Q Why is Tofu white?

A Actually, not all Tofu is white. The color of Tofu depends on several key factors. First is the type of soybean (white-eyed or black-eyed) used as the Tofu’s starting point. The white-eyed soybeans used for production of most Tofus in the U.S. are off-white, beige and slightly grayish in color. During the production of Tofu, however, following cooking, the outer husk is removed from the creamy inner part and along with the husk goes some of the non-white color. What’s left is a lighter, whiter-colored product.

Q Are there any dairy products used in the making of Tofu? I ask because I am sensitive to dairy.

A Tofu cheese and soy cheese very often contain casein, a milk protein found in cow’s milk, as it is used to help create the foods’ consistency. Yet, blocks of Tofu themselves generally don’t contain casein. The coagulated texture of Tofu is a result of the proteins in the soy itself as well as the addition of other ingredients such as magnesium or calcium sulfate.

Q There is research linking Tofu consumption with dementia. I get most of my protein from soybean foods and am now wondering whether I should keep eating Tofu. What’s your opinion about the research?

A I am currently only aware of two studies on the relationship between Tofu intake and cognitive function. Both are epidemiological studies that looked at large groups of individuals over long periods of time. In one of the studies, intake of Tofu more than twice a week during midlife (ages 40–55) was associated with increased prevalence of cognitive impairment and brain atrophy later in life (ages 70–90). It’s impossible to come to any hard and fast conclusions about Tofu and dementia from this kind of study. We simply don’t know enough about the study participants and what they did and didn’t have in common (besides their higher Tofu intake). In addition to the non-clinical nature of these studies, many health experts have reason to believe that Tofu intake can make individuals healthier in later life. Evidence from countries where soy products are eaten regularly throughout life suggests that late-life dementia is less problematic than it is in the United States. So I would say that the jury is definitely out here.

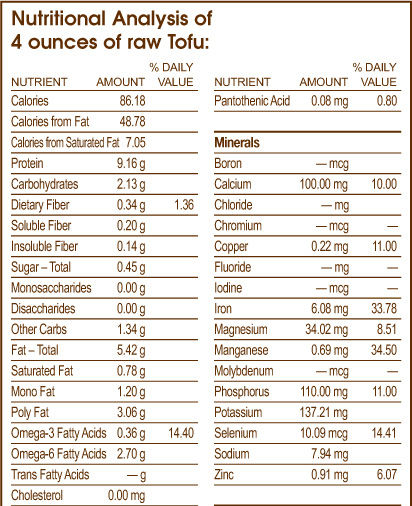

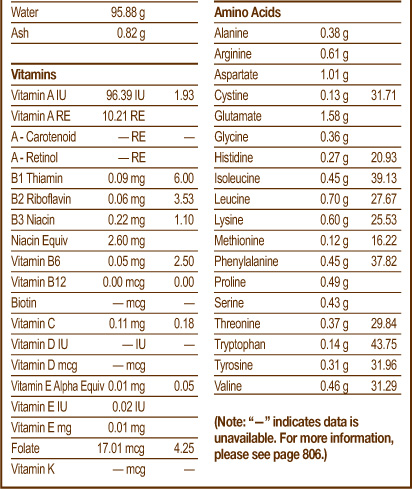

Q Is it true that “lite” Tofu has virtually no omega-3 fatty acids?

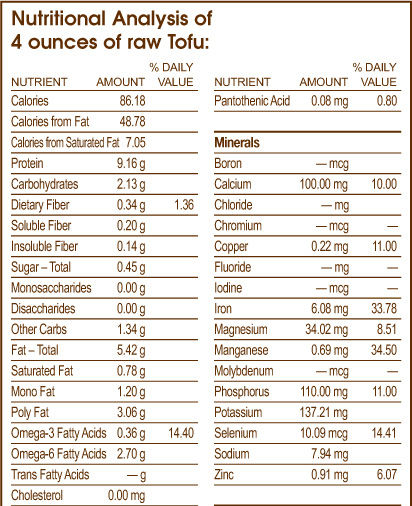

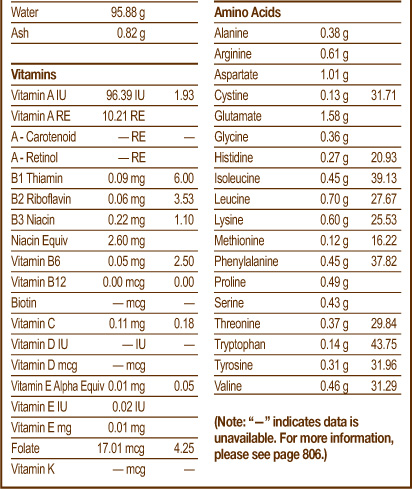

A Unfortunately, the listing for “lite” Tofu in the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference does not contain measurements of omega-3 fatty acids. Yet, it seems that “lite” Tofu has about one-third the amount of total polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) as regular Tofu. Assuming the reduction in total PUFAs is consistent across types of PUFAs, and based upon the Tofu profile featured on the World’s Healthiest Foods website, a “lite” version might have about 0.12 mg omega-3 fatty acids (in the form of linolenic acid). While this is a small amount, it still provides about 5% of the Daily Value for omega-3 fatty acids.

Q I see that you use silken Tofu in some of your recipes. What is it exactly?

A “Silken” refers to the texture and consistency of the Tofu. It is a form of Tofu that is velvety-smooth, which is what makes it so good for use in dips, puddings and sauces. If you are making a recipe that calls for silken Tofu and you can’t find it in your local supermarket or natural foods store, I would recommend that you purchase the least firm type of Tofu available. You may just need to adjust the recipe by adding more liquid—either water or oil—to achieve the smooth consistency that you would like the sauce to have.

Q Does eating Tofu burgers and hotdogs harm one’s health? I find that eating these foods is easier for me as they are very convenient, but if I knew they could be harmful, I would change my eating habits.

A While ideally I prefer food in more of its unprocessed state, in reality, given such circumstances as convenience, time, resources, variety and even taste, there are times when a food that is more processed is still a very good choice for a person’s diet. The foods that you mention are based upon whole foods, such as Tofu, vegetables and grains. If by eating these foods, you enjoy your food and find it easier to eat healthy, then I think that they can therefore be supportive of your health. I would just suggest two things: 1) purchase brands of these foods that feature organic ingredients and contain no/minimal additives, if possible and 2) eat them as part of a balanced diet.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Ways to Prepare Tofu

health benefits of tofu

Promotes Heart Health

Soy protein has been found to have many unique benefits. One of its most lauded benefits has been its contribution to heart health. Research on soy protein in recent years has shown that regular intake of soy protein can help lower total cholesterol levels by as much as 30%, lower LDL (“bad” cholesterol) levels by as much as 35–40%, lower triglyceride levels, reduce the tendency of platelets to form blood clots and possibly even raise levels of HDL (“good” cholesterol).

Tofu’s benefits on heart health are also related to it being a good source of omega-3 fatty acids, specifically alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). ALA is considered an “essential fatty acid” since the body cannot make it, so we must get it from our diet. ALA’s heart-health benefit comes not only from it being a precursor of EPA and DHA, the fatty acids found in cold-water fish that have trigclyeride- and blood pressure-lowering properties, but ALA itself has been found to be cardioprotective. It has been found to reduce levels of C-reactive protein, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In addition, it seems to have anti-arrhythmic properties, helping to stabilize the rhythmic beating of the heart.

Tofu is also a good source of other nutrients, such as selenium, calcium and magnesium, found to be important for heart health. For more details on the role of soy foods, such as Tofu, in cardiovascular health, please see Health Benefits of Soybeans on page 601.

Promotes Women’s Health

Most types of Tofu are enriched with calcium, which can help build bone density and prevent the accelerated bone loss for which women are at risk during menopause. Plus, it is a very good source of manganese and a good source of magnesium, copper and phosphorus, four other minerals important for promoting bone health.

Soy has also been shown to be helpful in alleviating symptoms associated with menopause. Soy foods, like Tofu, contain phytoestrogens, specifically the isoflavones genistein and daidzein. In a woman’s body, these compounds can dock at estrogen receptors and act like very weak estrogens. During perimenopause, when a woman’s estrogen fluctuates, rising to very high levels and then dropping below normal, soy’s phytoestrogens can help her maintain balance, blocking out estrogen when levels rise excessively high and filling in for estrogen when levels are low. When women’s production of natural estrogen drops at menopause, soy’s isoflavones may provide just enough estrogenic activity to prevent or reduce uncomfortable symptoms, like hot flashes. While the exact mechanisms through which they work their effects remain under investigation, the results of intervention trials suggest that soy isoflavones may also inhibit the resorption of bone and therefore help prevent postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Promotes Men’s Health

A study in China found that men consuming the most Tofu had a 42% lower risk of developing prostate cancer compared to those consuming the least. In other epidemiological studies, intake of soy isoflavones, like those found in Tofu, has also been linked to lower incidence of prostate cancer. For more details on the role of soy foods, such as Tofu, in men’s health, please see Health Benefits of Soybeans on page 601.

Promotes Energy Production

Tofu is not only a concentrated source of high quality protein, but is also a very good source of iron. While this important mineral plays many roles in the body, its most well-known one is being at the core of hemoglobin, a molecule essential to energy production since it is responsible for transporting and releasing oxygen throughout the body. Hemoglobin synthesis also relies on copper, so without this trace mineral, iron cannot be properly utilized in red blood cells. As is often the case in whole foods, Nature supplies complementary nutrients; Tofu is a good source of copper as well.

The Nutrition Facts panel, required on most packaged foods in the United States, is one of the most informative and detailed of such labels worldwide. Taking a little time to become familiar with it can be a very empowering way to evaluate and compare foods’ nutritional values. However, it is important to be aware that it is not comprehensive and that each person must interpret it individually.

The intent of the Nutrition Facts panel is to provide nutrition information, per serving of food, deemed pertinent to individuals with particular health conditions or nutritional needs, as well as to provide consumers with the means to make wise food choices. A few examples of the types of information provided include:

• cholesterol and saturated fat content of foods, meaningful to people concerned with cardiovascular health (which means virtually every American!)

• sodium content of foods, for individuals with sodium-sensitive high blood pressure

• dietary fiber content of foods, for those trying to increase their fiber intake (again, this should include virtually every American!)

• “Percentage Recommended Daily Intake” (or “%RDI”) for all recognized essential nutrients, based on a diet of a particular calorie count (usually 2000), which must be interpreted according to each individual’s average daily calorie intake

The Nutrition Facts panel provides a bounty of detail that pertains to “an average serving” of the food, the amount of which is defined at the top of the label. This means that the information provided must be quantitatively compared to how much you actually eat of that food. For example, if “an average serving” of a cracker product is FOUR crackers but you actually eat TEN crackers, you must remember that you are receiving 2.5 times as much of every nutrient on the label as is listed—sodium, cholesterol, fat, calories, vitamins, fiber, and so on.

The following nutrients are required on the Nutrition Facts panel if the nutrient is present above a certain defined minimum level per defined serving of the food:

• total calories

• total fat, calories from fat, calories from saturated fat, saturated fat, trans fats, polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat

• cholesterol

• sodium and potassium

• total carbohydrates, dietary fiber, soluble fiber, insoluble fiber, sugar, sugar alcohols (such as xylitol and sorbitol), and other carbohydrates (the difference between total carbohydrates and the sum of dietary fiber, sugars, and sugar alcohols)

• protein

• vitamin A and percent as betacarotene

• vitamin C, calcium, iron, and all other recognized essential vitamins and minerals

Despite the considerable detail provided by the Nutrition Facts panel, other useful information has not yet been included, such as:

• subtotals of essential omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fats

• the glycemic indices of carbohydrate-containing foods (to provide a comparative gauge of how quickly the food releases its energy)

All in all, however, the Nutrition Facts panel is an excellent tool that can help you make deliberate and informed decisions about the foods you choose to eat.

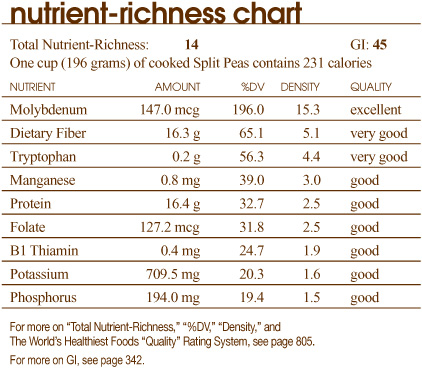

split peas

highlights

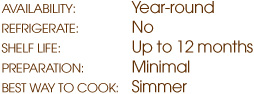

Split Peas are produced by drying the peapods of the fully mature garden pea. Peas are known scientifically as Pisum sativum and are believed to have been cultivated for more than 20,000 years! For thousands of years, it was dried Split Peas that were consumed rather than the fresh varieties of peas that we enjoy today. Although they belong to the same family as beans and lentils, they are usually distinguished as a separate group because of their usage and spherical shape. Their hardy flavor makes Split Pea soup a winter favorite and a nutritious and delicious addition to your “Healthiest Way of Eating.”

why split peas should be part of your healthiest way of eating

Split Peas are a great source of important heart-healthy nutrients including dietary fiber, potassium and folate. They also contain the isoflavone phytonutrient, daidzein, which acts as a phytoestrogen and promotes heart health. (Split Peas’ health benefits and nutritional profile are similiar to black beans. For more information, see page 615.)

varieties of split peas

Split Peas are available in green and yellow, with the former more popular in North America. Black-eyed peas are cream-colored with a black spot and are not related to Split Peas.

the peak season available year-round.

biochemical considerations

Same as black beans (see page 611).

the best way to select split peas

Same as black beans (see page 611).

the best way to store split peas

Same as black beans (see page 611).

the best way to prepare split peas

Same as black beans (see page 612) except that Split Peas require no soaking prior to cooking. Whole peas will require 8 hours of soaking.

the healthiest way of cooking split peas

For details about cooking, see black bean recipe (page 614). Split peas take about 30 minutes to cook.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Ways of Cooking Split Peas

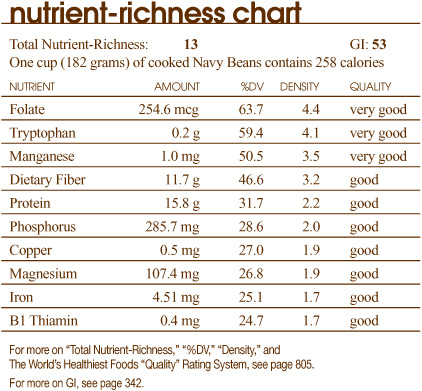

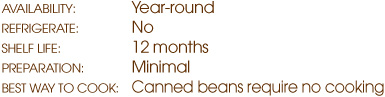

navy beans

highlights

These small white beans were once a staple on U.S. Naval ships; hence came the name, Navy Bean. Also known as Boston beans or Yankee beans, they are the beans of choice to make baked beans because they do not break up when they are cooked. Navy Beans are the official vegetable of Massachusetts, known as the baked bean state. The smooth texture and delicate flavor of Navy Beans is a great addition to your “Healthiest Way of Eating.”

why navy beans should be part of your healthiest way of eating

As with other varieties of legumes, combining Navy Beans with a whole grain, such as brown rice, provides a virtually fat-free, high-quality protein. Their good supply of dietary fiber promotes a healthy heart and helps maintain healthy blood sugar levels. (Navy Beans’ health benefits and nutritional profile are similiar to black beans. For more information, see page 615.)

varieties of navy beans

Dried and canned Navy Beans are available (same as black beans, see page 610).

the peak season available year-round.

biochemical considerations

Same as black beans (see page 611).

the best way to select navy beans

Same as black beans (see page 611).

the best way to store navy beans

Same as black beans (see page 611).

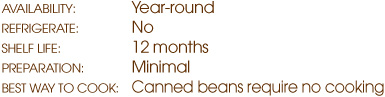

the best way to prepare navy beans

Same as black beans (see page 612).

the healthiest way of cooking navy beans

For details about cooking, see black bean recipe (page 614). Navy Beans take 1 to 1½ hours to cook.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Way to Prepare Navy Beans

The issue of acid and alkaline foods is a confusing one, because there are several different ways of using these words with respect to food.

Acidic and alkaline foods

In food chemistry textbooks that take a Western science approach to foods, every food has a value that is called its “pH value.” pH is a special scale created to measure how acidic or alkaline a fluid or substance is. It ranges from 0.0 (most acidic) to 14.0 (most alkaline) with 7.0 being neutral. One way of thinking about it is that as you get closer to 7.0 from either end, the food becomes less acidic (6.0 vs 5.0, for example) or less alkaline (8.0 vs 9.0, for example).

Limes, for example, have a very low pH of 2.0 and are highly acidic according to the pH scale. Lemons are slightly less acidic at a pH of 2.2. Egg whites are not acidic at all and have a pH of 8.0. Meats are also non-acidic, with a pH of about 7.0.

Many vegetables lie somewhere in the middle of the pH range. For example: asparagus, 5.6; sweet potatoes, 5.4; cucumbers, 5.1; carrots, 5.0; green peas, 6.2; and corn, 6.3. Tomatoes have a lower pH than most other vegetables with their pH ranging from 4.0 to 4.6. Tomatoes also have a higher pH (are less acidic) than some fruits such as pears (3.9), peaches (3.5), strawberries (3.4) and plums (2.9).

Acid-forming and acid-ash, alkaline-ash foods

Another way to talk about food acidity is not to measure the acidity of the food itself but the body’s acidity once the food has been eaten. In other words, from this second perspective, a food is not labeled as “acidic,” but instead as “acid-forming.”

Similar to this “acid-forming” concept is the “acid-ash, alkaline-ash” concept, in which a food is not chemically broken down in the body, but instead burned, leaving an ash residue, which is then measured for its mineral content. Acid-ash foods are foods that leave high concentrations of chloride, phosphorus or sulfur in their ash. These foods are called “acid-ash” because chloride, phosphorus and sulfur are minerals that are used to make acids in the body (namely, hydrochloric acid, phosphoric acid and sulfuric acid). Alkaline-ash foods are foods that leave high concentrations of magnesium calcium and potassium in their ash. These foods are called “alkaline-ash” because these minerals are used to form alkaline compounds (called bases) in the body (including magnesium hydroxide, calcium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide).

The acid-ash model of measuring food acidity is not, of course, what happens inside a living person. We don’t burn our food, and ash is not all that’s left after we eat. In fact, the whole concept of acid-forming foods is a much more complicated idea than the pH idea, since “acid-forming” is a process that happens inside a living body.

How well a food is digested, for example, can influence the degree to which it is acid-forming or not. Many foods have preformed acids in their composition that would normally be altered during digestion. However, in a person with problematic digestion, these acids might not get transformed, and their acid-forming properties would be increased.

Research on the Acid-Forming and Acid-Ash, Alkaline-Ash Foods Principles

Although there are many popular diets that revolve around the principle of acid-forming foods, there are virtually no research studies that have focused on this issue. A survey about dietary patterns and lifestyles carried out in China in the early 1990s has shown that higher intake of animal foods and animal-derived proteins results in increased loss of calcium and acids in the urine, while increased intake of plant foods and plant proteins results in lower calcium and acid loss. Presumably, the loss of acids in the urine reflected increased formation of acids in the body that needed to be excreted, and decreased urine acids reflected less formation of acids in the body. Vegetables were one of the major groups of plant foods focused on in the study; vegetables have been described in many alternative dietary approaches as being non-acid-forming.

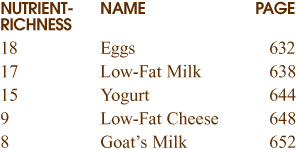

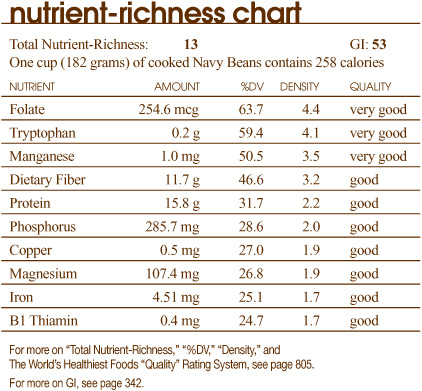

dairy & eggs

The numbers beside each food indicate their Total Nutrient-Richness. (For more details, see page 805.)

dairy & eggs

Dairy products are among the most widely consumed foods in the United States—and for good reason. Just consider the array of delicious dairy foods that we enjoy—a cold glass of milk, a rich piece of cheese, creamy yogurt, cottage cheese or ice cream topped with fresh fruit—and it’s easy to see why they are an integral part of our food culture. Not only do these foods taste great and add a flavorful flair to many meals and snacks, but they are also a concentrated source of many important nutrients.

Think about the all-American breakfast, and eggs will probably come to mind. Scrambled, poached, boiled, baked or made into an omelet… the ways to prepare and enjoy eggs are many and varied. And because eggs provide a source of complete, inexpensive protein and also supply many other important nutrients, they provide your body with energy and vitality.

While I feel that most people can enjoy dairy products and eggs as an important component of the “Healthiest Way of Eating,” I believe that these foods should be consumed in moderation. The reason for this is that many people have sensitivities to dairy and eggs and in addition to concentrating many nutrients, these foods can also be high in saturated fat and cholesterol.

Definition: Dairy and Eggs

Dairy products come from the milk of cows and other animals. While the dairy products used in the United States are primarily made from cow’s milk, products from goat’s and sheep’s milk are growing in popularity in the United States and are widely consumed in other parts of the world.

Although many different types of birds lay eggs, that can be consumed as food, in this book I am referring to chicken eggs.

Dairy and Eggs are Rich in Health-Promoting Nutrients

Dairy products and eggs contain a wealth of vital nutrients that can help support health. Not only are they protein-rich foods, but they also deliver concentrated amounts of vitamins such as D, B2, B12, K and biotin as well as minerals like calcium, selenium, iodine and phosphorus.

Because one of the concerns surrounding dairy products is their high fat content, I recommend using low-fat milk, cheese and yogurt; enjoyed in moderation they will help you stay energized and healthy. While dairy products are often high in fat, egg whites contain no fat and are a rich source of protein. The yolk is the fat-containing portion of the egg with about 5–6 grams of total fat; approximately one-third of this fat is saturated fat. But when eating eggs in moderation, don’t avoid the yolk—egg yolk is a very rich source of choline, a key component of healthy cell membranes, nerves and brain cells. Egg yolks also provide lutein, a carotenoid that protects against macular degeneration and cataracts.

Why Dairy and Eggs Should be Heated to Be Safe to Eat

Eggs have a fairly high concentration of biotin, but before they are heated, the biotin is bound to a protein called avidin that reduces its absorption by the body. Heating breaks the bond and actually increases the bioavailability of biotin.

Heating or cooking eggs for a sufficient length of time and at a sufficiently high temperature also kills bacteria such as Salmonella. Therefore, soft-cooked, sunny-side up or raw eggs carry greater risk of contracting salmonellosis than poached, scrambled or hard-boiled eggs. It’s been estimated that Salmonella bacteria may be present in 1 out of every 30,000 eggs produced in the United States, and since almost 100 billion eggs are produced in the United States each year, that means there are over 3,000 potentially contaminated eggs. So remember to cook your eggs well.

Unheated, raw milk may also be contaminated with bacteria such as Salmonella, E. coli, Campylobacter, Listeria or Yersinia. Although some people prefer to drink raw milk because they believe it is more natural or nutrient-rich in terms of enzymes and other nutrients, pasteurization kills the potentially harmful microbes making it safer to drink. If you wish to consume raw dairy foods, you may want to consider raw milk cheese as it falls into a somewhat different category than raw milk, since cheese has a naturally longer shelf life. Some producers of raw milk cheese still expose their products to a short period of heat treatment, which comes very close to, but falls short of, the pasteurization threshold. I would choose raw milk cheese that has been aged for at least 60 days, because this destroys the bacteria.

Calcium—Are Dairy Products the Best Source of Calcium?

Since dairy products are a concentrated source of calcium, people concerned about bone health and preventing osteoporosis tend to include lots of milk and milk products in their diets with the hope of meeting their calcium requirements. While dairy products have been widely emphasized as the primary source of calcium, it is important to remember that they are by no means the only foods that provide significant amounts of this important mineral. Virtually all dark green leafy vegetables, including spinach, Swiss chard, mustard greens and collard greens contain calcium. Practically all nuts and seeds—especially sesame seeds—contain calcium as do most beans, including navy, pinto, kidney and black beans. And tofu that has been prepared with calcium chloride is also an excellent source of this nutrient. Therefore, a diet that preserves bone health need not be solely dependent on dairy products for calcium but should also emphasize calcium-rich plant foods.

Dairy and Eggs May Not Be for Everyone

While dairy products are an important component of a health-promoting diet for most people, many individuals have difficulty tolerating dairy products. For example, people who are lactose intolerant do not have sufficient amounts of the enzyme lactase, which is necessary to break down the milk sugar, lactose, found in dairy products, and therefore have problems digesting these foods. Yet even if a person produces sufficient lactase, dairy products may still be a challenge since dairy products, as well as eggs, are amongst the foods most associated with allergic and delayed hypersensitivity reactions. (For more on Food Allergies, see page 719.)

Many people who are sensitive to cow’s milk can tolerate goat’s milk, a food that I have included among the World’s Healthiest Foods. That is because while goat’s milk contains casein, researchers have found that it generally only has trace amounts of a specific casein, alpha-s1-casein, which is thought to be one of the main proteins in cow’s milk responsible for eliciting sensitivity reactions.

The Importance of Organically Produced Dairy and Eggs

As with all of the World’s Healthiest Foods, I recommend purchasing organic varieties of the World’s Healthiest Dairy Products and Eggs whenever possible. This is because organic dairy products and eggs are not only better for our health, but they are also produced in a way that provides a less stressful and more humane environment for the animals from which they come. Here is some background information on what constitutes “organic” dairy products and eggs:

The term organic is related to both the way in which the food was handled in production and the way in which the animals that produced the milk or eggs were raised. According to the organic regulations, organic cows, goats and chickens can only be fed organically produced foods and never receive mammal or poultry slaughter by-products for feed (an important consideration when we think of potential problems such as mad cow disease and hoof-and-mouth disease). They cannot be given growth-promoting hormones, administered drugs in the absence of illness or be given supplements in amounts above those for adequate nutrition. Plus, they must be treated in a humane manner. Their health and welfare must be maintained and promoted; they must be given sufficient nutritional feed rations, appropriate housing, pasture and sanitation conditions, and freedom of movement. Additionally, the stress placed on them must be minimized.

How to Use the Individual Dairy and Eggs Chapters

Each chapter is dedicated to one of the World’s Healthiest Dairy Products or Eggs and contains everything you need to know to enjoy and maximize their flavor and nutritional benefits. Each chapter is organized into two parts:

1. DAIRY AND EGGS FACTS describes eggs or each dairy product and its different varieties and peak season. It also addresses biochemical considerations of each food by describing unique compounds each contains that may be potentially problematic to individuals with specific health problems. Detailed information about the health benefits of the dairy product and eggs can be found at the end of the chapter devoted to each individual food, as can a complete nutritional profile.

2. THE 3 STEPS TO THE BEST TASTING AND MOST NUTRITIOUS DAIRY PRODUCTS AND THE 4 STEPS TO THE BEST TASTING AND MOST NUTRITIOUS EGGS includes information about how to best select, store and prepare each one of these World’s Healthiest Foods.

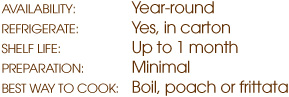

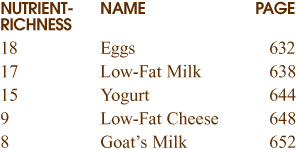

eggs

highlights

Although Eggs have long been referred to as the “perfect food,” cholesterol-conscious Americans have recently been shying away from them. An increasing number of studies, however, are now supporting high saturated-fat intake as more closely related to elevated cholesterol levels than the dietary intake of cholesterol-rich foods such as Eggs. Nutritious, versatile and easy to prepare, they are a great addition to your “Healthiest Way of Eating.”

why eggs should be part of your healthiest way of eating

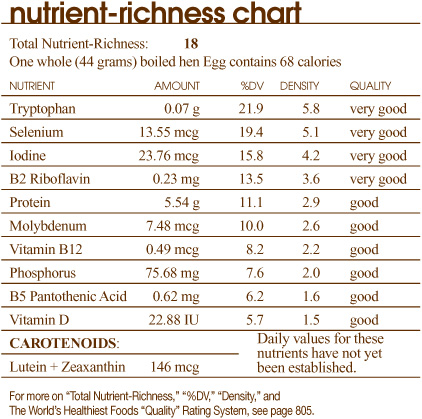

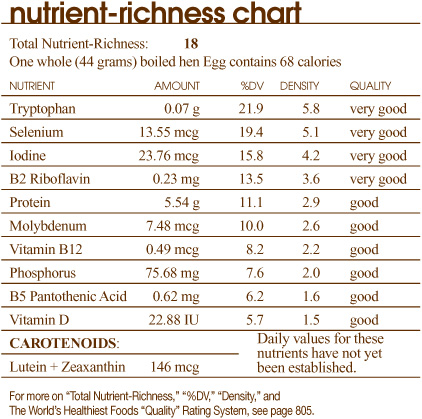

Eggs are one of the highest quality sources of protein. Egg whites contain adequate amounts of all essential amino acids and are used as the standard against which all protein is measured. Eggs are not only a good source of inexpensive protein, they are also a very good source of iodine, important for healthy thyroid function. Egg yolks contain the carotenoid phytonutrient lutein, which has been found to be important for eye health. They are also one of the few excellent sources of the B vitamin, choline, a key nutrient for brain function and health. Eggs are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are high in nutrients, but also because they are low in calories: one Egg contains only 68 calories. (For more on the Health Benefits of Eggs and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 636.)

varieties of eggs

Some of the types of hen Eggs available in the market include:

ORGANIC

Produced following the organic food guidelines. From chickens not treated with any antibiotics or hormones.

OMEGA-3 ENRICHED EGGS

Eggs produced by chickens that have been fed a diet containing higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids. Although the Eggs have enhanced levels of omega-3s, they are not intended to be the sole source of this essential fatty acid.

BROWN EGGS

Produced by a special breed of chickens. The color of these Eggs does not necessarily confer a significant nutritional benefit.

Some markets also carry duck, goose and quail Eggs, all of which have yet to gain mainstream popularity.

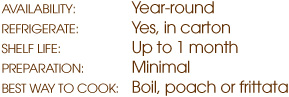

the peak season

Eggs are available throughout the year.

biochemical considerations

Eggs are one of the foods most often associated with allergic reactions. (For more on Food Allergies, see page 719.)

Handling of Eggs

Health safety concerns about Eggs center on salmonellosis (Salmonella-caused food poisoning). Salmonella bacteria from the chicken’s intestines may be found even in clean uncracked Eggs. Formerly, these bacteria were found only in Eggs with cracked shells. Safe food handling techniques, like washing the Eggs before cracking them, may not protect you from infection. To kill the Salmonella, eggs must reach an internal temperature of 160°F (71°C), effectively pasteurizing them. Soft-cooked or sunny-side-up Eggs should be cooked until the yolk is firm. There is no risk of salmonellosis when Eggs are hard-boiled, scrambled or poached (make sure to refrigerate hard-boiled Eggs at most 2 hours after cooking). Raw Eggs, however, do carry risk of Salmonella-caused food poisoning.

Dishes and utensils used when preparing Eggs (as well as meat and poultry) should be washed in warm water separately from other kitchenware, and washing your hands with warm, soapy water is essential after handling Eggs. Any surfaces that might have potentially come into contact with raw Eggs should be washed and can be sanitized with a solution of one teaspoon chlorine bleach mixed with one quart water.

Cholesterol in Eggs

Eggs yolks are high in cholesterol, which may be of concern to some individuals. (Egg whites are cholesterolfree.) One Egg contains 187 mg of cholesterol.

4 steps for the best tasting and most nutritious eggs

Turning Eggs into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select eggs

Eggs are often classified according to the USDA grading system and bear a label of AA, A or B; however, not all Eggs are labeled or graded because it is not legally mandatory. The grading system is an indicator of quality parameters including freshness. I always try to purchase the freshest and best quality Eggs, which means selecting AA Eggs. Farm fresh Eggs from a local purveyor are often not labeled. If this is the case, familiarize yourself with the reputation of the person selling the Eggs and make sure the Eggs have been kept refrigerated. Eggs are also labeled according to their size—extra large, large, medium and small.

Inspect Eggs for breaks or cracks before purchasing them and remain aware of their fragility while packing them into a shopping bag for the trip home. As with all foods, I recommend selecting organically produced Eggs whenever possi-

2. the best way to store eggs

Do not wash Eggs before storing as this can remove the protective coating on the shells, making them more susceptible to bacterial contamination. Be sure that they are stored with their pointed end facing downward as this will help to prevent the air chamber and the yolk from being displaced. Although many refrigerators feature an Egg container on the door, this is not the best place to store Eggs since this exposes them to too much warm air each time the refrigerator door is opened and closed. Store your Eggs in the back of the refrigerator where they will keep for up to one month. You can check the container for the date they were packed.

It is best to leave Eggs in their original carton or place them in a covered container so that they will not absorb odors or lose any moisture.

3. the best way to prepare eggs

Make sure your Eggs are fresh. Yolks of fresh Eggs will float on top of the Egg white. Cracking each Egg individually into a bowl before adding it to your recipe will allow you to determine whether it is old or spoiled. It helps if you bring refrigerated Eggs to room temperature for certain cooking methods. For instance, when you boil Eggs, the shells are not as likely to crack if they start at room temperature. Also, Egg whites will not peak well if they are cold. Be sure to throw away cracked Eggs as they may be contaminated.

4. the healthiest way of cooking eggs

When cooking Eggs, it is important to watch that they are cooked long enough that the Egg whites are no longer translucent. The best ways to cook Eggs is by boiling, poaching or making a frittata with broth instead of oil. These methods ensure your Eggs will be well cooked.

METHODS NOT RECOMMENDED FOR COOKING EGGS

I don’t recommend cooking Eggs in oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and potentially create harmful free radicals. (For more on Why it is Important to Cook Without Heated Oils, see page 52.)

Here are questions I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Eggs:

Q Can Eggs be eaten raw? Will they still be nutritious?

A As far as I see it, the main concern about raw versus cooked Eggs is not so much issues of nutrients but of safety. Eating raw Eggs brings with it the risk of poisoning from Salmonella, a bacteria that is destroyed by thoroughly cooking Eggs. To kill the Salmonella, Eggs must reach an internal temperature of 160°F (71°C) or be cooked at 140°F (60°C) for at least three minutes, effectively pasteurizing them. This translates to a 7-minute boiled Egg, a 5-minute poached Egg or a 3-minute per side fried Egg. Now, this is not to say that eating raw Eggs is a definite way to ingest Salmonella, but it does carry this risk. Restaurants that serve raw Eggs in certain recipes (such as Caesar salads) normally use Eggs that have been pasteurized, a process that helps to kill bacteria.

The main nutritional concern regarding consuming raw Egg whites is that Egg whites contain a compound called avidin that binds the B-vitamin biotin which can lead to a deficiency of this nutrient in certain people. Cooking the Egg white deactivates the avidin.

Q Does the cholesterol in Egg come from the yolk only or is it present in the Egg whites as well?

All of the cholesterol in the Egg comes from the yolk, so eating only the whites will not contribute any cholesterol to your diet.

Q Do the whites of Eggs absorb the chemicals fed to chickens?

A Both the whites and yolks of Eggs absorb chemicals consumed by chickens. Since the whites are mostly composed of protein, they tend to absorb more of the heavy metals (like mercury) and less of the pesticides (which are mostly fat soluble). The yolks tend to absorb more of the pesticides and other fat-soluble contaminants since they are composed primarily of fat. However, there has been research showing various types of contaminants in both whites and yolks. All of these potential problems are avoided, of course, by choosing certified organic Eggs produced by organically raised chickens.

STEP-BY-STEP RECIPE

The Healthiest Ways of Cooking Eggs