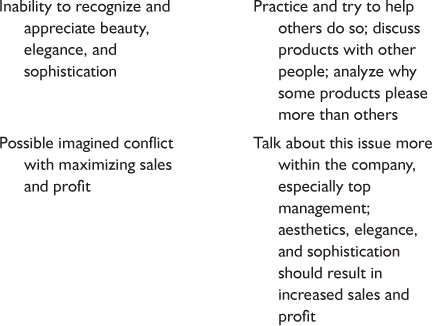

Problems and Tactics Table: Aesthetics, Elegance, and Sophistication

This chapter deals with aesthetics—certain sensory signals, or combinations of them, that give humans unusual satisfaction through wonderful images, smells, sounds, feels, and tastes. The source may be a scenic view, a plant, an animal, or an object. We retain the pleasure our primitive ancestors derived from sensing aspects of nature that served them well—the sound of clear, sparkling streams, the feel of soft fur, the smell and color of ripe fruit, the look of verdant landscapes. We love to gaze at the jungle, the tall tree and the game animal, smell the flowers, and experience the first days of spring and the first rainfall of the season. We consider such sensory inputs and experiences beautiful.

We also find beauty, often long lasting, in our own human works: painting, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, dance, music, and theater. Any large museum is a demonstration of that beauty, as is any well-illustrated book about the Italian Renaissance. Much that is written about aesthetics focuses on art, which is not surprising since art focuses upon aesthetics and has always attracted highly intellectual people who are fond of thinking and writing.

We know from cave and rock paintings that art is a human activity at least 40,000 years old. We also know about the art and architecture of the Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Romans, and the exquisite siting of ruins such as Machu Picchu and Casa Grande. But how about human-made objects other than buildings and monuments? Ruins from ancient cultures show that tools, clothing, jewelry, utensils, pottery, and other products have been not only decorated but also surprisingly finely made for many thousand years. Such items were not easy to make in ancient days, so the detail and thought added beyond the purely functional is particularly noteworthy. Interestingly enough, such products are often found in the same museums as art. It is probable that the appreciation of, and need for, beauty has been with us as long as our species has existed—although in the Stone Age it is unlikely people took art history courses and bought knockoffs of Louis Vuitton bags.

But how about the products of industry? Happily, many people also find beauty in them, but there could, and should, be more. Unlike in the arts, however, there are a myriad of factors competing with aesthetic considerations in products, many of them receiving greater attention because of short-term considerations and of the particular sensitivities, or lack of same, of the people involved in designing and producing them. The majority of people involved in defining and producing these articles are not nearly as interested in aesthetics as are artists. I was told once, by a highly placed business executive, that industry was about making money, not beauty. I asked him whether making beauty was perhaps a way to make money. Already he did not like the direction of the conversation and changed the subject.

When I was an engineering major at Caltech, I spent considerable time defending myself, and my fellow students, from the stereotype that we were narrow nerds with few interests outside of science and technology. After all, we took courses in the humanities and social sciences as well. I was interested in art and thought I knew quite a bit about it, and I was a pretty fair musician. If I tried hard, I could usually convince the women I dated to admit I had some grasp of things aesthetic, but I could never escape the “for an engineer” phrase tacked to the end. After working a couple of years as an engineer surrounded by the same stereotype, I enrolled in UCLA as an art student and immediately had my eyes opened. I had never been surrounded by people who were both personally and professionally entirely committed to aesthetic considerations. I had to work hard to reach the lower rungs of the ladder, and it was obvious to me that I would never make the top. After a year, I returned to engineering due to a shortage of money, but it was probably the most valuable year I have ever spent in school. Although I did not get on a path that would lead me to being an artist, I feel that I gained a much better understanding of the world of aesthetics. Even though it took a year of hard work and long hours, the good news was that I realized I was pretty good at it, “for an engineer.”

Most people involved in the design and production of industrial products do not even spend a year becoming sensitive to, and comfortable with, aesthetic considerations. I remember hearing a talk by a famous industrial designer in which he claimed that one of his greatest problems was that people such as the top executives of a client company, members of the board, and their respective spouses would feel that their expertise in matters such as color and form was as good as, or sometimes better than, that of the highly trained and experienced designers in his firm. I felt his pain. Making good aesthetic decisions in the process of designing and manufacturing products requires training, experience, and sensitivity. The implementation of these decisions requires battling influential people who seem to consider themselves experts in aesthetics. What is the answer to this problem? Managers and engineers in companies must become more sensitive to aesthetic concerns.

There are many factors involved in the aesthetics of an industrial product—line, form, color, texture, weight, as well as those more unique to industry such as use of fasteners, handling of joints, and results of manufacturing (for example, draft and flashing from casting or weld beads). There are various principles of design used in art. Painters are concerned with scale, proportion, balance, unity, emphasis, contrast, rhythm, and variety. Sculptors worry about whether their work appears interesting and three-dimensional from any viewpoint (articulation). Such things may or may not apply to the design of a product, but the designer should certainly keep them in mind as all of them trigger emotional response and are an interesting checklist when thinking about appearance. Of course, aesthetic considerations are not limited to appearance, so feel, smell, sound, and in the case of food products, taste, are equally important considerations with their own elements and principles. Many of these aesthetics can be applied to industrial products.

As far as aesthetic considerations are concerned, however, product designers are more constrained than artists are. Artists, assuming they are able to earn an adequate income, are free to express themselves as they desire. Should they be independently wealthy and of high confidence, they can spend their lives producing works that are unappreciated by others. This is not the case of product designers who are limited to what can be manufactured and what can be sold. While commercial artists, who are necessarily customer oriented, are looked down upon by studio artists, product designers who do not have a good sense of the market are looked down upon by business.

Organizations’ product designers work under constraints from marketing, the product sector the firm occupies, the traditions of the organization, and the opinions of everyone from the chairman of the board to the workers on the production line. Rather than sell their final work, they must sell their initial concept, in which it is hard to include aesthetic factors. It is easier to quantify an initial cost saving by ignoring aesthetics than a long-term profit that might result from a more beautiful product. So when companies see a potential profit problem, they tend to cut short-term costs even when that may hurt improvement of the present product or the quality of the next generation of products. Although consulting designers are usually hired to augment the abilities within a company, they too are constrained by those who hire them. While most artists operate as individuals and are constrained mainly by their artistic abilities and their capability to raise sufficient funding, most designers of products are influenced by the culture and constraints of an organization and the society in which they operate.

Constraints on product designers also occur because products tend to lose diversity over time. Before the Industrial Revolution and mass manufacturing, individually made products revealed much more of the maker and offered the purchaser the opportunity to select something that would resonate with his or her own values. This diversity is certainly still the case with contemporary products exhibiting rough craftsmanship and free craftsmanship (as discussed in Chapter 5). If you want a split-rail fence for your maple sugar farm in New Hampshire, you know that if you select a fence maker based on the maker’s past production, you will end up with something that pleases you. If you buy a piece of handmade furniture, you know that no other piece of furniture will be quite the same and that it reflects both the taste of the maker and your own taste. You can have as much choice of products as you do of individual makers, but the number of industries producing a given product tends to decrease over time.

New technologies are often accompanied by an explosion of small companies applying them to products. As time goes on, some companies flourish, absorbing others and growing, and others die. Eventually only a few may exist. In 1908, there were 253 U.S. companies that manufactured automobiles in the United States. By 1929, there were 44.1 Now there are three big ones and a few small ones. If you go to a show of “brass” cars (cars with brass fittings made in the early 20th century), there is great aesthetic diversity due to the large number of manufacturers and the fact that more components are exposed, rather than being enclosed in a sleek body. If you look at a parking lot these days, automobiles have converged to a few basic models. As the number of companies producing a particular product shrinks, and as the remaining companies grow, there is an obvious incentive on the part of the remaining companies to produce products that please an increasingly large number of people. This aim to please places increasingly severe constraint upon the product designer. A product that is “acceptable to everyone” may be boring for one individual.

Producing industrial products is also complicated by the necessity to be aware of, and react to, changes in technology and in fad and fashion, either of which can obsolete a product, sometimes rapidly. Fad and fashion are a bit more insidious, especially in the area of consumer products, because people in industry tend to forget how fickle people are. We humans like comfortable change. If the change is too abrupt we are uncomfortable with it, but if there is no change, we become bored. Just as our senses are most sensitive to changing inputs, we are excited by the new and different. We also like to be associated with a peer group that we admire and to which we belong. One way that we can comfortably accommodate to change is if our peer group, culture, or society changes with us. Whatever is presently “in” is called fashionable—but fashion changes.

Consumer products are subject to change, whether clothes, cars, food, or whatever. Around Stanford it is now fashionable to drive a Prius, wear black clothes, and shop at the farmer’s market—not a very pleasing development to Chrysler, makers of tartan plaids, or Safeway stores. The manufacturers of these “in” items will change, but so will the culture of the area. Producers of products are aware of this fact and place great effort into trying to predict change and, as far as possible, to influence the future through good advertising and market research. But the future will continue to be uncertain with changing fads. I looked through some old photographs that included me at different times and was reminded that I had worn Levi pants with three-inch cuffs, suede shoes, charcoal and pink shirts, mirrored Ray-Bans, and bell-bottomed pants at various times in my life (not all at once). I was also reminded that automobiles used to be lowered in the back rather than in the front. Fads can be seen clearly in diets and physical exercise, too. Carbohydrates and margarine were in a few years ago and are now out, and the convenient availability of tennis courts on the Stanford campus is a remnant of a short-lived tennis fad.

If you come across an old wheel lock rifle or a 19th-century steam engine in a museum, you will probably notice that significant effort was spent on these products for reasons beyond their ability to perform their job. They are often impressively decorated with graphics, inlay, intricate castings, and polished metals. It doesn’t take a student of design to realize that something has changed in product design and development since that time, because such objects are now in the province of collectors rather than being available on the market. There is a definite machine aesthetic that has evolved throughout the world. To oversimplify a complicated story, the world fell in love with machinery, industry discovered ways to decrease the cost of machinery by simplifying forms and materials, and, at the same time, a sizeable number of strong and influential people aesthetically rationalized the result.

One of the first major figures in industrial design was Peter Behrens, who was initially hired by a large German electrical company (AEG) as “artistic adviser” and was committed to integrate art with mass production. He designed products that applied the cerebral concepts of German Modernism to AEG products, developed consistent company graphics, designed a modernistic factory featuring concrete and exposed steel, and was a founding member of the German Werkbund (1907–1934, reestablished in 1950), a national designer’s organization formed to help Germany’s economic competitiveness. The Werkbund became an influential forum for discussing issues such as the role of craftsmanship in industry, the role of beauty in commonplace objects, and to what extent forms could and should be determined by function.

One of the better-known institutions dedicated to this design approach was the Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius (another Werkbund founder) and begun in 1919 in Weimar, Germany. The Bauhaus included on its faculty such influential people as Behrens, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy, Wassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, and Paul Klee. At the time of its establishment, German Modernism was strongly influencing German art, and the institution saw its mission as not only supporting this philosophy but also carrying it beyond the arts to fields such as architecture and industrial product design. Eventually the resulting emphasis on simplified, rationally and functionally determined forms unburdened by ornamentation and the reconciliation of art and industry were carried throughout the world and were to greatly affect design. In architecture these ideas gave birth to the severe forms of the so-called international style, and in product design they gave birth to many aesthetic values that were to define industrial design up to and including the present.

Although the concept of allowing form to be dictated by function was not originated by the Bauhaus, it was certainly emphasized in its teachings. The concept was also exported through staff and students of the Bauhaus who either were citizens of other countries or immigrated to them. In the 1920s and 1930s, the profession of industrial design came of age in the United States, led by people such as Henry Dreyfuss, Raymond Loewy, and Walter Dorwin Teague, all of whom had been influenced by this approach. They tended to have backgrounds in fields where visual aesthetics were important (stage design, architecture) and were equipped with personalities that allowed them to mix easily with managers of manufacturing enterprises. They were to set up large consulting offices and acquire the responsibility for the design of many products produced in great numbers by the influential companies of the day. They capitalized on the desire of customers to have “modern” products, the need for more attention to be paid to human fit, and the clumsiness of companies of that era with aesthetic concerns.

We in the Western world (and more and more all of the world) are the inheritors of this design tradition, as can be seen from comparing modern products with those designed in the period before the Bauhaus. Decoration for decoration’s sake was to disappear, and forms were to become sleeker, simpler, and more determined by function. However, there is a downside to this extreme emphasis on technical function. Think of computers, automobiles, and kitchen appliances. They are certainly simpler and more consistent with manufacturing than those of the early 20th century, and their forms have a certain sleek beauty, but are they as interesting? When I rent cars, I am always amazed at the similarity of the products of various manufacturers. How about some variety? I know a number of people who collect, restore, and drive antique cars. Modern cars are far better from a performance standpoint. But there was something going on aesthetically in the older cars that is appealing to us moderns, and there is something satisfying now about driving a car that has some uniqueness. I have a 1910 steam tractor in my backyard and a late-19th-century pedal-powered jigsaw in my living room, and they are both wonderful collections of swirling castings, gears, pulleys, belts, and other machine elements, and in the case of the steam engine, pipes and valves. They are the antithesis of Bauhaus design, but visitors always want to play with them rather than with our modern cars.

Product simplification and design standardization even sometimes cause similarities between very different products because of the role of fads and fashions in design. In the 1930s, there was a great love affair with streamlining, at that time a teardrop shape that moved through air or water with little drag. This form showed up not only on airplanes and high-speed cars but also on many consumer goods. Looking at books on the history of design, it is difficult to avoid a pencil sharpener designed in the Loewy office that looks like it could move through the air at a very high speed. Nineteen fifties appliances were well known for their color palette, with avocado green one of the most popular. At the same time, automobiles went first to two-tone and then to three, sometimes explained as a release from wartime olive drab. Now there are a few standard colors on vehicles, and the same on appliances—no three-tone or avocado. The same is true of digital electronic devices. Washers and dryers tend to look the same and refrigerators, stoves, and dishwashers have a family resemblance even though their functions are different. When traveling, the problem of identifying your bag on the carousel is increased by the fact that the vast majority of suitcases are black and similarly shaped. Parties of designers feature people in black clothing, just as the streets of financial sections of cities are filled with black raincoats during wet weather.

An assignment that I often used to give students required them to go buy two of some low-cost product and improve the aesthetics of one according to some criteria. They would then bring both the original and the improved versions to class and we would discuss the results. Engineering students would typically improve their product by eliminating details that had nothing to do with technical function, simplifying the form, removing paints and platings that masked the identity of the materials, and polishing the overall result. Occasionally a student, usually majoring in the visual arts, would modify the product by adding details and surface treatments and changing the form to be more interesting in its own right. Such changes caused consternation on the part of the other students, who were not only unable to easily evaluate the result but also not sure that it was acceptable. This situation was particularly confusing if the students were attracted to the modified product even though the modifications were not consistent with technical function. A more personal example is that my wife loves our sleekly modernist Saarinen table and “egg” chairs. But she also likes her more garish bottle opener that features the Stanford University Band playing “All Right Now” when the opener is used.

It is easy to do a bad job of modernist design, but difficult to do a good one. You must evoke the hoped-for emotional response with a minimalist approach. Simple forms can be clumsy and uninteresting. Surface finish is critical in such designs because of their scarcity of detail. A box with square corners, for example, can be pretty boring. If the corners are drastically rounded, however, the box may turn into a lump. So what is the best radius for a corner? People respond strongly to color, and as you know from selecting colors on your computer, there are a lot of them. By varying hue, value, and chroma, you can produce what seems like an infinite number of colors. So how do you pick the best color? At the least, you must experiment with a large number of them, though it is even better to spend time and effort becoming more “expert” at color. And how about forms that although functional, go beyond what is necessary, such as Philippe Starck’s tarantulalike orange juicer? A good solution, of course, is to find an expert to do such things. But how do you know how to pick an expert or whether to believe that expert? The only answer I know is to climb partway up the ladder oneself.

When dealing with aesthetics, especially in the world of fine arts, one comes upon words that have a particular meaning in the field being discussed. Some of these words are specific to the nature of the work, such as the Italian term chiaroscuro (modeling by use of light and dark) and painterly (referring to the way paint is applied). But others are more general, such as subtle (don’t use paint straight out of the tube), interesting (I don’t know quite what to think about it, but it may be terrific), marvelous (I like it lots), elegant, and sophisticated. Let us discuss the last two, since they not only apply to products but also imply a high level of quality.

When I was an undergraduate student at Caltech, I noticed the word elegance used a great deal. “What an elegant proof.” “What an elegant mechanism.” “What an elegant experiment.” A mathematics professor, in an informal moment, confided to us that he had chosen his career because he was addicted to elegance. What did all this mean? People would try to tell us: “Precision, neatness, and simplicity” (Webster’s Third New International Dictionary). “The most with the least.” “Technical sweetness.” We had a vague idea. But, after all, we were undergraduates and had not been admitted to the inner sanctum. Elegance, when used in a scientific or engineering context, seemed to have to do with efficiency, insight, cleanliness; with making the most with the least. An elegant mechanism was one with no extra parts, in which each piece did its job optimally. An elegant solution to a problem was both simple and ingenious. Unfortunately, since undergraduates spend their time swamped with huge quantities of relatively pedestrian problems in textbooks, we had little chance of personally coming to appreciate the beauty of doing original work really well.

At Caltech we also talked about sophistication and came up with two very different meanings. On the technical side, sophistication had to do with things that are highly complex and developed. “Modern accelerators are incredibly sophisticated compared to the first ones.” “Spacecraft are extremely sophisticated compared to automobiles.” “I enjoy teaching graduate students because they are more sophisticated.” Of course, being in college, we also were concerned with increasing our personal sophistication—another flavor of the word that seemed to have to do with reading certain books, becoming conversant with certain issues, becoming less clumsy at interacting with the opposite sex, learning to drink, and generally becoming more worldly and urbane.

Later, when I was an art student at UCLA, I once again heard the word elegance used a great deal. At times it implied simplicity, precision, and neatness, as in “What an elegant little dress,” referring to the newest, sleekest, simplest frock (an application of the principle of “the most with the least”). “What an elegant portrayal of anger” might refer to a single bold stroke of strong color in a painting. However, in art school, another definition of elegance was often used. “What an elegant use of colors” could be applied to a complex painting with a large variety of restrained hues. “What an elegant chair” might refer to one that was richly decorated. “What an elegant passage” could be a segment of music that was evocative of an 18th-century drawing room and certainly not “simple.” I also heard the word sophistication being used widely and more specifically. “That is an extraordinarily sophisticated sculpture for your level of training” or “I enjoy Rauschenberg because of his sophistication.”

The problem in verbally pinning down words having to do with aesthetics is that the language is inadequate when it comes to describing sensory experience. The words elegance and sophistication mean different things to different people and are subtly interlinked. That becomes clear if you look through dictionaries to find the formal meaning of the words, as you will find multiple meanings. Let us use the Webster’s New World College Dictionary as an example.2 (There is a colloquial meaning of elegance that we will not consider here, although I like it because elegance was one of my father’s favorite words. In this usage, elegant simply means excellent—as in “This is sure an elegant day,” or “This pie is elegant.”)

There are three main groups of words in the usual definitions of elegant. One seems to refer to people and two to products:

People

E-1 “Characterized by a sense of propriety or refinement; impressively fastidious in manners and taste.”

Products

E-2 “Dignified richness and grace; luxurious or opulent in a restrained, tasteful manner.”

E-3 “Marked by concision, incisiveness, and ingenuity; cleverly apt and simple.”

(Aha. E-2 must refer to Louis XIV chairs and E-3 to mechanisms.)

The word sophisticated continues the confusion because here again we find a single word being defined in two ways, one applying more to people and one to products.

People

S-1 “Not simple, artless, or naive. Urbane, worldly-wise, knowledgeable, perceptive, subtle.”

S-2 “Highly complex, refined, or developed, or characterized by advanced form, technique, etc. Designed for or appealing to sophisticated people.”

(Aha again. S-2 must apply to spacecraft and Rauschenberg paintings.)

Should these words apply to industrial products and the people who design them? The E-3 type of elegance is to me universal. Not only does the definition point toward economy and reliability, but I believe that everyone admires this type of elegance, whether they know why they do or not. Type E-2 elegance is a must in so-called luxury products—the Bentley, high-end home-theater components, and expensive furniture. E-2 obviously applies less in products such as motocross motorcycles, backhoes, and gopher traps. As far as sophistication is concerned, definition S-2 should apply to any complex high-performance product.

How about the people concerned with designing and producing good products? Should they be both elegant (E-1, “a sense of propriety or refinement; impressively fastidious in manners and taste”) and sophisticated (S-1, “urbane, worldly-wise, knowledgeable, perceptive, subtle”)? Some of these characteristics are universally necessary (“knowledgeable” and “perceptive”), while others are less so (“impressively fastidious in manners”). It would indeed be impressive to see a product-based organization staffed with people with all of these characteristics. In an organization that produces products intended for customers with these characteristics, the people in the organization must at least be able to understand and value all of these characteristics, even if they do not possess them.

Many areas of design include a high percentage of highly sophisticated people, and it is necessary to be somewhat sophisticated in order to interact with them in a productive manner. You do not have to be Beethoven to appreciate his quartets, but you probably have to listen to a good bit of music, and perhaps know something about music, to truly enjoy them. The people I know who are not professional musicians and love string quartet music the most are full-time professionals in fields other than music who are members of amateur string quartets. They have no intention of performing on the stage. They play for their own enjoyment and to become better able to extract pleasure from listening to professionals.

Should CEOs of companies design products as a hobby in order to become more familiar with the process and better utilize the professionals at their disposal? Unfortunately, most managers focus on short-term goals and want to please customers today, not challenge and stimulate them. Also, due to the criteria used to select and promote executives in industry, many of the most influential people in manufacturing organizations are both highly opinionated and much less sophisticated than those who actually spend their time with products. I have known of many instances where, in my humble opinion, company executives with product responsibility have given strong and poorly advised input to the design of products. In fact, I have known people with ultimate responsibility for design who, once again in my opinion, had very little in the way of design sophistication.

Products please us by satisfying certain criteria in our mind. Some of these seem innate, such as pleasure from things that are precise, neat, and simple, and therefore probably efficient and dependable. Others are learned, such as our appreciation of a fine piano, automobile, or piece of flatware. Elegance and sophistication are important to us, whether their literal meanings are confusing or not. Designers and producers must be sophisticated in design to produce elegant and sophisticated products, though I am convinced that such products are appreciated by all of us, even if we are not sophisticated about design. Sophistication in doing design requires training, exposure, and sensitivity. We are not likely to design an elegant mechanism if we do not know what we are striving for. When people ask me how one learns to design elegant and sophisticated products, my response is that they must love such products and wallow in them.

As an example of increasing appreciation of elegance and sophistication through exposure, think of music. Typically the music that appeals to younger listeners has repetitive and straightforward rhythms, harmonies, and melodies. Think of childhood standards such as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” and “Jingle Bells.” As listeners age, their tastes change. The music that attracts adolescents usually speaks to their problems and, incidentally, is happily alienating to other age groups. It is fascinating to watch subtle variations in rock music allowing high school students to refer to the “in” rock of two years ago as passé, even though it all sounds identical to older people. At a later age, although some people seem to have a universal love of music, most people somewhat specialize in that they like a particular genre (jazz, classical, rock) more than others. Although they may retain an appreciation for all types of music, they will become more deeply sophisticated in at least one genre. Those who have a special fondness for classical music will initially like Tchaikovsky, discover Dvorak, move to Beethoven and Mozart, at some point begin appreciating quartets and trios, and add Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Mahler, and more contemporary and experimental sounds. However, their tastes will also broaden. Eventually classical music buffs may increasingly turn to jazz, show tunes, folk music, maybe even back to rock. They will also reappreciate Tchaikovsky.

The same can be said for jazz fans, who after beginning with Dixieland and moving through various Latin forms, swing, bebop, and more abstract improvisational sounds may embrace classical, pop, and Dixieland again. The directions that people take as they become increasingly exposed to and knowledgeable of music are surprisingly consistent—this is why music appreciation courses are possible. This consistence is a large boon to the music business. We also have no trouble correlating these directions with increased sophistication. The same is true of the other arts. Painting begins with photographic realism, proceeds through impressionism, expressionism, abstraction, and finally perhaps an appreciation of all forms. Art history courses help the process.

The same situation is, of course, true of designers of products. Designers and users develop increasing sophistication through practice and usage. Think of bicycles. Those who love bicycles learn through exposure, knowledge, and guidance to appreciate the subtleties of construction, mechanism, balance, and handling that make up an outstanding bicycle. Good designers of bicycles, who are usually also users, are hopefully even more sophisticated.

Simple forms that have evolved through usage often become extremely elegant because the unnecessary has been stripped away over time—wooden airplane propellers are examples. They are extremely functional and technically quite sophisticated, but their form is beautiful and without distractions and awkward transitions. A well-known sculpture is Bird in Space by Constantin Brancusi and is on display at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. If you view it, you will hear other viewers remark both about its similarity to an airplane propeller blade and upon its elegance.

The same is often true of products that require close contact with people. An ax handle is one example. A simple cane is another. I have a framed toilet seat in my office, and people who have never been there often ask me why (or at least probably wonder) when first entering the room. The answer is that if we didn’t know what it was, we would have to agree that a toilet seat has an extremely elegant form—it is an exquisite collection of subtle curves and variations. Other products are elegant because of the direction design has taken in the company. Apple products are an example. Fashionable high-heeled shoes are another. Some products are elegant because performance requirements cause them to be so, such as the racing bicycle or the high-speed aircraft.

Abstract lines and forms can have this type of minimalist elegance independent of function. Lines with varying curvature tend to be more elegant than lines with constant curvature. Forms with slight curvature tend to be more elegant than forms with none. And then there are mechanisms. Optimally designed mechanisms for aerospace applications in which weight is critical are normally more elegant than those in agricultural applications in which it is not. Mechanisms that have fewer parts, and in which the functions and articulations are clear to the observer, tend to be more elegant than Rube Goldberg devices. Engineers, managers, and others in industry are relatively comfortable with this “most-with-the-least” type of elegance (E-3), although they may not have the sensitivity or the skills to produce it. However, they often overlook it in their eagerness to add physical function, to implement a feature cheaply, or to come up with a unique solution in a product. Devices such as the combination tool—the same ones I mentioned my mother bought me as a child—that combine a screwdriver, saw, pliers, bottle opener, scissors, and whatever else—may be useful, but they are usually not elegant, aside from the venerable Swiss Army knife, which seems to be able to combine everything up to running water in a sleek form. The same is true with most things suffering from the concept of “feature creep,” discussed in Chapter 3, in which increased function leads to a type of complexity.

In the case of a complicated system, adding elegant components can decrease the elegance of the whole. I remember one great argument from my past over the use of localized damping to solve a structural dynamic problem. The situation had to do with a spacecraft that was being developed on a tight schedule (planets do not wait for you) and with extremely specific weight constraints. Rocket launches subject the payload to very high vibration levels. When the prototype spacecraft was subjected to simulated launch vibration during developmental testing, a few of the components that were mounted on the basic structure bounced around unacceptably. One solution to this problem would have been to redesign, rebuild, and requalify the structure, but there was not adequate time to do so.

The solution that was proposed was not to change the structure but rather to attach lightweight dampers between the main spacecraft structure and the pertinent components. To the engineers responsible for the bouncing components (I was one), this was an elegant solution because the problem was solved within minimal time and cost. To the structural engineers, it was a most inelegant solution, because the structure alone should have been able to handle the problem without the addition of these extraneous parts. In the engineering world, fixes such as this are sometimes disapprovingly referred to as “Band-Aids” or “kluges,” and they are seen by those responsible for getting a product to work as efficient and clever, but by others as a testimony to a lousy design: efficient to some but not to others—elegance to some and ugliness to others.

Elegance of an initially complex product usually improves as it goes through various iterations to increase ease of use and reliability and decrease cost. An obvious demonstration of this progression is in the human interface of software. I have been writing these chapters with the help of Microsoft Word, a widely used word-processing program. I have been using Word through many editions, both for PCs and Macs, and in each release, many features are better designed than in the previous. For instance, this current release has more screen icons for commonly used commands, allowing me to escape iterating back through the menu commands. But unfortunately, this increasing simplicity of use (user-friendliness) is sometimes obscured by the provision of additional capability, and this, as I just mentioned, is a legitimate concern. Most of my friends do not need the additional options contained in word-processing programs and occasionally yearn for a simpler program. In fact, several of them refuse to move from very early releases for this reason. However, even they realize that this software is commonly used throughout many professions and that many users find the increased capability highly valuable.

The trade-off between elegance and complexity in cases such as Microsoft Word is a difficult one, since, as I previously mentioned, we all seem to like features and capability that we do not use, even though it may complicate the product. For example, I have a Canon PowerShot camera and a Nikon single-lens reflex (SLR) camera. Which is the more elegant? For taking snapshots, the PowerShot would get my vote. However, the Nikon has many more capabilities (it lets me take pictures fully automatically or manually control combinations of speed, aperture, and focus, carries a wide variety of lenses, and offers the convenience of through-the-lens viewing). The Nikon is more flexible and capable of taking excellent pictures in situations where the PowerShot would have trouble. Unfortunately, I use the Nikon camera so seldom that I often have to relearn what some of its functions do and therefore tend to lose sight of how well it does its complicated job. Both cameras are elegant for their particular purpose. I also have an old Pentax film camera—an SLR I used years ago. Occasionally I take shots with it for old time’s sake and must admit I love it a lot. That feeling is obviously an emotional response stemming from my long acquaintance with the camera and the fact that I used it when I was a much more serious photographer. I can apply the word elegance to the Pentax in its art-school meaning—evoking past glories, even though they were mine.

Looking at the history of product design, it is clear that the development of the machine aesthetic in this century has simplified life for those who create the products of industry. Most people in industry are more comfortable with function than what is now called decoration, and the rules of “modernism” are now well known. Through most of history, products have included some details purely for aesthetic pleasure. But now the word decoration has become an almost pejorative term, referring to modifications of form and surface treatments that are added to a product for aesthetic reasons but that do not improve the function. Are such things bad? Not if they do not impede function and if function is defined broadly, including bringing the user emotional pleasure and cultural satisfaction. For example, a more interesting shape for the vertical fin on an airplane might make the airplane more attractive (or in the case of a fighter more vicious looking) at no cost in performance or expense.

But the machine aesthetic requires attention to detail. Surface treatments are extremely important and must be given close attention. Finishes need to have integrity to them. For example, new items trying to look old do not quite work—consider antique furniture replicas with urethane finishes and new interpretations of 1920s limousines. Old things trying to look new also miss the mark, such as the overly restored gas pumps and crank telephones found in antique shows. I am also concerned that makers of industrial products are so comfortable with what I have called the machine aesthetic that they are not experimenting with future trends. Where are our postmodernist product designs?

Many well-known designers of the past (Frank Lloyd Wright, Battista Pininfarina, Elsa Schiaparelli, Raymond Loewy) became extremely sophisticated at design and were able to influence general trends. Henry Dreyfuss, for instance, had little faith in the design sophistication of consumers or businesspeople. He believed that products should be defined by the designer, who, after all, was primarily involved in attempts to define exceptional products. His offices still depended heavily on customer and client input and relied upon a large amount of user testing during the development of a product, but he believed that products should be as sophisticated as the customer would accept in order that customers might grow to appreciate them. Often, Dreyfuss’s client companies (such as AT&T) had large market share, and the customers often did not have a lot of choice, and since Dreyfuss would typically acquire high prestige in the client company, his office had a great amount of influence.

Presently, many well-known designers (Philippe Starck, Frank Gehry, Bob Lutz, Stella McCartney, Burt Rutan, Ralph Lauren) are doing the same thing as Dreyfuss, but the situation has changed. These people can still influence companies because of their track record as visionaries and the proven demand for the products they design. Most products, however, are defined by less famous designers within a company, and marketing people and managers are highly involved in the process. Marketing has become a much stronger function and very good at ascertaining what the potential customer will buy. But just as marketing has difficulty judging response to an unprecedented product, it has trouble predicting customer reaction to radical aesthetics. Marketing approaches may win in the short term because the customer is likely to be immediately attracted to the product, but they may result in a long-term loss unless they can predict the future sophistication level of their customers and society overall.

Another concern I have is the increasing separation of those involved directly in the design and production of products and those who manage larger companies. The latter typically have backgrounds in finance, and their talents often lie in administration and organizational design and control. This experience may result in company directions that are not consistent with the processes of design and production as far as product quality is concerned. Ford did well when Donald Petersen was president. Petersen’s background is in engineering, and he rose through the company in product divisions. He is a self-defined “car guy” who was head of the successful Taurus project before he became president and initiated the successful “Quality is Job 1” campaign.

Petersen’s successors did not have as deep a background in product design and production, and Ford products seemed to languish after Petersen left the company. The same situation is true of Hewlett-Packard, a company that seems to do better at product quality and sales when headed by people who have a background in the making of good products. They lagged badly when Carly Fiorina, an impressive woman educated in the liberal arts and business and with a proven record in finance and sales, was president. Compared to most successful HP presidents, she was short in experience in the nuts and bolts of designing and producing good products. Sophistication requires that those who design and build products not only use them but also have a love for them. Boeing concluded an informal study a number of years ago to define the characteristics of their outstanding aircraft designers. It turned out that the key characteristic wasn’t education, family background, upbringing, or anything like that. Rather it was love of airplanes.

Sophistication requires hands-on exposure not only to one’s own products but also to those of one’s competitors and all closely related products. A friend of mine some years ago, on becoming CEO of a well-known and long-established maker of forklifts, found that all of the small forklifts used in the company were its own. That might seem logical were it not for the fact that the company was being badly beaten up in this niche by its competitors and benchmarking was the rage. To his credit, the new CEO soon had the plant equipped with examples of the competitors’ forklifts. He should probably have gone one step more and brought examples of other brands and related machinery into the plant. Forklift makers could probably benefit from taking apart a Volkswagen Beetle and a contemporary industrial robot as well as reverse engineering competing products. But the CEO’s attempt to increase the breadth of knowledge and experience of the company designers did not go over well with the board of directors, who were conservative long-timers convinced that the company made by far the best small forklifts in the world. (My friend is no longer with that company, and the company is no longer making small forklifts.)

Finally let me say again that I think, in general, engineering and business schools should do a better job with topics such as aesthetics, sophistication, and elegance. Students indirectly confront elegance and sophistication in Ph.D. research. By dipping their toes into the depths of intellectual specialization, they are given an opportunity to think about the difference between good research and bad. Their advisers have become appreciators of elegance and sophistication, and although they seldom directly discuss such issues, their feedback is often directed toward good methodology and insightful results. However, the poor B.S. and M.S. candidates get almost no opportunities to deal with questions having to do with good and bad. I was originally going to call the Stanford course this book draws from “The Meaning of Good” or “What Does Good Mean?” I chickened out, though, because the title would have been such a poor match for the engineering school mentality.

With some exceptions, engineering schools pay little attention to aesthetics in design, but generally focus on the engineering sciences or basic analytical techniques. As discussed in Chapter 2, students in engineering school tend to be there because of their past performance in science and math courses. Their motivation may be love of technology, but admission neither requires this love nor measures for it. As a result, many of our students are more interested in the process than the results and more interested in optimization than in the actual product.

When I was in college, most of my student colleagues were addicted to some class of product, whether cars, airplanes, audio equipment, explosives, sailboats, submarines, quarry trucks, or whatever. This is no longer necessarily the case. Some students have a product passion (more likely toward computers and bicycles than cars or airplanes). However, many simply like mathematics and science and are looking for a well-paying job leading toward management or a job in a nice place until they go to business school. Where and when are they going to learn about the value of beauty and how to create it or manage the process that creates it?

Chapter 7 Thought Problem

Three products this time!

Choose a product that you think is simply beautiful and one that you think is unbelievably repulsive. Choose a third product that you believe to be extremely elegant.

Why do you think one to be simply beautiful, one unbelievably repulsive, and one extremely elegant? Why do you think the repulsive one exists? Could it be improved? What would it take to improve it? Would it cost more? Can you think of a way to aesthetically improve the ugly one that would actually make it less costly to produce?