Figure 7.1. Linear B tablet PY An 724, recto (photo from the Archives of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archaeological Excavations)

Mycenaean/Achaean Ships

Beginning in the sixteenth century B.C., the energetic Mycenaean culture made its appearance on mainland Greece. Mycenaean pottery, found throughout the eastern Mediterranean, is a valuable tool for comparative dating. At the same time, this vast spread of what is, archaeologically, a highly visible commodity has significantly confused our understanding of the Mycenaean role in Late Bronze Age trade. This is particularly true of the thirteenth century, when Late Helladic IIIB pottery flooded the East. On the other hand, more attention must be given to the role of Mycenaean and Achaean ships and seafarers in coastal raiding, mercenary activities, and colonization.

The Textual Evidence

Linear B

The Mycenaeans used a form of archaic Greek that they recorded in a script termed Linear B.1 Clay tablets written in Linear B are known primarily from large caches at Knossos, Pylos, and, to a far lesser degree, from Mycenae and Thebes. The repertoire of Linear B documents consists mainly of inventories and receipts kept by the palace bureaucracies. Linear B signs were also painted on jars. Although much about the world of the Linear B documents remains enigmatic, concentrated scholarly research in the decades since its decipherment has gleaned many insights into Mycenaean palace administration. But the documents are frustratingly telegraphic in nature.

Unlike other cultures in which clay tablets served as a principal form of documentation, most Linear B tablets were not intended for long-term recording; consequently, they were not kiln-baked. The tablets owe their survival to the same fires that hardened them while destroying the palaces in which they were stored. Thus, most Linear B documents appear to date to the last year, and possibly very near the time of destruction, of their find sites. Archival records meant for more permanent storage may have been recorded on materials that were more expensive, such as papyrus or animal skins, but unfortunately less durable than baked clay.2

There are many obstacles involved in defining the chronological and geographical distribution of the documents.3 Differences may have existed among the various Mycenaean centers: practices in one palace may not be assumed to apply to the entire Mycenaean world concerning subjects on which documentation is limited, as in the case of seafaring. Indeed, as we shall see, the reasons for preparing these documents may have varied from one site to the next. The Linear B script apparently went out of use with the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces at the end of the Late Helladic IIIB or the very beginning of the IIIC.

THE PYLOS ROWER TABLETS.

Three texts of the Pylos An series refer to “rowers” (e-re-ta).4 In An 610 e-re-ta appears in the damaged heading, indicating that the document deals with oarsmen allocated from various communities or supplied by officials. The text records 569 or possibly 578 men, but four entries are missing; J. Chadwick suggests that originally about 600 men were enumerated.5 These would have been sufficient to man a fleet of some twenty triaconters or twelve penteconters.

The text is badly damaged, but its pattern is understandable. The men are identified by locations. In two cases, groups of forty and twenty men respectively are brought by two notables: E-ke-ra2-wo and We-da-ne-u. E-ke-ra2-wo clearly held a high rank within the kingdom and may have been the ruler of Pylos, while We-da-ne-u elsewhere appears as the owner of slaves and sheep and may also have owned lands on which flax was cultivated.6 The rowers, for the most part, are classified as “settlers” (ki-ti-ta), “new settlers” (me-ta-ki-ti-ta), “immigrants” (po-si-ke-te-re), or by an unidentified term (po-ku-ta).7

The text contains fifteen lines of writing. After writing lines .1–.7 the scribe, apparently miscalculating the space needed to record all of his entries, began combining pairs of them on each line.8 This limited the space available on each line, and therefore he omitted the term ki-ti-ta for the first entry on each subsequent line. The remaining lines contain only a place name together with a number and a man ideogram. On line .14 the scribe wrote three entries, causing a lack of space that resulted in the dropping of the man ideogram after ko-ni-jo 126. It is clear, however, that this entry also refers to men. Chadwick notes that in cases where the term ki-ti-ta is missing, the scribe would clearly have assumed that anyone reading the tablet would have understood that each main entry referred to ki-ti-ta; he would therefore have only felt it necessary to record men falling into other categories, such as me-ta-ki-ti-ta or po-si-ke-te-re.

Five of the entries refer to place names of coastal settlements, three of which also appear in An 1, discussed below. The remaining names also seem to be place names with nautical connections. Thus, the men are apparently being supplied by the kingdom’s coastal towns. One group of rowers bears an ethnic term that may be restored as Zakynthos, the large island west of the Peloponnese.

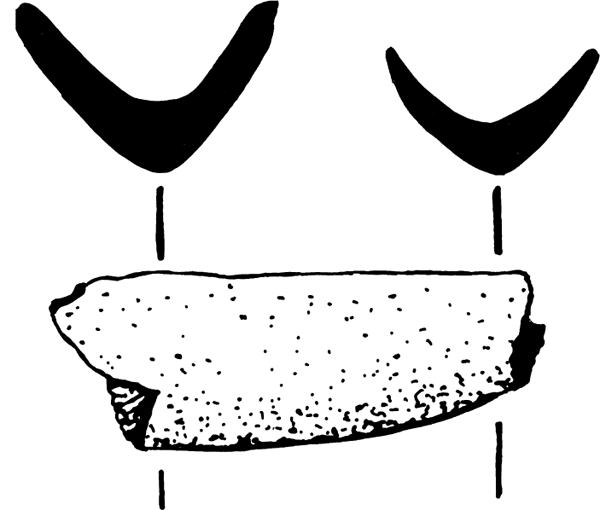

Figure 7.1. Linear B tablet PY An 724, recto (photo from the Archives of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archaeological Excavations)

Whereas An 610 deals with rowers that are available for service, An 724, on the other hand, focuses on rowers that are missing (Fig. 7.1). T. G. Palaima comments:

This tablet is difficult to interpret and none of the rival interpretations is thoroughly convincing. The surface of the tablet is damaged in places. There are several erasures at line ends which seem to be connected with indecision on the part of the scribe (Hand one = the normally reliable “master scribe” at Pylos) in regard to formatting and the actual information he was recording on the tablet. The meanings of several key lexical items are not apparent, and the syntax of the text is confusing or ambiguous. However, it shares vocabulary and place names with PY An 1, and most of its general purpose can be understood. The scribe has written clearly identifiable place names in the first position of lines .1 (ro-o-wa), .9 (a-ke-re-wa), and .14 (ri-jo). Notice that the first and last of these occur in the same order on consecutive lines of PY An 1. These place names divide the tablet into sections. Line .1 informs the reader that “rowers are absent” at the site of ro-o-wa and line .4 specifies that one of these men is a “settler” who is “obligated to row.” The subsequent lines continue providing evidence about missing rowers: lines .5–.6 record five men “obligated to row” and somehow associated with the important person E-ke-ra2-wo; line .7 lists one man connected with the ra-wa-ke-ta or “military leader”; another man is described in line .8. The section pertaining to a-ke-re-wa lists individual men, at least one of whom is associated with the e-qe-ta or “followers,” who seem- to be high-level administrative officials. Line .14 might have listed the largest single group of missing rowers, ten or more, at the site of ri-jo.

On the reverse the scribe has drawn what appears to be a schematic image of a ship, comparable to a recently discovered ideogram on a tablet from Knossos.9

Figure 7.2. Linear B tablet PY An 724, verso (photo from the Archives of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archaeological Excavations)

The ship incised on the back of An 724 is somewhat surprising (Figs. 7.2–3).10 Abundant iconographical evidence indicates what Mycenaean oared ships looked like. This is not one of them. The ship has a crescentic hull, identical to the many images of Minoan and Cycladic vessels discussed in the previous chapter. A semicircular construction is located amidships, and boughlike items extend from the ship’s right side (bow?). The central structure finds its closest parallel in the seven vessels depicted on a jug from Argos, while the boughs are reminiscent of bow devices on some Minoan cultic boats (Figs. 5.26; 6.52: A–C). The Argos ships are shown under oar or paddle.

Similarly, Linear B ideogram *259 has a crescentic profile (Fig. 7.4). The mast has a curving line on either side of it, perhaps representing a mast partner, central structure, or rigging. The joining of several document fragments has this ideogram following the word [ . . . ]-re-ta, perhaps to be reconstructed as e-re-ta, although this is not certain.11

Figure 7.3. Detail of the boat incised on the verso of Linear B tablet PY An 724 (photo by the author; courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archaeological Excavations)

The third and final document of the Pylos rower texts is fairly straightforward. An 1 is a list of thirty rowers raised from five settlements to man a ship bound for Pleuron (Fig. 7.5):

.1 rowers to Pleuron/going

.2 “from” ro-o-wa MEN 8

.3 “from” ri-jo MEN 5

.4 “from” po-ra MEN 4

.5 “from” te-ta-ra-ne MEN 6

.6 “from” a-po-ne-we MEN 7

Palaima notes concerning this text: “The italicized words are place names in the palatial territory of Pylos. There is some evidence that ro-o-wa may have been the major port of Pylos. None of these sites has been positively identified with actual locations in Messenia. [The term] ri-jo is associated with Rhion, an older name for the Classical site of Asine, the equivalent of modern Koroni. The total number of men is thirty, perhaps the size of the crew of a particular single Mycenaean ship.”

Figure 7.4. Linear B ideogram of a ship on a fragmentary tablet (KN U 7700 + X 8284 + FRIV–26 + FR VI–0 + FR VII–0) that may record rowers (after Bennett et al. 1989: 230 fig. 1)

J. T. Killen has shown that this document is based on a system of dues.12 Four sites (ro-o-wa, ri-jo, te-ta-ra-ne, and a-po-ne-we) mentioned in the same order in both An 610 and An 1 suggest a close connection between the two documents. The numbers of rowers taken from the settlements are proportional to those raised from the same towns in An 610 at an approximate ratio of 1:5. Thus, it appears that each settlement has contributed rowers based on a proportional evaluation of its tax requirements. If so, then An 610 may indicate the complete roster of rowers required by the palace from each of the individual settlements mentioned.

This manner of “call-up” is in keeping with the methods used in taxation of other commodities. Killen compares it to the mustering of crews in an Ugaritic text, KTU 4.40. He notes that it is not clear if An 1 represents a call-up of men for a specific event or if this is a general form of recruitment. Whatever the purpose of the trip, the call-up was based on an already existent levy system that functioned in peacetime as well.

There are several reasons for large groups of rowers to be drafted for service on a fleet. Not all have been given sufficient consideration in evaluating the happenings at Pylos reflected in the rower tablets (Fig. 7.6).13

Figure 7.5. Linear B tablet PY An 1 (photo from the Archives of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, courtesy of University of Cincinnati Archaeological Excavations)

In addition to the references to “rowers,” the term e-re-e-u, interpreted by Palaima as “official in charge of rowers,” appears in different forms on four other documents at Pylos.14 One of these, An 723, was written by Hand One and found very near An 724. Under this heading, the text lists two men, e-u-ka-ro and e-pa-re, who are associated with the sites of a-ri-qo and ra-wa-ra-ta respectively.

A FLEET AND OFFICERS AT KNOSSOS. The term po-ti-ro appears in the heading of a number of documents and several fragments of the V(5) series at Knossos.15 The texts consist of a title word in large characters, the word po-ti-ro followed by two personal names with the numeral one after each. Some of these personal names are common, appearing in other texts, but do not refer to the same persons.

Po-ti-ro, placed above the line, appears to define both names.16 Chadwick likens the term to the Greek word pontílos, a synonym for nautílos (the paper nautilus), while noting that the animal was so named because it was perceived to act like a sailboat. Thus, pontílos, like nautílos, can also mean “sailor.” Chadwick concludes that the Mycenaean equivalent of this word may have a similar meaning and identifies the pairs of po-ti-ro in the documents as the ships’ officers or navigators.17

The first word of the formula, which introduces each of the texts, is an adjective, apparently in the feminine form. Two of the six words preserved are place names recorded independently, and the rest can reasonably be reconstructed similarly as place names, three of which recall the names of coastal sites in the Aegean. Chadwick offers two alternative interpretations for these opening terms: they may represent either the ships’ names or the ports out of which the ships operated. He prefers the latter explanation because of the repetition of one name (da-*22-ti-ja) on two texts with different pairs of po-ti-ro.18

Figure 7.6. Luli, the king of Sidon, and his family escape from Tyre in a mixed fleet of oared, “round” merchant vessels and warships as Sennacherib advances on the city. All the ships are biremes and both types carry male and female passengers (from the palace of Sennacherib at Nineveh ca. 690 B.C.) (from Barnett 1969: pl. 1:1; courtesy Israel Exploration Society)

A comparison with recorded names of Classical Greek ships, however, suggests that this may actually support their interpretation as names of ships. Names of trieres appearing in the Athenian naval lists during the late fifth and the fourth centuries B.C. are almost invariably feminine in gender.19 Furthermore, about 10 percent of the ships in the lists are named after geographical sites, and many vessels bear the same name at the same time.

If Chadwick’s interpretation of the Knossos V(5) series is correct, it further supports the conclusion, already indicated by the Pylos rower tablets that, when necessary, Mycenaean palaces were capable of organizing fleets of galleys.

PERSONAL NAMES AND ETHNIC ADJECTIVES. Some information concerning Mycenaean seafaring may be gleaned from different types of personal names that appear in the Linear B documents. These names are often of ambiguous significance. A number of personal names at Knossos and Pylos derive from roots related to seafaring activities and are suggestive of an involvement in seafaring.20 These include “Fine-Harborer,” “Fine-Sailing,” “Fine-Ship,” “Ship-Famous,” “Ship-Starter,” “Shipman,” and “Swift-Ship.”

Place names from outside the Aegean occasionally appear as personal names. One shepherd at Knossos is named “the Egyptian.”21 Other individuals are defined as “from Cyprus.”22 Some personal names suggest movement by sea within the realm of the Mycenaean world: it is likely that such transport took place in Mycenaean hulls. A tablet from Knossos mentions men of Nauplia, presumably the site in the Argolid; their arrival at Crete would have required a sea voyage from mainland Greece.23 Similarly, a “Cretan” is mentioned at Pylos and a “Theban” at Knossos.

Groups of women in the Pylos Aa and Ab series are defined by ethnics derived from Aegean sites, primarily along the coast of Asia Minor: Knidos (ki-ni-di-ja), Miletos (mi-ra-ti-ja), Lemnos (ra-mi-ni-ja), Kythera (ku-te-ra3), as well as the possible identifications of Lycia (a-*64-ja), the Halikarnassos region (ze-pu2-ra3) and the more speculative identification of Khios (ki-si-wi-ja); others are known simply as “captives” (ra-wi-ja-ja).24 Chadwick suggests that the ethnics probably pertain to the sites of the slave markets from which the women and children had been acquired. Presumably the women and children had been abducted in piratical sea (?) raids, which did not yield, however, similar quantities of adult males. These probably would have been dispatched. This practice is described by Homer: “From Ilios the wind bore me and brought me to the Cicones, to Ismarus. There I sacked the city and slew the men; and from the city we took their wives and great store of treasure, and divided them among us, that so far as lay in me no man might go defrauded of an equal share.”25 As we shall see, this accords well with the picture derived from other textual materials, discussed below, which also show a particular interest in the taking of captives.

Ahhiyawa

Valuable information concerning seafaring can be gleaned from Hittite documents pertaining to the Ahhiyawa. These chancellery documents, found in the Hittite capital at Boǧhazköy, contain several names that bear a remarkable similarity to Greek names mentioned in the Homeric poems. These include the name Ah-hi-ya-wa(-a), identified with Achaeans, as well as forms of the names Miletos, Atreus, and Eteokles. E. Forrer, who was first to note the similarity, argues that these names can be best explained if the Hittites, during their westward expansion in Anatolia, had encountered Mycenaean Greeks, who were based in the region of Miletos. Since that time, scholarly debate over the identity of the Ahhiyawa has been voluminous.

Considerable advances have been made since Forrer first proposed the connection between Ahhiyawa and the Mycenaean culture. Main among these are two:

• The realization, indicated by the decipherment of Linear B, that the contemporaneous Mycenaean culture did indeed speak an archaic form of Greek.

• The discovery of a significant number of Mycenaean sites in and along the coast of Asia Minor, where the Hittites and the Mycenaeans were likely to have met.

The Ahhiyawa are now generally identified as a part of, or the entire, Mycenaean koine.26 The archaeological evidence of Mycenaean settlements in Asia Minor, particularly at Miletos and Iasos, fits comfortably into this interpretation of the written evidence.27 Dissenting views to this identification are raised by scholars who identify the Ahhiyawa with other Aegean ethnic groups, placing them in Anatolia or its outlying islands.28

While the Ahhiyawa problem itself is outside the scope of the present study, several of the documents concern ships and their uses and have particular relevance to this work.

THE INDICTMENT OF MADDUWATAS. This document, long thought to be one of the latest documents of the Hittite correspondence, has been redated to the reigns of Tudkhaliya II and Arnuwadas I (ca. 1450–1430 B.C.), making it the earliest known Hittite document with a reference to Ahhiyawa.29

Madduwatas is charged with joining forces with his erstwhile enemy, Attarissiyas (“the man of Ahhiya”), in carrying out raids against Alashia (Cyprus), which Arnuwadas considers his own domain.30 Madduwatas responds: “When Attarissiyas and the man of Piggaya made raids on Alasiya, I also made raids. Neither the father of Your Majesty nor Your Majesty, ever advised me (saying): ‘Alašiya is mine! Recognize it as such! Now if Your Majesty wants captives of Alasiya to be returned, I shall return them to him.’”31

ANNALS OF MURSILIS II. Mursilis II (1330–1300 B.C.) describes how, when he attacked Arzawa and entered its capital, Apasa (Ephesos?), Uhhazitis, the king of Arzawa and apparently an ally of the Ahhiyawa, escaped by sea to a location where he was later joined by his two sons.32 In Mursilis’s fourth year, the badly damaged text mentions a son of Uhhazitis, the sea, the king of Ahhiyawa, and the returning of someone by ship.

TAWAGALAWAS LETTER. This document is now attributed to the Hittite king Hattusilis (1255–1230 B.C.).33 In it, the king of Ahhiyawa is asked to hand over Piyamaradus, who has been raiding Hittite territory.

The king of Ahhiyawa responds by ordering Atpas, apparently his representative at Millawanda (Miletus?), to hand Piyamaradus over.34 When the Hittite king arrived there, however, Piyamaradus had escaped from Millawanda by ship, perhaps aided by Atpas himself, who was Piyamaradus’s son-in-law. Piyamaradus continues to attack Hittite territory and take hostages while using Ahhiyawan areas as staging grounds. In the letter, the Hittite king entreats his Ahhiyawan counterpart to give Piyamaradus to him.35

AMURRU VASSAL TREATY. A treaty between Shaushgamuwa, the last king of the land of Amurru, and Tudkhaliya IV (ca. 1265–1235 B.C.) begins with the title “And the kings, who are of the same rank as myself, the king of Egypt, the king of Babylonia, the king of Assyria . . .”36 Following this, the words the king of Ahhiyawa were written and then erased.

Since Assyria was hostile to the Hittites at the time, the king of Amurru is instructed to be unfriendly to Assyria. Merchants from Amurru are prohibited from trading with Assyria, and Assyrian traders are not to be allowed into Amurru. There then follow stipulations concerning preparations for war with Assyria, including the raising of an army and the preparation of a chariot corp. After this, on line 23, Tudkhaliya commands Shaushgamuwa that “no ship may sail to him from the land of Ahhiyawa.”

This line has generally been interpreted as a reference to Ahhiyawan merchant ships, which are being circumscribed from trading through Amurru with Assyria.37 For those scholars who equate the Ahhiyawa with the Achaeans or Mycenaeans, this is a powerful argument for the existence of Mycenaean merchant ships trading with the Syro-Canaanite coast.

Recently, G. Steiner has questioned the original translation of this line. He notes that the word translated by F. Somner as Ahhiyawa is partially missing and was restored by him on the basis of the erasure of the Ahhiyawan king in the document’s title. He further emphasizes that this line is separated from the other stipulations concerning proscription of trade with Assyria by the instructions for military preparations. For these reasons, Steiner proposes to interpret line 23 as referring to “warships” belonging to Amurru. I am not able to judge the linguistic validity of Steiner’s reconstruction.38 However, it is difficult to understand, in the context of the treaty, why the Hittite king would in some way prohibit the use of warships by his own ally, Amurru.

On the other hand, Steiner’s point concerning the positioning of this stipulation in the document in conjunction with military preparations is crucial, in my view, for understanding this document. If the text refers to Ahhiyawan ships, this would then make perfect sense. As we have seen in the previous documents, Ahhiyawan ships are consistently referred to as serving for coastal raids, the transport of captives taken in these raids, and, when necessary, for swift seaborne departures. In no other Hittite document concerning Ahhiyawa can trading intentions even be inferred in relation to ships. Given these considerations, I propose that Shaushgamuwa is being ordered to prevent Ahhiyawan (Mycenaean?) ship-based mercenaries from making common cause with Assyria through Amurru. Other textual evidence supports the existence of seaborne raiders from the Anatolian coast and points farther west who carried out mercenary activities and piratical raiding in the eastern Mediterranean as early as the fourteenth century B.C.

In one of the Amarna tablets, the king of Alashia seems to be answering accusations previously made by the Egyptian pharaoh to the effect that Alashians had taken part in attacks on Egyptian territory, made by people of the land of Lukka. Denying these charges, the Alashian king complained that he also suffered from similar raids: “Indeed, men of Lukki, year by year, seize villages in my own country.”39

This “seizing of villages” presumably refers to piratical attacks on Alashia for the express purpose of taking captives. The king of Alashia’s words echo the milieu of the Madduwatas text, with which, given its new dating to the late fourteenth century B.C., the Amarna document is now roughly contemporaneous. They also better confirm theories as to the origins of foreign women at Pylos.40

Rib-Addi, the beleaguered king of Byblos during the Amarna period, refers repeatedly to the enigmatic miši-people who appear to be linked with ship-based warfare.41 T. Säve-Söderbergh considers them early forerunners of the Sea Peoples.42 In one Amarna tablet, of particular interest regarding the Shaushgamuwa Treaty, the Egyptian king is asked to prohibit miši-ships from going to the land of Amurru.43

From the reign of Ramses II onwards, Egypt and other eastern lands commonly used Aegean mercenaries.44 However, an illustrated papyrus from Amarna in the British Museum may depict a scene of Mycenaean (?) mercenaries actively fighting alongside Egyptians.45 Thus, it is not impossible from a historical viewpoint that the miši-ships mentioned in the Amarna tablets may refer to Aegean (Mycenaean?) ship-based mercenaries in the employ of the Egyptian court at Amarna.

The Archaeological Evidence

During the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries, Mycenaean influence in the Aegean replaces that of the Minoans.46 What has been termed a seaborne “Mycenaean expansion” begins,47 and it is no less profound—perhaps even more so—than that of the Minoans’ influence during the previous period.48 Some sites suggest actual settlement by Mycenaean colonizers. The homogeneity of the Mycenaean pottery at this time indicates considerable seaborne intercourse between the Greek mainland, Mycenaean Crete, and the outlying Aegean islands.

Later, with the destruction of the Mycenaean world at the end of the thirteenth century, fleeing Mycenaeans (or Achaeans, as they are called)—or at least groups making and using Late Helladic IIIC pottery—created settlements even farther afield, in Cyprus and along the Canaanite coast.49 This waterborne emigration is one of the hallmarks of the Mycenaean culture. I consider this use of ships for the movement of populations a primary aspect of Mycenaean seafaring.

The Iconographic Evidence

A rich corpus of Mycenaean ship images exists consisting primarily of depictions painted on vases, incised in stone, or modeled in terracotta. Although of differing detail and accuracy, these depictions are almost invariably of oared ships, on the decks of which occasionally stride armed warriors.

The abundance of ship imagery bequeathed us by the Mycenaeans and their successors results, at least in part, from the interrelationship of ship iconography in the Mycenaean religion. In the Syro-Canaanite littoral and on Cyprus, indigenous ship depictions are rare, but anchors commonly appear in cultic contexts.50 Anchors do not appear to have had cultic significance for Aegean Bronze Age seafarers, who seem, however, to have had a predilection to portray ships in circumstances suggesting that they had a religious significance.

Geographically, Helladic ship representations are found in mainland Greece, the Aegean, and on Cyprus. As the Mycenaeans and the Sea Peoples used basically the same type of ship and overlapped to a wide degree both chronologically and geographically, it is not always clear whether the portrayals discussed here represent Mycenaean—or Sea Peoples’—ships.51

In every ship style or rig there were certain characteristics that left a lasting impression on the ancient observer and that were most commonly emphasized in depictions of that particular ship type. For example, during the entire Bronze Age when the boom-footed rig was in use, it was invariably the multiple lifts supporting the yard and boom that seem to have caught the eye and attention of the artists.

Mycenaean ships were no different in this regard. Many of the Helladic ship depictions share similar elements. One such element is the device shaped like a water bird, or of a bird head, that often topped the ships’ stems.52 However, undoubtedly the single most characteristic element of Mycenaean ship architecture—the one attribute that most impressed the persons who portrayed them and that appears on most Helladic ship depictions—is a structure directly above the sheer that looks rather like a ladder lying horizontally on its side:

Indeed, at times, an abbreviated image of a ship is expressed in its entirety by a horizontal ladder design alone, with oars and rigging added, as for example in the cases of a schematic graffito of a ship painted upside down inside a Mycenaean larnax, or a ship painted on a sherd from Phylakopi on Melos (Fig. 7.7, 23).53 Clearly, to understand the depictions of Mycenaean ships, our first imperative is to determine the ancient artists’ intentions in creating this horizontal ladder design.

To do this, we must begin with the most detailed and clearest depiction of a Late Helladic ship. This was discovered by F. Dakaronia at the site of Pyrgos Livonaton in central Greece, which has been identified as Homeric Kynos.54 Excavations at this Late Helladic IIIC site have revealed a wealth of ship iconography, including ships painted on sherds and fragments of terracotta ship models. Warriors, armed and armored, stand on their decks and in their forecastles. One galley, Kynos A, is depicted in particular detail (Fig. 7.8: A). The ship is nearly complete. The only parts missing are the device topping the stem, the lower part of the stern, the end of the sternpost together with the blades of the single quarter rudder, and the two sternmost oars.

The ship faces left and is divided longitudinally into three horizontal areas (Fig. 7.8: B: BC, XB, and AX). Area CB is the ship’s hull, from the keel/keel-plank to the sheer. Above this is a reserved area (XB) intersected by nineteen vertical “lunates,” which are curved on their right side (the side facing the ship’s stern) but whose left edges are attached to vertical lines. This detail is particularly distinguishable in the fifth lunate from the bow, where the lunate is somewhat separated from the vertical line. The ship is being propelled by nineteen oars on its port side. Each oar begins at the bottom of a lunate (Fig. 7.9). Presumably, the artist intended to depict a penteconter but ran out of room.

Figure 7.7. The element of the Mycenaean ship represented by the “horizontal ladder pattern” seems to have been so striking to the observer that, at times, sketches of Mycenaean ships consist of little else than this component, sometimes with oars and rigging added. One example of this is a ship painted upside-down inside a Late Minoan larnax (A). Below, in (B), the ship is reversed (after Gray 1974: G47, Abb. 11)

Figure 7.8. (A) Kynos ship A. Late Helladic IIIC (B) Constructional details (photo A courtesy of F. Dakoronia; drawing B by the author.)

The third area (AX) is decorated by two rows of semicircles, a common ornamental filler on Late Helladic IIIB and IIIC1 pottery.55 Since this motif also decorates the bodies of bulls and the leather-covered sides of chariots on Late Helladic pottery, it may indicate that the Kynos ship carries a leather screen enclosing an open bulwark.56 The fact that the mast can be seen through Area XA does not hinder this interpretation: this result would have been inevitable if the artist first drew the mast and only afterward added the superstructure.

Line X crosses the bow and continues beyond it, suggesting that this line represents a structurally significant element, perhaps a freestanding wale at the bottom of the screen (Fig. 7.8: B: X). Such reinforcement would be required to support the deck beams.

But where are the rowers? The oars begin at the lunates, so these clearly must be related to the rowers in some manner (Fig. 7.9). But how? Let us consider the following clues:

• The helmsman indicates how the artist perceived of the unarmored male body (Fig. 7.10).

• The oars are slanted toward the stern, suggesting that the rowers are at the end of their stroke. In that position the men are leaning backward on their benches with their oars drawn up near their bodies. In Late Geometric art, oarsmen depicted in this position are shown leaning backward on their benches with their left shoulder forward (Fig. 7.11).

Figure 7.9. Hypothetical reconstruction of Kynos ship A. Oars that lead to the nineteen lunates indicate that they represent the schematic torsos of oarsmen as seen through an open rowers’ gallery (Area XB in Figure 7.8). If Area AX is a screen at deck level, then the rowers’ heads would be hidden from the viewer behind the screen. Similar “disappearing rowers’ heads” are depicted on Greek warships from the late eighth century B.C. (see Figs. 7.12 and 14) (drawing by the author)

The above considerations lead to the conclusion that the lunates represent the upper torsos of the rowers, while their heads are hidden behind the screen. For this to be possible, deck planking must not have been placed along the ships’ sides.

The above interpretation is supported by several later parallels. A good illustration of this is seen on a fragment of a dieres, a two-banked Greek oared ship, painted on a Proto-Attic sherd from Phaleron (Fig. 7.12).57 In this image, the lower-level oarsmen appear in the open rowers’ gallery between pairs of wide stanchions while their heads are hidden behind the open bulwark above them.

Dated to about the same time (ca. 710–700 B.C.) but painted in Late Geometric style, two other sherds bear fragmentary images of dieres. In both cases the stanchions have been broadened into screens to protect the rowers. On one sherd, the artist has enlarged the height of the rowers’ gallery so that the entire torso and head of the rowers in the lower level are depicted, and the rowers are visible in the openings between the hatched screens (Fig. 7.13). In the second sherd, however, the men’s torsos are hidden; only their arms and shoulders are visible peeking out from behind the screens (Fig. 7.14). From the height of their shoulders, however, we may deduce that their heads are hidden behind the superstructure.

Figure 7.11. An oarsman at the end of his stroke (Attic Late Geometric I) (after Basch 1987:166 fig. 338)

Most writers who have discussed these three sherds from the late eighth century B.C. agree on their interpretation: they show two levels of rowers, one above the other, instead of a single level on either side of the ship. In the Proto-Attic ship the oars of the upper level are actually drawn across the side of the ship, while on the Late Geometric sherds the oars of the upper level reappear beneath the ships’ hulls, indicating that both depictions represent two levels on the near (port) side of each ship.

It is generally accepted that the ships of the Geometric period are developed from Mycenaean ships. Since this “horizontal ladder” element continues to appear prominently on Greek-oared ships of the Geometric period and later, it is reasonable to assume that it represents the same structural element in these later depictions.

Figure 7.12. Warship with two banks of oars on a Proto-Attic sherd from Phaleron (after Williams 1959:160 fig. 1)

Figure 7.13. Warship with two banks of oars depicted on a sherd from the Acropolis, Athens (ca. 710–700 B.C.) (after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 7: f)

From the above considerations we may conclude that the “horizontal ladder motif” on Mycenaean ship depictions, as on their Geometric descendants, represents an open rowers’ gallery intersected by vertical stanchions.58 Sometimes the stanchions have been omitted and, in one case, descussed below, the oars are attached at the height of the upper deck, indicating that these ships could be and were rowed from deck level, as were warships of the Late Geometric period. At Kynos, then, we have our first clear glimpse of the prototype ship that would eventually develop into the classical tradition of war galleys. As we shall see, ships of virtually identical appearance were also used by the Sea Peoples.59

Figure 7.14. Warship with two banks of oars depicted on a sherd from the Acropolis, Athens (ca. 710–700 B.C.) (after Morrison and Williams 1968: pl. 7: e)

Returning to the Kynos A ship, note that the figure at the bow stands on a raised deck in the forecastle. The warrior standing behind the mast suggests that the ship was at least partially decked longitudinally. The helmsman, manning a single quarter rudder, is positioned in the sterncastle. He wears no armor, although he does seem to be wearing a (feather?) helmet similar to those worn by the two previous warriors. He holds the loom of the quarter rudder with both hands. No tiller is depicted, but two joining semicircles, perhaps indicating a control mechanism, are drawn on the fore side of the loom.

The ship has a single pole mast situated somewhat forward of amidships. This is probably traceable more to the artist’s desire for sufficient room to display the warrior behind the mast than to any real structural meaning. All other Helladic ship portrayals show the sail planted squarely amidships. The sail and yard have been stowed. The circular masthead indicates that the rig represented is of the newly introduced brailed design.60 The only rigging shown is a single forestay and two slack lines that appear behind the mast, seemingly looped through one of the mast cap’s sheaves.

The sharp manner in which the stem meets the keel but lacks a horizontal projection is identical in shape to the bows of the Sea Peoples’ ship depicted repeatedly at Medinet Habu (Fig. 8.10). The keel is somewhat rockered and abuts an oblique stem. A model from Phylakopi shows how this type of fine bow may have appeared three-dimensionally (Fig. 7.42).

The castles are composed solely of groups of three inverted nestled angles, perhaps indicating that they were little more than an open framework, unenclosed by planking. The upper part of the stem bears numerous short lines extending from its inboard surface. These projections appear normally with bird-head stem devices, indicating that this stem was topped in the same manner (Figs. 7.15–17, 19, 28; 8.61: A–D).

Another depiction from Kynos consists solely of such a bird-head stem ornament, the torso of an armed warrior, and what may be the upper railing of the castle or open bulwark (Fig. 7.15). A row of projections runs along the upper end of the beak, over the head, and down the bird’s neck. The warrior carries a shield and throwing javelin. The stem’s extremities are missing, but its central, remaining, part is either vertical or very nearly so. Similar stems appear on other Helladic ship depictions as well as the Sea Peoples’ ships at Medinet Habu (Figs. 7.8: A, 16–19, 21, 29: A, 30: A).

Figure 7.16. Kynos ship C (Late Helladic IIIC) (NTS) (A after Dakoronia 1996; 171 fig. 9; B courtesy F. Dakoronia)

Figure 7.17. (A) Decoration on a pyxis found in a tomb at Tragana, Pylos (Late Helladic IIIC); (B) detail of ship (from Korrés 1989: 200)

Figure 7.18. (A) A reconstructed gold diadem found in Trench W–31 at Pylos bearing a ship with a bird-head stem ornament; (B) detail of the ship (after Blegen et al. 1973: fig. 108: d [reconstructed by Piet de Jong])

Figure 7.19. Ship depicted on the side of a larnax from Gazi (Late Minoan IIIB) (photo by the author)

A third ship drawing from Kynos portrays what appears to be the same ship type, sketched by a less-skilled hand (Fig. 7.16). It has a long, narrow hull and a stempost surmounted by a bird-head device with a strongly recurving beak. Twelve small projections protrude from the inner side of the bird’s head and beak.

The hull is also divided lengthwise into three sections as on the first ship, although the open bulwark, perhaps with its screen lowered, is no more than a line. At the bow a warrior stands on three vertical lines, representing a structure at the bow, although its surface is level with the deck.61 Here, as well as on other Bronze Age depictions, the stanchions have been omitted, perhaps to prevent confusion with the slanting oars. This is identical to the fashion in which warships are shown during the Late Geometric period: the stanchions are omitted when the ship is portrayed with the rowers working their oars from the lower level.62

To my knowledge, this illustration is unique to Mycenaean ship iconography in that it portrays oars continuing up to deck level, suggesting that the ship was being rowed from the upper deck. This development is significant because rowing these ships from the upper level was the first step toward creating a two-banked ship.63

Three warriors are arrayed on the forecastle and deck. The two on deck bear javelins and shields. The right arm of an archer standing on the forecastle is drawn back behind his head, a convention used in many cultures to depict the draw of a composite—but not a simple—bow (Fig. 8.1).64 The upper tip of the bow is visible beneath the beak of the bird-head stem device.65 More recently, a sherd bearing the stern portion of this ship depiction was found.66 On it, a helmsman works a single quarter rudder, and the ship is shown to have a recurving sternpost, similar to that of the Skyros ship (Fig. 7.21). The galley’s mast has been retracted.

A ship painted on a Late Helladic IIIC1 pyxis from Tholos Tomb 1 at Tragana near Pylos reveals striking similarities to the Kynos ships (Fig. 7.17: B).67 The vessel from Tragana has a continuous, thick line representing the hull from the sternpost to the short horizontal spur at the bow.68 Twenty-four vertical stanchions, placed at fixed intervals, connect the hull with a second narrow horizontal line. I take the latter to represent the line of the wale, beams, and central longitudinal deck, all of which are seen in profile. The stanchions form twenty-five rowers’ stations, suggesting that the artist depicted a penteconter.

The bow consists of two vertical lines joined by a zigzag line and rising above the spur. Behind it is a forecastle that serves as the base of an emblem that has been previously identified as a fish.69 The discovery of several additional sherds of the pyxis shows that this device is a water bird with a recurving beak.70 A line jutting out midway up the stem is reminiscent of the bow projection in the same position on Kynos ship A (Fig. 7.8: A). In the Tragana ship, however, this bow projection does not continue the line of the possible wale as on the first Kynos ship.71 Perhaps it represents a schematic duplication of a bird’s head and upcurving beak or a primitive form of subsidiary spur (proembolion).72

The sternpost rises from the keel in a graceful curve, terminating in an acorn-shaped device. The castles have open balustrades, similar to those on the first Kynos ship. The Tragana ship carries a single quarter rudder, the tiller of which seems to be held in place by a linchpin connected to the loom.73 The ability to remove the tiller from the loom would have been desirable when the mechanism was stored.

The mast cap has only two sheaves, indicating that the ship employed the newly introduced brailed sail. The sail billows out forward of the mast. A single forestay leads from the mast to the forecastle. Three lines, probably representing the backstay and the two halyards, lead from the top of the mast to the sterncastle. In this respect, the Tragana galley is similar to a depiction from Phylakopi (Fig. 7.25). A fourth line brought half astern, although seemingly attached to the mast, may indicate either bunched brails or a brace.

Two zigzag lines rise from the quarter rudder. A palm tree and three more zigzag lines—one vertical and two horizontal—are shown in the panel that separates the ship’s bow from its stern (Fig. 7.17: A).74

Another ship portrayal with a prominent bird-head stem device was found at nearby Pylos (Fig. 7.18).75 Embossed on a gold diadem, it finds its closest parallels in the Skyros ship and in the embossed bird-boat ornaments prevalent in Urnfield art (Figs. 7.21; 8.30).

The cutwater bow, or spur, seen on the Tragana ship appears earlier on a ship painted on a Late Minoan IIIB larnax excavated at Gazi, on Crete, and now exhibited in the Archaeological Museum at Iraklion (Fig. 7.19).76 Although this is the largest known depiction of an Aegean Late Bronze Age craft extant today, several of its details are enigmatic.

Figure 7.20. Two Late Geometric galleys depicted on sherds from Khaniale Tekke, near Knossos (after Boardman 1967: 73 fig. 6: 21)

The artist used three horizontal lines to compose the ship’s hull and superstructure. The lowest of these represents the ship’s hull up to the sheer. Twenty-seven vertical lines, one of which is the continuation of the mast, rise from it. The stanchions form twenty-eight rowers’ stations; presumably, the artist intended to draw a penteconter.

A median horizontal line bisects the reserved area lengthwise, as if we are seeing two banks of rowers’ stations, one above the other. There are several possible interpretations or this, none of which I find entirely satisfactory:

• The rowers’ galleries on both sides of the ship are depicted as if they were on one side, as in the Geometric ship on the British Museum bowl.77

• The lower area is the open rowers’ gallery, while the upper area is the open bulwark with the screen removed but the stanchions supporting it still in place. Unfortunately rowers, who might have elucidated the ship’s structure, are lacking.78

The Gazi artist seems to have had a liberal attitude with upright lines: an additional row of verticals connects the uppermost horizontal line with the lowest pair of diagonal lines, which run from the masthead to the ship’s extremities. L. Basch identifies it as a screen to protect the rowers at night, similar to those used on galleys from the seventeenth century A.D.79 There are, however, no known contemporaneous parallels for this interpretation.

Alternately, this element may represent decorations hanging from the rigging similar to those borne on one of the Theran ships (Fig. 6.27). Similar decorative devices hang from the stays on two galleys depicted on Late Geometric sherds from Khaniale Tekke, near Knossos (Fig. 7.20).80

The bow of the Gazi ship continues past the stempost in an upcurving spur. The stempost rises at an angle from the keel and is topped by a stylized zoomorphic head with a number of short vertical lines rising from it. The figurehead is longer than the horizontal bow projection, precluding its use as a functional waterline ram. Basch identifies the stem device as a horse’s head, a difficult interpretation because horse-head devices are otherwise unknown in Late Bronze Age Helladic ship iconography. Furthermore, the lines rising from the apparatus are paralleled on other bird-head devices (Fig. 8.61).81

Figure 7.21. Ship painted on a stirrup jar from Skyros (Late Helladic IIIC) (after Hencken 1968A: 537 fig. 486)

The sternpost curves up and blends into the right side of the “frame” that surrounds the ship. A single steering oar stretches out horizontally behind the craft. Two horizontal lines at the top of the mast apparently represent the yard and the boom with the sail furled between them, while three sets of diagonal lines lead from the mast to the stem- and sternposts. This is similar to the rigging on some ships depicted on Late Minoan seals (Fig. 6.21). On these ships a broad sail, hung between a yard and a boom, is placed high up on the mast with two or three diagonal lines descending from the mast to both of the ship’s extremities. Perhaps this is the Cretan equivalent of an “exploded view” of the rigging, with the lifts depicted beneath the boom.

Two vertical wavy lines rise from the quarter rudder, with two additional sets of three wavy lines located beneath the yard on either side of the sail. Beneath the ship are two birds (of prey?) with down-curving beaks, placed antithetically.82 Between them stand a schematic palm tree and a flower.83 Spirals fill the space in front of the ship. All of these elements had a numinous significance within the cultural milieu in which the scene was created. Taken together with the ship they form a statement, articulated in symbols and apparently addressing the theme of death and rebirth—a theme hardly surprising to find here, considering that the ship was painted on a larnax.84 The Tragana ship, which appears on a tomb offering, bears an identical set of wavy lines rising from the quarter rudder, and a palm tree is painted in the metope on the pyxis (Fig. 7.17).

A ship painted on a Late Helladic IIIC stirrup jar found on Skyros has a long, narrow hull in profile (Fig. 7.21).85 The stempost is elongated, raking forward and finishing in a bird-head device with a strongly recurving beak. This bow is closely paralleled by the posts of the Sea Peoples’ galleys at Medinet Habu (Figs. 8.23, 35). A narrow, reserved line horizontally bisects the craft and continues up the stempost. A single quarter rudder, somewhat malformed, appears below the stern.

Although the ship is depicted without a sail, its mast cap consists of only two sheaves, indicating that its prototype carried the newly introduced loose-footed brailed sail. Rigging represented is limited to a single forestay and backstay.

An oared ship painted on a Late Helladic IIIC stirrup jar from Asine is so schematic that scholars even disagree as to which side of the ship represents the bow and which the stern (Fig. 7.22). G. S. Kirk and R. T. Williams consider the long, thick projection to the left to be a ram, with the ship subsequently to be facing left.86 L. Casson, G. F. Bass, and Basch believe the ship to be facing right.87 The following considerations support the latter view:

• In some ship graffiti the quarter rudders are occasionally strung out directly behind the ship as on the Asine ship (Fig. 7.19).88

• If the thick vertical line in the center of the hull is the mast, as Williams logically concludes, then the sail is billowing toward the right.

• The horizontal projections on the inboard side of the ship’s stempost (if facing right) correspond to those painted on the stempost of a contemporaneous askos ship model from Cyprus (Fig. 7.48: A).

Figure 7.24. Hull of an oared ship depicted on a sherd from Phylakopi (Late Helladic IIIC) (after Marinatos 1933: pl. 13:16)

Figure 7.25. All that remains of one ship depiction from Phylakopi: its stem and stern devices and its rigging (Late Helladic IIIC) (after Marinatos 1933: pl. 13:16)

The ship has a cutwater bow. Eleven short vertical strokes that begin around the center of the hull and bisect the keel line probably represent oars. The sail is decorated with a net pattern, suggesting that the original was constructed from a number of small panels sewn together (compare Fig. 6.21).

A schematic—almost telegraphic—depiction of an oared galley comes from Phylakopi, on the island of Melos (Fig. 7.23).89 The ship’s bow and stern sections are missing. The hull and superstructure consist of two parallel lines joined by six narrower vertical lines. In this much-abbreviated form, the artist has captured the salient aspect of a Helladic galley: an open rowers’ gallery intersected by stanchions. Beneath the hull are seven oars, shown at the beginning of the stroke, and a single large quarter rudder, depicted in an unusual manner, with its blade angled toward the bow. The ship has stowed its sail and has two lines (presumably stays) running fore and aft from the mast.

Parts of two other ships, of Late Helladic IIIC date, are painted on several sherds from Phylakopi. Of one galley only part of the hull, with five oars and a quarter rudder, remains (Fig. 7.24). A vertical line above the hull may represent the ship’s mast. Here also the oars are angled toward the bow.

Figure 7.26. Parts of ships and their crews painted on Late Helladic IIIC sherds from the Seraglio, Cos. Note the (feather?) helmets worn by the figures (after Morricone 1975: 360 fig. 358, 359 fig. 356)

Of a third ship, only the posts, mast, and rigging remain (Fig. 7.25). The stem ends in a zoomorphic device, perhaps a bird head (Fig. 8.36).90 A palmette-shaped apparatus surmounts the sternpost. The rigging includes one forestay and three lines running from the tip of the mast to the sternpost. As on the Tragana ship, these are best identified as a single backstay and two halyards tied to cleats located in the stern.

Some of the Helladic ships discussed are portrayed under oar. Representations of oarsmen, however, are rare. A Late Helladic IIIC sherd from the Italian excavations at the Seraglio in Cos depicts two rowers and the oar, as well as the lower arms and left (?) leg of a third as they strain at their oars (Fig. 7.26: A).91 The rowers face left, suggesting that the galley faces right. The hull is drawn as a single broad horizontal band. The two bands beneath it, according to L. Morricone, encircle the jar and are therefore not related to the ship.

An angular structure, with a vertical line rising from it, is located to the left of the rowers. Perhaps these are the decorated sternpost and sterncastle. To the right of this vertical is a line in the form of a compound curve. The sterncastle, if it is indeed such, seems to be an open frame covered with hides. It bears similarities to castles appearing on the ship depictions from Tragana and Kynos as well as to the castles on the ships of the Sea Peoples from Medinet Habu.

Remnants of a second ship, together with the head of a figure, appear on another Late Helladic IIIC sherd from the same excavation (Fig. 7.26: B). The sail seems to be billowing toward the crewman, suggesting that the ship is facing left. A wavy line runs diagonally down from the masthead. The manner in which this cable is drawn finds an exact parallel in the hawser used to raise a stone anchor on a ship portrayed on a later Cypriot jug (Fig. 8.41: A). At left is a semicircular element with a reserved dot at its center: this may represent the top of a bird-head device, the reserved dot being its eye.

Figure 7.27. Ship portrayed on a sherd from Phaistos (Late Minoan IIIC) (after Laviosa 1972: 9 fig. 1b)

Figure 7.28. (A) Ship scene on a Mycenaean amphoroid krater from Enkomi, Tomb 3. Late Helladic IIIB (B–D) Additional sherds from the same krater (A from Sjöqvist 1940: fig. 20:3. B–D after Karageorghis 1960: pl. 10: 7)

On both of the Cos sherds, the figures are wearing helmets that have been interpreted as feather helmets like those worn by some of the Sea Peoples on the Medinet Habu reliefs. This raises the question of the ethnic identity of the men (and of the ships) depicted at Cos.92

A Late Minoan IIIC sherd from Phaistos bears a graffito of an oared ship (Fig. 7.27).93 The hull consists of a single thick horizontal line with a curving stempost and a raking sternpost; the vessel’s extremities are missing. The line of the hull continues past the junction with the stem, creating a horizontal spur. A quarter rudder, held by a helmsman facing aft, descends diagonally abaft the sternpost.

The ship is being rowed: six oars appear beneath the hull. Four lines lead off from the mast. The upper two appear to be a yard with downcurving ends, and the lower pair seem to be stays (compare Fig. 8.41: B). A small, pointed projection at the junction of the sternpost and hull is reminiscent of the miniature stern spur on two of the Sea Peoples’ ships (Figs. 8.11: E, 12: A).

Two ships appear on a Late Helladic IIIB krater from Enkomi (Fig. 7.28: A).94 Additional sherds belonging to this krater bear portions of the figure standing to the left of the scene and the top of a whorl-shell (Fig. 7.28: B–C), while the top of the mast and part of the figure standing to the right on the ship at right appear on another sherd (Fig. 7.28: D).95

The vessels are at least partially decked, and there is a structure in the bow, although its top does not protrude above deck level. The stem of the left ship is curved and fitted with a water-bird device; that of the ship at the right is missing, but presumably it ended in the same manner.

The curving sternposts are decorated with sets of volutes somewhat reminiscent of the stern device on a ship depiction from Phylakopi (Fig. 7.25). The masts rise amidships and are drawn as “bumpy” lines that may indicate decorations or wooldings. The masts are stepped in small triangles, perhaps representing mast-steps or tabernacles (compare Fig. 8.41: A–B). Although no rigging is depicted, the artist has supplied us with evidence to suggest that these ships from the thirteenth century B.C. continued to use the boom-footed rig for the mast cap. It consisted of pairs of sheaves, like those on the Theran ships, which served to hold the multiple lifts and the halyards (Fig. 6.13). The hulls, however, have apparently been altered considerably by the artist.

All four men “below” the deck stand in the same manner, facing each other in pairs. On the deck above them are two antithetical warriors wearing helmets and mantles. They carry swords in scabbards that end in wavy lines. In all these elements, down to the fringes on the scabbards, they are identical to the warriors on shore in the miniature frieze from Thera (Fig. 6.7). On either side of the ship on the left, a warrior dressed in the same manner faces the ship. The helmeted head and sword pommel are all that remain of the figure on the left. The men standing in, on, and next to the ships all face each other in heraldic patterns. Thus, the men below deck are positioned in that manner owing to artistic considerations and not because the action in which they are involved requires them to be arranged thus. The figures’ posture is conventionalized and therefore does not elucidate what they are doing.96

Figure 7.29. (A) Ship graffito on a stele from Enkomi (Late Cypriot III); (B) detail of the ship’s rigging; (C) detail of the rigging on Phoenician ships ca. 700 B.C. (A after Schaeffer 1952:102 fig. 38; C after Casson 1995A: fig. 78)

The ship at right, apart from its missing stem, is identical in all respects to the better-preserved vessel on the left. Its hull is slightly narrower, and the sternpost has an additional pair of volutes. The figure to the left of the ship is portrayed in the same manner as the men below deck but wears a helmet, implying that all these figures also had a military function. The preponderance of fighting personnel, lack of any cargo in the hull, and the similarity of certain elements of these ships (such as the bird insignia and stern decoration) to those appearing on other representations of Late Helladic IIIB–C galleys all suggest that these craft depict galleys with a more military than mercantile purpose and that they are taking part in a waterborne procession of the sort depicted at Thera.97

A schematic ship graffito of Late Cypriot III date is carved on a stele at Enkomi (Fig. 7.29: A).98 Assuming that the ship faces right, then the graffito makes perfect sense as a warship in the Helladic tradition. But is the ship facing right? The ship seems to be under sail—and the sail appears to be billowing to the left. If this is correct, then the ship itself must also face left, resulting in a rather odd-looking craft somewhat reminiscent of Aegean longships, a type of vessel never depicted with a mast and not otherwise recorded in the eastern Mediterranean since the end of the third millennium (Figs. 5.1–4).99

Figure 7.30. Ship graffiti incised on a rectangular pillar from a tomb at Hyria (end of Middle Helladic–Late Helladic periods) (from Blegen 1949: pl. 7: 6; courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens)

The graffito is damaged, resulting in several incomplete and missing lines to the right of the mast.100 Since this depiction dates to the twelfth century or later, it would have carried a brailed sail. With this in mind, I suggest that the ship is indeed facing right and that it carries a brailed rig with a furled sail. Thus, in Figure 7.29: B, line A represents the vessel’s mast; B, the yard; C, a single forestay; D, the halyard or brails; E, a backstay; and F, a brace. Triangles BHI and BGA are portions of the furled sail. The resultant rigging is identical to that appearing on ships of later date shown with their sails furled (Figs. 7.29: C; 8.41: B). Furthermore, the furled sails of the Egyptian and Sea Peoples’ ships at Medinet Habu show that the central portion of the sail was not as tightly furled as at the yardarms (Figs. 2.35–42; 8.3–4, 6–8, 10–12).

Figure 7.31. Ship graffiti incised on a rectangular pillar from a tomb at Hyria now at the Museum of Schiamatari (end of Middle Helladic–Late Helladic periods) (from Blegen 1949: pl. 7: 6; courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens)

The hull continues into a spur. A large forecastle nestles in the bow. Midway down the castle’s forward side and extending beyond it is a horizontal line, crossed by a second line and with two others rising vertically from it. This device is reminiscent of the bow projection located midway down the stempost on the Tragana ship (Fig. 7.17: B). Later parallels include the two bow projections on both of the Late Geometric ship depictions from Khaniale Tekke as well as a forked object projecting from the bow of a ship depicted on a sherd from the Heraion at Argos (Fig. 7.20).101

The graffito’s stern was first finished with a vertical post that was later altered into a curving sternpost by the addition of several lines. Both angular (Figs. 7.22, 27) and curving (Figs. 7.16–19, 21, 28: A) sternposts appear on Helladic ship representations. Several lines in the stern may indicate a castle. The mast is stepped in a massive triangular tabernacle.

Five rough graffiti of ships are incised on two parts of a broken rectangular pillar from a pillaged tomb near the village of Drámasi, a site identified with Homeric Hyria (Figs. 7.30–31).102 The tomb dates to the end of the Middle Helladic or the very beginning of the Late Helladic period. The hulls of all five ships are crossed by a series of vertical lines. Here the open rowers’ galleries have been enlarged by the “artist” at the expense of the ships’ hulls.103

Even the most detailed ship is crudely made (Fig. 7.30: A). The ship appears to be facing to the right. The hull from the keel to the sheer, as well as the open bulwark, are little more than two deeply engraved lines joined by a row of verticals. The hull is rectangular. Although the exact number is difficult to determine, it appears to have about twenty-two “windows” in what appears to be the open rowers’ gallery. Given the crudeness of the depiction, this may suggest that the prototype for this graffiti was a penteconter, as in the case of the Tragana—and probably the Gazi—representations.

The graffito’s hull has been narrowed to little more than a line. There is a vertical stem and a slightly angled but straight sternpost. A spur appears to jut out at the keel line, forward of the stem. The stem is topped by a horizontal zoomorphic (?) device carved deeply into the pillar. The ship has castles in its bow and stern, depicted as horizontal rectangles placed over the stanchions at either end but that do not rise above deck level (compare Figs. 7.16, 28). A line descending from the sternpost suggests a single quarter rudder, its blade angled toward the bow, like the quarter rudders on the Phylakopi ships (Figs. 7.23–24). The ship carries a mast and a sail, which billows toward the bow in a manner reminiscent of the Tragana ship (Fig. 7.17).

Three vertical lines are engraved above the deck. Basch identifies these as stanchions with lunate tops, used to support the rig when the sail is in its lowered position. Although such stanchions appear on the Minoan/Cycladic Theran ships, they are absent on other Mycenaean ship imagery. These schematic lines may represent humans, which are commonly included in portrayals of Helladic ships (Figs. 7.8: A, 15–16, 26–28).

Just below this ship is a second vessel that has a rockered keel, identified by Basch as a “round” merchant ship (Fig. 7.30: B). It should be remembered, however, that a profile view of a ship with such a keel, or a crescentic-shaped hull seen in profile, need not necessarily indicate a round ship.

The sternpost, at left, is curved. In this respect the graffito is almost identical to the Tragana ship (Fig. 7.17). The rockered keel rises at the bow in a steeper curve than at the stern, similar to the stem of the Skyros ship (Fig. 7.21). The open rowers’ gallery has been emphasized at the expense of the hull, which has shrunken to little more than a line. Castles nestle in the bow and stern.

Figure 7.32. (A) The southern wall of Temple 1 at Kition with ship graffiti engraved in it, looking east; (B) the wall, looking west (photos by the author)

Three other elongated horizontal objects appear on the other (upper?) half of the broken pillar (Fig. 7.31: A–C). These items are so schematic that even their identity as ships would be questionable were it not for the two previous ship graffiti that they somewhat resemble. Two graffiti have a “castle” at one end (Fig. 7.31: A, C). The middle graffito lacks its right (bow?) extremity (Fig. 7.31: B).

Figure 7.33. Map of ship graffiti on southern wall of Temple 1 at Kition (after Basch and Artzy 1985: 330 fig. 3)

Figure 7.34. Detail of the wall showing the section with ships M–Q (photo by the author)

Figure 7.35. Ship graffiti from the southern wall of Temple 1 at Kition: (A) ship no. 5; (B) ship no. 2; (C) ship no. 16 (after Basch and Artzy 1985: 331 figs. 4–6)

Ship graffiti were also found in Area II at Kition incised on a wall of Temple 1 and on the altar of Temple 4.104 Basch and M. Artzy suggest that the graffiti and anchors at Kition may indicate a mariners’ cult at the site and that the temple may have been dedicated to a deity who protected seafarers.105

Nineteen ship graffiti have been identified on the southern wall of Temple 1 (Figs. 7.32–34). The terminus post quern for the construction of the wall is ca. 1200 B.C.; the wall was visible, however, until the destruction of Kition. Since the site is inundated with Late Helladic IIIC pottery at this time, these depictions may represent Achaean ships.106 Of these graffiti, only four have been published in enlarged line drawing and one as a photo (Figs. 7.35–36).107 The graffiti are badly weathered, making multiple interpretations possible.

Basch and Artzy consider graffito “P” to be facing left with a large ram at the bow (Fig. 7.36). Such a massive ram is unparalleled in the period to which the graffito is dated. A triangular light shelter, according to this interpretation, nestles in the stern.

But perhaps the ship is facing right. The triangle at right then becomes a forecastle similar to that on the contemporaneous Enkomi graffito (Fig. 7.29: A). And the line at lower left may be interpreted as a quarter rudder, similar to those depicted on other Helladic ship representations (Figs. 7.16–17, 19, 21–22, 27).108

Basch and Artzy identify some of the Kition ships as belonging to the “round ship” type but do not explain the reasoning behind their conclusion.109 Emphasizing that it is premature to give the Kition graffiti an ethnic identity, they do propose linking the ships to the Acco graffiti that Artzy considers of Sea Peoples’ origin.

Figure 7.36. (A) Drawing of ship graffito “P” from the southern wall of Temple 1 at Kition; (B) Basch and Artzy’s alternate interpretation of ship graffito “P” (after Basch and Artzy 1985: 332 figs. 8B and 8C)

An altar in Temple 4 dating to the eleventh century bears two additional ship graffiti (Fig. 7.37). The right termination of one ship is interpreted by Basch and Artzy as a “fan” similar to those described on the Acco graffiti. This finial, however, bears more than a passing resemblance to an inward-facing bird head (Fig. 7.38: A). The second graffito bears a vertical termination at one extremity and a recurving post at the other (Fig. 7.38: B).

In my view, it is necessary to reserve conclusions concerning the existence of a fanlike device attributed to the Acco and Kition ships by Basch and Artzy until a more unambiguous illustration of this device is found.

Figure 7.38. Details of ship graffiti A and B on the altar of Temple 4 (photo A by the author; B after Basch and Artzy 1985: 329 fig. 2B)

Models, the majority of which apparently represents oared ships, are a valuable addition to our knowledge of Helladic naval architecture. They confirm and elucidate several of the structural details already noted on the linear depictions of these ships.

A terra-cotta model from a tomb at Tanagra, dating to the Late Helladic IIIB period, has a crescentic hull, reminiscent of Minoan and Cycladic ships (Fig. 7.39).110 Inside the hull, a central longitudinal painted line may represent a keel jutting into the hull, above the garboards.111 Fifteen lines painted across the model’s breadth symbolize frames or beams. The model’s most interesting detail, however, is painted on its exterior.

Here, the central area of the hull is taken up by a horizontal ladder design with twenty-six vertical lines. This might indicate an open bulwark were it not for the number of compartments. The twenty-seven stations fall between those of the ship depictions from Tragana (twenty-four verticals for twenty-five rowers’ stations) and Gazi (twenty-seven verticals for twenty-eight stations), suggesting that these numbers are not coincidental. All three images approximate the number of rowers’ stations of a penteconter. Thus, the artist has painted here the open rowers’ galleries with its vertical intersecting stanchions. This detail of the Tanagra model is paralleled on a Proto-Geometric terra-cotta ship model now in the Nicosia museum (Fig. 7.40).112 Later models of more developed ships occasionally illustrate this in plastic detail.113

Figure 7.39. Terra-cotta ship model from Tanagra in the Museum of Thebes (Late Helladic IIIB) (after Basch 1987:141 fig. 293:1)

A second model from a Tanagran tomb depicts the keel and three frames painted on the inside of the hull, while the hull’s exterior is shown with eight vertical stripes (Fig. 7.41).114 A bird-head device caps the stem.

The meaning of the external stripes is unclear. The lines clearly do not suggest the frames seen in “X-ray” view for, were this to be the case, the artist would have depicted the same number of verticals both on the interior and the exterior of the model. I consider the phenomenon of vertical lines painted on the exterior of Mycenaean terra-cotta ship models as possibly representing, in an abstract manner, either the stanchions of the rowers’ gallery or the oars (Figs. 7.42, 46).

A small Helladic model from Phylakopi suggests the manner in which the hull planking might have been brought in to meet the blade of the stem structure at the bow (Fig. 7.42). The nearly vertical stem protrudes well forward of the fine bow; the upper portion of the stempost is missing. On either side of it are painted oculi; these are the forerunners of the bow patches, mentioned by Homer, that appear on Geometric ships (Fig. 8.17: A).115 Bands perpendicular to the keel are prominent on the interior and exterior of the model just as on the second model from Tanagra.116 Details of a molded post and keel that protrude outward and beneath the hull appear on a fragment of a ship model from Mycenae made of terra-cotta (Fig. 7.43).117

Figure 7.40. Proto-Geometric model in the Cyprus Archaeological Museum, Nicosia (from Westerberg 1983: 91 fig. 19)

Figure 7.41. Terra-cotta ship model from Tanagra in the Museum of Thebes (Late Helladic IIIB) (after Basch 1987:141 fig. 293:2)

Another terra-cotta ship model, found at Oropos in Beotia and possibly of Late Helladic date, bears some similarities to the ships under discussion (Fig. 7.44).118 It has a vertical stem and recurving stern. A pronounced forecastle rakes forward over the spur at the junction of the keel and stem, precluding its use as a waterline ram. Holes at bow and quarters probably were used for hanging the model.

Figure 7.42. Terra-cotta ship model from Phylakopi (Late Helladic) (after Marinatos 1933: pl. 15:26)

Figure 7.43. Fragment of a terra-cotta boat model from Mycenae (Late Helladic IIIC) (drawing by V. Amato; courtesy of Paul F. Johnston)

Figure 7.44. Fragmentary terra-cotta ship model from Oropos, Attica (Late Helladic [?]) (after van Doorninck 1982B: 281 fig. 6: B)

A Late Helladic IIIB (developed) model found at Tiryns bears a striking resemblance to the ship depiction from Gazi (Figs. 7.45, 19). It has a rockered keel, a wide, V–shaped midships section, and a fine bow.

The keel line continues into an upcurving spur. The stem is capped with a forward-facing bird-head (?) device decorated with a row of bands.119 Beneath it is a horizontal line, perhaps representing a wale. The keel ends at the bow in an upcurving waterline spur. And, as on the Gazi ship, the stem ornament extends beyond the spur. Here also, the spur was clearly not intended as an offensive weapon.

The bow is decorated with two vertical zigzag lines on its port side and one horizontal zigzag line on its starboard side. The interior of the hull has two painted longitudinal stripes, perhaps indicating wales. Four lines, perpendicular to the keel, presumably are intended as frames or beams.

Other fragments of terra-cotta ship models of contemporaneous date from Tiryns have sections varying from V–shaped to rounded (Figs. 7.46–47). One has slanting lines painted on either side, perhaps depicting oars (compare Fig. 7.16).

Askoi made in Proto-White Painted or White Painted I fabric in the shape of Mycenaean galleys, both with and without a bow projection, have been found on Cyprus. This pottery, although of local Cypriot creation, is derived from Mycenaean prototypes.120 Askoi are a popular shape in Proto-White Painted Ware, although they usually portray birds or other zoomorphic shapes.121

Figure 7.45. Terra-cotta ship model from Tiryns (Late Helladic IIIB) (after Kilian 1988:140 fig. 37: 8)

Figure 7.46. Ship model fragment from Tiryns (Late Helladic IIIB) (after Kilian 1988:140 fig. 37: 5)

Figure 7.47. Ship model fragment from Tiryns (Late Helladic IIIB [?]) (after Kilian 1988:140 fig. 37:7)

One askos, of unknown provenance, depicts a warship with a keel ending in a spur or cutwater bow that bears several similarities to the Tragana ship (Fig. 7.48: A): a cutwater bow or spur, a vertical zigzag design on the bow that continues down to the spur, and an open rowers’ gallery with stanchions. Additionally, the unpainted aft side of the stem is crossed by six horizontal lines as on the Asine ship (Fig. 7.22). Similar lines appear on the aft side of the stem or on the upper surface of the head and beak of bird-head devices on the ships from Kynos and Gazi (Figs. 7.8: A, 16 B, 19; 8.61).122

Although these are familiar decorations on Proto-White Painted Ware, in this specific case they may be plausibly interpreted as representing actual ship elements. The manner in which the “horizontal ladder” decoration continues up the sternpost is paralleled on later Greek war galleys. The vertical zigzag line is identical to that on the Tragana ship (Fig. 7.17).

A second askos ship model of this series, from Lapithos, is similar to the first, but in place of the waterline spur it has a cutwater bow similar to those on the Kynos and Asine ships.123 The askos has a vertical lattice bow decoration, although all the other painted elements seem to be purely ornamental.

Figure 7.48. Askoi in the form of ship models from Cyprus dating to the Late Cypriot III period: (A) provenance unknown; (B) from Lapithos (published by permission of the director of antiquities and the Cyprus Museum)

Figure 7.49. Bow of a terra-cotta ship model from the Acropolis, Athens (Late Helladic IIIC) (courtesy of the Agora Excavations, American School of Classical Studies, Athens)

Figure 7.50. Terra-cotta ship model fragment from Asine (Late Helladic III) (after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 25: 332)

The stems of both of the previous models are missing. A third askos model from Lapithos indicates, however, that the stem finished with an inboard-curving bird-head device (Fig. 8: 47).124 As we shall see below, this reversal in the direction of the ubiquitous bird-head decoration is a key clue to understanding the relationship of Aegean oared galleys (from the end of the Late Bronze Age) and the ships of the Sea Peoples to Greek Geometric ships.

Although made of different material, the forefoot of a terra-cotta ship model found in a Mycenaean fill at the Athenian Acropolis is strikingly similar to the Cypriot askoi models (Fig. 7.49).125 The bow is decorated with straight (and now familiar) zigzag lines. A model fragment from Asine supplies details of internal hull construction (Fig. 7.50).126 The model is much reconstructed; only the bow section is original. The zoomorphic device capping the stem is comparable to those on the following two models.

Figure 7.51. Terra-cotta ship model from Cyprus now in the Israel National Maritime Museum, Haifa: provenance within Cyprus unknown (eleventh century [?] B.C.) (after Göttlicher 1978: Taf. 7:107)

Two models, said to have originated in Cyprus, have a crescentic hull with a zoomorphic head at the stem and an inward-curving sternpost.127 Although dated to the Late Cypriot I–III, they bear a remarkable resemblance to one of the later Phoenician models from Achziv.128 However, they also bear comparison to earlier ship graffiti from Kition (Fig. 7.33).

The first of these models is now exhibited in the Israel National Maritime Museum, Haifa (Fig. 7.51).129 Dated to the mid-eleventh century on the basis of the ware and decoration, its exact provenance in Cyprus is unknown. The model has a narrow, crescentic hull with a vertical stempost ending in a zoomorphic head. The second model is similar in shape but lacks the painted decoration (Fig. 7.52).