Figure 11.1. The four positions of oarsmen in the Deir el Bahri reliefs (after Jarrett-Bell 1930:12 fig. 1)

Propulsion

Before the introduction of motorized water transport in the nineteenth century, seagoing ships were propelled by manpower or by using the inherent energy of the weather. Once man learned to harness the wind, it became a significant form of ship propulsion. Even with today’s modern technology, “turbo sails” are being considered to harness wind power and to cut fuel costs on motorized transport.1 The ability—or lack thereof—to utilize wind power had a profound influence on sea routes and navigation in antiquity.

Paddles and Oars

The earliest seagoing vessels were paddled: rowing was a later development. The first evidence for the rowing of seagoing ships appears on those of Sahure and Unas (Figs. 2.2–3, 5, 7). Paddling, however, continued into the latter part of the Bronze Age on small craft and in cultic use (Figs. 6.13, 23: A, 24, 42).2

The rowing of Hatshepsut’s Punt ships has attracted scholarly attention. G. A. Ballard argues that Hatshepsut’s vessels were rowed with long sweeps because the oarsmen are standing up to pull on their oars (Figs. 2.15, 18).3 He theorizes that the men stood near the ships’ longitudinal median line but were foreshortened by the Egyptian artist.

C. D. Jarrett-Bell used the four positions depicted at Deir el Bahri in the scenes of the voyage to Punt, a procession on the Nile, and the moving of the obelisk barge to reconstruct a single entire stroke.4 At the beginning of the stroke the oarsmen sit leaning forward, with their oars at a forty-degree angle from the vertical (Fig. 11.1: A). In the next stage they are still sitting and leaning forward, but with their oars now at an angle of twenty-eight degrees (Fig. 11.1: B). They then stand up and lean backward with the oars at a fifteen-degree angle (Figs. 2.25; 11.1: C). In the final phase the oarsmen stand erect, with the inboard arm pressed across the chest and the oar at a nine-degree angle (Fig. 11.1: D). Jarrett-Bell concludes that the oars were turned sideways on the return stroke and never left the water, resulting in a short, choppy stroke.5

One advantage of this kind of stroke is that it gives additional room inboard, which is an important consideration if the cargo was carried on deck.6 B. Landström, however, points out that Egyptian models complete with oarsmen show the oars lifted high from the water, suggesting that rowing was done in the normal manner: he therefore considers these postures to be the result of artistic convention.7

Figure 11.1. The four positions of oarsmen in the Deir el Bahri reliefs (after Jarrett-Bell 1930:12 fig. 1)

Rowlocks were used in Egypt by the end of the Old Kingdom.8 The oars on Hatshepsut’s Punt ships, however, were worked against grommets (Fig. 2.24). These are also seen on ships taking part in a cultic procession at Deir el Bahri.9

Sails

During the entire Bronze Age the sail used by the Mediterranean cultures, with some variations, was one that was stretched between a yard and a boom. The yard in its lowered position (and the boom at all times) were held in place by lifts connected to the mast cap. The lifts were one of the most conspicuous elements of this rig and almost always appeared in iconographic depictions of ships carrying this type of rig. The boom was generally lashed to the mast in a fixed position. The sail was furled by lowering the yard to the boom. This sort of rig is reproduced in the greatest detail on Hatshepsut’s Punt ships (Figs. 2.11, 15–18).

The concept of a sail used to move a vessel may have originated on the Nile in Predynastic times when people noticed, perhaps for the first time, the propulsive power of wind on shields placed in Gerzean ships.10 R. Le Baron Bowen suggests that the boom was a carryover from those times, representing the shield’s lower frame. The earliest known representation of an actual sail dates to the Late Gerzean period (Fig. 11.2).11 Square sails still exist, or existed in the recent past, on primitive craft throughout the world.12

Kenamun’s depiction of Syro-Canaanite ships shows small lines hanging down from the boom, which may be toggles (Figs. 3.3–6). Toggles found on post-Bronze Age wrecks are thought to have been used as part of an antiluffing device permanently attached to the leeches of sails for the quick attachment and removal of lines.13 If these objects on the Kenamun ships are indeed toggles, then they must have had another purpose since they are connected to the boom: perhaps they were used to wrap the sail when it was in the furled position. Alternatively, they may represent tassels similar to those seen on Herihor’s royal galley (Fig. 11.7).

Figure 11.2. The earliest known depiction of a sail, painted on a Gerzean jar (after Frankfort 1924: pl. 13)

The sail could not be taken in on this type of rig: like the later lateen rig, in order to reduce sail it was necessary to remove the sail and replace it with a smaller one.14 This is illustrated in the Middle Kingdom tomb of Amenemhet at Beni Hassan, where two ships towing a funerary barge are virtually identical in every detail—with the notable exception of the sail (Fig. 11.3). The forward ship (A) has a square sail twice the height of the short, rectangular sail carried by the ship (B) that follows it.

On Hatshepsut’s Punt ships cables, tightened with staves, are wound around either side of the mast’s base where it intersects the hogging truss (Figs. 2.15–18, 33–34; 11.4). Because no staves to tighten the hogging trusses are shown on these ships, R. O. Faulkner suggests that the cables served to tighten the hogging truss.15 This conclusion is unlikely for the following reasons:

• Similar arrangements appear on Old Kingdom seagoing and river craft. The latter do not have hogging trusses (Figs. 2.5, 7, 10).16 These cables were used for lateral strengthening on Old Kingdom craft and were tightened by staves thrust through them and lashed down. There is a natural progression from these lateral cables to those appearing on various depictions of Late Bronze Age seagoing ships.

Figure 11.3. The sail could not be taken in on the boom-footed rig. In order to reduce sail, it was necessary to replace the entire sail with a smaller one. This is demonstrated in the tomb of Amenemhet at Beni Hassan, where two virtually identical ships towing a funerary barge carry sails of different sizes (Twelfth Dynasty) (after Newberry 1893: pl. 14)

Figure 11.4. Detail of massive cables wrapped around the masts of three of Hatshepsut’s Punt ships (after Naville 1898: pls. 72, 75)

• Fragments of a painted relief from the Eleventh Dynasty temple at Deir el Bahri bear ships’ parts on which cables are held in place with thick belaying pins and connected to the hull. This is accomplished by means of a U-shaped apparatus that is identical to ones used to hold down the lateral lashings on the ships of Unas (Figs. 2.5, 7; 11.5).17 Since the cables on the Eleventh Dynasty ships are not tensed by twisting, they may represent an experimental method of tightening the cable, perhaps something akin to a Spanish windlass. This experiment apparently was not successful, for the device does not appear again.

• If Faulkner’s theory was correct, as the truss was tightened it would have moved down the mast, taking on a characteristic V-shape with its center at the mast and its high ends at the two nearest crutches:  . The Egyptian artists would have shown this as the normal shape of the truss, but they invariably portrayed the hogging truss as a horizontal line from stem to stern:

. The Egyptian artists would have shown this as the normal shape of the truss, but they invariably portrayed the hogging truss as a horizontal line from stem to stern:  . Either the artists did not include the tightening staves in the relief (although they existed on the actual ships) or the hogging truss was being tightened in another way.

. Either the artists did not include the tightening staves in the relief (although they existed on the actual ships) or the hogging truss was being tightened in another way.

• Similar lashings appear on the mast of Kenamun’s Syro-Canaanite ships, which do not carry hogging trusses (Fig. 3.4).

What purpose, then, did these cables serve? Normally, a mast requires shrouds to support it laterally. Shrouds are not depicted at Deir el Bahri or on Kenamun’s ships.18 This is apparently neither accidental nor due to artistic conventions. Indeed, shrouds would have been extremely difficult to use with a boom-footed rig. Perhaps the massive cables supported the mast laterally, in place of shrouds.

Cypriot models give additional evidence for lateral cables. The Kazaphani model is perforated amidships by a circular maststep (Fig. 4.5: C: B); on either side of this is a molded hook-shaped object (Fig. 4.5: C: D–E). Model A50 from Maroni Zarukas has horizontal convex ledges with vertical piercing located amidships on either side of the hull’s interior (Fig. 4.7: B–C). These may have served the same function as the hooks in the Kazaphani model. These hooks and lateral-pierced projections perhaps represent some form of internal structure used to attach such lateral cables to the ship’s hull. The lateral cables were better suited to the bipod and tripod masts on which they originally evolved. But with the introduction of the pole mast, this solution continued in use. Although far from ideal, it may have been enough if the sail was used only when running before the wind.

The boom-footed sail was superseded by an innovative system from which the boom had disappeared. Lines, called “brails,” are attached at intervals to the foot of the sail and brought vertically up it through “brailing rings” or “brail fairleads” sewn to the sail. The lines are carried up over the yard and then brought astern in a bunch. This type of sail, which works on the same principle as Venetian blinds, is furled by pulling on the brails—resulting in a considerable saving of time, effort, and manpower.

This rig appears in the Mediterranean at the end of the Late Bronze Age. At Medinet Habu, the Egyptian (as well as the Sea Peoples’) ships are outfitted with brailed rigs (Figs. 2.35–42; 8.3–8, 10–12, 14). The Aegean evidence is particularly interesting. Ship depictions from the Late Helladic/Late Minoan IIIB (thirteenth century B.C.) on which it is possible to determine the type of rig used (based either on sail shape or the mast cap) invariably show boom-footed rigs, or a mast cap with multiple rings for supporting such a rig (Figs. 6.26, 7.19, 28: A, D). All decipherable known ship portrayals from the Late Helladic IIIC suggest the use of a brailed rig (Figs. 7.8: A, 17, 21, 25, 29).

Experimentation with brails, however, began at least a century before they became common in the Mediterranean. A transitional phase between the two varieties of rig is preserved in several Egyptian depictions. In the tomb of Neferhotep (T. 50) at Thebes, which dates to the reign of Horemheb (ca. 1323–1295 B.C.), one ship has a yard and a boom. Its sail, however, is furled to the yard in the manner typical of the brailed rig (Fig. 11.6).

Figure 11.5. Part of ships’ rigging (lateral strengthening cables [?]) depicted on relief fragments from the Eleventh Dynasty temple at Deir el Bahri (from Naville and Hall 1913: pl. 13: 7; courtesy of the Committee of the Egypt Exploration Society)

Similarly, in a scene from the temple of Khonsu at Karnak, the royal galley of Herihor, which is taking part in the Opet ceremony, has a rig sporting a yard and boom. The sail is shown in the act of being furled to the yard by members of the crew (Fig. 11.7). The yard has been lowered to half-mast. Ten crewmen stand on the boom or climb on the lifts as they furl the sail in a manner reminiscent of that used on square-riggers during the Age of Sail. In the center, two men work lifts that continue vertically up the mast behind the yard (Fig. 11.7: A–B). These are probably the same lifts that held the tips of the yard in tension and which had to be released as the yard was lowered with the halyards.

Figure 11.6. This funerary barque bears a yard and boom, but the sail has been raised to the yard in a manner normal for the boomless brailed rig (tomb of Neferhotep [ T. 50] at Thebes; Horemheb) (after Vandier 1969: 946 fig. 355)

Other men haul on lines that cross over the yard (Fig. 11.7: C–D). These may be brails, or perhaps hand-holds meant for the crew as they furled the sail. Another crew member, who holds a rope in his right hand, seems to be securing the furled sail (Fig. 11.7: E). Herihor’s scene dates to ca. 1076–1074 B.C., long after the brailed rig was commonly used.19 It is thus an example of a traditional ship element continuing in cultic use long after it disappeared from working ships.

This evidence for a state of experimentation with sails in Egypt does not necessarily mean that the brailed rig was invented there. Indeed, it seems that the Egyptians followed, instead of led, in this development. L. Casson notes that the brailed rig does not seem to have developed in Egypt, nor does it appear to have originated in the Aegean.20 It seems that both Egypt and the Aegean adopted this rig from outside their borders. But from where?

R. D. Barnett suggests that the Sea Peoples may have been influenced in their shipbuilding by the Syro-Canaanites.21 It is likely that the brailed rig also originated on the Syro-Canaanite littoral. This possibility gains support from two considerations. On both the Egyptian and Sea Peoples’ galleys at Medinet Habu (along with the brailed rig), there are two additional elements that may hint at its source. First, the yards curve down at their tips; and second, the masts are surmounted by crow’s nests. Although both of these factors are foreign to Egypt and the Aegean, they are characteristic of earlier Syro-Canaanite craft from the Late Bronze Age with which these peoples had maritime interconnections.

Yards depicted with down-curving tips are exceptionally rare on Egyptian vessels portrayed in Egyptian art. They do, however, appear on several river boats from the fifteenth-century Theban tombs of Rechmire (T. 100), Menna (T. 69), Amenemhet (T. 82), and Sennefer (T. 96B).22 These, however, are the exceptions and not the rule. Furthermore, these representations may be artists’ variations on a single drawing taken from a common source, or copybook, used in the preparation of Theban tomb decorations.23 If so, their number is misleading.

Figure 11.7. The sail of Herihor’s royal galley is being furled to the yard, even though the ship carries the typical Bronze Age rig, complete with boom and multiple lifts (detail from SKHC: pl. 20 [Scenes of King Herihor in the Court: The Temple of Khonsu I: Plates 1–110, the University of Chicago, Oriental Institute Publications, 1979. © The University of Chicago. All rights reserved])

This rarity of illustrations of yards with downward-curving tips in portrayals of indigenous Egyptian ships—the country with by far the most comprehensive record of ship development in the Bronze Age—argues against them being in common use there. Downcurving yards, however, do appear on representations of Syro-Canaanite ships from the tomb of Nebamun, on the thirteenth-century scaraboid from Ugarit, and on the schematic graffito of a ship from Tell Abu Hawam (Figs. 3.7–9, 12–13).

Kamose (the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty), during his struggle to expel the Hyksos, was forced to place his lookouts on the cabins of his ships because they were not equipped with crow’s nests. No other Egyptian ships before the rule of Ramses III are depicted with one.24 A crow’s nest is carried by a Syro-Canaanite ship in the tomb of Kenamun, and in other ships of that scene lookouts appear, although the crow’s nests are hidden in the rigging (Figs. 3.3–6). The mast of the Syro-Canaanite ship painted in the tomb of Nebamun is surmounted by a rectangle that may also represent a crow’s nest; alternately, it can be interpreted as a mast cap (Fig. 3.8–9).25

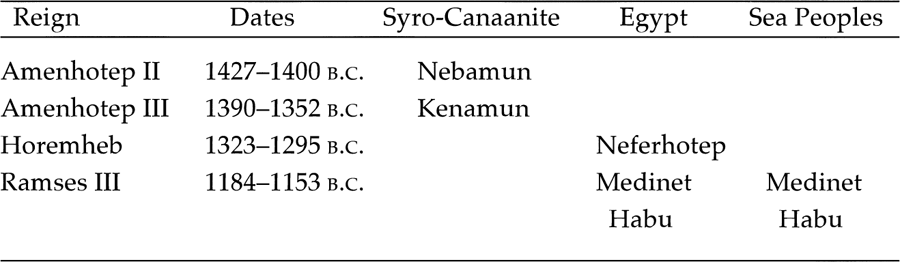

But if the brailed rig originated in the Syro-Canaanite littoral, why do we not have any evidence for it? The fact that there are no known representations of Syro-Canaanite ships postdating Amenhotep III may explain why this type of yard appears first in depictions of Egyptian ships. As described above, there are only two detailed depictions of Syro-Canaanite vessels in the Late Bronze Age. The later of these, in the tomb of Kenamun, dates to the reign of Amenhotep III, from a quarter- to a half-century before the painting in the tomb of Neferhotep:

Another consideration is that the ships depicted in the tomb of Nebamun and Kenamun may have been based on an illustration from a copybook that considerably predated the reign of Amenhotep III, and perhaps even that of Amenhotep II.

Sails were made primarily of linen, perhaps sewn together in patches (Figs. 6.21, 7.22).26 Linen is made from flax, particularly from the parts of the plant that transport water.27 This results in a fiber that is strong when wet and stands up well in damp conditions.28 No remnants of sails have been found on the many shipwrecks excavated in the Mediterranean to date. This may result from the small percentage of waxes and lignin contained in processed linen.29 A sail with a wooden brail fairlead still attached, which has been carbon dated to circa 150 B.C. ± 50, is the oldest known sail to date. Its final use in antiquity had been to wrap a mummy.30

In Classical times, brail fairleads were usually made of lead or wood and often had a protrusion with one or two piercings to allow them to be sewn to the sail.31 Three bronze rings, each with an additional external loop attached to its outer surface, were found at Enkomi and identified as pieces of horse accoutrement. They may, however, represent an early form of brail fairlead (Fig. 11.8).32 Two of the rings were found in the Trésor de bronzes and date to the twelfth century B.C.; the third comes from an unknown context.

Like modern-day spinnakers, the square sail was designed primarily for traveling before the wind. When winds were contrary, crews either bided their time at anchor or took to their oars. The ability of a ship to sail to windward is influenced by numerous factors: the type of rigging used, the hull design, and the ability of the hull to prevent drift to leeward, to name just a few. Scholars speculate as to how far into the wind (if at all) a ship could sail with a square rig. Ballard and C. V. Sølver theorize that the sail was not capable of using a wind much more than four points off the stern.33 A wind any farther abeam, in their opinion, would cause the craft to move too far to leeward. Le Baron Bowen and Casson consider the square sail capable of sailing as close as seven points into the wind.34 That means against a northerly wind, a ship headed north could do no better than west by north on one leg and east by north on the other.

The best data on sailing capabilities come from the Kyrenia II replica. Using a brailed sail, without a boom, the ship was capable of sailing fifty to sixty degrees (that is, four to five points) off the direction of the wind.35 A boom would have severely hampered her ability to sail to windward, however.

Figure 11.8. Bronze rings–perhaps brail fairleads–from Enkomi: A and C are from the Trésor de bronzes and may date to the latter half of the twelfth century B.C.; the context of B is unknown (after Catling 1964: fig. 23: 5–6 and pl. 48: h)

There is little information on the speed at which the different types of ships in the Late Bronze Age might have sailed. As in all periods, this depended on the sort of ship and sail used.36 Two Amarna texts may contain evidence of ships’ speed. Rib-Addi, the beleaguered king of Byblos, repeatedly requests that archers arrive at Byblos within the space of two months.37 He considered this a reasonable time for his message to reach Egypt and for the archers to be organized, dispatched, and transported to Byblos, perhaps by ship.

Knots and Rope

Rope and knots were an integral part of seafaring throughout the ages. Yet today, little research has been done on the types and uses of knots in antiquity.38 Perhaps the earliest known ones are the simple overhand knots in cordage dating to the seventh millennium from the Prepottery Neolithic B deposit in the Naḥal Ḥemar Cave in the Judean Desert.39

The most detailed portrayals of seagoing craft, such as Hatshepsut’s Punt ships, show loops where the lifts are tied to the yards. This suggests that the knots were tied for a quick release (Figs. 2.30, 31, 33–34).40 Rope was made from a variety of fibers in antiquity:41 date palm,42 Doum (Dum) palm,43 esparto grass,44 flax,45 grass or reed (?),46 halfa grass,47 hemp,48 and papyrus.49

Middle and New Kingdom models of Nile ships with their rigging preserved demonstrate a number of recognizable knots, primarily hitches and lashings.50 The use of a specific knot on a ship model does not necessarily mean that it was used on actual ships; however, the knots on models do indicate, at the very least, that such knots were known.

* * *

The boom-footed square sail had a profound effect on the seafaring capabilities and sea routes used in the Bronze Age. For example, the oft-stated ties between the Minoan (and now the Cycladic) culture and Libya assume direct two-way traffic between the Aegean and Africa. This is an illusion, for ships could not normally sail across the Mediterranean directly from south to north against the predominantly northwest wind. Unable to sail effectively into the wind, the circuit of the Mediterranean was necessarily counterclockwise.

The unwieldiness of the boom-footed rig precluded the use of shrouds. In their place in the Late Bronze Age—at least on the seagoing ships of Egypt, the Syro-Canaanite littoral, and Cyprus—a lateral cable system stabilized the lower part of the mast. How successful this system was in countering lateral forces on ships’ masts requires additional study.

It is not clear how these cables were fastened inside the hull. Were there internal constructions for this purpose as suggested by the Cypriot evidence? This lack of shrouds, coupled with the apparent preference for having the keel rise upward into the interior of the hull instead of protrude below the hull (where it would have served to prevent leeward drift), suggest that in the Bronze Age, seafarers were not overly concerned with winds from far off the stern. It also appears that the boom-footed rig was used only, or at least primarily, with following winds.51