Problems and Tactics Table: Emotions

Despite the fact that we humans pride ourselves on our cognitive abilities, we are heavily, if not dominantly, influenced by emotion when assessing the quality of a product. Although we separate cognition and emotion for convenience in discussing them, they are not independent of each other. At one time people tended to treat cognition and emotion as separate and perhaps conflicting human motivations. In 1956 Benjamin Bloom chaired a group of educators who identified three separate domains of learning: the cognitive (mental skills—evaluation, analysis, comprehension, recollection, synthesis), the affective (growth in feelings or emotional areas—values, motivation, attitudes, stereotypes, feelings), and psychomotor (manual or physical skills).1 But present-day research shows otherwise, as is not surprising since we only have a single brain to be involved in all of these functions.

Our actions and responses are molded by a combination of thought and emotion. We are creatures of both nature and nurture. In some cases thinking may dominate, and in others emotion. Sometimes our responses are logical, and sometimes they reflect our past and our wiring. Without the emotional element, Homo sapiens would not have made it this far because the human thinking process is too slow to handle many of life’s difficulties and is not very good with uncertainty and high complexity.

Even in the case of supposedly logical actions and responses, emotions are involved. Emotions can, and do, rapidly summarize situations and provide plans of action. Clinical studies have shown that people who for one reason or another suffer from impaired emotional responses have difficulty in making decisions.2 Emotions, after all, are responsible for the “feel” that guides the research scientist, the chief executive officer, and the president of the United States. Intuition communicates with us through emotions. Psychologists sometimes use the term thin slicing to designate the ability to find patterns and reach decisions based on extremely narrow windows of experience—too narrow to do the sort of thinking we would expect is necessary to complete the task. For example, our rapid sizing up of new people we meet results from this emotional function. Such workings of the mind speak to us through emotion (such as dislike of the person we are meeting for the first time) just as do many, if not most, aspects of product quality.

Take something as obvious as the appearance of products. Part of the success of Apple is that people simply “like” (an emotional response) the appearance and feel of the company’s products, often independently of function. Logic often takes second place to emotion. Purely functionally speaking, the argument could be made that high-heeled shoes by Jimmy Choo and Manolo Blahnik are not worth the price. But the success of the brands shows that not all people agree. Function is overwhelmed by emotion.

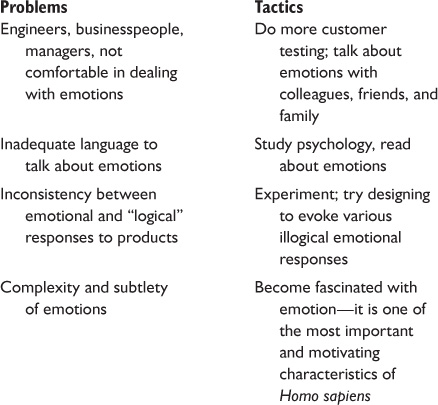

If a user loves a product, everyone involved benefits—if the user hates it, everyone loses. A great deal of effort goes into attempting to measure and predict emotional response by people involved in marketing, design, psychology, and other fields. Such research ranges from simply talking to people through observing them in action, to subjecting them to carefully controlled tests. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, there are no formulas that allow us to optimize emotional responses, nor are there precise metrics that measure them directly. Nor are the mechanisms sufficiently understood to build simulations. Often words, mathematics, and computer simulations fail us when dealing with emotions. For this reason, emotional response is something that many in engineering and business are relatively uncomfortable with, compared to such usually quantified characteristics as performance and cost (although there, too, as discussed in Chapter 3, quantification falls short).

Society demands that all of us to some extent control our emotions. I was fascinated by my grandchildren during their terrible twos. They expressed their emotions beautifully. They alternated between unmitigated outrage, bottomless love, unconstrained laughter, intense dislike, and passionate desire. But for obvious reasons, society (parents?) had already been hard at work attempting to convince them to soften these expressions. Of course, we could not afford to have the seven billion people in the world be as honest about their emotions as two-year-olds, but in a way we have all been trained to conceal, if not lie about, our emotions. This is especially obvious in the case of primitive and vital emotions such as those involved with spreading our gene pool. If we exhibited and acted upon all our true emotions, we would probably be neither as popular nor as effective in life. We have all learned to be nice to people we don’t like, modulate our more animal feelings toward attractive strangers, and pretend interest in things that interest our friends.

People not only have been taught to conceal their feelings, and do not have adequate language to communicate them, but also may not always be sure how they actually do feel. This situation certainly handicaps designers and producers of hardware products from matching the needs and desires of the users. Books, magazines, newspapers, movies, and music CDs are products of industries in which great effort is spent on evoking emotional responses in the user. But although industries producing products such as clothing, automobiles, cosmetics, and food necessarily think deeply and continually about emotion, they often still come up short. And how about the makers of crowbars, backhoes, and chain hoists? They perhaps don’t even consider emotions that deeply. But they should, because emotions affect both the design of the product and the user’s happiness with it.

Companies seeking to produce high-quality products can always benefit from becoming more sensitive to human emotions—their own, those of people involved in selling, manufacturing, using, and servicing the product, and those of their coworkers or employees. And a good way to foster this sensitivity is simply to become more interested in emotions as a central characteristic of humans. Emotions rule us, but we don’t know much about them. They involve our senses, our mind, and our bodies, yet they give us simple messages. While going to school for a significant part of our lives, we hear little of them in most of our classes.

Chapters 3 and 4 deal with analytical material, in which specific information is available, parameters can be quantified and measured, and tests can be conducted, but emotions are still involved. Certainly a chair that is comfortable adds more to a user’s happiness than one that is not. Many of the problems in human fit result not from lack of information and tools but rather from the relative low priority assigned to fit in the production-consumption process. Why? Maybe the emotions of the people who create products are playing a greater role than the emotions of the end users. Maybe it is more fun for designers to miniaturize devices than to worry about whether they are compatible with human hands. It is possible that designers are more interested in including new features in a product than worrying about whether the user will understand how to use them (conveniently, in many cases people seem to like miniature devices with lots of features more than they do human fit). The term technically sweet implies emotion on the part of the maker. As far as craftsmanship is concerned (Chapter 5), standards can be created for making things well and users can be tested for their response. But the aesthetic aspect of craftsmanship is more difficult to deal with analytically. The location of a steering wheel has to do with function, and automobile companies establish rules for such things (though if it is poorly placed, our emotions will come into play). But a beautiful surface finish will please us emotionally even if the surface finish serves no function.

Even academic psychologists have had trouble dealing with emotion as a topic. They like to research phenomena that can be replicated and quantified, and have traditionally lumped emotions together in the “affective domain,” while searching for their research support elsewhere. Most therapists attempt to approach their work rationally and would like their patients to be more “reasonable.” Emotions, however, often defy “reasonableness.”

There is not even a commonly accepted simple list of emotions. Some years ago Daniel Goleman, who was once editor of Psychology Today magazine and later the cognitive science editor of The New York Times, wrote a bestselling book entitled Emotional Intelligence. In the appendix, he lists the following labels for emotions:

• Anger: fury, outrage, resentment, wrath, exasperation, indignation, vexation, acrimony, animosity, annoyance, irritability, hostility, pathological hatred, violence

• Sadness: grief, sorrow, cheerlessness, gloom, melancholy, self-pity, loneliness, dejection, despair, severe depression

• Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, concern, consternation, misgiving, wariness, qualm, edginess, dread, fright, terror, phobia, panic

• Enjoyment: happiness, joy, relief, contentment, bliss, delight, amusement, pride, sensual pleasure, thrill, rapture, gratification, satisfaction, euphoria, whimsy, ecstasy, mania

• Love: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affinity, devotion, adoration, infatuation

• Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, wonder

• Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, abhorrence, aversion, distaste, revulsion

• Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, humiliation, regret, mortification, contrition3

Another influential classification was done by Robert Plutchik in 1980 in which he named eight primary emotions: anger, fear, sadness, joy, disgust, trust, surprise, and anticipation.4 He considered these emotions essential for survival and believed that they combine in various ways and intensities to provide secondary emotions. For instance, love would be a combination of joy and trust. Fury, rage, hostility, and annoyance would be different shades of anger.

There are many more such classifications, but although they are useful in attempting to achieve a standardized vocabulary and perhaps a model, they fall short of helping us in our quest for product quality. One can also quibble with these classifications. In my opinion Goleman’s and Plutchik’s categories sorely lack emotions that cause the feelings of desire (wanting, craving, coveting, wishing) and of frustration (thwarting). Such lists do demonstrate that people require a great many words to describe a type of emotion, and even with these words they cannot convey the feelings themselves.

When it comes to products, such lists can mislead through their attempt at simplification. As an example, it might be assumed that enjoyment, love, and perhaps surprise are “positive” emotions that increase quality of life, while fear and anger are negative. I am a firm advocate toward designing projects that stimulate “good” emotions, but is it bad to be angry at products that fail us? If I weren’t a bit afraid when I work on the top of tall ladders, I would quit climbing them. Also, there are many situations where people seem to seek these “negative” emotions and the products that stimulate them. Many people love roller coasters, motorcycles, skis, scary movies, and other products that somehow are successful because they induce fear. Do we need periodic adrenaline rushes? Do we gain enjoyment from the relief when the fear recedes? Is it that our harm-avoidance mechanisms need to be exercised once in a while?

University students during finals week have traditionally believed that the anxiety they feel allows them to perform better on their examinations. And there is a stable market for “entertainment” that triggers “negative” feelings. I am fascinated by the difference between my wife and me in this regard. She loves Edward Albee plays—the ones that have a somewhat light and humorous first act, a foreboding second act, and then trash you in the third. She leaves the theater raving about the wonderfulness of the acting and the play. I leave the theater wondering why I do this to myself. The same is true of movies—my wife is a great fan and a major supporter of Netflix. In the evening when I hear violin soundtracks and voices raised in anguish from the TV room, I am certain that she is in there with a box of tissues having a wonderful time.

Sigmund Freud has been pretty much discredited by academic psychologists, but he still lives on in much so-called talk therapy and in our culture. Freud initially believed that we are motivated to maximize our own pleasure (the pleasure principle) and wrote of the instincts for ego (self-preservation) and libido (sex). He soon came to realize, however, that we do not always act in that way. In particular, he could not explain war, in which people sometimes enthusiastically volunteer for an activity that at first glance might seem to be neither pleasurable nor consistent with self-preservation. He therefore added what he called a death drive that opposes the life drive. Freud’s life drive moves us toward preservation and happiness, while his death drive moves us in a direction inconsistent with that.

One of the constants in the history of Homo sapiens is war, and, especially in the United States, huge amounts of money and effort are spent designing, developing, and producing products for war. (The country seems proud of the ability to produce very “good” ones.) Despite the deaths of many millions, great destruction of property and wealth, and the dangers inherent in war throughout all of history, people continue to follow their leaders off to battle. The country’s best minds and a great deal of its capital are put into designing weapons and other war-related equipment. It is quite easy to understand Dr. Freud’s need for his death drive to explain the human psyche.

I have known few people who actually desire death, but many are clearly titillated with danger, violence, and evil, and they derive emotional benefits from risk. During a visit to New Zealand a few years ago, my wife and I stopped to watch some people skydiving. To my great amazement, my wife decided she would like to try it. Clearly violence and evil were lacking in this case and the actual risk and danger were low, not only because the sport itself is fairly safe but also because the first times one jumps, one is tied to an experienced jumper. But when you are falling a long distance through the air, you definitely get the impression that you could be in trouble.

When my wife was suited up and ready to go, she began having second thoughts, but there were several excited, much-younger, high-fiving local girls awaiting a ride, and she decided that if they could, she could. Away she went, and securely fastened to her coach, she arrived safely to the ground. When I went out to collect her, she looked fantastic. She was all wide-eyed and open-mouthed and giggly. That evening she announced that she had never been so scared as when she left the airplane, that she felt great, and that everyone should do at least one thing a year that terrified them, especially grandmothers (she is one).

How about you? Do you have a fascination with thrills and spills, with personal and vicarious physical risk? Do you partake in some activity that is perhaps a bit dangerous and slightly foolish? Would you like to go skydiving? Would you like to drive an Indianapolis race car? How about climbing Mount Everest? More than 200 people have died attempting to climb the mountain, and the majority of the bodies remain there.5 But there seem to be many people still desiring to make the attempt. Is the risk part of the attraction? Equipment used in so-called extreme sports also takes advantage of these emotions. Skis, surfboards, racing catamarans, snowmobiles, accessories for free-climbing, ultimate skiing, and even Rollerblades and skateboards qualify. The colors and graphics usually reinforce the feeling of danger and accompanying exhilaration. Generally the public is accepting of this situation.

Modern societies are ambivalent about products having to do with thrills, spills, and an increased risk of physical harm if the danger is appreciable. Consider the automobile—America’s favorite thrill toy. The association of the automobile with danger has been around as long as the automobile itself. All drivers are familiar with the thrill of going too fast or maneuvering too sharply. Car racing is an extremely popular sport, and when attending, fans are quietly excited by the danger to the drivers—quietly because they are not supposed to admit that this danger is part of the appeal.

Automobile manufacturers take advantage of these feelings in their design and advertising, sometimes to a ridiculous extent. Cars and even trucks with average performance at best are often portrayed in advertisements as bouncing over rough terrain, leaping through the air, or drifting around a curve. Automobile manufacturers associate themselves with racing by providing engines and sponsoring stock cars and dragsters with bodies that simulate the styling of production cars. Many innocuous family cars are also named after ferocious animals and racecourses and equipped with numerical designations that hint of experimental fighter planes. A large number of car-accident deaths occur per year in the United States (more than 32,000 in 2010),6 resulting in a parallel campaign toward safety and the environment, complete with air bags, crashworthiness, and government regulation. Usually the result is a type of honest schizophrenia, with the automobile designers and manufacturers simultaneously attempting to assure customers that the product is safe and that it is akin to a Formula One race car in thrills and performance.

Toys and games often take advantage of this fascination with death and destruction as well. On Halloween night, many more children (and adults) are dressed as Darth Vader than as Obi-Wan Kenobi. Popular computer games place participants in roles of warriors or other adventurers. Toy stores feature a wide variety of weapons, ranging from antique to futuristic. Attempts to do away with such war toys and “violent” games are numerous but only partly successful. I remember the frustration in one of our local nursery schools when the overseers discovered that their boy charges were bringing toy pistols to school. The toys were summarily outlawed, resulting in the children concocting gun replicas from sticks, tape, and pencils. The teachers announced that such action would also be illegal. The children then reverted to using their forefingers—the time-honored way for youngsters to shoot each other. (Fortunately, the school did not try to outlaw forefingers.)

Athletic competition is also successful because of these aspects of our emotions. Certainly football and ice hockey are games whose attraction is based on battle (offense, defense, line). The equipment used emphasizes this idea (for example, decorated hockey masks). There is nothing prouder, nor more incongruous, than a small kid togged out in oversize pads for a Pop Warner football game. The equipment used by motocross racers is reminiscent of both Roman legionnaires and Darth Vader. Professional football players are reasonably normal, although larger persons. But the equipment that makes them look like refugees from a contemporary Roman Colosseum is made by industry.

Most products do not expose the user to the level of fear, anxiety, exhilaration, and excitement that actually accompany danger and derring-do. But many of them try to imply such feelings, sometimes with success. I suspect that the prevalence of black on electronic equipment has something to do with World War II aircraft instruments. Harley-Davidson profits from its slight outlaw image, even though outlaws do not usually have the money to buy its products. Periodically the clothing business blossoms forth in olive drabs, epaulettes, camouflage, lots of pockets, and other such military motifs, and, after all, there are some 200 million guns owned by U.S. citizens, of which one-third are handguns. That’s a lot of products.

A major complexity in dealing with emotion stems from the great diversity in emotional responses among humans. I live on the campus of a top-ranked university located in an attractive and economically well-off region. A hundred miles from here is the agricultural Central Valley of California. For various reasons I go back and forth between the university and a farm owned by a good friend, and I am always amazed by the difference in emotional response to topics such as Barack Obama, the environment, water usage, the Prius, and the Iliad. California is an interesting collection of local “red” and “blue.” However, I don’t have to travel to find this range of feeling. Within a few blocks, I can find the gamut of Mr. Plutchik’s or Mr. Goleman’s emotions in all degrees of intensity focused on a myriad of issues and objects. I own a pickup in a sea of Volvos, BMWs, and Priuses. My informal clothing is sometimes described by my wife as “homeless wear.” I fill my yard with restored and partially restored farm machinery and other equipment. Although my professional credentials are impeccable and, as far as I know, I am well liked, I suspect friends and neighbors have mixed emotional responses to my lifestyle. I am not going to find out.

A good example of the wide variation in emotional response was seen in the 2008 U.S. election. Emotions toward the candidates and the issues, influenced by highly effective advertising and propaganda, were all over the map both in intensity and in direction. Universal health insurance, estate tax, Iraq, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and Sarah Palin caused much of the country to have strong and conflicting emotions. These emotions continue, perhaps egged on by the media. The 2012 election will undoubtedly be worse. The United States seems to be deadlocked, partly because issues are complicated. Although some people claim to simply not care about such issues, they can usually be goaded into taking a stand.

Humans also carry conflicting emotions within themselves. For example, the love-hate relationship is often encountered. In Mr. Plutchik’s model, acceptance is related to trust and annoyance to anger. But we often accept annoyances because the cost of doing something about them is greater than the gain. At the time of this writing, when traveling internationally one often finds people who feel both positively and negatively about the United States. Not too long ago I was undergoing rehabilitation from bilateral knee replacement surgery. When my physical therapist was wrenching upon my new knees seeking more motion, I was overwhelmed by conflicting emotions. I was extremely happy I had had the surgery, but much less happy about the wrenching. I am also happy to be retired but occasionally miss the self-inflicted angst of the university. I love my word-processing software when it points out embarrassing spelling errors, but I hate it when it wants to help me organize my text.

This diversity of emotional response between and within people, whether they are individuals, groups, or nations and religions, makes it difficult to generalize about emotional response—it is a personal thing. Many people share my love of old machinery. Many more think those of us who have it are nuts. Some people spend great amounts of time playing golf. I think they are nuts. That’s the glory of the human condition—to each his or her own. But this diversity makes it difficult to build a product that satisfies everyone, which is probably why companies who try to do so eventually run into trouble, and why I hold out for more product diversification.

Emotion is also extremely complex considering what is known about the mechanisms involved. When I went to school, we were taught that the cortex analyzes signals from the senses and triggers appropriate responses. For instance, you are awakened at night by a strange sound in the house and your cognitive machinery analyzes what it might be. If the conclusion is that it is a prowler, you become frightened. This mode was convenient and cognition-centered. Over the years, however, powerful scanning techniques have been developed to trace the activity in various parts of the brain. It is now thought that signals from the senses go both to the cortex (thinking) and to the amygdala and hippocampus. The latter two subsystems of the brain contain some basic memory of sensory signals that connote danger, and if the new signal matches one of these memories, we become frightened before the cortex can analyze the data.

The hypothalamus starts the flight-or-fight response, with heart rate and blood pressure increasing, circulation increasing in large muscles and away from the gut, and breathing slowing. The cingulate cortex tones the large muscles, freezes unrelated movements, and causes our face to assume a fearful expression. The locus coeruleus releases norepinephrine, focusing our attention and prioritizing our knowledge and memories. This whole process is automatic. Later, when the cortex reaches its conclusion, it may turn all of these functions off if the noise is simply the cat. Alternatively, the cortex’s conclusion may reinforce the response. The important point is that emotions lead, rather than follow. This sequence helps explain, for instance, why we often form such a strong first impression of a person, even though subsequent experience may slowly teach us that we were wrong. These same emotions play a strong role in dealing with products.

Emotions also vary a great deal in rapidity of response. People may fall in love almost at first sight or over a long acquaintance—this is true of products as well. We may fall in love with products instantly (the iPhone) or slowly (the hybrid car). Of course, people may also fall out of love over time. We may dislike a person or product on first meeting and later become very fond of that person or product (for example, a new and complicated software program). We may become frightened because a loud noise awakens us at night, but we may also become frightened or anxious because the media tells us of weaknesses in the economy week after week. In some cases our emotions are triggered rapidly by a sensed event, and at other times they are triggered slowly by signals received by our senses and processed by our brain over a long time. Some people who study emotions view them as an alarm system—rapid automatic mechanisms that initiate appropriate actions based either on built-in or learned survival needs. When the bear appears in your campsite, for example, your emotions shut off your daydream and start you on appropriate actions. Others are more biased toward cognition and feel that emotions respond more to past experiences, triggered by information gathered over time.

Many theories of emotion classify some emotions as basic, meaning they are necessary for survival and, to some extent, shared among other animals (assuming you are willing to believe that animals other than humans have emotions: dogs, sure, but chickens?). The previously mentioned basic emotions of Plutchik (joy, trust, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation) are typical. Sensory signals announcing danger, hunger, thirst, or worrisome body conditions cause emotions that galvanize the individual into solving the problem. Other basic emotions would be those useful in preparing for the future and living with members of our species in stable packs, tribes, or cultures. Emotions that support increasing the gene pool are obviously essential to the survival of a species.

But not all of our emotions have to do with survival and increasing the gene pool. In an interesting book entitled How Pleasure Works, subtitled The New Science of Why We Like What We Like, by Paul Bloom, son of the previously mentioned Benjamin Bloom, the author looks at pleasure from an essentialist view-point.7 Essentialism is a school of thought in cognitive psychology that says people naturally assume that inanimate and living things and people have deep but invisible essences that define them. In the case of products, this might include such things as association with admired or hated people, history, association with different cultures, and strongly held beliefs about quality. The advertising industry makes good use of such things to influence the attitudes of potential customers about products. Tests discussed in Bloom’s book have shown that after you choose a product you like it more and the competitors less, and the longer you have owned it the more you like it.

In his book, Bloom mentions many things of little use that apparently have great value, including a tape measure from the household of John F. Kennedy that sold at auction for $48,875 and the sock from the foot of a photographer that was run over by Britney Spears’s car, which was successfully sold on e-Bay. He also discusses the importance of the people or companies that produce the product and the role of imagination, which allows us to build scenarios before acquiring products (which may later turn out to be false) and come to believe that a product we own is superior to identical ones we don’t own.

I am not going to attempt to write about the feelings associated with various emotions here. The greatest artists in history have tried to trigger these feelings in others, but probably experiencing the emotions oneself (falling in love, for example) is more vivid to most people than the feelings evoked by poetry, prose, a painting, or a sonata. Since I am not one of the greatest writers in history, I must be satisfied with strongly encouraging producers to become more interested in and sensitive to emotions and feelings in themselves, consumers, and, for that matter, everyone else. It is a fascinating area for thought and observation. For the purpose of this chapter, I will assume that there is commonality between people as far as the feelings resulting from emotions, although, again, there is not nearly as much commonality in what triggers these emotions or how intense they are.

An increasing number of product designers and others associated with producing industrial products are thinking more deeply about people’s needs. In a sense, marketing is based on the past experience of people and seeks the improvement of existing products. Studying the people’s needs offers the potential of a clearer look at the future, since products are perhaps more fleeting than human needs. Also, it is likely that if products help satisfy human needs, people will be pleased and sales will be good. Products that hinder satisfying these needs tend to be considered bad and do not sell as well. Should a product help us in satisfying a need, we are enthusiastic, perhaps even in love with it. Should it fail to help us satisfy a need or, even worse, hamper our effort to do so, we are frustrated and annoyed. And we may hate it.

There are many ways to classify needs in order to think more clearly about them. One of the most well-known classifications is the venerable one proposed by Abraham Maslow in a paper entitled “A Theory of Human Motivation” in 1943. In this theory, he defines a hierarchy of what he considers basic human needs, in that all humans share them.8 The theory remains popular so many years later because it is relatively simple and of high practicality, outlining a set of human needs and hypothesizing that if these needs are not satisfied, humans will be motivated to satisfy them. The theory is hierarchical in nature and is often depicted as a pyramid with our physical needs (breathing, water, food, shelter, sex, homeostasis, sleep) at the bottom. If these physical needs are not fulfilled, we first focus upon them.

Once our physical needs are somewhat (not absolutely) taken care of, we consider our safety needs (security of health, employment, resources, family, property), the next layer in the hierarchy. Having satisfied these to some extent we work on our belonging needs (friendship, intimacy, family). Next in line are esteem needs (achievement, respect by others, self-esteem, respect for others). Finally, we reach the self-actualization needs (creativity, morality, acquisition of knowledge, spontaneity, problem solving, lack of prejudice, and acceptance of facts).

But as is the case with many (most?) theories of motivation and behavior, there is disagreement with Maslow in the literature by others who, while not disagreeing with his needs, have found no evidence that they are hierarchical—in other words, if our physiological, safety, love/belonging, and esteem needs are satisfied but our self-actualization needs are not, we still will not be happy campers. We need to satisfy all of them.

Also, times have changed since 1943. Maslow’s list of needs now appear to be somewhat naive. Since 1943, the world’s population has grown from 2.3 billion to 7 billion, the U.S. population from 136 million to 310 million, and the population of Los Angeles County from 2.8 million to 10 million. People in the United States are much more aware of the rest of the world because of modern communication and have become much more cynical (and more mature?) about the direction our society is taking. I clearly remember 1943, when Maslow wrote his paper, because I was nine years old and World War II was going on, something of great interest to a nine-year-old boy. I listened to the radio news, watched the newsreels in the movie theater, and read the newspaper. But unknown to me, and to most other people, the news was being carefully managed with the cooperation of the media. There was no TV, nuclear weapons had not yet appeared, and as far as we knew everyone was cooperating in a great cause to save the world. Because of such things as the Cold War, Korean War, Vietnam War, vastly improved communication, and increased awareness of issues like genocide and destruction of the eco-sphere, life now seems more complicated. Because of the increased population, it probably is more complicated. Contrast the presidential campaign of 1944 with that of 2012, which at the time of this writing seems more like a carnival than a campaign.

A somewhat more contemporary look at needs is that by Len Doyal and Ian Gough, first published in 1991 in a book entitled A Theory of Human Need.9 Their approach is often quoted in work having to do with conflict resolution and is somewhat broader than that of Maslow. They feel that the most basic needs are physical health, individual autonomy, and ability to criticize and try to change the culture in which one lives. They discuss a number of what they call intermediate needs, or satisfiers. These needs are the most basic but can be satisfied in various ways. They include the following:

• Nutritional food and clean water

• Protective housing

• A nonhazardous work environment

• A nonhazardous physical environment

• Safe birth control and childbearing

• Appropriate health care

• A secure childhood

• Significant primary relationships

• Physical security

• Economic security

• Appropriate education

The first six of these needs contribute to physical health, and the last five to autonomy. The authors point out that this list and methods of fulfilling these needs change continually over time. They further maintain that there must be certain prerequisites in a society before it is possible for people to fulfill their needs, including production, reproduction, cultural knowledge, civil/political rights, ability to access the intermediate and satisfier needs, and political participation.

The Doyal/Gough approach gives more attention to societies and cultures than Maslow’s does and specifically lists items such as birth control, work environment, and health care. Both lists are a bit high-minded considering the way the human race behaves. Neither of them lists justice (being treated fairly) or power. Maslow lists sex (spreading the gene pool), but Doyal and Gough do not on the grounds that there are people who live happy and successful lives without it. Entertainment may fall under the same rubric, although it seems to be a fairly significant need to many people I know. These theories and many others attempt to define basic human needs, those that not only are universal but also would cause real harm if not fulfilled.

Now let me say a few things about emotional response to products and three classes of needs. I will call them survival needs social needs, and intellectual needs. Although such a simple split is not consistent with the complexity of the brain or modern neurological, anthropological, or biological studies, I will use it because it seems to have strong intuitive appeal. In Chapter 4 I mentioned Benjamin Bloom and his committee dividing learning into the psychomotor, the affective, and the cognitive. I also mentioned Paul MacLean’s division of the brain into the R complex, the limbic system, and the neocortex.

An interesting treatment of emotions as they affect the design of products can be seen in Donald Norman’s book Emotional Design.10 He proposes considering design at three levels, based on how humans process information. The first, the “visceral level,” has to do with brain function that is automatic—programmed and unconscious. The second, the “behavioral level,” concerns activities in the brain that control our day-to-day activities. The third he calls the “reflective level,” which includes the contemplative activities of the brain. And finally Maslow’s needs are sometimes divided into physical, belonging and esteem, and self-actualization needs.

As humans, we have some strong needs. We are animals that have been around a long time, and like all forms of life on Earth, we are wired to survive. If something threatens this survival—for instance, if we are extremely hungry, thirsty, or starved for oxygen—we will act in extreme ways to remedy the situation. In some functions, such as our need for sleep, our body will remedy the situation even if we cognitively don’t want it to. Some of our body’s responses are automatic and involve decisions made locally that result in actions to minimize danger before we are aware of emotion (for example, we will automatically drop a hot pan or strive to get our head above water). Other situations that threaten our physical well-being result in negative and longer-term feelings such as those that result from being cold, sleep deprived, or lost.

We are uncomfortable if our sensory signals are impeded. I have spent time in sensory deprivation chambers. It did not take long for me to tire of listening to my heart beat and my blood flow and to want out. If you have ever tried to cover the eyes of a dog or cat, you realize that we mammals have a basic and understandable need for information from our senses. Since we are also uncomfortable with a sensory overload, designers of products should think hard about the proper amount and type of information available to users’ senses. This consideration sounds obvious, but it isn’t always taken into account. Think of motorcycle helmets, which help minimize brain damage in case of a fall but are often not worn because they impede vision, hearing, and feeling.

From the standpoint of product quality and survival needs, some rules are simple. Good products should never trigger those emotions associated with threats to survival unless there is a good reason to do so. In the case of entertainment, for example, fear, horror, and disgust are sometimes deliberately triggered (think of Steven King novels, computer games, and horror movies). In the case of alarm systems, primitive responses are often triggered (such as loud and disturbing sounds from fire alarms, obnoxious-smelling chemicals such as mercaptan added to naturally odorless cooking gas). But normally, we do not respond positively to feelings of impending doom. Stuffy car interiors (with their perceived lack of oxygen), appliance exteriors that burn users, and diving masks that leak do no one, producers or users, any good.

Conversely, products that make us think that our survival needs are being met make us feel good. “Comfort food” makes us happy because of the salt, sugar, fat, and carbohydrates it contains (once not only essential to humans but also difficult to find). Manufacturers of food understand this fact well, but presently they are caught in a backlash because they have gone so far in pleasing the customer that they seem to be producing food that is deleterious to consumers’ health (with hydrogenated oils, fructose sweeteners, chemicals with frightening names, and massive overdoses of calories) and obese customers. Of course, there is a large demand for foods and drinks that are presumably healthier but that satisfy these ancient needs by tricking the senses.

People in the San Francisco Bay area seem to love their household heating and air conditioning even though the climate is extremely benign. But our forebears were killed by heat and cold (as occasionally still happens), and energy is required for homeostasis. At the time of this writing, people in health clubs, riding bicycles, and otherwise getting mild exercise (once more a part of regular life) often drink far more water (once more difficult to find) than they need. In fact, college students often carry water bottles even though they are doing nothing more strenuous than sitting in class. But fresh water is important to survival. And, of course, anything that presumably attracts the opposite sex, or even makes us feel sexy, is a sure hit in the marketplace. And again, there seems to be a strong desire for products that are antidotes to our primitive needs—think of “diet” products and stimulants to keep one awake.

Humans’ survival needs have been with us a long time. Evolution being what it is, sensors and information-processing systems have changed, but we retain traces of sensory equipment that serve us just as they served our forebears. Our sense of taste detects saltiness. Our ocean-going forebears needed the proper salinity for their health, as do we. Toxins are often bitter. Sweet and sour things are often nutritious. Things that smell bad to us (excrement, rotting flesh, spoiled food) are not healthy to eat. Things that smell good (pineapples, roast turkey) often are. Successful products take account of these facts.

Since we have minds and memories, we also worry about the future, with the result that we have what Maslow called safety needs. It is easy to see this in the success of products that claim to make us safe. Security systems for homes and security software for computers are popular, and approximately half of all households in the United States contain a firearm, even though statistically the inhabitants are more likely to be shot with them than to shoot dangerous intruders.11 We insure our cars, our houses, and our lives against future uncertainty. But this area is a much trickier one than that of tending to our short-term physical needs, because although our senses reliably tell us when we are hungry, they are less reliable at telling us how secure we are. Our senses are good at telling us that our house is on fire, but not very good at giving us an indication of our risk of having a stroke, being robbed, or having our grandchildren grow up to live in a drastically degraded environment. Here the mind is involved and perhaps not very good at predicting the future.

These safety needs can also be used to influence people, as can be seen in many pharmaceutical advertising campaigns and in the mileage that politicians have gotten from the 9/11 tragedy. Products that can honestly help us to attain future security or allay fears of losing things that are critical to our happiness are popular. But most of us know people who are, in our opinion, suckers for products that promise eternal health and escape from aging and death. Products that prey upon such things as fear of death in potential customers (especially if advertised in a way that enhances the fear) may make money for the producers, but such products can hardly be called “good.” We are good enough at being fearful without outside help. We don’t need television ads portraying the horrible diseases we may acquire unless we buy the preventative being promoted.

I wish that our longer-term survival needs resulted in stronger signals and responses in certain situations. For example, we as people are facing some major long-term problems (including resource depletion, destruction to the ecosphere, population growth, religious clashes, economic disparities, and nuclear weapons) that could cause great harm to our lives or those of our children. Unless we change our present path, the odds are high that we humans will have our parade severely rained upon by such problems at some point. But we respond slowly, if at all, because we do not “feel” the sort of danger that we feel if we run out of food to eat. We are wired for short-term problems (affecting days, weeks, or a few years) rather than long-term ones (affecting tens to hundreds of years).

Social needs (friendship, intimacy, family, self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect for and by others) are also basic to humans. Often they are not considered as basic as survival needs because they are thought to be based more on learning and self-awareness and therefore less widespread in the animal kingdom. But humans are pack animals whose groups over time have increased in size from families and tribes to Rotary clubs, religious organizations, cities, states, and international communities. We need such social groups. Consider that one of the more brutal punishments humans have devised is solitary confinement.

If we have a stable, loving family and belong to groups of people that we like and respect, we are happy. If we do not maintain this stability, we are lonely, depressed, and frustrated. These latter emotions may not occur as rapidly or as strongly as the ones that accompany unfulfilled survival needs, but over a longer period they definitely reduce the quality of our lives. Products that help us belong are good, but there is a growing concern about products that seem to be pulling in other directions. For example, TV and computer games compete with activities that once involved the whole family. Fast food and frozen dinners change the character of the kitchen, a traditional crossroads in the home. Computers and digital communication equipment seem to emphasize differences in age and technical sophistication. The media, with its base in modern communication, is thought to contribute to polarization of societies. Knowledge workers in their cubicles are a far cry from construction workers in their gangs, as is the modern mechanized farmer’s family (often complete with working spouse, upscale computers, health club membership, and a full load of organized sports, music lessons, homework, and other scheduled activities for the kids) different from the traditional one. The Web is alive with social networking sites, and we have cell phones and instant messaging (both probably used for purposes more social than professional). However, our current situation means there is room for new products that encourage people to build close friendships through personal engagement in more active pursuits.

So-called esteem needs are important similarly to social needs. We realize only too well that we are one of 7 billion people and mortal. We need to think of ourselves as unique and valuable in this huge flock. We seek status and need pride. Good products should certainly honor these needs. But as we leave purely physical needs, the task of fulfilling others becomes more complex. As an example, air is necessary to breath, but achievement and respect by others depends on whose opinion is considered and what activities we value. The academic, the construction worker, the businessperson, and the professional criminal are likely to differ a great deal in this regard. The professor is not as likely to define herself by net worth and the professional criminal may not be as motivated to write scholarly articles. The construction worker may place little value in what the professor thinks of him and vice versa, but he may place great value in the opinion of his coworkers. Though some people may think Donald Trump is a jerk based on his performance on television and media appearances, he might not be interested in what they think at all.

Certain products are associated with economic success. In this category we find the “luxury” product—though what we consider luxury, of course, is dependent on how much money we have. For the wealthy, luxury products might include a gray or black top-of-the-line BMW or Mercedes, a marble fireplace in the living room of the executive home, or even the private jet and the yacht. For the economically comfortable, they may be the large-screen hi-def TV or the upscale deer rifle. For those dwelling in a Mumbai slum, any TV may qualify. Status within one’s peer group can also come from a product that performs its task extremely well. I usually find myself owning cameras and computers with far more capability than I ever use. I clearly don’t need them, but I am a techie and a sucker for highly sophisticated technical products. Is status among my peers part of this? I certainly wouldn’t admit it, but I’m sure my wife might suspect such a motivation of me. In most cases, people take pride in products of technology that they consider the best they can afford.

But there are traps in the luxury product. The desire to “keep up with the Joneses” may be a short-term economic boon for producers, but for purchasers it can be self-defeating. There is less pleasure in the marble fireplace, the Lamborghini, and the 8,000-square-foot house if it is based on comparison with neighbors who have as good as, or even more exotic, fireplaces, cars, and houses. Fulfilling esteem needs by considering ourselves better than others is doomed in the long run. Remember the French Revolution: it is safe to say that the reigning aristocrats behaved in a manner that implied they considered themselves superior to the bourgeoisie. The result was the guillotine.

Even in the United States, there are waves of reaction against overly conspicuous consumption and runaway materialism. Such a wave certainly occurred in the late 1960s and early 1970s and reemerged after the Wall Street debacle of 2008. Consider the contemporary electronic or computer business and industry, in which your status is highest if you both are successful and retain the values of the tribe. Respect now comes from other accomplishments rather than from piling up cash through exotic financial instruments. Bill Hewlett and David Packard (known as Bill and Dave) did not have luxurious office suites, and in fact Bill Hewlett was often found in the cafeteria or “managing by walking around.” Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs are still remembered fondly from start-up days, and Jobs was usually seen wearing jeans. Bill Gates, who raised eyebrows by building a huge and luxurious house, is more highly thought of these days because his foundation is doing such good work with his money.

Industrial products can definitely help fulfill confidence and achievement needs. When Howard Head introduced tennis rackets with a larger “sweet spot,” he instantly increased the ability of amateur tennis players who acquired them. Certainly Adobe Photoshop and other computer-based graphics programs have increased the ability of people like me to handle visual material. Along with increased ability comes increased confidence. In fact, in this day and age increased understanding of, and ability with, digital devices seems to add to both confidence and achievement. I am not sure the computer has made a better writer out of me, but I can sure move text around more rapidly. Also my confidence is buoyed up when I can solve my wife’s system problems, because she is impressed (it is good to be complimented on your abilities by a spouse). But again, as mentioned earlier, traps exist. You can suffer a decrease of both confidence and achievement by being a prisoner of computer systems that constantly leave you frustrated and having to call either the help line or the IT person. The same is true of playing tennis with a crummy racket.

When I talk about intellectual needs—which include creativity, morality, acquisition of knowledge, spontaneity, problem solving, lack of prejudice, acceptance of facts—I focus much more on Homo sapiens than other species since these needs stem from the human mind. Thought, enlightenment, and success are all necessary to our existence. You could argue that such needs require transportation, good audio equipment, and fast computers for fulfillment, but when I think of self-actualization needs these days, I think of “software”—of information and education. This thought is perhaps my bias as an academic, but it seems as though there should be much higher-quality material to allow learning and self-knowledge.

It would be nice if the order of magnitude of money and talent that goes into the production and sale of video or computer games could be invested in educational material for all ages. There are good education programs on videos and on TV, and a plentitude of resources available through the media (the Internet, films, painting, sculpture, facts, articles, and books galore), but relatively little has been done in presenting this material in a new and stimulating way to the general public. There are both public and private university programs that utilize TV and the Internet (the British Open University being an outstanding example), but the best ones tend to use a course format and require a good bit of motivation, commitment, and sometimes cash to access them. I sometimes fantasize about high-quality and creative presentations of educational material available to everyone at no cost to help them in fulfilling their needs to learn and to create.

For me, thinking of the needs of humans is an excellent way to think about products and what emotions are likely to result from the use of them. I think the topics in this book are needs—the needs for good deals, human fit, craftsmanship, beauty, cultural identity, and a clean environment—and that satisfying them makes us feel good. Other needs (such as the need for entertainment, control of our lives, making things, using our bodies, novelty, caring for others, free time) can be tucked in a hierarchy or not, but almost any need can catalyze one’s thinking and be reframed to think of products that might satisfy it and, in the process, result in positive emotions. It is therefore possible to connect the satisfying of human needs directly to business through design.

The pursuit of greater understanding of the needs of people, in general, and customers, in particular, is attracting more attention in design. The social sciences have developed powerful methods of qualitative understanding of societies. They have been moving toward the natural sciences in rigor and repeatability. Processes of observing and recording data, without influencing those being studied, is increasingly useful in seeking to define human behavior in societies in a way that sheds light on the needs of individuals in those societies that will be useful to the designers of products. Two pioneers in this field, Bob McKim and Rolf Faste, were members of the Stanford Engineering School faculty, and a good bit of this “need finding” mentality can be seen in graduates of the Stanford Design Program.

An interesting and reasonably sophisticated categorization of needs from a designer’s viewpoint is contained in an article by Stanford design graduate Dev Patnaik. He is the cofounder of Jump Associates, a product strategy consulting group based in San Mateo, California, and New York City, and presently teaches the course on need finding in the Engineering School at Stanford. His system breaks needs into four categories based on immediacy and universality.12 The intention of his system is to help the clients of his company not only better understand the needs of their customers but also use this information to help the clients with product planning.

The most immediate and most easily satisfiable category of needs in Patnaik’s system includes the needs of people in a particular group that want to do the same things in the same way—perhaps Stanford students who need an easier way to fasten their bicycles to existing racks so they won’t be taken by other people. These needs can often be satisfied with an improvement to an existing product (what Patnaik calls a “new feature” solution).

His next category of needs are those of people in a particular group who want to do the same thing, only perhaps in different ways—Stanford students who want to keep their bicycles from being taken by other people. Even though these students may see their need in terms of past tradition—locking their bicycles to racks—their need is actually much broader and encourages a wider variety of solutions—use a beacon, paint the bicycle to look ugly, and so on. In fact, the need as seen by the customer can disappear if other means to the end are taken, such as riding the campus shuttle buses. Obviously, since these students do not especially want to do things the same way, as is the case with the first group, there is more room for creativity and innovation in satisfying their needs. Satisfying these needs may be more difficult, however, not only requiring more creativity and change but also perhaps moving designers and the company into a wider area of competition and new concepts.

The third category consists of needs of people of the same age, profession, religion, or other such affinity group who do not especially want to do the same thing—for example, the need for college students to find the “right” boyfriend or girlfriend, get good grades, or look cool. Whereas the first level of needs can be solved by “features,” or improvements on a product, the second and third levels are much more open to what Patnaik calls “new offering” and “new family” solutions.

Finally, there are Patnaik’s “common” needs, which are the needs of most people—to be loved, respected, safe (Maslow again). These needs are the most general and the most difficult to satisfy, often needing what Patnaik calls larger “systemic solutions.” Common needs also encourage the broadest range of concepts and cause the company to think most deeply about its products.

Patnaik’s company combines approaches taken by product designers and social scientists not only to solve problems but also to correlate customer needs with company capability and strategy. The first level of needs can probably be solved soon and relatively cheaply, but competitors can easily follow (or even do better)—for example, by producing a better bicycle lock. The satisfaction of the second level of needs may lead the company to a more and perhaps preferable solution, often one that allows the company to vault over its competitors (for example, an alternate means of transportation). Satisfying the third level is even more difficult because these needs may have little to do with the company’s past activities (for example, moving from bicycle locks to alternate transportation to getting good grades). But looking at third-level needs may help the company to think more broadly about its customers and business and lead to something the company might have advantage on because of its experience with college bicycle riders. Finally, common needs might simply be too generic for the organization to want to deal with, but are interesting to think about in the company context for possible future directions.

Satisfying increasingly broadly defined needs may be more difficult, but it can result in a more stable business. Alternate bicycle security systems may appeal to more potential customers. Families of products offer the opportunity of attracting still more customers, building a more powerful brand, building synthesis between products, and surviving individual product failures. Systems solutions promote the sales of products that are compatible with each other and allow even more capability when combined. The product balance of any company is a critical strategic decision, and decisions on defining this balance can be aided by a good map of present and potential future customer needs considered at various levels. A company product strategy and a good knowledge of customer needs are invaluable to designers defining products for the company.

Chapter 6 Thought Problem

Choose two products that fulfill your needs and please you emotionally and two that do neither. Do not feel restricted to products you own, although obviously you need to be familiar with them. Why do you consider each successful or not as far as emotions and needs are concerned? See if you can get into an argument with someone who feels differently about them. Why the difference?