Figure 12.1. Diagram illustrating the probable development of ancient anchors (from Kapitän 1984: 34 fig. 2)

Anchors

Anchors are to a ship what brakes are to a car; and just as a car needs brakes, a seagoing ship must carry some form of anchoring device. In the eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, these consisted of pierced stones. Through the ages, anchors were left on the sea bottom where, as a result of modern underwater archaeological exploration and sport diving, they are now being discovered in large numbers in some parts of the Mediterranean.

The British researcher Honor Frost first brought attention to the significance of the pierced stones that litter the Mediterranean seabed and are also found on Levantine land sites.1 She pointed out that by studying anchors on stratified land sites, anchors of diagnostic shape—found out of archaeological context on the sea floor—can be dated and their nationality defined.

The study of anchors is important to nautical archaeology for several reasons. An anchor on the seabed assumes the passing of a ship.2 Thus, if the anchor type belonging to a specific nationality can be defined, then finding a trail of that kind of anchor in the sea must signify a route used by ships of that nation.

Similarly, anchors of definable origins found in foreign precincts are a valuable indication of direct sea contact. Perhaps the most important contribution of the study of anchors is the theoretical possibility of identifying the home port of a wreck based on the typology of its stone anchors.3 Finally, since anchors are the main security for a storm-tossed ship, they have always had a cultic significance. Stone anchors found in cultic contexts can teach us about ancient religious practices.

Numerous anchor sites exist under the Mediterranean in areas that modern shipping would normally avoid.4 Apparently, these anchorages were necessary for ships that could not sail into the wind and, therefore, were forced to wait for following winds.

Frost defines three varieties of pierced stone anchors:5

• “Sand-anchors” are small, flat stones with additional holes for taking wooden pieces that function like the arms of the later wooden and metal anchors. The stone’s weight is minimal and is not an anchoring factor. These anchors are particularly suited for grasping a sandy bottom.

• “Weight-anchors” have a single hole for the hawser; they anchor a craft solely by their weight. These anchors may tend to drag on a flat and sandy bottom.

• “Composite-anchors” are heavier than sand-anchors but like them have additional piercings for one or two wooden “arms.” These anchors hold the bottom with their weight and arms.

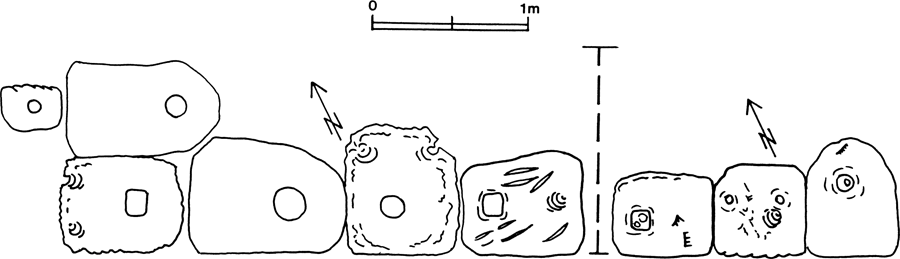

All datable Early Bronze Age anchors are weight-anchors.6 Composite- and weight-anchors are found together in Middle Bronze and Late Bronze Age contexts at Ugarit and Kition. Thus, the weight-anchor preceded the composite-anchor but continued in use alongside it. G. Käpitan suggests a progression of stone anchors originating from amorphous stones lashed to a rope and developing into pierced stones (Fig. 12.1).

In this chapter the various kinds of evidence (textual, iconographic, and archaeological) for stone anchors and their facsimiles will be discussed. The archaeological evidence is organized in geographical order. This is followed by an overview of stone anchors found on Mediterranean wrecks. Finally, several aspects of anchor study are discussed.

The Gilgamesh epic mentions “Things of Stone” that were used in some way by Urshanabi, the boatman of Utnapishtim (the Mesopotamian Noah), for crossing the “Waters of Death.”7 Urshanabi claims that Gilgamesh has broken these objects. Frost suggests that the “Things of Stone” are stone anchors.8

KTU 4.689 is an Ugaritic text that lists a ship’s equipment. Among the gear is a mšlḥ hdṯ, a term that M. Heltzer has tentatively identified as “a new anchor,” as well as a rope (ḫbl).9

Herodotus describes the use of stone anchor-like “braking devices” used by Nile ships in his day:

Figure 12.1. Diagram illustrating the probable development of ancient anchors (from Kapitän 1984: 34 fig. 2)

These boats cannot move upstream unless a brisk breeze continue; they are towed from the bank; but downstream they are thus managed: they have a raft made of tamarisk wood, fastened together with matting of reeds, and a pierced stone of about two talents weight; the raft is let go to float down ahead of the boat, made fast to it by a rope, and the stone is made fast also by a rope to the after part of the boat. So, driven by the current, the raft floats swiftly and tows the “baris” (which is the name of these boats), and the stone dragging behind on the river bottom keeps the boat’s course straight.10

The Iconographic Evidence

Stone anchors appear on representations of the seagoing ships of Sahure and Unas (Figs. 2.5; 12.2: A–B).11 The anchors have a markedly triangular shape. This has caused some confusion, and, on occasion, they have been mistakenly identified as Byblian anchors.12 They have domed tops, however, a feature typical of Egyptian anchors. Apical rope grooves, another feature common to Egyptian anchors as well as to those of other lands, are not portrayed. Perhaps this is the result of a lack of artistic detail.

The anchors of Sahure and Unas are shown standing upright. This may be attributable to artistic license; anchors stationed in the bows were (at least on occasion) placed upright, however. The better-made large stone anchors often have flat bottoms. Even in mild seas, however, such anchors must have been locked firmly into place against the ship’s sheerstrakes to prevent them from coming loose and causing damage.

Otherwise well-made anchors have an asymmetrical shape, as do the Wadi Gawasis anchors (Figs. 12.10, 11: A). They seem to “lean” to one side. This feature was apparently traceable to a desire for the anchor to stand vertically on a slanting bow or stern deck. This phenomenon is evident from studying an anchor in the bow of one of Unas’s ships. It is assumed to stand on a baseline (Fig. 12.2: B: a). When the anchor is placed on a horizontal line, it takes on the asymmetrical appearance exhibited by the Wadi Gawasis anchors (Fig. 12.3: A–B). This tendency is not solely an Egyptian idiosyncrasy: it also appears on a number of Syro-Canaanite (?) anchors found in Israeli waters (Figs. 12.3: C, 54).13

Figure 12.2. (A) Detail of an upright stone anchor, with hawser-hole indicated, in the bow of a seagoing ship depicted in the causeway of Unas at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty); (B) line drawing of A with anchor emphasized in black. The anchor is assumed to be standing on a deck parallel to line a (photo and drawing by the author)

One manner in which stone anchors were raised and lowered is graphically demonstrated on two Cypriot jugs (Figs. 8.41: A, C; 12.4). In one case, the hawser is passed through a sheave in the mast cap. The second depiction is more complicated and was interpreted by Frost as a boom.14 More recently, Frost suggests that Bronze Age ships had derrick-arms or “cargo-derricks” attached to the mast for maneuvering anchors.15 Alternatively, the artist may have intended an “exploded view” of the operation and, for reasons of composition, preferred to depict the angle where the hawser went through a sheave in the masthead, above and to the right of it.

Egyptian hieroglyphics have no word for anchor: the Book of the Dead refers only to mooring posts.16 Stone anchor-shaped objects appearing on Egyptian river craft are usually interpreted as offerings of bread.17 Indeed, if these objects were used as “braking stones” like those described by Herodotus, then they should have been positioned on the stern deck. The objects, however, are consistently displayed at the bow.

Frost and L. Basch believe that stone anchors were not used in antiquity on the Nile.18 The discovery of a group of stone anchors (including one of a distinctly Egyptian type) at Mirgissa at the Second Cataract and at Tell Basta indicates that, at least occasionally, stone anchors were indeed used on the Nile in pharaonic times. A scene from the Sixth Dynasty tomb of Zau at Deir el Gebrawi may hint at the use of an anchor (Fig. 12.5).19 In it, a crew member is coiling a rope depicted in the vertical plane to show its characteristic form. The rope goes over the bow and vertically straight into the water. N. de G. Davies identifies this as an anchor cable.20 The use of stone anchors on the Nile might explain the function of enigmatic objects, usually called “bowsprits,” that appear on Middle Kingdom ship models; these may have been fairleads for an anchor rope.21

Figure12.3. Asymmetrical stone anchors: (A) the anchor depicted at the bow of one of Unas’s seagoing ships is asymmetrical when placed on a horizontal line; (B) asymmetrical anchor from Mersa Gawasis (Twelfth Dynasty); (C) asymmetrical anchor found underwater in the ancient harbor of Dor (A after photo by the author; B after Sayed 1977:164 fig. 6; C, photo by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

C. Boreux interprets another Old Kingdom scene from the mastaba of Akhihotep-heri as depicting a man raising a stone anchor at the stern of a Nile boat.22 Basch suggests that this scene portrays a water pitcher being lowered into the river to be filled.23 It is difficult to determine which of these two interpretations is correct. In New Kingdom images, crew members are normally shown dipping their containers into the river while bending over the caprails.24 No ropes are used.

Figure 12.4. The raising of a round stone anchor is depicted on a seventh-century B.C. jug from Cyprus (from Frost 1963B: monochrome pl. 7 [opp. p. 54])

Iron anchors are recorded on the Nile by the third century A.D., and on the Nile today, ships carry iron anchors.25

The Archaeological Evidence

Egypt

The earliest datable Egyptian anchors belong to the Fifth Dynasty.26 An anchor in the mastaba of Kehotep at Abusir acted as the lintel of the false door (Fig. 12.6: A).27 The anchor’s base carries the following inscription: “The sole friend, the beloved in the presence of [pharaoh’s name erased], Kehotep.” Other stone anchors have been reported from the mastabas of Mereruka and Ptahhotep as well as in the funerary temple of the Fifth Dynasty pharaoh Userkaf (Fig. 12.6: B–C).28

Figure 12.5. Ship scene from the tomb of Zau at Deir el Gabrawi (Sixth Dynasty) (from Davies 1902: pl. 7)

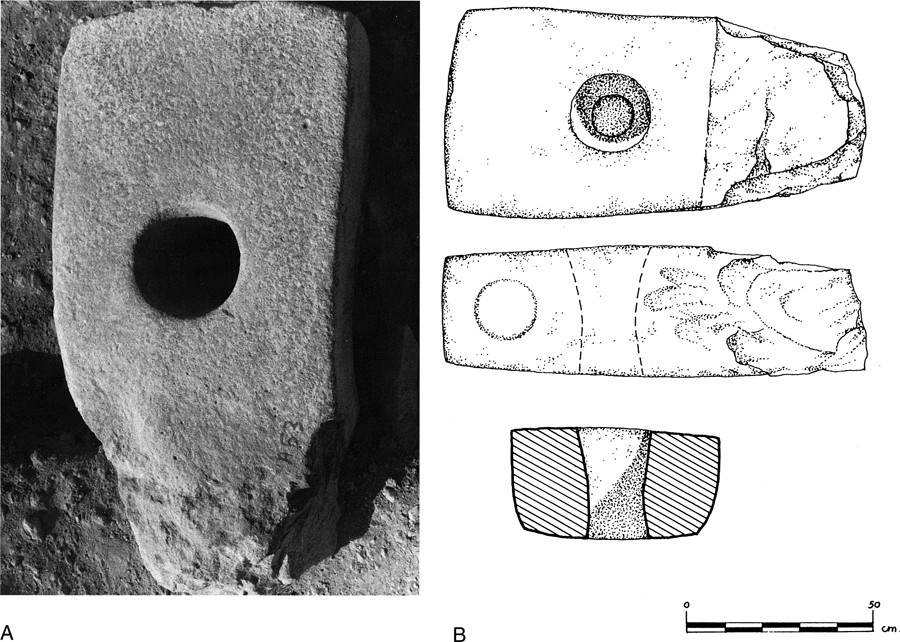

Egyptian anchors have two diagnostic characteristics: an apical rope groove near the hawser hole and an L-shaped basal hole for a second rope. Although the rope groove is found on stone anchors of other Bronze Age nationalities, the basal hole remains unique to Egypt.

The shape of the typical Egyptian stone anchor was first defined by Frost on the basis of a single anchor from the “Sacred Enclosure” at Byblos with a nfr hieroglyph incised on it (Figs. 12.7, 28: 21).29 The rope groove is particularly deep. Frost notes that the chisel marks are so well preserved that the anchor was probably never used at sea. It weighs 188.5 kilograms. Another Egyptian anchor was found in the Temple of Baal at Ugarit (Fig. 12.33: 11).30

Anchors of Middle Kingdom date found at the Red Sea site of Wadi Gawasis are important because they conclusively establish the standard Egyptian anchor shape. The shrine-stele of Ankhow was constructed of seven anchors (Figs. 12.8–11).31 Four anchors, with oval tops and tubular rope holes, form the base of the shrine; the three truncated anchors constituting the shrine’s sides still bear the L-shaped basal holes. One of these is a blind hole (Fig. 12.9: B [upper left]). The anchors weigh about 250 kilograms each.

Frost suggests that the seven anchors in Ankhow’s shrine represented seven ships used in the expedition.32 She argues that the anchors’ total weight of 1,750 kilograms would be prohibitively heavy for a single ship. The anchors from Naveh Yam and Uluburun, however, indicate that large ships normally did carry many heavy anchors.

Figure 12.6. (A) Anchor fragment that served as the lintel of the false door in the tomb of Kehotep at Abusir (Fifth Dynasty); (B) anchor implanted in the floor of the ceremonial chapel in the tomb of Mereruka at Saqqara (Sixth Dynasty); (C) probable anchor fragment from the tomb of Ptahhotep at Saqqara (Fifth Dynasty) (after Frost 1979:141 fig. 1, 143 figs. 2, 2c)

Two hundred meters west of Ankhow’s shrine, another anchor served as the pedestal for the contemporaneous stele of Antefoker (Fig. 12.12).33 This anchor lacks the typical L-shaped hole and apical groove but has eight notches on its four vertical edges. The channel cut into the top surface was a later addition to secure the standing stele.

Figure 12.8. The stele of Ankhow from Wadi Gawasis on the shore of the Red Sea (Sesostris I): (A) front view; (B) plan view (from Sayed 1977:158 fig. 3, 159 fig. 4 [A. M. A. H. Sayad, “Discovery of the Site of the Twelfth Dynasty Port at Wadi Gawasis on the Red Sea Shore (Preliminary Report on the Excavations of the Faculty of Arts, University of Alexandria, in the Eastern Desert of Egypt–March 1976),” Rd’É 29: 140–78])

Figure 12.9. The stele of Ankhow from Wadi Gawasis on the shore of the Red Sea (Sesostris I) (NTS): (A) rear view; (B) diagram of the four anchors forming the stele’s pedestal (A after Sayed 1977:157 fig. 2; B from Sayed 1980:155 fig. 1)

Two unfinished anchors and a third, smaller, anchor were found on the northern slope of the entrance to Wadi Gawasis.34 The hawser-hole of one anchor was blind, suggesting that at least some of the anchors were prepared at the site. A twelfth anchor, broken and slightly smaller than the others, was found at the port proper of Mersa Gawasis.35

Seven stone anchors were discovered at the Egyptian fortress of Mirgissa on the Second Cataract of the Nile.36 The site dates to the Middle Kingdom through the end of the Second Intermediate period. At least four of the anchors (which are made of limestone and sandstone) have apical rope grooves, but only one has the typical Egyptian shape with a basal L-shaped hole and an apical rope groove. Three additional stone anchors were recovered from New Kingdom levels at Tell Basta.37 None of the three has basal holes: one has a long and narrow profile.

Figure 12.10. Exploded view of the seven anchors comprising Ankhow’s stele (after Frost 1979: 148 fig. 3e)

The mixture of anchors with and without basal holes or apical rope grooves at Mersa Gawasis and Mirgissa—sites that are clearly Egyptian—as well as the lack of diagnostically Egyptian anchors at Tell Basta indicate that all of these anchor types were in use in pharaonic Egypt. It would, however, be virtually impossible to identify a stone anchor as specifically Egyptian unless it came from a clearly Egyptian context or had a basal hole. Without a basal hole these anchors are indistinguishable from many found along the Levantine coast, most of which are presumably of local origin.

Figure 12.11. The easternmost of the top pair of anchors forming the pedestal of Ahkhow’s stele, Wadi Gawasis (Sesostris I) (after Sayed 1977: 164 fig. 6, 163 fig. 5 [A. M. A. H. Sayad, “Discovery of the Site of the Twelfth Dynasty Port at Wadi Gawasis on the Red Sea Shore (Preliminary Report on the Excavations of the Faculty of Arts, University of Alexandria, in the Eastern Desert of Egypt–March 1976),” Rd’È 29:140–78])

Figure 12.12. Anchor that formed the pedestal of Antefoker’s stele from Wadi Gawasis (Sesostris I). The groove on the anchor’s upper surface was cut to position the stele more firmly. The anchor lacks the typically Egyptian basal rope-hole but has four notches cut on its sides (from Sayed 1980:155 fig. 2)

Of much later date are five distinctive stone anchors from the region of Alexandria: these are shaped like isosceles triangles with one or two holes at their bottom side.38 At the apex of each of the anchors is a thin, rectangular piercing cut through the narrow side of the anchors, placing them at a ninety-degree angle to the lower holes. The upper slots appear to be better fitted for the insertion of a wooden stock than for directly attaching the hawser. The unbroken anchors vary from 51 to 161 kilograms. The largest anchor, which is broken, has a calculated weight of 185 kilograms. Three of the anchors are from Ras el Soda, where a small temple to Isis existed during the Roman period. Apparently the anchor group is to be dated to that period.

Although controlled at times by Egypt in the Bronze Age, the region of Mersa Matruh was within the cultural realm of Libya.39 A. Nibbi reports about three hundred pierced stones found along a short stretch of coast at Mersa Matruh.40 At present, it is not clear what connection, if any, these stones have with Bates’ Island. Most of the stones weigh under 12 kilograms, suggesting that they were used as fishnet weights instead of anchors. One rectangular limestone block illustrated by Nibbi has a median groove and wear at its two narrow ends; it may have served as the stone sinker of a killick, or perhaps the stock of a wooden anchor.41

Israel

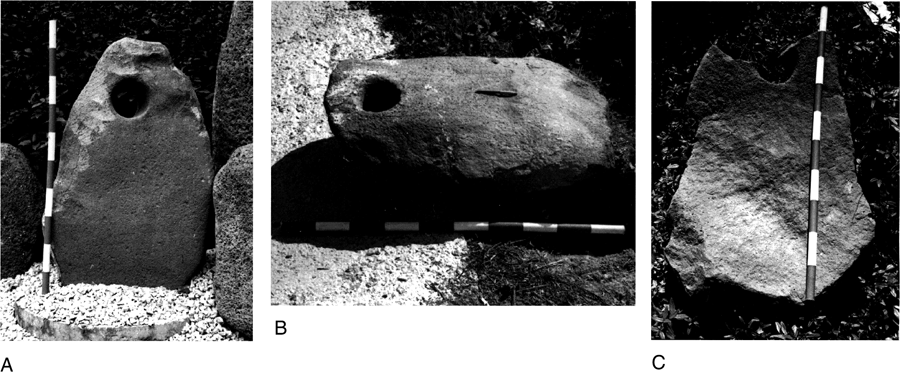

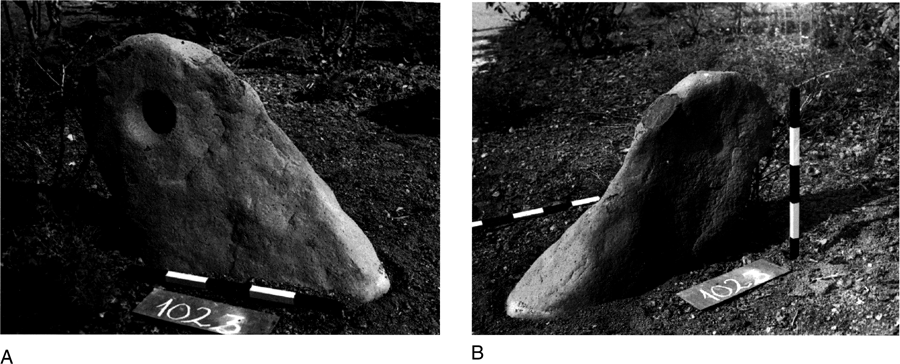

SHFIFONIM. The earliest anchor-shaped artifacts in Israel are found at land sites around the Sea of Galilee (in Hebrew, Yam Kinneret). In the excavations of Tel Beit Yerah (Khirbet Kerak), two phases of an Early Bronze Age gate were uncovered. A large basalt monolith belonging to the earlier phase was found standing upright on a stone plinth outside the gate (Fig. 12.13: A).42 The monolith was unusual in that it had a large biconical piercing in its upper extremity (Fig. 12.13: B–C). Bar Adon termed it in Hebrew a shfifon (pl. shfifonim).43 The shfifon found by Bar Adon was interesting in another respect. Although it was well cut in its upper area, its lower extremity was left unfinished, suggesting that it was meant to be placed in the ground.

Since Bar Adon’s discovery, many more shfifonim have been found around the Sea of Galilee. The majority come from fields and were discovered singly or in groups, out of archaeological context. They now grace the gardens and museums of the local kibbutzes.

Shfifonim may be divided into several types:

• Some of them have the upper area well prepared, usually in the shape of a trapezoid, while the lower extremity is left unworked (Fig. 12.14). On occasion, the natural shape of the stone is used; the base, however, is differentiated from the upper part.

• Other shfifonim reveal no significant difference between their top and bottom parts (Fig. 12.15). They come in varying, generally amorphous, shapes: some tend toward a pointed apex.

• A third subtype of particular interest includes shfifonim that were abandoned before their holes were completed. Examples of this phenomenon are rare; only three having blind holes have been recorded. One of these was found in situ in secondary use in an Early Bronze Age II stratum at Tel Beit Yerah (Fig. 12.14: A [lower left]).44 A second example is now located in Kibbutz Beit Zera (Fig. 12.16). A third specimen, with cup marks on its surface, lies outside the local museum at Kibbutz Shaar ha-Golan.45 There is also a single example of a shfifon with a second hole drilled into it, beneath its original, broken hole (Fig. 12.17).

The shfifonim are perhaps best understood as “dummy” anchors: they appear to have been intended to represent anchors and had some at present, unknown, cultic significance.46 That they were meant to represent stone anchors is implied from their limited topographical range (adjacent to the shores of the Kinneret) and their general stone-anchor shape (particularly the biconical hole).

That they may have had a cultic significance is suggested by the following considerations:

• Although the shfifonim seem to imitate stone anchors, they were created with the clear intention of placing them in the ground. The shfifon found in situ by Bar Adon indicates that they were not functional. The use of anchors and dummy anchors for cultic purposes is known from a number of land sites, both in temples and in tombs.

Figure 12.13. Shfifon found next to Early Bronze Age gate, Beit Yerah: (A–B) the shfifon standing on a stone plinth before the city gate; (C) the shfifon as it appears today (photos A–B by P. Bar Adon; photo C by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.14. Shfifonim with upper areas well prepared, while their lower extremities are left unfinished (photos A and C by the author; photo B by D. Boss; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.15. Shfifonim of amorphous shape, with no significant differences between the top and bottom parts (photos by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.16. Shfifon with a biconical blind hole (photos by D. Boss; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

• The largest boats on the Kinneret in historical times before this century measured about seven to nine meters.47 It is unlikely that craft on the lake in the Early Bronze Age were any larger. Even the majority of smaller shfifonim would be too heavy for use in these craft.

• No usable anchors in the well-cut shfifon shape have been reported from Yam Kinneret. The lake has not been extensively surveyed by divers because of its poor visibility. A long-term drought that drastically lowered the level of the lake during the late 1980s, however, did not result in the discovery of any shfifon-type anchors. Thus we have the facsimile—but not the prototype. Two shfifonim found in the water at the foot of Tel Beit Yerah probably fell from the land site as it eroded over time. The stone anchors discovered in and around the Sea of Galilee are invariably small and have narrow rope holes.48

Figure 12.17. (A) Shfifon with the remains of a hole that was broken in antiquity; subsequently, another hole was cut beneath it. (B) Detail of the upper portion of the shfifon (photos by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

• The walls and ceiling of a tomb built in the Middle Bronze Age I at Degania “A” are constructed from two shfifonim and four other monoliths:49 the floor of the tomb is a cultic basin (Figs. 12.14: A [center], 18).50 All seven pieces may have originally belonged to a single Early Bronze Age cultic installation that existed in the immediate area, perhaps at Tel Beit Yerah.51

• The cup marks on one unfinished shfifon may imply cultic connotations.

The shfifonim found in two stratigraphic excavations at Tel Beit Yerah indicate that the group cannot be dated later than the Early Bronze II period (ca. 3050–2650 B.C.).52 By the Middle Bronze I, judging from the cavalier manner in which these stones were reused in the Degania “A” tomb, they were no longer serving their original purpose. Thus, the shfifonim are at present the earliest datable anchorlike stones known from the Near East.

Interestingly, one shfifon was recently discovered serving as a reliquary underneath the altar in the central apse of a church on Mount Berenice, above the ancient site of Tiberias and overlooking the Sea of Galilee (Fig. 12.19).53 The unhewn bottom of the shfifon had been hacked away. The church on Mount Berenice was built in the sixth century A.D. and continued in use until the end of the Crusades in the thirteenth century. The excavator connects the placement of the shfifon in the church to the use of the anchor as a symbol for hope and security in early Christianity.54

This is the latest example known to me of a stone-anchorlike object used in a cultic manner. Thus, the Sea of Galilee seems to have the notable distinction of being the location of the earliest—and latest—evidence for stone anchors or their facsimiles.

ANCHORS. Israel’s Mediterranean coast abounds in stone anchors.55 Rare indeed is the dive in which at least one stone anchor is not sighted. Scores of anchors of varying shape and size have been recorded underwater at Dor alone (Fig. 12.20).56 As opposed to the situation in Bronze Age coastal sites in Lebanon, Syria, and Cyprus, however, very few anchors have been found on land in Israel. This makes dating and identifying the sea anchors difficult. The following is a brief summary of the most significant published finds.

A pair of anchors, each bearing the incised drawing of a quarter rudder, was recovered at Megadim (Fig. 12.21).57 The tillers point respectively to the right and left, perhaps indicating that they were the ship’s (stern?) starboard and port anchors. R. R. Stieglitz identifies the quarter-rudder pictographs as the Egyptian hieroglyph ym and the anchors as Egyptian. This classification has been generally accepted.58

Figure 12.18. (A) A shfifon in secondary use serves as a monolithic cover on the Middle Bronze Age I built tomb excavated at Kibbutz Degania “A” in 1971. The hole had been plugged with a stone in antiquity. (B) The same tomb after removal of the shfifon and monolithic stele that formed the tomb’s roof. A second shfifon served as the tomb’s southern wall (photos courtesy of M. Kochavi)

The identification of these anchors as Egyptian is questionable, in my view. Many stone anchors found in Israeli waters, presumably of Syro-Canaanite origin, are rectangular with a rounded top, similar to the two Megadim anchors discussed here. The Megadim anchors lack the attributes that define Egyptian anchors—particularly the L-shaped notch. The only reason to claim that they are Egyptian is the quarter-rudder pictograph on each. This is, however, only a single symbol, not a hieroglyphic inscription: anyone could have made the signs of a ship’s quarter rudder without being Egyptian, or without even intending to represent an Egyptian hieroglyph.59

The same ship that left the “quarter-rudder” anchors may have left behind an additional pair of inscribed anchors at Megadim.60 One anchor bears an hourglass-like symbol (Fig. 12.22: B). The companion anchor, which is identical in shape to the “quarter-rudder” anchors, is an ashlar block doing secondary duty as an anchor. It bears part of an Egyptian relief on one of its narrow sides (Fig. 12.22: A, C). Presumably the stone had been removed from a building in Egypt, although even this is not definite.61 The relief does not make the anchor itself Egyptian; it lacks the L-shaped notch and apical groove, and its shape is compatible with a Syro-Canaanite origin.

Several other stone anchors from the Mediterranean coast of Israel bear signs. One anchor, found in the sea near Dor, has an H-shaped design incised into one of its narrow sides (Fig. 12.23). Another anchor, bearing a turtle-like design, was found opposite Kfar Samir, south of Haifa.62

Figure 12.19. The shfifon from the Byzantine-period church on Mt. Berenice (photo and drawing courtesy of Y. Hirschfeld.)

In his description of Stratum V at Tell Abu Hawam, R. W. Hamilton notes (Figs. 12.24–25): “The pavement at the north-west corner of 53 contains a large perforated stone—perhaps a door socket, or more probably a drain, since the hole penetrates to the sand and there are no signs of the attrition that would be caused by a door on the surface of the stone. Similar pierced stones were inserted in a pavement at 57 in F 5.”63

These pierced stones are, of course, anchors (Figs. 12.26–27).64 They are now lost to the archaeological record, and it is difficult to describe a typology from Hamilton’s stratum plan and the photos discussed by J. Balensi. Recent excavations at Tell Abu Hawam have revealed six additional stone anchors.65 Three anchors were found in secondary use in strata dating from the Late Bronze Age to the fourth century B.C.; the remaining three lacked archaeological context.66 Anchors also have been found in the Bronze Age strata of Tel Acco.67 Another stone anchor was discovered in secondary use at Tel Shiqmona near Haifa in a stratum dating to the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.68

Figure 12.20. A stone anchor found in the ancient harbor of Dor (photo by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.21. Two limestone anchors with quarter rudder pictographs having tillers facing right and left respectively. Found together on the Carmel coast (photo by the author)

Figure 12.22. Two anchors found together at Megadim: (A) anchor with remnants of an Egyptian relief on one of its narrow sides; (B) anchor with an “hourglass” design; (C) detail of the Egyptian relief fragment on anchor A and a schematic cross-section of a leg (after Galili and Raveh 1988: 43 fig. 3, 44 figs. 5–6; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.23. The stone anchor seen in situ in fig. 12.20 has a sign on one of its narrow sides (from the ancient harbor of Dor) (photo by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.24. Tell Abu Hawam Stratum V, showing find spots of stone anchors at loci 53 and 57 (from Hamilton 1935: pl. 11; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.25. Details of locations of stone anchors found in Tell Abu Hawam Stratum V at loci 53 and 57 (from Hamilton 1935: pl. 11; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Figure 12.26. Stone anchor at Tell Abu Hawam Stratum V, locus 53 (courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

ANCHORS IN INLAND WATERS. A number of stone anchors have been reported from the Sea of Galilee, but most of them lack an archaeological context. Two stone anchors were found in the Iron Age strata at Tel Ein Gev.69 One anchor, made of limestone, is rectangular with a rounded top and weighs 41 kilograms. The second stone is probably a net weight: it is made of local basalt and weighs 7.5 kilograms. Two stone anchors, the first to be discovered and identified as such in the Sea of Galilee, were found together with twenty-nine cooking pots by the Link Expedition near Migdal: this complex probably represents a boat’s cargo and equipment. The pottery dates from the mid-first century B.C. to the mid-second century A.D.70 TWO stone anchors were discovered out of stratigraphic context, in the vicinity of the Kinneret boat.71

Two other pierced stones, probably anchors, were found in secondary use during the excavation of Khan Minya (Mamaluke-Ottoman periods) on the northwest shore of the lake.72 J. MacGregor described a stone at Capernaum that may be the stone stock of a wooden anchor.73

Several stone anchors are known from the shores of the Dead Sea. A single stone anchor, apparently of Roman date, was reported from Rujm el Bahr.74 Four more were found near Ein Gedi.75 Two of these anchors still had remains of rope hawsers, the longest being 1.6 meters long. Radiocarbon dating of the rope suggests a date around the fourth to third centuries B.C. The rope was found to be double-stranded. This is the only rope reported from nonmodern stone anchors.

In general, it appears that stone anchors continued to be used on both the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea well into Classical times and probably later.

Lebanon

BYBLOS. Twenty-eight stone anchors were located in the excavations of Byblos.76 Seven were found in and around the Temple of the Obelisks (Fig. 12.28:1–4, 7–9). They date from the nineteenth to the sixteenth centuries B.C. TWO anchors, both triangular, are definitely in a sacred context: standing upright on a bench-shelf against the wall of the” Amorite” chapel next to the Temple of the Obelisks. This chapel had votive obelisks, one of which was dedicated to Herchef or Reshef. Frost assumes that the two anchors served the same purpose. Another triangular anchor was found resting on the northern side of the temenos wall that surrounded the cella.

Figure 12.27. Stone anchors at Tell Abu Hawam Stratum V, locus 57 (courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

The lowest step of the stairs leading up to the Tower Temple is constructed of six chalk “dummy” anchors set in a row (Fig. 12.28: 23–28).77 This temple dates to the twenty-third century B.C. Only the top face of the anchors has been worked: this, along with their find spot, indicates to Frost that these were in themselves offerings. She suggests that the number of anchors may reveal the complement of anchors carried by a single ship.

Figure 12.30. “Byblian” anchor found between the islands of Hofami and Tafat at Dor (drawing by E. T. Perry; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

Three more anchors, dated to the twenty-third through twenty-first centuries B.C., were also found in the enclosure (Fig. 12.28: 17–18, 22). Nine other anchors were discovered in secondary use in later strata (Fig. 12.28: 10–16, 19–20).

With the exception of one undated anchor, all those found at Byblos are weight-anchors. Frost defines the typical Byblos anchor shape as a tall, equilateral stone slab with one apical hole; above the hole is a well-defined rope groove. The hawser hole is round and biconical: the latter attribute is best illustrated in an unfinished anchor with a blind hole (Fig. 12.28: 11). The anchors are of medium size at Byblos; here, the gigantism of the Ugarit and Kition anchors is lacking.78 The largest anchors at Byblos are calculated to weigh about 250 kilograms. The similarity between Byblian and Egyptian anchors may result from Egyptian influence at Byblos.79

Interestingly, at Byblos itself the “Byblian” anchor is not in the majority. Only six of the large-size anchors have the characteristic triangular shape (Fig. 12.28: 1, 3–4, 15–16, 18). Perhaps anchors were normally contributed to the temple by nonlocal seafarers, as, for example, must be the case of the Egyptian anchor found at Byblos (Fig. 12.28: 21).

Most “Byblian” anchors known to date come from off the Israeli Mediterranean coast.80 A group of fifteen stone anchors of Frost’s Byblian type was found at Naveh Yam (Fig. 12.29); another was found south of Dor, between the islands of Hofami and Tafat at the entrance to Tantura Lagoon (Figs. 12.30–31). Another “Byblian” anchor was located two kilometers north of the Megadim anchors, between Megadim and Hahotrim (Fig. 12.32).81 The same site contained a Canaanite jar: the relationship between the anchor and the amphora, however, is unclear. A Byblian anchor is also reported from Cape Lara, on the southeast tip of Cyprus.82

Syria

UGARIT. Frost describes forty-three stone anchors found at Ugarit and its main port, Minet el Beida.83 Of these, twenty-two are located in or around the Temple of Baal (Figs. 12.33: 1–17).84 The Ugaritic anchors have three main shapes: an elongated rectangle, a squat rectangle, and a triangle. Four of the anchors weigh about half a ton each (Fig. 12.33: 2–3, 5–6).

C. F. A. Schaeffer dates the level of the temple in which the anchors were found to the reigns of Sesostris II through Amenemhet IV. Interestingly, the nearby Temple of Dagon lacked any anchors whatsoever. It appears that anchors were dedicated to specific gods, most probably those (like Baal) in charge of the weather. Two anchors, for which Frost proposes a fifteenth- or fourteenth-century date, were found flanking the entrance to a tomb (Fig. 12.33: 27–28).85 These anchors find a close parallel in one discovered underwater at Dor.86

Cyprus

Cypriot Late Bronze Age harbor sites are rich in stone anchors. Many others have been found in underwater surveys. The earliest published pierced stone from Cyprus dates to the sixth millennium and was found in Stratum III at Khirokitia (Fig. 12.34).87 The stone is roughly triangular with a small biconical piercing and an apical rope groove. It weighs 10.4 kilograms and is probably a net weight. In Israel to this day, stones still serve as net weights for some fishermen (Fig. 12.35).

Figure 12.31. A “Byblian” anchor from Dor (courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

HALA SULTAN TEKE. A number of anchors have been found in the land excavations at Hala Sultan Teke and in the neighboring underwater site of Cape Kiti (Figs. 12.36–39).88 Numerous stone anchors were also discovered off Cape Andreas (Figs. 12.40–42).89

KITION. The largest single group of anchors from an excavated land site comes from Kition, where some 147 stone anchors have been recorded in the temple complexes (Fig. 12.43).90 Frost notes a “family resemblance” between the anchors from Ugarit and those from Kition.91

At Kition anchors were classified by lithological thin sections.92 Three anchors were found to be of stone foreign to the site.93 The stone of one anchor was identified as originating in Turkey or Egypt. This, however, does not necessarily indicate a foreign ship, for vessels could have picked up stone blanks for their anchors anywhere and prepared them on board while under sail.

Figure 12.32. “Byblian” anchor found between Megadim and Hahotrim (after Ronen and Olami 1978:10 no. 21:1; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

The Kition anchors are squat with rounded corners and range in shape from rectangular to triangular.94 They resemble Ugaritic anchors but contrast markedly with the triangular Byblian shape. A style of anchor that Frost defines as regional to Kition is composite and has a rounded, triangular shape. This kind of anchor seems to be far-ranging. Frost mentions examples found off the island of Ustica and also discovered together with a metal ingot off Cape Kaliakri, in the Black Sea. Several of this variety were also found underwater at Cape Andreas, Hala Sultan Teke, and Cape Kiti (Figs. 12.36: A [1–2], 37: C, E, 38: L–M, 41: A–D). Three such anchors bear the three–line Cypro-Minoan arrow sign (Fig. 12.36: A [1, 3].95 The Karnak anchor has this typical Cypriot shape but is made of local limestone (Fig. 12.44).96

Fifteen of the Kition anchors have a rectangular shape first noted on an embedded anchor (?) in the tomb of Mereruka (Fig. 12.6: B). Since the Mereruka anchor predates those at Kition by nearly a millennium, this only establishes that the shape was a common one.97

Turkey

A number of unpublished stone composite- and weight-anchors are exhibited in the courtyard of the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology.98 We know nothing of stone anchors used by Late Bronze Age Anatolian seafarers.

Figure 12.35. Fishing boat with net that employs stone weights (Acco, Israel). Inset: detail of one of the stones {photos by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

The Aegean

Very few stone anchors are known from the Aegean. Since Aegean Bronze Age seafarers needed some form of anchoring device as much as others of their day, it is not clear why stone anchors appear to be so rare on the Aegean seabed. Perhaps this is because of the steep nature of the sea floor there, compounded by the nearly total lack of sport diving in Greece.

Alternatively, perhaps Aegean seafarers used killicks, devices that utilize stones as weights for a wooden anchoring structure.99 Since fieldstones of a desired shape can be used in killicks, these would leave no archaeological trace once the artifact’s organic structure had decomposed. Furthermore, few stone anchors have been found on land, apparently because anchors were not normally dedicated in cultic contexts in the Minoan and Mycenaean religions.100

Figure 12.36. Stone anchors from Hala Sultan Teke (A from Frost 1970A: 14 fig. I; B from Öbrink 1979: 72 figs. 102A–102)

Figure 12.37. Stone anchors from Hala Sultan Teke (A–C from Hult 1977:149 figs. 170–71; 1981: 89 fig. 140; D–F from McCaslin 1978:119 fig. 215, nos. N4000, F4004, N9040)

Figure 12.39. Stone anchors sighted near the lighthouse at Cape Kiti (after Herscher and Nyquist 1975: figs. 48: 2–5, 49: 7, 9)

Figure 12.40. Stone anchors from three anchor sites near Cape Andreas, Cyprus (from Green 1973: 170 fig. 30)

Figure 12.41. Stone anchors from anchor sites at Cape Andreas, Ayios Philos (Philon), Ayios Photios, Aphrendrika (Ourania), and Khelones, Cyprus (from Green 1973: 173 fig. 31 A)

MAINLAND GREECE. At present, the typology of Mycenaean anchors remains unknown. Two stone anchors—one round, the other somewhat rectangular—were recovered off Cape Stomi at Marathon Bay.101 A three-holed composite anchor was discovered off Point Iria near a concentration of Late Helladic pottery.102

DOKOS. Two stone anchors were recovered from the Dokos site.103 The anchors weigh about twenty kilograms each and are of nondescript shape, with small rope holes. The excavators have tentatively dated these to the Early Helladic period, suggesting that they are derived from a ship from that period that had wrecked at the site. Since these anchors are of a size, type, and style that continued in common use throughout the Mediterranean into modern times, this conclusion seems to overstep the available evidence.

CRETE. Three Middle Minoan stone anchors were found at Mallia (Fig. 12.45: A–C).104 The area where two of the anchors were found was originally thought to be a stonemason’s workshop but has more recently been identified as a sanctuary.105 All three of the anchors have a triangular shape with a rounded top; one has a square rope hole. The stones were freshly cut, suggesting that they had never seen service in the sea.

A beautifully carved pierced porphyry stone, decorated with a Minoan-style octopus, was found by A. Evans at Knossos (Fig. 12.45: D).106 The stone weighs twenty-nine kilograms: Evans believed it was a weight for weighing oxhide ingots. This artifact is so elaborate, however, that it may have been intended for cultic use.107

Five pierced stones, originally identified as anchors, were found in a Late Minoan III context at Kommos (Fig. 12.46: D).108 H. Blitzer later thought that some of these stones were weights used in olive presses instead of anchors.109 During the summer of 1993, two Bronze Age stone anchors were discovered within the Minoan civic buildings at Kommos (Fig. 12.46: A–C).110 The anchors are composite, with one large hole at the apex and two smaller holes near the bottom. The larger of the two anchors is 74 centimeters high, 60 centimeters wide at the bottom, and 15 centimeters thick. It weighs 75 kilograms. This is the first recorded discovery of three-holed composite-anchors reported from a land site in the Aegean. The latter two anchors were reused as bases for wooden supports. They date to the Late Minoan IIIA1–A2 and were found together with Canaanite, Cypriot, and Egyptian as well as local Minoan sherds.

Figure 12.42. Stone anchors from anchor sites at Cape Andreas, Ayios Philos (Philon), Ayios Photios, Aphrendrika (Ourania), and Khelones, Cyprus {from Green 1973:173 fig. 31B)

Another broken anchor, perhaps of Late Minoan IB date, was found at Makrygialos.111

THERA. S. Marinatos identifies a pierced stone found at Thera as an anchor (Fig. 12.47). The rope hole is exceptionally small (about 4 centimeters) for the stone’s 65-kilogram weight, and it is difficult to understand how the stone could have served as an anchor without having some additional form of binding. The stone is described by Marinatos as being “roughly oval, black trachyte stone, about 60 cm long.” He mentions two additional pierced stones, found in Sector Δ, but gives no further details.112

Figure 12.44. The Karnak anchor. This anchor, although made from local limestone has a diagnostic Cypriot shape. The anchor was found in the Temple of Amun at Karnak {photo by L. Basch. Courtesy of L. Basch)

Figure 12.45. (A–B) Stone anchors excavated at Mallia, ca. nineteenth century B.C. Estimated weight: about twenty-five and forty kilograms. (C) Stone anchor from Mallia, ca. 1750 B.C. Estimated weight: sixty kilograms. (D) Porphyry anchor-shaped weight (?). The stone is decorated in relief with an octopus (A–D after Frost 1973: 400 fig. 1:6)

MYKONOS. A three-holed composite anchor is exhibited at the Aegean Maritime Museum on the island of Mykonos.113

RHODES. An anchor was found in Tomb 27 at Ialysos.114

Anchors on Shipwrecks

ULUBURUN. Twenty-four stone anchors have been found on the Uluburun wreck (Figs. 9.1; 12.48: A–B; 14.1).115 Most are made of sandstone; two small anchors consist of hard, white, marblelike limestone. Eight anchors, including the two smaller ones, had been carried in the center of the hull between two stacks of copper oxhide ingots. Sixteen other anchors are located at the bow, in the lower perimeter of the wreck.116 A study of the site plans and photos published to date suggests several distinctions:117

Figure 12.46. Anchors from Kommos: (A and B facing page) (A) anchor S2233 (Late Minoan IIIA1–2); (B) anchor S2234 (Late Minoan IIIA1–2); (C) anchor S2233 in situ; (D) pierced stones (anchors?) at Kommos (Late Minoan III) (A–C courtesy Drs. J. and M. Shaw; D from Shaw and Blitzer 1983: 94–95 fig. 2)

• All are weight-anchors, each with a single hole.

• The anchor shapes vary from trapezoidal with truncated top to roughly triangular with rounded top.

• At least six of the anchors have square rope holes.

• No rope grooves are visible on the plans or in the published photos of the anchors.

Because anchors in use were carried primarily at a ship’s bow, the fact that so many anchors were found at the lower end of the wreck supports the conclusion that this is the craft’s bow. The ship may have lost some of her anchors attempting to avoid the coast. The large number of stone anchors carried by the Uluburun ship seems indicative of both the anchors’ expendability as well as their unreliability. Presumably, the ship also carried quantities of rope for use with the anchors, although no rope has been reported from the excavation. At present the closest parallels on land sites to the Uluburun anchors, as a group, seem to come from Ugarit, Kition, and Byblos.118 Six of the anchors that have been weighed varied between 121 and 208 kilograms.119 Based on their average weight, the twenty-four anchors on the Uluburun ship weigh over four tons!

CAPE GELIDONYA. During the 1960 excavation of the Cape Gelidonya shipwreck, no stone anchors were found. Their absence at the site remained an enigma that became even more remarkable when seen in contrast to the twenty-four anchors recovered at Uluburun. During the 1994 Institute of Nautical Archaeology underwater survey off Turkey, the team located and raised a single stone anchor at Cape Gelidonya (Fig. 12.48: C).120 This is a large weight anchor that weighs 219 kilograms and is made of sandstone of a type somewhat more coarse than the Uluburun anchors.

Figure 12.48. (A) (opposite page) Stone weight anchors spill down from the lower part (bow) of the Uluburun shipwreck (B) The difficulty in deploying heavy stone anchors at sea is demonstrated in this photo, which shows members of the Uluburun excavation moving one (C) The stone anchor recently discovered at Cape Gelidonya, in the process of being weighed by Cemal Pulak (photos by D. Frey; courtesy of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology)

The Gelidonya ship undoubtedly carried additional anchors. Where are they? Perhaps some had been lowered by the crew in a desperate attempt to prevent the ship from crashing into the rocks.121 If so, they would now be located in deeper waters. Another possibility is that a significant portion of the shipwreck is still missing.

NAVEH YAM. The Naveh Yam anchors must have come from a single ship (Fig. 12.29).122 The majority of the anchors are triangular, have apical rope grooves on both of their flat sides, and range in weight from 60 to 155 kilograms; their original weight, not including three broken anchors, totals 1,187 kilograms.123

E. Galili divides the anchors into the following groups: anchors with rope grooves on both sides (Fig. 12.29: 1, 3–4, 6–8, 10, 13–15); an anchor without rope grooves (Fig. 12.29: 5); an anchor with a rope groove on only one side (Fig. 12.29: 12); broken anchors (Fig. 12.29: 2, 11, 16); and an elliptical anchor of non-Byblian shape (Fig. 12.29: 9). Five of the anchors have bases flat enough to allow them to stand independently on a flat surface. They are all made of soft limestone, exposures of which are known from Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and Syria. Two hematite weights, a bronze chisel, and a bronze adze were also found near the anchors.

At Naveh Yam, anchors having rope grooves on both sides, on only one side, and without any grooves at all were found side by side, indicating that a single ship could carry a variety of anchors types. Most of the Naveh Yam anchors were found in an area of seven-by-seven meters on the seabed.124 Two of the anchors, among the largest in the group, were discovered at some distance from the rest (Fig. 12.29: 1, 4).

The tops of the broken anchors were missing. Galili suggests that some of the anchors—at least the broken ones—served as the ship’s ballast. He believes that the anchor site is the result of a shipwreck caused by the vessel hitting an underwater reef located directly southwest of the site.125

Discussion

Small Anchors

At Wadi Gawasis, at Naveh Yam, as well as at Uluburun, groups of large stone anchors have been found in situ, together with smaller anchors that could not have been functional for the same craft in the same manner as the larger anchors.126 What purpose did these small anchors serve? There are three possible explanations for this phenomenon: they may represent hawser weights, sacred anchors, or the anchors for ships’ boats. Let us examine the evidence for each of these possibilities.

HAWSER WEIGHTS. A modern anchor chain serves as a “shock absorber” in rough seas. For a ship rocked by waves while standing on a stone anchor with a rope hawser, however, the situation is quite different. Notes H. Wallace:

Indeed if the seas approach the height of his bows, A’s situation [Fig. 12.49] could be desperate, since it is certain that one or more of three unpleasant things must happen: the anchor is lifted clear of the bottom with every wave, or if so much weight is placed on it or it wedges in a cleft, and so cannot lift, either the rope will break or the waves will break over the bows of the ship which cannot rise to them. Even if the height of the waves is much less, they will still give A a most uncomfortable ride, the rope going slack when the ship descends into the trough and then tightening with a jerk as it rises. Even the heaviest anchor with rope can’t stand this treatment for very long.

Contrast now the cases of B and C which can rise with the waves to B1 and C2 respectively before they are faced with the troubles we have described for A. And all the time there is a tension on the rope or chain so that there is no jerk till all is off the bottom and the ship attempts to lift the anchor. This point, of course, should never be reached if chain of sufficient length and weight in relation to the size of the ship and the waves is used.127

Figure 12.49. The difference between rope and chain when anchoring in waves {after Wallace 1964: 15 fig. 1)

Wallace suggests that auxiliary stone anchors were attached to the primary hawser to act in the same manner as a chain.128 He notes that this method was still being used on Spanish fishing boats in recent times:

However, in this case the weights were not attached directly to the anchor cable, but were strung along an auxiliary line which was only attached to the main cable at intervals and hung down in loops in between. Though at first sight puzzling, this method of attachment would appear to have advantages for larger boats when it came to hauling in the anchor, as if the weights were attached direct to the main cable [as in Fig. 12.50], it would be necessary to lift the whole cable whenever a weight came up to the gunwale—not an easy thing to do while still maintaining the tension on it. But with the weights on an auxiliary line a separate detachment of the crew could bring the weights inboard, without interrupting the main party hauling on the main cable.129

Another possible reason for the anchors’ being attached on a separate line is that they would have been likely to foul anchor lines in a crowded harbor. Wallace notes that similar weights were used on the tidal reaches of the Thames.

Frost opposes this interpretation:

I have a file of letters telling me that in order to counteract the potential dragging of a stone weight attached to a boat by rope, the ancients must also have weighted the rope itself with smaller pierced stones so that it would lie along the bottom like a chain, thus preventing surface movement from being transmitted to the anchor. This is logical but again it runs counter to the evidence, because had the weighting of ropes been common practise, then sets of smaller pierced stones each weighing a few kilos would be found beside the larger stone anchors on all the groups of lost anchors that have been examined and surveyed during the past thirty years and this is never the case.130

Figure 12.50. Theoretical reconstruction of subsidiary anchors used to weigh down an anchor’s rope hawser (after Wallace 1964:16 fig. 3)

The evidence is not quite so clear-cut. First, anchor sites often contain large and small anchors jumbled together haphazardly, making it possible that two or more had been combined on a single hawser. It is virtually impossible to prove this because of the jumble of stone anchors on the seabed. Second, sets of weights need not be postulated: a single subsidiary anchor placed up the hawser from the primary anchor would have been sufficient in most weather to function as a brake on the main anchor.

Perhaps the strongest argument against small weight-anchors having been used as hawser weights is the consideration that so few of them are found with the large anchor groups. Had the small anchors been used as hawser weights, one would have expected to find more of them at Wadi Gawasis, Naveh Yam, and Uluburun.

SACRED ANCHOR. Seagoing ships normally have an additional anchor to be used as a last resort should the bower anchors fail to hold. This is now termed a sheet anchor.131 In antiquity, this anchor had cultic connotations and was considered sacred. Perhaps the small anchors at these sites are “sacred” anchors.

Appolonius of Rhodes (third century B.C.) gives a detailed account of the dedication by the Argonauts of an anchor at a spring sacred to Artacie.132 The helmsman, Typhis, suggests that they dedicate their small stone anchor and replace it on the Argo with a heavier anchor. Presumably, if there was a small anchor, it was small in relation to other, larger, anchors. But why dedicate the small anchor? Was this perhaps the holy anchor?

Frost suggests that the anchor being raised by a ship on a Cypriot jug represents that ship’s holy anchor (Fig. 8.41: A).133 The large figure above the anchor, in her opinion, is a deity, his hands held in benediction, who, hearing the distress call signified by the dropping of the holy anchor, has come to save the ship.134

SHIP’S BOAT’S ANCHOR. Bass and C. M. Pulak suggest that the small anchor found at Uluburun was either a hawser weight or a spare for the ship’s boat.135 Similarly, A. M. A. H. Sayed notes that the small anchor found at Mersa Gawasis was possibly used for a small “rescue” boat.136

It is probable that a ship like the one that wrecked at Uluburun—which was capable of carrying four tons of anchors—would have had a tender. Indeed, in the Deir el Bahri relief, a launch is depicted transporting Egyptian trade items to the shore at Punt (Fig. 12.51). The Egyptians must have brought such launches with them, even though none is portrayed on board the ships.137 In conclusion, at present it seems preferable to explain the small anchors as belonging on ships’ boats.

Brobdingnagian Anchors

The heaviest anchors yet recorded come from Kition (Fig. 12.52: D–E).138 The largest of these has a calculated weight of about 1,350 kilograms. Frost assumes that all the largest anchors found at Kition were functional; that is, they were actually used on ships. It seems prudent, however, to restrict the upper weight limit of stone anchors that were used at sea during the Bronze Age to the weight of the largest specimens actually found on the seabed.

Two half-ton anchors found on the Mediterranean seabed have been published.139 One of these comes from the harbor of Tabarja in Lebanon and is presumably of Middle or Late Bronze Age date (Fig. 12.53).140 The other is one of two anchors found together with Late Bronze Age scrap metal off Hahotrim, south of Haifa on the Israeli Mediterranean coast (Fig. 12.54). Two other large anchors, made of basalt, have been recorded by divers off Tartous and Cape Greco.141 Even these half-ton anchors must have been difficult to manage in the primitive manner depicted on the Cypriot jugs.

Later wooden anchors reached unusually large proportions. The largest recorded lead stock from the Mediterranean is 4.2 meters long and weighs 1,869 kilograms.142 Anchors of this size must have been handled with capstans, for which there is ample evidence in the Classical period.143 However, there is nothing to indicate that pulleys and capstans were known in the Bronze Age—or during most of the Iron Age, for that matter, to judge from the Cypriot vases.

Figure 12.51. Detail of a ship’s boat ferrying trade goods to the coast at Punt (Deir el Bahri) (from Naville 1898: pl. 72)

Square Hawser Holes

The rope situated between the hawser hole and the anchor’s apex will chafe as a stone anchor is dragged on the seabed or as it rises and falls with the waves on the ship. This part of the hawser would have worn out most often. The rope grooves observed on Egyptian and Byblian anchors were apparently an attempt to avoid the inevitable damage done to this part of the rope, as well as to seat the eye.

Figure 12.52. Stone anchors at Kition (Late Cypriot IIIA): (A–C) pairs of stone anchors; (D) the largest anchor at Kition (weight ca. 1.35 metric tons); (E) large anchor (weight ca. 700 kilograms) (from Frost 1986C: 297 fig. 4: 1–4, 302 fig. 7: 4–7)

In antiquity, a short piece of rope may have been passed through the hawser hole and spliced, forming an eye, or ring. The hawser would then be attached to the eye. When the eye wore out, it would have been easily replaced without doing any damage to the hawser. Such an eye is visible on the triangular stone anchor on a Cypriot jug (Fig. 8.41: A).144 Composite stone anchors called sinn (Arabic for “tooth”), used by Arab craft in the Persian Gulf, are still attached in this manner.145

There is another reason for having such a rope eye on heavy stone anchors. The eye would enable a wooden staff to be inserted, allowing the anchor to be manhandled by two or more men once it broke the water and was brought on deck.

Figure 12.53. Half-ton stone anchor found in the harbor of Tabarja, Lebanon (from Frost 1963B: 43 fig. 5)

Frost rightly notes that, functionally, square rope holes are difficult to explain (Fig. 12.55).146 It is indeed patently illogical to cut a square hole for a rope that is round in section. The square holes noted on anchors from Ugarit, Kition, and Uluburun must therefore have had a technological raison d’être.

Figure 12.54. Brobdingnagian stone anchor found near Late Bronze Age metal artifacts around Kibbutz Hahotrim. In fig. A, the anchor, with an estimated weight of about half a ton, is seen in situ on the seabed (photo by the author; courtesy Israel Antiquities Authority)

These square holes may have resulted from a preference to pass four or five smaller eyes, instead of one big eye, through the hole (Fig. 12.56). If one or two of the eyes parted, the anchor would still not be lost. Perhaps anchors with square holes were used when anchoring on a rocky bottom when the eye was more likely to chafe, while anchors with round holes were reserved for sandy bottoms. In later times, chafing was avoided by placing the hawser hole on the narrow side of the anchor.147 In support of this explanation, note that the rope hawser of the stone anchor from the Hellenistic period found near Ein Gedi—the only hawser yet found in connection with an ancient stone anchor—was made of two separate ropes.148

Figure 12.55. Stone anchors from Kition with square hawser-holes (from Frost 1986C: 312 fig. 12:15, 317 fig. 14: 2, 310 fig. 4)

Figure 12.56. A square rope-hole suggests that it was intended for four (A) or even five (B) smaller cables instead of one large cable (drawn by the author)

One type of Cypriot stone anchor has an exceptionally large anchor hole that seems nonfunctional (Figs. 12.38: C, G, 40: G, E, 57)149 Specimens found on the seabed signify that this anchor type was indeed used at sea, however.

An anchor found underwater near the lighthouse at Cape Kiti has a blind hole (Fig. 12.39: B). I have seen another unfinished anchor on the seabed at Dor. These two artifacts suggest that stone blanks were, at least on occasion, taken aboard ship and prepared while the craft was at sea.

Anchors Found in Cultic Connotations

Anchors found in temples at Byblos, Ugarit, and Kition share common features in their positioning.150 These features include their use as betyls standing over bothroi, anchors standing upright among other votive offerings, as well as the inclusion of groups of anchors as part of the temple architecture but serving no structural purpose.151 They also appear in tombs, near or in wells, and aligned in thresholds and walls, normally in sets of two, three, four, and six (Figs. 12.28: 23–28, 58).

Figure 12.57. Two “basket-shaped” anchors from the sea off Cyprus (from Frost 1970A: 21 fig. 4:7,11)

Cup marks, presumably indicative of cultic practices, are occasionally found on stone anchors uncovered in temple precincts. Frost suggests that at Kition, the anchors were made in and for the temples. Unfinished anchors were found at Byblos, Kition, and among the shfifonim.

Many anchors at Kition were found in pairs (Fig. 12.52: A–C).152 In Byblos, a pair of anchors was found in the dromos of a tomb (Fig. 12.33: 27–28). This apparent cultic connection to a pair of anchors may be traceable to the manner in which pairs of anchors were used in the sea. At Dor, two large, virtually identical anchors were found lying in situ on the seabed in a manner that suggests the ship had lowered the two anchors from one end and had moored between them.153 Six of the Kition anchors and eight of the Ugaritic ones exhibit signs of burning, also apparently caused by cultic operations.154

Figure 12.58. Anchors in groups in the walls of Temple 4 at Kition (Late Cypriot IIIA) (from Frost 1986C: 301 fig. 6)

Why are so many anchors found in certain areas of the Mediterranean seabed? Some were no doubt left behind when the hawser parted. Also, anchors must have been considered expendable: some may have had their hawsers cut to allow a hasty retreat when it was necessary to escape danger. Raising an anchor in the manner portrayed on the Cypriot jugs would have been extremely dangerous in any kind of sea. Just manhandling an anchor weighing 150 to 200 kilograms aboard a ship in quiet waters is difficult enough, as the staff of the Uluburun excavation came to realize (Fig. 12.48: B). No doubt a Bronze Age captain would have preferred to cut his hawser rather than have a quarter-ton (or more) stone anchor swinging wildly over his fragile wooden hull as it was lifted on board.

Sedimentation may be another cause for leaving anchors behind on the seabed. On shallow, sandy shores, storms can displace enormous amounts of sand in a relatively short time. At the end of a storm, a ship anchored in a “proto-harbor” may have found its anchors buried so deeply in the sand that they could not be raised.

Some stone anchor groups found in the breaker zone may have been left behind because it is impossible to kedge with stone anchors. Thus, in order to float free, a ship stuck on a sandbank could only resort to lightening herself. In all likelihood the first items to go overboard were the anchors, as these could be most readily replaced.

* * *

Anchors are a major element for the study of Bronze Age seafaring, but anchor research is still in a formative stage. Although important strides have been made in the study of Bronze Age anchors, much remains unknown, and a definitive corpus of all known anchors is urgently needed. There remain entire regions that are terra incognita vis-à-vis stone anchors. We know almost nothing of the anchors of Mycenaean Greece or the Anatolian coast, for example. What kind of anchors was used by the seafaring merchants of Ura? We do not know. Similarly, the typology of Canaanite anchors has yet to be defined.