GROUP 5, “Yin-Yang Principles,” contains fifteen thematically linked chapters that generally (though not exclusively) describe Heaven’s Way in terms of yin-yang and four-seasons cosmology. The chapter titles vary in length from two to six characters, with three- and four-character titles predominating.

GROUP 5: YIN-YANG PRINCIPLES, CHAPTERS 43–57

43. 陽尊隱卑 Yang zun yin bei Yang Is Lofty, Yin Is Lowly

44. 王道通三 Wang dao tong san The Kingly Way Penetrates Three

45. 天容 Tian rong Heaven’s Prosperity

46. 天辨在人 Tian bian zai ren The Heavenly Distinctions Lie in Humans

47. 陰陽位 Yin yang wei The Positions of Yin and Yang

48. 陰陽終始 Yin yang zhong shi Yin and Yang End and Begin [the Year]

49. 隂陽義 Yin yang yi The Meaning of Yin and Yang

50. 陰陽出入上下 Yin yang chu ru shang xia Yin and Yang Emerge, Withdraw, Ascend, and Descend

51. 天道無二 Tian dao wu er Heaven’s Way Is Not Dualistic

52. 暖燠孰多 Nuan ao shu duo Heat or Cold, Which Predominates?

53. 基義 Ji yi Laying the Foundation of Righteousness

54. [Title and text are no longer extant]

55. 四時之副 Si shi zhi fu The Correlates of the Four Seasons

56. 人副天數 Ren fu tian shu Human Correlates of Heaven’s Regularities

57. 同類相動 Tong lei xiang dong Things of the Same Kind Activate One Another

Many of the chapter titles refer specifically to cosmology (incorporating expressions such as “yin-yang,” tian dao [the Way of Heaven], and tian shu [Heaven’s regularities]), and all are linked by common content. The chapters propose cosmic cycles and patterns to be emulated by the ruler, prescribing his emotions, actions, and policies in accordance with the yin-yang characteristics of the seasons throughout the year.

Most of these chapters

1 adhere to an unusual cosmic model in which the power of yang is much stronger and more active than that of yin, and yang is cosmologically dominant for much more than half the year.

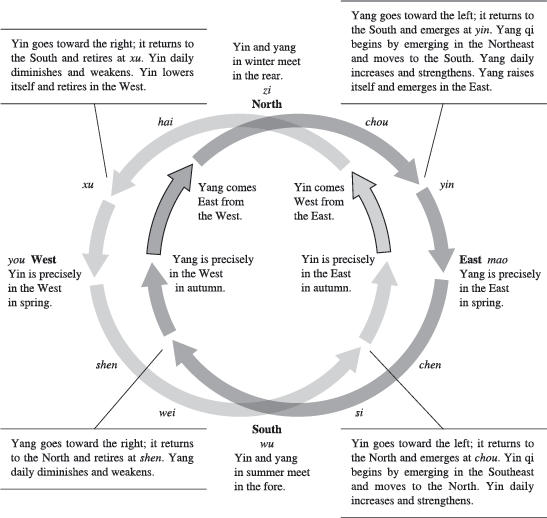

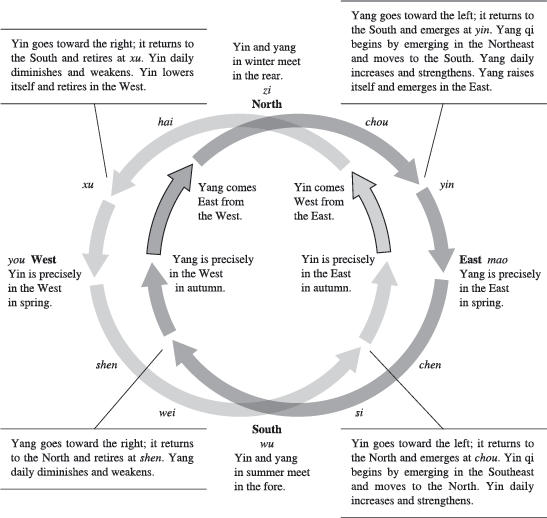

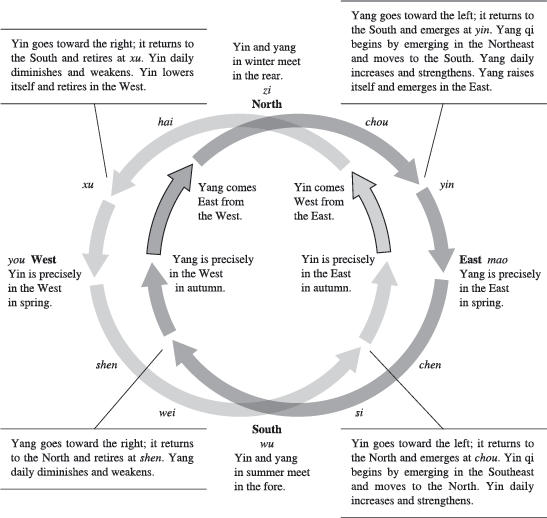

2 This cosmology is based on a decimal numerology derived from the ten Heavenly Stems, in which sets of ten, ten-day periods add up to artificial “seasons” of one hundred days each. Three such seasons allocate five-sixths of the year (five of six sexagenary day-cycles, for a total of three hundred days) to yang, and only one-sixth of the year (one sexagenary day-cycle) to yin. Yin and yang move around the horizon at an equal rate of speed and in opposite directions during the year, with yang moving clockwise and yin moving counterclockwise. Their positions at any given time are described by the directions correlated with the twelve Heavenly Branches. The two are together at the winter solstice (the first astronomical month, designated by the Earthly Branch

zi and correlated with the north), in which yin is the dominant force and yang is hidden. Yang then moves clockwise to emerge in the northeast while yin moves counterclockwise to go into hiding in the northwest. Yang is dominant from month 3 (branch

yin, east-northeast), and yin goes into hiding in month 11 (branch

xu, west-northwest). Yang dominates the east (Wood, spring), south (Fire, summer), and west (Metal, autumn); yin plays no role in those directions/seasons. Yin and yang reach their maximum separation at the spring and autumn equinoxes. When yang is in the east, yin is hidden in the west; when yang is in the west, yin is hidden in the east. The two forces converge at the summer solstice (south, Fire), but yin is wholly hidden at that time and yang reaches its maximum force; yin is inactive when the phase Fire is active, as shown in the figure.

Motions of yin and yang as understood in the Chunqiu fanlu. (Redrawn from Fung Yu-lan, A History of Chinese Philosophy, vol. 2, The Period of Classical Learning (From the Second Century B.C. to the Twentieth Century A.D.), trans. Derk Bodde [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1953], 28. Reproduced by permission of Princeton University Press)

Despite some differences in the particulars of their cosmic schemes, most of the chapters in this group are based on this distinctive and otherwise unknown model and elaborate on the implications of its novel features. The chapters uniformly privilege the yang aspects of Heaven’s Way over its yin counterparts. This strong preference for yang over yin is used in some chapters to justify and promote a general argument that in ruling the state, beneficence should predominate over punishment. These chapters seem to be aimed at mitigating such abuses of royal power as arbitrary cruelty and outright despotism. Other chapters use the yin-yang model to privilege the ruler as the wielder of yang power and therefore the embodiment of goodness, in contradistinction to his subordinates, who are identified with yin and evil. While linked by their yin-yang focus, these chapters were not necessarily written by the same person; their variability at the level of fine detail suggests multiple authors at work. At the same time, all these chapters share a yang-oriented ideological stance, indicating that even if they are products of several authors, they still are within the bounds of a single intellectual tradition and perhaps represent the views of a single master and his disciples.

The complex conception of the cycles of yin and yang envisioned in this group of chapters is strikingly different from the more usual scheme found in, for example,

chapter 3 of the

Huainanzi. There, yin and yang move around the horizon circle in tandem (on opposite sides of the circle but moving in the same direction) over the course of a year. Yang achieves accretion in the first half of the year, gaining in quantity and force from the winter solstice to the summer solstice, while at the same time yin undergoes recision, decreasing in quantity and force. In the second half of the year, it is the reverse: yang diminishes from the summer solstice to the winter solstice while yin increases. Yin and yang thus form a zero-sum pair, with the proportions of yin and yang shifting daily throughout the year but always adding up to a full complement of

qi. This is the scheme envisioned in the familiar

taiji 太極 diagram of yin and yang, showing two tadpole-like figures intertwined in a disk,

3 with yang and yin each dominating its half of the year. In contrast, in the scheme proposed in the

Chunqiu fanlu, the cosmic system is almost totally dominated by yang.

The two most striking characteristics of these chapters of the

Chunqiu fanlu are their unusual cosmological model and their strong preference for yang over yin. This cosmological stance is used to support a highly androcentric and patriarchal vision of society. To this extent, they all are at one extreme of yin-yang opinion. The opposite extreme is represented by the

Laozi, which exhibits a very strong preference for yin (and its embodiments, such as water and the valley spirit).

4 The middle ground is occupied by texts like the

Guanzi (which contains Warring States material but may have been compiled in the early Han period) and the

Huainanzi (139

B.C.E.), which tend to treat yin and yang in fairly neutral terms as complementary cosmic forces moving in tandem throughout the year. These texts show only a mild preference for yang (fructifying, growing, beneficent) over yin (ripening, harvesting, severe). It thus is interesting to see the

Chunqiu fanlu employing cosmological arguments in support of patriarchy, hierarchy, and androcentrism.

All the chapters in

group 5 incorporate the understanding, apparently ubiquitous and universally believed in early China, that yang governs the first half of the year—spring and summer—and that yin is at its height during the winter. But these chapters go beyond that common understanding to propose that yang also dominates autumn and, overall, plays by far the greater role in the annual cycle of seasons, with yin relegated to a small expanse of time and a wholly subordinate role.

5Many of these chapters comprise what must have been originally separate materials, as indicated by marked shifts in subject matter that cannot be explained by positing lacunae in continuous essays. Different editions of the text respond to these discontinuities with varying arrangements of the materials within individual chapters. As with earlier chapters, we follow D. C. Lau’s edition, with frequent reference to Su Yu’s editorial suggestions.

Description of Individual Chapters

Chapter 43, “Yang Is Lofty, Yin Is Lowly,” has three sections and takes its title from the first of them. Section 43.1 emphatically privileges yang over yin and proposes an elaborate numerological scheme to support that notion. The sages of antiquity are said to have modeled themselves on “the great number of Heaven,” which is identified here as the number ten. This chapter introduces the distinctive calendar in which ten periods of ten days each make up a sort of extended season (completely different from the natural seasons determined by the solstices and equinoxes, which have an average length of ninety-one and five-sixteenth days), with ten months (three one-hundred-day “seasons”) making up the yang portion of the year. The three hundred days of the yang portion of the year amount to five

ganzhi sexagenary cycles as determined by paired (yang) Heavenly Stems and (yin) Earthly Branches. But the scheme presented here is described entirely as ten, ten-day “weeks,” not sexagenary cycles. (The Earthly Branches play no role in this calendar except to designate the directions associated with the twelve months of the year.) In the annual calendar, yang is dominant for five-sixths of the year, and yin is relegated to a single sixty-day period (for cosmological purposes, the year is approximated as 360 days). Yin is discounted as a normal seasonal part of the year and treated almost as a taboo topic: “[Such] is the righteous principle of not being permitted to enumerate yin.”

6 Yin is associated here not only (as usual) with darkness, quiescence, femaleness, and so on but explicitly with inferiority and evil. Thus, the text asserts, “[W]e observe how to honor yang and denigrate yin.”

7

In accordance with its annual cycle of three one-hundred-day periods, section 43.1 describes yang as determining the activities of the cosmos’s other constituents as it makes its annual circuit of the horizon. As presented in this chapter, the movements of yin and yang do not specify, but also are not inconsistent with, the complex scheme just described and later elaborated in

chapter 48. This model’s separation of yin and yang provides the intellectual foundation for the emphasis found in this and the other chapters of the group on the movements and power of yang almost to the exclusion of the influence of yin.

The numerology of this chapter may be related to the stem-and-branch cycle as well as the “river chart” (

he tu 河圖), an esoteric diagram believed to have emerged magically from the Yellow River.

8 The river chart, too, is based on the numerology of ten and serves to integrate yin and yang with the Mutual Production Sequence of the Five Phases. Whether or not the river chart plays any conceptual role in the cosmology of section 43.1, the text does hint at some esoteric calendrical lore: “Hence, when counting the days, do so according to the mornings and not the evenings; when counting the years, do so according to the yang [i.e., odd] and not the yin [i.e., even] years.”

9 The denigration of yin is then traced to the

Spring and Autumn with some brief illustrations. The essay concludes with some of the most extreme androcentric claims of the entire text, insisting that yang dominates yin invariably and in all respects.

Section 43.2 straightforwardly correlates the seasons (and their attendant qualities of warming and cooling) with the emotions of happiness, anger, sorrow, and joy. Note, though, that these emotional states are different from those (love, hatred. happiness, and anger) in

chapters 44 and

45.

Section 43.3, a very short fragment, emphasizes that rulers should emulate Heaven in honoring yang and distancing themselves from yin. The chapter concludes with a clear lesson: “Punishment cannot be employed to perfect the age, just as yin cannot be employed to complete the year. Those who constitute government by employing punishment are said to defy Heaven. This is not the Way of the True King.”

10The first section of

chapter 44, “The Kingly Way Penetrates Three,” opens with perhaps the most often cited and best-known claim attributed to Dong Zhongshu, the famous triadic vision of rulership from which the chapter title is derived:

When the ancients invented writing, they drew three [horizontal] lines that they connected through the center [by a vertical stroke] and called this “king.” These three lines represent Heaven, Earth and humankind, and the line that connects them through the center unifies their Way. Who, if not a [true] king, could take the central position between Heaven, Earth, and humankind and act as the thread that joins and penetrates them?

11

The essay proceeds to explain how the king acts on Heaven’s behalf. As the “thread that joins and penetrates” all three realms, the king’s actions on Heaven’s behalf must emulate Heaven’s seasons, Heaven’s commands, Heaven’s numbers, Heaven’s Way, and Heaven’s will, all of which are notions developed further in other chapters in this group. Heaven is identified with the “perfection of humaneness,” and the four seasons are “Heaven’s instruments” for realizing Heaven’s intention to “nourish and complete” things. Just as Heaven (unless disrupted by external perturbations) sends forth warmth, coolness, heat, and cold in a timely fashion to ensure the transformations of the four seasons and a good harvest, so, by analogy, in order to realize righteousness and bring about a well-ordered age, the ruler must express his likes, dislikes, happiness, and anger in conformity with the four seasons.

Section 44.2 returns to the analogous categories of good harvests, which correspond to orderly ages, and bad harvests, which correspond to disorderly ages. The essay concludes by stating that only when the ruler’s four emotional states (likes, dislikes, happiness, and anger, as in 44.1) correspond to righteousness—as Heaven’s four climatic variables correspond to their respective seasons—can it be deemed that he “becomes a counterpart of Heaven.” This phrase (can tian 參天) explicitly recalls the query that begins this essay: “Who, if not a [true] king, could take the central position between Heaven, Earth, and Humankind and act as the thread that joins and penetrates them?” In this way, sections 44.1 and 44.2 are neatly tied together both conceptually and semantically.

Section 44.2 uses Five-Phase reasoning to extend the notion that “the superior is good and the inferior is bad” in the context of yin-yang cosmology. In our introduction to

group 6, “Five-Phase Principles,” we note that theorists who tried to coordinate the Five Phases with the four seasons basically had two choices, either to create an unnatural fifth “season” assigned to Earth or to regard Earth as applying in some general way to all four seasons but having no season of its own. Section 44.2 tries to find a middle ground:

Although [the phase] Earth dwells in the center, it also rules for seventy-two days of the year, helping Fire blend, harmonize, nourish, and grow. Nevertheless, it is not named as having done such things, and all the achievement is ascribed to Fire. Fire obtains it and thereby flourishes. [Earth’s] not daring to take a share of the merit from its father

12 is the ultimate in the perfection of filial piety. Thus both the conduct of the filial son and the righteousness of the loyal minister are modeled on Earth. Earth serves Heaven just as the subordinate serves the superior.

13

In this conception, Heaven and Earth and yang and yin endorse a patriarchal society and the transcendent value of filial piety: “Although Earth is the counterpart to Heaven, it does not mean that they are equal…. Things categorized as evil ultimately are yin, whereas things categorized as good ultimately are yang.”

14This section also reverts to the point made in 43.1 that the lord is never designated as evil and the minister is never called good, arguing that in the

Spring and Autumn, “in every case goodness is associated with the ruler and evil is associated with the minister.” (Note that this claim completely opposes the spirit of

group 1, “Exegetical Principles,” which discusses in depth several cases of worthy ministers and evil rulers in the

Spring and Autumn. The argument made in these yin-yang chapters also directly opposes the spirit of Dong Zhongshu’s memorials, in which he criticizes the emperor’s policies.) Section 44.2 ends with a series of short statements contrasting the attributes of yin and yang, always to the detriment of yin.

Chapter 45, “Heaven’s Prosperity,” one of the shortest chapters in the entire work, consists of two essay fragments, of 171 and 47 characters, respectively, both addressing themes discussed in

chapter 44. In fact, the language and topoi of the fragments are so close to those of

chapter 44 that they may originally have been part of that essay. Section 45.1 returns to the ruler’s four emotional states (love, hatred, happiness, and anger) to reiterate the argument of

chapter 44: “The sage observes Heaven and acts. This is why he carefully chooses the appropriate occasion for [displaying] love, hatred, happiness, and anger, wishing to harmonize with Heaven, which will not send forth warming, cooling, chilling, and heating if it is not the appropriate season.”

15 Section 45.2 defines the virtue of righteousness in terms of timeliness, another subject addressed in

chapter 44: “When the ruler is happy or angry, he must not fail to be timely. [Those feelings] are permissible in their time, and in their time they are righteous.”

16 We conclude, therefore, that the juxtaposition of these two essay fragments making up the current

chapter 45 is highly problematic. It is more likely, we believe, that whatever essay was titled “Heaven’s Prosperity” has long been lost and that what has been substituted for the lost chapter in transmitted editions of the

Chunqiu fanlu is text that has migrated from its original location as part of the content of

chapter 44.

Chapter 46, “The Heavenly Distinctions Lie in Humans,” marks a notable shift from the prose essays of the previous yin-yang chapters to a literary form seen predominantly in the first five chapters of the

Chunqiu fanlu: the question-and-answer format. In those earlier chapters, the anonymous questioner is sometimes identified with the formulaic expression “Someone raised an objection saying” (

nan zhe yue 難者曰), and the anonymous respondent is denoted by the simple verb “[someone] stated” (

yue 曰) or sometimes is merely implied.

17 In

chapter 46, the text consists of a single question and its answer. The unknown inquirer, “raising an objection,” asks: “In regard to the meeting of yin and yang, during the course of one year they have two encounters. They encounter each other in the southern quarter at the midpoint of summer, and they encounter each other in the northern quarter at the midpoint of winter. Winter is [dominated by] the

qi of mourning for [the destruction of] things. Why, then, do [yin and yang] meet there?”

18

The lengthy and detailed answer—which deals with both yin-yang cosmology and the Five-Phase correlates Wood/east/spring, Fire/south/summer, Metal/west/autumn, and Water/north/winter—takes up the rest of the chapter and includes features that appear to be unique to the

Chunqiu fanlu. That is, it envisions yin moving counterclockwise and yang moving clockwise over the course of the year, as described earlier. This theory is merely hinted at here but is developed in detail in later yin-yang chapters, which we will analyze beginning with

chapter 48. In common with many other Warring States and early Han cosmological texts, the chapter speaks of Lesser and Greater Yin (autumn and winter) and Lesser and Greater Yang (spring and summer).

19 For example, we find the statement “Thus, Lesser Yang in accordance with Wood arises and assists spring’s generating; Greater Yang in accordance with Fire arises and assists summer’s nourishing; Lesser Yin in accordance with Metal arises and assists autumn’s completing; Greater Yin in accordance with Water arises and assists winter’s storing away.”

20 In addition, the four emotional states to be correlated with Heaven’s seasons are identified as happiness, anger, joy, and sorrow. These are the same as the emotional states found in 43.2 but differ from the “love, hate, happiness, and anger” cited in

chapter 44. Finally, the chapter links the four emotional states with the cosmological characteristics of the four seasons in a way that is somewhat different from that in the earlier yin-yang chapters:

Likewise, without the

qi of happiness, how could Heaven warm and thereby engender and nourish in spring? Without the

qi of anger, how could Heaven cool and thereby proceed to kill

21 in autumn? Without the

qi of joy, how could Heaven disperse yang and thereby nourish and mature in summer? Without the

qi of sorrow, how could Heaven arouse yin and thereby seal up and store away in winter?

22

It is striking that the cosmological processes associated with the four seasons here are treated in a relatively neutral fashion, that “engendering and nourishing” and “nourishing and maturing” (and so on) are taken to be natural processes in the annual round of waxing and waning of yang qi. Nevertheless the chapter also affirms the yang-centric approach of the other yin-yang chapters: “[Y]in is yang’s assistant. Yang is the master of the year.”

Consisting of only 167 characters,

chapter 47, “The Positions of Yin and Yang,” is the shortest of the yin-yang chapters. In its current form, it appears to be fragmentary. But it is consistent with

chapter 46 and can be seen as an introduction to the complex description of the movements of yin and yang found in

chapter 48. In fact, it is not clear why

chapters 47 and

48 were divided, as the two can be read as a single continuous document.

Chapter 47 picks up on

chapter 46’s description of the annual round of yin and yang, adding the detail that yang is “above” (i.e., in Heaven) in its half of the year and “below” (presumably in the subterranean Yellow Springs) during the autumn and winter, whereas yin is sequestered “below” in the spring and summer, emerging only in the autumn and winter. The chapter emphasizes the contrasting qualities of yin and yang—chilling and heating, emergence and withdrawal, and so on—and concludes again with a statement strongly privileging yang over yin: “Heaven uses yang and does not use yin. It loves accretion and abhors recision.”

The title of

chapter 48, “Yin and Yang End and Begin [the Year],” is echoed in the first line of the essay: “Heaven’s Way ends and begins anew.”

23 This short essay contains a fairly full description of the

Chunqiu fanlu’s distinctive vision of the annual circuit of yin and yang, adumbrated in some of the earlier chapters of the yin-yang group. Yin and yang meet twice a year, at the winter and summer solstices, and they are separated farthest apart twice a year, at the spring and autumn equinoxes. The movements of yin and yang are described as reciprocal (“there is never a time when yin and yang do not divide up [the whole year] and [keep their respective portions] separate from each other”),

24 but yang is seen as dominating cosmic processes throughout the three seasons of spring, summer, and autumn. Even in autumn, when yin might be expected to dominate, “Lesser Yin flourishes but is not permitted to use autumn to accompany Metal.”

25 (In fact, in this scheme, the movements of yin and yang put yin at the eastern side of the horizon during autumn, so yin is quite literally not in a position to affect Metal.) If one assumes (and nothing in this chapter contradicts this) that these movements of yin and yang take place in the framework of the denary seasonal scheme of

chapter 43, then here yang would dominate the year not only during spring, summer, and autumn but in the beginning and ending weeks of winter as well, for three hundred days, or five sexagenary day-cycles. Yin would dominate only during a single sexagenary day-cycle centered on the winter solstice, when yang is hidden away or occluded and the force of the dominant yin is producing quiescence and torpor. The chapter’s concluding paragraphs, on the effects of yang in autumn, affirm that the scenario described conforms to the proper relationships, constant norms, and expediencies inherent in the Way of Heaven.

As do earlier chapters in this group,

chapters 49,

50, and

51 stress this dominance of yang. All three chapters begin by claiming that the defining characteristic of Heaven’s Way (stated somewhat differently in each chapter) is the singular manner in which it employs yin and yang. The opening line of

chapter 49, “The Meaning of Yin and Yang,” states: “The constancy of Heaven’s Way is for there to be one yin and one yang.”

26 But the two are not equal; the chapter reiterates that yang dominates three seasons of the year and yin, only one. Yang is privileged in what might be termed a metaphysical sense; yang is explicitly identified with life and yin, with death. Lesser and Greater Yin are correlated with the ruler’s emotional states, as in

chapters 43 and

44. Heaven’s Lesser Yin is correlated with humankind’s Lesser Yin and sternness, and Heaven’s Greater Yin is correlated with humankind’s Greater Yin and mournfulness.

Chapter 49 reiterates the familiar associations of emotional states (in the form in which they are given in

chapter 43) with the four seasons. The ruler once again is urged to unify his person with Heaven and employ things as Heaven does. Accordingly, he must ensure that he uses beneficence more generously than punishment, just as yang exceeds yin.

Chapter 50, “Yin and Yang Emerge, Withdraw, Ascend, and Descend,” similarly opens by stating: “In the grand design of Heaven’s Way, things that are mutually opposed are not permitted to emerge together. Such is the case with yin and yang.” Here, again, we see the

Chunqiu fanlu’s distinctive yin-yang scheme in action, the two “emerging” and “withdrawing” in different places and moving in opposite directions around the horizon circle. The remainder of the chapter supports this opening assertion cosmologically by tracing the movement, directionality, and location of yin and yang in each of the four seasons and at the solstices and equinoxes. The locations of yin and yang are specified in terms of “positions,” which denote the cosmological locations of the twelve calendar months around the horizon. The reciprocal movements of yin and yang around the horizon circle can be plotted as pairs of Earthly Branches, with meeting points at

zi (the winter solstice) and

wu (the summer solstice). In all these yin-yang chapters, this scheme gives the greater share of the year to yang, from the first month of spring through the last month of autumn. But the emphasis of this chapter is cosmological, describing the movements of yin and yang without reference to the moral and metaphysical characteristics emphasized in other chapters of the yin-yang group and without any notable preference for yang over yin. This, again, is the kind of small but significant difference that may indicate that this group of chapters derives from members of a coherent—but not uniform—intellectual lineage rather than a single author.

Like

chapters 49 and

50,

chapter 51, “Heaven’s Way Is Not Dualistic,” states: “In Heaven’s constant Way, things that are mutually opposed are not permitted to arise simultaneously. Therefore Heaven’s Way is said to be singular. What is singular and not dualistic is Heaven’s conduct. Yin and yang are mutually opposed.”

27 The chapter goes on to reiterate the now familiar circulation of yin and yang. Heaven’s Way is characterized as “not dualistic” (despite there being two cosmic forces, yin and yang) because the movements of yin and yang are always reciprocal and yang is privileged over yin. The point of the chapter seems to be that the ruler should emulate this singular quality of Heaven’s Way. The chapter spells out its advice to the ruler in detail, closing with a passage from the

Odes:

Therefore, to be constantly unitary and not destructive is Heaven’s Way…. [If you try to] draw a square with one hand while [trying to] draw a circle with the other hand, you will not be able to complete either of them…. This is why the noble man disdains two and honors one…. An

Ode declares: “The High God is close at hand; do not be double-minded.”

28 These are the words of one who understands Heaven’s Way.

29

The first section of

chapter 52, “Heat or Cold, Which Predominates?” also begins with a claim concerning Heaven’s Way. Here, however, the focus is on how Heaven sends forth yang and yin, warming and cooling to engender and complete the myriad things of the world. Both are necessary, but as in previous instances, this chapter argues that Heaven clearly privileges yang over yin and the respective warmth and coolness they generate to carry out the transformations of the year. The text asks the reader to consider Heaven’s activities from the first through the tenth month of the year, calculating the positions of yin and yang and asking whether warm or cold days are more numerous. One will discover that “[o]nly when the ninth month of autumn arrives does yin begin to be more abundant than yang.”

30 At this time, Heaven sends down cold and frost to bring living things to completion. Like

chapter 51, section 52.1 closes with a flourish from the

Odes to support its conclusion.

Section 52.2, whose subject departs markedly from that of section 52.1, takes up the topic of Yu’s flood and Tang’s drought, arguing that they were caused by human emotional energy and were not the products of the “constant regularities of Heaven” (and therefore were not baleful portents). When Yao died, this passage argues, the people’s mourning created so much yin energy that a flood ensued and Yu was called on to subdue it. Similarly, the tyrant Jie, last ruler of the Xia, created so much baleful yang energy that the reign of his virtuous conqueror Tang was marred at first by a great drought. This brief section tries to uphold the good reputations of Yu and Tang, and to do so, it must explain how such great sages encountered disasters when they ruled. It seeks to demonstrate beyond any doubt that the disasters associated with their reigns were not caused by their personal transgressions. Thus the section concludes: “Both [Yu and Tang] happened to encounter an untoward alteration [of seasonal

qi]. These disasters were not caused by the transgressions of Yu or Tang. Do not, if you happen to encounter an untoward alteration of

qi, have doubts about the constancies of everyday life. In this way, what you wish to preserve will not be lost, and the correct way will become increasingly manifest.”

31Chapter 53, “Laying the Foundation of Righteousness,” develops the notion that “all things invariably possess counterparts.”

32 Each pair of complements in the world—whether superior or subordinate, right or left, front or back, outside or inside, joy or anger, cold or heat, morning or evening—has its counterpart in the fundamental pairing of yin and yang. This holds true for the relations between ruler and minister, husband and wife, and father and son, all of whom also derive their righteousness from the Way of yin and yang. In keeping with the yang-centric bias of earlier chapters in the yin-yang group, section 53.1 maintains: “There are no places where the Way of yin circulates alone. At the beginning [of the yearly cycle], yin is not permitted to arise by itself. Likewise, at the end [of the yearly cycle], yin is not permitted to share in [the glories of] yang’s achievements. Such is the righteous principle of ‘joining.’”

33 Compare

chapter 48: “[T]here is never a time when yin and yang do not divide up [the whole year]”; that is, both are always present at all times. But as

chapter 47 stresses, “Heaven employs yang and does not employ yin.” Thus as section 53.1 concludes, the minister joins his achievements to the lord, son to father, wife to husband, yin to yang, and Earth to Heaven.

The four sections that make up the remainder of

chapter 53 appear to be fragments of essays that once were more complete. Section 53.2 continues the theme of paired opposites: some officials are promoted, some demoted, and so on. Section 53.3 returns to the theme of the annual reciprocal movements of yin and yang, in every case emphasizing the priority of yang. Section 53.4 is a fragment on the subject of seasonal warmth and coolness. Section 53.5 raises once again the notion of “Heaven’s numbers” and the fundamental role of the ten-day “week” in calculating the periodicities of yin and yang.

Chapter 54 is an empty vessel; both its title and its content have been lost. Presumably, it once consisted of yet another essay on the subject of yin and yang.

As we have seen, despite their differences in detail,

chapters 43 through

53 are based on the

Chunqiu fanlu’s distinctive cosmological model of the opposite and reciprocal movements of yin and yang around the horizon, and most, if not all, of these chapters seem to accept (or at least are compatible with) the denary division of the year into three one-hundred-day yang “seasons” (equivalent to five sexagenary day-cycles) plus one sixty-day yin “season” (equivalent to one sexagenary day-cycle).

Chapters 55 through

57, in contrast, maintain a basic focus on yin and yang but seem to depart, each in its own way, from the model proposed in the earlier chapters.

Chapter 55, “The Correlates of the Four Seasons,” returns to the theme of the four seasons, their activities, and their human correlates: “The sage correlates himself with Heaven’s conduct to create his policies…. [Thus] gifts, rewards, penalties, and punishments must be promulgated in accordance with the appropriate occasion, just as warmth, heat, coolness, and cold must issue forth in accordance with the appropriate season.” With these correlative claims established, the chapter concludes by asserting that this is precisely why the

Spring and Autumn criticized those instances in which gifts, rewards, penalties, and punishments were not implemented on the proper occasions. In marked contrast with

chapters 43 through

53, this chapter is entirely in the spirit of the “Yue ling” (Monthly Ordinances) calendar, various versions of which (

Lüshi chunqiu, Liji, Huainanzi) were in circulation during the Western Han. The seasonal attributes found in these—spring germination, summer growth, autumn harvest, and winter storage—match the content of

chapter 55. In addition, the annual movement of yin and yang—going in tandem from winter to summer and back again, yang waxing as yin wanes and vice versa—implied in the chapter matches the cosmological model found in the “Yue ling” calendar.

Chapter 56, “Human Correlates of Heaven’s Regularities,” details the noble qualities of humankind, derivative of its cosmic parents Heaven and Earth: “Of the living things born of the vital essence of Heaven and Earth, none is nobler than human beings. Human beings receive their destiny from Heaven, and therefore they surpass [the lesser creatures] that must fend for themselves.” That is, only human beings can match Heaven and Earth. This is demonstrated in the remainder of the chapter, which describes in detail the macrocosm/microcosm heavenly correlates of the human body, employing a kind of reasoning about the relationship between Heaven and the human body widely encountered in such late Warring States and Western Han texts as the

Lüshi chunqiu and

Huainanzi.

Chapter 57, “Things of the Same Kind Activate One Another,” develops further the theme that concludes

chapter 56, the mutual resonance among things in the universe that are categorically alike. It repeats the example, found in a number of early texts, of musical resonance. The essay marshals a wide array of examples, many based on yin and yang, to demonstrate this principle of resonance. It touches on the practice of rainmaking: “Those who understand this, when wishing to bring forth rain, will activate yin, causing yin to arise; when wishing to stop rain, will activate yang, causing yang to arise.” The questions of “seeking rain” and “stopping rain” are explored at length in

chapters 74 and

75 of

group 7, “Ritual Principles.” Dong Zhongshu himself achieved a considerable reputation for his ability to cause rain to fall or to stop falling during the time he served as administrator of Jiangdu.

This brief review of the chapters in

group 5 demonstrates that despite the fragmented and disarranged quality of some, these chapters do constitute a cohesive unit. We believe that whoever compiled the

Chunqiu fanlu brought these materials together in this order precisely because they deal with the great Han theme of cosmology, expressed primarily as the complementarity of yin and yang in the transformations of the four seasons. In a few chapters (especially 43, 46, and 48), the yin-yang focus is augmented by the use of Five-Phase categories, particularly the directions (east, south, west, and north) and the seasons (correspondingly, spring, summer, autumn, and winter). In general, the phase Earth is ignored in these correlations, with its identification with the center assumed but not emphasized. This degree of Five-Phase analysis is only to be expected, as the seasons and the directions are among the most basic of the correlates of the Five Phases. Indeed, it would have been difficult for any Western Han intellectual to discuss yin-yang and the annual cycle of the seasons without reference to those basic correlates. But the focus of these chapters is clearly on yin and yang.

As the two basic types of

qi employed by Heaven in managing the myriad processes of the phenomenal world, yin and yang make it possible to analyze the transformations of the four seasons. How this is accomplished is the second important organizing theme, addressed in

chapters 43 to

53. Furthermore, all the chapters in the group argue that in the workings of the natural world, Heaven always privileges yang over yin. This cosmological claim has important political implications, because the way in which Heaven employs yin and yang provides a model for how the human ruler is to employ beneficence and punishment. Just as Heaven gives priority to yang over yin, so must the ruler favor beneficence over punishment. The first of two different but complementary arguments proceeds from the perspective of quantity (

chapters 49 and

53)—that is, the portion of the year dominated by yang versus yin. The second line of reasoning argues from the perspective of location and direction (

chapters 43,

46,

47,

48,

50,

51, and

53), maintaining that the reciprocal movements of yin and yang (by which yin is hidden for most of the year) demonstrate Heaven’s preference for beneficence over punishment. The remaining chapters (44, 45, and 49) develop the notion of “adapting to the seasons,” describing how the general qualities of the four seasons—for example, the coolness of autumn or the heat of summer—prescribe the ruler’s activities.

Issues of Dating and Attribution

These chapters appear to be part of a conversation, or debate, over the nature of yin and yang and the exact mechanisms of their operation, a debate that originated in the mid-third century

B.C.E. with such texts as the

Lüshi chunqiu. It continued in the first century of the Western Han dynasty, especially during the reigns of Emperor Jing (r. 157–141

B.C.E.) and Emperor Wu (r. 141–87

B.C.E.), when such issues were a matter of widespread interest and dispute.

34 The position staked out in these chapters is yang centric and takes a strongly negative view of yin. It stands in stark opposition to the yin-biased

Laozi and takes issue with the moderate stance exemplified by such texts as the

Guanzi and

Huainanzi. The androcentric and patriarchal stance of the

Chunqiu fanlu’s yin-yang chapters is compatible with, and adds a cosmological dimension to, views inherent in the hierarchical and highly moral image of the ideal society envisioned in the works of Confucius and his earlier followers.

To reiterate,

chapters 43 through

53 in the

Chunqiu fanlu propose a novel and otherwise unknown understanding of the movements and periodicities of yin and yang. The very distinctive yin-yang theory presented in these chapters is strikingly different from the more usual view (found, for example, in

Huainanzi 3 and other

Huainanzi chapters) and did not become generally accepted during the Western Han or later. This argues for its being the view of a single individual or a small group of like-minded individuals whose lineage of transmission failed.

Was that individual Dong Zhongshu? Or was that group Dong Zhongshu and his disciples? There is good evidence that Dong’s own views of yin-yang cosmology were quite similar to some of those expressed in the Chunqiu fanlu’s yin-yang chapters. Consider, for example, this passage from one of Dong’s memorials, quoted in the Han shu:

The most important aspect of Heaven’s Way is yin and yang. Yang corresponds to beneficence; yin corresponds to punishment. Punishment presides over death; beneficence presides over life. Thus yang always takes up its position at the height of summer, taking engendering, nurturing, nourishing, and maturing as its tasks. Yin always takes up its position at the height of winter, accumulating in empty, vacuous, and useless places. From this perspective, we see that Heaven relies on beneficence and does not rely on punishment. Heaven causes yang to emerge, circulate, and operate above the ground to preside over the achievements of the year. Heaven causes yin to retire and prostrate itself below the ground, seasonally emerging to assist yang. If yang does not obtain yin’s assistance, it cannot complete the year on its own. Ultimately, however, it is yang that is noted for completing the year. Such is Heaven’s intent.

35

In addition, the Yantie lun (Debates on Salt and Iron Monopolies, 81 B.C.E.) testifies to Dong’s interest and expertise in understanding phenomena by means of yin-yang and four-seasons cosmology:

The origins [of anomalies] the administrator of Jiangdu Master Dong deduced from the mutual succession of yin and yang and the four seasons. The father begets it, the son nourishes it, the mother completes it, and the son stores it away. Therefore

spring [presides over] birth and corresponds to humaneness;

summer [presides over] growth and corresponds to beneficence;

autumn [presides over] maturation and corresponds to righteousness;

winter [presides over] concealment and corresponds to propriety.

This is the sequence of the four seasons and what the sage takes as his model. One cannot rely on punishments to complete moral transformation. Therefore, one extends moral education.

36

In the passage just quoted from the

Han shu, Dong’s statements to Emperor Wu show that by around 140

B.C.E., Dong was employing the authority of Heaven, manifested in the workings of its yin and yang

qi, to make very specific political arguments. He contended that how Heaven employs the two basic forms of cosmic

qi, yin and yang, provides a compelling model of rulership. Correlating punishment and beneficence with yin and yang, respectively, Dong urged the emperor to order his empire by means of moral authority rather than coercive punitive laws. Thus a comparison of the contents of

Chunqiu fanlu’s

chapters 43 through

53 with the known views of Dong Zhongshu on yin-yang and the four seasons makes it quite plausible that he was the author of some of those chapters. Some, but probably not all. For example, while he would have had no quarrel with the idea that ministers are yin to the ruler’s yang, we regard it as unlikely that Dong—who had a long and successful bureaucratic career—would have stated categorically (as in chapter 44.2) that “in every case, goodness is associated with the ruler, while evil is associated with the minister.” That statement, as we have pointed out, is quite at variance with the view of the relationship between ruler and minister found in the first five chapters of the

Chunqiu fanlu—chapters closely associated with Dong Zhongshu himself. Moreover, considered as a group, these yin-yang chapters display small but significant differences in wording and technical details. In our view, this makes it unlikely that all these chapters were written by the same person.

Our considered opinion is that these chapters as a whole may indeed represent the views of Dong Zhongshu and one or more of his disciples, albeit with some puzzling contradictions. Beyond that we cannot go. It is unlikely, pending the discovery of definitive evidence, that the authorship of these chapters can be assigned to anyone with complete confidence.

Compared with

chapters 43 through

53,

chapters 55 through

57 are much more conventional and do not seem to represent Dong Zhongshu’s distinctive views of yin and yang as we have identified them.

Chapter 55 takes a standard Wood/Fire/Metal/Water view of the seasons/directions/phases and the governmental policies associated with them (gifts/rewards/severity/punishments).

Chapter 56 deals in conventional macrocosm/microcosm principles like those found in many Western Han texts. Finally,

chapter 57 is framed in terms of standard resonance theory, including the very common example that if you pluck one tuned string, another similarly tuned string nearby will respond. The fact that this chapter also mentions rainmaking by activating yin and rain-halting by activating yang is only weak evidence for an association with Dong, despite his reputation as a rainmaker, because it comes in the context of much other routine resonance theory.

It is hard to see what specific associations with Dong Zhongshu our “anonymous compiler” would have seen in

chapters 55 through

57 to induce him to include them in the

Chunqiu fanlu. They are not incompatible with

chapters 43 through

55, but they represent more conventional yin-yang views with which Dong Zhongshu may have agreed but which are not particularly associated with him. Again, it is possible that these chapters represent the work of one or more of Dong’s disciples and were included in the text for that reason. We conclude that taken as a whole, the yin-yang chapters seem to be a fair representation of the cosmological views of Dong Zhongshu and his followers.