In addition to being a good source of vitamin C, Pears also contain a spectrum of flavonoids. Vitamin C and flavonoids have a synergistic relationship, each helping to improve the antioxidant potential of the other. Vitamin C helps to protect cells from oxygen-related damage due to free-radicals; for example, vitamin C protects LDL (“bad”) cholesterol from oxidation, which is one of the ways in which this vitamin protects against heart disease. The flavonoids contained in Pears—including catechins and quercetin—are antioxidants that have also been linked with cardiovascular disease prevention.

Additionally, Pears are packed with phytosterols. These phytonutrients have been shown to be able to inhibit cholesterol absorption and therefore potentially help to lower cholesterol levels. Yet, Pears’ benefits in relation to cholesterol don’t stop there since they are a good source of dietary fiber, which numerous studies have shown helps reduce cholesterol.

Although their hypoallergenicity is not well-documented in scientific research, Pears are often recommended by healthcare practitioners as a fruit less likely to produce an allergic response than other fruits. Particularly in the introduction of first fruits to infants, Pear is often recommended as a safe way to start.

In addition to the antioxidant vitamin C and flavonoids that Pears contain, they are also a good source of copper. An important trace mineral, copper helps protect the body from free-radical damage via its role as a necessary component of superoxide dismutase (SOD), a copper-dependent enzyme that eliminates superoxide radicals. Superoxide radicals are a type of free-radical generated during normal metabolism as well as when white blood cells attack invading bacteria and viruses. If not eliminated quickly, superoxide radicals damage cell membranes.

Pear’s fiber does a lot more than just help prevent constipation and ensure regularity. Fiber also binds to cancer-causing chemicals in the colon, preventing them from damaging colon cells. This may be one reason why diets high in fiber-rich foods, such as Pears, are associated with a reduced risk of colon cancer. Additionally, the fact that low dietary intake of copper seems to also be associated with risk factors for colon cancer serves as yet another reason in support of why this delicious fruit may be very beneficial for digestive health.

The rainbow hues of fruits and vegetables don’t just make these healthy foods attractive to our eyes—they are actually part of the reason that these foods are so healthy in the first place.

That’s because these foods contain nutrients, called phytonutrients, which are unique to plants (phyto = plant) and endow them with their beautiful pigments. Phytonutrients actually provide a lot of benefit to the plant as well as to those whose diets are rich in these plant foods. For example, many of them have powerful antioxidant activity, able to quench free-radicals that could otherwise do harm to our cells and genetic material. Darker colored fruits and vegetables reflect higher concentrations of nutrients and more flavor than those that are pale in color.

Let’s travel through the spectrum of colors to further explore how eating color-rich foods can also mean eating nutrient-rich foods.

Red-colored foods such as tomatoes, watermelon and grapefruits feature a phytonutrient known as lycopene. This member of the carotenoid phytonutrient family has powerful antioxidant activity, more effective actually than its well-known carotenoid cousin, betacarotene. Lycopene is especially effective at thwarting a free-radical called singlet oxygen and as such is important for protecting the lipid-containing parts of cell membranes from the damage usually caused by that free-radical.

Yellow- and orange-colored foods such as papaya, apricots, carrots and sweet potatoes are rich in the carotenoids, alpha-carotene, betacarotene and beta-cryptoxanthin, which lend them their sunshine-colored hues. Not only do these carotenoids fight free-radicals but they are also converted in the body to retinol, the active form of vitamin A.

Green-colored foods such as spinach, kale, asparagus and other leafy green vegetables are rich in phytonutrients such as chlorophyll and lutein. Chlorophyll is structurally similar to the hemoglobin molecule in our bodies that transports oxygen, although instead of containing iron at its center it contains magnesium. Lutein is a carotenoid antioxidant that has been found to be especially beneficial to vision health since it is concentrated in the eyes.

Blue- and purple-colored foods such as grapes, blueberries, eggplant, black beans and purple potatoes get their royal colors from phytonutrients such as anthocyanins. These flavonoid phytonutrients have many important functions in the body; they improve the integrity of support structures in the veins and the entire vascular system, enhance the effects of vitamin C, improve capillary integrity and stabilize the collagen matrix (the ground substance of all body tissues).

Yet, it’s not just different foods that feature different colors. There are certain fruits and vegetables that can be found in an array of colors and therefore offer you an array of nutritional benefits. Green, red or yellow apples? Yellow, white or blue corn? Purple, green or white asparagus? Depending upon which one you choose you will receive different nutritional benefits.

For example, different colored onions contain different levels of nutrients. Of the storage onions, white ones have the least amount overall. Not surprisingly, red and yellow onions contain more quercetin, a flavonoid phytonutrient pigment, than white onions. Red onions also contain more anthocyanin flavonoid phytonutrients than white or yellow ones, which is reflected in their red coloring.

When given the choice I like to eat deeply colored foods. If choosing between two heads of lettuce, I choose the one that has a deeper, richer green color. When choosing between red apples, I usually opt for the one with the more brilliant scarlet color. Not only do deeper, darker colors enrich my sensory experience of a food, but I also feel that they enrich my health as well.

That’s because their deeper colors are often a reflection of their having a greater concentration of phytonutrient pigments. For example, pink grapefruit contains about 27 times more betacarotene than white grapefruit while red bell peppers contain about 18 times more betacarotene than yellow ones and 6 times more than green ones! So, remember that it’s not just color in general that’s important but the intensity of color that can also make a big difference when it comes to the nutritional benefits that you’ll receive from fruits and vegetables.

To benefit most from these wonderful phytonutrients that nature has provided for us, I think it is important to eat a diet that features a range of colors. Create a salad with vegetables from all parts of the rainbow. Make your dinner plate a spectrum of many deeply colored foods. This way you can help ensure that you are receiving the unique benefits that different phytonutrients have to offer.

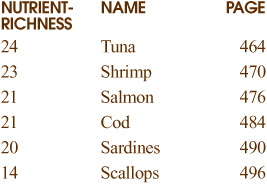

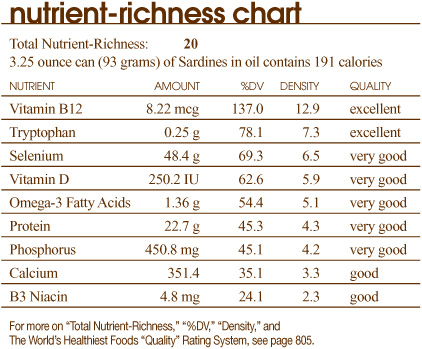

With the increased wave of interest in foods that provide great nutrition, it is not surprising that the demand for fish and shellfish has doubled within the last ten years. Nutrition experts encourage eating more fish and shellfish because they are excellent sources of protein and rich in omega-3 fatty acids, and their consumption has been linked to a reduced risk of many diseases. Many research studies have shown that cultures in which seafood plays a prominent role in the diet not only have more abundant health but live longer. Not surprisingly, seafood are sometimes referred to as the “perfect food.”

Yet, it’s not just their health benefits that can make fish and shellfish such wonderful additions to your “Healthiest Way of Eating.” They can also be delicious and offer a wide range of tastes and textures. Some are light and flaky, while others are sweet and meaty. Some lend just the right depth to make a summer salad a filling meal, while others are a perfect addition to a hearty winter stew. There are fish and shellfish to meet everyone’s individual preferences, and since a little goes a long way, they are certain to not only please your taste buds but your wallet as well.

Recently, attention has been drawn to some concerns about consuming seafood. Because of environmental contamination, some fish are laden with mercury and may pose a problem for certain people. Additionally, practices of indiscriminate fishing are depleting some fish and shellfish species, while processes involved in fish farming are endangering the environment. The bottom line is that when you purchase fish and shellfish, you need to be an educated consumer in order to protect both your health and the health of the environment. Because I believe this is so important, this chapter features a Fish & Shellfish Guide that can help you easily decipher which fish and shellfish are the best options.

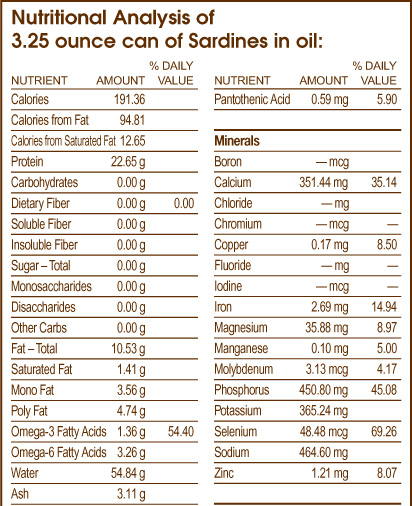

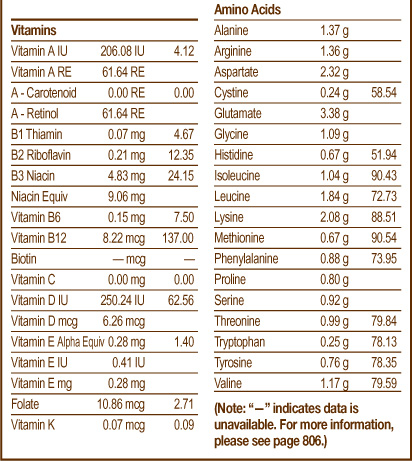

When I refer to fish, I am referring to the flesh of aquatic vertebrate animals (usually having scales and fins) that are consumed as food. Examples of fish include salmon, tuna, cod, sardines, tilapia and striped bass. Shellfish refers to the flesh of aquatic invertebrate animals that have a hard shell. Examples of shellfish include shrimp and scallops.

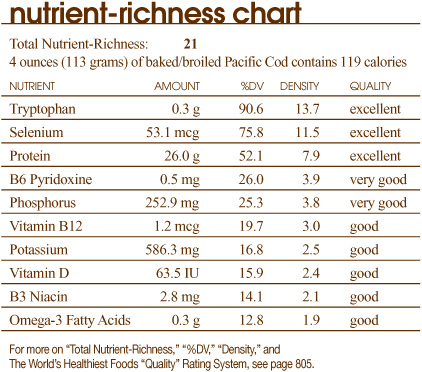

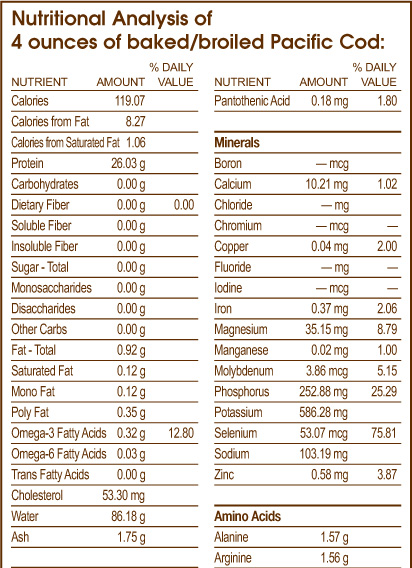

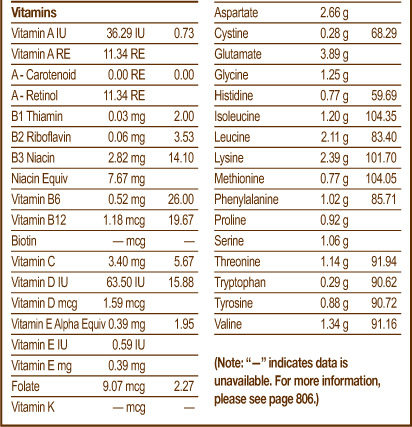

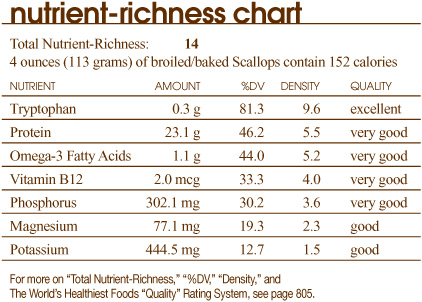

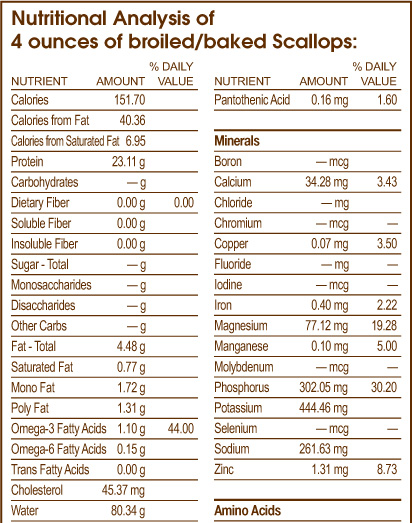

Fish and shellfish can play a very important role in a health-promoting diet. So many important nutrients—protein, selenium, magnesium, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, niacin and omega-3 fatty acids to name just a few—are concentrated in these foods that it is no wonder they are referred to as treasures of the sea. Just 4 ounces (cooked) of most fish and shellfish can supply 50% of your daily value for protein, vitamin B12 and selenium for relatively very few calories. Now that’s what I call nutrient-rich!

The healthfulness of fish and shellfish is a reflection of the compounds which they concentrate, but also the compounds they do not. In addition to the low caloric content of many fish, most also have less saturated fat and cholesterol than their land animal counterparts (an exception would be shrimp, which are noted sources of cholesterol).

Additionally, for those who are focused on attaining or maintaining their ideal body weight, these foods can be instrumental in helping them achieve their goal. For example, a 6-ounce serving of shrimp provides almost 36 grams of protein for a mere 168 calories. Compare this to a 6-ounce serving of beef that contains 48 grams of protein at a caloric cost of 360 calories or a 6-ounce serving of chicken containing 51 grams of protein for 335 calories and you can see how seafood will fill you up without filling out your waistline. Featuring fish and shellfish as the centerpiece of your meals will keep your taste buds satisfied and your appetite satiated, while providing so many of the nutrients vital to optimal physiological functioning. And since all of the benefits of these foods cost you very little in terms of calories, they can also help you attain your ideal weight goals.

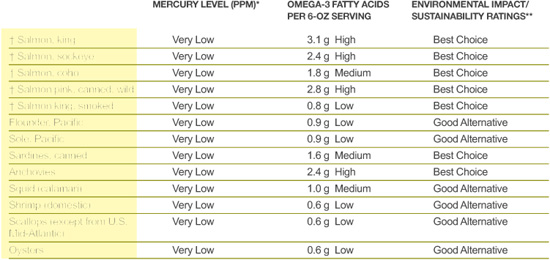

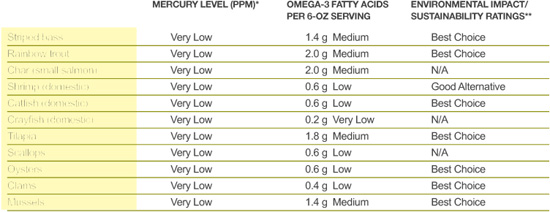

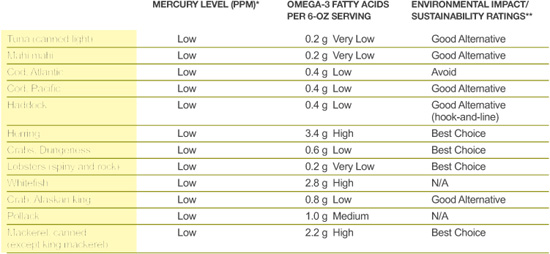

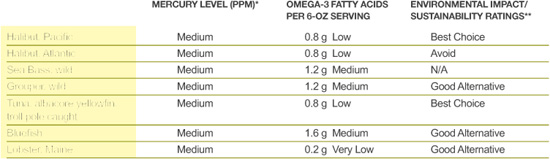

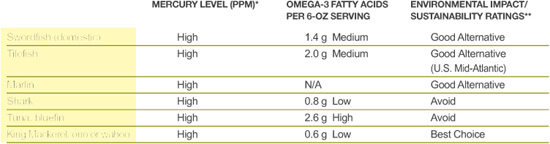

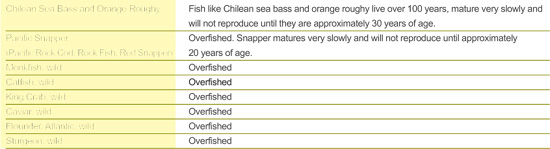

Since there are thousands of different types of fish and shellfish, making a seafood selection is sometimes difficult and confusing. I have developed a Fish & Shellfish Guide (The Guide) to help you make informed decisions about which fish and shellfish are best for you and decide which ones to purchase.

There are three things to consider when purchasing fish and shellfish.

1. Which fish have the lowest mercury content?

2. Which fish and shellfish provide the highest concentration of those hard-to-find omega-3 fatty acids?

3. What is the environmental impact of different fishing and farming methods used to catch and raise fish and shellfish? What is their effect on the sustainability of wild stocks of fish and shellfish?

You can select fish and shellfish that are safe to eat by simply following The Guide included in this chapter. Some fish and shellfish contain higher mercury levels than others, but you will be surprised that there are many types of fish and shellfish with low levels of mercury.

Mercury is a heavy metal that has contaminated many of our seas and oceans. Mercury toxicity can cause birth defects, damage to the nervous system, premature aging, vision loss and the onset of certain diseases. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has urged individuals, notably children and women who are pregnant, lactating or of childbearing age, to avoid certain fish because of their high mercury concentrations. These fish include swordfish, tuna, king mackerel (ono or wahoo), shark and tilefish. Most fish that grow slowly and become very large tend to have higher mercury levels. The Guide helps you to select the fish and shellfish lowest in mercury levels. (For more on Mercury in Fish, see page 463.)

The U.S. FDA standard considers fish safe if it contains less than 1 ppm of methyl mercury. Canada’s recommendation is that 0.5 ppm is considered safe.

Most people in the U.S. are deficient in omega-3 fatty acids. One of the qualities for which many fish and shellfish have gained such great acclaim is that many of their fats are “good fats,” which includes omega-3 fatty acids in the form of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Fish and shellfish can directly provide your body with these important essential fatty acids.

Many species of fish and shellfish—including salmon, sardines, trout, halibut and scallops—contain rich concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids while others—such as lobsters, crabs, crayfish, oysters, squid and mahi mahi—are low in omega-3 fatty acids.

Omega-3 fatty acids have many health benefits, and cultures whose diets feature these important nutrients have been found to have reduced incidence of many different diseases as well as increased longevity. The Guide is designed to help you select the fish that will provide you with all of the beneficial omega-3 fatty acids you need. It includes ratings of high, medium, low and very low concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids, which are defined as follows: high (2.0+ g), medium (1.0-2.0 g), low (0.3-1.0 g) and very low (below 0.2). These amounts are based on a 6-ounce serving. (For more on Omega-3 Fatty Acids, see page 770.)

When deciding which fish or shellfish to purchase, it is very important to consider the environmental impact that these decisions may produce if you are concerned with the health and safety of our oceans and waterways. You can help protect fish and shellfish and the sustainability of the oceans, lakes and rivers by making environmentally aware choices.

Due to overfishing and depleted stocks of fish and shellfish, the 1996 Sustainable Fisheries Act was created to address the necessity of better management of both fish and shellfish. Size of the fish caught, overall catch size, seasonal fishing and how fish are harvested are now being more commonly considered in fisheries’ management practices. If you are concerned about conservation, there are many types of fish and shellfish that you can enjoy that are considered sustainable and whose consumption does not greatly impact the environment. The Guide will provide you with information about how you can be an aqua-environmentally responsible citizen.

Fortunately, a growing number of resources, such as Seafood Watch provided by the non-profit Monterey Bay Aquarium (http://www.mbayaq.org/cr/seafoodwatch.asp), provide online information about how to support the fisheries and fish farms that maintain practices that are healthier for both the fish and the environment. The Monterey Bay Aquarium provides you with three lists (Best Choices, Good Alternatives and Avoid) to help you select fish and shellfish whose consumption will least impact the environment. I have used their sustainability ratings in The Guide.

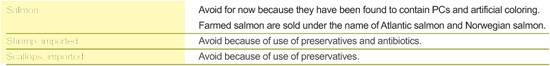

At the time of this writing, wild-caught Alaskan salmon and Pacific cod are on the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s list of Best Choices, while monkfish, Atlantic cod, Chilean sea bass and orange roughy are on the list of fish and shellfish to Avoid. Fish like Chilean sea bass and orange roughy mature very slowly, and heavy fishing pressure on slow growing fish results in depletion of their population. However, fish like mahi mahi that grow and reproduce quickly are considered to be less affected by fishing pressures and therefore more ecologically sound. They can grow up to 20 pounds in one year, reproduce at a young age and live only four to five years, so their consumption does not generally pose a problem for sustainability. Salmon also have very a short lifespan ranging from two to five years, depending on the species, after which they return to the rivers where they were hatched to spawn and die.

Most tilapia and striped bass now found in markets are farmraised, using methods that have little environmental impact, and are therefore considered environmentally sustainable. Information regarding sustainability can change; updated information will be posted on the World’s Healthiest Foods website, www.whfoods.org.

The Fish & Shellfish Guide is divided into separate categories: Wild Fish & Shellfish Safe to Eat, Farmraised Fish & Shellfish Safe to Eat, Fish & Shellfish OK to Eat One Meal Per Week and Fish & Shellfish OK to Eat One Meal Per Month. In The Guide you will also find information on Fish & Shellfish to Avoid.

For years we have been told to eat fish a couple of times a week for optimal health, however, a recent research study shows why it is important to eat fish with one meal every day. Researchers in Japan found that daily consumption of omega-3-rich fish results in a significantly greater reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease compared to eating fish just a couple of times a week.

When participants who consumed fish eight times per week were compared with those whose intake was just once per week, it was found that those eating the most fish had a 37% lower risk of developing coronary heart disease and a 56% percent lower risk of heart attack. None of the participants had cardiovascular disease or cancer when the study began.

When the effect of omega-3 fatty acid intake on cardiovascular risk was analyzed, coronary heart disease risk was lowered by 42% among those whose intake was the highest, at 2.1 grams per day or more, compared to those whose intake was the lowest at 300 milligrams (0.3 grams) per day. Those whose intake of Omega-3s was in the top tier received a 65% reduction in the risk of heart attack compared to those whose omega-3 intake was lowest.

The authors theorize that daily fish consumption is highly protective largely due to the resulting daily supply of omega-3 fatty acids, which not only reduce platelet aggregation, but also decrease the production of proinflammatory leukotrienes. Lowering leukotrienes reduces damage to the endothelium (the lining of the blood vessels), a key factor in the development of atherosclerosis.

“Our results suggest that a high fish intake may add a further beneficial effect for the prevention of coronary heart disease among middle-aged persons,” note the study’s authors.

Iso H, Kobayashi M, Ishihara J, etal; JPHC Study Group. Intake of fish and n3 fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese: the Japan Public Health Center-Based (JPHC) Study Cohort I. Circulation. 2006 Jan 17;113(2):195-202. Epub 2006 Jan 9.

† Best Choice = Alaskan wild-caught salmon, Good Alternative = California, Oregon and Washington wild-caught salmon, Avoid = Atlantic salmon

If you, your family or friends have caught local freshwater fish and want to know whether they are safe to eat, call the Environmental Protection Agency at 1-888-SEAFOOD.

Many fish and seafood are now farmed. If they are farmed in clean waters using environmentally sound production practices, they do not provide much of an environmental problem. Shellfish such as scallops, clams, mussels and oysters are filter feeders (they filter the surrounding water for the food they eat) and therefore can easily accumulate pollutants if they are farmed in unclean waters. Striped bass, rainbow trout, tilapia and white sturgeon are grown in inland farms and have not been found to present an environmental problem.

Atlantic salmon and shrimp are produced in coastal operations, which have often been found to be environmentally unfriendly. While shrimp farming is well regulated in the United States, operations in foreign countries are not.

Fresh fish is best. Not only does fresh fish supply you with important omega-3 fatty acids but like all whole foods they provide an entire range of protein, vitamins and minerals that work together to promote optimal health. If you decide to purchase fish oil capsules to supplement your diet with omega-3 fatty acids, you’ll want to select a product from a very high-quality manufacturer to make sure that the omega-3 fat content is what it’s supposed to be and that these fragile oils are not rancid.

Some fish oil products go through a refining process that removes contaminants that may be found in the fish itself. To be sure that your supplements are free of such contaminants, such as PCBs and dioxins, purchase a brand that has undergone “molecular distillation,” which removes contaminants; this will be stated on the product label.

Mercury in fish oil capsules does not seem to be a general problem. According to www.consumerlab.com’s 2004 testing of 20 fish oil products currently available in the marketplace, none of the products contained detectable mercury levels. Most mercury has been found to be in the flesh rather than the oil.

The American Heart Association recommends that healthy individuals eat at least 2 servings per week of fish or shellfish. But to get an optimal amount of omega-3 fatty acids, I recommend 3–4 servings per week of fish or shellfish that are low in mercury content, rich in omega-3 fats and considered environmentally sustainable.

This goal should not be too difficult because you can enjoy many varieties of fish that fit these criteria. Salmon, shrimp, cod and scallops are just a few to choose from. And with the numerous recipes that I have included for each of the World’s Healthiest Fish and Shellfish, you’ll have a cornucopia of different preparation options. Because these recipes are so quick and easy to prepare, they will not only help satisfy the needs of your taste buds but of your busy schedule as well.

The American Heart Association’s recommended serving size for seafood is 6 ounces raw or 4 ounces cooked.

Each fish and shellfish chapter is dedicated to one of the World’s Healthiest Fish and Shellfish and contains everything you need to know to enjoy and maximize its flavor and nutritional benefits. Each chapter is organized into two parts:

1. FISH AND SHELLFISH FACTS describes each fish and shellfish, their different varieties and peak season. It also addresses biochemical considerations of each fish and shellfish by describing any unique compounds they contain that may be potentially problematic to individuals with specific health problems. Detailed information of the health benefits of each fish and shellfish can be found at the end of the chapter, as can a complete nutritional profile.

2. THE 4 STEPS TO THE BEST TASTING AND MOST NUTRITIOUS FISH AND SHELLFISH includes information to help you select, store, prepare and cook each one of the World’s Healthiest Fish and Shellfish. This section also features Step-by-Step Recipes and Flavor Tips. While specific information for individual fish and shellfish is given in each of the specific chapters, here are the 4 Steps that can be applied to seafood in general, including those not on the list of the World’s Healthiest Foods.

1. the best way to select fish and shellfish

It is important to buy the freshest fish and shellfish possible as the differences in taste and nutritional value are greatly affected by how long they have been “out of the sea.” By talking to the people that work in the seafood departments of your local markets (often known as fishmongers) and asking them about where and how often their market gets its fish, you can ascertain which stores have the freshest selection. Ask questions about the fish’s origin, whether it is farmraised or wild and whether it contains artificial coloring. Using the Fish & Shellfish Guide, determine whether the fish is on the Best Choice, Good Alternative or Avoid list for sustainability. While each individual chapter will provide you with tips on how to make the best selection for individual fish or shellfish, a general rule of thumb follows:

You can tell a lot by how the fish looks: the older the fish, the duller the appearance. Generally speaking, thicker cuts of fish (1” to 2” thick) work better in most recipes as they are more moist and hold together better when cooked. These cuts come from the part of the fish that is closest to the head.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration suggests looking for the following qualities to ensure that you are purchasing fresh fish:

“• Be sure that the fish has been refrigerated or properly iced.

• Fresh fish smells fresh and mild, not “fishy” or ammonia-like.

• The flesh should spring back when pressed.

• The flesh should be firm and shiny (whether it is whole or filleted).

• There should be no darkening around the edges of the fish or brown or yellowish discoloration.

• The eyes should be clear and bulge slightly.

• The gills should be bright red and free from slime.

• Don’t purchase frozen seafood if the packages are open, torn or crushed on the edges.

• Don’t purchase cooked seafood, such as shrimp, crab or smoked fish if it is displayed in the same case as raw fish, since cross-contamination can occur.”

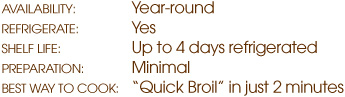

2. the best way to store fish and shellfish

Most fish come from cold waters and require colder temperatures than fruits and vegetables to stay fresh. Fish and shellfish are very perishable and, in contrast to fruits and vegetables, normal refrigerator temperatures of 36°–40°F (2°–4°C) do not inhibit the enzymatic activity that causes them to spoil. Fish and shellfish are best when stored at 28°–32°F (-2°–0°C). I have tried the traditional method of packing fish with ice before placing it in the refrigerator to decrease the temperature. What I discovered was that when the ice melts, the fish ends up sitting in a pool of water losing much of its flavor.

I have since refined the method above, and I want to share with you the best way I found to keep your fish and shellfish fresh. This method is the most effective when you have a large amount of fish.

Place your fish in a zip-lock plastic storage bag, place the bag in a bowl and cover with ice. The benefit to this method is that you don’t have to worry about the fish ending up in a pool of water and losing flavor, so there is less concern about remembering to drain the water away from the fish as the ice melts. However, the down side to this method is that the fish will end up sitting in some of its own juices as they collect inside the bag. Fish stored using this method will last an extra day.

You can use ice packs in place of the ice in both methods. Remember to replace the ice packs as necessary. Although the fish will keep for two to three days using these methods, I recommend using it the day of purchase or within one or two days.

It is interesting what proper storage can do. Many times when my fish has a little fishy odor, I cover it for three to four hours with ice, which I have found to remove the odor. This will not work if the fish has already developed a strong odor.

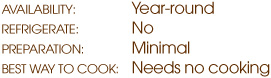

3. the best way to prepare fish and shellfish

Minimal preparation is required for many varieties of fish. You don’t need to start with whole fish because they are usually already filleted or cut into steaks for your convenience when you purchase them at your local market. Yet, some shellfish, like shrimp, scallops and oysters, may require some preparation. In the individual chapters, I will present you with the best ways to prepare specific varieties of fish and shellfish.

4. the healthiest way of cooking fish and shellfish

Although the recipes in the book include the best cooking methods for each individual fish and shellfish, here is some general information on the best ways to cook these foods:

Traditionally, it has been suggested that you cook your fish for approximately 7 minutes for every inch of thickness. Some fish can take a little longer, up to 10 minutes. In the individual chapters, I will provide you with more specific instructions on how to cook your fish. The length of cooking time recommended for each of the recipes is based on the type of fish or shellfish that is to be prepared and the cooking method used for that particular recipe.

Cooking time is also dependent on the desired doneness of the fish or shellfish. For example, tuna is preferably cooked rare to medium-rare while white fish, like striped bass and halibut, can be cooked through and still retain their moistness and flavor. It is very important to pay close attention to the cooking time of fish and shellfish because if it is overcooked, it will be dry and lose much of its flavor.

The variety of tastes and textures of fish and shellfish can be adapted to different cooking techniques, recipes and seasons. With the wide variety of fish and shellfish available, your taste is certain to always be satisfied, while your sense of well-being is enhanced. Unhealthy cooking methods include frying battered fish as well as topping fish with rich sauces. Once you have started with fresh fish and shellfish, it is then important to choose the most appropriate “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods (listed below) for the type of fish and shellfish you are preparing. Detailed descriptions on these methods are given in each of the individual fish and shellfish chapters.

This is a good cooking method to use when you want to quickly cook a fish fillet or steak and seal in its moisture and flavor. It cooks the fish simultaneously on both sides and is a good way to prepare fish if you want to serve it lightly seasoned or with a sauce that you can prepare on the side. (For more on “Quick Broil,” see page 61.)

Poaching is a great way of cooking fish to retain its moisture. To get the most flavor, I like to poach fish with a simple homemade fish and shellfish broth whose essence infuses itself into the fish during cooking. (For more on Poaching, see page 61.)

Many types of fish take well to steaming. You can steam fillets as well as bite-sized pieces of fish, either by themselves or placed on top of vegetables. (For more on “Healthy Steaming,” see page 58.)

If your recipe calls for fish or shellfish cut in bite-size pieces and cooked with other ingredients (such as vegetables or other fish and shellfish), you may want to use this cooking method. It cooks the fish quickly, requires no fat and makes a simmering sauce that can be served with the fish. (For more on “Healthy Sauté,” see page 57.)

A great cooking method if you want to quickly cook a fillet of fish. Because the skillet is hot, it immediately seals the fish and keeps the moisture from escaping. It is a great way to prepare fish during the warmer weather since it does not require you to turn on the oven or broiler, so your kitchen won’t heat up too much. This method is also good when you want to make a sauce to pour over the fish because you can use the same pan to prepare the sauce. The pan will already be hot, plus it will contain a lot of flavor from the fish that will enhance the flavor of your sauce. Stovetop searing is best for oily fish such as tuna or salmon; this method does not work as well on drier varieties of fish.

Q I heard that shrimp, although high in cholesterol, have been found to have more of the “good” (HDL) than the “bad” (LDL). Is this true?

A HDL and LDL aren’t types of cholesterol. HDL stands for “high-density lipoprotein,” and it’s the form in which cholesterol (and other substances) gets transported in the bloodstream back toward the liver from other locations in the human body. LDL, which stands for “low-density lipoprotein,” is the form in which cholesterol (and other substances) gets transported in the bloodstream out from the liver toward other locations in the body. Since shrimp are arthropods, they don’t have a bloodstream like humans with veins, capillaries and arteries, and their cholesterol does not get transported around in the same way. Therefore, shrimp won’t provide you with HDL or LDL.

Shrimp do contain cholesterol, however. Four ounces of shrimp contain about 220 mg of cholesterol. (By comparison, one whole egg contains about 187 mg). Most public health organizations allow at least 200 mg daily.

Yes, mercury contamination of fish is a definite concern for all individuals, particularly for pregnant women, women considering pregnancy and children. Here is a brief exploration of the causes of mercury contamination, whether the health benefits of fish outweigh the mercury risks and how much mercury exposure is considered safe.

Mercury finds its way into the environment from a variety of sources including industrial practices, the incineration of medical and municipal wastes, coal-fired power plants, and the presence in the landfills of mercury-containing products such as fluorescent light bulbs and thermometers. Once it has found its way into the air or the soil, it can move through naturally occurring ecological channels into lakes, streams, rivers and oceans where it becomes a toxic contaminant for fish.

Globalization of the food supply is another reason all individuals need to be concerned about fish and mercury. In certain parts of the world, like the Mediterranean Sea, naturally occurring ore deposits serve as an ongoing source of mercury contamination. A February 2007 report by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has shown that the geographical origin of different fish (i.e., their original habitat) can play a more important role in degree of mercury contamination than many other factors, including the size of the fish or the length of its lifespan. For example, this 2007 EPA report found Atlantic herring (a very small fish) to contain three times the mercury level of Pacific herring, or even many larger fish like cod.

Fish has always been recognized to be an excellent source of protein. In more recent years, cold-water fish have also been recognized as excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids, including EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid). Risk of mercury contamination has thrown some of these nutritional benefits into question, and the benefits-versus-risks of fish have become a matter of widespread debate. Do the nutritional benefits of fish, including their rich omega-3 fatty acid content, outweigh the risk of mercury exposure? I believe the answer to this question is “yes”—but a conditional yes, rather than an unconditional one. Yes, the nutritional benefits of fish outweigh the risk of mercury exposure, provided that (1) lower mercury fish are chosen for consumption and (2) total weekly intake of fish stays fairly restricted. Here’s a closer look at the details involved in this risk-benefit analysis.

A study published in the February 17, 2007 issue of The Lancet answers this question with a definite “yes” based on questionnaire data obtained from more than 10,000 women living in Bristol, United Kingdom in the early 1990s. Researchers found that women consuming over 12 ounces (340 grams) of fish per week during their pregnancy had children with higher IQs and better nervous system development than women who consumed less than this amount. While I respect the quality of the research presented in this study, I do not totally agree with the interpretation of its findings, nor do I believe that the findings are necessarily applicable to U.S. women who are trying to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of fish. My reasoning is fairly simple.

In this 1991–1992 study, women who ate more than 12 ounces of fish per week during their pregnancy were also women who smoked less, had greater amounts of income, were better educated, owned homes and sustained marriages and a family environment in the home. Even though these factors were analyzed statistically by the researchers, I believe that they influenced many aspects of the children’s upbringing that were not adequately analyzed by the research team. (There are many reasons I would expect children from these households to do better on IQ tests). In addition, I am concerned about the fact that no daily food records were ever kept by pregnant women in the study, and no food contents—either nutritional or toxicity-related—were ever subjected to laboratory analysis. The fact that all of the women in the study lived in one town in the United Kingdom 15–16 years ago is also of concern, given the increasingly dynamic nature of the global food supply and geographical origins of fish in the U.S. marketplace.

My own conclusion about the risk-benefit profile of fish is much closer to the position taken by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in its March 19, 2004 advisory on mercury and fish. Like the FDA, I believe that a restriction on fish intake is prudent for all individuals. While setting a 12-ounce guideline for maximum weekly intake of all fish, the FDA also recommended that this 12-ounce intake be restricted to fish and shellfish that are lower in mercury. I support this type of approach, and I like the idea of a dividing line between lower mercury and higher mercury fish—especially when it comes to tuna. (For more on where different fish rate in terms of mercury levels, please see page 457.)

According to a February 2007 EPA report, 39% of all mercury exposure from fish in the U.S. comes from tuna. Of this 39%, 18% comes from canned light tuna, 10% from canned albacore or white tuna and 11% from fresh or frozen tuna. (Swordfish, pollack, shrimp and cod account for another 25% of all mercury exposure from fish.) Even though canned light tuna accounts for almost double the total mercury exposure as canned albacore or white tuna, albacore/white tuna are actually much higher in mercury content. (As a nation, we just eat much more canned light tuna because of the lower price). In the EPA update report, both Pacific and Atlantic albacore tuna (all forms, including canned and fresh) contained about triple the mercury content of both Pacific and Atlantic light (yellowfin) tuna (all forms, including canned and fresh). But it should also be noted that Atlantic tuna was always higher in mercury content than Pacific tuna. The average numbers for Atlantic tuna in this 2007 EPA study were: 0.47 milligrams/kilogram for albacore and 0.31 milligrams/kilogram for yellowfin (light). By comparison, Pacific albacore only contained an average of 0.17 milligrams/kilogram of mercury and Pacific yellowfin (light) only 0.06 milligrams per kilogram.

These differences in mercury exposure from canned tuna make it clear that light tuna (especially Pacific light tuna) is a far better choice than albacore tuna (especially Atlantic albacore tuna) when it comes to mercury exposure risk.

Safe levels of mercury exposure (including consumption of mercury-contaminated fish) are controversial because “safe” really depends on who is trying to stay safe and the specific health dangers they are facing. A very unhealthy person, perhaps in the hospital from weakness and poor nourishment, can withstand very little toxic exposure, including exposure from mercury-contaminated fish. An extremely healthy person, full of vitality, with good nutrient reserves and a robust ability to get rid of toxins would be very likely to remain fully healthy while consuming a moderate amount of mercury-contaminated fish. Exactly how much could such a person eat? Here the answer would depend on the person’s age, physical activity level, body size (height and weight) and other factors, including immediate performance goals. An athlete facing endurance training might not want to deplete his or her nutrient supplies at all, and might not want to ask his or her body to engage in any unnecessary detoxification of mercury. In this case, the choice might be to avoid any mercurycontaminated fish. A well-nourished, healthy person just wanting to stay generally healthy, i.e., stay safe from premature aging or premature onset of chronic disease, might choose to eat canned light tuna twice a week and simply stay with the FDA general health guidelines.

highlights

Tuna is second only to shrimp in popularity largely due to the demand for canned Tuna. While canned Tuna may be convenient, it does not compare to the wonderful taste treat provided by fresh Tuna. Fresh Tuna has been enjoyed by coastal populations throughout history, while smoked and pickled Tuna have been widely consumed since ancient times. The firm, dense flesh of Tuna gives it one of the meatiest flavors and textures of any fish. Because the moisture content of Tuna can be easily lost through cooking, making it tough and dry, I want to share with you how the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods can not only keep Tuna moist, but also bring out its wonderful flavor.

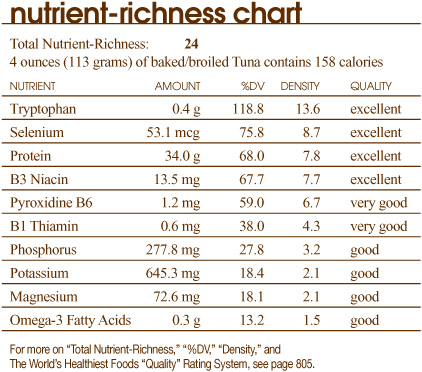

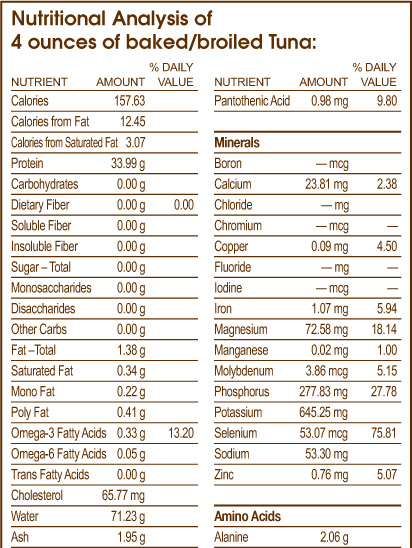

Like other varieties of fish, Tuna is a rich source of protein. Its omega-3 fatty acids are important for cardiovascular health and reducing inflammation, while its selenium, potassium and magnesium also support a healthy heart. Tuna is an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” because not only is it high in protein but it is also low in fat. (For more on the Health Benefits of Tuna and a complete analysis of its content of over 60 nutrients, see page 468.)

Tuna are found in the warm water areas of the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans as well as the Mediterranean Sea. The meat is a reddish color because Tuna are hydrodynamically designed to swim more than other species of fish, resulting in greater oxygenation of their muscle mass. Tuna are not farmraised. Popular varieties include:

Weighing up to 130 pounds, it has pinkish flesh, which turns white when cooked, and a delicate taste. In Hawaii, it is called tombo. Most Albacore Tuna is canned and sold as Albacore, white Tuna or white chunk. Although it is sometimes sold in markets and served in restaurants, it is not as flavorful or as popular as Yellowfin or Ahi.

True to its name, the fins and tail of this variety are a distinctive yellow color. The meat is pale, fatty, firm and dense; it is usually canned as “light” Tuna. It is called Ahi in Hawaii. It is sold fresh as steaks.

It is the largest member of the Tuna family, weighing up to 400 pounds. It is difficult to find, has reddish brown flesh and is fattier than other varieties. Bluefin is very tasty and used for sashimi.

This small (up to 5 pounds) and most frequently caught variety of Tuna has dark red flesh and is usually canned with Yellowfin Tuna and sold as “light” Tuna. The Japanese often use dried bonito for seasoning and garnish.

Canned and fresh Tuna are available throughout the year.

In the spring of 2004, due to concerns about mercury levels in certain fish, the FDA issued recommendations that children, pregnant and nursing women, and women of childbearing age should limit their consumption of canned Albacore Tuna and Tuna steaks to no more than 6 ounces per week and light Tuna to no more than 12 ounces per week. (For more on Mercury in Fish, see page 463.)

Turning Tuna into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select tuna

Fresh Tuna such as Yellowfin Tuna (also called Ahi) is the most flavorful and the best type of Tuna to cook. Tuna is sold in many different forms. It is available fresh as steaks, fillets or pieces, but is most popular in its canned form. (See The Guide for mercury content, page 457.)

Just as with any seafood, it is best to purchase fresh Tuna from a store that has a good reputation for having a frequent turnover of their fresh fish. Get to know a fishmonger (the person who sells the fish) at the store, so you have someone from whom you can purchase your fish with confidence.

Fresh whole Tuna should be displayed buried in ice, while fillets and steaks should be placed on top of the ice. The flesh should be firm to the touch. Try to avoid purchasing Tuna that has dry or brown spots.

Smell is a good indicator of freshness. Since a slightly “off” smell cannot be detected through plastic, if you have the option, it is preferable to purchase displayed fish as opposed to pieces that are prepackaged. Once the fishmonger wraps and hands you the fish that you have selected, smell it through the paper wrapping and return it if it has a very strong fishy odor.

If you are going to have a full day of errands after you purchase your Tuna, be sure to keep a cooler in the car to ensure it stays cold and does not spoil.

CANNED TUNA is available either solid or in chunks and is packaged in oil, broth or water. Although the Tuna packed in oil usually has the greatest amount of moisture, it also has the highest fat content, and the oils in which it is packed are high in omega-6 fats. Since omega-6 fatty acids and omega-3 fatty acids compete for the same enzymes that activate them for use in the body, and most Americans already consume too many omega-6 fats in comparison to omega-3s, it is best to purchase Tuna packed in water or broth (for more on Omega-3 Fatty Acids, see page 770). Oftentimes, cans of Tuna do not specify the species of Tuna that was canned except to indicate that it is either light Tuna (Skipjack and/or Yellowfin) or white Tuna (usually Albacore).

LIGHT CANNED TUNA contains less mercury than white or albacore Tuna. You can find canned specialty Tuna, which is pole-caught with no bycatch and therefore ecologically sustainable. The specialty Tunas claim to have higher concentration of omega-3 fatty acids and lower concentrations of mercury and can be found online and in specialty and natural food stores.

Fresh Tuna, like other fish, is very perishable, and normal refrigerator temperatures of 36°–40°F (2°–4°C) do not inhibit the enzymatic activity that causes it to spoil; it is best when stored at 28°–32°F (-2°–0°C). I have tried various methods to find the best way to store Tuna including packing the Tuna with ice before placing it in the refrigerator to decrease the temperature. Although this method kept the Tuna cool, once the ice melted, the Tuna ended up sitting in a pool of water, causing it to lose much of its flavor.

I have refined this method and want to share with you the best way to keep your Tuna fresh. Remove Tuna from store packaging, rinse and place in a plastic storage bag as soon as you bring it home from the market. Place Tuna in a large bowl and cover with ice cubes or ice packs to reduce the temperature of the Tuna. Although fresh Tuna will keep for a few days using this method, I recommend using it within a day or two of purchase. Remember to drain off the melted ice water and replenish the ice or replace the ice packs as necessary.

If you have more Tuna than you can use, freezing will increase its shelf life to 3 –6 months.

3. the best way to prepare tuna

Fresh Tuna is usually bought precut in steaks and requires very little preparation. Make sure it is very fresh. The skin of Tuna is inedible and bitter, so you rarely see Tuna sold with skin on.

Rinse and wipe Tuna dry. Rub with a little fresh lemon juice and season with salt and pepper before cooking. Tuna is excellent if given the chance to marinate for 24 hours before cooking. There are many marinades that are suitable for fresh Tuna.

Canned Tuna requires no preparation and can be used in a variety of different ways.

4. the healthiest way of cooking tuna

Searing Tuna is the best for keeping it moist and tender. Tuna cooks very quickly and can be prepared in 2–3 minutes as it is best cooked rare. If you want your Tuna cooked through, cook for 7–10 minutes for each inch of thickness; this is the general rule for cooking fish. It can be easily overcooked and become dry, so be sure to watch your cooking times. “Quick Broil” is the method I found best to sear Tuna. (Cooking times are based on 1-inch thickness. Fish that is 1/2inch thick will take half the amount of time.)

To prevent overcooking Tuna, I highly recommend using a timer. And since Tuna cooks in only 2–3 minutes, it is important to begin timing as soon as you place it onto the skillet. Remove Tuna from the heat and transfer it to a plate after the allocated time because it will continue to cook if left in the pan. Overcooked Tuna will become dry and tough.

I don’t recommend cooking Tuna in oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and potentially create harmful free radicals. (For more on Why it is Important to Cook without Heated Oils, see page 52.)

Here are questions that I received from readers of the whfoods.org website about Tuna:

Q I often order Tuna in restaurants and wanted to know what the best way is for me to have it prepared (i.e., rare, medium, etc.)? Does it make a difference in terms of its nutritional value?

A There are slight nutritional differences between fish that is cooked medium rare or medium, and in many nutrient categories these differences would not be great enough to rule out either choice as a healthy option. In fact, using Tuna as an example, there are only very slight differences between the vitamin E, vitamin A and omega-3 fatty acid content of raw Tuna in comparison to medium broiled Tuna. The protein content of fish will not change significantly even if the fish is overcooked. However, an overcooked fish is usually dry, more rubbery in texture, non-flaky and lacking in flavor. In terms of nutrition, you’re also going to want to look for restaurants that pay close attention to the overall freshness of the fish (length of time since it was caught). Of course, the more recent the catch, the better the nutritional value.

Q How do you know when fresh Tuna has gone bad?

A Use smell as your guide. Does the Tuna have a funny, fishy, strong, “off” odor? If so, it has probably gone bad. Also, how long has it been stored? Unless the Tuna was caught the day before you purchased it, I wouldn’t recommend storing it in the refrigerator for more than one or two days. Especially with fish and meat, I like to follow the old kitchen adage–when in doubt, throw it out! So if you are unsure of whether it is bad, I would suggest not using it.

Q How does vacuum cooking work?

A Vacuum cooking typically involves the use of a plastic pouch to surround a food and provide a small, enclosed space in which a combination of steam and heated air can cook the food. I’ve usually seen this process applied to meats and fish. These foods are vacuum-sealed together with spices and seasonings, and the flavor of these seasonings can be very effectively retained through the use of vacuum packing. However, I don’t recommend this technique due to the possible risk of plastic migration from the pouch into the food. Such migration of plastic has been clearly demonstrated in research with the use of plastic bags in microwave ovens. So yes, vacuum cooking works, but I do not recommend vacuum cooking due to the toxicity risk I’ve described.

Q I don’t care for any type of seafood, but I still want the benefits that seafood provides. Are there other foods that can provide me the same benefits?

A No food will have the same exact benefits in totality that another food provides. Yet, you can look for other foods that also contain the nutrients concentrated in the original food.

For example, seafood has gained a lot of recent acclaim because it is rich in omega-3 fatty acids, a group of nutrients with anti-inflammatory properties that have shown benefit for overall health. The omega-3 fatty acids that are concentrated in seafood are the longer chain varieties, notably eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

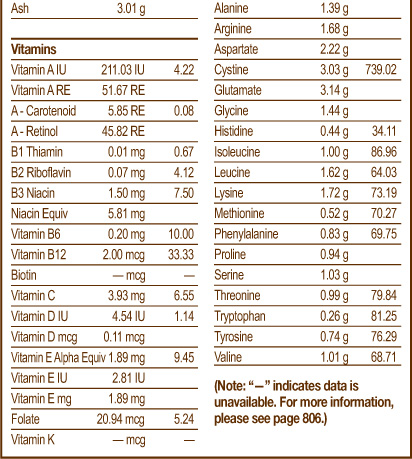

Unfortunately, no other food is as concentrated in these long-chain fatty acids as seafood. Yet, certain foods are rich in the omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), which is the precursor to EPA and DHA. ALA is found in some vegetables and is especially concentrated in flaxseeds and walnuts. About 10% of ALA gets converted to these longer-chain fatty acids, yet most of it seems to be converted to EPA, with less being converted to DHA. Many vegetarians concerned about their omega-3 intake often include nuts and seeds in their diet and then may take an algae supplement rich in DHA to make sure that they get adequate amounts of this important nutrient. For more information about omega-3 fatty acids, see page 770.

Tuna is a good source of the omega-3 fatty acids, notably EPA and DHA, which provide a broad array of cardiovascular benefits. Omega-3s benefit the cardiovascular system by helping to prevent erratic heart rhythms, making blood less likely to clot inside arteries (which is the ultimate cause of most heart attacks) and reducing triglyceride levels. Because inflammation is a key component in converting cholesterol into artery-clogging plaques, the ability of omega-3s to reduce inflammation helps prevent atherosclerosis; therefore, it further reduces the risk of heart disease. Omega-3 fatty acids may be partially responsible for a recent study’s finding that eating fish lowers the risk of certain types of strokes. Tuna is also a concentrated source of other heart-health-promoting nutrients including selenium, vitamin B6, potassium and magnesium.

Eating fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as Tuna, may help to reduce stress. A recent study found a relationship between consuming fish rich in omega-3 fats and a lower hostility rate in young adults. Other studies have suggested that DHA supplementation can reduce levels of aggression and enhance the stress response. In addition, plasma levels of omega-3 fatty acids have been found to be reduced in people who express more aggressive behavior.

Eating fish may protect against age-related macular degeneration (ARMD), a currently untreatable disease that causes fuzziness, shadows or other distortions in the center of vision. In a recently published study, investigators found that those who ate the greatest amount of fat overall increased their risk of ARMD, while those who ate fish reduced their risk of developing the eye disease. One of the reasons that fish like Tuna may benefit eye health is that they provide DHA, which is actually concentrated in the retina of the eye and may help protect and promote healthy retinal function.

Tuna is rich in selenium, a necessary component of one of the body’s most important antioxidants, glutathione peroxidase, which is critical for the liver to detoxify and clear potentially harmful compounds such as pesticides, drugs and heavy metals from the body. Selenium also helps prevent cancer and heart disease.

Tuna is also a concentrated source of many nutrients providing additional health benefits. These nutrients include muscle-building protein, energy-producing vitamin B1 and phosphorus, and sleep-promoting tryptophan.

STEP-BY-STEP The Healthiest Way of Cooking Tuna

highlights

Shrimp may be small in size, but they are huge in nutritional value and taste appeal. Close relatives to lobster and crayfish, Shrimp’s delicious taste and ease of preparation make them the most popular seafood in the United States; they are consumed more than salmon or tuna. The English name for Shrimp is prawns. Shrimp prepared with garlic is called scampi in Italy. Shrimp can be served hot or cold and offer a great alternative to meat protein. I want to share with you how using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” Shrimp can enhance their flavor in just a matter of minutes!

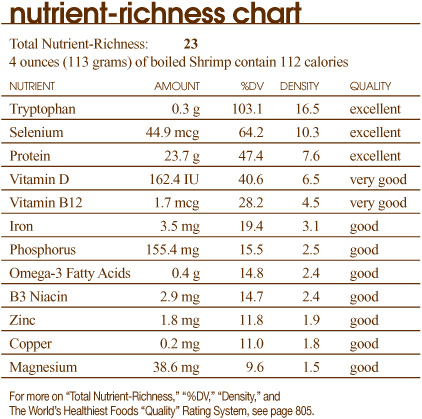

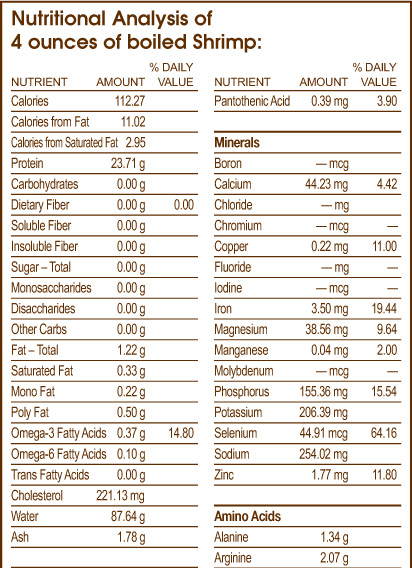

Shrimp are an excellent source of protein and a good source of those hard-to-find, health-promoting omega-3 fatty acids, which are not only important for heart health, but also for reducing inflammation. They are a rich source of minerals, including copper, selenium and zinc, which provide powerful antioxidant protection against the oxidative damage to cellular structures caused by free radicals. Shrimp are an ideal food to add to your “Healthiest Way of Eating” not only because they are high in nutrients and low in fat, but also because they are low in calories making them a good choice for healthy weight control: 4 ounces of Shrimp contain only 112 calories! (For more on the Health Benefits of Shrimp and a complete analysis of their content of over 60 nutrients, see page 474.)

Although farmraised Shrimp are now sold in the United States, most Shrimp are still caught in the wild. Over 300 different species of Shrimp are harvested worldwide, and within these 300 species are thousands of different varieties. Shrimp freeze well, and most Shrimp in the market have been frozen.

Saltwater Shrimp are classified as either warm-water or cold-water Shrimp. Warm-water shrimp are caught off the coast of North Carolina, Texas, California and Mexico; they include White, Brown, Rock and Pink Shrimp. Pink Shrimp are three to four inches in length, reddish-pink in color and the most popular variety in the United States. Cold-water Shrimp are caught in the north Atlantic and north Pacific; they have firmer meat than warm-water varieties and a sweeter flavor. Some common varieties of Shrimp include:

The most popular variety is northern Pink Shrimp or Maine Shrimp.

Also known as Alaskan prawns, these are caught in the Pacific Ocean off the West Coast of the United States.

These large Shrimp measure six to twelve inches in length.

They are raised both domestically or can be imported. The farm raising of Shrimp in the U.S. is well regulated, and farmers must adhere to laws limiting environmental impact. Imported Shrimp production is not well regulated.

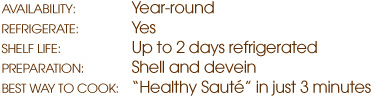

Fresh and frozen Shrimp are available throughout the year.

Shrimp may be considered a high cholesterol food for individuals watching their cholesterol intake (221 mg in a 4-ounce serving). Shrimp also contain purines, which may be problematic for certain individuals. (For more on Purines, see page 727.)

Turning Shrimp into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select shrimp

Pink Shrimp from Oregon and spotted Shrimp from British Columbia are the best Shrimp to purchase. However, they may be difficult to find, so U.S. farmed or trawl-caught Shrimp or wild Shrimp from the Canadian Atlantic are your next best alternatives. Avoid other imported Shrimp whenever possible. (For more on Sustainability, see page 473.)

The first step in selecting the best Shrimp is to find a store with a good reputation for having a fresh supply of fish and shellfish. Get to know a fishmonger (person who sells the seafood) at the store so you can have a trusted person from whom you can purchase your Shrimp.

Fresh Shrimp should have firm bodies that are still attached to their shells, which should be free of black spots since this indicates that the flesh has begun to break down. In addition, the shells should not appear yellow or gritty as this may reflect the use of sodium bisulfate or another chemical to bleach the shells. Whenever possible, purchase displayed Shrimp rather than prepackaged Shrimp. Smell is a good indicator of freshness, and it is difficult to detect smells through the plastic of prepackaged seafood. I have found that fresh Shrimp never smells fishy but more like seawater. Once the fishmonger wraps and hands you the Shrimp, smell it through the paper wrapping and return it if it does not smell right.

Since Shrimp freeze well, it is best to buy Shrimp while still frozen. This will ensure you are getting the freshest Shrimp possible because they are usually frozen as soon as they are caught. One pound of frozen Shrimp with shells on will yield about a half pound of cooked shelled Shrimp. Frozen Shrimp have the longest shelf life and can be kept for several weeks, whereas fresh Shrimp will only keep for a day or two.

The number of Shrimp you get per pound will depend on their size:

• Small Shrimp: 40-50 per pound

• Medium Shrimp: 31-40 per pound

• Large Shrimp: 26-30 per pound

• Extra Large Shrimp: 21-25 per pound

• Jumbo Shrimp: 16-20 per pound

Shrimp that come over 40 per pound are usually precooked and used for salads and Shrimp cocktail.

If you are going to have a full day of errands after you purchase your Shrimp, be sure to keep a cooler in the car to ensure they stay cold and do not spoil.

2. the best way to store shrimp

Like most seafood, Shrimp are very perishable and normal refrigerator temperatures of 36°– 40°F (2°–4°C) do not inhibit the enzymatic activity that causes them to spoil; they are best when stored at 28°–32°F (-2°–0°C). I have tried various methods to find the best way to store Shrimp, including packing the Shrimp with ice before placing it in the refrigerator to decrease the temperature. Although this method kept the Shrimp cool, once the ice melted, the Shrimp ended up sitting in a pool of water, causing them to lose much of their flavor.

I have refined this method and want to share with you the best way to keep Shrimp fresh. Remove Shrimp from store packaging, rinse and place in a plastic zip-lock bag as soon as you bring them home from the market. Place in a large bowl and cover with ice cubes or ice packs to reduce the temperature of the Shrimp. Although fresh Shrimp will keep for a few days using this method, I recommend using your Shrimp within a day or two of purchase. Remember to drain off the melted ice water and replenish the ice or replace the ice packs as necessary. Frozen Shrimp can be kept for several weeks. Cooked shrimp should be consumed within 24 hours.

3. the best way to prepare shrimp

Properly preparing Shrimp helps to ensure that the Shrimp you serve will have the best flavor and retain the greatest number of nutrients.

Defrost frozen Shrimp in the refrigerator. Do not thaw Shrimp at room temperature or in a microwave.

Remove the shell by pulling it away from the Shrimp meat starting at the legs on the underside of the Shrimp. The tail can be removed, if desired. With a sharp paring knife, make a slit down the back of the Shrimp about ⅛ inch deep. You may see a dark string (the intestines of the shrimp) that runs the length of the Shrimp. Rinse under cold water to remove.

If you are not going to remove the shells, rinse Shrimp under cold running water and pat dry before cooking.

4. the healthiest way of cooking shrimp

The best way to cook Shrimp is by using methods that will keep them moist and tender. Shrimp can be easily overcooked and become dry, so be sure to watch your cooking times. Shrimp are delicate, and I have found that they can be best prepared by using the “Healthy Sauté” method. (For more on “Healthy Sauté,” see page 57.)

While grilled Shrimp tastes great, make sure that they do not burn. It is best to grill Shrimp on an area without a direct flame as the temperatures directly above or below the flame can reach as high as 500°F to 1000°F (260°C to 578°C). Extra care should be taken when grilling as burning can damage nutrients and create free radicals that can be harmful to your health. (For more on Grilling, see page 61.)

Shrimp cook quickly and are easily overcooked. To prevent overcooking Shrimp, I highly recommend using a timer. And since Shrimp cook in only 3–4 minutes, it is important to begin timing as soon as you place them into the skillet. Shrimp will become tough and lose their flavor when overcooked.

I don’t recommend cooking Shrimp in oil because high temperature heat can damage delicate oils and potentially create harmful free radicals. (For more on Why it is Important to Cook without Heated Oils, see page 52.)

Here is a question that I received from a reader of the whfoods.org website about Shrimp:

Q Should I devein my Shrimp, and what is the “vein” that gets removed?

A Some people prefer to devein their Shrimp while others don’t (I actually prefer shrimp deveined). The reason is not just from an appearance perspective, but because the “vein” is actually the intestines of the Shrimp and any material that may be in it.

Many people are confused about the fat and cholesterol content of Shrimp. Shrimp is very low in total fat, yet it has a high cholesterol content (about 220 mg in 4 ounces, or 13 large boiled Shrimp), which has caused some people to avoid eating it. However, based on research involving Shrimp and blood cholesterol levels, avoidance of Shrimp for this reason may not be justified.

In a peer-reviewed scientific study, researchers reviewed the effect of a diet containing Shrimp or eggs on the cholesterol levels of subjects with normal lipid levels. The results of this randomized crossover trial showed that while LDL levels (“bad” cholesterol) increased by 7% in those eating the Shrimp diet, HDL levels (“good” cholesterol) increased by 12%. In contrast, subjects eating the egg diet had a 10% increase in LDL levels and only a 7% increase in HDL levels. The results indicated that the Shrimp diet produced significantly lower ratios of total to HDL cholesterol and lower ratios of LDL to HDL cholesterol than the egg diet. In addition, subjects who ate the Shrimp diet lowered their levels of triglycerides by 13%.

Shrimp are a very good source of vitamin B12, an important nutrient for a healthy heart since this B vitamin is necessary for keeping levels of homocysteine low. Homocysteine is a molecule that can directly damage blood vessel walls and is considered a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Shrimp is also a good source of cardioprotective omega-3 fatty acids, noted for their anti-inflammatory effects and suggested ability to prevent the formation of blood clots. They are also a concentrated source of other heart-healthy nutrients including niacin and magnesium.

Shrimp are a concentrated source of many antioxidants, including selenium, copper and zinc. Selenium is a co-factor of glutathione peroxidase, which is used by the liver to detoxify a wide range of potentially harmful molecules. Accumulated evidence from prospective studies, intervention trials and studies on animal models of cancer has suggested a strong inverse correlation between selenium intake and cancer incidence. Copper is a component of superoxide dismutase, an antioxidant enzyme that scavenges free radicals in the lungs and the red blood cells. Zinc is necessary for keeping the immune system functioning properly.

Shrimp are also a concentrated source of many other nutrients providing additional health benefits. These nutrients include muscle-building protein, energy-producing iron, bone-building vitamin D and phosphorus, and sleep-promoting tryptophan.

STEP-BY-STEP The Healthiest Ways of Cooking Shrimp

highlights

Salmon is an incredible food providing exceptional flavor and nutrition. The story of Salmon before it reaches your table is just as remarkable. As a family of fish, Salmon have an amazing life cycle. Born in fresh water, they travel to saltwater oceans, returning not only to fresh water, but to the very place where they were spawned! As with other types of fish, it is important to cook Salmon properly to enhance its flavor and maintain its moisture. I want to share with you how to prepare Salmon using the “Healthiest Way of Cooking” methods for a dish that only takes minutes to prepare but one you will want to share with your favorite guests.

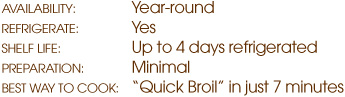

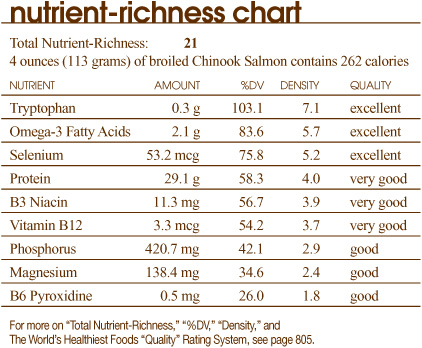

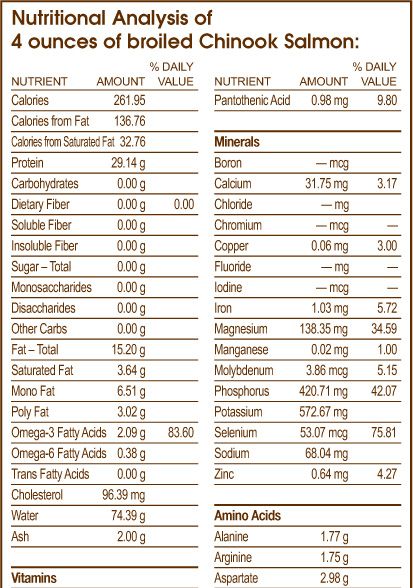

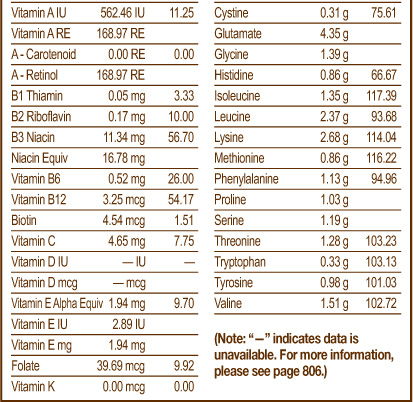

Low in calories and saturated fats and high in protein, wild-caught Salmon is one of the best sources of those hard-to-find, health-promoting fats known as the omega-3 fatty acids, specifically eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). These fatty acids play an important role as anti-inflammatory agents and are also sorely deficient in the American diet. Add the benefit of Salmon’s EPA and DHA to its being a rich source of protein, vitamins and minerals, many of which act as powerful antioxidants, and you have some of the many reasons why Salmon is included among the World’s Healthiest Foods and is a valuable addition to your “Healthiest Way of Eating.” (For more on the Health Benefits of Salmon and a complete analysis of its content of over 60 nutrients, see page 480.)

The life cycles of the different species of Salmon range from two to five years, and the diet they consume during that time accounts for their wide variation in color (from pink to red to orange) and the differences in their fat content and flavor. Salmon can be either caught wild or are farmraised. They are sold as fillets, steaks and whole fish.

All of the wild-caught Salmon we find in the market are from the Pacific coast and are labeled as “Wild Salmon.” They have a deeper, more complex and fuller flavor than farmraised Salmon. Given the concerns that have been raised about farmraised fish (see Farmraised Salmon Section), I recommend choosing wild-caught Salmon whenever possible.

The largest of all of the Pacific Salmon, they remain out to sea for 4 to 5 years before they spawn and die. The flesh of Chinook or King Salmon can range from deep red to almost white. It is higher in fat content and has a better flavor than other species of Salmon. One 4-ounce serving contains 2.1 grams of omega-3 fatty acids. King Salmon comes fresh, frozen and smoked.

It has deep red-colored flesh and is considered the finest of the canned Salmon. It is also sold fresh in season and has the second highest fat content with a 4-ounce serving containing 1.5 grams of omega-3 fatty acids. Sockeye Salmon are out to sea for three to four years before they spawn and die.

One 4-ounce serving of Humpback Salmon contains 1.5 grams of omega-3 fatty acids. It has soft, pale-pink flesh and bland flavor and is usually canned. Pink Salmon are out to sea for two years before they spawn and die.

This species ranges in size from 5 to 15 pounds, has red colored flesh and a lower fat content than Chinook or Sockeye; a 4-ounce serving contains 1.3 grams of omega-3 fatty acids. It is sold fresh. Coho Salmon are out to sea for three to four years before they spawn and die.

Lower in omega-3 fatty acids with only 1.0 grams per 4-ounce serving, this species of Salmon has firm, coarse flesh that is pale in color. It is oftentimes used for smoked Salmon. Chum Salmon are out to sea for three to four years before they spawn and die.

Salmon raised in pens and fed fish pellets for nourishment results in an omega-3 fatty acid to omega-6 fatty acid ratio that is different than found in wild Salmon; farmed Salmon have far more omega-6 fatty acids in relation to omega-3 fatty acids. Because the pellets do not give them their natural pink color, their feed must include an artificial coloring for their flesh to have a pink hue.

In addition, a number of concerns have been noted about Salmon farming. Crowded pens result in a large amount of waste discharge in the water that disrupts the ecological balance of the environment where the pens are located. Because these feed lot rearing conditions are also very conducive to the development of disease, farmed Salmon are protected with the use of antibiotics. As noted above, they are fed artificial coloring to achieve the peach-colored flesh naturally present in wild Salmon (a result of their consumption of carotenoid-rich krill). farmraised Salmon may also cause problems in the wild since some do escape from their pens and end up competing with wild stocks for resources or interbreeding with wild stocks and changing their genetic make-up.

Farmed Salmon are lower in protein (because they do not swim long distances) and fattier and higher in saturated fats than their wild counterparts. While they contain omega-3 fatty acids, they also contain significantly higher amounts of proinflammatory omega-6 fatty acids, making the ratio between these two types of fats less desirable than those found in wild stocks of Salmon.

FDA statistics on the nutritional content (protein and fat ratios) of farmed versus wild-caught Salmon detail many findings. They show that the fat content of farmed Salmon is excessively high (30–35% by weight) and that wild Salmon have a 20% higher protein content. And while wild Salmon have a 20% lower overall fat content than farmraised Salmon, they have 33% more omega-3 fatty acids.

When you purchase Atlantic Salmon, you are purchasing farmraised Salmon. farmraised Salmon comes from Norway, Chili and New Zealand as well as the United States. One thing to remember that is not well-known is that not only Atlantic but Norwegian Salmon are now almost always generic terms for farmraised Salmon.

New labeling regulations now specify that farmraised Salmon must be labeled as “Farmraised” and indicate that artificial colorings were used in processing. Wild-caught Salmon must be labeled as “Wild Salmon.” These new labeling regulations make distinguishing farmraised from wild Salmon at the market easy and clear.

(For more on wild-caught versus farmraised Salmon see “What are the Nutritional Differences between Wild-Caught and Farmraised Fish?” page 495.)

Canned Salmon used to always be wild-caught, but not anymore. Some companies have started to can farmed Salmon, so be sure to read the label. Remember that when the label on the can reads Atlantic or Norwegian Salmon, the Salmon was farmraised.

It’s always best to enjoy any fish during its peak season. These are the months when its concentration of nutrients and flavor are highest, and its cost is at its lowest. The different species of wild Salmon are available during different times of the year with the peak of their respective seasons running between February and November. Although farmraised Salmon is available year-round, I recommend eating wild Salmon whenever possible.

Salmon contains purines, which may be problematic for some individuals. Recent studies have shown that farmraised Salmon have high levels of PCBs and dioxins. Synthetic dyes are also used to give them a pink coloration. It is recommend that farmraised Salmon not be eaten more than once a month. (For more on Purines, see page 727.)

Turning Salmon into a flavorful dish with the most nutrients is simple if you just follow my 4 easy steps:

1. The Best Way to Select

2. The Best Way to Store

3. The Best Way to Prepare

4. The Healthiest Way of Cooking

1. the best way to select salmon

All species of wild-caught Salmon from Alaska, Washington, Oregon and California are sustainable choices. King Salmon, Sockeye and Coho Salmon are the best for flavor.

The first step in selecting the best Salmon, like all other fish, is to find a store with a good reputation for having a fresh supply of seafood and get to know a fishmonger (person who sells the seafood) at the store, so you can have a trusted person from whom you can purchase your fish.

Fresh whole Salmon should be displayed buried in ice, while fillets should be placed on top of the ice. Whenever possible, purchase displayed fish rather than prepackaged fish. Smell is a good indicator of freshness, and it is difficult to detect smells through the plastic of prepackaged fish. I have found that fresh fish never smells fishy; instead, it smells like seawater. Once the fishmonger wraps and hands you the fish, smell it through the paper wrapping and return it if it does not smell right.

If you are going to have a full day of errands after you purchase your Salmon, be sure to keep a cooler in the car to ensure it stays cold and does not spoil.

2. the best way to store salmon

Like most fish, Salmon is very perishable, and normal refrigerator temperatures of 36º–40ºF (2°–4°C) do not inhibit the enzymatic activity that causes it to spoil; it is best when stored at 28º–32ºF (-2°–0°C). I have tried various methods to find the best way to store Salmon including packing the Salmon with ice before placing it in the refrigerator to decrease the temperature. Although this method kept the Salmon cool, once the ice melted the Salmon ended up sitting in a pool of water, causing it to lose much of its flavor.

I have refined this method and want to share with you the best way to keep your Salmon fresh. Remove Salmon from store packaging, rinse and place in a plastic storage bag as soon as you bring it home from the market. Place in a large bowl and cover with ice cubes or ice packs to reduce the temperature of the fish. Although fresh Salmon will keep for a few days using this method, I recommend using your Salmon as soon as possible, within a day or two. Remember to drain off the melted water and replenish the ice water or ice packs as necessary.

Remember that fish not only starts to smell but will dry out or become slimy if it is not stored correctly.

3. the best way to prepare salmon

Salmon comes in the form of steaks, fillets or whole fish. Rinse under cold running water and pat dry before cooking.

4. the healthiest way of cooking salmon

The best way to cook Salmon is by using methods that will keep it moist and tender. Salmon can be easily overcooked and become dry, so be sure to watch your cooking times.

Salmon is a delicate fish, and I have found that it can be most easily prepared by using the “Quick Broil” method. You do not have to skin Salmon before cooking. As a general rule, each inch of thickness requires 7–10 minutes of cooking; fish that is 1/2inch thick will take half the amount of time. (For more on “Quick Broil,” see page 60.)

While grilled Salmon tastes great, make sure it does not burn. It is best to grill Salmon on an area without a direct flame as the temperatures directly above or below the flame can reach as high as 500ºF to 1000ºF (260°C to 538°C). Extra care should be taken when grilling, as burning can damage nutrients and create free radicals that can be harmful to your health. (For more on Grilling, see page 61.)