, normally understood to be the Egyptian term for the Mediterranean, actually refers to the Nile Delta.7 The reality of pharaonic seafaring probably is to be found somewhere between these two extremes.

, normally understood to be the Egyptian term for the Mediterranean, actually refers to the Nile Delta.7 The reality of pharaonic seafaring probably is to be found somewhere between these two extremes.Egyptian Ships

Egyptian civilization developed along the Nile River. It was, therefore, only natural that movement was primarily by water; even the concept of “travel” was expressed as “sail upstream” and “sail downstream.”1

There are innumerable depictions of river boats in Egyptian iconography; here the discussion is limited to seagoing craft, or material that bears directly on them and their uses. Egypt was the only country to trade in both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea during the Bronze Age; much of the extant information on Egyptian seagoing ships derives from the trade with Punt and will be discussed below.

Primitive river craft probably existed on the Nile by Paleolithic times: the earliest Egyptian craft were presumably papyrus rafts.2 Indeed, the Cheops ship is so technically advanced that development over thousands of years must be assumed.3 Reed rafts, wedge-shaped bundles of reeds constructed of two conical bundles laid side by side and lashed together at intervals, were still used on the Nile in this century.4 The modern Nubian rafts consist of pairs of bundles of reeds lashed together. J. H. Breasted notes how similar this is to the term for raft in the Pyramid texts where it appears in the dual usage (“two sḫn”). Interestingly, apart from the verbs meaning “to hew” and “to make,” the most characteristic Egyptian word for shipbuilding is “to bind.”5

Opinions vary as to whether Egypt can be considered a seagoing culture. T. Säve-Söderbergh argues for a strong Egyptian seagoing presence on the Mediterranean.6 In doing so, he totally negates Syro-Canaanite seafaring. At the other extreme, A. Nibbi claims a total lack of Egyptian maritime involvement. She argues that the Egyptian term “the Great Green Sea”  , normally understood to be the Egyptian term for the Mediterranean, actually refers to the Nile Delta.7 The reality of pharaonic seafaring probably is to be found somewhere between these two extremes.

, normally understood to be the Egyptian term for the Mediterranean, actually refers to the Nile Delta.7 The reality of pharaonic seafaring probably is to be found somewhere between these two extremes.

The Textual Evidence

The earliest reference to a nautical Egyptian presence on the Mediterranean Sea is a report, recorded on the Palermo Stone, of the importation of wood by Sneferu (Fourth Dynasty). The text, however, does not indicate the nationality of these transport ships.

Bringing forty ships filled (with) cedar logs.

Shipbuilding (of) cedarwood, one “Praise-of-the-Two-Lands” ship, 100 cubits (long) and (of) meru-wood, two ships, 100 cubits (long).8

Thus, from earliest times, timber for shipbuilding and other purposes was a primary article of trade for Egypt. Pharaonic inscriptions found at Byblos suggest that trade connections may date back at least to Nebka (Khasekhemi), last pharaoh of the Second Dynasty.9 By the Fifth to Sixth Dynasties, Byblos had become an Egyptian entrepôt for the importation of timber.

Uni, a military commander under Pepi I (Sixth Dynasty), describes the transport of his troops by sea in his cenotaph at Abydos:

When it was said that the backsliders because of something were among these foreigners in Antelope-Nose, I crossed over in transports with these troops. I made a landing at the rear of the heights of the mountain range on the north of the land of the Sand-Dwellers. While a full half of this army was (still) on the road, I arrived, I caught them all, and every backslider among them was slain.10

The term “Antelope-Nose” apparently refers to a prominent mountain range. Although the identification is not certain, Uni may be referring to the Carmel ridge, which juts out “noselike” into the Mediterranean.11 If so, Uni perhaps landed his troops north of the Carmel mountains, on the Plain of Jezreel, and found villages and fortified towns there.

During the Twelfth Dynasty considerable quantities of cedarwood were being imported into Egypt: one text mentions “twenty ships of cedar.”12 An inscription from Saqqara describes military expeditions to the Syro-Canaanite coast and possibly to Cyprus  in which ten ships transported the army returning from Lebanon.13

in which ten ships transported the army returning from Lebanon.13

The “Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor” describes the adventures of an Egyptian who survived the sinking of his ship in the Red Sea while on a voyage to the mines of Sinai.14 This is the earliest “shipwreck” ever recorded, and, although meager, it also supplies the only textual information on seagoing ships in the Middle Kingdom.15 The sailor relates that his ship had a 120-man crew and that the craft measured 120 cubits in length by 40 cubits in beam.16

Because the entire tale is phantasmagoric, these numbers must be approached with caution, particularly as we know little of the sizes of ships’ crews. One Rammeside Nile ship had a crew that varied daily from 26 to 40 men.17 A ship of Amenhotep II had 200 rowers, but this number might be a convention.18 The size of the sailor’s ship need not be exaggerated, however. Sahure refers to 100-cubit-long ships that he had built. Furthermore, the beam/length ratio of 1:3 is credible, although it does suggest an extremely beamy and slow craft.

The “Admonitions of Ipu-wer” describe a period of social unrest when foreign trade connections ceased to exist. It was created sometime during the turbulent years between the collapse of the Sixth Dynasty and the rise of the Eleventh.19 In describing a lack of embalming materials that were normally imported from Byblos, Ipu-wer complains of the lack of trade with Byblos.20 This assumes that maritime trade had existed previously. Ipuwer also emphasizes the directionality of the trade: Egyptians had gone north to Byblos.

During the Eighteenth Dynasty, Thutmose III sailed with his army to the Syro-Canaanite shore on his sixth campaign (thirtieth year, ca. 1449 B.C.). This is evident from the ship determinative following the word “expedition” that is used here for the first time.21 The previous year Thutmose’s forces had captured Syro-Canaanite ships. Breasted assumes that these were used to return the army to Egypt.22 Säve-Söderbergh notes, however, that only two ships were captured and that the reference in Thutmose’s annals probably resulted from their valuable cargoes.23 Two ships would not have been sufficient to carry the army home but could perhaps have transported Thutmose and his staff.

Thutmose soon realized the advantages of transporting his army by sea and improved the logistics involved by organizing and stockpiling the ports on the Syro-Canaanite coast during his seventh campaign (thirty-first year, ca. 1448 B.C.): “Now every port town which his majesty reached was supplied with good bread and with various (kinds of) bread, with olive oil, incense, wine, honey, fr[uit],. . . . They were more abundant than anything.”24 References to stockpiling the harbors continue in all the following years for which annals are preserved.25

Timber, particularly Lebanese cedar, continued to be a valuable import commodity during the New Kingdom. Senufer, an official under Thutmose III, recorded bringing back a cargo of cedarwood from the Lebanon. Concerning his return trip he wrote, “[I sailed on the] Great [Green] Sea with a favorable breeze, land[ing in Egypt].”26

In one Amarna text, Abimilki of Tyre mentions a contingency plan for abandoning Tyre with all the “king’s ships.”27 If these refer to Egyptian ships stationed in Tyre, it suggests that Thutmose’s organization of harbor cities, with its emphasis on rapid sea transport, continued to operate into the mid-fourteenth century. Another Amarna text is also best understood in this light.28 Rib-Addi, the embattled king of Byblos, repeatedly requested an Egyptian ship to take him to Egypt if troops did not arrive.29 Säve-Söderbergh believes this to be indicative of Egyptian supremacy of the sea lanes during the Amarna period.

Egyptians, some of whom must have been trading agents, are mentioned operating in several Syro-Canaanite cities.30 The Mycenaean personal name a3-ku-pi-ti-jo (the Egyptian) suggests some form of contact with Egypt.31 This name is enigmatic, however. Is this an Egyptian living in the Aegean, an Aegean who had some form of contact with Egypt, or does it have some other significance?

In Papyrus Harris I, Ramses III records the building of three types of seagoing ships to transport goods from Canaan to the treasuries of three Egyptian gods:32

I made for thee (Amun of Karnak) qerer-ships, menesh-ships, and bari-ships, with bowmen equipped with their weapons on the Great Green Sea. I gave to them troop commanders and ship’s captains, outfitted with many crews, without limit to them, in order to transport the goods of the land of Djahi and of the countries of the ends of the earth to thy great treasuries in Thebes-the-Victorious. . . .

I made for thee (Re of Heleopolis) qerer-ships and menesh-ships, outfitted with men, in order to transport the goods of God’s Land to thy storehouse. . . .

I made for thee (Ptah of Memphis) qerer-ships and menesh-ships, outfitted with crews of menesh-ships in abundant numbers, in order to transport the goods of God’s Land and the dues of the land of Djahi to thy great treasuries of thy city Memphis.

Ramses III dispatched fleets to Punt and to Atika, a land rich in copper:33

I sent forth my messengers to the country of the Atika (ᶜᵓ -ty-ka), to the great copper mines which are in this place. Their galleys carried them; others on the land-journey were upon their asses. It has not been heard before, since kings reign. Their mines were found abounding in copper; it was loaded by ten-thousands into their galleys. They were sent forward to Egypt, and arrived safely. It was carried and made into a heap under the balcony, in many bars of copper, like hundred-thousands, being of the color of gold of three times. I allowed all the people to see them, like wonders.

Atika, which could be reached by both water and land, was tentatively located by Breasted in Sinai.34 An alternate identification, proposed by B. Rothenberg, locates Atika in the copper-producing Valley of Timna near Eilat.35 Copper was mined at Timna mines by the Egyptians during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, including during the reign of Ramses III.36 If this identification is correct, it would mean that Egyptian seagoing ships were rounding the Sinai peninsula and penetrating the Gulf of Eilat in the early twelfth century B.C.

In the “Renaissance Period,” Wenamun sailed to Byblos to bring back timber for the Amun Userhet, the sacred barque of Amun that took part in a yearly procession from Karnak to Luxor and back again.37 This text indicates that because of Egypt’s decline in power, sea trade with Egypt at that time was controlled by the inhabitants of the Syro-Canaanite coast. During his interrogation of Wenamun, Tjekkerbaal, the king of Byblos, speaks of transactions that had no doubt taken place during the Late Bronze Age. He mentions six shiploads of Egyptian goods that previous pharaohs had sent as payment for timber.38 Presumably, the goods arrived in Egyptian hulls.

The Archaeological Evidence

An axehead belonging to an Egyptian royal boat crew was found in 1911 in the Adonis River (Nahr Ibrahim) on the Lebanese coast, just south of Byblos (Fig. 2.1).39 It bears the following inscription: “The Boat-crew ‘Pacified-is-the-Two-Falcons-of-Gold’; Foundation [gang] of the Port [Watch].” The royal name “Two Falcons of Gold” was a title of both Cheops (Fourth Dynasty) and Sahure (Fifth Dynasty). In form it dates to the Third to Sixth Dynasties.

A. Rowe notes that the axehead must have belonged to one of the ship crews that sailed to Lebanon to acquire cedarwood for either Cheops or Sahure. Both rulers had trade contacts with the Syro-Canaanite coast. In addition to the text discussed above, Sahure also depicted his ships returning from a trip to that region (below). The excavated ship of Cheops is built mostly of Lebanese cedarwood, and his name is recorded on vase fragments at Byblos.40

Egyptian-type anchors were found in Middle Bronze Age contexts in temples at Byblos and Ugarit (Figs. 12.28: 21; 33: 11).41 Presumably, these had been dedicated by Egyptian ship crews who had voyaged with their ships to these cities.

The Iconographic Evidence

The seeming “snapshot” quality of Egyptian wall paintings and reliefs can be misleading. Each picture must be approached with caution and interpreted in light of what is known from other sources.42 The Egyptian artist did not always include all the same details in two representations of the same ship. For example, in the tomb of Senufer at Thebes, a funerary barge is being towed downstream from Thebes to Abydos.43 In the scene below it, the barge is being towed back upstream to Thebes. W. F. Edgerton notes that this painting is a unit: the same barge and towing boat are represented in both scenes. Despite this, in one scene the thole bights, scarfs of planking, and through-beams are visible; in the other scene, they are missing.

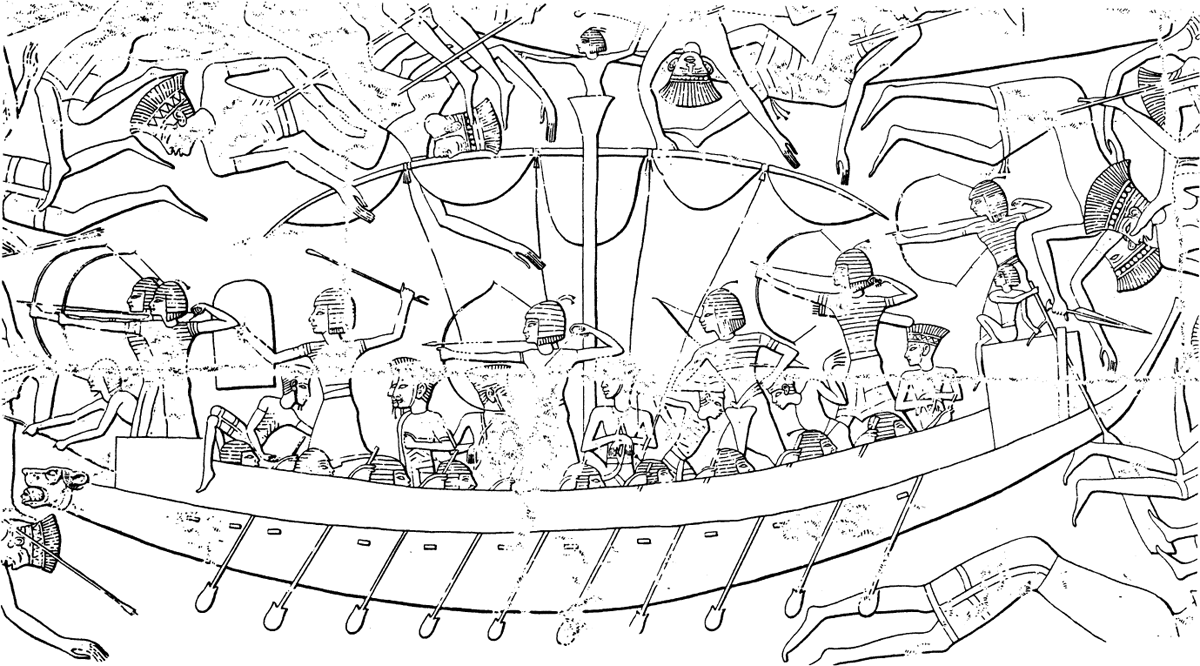

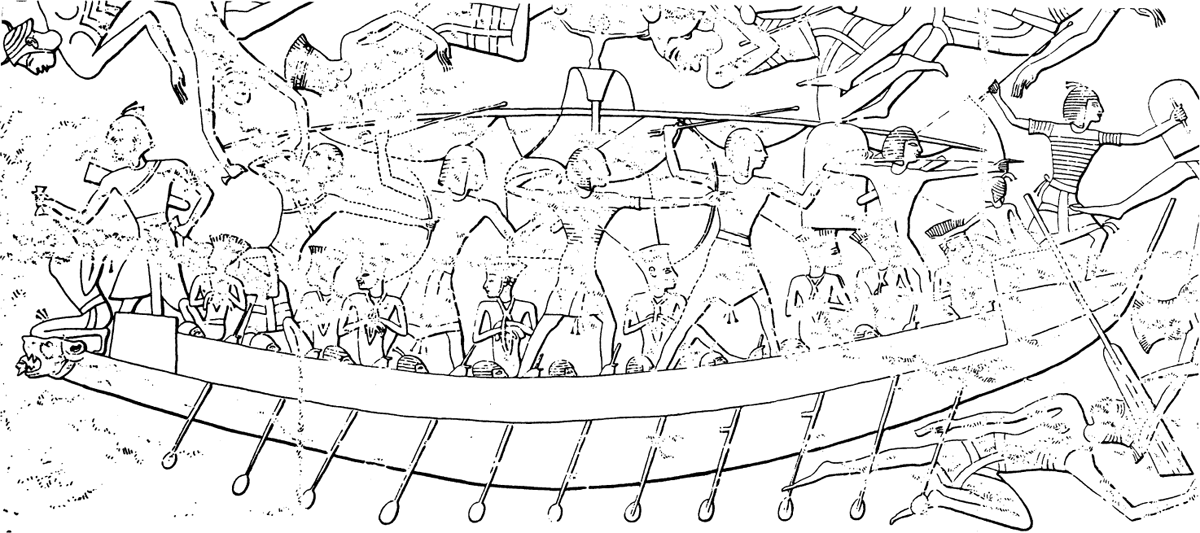

Similarly, in Ramses III’s naval battle scene depicted at Medinet Habu, the ships of both warring sides are stereotyped into one type of craft: the accompanying text, however, indicates that at least three varieties of craft took part on the Egyptian side alone.44 Thus, we are presented with several images of a single ship that is portrayed in varying degrees of detail.

Figure 2.1. The axe head belonging to a royal boat crew of Cheops or Sahure, found in the Nahr Ibrahim (from Rowe 1936: pl. 36:1, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority)

One question that must be asked of the following Egyptian scenes of seagoing ships is whether they are of a narrative nature. That is, do they describe specific events carried out by particular characters in a given location at a determined time, or are they simply pictures meant to transmit an idea?45

Finally, it is worth reemphasizing that the following discussion does not deal with actual ships but instead with artists’ representations of them. These depictions can deviate from the original craft because of artistic conventions and individual artistic ability.

Old Kingdom

SAHURE. The first definite depictions of seagoing ships in Egypt are on a relief from Sahure’s burial temple at Abusir (Figs. 2.2–3). They appear on the north and south sides of the east wall of the west passage.46 Both sides of the wall are divided into four registers, the lower two of which depict seagoing craft. The remains of four ships on the north side indicate the moment of departure for the Syro-Canaanite coast; eight ships on the south side represent the return voyage.

M. Bietak suggests that the Asiatics depicted on the seagoing ships of Sahure and Unas represent the ships’ crews.47 This interpretation is unlikely for several reasons:

• The ships used in these scenes are undeniably Egyptian. If Egypt was using Asiatic crews, why not use Asiatic ships?

• In the Sahure scene, the ships departing Egypt are manned solely by Egyptian crews: Asiatics appear only on the ships returning from overseas. This must indicate that the Asiatics were not the ships’ crews.

• Finally, even if the Egyptians were using Asiatic crews, why would a pharaoh wish to communicate this information in his temple complex instead of depicting the impressive importation of valuable tribute? Contrast this, on the one hand, to the importance placed on the ships’ cargoes in Hatshepsut’s scene of her expedition to Punt (Figs. 2.17–18, 33) and, on the other hand, to Wenamun’s embarrassment when he is reminded by Tjekkerbaal that the ship on which he arrived, and its crew, were Syro-Canaanite:

Where is the ship for (transporting) pine wood which Smendes gave you? Where is / its Syrian crew? Wasn’t it in order to let him murder you and have them throw you into the sea that he entrusted you to that barbarian ship captain? With whom (then) would the god be sought, and you as well, with whom would you also be sought? So he said to me.

And I said to him: Certainly it is an Egyptian ship and an Egyptian crew that are sailing under Smendes. He has no Syrian crews. And he said to me: Surely there are twenty cargo ships here in my harbor which are in commerce with Smendes. As for that Sidon, / the other (port) which you passed, surely there are another fifty freighters there which are in commerce with Warkatara, for it is to his (commercial) house that they haul.

I kept silent. . . .48

G. A. Gaballa considers Sahure’s scene an artistic rendition of a specific event of which two moments are recorded: the departure and the return. The home-bound vessels carry a number of Syro-Canaanites accompanied by their wives and children, all of whom are paying homage to the pharaoh. He assumes that the purpose of the voyage was peaceful and that the scene may represent an Egyptian trading expedition to the Syro-Canaanite coast.

Figure 2.2. Egyptian seagoing ships on a relief from Sahure’s burial temple at Abusir (Fifth Dynasty) (from Borchardt 1981: Blatt 12. Reprinted, by permission, from Zeller Verlag edition.)

Figure 2.3. One of Sahure’s seagoing ships (from Borchardt 1981: Blatt 13. Reprinted, by permission, from Zeller Verlag edition.)

The peaceful nature of the expedition is questionable. In several cases, the Syro-Canaanites are being held by the scruffs of their necks as they raise their arms in adoration, a behavior most inappropriate if the Asiatics were arriving under peaceful circumstances. Most likely the Asiatics were, in themselves, human tribute.49

The hulls of Sahure’s ships appear to have an exaggerated sheer. The vessels’ stems and sterns are finished with vertical posts bearing the Eye of Horus and ankh signs. This is the earliest iconographic depiction of an oculus.50 A band of rope lashing runs the length of the hull beneath the sheerstrake. C. V. Sølver suggests that this either hid the ends of the deck planking or connected the sheerstrake to the hull.51

Each ship carries a hogging truss connected to cables laid around the stem and stern and supported on stanchions to provide additional longitudinal support. A study of the basic load conditions acting on a seagoing craft explains the need for a hogging truss on these ships.52

Figure 2.4. The hull of one of Sahure’s ships showing a diagonal scarf (after Edgerton 1922–23: 131 fig. 10)

A seagoing ship must have the structural strength to head perpendicularly into waves having a length between crests greater than or equal to that of the ship itself.53 When the crests are at the ship’s extremities, its midships section is in a trough. In this case, the upper lateral area is under compression and the lower area under tension.54 More importantly, when the ship is supported amidships by a single wave, the stresses are reversed. The upper structure is now under tension while the hull’s lower portion is under compression. This latter condition is encountered more often because it can be produced by shorter waves. That is, assuming a wave amidships, the previous crest has just left the stern area while the next wave has not yet reached the bow.

Thus, even in a moderate sea, ships lacking sufficient longitudinal support in the form of a developed keel and framing system and with exaggerated overhang at stem and stern will tend to “hog,” or break in two, unless they are given additional longitudinal support. The hogging truss allows for the required tension to be set.55

As we shall see, seagoing ships on the Red Sea run to Punt must have been lashed.56 The Mediterranean ships of Sahure, as well as those of Unas, may also have been lashed, perhaps in a manner similar to the Cheops ship.57 Edgerton notes three joints on the ships in Sahure’s relief where planks were diagonally scarfed instead of abutting squarely (Fig. 2.4). He concludes, “The planks in each strake were held together end to end by flexible bands, possibly of rawhide or metal. But we have to infer that the planks in one strake were secured to those above and below by dowel-tongues or dovetails, since no bands are visible across the longitudinal seams.”58

Figure 2.5. Seagoing ships portrayed on a relief from the causeway of Unas at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty) (from Hassan 1954:139 fig. 2)

The Cheops ship explains why lashing would have been invisible from the outside: the ropes were transversely lashed through V-shaped mortises cut into the internal surfaces of the strakes and cannot be seen on the hull’s exterior (Fig. 10.4). The diagonal planking scarfs on Sahure’s ships are also similar to those on the Cheops ship (Fig. 10.5).

On Sahure’s ships, three steering oars, lacking tillers, are placed between the stanchions in the stern on the port side. Presumably each ship carried a total of six of these quarter rudders, the number required being indicative of their inefficiency. Seven oars are attached to the hull with lanyards. Sølver suggests that these craft lacked proper decks: in their place the craft may have had removable boards between the deck beams.59 Each ship is shown with its mast lowered onto a crutch positioned in the stern. The masts are bipod, probably a continuation of the types of masts used originally on papyrus rafts.60

UNAS. Two additional Old Kingdom seagoing ships are depicted on a relief from the causeway of Unas’s burial temple (Fig. 2.5).61 These ships are similar in hull form and rigging to those of Sahure; Unas’s artists seem to portray the same class of Egyptian seagoing ship depicted by Sahure. The execution of Unas’s relief, however, lacks the high quality and detail of that of Sahure. In both cases, the ships are shown with Syro-Canaanites on board (Figs. 2.3, 6).

Unas’s ships have tripod masts.62 These are held in place by cables, wound under tension, that are attached laterally to loops in the ships’ hulls (Fig. 2.7). These cables, which also appear on contemporaneous Nile ships, apparently took the place of shrouds (Fig. 2.10).63 The hogging truss, although shown in much less detail in Unas’s ships, is similar to those on Sahure’s ships. In the latter, the truss is connected to the hull by girdles, while Unas’s ships have the truss itself passing directly around the hull, a feature probably attributable to artistic license (Fig. 2.8). Nile cargo ships portrayed on Unas’s causeway bear multiple vertical posts at stem and stern and a tripod mast (Fig. 2.9).

Figure 2.6. Detail of the two Syro-Canaanites at the stern of the ship on the right. Causeway of Unas at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty) (photo by the author)

Figure 2.7. Detail of the lateral trusses supporting the tripod mast of a seagoing ship depicted on a relief from the causeway of Unas at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty) (photo by the author)

Figure 2.8. The stern of a seagoing ship depicted on the right side of a relief from the causeway of Unas at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty) (photo by the author)

Figure 2.9. River cargo craft portrayed on a relief from the causeway of Unas (from Hassan 1954:137 fig. 1)

Figure 2.10. Trusses are used to give lateral support to river ships of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties (A after Landström 1970: 42 fig. 112; B–C after Goedicke 1971:107, 111)

B. Landström notes that during the Fifth Dynasty, the booms of Nile River ships rested abaft the mast on the caprails (Fig. 2.10: A–C).64 On seagoing ships, the boom must have been placed higher up and hung forward of the mast because of the longitudinal hogging truss. It is not clear how the boom was connected to the mast.65

Calculations concerning the dimensions of the actual ships themselves are untrustworthy. Unas’s ships carry the three conventional quarter rudders per side but only four rowers’ oars. The number of oars shown may be misleading. Landström considers the Sahure reliefs as scale projections of the ships and calculates their length at 17.5 meters based on the number of rowers. Based on a wooden model of Sixth Dynasty date that may represent a vessel of this type, he postulates their beam at about 4 meters.66 Prototypes for the ships depicted by Sahure and Unas may have been much larger than generally thought, however, since the human figures are probably shown in a much larger scale than the ships themselves, and it is likely that there were more oars than are portrayed.

Middle Kingdom

There are no known depictions of seagoing ships from the Middle Kingdom, nor from the intermediate periods that preceded and followed it.

New Kingdom

DEIR EL BAHRI. A most detailed depiction of Egyptian seagoing ships is the expedition to Punt portrayed on Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri (Fig. 2.11).67 Hatshepsut emphasized foreign connections and internal affairs over military accomplishments—to which she could hold little claim.68 Her representation of the Punt expedition suggests that it was a unique voyage. Actually, it was remarkable that Hatshepsut chose to emphasize this accomplishment, because maritime contacts with Punt had been common as early as the Old Kingdom.69

Figure 2.14. Fishes and other marine animals depicted beneath Hatshepsut’s seagoing ships at Deir el Bahri (after Naville 1898: pls. 69–70, 72–75)

Punt is first mentioned in the Fifth Dynasty when Sahure lists myrrh, electrum, and wood obtained there.70 Under Pepi II (Sixth Dynasty), Enenkhet was killed while building a “Byblos ship” for a voyage to Punt.71 In the contemporaneous inscription of Harkhuf, Pepi II refers to a dwarf brought from Punt.72 A short historical inscription of Khnumhotep in the tomb of Khui at Aswan (Sixth Dynasty) refers to visits to both Punt and Byblos.73 Henu (Eleventh Dynasty) recorded the construction of a Byblos ship for a trip to Punt in his Wadi Hammamat inscription.74

Hatshepsut’s craft are termed Byblos ships (Kbn).75 The name need not indicate that the ship was bound for Byblos but instead that it was of the class normally used on the run from Egypt to Byblos.76 Apparently, this term originally defined a class of Egyptian seagoing ship that was used on the Byblos run; however, by the end of the Old Kingdom, the term had come to include large seagoing ships, whatever their destination. The ships, probably constructed of cedarwood, may have been built on the Nile and then disassembled for transportation through Wadi Hammamat to Quseir on the Red Sea coast, where they were reassembled.77 At the completion of the voyage, the craft would have been stripped down and carried back through the desert valley to Koptos. For this to be possible, the craft must have been of lashed construction.

The scene depicts memorable details of the voyage and the land of Punt, its inhabitants, and the sea creatures encountered during the voyage (Fig. 2.12). Note particularly the grossly fat wife of the leader of Punt (Fig. 2.13).78 The fishes and other marine animals depicted here are, for the most part, indigenous to the Red Sea (Fig. 2.14).79 Some, however, are fresh-water Nile fish that have been transferred to this scene.80 Presumably, the marine creatures were recorded after they had been hooked—or netted—by the crew but before they ended up in the pot.81 The artist did not see the animals in their natural habitat. This is evident from the manner in which they are depicted. All the fish and other creatures are depicted swimming to the right, including two lobsters and a squid. The artist was either unaware that both of these creatures swim backwards or preferred to keep them facing the same direction because of artistic considerations.

Figure 2.15. Ships sailing for Punt. Lower right quarter of scene of Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt at Deir el Bahri (from Naville 1898: pl. 73)

Figure 2.16. Ships arriving at Punt and unloading trade items. Lower left quarter of scene of Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt at Deir el Bahri (from Naville 1898: pl. 72)

Figure 2.17. Ships loading cargo at Punt. Upper left quarter of scene of Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt at Deir el Bahri (from Naville 1898: pl. 74)

Figure 2.18. Ships returning from Punt. Upper right quarter of scene of Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt at Deir el Bahri (from Naville 1898: pl. 75)

Figure 2.19. Sheer view of a wooden ship model from the tomb of Amenhotep II (Reisner no. 4944) (after Landström 1970:109 fig. 339)

Figure 2.20. Reisner’s drawings of the same ship model from the tomb of Amenhotep II (Reisner no. 4944) (after Reisner 1913: 96 figs. 348–49)

These details indicate beyond reasonable doubt that the scenes must be based on the work of an artist (or artists) that accompanied the expedition.82 This is of importance vis-à-vis the ships, for it indicates that the source materials used by the Deir el Bahri artists were most likely based on firsthand observation.

The scene was carved in relief and then painted, but only faint traces of the paint still remain. Some details may have been portrayed only in paint and disappeared with the centuries.83 The persons involved, whether Egyptian or Puntite, are recognizable and play definite roles in the various events. The development of episodes is clear and comprehensible.84 The voyage is portrayed in two registers on the northwest wall. The time sequence is clockwise from bottom right to top right and shows four phases of the sea voyage (Fig. 2.11).

Bottom right. The flotilla begins its journey as the ships sail for Punt (Fig. 2.15). The last ship leaving Egypt on the outward journey has, over its stern, the captain’s order: “Steer to port.”85 Above the ships is the following inscription: “Sailing in the sea, beginning the goodly way towards God’s-Land.”86

Bottom left. The ships arrive at Punt; using a gangway, trade items are transferred to a launch for further transport to shore (Figs. 2.16, 12.51).87 These are explained as “(an offering) for the life, prosperity, and health of her majesty (fem.), to Hathor, mistress of Punt  that she may bring wind.”88

that she may bring wind.”88

Top left. The produce of Punt is loaded on board the ships. The cargo is depicted on deck (Fig. 2.17). Above the ships is this inscription:89

The loading of the ships very heavily with marvels of the country of Punt; all goodly fragrant woods of God’s-land, heaps of myrrh-resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony, and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, (ᶜmw), with cinnamon wood, khesyt wood, with ihmut-incense, sonter-incense, eye-cosmetic, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of the southern panther, with natives and their children. Never was brought the like of this for any king who had been since the beginning.

The Puntites ask the Egyptians, “Did ye come down upon the ways of heaven, or did ye sail upon the waters, upon the sea of God’s-Land.”90

Top right. The ships return with their cargo to Egypt (Fig. 2.18). Above the returning ships is the inscription “Sailing, arriving in peace, journeying to Thebes with joy of heart, by the army of the Lord of the Two Lands, with the chiefs of this country behind them. They have brought that, the like of which was not brought for other kings, being marvels of Punt, because of the greatness of the fame of this revered god, Amun-Re, Lord of Thebes.”91

There is a reason for the direction of the scene. The orientation of Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el Bahri is basically northwest by southeast.92 Thus, left equates with south while right equates with north. Sailing left signifies sailing south to Punt, which is portrayed on the south wall of the temple.

Gaballa notes the similarity to the Sahure relief at Abusir, where the departure scene is depicted on the north side because the Syro-Canaanite coast was north of Egypt.93 Thus, both Sahure and Hatshepsut oriented their scenes with respect to the countries involved. The Old Kingdom rendition is more static, illustrating only two points in time, the departure and the arrival; the New Kingdom scene expands this into four scenes. The workmanship of the sculptured relief is so fine that the ships almost seem to be based on scale drawings. This is probably illusionary.94

Figure 2.21. Stern of ship model from the tomb of Amenhotep II (Reisner no. 4944) (after Landström 1970:108 fig. 337)

How many ships took part in the expedition? Five ships are shown, but this may be artistic license. Expeditions to Punt, including the crews required to reconstruct the ships on the Red Sea coast, could be quite large. The list of participants of Antefoker’s expedition (Twelfth Dynasty) totaled 3,756 men, of which only 500 were sailors.95

Figure 2.22. Deck plan of a ship from the tomb of Amenhotep II (Reisner no. 4946) (after Reisner 1913: 98 fig. 354)

The ships are portrayed in profile and appear to be long and slender. However, impressions can be deceptive in a two-dimensional aspective portrayal. The hulls of Hatshepsut’s Punt ships bear a strong similarity to a particular hull form that appears in the New Kingdom and is known from models found in the tombs of Amenhotep II and Tutankhamen (Figs. 2.19–23).96 These models have long, nearly horizontal stem- and sternposts. The Punt ships differ in several details from the models: they lack the central cabin, their extremities are finished in a different manner, and they are outfitted with hogging trusses. The models suggest a beam/length ratio of about 1:5 for this ship type.97

Figure 2.23. Wooden model of a traveling ship from the tomb of Tutankhamen (after Landström 1970:107 fig. 331)

Only one hull at Deir el Bahri has the rectangular butt ends of through-beams evident (Fig. 2.15). Either the beam ends were painted on the other hulls and have subsequently disappeared, or the artists never bothered adding them. R. O. Faulkner believes that the through-beams took the place of the truss girdle that appears on Old Kingdom seagoing ships (Figs. 2.2–3).98 The Old Kingdom vertical sternpost was replaced with a conventionalized recurving papyrus umbel, a decoration also used on New Kingdom Nile traveling ships.99

Figure 2.25. Bow section and quarter rudder on two of Hatshepsut’s Punt ships (detail from Naville 1898: pl. 73)

Each ship is portrayed with fifteen rowers to a side. Assuming a standard minimum interscalmium of about one meter and allowing another four meters at both stem and stern, the total length of these craft would have been about twenty-three meters—if the number of rowers is not a convention. The ships show prominent and no doubt exaggerated overhang, both fore and aft. The waterline is indicated, although it is unconvincingly low. The stempost is vertical with a straight forward face and a curving rear surface. It lacks the Eye of Horus decoration, but with that exception is basically identical to stems on Old Kingdom seagoing ships. The Eye of Horus may have been originally painted on the stems in the relief and subsequently disappeared.

The decking of these ships remains unclear. L. Casson assumes that they were decked only along their center line and that there was an open space for the rowers to sit at their oars.100 The bows are taken up with a forecastle in which two men are stationed; no figures are portrayed in the sterncastles. These castles are probably similar to those on New Kingdom traveling ships, of which several illustrations exist.101

The heavy twisted-cable hogging truss is carried over four crutches. It is not clear how it is attached inside the hull. Perhaps it was connected to through-beams. The multiple cables circling the bow and stern were intended to prevent the planking there from buckling under the strain of the hogging truss (Figs. 2.24–26).

Although the hogging truss is a hallmark of Egyptian seagoing ships without keels, trusses were also used on other craft whenever tension was needed. They appear on Hatshepsut’s obelisk barge, as support for a ship in the midst of being launched and, on occasion, on Nile ships (Figs. 2.27; 10.9).102 No anchors are portrayed on these ships.103 This led G. A. Ballard to the unlikely conclusion that they had none.

Figure 2.27. Three cargo ships from the tomb of Huy have hogging trusses that are carried over the hull on forked stanchions and are fastened to the stem and stern (Eighteenth Dynasty) (after Landström 1970:134 figs. 390–92)

Figure 2.28. Sølver’s reconstruction of Hatshepsut’s Punt ship with a bipod mast (from Sølver 1936: 458 fig. 10)

The ships have a single pole mast stepped in the ship’s center. Sølver reconstructs this as an A-shaped bipod mast like those on Sahure’s ships (Figs. 2.3, 2.28).104 His argument was based on the assumption that the hogging truss always disappears behind the mast. This is simple artistic convention, however. It is similar to the bowstring and drawn arrow in Egyptian art passing behind the body of an archer, as, for example, when Ramses III draws his bow against the Sea Peoples (Fig. 8.1).105 Had a bipod mast been intended, the Egyptian artist would have indicated it in the normal manner. Furthermore, the bipod mast went out of use in Egypt at the end of the Old Kingdom. There is no reason, or logical explanation, for it to suddenly reappear in the fifteenth century.

Figure 2.32. Detail of a ship’s bow (from Naville 1898: pl. 72)

The masthead has an elaborate construction to carry the rigging (Fig. 2.29). Faulkner believes the masthead was misunderstood by the artists and that it consisted of a metal cap or sheath with eyes that carried the standing and running rigging.106 The masthead, seen from behind, had eyes on either side to take the lifts. Above these was a mast cap formed by three horizontal bars connected to the mast and joined at their extremities by vertical side pieces. The halyards ran through the lower part of this construction. The upper part held a single pair of running lifts, used when the sail was in the raised position. This form of masthead seems to have developed from simpler Middle Kingdom forms that lacked the upper mast cap.107

Figure 2.33. Detail of a midship section of one of Hatshepsut’s seagoing ships (from Naville 1898: pl. 74)

The yard is horizontal when in the raised position and curves upward at its extremities when lowered. Both yard and boom were constructed of two timbers lashed together at the center. The boom was lashed to the mast to prevent the spillage of wind; the sail was spread by raising the yard to the masthead. The boom was sturdy: crew are occasionally shown standing and sitting on it (Figs. 2.15, 18, 30).108

The sail is low and wide, forming a horizontal rectangle: depicted parallel to the hull, it approximates the ship’s length. A boom may have been required for a sail of such large span.109 The foot of the sail could not have been spread by regular sheets because these would tend to pull inward so much that the wind would have spilled out at the sail’s foot. This is not the primary reason for the boom’s appearance, however, for it appears earlier on tall, narrow sails (Fig. 2.10: A).110 When lowered, the sail appears to have been detached from the boom and furled to the yard (Fig. 2.30).

With a following wind the sail was placed perpendicular to the hull, but the exaggerated spread must have been difficult to manage even in moderate seas.111 When sailing without cargo, these ships must have been heavily ballasted to prevent them from capsizing.112

Despite the seeming exactness of the relief, not all the rigging is shown. A pair of forestays, a single backstay, and two halyards give the rig longitudinal support. The forward stay is attached to the hull, perhaps by means of a beam, in an area where cables girdle the hull (Fig. 2.31). In several cases the loop of a knot is visible (Figs. 2.31–32). The second forestay seems to have been attached to the same beam as the hogging truss. The lone backstay is fastened to the hull just forward of the quarter rudders (Fig. 2.26). The halyards are portrayed as thick, braided ropes. A detail of the knot attaching the halyards to the yard appears on one ship (Fig. 2.33). Although the knot to the right of the mast is indistinguishable, the one on the left is perhaps a clove-hitch. If so, this is curious, for this knot is poorly suited for such a purpose.

When the yard was in its raised position, running lifts held it horizontal. At Deir el Bahri the running lifts end at the masthead (Fig. 2.29). A painting of a New Kingdom Nile ship shows how these worked, however.113 Here, four thick, wavy lines descend from the masthead to the stern. Landström suggests that these represent pairs of halyards and running lifts.

The multiple lifts connecting the boom to the yard are the most distinguishing characteristic of this rig. Some of the more detailed representations of the knots attaching the lifts to the boom show the lines turned several times around the yard or boom (Fig. 2.34).114 The lifts supporting the yard were stretched taut when the yard was lowered (Figs. 2.16–17). When the sail was set they hung loosely in pendant arcs that Hatshepsut’s artists depicted in elongated form for aesthetic simplicity (Figs. 2.15, 18).

The purpose for these multiple lifts has been variously interpreted. Ballard and Sølver believe that the lifts served mainly for supporting men aloft in the rigging.115 R. Le Baron Bowen argues that the lifts were used primarily for raising the sail.116 At that time, in his opinion, they were set up hard, bending the boom up sharply along its entire length. This made the sail slack, easing the weight of the boom off the sail while it was being raised. Once the sail was in the raised position, the boom lifts were loosened and the weight of the boom pulled the sail taut. The lifts’ original purpose may have been to give support to the boom and sail if they dipped in the water when the ship rolled.117

Braces and sheets appear on only one ship (Figs. 2.15, 34). The braces are tied to the yard midway between yardarm and mast on either side; the sheets are tied even closer to the mast on either side of the boom.118 These lines would have been difficult to handle when tied so near to the center of the yard and boom; their positioning may result from artistic considerations.

The ships are steered by a pair of quarter rudders carried on stanchions, operated by vertical tillers (Fig. 2.26). The loom passes through a vertical crutch that is secured by a plain lashing and a rope tackle attached to a stud on the hull’s exterior.119 The manner by which the ships are being rowed has received several interpretations.120

Quarter rudders show an interesting development on Egyptian Nile River vessels.121 The steering oars were originally levered against the side of the stern.122 The broad overhanging sterns of Nile craft would have aided in this manner of steering. From the Sixth Dynasty, the steering oar was bound in place and was turned on its axis.

Tillers appear slightly earlier, in the Fifth Dynasty. By lengthening the tiller, the helmsman had better leverage over the oar. Because tillers are lacking on Sahure’s or Unas’s ships, they were probably invented after their reigns. Stanchions also appear first in the Fifth Dynasty. By placing the oar’s loom on a stanchion, the helmsman no longer had to hold the loom. The introduction of stanchions and tillers made superfluous the stationing of multiple steering oars on both sides of a vessel. Presumably, this innovation was also adopted on Egyptian seagoing ships at that time.

The ships returning from Punt carry the cargo on deck (Figs. 2.17–18, 26, 33). This may be a result of the artists’ desire to illustrate the valuable commodities brought back while, in reality, the cargo would have been stowed lower in the hull.123 Indeed, the trade items brought to Punt and off-loaded there by the expedition are not shown on the outgoing journey.

These craft, however, may have normally carried their cargo primarily on deck. J. Hornell, describing the hulls of modern Sudanese cargo nuggars, notes that they agree in all details of construction with the Dahshur boats.124 The breadth of both is exceptionally great while depth is reduced to a minimum to facilitate navigation in shallow waters.125 In section, the hull resembles almost the perfect arc of a circle. This is the counterpart of a shallow, rounded arch in architecture.126 It affords strength to maintain original curvature when under considerable pressure. It also enables the hull to carry heavy loads without suffering distortion or damage that would otherwise occur due to water pressure exerted on the exterior when the craft was heavily laden.

In Nile nuggars, the greater part of the cargo is often stored on and above deck level.127 Hornell notes that C. D. Jarrett-Bell is theoretically correct in suggesting that the curves of the Dahshur boats indicate that they would have normally carried their load on deck; such also may have been the case with Hatshepsut’s Punt ships.128

MEDINET HABU. Four Egyptian ships portrayed on Ramses III’s mortuary temple locked in a naval battle with the Sea Peoples’ ships are generally considered seagoing vessels (Figs. 2.35–42).129 This is perhaps due to the misconception that the battle took place at sea; in reality it probably took place in the Nile Delta.130 The ships are portrayed in a summary fashion and lack detail. The scene was painted in colors that have long since disappeared. Because the Egyptian artists did not differentiate between incised and painted detail in their reliefs, and as the scene seems to have gone through several drafts, much information may have been lost (Fig. 2.36: C–D).131 The ships are apparently four depictions of the same ship with varying detail. In profile they are long and low with a crescentic hull. Above the hull is a light bulwark that protects the rowers.

The impossible manner in which the human figure in ship E.1 is placed, leaning over the line that represents the junction of the sheer and the light bulwark, need not be a result of artist’s error (Fig. 2.36: A: A). As H. Schäfer notes, in Egyptian art one sometimes receives the impression that part of a person’s body is disappearing behind a structure.132 At first, this would appear to be drawn according to modern perspective, directly from a mental image. However, such was not always the case. In one example offered by Schäfer, a man is looking out of the door of a ship’s cabin with half his body protruding—but the body begins at the outside edge of the door post.133 The position of the figure in ship E.1 is apparently also a result of this phenomenon in Egyptian art.

Faulkner and Casson consider Ramses’s vessels to be influenced by foreign construction and totally different from earlier Egyptian ships.134 However, Ramses’s ships seem to be basically a variant of a type of Eighteenth Dynasty traveling ship exemplified by models from the tombs of Amenhotep II and Tutankhamen (Figs. 2.19–23; 3.18). But none of Ramses’s ships in the relief show the differentiation between the posts and the hull that is depicted on Hatshepsut’s Punt ships or the models.135 Either Ramses illustrates a different type of ship or the artists have consistently left out—or depicted in paint, now obliterated—details that would clarify this question. Perhaps the hulls of Ramses’s ships were spoon-shaped, like the hull of several other models from Tutankhamen’s tomb.136

Figure 2.36. (A) Ship E.1, Medinet Habu (Ramses III); B ship E.1 with all visible lines depicted; (C) the portion of the ship that appears to belong to a first draft; (D) the parts of ship E.1 that may reasonably be assigned to its revised draft. (A detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39; introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved. Published June, 1930. B–D details from Nelson 1929: 27 fig. 19, 29 fig. 20; © 1929 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.)

Figure 2.37. Ship E.2, Medinet Habu (Ramses III) (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39; introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved, published June, 1930)

Figure 2.38. Ship E.2 in the naval battle at Medinet Habu (Ramses III) (photo by B. Brandle)

Figure 2.39. Ship E.3, Medinet Habu (Ramses III) (detail from Nelson et al. 2930: pl. 39; introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved, published June, 1930)

Figure 2.40. Ship E.3 in the naval battle at Medinet Habu (Ramses III) (photo by B. Brandle)

The stempost of Ramses’s ships ends in a lion’s head with a Syro-Canaanite head in its mouth; the sternpost continues the curve of the hull. Faulkner thought the ships had a raised gangway.137 Each of the ships has castles at bow and stern. The sterncastle is at least partially roofed, for the helmsmen are repeatedly shown seated on top of it and the archers stand in it. The butt ends of through-beams appear on three ships, E.2–E.4 (Figs. 2.37–42).

The actual length of these ships is difficult to determine. The figures are clearly depicted at a scale larger than the ships, and the number of rowers varies from eight (ships E.1 and E.2) to eleven men (ship E.4) on each side.

A single helmsman steers each ship with a lone quarter rudder. The rudder is attached to a stanchion that appears on at least one ship (E.3), but the vertical rectangle that constitutes the stern part of the sterncastle on ship E.2 may also be a rudder stanchion (Figs. 2.37–39). The tiller is short and straight, like those used in the Fifth through Eleventh Dynasties.138 The helmsmen grip the quarter rudder in an unusual manner (Fig. 8.9).139 The short tiller is always held in the right hand, and on three ships (E.1–E.3), the helmsmen either hold the loom in their left hands or cradle it in their arms. The need for this is unclear.

The rig used by the Egyptian ships is identical to that of the Sea Peoples’ ships appearing in the same scene. In place of the boom-footed rig, the ships carry brailed sails.140 One can only speculate whether the unusual Egyptian custom of attaching the brail fairleads to the after side of the sail began at this time.141 The mast ends in a crow’s nest, from which slingers hurl stones at the invaders. This is the earliest depiction of a crow’s nest on an Egyptian ship.

Figure 2.41. Ship E.4, Medinet Habu (Ramses III) (detail from Nelson et al. 1930: pl. 39; introduction © 1930 by the University of Chicago, all rights reserved, published June, 1930)

Figure 2.42. Ship E.4 in the naval battle at Medinet Habu (Ramses III) (photo by B. Brandle)

Discussion

The Seagoing Vessels of Punt

An unnamed tomb at Thebes (T. 143; Amenhotep II) contains a unique scene of a watercraft from Punt bringing trade items (Figs. 2.43–44).142 The accompanying text notes, “Making rich provision (?) . . . gold of this district (Punt?) together with gold of the district of Koptos and fine gold (?) in enormous amounts.”143 The items brought by the Puntites include gold, incense, ebony, trees, ostrich feathers and eggs, skins, antelopes (?), and oxen. This scene also shows people of Punt bringing their cargo to an Egyptian port, perhaps Quseir on the Red Sea, where the Egyptians bartered with them. The background of the scene is pink—as is the land of Punt in the Deir el Bahri display. Norman de Garis Davies feels that this represents the inhospitable Red Sea coast.

The hulls portrayed are narrow and rectangular with rounded ends, colored pink like the background. Obviously, these craft were unfamiliar to the Egyptian artists. Davies suggests that they are coracles; alternately, they may depict dugouts. The figures and items of trade are portrayed above the body of the vessel rather than in it, perhaps because of a desire to show them in their entirety.

The rig is very simple and is similar to that used on some Old Kingdom ships.144 It consists of a single yard with a triangular sail of black cloth or matting. No outrigger is shown, but if these craft were dugouts, an outrigger would have been necessary to prevent them from capsizing when a sail was used. Interestingly, the much later Periplus of the Erythraean Sea repeatedly mentions similar small-scale trade taking place in various types of rafts and other small craft in the lowermost area of the Red Sea.145

The Egyptian Ship Graffiti at Rod el ᶜAir

Turquoise, the Egyptian mf t, was considered particularly valuable in pharaonic Egypt. The Egyptians went to considerable effort to mine it in southwest Sinai. During the Middle and New Kingdoms the center of turquoise mining was at Serabit el Khadem, where the Egyptians built a temple to Hathor, the goddess of turquoise.

t, was considered particularly valuable in pharaonic Egypt. The Egyptians went to considerable effort to mine it in southwest Sinai. During the Middle and New Kingdoms the center of turquoise mining was at Serabit el Khadem, where the Egyptians built a temple to Hathor, the goddess of turquoise.

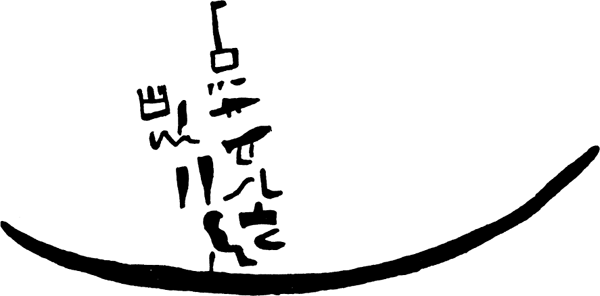

The Egyptian expeditions reached the plateau of Serabit el Khadem via Wadi Rod el ᶜAir, where a base-camp has been found.146 The smooth rock faces of the wadi contain numerous hieroglyphic inscriptions and graffiti. These include a unique group of Egyptian ship graffiti that is of particular interest to pharaonic seafaring: it is at present the only such group known that was drawn by Egyptians outside the geographic borders of Egypt and separated from it by a sea.

There are indications that, at times, the Egyptians reached Sinai by ship. The “Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor” indicates that, in the Middle Kingdom, expeditions were sent to the mines of Sinai by ship. Further evidence of this is found in the various nautical titles that appear at Serabit at that time.147 The port at Wadi Gawasis was apparently a starting point for crossing the Red Sea to Sinai during the Middle Kingdom.148 A New Kingdom port was identified by W. F. Albright at Merkah, south of Abu Zneimeh, on the west coast of Sinai.149 Therefore, the Rod el ᶜAir graffiti may represent the seagoing ships that transported the expeditions across the Red Sea. None of them has been studied in a nautical context; some have never been published. During a visit to the site in 1972, I studied thirteen ship graffiti described below, of which eight have been previously discussed by A. H. Gardiner and T. E. Peet.

Figure 2.43. Reception of a Puntite expedition on the shore of the Red Sea. From an unnamed tomb (T. 143) at Thebes (Amenhotep II) (from Säve-Söderbergh 1946: 24 fig. 6)

SHIP NO. 1. Ship facing left; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the Middle Kingdom (Figs. 2.45, 48: A).150 This crude graffito has only three elements: the hull, the steering oar, and its stanchion. The hull is crescentic; the long steering oar passes over the sternpost. No tiller is visible.151 There are several undecipherable hieroglyphic signs over the hull; above it is a Middle Kingdom inscription. This graffito probably represents a Middle Kingdom traveling ship (Fig. 11.3).152

SHIP NO. 2. Ship facing right; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the Middle Kingdom (Figs. 2.46, 48: B).153 The crescentic hull has an unusual tripartite stem. The large steering oar is placed over the sternpost and rests on a large stanchion. A rectangle in front of the stanchion may represent a cabin.154 In the center of the hull is an enigmatic object that may be either a three-legged oryx or an unsuccessful attempt to portray a lowered mast above a central deck structure. Several obscure signs are incised under the stern. Above the hull is a horn-shaped object that is probably unrelated to the ship.

SHIP NO. 3. Ship facing right; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the Middle Kingdom (Figs. 2.47, 48: C).155 The graffito is schematic. The hull is crescentic with a steering oar placed over the sternpost and supported on a stanchion. A series of five parallel lines rising in the bow may represent a baldachin like those on ships from the tomb of Amenemhet at Beni Hassan.156 The graffito apparently represents a Middle Kingdom traveling ship.

Three figures are on and above the boat: an archer stands in the center of the hull and faces the bow, a figure positioned above the steering assembly faces the prow with staff and scepter in his hands, and a figure to the right of the craft faces the stern and brings an offering of bread and a bird. The last figure bears the inscription “Serving man,  Bed, beloved of Hathor.”

Bed, beloved of Hathor.”

Figure 2.44. Detail of the Puntite watercraft (after Davies 1935: 47 fig. 2)

SHIP NO. 4. Ship facing left; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the Middle Kingdom (Fig. 2.49).157 This schematic graffito consists of only three lines. The hull is crescentic with a large steering oar supported on a stanchion placed over the sternpost. To the right are several undecipherable signs. Like numbers one through three, this graffito represents a Middle Kingdom traveling ship.

SHIP NO. 5. Two ships facing right; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the New Kingdom (Fig. 2.50).158 The leftmost ship has a crescentic hull positioned above an elongated rectangle (plinth?) that is bisected horizontally in its left half. The mast is stepped amidships and appears through the central deck cabin and bisects the horizontal rectangle beneath the ship. The steering oar is placed over the stern; a tiller is connected to the tip of the loom so that a helmsman would have steered from the roof of the cabin.159

The rightmost ship has a crescentic hull with a cabin amidships and a baldachin at the bow. The steering oar is placed on the quarter.

Below the ships are two inscriptions: “Setekhnakhte, true of voice” and “engraver Ḥuy, true of voice.” The midships cabin on both ships, the mast stepped amidships in the left ship, and the steering oar placed over the quarter in the right ship support a New Kingdom date for these ships.

SHIP NO. 6. Ship facing right; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the Middle Kingdom (Fig. 2.51).160 This graffito has a well-drawn crescentic hull. The steering oar is placed over the sternpost and is supported on a tall stanchion. A long vertical tiller is attached to the loom abaft its junction with the stanchion. This is a typical Middle Kingdom feature as is the horizontal quarterdeck for the helmsman beneath the rudder (Fig. 11.3).161

A cabin in the stern abuts the rudder stanchion. The mast has been unstepped and lies horizontally on two crutches. In the bow, a quadruped faces forward.162 To the right of the ship are quarry marks and the figures of a deer and an ostrich. The ship is located beneath a Middle Kingdom inscription, “He who wishes to return (home) in peace says: ‘Cool libation, burning offering and incense to the intendant Neferḥotep.’”163 The graffito depicts a Middle Kingdom traveling ship.

SHIP NO. 7. Ship (facing right?); this graffito is dated to the Middle or New Kingdoms by Gardiner and Peet (Figs. 2.52–53).164 The hull is a narrow crescent. A vertical line at the left side of the hull probably represents a rudder stanchion. A man standing amidships faces right. Over him is the hieratic inscription “Senwosret.” Beneath the hull is the New Kingdom proper name “Sunro”; this is palimpsest over an earlier effaced inscription.

Figure 2.48. Rod el ᶜAir (photomosaic). (A) Ship graffito no. 1; (B) ship graffito no. 2; (C) ship graffito no. 3 (photos by the author)

A giraffe is incised to the left of the craft and faces it. A lugged ax has been incised horizontally across the giraffe and the figure in the ship. Lugged axes have a long range of use beginning in the Second Intermediate period and continuing into the Graeco-Roman period.165 At Rod el ᶜAir, this ax graffito must date to the New Kingdom period of mining activity. To the right of the craft is a large cross (Fig. 2.53). The only reliable dating evidence for this ship graffito is the tall rudder stanchion that dates it to the Middle Kingdom.

Figure 2.54. Ship graffito no. 8 (Rod el ᶜAir) (from Gardiner and Peet 1952: pl. 95: 521)

SHIP NO. 8. Ship facing right; dated by Gardiner and Peet to the Middle Kingdom (Figs. 2.53 [upper right], 54).166 The hull is a long, narrow crescent. Above it is the inscription “Stone cutter Khab’s son Ameny.” A seated figure serves both as the boat’s occupant and determinative of the name Ameny. The graffito is too schematic to date other than by the accompanying inscription.

SHIP NO. 9. Ship facing right; unpublished. Date: Middle Kingdom (Fig. 2.55). The crescentic hull is steered by a rudder placed over the stern and a tall stanchion. The oar’s loom has a long vertical tiller that descends abaft the stanchion, as in graffito number six. A cabin nestles in the stern, forward of the stanchion. The mast is unstepped and lies horizontally. It passes over the cabin in the stern and rests on the stem and a crutch amidships. A small rectangle amidships probably represents the maststep.167 The ship bears a striking resemblance to two traveling ships in the tomb of Amenemhet, reign of Sesostris I (Fig. 11.3).

SHIP NO. 10. Ship facing right; unpublished. Date: Middle Kingdom (Fig. 2.56). The ship is similar to number nine but lacks a stern cabin. It has a crescentic hull and a steering oar with a long loom resting on the sternpost and a tall stanchion. The vertical tiller is attached to the oar’s loom abaft the stanchion. There is an unintelligible mark near the tiller. The mast is unstepped and placed horizontally from stem to crutch.

Three unpublished New Kingdom traveling ships are carved on a single smooth rock scarp (Figs. 2.57–60). The three are stylistically very similar and may have been carved by the same hand. They are portrayed as being down in the bow.

SHIP NO. 11. Ship facing left (Fig. 2.58). The hull, portrayed in outline, is long and crescentic, narrowing to a line at the stem. There are faint marks of a low stanchion, mast, and yard. Amidships and at the bow, small portions of the hull have been worked, in a manner similar to graffito number twelve. This graffito was apparently never finished.

Beneath the stem is a lugged ax, identical to that above graffito number seven, and a figure, facing left, that holds a crescentic sword (?) and shield. Beneath the stern are two inscriptions:

Khnumhotep, son of Ameny, born of Iby, living for ever.

his son Woserᶜonkh168

SHIP NO. 12. Ship facing left (Fig. 2.59). The hull is long and crescentic; the artist has worked all the surfaces of the ship and its accoutrements. A large steering oar with a wide blade is placed on the quarter and supported by a short stanchion; the tiller is forward of the stanchion. The ship has a small deck cabin amidships and castles at stem and stern. A vertical stanchion of unclear function is located in the bow abaft the forecastle. Above the stem is a #-like sign. This graffito represents a traveling ship, probably with an elongated, spoon-shaped hull; it finds its closest parallels in the Eighteenth Dynasty.169

SHIP NO. 13. Ship facing left (Fig. 2.60). This is the most detailed of the three ships. It has a crescentic, spoon-shaped hull; the lower part of the hull is worked. Apparently the artist intended to work the entire surface of the hull but never completed the task. The hull ends in the stern in a recurving (decorative?) element. A large steering oar is placed on the quarter and supported by a short stanchion. The oar has a very wide blade; the tiller is connected to the loom forward of the stanchion. A large deck cabin, crossed by horizontal and vertical lines, is placed amidships. Landström suggests that deckhouses on New Kingdom traveling ships were made of a timber framework covered by highly decorated tent cloth.170 This graffito seems to display just such a wooden framework.

The rectangle behind the cabin was probably intended as a flight of steps but was never finished.171 Castles are located at stem and stern. The forecastle is crossed vertically by one line, the sterncastle by two. The mast is stepped amidships and passes through cabin and hull. The sail has been struck down: the yard, boom, and sail are secured in a crisscross pattern. No rigging is represented.