In She-Hulk (Vol. 1) #4, Spider-Man sues J. Jonah Jameson for libel. 1 In #6, Hank Pym is threatened with a lawsuit for injuries allegedly caused by exposure to Pym particles, including violent mood swings and cancer. 2 More generally speaking, superheroes and supervillains do all kinds of things, which, if you or I did them, would tend to land us in civil court. This chapter focuses on the implications of tort law for comic books.

A “tort” is simply a wrong that is the grounds for a civil lawsuit, as opposed to a wrong that is the grounds for a criminal lawsuit. Criminal prosecutions are brought by the state for violations of the law and if a defendant is found guilty, the state can impose fines and jail time. But in many cases, the victim of a crime can bring his own lawsuit seeking compensation for his damages. For example, if a person injures someone in a bar fight, they can be both prosecuted by the state for assault and sued by the injured party for bodily injury. This chapter focuses exclusively on the latter, civil side of the equation.

We discussed telepathy in chapters 1 and 3, but what about civil liability? When Professor X or Jean Grey read a person’s mind, are there grounds for a lawsuit based on the invasion of privacy? Similarly, many superheroes take great pains to keep their mundane identities secret. If a superhero was “outed” against his will, would he have a cause of action against the person who revealed his identity?

Both of these questions, and many more, have to do with privacy rights. 3 The Restatement (Second) of Torts describes the general principle of the right to privacy as follows:

1. One who invades the right of privacy of another is subject to liability for the resulting harm to the interests of the other.

2. The right of privacy is invaded by

a. unreasonable intrusion upon the seclusion of another…; or

b. appropriation of the other’s name or likeness…; or

c. unreasonable publicity given to the other’s private life…; or

d. publicity that unreasonably places the other in a false light before the public.… 4

So right away we see there are a number of different ways the law recognizes that privacy may be invaded. Simply prying into another’s affairs can be actionable. But so is using another person’s “name or likeness” in unauthorized ways, or publicizing the details of their private life. This is especially true when the publicity might lead to false inferences about a person.

There is an Alabama case, Phillips v. Smalley Maintenance Services, Inc., 5 which, while obviously not dealing with telepathy, contains a number of holdings that are of interest here. The court focused its analysis on the “Intrusion upon Seclusion” privacy tort, which the Restatement defines as follows: “One who intentionally intrudes, physically or otherwise, upon the solitude or seclusion of another or his private affairs or concerns, is subject to liability to the other for invasion of his privacy, if the intrusion would be highly offensive to a reasonable person.” 6 In considering that tort, the court held, first, that “acquisition of information” is not actually necessary to ground an invasion of privacy tort. Second, there can be liability even when information about the plaintiff’s private life is not communicated to a third party. Third, the “wrongful intrusion” tort does not require that the defendant be ignorant of the intrusion when it occurs. Perhaps most significantly, “One’s emotional sanctum is certainly due the same expectations of privacy as one’s physical environment.” 7

An important thing to remember here is that while superheroes may seem different from ordinary people, this may not matter in assessing their privacy rights. The offensiveness of an intrusion is judged by the standard of an ordinary, reasonable person, not a superhero. 8 Furthermore, “the intrusion must be of such a character as would shock the ordinary person to the point of emotional distress.” 9

Let us then consider the issue of telepathy. The Phillips ruling will be particularly important here. For starters, involuntary telepathic reading would certainly seem to be an “intrusion” on one’s “solitude” or “seclusion,” particularly into one’s “emotional sanctum,” and this is usually presented as “highly offensive” in most comic book stories where the issue arises. But more than that, the Phillips ruling might even apply to mere empathic gifts, where the user can determine another’s emotional state. Prying into other people’s hearts is just as problematic as prying into their thoughts. The telepath/empath does not even need to tell anyone about what he learns; the mere fact that the person who was read knows about the intrusion is enough.

Granted, some of these things will probably be important in determining damages. In the Phillips case, a woman was wrongfully terminated when she resisted the sexual advances of her boss and suffered chronic anxiety for which she underwent psychological treatment. The damages there are pretty easy to understand. But while a character who is briefly “read” by Professor X but who suffers no ill effects may be able to win a lawsuit, the character is going to need to introduce some evidence as to the nature of his injury if he wants to win more than nominal damages or an injunction against future mind reading. 10

But telepathy isn’t the only kind of privacy that comes up in comic books, and the issue of secret identities implicates a number of potential privacy torts. A superhero might be able to sue someone who is intruding into the superhero’s secret identity for invasion of privacy, if the intrusion was big enough. Merely asking about or even forcefully demanding to know a superhero’s identity would probably not “shock the ordinary person to the point of emotional distress.” However, actions like ripping off a superhero’s mask or demanding the answer at gunpoint likely would qualify, even if the superhero was impervious to bullets. 11 So might engaging in a consistent pattern of intruding into or investigating the secret identity at every opportunity in a stalker-ish way. One way to consider it is, would an ordinary, reasonable person feel coerced into giving up his or her secret identity? Given the danger posed to a superhero and his or her family by exposure, such coercion would cause severe emotional distress.

Or consider the situation in The Dark Knight, where the Joker puts pressure on Batman to reveal his true identity by threatening not only Rachel Dawes, but also random civilians. It is not hard to argue that a public figure of the sort that Batman had become in the film would reasonably feel coerced—Wayne would have revealed himself if Dent had not stepped in—by a threat like that one. So if anything, the unusual situation most superheroes find themselves in, particularly those who are more or less explicitly dedicated to public service, means the range of potential coercion adequate to ground such a tort would appear to be quite broad.

Even more, the scope of this tort is not limited to supervillains. A subplot of The Dark Knight involves a consultant threatening to go public with Batman’s real identity. While the Joker probably wouldn’t care all that much about being served with a civil lawsuit (Any volunteers for that job? No?), trying to blackmail someone like Bruce Wayne by threatening to go public is a spectacularly bad idea, even aside from the do-you-really-want-to-blackmail-Batman? bit.

Similarly, in the She-Hulk issue where Spider-Man sues J. Jonah Jameson for libel, it would have made sense to include a claim for invasion of privacy as well. Not only is it simply good sense to include as many potential claims as possible, 12 but that particular claim would probably have led to a very different outcome. In the story, Peter Parker is put on the stand because Spider-Man’s lawyer does not know that Parker is actually Spider-Man. 13 The attorney then names Parker as a codefendant in the suit against Jameson and the Daily Bugle, 14 convincing Spider-Man to settle, as there was an excellent argument that Parker was involved in the libelous conduct of the Bugle. But the invasion of privacy claim would probably have turned out differently because although Jameson had expressed a dedicated and obsessive interest in exposing Spider-Man to the world, Parker had expressed no such intention and had simply taken the kind of pictures that any public figure could expect to be taken.

All of that being the case, it is important to remember that the law makes a distinction between intruding on someone’s privacy and publicizing private information about someone’s personal life. The two are independent torts. And, unfortunately, most superheroes will likely have trouble pursuing the second one. The Restatement defines the publicity tort as follows:

One who gives publicity to a matter concerning the private life of another is subject to liability to the other for invasion of his privacy, if the matter publicized is of a kind that

a. would be highly offensive to a reasonable person, and

b. is not of legitimate concern to the public. 15

The reason for (b) is the First Amendment. A 1983 California case discussed the issue in some detail:

[T]he right to privacy is not absolute and must be balanced against the often competing constitutional right of the press to publish newsworthy matters. The First Amendment protection from tort liability is necessary if the press is to carry out its constitutional obligation to keep the public informed so that they may make intelligent decisions on matters important to a self-governing people. However, the newsworthy privilege is not without limitation. Where the publicity is so offensive as to constitute a “morbid and sensational prying into private lives for its own sake,…” it serves no legitimate public interest and is not deserving of protection. 16

Note the phrase “matters important to a self-governing people.” The courts are interested in protecting the freedom of the press, in no small part because that is viewed as an essential ingredient in a democratic society. As a result, whether or not a particular superhero can recover for someone publishing the details of his secret identity probably depends on the superhero. Bruce Wayne is a billionaire industrialist who is involved in politics through donations and fund-raising, and his secret identity as Batman might well be a “matter important to a self-governing people” about which the public should be informed. But Spider-Man’s alter ego is just a working stiff, a news photographer and, perhaps most importantly, is often written as a minor. The public probably doesn’t have as much of an interest in knowing those details. Thus, whether or not a particular masked character will be able to recover for someone publicizing his secret identity will likely be a fact-intensive analysis wherein the court would balance the First Amendment interests in freedom of the press against the privacy interests of the individual in question.

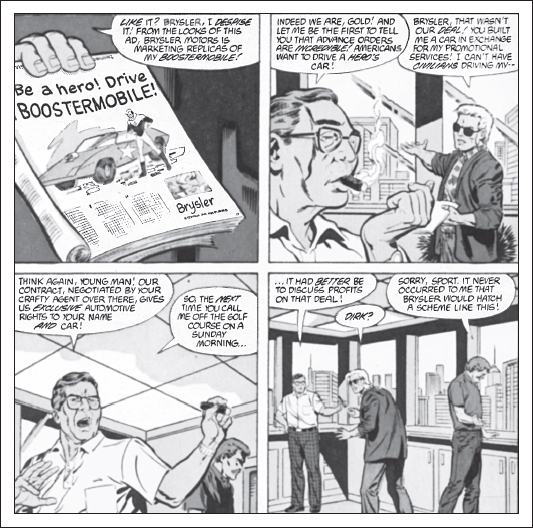

Booster Gold discovers the perils of signing over his right of publicity. Dan Jurgens et al., When Glass Houses Shatter, in BOOSTER GOLD (VOL. 1) 11 (DC Comics December 1986).

There is another kind of invasion of privacy about which superheroes might be concerned: appropriation of one’s name or likeness, particularly in the context of advertising or merchandising. The Fantastic Four actually run their own gift shop, and would probably take it quite ill if someone else started to sell goods with their names, faces, or logos. 17 And there are several examples of superheroes endorsing products (e.g., Booster Gold and the Boostermobile), so it’s important to consider what could be done about it if a false endorsement were attributed to a superhero. Here we have two distinct torts to discuss: appropriation and the right of publicity. As the Nevada Supreme Court opined:

The distinction between these two torts is the interest each seeks to protect. The appropriation tort seeks to protect an individual’s personal interest in privacy; the personal injury is measured in terms of the mental anguish that results from the appropriation of an ordinary individual’s identity. The right to publicity seeks to protect the property interest that a celebrity has in his or her name; the injury is not to personal privacy, it is the economic loss a celebrity suffers when someone else interferes with the property interest that he or she has in his or her name. We consider it critical in deciding this case that recognition be given to the difference between the personal, injured-feelings quality involved in the appropriation privacy tort and the property, commercial value quality involved in the right of publicity tort. 18

Unlike intrusion and disclosure, appropriation does not concern private facts. Instead, appropriation is defined by the Restatement thusly: “One who appropriates to his own use or benefit the name or likeness of another is subject to liability to the other for invasion of his privacy.” 19 Since private facts aren’t at issue here, this tort could apply to the appropriation of the name or likeness of the superhero identity, the secret identity, or both. Note, however, that many states have specific statutes for appropriation, and the definition given in the Restatement does not necessarily track the statutes or even state-by-state common law.

As one can probably guess, appropriation is related to the right of publicity, but it concerns different kinds of harm. One commentator puts it this way: “[A]n infringement of the right of publicity focuses upon injury to the pocketbook, while an invasion of ‘appropriation privacy’ focuses upon injury to the psyche.” 20 Note, though, that an invasion of appropriation privacy may be caused by commercial exploitation of someone’s name or likeness (and indeed many state statutes require it), but the measure of damages is still the mental anguish and physical distress caused by the appropriation.

Given the effort that many superheroes put into maintaining a sterling reputation in the community, one can see how they might suffer significant mental and physical distress upon seeing their name or likeness used without their permission, particularly if the use was unsavory (e.g., using the image of the Human Torch and his “Flame On!” catchphrase to sell cigarettes).

As mentioned, the right of publicity has more of a property right quality to it. And indeed, unlike the right of privacy, the right of publicity may be assigned or licensed to others. And this makes sense because privacy is inherently personal; it cannot really be divorced from the individual in question. The commercial use of one’s name and likeness, however, can be licensed or assigned to others, and so the right to sue for infringement of that right follows.

This is where we come back to the Fantastic Four gift shop and the Boostermobile. Superheroes, particularly well-known ones, are likely to have significant commercial value in their identity or persona. Superhero product endorsements, movie and TV appearances, and other uses are probably at least as valuable in the comic book world as the real one. Thus, the right of publicity is an extremely important one for a superhero, whether it’s used as a carrot to fund an otherwise cash-strapped superhero or as a stick to fend off inappropriate use of a superhero’s name and likeness.

But where Spider-Man can really go after Jameson is for so-called “false light” defamation. Jameson uses the Daily Bugle to paint Spider-Man as a menace to society. More generally speaking, an article on the abuse of superpowers accompanied by the picture of a superhero who either doesn’t have such powers or who has never hurt anyone would invite the public to draw an unfair inference about the person in the picture.

False light is a relatively new tort, but it has been adopted by a majority of jurisdictions. Most states have adopted the Restatement’s definition:

One who gives publicity to a matter concerning another that places the other before the public in a false light is subject to liability to the other for invasion of his privacy, if

a. the false light in which the other was placed would be highly offensive to a reasonable person, and

b. the actor had knowledge of or acted in reckless disregard as to the falsity of the publicized matter and the false light in which the other would be placed. 21

Note that many jurisdictions have held that mere negligence is sufficient if the victim is not a public figure, but in this case most superheroes are public figures, so knowledge of or reckless disregard of falsity is required. Examples of false light highly offensive to a reasonable person and potentially applicable here include drug use, teenage crime, police brutality, and organized crime. News stories or other publicity that falsely connect a superhero to such things could give rise to a false light case, and the Daily Bugle’s consistent depiction of Spider-Man as a threat to public safety almost definitely counts. This, combined with the fact that Jameson has reason to know that Spider-Man is not a menace to society and routinely and recklessly disregards that knowledge, should be enough to base a false light claim on.

Batman, Superman, Daredevil, and Spider-Man habitually patrol the streets of their respective cities, looking for crimes being committed and intervening to prevent them and apprehend the criminals. On the whole, this is a noble endeavor, but there’s a potential problem here: excessive force.

Basically, the question is whether using superpowers to prevent the commission of crimes can subject the superhero to civil liability from the criminal. The answer here is “Quite possibly.” Remember the discussion in chapter 2 of whether or not Wolverine’s claws count as a deadly weapon for the purposes of aggravated assault? This is similar, only here, the idea is that injuring someone to prevent a property crime is generally legally problematic.

This is not an idle question. In the summer of 2011, a jury in El Paso County, Colorado, awarded about $300,000 to the family of a man who was killed while attempting to rob a used car lot. 22 Robert Johnson Fox was a methamphetamine user who, along with a companion, scaled the fence to steal stereos. But the owner of the lot had already been robbed a few times that month and was waiting for them—with a semiautomatic Heckler & Koch rifle. Fox was shot through the heart and died on the scene, and the jury determined that this was a wrongful death for which the lot owner was liable. The reason this is the right result is because using deadly force to prevent property crimes is never justifiable. One is only permitted to use deadly force to prevent death or serious bodily injury to one’s self or to another, but not to protect property. Even “Make My Day” or “Castle Doctrine” laws, which permit the use of deadly force to prevent trespassing in one’s home, won’t work here, because the theory there is really that trespass to a residence always carries with it the threat of violence, particularly at night. This just isn’t true when the property in question is a business or personal property.

The parallels to Batman and other superheroes are pretty easy to see. If Superman injures a robber while preventing a bank robbery, he could actually get in big trouble. His superstrength and heat vision arguably constitute deadly force, and if the robbers weren’t using guns or otherwise posing a threat to the lives of others, this would be unjustified. Spider-Man, on the other hand, will probably have an easier time of it here, because his powers, even if he uses them, aren’t the sort that cause injury unless Spidey really goes out of his way to hurt someone. Being shot with webbing is unpleasant, but not actually harmful. Wolverine, on the other hand, had better watch his step. The fact that his claws are naturally occurring almost doesn’t matter: he has a choice whether or not to use them.

Quite a number of superheroes were not born with their superpowers, receiving them either accidentally or deliberately, somewhere along the way. 23 The Fantastic Four were bombarded with cosmic rays during a test flight. Spider-Man was bitten by a radioactive or genetically engineered spider, depending on the origin story. Bruce Banner was exposed to gamma rays during a physics experiment. The question arises, “Can these characters sue anyone for the changes to their bodies?”

The answer depends strongly on the facts of the case. Consider the case of Ben Grimm, who first appears in Fantastic Four #1. 24 Dr. Reed Richards is planning a space mission and feels a sense of urgency because the Communists are apparently on the verge of launching their own. The story was published at the height of the Cold War, and this issue came out mere months after Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to leave the earth’s atmosphere. Richards is discussing the flight with his team when the following exchange occurs:

Grimm: If you want to fly to the stars then you pilot the ship! Count me out! You know we haven’t done enough research into the effect of cosmic rays! They might kill us all out in space!

Susan Storm: Ben, we’ve got to take that chance…unless we want the Commies to beat us to it! I— I never thought that you would be a coward!

Grimm: A coward!! Nobody calls me a coward! Get the ship! I’ll fly her no matter what happens!!

Ben Grimm provides a textbook example of assumption of risk. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby et al., The Fantastic Four!, in FANTASTIC FOUR 1 (Marvel Comics November 1961).

If Grimm were then to act as a plaintiff—presumably against Reed Richards for organizing the flight without adequately researching it first—this little conversation would come back to haunt him. Why? Because assumption of risk is a defense in tort law. The basic idea is that if a plaintiff is aware of a specific risk related to a particular activity and engages in that activity anyway, a defendant would be absolved of any duty to protect the plaintiff from that particular risk. 25 This is not a blanket protection, however; the specific nature of the risk generally needs to be contemplated by the plaintiff, but in Grimm’s case, there’s a good argument to be made that he has assumed the risk of flying Richards’s ship.

First, the comic indicates that in addition to being a test pilot and thus familiar with the risks associated with piloting experimental craft, he specifically knows about the risk of cosmic rays. Granted, he did not know that they would turn him into the Thing. Everyone involved was consciously aware that they had no idea what the effects of exposure to cosmic rays might be, but they did know that death was a distinct possibility. So because there was an apprehension of some kind of serious bodily injury, up to and including death, the fact that Grimm turns into the Thing rather than receiving an ordinary injury doesn’t matter. Besides, “I’ll fly her no matter what happens,” is a pretty broad statement.

Second, both Grimm and Richards seem to possess the same mental state with respect to the risks involved. Assumption of risk will not protect a reckless defendant against a negligent plaintiff, but it may well protect a reckless defendant against a similarly reckless plaintiff. The idea here is that the law does not want to protect a party that acted with a lower degree of care over one who acted with a higher degree. When the playing field is equal, the argument that everyone involved knew the risks of the activity and voluntarily engaged in it is a lot stronger.

Third, Grimm was not a mere passenger. He was a pilot. As such, he had a significant role in the planning and execution of the test flight, and was in fact the only person even potentially capable of steering the craft out of danger. So unlike a passive participant or even someone participating in an event organized by others, Grimm had ample opportunity to mitigate the risks involved both before and during the incident. It’s even theoretically possible that the Storm siblings might have a cause of action against Richards and Grimm as the joint organizers of the project! However, neither of them seems to have been affected negatively, so their “damages” may be nominal.

Ben Grimm knew as well as anyone what he was getting into. He knew that the trip involved the risk of cosmic rays, and he knew that exposure to those rays posed a risk of serious bodily injury or death. No one seems to have known more about the risks than he did, even Richards, though that’s more a matter of shared ignorance than anything else. What Richards did was arguably incredibly foolish, but to quote a non-comic-book character for a minute, “Who’s the more foolish? The fool, or the fool who follows him?” 26

So if a character goes into a dangerous situation with full knowledge of the danger, that’s going to be a problem. But many superhero and supervillain origin stories involve situations where this doesn’t really apply. For instance, She-Hulk encounters an “accidental superpowers” situation in She-Hulk (Vol. 1) #2. Dan “Danger-Man” Jermain falls into a vat of experimental chemicals while working for the company Roxxon 27 and comes out with unspecified “atomic powers.” 28 There’s a real question as to whether or not “bodily injury” includes being made “larger, stronger, and more powerful,” 29 but more than that, the fact that the injury took place at work is significant, and not just for the question of suing over accidental superpowers. Injuries that occur while on the job are treated very differently from injuries that happen outside the workplace.

The rise of industrialization was accompanied by the rise of severe workplace injuries, as people started working around machines more often, sometimes incredibly dangerous ones. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was commonplace for factory workers to lose fingers and even whole limbs to machinery. This was hugely problematic, especially for plaintiffs, because the “master-servant” relationship required that they prove negligence or even malice on the part of the employer to be able to recover anything. This was a very high burden, and courts ruled for employers far more often than not, leaving large numbers of industrial workers injured on the job with no recovery at all. Further, even if they were eventually able to recover, tort cases routinely take years to resolve, and if the injured person was unable to work because of their injury, they could very easily find themselves in a very bad way. But legal reforms favoring labor began in the late nineteenth century, and by 1949, every state and the federal government had instituted a “workers’ compensation” regime.

Workers’ compensation operates by creating a system for compensating workers for workplace injuries regardless of fault. What this means is that if you are injured while serving your employer, you get paid the vast majority of the time, even if your employer was completely without fault. This may seem very favorable to the workers, so to even things out, i.e., to make sure that employers weren’t bankrupted every time someone broke an arm, workers’ compensation regimes were limited in three ways.

First, unlike traditional tort cases where damages are awarded by juries, which can lead to unpredictable and occasionally massive awards, compensation for workplace injuries is computed based on actuarial tables created by state agencies rather than by juries. This rationalizes and limits compensation. Whereas a jury can award a basically arbitrary amount of money, workers’ compensation payouts are known ahead of time and are thus a lot easier to plan for and insure. Second, compensation is limited to purely economic damages, i.e., medical bills, lost wages, lost future earnings, etc. There is very little provision for noneconomic damages like “pain and suffering” or punitive damages, which really drive up verdicts in traditional liability cases. Third, workers’ compensation is an exclusive remedy, i.e., employees cannot choose to forgo participation in the workers’ compensation program and sue their employers. Workers’ compensation is their only way to recover. Likewise, employers cannot decide not to pay for workers’ compensation insurance. It’s just a cost of doing business.

So employees benefit because they almost always get paid, even if the accident was their fault, and they usually get paid in a fraction of the amount of time they’d have to wait if they sued. But employers benefit because their costs are controlled and employees can’t turn around and sue them. Workers’ compensation coverage is mandatory in just about every state for just about every employee. There are, of course, certain exceptions, but a worker in an industrial plant working with radioactive materials, e.g., Dan Jermain, would definitely be covered.

So what happened to Roxxon’s workers’ compensation carrier? How is Jermain able to sue at all? Sure, She-Hulk might act as plaintiff’s counsel in the workers’ compensation case (coverage can be disputed, leading to litigation, but this is much simpler than suing in open court), but workers’ compensation is largely limited to economic damages. Danger-Man is basically uninjured, and even if we want to go with She-Hulk’s argument and say that Dan Jermain is “dead” (more on that in a minute), workers’ compensation only pays out a couple of hundred grand—at best—for wrongful death. Not $85 million, which is the settlement reached at the end of the issue.

Of course, the whole issue goes away if Jermain isn’t an employee. If the writers had him be some random schmo who happened to get in a wreck with a Roxxon tanker truck, covering him in radioactive goo, he would not be covered by the workers’ compensation regime and thus would be free to sue as he does in the comic. Oh well.

Bruce Banner’s story contains another big difference. Banner is characterized as one of the world’s most brilliant scientists, rivaling if not surpassing Reed Richards and Tony Stark. Banner is involved with a Defense Department project to develop a gamma ray bomb or “G-bomb” when he is accidentally exposed to gamma rays, which due to a fluke in his genetic structure transforms him—periodically—into the rampaging Hulk.

Sounds pretty similar to Ben Grimm, right? So far, yes. But there’s a wrinkle that makes all the difference. In the case of the Fantastic Four, just about everyone involved is acting recklessly, and no one intends for anyone to get hurt. But Banner was actually a victim of attempted murder. The way the story is told in the comics, just before the test of the G-bomb, Banner notices that a teenager has breached security and is inside the blast zone. He orders the test to be delayed and runs to get the kid out of the way. Banner is able to get the kid to a protective trench when the bomb goes off, but does not make it himself, and he is exposed to gamma rays. But the reason the bomb goes off is because Igor Drenkov, a Russian agent, orders the test to continue, hoping that Banner would die in the resulting explosion. Assumption of risk will protect a defendant against a reckless plaintiff, but it will not protect a defendant who acts with malice. Indeed, Drenkov could be subject to civil and criminal liability, as attempted murder is a serious felony.

But wait a minute…doesn’t this all happen while Banner is at work? And didn’t we just talk about how that might not work out very well for a potential plaintiff? Banner’s case is a little different from Jermain’s because Banner works for the government. First off, Banner would probably not be able to sue the government directly, as he is the organizer of the project and the government is likely not liable for the actions of enemy infiltrators. Furthermore, depending on the nature of Banner’s employment, either the Federal Employee Compensation Act (FECA), the federal equivalent of workers’ compensation, or the Veterans Affairs Administration (VA) would provide compensation for his injuries, as he sustains them while executing his duties as a government employee. So he is theoretically entitled to some money, though only in proportion to his medical bills (nonexistent) and expenses related to mitigating his disability. 30 In practice, he’s going to have trouble proving his damages, and as the FECA or VA would be an exclusive remedy, no other recovery would be available with respect to the government. He’s still free to sue Drenkov, though, because while workers’ compensation does shield employers from traditional liability, intentional tortfeasors 31 are pretty much on their own.

If there’s one thing that almost all comic books have in common, it’s that at some point there is probably going to be an absolutely insane amount of property destruction. Nitro takes out a huge chunk of Stamford, Connecticut, in the first issue of Marvel’s Civil War event, and the final battle does significant damage to downtown Manhattan. Doomsday carves a path of destruction through three states in DC’s Death of Superman story back in the early 1990s. The Incredible Hulk does a complete number on Stark Tower in World War Hulk and causes Manhattan to be evacuated, disrupting the operations of tens of thousands of businesses on the island. 32 Even something as innocuous as the Flash’s running across town can create sonic booms that leave a trail of broken windows in his wake.

Liability isn’t the only aspect of tort law. The other big part is damages. Most of the time when property is damaged, the property owner has insurance that will pay to restore the property to approximately the state it was in before the loss occurred. 33 But when the Joker blows up half of downtown Gotham just for the hell of it, insurers aren’t actually going to want to pay for that, and there is reason to believe that under the terms of standard insurance contracts, they wouldn’t have to. The reason has to do with the way insurance policies are written, which is a matter of contract as much at it is a matter of law.

Understanding this involves a little intro to insurance. Insurance, technically speaking, is a financial product whereby risk is transferred from one person, the “insured,” to another, the “insurer,” in exchange for a sum of money, called the “premium.” Insurance policies are only written for “insurable risks.” Generally speaking, an “insurable risk” is one where both the probability and magnitude of a particular kind of loss are measurable, where the occurrence of that loss is truly random, and where it is possible to transfer that risk to an insurer for an economically feasible premium. A common example of an insurable risk is one’s house burning down. We know how often houses in a particular zip code burn down, we know what a particular house is worth, houses don’t burn down at any predictable frequency, and as it turns out, it’s possible to insure against the risk of fire for a premium that is both acceptable to the insured and profitable for the insurer. Keeping track of all of those statistics and figuring out the appropriate premium for a particular risk is what actuaries do for a living. Some fun, eh?

Flooding, on the other hand, is an example of an “uninsurable” risk. Floods do occur at random, and we know basically how often, but the magnitude of losses caused by flood are such that it is impossible to offer flood insurance at any price a homeowner can afford. Floods are considered “catastrophic” losses, because they cause both a high amount of damage to individual properties but also a high amount of damage to entire regions, making it impossible to adequately spread the cost to other property owners, since they all get hit too. We’ll talk more about how uninsurable risks like flooding are covered later in this section.

The reason this is important for comic books is that the same is true of war, terrorism, civil unrest, revolution, etc. Discharge of nuclear weapons, intentional or accidental, is also uninsurable. This is starting to sound a lot like a comic book, isn’t it? And here’s the thing: uninsurable risks are generally excluded from insurance policies.

When a loss occurs, the claims adjuster is going to look to the policy to see if there’s coverage. First, he’ll look to see if there is coverage for this kind of loss on the declarations page, i.e., the coverage scheduled for this particular policy. For example, a liability policy is not going to have coverage for property losses, and vice versa. Then, he’s going to check the insuring agreement to see if the loss results from a “covered peril.” 34 Some policies cover losses from any peril that isn’t excluded, others only cover losses from a particular list of perils. Then, he’s going to check to see if there are any relevant conditions in the policy that have been breached, like failing to pay the premium or refusing to cooperate with the adjuster. Finally, he’ll see if there are any relevant exclusions, e.g., fire is generally a covered peril, but there’s no coverage if a homeowner burns down his own house.

Take the Doomsday example again, and let’s assume that he has just leveled a private residence, insured by ABC Ins. Co., by throwing Superman through it. ABC’s adjuster is first going to look at the declarations page for the insured’s homeowner’s policy. The house is insured for $100,000. So far so good. Then, he’s going to look at the insuring agreement to see if there is anything of interest there. This policy covers everything not specifically excluded, so again, so far so good. Then he’ll check conditions. The homeowner is current on his premium, gave timely notice of the claim, and is cooperating with the adjuster, so again, probably okay there.

But what’s this? The homeowner didn’t buy terrorism coverage? Hmm. That’s going to be a problem because it’s going to be pretty easy to argue that Doomsday is a terrorist. Even if he isn’t, it isn’t going to be difficult to fit this into either the war or civil unrest exclusions, both of which are part of every insurance policy. Any coverage attorney worth his salt would certainly make that argument, and it’s hard to see why it wouldn’t win. Heck, if Superman is working for the government, then it might be excluded under the “civil authority” exclusion.

In a world where central business districts are regularly leveled by marauding supervillains and the superheroes who fight them, this hardly seems like a positive result. If we’re talking about a universe where superheroes and supervillains exist and unstoppable monsters do level significant sections of town every other Tuesday, it seems probable that the legal system or insurance industry would take this into account. But because the magnitude of losses caused by superhero battles are so great, it seems likely that the states would have to resort to what are called “residual market mechanisms.”

And in fact, this is how flood insurance is currently offered on a national level: the Federal Emergency Management Agency operates the National Flood Insurance Program. This is pretty much the only way to buy flood insurance anymore. States have also set up residual markets for both high-risk drivers and properties with significant windstorm exposures (Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, etc.), earthquake exposures (California), and for high-risk drivers (every state). Basically, state legislatures have decided that even though certain kinds of risk are impossible to insure against on the open market, we want people to take those risks anyway, for a host of possible reasons. We want high-risk drivers to be insured both for their protection and for others’, and denying someone permission to drive because he cannot buy mandatory insurance seems unjust. People really want to live in earthquake- and hurricane-prone areas, and those people vote, so we’re going to find some way of making that work, no matter how silly it is.

Residual markets can work in one of a number of ways. One is “assigned risk,” an approach frequently used to ensure that high-risk drivers have access to at least the state minimum liability limits for personal auto insurance. Basically, every insurer that participates in the market is required to take its fair share of high-risk drivers as a cost of doing business in the state. It can then spread this cost to its other insurance customers, keeping the company profitable.

But it seems more likely that the states would create their own “Supervillain Pool” similar to the windstorm pools active in the Gulf and coastal states. The way windstorm pools work is that every insurance policy is assessed a tax, based on the premium, which goes into the residual pool. The pool then reimburses property owners for damages caused by hurricanes. Property owners in comic book stories would need to buy “Superhero/Supervillain Insurance” from a pool, set up for that purpose though that premium would be a good start because this truly is an uninsurable risk; the pool will probably need to be supported by taxpayer revenue as some windstorm pools are. The idea is that all but the biggest losses will be at least mostly absorbed by the pool but that the government will step in if things get really out of hand. The pool can theoretically up its rates in the years following a big loss to ensure that the government gets its money back, but this rarely happens.

In the Marvel Universe, this is basically how things work. Individuals and businesses can purchase Extraordinary Activity Assurance (EAA), which is essentially superhero insurance. In New York City, large claims or claims by people who can’t afford EAA are backed up by the (fictional) Federal Disaster Area Stipend.

Of course, while we’re modifying the law to account for superheroes, it would probably also be the case that insurance companies would include some kind of “superhero/supernatural/paranormal” exclusion, shifting that exposure more directly to the residual pool, as has been done with flood, earthquake, and windstorm exposures. However, as much as it might make sense to require superheroes to use their powers to help repair the damage they cause, the Thirteenth Amendment makes it pretty difficult for the states to impose forced labor on people not convicted of a crime or drafted into the military. On the flip side, if a superhero is sued for causing damage, he might be able to significantly reduce the settlement amount by voluntarily agreeing to use his powers in the repair efforts.

1. Dan Slott et al., Web of Lies, in SHE-HULK (VOL. 1) 4 (Marvel Comics August 2004). This does not go exactly as planned, but more on that later.

2. Dan Slott et al., Minor Complications, in SHE-HULK (VOL. 1) 6 (Marvel Comics October 2004).

3. Note that this is entirely different from the “right to privacy” recognized by the Supreme Court in Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965), in which the Court recognized a constitutional right to privacy. That case, and the cases that stem from it, have to do with governmental intrusion into arguably private affairs. Here, we discuss the law related to individual intrusion into the privacy of other individuals. The Constitution does not really apply to these cases. Remember the state actor doctrine.

4. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS § 652A. Restatements of the law are scholarly works that attempt to set forth the majority position on particular areas of law or recommended changes to the majority position. They mostly cover subjects that are still primarily common law rather than those based on legislation. The Restatements are not laws themselves, but courts often find them persuasive, and many sections of various Restatements have been adopted as law by state courts.

5. 435 So. 2d 705 (1983).

6. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS at § 652B.

7. Id. at 711.

8. William Prosser, Privacy, 48 CALIF. L. REV. 383, 397 (1960).

9. Roe ex rel. Roe v. Heap, 2004 Ohio 2504, (Ohio Ct. App. 2004).

10. Note that if the telepath violated the injunction, then he or she could be found in contempt of court and subjected to a substantial fine, even if the actual damage done was still minimal. The fine would be paid to the court, however, and not the victim.

11. The ordinary person standard strikes again.

12. If they aren’t included then they may be waived.

13. This is just another reason why masked superheroes are problematic for the Rules of Evidence.

14. Which is probably a violation of the rules of civil procedure. Any potential defendants need to be named in the pleadings and properly served. Trial is far, far too late in the litigation process to be naming additional parties.

15. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS § 652D.

16. Diaz v. Oakland Tribune, 139 Cal. App. 3d 118, 126 (Cal. Ct. App. 1983).

17. The logo would probably be protected by trademark, which is discussed in Chapter 9, but (real) names and faces are not, and in the context of the Marvel Universe, the Fantastic Four are real, rather than fictional, people.

18. PETA v. Bobby Berosini, Ltd., 895 P.2d 1269 (Nev. 1995) (emphasis in original).

19. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS § 652C.

20. MCCARTHY, 1 RIGHTS OF PUBLICITY AND PRIVACY § 5:60.

21. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS § 652E.

22. Burglar’s family awarded $300,000 in wrongful death suit, COLORADO SPRINGS GAZETTE (August 26, 2011), available at http://www.gazette.com/articles/jury-123946-burglar-lot.xhtml.

23. We focus here on characters whose powers are somehow part of their bodies, not technological in nature. Batman and the Punisher, for example, are really just ordinary men in peak physical condition who happen to have access to awesome technology. This is quite different, legally speaking, from having one’s body affected by an accident.

24. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby et al., The Fantastic Four!, in FANTASTIC FOUR 1 (Marvel Comics November 1961).

25. For example, think of signing a waiver before going skydiving. Note, though, that there are some things that can’t be waived or consented to, such as intentional serious harm or death caused by the defendant, which is something that will come up when we discuss the Hulk’s origin.

26. Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977).

27. Probably a thinly veiled reference to Exxon.

28. Dan Slott et al., Class Action Comics!, in SHE-HULK (VOL. 1) 2 (Marvel Comics June 2004).

29. Which is probably a question of law for the court rather than a question of fact for the jury, contrary to the way the story goes in the comic.

30. See chapter 7 and, umm, good luck with that.

31. “Tortfeasor” is a fancy term for “someone who commits a tort.”

32. “Business interruption insurance” is a real thing.

33. In theory the property owner could sue the tortfeasor, but there are several problems with this. For one thing, lawsuits are expensive, time-consuming, and uncertain. For another, many defendants are in no position to pay for their damages (i.e., they are “judgment proof”). Usually it’s simpler to take out an insurance policy and let the insurance company sue the tortfeasor if it makes financial sense to do so.

34. In insurance terms, a “peril” is anything that causes loss. So lightning, fire, flood, etc. are all types of perils.