CHAPTER 8

The Ships of the Sea Peoples

The Late Bronze Age ended in cataclysmic upheavals caused by mass migrations, at least some of which were seaborne. A variety of ethnic groups emerged that were collectively termed “Sea Peoples” by the literate cultures upon whom they preyed. Appearing first as sea raiders in the fourteenth century B.C., these groups were the Late Bronze Age equivalent of the Huns and the Vikings combined. By the late thirteenth century, their raids had been replaced by full-scale land and sea migrations. The Mycenaeans, the Hittites, and many of the Syro-Canaanite city-states fell before this onslaught, never to recover.

Only Egypt, protected by its peculiar geography and located at the southern end of the advance, was able to repulse the invaders—but at a terrible cost to itself. Ramses III managed to stop the approaching Sea Peoples in two major battles: one on land, the other on water. He claims to have later resettled them as mercenaries on Egypt’s borders. More likely, after being repulsed by Egypt, they took advantage of her weakened position to resettle areas that they themselves had previously ravaged.1 Ramses commemorated these battles graphically on his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu, near modern-day Luxor. His carved relief of the naval battle is an invaluable source of information on a type of vessel used by the Sea Peoples.

Other iconographic sources, mainly rough graffiti and terracotta models, supply additional information about these vessels and suggest that the Sea Peoples’ vessel-type represented at Medinet Habu follows an Aegean tradition. Furthermore, the bird-head finials capping the ships’ ends imply a distinct connection with religious beliefs prevalent in central Europe at the end of the Late Bronze Age and during the Iron Age.

The Textual Evidence

From their first appearance the Sea Peoples, like the Ahhiyawa, were described as raiders or mercenaries.2 In this they followed an age-old Aegean tradition.3

After their settlement on the southern coast of Palestine in the twelfth century, the Sea Peoples appear to have become traders. Nowhere is there absolute proof for this view, but it may be inferred from the following considerations:

• On his outgoing voyage from Egypt, Wenamun’s ship put in at Dor, which belonged to the Sekel/Sikila. Had this Sea Peoples’ group been engaged in brigandage at that time, it is unlikely that the ship would have stopped there.

• In fact, Dor of the Sekel/Sikila appears to have been a “safe haven.” Wenamun had no trouble in presenting his case before Beder, the Sikila prince.4 Indeed, when Wenamun later “liberated” thirty deben of silver from a ship off Tyre, apparently belonging to the Sikila, he was clearly acting outside the law.5

Important information concerning the tactics used by the Sea Peoples in their seagoing ships and the organization of their fleets has been uncovered at Ugarit. There, texts dating to the very last days of Ugarit were found. These documents include maritime aspects of the deteriorating political situation caused by the advance of the Sea Peoples.6 Two of the tablets are of particular interest.

One document is a copy of a dispatch sent by the king of Ugarit to the king of Alashia. In it, the Alashian ruler is informed that cities belonging to Ugarit have been destroyed by a flotilla of seven enemy ships, presumably belonging to a marauding group of Sea Peoples.7 The king of Ugarit includes a request to update him on the enemy’s naval movement. This appeal was acted upon: a dispatch, sent by the chief prefect of Alashia to the king of Ugarit, contains information of enemy movements.8

In another text Ibnadušu, a man of Ugarit, was required to appear before the Hittite king to report on the Sikila (Šikala) from whom he had escaped.9 These Sikila are apparently the same group of Sea Peoples referred to in Egyptian texts as the Tjeker (ṯkrw), as in the Tale of Wenamun, in which they inhabit the coastal site of Dor.10 The Hittite king wishes to interview Ibnadusu concerning the foreign invaders who “live on ships.” This is certainly a fitting description for an ethnic group belonging to the “Sea Peoples.” Also of interest is the abduction of an Ugaritian by the invaders, an event reminiscent of the taking of prisoners that appears in other contemporaneous texts.11

These texts allow several relevant conclusions:

• The number of enemy ships in any given group is relatively small (seven and twenty), particularly when compared to the 150 ships that Ugarit is requested to provide in another text.12

• On occasion, Syro-Canaanite ships were pressed into service in the Sea Peoples’ naval complement. This suggests that the fleets of the Sea Peoples were more polyglot than one would assume from the Medinet Habu relief.

• The tactics used by the Sea Peoples take the form of piratical coastal raids by small flotillas of ships.13 They arrive at a seaside settlement, pillage it, and set it to the torch, disappearing without a trace usually (but not always) before the local military can engage them in a pitched battle.

• Finally, ships used in these raids must have been able to move when necessary under their own propulsion: that means they must have been swift galleys. As the method of attack was based on hit-and-run tactics, these ships could not depend for locomotion solely on the vagaries of the wind.

Questions remain. Where does this event fit into the “micro”-history of Ugarit’s last days as seen through the kiln texts? What relationship, if any, did the Sikila who captured Ibnadusu have to the seven enemy ships that terrorized Ugarit’s coastal cities in RS 20.238? How did Ibnadusu escape from the Sikila? In the general picture that emerges from the encounters of the Sea Peoples with the major, literate Late Bronze Age cultures, there is much that is reminiscent of the emergence and expansion of the Vikings in the ninth to twelfth centuries A.D. The mechanics of the two expansions have similarities. For example, A. E. Christensen notes:

The background of Scandinavian expansion in the Viking Age is complex and not fully explained. Pressure of population at home was considerable, and it is widely accepted that it was chiefly on this account that the Vikings set out on their voyages. A fact that is often overlooked is that a large percentage of the Vikings were peaceful settlers in search of land. The reason for the tactical superiority of those who preferred plunder to tillage, however, is still not clear. Most of the bands were small and often loosely organized. When they met regular Frankish or Anglo-Saxon troops in battle they frequently lost the contest. Nevertheless, the Vikings managed to harass the coasts of Europe profitably for two centuries. Their main assets were the ships and the “commando” tactics these enabled them to use. Appearing “out of the blue,” the shallow-draft vessels would land their crews on any suitable beach to carry out a quick raid and be away before any proper defence could be organized.14

Change only the names, and this same text accurately describes what we know of the Sea Peoples at the close of the Late Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean. There can be no doubt that their swift-oared ships were a major asset in the commando-style tactics used by the Sea Peoples, as were the ships of the Vikings. Probably, like the later Vikings, the Sea Peoples used a variety of ships for different purposes.

The warlike, almost barbarian character of the Sea Peoples as they appear in the textual evidence may be somewhat misleading. N. K. Sandars notes that “there is a sense in which literacy actually distorts the archaeological record, for while it illuminates the centers of civilization, it makes the darkness surrounding even darker.”15 The material culture of the groups of Sea Peoples that settled on the present-day Mediterranean coast of Israel at the end of the Late Bronze Age reveals a very high cultural level that is not apparent from the written record.16 This is hardly surprising, considering the records were written by inhabitants victimized by the Sea Peoples. Again, this is akin to our understanding of the Vikings, who until recently were considered rough barbarians—mainly on the basis of the literary records of the people upon whom they preyed. Now, however, other less warlike aspects of their culture are being revealed, mainly through the archaeological record.

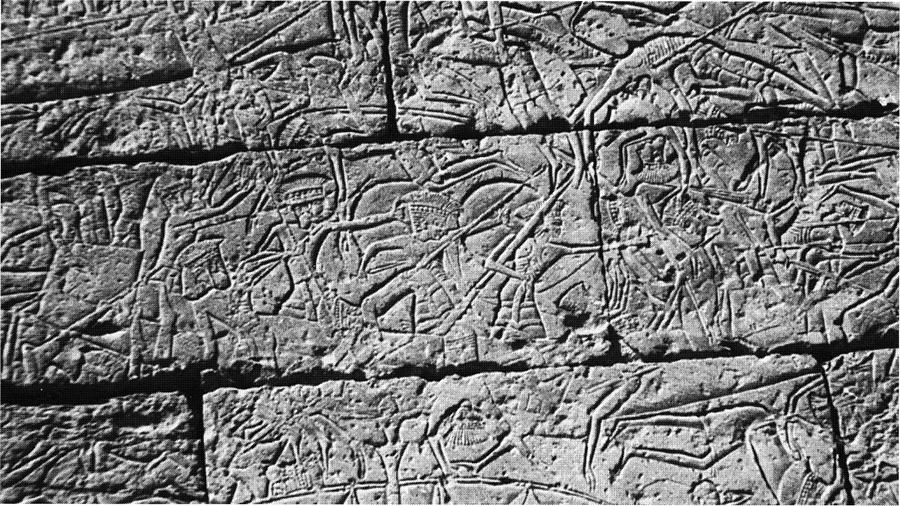

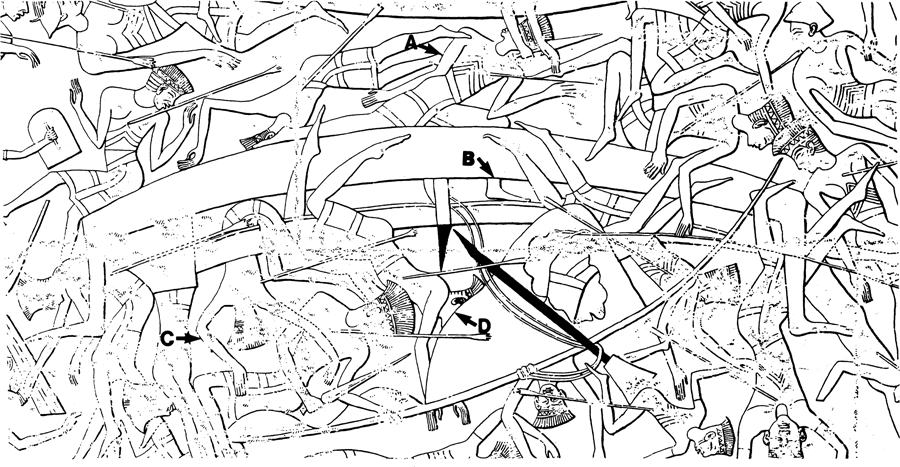

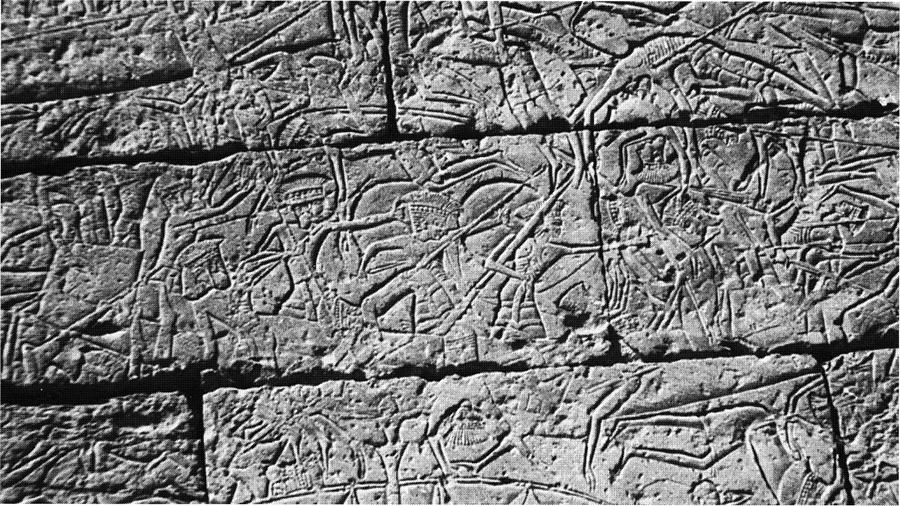

Figure 8.1. The naval battle depicted at Medinet Habu (from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. [H. H. Nelson et al., Medinet Habu I: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III, University of Chicago. Introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930])

Figure 8.2. The scene of the naval battle with the floating bodies removed (from Nelson 1943: fig. 4)

The Archaeological Evidence

The introduction, clearly by sea, of a foreign culture with strong Aegean affinities in Cyprus, along the Israeli coastal plain, as well as at Hama in Syria indicates a major use of ships within the mechanism of this mass migration.17

The Iconographic Evidence

Medinet Habu: The Ships of the Sea Peoples

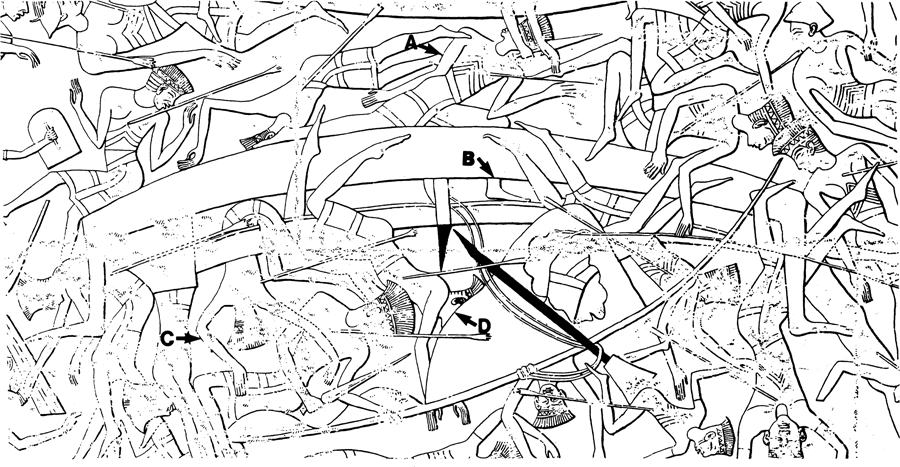

The most important iconographic evidence for the ships used by the Sea Peoples is Ramses III’s relief depicting the naval battle in which he defeated a coalition of Sea Peoples including the Peleshet, Sikila, Denyen, and Sheklesh in his eighth regnal year (ca. 1176 B.C.). The relief appears on the outer wall of his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu (Fig. 8.1).

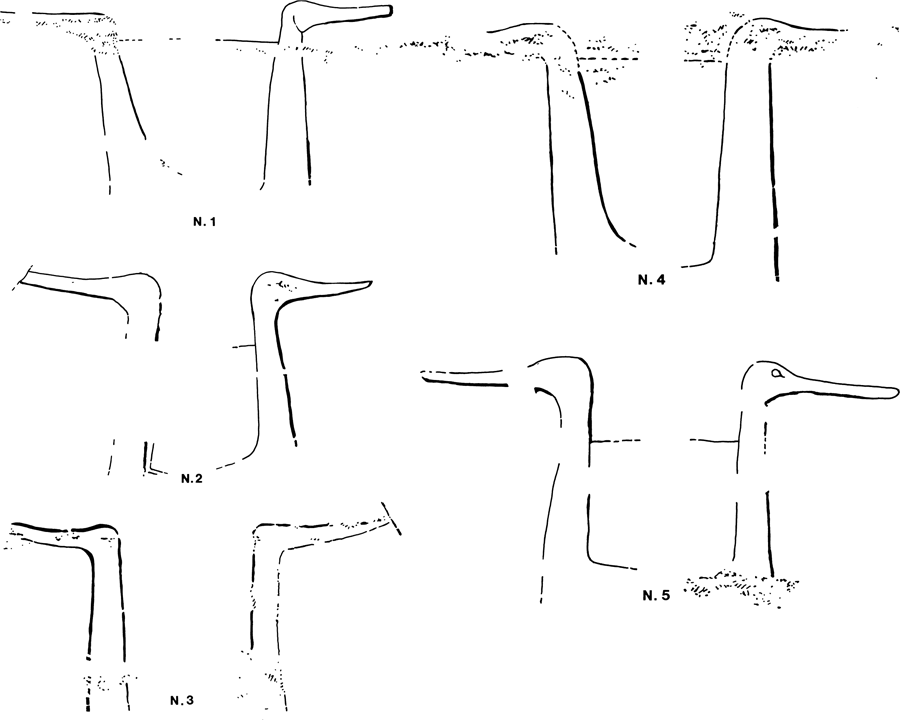

Figure 8.3. Ship N. 1 (photo by B. Brandle)

This scene is instructive concerning ship-based warfare before the introduction of the ram as a nautical weapon.18 The Sea Peoples’ ships are stationary in the water: their oars are stowed and their sails furled. Apparently the invaders were caught at anchor. Indeed, the accompanying text alludes to an ambush that took place in a closed body of water: “The countries which came from their isles in the midst of the sea, they advanced to Egypt, their hearts relying upon their arms. The net was made ready for them, to ensnare them. Entering stealthily into the harbor-mouth, they fell into it. Caught in their place, they were dispatched and their bodies stripped.”19

Figure 8.4. Ship N. 2 (photo by B. Brandle)

Figure 8.5. Ship N. 3 (photo by B. Brandle)

Figure 8.6. Ship N. 4 (photo by B. Brandle)

Figure 8.7. Ship N. 5 (photo by B. Brandle)

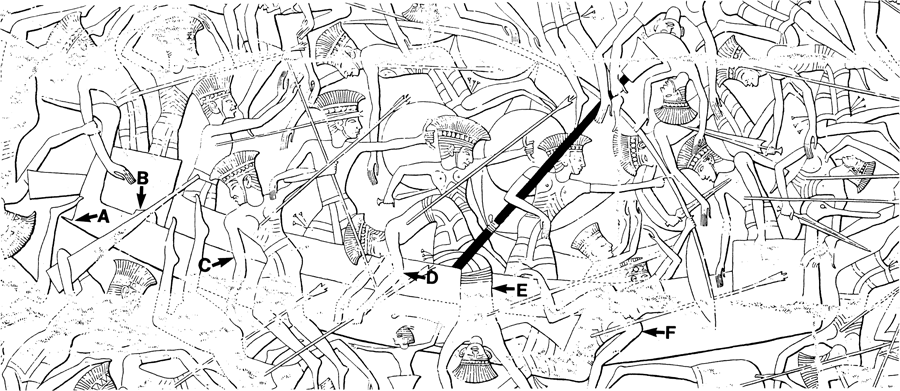

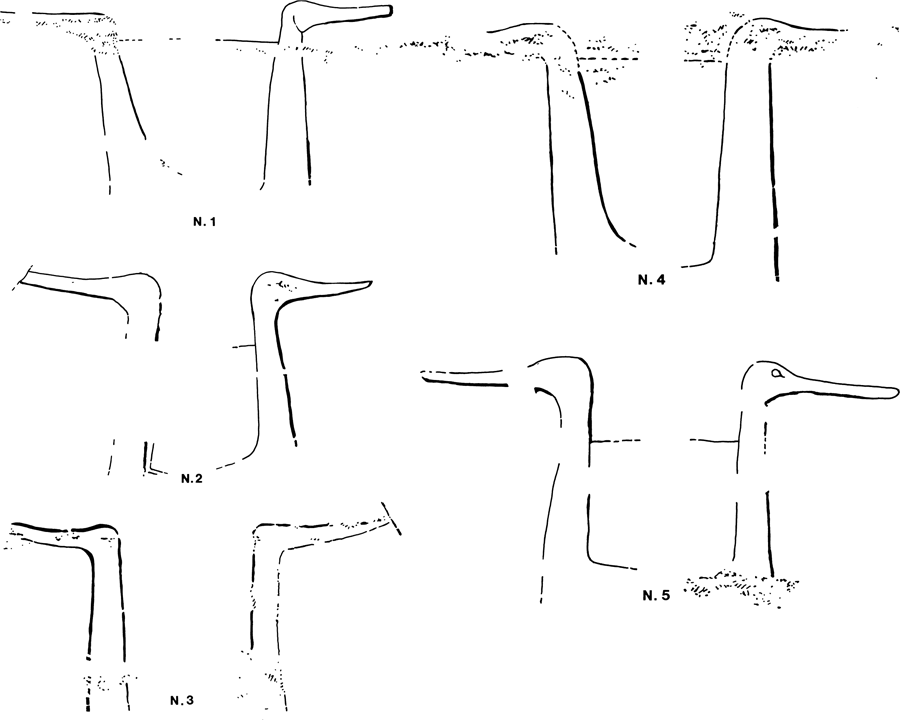

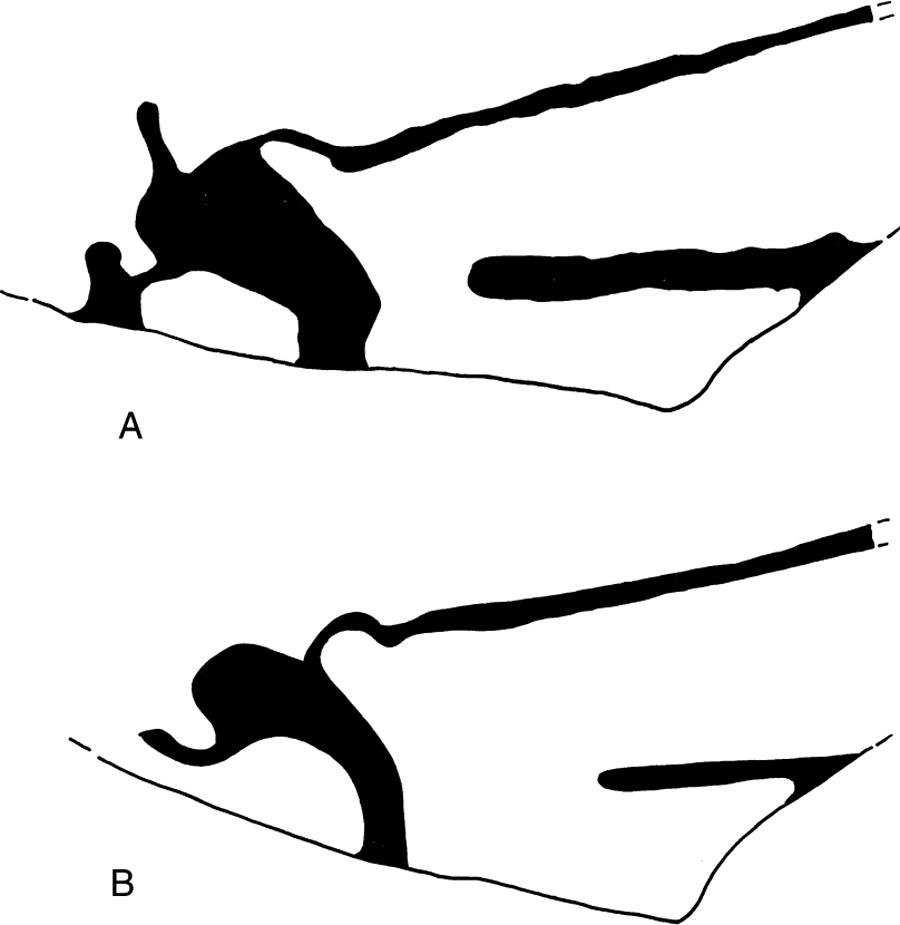

H. H. Nelson has noted that the scene is organized around three conceptual elements: spatial, ideological, and temporal.20 It gives a feeling of a vigorous water battle, almost as if it is a snapshot taken during the battle. Within the framework of this scene, however, the artists have skillfully intertwined various phases of the battle (Fig. 8.2).21 The beginning of the battle is portrayed by Egyptian ship E. 1 and Sea Peoples’ ship N. 1. The middle phase is represented by ships E. 2 and N. 2, while E. 3 and N. 3 signify the end of the battle. A final time element is indicated by ship E. 4, which is loaded with shackled prisoners and is heading for the victory celebration.

It is to be expected that the artists stereotyped the Sea Peoples’ ships into only one form, in keeping with their generalizing portrayal of the naval battle (Figs. 8.3–8, 10–12, 14). We need not assume that this was the only kind of ship in their service.

The same holds true of the Egyptian ships. An inscription on the Second Pylon at Medinet Habu indicates that on the Egyptian side, at least three classes of ships took part in the battle.22 Only one Egyptian ship type, depicted four times, appears in the relief, however. Evidently, the relief contains five representations of the same Sea Peoples’ ship instead of depictions of five different ships.

Nelson emphasizes the vivid nature and uniqueness of the Medinet Habu reliefs, which depart to a degree from conventional Egyptian art:

The artist has indicated not merely the accessory elements of dress and weapons incident to this or that foreign nation, but the variations in features, expression, profile, and other physical characteristics are clearly marked. The facial renderings are in some cases unprecedented in the history of art. They not only discriminate between the living and the dead, but there is an unmistakable effort to make the features express fear, anguish, or distress. Another unprecedented psychological element is to be recognized in the upthrown arm of a drowning man [Fig. 2.36: A: B]. Older Egyptian art always showed the entire human figure in such a case; but the ancient artist at Medinet Habu has understood the horror suggested by the despairing gesture of a drowning enemy engulfed by the sea and invisible except for his upthrown arm.23

Figure 8.8. Ship N. 2 (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39 [H. H. Nelson et al., Medinet Habu I: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III, University of Chicago. Introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930])

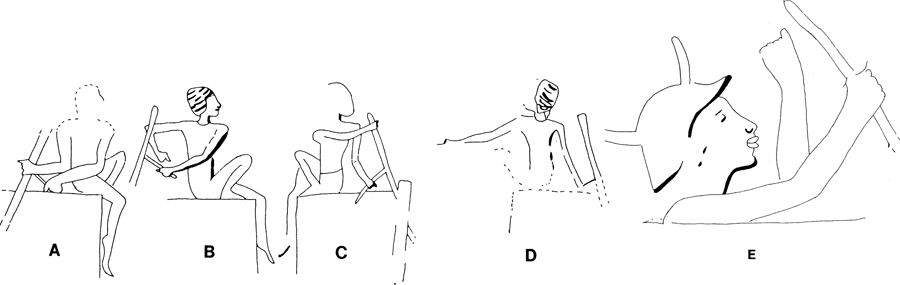

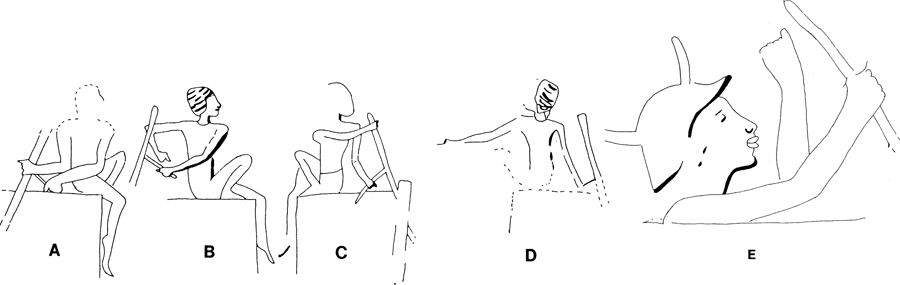

Figure 8.9. The helmsmen of ships E. 1–E. 4 (A–D) and N. 4 (E) (after Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39)

What was the artist’s source for this depiction? We know that artists took part in Egyptian campaigns and trading expeditions outside the borders of Egypt.24 Perhaps a field artist could have recorded one of the invading ships that had been washed ashore or taken prize. Such a drawing could have later served as a master copy for the artists portraying the Sea Peoples’ ships on the Medinet Habu relief.

To understand the ships, we must first understand the art form in which they were created. Originally, the relief was painted. In Egyptian painted relief, the artist did not necessarily differentiate between the relief and the painting. Indeed, the plastic representation appears to have been subordinated to the painting. Nelson’s description of another war scene at Medinet Habu, where the paint had been preserved, is illuminating in this regard:

Figure 8.10. Ship N. 1 (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39 [H. H. Nelson et al., Medinet Habu I: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III, University of Chicago. Introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930])

Figure 8.11. Ship N. 4 (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39 [H. H. Nelson et al., Medinet Habu I: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III, University of Chicago. Introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930])

Figure 8.12. Ship N. 5 (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39 [H. H. Nelson et al., Medinet Habu I: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III, University of Chicago. Introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930])

Here, in the upper portions of the relief, even the water-color paint is unusually well preserved, and we find that the bare sculpture has been extensively supplemented by painted details distinctly enriching the composition. The colors of the garments worn by the Libyans stand out clearly. Between the bodies of the slain as they lie upon the battlefield appear pools of blood. The painter has suggested the presence of the open country by painting in wild flowers which spring up among the dead. Moreover, it is apparent that the action takes place in a hilly region, for streams of blood run down between the bodies as the enemy attempt to escape across the hills from the Pharaoh’s pursuing shafts. The details of the monarch’s accoutrements are indicated in color, relieving him of the almost naked appearance often presented by his sculptured figure when divested of its paint. It is not infrequent to find such details as bow strings or lance shafts partly carved and partly represented in paint. The characteristic tattoo marks on the bodies of the Libyans are also painted in pigment only. When all these painted details have disappeared, though the sculptured design may remain in fairly good condition, much of the life of the original scene is gone and many aids to its interpretation are lost.25

Figure 8.13. The horizontal lines on ships N. 1–2, 4–5 (drawn by the author)

This is one way to explain why some elements on the Sea Peoples’ ships are not represented consistently. Presumably, the same detail may have been applied in paint in some cases and carved (and painted) in others.

Figure 8.14. Ship N. 3 (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39 [H. H. Nelson et al., Medinet Habu I: Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III, University of Chicago. Introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930])

Sadly, many details of the ships have been lost, along with the paint. The relief that remains is only the skeleton of the original work. Furthermore, plaster was used extensively to cover up defects in the masonry and to make corrections (Fig. 2.36: B–D).26 In some cases, only the original draft of the design is left. The final draft had been carved into plaster that has long since disappeared.

There are numerous “disappearing” elements. Note, for example, that on ship N. 2 the brails appear on the left side of the mast only and that the bird head at the stern of ship N. 5 is eyeless while the head capping the stem has a carved eye (Figs. 8.8, 12).27

The quarter rudders on the invaders’ ships now lack tillers; originally they did have tillers, which were represented in paint only and have long since vanished. This is evident from the manner in which the helmsman of ship N. 4 grasps the loom of his quarter rudder in his right hand while his left hand is clenched around a now nonexistent tiller (Fig. 8.9). Compare this to the two-handed manner in which the helmsmen on the Egyptian craft are maneuvering their steering oars. All four hold the tiller with their left hand; two also hold the loom with their right hand.

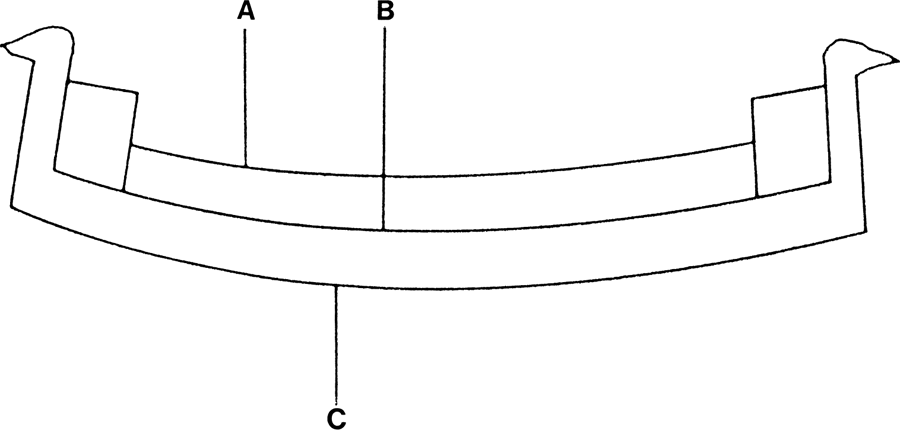

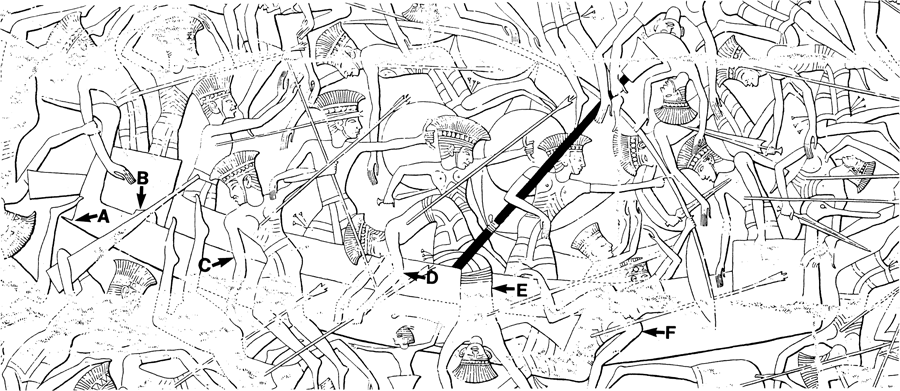

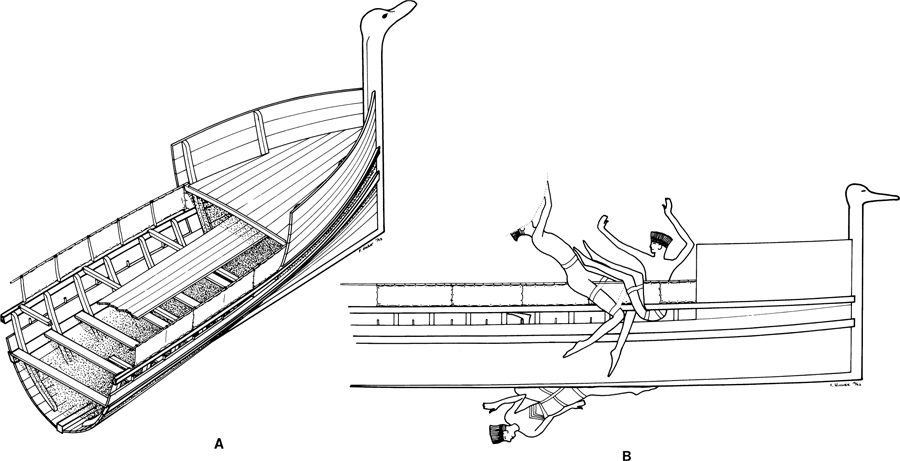

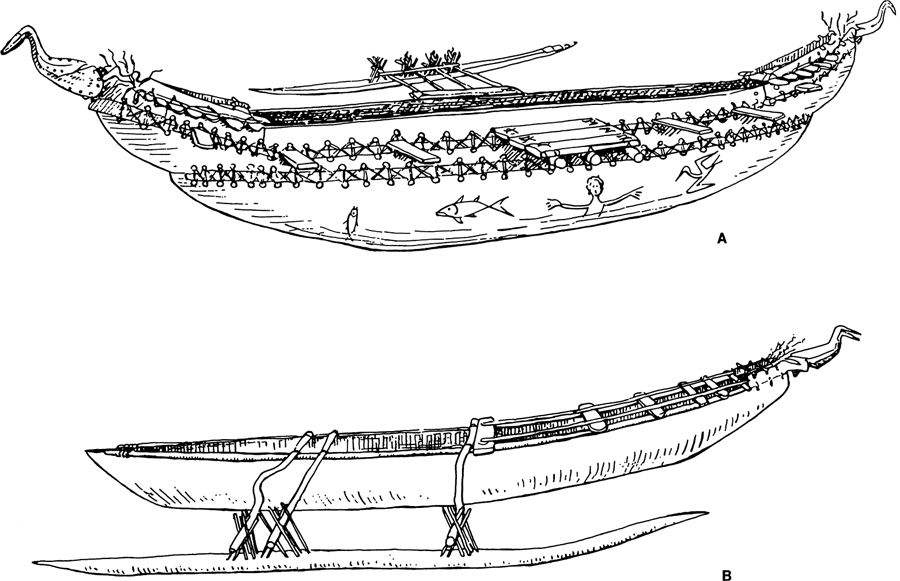

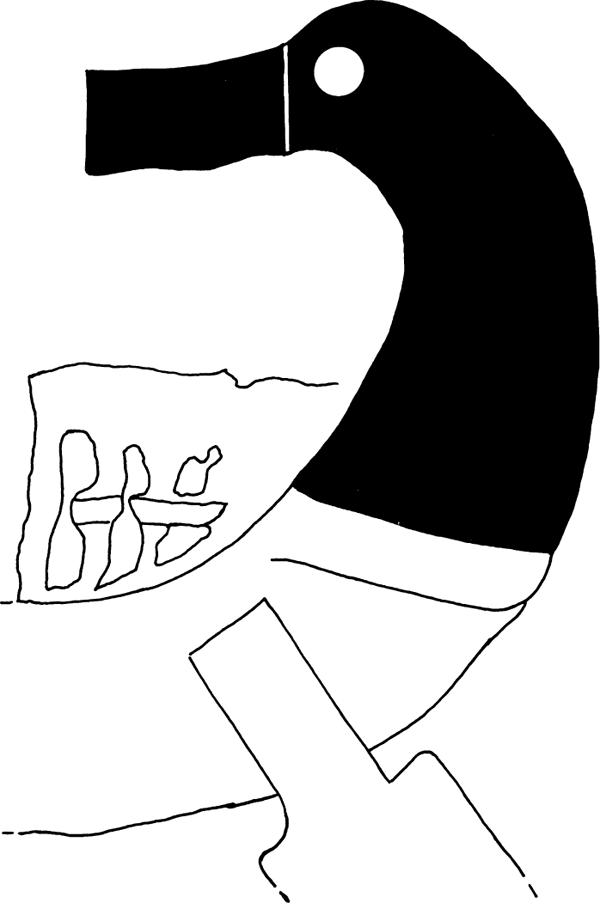

The Sea Peoples’ craft have gently curving hulls ending in nearly perpendicular posts capped with bird-head devices facing outboard. Raised castles are situated at both bow and stern. The actual structure of these ships may be derived from a careful study of the horizontal parallel lines that appear on the ships and the manner in which the live warriors and dead bodies are positioned relative to them. Care must be taken when interpreting this evidence, however.

Figure 8.15. The horizontal lines on ship N. 3 (drawn by the author)

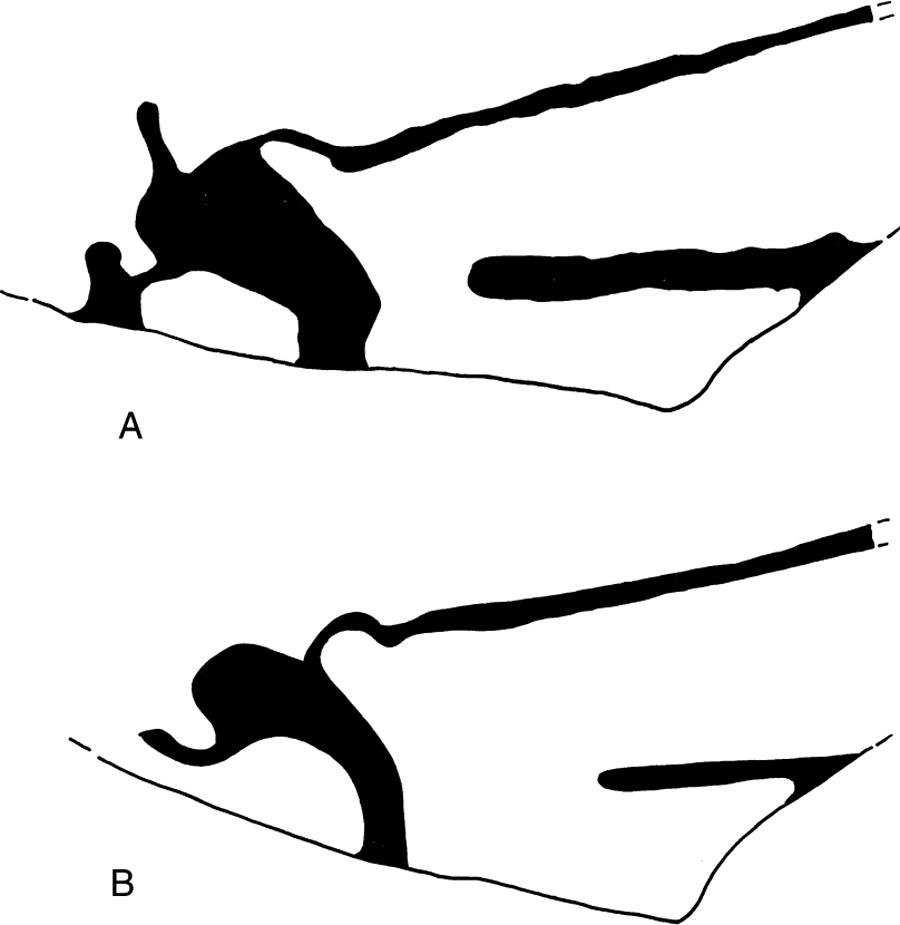

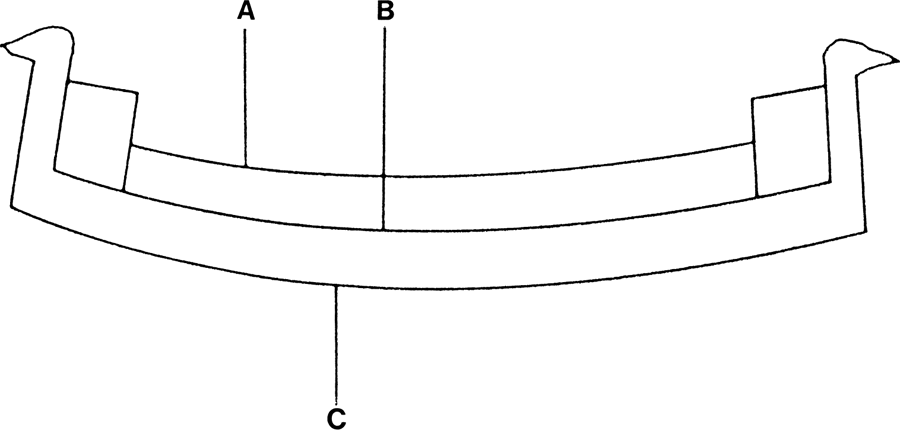

The hulls of four of the Sea Peoples’ ships—N. 1, N. 2, N. 4, and N. 5—are defined by three horizontal lines that we shall term, from top to bottom, A, B, and C (Fig. 8.13). At first glance, these seem to correspond to the three horizontal parallel lines on the Egyptian ships that represent, from top to bottom, the border of a light bulwark protecting the rowers, the caprail, and ship’s bottom (Figs. 2.35–42).28 A closer study, however, indicates that this is not the case. The following observations clarify this matter:

Figure 8.16. Ship construction scene from the Tomb of Tí. A plank with mortise-and-tenon joints is being aligned on the hull. Note the worker’s leg visible between the plank and the hull (Fifth Dynasty) (from Steindorff 1913: Taf. 120)

• Warriors standing in the center of the ship are covered by line A at varying heights from shin to thigh level; dead bodies bent over line A cross lines B and C (Figs. 8.8: C, 10: A, 11: A, 12: E [note also 12: C, F]). These figures reveal that the areas between lines A, B, and C all represent the ship’s sheer view. They do not denote the deck area in plan view.

• Line B appears as a baseline with bodies appearing directly above it. In ship N. 2, the warrior being skewered at the bow is resting on line B (Fig. 8.8: A). This is not accidental since his left foot is placed on the same line. To the right of A, his companion, B, is falling headfirst. His body crosses line A, but his left arm seems to disappear behind line B. Similarly, in ship N. 4 the helmsman and a dead warrior appear directly above line B (Fig. 8.11: C–D). The dead man is being held by his companion, B, who is standing above him and behind line A. This indicates that, in addition to the raised decks in the castles, the craft must have been at least partially decked.29

• Ship N. 3 differs from the other Sea Peoples’ ships by having an additional horizontal line between lines A and B (Fig. 8.14). We shall term this line X (Fig. 8.15). The key to understanding the three horizontal areas (AX, XB, and BC) formed by these four lines is to study the manner in which the dead and dying bodies of the fallen warriors are arranged in relation to them.

The ship has capsized. One warrior lies on keel line C (Fig. 8.14: A).30 His left leg disappears behind the hull in area BC, but his foot, B, reappears in area XB. Similarly, body C is “folded over” area AX; its abdomen is visible in area XB while the torso emerges below line A. The leg of another body, D, disappears behind area AX and reappears in area XB, passing outside the ship’s hull over lines B and C.

These three independent clues indicate that area XB must represent an open space. The only explanation for this space is that it served as an open rowers’ gallery through which oars were worked, located between the caprail and the light bulwark. If line X is added to ships N. 2 and N. 4, the positioning of the figures in relation to them becomes immediately clear. Originally, line X may have been painted on ships N. 1, 2, 4, and 5, as perhaps were the stanchions that would have been required to support the light bulwark.

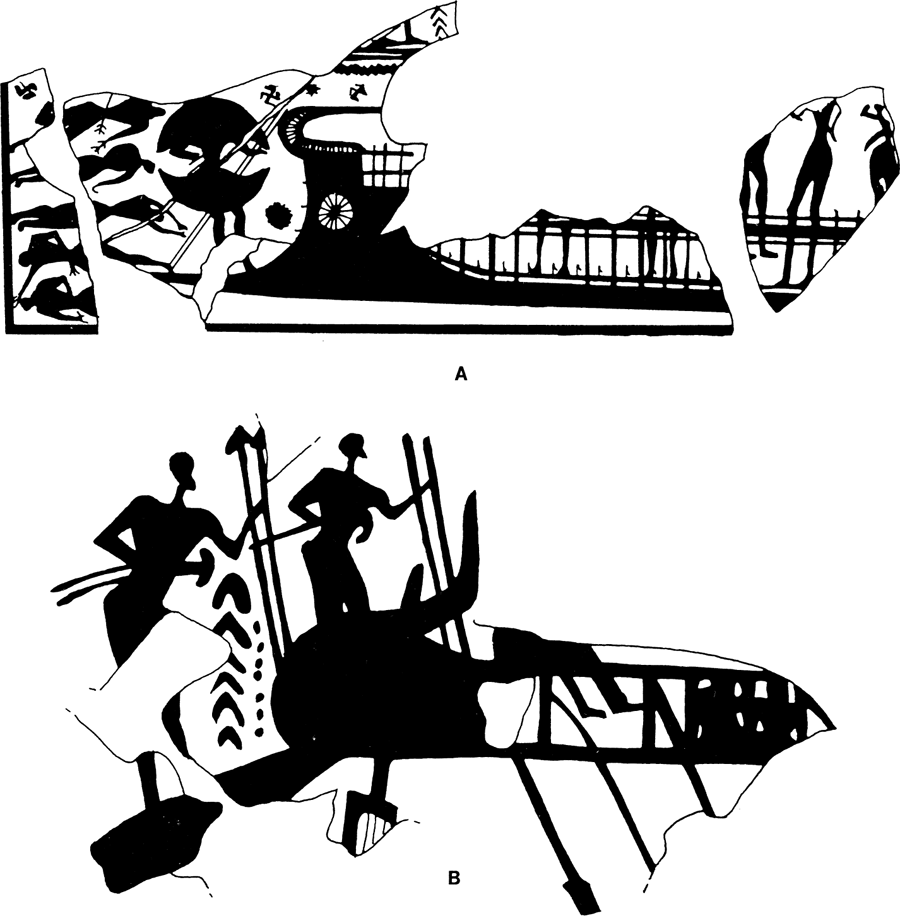

These ships find their closest contemporaneous parallels in the Late Helladic galleys discussed in the previous chapter. In particular, they are virtually identical in nearly all surviving details to Kynos A (Fig. 7.8: A).

Artists’ errors appear on the representations of Sea Peoples’ ships at Medinet Habu. Note that the mast mistakenly crosses area AB in ship N. 2 and area AX in ship N. 3 (Figs. 8.8, 14), although it is depicted correctly in ships N. 1, N. 4, and N. 5.

Although the hand of a master artist appears to have guided the wall relief, the work was evidently carried out by artists of varying capabilities.31 Some of the artists made errors in depicting the ships’ construction. Note, for example, the figure in ship E. 1 bending over to grasp a sword from the floating body of an enemy warrior (Fig. 2.36: A: A). Unlike the two other soldiers plausibly portrayed leaning over the screen, the upper body of the former is placed in an impossible manner, leaning over the line that represents the sheerline and the screen. To best understand correctly what the Egyptian artist(s) had in mind when portraying a ship, therefore, it is important to have several independent clues corroborating the same details. Happily, such is the case in N.3. The bodies disappear behind the screen and then reappear on the other side in proper perspective. The method used here by the artist to display the three bodies woven around elements of the vessel’s structure on ship N. 3 is not unique in Egyptian art, although it is exceedingly rare.

Another example of a human figure disappearing behind an object and then reappearing, as do the bodies in ship N. 3, exists in the Fifth Dynasty mastaba of Tí at Saqqara, where a plank is being fitted to a hull in a scene of ship construction (Figs. 8.16; 10.16–17).32 One worker is supporting the hull with a short rope. Next to him another man kneels behind the plank and hammers it down with a small cylindrical weight. The man’s right leg disappears behind the plank, but his foot reappears in the space between the plank and the hull. The foot could be mistaken for a tenon were it not for its red skin color that is still visible.33

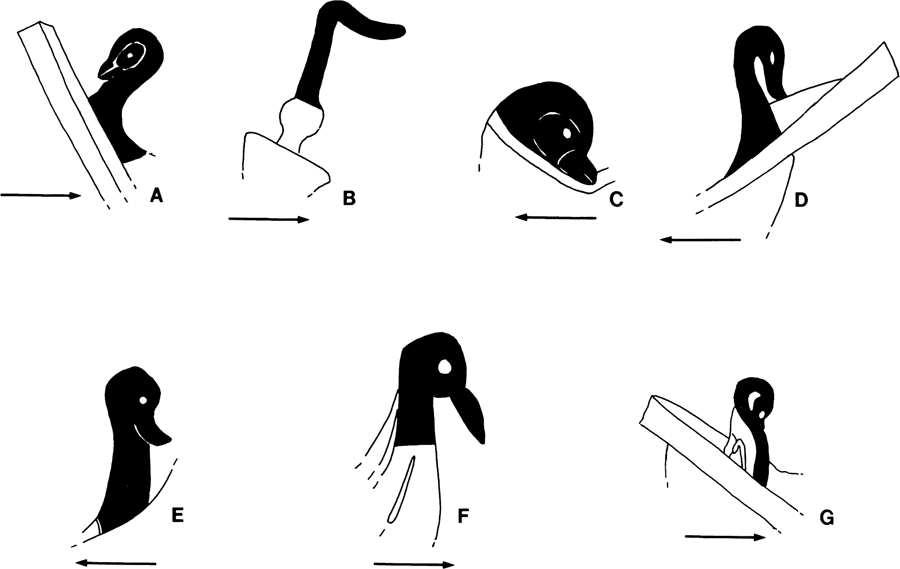

Figure 8.17. The deck structure of Greek Geometric galleys: (A) figures stand on the rowers’ benches in an area that is not covered by a deck; (B) the legs of a figure sitting at deck level appear through a “window” of the open rowers’ gallery (A after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. le [Geom. 2] and Casson 1995A: fig. 68; B after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 7b [Geom. 38])

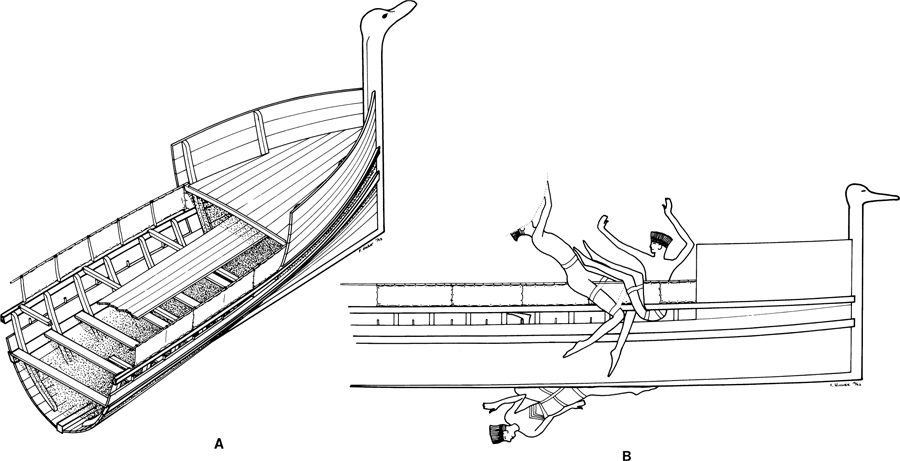

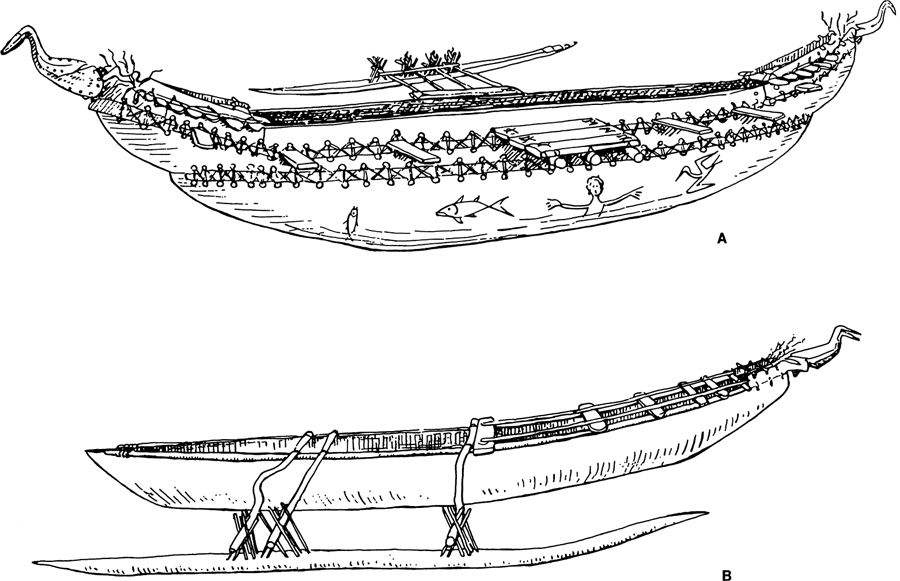

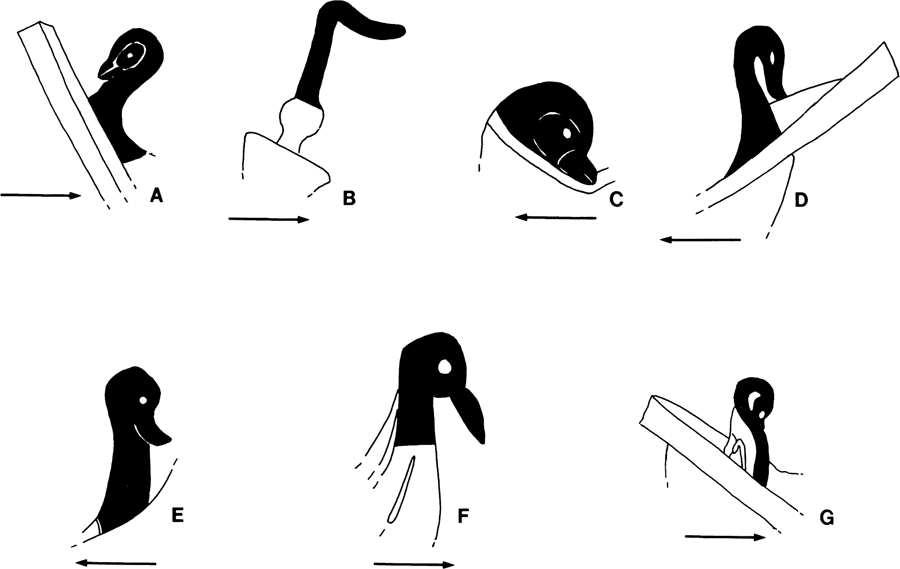

Figure 8.18. (below) (A) Tentative isometric reconstruction of a Sea Peoples’ ship depicting the main elements of the ship’s architecture as indicated by the bodies of the dead warriors (B) Tentative sheer view of a Sea Peoples’ ship with the three bodies of warriors in ship N.3 added to better illustrate constructional details (drawings by F. M. Hocker. Courtesy of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology.)

The men depicted in the ships suggest that the deck on the Sea Peoples’ ships ran the full length of the hull, from the forecastle to the sterncastle. The intertwining of bodies in the manner shown in ship N. 3, however, would be impossible if the deck had extended the entire width of the ship. This means that planking must have been left out along the sides.

This feature connects the Sea Peoples’ vessels to the Aegean tradition of galleys as it appears on Mycenaean and Greek Geometric warships. Planking must have been missing along the sides of the Kynos A ship to allow the rowers’ heads to disappear behind the screen (Figs. 7.8: A, 9); L. Casson notes that in some fighting scenes, warriors are shown standing on the rowers’ benches at a point that was not covered by the raised deck and that the part left undecked must have been along the sides where the rowers sat (Fig. 8.17).34 Figure 8.18: A is a tentative isometric reconstruction of a Sea Peoples’ ship illustrating the basic elements discussed above. Figure 8.18: B is a tentative sheer view of a Sea Peoples’ ship with the three warriors’ bodies added to better illustrate the constructional details. Note that the bodies are depicted to a scale larger than that of the ship.

The Sea Peoples, it appears, brought with them to the eastern Mediterranean the concept of the oared warship with an open rowers’ gallery supported by vertical stanchions. From the twelfth century B.C. onward, the development of warships in the Aegean and along the Phoenician coast followed separate lines of development from a common ancestor, resulting ultimately in the Greek dieres and the Phoenician bireme. This explains the appearance of bird-head devices on later Phoenician warships (Fig. 8.53).

Perhaps the prototype of the Sea Peoples’ ships depicted at Medinet Habu was a penteconter. While in the water battle relief we see their ships solely in their fighting mode; these same ships may also have been used at times to transport the families of combatants, as well as their movables, during the waterborne migrations. Indeed, this may explain why, as we have seen above, the Hittite king defines one group of Sea Peoples, the Sikila, as those “who live on ships.”

The Sea Peoples’ ships carry two (Figs. 8.10, 12), one (Figs. 8.8, 11), or no (Fig. 8.14) quarter rudders. Of the ships with two quarter rudders, N. 1 has both placed on its starboard quarter, which is the side of the ship facing the viewer; ship N. 5 appears to have a rudder on either quarter. The quarter rudder on the near (starboard) side is held in what seems to be a wooden bracket (Fig. 8.12: B).35

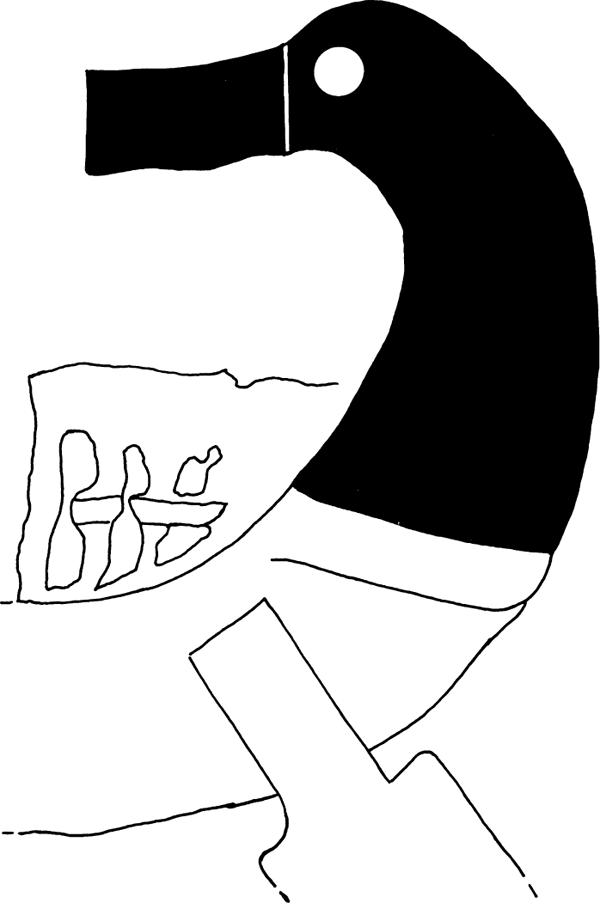

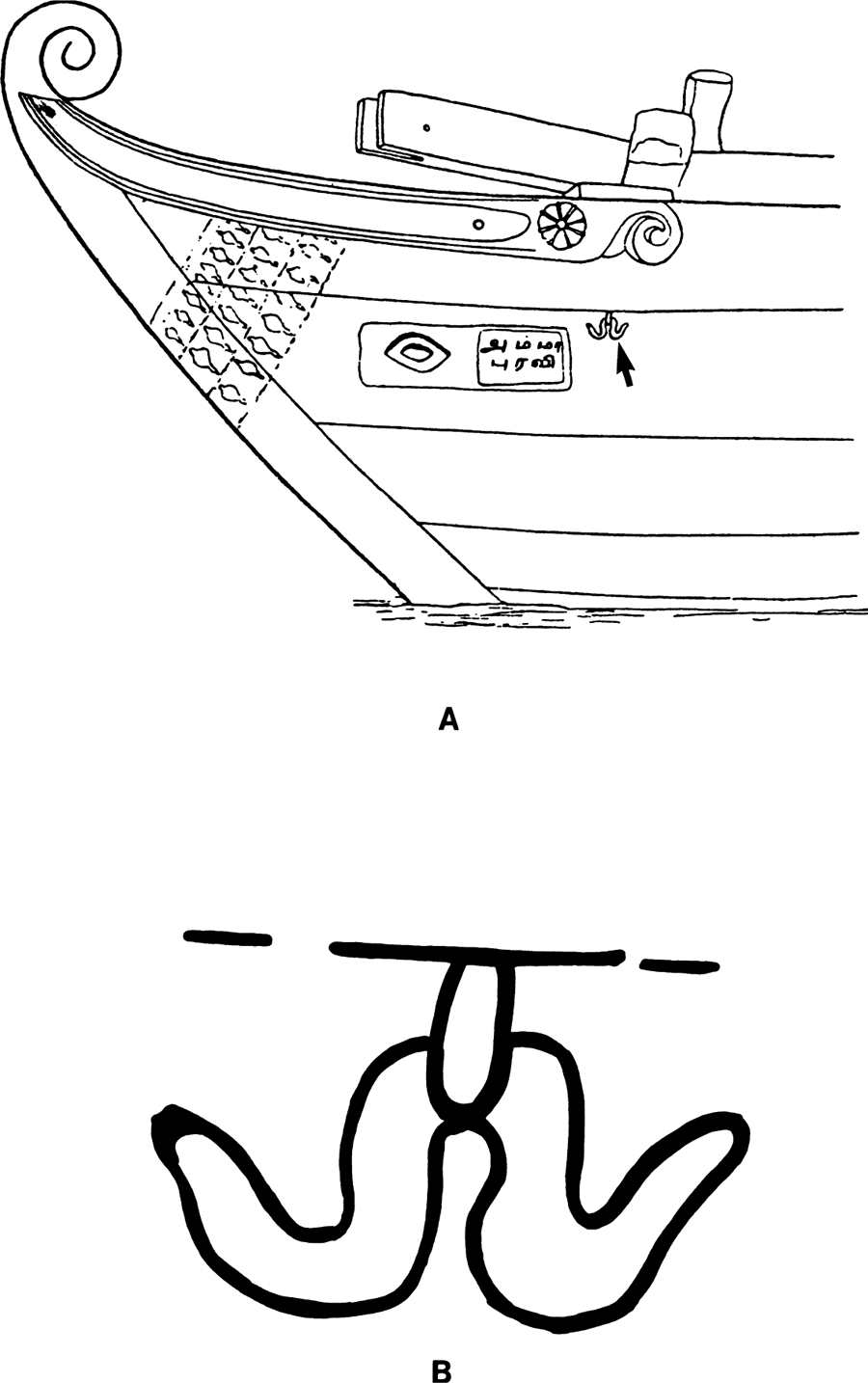

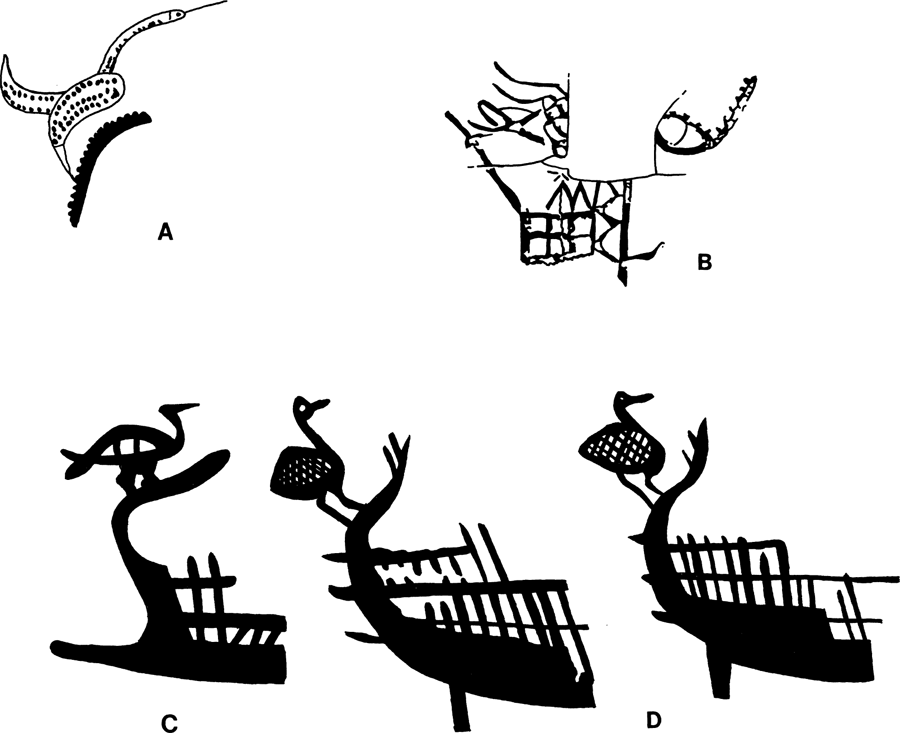

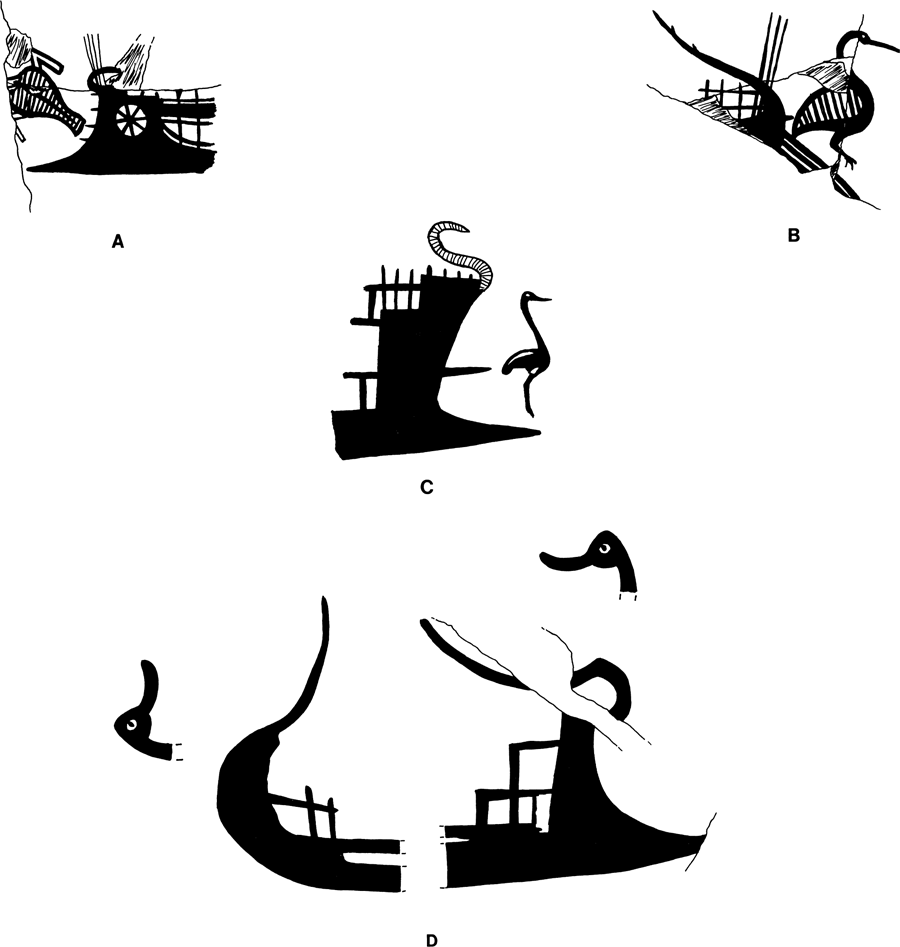

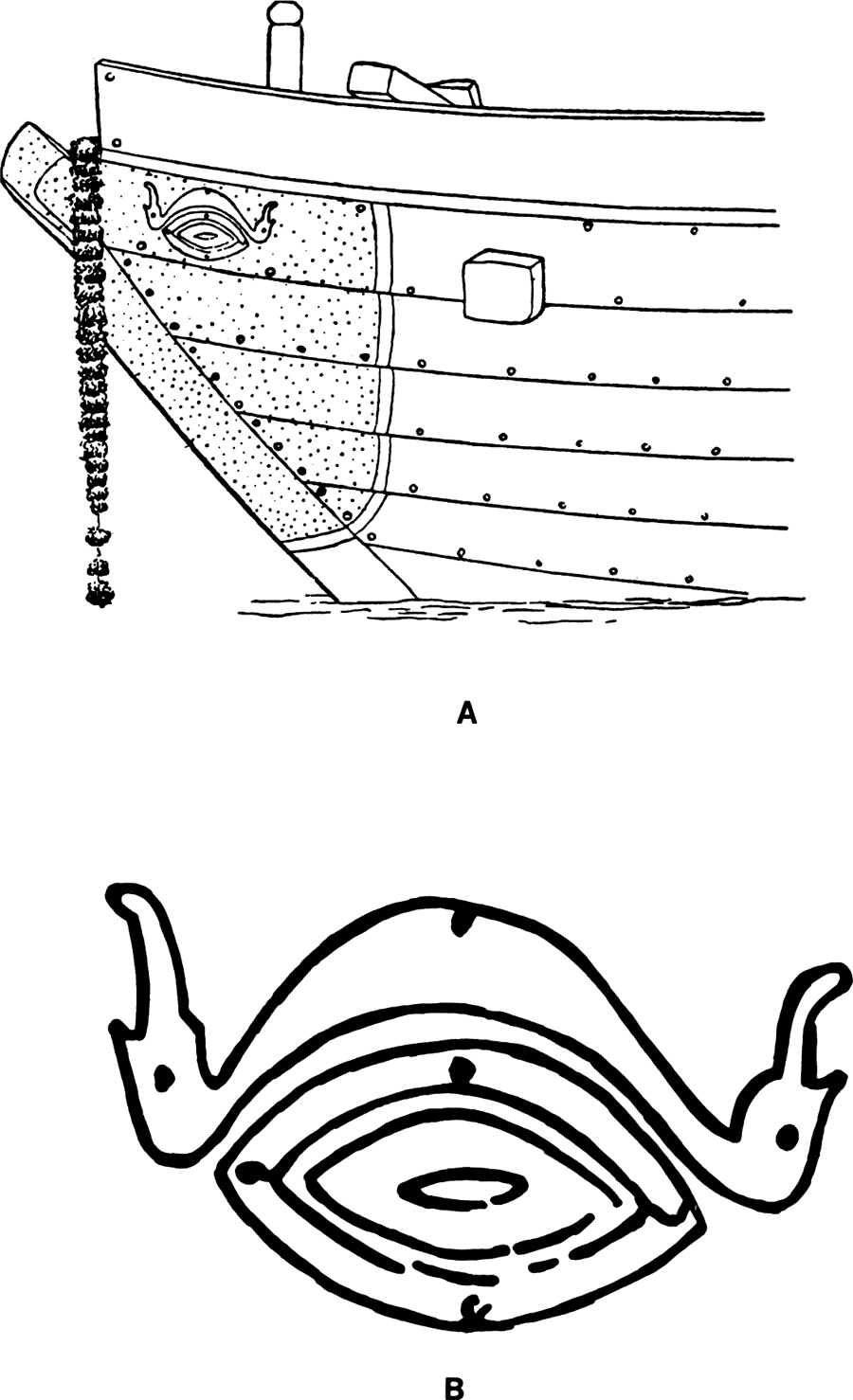

Figure 8.19. (A) Painted decoration, including a ship, depicted on a funerary urn found at Hama (ca. 1200–1075 B.C.); (B) detail of the ship. Note the bird-head device capping the stem (A from, B after Ingholt 1940: pl. 22:2 [© 1940, Munksgaard International Publishers Ltd., Copenhagen, Denmark])

Presumably, the normal complement was two steering oars, and those missing are attributable to loss during battle. In this matter they differ from contemporaneous representations of craft from the Aegean but seem to herald the use of the double steering oars that were to become common equipment on Geometric craft.36 Alternately, the Sea Peoples may have adopted the use of a pair of quarter rudders after encountering—and capturing—Syro-Canaanite and Egyptian seagoing ships that normally used two steering oars, one placed on either quarter (Figs. 2.17–18, 26; 3.2–3, 10, 12–13). On two ships a small, pointed projection appears at the junction of sternpost and keel (Figs. 8.11: E, 12: A). The position and form of these elements invite comparison with the stern device that appears earlier (apparently with cultic connotations) on Aegean craft.37

The rigging of the Sea Peoples’ ships is identical to that carried by the Egyptian craft with which they are engaged. Both carry the newly introduced brailed rig. Indeed, this is one of the earliest appearances of this type of loose-footed sail.38 The masts are topped by crow’s nests.39 The yard curves downward at its extremities and is raised by twin halyards; these appear only on ship N. 3 (Fig. 8.14). The block through which they must have worked is not represented, nor (with the exception of the brails) are other details of the rigging.

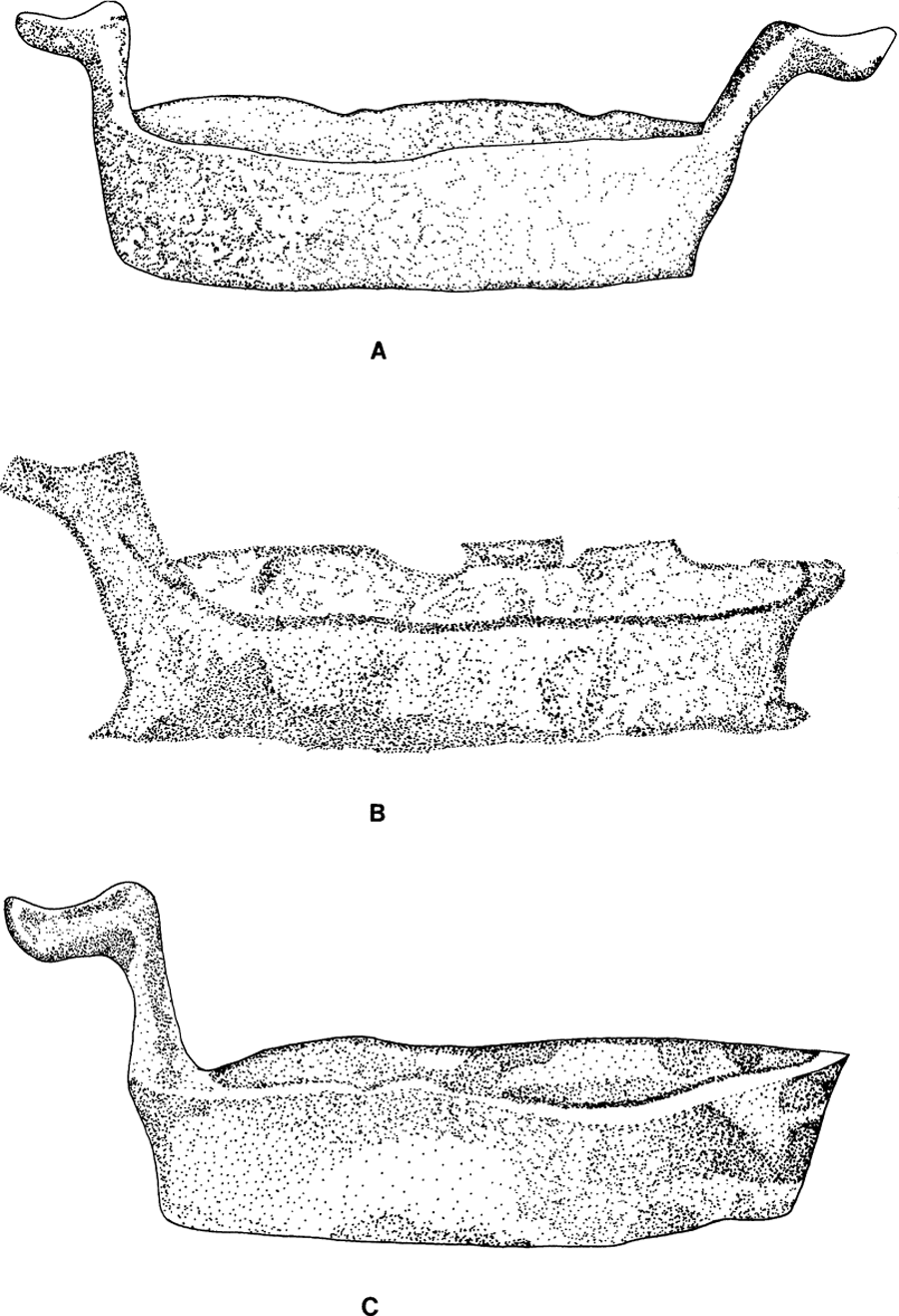

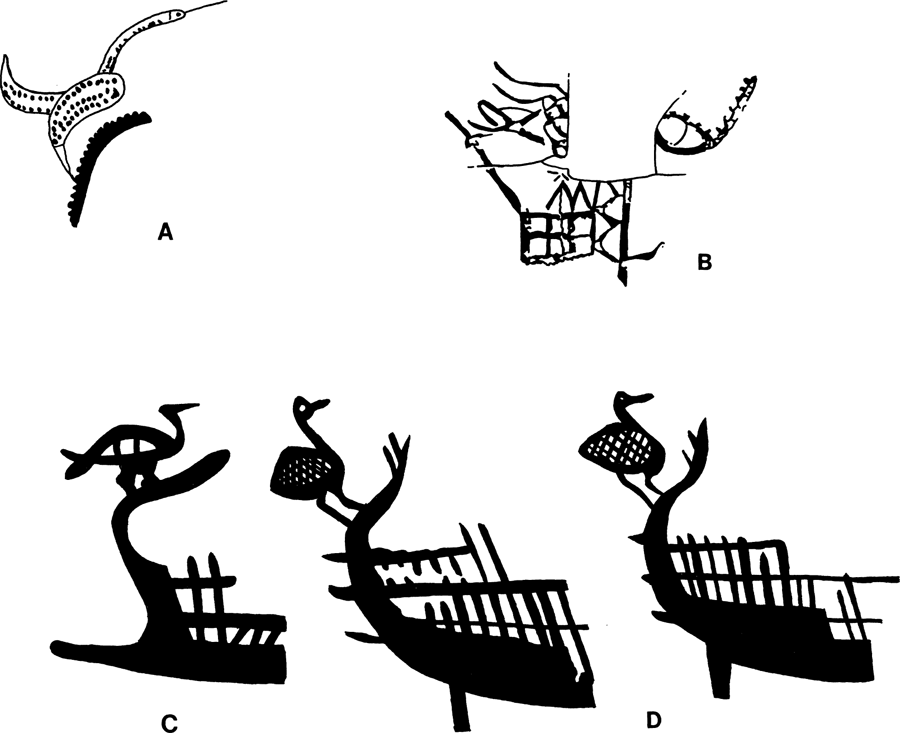

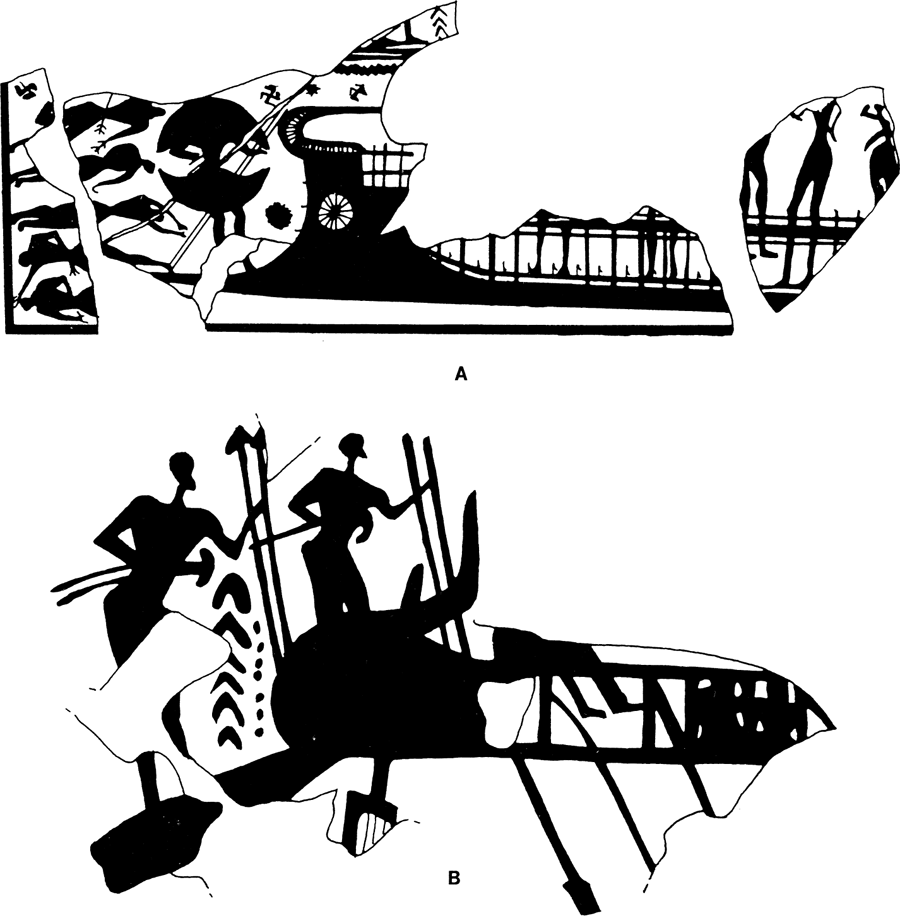

The Hama Ship

A Sea Peoples’ ship was probably the inspiration for a vessel depicted on a burial urn uncovered at Hama in Syria (Fig. 8.19).40 The urn was found in Period I of the cremation cemeteries there (Hama F, early phase), which contained nearly 1100 cremation-burial related urns and which dates to ca. 1200–1075 B.C.41 This form of burial is clearly intrusive as it diverges completely from known local traditions. The material culture of this new group is of European tradition and includes fibulae, flanghilted swords, and the urnfield burials themselves.42 These clearly indicate the arrival of an intrusive element at Hama. The Danish excavators of Hama associated Hama’s urnfield level to the migrations that took place at the end of the Late Bronze Age.43

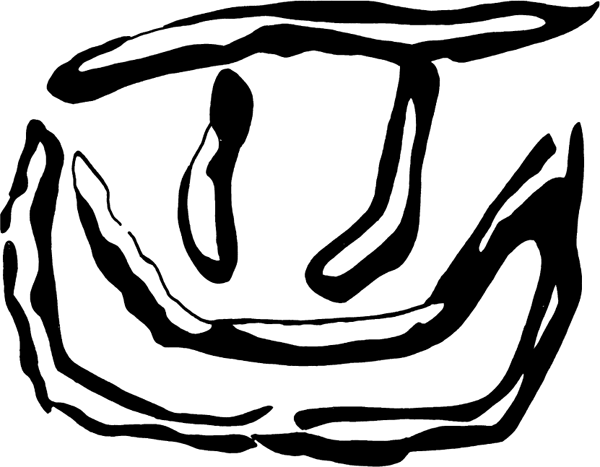

Figure 8.20. Ship graffiti on a stone receptacle from Acco as reconstructed by Artzy and Basch (after Artzy 1987: 77 fig. 2)

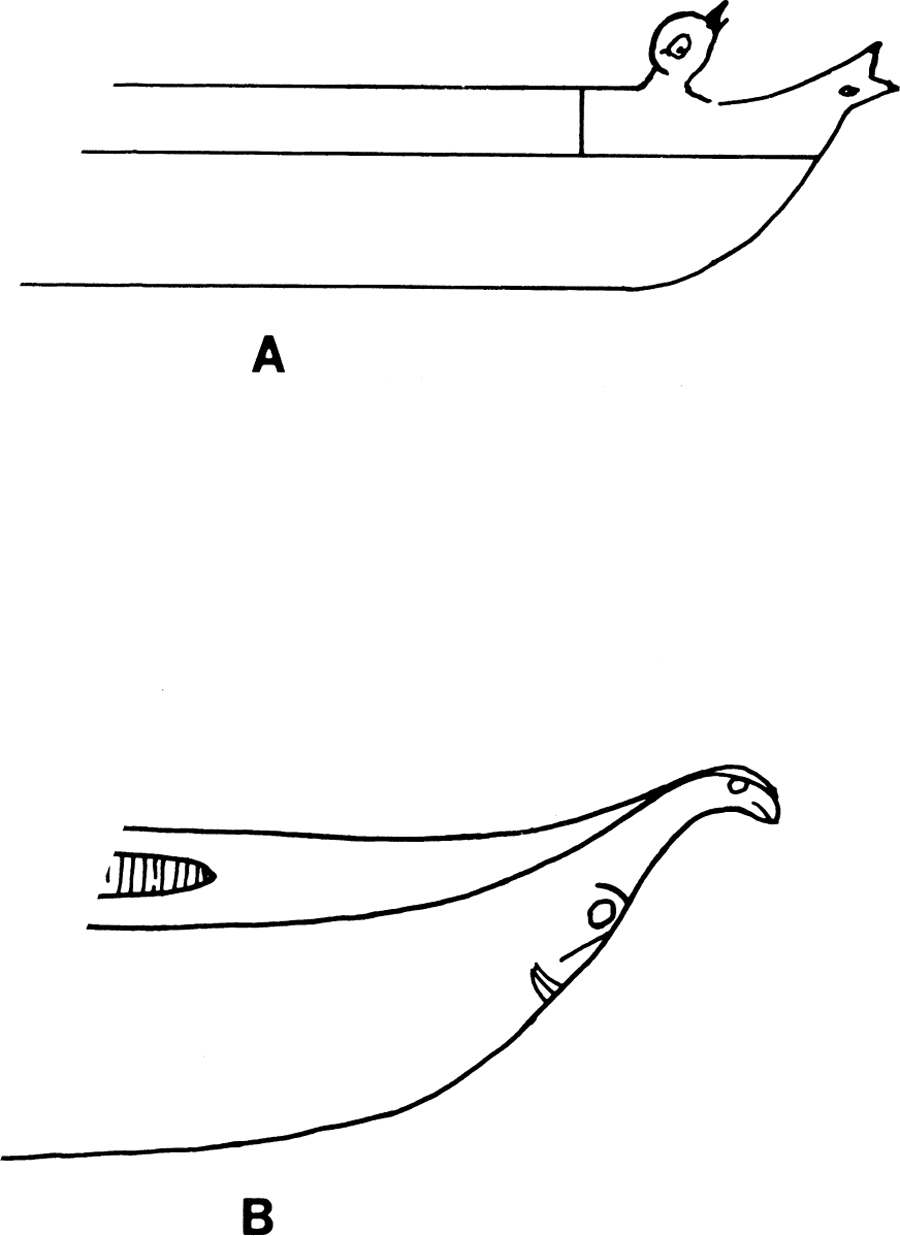

The keel line of the Hama ship is rockered; the stem is vertical, capped by a bird-head device with an upcurving beak (Fig. 7.21; compare 8.61: B–D). The horizontal line that crosses the stem may represent the free-standing wale that can be clearly seen on one of the Kynos ships (Fig. 7.7). The Hama ship has a pronounced, upcurving cutwater bow that continues the line of the keel and extends slightly forward of the bird-head device capping the stem.

Two vertical lines abaft the stem and a structure at the stern may indicate castles. The ship is formed from three painted, curving horizontal lines. The two horizontal bare spaces between the lines are segmented by rows of vertical lines. If one of the sets of vertical lines represents the open rowers’ gallery with stanchions, then the upper set may represent the supports for the open bulwark.

Figure 8.21. Ship engraved on a stone seal from T. 6 at Enkomi (Late Cypriot) (after Schaeffer 1952: 71 fig. 22)

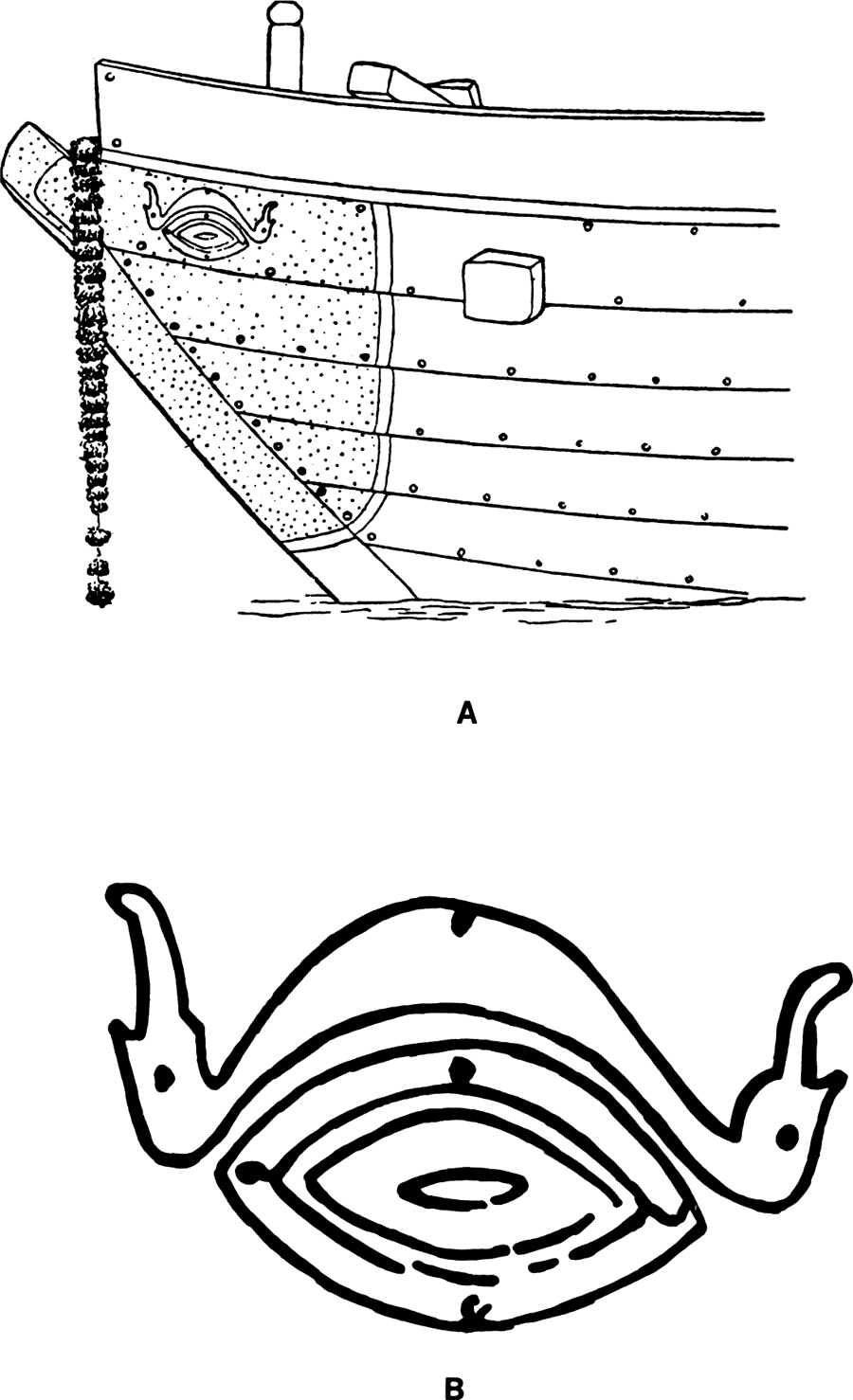

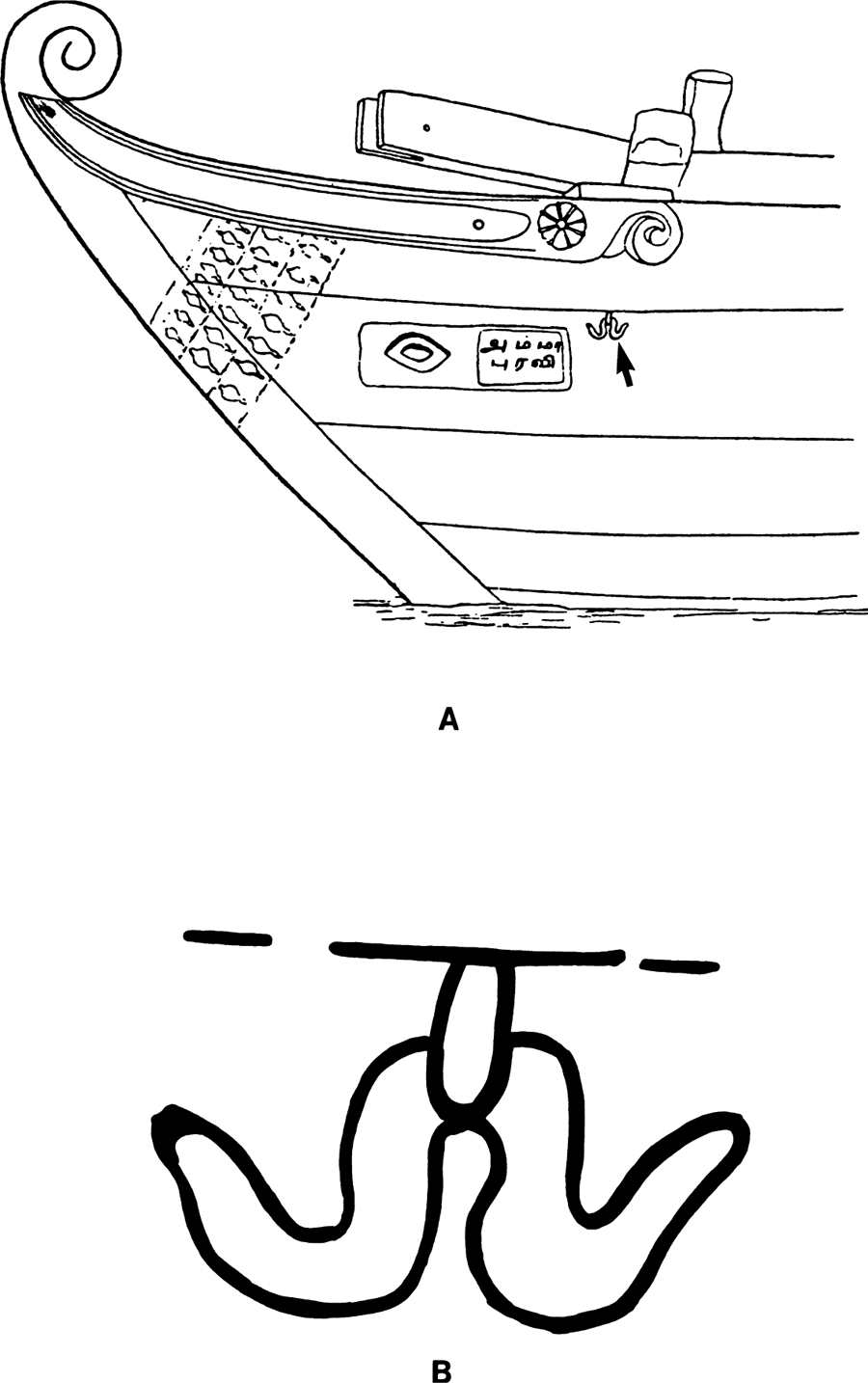

Acco

Several ship graffiti were found incised on a small altar dated ca. 1200 B.C. that was uncovered at Acco in 1980 (Fig. 8.20).44 This appearance of ship representations on a cultic receptacle is paralleled in the Aegean (Fig. 6.64). The largest ship is the most deeply incised. In profile it has a long, narrow hull recurving at stem and stern. Two quarter rudders, one bearing a tiller, indicate that the vessel is facing left. The port rudder has a tiller. A mast is stepped amidships; above it is a square sail. M. Artzy interprets several slanting lines attached to it as shrouds. This identification is dubious, in my view. The remains of two or three additional hulls of similar shape have been identified below the bow of the largest ship.45

Figure 8.22. Figures wearing (feather?) helmets reminiscent of those worn by contingents of the Sea Peoples in the Medinet Habu reliefs (from Morricone 1975: 360 fig. 357: a–c)

Artzy considers the graffiti to represent “round ships” but does not explain the basis for this conclusion. She places emphasis on the finials of the stem and stern, which she terms “fans.” These she compares to the papyrus umbels of Hatshepsut’s Punt ships and to the aphlaston. Neither comparison is convincing. The papyrus umbel was not flat like a fan: it was discoid.46 A probable source for the aphlaston is discussed below. Artzy suggests that the graffiti represent a type of Sea Peoples’ ship that at present might find its only possible parallels in the ship graffiti from Kition.47

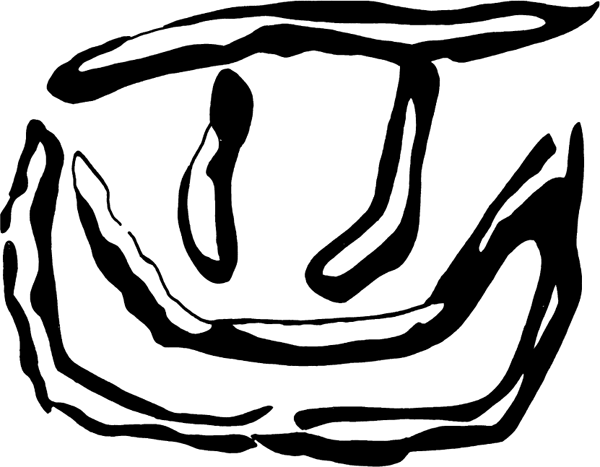

Enkomi

A ship, perhaps of Sea Peoples’ origin, may be engraved on a stone seal of Late Cypriot III date found in T. 6 at Enkomi (Fig. 8.21). C. F. A. Schaeffer defined it as “un sujet difficile à interpréter (bateau).”48 The object represented appears to be an extremely schematic attempt to portray a double-ended ship under sail. The hull is narrow and curved. Schaeffer compares it to the Sea Peoples’ galleys at Medinet Habu.49

Discussion

Differentiating Mycenaean Ships from Those of the Sea Peoples

Although the ships of the Sea Peoples are undoubtedly related to the mainstream of Aegean galley development, it is important to emphasize that no conclusions concerning the ethnic identity of the Sea Peoples as a whole may be deduced from this. Ship varieties can be and were adopted and adapted by peoples having no ethnic connection with the traditional users of the craft. The remarkable similarity of the Sea Peoples’ ship depictions at Medinet Habu to representations of Aegean warships in the fourteenth through twelfth centuries—and now particularly to Kynos ship A—necessitates several key questions. When is a ship portrayed on Late Helladic pottery to be identified as a Sea Peoples’ ship, and when is it a Mycenaean ship? Is it at all possible to differentiate between them?

Indeed, the division of depictions of oared galleys in the twelfth century B.C. into Mycenaean and Sea Peoples ships is largely arbitrary. The problem is compounded because these ships appear, for the most part, at a time (Late Helladic/Late Minoan IIIB–C) and in regions (Greece, Crete, the Aegean, Cyprus, the Levant) where both fleeing Mycenaeans and bands of marauding Sea Peoples are believed to have roamed. Our lack of knowledge as to the ethnic composition of the Sea Peoples following the decline of the Mycenaean world further complicates an already difficult problem that, for the most part, cannot be resolved.

One manner to deal with these questions is to identify the crews depicted on the ships. If we assume that the nationality of a ship’s crew reveals the vessel’s nationality (and even this assumption is open to argument), by defining the crew, we can identify the ship. The Mycenaean/Cycladic warriors connected with the ships depicted on the Late Helladic IIIB krater from Enkomi suggest that these craft are Aegean (Mycenaean) (Fig. 7.28). The vessels of the northern invaders shown at Medinet Habu belong, of course, to the Sea Peoples.

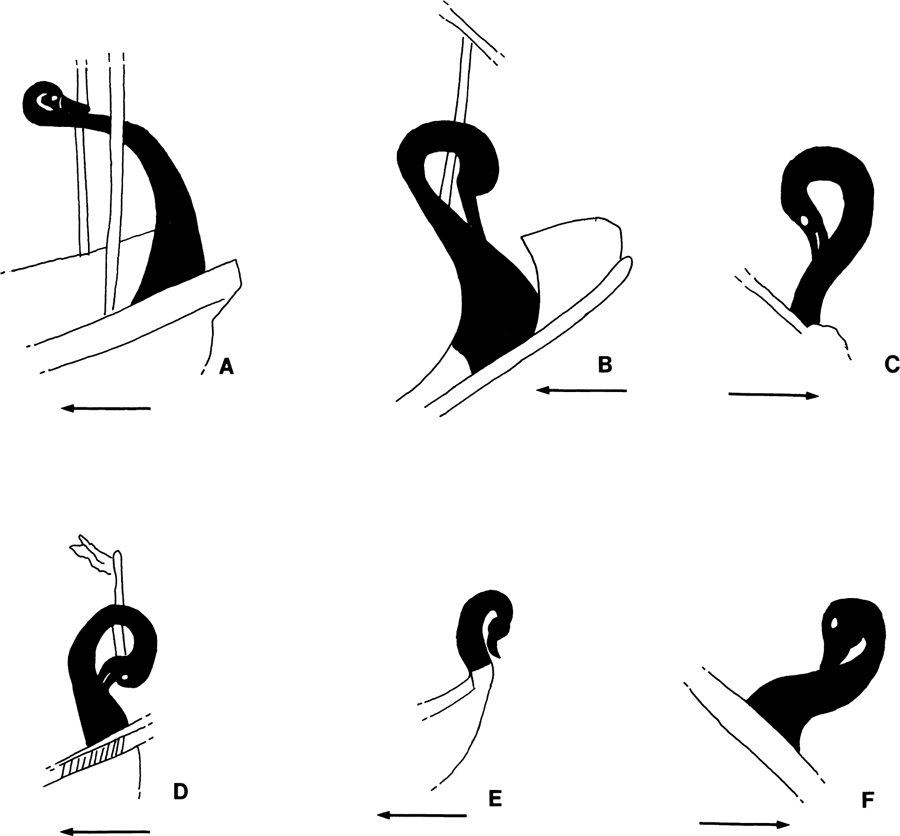

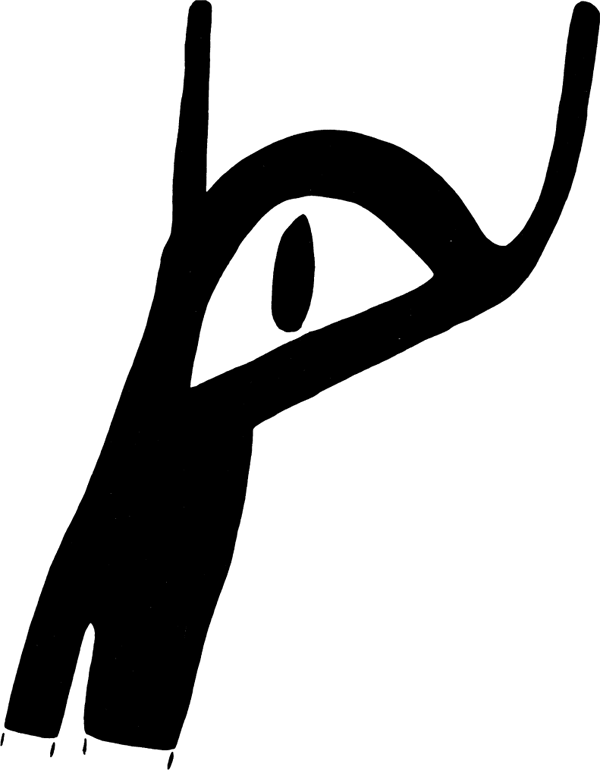

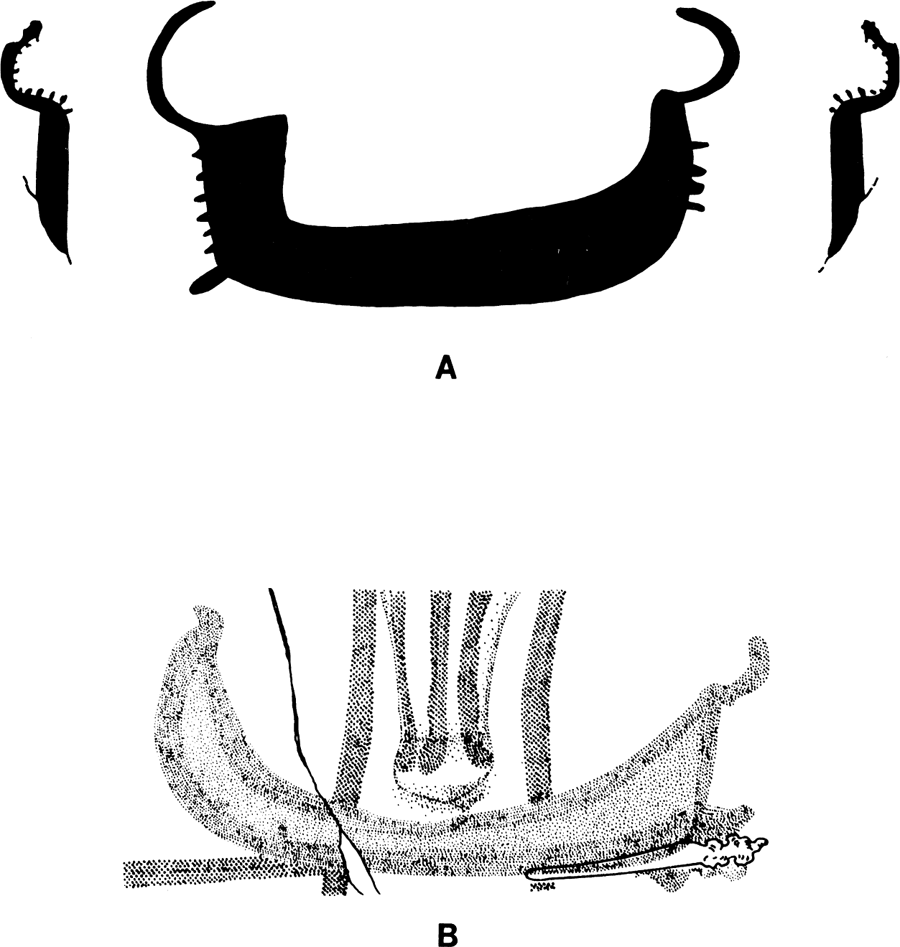

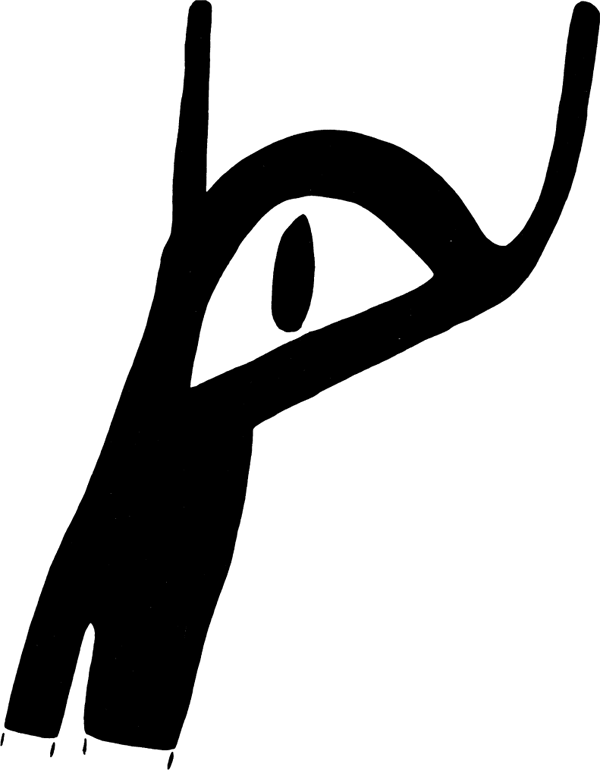

Figure 8.23. Bird-head devices on the five depictions of a Sea Peoples’ ship at Medinet Habu (after Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39)

Sandars has identified as feather helmets the headgear of rowers and other figures portrayed on sherds from Cos (Figs. 7.26; 8.22).50 The slightly earlier “northern bronzes” found in the Laganda tomb at Cos certainly suggest the presence of northerners.51 Similar helmets with multiple protrusions (feathers?) are worn by warriors on the Kynos ships (Figs. 7.8: B, 15, 16).52 Are the crews and the ships depicted at Cos and Kynos Sea Peoples’ galleys?

Bird-head Devices on Mediterranean Ships

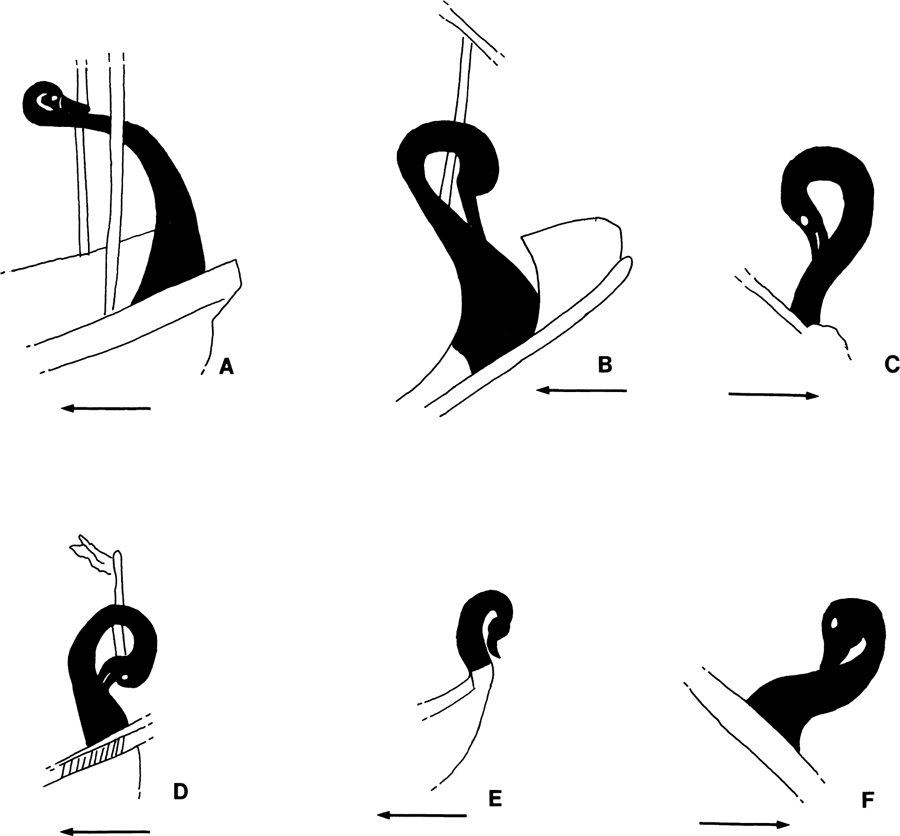

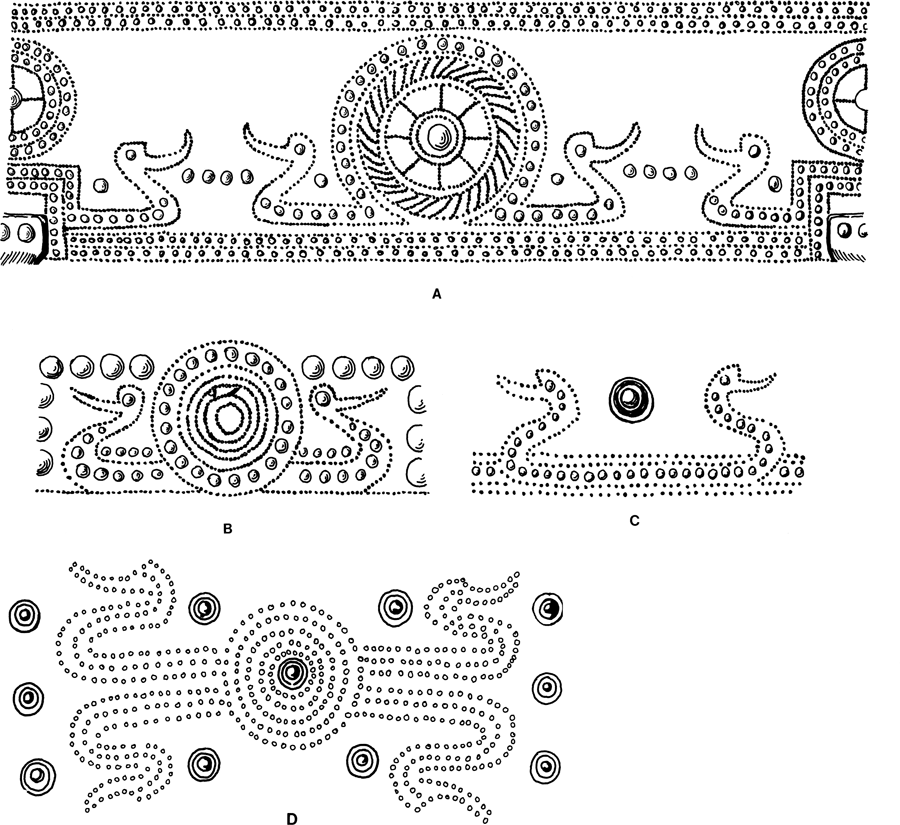

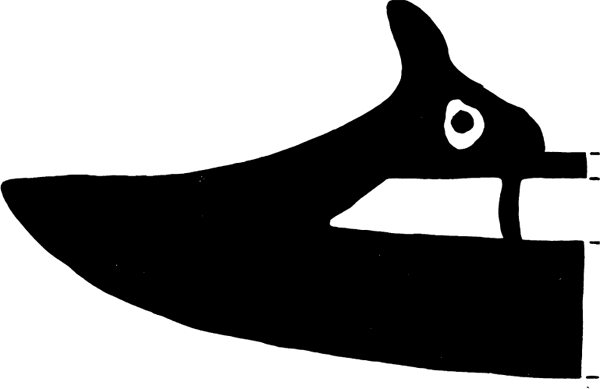

One of the most striking elements of the five depictions of a Sea Peoples’ craft at Medinet Habu is the water bird-head devices capping the stem- and sternposts of the invaders’ ships (Fig. 8.23). Bird-head finials in a myriad of forms served as symbolic and prophylactic devices on Mediterranean ships, beginning no later than the second millennium.

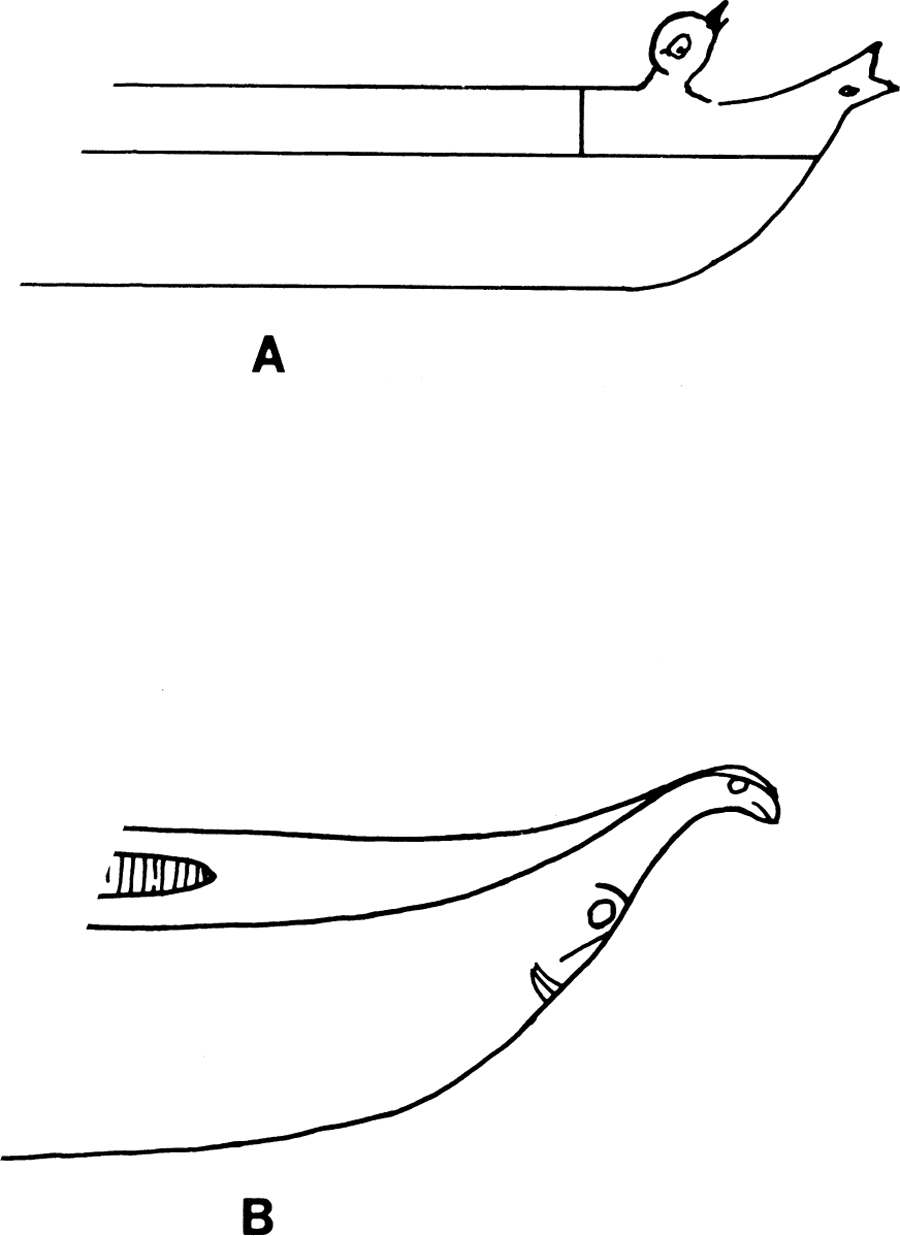

In later times bird-head devices were the hallmark of Roman cargo ships. These were depicted as a long-necked bird-head stern mechanism, usually facing aft (Figs. 8.24–25: D). On occasion, however, this stern device could face forward (Fig. 8.25: G). Together with these naturalistic representations, an abstract form of a horizontal stern bird-head device facing forward also appears (Fig. 8.25: B).53 In the Roman Imperial period, a variety of birds make their appearance as stern ornaments on merchant ships (Fig. 8.25: A, C, E–F).

Figure 8.24. Bird-head stern ornaments on merchant craft (ca. first and second centuries A.D.) (after Casson 1995A:figs. 139, 151, 150, 156, 181, and 146)

Figure 8.25. Bird-head ornaments on merchant craft (ca. third century A.D.) (after Casson 1995A: figs. 147, 179, 147, 147, 149, 148, and 191)

A lesser-known fact is that bird-head devices were also standard on warships of the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, and the Classical period. Furthermore, a strong argument may be presented for identifying these bird-head ornaments as the immediate precursors of two specific devices that appear on Greek and Roman warships: the volute and the aphlaston.

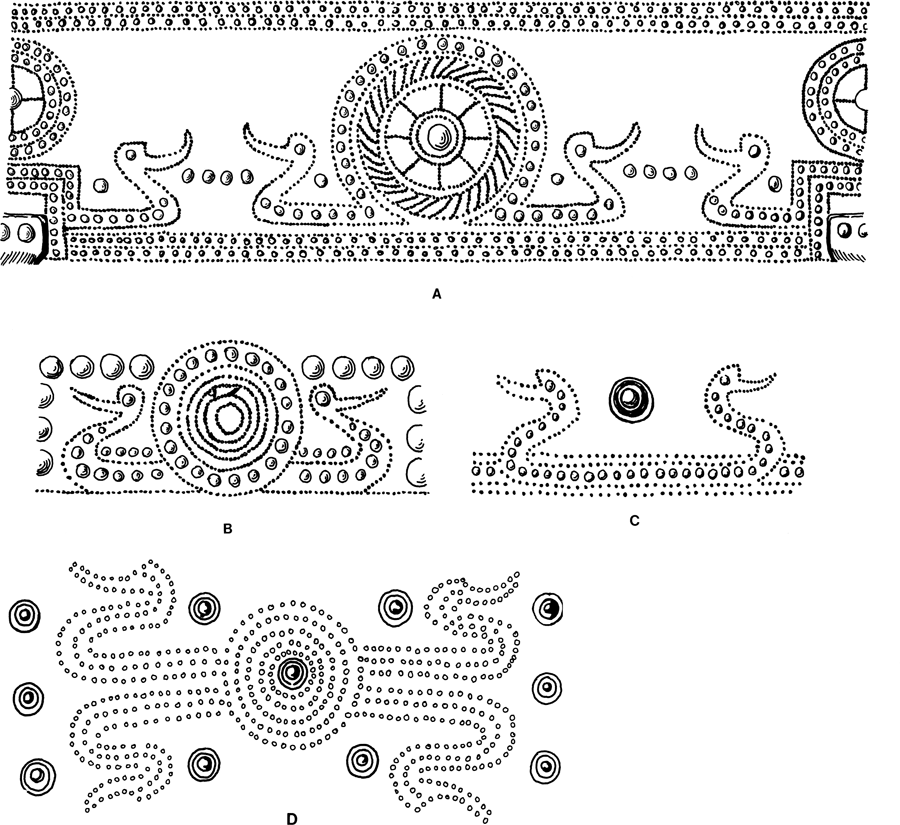

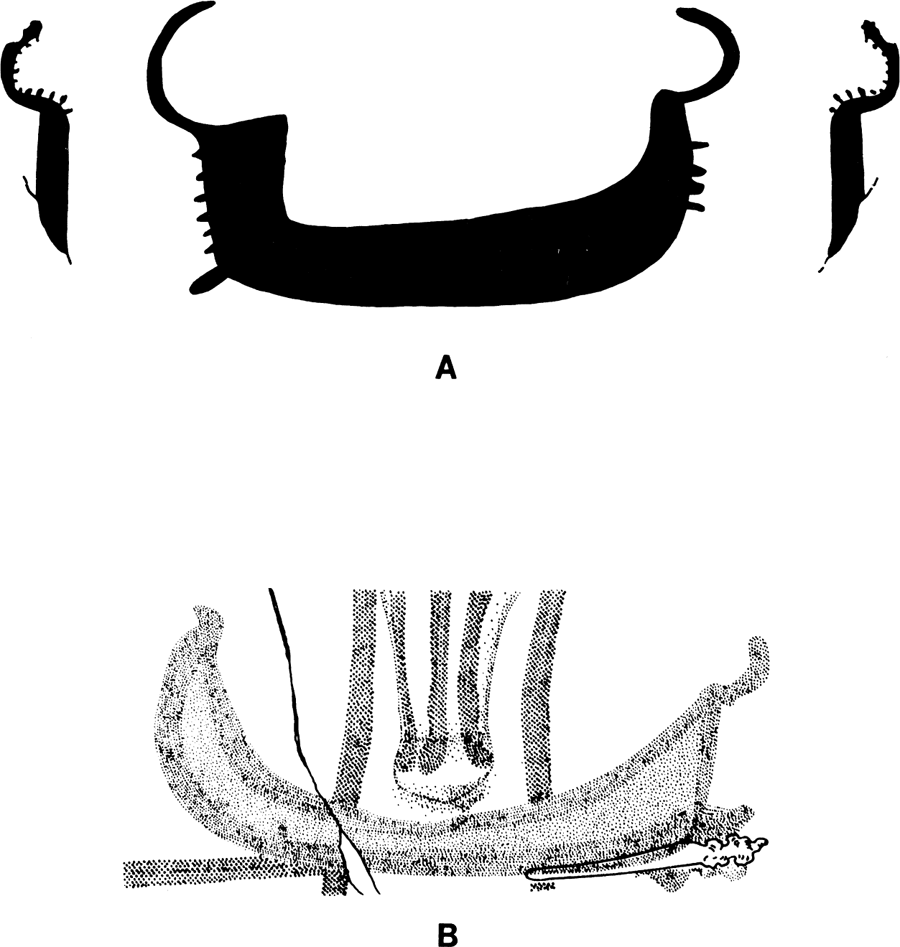

One of the greatest enigmas concerning the Sea Peoples pertains to their origins. The bird-head symbols may be of help in this regard. A connection, though difficult to define, appears to exist between the Sea Peoples and the Urnfield cultures of central and eastern Europe. The possible Sea Peoples’ ship (complete with a bird-head stem device with an upcurving beak) that is depicted on a crematory urn from Hama in Syria seems to support this connection (Fig. 8.19). The manner in which the bird-head ornaments are positioned on the Sea Peoples’ ships at Medinet Habu—facing outboard at stem and stern—invites comparison with the “bird boats” (Vogelbarke) of central Europe, a connection first noted by H. Hencken.54

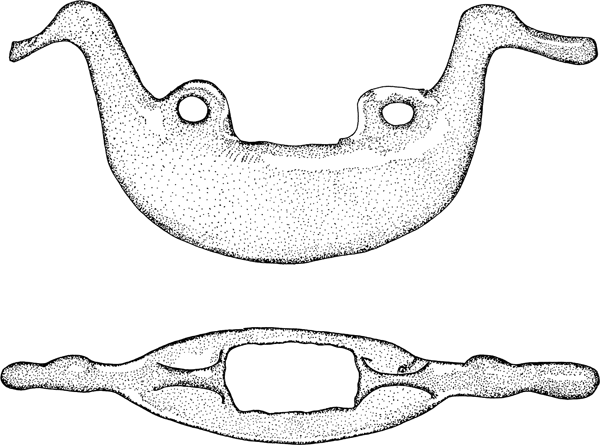

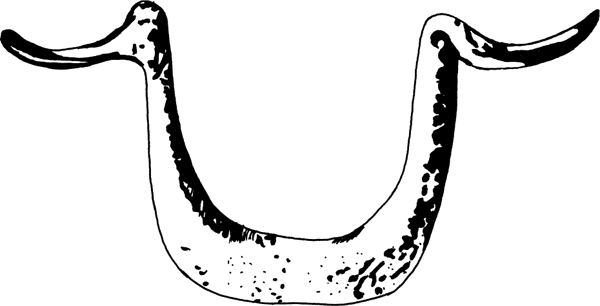

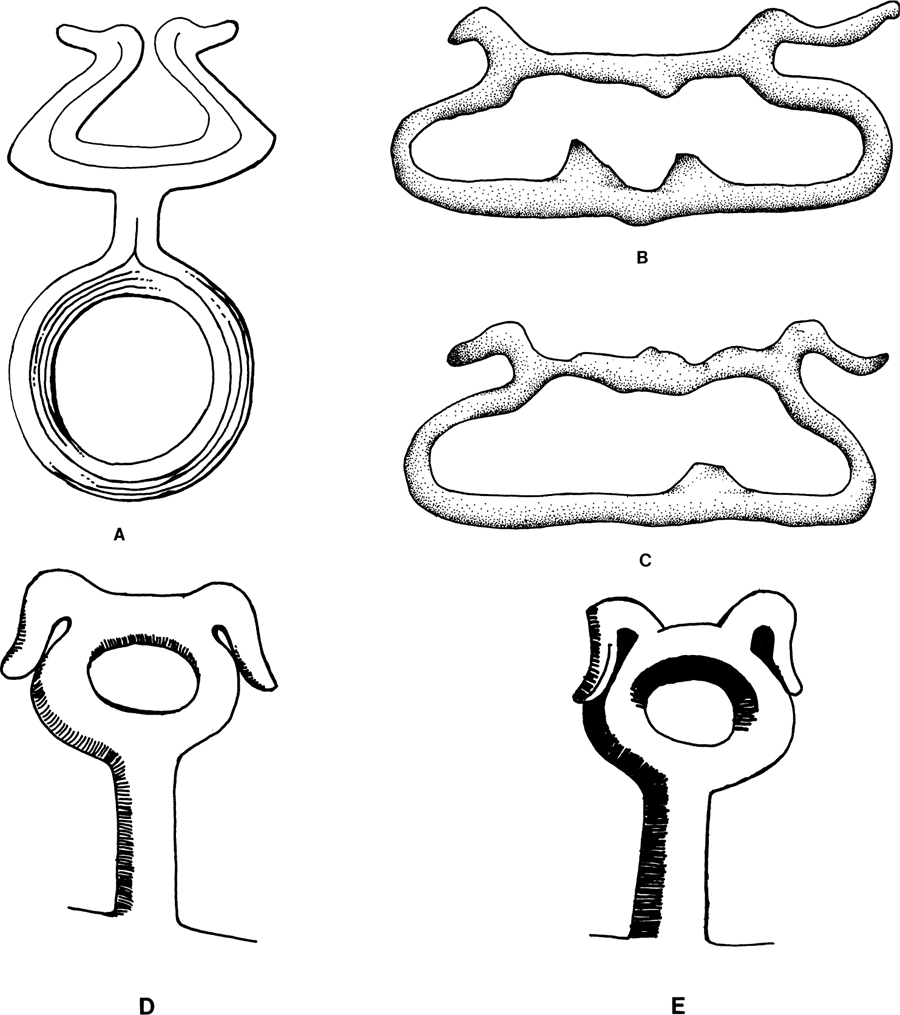

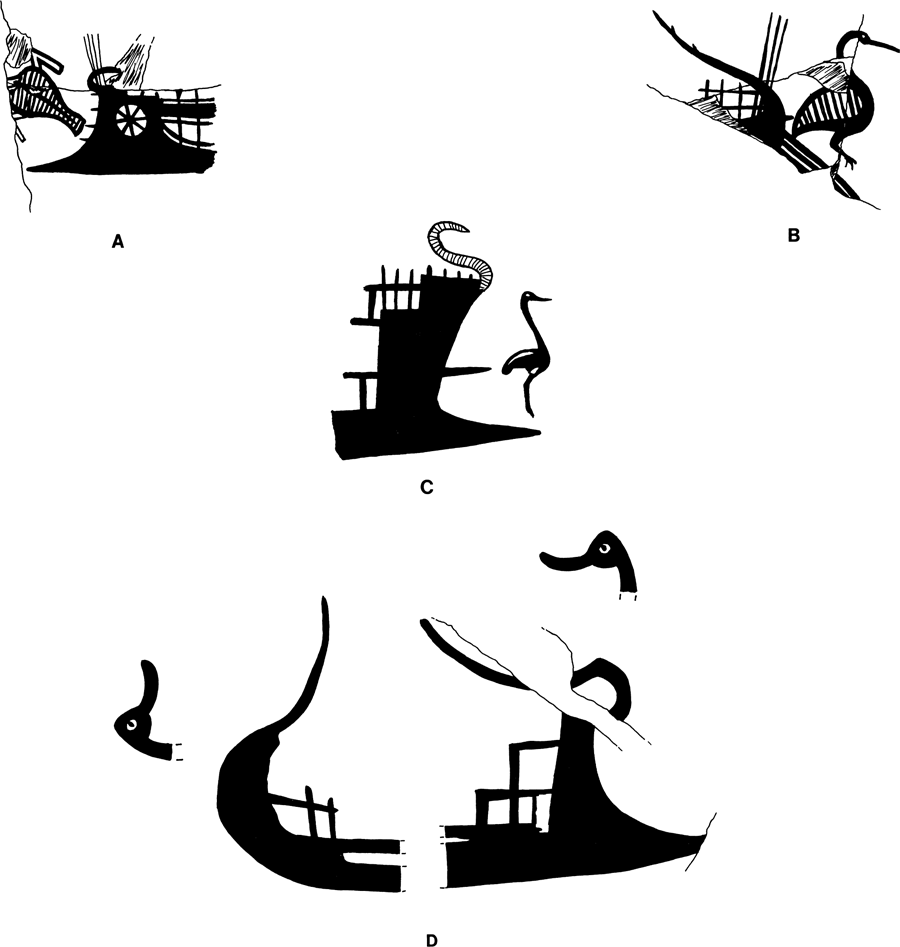

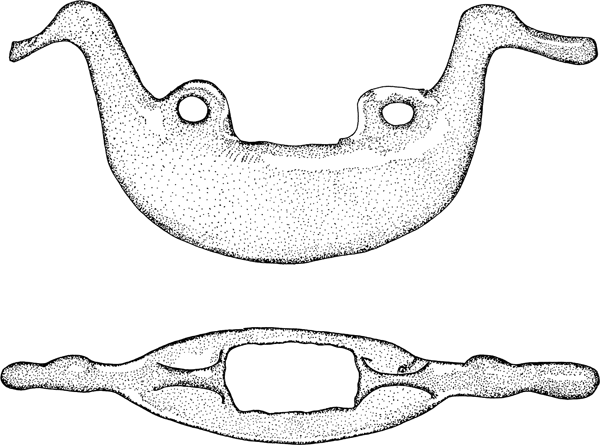

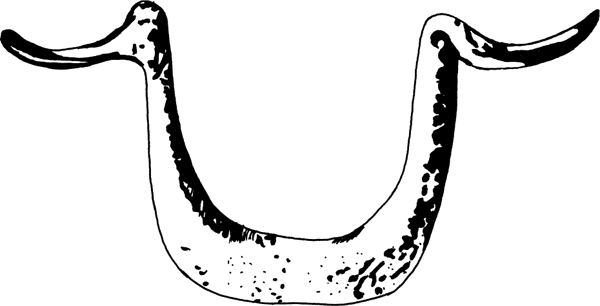

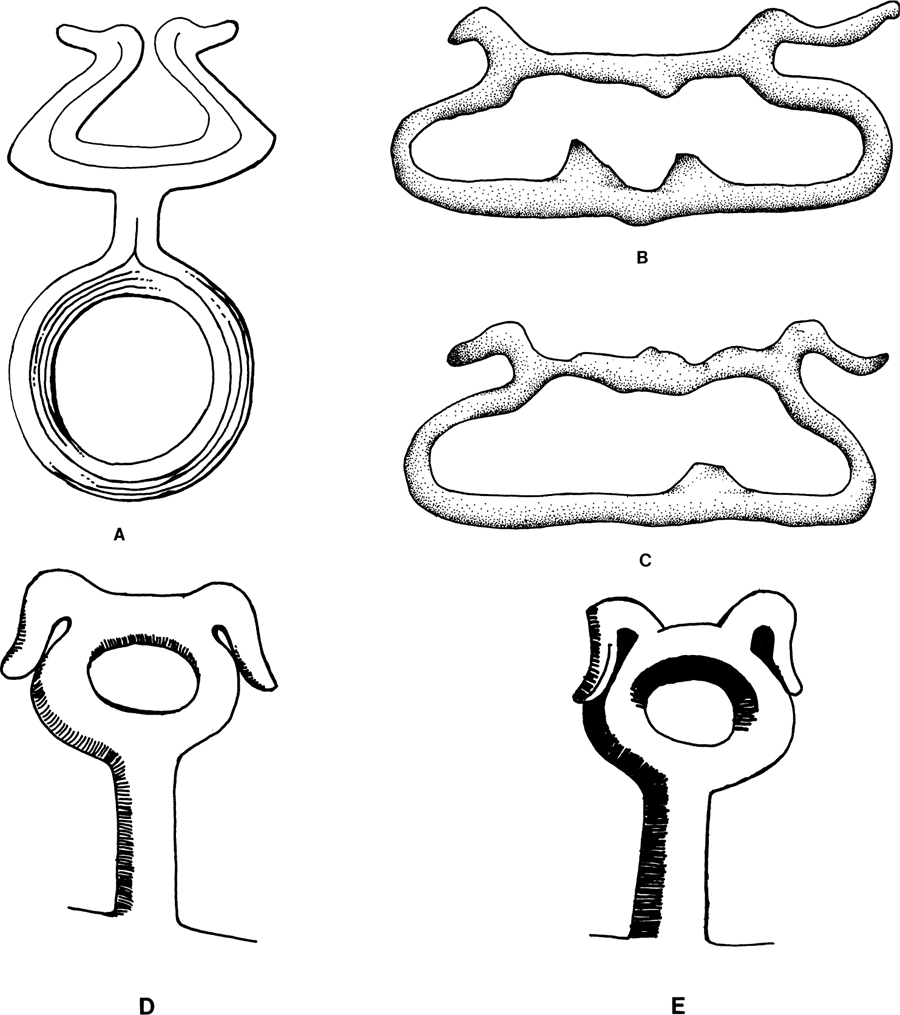

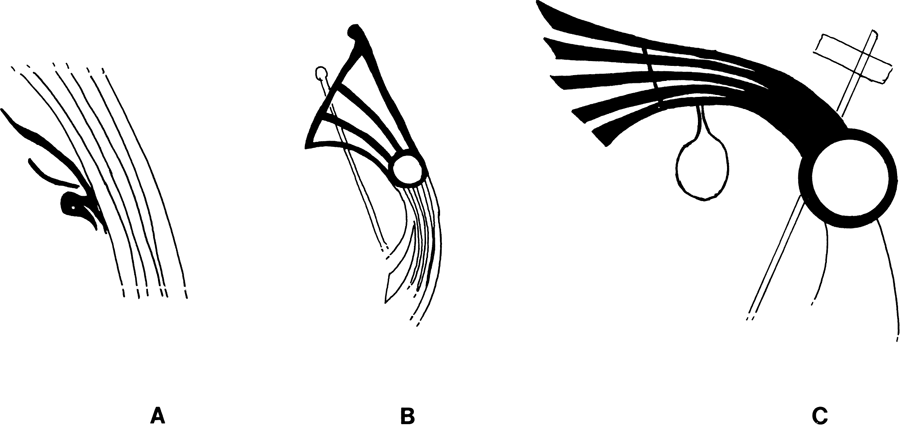

J. Bouzek dates the earliest central European bird boats to the early Bronze D period (ca. 1250–1200 B.C.).55 These are ornaments from the Somes River at Satu Mare in northern Rumania and from Velem St. Vid in Hungary (Figs. 8.26–27). An ornament from Grave 1 at Grünwald, Bavaria, dates to the Halstatt Al period (ca. twelfth century B.C.) (Fig. 8.28: A). The motif continues to appear on Urnfield and Villanovan art (Figs. 8.28: B–E, 29–31). Bouzek suggests that a double bird-headed decoration on a Late Helladic IIIC krater fragment from Tiryns may portray a bird boat, although the painter may not have been aware of what he was depicting (Fig. 8.32).

Figure 8.26. Bronze “bird-boat” ornament from the Somes River at Satu Mare in northern Rumania (European Bronze D [?]) (after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 33: 439)

Figure 8.27. Bronze “bird-boat” ornament from Velem St. Vid in Hungary (European Bronze D [?]) (after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 34: 440)

Figure 8.28. Double-headed “bird boats” in the round: (A) on an ornament from Grünwald, Bavaria (Halstatt A1); (B–C) cheekpieces from Impiccato, Grave 39 (probably Villanovan I); (D) lunate razor-blade handle from Selciatello Sopra, Grave 147 (Villanovan IC); (E) lunate razor-blade handle from Selciatello Sopra, Grave 38 (probably Villanovan II) (after Hencken 1968A: 516 fig. 478: f [after Kossack], 236 fig. 214: b, 105 fig. 92: b, 247 fig. 226 [after Pernier])

Figure 8.29. Bronze ornament from near Beograd (after Bouzek 1985:177 fig. 88: 5)

Figure 8.30. Single and double “bird boats” represented in embossed Urnfield ornament: (A) from Lavindsgaard, Denmark (Halstatt A2); (B) from “Lucky,” Slovakia (Halstatt A2); (C) from Rossin, Pomerania (Halstatt B); (D) from Este, Italy (Este II [= Villanovan II]) (after Hencken 1968A: 516 fig. 478: a, b, e, and g [after Kossack])

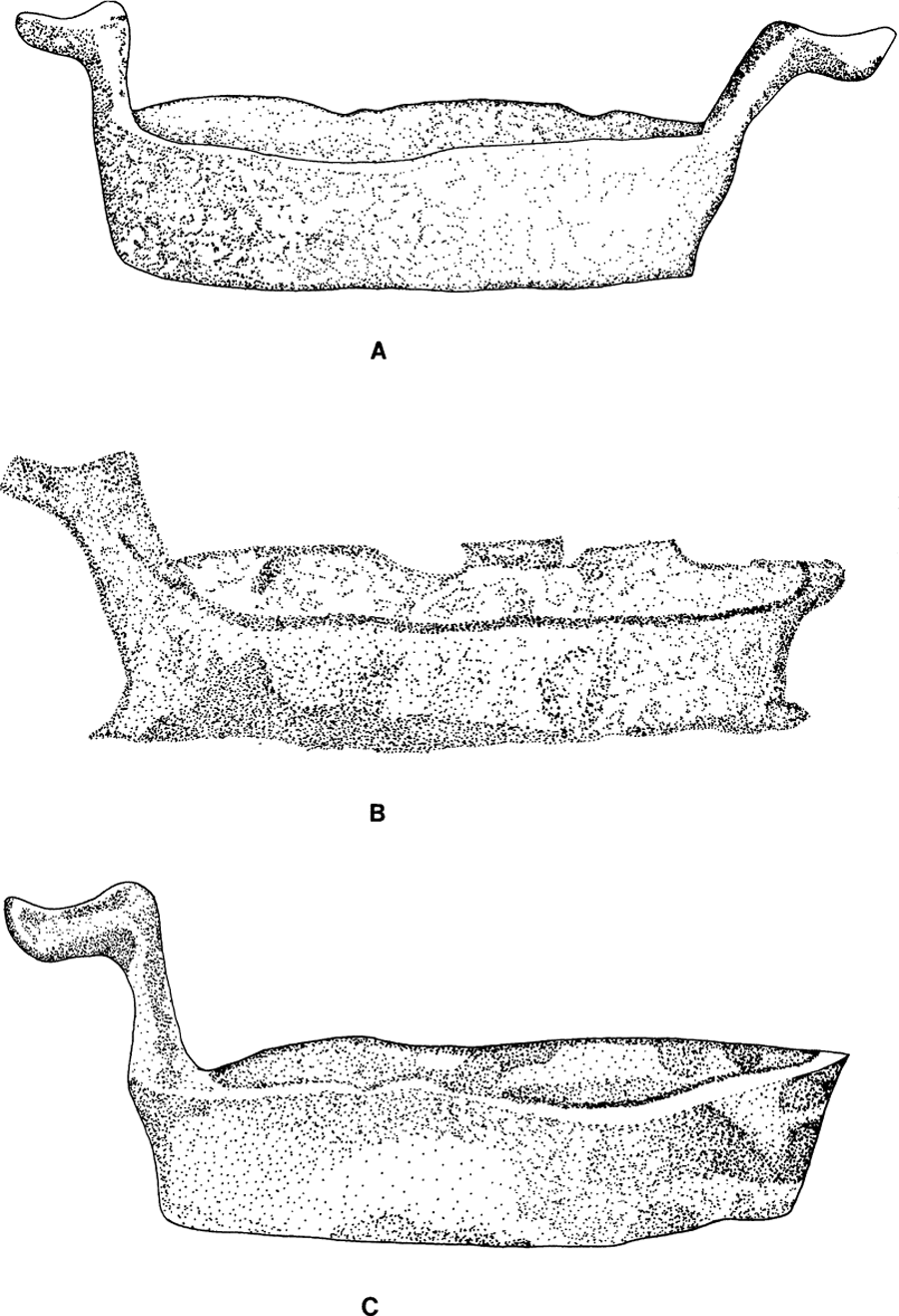

Figure 8.31. Terra-cotta ship models of the Villanovan culture bearing bird’s-head insignia facing outward at stem and stern (A) or at stem alone (B and C) (first half of first millennium B.C.) (from Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 35: 460 [after Montelius], 461 and 469)

Figure 8.32. “Bird boat” painted on a krater sherd from Tiryns (Late Helladic IIIC) (after Bouzek 1985:177 fig. 88: 6)

Figure 8.33. Duck-headed papyrus raft. Tomb of Ipy (T. 217), Ramses II (from Davies 1927: 30; ©, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

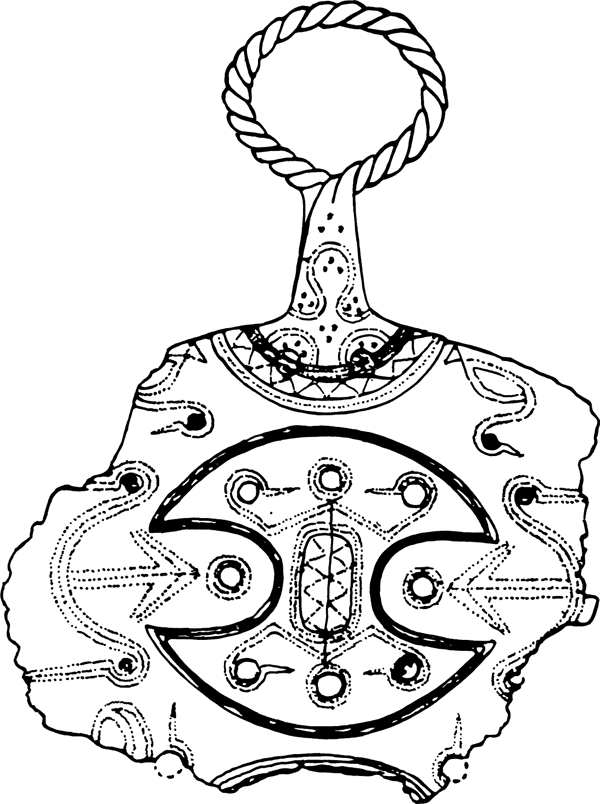

Figure 8.34. (A) Seal with a deity in a boat with bird-head ornaments (Irbid); (B) seal of Elishama, son of Gedalyahu, with motif similar to A (A after Culican 1970:29 fig. 1: d; B after Tushingham 1971: 23)

Figure 8.35. Crested or horned bird-head device on the stem of the Skyros ship depiction (Late Helladic IIIC) (after Sandars 1985:130)

Figure 8.36. Marinatos’s two versions of the stem device on a ship depicted on sherds from the site of Phylakopi on Melos (Late Helladic IIIC) (after Marinatos 1933:219 fig. 10 and pl. 13: 13)

Figure 8.37. Horned animal-bird figures: (A) from Vienna-Vösendorf (Halstatt A); (B) from √i √arovce, Slovakia (Halstatt B or C) (after Hencken 1968A: 521 fig. 480: c, f)

Figure 8.38. Horned bird figure (Greece, provenance unknown, Geometric period) (after Hencken 1968A: 523 fig. 481: f)

Figure 8.39. (A) Bird-head insignia on the stem of a terra-cotta ship model from Monterozzi (Villanovan I–II); (B) crested bird heads on a double-headed bird-boat ornament on a bronze vessel from Impiccato, Grave I (Villanovan IC) (A after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 34: 447; B after Hencken 1968A: 119 fig. 108: c)

Figure 8.40. Birds decorating a bronze girdle from Monterozzi (undated) (after Hencken 1968A: 270 fig. 252: a [after Montelius])

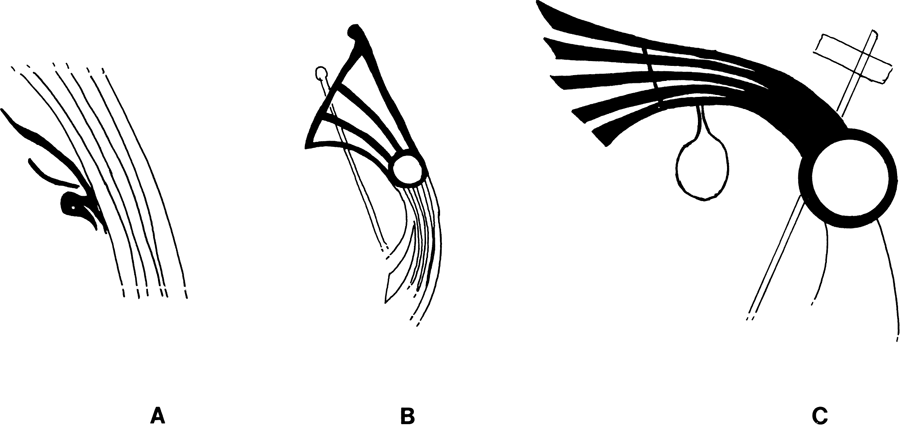

Figure 8.41. Ships depicted on three Cypriot jugs from the seventh century B.C. illustrate the progressive transformation of a naturalistic bird head (A) to a stylized (B) and then abstract (C) sternpost device (after Karageorghis and des Gagniers 1974:122–23 nos. 11:2, 3, 1)

Finally, a possible indication of the influence that the beliefs of the newly arrived Sea Peoples’ mercenaries had on the Egyptians during the Ramesside period is found in the tomb of Ipy. Here he is depicted hunting birds from a papyrus raft with a bird-head stem decoration (Fig. 8.33). Craft similar to bird boats that appear on two Syro-Palestinian seals of Iron Age date portray a god in a boat (Fig. 8.34).56

Several Late Helladic IIIC ship depictions have another element that may be related to European cult iconography. The Skyros ship’s bird-head device has a vertical projection rising from the back of its head (Fig. 8.35).57 A similar projection exists on one of the two drawings given by S. Marinatos for a stem ornament on a ship depiction from Phylakopi, on the island of Melos (Fig. 8.36: A). In the second portrayal, the stem ends in a bird head with an extremely upturned beak identical to the beak of the Skyros ship’s stem device (Fig. 8.36: B).58 This “projection” may represent either horns or a crest on the bird’s head. Horned birds and “animal-birds” are known from later European art (Figs. 8.37–38); bird heads with crests appear in Villanovan art (Figs. 8.39–40).59

The key to understanding the different forms—varying from naturalistic to abstract—in which bird-head devices may be depicted in the Mediterranean itself is to be found on ships portrayed on three Cypriot jugs dating to the seventh century B.C. (Fig. 8.41). On the first ship, A, a naturalistically depicted bird-head ornament, complete with eye, caps the stern and faces inboard. In ship B, the bird’s eye has disappeared, and the head has become stylized. The final, abstract phase appears on ship C, where the sternpost has become little more than a complex curve. Even if this progression is the result of nothing more than the abstraction of the bird head by the artist(s) who created these three ships, the bird-head devices on these vessels show a clear and obvious connection.

Figure 8.42. Ship devices in the form of birds: (A) bird-stem ornament on a ship krater from Enkomi (Late Helladic IIIB); (B) ship’s bird-stem ornament on a pyxis from Tragana (Late Helladic IIIC); (C) bird ornament on the stem of a ship depicted on a Geometric Attic skyphos (ca. 735–710 B.C.); (D) bird ornament portrayed twice on the sternpost of the same ship shown on a Geometric Attic krater (ca. 735–710 B.C.) (A after Sjöqvist 1940: fig. 20: 3; B after Korrés 1989: 200; C–D after Casson 1995A: 30, 65–66)

Figure 8.43. Birds on the stem- and sternposts of an Archaic galley. Note how the shape of the stem device imitates the bird’s head and neck (ca. 700–650 B.C.) (after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 8: d)

This cyclic development of the bird-head ornaments was repeated constantly on ships in antiquity, judging from the iconographic evidence. Natural depictions gave way to stylized representations. These evolved into totally abstract forms that are little more than a complex curve.60 The forms are repeatedly followed by a “rejuvenating” trend to return to the natural rendering of an actual bird’s head.

If only the final, abstract phase of this constantly evolving bird-head form is studied outside of the context of the entire cycle, the curved beak of these Mediterranean vessels may be—and has been—misinterpreted as representing an animal’s horn or other symbolic figure.61 Each phase of this cycle blends into the next, and at times we find two different stages of development on the same ship representation. These bird-head devices may point inboard, outboard, up, or down. On the same ship they can appear at both extremities, as on the Sea Peoples’ ships, or at only one end. The permutations are virtually unlimited.

The evidence for bird-head devices decorating the stem- and sternposts of Mediterranean craft suggests that they originated in the Aegean. The earliest known example of a bird-head ornament is of Middle Helladic date (Fig. 5.25). Ornaments representing entire birds also appear on the stems of ships, beginning in the thirteenth century and continuing down into Geometric times. One such device appears on the stem of a Late Helladic IIIB ship depiction from Enkomi (Fig. 7.28; 8.42: A). The discovery of additional sherds of the pyxis on which it is painted enables G. S. Korrés to demonstrate that the bow device on the Tragana ship—long thought to be a fish—is actually a bird with an upturned beak (Fig. 7.17; 8.42: B).62 These birds and bird-head devices clearly represent the same type(s) of water bird commonly found on contemporaneous Mycenaean and Philistine pottery.63

During the Geometric period, devices in the form of a bird are occasionally affixed to the stem- and sternposts of warships (Figs 8.42: C–D, 50: C). Slightly later, in the Archaic period, birds appear at the bow and stern of a galley (Fig. 8.43). Ornaments in the form of bona fide birds are known both from antiquity (for example, the Minoan swallow device) and from modern ethnographic parallels (Figs. 8.44–46).64 During the Aegean Late Bronze Age the bird/bird-head device was normally stationed on the stem and faced outboard, as, for example, did the devices on the Gazi and the Late Helladic IIIB terra-cotta ship model from Tiryns (Figs. 7.19, 45).

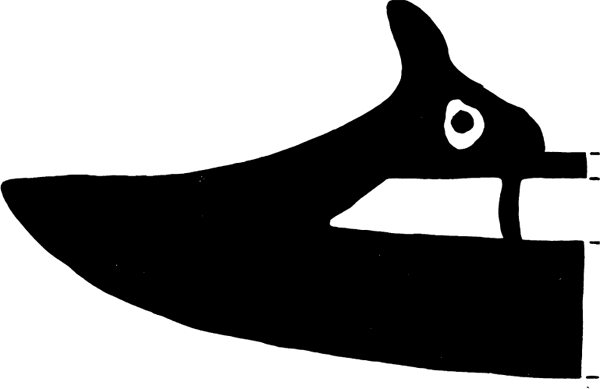

By the twelfth century the number, the direction, and the position of the bird-head devices began to vary on ships. At Medinet Habu they appear for the first time, on a depiction of a seagoing ship, at the stern facing outboard (Figs. 8.8, 10–12, 14, 23). The earliest known bird-head device facing inboard appears on a Late Cypriot III askos/ship model (Fig. 8.47). Two additional and virtually identical askoi in the form of ships also originally had devices topping their stems, but these had been broken off in antiquity (Fig. 7.48). Several of the Kition graffiti have what appear to be abstract bird-head devices (Fig. 7.33: K, M–O, T, V).

Figure 8.44. (A) Stem decoration from Walckenaer Bay, Netherlands Papua; (B) side view of a small canoe with bird device from Papua; (C) ornaments on an Ora canoe from the Solomon Islands; (D) figurehead of an Arab ganja (A-C after Haddon 1937: 317 fig.180: a, 316 fig. 179: c, 88 fig. 59: a; D after Hornell 1970: 236 fig. 46)

Similar bird-head ornaments are known on other terra-cotta ship models as well. A Late Helladic IIIA2 bird-head device topping a post was found at Maroni in Cyprus; it is unclear, however, if this faced inboard or outboard (Fig. 8.48). Another head, of Late Helladic IIIC date, was found at Kynos.65 The latter device has eyes and vertical lines, three of which continue into hanging loops.

During the Proto-Geometric period, the bird’s long, upcurving beak becomes the center of attention. The bird’s head itself virtually disappears, as, for example, on the Fortetsa ships, as well as on a ship painted on a krater from Dirmil, Turkey (Fig. 8.49: A–B).66 This continues a propensity to recurve the device’s beak, a feature that had already become visible in the twelfth century B.C. The Fortetsa devices find their closest parallels on a ship depiction from Kynos (Fig. 7.16; 8.61: C). In Figure 8.49: A, the Kynos devices are placed on either side of the Fortetsa ship for comparison.67

Figure 8.45. (A) Bird-head decorations on a small canoe from Papua; (B) bow of a seagoing outrigger canoe (nimbembew) (southwestern Maleluka, New Hebrides) (after Haddon 1937: 316 fig. 179: a, 22 fig. 12)

Homer, in describing his warships, uses the adjective κορωνίς, which most probably means “having curved extremities.” There is a very similar word, however, which is the name of a seabird: κορώνη. It is quite possible that this is a deliberate play on the two similar words and that κορωνίς is intended to imply “having curved extremities that are bird-shaped.”68

Figure 8.46. Canoes of Atchin, New Hebrides: (A) large seagoing canoe with ordinary, single-beaked solub e res figurehead; (B) coastal canoe with double bird-head solub wok wak figurehead (after Haddon 1937: 27 fig. 15: b, a)

This term accurately describes the stylized/abstract bird-head devices, facing inboard from both the stem- and sternposts, that were popular in the Geometric period. In these ornaments, emphasis was placed on the bird’s beak. The devices on the warship-shaped fire-dogs from Argos are indeed sufficiently naturalistic that the birds’ heads and beaks may be differentiated (Fig. 8.50: A). In other Geometric ship representations, the head-beak has become one continuous curve (Fig. 8.50: B–C). Compare these to the abstract bird-head device capping the stern of the ship in Figure 8.41: C. A naturalistic, regenerating phase of a bird-head stem ornament appears on depictions of galleys dated to the last quarter of the eighth century B.C. (Fig. 8.51).

The stem device on these ships is usually portrayed horizontally and faces backward, toward the stern. A slight angle may differentiate the “head” from the beak (Fig. 8.52: D). More often, the device appears as one continuous compound curve. At times the stem ornament is shown in outline and filled with a hatched decoration (Figs. 8.50: B, 52: C).69 Earlier, this motif appeared on a device from Kynos (Fig. 8.61: D). The stem device on one Geometric galley is interesting in that it begins in an inward-facing abstract bird head but then recurves, copying the neck and head of the long-necked bird that stands in front of it (Fig. 8.52: C). This phenomenon is repeated later on an Archaic bronze fibula (Fig. 8.43).

By the eighth century, the water bird-head device had ceased to be solely a Helladic tradition. A Phoenician warship, portrayed in a relief from Karatepe, has an inboard-facing bird head as a stern device (Fig. 8.53).70 Here, the naturally depicted head, complete with eye, is differentiated from the beak by a vertical line. Approximately contemporaneous with this is an early seventh-century Archaic ship whose stern terminates in a naturalistic inboard-facing bird-head device (Fig. 8.54).71 The beak is spoon-shaped, as if seen from above.

Figure 8.47. Askos in the form of a ship, from Lapithos. A bird-head ornament tops the stem and faces inward, toward the stern (Late Cypriot III) (after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 9: 149)

Figure 8.49. (A) One of two ships depicted on a Proto-Geometric krater from Fortetsa, Crete. The bird-head devices capping the stem- and sternpost are compared to the device on one of the Kynos ships. (B) Ship painted on a Proto-Geometric krater from Dirmil, Turkey (A from Kirk 1949:119 fig. 6; B from van Doorninck 1982B: 279 fig. 3)

Figure 8.48. Bird-head stem (?) or sternpost ornament of a ship model. From Maroni, Tomb 17, Cyprus (Late Helladic IIIA2) (from Johnson 1980: pl. 63: 132)

During the late sixth through fourth centuries, the bird-head stem device is less common on Greek galleys. When it does appear it faces inboard with the beak positioned vertically (Fig. 8.55: A–C). At times the beak is recurved over the bow, replicating a bird-head ornament like that on the Skyros ship placed on its back (Fig. 8.55: B). The devices vary from smooth (Fig. 8.55: A–B) to angular (Fig. 8.55: C). In the latter case, the head is differentiated from the beak. This vertical bird head is rare in later times, although its appearance on a small craft from the second century B.C. reveals that the form is latent but not forgotten (Fig. 8.55: D).

Figure 8.50. Abstract bird-head ornaments in the form of a compound curve topping the stem- and sternposts of representations of Geometric warships (eighth century B.C.) (A after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 25: 338–39; B–C after Casson 1995A: figs. 72 and 65)

During the seventh through fifth centuries B.C., the stern device on Greek warships also undergoes a metamorphosis. The vertical, abstract bird head appears rarely (Fig. 8.56: B). The bird head is now more often portrayed in a naturalistic manner, the eye and beak often differentiated. The heads face inboard and downward but are shortened and recurve strongly, forming the outline of a volute (Fig. 8.56: A, C–D). A progression of Archaic bird-head stern devices illustrates how the volute may have developed from this particular form of bird-head device (Fig. 8.57). In other ships of this time, the bird-head sternpost device adopts a more angular shape and points downwards (Fig. 8.58).

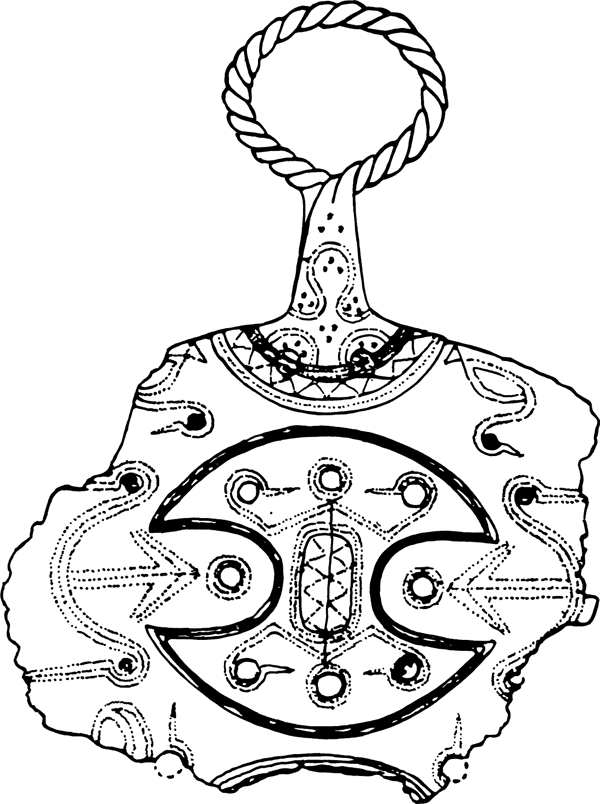

Appearing first in its developed form in the fifth century B.C., the aphlaston became the hallmark of warships in the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. The aphlaston did not leap into existence from a void as Athena came forth from the head of Zeus, however. The aphlaston is best understood as a developed form of an abstract bird head with multiple beaks facing inward from the stern. In the aphlaston, the bird’s eye was enlarged and became the “shield” that normally appears at the base of the aphlaston (Fig. 8.59: B–C). A remarkable ethnological parallel to this phenomenon is seen on a stem device in the form of an abstract frigate bird head used on the Solima canoes of the Solomon Islands (Fig. 8.60).

Figure 8.51. Bird-head stem ornament on a Geometric aphract galley (ca. 725–700 B.C.) (after Casson 1995A: fig. 64)

Figure 8.52. (A) Bird in front of Geometric galley on an Attic krater (ca. 760–735 B.C.); (B) bird behind a Geometric galley on the same krater; (C) long-necked bird before the bow of a Geometric galley. The ship’s stem device copies the shape of the bird’s head and neck (ca. 735–710 B.C.); (D) galley with stem and stern decorations in the shape of abstract bird’s heads (ca. 760–735 B.C.) (A and B after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 2: c–d; C and D after Casson 1995A: 74 and 62)

Figure 8.53. Bird-head stern device on a ship depicted on an orthostat from Karatepe, Turkey (ca. 700 B.C.) (after de Vries and Katzev 1972: 55 fig. 6)

Figure 8.54. Bird-head decoration on an Archaic galley (ca. 700–650 B.C.) (after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 8: b)

Figure 8.55. (A–C) Abstract bird-head stem decorations on Greek warships: A ca. 510 B.C.; B ca. 520–480 B.C.; C ca. 400–322 B.C. The device on ship B is compared to the bird-head device on the stem of the Skyros ship (see Figure 8.42). (D) Abstract bird-head stem decoration ca. second century B.C. (A and C after Morrison and Williams 1968: pls. 20: e, 27: a; B and D after Casson 1995A: figs. 84, 176)

On Geometric galleys, several strake ends sometimes project from the curving stem- and sternposts (Figs. 8.42: D, 50: B–C, 52: B).72 Since this does not result from a technical problem, the planks were evidently left to spring free for a reason. Similarly, in the sixth century, a second, abstract bird head is sometimes shown above the naturalistically depicted one (Figs. 8.56: A, C, 57: B–C, D). Either or both of these phenomena may have led to the introduction of a multiple-beaked bird-head device.

Alternatively, the aphlaston may have derived from the protuberances jutting from the upper or lower edges of the beak and head of the bird-head devices. These items appear first in the thirteenth century on the Gazi ship (Fig. 8.61: A). In the twelfth century they appear on the ship depictions from Tragana and Kynos (Fig. 8.61: B–E). Similarly, in the Enkomi ship the protuberances are found on the inner face of the stem (Fig. 8.42: A). Horizontal lines, apparently representative of the same items, are painted on the stems of terra-cotta models portraying Helladic galleys (Figs. 7.22, 45, 48). In the seventh century B.C., an identical set of protuberances appears on the lower edge of an inboard-facing bird-head device with a highly recurved, vertical beak (Figs. 8.41: C, 62).

Figure 8.56. (A) Bird-head stern decorations on Greek warships (ca. 530–480 B.C.); (B) stern of an Archaic galley on an ivory plaque from the Temple of Artemis Orthia in Sparta (ca. 650–600 B.C.); (C–D) stern decoration on archaic Attic black-figure (C) volute krater and (D) hydria (ca. 600–550 B.C.) (A after Casson 1995A: fig. 90; B–D after Morrison and Williams 1968: pls. 10: d, 11:a, d)

Because of the small size of the depictions, the protuberances comprise little more than lines or dots. Thus, their identity remains uncertain. Perhaps they represent rows of tiny bird-head ornaments affixed to the decorative devices surmounting the posts similar to the one nestling in the crook of a stern ornament on a Greek fifth-century galley (Fig. 8.59: A).

Figure 8.57. Sixth-century B.C. stern decorations on Archaic galleys in the form of a bird’s head develop into an inward-curving stern volute (A–D ca. 550–530 B.C.; E–H ca. 530–510 B.C.; I ca. 510 B.C.) (after Morrison and Williams 1968: pls. 14: g, 13, 14: b, a; 17: d, c, a, e; 18: d)

Why multiply the bird’s beak? This is best understood as a strengthening of the device’s protective power. C. Broodbank, in his study of ships on Cycladic “frying pans,” notes that in primitive societies, the doubling of motifs must be read not as a numerical duplication but as a doubling of the power and attribute of the image.73

Figure 8.58. Sixth-century B.C. stern bird-head devices on Archaic galleys. Note that in C the device has developed into an inward-curving volute (A–B ca. 510 B.C.; C–D ca. 520–480 B.C.; E ca. 530–480 B.C.; F ca. 600–550 B.C.) (A to E after Morrison and Williams 1968: pls. 18: a, b; 21: b, d; 16: c; F after Casson 1995A: fig. 83)

Figure 8.59. Aphlasta on Greek and Roman warships: A ca. 480–400 B.C.; B ca. 200 B.C.; C ca. second century A.D. (A after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 26: a; B–C after Casson 1995A: figs. 108, 114)

Figure 8.60. Bow device of a Solima canoe shaped like an abstract frigate bird and other motifs (Solomon Islands) (after Haddon 1937: 88 fig. 59: b)

Figure 8.61. Bird, or bird-head, devices with many projections, lacking any structural purpose, extending out from the upper or lower surface of the beak. (A) Bird-head on ship painted on the Gazi larnax (Late Minoan IIIB); (B) head of bird device on the bow of a warship depicted on a pyxis from Tragana (Late Helladic IIIC); (C–D) bird-head stem devices on ship depictions from Kynos (Late Helladic IIIC); (E) stem of ship from Kynos. The stem’s upper part has been broken off, but the beginning of a curve and the protuberances on the stem’s inboard side reveal that it was originally capped by a bird head (Late Helladic IIIC) (A after photo by the author; B after Korrés 1989:200; C–E after photos courtesy F. Dakoronia)

Figure 8.62. A row of protuberances appear on the lower (inboard) part of the beak of a bird-head stem ornament of a seventh-century B.C. ship depiction on a jug from Cyprus (after Frost 1963: monochrome pl. 7 (opp. p. 54)

Ethnological parallels from the recent past are useful when trying to understand this phenomenon. Bird-head ornaments were used on the New Hebrides island of Atchin. The large seagoing canoes have devices at both stem and stern (Fig. 8.46: A); the smaller coastal canoes carry the device at the stem only (Fig. 8.46: B). These devices appear in two forms: with a single head or with a double head. A. C. Haddon notes:74

The figurehead (solub) is lashed on the fore end of the hull of the smaller canoes. In the ordinary bird figurehead (solub e res), to which anyone has the right without payment, the slit, representing the mouth of the beak, ends at the first bend [Fig. 8.63: A]. A figurehead in which the slit is continued down the neck is called solub wok-wak [Fig. 8.63: B–C] and the right to this has to be bought from someone already possessing one. When a man gets on in years he feels the need of something superior to a plain solub wok-wak on his everyday canoe. He then goes to one whose figurehead is decorated with a pig or other figure and after having arranged a price one of the parties to the negotiation will make a copy of it. There is a third type (solub war) which resembles the solub wok-wak except that the tip of the under beak is reflected over the upper beak, doubtless to represent a deformed boar’s tusk, hence its name.

Figure 8.63. (A) Single-beaked solub e res figurehead; (B) double bird-head solub wok-wak figurehead; (C) Solub wok-wak figurehead with a pig (after Haddon 1937: 28 fig. 16: a–c)

In the solub wok-wak the single bird head of the solub e res has evolved into two separate bird heads. The multiplication of the beak enhances the value of the solub wok-wak. A similar phenomenon may have taken place in the ancient Mediterranean.

Clearly, these bird-head images were not attached to ships because they were considered aesthetically beautiful but instead for the magical properties with which they were thought to invest the craft.75 The multiplication of the bird’s beak may have been perceived as strengthening the protective magic of the device’s deity.

What significance did the ubiquitous bird-head device, in its many forms, have for the ancient mariner? J. Hornell, in discussing the tutelary deity of Indian ships, describes most clearly the basic need that primitive man felt for a protective presence to guard his craft:

Among Hindu fishermen and seafaring folk in India and the north of Ceylon numerous instances occur indicative of a belief in the expediency of creating an intimate association between a protective deity and the craft which they use, be it catamaran, canoe or sailing coaster. The strength of this belief varies within wide limits; occasionally it is articulate and definite; more often it is vague and ill-defined, often degenerating to a level where the implications of the old ceremonies are largely or even entirely forgotten. In the last category the boat folk continue to practice some fragmentary feature of the old ritual for no better reason than the belief that by so doing they will ensure good luck for their ventures and voyages, a belief usually linked with a dread of being overlooked by the “evil eye.”

Outside of India similar beliefs were probably widespread in ancient times; today shadowy vestiges remain here and there, their survival due mainly to a traditional belief, sometimes strong, sometimes weak, in their efficacy to ensure good fortune or to counteract the baleful glance of the mischief minded.76

Ethnological parallels suggest that devices mounted at the stem and stern were intended to endow the ship with a life of its own. C. W. Bishop, in describing the dragon boats of southeastern Asia, notes that the practice of attaching the carved head (and sometimes the tail) of a dragon to these craft before ceremonial races originates in the belief that the devices magically transformed the boats into the creatures they represent.77

This concept of the ship having a life of its own is illustrated by a ceremony reported by Hornell.78 The Hindu ships that traded between the Coromandel Coast and the north of Sri Lanka had oculi carved on either side of the prow. The final rite before launching a new ship was termed “the opening of the eye.” This was meant to endow the boat with sentient life and constituted it the vehicle of the protective goddess. The goddess would then live in and protect the ship during sea voyages. The protective entity was thus installed in the craft, her individuality being merged with it. In India the shielding deity is nearly always feminine. Hornell writes, “By this association of the boat with a female deity, the identity and sex of the protectress are merged with those of the boat itself; as we may infer that many other peoples have reasoned and acted similarly, this may explain the fact that ships are generally considered as feminine.”79

Figure 8.64. Bronze razor in the abstract form of a female idol. The head is formed by the razor’s handle; the neck is decorated. Embellishments include a double-ax decoration, water birds, and anthropomorphic figures with arms and legs formed from “bird boats” (from Italy, provenance unknown) (after Bouzek 1985: 216 fig. 103:11)

Of particular interest in this regard is a Proto-Villanovan Type O European bronze razor from Italy, dated to about the ninth century B.C. (Fig. 8.64). The razor, of unknown provenance, is in the abstract form of a female idol. Its head is formed by the handle of the razor; the neck is decorated. A double ax (?), serving as a central motif, is decorated by a mirror-image figure with arms formed of bird boats with inward-facing bird heads.80 Additional figures are positioned within the two cavities of the double ax. These have legs made of bird boats with outboard and downward-facing bird heads. Four additional water birds nestle at the corners of the figure.81 In this case the symbolism strongly suggests that the bird boat is symbolic of a goddess.

It seems likely, therefore, that the duck represents a female deity.82 It may be argued, however, that this motif embodies an even greater symbolic realm. M. Yon notes:

The duck (this is of course the wild duck, not the farmyard animal) contains in itself a multiplicity of symbols: it is at the same times terrestrial, aerial, aquatic, as it walks, flies and swims. . . .

F. Poplin has shown the tight relationship in our imagination of «the horse, the duck, and the ship», as more or less conscious variations of means of transport; equines, palmipeds and boats come together and replace each other in languages (Homeric expressions or modern slang) as well as fantastic narrative (the swan of Lohengrin, or the geese of Nils Holgersson) and in plastic representations (fountain of Bartholdi at Lyon, or arm-rests on Hellenistic and Roman beds). The symbolic equivalence thus appears ancient; that which interests us here is its presence in the European world at the end of the Bronze Age, when it passed to the eastern Mediterranean with the population movements which marked the end of the second millennium.

Moreover, the duck is a migratory bird, appearing and disappearing each year. As such it is a symbol of renaissance and fertility, reinforced by the connection with water, from which life comes forth. . . .

It becomes part of an ensemble of beliefs and of a symbolism which links cultural groups apparently as diverse as the peoples of central Europe where palmipeds live in misty marshes, the <<Sea Peoples>> who came from the north as do the wild ducks, and the islands of the eastern Mediterranean such as Cyprus or Crete where the new population of this period placed in their tombs representations of the animal which symbolized their voyage and their vital force.83

Bird-head devices continued in use into the latter part of the sixth century A.D., when a Nile vessel is described as “wild-goose-sterned.”84 Presumably they did not cease at that time, however. Indeed, decorative devices reminiscent of bird heads and bird boats are still found on present-day craft.

Figure 8.65. Stern devices on modern Greek boats at Ayia Galini, Crete (photos taken in 1980 by the author)

In Greece, devices capping the sternposts of some fishing boats are sometimes shaped like a bird head (Fig. 8.65: A). On occasion, the “beaks” of these ornaments are multiplied in a manner reminiscent of the aphlaston (Fig. 8.65: B). Similarly, “bird boat”–like ornaments have been recorded in this century on Indian craft, as witnessed by Hornell’s drawing of the decorated bow of a Ganges River cargo boat at Benares (Fig. 8.66). The same design in a degenerated form is found on the bow of a kalla dhoni recorded at Point Calimere, South India (Fig. 8.67). The relationship, if any, of these modern decorative motifs to the bird-head devices of antiquity remains to be determined.

Figure 8.66. (A) Decorated bow of Ganges River cargo boats, Benares; (B) detail of inverted bird boat-like ornament (from Hornell 1970: 279 fig. 68 [J. Hornell, Water Transport, Cambridge University Press, 1946])

Figure 8.67. (A) Bow of a kalla dhoni with an abstract bird boat-like ornament (Point Calimere, South India); (B) detail of the ornament (from Hornell 1970: 272 fig. 67 [J. Hornell, Water Transport, Cambridge University Press, 1946])

Finally, what are we to make of this curious ship, sighted and described by W. J. Childes in this century?

A sight of this kind I watched one summer evening on the coast of the Black Sea, when a long boat, whose bow was shaped like a swan’s breast, put off from the shore. Her stern projected above the hull and was curved into a form resembling roughly the head and neck of a bird preparing to strike. Upon the mast, hanging from a horizontal yard, was set a single broad square-sail, and under the arching foot could be seen the black heads of rowers, five or six men on either side, and a barelegged steersman placed high above them in the stern.85