Figure 5.1. The lead ship models from Naxos now in the Ashmolean Museum (third millennium B.C.) (from AJA 71 [1967] pl. 3 [Renfrew])

Early Ships of the Aegean

Aegean geography, with its many islands, numerous small natural harbors, and rugged topography, required early on that the cultures inhabiting its rocky shores develop seafaring skills, which were ingrained into their cultural heritage. Fortunately for us, the Aegean region, unlike some of the geographical areas discussed earlier, is exceptionally rich in iconographic materials depicting seagoing ships.1

The Archaeological Evidence

The earliest evidence for seafaring in the Aegean—and in the entire Mediterranean, for that matter—is flakes of obsidian originating on the island of Melos that were found in the strata of the Franchthi Cave, located in the southern Argolid.2 These indicate that the inhabitants of the Greek mainland had the technical skills required to navigate the Aegean by the Upper Paleolithic or Mesolithic periods. Unfortunately, we know nothing about the craft in use at that time.3

Navigational skills, however, did not translate into patterns of settlement. Only later, after the introduction of agriculture in the Neolithic period, which allowed the immigrants to exploit islands with sparse resources, did settlement of the Aegean islands begin.4 There is mounting evidence for Late Neolithic settlement on various Aegean islands and for the founding of Crete in the late eighth or early seventh millennium B.C., apparently as the result of a well-organized and concerted effort.5 The Early Bronze Age, however, experienced the main thrust of Aegean settlement.

The Iconographic Evidence

Iconographic information on Aegean seafaring begins only in the third millennium. Thus, the period separating the earliest evidence for seafaring from the earliest iconographic representations of seagoing craft is considerably longer than that separating our own time from the Early Bronze Age. Two distinct types of ships can be defined during this period. The first is a variety of seagoing longship; the other seems to be a fairly small vessel with a cutwater bow and stern. Other types of craft may have existed, but if so, we have no known depictions of them.

Early Bronze Age Aegean Longships

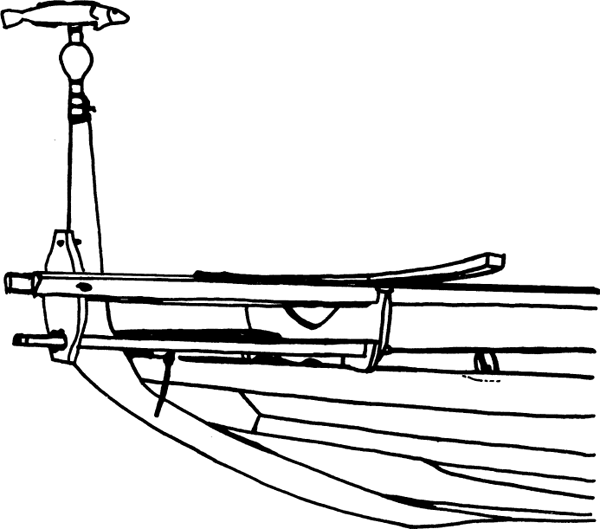

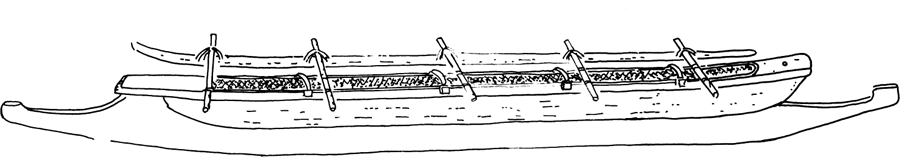

LEAD MODELS FROM NAXOS. As might be expected from the preceding discussion, the earliest iconographic evidence for ships in the Aegean already shows considerable structural development. The clearest indication for the shape of these longships is three lead ship models from Naxos that date to the third millennium B.C. (Figs. 5.1–2).6 Each of the models is constructed of three lengths of lead. The bow and keel are made from a rod of lead that was flattened by hammering the central two-thirds of its length to form a flat bottom. Two other flat strips form the sides of the hull. One extremity is raised and finishes in a vertical transom, while the other end is narrow and rises at an angle. The models are exceptionally narrow; the largest and best preserved has a beam/length ratio of 1:14. L. Casson believes these to be models of dugouts; L. Basch considers their prototypes to have been planked ships.7 The largest model is reported to have been discovered in a tomb together with two stone idols.8

Figure 5.1. The lead ship models from Naxos now in the Ashmolean Museum (third millennium B.C.) (from AJA 71 [1967] pl. 3 [Renfrew])

CYCLADIC “FRYING PANS.” Perhaps the best-known examples of this ship type appear on an unusual group of third millennium terra-cotta artifacts that have been termed generically as “frying pans” because of their odd shape (Fig. 5.3).9 Frying pans appear throughout a wide area, including mainland Greece and Anatolia, but it is the group from the Cycladic island of Syros, found in the context of the Keros-Syros culture, that has created the most interest for studying ancient seafaring, as only its members bear depictions of ships (Figs. 5.3–4).10

The one thing that seems clear about these particular artifacts is that they were probably never intended for use as frying pans. The purpose for which they were made remains enigmatic.11 The frying pans may have had a cultic or ritual function. This seems to be supported by the occasional depiction of female genitalia just above the two-pronged variety of handles (legs?) (Fig. 5.5).12 These sometimes have a leafy sprig that later reappears in conjunction with ships and in other, clearly cultic, contexts on Minoan seals (Figs. 6.29: D–E, I, K, 45).

The ships are long and narrow in profile. They obviously depict the same type of ship after which the lead models from Naxos are patterned. One extremity ends in a high post that forms an almost right angle with the hull. The post is decorated with a fish device and tassel placed on a pole. The device invariably points away from the craft. The angle at the other end of the ship, already noted on the Naxos models, also appears in varying degrees on the Syros ships.

Ethnographic parallels of fish ornaments are known from the Solomon Islands, where the device was connected to the stem and faced the stern; and the Moluccas, where it was connected to the stern and faced the stem (Figs. 5.6–7).13 Tassels are a more common decorative/cultic emblem; parallels are known from antiquity and recent times (Fig. 5.6).14 The low ends of the ships terminate vertically, apparently ending in a transom-like manner, as on the Naxos models. A horizontal device projects at keel-level abaft the transom.

The short parallel lines on either side of some of the ships are best understood as paddles.15 The ships are too schematic for the number of strokes on a side (up to twenty-eight) to be taken as the exact number in actual use; clearly a good number is implied, however. Two rock graffiti from Naxos, although of lesser quality, depict the same ship type (Fig. 5.8).16 Both have horizontal (fish?) devices atop the high extremity. One ship has a horned (?) quadruped above it.

Figure 5.3. A typical Cycladic “frying pan” decorated with a longship (Early Cycladic II) (photo by the author)

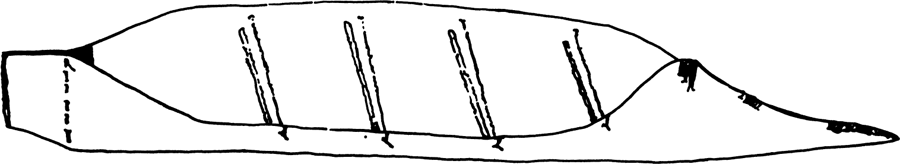

PALAIKASTRO MODEL. A rough terra-cotta model of this ship type, uncovered in an ossuary dating to the Early Minoan I–II period at Palaikastro in eastern Crete, indicates that these ships were also known in Early Bronze Age Crete (Fig. 5.9).17 The model has a teardrop-shaped hull when viewed from above; the same shape is repeated on later models from Christos and Hagia Triada (Fig. 5.10).18 The pointed end of the “teardrop” finishes in a high post. The rounded end is apparently the terra-cotta equivalent of the stern transom on the Naxos models. The widest part of the hull is well astern of amidships.19 A blunt horizontal projection extends abaft the stern.

Figure 5.2. The best preserved of the Naxos lead ship models in the Ashmolean Museum (third millennium) (from AJA 71 [1967] pls. 1:12. [Renfrew])

Figure 5.4. Ships incised on Cycladic “frying pans” (Early Cycladic II) (from Coleman 1985:199 ill. 5)

ORCHOMENOS. Another ship of this sort is incised on an Early Helladic vase handle from Orchomenos (Fig. 5.11). Two vertical lines above the hull are probably accidental scratches and are not related to the craft.20 The line of the keel is slightly longer than the top (sheer) line, forming the familiar horizontal projection. Sixteen short vertical strokes above the sheer are best interpreted as paddles.

PHYLAKOPI. None of the above representations show steering oars. However, the curving stern of a ship with a single steering oar appears on a sherd from Phylakopi (Fig. 5.12). A short tiller (?) extends abaft the steering oar. The stern projection is absent. Rows of parallel lines above and below the hull again apparently depict paddles.

TARXIEN. The longship class seems to have had a particularly wide area of use. Casson identifies a ship of this class on a stone from the megalithic temples of Tarxien on Malta (Fig. 5.13).21 He believes that other graffiti at Tarxien represent merchant craft because of their dumpier proportions.

Figure 5.5. Genitalia appearing on Cycladic “frying pans” (Early Cycladic II) (from Coleman 1985:196 ill. 4)

CHARACTERISTICS OF EARLY BRONZE AGE AEGEAN LONG-SHIPS. It has been suggested that the ships depicted in the various iconographic mediums represent different sizes or even classes of longships.22 Variations of craft probably did exist in the Early Bronze Age Aegean, just as there was a variety of ship types in the Oceanic region in the more recent past. The iconographic evidence, however, is not sufficiently clear to permit such differentiations. Variations may result from their expression in different mediums—incision on clay, metal/stone/terra-cotta models, and so on—which may significantly change the relative dimensions of the illustrations.23

An argument still persists among scholars as to which end of these ships represents the stern and which the bow.24 There are two compelling arguments for identifying the high end as the stem. Firstly, the lower extremity of the Naxos lead models have a blunt, transom-like ending, strongly suggesting that this end was the stern. Secondly, the ships taking part in the waterborne procession depicted in the miniature frieze at Thera have similar horizontal projections at their sterns (Figs. 6.13–14). This device, unknown outside the Aegean, is so unusual that one may assume it represents the same device in both the Early Bronze Age depictions and at Thera. Given this consideration, it seems highly unlikely that the horizontal stern projection—whatever its function—would have been transferred from one end of the ship to the other.25

Figure 5.7. Stern of prahu belang, Moluccas (after Horridge 1978: 43 fig. 31: A)

Depictions of the Aegean Early Bronze Age longships suggest the following general conclusions:

• The ships are extremely long and narrow and may have descended from monoxylons.26

• The high stems were topped on occasion by fish devices and tassels.

• The Cycladic frying pans may be connected with fertility and regeneration.27 The appearance of ships on these objects also argues for a relationship between the actual ships and the cult.

• Usually—but not in all cases—the stern ends in a horizontal projection at keel level. The craft was finished astern in a transom or was blunt-ended.

• As we have seen in the Byblos archetypes, terra-cotta models have a tendency to shorten the length of ship models to a greater degree than the other dimensions. Therefore, it seems likely that the lead models from Naxos approximate most closely the dimensions of the original craft. If so, these craft would have made a poor showing in high seas: because of their elongated, extremely narrow dimensions, they would tend to hog. The zigzag lines on two of the Cycladic ships may indicate either some type of decoration, additional strengthening, or perhaps that the ships were lashed (Fig. 5.4).28

Perhaps the closest modern ethnological parallel to these Aegean ships is the long, narrow “dragon boats” of the Far East (Figs. 5.14–15).29 Their beam/length ratio varies between 1:10 and 1:14, thus agreeing with the Naxos models.

Like the Aegean longships, dragon boats are seagoing craft that are manned by rows of paddlers and have no sail. Crews range in size from twenty to one hundred men, depending on the vessel’s length, which can vary from twelve to thirty meters. These vessels are definitely seagoing, although because of their long and narrow proportions and lack of internal structure, they tend to hog in even a moderate sea. To prevent this, bamboo hawsers, or on occasion a true hogging truss, are employed (Fig. 5.15:B). C. W. Bishop notes one example of a true hogging truss that ran the length of the hull over its center.

Although today dragon boats are used only for ceremonial purposes, in the recent past these vessels had far more somber functions. They are recorded from the third century A.D. onward used in war and piracy.30 These boats continued to be used by brigands and water police on the south China coast into the nineteenth century. Imperialist forces used them against the Taiping rebels in “Chinese” Gordon’s time, and Burmese ships of similar type were used by opponents of the British.

If the comparison between the dragon boats and the Aegean Early Bronze Age longships is legitimate, it would seem that the Aegean longships were suited primarily for acts of war and ceremony.31 They were certainly not functionally fitted to be used as merchant craft. Perhaps other ship varieties were used specifically for trading; if so, nowhere have they been revealed in the iconographic evidence of the Aegean Early Bronze Age.32

• The large numbers of lines and the narrow beam indicate that these craft must have been paddled. There would have been too little inboard room to permit a rower to work his oars. Ethnological parallels of similar long and narrow craft are invariably paddled, not rowed (Fig. 5.15: A).33

• C. Broodbank, in discussing the longboat’s role, notes that in all but a handful of large sites, the size and social structure of settlements of the Keros-Syros culture were ill-suited to the sort of communal organization required for longboat usage.34 The evidence suggests that the use of a sole longboat would not only have been beyond the manpower resources of a single settlement but may even have been difficult for the population of an entire island to support during the time of the Keros-Syros culture. Based on a calculation of the synchronous population of Melos, Broodbank notes that, assuming a conservative twenty-five–man crew for a longboat, its manning would have required between 30 to 50 percent of the total male labor force on the entire island.

Figure 5.9. Terra-cotta ship model from Palaikastro (third millennium B.C.) (after PM II: 240 fig. 137)

Figure 5.10. Ship model from a tomb at Christos (Messara). End of Early Minoan or beginning of Middle Minoan period (after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 24: 315)

If these calculations are correct, then, at the very least, the use of longships must have been restricted largely by farming activities. The times of agricultural slack during which voyages could be undertaken within the navigation season were limited to two annual periods of about a fortnight each. Broodbank argues that longships from the Cyclades could have visited and returned from most areas of the central and southern Aegean within this time span.35 He believes that their goal would have been primarily to carry out piratical raids, at least in the immediate locality—although longships may have been used for trade over greater distances.

Figure 5.12. Crescentic ship’s stern on a sherd from Phylakopi (Melos) (after Casson 1995A: fig. 46)

Figure 5.13. Graffiti of ships at the “Third Temple” at Tarxien, Malta (from Woolner 1957: 62 fig. 1, 66 fig. 2, 67 fig. 3; reproduced by permission of Antiquity Publications, Ltd.)

Broodbank emphasizes that, because of the demographical considerations, longships must have been rarities in the Keros-Syros culture. He feels that these ships are best understood in the context of Chalandriani and a few other large sites, for only these centers could have supported the construction and use of such vessels. Interestingly, the majority of the thirteen frying pans on which longships are portrayed either were found in Chalandriani or can be linked to that site.

Early Bronze Age Aegean Double-Ended Craft

Only one other kind of watercraft may be differentiated from the longship class in the iconography of the third millennium. The most detailed representation of this boat-type is a double-ended terracotta model from Mochlos (Fig. 5.16). At stem and stern, the model has tholes or frames extending above the sheer. This model is generally considered to represent a relatively small vessel.36 Another terra-cotta fragment from Phylakopi may belong to a similar model.37

Figure 5.14. Model of a Chinese dragon boat in the J. E. Spencer Collection (NTS) (photo by S. Paris; courtesy Texas A&M University)

Double-ended construction with horizontal projections at both extremities may have its roots in monoxylons, skin boats, or bark canoes (Figs. 5.17–22).38 J. Hornell reports a number of types of modern double-ended craft with horizontal projections at both ends in Indonesia, the Philippines, Bali, the Northern Celebes on the islands of Geelvink Bay, New Guinea, Java, Melanesia, Madura, and the island of Aua (Fig. 5.22: A).39 Canoes from the island of Aua in the Bismarck Archipelago, ranging in size from 3.5 to 18 meters, are dugouts in which the bow and stern are prolonged into a very long, thin point and have vertical end-pieces added to the hull (Fig. 5.22: B).40

This double-ended bifid form is characteristic of vessels of varying dimensions, ranging from the smaller types of outrigger canoes to ships of considerable size. Other modern craft have a horizontal projection at only one extremity.41 Cutwater bows were common in Classical antiquity.42

The Phaistos Disk

A terra-cotta disk found at Phaistos and dated to the seventeenth century B.C. has a spiral inscription on both sides.43 The symbols are not related to any known scripts, and the disk itself is believed not to have been of Minoan manufacture.44 This unique artifact carries the imprints of forty-five different seal stones that were impressed into it while it was wet.45 Among the signs is a ship, repeated seven times (Fig. 5.23). At one end the ship has a slanting post with a tripartite decoration.

Although not related, being distant in both time and space, an interesting ethnological parallel to the shape and decoration of the Phaistos Disk ship is found in the Solima canoe, which was used until recently in the Solomon Islands (Fig. 5.6).46 The largest recorded Solima was nearly fourteen meters long and could carry up to ninety men. The Solima had a high stem, which was decorated with a complicated carving of a frigate bird, a fish, and a tassel (Figs. 5.6; 8.60). The tripartite device on the angular stem of the Phaistos Disk ship and on cultic ships appearing in Minoan glyptic art is reminiscent of the feather stern decorations on the Solima (Figs. 6.28 [mast top], 52: A–C). Perhaps the Aegean devices were also made of feathers.

SHIP DEPICTIONS AT AEGINA. A pithos from Kolona on the island of Aegina, dating to the Middle Helladic period, is decorated with crescentic ships. The pithos is very fragmentary, but it is clear that originally it had four ships painted in a frieze on its shoulder. The figures in the ship are bunched closely together and in one fragment are clearly shown facing the bow, indicating that the ships were paddled and not rowed. The high stem ends in an elongated point below a double-curved “stalk” (Fig. 5.24). Vertical stanchions support lances. The best-preserved ship depiction on the pithos originally contained about thirty-one men.47

A matt-painted drawing on Middle Helladic sherds from the island of Aegina depicts a figure wearing a horned helmet standing on a ship’s bow that ends in a bird-head stem ornament (Fig. 5.25). This is the earliest recorded appearance of a bird-head device on an Aegean ship. If they are integral

Figure 5.15. (A) Chinese dragon boat, Yangtze River; (B) deck and sheer plans of a dragon boat, taken off a boat at Itchang; (C) enlargement of the carved dragon’s head in B (from Bishop 1938: pls. 2 fig. 4, 3 figs. 6 and 5; reproduced by permission of Antiquity Publications Ltd.)

Figure 5.18. Canoe, New Hebrides (after Haddon 1937: 32 fig. 19)

to the ship, two parallel vertical lines behind the figure may indicate a pole-mast instead of a bipod one. The horizontal lines above the figure may suggest a yard, but this is questionable since no boom appears, nor do the cross-hatched triangles lend themselves to interpretation as an element of a boom-footed rig.

Figure 5.19. Canoe, Cook Islands (after Hornell 1936: 191 fig. 127)

Figure 5.20. A Kutenai bark canoe (from Hornell 1970: 184 fig. 27 [Water Transport, Cambridge University Press])

Figure 5.21. Bark canoe from Arafura swamps, Australia (after Thomson 1939: 121 fig. 3; courtesy of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland)

ARGOS. Seven tiny craft are depicted on a vase found in a Middle Helladic Argive tomb (Fig. 5.26).48 The ships vary in shape from crescentic to rectilinear. Three of them show a recurving extremity at one end; others show one vertical and one slanting post. All the vessels carry a curved structure (cabin?) in the center. Seven, eight, and ten lines are depicted on the ships. In several cases, one line may represent a quarter rudder.

IOLKOS. Designs on painted sherds from a transitional Middle Late Helladic pot found at Iolkos have been identified as a series of oared craft.49 This reconstruction has been accepted uncritically by some scholars.50 However, there is insufficient evidence to reconstruct these designs as ships.51 G. F. Bass notes that the decoration has been compared convincingly with fish painted on a contemporaneous vase in the Archaeological Museum at Nauplion.52

The longships of the Aegean Early Bronze Age must have been heirs to a long tradition of seafaring in the Aegean. Toward the end of the third millennium, they disappeared from the iconographic record. In their place we find a different ship type that, for the first time in the Aegean, used a sail for propulsion. The scene is now set for a study of Minoan and Cycladic vessels of the Middle and Late Bronze Age, as exemplified by one of the most exciting discoveries of recent times contributing to our understanding of Aegean ships and their uses.

Figure 5.22. (A) An outrigger fishing canoe, bifid at both ends (Menado Celebes); (B) canoe of Aua Island (A after Hornell 1970: 210 fig. 39 [Water Transport, Cambridge University Press]; B after Haddon 1937: 177 fig. 109)

Figure 5.24. (A) Basch’s reconstruction of a crescentic ship on a pithos from Kolona, Aegina, ca. 1700 B.C.; (B)detail of stempost decoration (after Basch 1986: 422 fig. 6, 424 fig, 8: D)

Figure 5.25. Fragment of a ship, with a bird-head device on its stem, painted on sherds from Aegina (Middle Helladic) (after Buchholz and Karageorghis 1973: 301 fig. 869)