce the sweet, refreshing fruit, which you can now find in most local markets. Combining Papayas with other tropical fruits, like bananas and pineapples, is just one way you can enjoy them. And don’t throw away those seeds. In some countries, they are used in place of black pepper; their peppery taste can be a great addition to salad dressings.

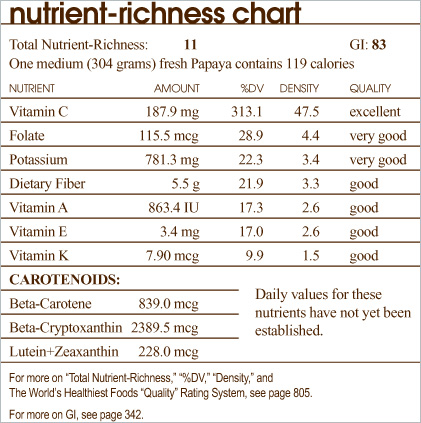

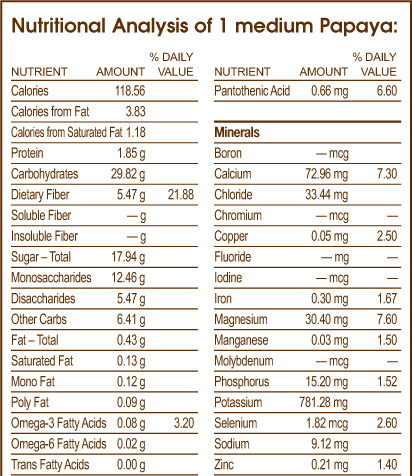

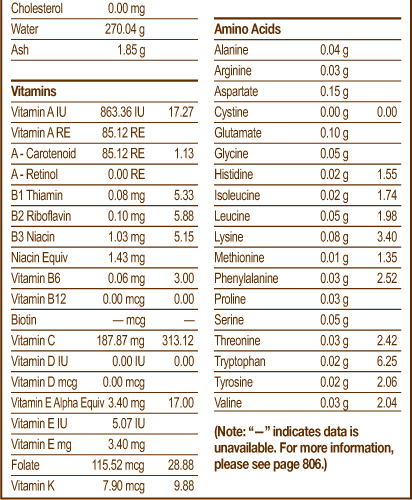

Papayas’ rich orange color reflects an abundance of betacarotene and beta-cryptoxanthin, two carotenoid phytonutrients that not only get converted into vitamin A, but also provide powerful antioxidant protection against the oxidative damage free-radicals that inflict on cell structures. Green unripe Papayas are also rich in a unique enzyme called papain, which helps in the digestion of proteins. Papayas are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” because they are not only nutritious, but also truly delicious. (For more on the Health Benefits of Papayas and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 378.)

Native to Central America, Papayas have a wonderfully soft, butter-like consistency and a deliciously sweet, musky taste. Botanically, they are known as Carica papaya. Inside the inner cavity of the fruit are black, round seeds encased in a gelatinous-like substance. Papayas’ seeds are edible with a peppery flavor. The most popular varieties of Papaya include:

Hawaiian grown Papayas are the ones most commonly found in local markets. They are a pear-shaped fruit with a green-yellow outer skin—which turns yellow-orange when ripe—and bright orange-gold flesh. They range from six to eight inches in length and weigh about one pound. Sunrise Solo and Strawberry Sunrise are two Hawaiian varieties. All Papayas that are not organically grown on the Big Island in Hawaii are from genetically modified (GMO) seeds.

These are much larger than Hawaiian Papayas and reach upwards of two feet in length and ten pounds in weight. Their skin is also green in color, but they are not as sweet as Hawaiian Papayas.

Although there is a slight seasonal peak in early summer and fall, Papaya trees produce fruit throughout the year.

Papayas are one of the foods most commonly associated with allergic reactions in individuals with latex allergies. Conventionally grown dried Papayas may be treated with sulfites, which may be problematic for some individuals. Papaya seeds are safe to eat in an amount proportional to the natural amount of fresh Papaya fruit being enjoyed. Problems with Papaya seeds discussed in the research have focused on high-dose, synthetic Papaya seed extracts; I don’t believe that these studies on laboratory animals apply to direct consumption of Papaya seeds. (For more on Latex Food Allergies, see page 722; and Sulfites, see page 729.)

Enjoying the best tasting Papaya with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 3 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

1. the best way to select papaya

The best tasting and most nutritious Papayas are those that are fully ripe. They have fully developed flavor and have the most concentrated amounts of nutrients. Unlike pineapples, you cannot use the smell of Papayas as a test for ripeness. Papayas that have patches of yellow color will take two to three more days to ripen. Fully ripe Papayas have yellow-orange skin and are slightly soft to the touch. Papayas with spotty coloring usually have more flavor. Since this is when their vitamins and powerful antioxidants are at their peak, by selecting ripe Papayas you will also be enjoying those with the highest nutritional value. Green (unripe) Papayas make a wonderful salad. They contain papain and are therefore good for digestion. As with all fruits, I recommend selecting organically grown varieties whenever possible. (For more on Organic Foods, see page 113.)

Avoid overripe Papayas, which become mushy, have more of an acidic taste and have begun to lose their nutritional value. Avoid those with black spots on the outside as they can penetrate the skin of the Papaya and negatively affect its taste. Also, avoid those that are bruised or overly soft. Do not purchase Papayas that are totally green or overly hard unless you are planning on making a green Papaya salad; they will not ripen when picked too green.

Yellow-orange Papayas that are slightly soft to the touch are ready to eat.

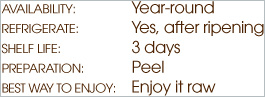

2. the best way to store papaya

Proper storage is an important step in keeping Papayas fresh and preserving their nutrients, texture and unique flavor.

Papayas continue to respire even after they have been harvested. The faster they respire, the more the Papayas interact with air to produce carbon dioxide. The more carbon dioxide produced, the more quickly they will spoil. Papayas kept at a room temperature of approximately 68°F (20°C) give off carbon dioxide at a rate of 80 mg per kilogram every hour. (For a Comparison of Respiration Rates for different fruits, see page 341.) Refrigeration helps slow the respiration rate of ripe Papayas, retain their vitamin content and increase their storage life.

Store fully ripened, but not unripened, Papayas in the refrigerator. While Papayas that are stored properly will remain fresh for up to 3 days, if they are not stored properly, they will only last about 1-2 days.

Papayas will become sweet and juicy at home if they have not been picked too green. Papayas are one of the few fruits that will ripen after they have been picked. Papayas are not ripe if they are hard and green. Unripe Papayas can be left at room temperature where they will ripen in 2–3 days. Don’t refrigerate Papayas until they are ripe; they will not ripen in the refrigerator. Place Papayas on a flat surface with space between the fruit. It is best to turn them occasionally so that they will ripen evenly. Once their skin turns yellow-orange and they yield to gentle pressure, they are ripe and ready to eat. If you will not be consuming them immediately after they have ripened, place them in the refrigerator.

Another natural way to ripen Papayas is to place them in a paper bag for 2 to 3 days. The paper bag traps the ethylene gas produced by the Papayas. The ethylene gas helps them to ripen more quickly, while the paper bag allows for healthy oxygen exchange through the bag. Keep the paper bag in a dark, cool place as excessive heat will cause the Papayas to rot rather than ripen. Turn Papayas occasionally. Adding a banana, apple or avocado to the bag will speed up the ripening because they increase the amount of ethylene gas in the bag.

Avoid storing Papayas in sealed plastic bags or restricted spaces where they touch each other. The combination of limited oxygen exchange and the excessive amount of ethylene gas that the Papayas naturally produce under these conditions will cause them to rot.

Yes, but they are very perishable and do not store well, so it is best to eat them as soon as possible.

Handle Papayas with care as they are a delicate fruit and bruise easily.

3. the best way to prepare papaya

Properly preparing Papaya helps ensure that it will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Rinse Papaya under cold running water before cutting. (For more on Washing Fruit, see page 341.)

One of the easiest (and most delightful) ways to eat Papaya is to eat it just like a melon. After washing the fruit, cut it lengthwise, scoop out the seeds and eat the flesh with a spoon.

To cut Papaya into smaller pieces for fruit salad or recipes, first peel it with a paring knife and then cut into the desired size and shape. You can also use a melon baller to scoop out the fruit of a halved Papaya. If you are adding it to a fruit salad, you should do so just before serving as it tends to cause the other fruits to become very soft.

Avoid the use of uncooked Papaya in gelatin recipes as the enzymes in Papaya prevent it from gelling.

I have discovered that Papaya retains its maximum amount of nutrients and its best taste when it is fresh and not prepared in a cooked recipe. That is because its nutrients—including vitamins, antioxidants and enzymes—are unable to withstand the temperature (350°F/175°C) used in baking. So that you can get the most enjoyment and benefit from fruit, I created quick and easy recipes, which require no cooking. I call them “No Bake Recipes.”

Unripe green Papaya contains papain, a proteolytic enzyme that is able to digest proteins; papain is well-known as a digestive enzyme and taken as a dietary supplement. Not only is it used to aid digestion, but natural healthcare practitioners sometimes recommend it when a person has allergic reactions to food since some of these reactions are thought to be caused by undigested protein. It may also be because of its papain that one of the traditional uses of Papaya in Central America is to eradicate dysentery infections caused by Entamoeba histolytica.

In addition to papain, Papaya also contains chymopapain. This protein-digesting enzyme has been shown to help lower inflammation and improve healing from burns. In addition, the antioxidant nutrients found in Papaya, including vitamin C, vitamin E and betacarotene, are very good at reducing inflammation. This may explain why people with diseases that get worse with inflammation—such as asthma, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis—find that the severity of their condition is reduced when they get more of these nutrients.

Papaya is rich in the carotenoids betacarotene and beta-cryptoxanthin. Not only are these carotenoids considered to be “pro-vitamin A” nutrients because they are converted into vitamin A in the body, but they have powerful antioxidant activity as well. Both of these functions make them important nutrients for promoting lung health.