go . . . If [you can find a ship] to transport me, let me be taken back to Egypt. And I spent twenty-nine days in his h[arbor while] he daily [spent] time sending to me, saying: Get out of my harbor!

go . . . If [you can find a ship] to transport me, let me be taken back to Egypt. And I spent twenty-nine days in his h[arbor while] he daily [spent] time sending to me, saying: Get out of my harbor!The Ships of the Syro-Canaanite Littoral

The Iron Age Phoenicians are considered the seafaring merchants par excellence of the ancient world. This is largely because of the respect the Classical Greeks held for them as merchants and seafarers. But the Phoenicians were not new to the sea; their Syro-Canaanite ancestors had already come to know the Mediterranean intimately.1

The Textual Evidence

T. Säve-Söderbergh, in lauding Egyptian Mediterranean involvement, leaves little room for the Syro-Canaanites. At the same time, J. D. Muhly downplays the role of the Syro-Canaanite sea traders of the Late Bronze Age, arguing that Homeric references to Phoenicians in Mycenaean Greece must represent an Iron Age reality.2 A significant role for Syro-Canaanites in maritime mercantile trading during the latter part of the Late Bronze Age was first proposed by G. F. Bass on the basis of the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck and Egyptian iconographic evidence and by J. M. Sasson based on the Ugaritic texts. The many texts dealing with maritime matters found in Ugarit, as well as in Egypt, indicate an intense level of involvement in maritime trade by the Syro-Canaanite city-states among themselves and with other lands and cultures.3

Despite long-standing assumptions to the contrary, Homeric references to Phoenician (Syro-Canaanite) sea traders in Mycenaean Greece are entirely compatible with Late Bronze Age realities.4 A review of the following textual, archaeological, and iconographic materials indicates that the Syro-Canaanites were particularly active—although most certainly not alone—as sea traders in the Late Bronze Age and possibly earlier.

In addition, it is important to emphasize that this seagoing trading ability did not translate into political power. Recent studies indicate that Canaan—modern-day Israel and Southern Lebanon—was politically and financially impoverished during the Late Bronze Age, when Syro-Canaanite sea trade was at its height.5 The Syro-Canaanites, including the major trading “power” of Ugarit, did so at the pleasure of their Egyptian or Hittite overlords.6 Thus, terming Ugarit—or any other Late Bronze Age Syro-Canaanite city-state, for that matter—a “thalassocracy” is a misinterpretation of the evidence.7 The Syro-Canaanites did not “rule the waves.”

Most textual references to their ships refer specifically to heavily laden merchantmen with rich cargoes. During his expulsion of the Hyksos from Avaris, Kamose describes the capture of numerous Hyksos ships in which he found a wealth of trade goods.8 This is the earliest known reference to trading ships definitely owned, and presumably constructed, by Syro-Canaanites: “I have not left a plank under the hundreds of ships of new cedar, filled with gold, lapis lazuli, silver, turquoise, and countless battle-axes of metal, apart from moringa-oil, incense, fat, honey, itren -wood, sesedjem -wood, wooden planks, all their valuable timber, and all the good produce of Tetenu. I seized them all. I did not leave a thing of Avaris, because it is empty, with the Asiatic vanished.”9

Thutmose III supplies the next description of Syro-Canaanite ships when he describes his capture of two cargo-laden Syro-Canaanite merchantmen during his fifth campaign (year twenty-nine; 1450 B.C.): “Now there was a seizing of two ships, . . . loaded with everything, with male and female slaves, copper, lead, emery, and every good thing, after his majesty proceeded southward to Egypt, to his father Amun-Re, with joy of heart.”10

The Amarna texts shed light on the Syro-Canaanite maritime trade in the mid-fourteenth century. Ships of Arwad and Ugarit are mentioned visiting Egypt.11 Aziru promises to send his messenger, along with gold and various implements, to the pharaoh by ship.12 The ship referred to presumably belonged to Aziru; i.e., it was Syro-Canaanite. Elsewhere, Biridiya of Megiddo reports that Surata of Acco has taken Labaia and has promised to send him by ship to Egypt.13

Documents from Ugarit contain references to traders from Arwad, Byblos, Beirut, Tyre, Acco, Ashdod, and Ashkelon stationed at Ugarit; these indicate significant interstate trade along the Syro-Canaanite coast.14 One Ugaritic ship was wrecked in a storm near Acco while on a voyage to Egypt; another text mentions a ship that was lost (sank?) with a cargo of copper.15 Idrimi, in relating the story of his life, tells how, after living among the Habiru for seven years at Ammiya, in the mountains above Byblos, he had ships built (at Byblos?) for his nautical invasion of the land of Mugisse, thus gaining the throne of Alalakh.16

Ugarit’s fleet just before its fall is impressive by any measure. One text refers to 150 ships that are to be dispatched.17 In another, the Hittite king notifies “his son”—a vassal ruler or official—of the arrival of a hundred ships loaded with grain.18 A third text indicates that during the Late Bronze Age, Syro-Canaanite ships were reaching—and being taxed—for voyages to the Aegean.19

The exchange of foreign words and personal names may also suggest contacts, although their meaning and significance are unclear. The name Turios appearing in the Linear B texts may indicate a connection with the city of Tyre.20

Several condiments listed in the Linear B tablets have Semitic names: cumin, kupairos, and sesame seed.21 An unidentified “Phoenician” spice appears on two Linear B texts at Knossos.22 Three other Semitic terms appear as loan words: ki-to (garment), ku-ru-so (gold), and re-wo (lion).23

The intensity of Late Bronze Age Syro-Canaanite sea trade continued right up to the time that the barbarians were literally at the gates of Ugarit. Some tablets were found adjacent to the “southern archive” in a kiln, in which they were being baked when Ugarit was destroyed.24 Thus, they must date to the very last days of Ugarit. The tablets reveal a vibrantly active commercial entity, seemingly oblivious to the impending doom.

By the eleventh century, in the aftermath of the migrations that toppled the Late Bronze Age cultures, Egypt lost its political and nautical control over the Levantine coast.25 Now Syro-Canaanites, perhaps together with the Sea Peoples as well, controlled the maritime trade between Egypt and the Syro-Canaanite coast.

When Wenamun arrived at Byblos, it was on a Syro-Canaanite (Phoenician) ship. This is evident from an argument in which Wenamun claims to have arrived on an Egyptian vessel. However, Tjekkerbaal, the king of Byblos, knew better.26 Wenamun’s comments may also allude to the frequency of ships on the Byblos-Egypt run. When he first arrived in the port, Tjekkerbaal ordered him to leave. Notes Wenamun:

And I sent (back) to him saying: Where should [I go]? . . .  go . . . If [you can find a ship] to transport me, let me be taken back to Egypt. And I spent twenty-nine days in his h[arbor while] he daily [spent] time sending to me, saying: Get out of my harbor!

go . . . If [you can find a ship] to transport me, let me be taken back to Egypt. And I spent twenty-nine days in his h[arbor while] he daily [spent] time sending to me, saying: Get out of my harbor!

Now when he offered to his gods, the god took possession of a page (from the circle of) his pages and caused him to be ecstatic. He said to him: Bring [the]  up. Bring the envoy who is carrying him. / It is Amun who dispatched him. It is he who caused him to come. For it was after I had found a freighter headed for Egypt and after I had loaded all my (possessions) into it that the possessed one became ecstatic during that night, (this happening) while I was watching for darkness to descend in order that I might put the god on board so as to prevent another eye from seeing him.

up. Bring the envoy who is carrying him. / It is Amun who dispatched him. It is he who caused him to come. For it was after I had found a freighter headed for Egypt and after I had loaded all my (possessions) into it that the possessed one became ecstatic during that night, (this happening) while I was watching for darkness to descend in order that I might put the god on board so as to prevent another eye from seeing him.

The harbor master came to me, saying: Stay until tomorrow, so the prince says. And I said to him: Are you not the one who daily spends time coming to me saying: “Get out of my harbor!”? Isn’t it / in order to allow the freighter which I have found to depart that you say: “Stay tonight,” and (then) you will come back (only) to say, “Move on!”? And he went and told it to the prince, and the prince sent to the captain of the freighter, saying: Stay until tomorrow, so the prince says.27

Wenamun worried, lest he miss his ship and have to wait some time for another opportunity. In a later conversation with Tjekkerbaal, Wenamun refers again to waiting in the harbor of Byblos for twenty-nine days.28 H. Goedicke suggests that the time periods mentioned by Wenamun may be a literary device.29 He notes that twenty-nine days is one day short of a month, as the nine days Wenamun spent at Dor are one day short of a decade; thus, a solution arriving on the last day of a time unit might be meant to convey something happening “at the last moment.” Even if this is correct, it is apparent that ships were not departing daily from Egypt to Byblos.

SHIP SIZES. KTU 4.40 lists the crews of three ships.30 E. Linder notes that this must refer to rowing crews and points out the similarity with Linear B text An 1.31 One ship, that of Abdichor, has a complement of eighteen crewmen recruited from three different locations. The crews of the two other ships listed on the tablet are damaged but may be reconstructed as containing eighteen men each. KTU 4.689 contains a list of ship’s gear.32 Included in the inventory are nine oars or nine pairs of oars. If the term used here for oars, mṯṭm, is indeed in the dual form, then the eighteen oars correspond to the crew of Abdichor’s ship—assuming, that is, that each oar was pulled by a single rower.

Taken together, these texts suggest that a type of Ugaritic ship—we cannot determine which specific type as in both cases only the general term for ship (any) is used—had a rowing crew of eighteen oarsmen, nine to a side. Each rower would require a minimum interscalmium of about one meter. At the very least, an additional three meters in the bow and four in the stern would have been required to bring the hull planking in toward the posts.33 Thus, a conservative estimate of the length of such a ship is fifteen to sixteen meters.

One text unearthed at Ugarit has been considered evidence for exceptionally large Syro-Canaanite seagoing trading ships. In it, the Hittite king requires the king of Ugarit to supply a ship for the transshipment of two thousand measures of grain from Mukish to Ura.34 J. Nougayrol notes that the measurement referred to must be the kor; this calculates to a total burden of 450 tons.35 Until recently, a tonnage of this size before the Roman period seemed excessively large. However, the recent discovery and excavation of a large merchantman from the early fourth century B.C., with an estimated length of twenty-six meters and beam of ten meters, require a revision of this assumption.36

How far back in time can this “gigantism” in merchant ships be traced? The technological knowledge to build ships of this size existed in the Late Bronze Age; an example was Hatshepsut’s obelisk barge. Furthermore, the half-ton anchors found at Ugarit, Kition, and in the sea argue for Late Bronze Age ships of considerable tonnage, particularly considering that these vessels normally carried quantities of anchors.37

On the other hand, if traders of these proportions were being built in the Late Bronze Age, their use would have been problematic given the lack of harbor facilities that could have accommodated them along the coast of the Levant. Perhaps the writer of the text intended a form of grain measurement smaller than the kor.

The Archaeological Evidence

At the beginning of the Dynastic period, a number of strikingly Mesopotamian influences appeared in Egypt. Scholars have long believed that the Nile was invaded at that time by a seaborne migration.38 The invasion route, it was argued, followed the Persian Gulf to the Red Sea, and the migrants entered the Nile valley by way of the Wadi Hammamat.

Considerable evidence now indicates that this contact came by way of the Mesopotamian trading colonies that existed in North Syria during the Late Uruk period and that these people must have arrived in Egypt by ship, for no evidence of their cultural equipment exists in Lebanon and Israel.39 It is difficult to determine which, if any, of the many ship images preserved in Egypt from that period may depict the seagoing ships that carried these immigrants.

Concerning Syro-Canaanite seafarers in the latter part of the Bronze Age, A. Yannai has pointed out the possible significance of the appearance of Levantine Bronze Age smiting-god statuettes found in the Aegean, often in connection with shrines and sanctuaries. She writes:

Firstly, there is no doubt that the figurines have a religious significance. . . . Secondly, the Smiting-god is the only Levantine deity known from the Aegean, although a great variety of divinity figurines, male, female, coupled, seated and so forth are known from the Levant including Cyprus. Thirdly, they do not appear to have occasioned imitation in the Aegean.

An interpretation of the appearance of these votive figurines, like most problems involving religion, is speculative. It is nevertheless tempting to suggest that if the Smiting-god figurines indeed represent Resheph, and that god is connected with uncontrollable disasters which storms at sea most certainly are, and on at least one occasion he is mentioned with tempestuous waters, the god would be a likely candidate to protect seamen. Could then the figurines found in the Aegean be thank-offerings, presented by seamen for a successful voyage? In any case, their origin can again be as likely in Cyprus as further east.40

Recent discoveries support Yannai’s conclusion. A smiting-god is depicted next to the ship on the Tell el Dabca seal, and a female statuette of apparent Syro-Canaanite origin, on the shipwreck off Uluburun, Turkey, may have been the ship’s tutelary image.41

The Iconographic Evidence

Egypt

TELL EL DABCA. A Syrian cylinder seal from the eighteenth century B.C. found at Tell el Dabca in the eastern Nile Delta bears a representation of a ship, perhaps not unlike those captured two centuries later by Kamose (Fig. 3.1).42 The site, identified as the Hyksos capital of Avaris, contains significant Middle Bronze Age II Syro-Canaanite material cultural remains.43 Porada believes the seal is a copy of an actual Syrian cylinder seal made by a local seal engraver. Next to the ship is a Syro-Canaanite smiting weather god, similar to those discussed above. Porada, echoing Yannai’s comments, notes that the god’s proximity to the ship may identify him as a guardian of mariners.

The ship’s hull is crescentic; one extremity curves gently outward while the other is vertical. The mast is positioned amidships. From the masthead fore and aft stays extend diagonally to the bow and stern. The heads of two figures are visible, one on either side of the mast. Two oars are positioned beneath the hull, adjacent to the figures.

TOMB OF KENAMUN. The tomb of Kenamun (T. 162) at Thebes contains the most detailed known scene of Syro-Canaanite ships (Figs. 3.2–6).44 The deceased was the “Mayor of Thebes” and “Superintendent of the Granaries” under Amenhotep III.45

The scene is divided into three parts. The left third of the scene is a single register with four ships (Figs. 3.3–4). In the scene’s center are two registers with seven ships docked at an Egyptian port (Figs. 3.5–6). To the right, the frenetic activities of shore trade are illustrated in three registers (Fig. 14.6).

Figure 3.1. Ship on a Syrian cylinder seal from Tell el Dabca (eighteenth century B.C.) (after Porada 1984: pl. 65:1)

Although Syro-Canaanite ships were probably reaching Thebes at the time that the scene was painted, the artists lacked actual knowledge of the ships themselves. Kenamun’s scene was probably copied from stock scenes.

Figure 3.2. A tableau of Syro-Canaanite ships arriving in Egypt depicted in the tomb of Kenamun (T. 162) at Thebes (Amenhotep III) (from Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

An understanding of the sources available to the Egyptian artist and of the mechanics involved in the decoration of Egyptian tombs is a necessity, if only to correctly interpret the ships appearing in the tombs. The Theban tombs exhibit numerous cases of scenes and details so similar in context that some form of relationship must have existed between them. There are two possibilities: either artists visited and copied earlier tombs or sets of original drawings existed, collected in some form of “pattern” or “copy”-books. It is possible to demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt that copybooks were indeed used in the creation of wall paintings in the Theban tombs during the Eighteenth Dynasty. If so, the artist(s) who painted the ships in Kenamun’s tomb was at least once removed from his subject.46

Figure 3.3. Detail of the ships in the left third of the register (from Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

Figure 3.4. Detail of the deck area and rigging of a large ship on the left of the Kenamun scene (from Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

Figure 3.5. Detail of the ships at the upper center of the Kenamun scene (from Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

Figure 3.6. Detail of the ships at the lower center of the Kenamun scene (from Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

The ships are depicted with crescentic hulls and with a particularly severe—perhaps exaggerated—sheer.47 The vessels at the upper center have the most detailed hulls. The ship nearest the viewer has three strakes delineated with two butt joints: one between the stem finial and the hull, the other between two planks in the middle strake (Fig. 3.5). Butt joints are also visible between the stempost and the hull on the four other ships staggered behind it.

Some ships carry lacing along the sheer (Fig. 3.5). R. O. Faulkner believes this lacing ran the entire length of the ship, as in Sahure’s seagoing ships.48 But similar lacing, positioned at the extremities of the craft, are known from Middle Kingdom wooden ship models.49 Therefore, this is best understood as an additional Egyptianizing element introduced by the artist, as, perhaps, are the single rows of through-beams (Figs. 3.5–6).

The stem- and sternposts are vertical with a slight external hollow. The posts’ tops are flat or concave.50 Because of Egyptian artistic conventions, it is not clear if they are portrayed frontally or in profile.51 Vertical stemposts are known from New Kingdom Egypt on Hatshepsut’s seagoing Punt ships as well as on river craft.52 However, none of these have vertical sternposts. As noted above, vertical posts at stem and stern with straight outer and curving inner faces appear on Old Kingdom seagoing and cargo ships (Figs. 2.2–3, 5, 8, 9).

A screen runs the length of the ships at the sheer. The Uluburun ship seems to have had a wickerwork and post screen of this type.53 Two rudders with short tillers are hung over the quarters.54 There are no stanchions, but these must have existed on the actual ships to support the looms.

Säve-Söderbergh, Norman de Garis Davies, and Faulkner consider the ships in Kenamun’s tomb to be Egyptian vessels.55 This conclusion results partially from the many Egyptianizing hybrid elements that the artists infused into the ships.56 The following compelling considerations indicate that the ships depicted in the tomb of Kenamun are Syro-Canaanite:57

• The ships’ crews are Syro-Canaanite.58

• A similar ship, discussed below, appears in the tomb of Nebamun in a vignette showing the deceased ministering to a Syro-Canaanite. The artist clearly intended to indicate that the ship belonged to the foreigner.

• The ships lack hogging trusses.59 Säve-Söderbergh believes that they were concealed by the high screen or simply omitted by the artist. The hogging truss may not be a true indicator of a New Kingdom Egyptian seagoing ship, however, if, after Hatshepsut, Egypt adopted keeled hulls. A large mast is stepped amidships. The bindings low on two masts may be wooldings (Figs. 3.4–5). If so, the masts were composite.60

The craft carry the typical boom-footed Late Bronze Age rig, best illustrated on Hatshepsut’s Punt ships. One mast has a square-shaped crow’s nest, and lookouts appear on the other craft, although the crow’s nests themselves are hidden by the rigging (Figs. 3.6, 4–5). A row of triangles hanging beneath the boom on several ships may represent toggles for furling sail, or tassels (Figs. 3.3–6).61

The artists did not understand the workings of the ships’ rigging. On several vessels the lifts appear as pendant arcs—a form these lines take when the yard is raised in this type of rig (Figs. 2.15, 18). Kenamun’s artists did not connect the lifts to the mast in three cases; instead, they are tied to the yard at both ends (Figs. 3.3–5). In one case, the yard has been lowered (Fig. 3.6). In this position, the lifts would have been drawn taut supporting the yard (compare Figs. 2.16, 17). The artist, however, has connected the yard and boom with two lifts that form pendant arcs, hopelessly confusing their purpose. Care is clearly required in interpreting these ships.

The ships’ yards are straight. This may be an Egyptian hybrid element. Other representations of Syro-Canaanite rigs show yards that curve downward at their tips. The yard was raised and lowered by means of two halyards that are drawn as particularly thick wiggly lines. As in Egypt, when the sail was raised the halyards were tied astern, acting as additional backstays.

Braces appear on four ships (Figs. 3.3–5); once, they are tied to the lower mast. No sheets are visible, and stays are conspicuous by their absence—although the actual ships must have had stays.62 Shrouds are absent. Cables attached to the lower part of the mast may have served in their place.63 Rope ladders (?) run from the mastheads forward to the bows on two ships (Fig. 3.5).

Faulkner and L. Basch assume that Kenamun’s ships furled their sails by hoisting their boom to the yard.64 This is unlikely for the following reasons:

• In one case, the yard is shown hanging from its lifts while the halyards are slack (Fig. 3.6). This must indicate that the yard was lowered.

• The halyards of the largest and most detailed ship are held by two men standing in the ship’s stern (Figs. 3.3–4). The halyards end at the yard and presumably were attached to it. If the boom was being raised, then the halyards should have continued down the sides of the mast and been tied to the boom.

• In one ship the boom is lashed to the mast (Fig. 3.4). This would preclude moving it.

TOMB OF NEBAMUN. A second representation of a Syro-Canaanite craft is portrayed in a poorly preserved vignette in the Theban tomb of the physician Nebamun (T. 17). This shows the deceased examining a Syro-Canaanite merchant and probably portrays an actual event (Fig. 3.7).65

Nebamun’s tomb dates to the reign of Amenhotep II; thus, this scene predates that of Kenamun’s tomb by from thirty years to a century.66 It is unlikely, therefore, that both scenes were painted by the same artist(s). Despite this, the ship is remarkably like those in Kenamun’s tomb, raising the possibility that they were derived from a common source.

Two drawings of the ship, different in a number of details, have been published. In W. Müller’s reproduction, the hull and other wooden parts are colored yellow, and the brown screen is intersected by a row of vertical lines.67 The hull is crossed by two horizontal parallel lines that may represent planking seams (Fig. 3.8). These lines are intersected perpendicularly by a row of curved vertical lines. The latter are lacking on the drawing published by Säve-Söderbergh, who notes, however, orange lines on the yellow hull that may indicate the grain of the strakes (Fig. 3.9). The railing, colored red-orange, is identical to those on Kenamun’s ships.

The craft’s extremities curve smoothly upward from the keel, lacking the angularity of Kenamun’s vessels; but, like them, the posts are undecorated. The sheerline of Nebamun’s ship seems more realistic than that of Kenamun’s craft. An unusually narrow mast is stepped amidships. A square object situated at the masthead may represent either a crow’s nest, like those on Kenamun’s craft, or simply a mast cap. The raised yard curves down at the tips, a decidedly non-Egyptian trait.68

Figure 3.7. Scene from the tomb of Nebamun (T. 17) at Thebes. A Syro-Canaanite ship appears at the left of the lowest register (Amenhotep II) (from Save-Soderhergh 1957: pl. 23; © Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Figure 3.8. Müller’s drawing of the Syro-Canaanite ship in the tomb of Nebamun (after Millier 1904: Taf. 3)

Figure 3.9. Detail of the ship (Säve-Söderbergh) (after Säve-Söderbergh 1957: pl. 23; © Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

The boom is missing in a lacuna; in Säve-Söderbergh’s drawing it is reconstructed. Two lines carried aft are probably halyards. The pendant arc of a single lift is attached to either side of the yard. Three diagonal lifts (two forward, one aft) support the boom. In Müller’s reproduction, the port lift is attached to the mast at its lower junction with the yard. The starboard lifts continue up, crossing the yard, and seem to be connected to the square at the masthead.

A single quarter rudder is shown. It rests on a stanchion, an element notably lacking on the Kenamun ships. The tiller is attached above the stanchion, which is identical to the Egyptian New Kingdom form of quarter rudder (Figs. 2.23, 26).69

THE MNŠ SHIP. The peculiar determinative for the mnš ship, which appears in slightly different variations in five inscriptions of Ramses III on the temples of Abydos, Karnak, and Luxor, illustrates a ship of the type depicted in the tombs of Kenamun and Nebamun (Fig. 3.10). Säve-Söderbergh assumes that the determinatives depict an indigenous Egyptian ship type, later adopted by the Syro-Canaanites.70 In fact, as the type appears earlier as distinctly Syro-Canaanite, it is clear that by the times of Ramses II, this Syro-Canaanite ship variety was being built in Egyptian shipyards.71 That these ships were merchantmen is clear from an inscription of Ramses II: “I have given to thee (Seti I) a ship (mnš), bearing cargoes upon the sea, conveying to thee the great [┌marvels┐] of God’s-Land, and the merchants doing merchandising, bearing their wares and their impost therefrom in gold, silver and copper.”72

DOR. In 1982 an ashlar stone incised with the fragmentary remains of what appears to be a (Syro-Canaanite?) ship’s hull and rigging was found at Dor (Fig. 3.11).73 The stone was in secondary use in a Hellenistic city wall. The rigging has numerous lifts and is clearly of the boom-footed type, giving the graffito a terminus ante quern ca. 1200 B.C.74 It may represent a Syro-Canaanite ship.75

TELL ABU HAWAM. A schematic graffito incised on the outer surface of a bowl fragment from Hamilton’s Stratum V at Tell Abu Hawam, dated to the fourteenth through thirteenth centuries B.C., is one of only two Late Bronze Age ship representations presently known from Israel (Figs. 3.12–13).76 Two quarter rudders trailing at the left indicate that the ship is facing right. The bow is missing.

The hull is angled, showing a strong sheer. The four parallel lines that seem to compose it may represent an open bulwark. Alternately, they may be interpreted, from top to bottom, as the boom, the top of an open bulwark, the junction between bulwark and sheer, and the bottom of the hull. In the latter case, however, it is difficult to explain why the mast is terminated at the uppermost line. This horizontal line does not continue forward of the mast.

The graffito may never have been completed. Interpretation of the left extremity of the ship is difficult because of a large piece of grit in the sherd. This part is drawn very lightly, in contrast to the deeply incised lines of the rest of the hull, mast, and most of the yard. The mast is stepped amidships, ending at the first horizontal. The yard curves downward at the tips and seems to be connected in some form (brace?) to the upper two horizontals by their lightly drawn continuations at left. Although it is unwise to read too much into such a small and schematic portrait, it does agree with other representations of Syro-Canaanite ships. downward. Slanting lines lead from the mast to stem- and sternposts. These may be either stays or lifts. They probably represent the latter, because lifts were the most prominent element in the Late Bronze Age boom-bottomed rig and were the most frequently represented part of the rigging.

Figure 3.11. Ship graffito carved on plaster from Tel Dor (photo and drawing by the author. Courtesy of E. Stern)

UGARIT. Two schematic ship representations are reported on a scaraboid seal found at Ugarit. In profile, the hulls appear as narrow rectangles bisected by a single horizontal line. The bottom line represents either the keel or the waterline. The central line probably indicates the sheer; the uppermost line may depict the top of an open bulwark, the boom, or perhaps both. The ships lack quarter rudders but have five oars.

One miniature contains all the main elements appearing on the more detailed representations of Syro-Canaanite craft. C. F. A. Schaeffer compares the two vertical lines of the mast on this ship to bipod masts common on Old Kingdom Egyptian craft (Figs. 2.2–3).77 However, since bipod masts went out of use in Egypt at the end of the Sixth Dynasty, the double line is better understood as a massive pole mast.78 The yard’s ends curve

The rigging of the second craft is enigmatic. The only vertical (mast?) is off-center, and the upper horizontal (yard?) is twisted in a pretzel-like configuration.

Cyprus

HALA SULTAN TEKE. A limestone ashlar block uncovered in a Late Cypriot IIIA1 context at Hala Sultan Teke bears a rough graffito of a Syro-Canaanite ship (Fig. 3.14).79 At left, the hull curves smoothly upward, while the other end finishes vertically. A horizontal line above the right side of the hull may indicate the top of a screen or a boom, although there is no indication of a mast. In hull shape, this graffito is identical to the mnš-ship determinatives and thus represents a ship of that Syro-Canaanite class.

Figure 3.13. (A) Line drawing of sherds with ship graffito found in Hamilton’s excavation at Tel Abu Hawam (fourteenth–thirteenth centuries B.C.); (B) detail of the Tell Abu Hawam ship graffito (courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

The graffito’s particular interest is in its right extremity: it ends in a post with both a vertical internal edge and a decidedly hollow external edge. Although most pronounced in this illustration, this hollow outer post edge is identifiable on the ships of Kenamun, Nebamun, Ramses III’s mnš-ship determinatives, and a terra-cotta ship model from Enkomi (Figs. 3.3, 8–10).

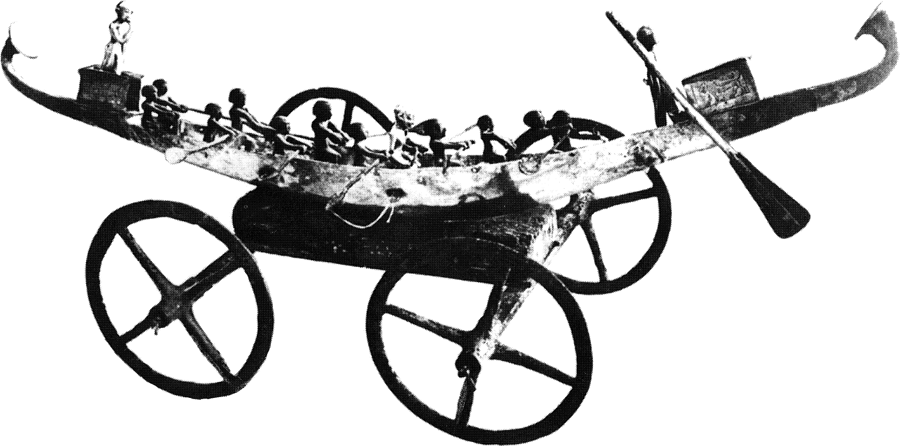

ENKOMI. The Enkomi model is of Late Cypriot I–II date; it comes from an unknown context at Enkomi (Fig. 3.15). R. S. Merrillees unconvincingly compares it to the three ship models from Kazaphani and Maroni Zarukas (Figs. 4.5–6, 8).80 The model may be patterned after a Late Bronze Age Syro-Canaanite ship, for it bears a striking resemblance to the ship portrayed in the tomb of Nebamun, with a rockered keel and significant hollows on the outer edges of the identical stem- and sternposts. Doubt exists, however, concerning the date of the Enkomi model. Perhaps it is patterned after an Iron Age Phoenician craft. It bears more than a passing likeness to two eighth- or seventh-century B.C. models from Achziv and to Assyrian reliefs of Phoenician ships.81

An Iron Age date seems unlikely on archaeological grounds, however. By the eighth through seventh centuries, the great Late Bronze Age city of Enkomi had shrunken into a humble settlement. A single tomb at Kaminia is the only known architectural remains of that date, despite extensive excavations there.82

Figure 3.14. (A) Ashlar block from Hala Sultan Teke with a graffito of a ship (Late Cypriot IIIA1); (B) detail of the ship graffito (from Öbrink 1979:73 fig. l03)

Characteristics of Syro-Canaanite Seagoing Ships

The iconographic evidence allows the following general conclusions about Syro-Canaanite seagoing ships:

• In profile the hulls are crescentic. There is little evidence upon which to base a length-to-beam ratio, although at least two sources—Kenamun and Nebamum—portray a class of trading ships. This argues for a fairly beamy vessel. The Enkomi terra-cotta, the only known model that may represent a Syro-Canaanite seagoing ship, is too problematic for conclusions on hull ratios.

• The ships’ stem- and sternposts lack decoration. They may be more or less identical, both vertically oriented (ships of Kenamun and Nebamun, the Enkomi model, and perhaps the Ugarit seal), or the stem may be vertical while the sternpost rises as a gentle curve (mnš-determinative, Hala Sultan Teke, and Tell Abu Hawam, in which the bow is lacking). Vertical posts on these ships have a vertical inner edge and a hollow external edge.

• Rudders were placed on the quarters. Both single (Nebamun) and double (Kenamun and Tel Abu Hawam) quarter rudders are represented. The steering oars are fixed on stanchions (Nebamun) and have a tiller (Kenamun and Nebamun), an arrangement identical to that on contemporaneous Egyptian seagoing ships and on some Nile craft.

• A high screen or open bulwark ran the entire length of the craft from stem to stern. This is clearly indicated on the ships of Kenamun, Nebamun, and on the mnš-determinative; it may be inferred in the schematic representations from Tell Abu Hawam, Dor, and Ugarit.

• The yard has downward curving ends in three (Nebamun, Tell Abu Hawam, and Ugarit) of the four illustrations that portray rigging. Apart from the yard, Syro-Canaanite craft seem to have used a similar rig, with boom and multiple lifts, as was common in Egypt. The two halyards were tied aft, serving as running backstays when the sail was raised, as was normal practice in Egypt.83 Lateral cables took the place of shrouds.84

• Crow’s nests appear first on Syrian ships (Kenamun and perhaps Nebamun). Thus, they seem to be a Syro-Canaanite invention.85 Subsequently, the idea was borrowed by Egypt and the Sea Peoples (Figs. 2.37–44; 8.3–8, 10–12, 14). Rope ladders, if this is indeed what the Kenamun artists intended, appear in one scene only—and then disappear from sight until Classical times.86

• Oars appear on the ships depicted on seals from Tell el Dabca (two) and Ugarit (five).

Discussion

The “Keftiu” Ship

In Thutmose III’s annals describing the stockpiling of the Canaanite harbors during his ninth campaign (year thirty-four; ca. 1445 B.C.) we read: “Behold, all the harbors of his majesty were supplied with every good thing of that ┌which┐ [his] majesty received [in] Zahy (Ḏᵓ-hy) consisting of Keftyew ships, Byblos ships and Sektw (Sk-tw) ships of cedar laden with poles, and masts together with great trees for the ┌_ _ _┐ of his majesty.”87

“Keftiu” ships appear in only one other Egyptian text, also dating to the reign of Thutmose III.88 Several of these craft are being built or repaired at the royal dockyard of Prw nfr.89 S. R. K. Glanville considers them to be a class foreign to Egypt, apparently of Aegean origin.90 Säve-Söderbergh and E. Vermuele assume them to be a class of Egyptian-built seagoing ships.91 The origins of this class may be inferred from the following considerations:

• The ships were received as tribute from Canaan, suggesting that they were indigenous to that region.

• There was a distinct Syro-Canaanite presence at Prw nfr. Syro-Canaanite shipwrights worked there, and the gods Baal and Astarte were worshipped there.92 One official was named śbj-bᶜl, and a “chief workman” was named Irṯ—a name that Glanville identified as “the Arwadian.” Other Syro-Canaanites at Prw nfr are assigned more menial tasks.93

There are two reasons for naming a ship class after a geographic area. A ship type may have been built by, copied from, or commonly used by the inhabitants of a specific region—as, for example, in the case of the Roman liburnian.94 Alternately, it may have been used on a particular commercial run to a specific destination, like the “East Indiamen” and “Boston packets” of the recent past.95 In these cases, the name always refers to a ship’s destination.

There is no other evidence for an Aegean ship class being copied in Egypt, and it would be truly remarkable for Syro-Canaanite shipwrights to construct Aegean-style craft in Egypt.

One author assumes that “Egypt’s famed Keftiu-ships appear to have ranged northward to Cyprus, Cilicia, Crete, Ionia, the Aegean islands, and perhaps even the mainland of Greece.”96 There is nothing to indicate, however, that Egyptian ships ever sailed farther than the north Syrian coast. On the other hand, Syro-Canaanite ships were making the run to the Aegean. This, along with the connection to Canaan and Syro-Canaanite shipwrights and religion in the texts, strongly suggests that the Keftiu ships were a Syro-Canaanite class commonly used on the Aegean run.97

Figure 3.16. Terra-cotta ship model found in the excavations at Byblos (from Dunand 1937: pl. 140, no. 3306)

Figure 3.17. The interior of the hull of the ship model from Byblos (after Basch 1987: 67 fig. 122: B)

Ships Misinterpreted as Syro-Canaanite

The Syro-Canaanite identity of several other ship representations is questionable. These include ship models found by M. Dunand at Byblos and an Egyptian relief. Because the Byblian models come from the Syro-Canaanite coast, they have been thought in the past to represent local craft.

BYBLOS. A terra-cotta model found at Byblos is perfectly symmetrical fore and aft and has a rounded, rather shortened shape (Fig. 3.16).98 It is painted red and stands on a plinth reminiscent of those found at the base of some Egyptian Middle Kingdom wooden models.99 A keel runs inside the full length of the hull, protruding horizontally at stem and stern (Fig. 3.17).100 There are castles at both extremities. The ends of four through-beams protrude through the hull-planking on either side.101 No frames are indicated.

Dunand believes the model represents a small Syro-Canaanite fishing boat. He compares it to Kenamun’s ships and the large mahons that traded along the Syrian coast in the recent past. The two central through-beams he identifies as benches; the protruding beam ends at the model’s extremities he considers oculi. He does not offer an identification for the external protrusions of the two central beams. J. G. Février also considers that the model represents a Syro-Canaanite ship and notes that, although internal frames are lacking, the through-beams must have strengthened the hull structurally.102

Basch identifies the model as a Late Bronze Age Syro-Canaanite merchantman but then compares it to the Sea Peoples’ ships at Medinet Habu (Fig. 8.1). He notes that both the model and the relief depict ships that are symmetrical, with castles at stem and stern. Basch concludes that the model’s end projections are the continuation of the keel but then compares these prominent elements with undersized spurs that appear at the junction of sternpost and keel on ships N.4 and N.5 (Figs. 8.11: E, 12: A).103 Basch considers the projections of ship N.4 to be at the ship’s bow, while on N.5 it is at the stern. However, the position of the steering oars on the ships indicates that in both cases the projection is at the stern.104

I believe that this model copies a known Egyptian ship type, even though it was not made to scale or reduced uniformly in size. If the terra-cotta is “stretched,” it bears a remarkable resemblance to the New Kingdom Egyptian traveling ship variety already discussed (Figs. 2.19–23; 3.18).105 These vessels have long, drawn-out stem- and sternposts, castles at either end, and through-beams. This model, together with the Egyptian wooden models and depictions, suggests that these ships did indeed have keels but that amidships they protruded prominently inward—not outward—beneath the hull.106

The second terra-cotta model from Byblos has a flat bottom, a high sheer, and is crudely made (Fig. 3.19).107 The stern has less overhang than the stem. A rectangular cabin, divided into two rooms, is located in the stern; its roof is flat and decorated in a checkered pattern. The interior of the craft is painted red, and the area of its caprail is ornamented with short incisions.

Dunand theorizes that the model was inspired by Nile boats. He is led to this conclusion by the model’s width, its flat bottom, and the checker decoration on the cabin’s roof. Février, followed by Sasson, believes that the model represents a small but strong seagoing Syrian craft.108 He tries to calculate the dimensions of the craft on which the model is based, assuming that the cabin was high enough to stand up in. From this, Février postulates a length of from eight to ten meters and a beam of between four and six meters for the model’s prototype.

Figure 3.18. Bow of a wooden traveling ship model with forecastle and stempost intact (from Landström 1970:108 fig. 338)

Calculations of this type are extremely tenuous when one is not dealing with scale models—a category that clearly does not include this terra-cotta. Février further argues against Dunand’s nilotic identification. He believes that the cabin was placed inside the hull rather than on a deck, as was customary in Egypt, to provide additional stability in a seagoing craft.

Février’s uncritical evaluation and conclusions are unconvincing. The model bears no resemblance to known Bronze Age Syro-Canaanite seagoing boats. The cabin is placed inside the hull, probably more because of the technical difficulties of constructing a deck than because of considerations of stability. Terra-cotta ship models with decks are exceptionally rare in the Bronze Age (Fig. 6.37).

Figure 3.20. (A–B) Egyptian wooden models of Nile ships (First Intermediate period) (after Landström 1970: 74 figs. 219, 221)

The model is so similar to Egyptian traveling boats dating from the First Intermediate and Middle Kingdom periods, however, that Dunand’s identification is almost certainly correct (Fig. 3.20). Even the division of the cabin into two compartments finds its exact Egyptian parallels.109

The conclusion that this terracotta is a copy of an Egyptian river craft raises an interesting question: how was a local Byblian potter familiar with non-seagoing Egyptian craft? One possible explanation is that wooden Egyptian ship models found their way to Byblos through trade, or perhaps as part of the personal baggage of visiting Egyptian officials. Since such models were constructed of perishable materials, they would have left no trace in the archaeological record.

Several metal ship models were found at Byblos in the Champ des offrandes.110 The best preserved of these is a craft of long and narrow dimensions dating to the eighteenth century B.C. (Fig. 3.21).111 The model’s hull is a thin plate of bronze flattened by hammering. The stem is pointed, the stern curved. The posts are not accentuated. Two through-beams are located at the bow and at the stern. Dunand assumes that the through-beam in the bow was used for stepping the mast. The stern beam acts as a base for the steering oar’s stanchion. Metal ribbons attach the steering oar to the ship at the stanchion and the stern. The model is either patterned after an Egyptian model or is in itself Egyptian; its closest parallels are representations of Egyptian traveling ships of Middle Kingdom date (Fig. 11.3).112 Metal ship models are also known from Egypt (Figs. 3.22–23).

In conclusion, Egypt’s influence on Byblos during the second millennium is manifest in the ship models from that site, as it is in so many other areas. Unfortunately, these models add nothing to our knowledge of Syrian ships.

THE SHIPS OF INIWIA. A relief from the tomb of Iniwia dating from the Nineteenth to Twentieth Dynasties depicts three ships that have been compared with Hatshepsut’s Punt ships (Figs. 3.24, 30: A).113 These ships raise a number of problems, however. We know that Egyptian artists could combine elements of different objects in their depictions to create nonexistent “hybrid” items.114 Because of this peculiarity of Egyptian art, objects, human figures, and even entire scenes were composed by uniting elements from two or more sources. For example, Davies, commenting on the decorations seen on several gold vessels taken as booty from Syro-Canaanite kingdoms during the Nineteenth Dynasty, notes that these decorations are unified in a single item (Fig. 3.25: A).

Obvious hybrid copies of these items are found in depictions on booty taken during the Libyan wars of Seti I and Ramses II. The decorations on these vases, albeit clever creations, are variations on the same themes used for the Syro-Canaanite vessels (Fig. 3.25: B). To these decorations the artist has included additional Egyptian and Aegean motives. Davies discounts the validity of these “Libyan” vessels.115

Thutmose III’s “botanical garden” in the temple of Amun at Karnak is another interesting example of “hybridism” (Fig. 3.26). Some 275 examples of animals, birds, and plants from the Syro-Canaanite littoral are depicted on the walls of this chamber. Although the birds are portrayed with particular accuracy, such is not the case concerning the flora. Some of the plants are depicted accurately, but other “specimens” are either based on imprecise memory or are clever inventions.116

Another fascinating example of hybridism is found in the scene of foreign tribute and trade depicted in the tomb of Menkheperresonb, dating to the latter part of Thutmose III’s reign.117 With the exception of the first three figures, who are typical Syro-Canaanites, all the men portrayed in Register I are Aegeans (Minoans) with cleanshaven faces, long coiffures, skin of a dark red color, and Aegean skirts like those in the tomb of Rechmire.118 Beneath this register, however, the tableau is a different matter. Three Syro-Canaanites introduce the register; they are identical in all but minor details and labels to the first three figures in Register I. Interspersed between the remainder of the row of Syro-Canaanites and their womenfolk are figures that bear both Syro-Canaanite and Aegean attributes.

Figure 3.21. A bronze (?) ship model from Byblos (ca. eighteenth century B.C.) (from Dunand 1950: pl. 69, no. 10089)

Figure 3.22. Silver ship model from the tomb of Queen Ahhotep, mother of Ahmose (after Landström 1970: 98 fig. 312)

Figure 3.23. Gold ship model from the tomb of Queen Ahhotep (from Landström 1970: 98 fig. 311)

Figure 3.27: A illustrates a typical red-skinned Aegean of Register I. Figure 3.27: B depicts the head and bust of a typical Syro-Canaanite with light yellow skin, bearded face, and straight-cropped hair held in place by a fillet. Figure 3.27: C is a clever combination of the two cultural stock-types. In skin color and kilt he is Aegean; yet his head is that of a Syrian. Clearly, this foreigner is a clever orchestration of details from two entirely distinct ethnic sources.

Figure 3.24. Ship relief from the tomb of lniwia (Nineteenth–Twentieth Dynasties) (from Landström 1970:138 fig. 403)

Figure 3.25. Hybrid vessels depicted in scenes of captured spoils from Syria (A) and Libya (B) (after Davies 1930: 36 fig. 6, 37 fig. 7)

Hybridism is also at work in the case of the ships of Iniwia.119 These are based partly on elements taken from the Punt ships of Hatshepsut portrayed at Deir el Bahri (Figs. 2.15–18). The scene’s general layout, however, and certain other elements of the ships’ construction and cargo are derived from a stock scene depicting Syro-Canaanite ships like that portrayed in the tombs of Kenamun and Nebamun (Figs. 3.2, 8–9).

The bows of Iniwia’s three ships are best compared to Hatshepsut’s seagoing Punt ships. The leftmost of Iniwia’s ships carries a hogging truss that crosses the forward overhang and rises aft at an angle (Figs. 3.24, 30: A-arrow). It seems that this hogging truss is derived from Hatshepsut’s scene at Deir el Bahri. The interest that this unique monument held for later generations is illustrated by a sketch of the queen of Punt, derived from the relief that was made by a Ramesside artist (Figs. 2.12–13; 3.28).

If the hogging truss were all there was to go on, it would be reasonable to conclude that these are typical New Kingdom seagoing ships. Other elements, however, suggest a Syro-Canaanite identification for the ships. First, the mast carries a basketlike crow’s nest attached to its forward side. As noted above, before the twelfth century B.C. this is a feature that appears only on Syro-Canaanite ships. Second, Iniwia’s ships have screens above the sheer; and third, each ship has a pithos nestled in its bow. All of these elements appear also on the Syro-Canaanite ships in the Kenamun scene (Figs. 3.2–6).

To further illustrate the borrowing that has taken place here, note the portions of the Kenamun scene blocked out in Figure 3.29 and enlarged in Figure 3.30: B. For further clarity, the latter illustration has been reversed right-to-left, and the vertical lines of the fence above the sheer, as well as the zigzag lines of the water, have been excluded.

When the Iniwia relief is compared with this portion of the Kenamun scene, their likeness is striking. There are three ships in the Iniwia scene and only two in the Kenamun scene. But in the latter scene there are three boarding ladders. The Kenamun ships have large jars in the bows and a crow’s nest attached to the forward side of the mast. These are the only two scenes in Egyptian art in which a crow’s nest of this type appears.

Figure 3.26. A scene from Thutmose III’s “botanical garden” in the Temple of Karnak (photo by the author)

Figure 3.27. Hybridism in human figures. Figure C is a hybrid creation in which the Egyptian artist combined the body, skirt, and red skin color of a typical Minoan (A) with the bearded head and straight-cropped long hair, held in place with a fillet, of a stock yellow-skinned Syro-Canaanite (B). (Tomb of Mencheperresonb [T. 86]; Thutmose III) (figures after Davies and Davies 1933: pls. 5 and 7)

Figure 3.28. Ramesside sketch of the Queen of Punt derived from her depiction in the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri. Limestone flake from Deir el Medina (after Peck 1978:115 fig. 46)

Figure 3.29. Detail of the scene from the tomb of Kenamun showing the portions depicted in Figs. 3.30:B and 3.31:A-B (from Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

Figure 3.30. (A) Line drawing of the relief from the tomb of Iniwia; (B) Line drawing of the scene of Syrian ships from the tomb of Kenamun. For the sake of clarity, this scene has been reversed here (A after Landström 1970:138 fig. 403; B after Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8)

Figure 3.31. (A) Scribe from the Kenamun scene (reversed); (B) man with staff from the Kenamun scene; (C) the scribe from the Iniwia scene; (D) the official with staff from the Iniwia scene carries the scribe’s pen box under his arm (A and B after Davies and Faulkner 1947: pl. 8; C and D after Landström 1970:138 fig. 403)

The ships carry the same number of lifts (six) on each side of the mast, instead of the eight carried by Hatshepsut’s Punt ships. Furthermore, in both scenes the porters are carrying what appear to be Canaanite jars on their shoulders.

Note the scribe and “headless” man with a staff in Kenamun’s scene blocked out in Figure 3.29 and enlarged in Figure 3.31: A–B. The scribe is again reversed here left-to-right for clarity. Compare these figures to the two Egyptian officials facing the ships in the Iniwia scene (Fig. 3.31: C–D). They are identical with the exception of their clothing. Note also that in the Kenamun scene, the Egyptian scribe holds his pen box under his arm (Fig. 3.31: A). Iniwia’s scribe has raised his arms, however, making it impossible for the artist to place the pen box under his arm (Fig. 3.31: B). The pen box was transferred, therefore, to the official with the stick (Fig. 3.31: D).

In summary, the ships in the Iniwia relief never really existed. They are cleverly contrived hybrid constructions that lived only in the fertile mind of the artist who created them. Attempts to reconstruct an actual ship on the basis of this relief are not valid.120