THE SEVEN chapters of

group 6, “Five-Phase Principles,” focus on Five-Phase cosmology and a concern with deriving political norms from the characteristics of that cosmology.

GROUP 6: FIVE-PHASE PRINCIPLES, CHAPTERS 58–64

58.

五行相生 Wuxing xiang sheng The Mutual Engendering of the Five Phases

159. 五行相勝 Wuxing xiang sheng The Mutual Conquest of the Five Phases

60. 五行順逆 Wuxing shun ni Complying with and Deviating from the Five Phases

61. 制水五行 Zhi shui wuxing Controlling Water by Means of the Five Phases

62. 制亂五行 Zhi luan wuxing Controlling Disorders by Means of the Five Phases

63. 五行變救 Wuxing bian jiu Aberrations of the Five Phases and Their Remedies

64. 五行五事 Wuxing wu shi The Five Phases and Five Affairs

Description of Individual Chapters

Chapters 58,

59, and

60 are closely related, as they share many of the same Five-Phase correlations and sensibilities and progress logically from one to the next. In addition, all the essays identify the “current dynasty” with the power of the Fire phase, an important point to which we will return. The first two chapters in the group, though not a perfectly matched pair (among other things, the “Mutual Engendering” chapter also includes material on the Mutual Conquest Sequence and is a much more polished production in literary terms), are essentially mirror opposites. The two chapters present a schematic of positive and negative ideals of governance based on the Five Phases.

Chapter 58, “The Mutual Engendering of the Five Phases,” adheres to the familiar scheme of describing the year in terms of the Mutual Production Sequence, supplying an artificial fifth season of “midsummer” to correlate with Earth. This conception of annual time also implicitly links the Five Phases with the waxing and waning of yin and yang:

Wood = spring = east = Lesser Yang

Fire = summer = south = Greater Yang

Earth = midsummer (sixth month) = center = Mature Yang, Emergent Yin

Metal = autumn = west = Lesser Yin

Water = winter = north = Greater Yin

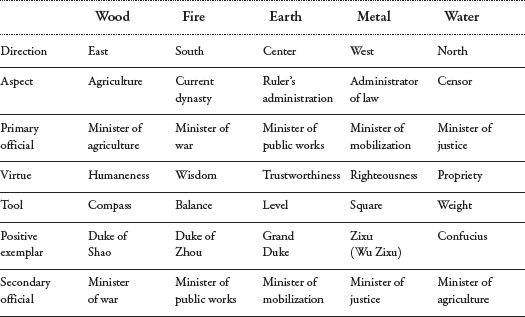

Chapter 58 correlates each of the Five Phases with the direction, aspect of governance, primary governmental official, virtue, tool, positive exemplar, and secondary official to whom the primary official passes on responsibility in an idealized bureaucracy, as summarized in

table 1. The types of activities associated with the “humaneness” of the minister of agriculture exemplify the ways in which these correlative schemes neatly prescribe the conduct of the bureaucracy’s highest-ranking officials:

The minister of agriculture esteems humaneness. He promotes scholars versed in the classical arts and leads them along the path of the Five Emperors and Three Kings. He follows their good points and rectifies their bad points. Grasping the compass, he promotes birth and, with the utmost warmth, saturates those below. He understands the fertility, barrenness, strengths, and weakness of the terrain; establishes affairs; and engenders norms in accordance with what is suitable to the land.

2

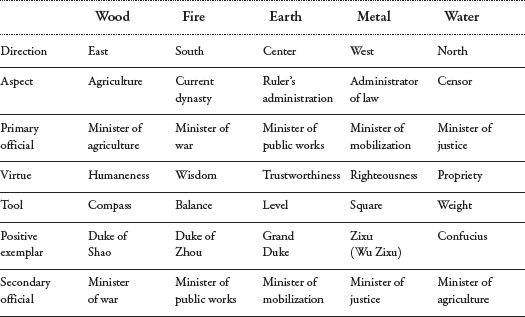

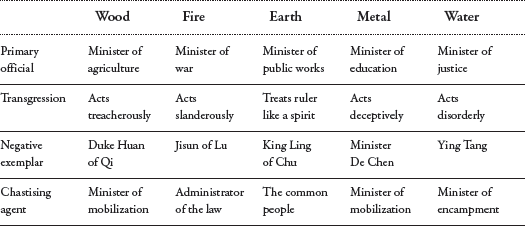

Chapter 59 (in our reordering of the first two chapters of this group), “The Mutual Conquest of the Five Phases,” also presents each phase in the standard Mutual Production Sequence but concludes the discussion of each phase with a statement of the relevant conquest: Wood (Metal conquers Wood), Fire (Water conquers Fire), Earth (Wood conquers Earth), Metal (Fire conquers Metal), and Water (Earth conquers Water). Each section identifies a particular phase with a primary governmental official, a transgression, a negative exemplar, and (with the exception of the Earth phase) a chastising agent (usually an official) responsible for meting out punishment, as shown in

table 2.

TABLE 2

The following passage from (the reordered)

chapter 59 describing the treachery of the minister of agriculture exemplifies how the radiating influence of the various high-ranking ministers is detailed in every section:

If the minister of agriculture acts treacherously, he will form factions and partisan cliques. [These in turn will] obstruct the ruler’s clarity, force worthy officials into retirement and hiding, extinguish the lineages of nobles and high officers, and teach the people to be wasteful and extravagant. There will be much coming and going of visitors and guests, and people will not exert themselves in agricultural affairs. They will amuse themselves with cockfights, dog racing, and horsemanship. Old and young will lack propriety; the great and small will oppress each other, and thieves and bandits will rise up. Growing arrogant and presumptuous, the people will defy proper principles.

3

These examples demonstrate how the two chapters function together to provide positive and negative exemplars of how the highest officials of state are to govern themselves, the ethical values they are to embody, and the particular actions that each should ideally follow or avoid if they are to realize those values as they carry out their official responsibilities.

The closely related

chapter 60, “Complying with and Deviating from the Five Phases,” as its descriptive title suggests, also outlines specific governmental policies commensurate with the Five Phases. In this chapter, it is the ruler, rather than high-ranking ministers of state, who is directed to follow such policies. The descriptions of Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water again follow a formulaic pattern. Each phase is correlated with a season and its characteristic activity, a set of policies to be implemented by the ruler, and the Heavenly favors that will result if the ruler pursues those policies. The chapter also explains the calamities that Heaven will send down in keeping with the relevant Five-Phase correlations (illnesses befalling the common people, misfortunes afflicting animals, and so on) should the ruler fail to follow the appropriate policies. This chapter follows a long-established tradition of prescribing activities for the months and seasons of the year. In effect, it is an abbreviated version of the familiar “Yue ling” (Monthly Ordinances) of the

Lüshi chunqiu and the

Liji (also found in the

Huainanzi under the title “Shi ze”

時則 [Seasonal Rules]), a text that seems to have been widely circulated in the late Warring States and early Han periods.

Chapters 61 and

62 form a pair as well, as the entire content of both chapters parallels two sections of

chapter 3, “Celestial Patterns,” in the

Huainanzi.

Chapter 61, “Controlling Water by Means of the Five Phases,” closely parallels

Huainanzi 3.22

4 and presumably is based on that text (or both

Huainanzi 3.22 and

CQFL 61 are derived from a common third source, now unknown). Despite its title, the chapter does not explicitly refer to the control of water, but the import of the title becomes clear if it is understood to mean “controlling the negative influence of yin by means of the Five Phases.” It begins by identifying the five seventy-two-day periods of the annual cycle, starting with the winter solstice, with the respective phase—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, or Water—to be employed in the conduct of governmental affairs and the particular characteristics associated with the

qi, or vital energy, of that phase. The remainder of the chapter lists specific policies to be followed by the ruler for each of these five seventy-two-day periods. The paired

chapters 61 and

62, together with

chapter 63, form a distinct subgroup within the Five-Phase group of chapters. All three are devoid of introductions and other literary embellishments and appear to be handbooks in near-tabular form for experts making calendrical predictions or interpreting omens. Many of the seasonal directives that

chapter 61 proposes differ from those outlined in

chapter 60.

5

Chapter 62, “Controlling Disorders by Means of the Five Phases,” consists of only 142 characters, with neither an introduction nor a conclusion. This brief text is nearly identical to

Huainanzi 3.23, with only one systematic difference: the

Huainanzi refers to the phases using the

ganzhi Heavenly Stem–Earthly Branch sexagenary system, whereas the

Chunqiu fanlu refers directly to the Five Phases.

6 The chapter lists the twenty anomalies that occur when one of the Five Phases interferes with another phase. Accordingly, the chapter title appears to imply a principle of “forewarned is forearmed”; that is, if one knows that certain configurations of the Five Phases (or, equivalently, the Stems and Branches) are apt to cause disorder or calamity, it might be possible to institute measures to ward off the disaster or mitigate its effects.

The brevity of

chapter 62 and its derivative quality suggest that it is an excerpt from the

Huainanzi or an earlier common source. Like the other chapters in this subgroup, it provides a reference point and an explanation for understanding and interpreting anomalies within a Five-Phase framework. Because

chapters 61 and

62 quote material that is consecutive in

Huainanzi 3, these two

Chunqiu fanlu chapters might once have been a single text.

Chapter 63, “Aberrations of the Five Phases and Their Remedies,” follows a formulaic scheme similar to that of

chapters 61 and

62. It runs through each of the five phases—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water—defining what an “aberration” in each phase is, what specific governmental policies cause it to occur, what its impact on the common people will be, and what policies can remedy the untoward situation. Again, this chapter is in the spirit of the “Yue ling” and similar annual calendars that link yin-yang and Five-Phase effects to the annual round of the seasons. The chapter is prescriptive and rather moralistic, and its policy prescriptions are so general that they provide little practical guidance for managing government affairs. Nevertheless, the concise and formulaic language of this chapter, like that of the two that precede it, suggests that it may have originated in some kind of early almanac that circulated in governmental circles as a handy reference to help the ruler and his officials track anomalous occurrences and respond to them in cosmologically satisfactory ways.

Chapter 64, “The Five Phases and Five Affairs,” also prescribes the ruler’s activities based on a Five-Phase cosmological scheme, but on the basis of a Five-Phase scheme different from that in the previous chapters of this group. Whereas

chapters 58 through

63 follow the Mutual Production Sequence (Wood/Fire/Earth/Metal/Water),

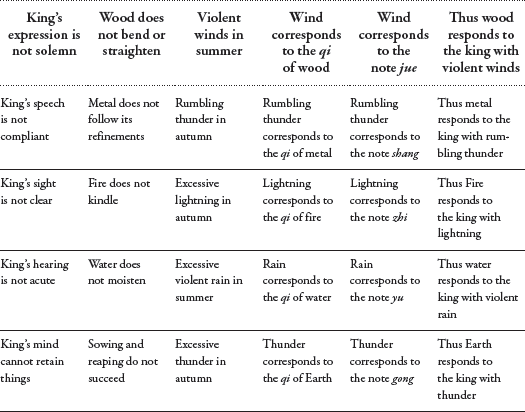

chapter 64 follows the Mutual Conquest Sequence expressed in passive terms (Wood is overcome by Metal, which is overcome by Fire, which is overcome by Water, which is overcome by Earth, which is overcome by Wood). The chapter consists of two essay fragments. Although both are related to the “Great Plan” chapter of the

Documents, they could not have originally belonged to the same essay. Section 64.1 is a fragment that explains the various disruptions that occur to Wood, Metal, Fire, Water, and Earth when the ruler fails to conduct himself in accordance with the Five Affairs (

wu shi 五事) of the “Great Plan”: when his expression is not solemn, when his speech is not compliant, when his sight is not clear, when his hearing is not acute, and when his mind cannot retain things. The correlations are shown in

table 3.

Section 64.2 contains three explications of the section of the “Great Plan” that defines the ruler’s Five Affairs. The first explication concerns the ruler’s expression, speech, sight, hearing, and thought. The second focuses on the qualities that those mental processes should ideally manifest: respectfulness, compliance, clarity, astuteness, and retentiveness. The third addresses the solemnity, eminence, wisdom, deliberation, and sagacity that are engendered by the ruler’s respectfulness, compliance, clarity, astuteness, and retentiveness. The concluding portion of this explication leaves aside sagacity and its correlate phase, Earth, and associates the ruler’s remaining four ideal qualities with the four seasons. It argues that when the ruler realizes these qualities, nature runs smoothly: the qi of each respective season functions as it should. Last, this section identifies the anomalies that will result if the ruler implements unseasonable policies.

The list of policies prescribed for the ruler in this chapter once again departs from those recommended in previous chapters. Unlike some of the other chapters in this group, section 64.2 follows the four natural seasons without adding an artificial season of “midsummer.” Interestingly, it does not mention the Five Phases as such, though they are implied in the chapter’s seasonal correlations. The content of the chapter, which is in somewhat garbled condition, suggests that it was the work of an exegete of the

Documents, someone like Liu Xiang, who developed a reputation for his interpretations of the “Great Plan.”

Taken as a group, these chapters are certainly linked thematically by their Five-Phase cosmology and their use of the rudiments of this cosmology to describe policies that should be implemented by the ruler and his highest officials. They specify which policies are commensurate with each phase and warn against actions that would disrupt the sequential flow of the Five Phases. The policies identified as being commensurate with the Five Phases are inconsistent across the different chapters, however. In addition, the chapters differ in their understanding of the pertinent sequence of the Five Phases. Thus

chapters 58 through

63 take as their starting point the Mutual Production Sequence: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water; even

chapter 59, which deals with the Mutual Conquest Sequence, arranges its content in Mutual Production order. In contrast,

chapter 64 discusses the seasons in the order spring-autumn-summer-winter, corresponding to the passive version of the Mutual Conquest Sequence: Wood, Metal, Fire, Water, and (Earth). These differences suggest that at a minimum, not all these chapters were written by the same person. Are any of them the work of Dong Zhongshu?

Issues of Dating and Attribution

Over the centuries, scholars both East and West have extensively studied the chapters of

group 6 and have uniformly expressed doubts that some or all of them are the authentic work of Dong Zhongshu. In fact, they are linked to Dong tenuously, if at all, because there is no indication, in either works confidently attributed to Dong or contemporaneous sources that give reliable information about him, that he ever incorporated Five-Phase concepts into his cosmological theories. In contrast, there is strong evidence that he drew heavily on yin-yang theory to formulate his general cosmological views and on the concept of

ganying 感應 resonance to develop his interpretations of portents and anomalies. These cosmological views, as seen in the chapters in

group 5, “Yin-Yang Principles,” were closely tied to the

Spring and Autumn as interpreted in the

Gongyang Commentary. Furthermore, the chapters in

group 6 contain various kinds of evidence that link them to other intellectual figures, texts, textual traditions, or historical events that postdate Dong’s life.

The authenticity of the chapters in

group 6 is critical, as it determines the extent to which Dong Zhongshu may be acknowledged as an intellectual link in the development of Five-Phase cosmology between the earlier figure Zou Yan (305–240

B.C.E.) and the later Liu Xiang (77–6

B.C.E.) and Liu Xin (46

B.C.E.–23

C.E.). It now is clear that Lü Buwei (291?–235

B.C.E.), the patron of the

Lüshi chunqiu, and Liu An (179–122

B.C.E.), the patron of the

Huainanzi (completed in 139

B.C.E.), demonstrably played a much more important role in the transmission of Five-Phase cosmology between Zou Yan (about whom not much is known) and the Liu father and son.

7 A detailed discussion of this scholarship and these issues may be found in Sarah A. Queen’s

From Chronicle to Canon, so we will summarize here only the most important conclusions.

8A Taboo Character

Taboo characters—characters that form part of an emperor’s personal name—can be of great value for dating texts. If a text uses a character that later becomes taboo, the text very likely dates to before the time when the character became taboo.

9 Conversely, if a text systematically avoids a taboo character (for example, by always employing a synonym for it), it likely dates from—or at least was copied in—the time after which the taboo took effect. Exactly that kind of internal evidence supports an Eastern Han date for

chapter 60. This chapter employs a term for a recommendation category—a category used to designate noteworthy candidates recommended for official posts in the bureaucracy because of a particular outstanding quality—that became current in the Eastern Han only in the time of Emperor Guangwu. The term

maocai 茂才 (cultivated talent) officially replaced the earlier Western Han term

xiucai 秀才to avoid the taboo on

xiu, which was part of Guangwu’s personal name. Therefore,

chapter 60 probably was written no earlier than, and possibly after, the reign of Emperor Guangwu (r. 25–58

C.E.).

Derivative Materials

In contrast to

chapter 60, internal evidence supports an early date for

chapters 61 and

62 (though not necessarily an early date for their incorporation into the

Chunqiu fanlu). As noted earlier,

chapter 61, “Controlling Water by Means of the Five Phases,” and

chapter 62, “Controlling Disorders by Means of the Five Phases,” are virtually identical to sections of the

Huainanzi’s

chapter 3, “Celestial Patterns.” Lacking introductory or concluding remarks, they appear in the

Chunqiu fanlu as essay fragments or excerpts. This contrasts with the

Huainanzi chapter, in which they are well integrated both stylistically and philosophically. These passages appear to have been copied into the

Chunqiu fanlu either directly from the

Huainanzi or from some common third source. Thus these two chapters are almost certainly not attributable to Dong Zhongshu.

Chapter 63, “Aberrations of the Five Phases and Their Remedies,” also appears, on stylistic grounds, to have been copied from some (now unknown) source text. Moreover, because there is no evidence that Dong Zhongshu based his system of omen interpretation on the Five Phases, the content of

chapter 63 argues against its being his work. The same is true of

chapter 64, “The Five Phases and Five Affairs,” which is based on the canonical “Great Plan” chapter of the

Documents and thus is characteristic of the Han tradition of omen interpretation that developed around that text. It most likely was written by an exegete of the

Documents working in that tradition. In contrast, Dong Zhongshu derived and developed his ideas on portents and omens based on the

Spring and Autumn and especially on the

Gongyang Commentary.

Dong Zhongshu and Five-Phase Theory

The following description of Dong’s exegetical activities and cosmological theories, taken from the “Treatise on the Five Phases” in the Han shu, makes clear that Dong and some of his successors had quite different views of the theories:

When the Han arose, it followed on the aftermath of the Qin destruction of learning. In the days of [Emperors] Jing and Wu, Dong Zhongshu mastered the

Gongyang Commentary to the

Spring and Autumn, first put forward his yin-yang theories, and was honored by the Confucians. After the days of [Emperors] Xuan and Yuan, Liu Xiang mastered the

Guliang Commentary to the

Spring and Autumn, enumerating the inauspicious and auspicious omens [found in them]. His teachings were based on the “Great Plan” [of the

Documents] and differed from [those of] Dong Zhongshu. Xiang’s son Liu Xin mastered the

Zuo Commentary to the

Spring and Autumn. His interpretations of the

Spring and Autumn also were quite extensive. In discussing the commentaries on the Five Phases, he differed as well [from Dong Zhongshu.] For this reason, when citing Dong Zhongshu, I [Ban Gu] have distinguished him from Liu Xiang and Liu Xin.

10

Dong Zhongshu, Liu Xiang, and Liu Xin, three towering intellectual figures of the Han period, thus followed three different commentarial traditions: the

Gongyang,

Guliang, and

Zuo commentaries, respectively. But differences among their cosmological theories go beyond the commentaries from which they drew their inspiration. Implicit in the

Han shu’s description of their views is a distinction between yin-yang and Five-Phase cosmology, with Dong firmly identified as favoring the former. Note that the “Treatise on the Five Phases” states that during the reigns of Emperors Jing and Wu, Dong Zhongshu first put forth his “yin-yang theories, and was honored by the Confucians” as a consequence. Had Ban Gu wished to identify Dong with Five-Phase cosmology, he would no doubt have done so in this passage, in which he clearly identifies Liu Xiang and Li Xin with Five-Phase doctrines. Ban Gu states that Liu Xiang’s “teachings were based on the ‘Great Plan’ [of the

Documents] and differed from [those of] Dong Zhongshu.” In addition, the eighty-seven examples of Dong’s official responses (

dui 對) to queries about omens in

Han shu 27, another place in which we would expect to find evidence of any links between Five-Phase cosmology and Dong’s omenology, refer only to yin-yang concepts.

11 (We discuss Dong’s yin-yang views at length in our introduction to

group 5, “Yin-Yang Principles.”)

There is no evidence that Dong wrote the Five-Phase chapters of the

Chunqiu fanlu. There is little overlap between them and Dong’s verifiable views. They were likely written by different authors, some of whom predated or were roughly contemporary with Dong (

chapters 61,

62, and possibly

63), and some of whom lived after him (

chapters 58,

59, and

60). The author of one chapter may have been a contemporary of Dong Zhongshu, working in the exegetical tradition associated with the

Documents, possibly Liu Xiang or an exegete closely associated with him (

chapter 64).

Even though these chapters are not Dong’s work, they are both interesting and valuable. They draw on a long tradition of antecedents stretching back to the third century

B.C.E., perhaps to the (now mostly lost) theories of Zou Yan and certainly to such extant works as the “Monthly Ordinances” (Yueling), the earliest version of which is found in the

Lüshi chunqiu. They help us understand how Five-Phase cosmology developed and how it was applied to political concerns by authors during the Han who sought to derive norms based on it. They also illuminate how Five-Phase theory may eventually have been accepted by and incorporated into the tradition of Gongyang Learning.

12The “Current Dynasty” and the Five Phases

The materials comprising the Five-Phase group provide a window into a polemic whose place in the intellectual history of the Han has not been adequately appreciated. The role of Five-Phase theory in Han cosmological debates, its relevance to the politics of the time, and its ramifications in a range of politically charged issues such as calendrical reform and imperial ritual and regalia shed light on this group of chapters and provide additional evidence for assessing their dating and authorship.

One of the most important political tenets of Five-Phase theory was that each dynasty ruled with the power and authority of one or another of the phases. Identifying the ruling phase was thus a matter of the utmost importance, as getting it right meant that the dynasty would be aligned with the force of the cosmos itself, and getting it wrong was to place the dynasty at odds with Heaven’s norms.

Chapter 58, “The Mutual Engendering of the Five Phases”;

chapter 59, “The Mutual Conquest of the Five Phases”; and

chapter 60, “Complying with and Deviating from the Five Phases” all identify the “current dynasty” with the Fire phase of the Five Phases. This is extremely interesting and important to the dating of these chapters. As we shall see, the correlation of Fire with the Han dynasty was probably not hypothesized until well after Dong Zhongshu’s death and became accepted only late in the first century

B.C.E. The correlation of Fire with the Han achieved prominence with the writings of Liu Xin and was adopted officially in 27

C.E., two years after Emperor Guangwu assumed the throne as the first ruler of the restored Eastern (or Latter) Han.

Efforts to align dynastic politics with Five-Phase cosmology already can be found in late Warring States and Qin works, such as the

Lüshi chunqiu and parts of the

Guanzi. Evidence that such political-cosmological views were taken seriously and actively debated at court from the earliest years of the Han period is easy to find—for example, in the practices of the imperial cult. Worship of the Five

di (

wudi)—the Bluegreen, Red, Yellow, White, and Black Thearchs—was one of the Han’s most important imperial rites. It was instituted by the founding emperor, Gaozu (r. 202–195

B.C.E.), and continued for almost two centuries to the reign of Emperor Ping (r. 1

B.C.E.–5

C.E.). That monarch instituted the Suburban Sacrifice to Heaven, which superseded worship of the Five Thearchs. The issue of imperial worship remained unsettled, however, with change and counterchange until the reign of Wang Mang, when finally it was “firmly determined that worship should be addressed to Heaven, and that the services should take place at sites near the capital. From then (5

C.E.) until the end of the imperial period, Chinese emperors have worshipped Heaven as their first duty.”

13The influence of Five-Phase cosmology on the Western Han court extended far beyond the great religious center at Yong, where the shrines to the Five Thearchs were located. The question of the proper ruling phase of the Han dynasty provoked heated and prolonged debate at court. Establishing which of the Five Phases corresponded to the reigning dynasty was critical to the legitimizing rhetoric supporting the establishment of a dynasty, believed crucial to the dynasty’s success. The identification of the ruling phase was typically accompanied by important regulatory reforms initiated by imperial decree—for example, a change in the astronomical system (including the beginning of the calendar year), the type and color of sacrificial animals, and the color of imperial regalia, including court costume, flags and banners. As Michael Loewe explains: “Choice of the patron element [i.e., Phase] constituted a declaration of faith that the dynasty was entitled to its appropriate place in the universal and unbreakable sequence; it also affirmed the view of how the dynasty fitted in that cycle and thereby defined its relationship to its predecessors.”

14Determining which phase was the correlate of the current dynasty was very complicated. The issue hinged on three separate but related questions. The first was which Five-Phase cycle of change would be used to determine the correlate of the current dynasty. As the

Shiji and

Han shu records demonstrate, scholars might avail themselves of two prevalent cycles. One was the Mutual Conquest Sequence associated with Zou Yan and adopted in the

Shiji, particularly the “Treatise on the Feng and Shan Sacrifices.” Typically expressed in passive terms, it yielded the sequence Wood-Metal-Fire-Water-Earth, in which each phase is said to be conquered or overcome by the one that follows: Wood is overcome by Metal (cutting tools), which is overcome by Fire (melting), which is overcome by Water (dousing), which is overcome by Earth (damming), which is overcome by Wood (sprouting).

15 The other is the Mutual Production Sequence, associated with Liu Xin and adopted in the

Han shu’s “Treatise on the Pitch Pipes and Mathematical Astronomy.” It yields the sequence Wood-Fire-Earth-Metal-Water, in which each phase produces its successor: Wood produces Fire (burning), which produces Earth (ashes), which produces Metal (ores), which produces Water (molten metal), which produces Wood (irrigation). The Mutual Conquest Sequence governs processes in which violence brings about change, and the Mutual Production Sequence applies to processes of spontaneous evolution or production.

Which cycle was used to determine the present also weighed on the past because typically the appropriate phase for the current dynasty was determined in relation to the preceding dynasties. For the Han, those referred most immediately to the Zhou and Qin dynasties, but some scholars named schemes that went back farther in time, extending even to the Five Thearchs of legendary antiquity. Accordingly, which list of historical dynasties would be used and with which correlates was the second important question determining the debate. As we will see, in the Western Han, as exemplified by Sima Qian in the

Shiji, the historical chronology associated with Five-Phase theory reached back to the Yellow Emperor. In the Eastern Han, however, as exemplified by Liu Xin in the

Han shu, the historical chronology associated with Five-Phase theory reached back still farther to the time of Paoxi (or Fuxi), the first of the Three Kings.

The third question affected all the debate concerning the ruling phase of the current dynasty in both the Western and Eastern Han: Was the previous dynasty legitimate or illegitimate? This had important ramifications for the debate as the Western Han looked back at the Qin, and again as the Eastern Han looked back at Wang Mang’s interregnum from the perspective of Emperor Guangwu’s subsequent restoration of the Han. Different intellectuals maintained various views concerning whether these reigns should be considered legitimate or illegitimate and thus whether they should be included in the legitimate progression of the Five Phases. Once determined, the ruling phase for any given dynasty was supposed to stay the same as long as the dynasty maintained the Mandate of Heaven, which might last for decades or even centuries.

The First Emperor of Qin and the Reign of Water

According to the Shiji’s “Basic Annals of the Qin,” after the Qin ruler assumed his new title as emperor in 221 B.C.E., he declared Water to be the patron power of the dynasty:

The First Emperor advanced the theory of the cyclical revolutions of the Five Phases. He maintained that inasmuch as the Zhou had held the power of Fire and Qin had supplanted Zhou, to follow it would amount to negating Qin’s victory. Since the present time marked the beginning of the cycle of the power of Water, he altered the beginning of the year…. Court clothing, pennants, and flags all honored black [this color being the correlate of water]. With regard to numbers, he made six the standard [this number being the correlate of water]. All contract tallies and official hats were six inches, and the chariots were six feet. Six feet made one double-pace, and each equipage consisted of six horses. The [Yellow] River was renamed the Potent Water because it was supposed that this marked the beginning of the power of water. With harshness, violence, and extreme severity, everything was determined by law. For by punishing and oppressing, by having no humanity or kindliness, harmony or righteousness, there would come an accord with the numerical succession of the Five Phases [policies obtaining in winter, the seasonal correlate of water].

16

As Sima Qian makes clear in the Shiji’s “Treatise on the Feng and Shan Sacrifices,” the Qin identification with the Water ruling phase was contingent on a number of factors. First, the choice of ruling phase was typically associated with an omen that signaled its ascendancy. Second, the ruling phase was established with reference to the preceding dynasties. Third, it was accompanied by a number of reforms. Chief among them were a change in the first month of the calendar and the privileging of a color, number, musical tone, and style of government, all determined by the correlative characteristics of the dynasty’s ruling phase:

When the First Emperor of the Qin had united the world and proclaimed himself emperor, someone advised him, saying, “The Yellow Emperor ruled by the power of Earth, and therefore a yellow dragon and a great earthworm appeared in his time. The Xia dynasty ruled by the power of Wood, and so a bluegreen dragon came to rest in its court and the grasses and trees grew luxuriantly. The Shang dynasty ruled by metal, and silver flowed out of the mountains. The Zhou ruled by fire, and therefore it was given a sign in the form of a red bird. Now the Qin has replaced the Zhou, and the era of the power of water has come. In ancient times when Duke Wen of Qin went out hunting, he captured a black dragon. This is an auspicious omen indicating the power of Water.” Consequently, the First Emperor of Qin changed the name of the Yellow River to “Potent Water.” He established the tenth month of winter as the beginning of the year; with regard to color, he honored black; with regard to measurements, he established six as the standard; with the tones he honored

dalu; and with affairs of government, he honored law above all else.

17

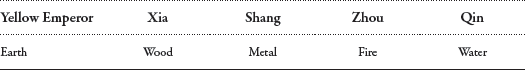

As this passage indicates, the Qin choice of Water as the ruling phase depended on identifying the ruling phases of previous dynasties. The correlations accepted as valid by the court cosmologists are presented in

table 4.

18 From these correlations, it is clear that the sequence followed in determining that Water was the appropriate correlate for the Qin was the “passive” Mutual Conquest Sequence in which Wood is conquered by Metal, Metal is conquered by Fire, Fire is conquered by Water, and Water is conquered by Earth.

The Han Dilemma: Water or Earth?

The

Shiji suggests that discussions to determine the ruling phase for the Western Han surfaced quite early, under the reign of Emperor Gaozu, but that a full century of discussion and debate would ensue before the issue was finally settled during the reign of Emperor Wu. Apparently, shortly after assuming the throne, Emperor Gaozu expressed support for the power of Water. He is said to have declared, “The altar of the north awaits me to be erected.”

19 Since the north was associated with the Water phase, Gaozu’s statement was interpreted as an affirmation that the dynasty had rightly obtained the power of Water, inheriting it from the preceding Qin dynasty. This reading was confirmed by Zhang Cang, a high-ranking official who had served the Qin and who may have harbored personal reasons for continuing the Qin agenda.

Ming Xili and Zhang Cang supported the emperor’s suggestion that the Han simply conform to the Qin calendar and color of court vestments by citing a number of additional factors: “The empire is just beginning to become settled; the square grid pattern [of the imperial capital] is just being laid out; the high empress and her court ladies do not yet have leisure [to sew and embroider new court garments in a different color]; thus it is appropriate to conform to the first month of the year and the color of court vestments established by the Qin.”

20Given the brevity of Qin rule, Emperor Gaozu of the Han might naturally have assumed that the Water phase had not yet exhausted its power and therefore it was appropriate to simply assume the Qin’s ruling phase. In any case, he pursued that policy, augmenting the reign of the Water phase by establishing an altar to the Black Thearch.

21Zhang Cang appears to have been a key factor in the continuation of Qin practices, not only during the reign of Emperor Gao, but during the succeeding reign of Emperor Wen as well. During the latter’s reign, when Zhang served as chancellor, he opposed proposals by Gongsun Chen and Jia Yi that the Han be identified with the Earth phase.

22 Gongsun Chen, for example, following the logic that Earth conquers Water, just as the Han had conquered the Qin, submitted a letter to the throne:

Formerly the Qin dynasty ruled by the power of Water. Now that the Han has succeeded the Qin, in accordance with the revolutions of the Five-Phase sequence, Han must [correspond to] the power of Earth. The [confirming] response [from Heaven that this is the case] will be the appearance of a yellow dragon. It is proper, then, to alter the first month of the year, change the color of court vestments, and honor the color yellow.

23

After the letter was received, the emperor directed Zhang to call a court deliberation to discuss the matter. Zhang, who enjoyed a reputation for being well versed in astronomy and mathematical harmonics, was in a position to speak authoritatively on the subject and apparently did so. He contended that the Han belonged to the period in which the power of Water was still in the ascendancy. Thus the Yellow River having burst its dikes at a place called Metal Embankment (that is, Water was ascendant over Metal, which generates it according to the Mutual Production Sequence) should be taken as the verification: “Now the year begins in winter in the tenth month, and the colors of court vestments are black on the outside and red on the inside, corresponding perfectly to the power [of Water]. Gongsun Chen’s opinion is false, and the matter should be dropped.” Despite the apparent finality of Zhang Cang’s opinion, the matter was soon reopened because an omen did appear to confirm Gongsun Chen’s prediction. As the “Treatise on the Feng and Shan Sacrifices” explains, “Three years later, a yellow dragon appeared in Chengji. Emperor Wen thereupon summoned Gongsun Chen to court, made him an Erudite, and set him to work with the other court scholars to draft a plan to alter the calendar and the color of court vestments.” The emperor subsequently issued an edict confirming the appearance of the auspicious creature, declaring his intention to perform the Suburban Sacrifice, and calling on his officials in charge of the rites to deliberate the matter and set forth their recommendations.

24Emperor Wen followed through in the summer of the same year, when he personally performed the Suburban Sacrifice to the Five Thearchs north of the Wei River. Having recently come under the influence of a man from Zhao named Xinyuan Ping, the details of the performance were influenced heavily by the interpretations of this new favorite. Emperor Wen seemed to be on the verge of making momentous changes that would have included an imperial declaration of Earth as the new reigning phase. But after the emperor had performed the Suburban Sacrifice, Xinyuan Ping’s interpretations were deemed fraudulent. Exhausted and disgruntled by the affair, the emperor is said to have “lost interest in changing the calendar and the color of court vestments and in matters concerning the spirits.”

25 Even though the sacrificial officials maintained the requisite ceremonies, the emperor did not again visit the altars or personally offer a sacrifice. Nor did he ever declare a change in the ruling phase of the Han. During the reign of Emperor Jing, discussions to determine the dynasty’s ruling phase thus appear to have abated, perhaps because of the emperor’s lack of interest in it.

The declaration of a new ruling phase of the Han and the promulgation of a new calendar came with Emperor Wu, who finally instituted the earlier recommendations of Gongsun Chen and Jia Yi and declared Earth as the patron phase of the Han in 104 B.C.E. This momentous change was duly noted in the “Treatise on the Feng and Shan Sacrifices”:

In the summer [of 104

B.C.E.] the calendar of the Han dynasty was changed so that the official year began with the first month. Yellow, the color of Earth, was chosen as the color of the dynasty, and the titles of the officials were recarved on seals so that they all consisted of five characters, five being the number appropriate to the phase Earth. This year was designated as the first year of the era

taichu, or “Grand Inception.”

26

The Han shu’s “Annals of Emperor Wu” also recorded:

In the summer, the fifth month, [the emperor] corrected the calendar and took the first month as the beginning of the year; [among] the colors, he took yellow [as the ruling color], and [among] the numbers, he used five. He fixed official titles and harmonized the sounds of the musical pipes.

27

The basic impetus of the Grand Inception reform of 104

B.C.E. was the need to correct the computational system used to calculate the dates and locations of various phenomena that appear in the sky, including solstices and equinoxes, phases of the moon, positions of the planets, and the astrological implications of all of these.

28 Because all such astronomical systems accumulate errors over time, occasionally it is necessary to recalibrate them. Toward the end of Emperor Wu’s reign, it was obvious (for example, from disparities in the dates of the equinoxes and solstices) that the computational system required correction. The necessary corrections were made, and the promulgation of the Grand Inception calendar provided the occasion for a corresponding rethinking of the Han dynasty’s ruling phase. Perhaps reflecting Emperor Wu’s confidence that the Han securely possessed the Mandate of Heaven and was not merely a continuation of the Qin dispensation, the ruling phase was finally changed from Water to Earth. The Grand Inception reform involved not only changes in the astronomical system itself but also comprehensive changes in the color and design of vestments and emblems; the recalibration of weights and measures and of the standard pitch of musical notes; as well as changes in numerology, astrology, cosmology, historiography, and other fields that had implications for political, ethical, and moral thought.

29During the final decades of the Western Han and into the Eastern Han, the need for further reform of the astronomical system once again became the focus of a wider debate. A new position began to emerge from Five-Phase theory that pertained to the dynasty’s ruling phase, along with much else. The new consensus depended largely on the developing views of the famous polymath courtiers Liu Xiang (77–6

B.C.E.) and his son Liu Xin (ca. 50

B.C.E.–23

C.E.).

30 The

Han shu’s “Treatise on the Suburban Sacrifice” says,

Liu Xiang the father and his son [Liu Xin] maintained that the [cycle of] thearchs began with [the Earthly Branch]

chen, therefore Master Paoxi [i.e., Fuxi] was the first to receive the power of Wood. His descendants through the maternal line [were part of] an endless cycle that ended and began anew from Shen Nong and the Yellow Emperor down through the ages to Tang Yu and the Three Dynasties to the Han, who obtained the power of Fire.

31

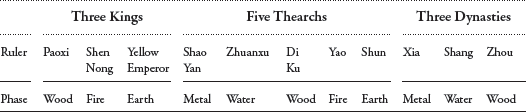

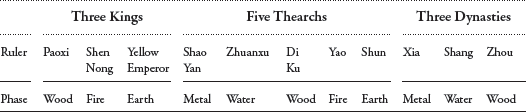

This new view of Five-Phase theory had two aspects. The first was the correlation of the phases with ever more distant dynasties stretching all the way back to the legendary Three Kings Fuxi, Shen Nong (the Divine Farmer), and the Yellow Emperor and progressing through the Five Thearchs (Shao Yao, Zhuanxu, Di Ku, Yao, and Shun) and the Three Dynasties (Xia, Shang, and Zhou) to the Han.

32 The second was a shift from the old paradigm of using the (passive) Mutual Conquest Sequence of the Five Phases to calculate the ruling phases of sage-emperors and dynasties to a new one using the Mutual Production Sequence for the same purpose. Thus the sage-emperors and dynasties were associated with phases entirely different from those calculated according to the Mutual Conquest Sequence in the Grand Inception calendar to confirm the legitimacy of the Han conquest over the Qin, but in the view of Liu Xiang and Liu Xin, the Mutual Production Sequence was better suited to the emergent historical narrative of peaceful dynastic change. In this historical narrative crafted by Liu Xin, the Qin dynasty was deemed illegitimate and the Han became associated with the power of Fire. This new historical narrative was laid out in detail in the “Treatise on the Pitch Pipes and Mathematical Astronomy”

33 incorporated into the

Han shu. The correlations associated with this new narrative are represented in

table 5. The treatise explains: “The August Emperor of the Han, Gaozu, promulgated a written document, [saying that] we have chastised the Qin and [directly] succeeded the Zhou. Wood engenders Fire, therefore [Han] corresponds to the power of Fire.”

34TABLE 5

This historical sequence that now identified the Han dynasty with Fire spurred a new round of computational reform. Liu Xin had begun working on computational issues early in the reign of Emperor Cheng (r. 32–6

B.C.E.), and his

san tong (Triple Concordance) astronomical system was promulgated in 7

B.C.E. Its mathematical features did not amount to a complete reform of the Grand Inception system, as it merely revised some of its key features. But the emperor, approving of Liu Xin’s recommendations, took the opportunity presented by the new calendar to adopt comprehensive changes in regalia, weights and measures, music, and so on, all reflecting the new understanding that Fire was the ruling phase of the Han. Thus by the end of the Western Han, both Emperor Wu’s adoption of Earth as the dynasty’s ruling phase and his Grand Inception astronomical system had been repudiated, replaced by the consensus that Fire was the dynasty’s ruling phase as embodied in the Triple Concordance system.

Wang Mang

These developments in Five-Phase discourse, with associated upheavals in numerology, metrology, omenology, and other esoteric fields, laid the crucial intellectual groundwork on which Wang Mang built his case that he was the legitimate successor to Emperor Ping of the Han. As emperor of the Xin dynasty, he argued that he ruled under the reigning power of Earth because, according to the Mutual Production Sequence, Fire engenders Earth. Accordingly, we find the following verification in the Han shu’s “Biography of Wang Mang” that the power of Fire was destined to give way to that of Earth:

The red stone at Wugong appeared in the last year of Emperor Ping of the Han dynasty, when the virtue of Fire had been completely dissipated and the virtue of Earth was due to take [its] place]. August Heaven was solicitous [on account of this circumstance] and so rejected the Han [dynasty] and gave [His Mandate] to the Xin [dynasty], using the red stone as its first Mandate to the Emperor. The Emperor, [Wang] Mang, however humbly refused to accept [this title] and hence occupied [the throne] as regent.

35

Wang Mang’s reception of the Mandate on January 8, in 9 C.E., is described as follows:

The day of receiving the Mandate was

dingmao [sexagenary day 4].

Ding is Fire, which is the virtue of the Han dynasty;

mao is what makes the [Han dynasty’s] surname, Liu, into this written character [the surname Liu

劉 is written by adding the radical

mao 卯 to the word

zhao 釗]. It makes plain that the virtue of Fire, [which was that of] the Han [dynasty] and of the Liu [clan], is exhausted, and that [the Mandate] has been transmitted to the house of Xin.

36

Finally, Wang Mang promulgated a new astronomical system, although it was essentially the same as Liu Xin’s Triple Concordance system with minor modifications.

37 Nonetheless, this act proclaimed to the world his belief that the new dynasty’s Mandate was secure.

Emperor Guangwu

Wang Mang’s abortive Xin dynasty collapsed in 23

C.E. After two years of chaos, rebellion, and civil warfare, the Han imperial kinsman Liu Xiu mounted the imperial throne in 25

C.E., proclaiming the restoration of the Han dynasty. (At that time, the imperial capital was moved to Luoyang, giving the Latter Han dynasty its alternative name of Eastern Han.) The

Hou Han shu’s “Annals of Emperor Guangwu” reports that in 27

C.E., the emperor engaged in a number of solemn religious acts. They depicted his reign as a restoration of the Han: he erected a temple to the founding father of the Han, Emperor Gaozu; he established an altar of Heaven at Luoyang; and he built the suburban altar south of the city. He also proclaimed Fire to be the dynasty’s ruling phase, thereby affirming with very powerful symbolism that his dynasty was a restoration of the Han and a continuation of its Mandate, not an entirely new regime. (Emperor Guangwu also took the retrograde step of restoring many of the Western Han’s regional kingdoms, with various imperial princes as kings, thereupon bequeathing no end of trouble to his successors.)

38Implications for the Dating and Attribution of the Five-Phase Chapters

To recapitulate: the First Emperor of Qin chose Water as the ruling phase of his dynasty, having conquered the Zhou, whose ruling phase was taken to be Fire. The Qin’s choice of Water remained in force under the Han emperor Gaozu and his immediate successors, signifying that the Han had inherited Qin’s Mandate and ruled by its same phase. Emperor Wu instituted Earth as the ruling phase as part of the Grand Inception astronomical system reform of 104

B.C.E., based on the argument that Earth overcomes Water, just as the Han had overcome the Qin. Emperor Cheng accepted Liu Xin’s arguments that the Mutual Production Sequence, rather than the Mutual Conquest Sequence, governed the choice of a ruling phase. Accordingly, he proclaimed Fire as the ruling phase of the Han as part of the Triple Concordance astronomical system reform of 7

B.C.E. (This assumes that the Qin dynasty was illegitimate and that the Han succeeded directly to the Mandate of the Zhou, whose ruling phase was Wood.) Wang Mang accepted that logic and so chose Earth (engendered by Fire) as the ruling phase of the Xin dynasty. The Latter Han emperor Guangwu reverted to Fire as a symbol that his dynasty was a restoration of the Han, and Fire remained the ruling phase for the duration of the Latter Han.

39 All these choices involved new arguments about the ruling phase of the Zhou dynasty and its predecessor dynasties and sage-emperors.

Although Wang Mang, like Emperor Wu before him, chose Earth as the patron phase of his dynasty, as Michael Loewe argued many years ago

40 and as our research has affirmed, he did so for very different reasons. Emperor Wu justified his identification with Earth with references to Qin’s identification with Water and followed the Mutual Conquest Sequence. In contrast, Wang Mang’s identification with Earth was based on the understanding that Han ruled by the power of the Fire phase, a position that was articulated by Liu Xin in the waning years of the Western Han and assumed that the Mutual Production Sequence was the proper way to determine the ruling phase. This theory was opportune for Wang Mang, who wished to present himself as the legitimate successor to the Han. (He encouraged the idea that he had come to the throne not by conquest but because the last emperor of the Han had peacefully ceded the Mandate to him, even though the Mandate, in classical theory, was conferred by Heaven, not passed from one human to another.)

We have seen that

chapters 58,

59, and

60 identify the “current dynasty” (

ben chao) with Fire. Up through the time of Emperor Wu and for several decades thereafter, the Han debate on the ruling phase was confined to either Water or Earth. The question of Fire entered the debate only with the theoretical work of Liu Xin near the end of the Western Han. The choice of Fire was accepted by Emperor Guangwu in 27

C.E. and remained in force for the duration of the Latter Han. Thus the essays that identify the “current dynasty” with Fire cannot date to a time earlier than Liu Xin (ca. 50

B.C.E.–23

C.E.) and are most unlikely to be earlier than the reign of Emperor Guangwu. They are, in other words, very likely to date from some time in the Latter Han period. The entire group of Five-Phase chapters in the

Chunqiu fanlu (

chapters 58–

64) thus appears to span a time period from the early Han (

chapters 60 and

61) to sometime in the Latter Han. As such, they are a valuable record of the development of Five-Phase theory and its gradual incorporation into the Confucian mainstream via the masters of Gongyang Learning. That none of these chapters can plausibly be associated directly with Dong Zhongshu and that some certainly cannot have been written by him, is noteworthy but does not diminish their inherent value.

Finally, it is interesting to observe that the Mutual Production Sequence of the Five Phases lends itself easily to interpretations linked to the production of life as a parent produces offspring. In this line of reasoning, the relationship of the Xin dynasty to the Han, for example, would be that of a son to his father. We might therefore expect the virtue of filial piety to come into play in the development of Five-Phase theory, and this does turn out to be the case: the

Hou Han shu records a dialogue between a disciple and a teacher that says in part: “The Han wielded the power of Fire; Fire is born from Wood; Wood reaches its apogee in Fire; thus its power is that of filial piety.”

41 Are there essays in the

Chunqiu fanlu that might conform to such a view? The only other chapters that develop Five-Phase theory,

chapters 38 and

42, do just this.

42 They promote the ethical value of filial piety in a Five-Phase scheme that privileges Earth and thus appear to represent a moment of integration of Five-Phase theory into Han Confucian ideology.