‘The first two months were more amazing, but also harder than I’d expected them to be. I’d spent all my time preparing for – obsessing on – the birth that I almost forgot there’d be a real baby at the end of it. With my next baby I’m giving it an awful lot more thought.’

KEIRA, 32, MOTHER OF MARK (2), PREGNANT WITH HER SECOND CHILD

SIX THINGS TO SORT OUT WELL IN ADVANCE

- Immediate postpartum help. Make a list of friends/family who have offered to help when the baby comes and organise them accordingly.

- Your relationship. If you have relationship troubles try and work through them now: the demands of a new baby can turn a fixable relationship into a crisis.

- Acquiring basic baby equipment. You don’t need much, really, but it’s worth getting what you do need before the baby is born, as shopping with a newborn can be fraught (see Find Out More).

- Getting supplies to help you recover postpartum. There are some simple things that can make a big difference to your comfort in the hours, days and weeks after the birth. See page.

- Childcare. Good childcare facilities can be booked up a year or more in advance so, if you’ll need one, start to investigate nurseries when you’re pregnant. You can always change your mind when you get to know your baby. Also consider whether you need childcare for your other child/children, both for the birth itself, and for the weeks afterwards. If you have a first child under school age, you’ll almost certainly need more help than you think you will.

- Your camera. Yes, really: if it doesn’t work, get it fixed or buy one (digital can be good for emailing pics to friends/family) or you’ll regret it. And if you think you’re not the camcorder type, you’re about to be wrong. Get one now if you can possibly afford it.

Why bother planning?

Nowadays we are encouraged to leap up the moment we’ve given birth, slap on our lippy and pretend nothing has happened. We’re congratulated if we leave hospital early, manage to squeeze into our jeans and not complain about our sore bits. Consequently, many of us have unrealistic expectations of ourselves postpartum. We’re supposed to be ‘successful’, to ‘bounce back’, to get our lives back. But our lives, not to mention bodies – have changed. The world shifts when you have a baby: it now contains someone you love more than you love yourself; someone you’d die for without hesitation; someone whose smile is awe-inspiring, who fills you with emotions deeper and more mind-blowing than any you’d imagine possible. This someone also keeps you up all night, poos, wees and throws up on you, eats endlessly, and can be funny, shocking, adorable and alarming. Sometimes all at once. Like birth, you can’t control what sort of baby you have. But you can prepare yourself to cope brilliantly with this transition period: those first few fraught and magnificent weeks.

Birth takes recovery – in the old days this was known as a ‘lying-in period’. Childbirth educator Sheila Kitzinger has dubbed the period after your baby’s birth, when you two (or three, or more) should be simply reveling in your new found love, the ‘babymoon’. It’s a time for bonding and you’ll never get it back. But unfortunately nowadays most of us seem to ignore this notion. And this is just not sensible. It’s quite simple: if you prepare properly for the immediate postpartum period, and look on it (at least for the first couple of weeks) as a time to rest and recuperate, you’ll really be able to enjoy your baby. Leave it all to chance, and you may find yourself – at times – drowning rather than waving.

A cautionary tale from Julia:

When I was pregnant with my first baby, Keaton, I covered all the birth eventualities but I never prepared for my postpartum. The books focused on childbirth and that seemed overwhelming enough. I just thought I’d come home, change nappies, be a tad tired… no big deal. When I got home from the hospital with Keaton, my fever rose but I was so focused on the baby that I ignored it. Eventually I was hospitalised with an infection. Meanwhile Keaton developed jaundice. I wanted Buckley to be at home with him, so I was completely alone in hospital during these heartbreaking days. ALL of this nightmare was avoidable and it took a long time to bond with my son: I remember telling my midwife he was nice, but I didn’t feel connected to him. With my second baby, Larson, I was so anxious about my postpartum that I actually paid a chef to make months’ worth of meals and load them in our freezer. We asked our fortnightly house cleaner to come every week for a bit. We organised a new laundry system. We lined up friends and neighbours to come and play with Keaton. We prepared like lunatics and had a great postpartum.

Julia’s first postpartum was unusually dire. There are, however, countless milder variations on such stressful times that really could be mitigated with a bit of planning. And – as Julia’s second postpartum showed – if you plan for the worst, you’ll get the best.

FIVE COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT POSTPARTUM

These five came up repeatedly when we asked women with more than one child what their biggest misconceptions were first time around:

- I’ve run a business, I can manage a small baby. You’re used to managing teams and running complex projects so how hard could dealing with a newborn be? The challenges aren’t comparable: motherhood strikes at the very heart of who you are, constantly. It can be bliss or hell. Or both at once. Business skills may get you a fantastic weaning schedule, but they won’t help you sing ‘baa, baa black sheep’ in exactly the right, sleep-inducing key.

- You’re either a stay-at-home mum or you work. For many of us, working life changes dramatically after we have children (most commonly, after we have a second child). Some of us find ways to become freelance. Some go back to the office part-time. Some set up our own projects with more flexible hours. Many of us simply work harder and longer at odd times of the day, to compensate for time spent with our children. It is rarely simple. I’ve lost count of the amount of telephone interviews I’ve done while jiggling a baby/breastfeeding/trying to ignore the howls of my children beating each other up in the other room.

- I won’t need postpartum help. You will (see below, page).

- I will fall in love with my baby the minute I see him. Many of us feel alarm, indignation, surprise, indifference, shock or confusion in place of instant maternal love. It can take weeks, months and in some cases more, to fall in love with your baby. None of this will mean you’re not cut out for motherhood.

- Being pregnant was so difficult, being a parent has got to be easier. When pregnant, your child, crucially, is inside you, and therefore its sphere of influence is somewhat limited (though it can seem significant enough). Inside you, your child is unable to fully exert the power of her personality. Other peoples’ babies may have seemed featureless and blob-like to you but your own will be infinitely complex and permanently life-altering.

How long does postpartum last?

Everyone has a different answer to this one and you may experience postpartum differently with each child you have. Julia says hers, with Keaton, lasted three months – one month of which was ‘intense’. With Larson, who is now over two and has never been a good sleeper, she wonders ‘am I still postpartum?’ Most women say that dealing with a newborn gets distinctly easier when you all pass the three-month mark, hence the notion of the first three months with your newborn being ‘the fourth trimester’. There is a medical term – ‘puerperium’ – the period usually described as six to eight weeks after childbirth, where your womb and other organs and structures which have been affected by the pregnancy are returning to their non-pregnant state. At the very least, take this period seriously: you have a genuine physiological (not to mention psychological) need to recover.

It can take a while for your baby to start feeding and sleeping more predictably (colicky or fussy babies tend to get mercifully better when they’re about 12 weeks old). In this chapter we’re concentrating on the immediate postpartum: the first three months of your baby’s life. This time – when you’re establishing yourself as a mother (or a mother of two, or more) and getting to know your beautiful baby – can be bliss. If you prepare for them.

Where to go for help:

Find out more online about babymoons from www.activebirthcentre.com.

Getting help postpartum

Rest and how to achieve it

The number one rule for a productive postpartum is simple: take rest very, very seriously. Stress and tiredness are implicated in anything from mastitis to postnatal depression. But in order to rest you’ll need plenty of help (even – indeed possibly especially – if this is not your first baby). Whether it’s a team of highly-paid nannies, or merely regular packages of your mother-in-law’s baked goods, you should plan – in advance – how you’ll get the help you need.

TIPS FOR EVERY POSTPARTUM WOMAN

- Put your pyjamas on and stay in them for at least three days (and preferably more) after you get home from hospital. You can’t dash around town in your jimmies. Take no pride in being up and about: it’s not going to do you or your baby any good.

- Avoid walking up stairs for three days if you can. ‘You have a wound inside you where your placenta was so help yourself heal it,’ says midwife Kim Kelly. Let others bring your food to you, and keep your baby with you for the whole three days. It’s a cliché, but this is time you’ll never get back.

- Cook and freeze lots of healthy meals that you actually like (borrow a friend’s freezer space if you don’t have a freezer, or consider buying one if you can possibly do so – they are invaluable for feeding babies and children in a remotely healthy way).

- Create a six-week support plan so you can rest, and not become overwhelmed by your new situation (see The Skeeter Effect below).

- Include your other children in your postpartum – get them to hold the baby, touch her, count her toes, change her nappy. And get help with them, so that you are not left feeling guilty/overstretched/overwhelmed.

Options for postpartum support

POSTNATAL MATERNITY NURSE | The idea is that they satisfy the worries and concerns of the new mother. They can cost a fortune (about £600 a week, via an agency). You hire one for the first week or two following the birth to help you establish breastfeeding schedules, and to give you confidence and tips for dealing with your newborn, and to let you rest. People normally book one for at least two weeks. They can be lovely, or bossy, or both. But most will have their own very fixed, and sometimes rigid, system for dealing with a new baby that can, for some mothers, feel overpowering. They’ll expect to live in.

NIGHT NANNY | Again, a posh option for those who are really obsessed by sleep. Can also be a lifesaver if you have twins (or more) or a sick baby. Night nannies will normally look after the baby in your house from 9 p.m. to 7 a.m. They cost around £70 per night. If you are breastfeeding, they will bring the baby to your room for feeds and take her away afterwards, doing all the jiggling and nappy changing while you crash out.

POSTNATAL DOULA | Trained to help you cope brilliantly with the early days, her main agenda is to help you bond with your baby, and not feel over-stressed. She’ll do anything from advise you about feeding, nappies or newborn sleep patterns, to nipping round the supermarket for supplies. They usually charge between £10 to £15 per hour and probably ask for a deposit. They’re not just for first time mothers. A friend of mine, who has three children, hired one when she had her fourth and fifth babies: twins.

‘MOTHER’S HELPS’ | Terrible term, but a catch-all for teenage girls to whom you and your partner can ruthlessly pay a pittance in exchange for basic help around the house – washing up, laundry, hoovering, jiggling baby’s pram, changing the odd nappy, answering the front door. Remember, though, that teenage girls can be fickle (i.e. they may not show up). And they should not be expected to behave like nannies (i.e. look after your baby for long periods unattended).

FAMILY/FRIENDS | Consider getting a family member to come and stay after the birth with the explicit purpose of helping. But be clear about what you may need them to do: cook dinner? Clean the kitchen floor? Look after your other child/children? Just hold the baby while you sleep? Some people say tension with family members became significantly better with the arrival of a nappy-clad mutual distraction. Others say it all exacerbated an already inflammatory situation. Only you can judge how your particular family psychodrama might play out but the golden rule is: if they’re not helping, tell them (tactfully if you can) to go away. And have a back up plan.

Some common family pitfalls

Close family members are ideal postpartum helpers. But think hard before you commit. Many women think the baby will heal rifts, help them bond with estranged parents or siblings, even ‘change’ people. Maybe it will, in the long run, but the first few weeks postpartum are not the time for family therapy. So:

- BEWARE THEIR EXPECTATIONS | ‘My mum came expecting fun and joy,’ says Len, 34, mother of Liam (1), ‘and got stress – I was ill and her grandson was colicky. It was a BIG mistake having her come so soon – she was anxious, and it made us even more stressed. Next time I would have her there, but I’d talk to her about exactly the kind of help we’ll need, before she comes.’

- BEWARE CHANGES IN PARENTING | It’s been years since your parents had a newborn on their hands. Ideas may have changed. It’s your turn to make your own mistakes, and if they can’t recognise this, it’s probably worth a conversation early on, as things will only get worse.

- BEWARE THE BAGGAGE | Julia has seen many idealistic clients: ‘One client, when I asked her about her postpartum plan, said her mother would be flying in to help. I asked if they got on well and there was a pause before she said, “Well, she’s a practising alcoholic and that’s been really hard on our relationship, but I think this will really bring us together.” Eventually, after much discussion, she invited her mother to come out when the baby was a bit bigger.’ Use your judgment about how helpful your family will actually be: it’s a bit like when you chose your birth partner – loving that person isn’t a good enough reason in itself to invite them to stay during the precious early days of your baby’s life.

Tip for organising postpartum help:

The ‘Skeeter Effect’ is a system Julia suggests her clients use to organise a support network of friends in the first few weeks (Skeeter was her baby son’s nickname). You just get several of your friends to agree to take one or two days of each week to check on you. In the first week after your baby’s birth they bring you a meal on their day (they just make two dinners in that first week – one for their own family and one for you). After that first week, they agree to phone you on their chosen day for at least six weeks more. This way, you won’t feel isolated or alone (at least you’ll get a phone call a day). This can also be a good way to spot symptoms of postnatal depression. Julia has had clients’ friends calling her weeks after a birth to tell her they’ve noticed symptoms of postnatal depression in the new mother.

A WORD ABOUT VISITS | These can be overwhelming in the immediate postpartum, especially if they all expect you to make them tea and feed them cake (or worse, real food). Do not try and pretend you’re normal. Get them to make their own tea and bring cake with them. Set particular times for their visits and tell them how long to stay. If they offer to help, or bring food, say yes without hesitation or guilt.

Releasing your helpers

Once you have accepted help it’s important to find a reasonable time to let go of it. Julia has seen some clients over-use their poor friends and relatives. ‘For most of us, who are healthy and have healthy babies, the ‘crisis’ period postpartum, where we really need urgent help, lasts two or three weeks (this is not to say we don’t need help after this, just not so much, or so intensely). Eventually, you’ve got to work out how to cook and get laundry done. That’s not postpartum. That’s life with kids.’

When to venture out

In some parts of India, twenty-two days of rest after birth is the common practice. Women are served and pampered, able to recover and adjust to motherhood in their own time. Until relatively recently, even British women had a long ‘lying-in’ period (sometimes months). These days, however, you’re meant to be scooting round Sainsbury’s within days of popping that baby out. For first time parents, just leaving the house with a newborn can be daunting, and if you’ve got other children, going out in the early days can become a major (and majorly stressful) event. You might feel, first time around, like everyone is watching you to see whether you’re incompetent. You might be terrified in case your baby cries at the checkout or poos on her babygro (she probably will). You might wonder how you’ll carry a tantrumming toddler and a baby in a car seat, while wheeling a trolley across a busy car park (answer: a trolley with infant seat AND toddler seat, grim determination, thick skin and lots of patience).

TAKE OUTINGS ONE STEP AT A TIME

- Don’t feel you have to go out if you feel you want to stay in and rest. There is no right time.

- A walk, with your baby in the sling or buggy, is a good first outing.

- Make your outing – whatever it is – short.

- Get your partner or friend to come too.

- Be aware that your baby is not used to noise, bright lights, odd smells. The outside world, the first few times, can be pretty alarming for them too. Crying is pretty normal for a first buggy trip.

- Be aware that if you have other children, particularly if they are small, they may play up simply because they’re not used to your attention being divided.

Your body postpartum

‘Try not to worry at this stage, that you feel a bit as though someone has implanted a bunch of miniature bananas into your vagina: a bruised vulva is part and parcel of a normal delivery, and no-one gets away without some discomfort.’ Journalist Joanna Moorhead in an article in Junior Pregnancy and Baby magazine1.

What’s the fuss about?

Nobody tells you what postpartum can feel like. But one of the most common things women we spoke to for this book said about postpartum was: ‘no one told me it’d be like this.’ This is a diary I wrote, for a newspaper, when my second postpartum was fresh in my mind. Look at it as a cautionary tale: I had been totally focused on having a good birth and had NOT prepared for the after-effects of a vaginal birth. I therefore had no idea what to do about them. I was living far from home and family, in Seattle, and had very little help or support. You, of course, will manage your postpartum MUCH better than I did. This diary isn’t meant to scare you, but here you go: I’m telling you how it can be if you are not prepared for it.

DIARY OF A POSTPARTUM WOMAN

Zero hour

Having heard many friends liken childbirth to melon-pooing, I beg to differ. It is more like completing a triathlon while simultaneously attempting to turn oneself inside out, labia first. Improbably my beautiful baby is finally born. A flood of utter relief, helped massively by a rush of endorphins.

20 minutes

Euphoria. I am distracted by sight, feel, smell of beautiful, salty, messy baby. I need stitches and the midwife calls for an obstetrician who, she claims, is a ‘devil with a needle’. Having endured childbirth you’d think a few little stitches with an anaesthetic would be a piece of cake but they’re quite sore. I focus on my astonishing baby boy who is now snuggled against my chest. Everyone is congratulating me. I feel like I’ve achieved a miracle. And so I have.

45 minutes

The midwife wants to tell me all about my ‘tear’ and is slightly taken aback that I don’t want the details. She takes my husband outside to debrief him. When she comes back (John with a ‘bright smile’), she says she should put a catheter in as it might be a ‘bit sore’ to pee. I consume handfuls of painkillers in anticipation of the local anaesthetic wearing off. Tip: ‘Your right to know everything includes your right to NOT know everything,’ says Julia. ‘You can always ask your midwife later if you decide that you want to know the nitty-gritty after all.’ (Also, with a straightforward vaginal birth like this one, a catheter is uncommon in the UK, and definitely optional – it’s usually better for you to go to the loo on your own. You can ask to have your first pee in a bed pan if you don’t want to get up.)

One hour

Warm, flooding feeling in the bed. I ring the bell in a panic, but it’s just the catheter bag, ‘malfunctioning’. My stomach is still vast, as if another baby is lurking in there. The midwife explains that it takes six weeks for my womb to shrink back to normal size. She prods it regularly over the next two days to see that it is doing this and to check that there are no signs that I have retained any of the placenta or have any infection.

Six hours

Still haven’t dared get up as I’m feeling distinctly bruised. Fortunately, my baby is a great distraction: he is alert, and beautiful, and gazes up at me with huge eyes and I spend a lot more time gazing joyfully back at him than I do worrying about the state of my vagina. Even though this is my second child, it still seems genuinely astounding that I’ve given birth to this fantastic baby boy.

Seven hours

Catheter is removed and I am guided to the bathroom to ‘get cleaned up’. My legs shake and ache. My head is light. I have the distinct impression that my intestines and colon are going to fall out of my vagina. But, I am still euphoric at having produced an actual, healthy baby so – astoundingly – none of this matters. Afterwards, I put on a pad and a pair of paper knickers. They have small pink sprigs on them, a nice touch. Tip: Bleeding is painless and normal after childbirth. Peeing in the shower or the birth tub in those first hours after the birth may not be ladylike, but will make that first pee much less of an ordeal. Alternatively, ask the midwife to bring you a jug of warm water and when you sit on the loo, pour it over your parts as you have your first pee.

Day one

I have to recline since sitting is painful. I refuse to look down there and also refuse to let my husband look as I don’t want him to retain any negative image. He thinks I’m mad, as he saw Sam come out. My stomach is still inflated. My shoulders, oddly, ache as if I’ve carried a piano around for several days. My breasts are producing pale liquid called colostrum that Sam laps up round the clock but other than this they don’t feel any different. I have been given ‘stool softener’ pills but apparently may not be able to ‘go’ for quite some time. Tip for inevitable constipation: soak 1–2 teaspoons of linseeds or psyllium seeds in a cup of warm water, leave to swell into a gel for 15 minutes, drink at night. Or soak same amount of linseeds overnight and add to breakfast cereal. Take any stool softeners you are offered.

Day two

I am still having painful ‘contractions’. This is my womb shrinking and shouldn’t persist. Walking out of the hospital is a challenge. I have to stick my bum out and take tiny steps like ancient tribal dancer. I look pregnant still. I am unable to sit down in the car and have to perch, one cheek on the side of the seat, swearing. But I feel triumphant: bringing my family home. Tip: Afterpains are worse with your second, and subsequent babies. Take plenty of paracetamol and try lying on your tummy. If it’s painful to sit on your bruised perineum, you can hire a ‘valley cushion’ from the National Childbirth Trust (see Find Out More) designed specially for comfort after birth.

Day three

I now see the need for stool softener and can confirm it has failed. I am genuinely alarmed by my piles. My perineum still aches when I move, and it hurts to sit down. My boobs have inflated to the size and texture of medicine balls, my nipples are bright red and I keep crying. (‘Baby Blues’, I am told by a sympathetic midwife; a normal hormonal day-three thing – my oestrogen and progesterone levels have ‘dropped precipitously’.) Tip: Keep up with the linseeds for constipation and drink plenty of fluids. Baby blues are normal and should pass within a day or two. Bathe your piles in cotton wool soaked in witchhazel, which you keep in the fridge. You can also use over-the-counter haemorrhoid cream. Use sore vagina/perineum/stitches methods we’ve outlined on page. For ways to cope with engorged breasts, see page.

Day four

My husband insists on taking a look at my parts. I am sure he’ll never desire me again, but right now couldn’t care less. He claims – to my astonishment – that they look almost normal. I know he is lying because when I move I can feel the wind whistling up there and things flapping. Also, the midwife told me she put in purple stitches. Love is a wonderful thing. Sam is feeding constantly, and my milk supply feels good. His two-year-old sister holds him on her lap, and John and I look at them both and feel, suddenly, like a ‘real family’.

Week two

Still incontinent, still huge. Sam eats round the clock (what happened to ‘four hourly schedules?’). My boobs feel variously engorged and completely drained. And I now have a suspicious red, painful lump on one breast. A day later, the whole side of it is red and inflamed. I have a fever. Midwife diagnoses mastitis – an infection of the milk ducts – and prescribes rest (ha), steaming them over a pan of hot water, massage and antibiotics. Tip: There are many ways to treat sore nipples, lumps and other breastfeeding difficulties (see page). In the vast majority of cases these things happen because your baby is not latched on properly. Get advice straight away from a breastfeeding specialist (ask your midwife for details of the hospital breastfeeding clinic) if any problem emerges. N.B. Many women at two weeks postpartum feel fantastic: their stitches have healed, breastfeeding is established, their help and support are really working for them and they begin to feel human again!

Week three

The mastitis has gone, I can still feel the bruising on my perineum if I’m up and about too much, but am now much more mobile than before. Sam is sleeping more, and my mother has arrived, so for the first time I am able to just sit and marvel over him (while my mum takes my two-year-old out for treats). Tip: Gentle postpartum yoga moves and stretches will help to increase your energy, manage stress and heal faster.

Week six

My book talks about ‘easing back into sex’. Ha, ha. One of the tips is ‘don’t be discouraged by pain’ Tip: Some women feel sexy surprisingly early (sort out your contraception!), others find that, with the recovery from the birth, and with hormones released from breastfeeding (not to mention interrupted sleep) it’s months – and often up to a couple of years even – until they feel sexy again. The general advice is: take sex at your own pace, don’t feel pressure to be sexy and – if you do – go gently at first.

Week seven

Fretful baby and very little sleep. I have been told that Sam’s elephantine wind problem could be a result of dairy produce in my diet and so have cut it out, which is not helping my stress levels. He is still farting and writhing. My health visitor gives me a questionnaire to check whether I have postnatal depression. Apparently not. My mood is, she says, ‘normal’. Tip: Tiredness often catches up on you surprisingly late, and can make you feel down. This is usually also when you are alone with the baby more. Join local groups, even if you’re not a ‘joiner’, as being with other new mothers can be your salvation. If you’re worried about postnatal depression talk to your midwife or health visitor (who should be checking you for this anyway). Many babies have settled well by seven or eight weeks, and are sleeping more and feeding more regularly. If yours is very ‘windy’ see a breastfeeding specialist to check that you are latching him onto your breast properly, before you start to alter your diet. I took Ted, my third (equally windy and fretful) baby to the breastfeeding clinic at my hospital when he was six weeks old. They explained that I was latching him onto my breast in an inefficient way when feeding him. Doing it correctly turned him into a different baby overnight: peaceful, non-windy, content. This might not work with a genuinely colicky baby, who can be extremely exhausting (see page). Most fretful (and even colicky) babies have settled down by 12 weeks postpartum so remind yourself this will pass and GET SUPPORT.

Week eight

Life is looking up. The piles have almost gone. I can now walk for half an hour without discomfort. I slept for three consecutive hours two nights in a row and I managed faintly to twitch my pelvic floor yesterday. I’m still exhausted and feel fat. But my baby smiles now as well as farts and his sister claims she loves him, even though she’s cross with me, and wants to hold him all the time. I think they’re the most beautiful human beings in the world. Which makes it all worthwhile.

Immediate postpartum

Your vagina

If you gave birth vaginally then let’s face it your faithful friend has been through the mill (particularly if it is your first time). It needs tender loving care to recover properly, not stoic, gritted teeth. One rule: put nothing in your vagina for three weeks after the birth – no tampons or (god forbid) penises or vibrators. If and when you do begin to have sex, you might want to use a lubricant at first (e.g. KY gel from any chemist) as your hormones may make your vagina less lubricated for a while (and it may still be tender).

TRICKS FOR SOOTHING SORE BITS

Try the following until you find something that works for you

- Frozen peas: put them in a ziplock plastic bag, wrap in a thin towel or pillowcase and put them on the sore area. They mould well to the shape of your body and can feel hugely comforting. You can also buy slightly pricey ‘gel pads’ from Boots that are specifically for postpartum use on your perineum – same effect (though quadruple the cost) as the peas.

- Squirty bottles: many women have several days of perineal/labial pain while peeing after giving birth. Ordinary little plastic bottles with squirty tops (a bit like small washing up liquid bottles) are commonly handed out to new mothers in American hospitals. You can buy their equivalent plastic bottles with squirty tips in Boots, marketed to store your cosmetics in when you are on holiday. Alternatively, on your first trips to the loo after birth, go armed with a jug of warm (not hot) water and pour it on your labia/perineum as you pee. The water will dilute the acidity of your urine and massively reduce the stinging feeling.

- Cold maxi pads (get cottony feel ones): sprinkle your sanitary pad with cool witchhazel from the fridge. Witchhazel is soothing and antiseptic. Change your pads very frequently. Keep pads in the freezer and use them cold to soothe and reduce swelling.

- Gentle drying techniques: never rub your vulva dry: always just pat it very, very gently.

- A ‘sitzbath’: this is a small tub that you fill with warm water and put on the loo, or sides of the bath, so you can bathe your parts in it (a washing up basin will do at a pinch). It can be immensely soothing – and quick to do – after a vaginal birth. (Ordinary baths work too, but are more time-consuming and harder to get regularly when you have a newborn.) Some midwives suggest adding a few drops of lavender essential oil (dilute it in a couple of tablespoons of milk so it does not just sit on top of the water). Herbalists say some herbs are good for soaking your bum. Buy all of this before the baby is born. If you have a bidet, this will do as well.

- A ‘valley cushion’: A special cushion designed to help you sit more comfortably while your perineum is bruised or stitches are healing. You can hire these from the NCT (see Find Out More). They are now recommended by midwives instead of the old ‘ring’ shaped cushions.

Bleeding

Expect to bleed for a few days as if you’re having an excessively heavy period – you might pass some large clots – then as if you have a normal period, for a month or so after the birth, getting gradually lighter as the days pass. This is normal. It also happens after a caesarean. It’s called ‘lochia’ and it’s your womb shedding its lining. It’s why you initially might want disposable knickers (available from Mothercare, Boots and large supermarkets like Tesco and Sainsbury’s – in the baby aisle usually) and to buy in crate loads of sanitary pads before the birth (see Appendix). An alternative to disposable knickers is to wear old or cheapo knickers you can bin. You’ll need to buy a lot of the thickest sanitary pads for wearing at first; later on, they can be reduced down as the bleeding slows.

Tip: Put an old towel under your sheet to protect your mattress.

Afterpains

These are period-like cramps you get after the birth (for about a week) as your womb begins to shrink back to its normal size. They’ll be stronger if this is not your first baby – your womb has to work even harder this time to regain its pre-pregnancy shape and size. They can be more intense while you breastfeed, because of our old friend, the hormone oxytocin: this is responsible for the letdown of your milk and also causes your womb to contract. How to cope: try massaging your lower abdomen, lying on your stomach with a firm pillow under it, putting a hot water bottle on it. Take the maximum dose of paracetamol in the first few days. Tip: If you have a TENS machine (see Chapter 5), you might want to keep hold of it for a few days after the birth as it can be good for afterpains.

Incontinence

I know. But it happens to the best of us. I remember peeing myself as I walked upstairs to the loo about a week after giving birth – totally unable to control the flow. I felt like a distraught old lady. No one had told me incontinence could be a temporary side-effect of giving birth. Do your pelvic floor exercises as soon as you can bear it (or sooner). At first you may feel absolutely nothing. Again, no one ever tells you this and it can be immensely frustrating. But keep doing it and gradually you’ll regain some control. It’s essential to do pelvic floor exercises regularly (see Chapter One, for instructions) to minimise future incontinence, improve your sex life and avoid other problems with your nethers as you get older. If your incontinence remains problematic, discuss it with your midwife. It’s incredibly common after childbirth and so many of us don’t mention it. She can help you sort it out with special exercises and refer you to a physiotherapist if this does not work (in some cases it won’t, and you will need extra help but in the long run, you should be fine). It’s normal to leak a little bit of pee when you cough or sneeze, for up to a year after the birth.

Experienced mother’s pelvic floor tip:

If you’re mentally prepared for dodgy bladder control, and know it won’t last (if you do pelvic floor exercises), it’s perfectly manageable: use sanitary pads, even when you stop bleeding as this takes the anxiety away a bit.

Your bottom

Yes, just as your progeny’s poo can be a source of concern, so can your own. At least in the first few days postpartum. Constipation is common, can be eye-wateringly painful and is caused by your changing hormones. Ways to cope: try linseed as in the tip on page. Drink eight glasses of water a day and make sure you are eating fibre rich food (wholegrains, fruit and veg – hard to do in the first few days, but try or you’ll be trying harder on the loo). Take any remedy or ‘stool softener’ your midwife suggests (usually lactulose or fibrogel). Another glamorous after-effect is piles (haemorrhoids). These can be shockingly pronounced after birth. Ways to cope: bathe your bottom with cotton wool soaked in witchhazel, apply over-the-counter medications and use wet wipes to wipe for a bit. And talk to your midwife: some suggest raising your bottom above heart level with cushions at night (helps the piles go back in!). Your midwife will not be in the least surprised by the conversation. Indeed, she may be wondering why you haven’t already raised the issue.

Experienced mother’s bottom tip:

‘My birth ball, after I’d delivered, turned into the most comfortable chair in my house for a while.’ Jo, 38, mother of Lucinda (4 months)

Your belly

The first thing you may notice is that you still look six months pregnant. This is because your womb has only just started shrinking. The next thing you’ll notice is that your stomach has metamorphosed into a large squishy sponge (in texture and appearance). Stay calm. It will (particularly if you exercise later) firm up again. The sponge effect, even if you do no exercise, is short lived (how short lived will depend on anything from your genes to your pregnant size).

Your breastfeeding boobs

The other day I looked down at Ted – now a big, chubby, healthy four-month-old baby – and it occurred to me that he has been fed on nothing but me since he was a small bundle of multiplying cells. This is quite an achievement, when you think about it. Breastfeeding is a miraculous extension of pregnancy: your boobs, which have spent their whole life propping up your wonderbra (or whatever) finally get to show what they’re made of: they’ll produce milk that will feed a real baby. But like all achievements, this can involve some effort and determination. The best preparation for breastfeeding is mental: get information. There’s tons of research to show that breastfeeding is incredibly beneficial for your baby and for you, but it isn’t always easy. If you are prepared for this, and informed, you can tackle any problems that arise and go on to feed your baby for as long as you want. The best thing a midwife ever said to me was: ‘Breastfeeding may be natural, but it isn’t instinctive.’ You have to learn. Start by reading our Breastfeeding basics.

YOUR BOOBS IF YOU ARE NOT BREASTFEEDING | If for some very rare reason you are physically unable to breastfeed, then your boobs may feel normal after the birth. However, if you are choosing not to breastfeed, they can become engorged with milk for up to a week or so. How to cope: do not stimulate your breasts at all, take paracetamol regularly, use breast pads for leakage. A warm flannel or hot water bottle may also help soothe non-breastfeeding boobs.

Your skin

You may sweat a lot in the first few days after giving birth, especially at night. This is your body getting rid of the extra fluid it has amassed during pregnancy. The look of your skin might change too: in pregnancy you may have noticed increased pigmentation (‘cholasma’, sometimes called the ‘mask of pregnancy’) and maybe even hair growth on your face. These, you’ll be relieved to learn, should go away postpartum.

But when it comes to postpartum skin, most of us are more worried about stretch-marks than sweating. If your smooth tummy has turned into a crumpled page of red scribbles it’s easy to feel dismayed. The books will tell you they’re feminine badges of motherhood – great in theory but not enough if you’re shocked by yours. The good news is that almost all stretch marks will fade and become far less noticeable over time (though this can take months). You can’t get rid of them, but you can buy sexy one-piece swimsuits to replace your outdated bikinis, know that you are most definitely not alone and – yes – cultivate a ‘don’t care’ attitude.

Sweaty nights tip:

Sleep on a towel so you don’t make endless laundry for yourself.

Your hair

Hair becomes thicker in pregnancy then falls out, sometimes alarmingly, afterwards. This is normal. Your hair actually falls out all the time when you are not pregnant: you just don’t notice it. During pregnancy, your hormones simply slow this natural falling out routine. This makes your hair seem really luxuriant. Many of us rush to the hairdresser as soon as possible after the baby is born, desperate to feel more glamorous (unlike the rest of your body, hair is something you can control, at least superficially). It can, therefore, be a bit of a downer when your hair starts falling out. But fall out is normal. You are not going bald – merely returning to your usual follicular state.

Your smell

It is fine to have a bath any time after you’ve delivered your baby (the view that you should only have showers until your blood flow has dried up is very outdated). Watch out for hot baths in the hours after the birth though, says midwife Jenny Smith: ‘Most women are usually exhausted after labour and there’s a danger of fainting if you have a hot bath.’ Not getting time to bath or shower once you’ve left the hospital, on the other hand, is one of the things many women find hard in the early weeks. Particularly first time around, we’re terrified to leave our baby unattended for even ten minutes. But if your baby is sleeping in his cot/Moses basket somewhere safe (and you know where your cat/other children are) you can just take the baby monitor to the shower with you. Don’t panic if your baby wakes up and howls for a few minutes while you’re rushing to dry your tender bottom. He is safe (you’d hear on the monitor if some predator appeared in his bedroom). He may be cross. But he’s fine. You are not a neglectful parent. Another tip is to make an agreement with your partner (or pay a teenager to come for an hour) for a set time each day when he’ll watch the baby while you shower or soak in the bath. It can be nice to know that you are, just for that short period, not going to be interrupted. Tip: wear earplugs while you bathe, or earphones. Yes really. This way, you won’t leap out guiltily at the first wail.

Experienced mother’s tip:

‘I just let mine cry, if necessary, safely in the bouncy chair next to the shower,’ says, Manju, 38, mother of three. ‘It’s stressful, but effective. I was determined to start my day with a shower. I got clean and I knew the baby was not being tortured by the other children. I look back on my first baby – when I virtually never had a proper shower – and wonder why I didn’t just let him yell for a minute or two.’

Your teeth

Pregnancy can affect your teeth so try and get to the dentist reasonably soon postpartum. If you are lucky enough to have an NHS dentist, you get free dentistry throughout pregnancy and for a year after the birth. But take your partner. You don’t want to be wrestling with your howling newborn while gagging on a tamp. If you’re breastfeeding tell the dentist before they start any work on you (anaesthesia and drugs can pass through the breast milk).

Your body image

Julia believes that it’s important for women’s psychological health not to turn into unwashed, uncared for beasts postpartum. Obviously, if you were such a beast in the first place, then motherhood doesn’t mean you have to slip into heels, lippy and a bright Stepfordian smile. The real issue, of course, is more complex than a bit of lippy might suggest. Your body has been through something extreme and somehow not entirely reasonable. You may feel like a huge, spongy, mildly psychotic milch cow for a while and this is fine. I remember walking up a very steep hill in Seattle with John (who had our tiny son in a sling and was pushing our two-year-old in the buggy). We were both out of breath (me more than him) but unlike him, my thighs were wobbling, my perineum was aching, my boobs were throbbing, my waistband pinching. And I suddenly felt wildly jealous that he was so unencumbered. It’s not easy, at times, to adjust to your postpartum body. But it will change. ‘I remember the glee I felt when out for a country walk some time after my second baby was born,’ says Linda, 48, mother of two teenagers. ‘I realised I could just hop over a fence. It was a profoundly liberating moment.’ The postpartum rebound effect: it will happen.

Your weight

Childbirth educator Sheila Kitzinger once wrote that many women love pregnancy because it’s the first time it’s socially acceptable not to be skinny. But when the pregnancy is done, the ‘too fat’ pressure descends once more. You will, unless you’ve been starving yourself in a stupid way during pregnancy, be somewhat over your ideal weight after you have had a baby. Some women don’t mind this one bit, others find it depressing. You’ll lose weight rapidly in the first few days after delivery because you will pee out the extra two to eight litres of water your body carried in late pregnancy. But after this things may slow down somewhat.

‘I tell women not to expect to be back to normal for at least a year,’ says midwife Jenny Smith, ‘this way, you are off the hook. I see some women who become so thin so fast after the birth it just isn’t healthy. You should be enjoying your baby, not worrying about what you eat.’

WEIGHT ADVICE FOR SENSIBLE WOMEN

- Do not diet if you are breastfeeding: weight loss after pregnancy will be gradual (remember the old adage: ‘nine months on/nine months off’).

- Eat well: good nutrition is essential postpartum to stop your body’s natural resources, such as your calcium supply, from becoming depleted in the long term. Plan frequent, healthy snacks if you are breastfeeding, to keep your energy levels up.

- Do gentle postnatal exercises: as advised by your midwife or health visitor in the weeks after the birth. They will help you get back in shape.

- Breastfeed: it can help you lose weight (it burns calories).

This is all technically correct. But many of us are not so well-balanced. We worry that we’ll never lose the baby weight. We feel depressed when we catch sight of our bellies and bottoms in a shop window, or when we can’t fit into clothes three times our normal size. We get grumpy when our partners tell us we look lovely when we feel fat. We try to restrict our eating even though we know we shouldn’t. And because we’re knackered from dealing with, not to mention feeding, a small infant, we then crack and eat all the wrong things at the wrong times. We don’t cook curly kale because we’re too tired and haven’t got to the shops anyway. Instead, we eat frozen pizza and hobnobs, then worry that our bums will forever reach the backs of our knees.

WEIGHT ADVICE FOR THE REST OF US

- Let yourself of the hook, for God’s sake. You’ve just produced a baby. Prepare yourself for weight loss being slow, and for this being ok and totally normal.

- Do not go on a fad diet when breastfeeding. Really. Just don’t. Your breastfeeding body needs balanced nutrients for long-term health, not a carb-free, food combining, cabbage soup extravaganza.

- Don’t weigh yourself for three months – at least – after the birth. It won’t help and it will probably just depress you. Put away the scales.

- Don’t exist solely on Marks and Sparks ready meals if you can possibly help it. Freeze batches of healthy food, like vegetable soup, in individual portions, before your baby is born. Defrost them for three minute lunches. Boring, perhaps, but effective.

- Make it easy to lay your hands on a healthy snack. Planning snacks probably isn’t going to be your top priority but there are easier ways to cut back on cake than willpower alone. Buy more fruit and fewer hobnobs. If fruit isn’t enough, eat toast and marmite with low fat spread; a (preferably wholemeal) hot crossed bun, a granary roll with cheese or a handful of nuts. Put dried fruit on your shopping list, and remove crisps.

- Have the odd treat. For crying out loud, you deserve it.

- While breastfeeding uses up calories (about 500 a day) many of us don’t lose any weight while doing it, because we stuff ourselves with cake (see above) and don’t get enough exercise (or we’re simply more hungry all the time: who can blame us?). Even if you are not an exercise person, try walking with the baby in a buggy for 30 minutes a day, five days a week, once your midwife or health visitor says it is OK to do this.

- Dress like a non-pregnant person. If you can afford it, take a trip to some super cheap clothing shop like Matalan, or a Hennes or TopShop sale. Buy a couple of pairs of trousers and some tops or dresses that you can give away as you shrink out of them. Many of us feel significantly more human in something without stretchy panels. A stretchy black dress can also be a versatile godsend.

- Hide your jeans. Store away your old jeans in a distant cupboard and do not touch them (or even look at them) for at least six months, if not a year. I remember, about three months after Izzie was born, attempting to get into my ‘fat’ jeans. I couldn’t even get them over my knees. I whipped them off, assuming I’d mistakenly picked out my ‘skinny’ pair instead, and had to sit down when I saw they were, indeed, my most capacious denims. Expect a few instances like this and keep a sense of humour.

PHYSICAL WARNING SIGNS POSTPARTUM

Call the doctor/midwife if you experience any of these symptoms postpartum:

- Passage of a blood clot larger than a lemon. Heavy bleeding that soaks a maxi sanitary pad in an hour

- Fever of 100.4F/38C or higher on two occasions

- Problems when you pee: burning, or blood in pee, inability to pee

- Very foul fish-like smell to vaginal discharge (this can signal infection)

- Pain at site of episiotomy or tear or redness and pain on your caesarean scar

- Swollen, red, hot painful area on the leg, especially the calf (can signal blood clot – a huge emergency – so call immediately).

- Sore, reddened, hot, painful area on breast, along with fever or flu-like symptoms (this could be mastitis, see page).

Your mind postpartum

Your body is oddly shaped and surging with hormones, you’ve had less sleep than you thought physically possible and you’ve fallen in love. These things can affect your mental state. Here are a few common worries and what to do about them.

Anxiety taking the baby home

It’s surprisingly easy to become institutionalised in hospital, comforted by those lovely midwives with their understanding smiles, advice and sympathy, their safe medications and the doctors on hand; the regular (if revolting) feeds you get, the routine, the noise, the smell. It’s like being a small child again – everyone else is in charge.

Putting on clothes, strapping your defenceless infant into a car seat that suddenly seems the size of the Titanic, and walking out of the door can feel terrifying. The whole world swells dangerously around you: how will you keep this small creature alive? Safe?

Going home – particularly with your first baby – can be a tremendously vulnerable time. Most of us feel like this – it’s normal, and says nothing about your ability to cope, but don’t underestimate its power to freak you out. Remember, the midwife is coming tomorrow. And there is always one at the end of a phone.

Tiredness

The physical act of giving birth would be enough to send most of us to bed for a month. When you factor in a wakeful newborn, the tiredness can feel catastrophic. Don’t think that if you’re the kind of person used to working lunatic hours in the office you’ll breeze through sleep deprivation as you’ve always done. Baby tiredness – the hormonal, physical, emotional blend – is a different kind entirely. The only thing you can do about it is REST. For this, given that a small creature is waking you up night and day, you will need help.

Sleep deprivation: mental preparation tip:

Julia knows how acute sleep deprivation can be hard to handle: ‘Don’t assume that you’ll be tired for a little while then all will be normal. Just as you planned for a long labour and hoped for a short one, plan for a baby who doesn’t sleep (and hope for one who does). I treated Larson’s bad sleeping as a temporary thing: I just kept going like it would end soon. We had 18 months of not more than four hours sleep a night and it was so hard: on us, on our work, on our four-year-old and hardest on our marriage. If I had to do it again, we would have taken naps, hired childcare for our eldest and made a point of getting out regularly without the kids, instead of ignoring the effects of this sleep deprivation, and hoping it would end soon.’

Baby blues

On or around days three to five after the birth, it is normal to start feeling weepy, depressed, desperate or helpless (about 50 to 80 per cent of new mothers experience this). Midwives spend a lot of time reassuring new mothers who’ve hit the day three blues. It is, however, a normal mood response to a rapid drop in your hormone levels after birth, and the hormonal changes as your milk supply begins. What you need most is support and reassurance. Baby blues should fade away after a couple of days.

WHEN IT’S WORSE THAN THIS: HOW TO SPOT POSTNATAL DEPRESSION (PND)

Ten to 15 per cent of new mothers develop PND at some point in the year after their baby is born. This is a treatable illness, but it’s called the ‘silent epidemic’ because it’s so often left unspoken, sometimes with catastrophic consequences (one to two per cent of new mothers develop a severe illness called ‘postpartum psychosis’). No one really knows why such illness affects some women more than others (there is some evidence that it can run in families) but if it happens to you get help.

PND warning signs

You may have symptoms of the baby blues AND

you may have any combination of these symptoms:

- despondency and hopelessness

- feeling exhausted all the time

- being unable to concentrate

- feeling guilt/inadequacy

- anxiety, feeling unable to cope

- feeling uninterested in the baby

- feeling hyper-concerned about the baby

- obsessive thoughts

- panic

- fear of harming yourself or your baby

- headaches/chest pains

- not caring about your appearance

- sleeplessness (even when the baby is not waking you)

Severe PND (or postpartum psychosis) warning signs

The above symptoms plus you may also:

- not want to eat

- seem confused

- have severe mood swings

- feel hopeless or ashamed

- talk about suicide/hurting the baby

- seem hyperactive or manic

- talk quickly or incoherently

- act suspiciously or fearful of everything

- have delusions of hallucinations

Spotting PND tip:

PND can happen late in postpartum (up to a year after your baby is born). This means it might not be recognised as a postpartum illness. The medication used may be different for women with PND than for women with general kinds of depression. If your depression isn’t acknowledged as PND, you can go on suffering for years on the wrong treatment. If you think you (or someone you know) may have PND, treatment from a specialist is essential.

Where to go for help:

Write down your symptoms. Talk to your health visitor and your GP (if possible, take your partner with you). And try:

Association for Post-Natal Illness (APNI) 145 Dawes Road London SW6 7EB Helpline: 0207386 0868 www.apni.org

Further reading:

Coping with Postnatal Depression by Fiona Marshall (Sheldon Press, UK, 1993)

Antenatal and Postnatal Depression by Siobhan Curham (Vermilion, UK, 1999)

Online:

What is PND? www.rcpsych.ac.uk/public/help/pndep/postnatd.htm

BBC PND page www.bbc.co.uk/education/health/parenting/yoblues.shtml

Piecing together the birth

Postpartum is a good time to sort through what happened at the birth. If your birth was difficult, and you feel upset, now is the time to get help. Many women find it’s best start piecing together what happened by writing it down (do this even if your birth went well – it might help you plan your next birth, if there is one). Who did what? Who said what? How long did various stages take? How did it feel? Emotionally and physically? What shocked you? What didn’t? What was amazing? Then sit down with your midwife and birth partner(s) to fill in the gaps and get explanations.

Your baby

Your baby may seem like a frighteningly complex (if stunningly beautiful) being comprised of strange noises, smells, emissions and moods. In your addled state there are a few key things worth knowing about. Detailed baby care is beyond the scope of this book so find out the rest from trial and error, your baby, your midwife, your health visitor, friends, family and the legion of child-rearing books and websites out there.

FOUR THINGS TO DO BEFORE YOUR BABY IS BORN

- Get excited: birth is just the beginning. Parenting is the biggie.

- Arrange help and support: you’re going to need some.

- Decide how you’ll feed your baby: if you are to breastfeed, make sure you have read about it first (see page) and know where to go for help as you are learning.

- Buy a good medical ‘new baby’ book: so you can look up things that worry you as they crop up. Understand what professional support (i.e. health visitor/midwife/GP) is available to you.

Real mother’s tip:

‘Buy a few photo albums before the baby is born. If you have them handy then early photos won’t go missing or get drooled on. You’ll be glad you did this later on!’ Kate, 50, mother of 3 teenage boys

A WORD ABOUT YOUR HEALTH VISITOR | I certainly didn’t understand, with my first baby, what the health visitor was for. I’ve now discovered, with my third, that they can be a good source of ideas, support and information. Health visitors are nurses or midwives who have been specially trained (in child health and health promotion) to help you adjust to being a parent, and to cope with the hiccups and worries you experience: medical or not. You’ll bring your baby to see your health visitor for regular weigh-ins, checkups and immunisations (often at a weekly ‘baby clinic’ attached to the GP’S surgery). Your health visitor should visit you when your baby is about 11 days old (they will ring you – your midwife will have told them about your new baby. If you don’t hear from a health visitor in the first ten days, ask your midwife why not). Don’t hesitate to phone your health visitor for advice if anything is worrying you, or go to the baby clinic, even if your baby isn’t ‘due’ a check-up. That is what they’re there for. (But remember they may not have the detailed expertise of a breastfeeding specialist, so if your problem is breastfeeding related, get specialist help.)

Baby basics: a few things new babies do that can be worrying

- CRYING | Newborn babies may be very peaceful and sleepy for the first few days. It’s like they lull you into a false sense of security and then let loose the guns of war around days three to five. Often this coincides helpfully with your partner’s return to work. There are many supposedly ‘logical’ approaches to decoding a baby’s cries: indeed some bright spark – a Spanish engineer – has actually invented a machine that diagnoses the reason for a baby’s cry, which says something for our faith in maternal/paternal instinct. You’ll be advised to go through a little checklist: Wet? Stinky? Hungry? Hot? Cold? In pain? Uncomfortable? Just needs a cuddle? But sometimes the baby just seems to want to cry (old ladies will tell you ‘he’s exercising his lungs, dear’). Baby books or online baby guides can be helpful, as can other mothers for tips on things like baby massage, but largely it’ll be up to you to get to know what your baby wants. Most parents will tell you that the most helpful thing of all, when it comes to a crying baby, is to remember that the baby WILL STOP. Eventually. He will not cry forever (even if he tried to he’d be scuppered by growing up).

How to cope with your baby’s wailing: This doesn’t mean you should grin and bear it if your baby’s crying is upsetting you badly. If she seems uncomfortable a lot after feeding (tucking her legs up, yelling, writhing), get advice from a breastfeeding specialist about your feeding technique (see Breastfeeding basics). If your baby is not unwell, but just keeps crying all the time, this may be colic. Colic can be genuinely traumatic – for all of you.

A WORD ABOUT COLIC | Colic is a term used to describe the inconsolable crying/screaming and apparent tummy pain of an otherwise healthy young baby (up to about six months). The reasons for this are unclear, but in some infants painful gut contractions might be at least partly to blame. Many babies are fussy, but a colicky baby is one who cries like this for long periods (hours, even), most days of the week. The symptoms usually start when the baby is around three weeks old (though can start later). It is worst at about six weeks and usually ends when the baby is around three months old.

Where to go for help:

Talk to your midwife and health visitor who should give you advice and tips for coping.

Serene incorporating The Cry-Sis Helpline Serene provides support and non-medical advice to parents/carers of excessively crying, sleepless and demanding babies and young children. BM CRY-SIS, London WC1N 3XX. 020 7404 5011 (this is the national switchboard, they match you up with a local contact who can talk to you). www.cry-sis.org.uk

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) www.nspcc.org.uk/html/home/needadvice/copingwithcryingbabies.htm NSPCC Publications Unit, 42 Curtain Rd, EC2A 3NH. 020 7386 0868 has free information about dealing with crying babies, stress, and general coping with parenting issues. And if you’ve reached the end of your tether or just want someone to talk to about this, call the NSPCC Child Protection Helpline: 0808 800 5000 (you won’t be judged!)

Further reading:

The Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Newborn Baby Sleep Longer by Harvey Karp (Bantam, US, 2003)

365 Ways To Calm Your Crying Baby by Julian Orenstein (Adams Media Corporation, US, 1998) Written by an American paediatrician, this has lots of ideas, particularly relevant to the first three months.

2. SLEEPING (NOT) | Expect little sleep. Your baby will feed about every two hours in the first few weeks, even possibly this much at night. Again, remember that this period WILL PASS. The books all tell you that new babies sleep 16 to 19 hours a day, but what they don’t tell you is that most of the time they’ll want to sleep on – or right next to – you. Even if your baby will sleep in her bed, allowing you to achieve more than one-handed tasks, resist the temptation to get things done the minute she nods off. You, too, need to nap as much as you can because if you don’t, you will go nuts in those first few weeks.

A WORD ABOUT COT DEATH | What is it? Cot death is the sudden and unexpected death of a baby for no obvious reason and it’s what many of us worry about a lot in those early months. You’ll hear about it because it is the leading cause of death in babies over one month old. According to the Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths (FSID) ‘Cot death can happen to any family, though it is more frequent in families who live in difficult circumstances or who smoke a lot. It is uncommon in Asian families, for reasons that are not yet understood.’ According to the latest statistics from FSID, 89 per cent of all sudden infant deaths in England and Wales occurred among babies aged under six months. But mercifully, these days cot death is rare: it has fallen in the UK by 75 per cent since the introduction of the government’s Reduce the Risk of Cot Death campaign in 1991. So take this advice seriously:

What can you do to prevent it? FSID’S new advice to parents on reducing the risk of cot death is:

- Cut smoking in pregnancy – fathers too!

- Do not let anyone smoke in the same room as your baby

- Place your baby on the back to sleep

- Do not let your baby get too hot

- Keep baby’s head uncovered – place your baby with their feet to the foot of the cot, to prevent wriggling down under the covers

It’s safest to sleep your baby in a cot in your bedroom for the first six months (see UNICEF below).

It’s dangerous to share a bed with your baby if you or your partner:

- are smokers (no matter where or when you smoke)

- have been drinking alcohol

- take medication or drugs that make you drowsy

- feel very tired

- if the baby is less than eight weeks old

- It’s very dangerous to sleep together on a sofa, armchair or settee.

- If your baby is unwell, seek medical advice promptly.

Where to go for help:

UNICEF advice on bed-sharing There is on-going debate about the risks and benefits of sharing a bed with your baby. Where your baby should sleep is certainly something you should research for yourself. Start here. www.babyfriendly.org.uk/press.asp#160104

Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths, Artillery House, 11–19 Artillery Row, London SW1P 1RT. 020 7233 2090. 24 hour helpline: 0870 7870554. www.sids.org.uk/fsid

Further reading:

Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child: A Step-by-step Programme for a Good Night’s Sleep Marc Weissbluth (Vermilion, UK, 2005)

Newborn breathing tip:

Most babies don’t have a very steady breathing pattern, and may gasp a bit from time to time. Lots of new parents think their baby has asthma or some other breathing problem, when she’s actually perfectly healthy. Talk to your midwife or health visitor if your baby’s breathing is worrying you. ‘Try not to obsess on your baby’s breathing, it can sound really odd at times. I did a lot of panicking and now realise he was fine – healthy colour, no sign of pain or distress. I just got myself into a cycle of worry.’ Angela, 35, mother to Eric (8) and Jack (3)

3. POOING | It’s no idle cliché: mothers do, indeed, care deeply about their child’s poos – from day one. Poo will be a large part of your life for the next two years at the very least. The good news is that you’ll be broken in gently to the world of nappies and bottom wiping – newborn poos are surprisingly manageable, and always far less revolting than you’d think.

A WORD ABOUT YOUR BABY’S POO | Your new baby will, in the first day or two, do a meconium poo that looks like tar (it’s a very sticky black/brown maybe greenish tablespoon or so – though it might be more – and is totally normal). Breastfed babies may then start doing non-stinky mustard-coloured, liquidy poos. How much and how regularly your baby poos is one way to see if she is getting enough food but it can vary massively from baby to baby. My first emitted an almost constant stream, my second and third could go for three or four days or more without a single one. Formula-fed baby poo can be more stinky, browner and heavier and your baby might be more windy and more likely to be constipated. Sometimes a baby’s poo will be greenish and stinky. This can be a sign of slight illness or a reaction to something you ate, if you are breastfeeding. Diarrhoea is when the frequency of poos increases suddenly and they are more watery: more than eight very watery and copious poos in 24 hours counts as severe diarrhoea. Again, if you are worried at all about what’s normal, do phone your health visitor.

Bottom wiping tip:

It is probably best to use only cotton wool and warm water to wipe your baby’s bottom in the early weeks. You might want to use unperfumed baby wipes later as they make things easier, but you can of course keep using cotton wool. Baby wipes – and indeed other baby bath products/lotions – can contain some quite harsh ingredients that can irritate a baby’s skin. Always wipe your girl from front to back (i.e. vagina to bottom) to reduce the risk of a urine infection.

4. CHANGING COLOUR | Most babies are a greyish blue colour at birth (even black babies, which can be unsettling if you aren’t prepared for this) but within just a few breaths they turn a more normal colour. New babies can still look oddly coloured for a while – very red, blotchy, lighter or darker than you’d think. They can also turn very bright colours when cross (red, puce, purple). In the first 24 to 48 hours, sticky secretions that your baby has swallowed during the birth can occasionally get stuck in his throat, making him choke and sometimes turn blue. If this happens, advises neonatologist Eleri Adams, put him over your knee, face down and give him a firm slap between the shoulders. You might need to repeat this to clear his airway, but if this doesn’t work, call for help immediately.

A new baby’s skin can peel or seem very dry. It can also be spotty: you might see small white spots (noticeably on the face). These are hormonal, healthy and may take several weeks to clear. What’s not healthy: If you see your new baby’s skin turning yellowish, it could be jaundice. See Chapter 7, for more details.

A WORD ON THE UMBILICAL CORD STUMP | You’ll get instructions on this from the midwife. It will look black and crusty, and you’ll probably think ‘that can’t be right’ – ask if you’re worried. Usually the advice is just keep it clean but basically leave it alone and be careful when bathing/dressing your baby. It normally just drops off within about ten days.

NEWBORN WARNING SIGNS

Paediatrician’s tip: ‘Doctors tend to worry more about a very quiet baby who doesn’t seem quite right than they do about a noisy one,’ says consultant neonatologist Eleri Adams. If you see any of these signs in your newborn you should get medical help.

Call the doctor urgently/call ambulance:

- Problems breathing: blue lips, struggling to breathe, flaring nostrils, deep indentations of the chest when breathing, unable to finish feeds because breathless or sweating when feeding.

- Excessively or uncharacteristically fussy or irritable; unusually lethargic or sleepy; feeding poorly/differently; crying in a high-pitched way.

Call the doctor to see soon:

- Fever higher than 100.4 F/38 C rectally or above 99.50F/37.0C under the arm

- Vomiting: forcefully or more frequently than usual (not just spitting-up)

- Repeatedly refuses feeds for more than six to eight hours

- Diarrhoea: unusually frequent and very watery poos; blood or mucus in poos

Talk to the midwife:

- Dry nappy for six to eight hours, or fewer than five wet nappies in 24 hours (after your milk has come in); dry mouth; dark yellow urine; sunken fontanel – the soft part on the top of your baby’s skull, where the bones have not yet joined together. (Call the doctor to see soon if this is combined with significant diarrhoea or vomiting: see above.)

- Shows signs of jaundice (unless under 24 hours old, or is very sleepy and not feeding, in which case, call urgently).

- Doesn’t pass a greenish-black poo (meconium) within 24 hours of the birth. Most babies (94 per cent) will pass meconium within 24 hours of being born. But two to four per cent of normal babies don’t pass meconium by 48 hours. If your baby has not passed meconium after about 24 hours, then do mention this to the midwife. If, however, your baby is vomiting, or has a very distended tummy and has not passed meconium, then talk to the doctor/midwife immediately.

- Problems with the umbilical cord: redness around the cord, foul odour or pus, bright red bleeding

Breastfeeding basics

TEN GOOD REASONS TO BREASTFEED

- Breast milk is the healthiest food for your baby: it provides everything your baby needs for the first six months.

- Breastfeeding reduces your baby’s risk of developing gastroenteritis, respiratory, urinary tract and ear infections, eczema and childhood diabetes. There is some evidence to associate breastfeeding with a lower risk of developing childhood leukemia.

- Breastfeeding is healthier for you too: you will have a lower risk of premenopausal breast cancer and ovarian cancer and, later in life, of hip fractures.

- Breast milk is always available, requires no equipment and is instantly at the right temperature.

- It’s free (breastfeeding rather than formula feeding saves you an estimated £450 a year).

- Breastfeeding is good for your baby’s neurological development. Studies have found that breastfed infants test higher on IQ tests than bottle fed infants.

- Breastfed babies are less likely to be obese as adults, and to suffer from cardiovascular disease.

- Breast milk burns up to 500 calories a day, so it can help you lose weight.

- Breastfeeding saves the NHS money: the NHS spends an estimated £35 million a year treating gastroenteritis in bottle-fed babies in England alone.

- Breast milk is ecofriendly: it’s organic, and comes without unnecessary packaging or waste.

How does it work?

It’s a great system. When the baby is born your breasts produce their first food: colostrum. This is usually thick and yellowish and there is not much of it, but it’s packed with nutrients and will protect your baby from all sorts of infections, so feed your baby as often as he wants in the first day or two (you may feel like he’s permanently attached to your breast in those first couple of days). The hormone that is responsible for producing milk is called prolactin. Prolactin can’t work until the hormones from the placenta have gone from your bloodstream – usually one to four days after the birth. The prolactin then tells the cells in your breasts to start making milk: this is when they can feel full, tight or ‘engorged’.

Your baby’s sucking then sends messages to the pituitary gland, in your brain, which triggers the release of another hormone, oxytocin. Oxytocin (which your body produced when you had contractions in labour) makes the muscular walls of the milk-producing cells contract. This contraction ejects the milk down the duct and out through your nipple into your baby’s delighted mouth. This is what they call ‘supply and demand’.

A WORD ABOUT EXPECTATIONS | As with birth, the textbook version may not be the reality for you. A huge part of breastfeeding success is trusting that your body will do it, even if your breasts do not seem to be doing what ‘most’ breasts are supposed to do. When I had Izzie, I was told that on day three after the birth my boobs would swell and gush ‘real’ milk to feed her. I was in the hospital for five days after my caesarean. The patient midwives showed me various positions for feeding and gave me a breast pump to try and ‘get things going’. I waited with a growing sense of hysteria and inadequacy for the ‘engorgement’ to happen but it never did. This didn’t mean I couldn’t breastfeed but it caused me unnecessary angst (my confidence in my body, after the birth, was at an all time low anyway). My milk ‘came in’ slowly of its own accord and not very noticeably. This happened with all my babies. The lesson here is that if your breasts don’t follow the textbook pattern at any point there is no reason to assume they are not doing perfectly well. (There is, incidentally, some evidence to show that having a caesarean can delay your milk coming in, so this experience is actually quite common among caesarean mothers.)

Is breastfeeding easy?

Breastfeeding can certainly be marvellously simple: no sterilising bottles, no fuss, no expense. For many women, it’s a happy, healthy, unproblematic experience. It can also be deeply fulfilling: breastfeeding your baby really does create a unique bond. But when you are a learner it can be a painful, frustrating and very tiring. ‘Breastfeeding doesn’t come naturally in our bottle-feeding culture: it is a learnt social skill,’ says midwife and breastfeeding specialist Sally Inch. ‘The reason many women have problems breastfeeding is that they are not given the opportunity to learn that skill.’ If you get support from breastfeeding professionals, you should be able to sort out any problems and go on to feed your baby for as long as you want (the current advice is to breastfeed for a minimum of six months if possible).

Many of us – perhaps because we’re not expecting it to be a challenge, or don’t know how to get support (or get the wrong advice when we do ask for help) – give up breastfeeding way sooner than we want to. Although 69 per cent of mothers in the UK initially breastfeed, a fifth (21 per cent) of these give up within the first two weeks and over a third (36 per cent) give up within the first six weeks of their baby’s life. By four months only 28 per cent of all mothers in the UK are breastfeeding and by six months this has gone down to 21 per cent. Ninety per cent of mothers who gave up breastfeeding within six weeks of birth say they would have liked to have breastfed for longer.2 The key thing to do, then, if you are having any problem with breastfeeding – no matter how seemingly insignificant – is GET HELP from a breastfeeding specialist. By far the best place to start is by asking your midwife before your baby is born if there is a breastfeeding clinic or an infant feeding specialist at your hospital.

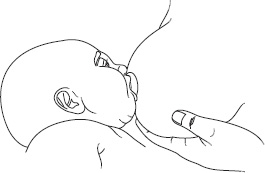

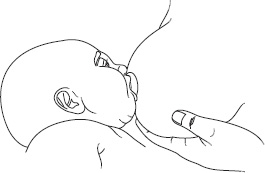

Breastfeeding basics

It’s hard to overstate this: latching the baby onto your breast properly is crucial to breastfeeding success. A poor latch-on is responsible for the vast bulk of problems you might encounter. The reality for many of us is that the first few days of breastfeeding can be painful (usually because of sore nipples). But as you learn to latch your baby on right, any pain will stop and your baby will have satisfying feeds that contain both foremilk (the watery first part of the feed) and hindmilk (the richer second part of a feed). If you get the latch-on right, don’t restrict the time he can stay on your breast, and offer a second breast when he comes off the first (he may refuse), then your baby should automatically get the right amount of food and it should NOT hurt.

If you are in pain or discomfort, if you develop any of the problems below, if your baby is not gaining enough weight, or is colicky or windy then a dodgy latch-on could well be the cause. You need to get an infant feeding specialist to sit and watch you latch your baby on. Sometimes what you are doing wrong is incredibly subtle and no matter how much you’ve scrutinised the diagrams, you might not be able to work out what the missing link is. An infant feeding specialist will. (Not all midwives or health visitors are as up to date on breastfeeding as they’d like to be. This is why it’s the specialist you need to see.)