4 Surface Mathematics Learning Made Visible

Copyright © Erin Null

Kate Franklin is planning a unit introducing multiplication for her third-grade class. Other than some earlier work with skip counting and simple arrays, this will be the students’ first real experience with multiplication. As Kate plans, she considers the types of learning that students will undergo as they make sense of these concepts by experiencing different situations. For example, students will model multiplication situations to develop conceptual understanding, learn appropriate vocabulary and notation for multiplication, develop strategies to build fluency with basic facts, apply understanding to worded problems (applications) as well as open-ended problems, and make connections to understand the relationship between multiplication and division. Wow! That is a lot to think about. While the textbook will help to guide her through some of this progression, Mrs. Franklin knows how important it is to carefully plan the learning intentions for each lesson while keeping the bigger picture in mind. She knows she also needs to identify the success criteria for her students to show and know they are progressing with understanding through each lesson. Mrs. Franklin plans so that by the end of this unit, her students will be confident that they understand the content, can apply concepts, and are ready to connect these concepts to future topics.

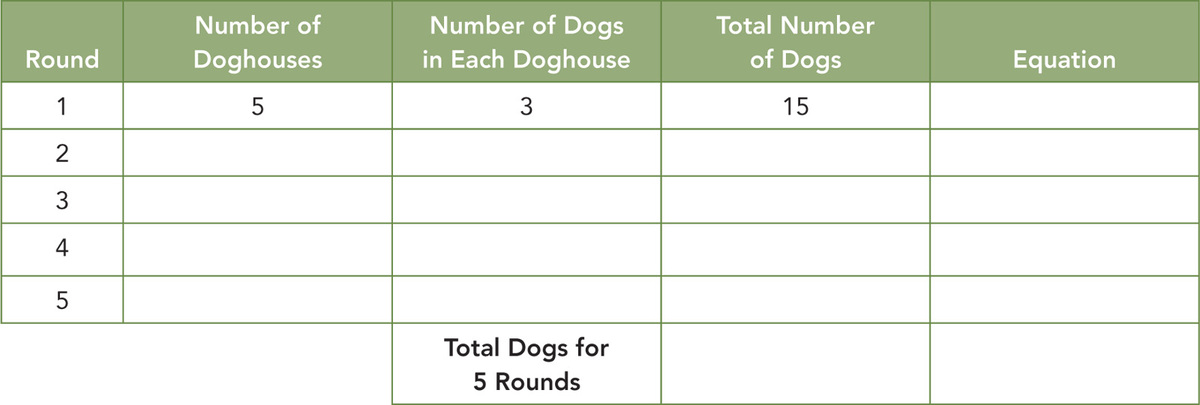

On the first day, Mrs. Franklin has made a conscientious decision to hold off on sharing the learning intention for the lesson until after students have completed an activity that introduces the meaning of multiplication as equal groups. She introduces the lesson with a game called In the Doghouse. She models the game with her students. It looks something like this. Students work with a partner. One rolls a die and lays out the corresponding number of rectangles made of construction paper (the doghouses). The second person rolls the die and puts the corresponding number of counters (dogs) in each doghouse. The students describe the number of doghouses and the number of dogs in each doghouse and then they determine the total number of dogs in all of the doghouses. They record their work on the table in Figure 4.1.

After students have a chance to ask questions, they play the game. When the students have played five rounds, Mrs. Franklin asks them to find the total number of dogs for all five rounds.

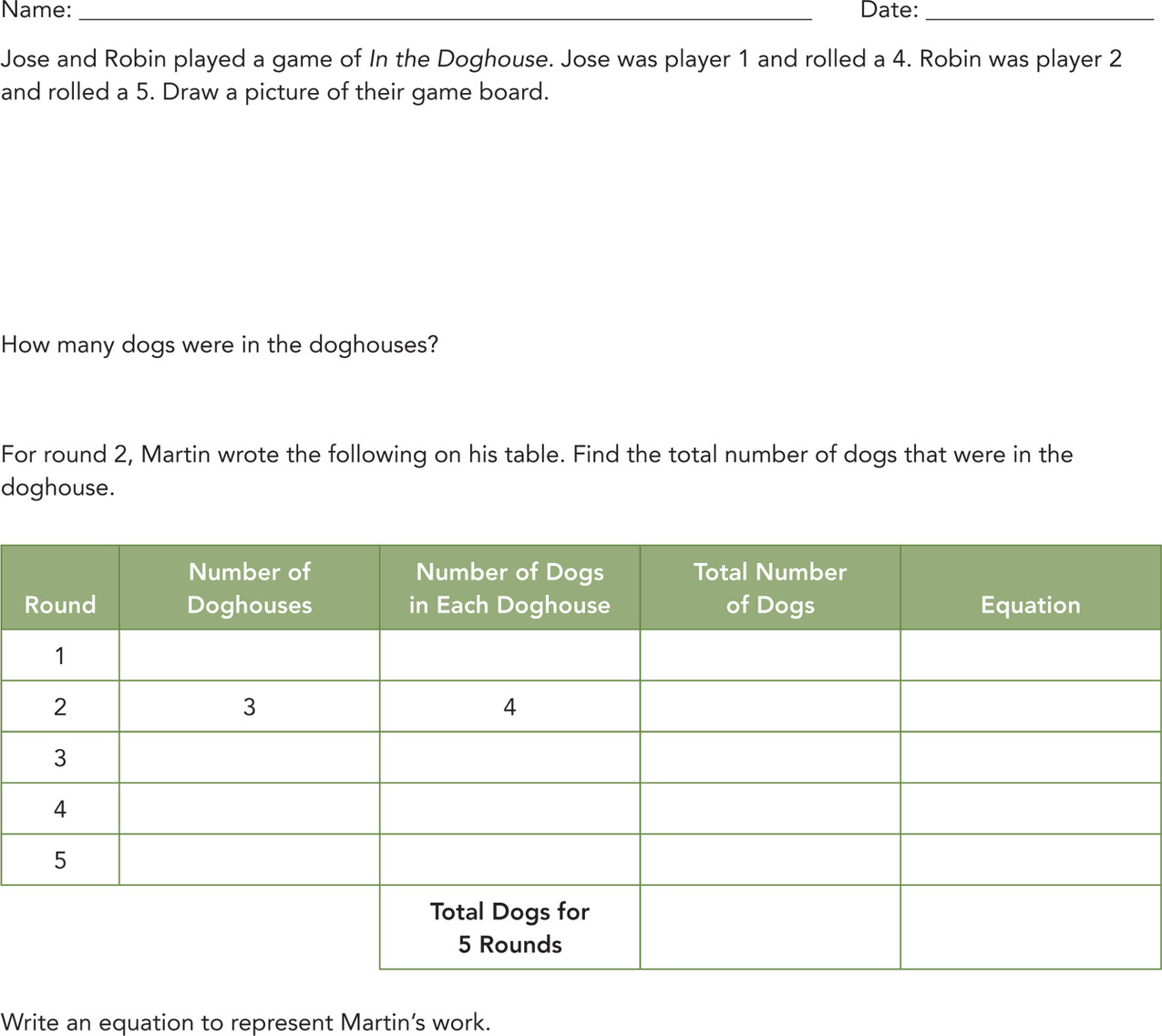

In the next part of the lesson, Mrs. Franklin leads a discussion in which students talk about what the numbers mean for each round and how they might write an equation for what they have modeled. Since most of the students recall earlier work with repeated addition, someone quickly comes up with 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 15. This continues for a few more examples, and then Mrs. Franklin models her thinking. “This is sure a lot of writing. I am going to show you a simpler way that mathematicians write this same idea because we know that there are usually many ways to accomplish things in mathematics.” She then introduces the multiplication sign and writes the equation 5 × 3 = 15. She also introduces vocabulary in the context of this example (multiplication, multiply, times, groups of) and adds these words to the mathematics word wall. The class follows with a discussion about what each of the numbers means in that equation. Mrs. Franklin then directs them to work together to record similar equations in the last column of their chart as she circulates to check on students’ understanding of the task.

Now Mrs. Franklin is ready to introduce the learning intention for the lesson. “We are using equal-group activities to write and understand multiplication equations.” She then asks the students how In the Doghouse helped them with this learning intention. After a short discussion, Mrs. Franklin presents the success criteria, saying, “I will know and you will know if you have successfully learned this by completing an exit ticket at the end of our mathematics time that lets you show how you can use equal groups and equations to represent multiplication.” Students continue with additional work and discussion, moving to pictures of groups and items and writing multiplication equations for each. Mrs. Franklin is also ready with some supporting activities for students who appear to be struggling to make the connection between the pictures and the equation. Toward the end of the lesson, Mrs. Franklin gives each of the students the exit ticket in Figure 4.2.

This lesson is an example of developing surface learning for the initial acquisition of conceptual understanding of multiplication. Subsequent lessons will continue to focus on helping students to make connections to other multiplication situations as well as using various representations to develop fluency with multiplication facts. In this lesson, Mrs. Franklin also intentionally gives students the language and structure they need to speak clearly about the mathematical ideas they are learning, so students can talk about and explore these new ideas with each other. The activity connects to the language and notation that pave the way for the rich discourse and focus on structure and relationships that are at the heart of mathematics learning. Let’s leave Mrs. Franklin and her third graders as we take a closer look at surface learning.

The Nature of Surface Learning

As we noted in the first chapter, almost everything in published research works at least some of the time with some students. Our challenge as a profession is to become more precise in what we do and when we do it. Timing is everything, and the wrong practice at the wrong time undermines efforts. Knowing when and how to help a student move from (sufficient levels of) surface to deep is one of the marks of expert teachers. Instructional practices that foster deep learning are not necessarily the most effective ones to employ when students are still at the surface level of developing mathematical understanding on any given topic. Deep learning is about noticing relationships, extending ideas to new situations, and making connections, but children first need to learn the ideas that they can then make connections among and between. That is what surface learning is about!

As we also mentioned in Chapter 1, the phrase surface learning may hold a negative connotation for many people. It’s easy to assume that by “surface” we mean “superficial” or “shallow,” or that by surface-level learning, we mean rote memorization of procedures and vocabulary that have typically been taught at the beginning of a lesson and are disconnected from conceptual understanding. This is not what we mean by surface learning. Rather, the phrase surface learning represents an essential part of learning made up of both conceptual exploration and learning vocabulary and procedural skills that give structure to ideas.

Video 4.1 Surface Mathematics Learning: Connecting Conceptual Exploration to Procedures and Skills

http://resources.corwin.com/VL-mathematics

In this chapter, we will examine the importance of surface learning and consider the use of high-impact approaches that foster initial acquisition of conceptual understanding and procedural skills. We will first guide you in the selection of mathematical tasks that promote surface learning, building on our example with Mrs. Franklin. Next, we’ll discuss the types of mathematical talk that can guide students who are in the surface phase of a topic. These include the following:

- Number talks

- Guided questions

- Worked examples

- Direct instruction

Finally, we will profile some other teaching methods that have high effect sizes when fostering students’ surface learning of mathematical concepts and procedures. Featured practices include strategic use of the following:

- Vocabulary instruction

- Manipulatives for surface learning

- Spaced practice with feedback

- Mnemonics

Keep in mind that the goal during the surface phase of learning is to create sufficient time and space for students to acquire and consolidate knowledge, with an eye toward deepening their knowledge. Don’t stay in this phase longer than you need to, but don’t rush through it and leave learners behind. Our mantra is “As fast as we can, as slow as we must.”

Two important reminders are key to visible learning for mathematics:

- The teacher clearly signals the learning intentions and success criteria to ensure that students know what they are learning, why they are learning it, and how they will know they have learned it. This clarity should guide all instructional decisions.

- The teacher does not hold any instructional strategy in higher esteem than his or her students’ learning. Visible learning is a continual evaluation of one’s impact on students. When the evidence suggests that learning has not occurred, the instruction needs to change (not the child!).

Selecting Mathematical Tasks That Promote Surface Learning

As we discussed in Chapter 3, one of the most important responsibilities of a teacher is to select the right task for the learning intention at hand. In selecting tasks that build surface knowledge, teachers want to find tasks that raise questions for students—What is this called? How can I write this? What does this symbol represent? Surface learning does not have to be the result of lectures and flash cards. Teachers can use tasks (such as In the Doghouse) to create situations that help students make meaning of the mathematics at hand accurately and efficiently. Tasks that are efficient are often also more engaging, which raises student motivation.

Many tasks that foster surface learning will be of low difficulty and low to moderate complexity (see Figure 3.1). We can make many tasks lower in difficulty by using smaller numbers and/or simpler situations, especially when a new idea is introduced. For example, primary students learn about the notation of addition and subtraction by using it first to record what they have done in solving problems using manipulatives or other models. K–5 teachers ask students to solve problems using manipulatives and other strategies so that they are reasoning about the solution and thinking about the context. The problems are straightforward and the numbers may be small. Notation is introduced as efficient ways to record thinking and build on previous experiences. In the opening example, 5 × 3 = 15 was connected to 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 as a way to record 5 groups of 3. Discussion and opportunities to connect notation to actual tasks support students’ learning and understanding. This is true throughout all of a student’s mathematics education, from learning numerals in kindergarten to the symbolic notations of algebra, geometry, statistics, and calculus.

We can look at similar tasks in middle school as students learn to operate with integers. By keeping the range of numbers small and the situations simple (for example, temperature increasing/decreasing or spending/borrowing money), students are free to consider how the problems are similar to those in elementary school as well as learn how notation changes when recording operations with integers. The complexity of these tasks is low to moderate for students with adequate background knowledge.

Figure 4.3 Surface Learning of Multiplication in the SOLO Framework

Source: Adapted from Biggs and Collis (1982).

Let’s put Mrs. Franklin’s learning intentions for the lesson she used to introduce multiplication into the first level of the SOLO framework discussed in Chapter 1. The unistructural and multi-structural levels are about having students develop surface learning about multiplication that will support future opportunities to make connections and see relationships (see Figure 4.3).

Mathematical Talk That Guides Surface Learning

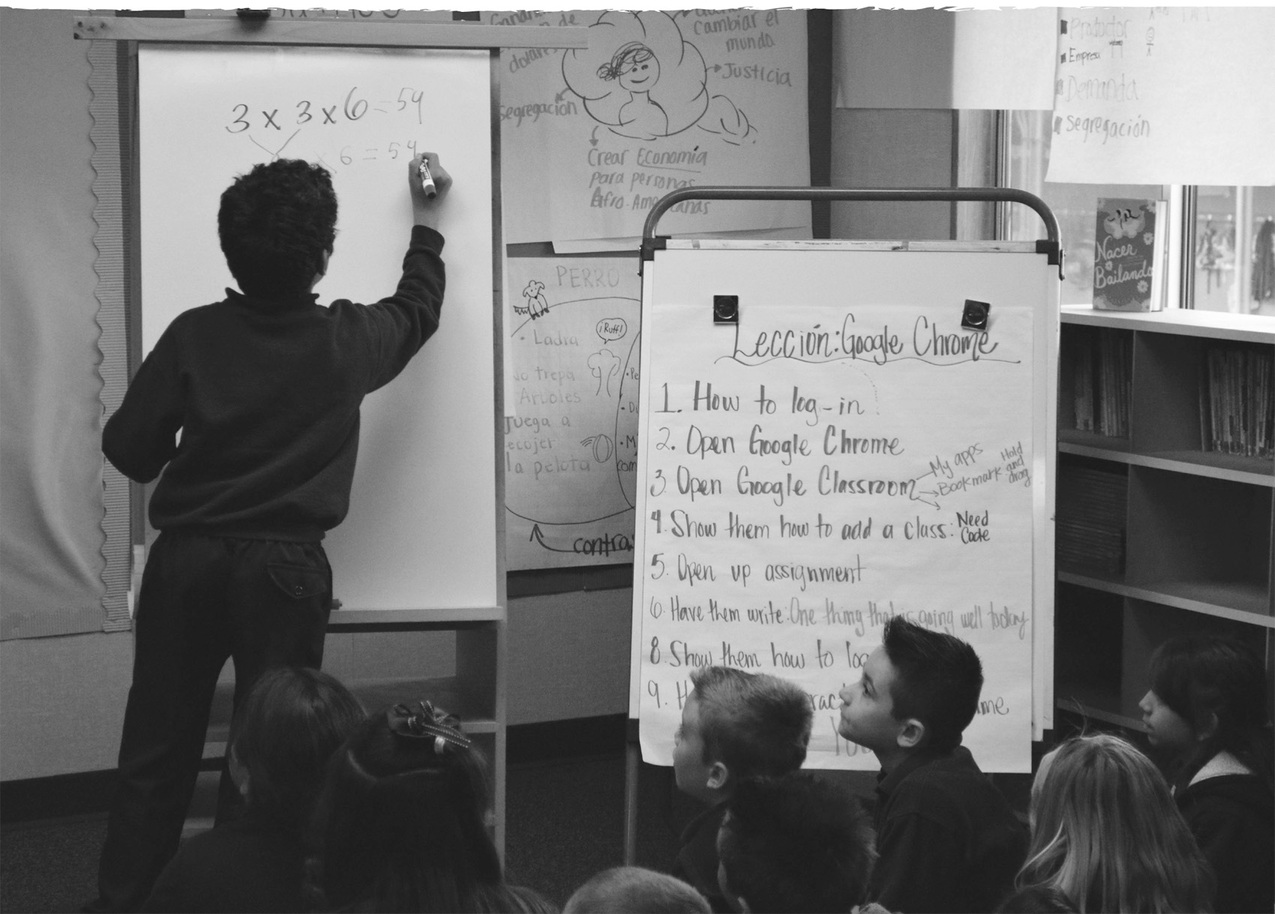

Neuroscientists in the 1990s noticed something surprising when they measured brain cell activity of monkeys that were watching the movements of other monkeys. They found that brain cells called motor neurons in the observing monkeys were active, even though these observing monkeys were sitting still. Interestingly, these were some of the same neurons that became active when the observing monkeys were the ones doing the motion. So, when a monkey watches another monkey pick up a banana, a lot of the same brain cells in the observing monkey are just as electrically active as they would be if that monkey were the one picking up the banana (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). Neuroscientists called these specialized brain cells mirror neurons. Later, they showed that mirror neuron systems in the human brain work similarly to understand intentions of others (Iacoboni et al., 2005). To these brain cells, observing someone do something uses many of the same neural pathways as when you perform the action yourself. These mirror neuron systems may help explain the power of number talks, guiding questions, worked examples, and direct instruction. Doing math is not eating bananas. But it turns out that when students explain their thinking verbally, in a way that other students can understand, all students are better able to consider the ways that other people think and adopt some of these practices themselves. By listening to others think, the student is guided through the same thought processes that someone else used, as if an apprentice. By using guiding questions, teachers can indirectly model a path for students’ thinking without telling them what to do (which often becomes the right way or only way in a student’s mind). This modeling helps to provide structure to advance student thinking.

What Are Number Talks, and When Are They Appropriate?

Number talks are a powerful protocol for students to share their thinking processes aloud (Humphreys & Parker, 2015). Mrs. Manno includes a number talk in her fourth-grade morning meeting every day. A number talk is a short, ongoing, daily routine that provides students with meaningful, ongoing practice with computation. A number talk helps students develop computational fluency because the expectation is that they will use number relationships and the structures of numbers to add, subtract, multiply, and divide. These brief (around five minutes) opportunities for students to share their thinking can be used as review or practice on a current topic. Mrs. Manno knows her students need some additional work with subtraction of whole numbers, so she is using today’s number talk for work on this topic. She starts with the following example:

3,000 − 1,345 =

She gives students some time to think about this—as number talks are usually done with mental calculations—and students signal when they think they have the answer by putting their thumb up against their chest. This is intentional so that waving hands of eager students do not distract those students who need time to think. Mrs. Manno reminds students who have an answer to think about how to find it using a different strategy. When most of the students have indicated they have an answer, Mrs. Manno begins to collect student solutions and writes them on the board without signaling if they are correct or incorrect. Once the answers have been collected, the focus shifts to student thinking. A student is called upon to share his thinking while Mrs. Manno records on the board. A conversation might begin as follows:

Juan: I used a counting on strategy, so I started with 1,345. I added 5 more to get to 1,350.

Mrs. Manno: (Writes as she revoices)

1,345 + 5 = 1,350

Juan: Then I added 50.

Mrs. Manno: Why did you add 50?

Juan: So I would get to 1,400. That will make it much easier to get to 3,000.

(Mrs. Manno records the next step beneath the first step.)

1,345 + 5 = 1,350

1,350 + 50 = 1,400

Juan: Now I added on 600 to get to 2,000 and then I added 1,000 to get to 3,000.

Mrs. Manno: (Continues to record, asking) Am I following your thinking correctly?

1,345 + 5 = 1,350

1,350 + 50 = 1,400

1,400 + 600 = 2,000

2,000 + 1,000 = 3,000

Mrs. Manno: So how did you get your final answer?

Student: I kept track of the numbers I was adding on as I went along. 5 + 50 + 600 + 1,000 is 1,655.

Mrs. Manno: Did anyone else do it this way? (Several students indicate they also used the same method.) Did anyone use a different strategy?

Students begin to share their thinking, including those students who may have made a mistake in their initial computation, but self-correct after “seeing” classmates’ thinking. Although number talks are brief, they should be done daily to be effective. Students love the opportunity to share their thinking and convince others they are correct or to question the work of others (MP 3). Mrs. Manno reports that if they do not have time for a number talk on a particular day, students will remind her as they head home that they missed their number talk, which means they have to do two the next day! By the way, it was likely not a coincidence that Mrs. Manno’s students had the highest district scores on the state tests for their grade level.

What Is Guided Questioning, and When Is It Appropriate?

In Chapter 3, we discussed two types of questions—focusing questions and funneling questions. The lines between some of these ideas are not always clear and straight. There is some overlap between when students move from surface learning to deep learning. There is not a clear delineation between good focusing and good funneling questions. There is a time for both. The key is understanding what comprises good funneling and good focusing questions and when to use each.

Too often, a lesson begins with the teacher giving explicit instruction in how to do some mathematics, whether it’s second graders working on understanding regrouping or sixth graders’ introduction to proportional reasoning. This flies in the face of helping students to use new information as an opportunity to make sense of mathematics by understanding a situation, building on previous knowledge, and extending this knowledge to new ideas. It’s like reading a mystery novel and someone tells you “who dunnit” before you have had the opportunity to make sense out of what is happening and make your own conjectures. Instead of giving away the ending, carefully constructed guided questions are designed to help students make sense out of what is going on and guide them to draw conclusions on their own.

Mrs. Rodriguez is working on the following learning intention with her second-grade students: “Discover and define attributes of two-dimensional shapes.” The first activity focuses on working with different kinds of quadrilaterals. She wants this work to be engaging and clear and not just a list of vocabulary words to memorize. She decides to do this by giving students several riddles to solve, and she begins by working together with the class to solve the first riddle:

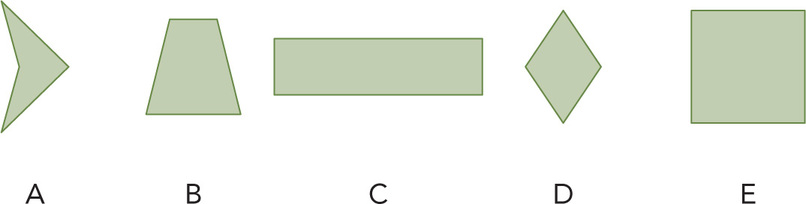

What shape am I?

- I have four sides.

- I have four right angles.

- My sides are all the same length.

She asks, “What clue would be a good place to start?” This gives students the opportunity to explore and see the advantage or disadvantage of starting with each clue. There is a great deal of discussion happening in each group of students, and Mrs. Rodriguez notices they are having a hard time coming to a consensus. So, she pulls the students back together and asks, “What if we began with the first clue, ‘I have four sides.’ Draw some shapes with four sides.” She selects a few students to draw their shapes on the board, and she draws some shapes that the students haven’t thought of (see Figure 4.4). Then she continues, “Look at these shapes. What is the same? What is different?”

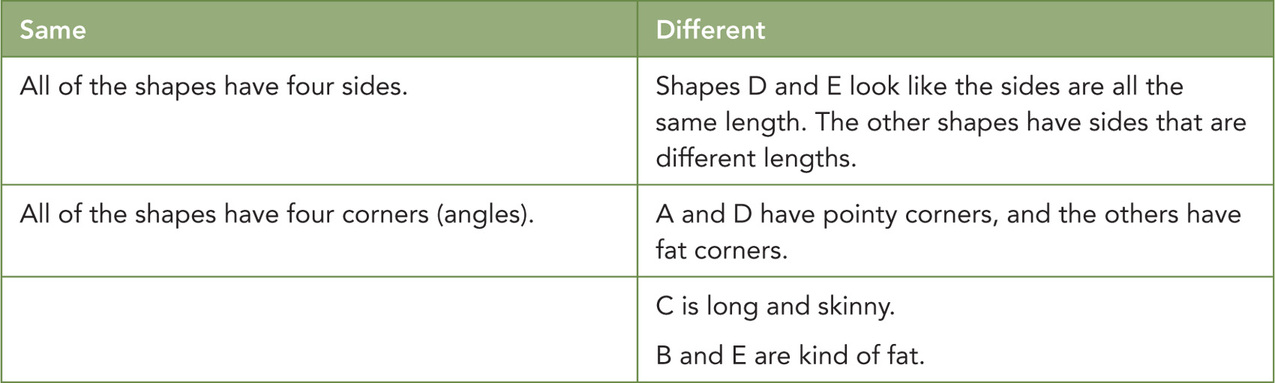

Students then discuss what is similar and what is different using their own words. Mrs. Rodriguez keeps track of the ideas students raise, saying, “You all have some excellent ideas, and it would be helpful to keep track of them so we can look back as we look at the other clues. I am going to make a table on the board to record your ideas. Let’s also label the shapes so if there is something special about a shape, you can identify which one it is.” (See Figure 4.5.)

After the students complete their list, Mrs. Rodriguez can identify some vocabulary that will help her students. She reminds them that another name for corner in these shapes is angle. She points to the angles in shapes C and E and asks, “How would you describe these angles?” Students use their own words, comparing the angles to the corner of a window or the corner of a room. Mrs. Rodriguez writes the words right angle on the board and explains that the corners they have described that look like the corners of the window or the room are called right angles. She continues, “Can you find some other corners or angles in the room that are right angles?”

“Let’s take a look at the second clue. Do any of our shapes have four right angles?” Students talk in small groups, and the class agrees that shapes C and E have four right angles. Some of the students are also debating whether shape D has four right angles. Rather than tell the students, Mrs. Rodriguez suggests they cut out a shape that looks like shape D and asks how they might compare it with C and E. After a brief discussion, the students agree that if they turn D so the bottom is straight, they can see it doesn’t have four right angles.

“Which shapes now fit the first two clues?” asks Mrs. Rodriguez. As the students respond, she circles C and E on the board. “How can we use the final clue to solve the riddle?” The students explain their thinking and agree that the sides of shape E are the same length, so that shape must be the answer. Mrs. Rodriguez agrees and follows up by reminding students that this shape is a square. She concludes the lesson by asking, “What are the characteristics of shape E that the clues tell us?” She leaves the students to ponder this question: “Do all squares have all of these characteristics?”

Students continue working in small groups to solve a few other riddles that deal with two-dimensional shapes. At the conclusion of each riddle, the class meets to discuss their representations and their solutions. Mrs. Rodriguez then introduces the appropriate vocabulary and adds these words and pictures to the mathematics word wall.

Video 4.3 Guided Questioning for Surface Learning

http://resources.corwin.com/VL-mathematics

Think about how, rather than telling students what to do, her questions and prompts led students to think about what was needed to solve the riddles and how they could justify their solutions. Mrs. Rodriguez used guiding questions to help students get started on the task and was ready for follow-up examples to which students could apply what they just learned. Making a table was an important strategy to organize their ideas and also linked to understanding new vocabulary.

Asking good questions when a new concept is being introduced—meaning questions that do not give too much information but rather guide students’ thinking—requires practice. We have to make a conscientious decision about the questions we want to ask as we are planning lessons and more so when we are actually in the midst of teaching. That means your questions depend on the responses and questions of your students and what you see evidenced in their work. In order for surface learning to take place, questions should engage students as well as guide them to the understandings and connections that are determined by your learning intentions. One word of advice: too often we respond by giving students too much information rather than asking a question that will push their thinking forward just enough to allow them to think differently about a situation. Give yourself permission to stop and think about the “right” question to ask at any given point in the lesson. Good questioning takes lots of practice.

Video or audio recording a lesson and taking the opportunity to watch or listen to the recording, to focus on the questions you have asked, can be very helpful in developing expertise. Some call this practice micro-teaching, which is when a lesson or “mini-lesson” is video recorded and then reviewed and analyzed by the teacher in order to improve the teaching and learning experience. Jim Knight and his colleagues (Knight & van Nieuwerburgh, 2012) analyzed the work of teachers and instructional coaches over a three-year period as they interacted with video and audio recordings of lessons, and they found that these tools propelled improvements in instructional quality more effectively than lesson debriefing alone. Similar effects were also seen with individual teachers who coached themselves by watching videos of their own teaching.

In the shape lesson, Mrs. Rodriguez explicitly modeled making a table to help her students organize their thinking to help solve the problem. You might be thinking to yourself that you would never do that, because you believe effective math teachers are the ones who give their students the space to figure things out for themselves. After all, students can gain a longer-lasting and more meaningful understanding when they make sense of problems, persevere in solving them, and own their learning. But also note that Mrs. Rodriguez didn’t rush in immediately. She let her students work through the riddle on their own first, and stepped in when she saw them struggling to reach a consensus. The principle of productive struggle or productive failure (Kapur, 2008) suggests that students who confront and fail a challenging problem and are then provided further clarifying instruction outperform traditionally taught students. There can be value in presenting a task before kids have all of the prerequisite skills, letting them struggle a little, and then looping back and teaching them the skill within the meaningful context of the task. However, productive struggle should not be confused with impossible tasks.

What Are Worked Examples, and When Are They Appropriate?

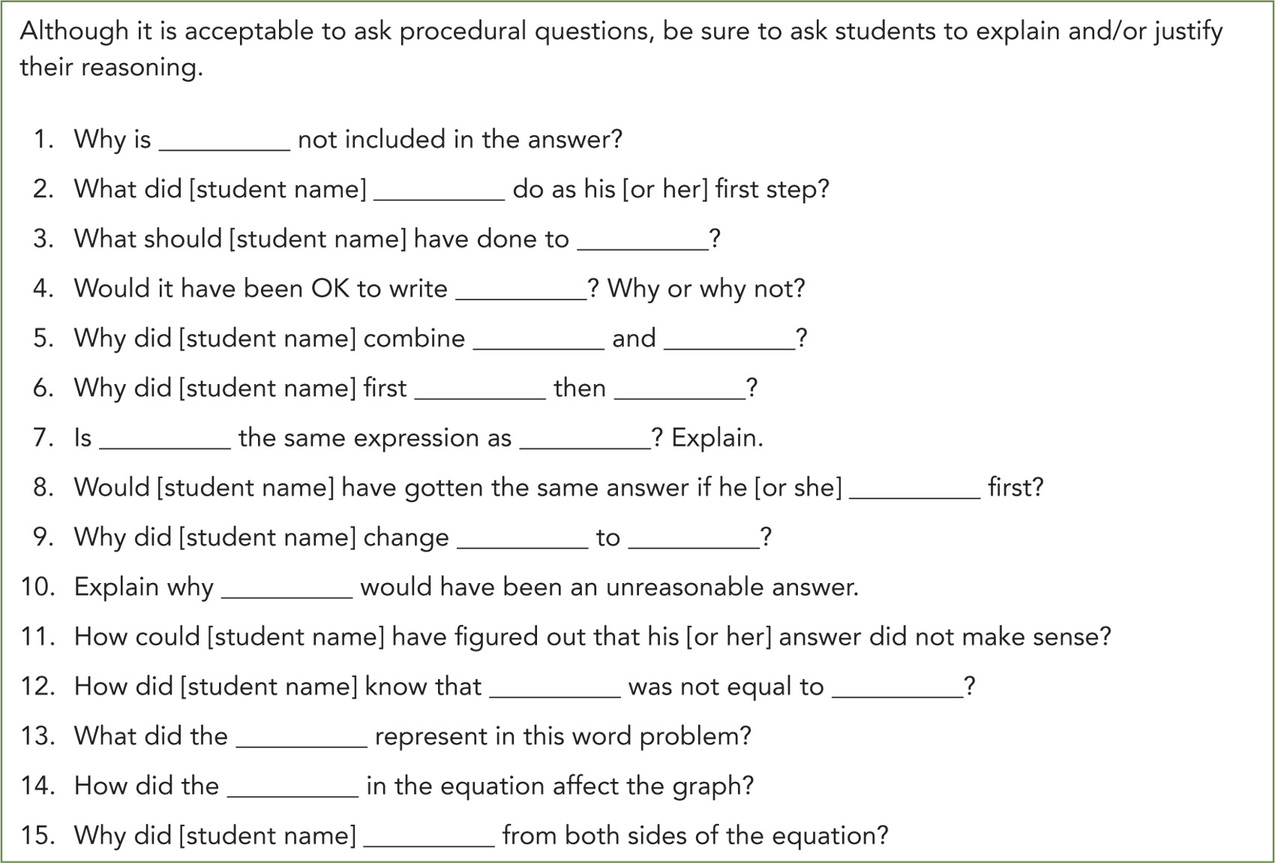

A worked example is a math problem that has been fully completed to show each step of a mathematician’s arrival at a solution. These have been shown to be useful for students in completing problems more efficiently and accurately (Atkinson, Derry, Renkl, & Wortham, 2000; Sweller, 2006). It is important, of course, to identify from the beginning whether a worked example is correct or erroneous. Worked examples that are erroneous as well as those that are correct can spark students’ thinking as they hypothesize why the mathematician made the decisions he or she did to arrive at a solution. These examples can range in topic, but generally provide students with examples of mathematical reasoning, especially in demonstrating for students how to speculate, problem solve, and formulate reasons. McGinn, Lange, and Booth (2015) advise that worked examples should be developed in such a way that they provide the opportunity to highlight an anticipated misconception and that they are followed by a similar problem that students can solve collaboratively or independently. Caution: especially with younger students, be sure your students have a good conceptual understanding before they respond to incorrect worked examples so that they do not replicate error patterns in future work. The questions one should verbalize should focus less on procedural knowledge and more on querying the reasoning used—in other words, more “why” questions and fewer “what” questions. Figure 4.6 contains suggested self-questioning prompts that can be utilized by the teacher while thinking aloud using a worked example.

Figure 4.6 Sample Prompts to Use When Self-Questioning

Source: McGinn, Lange, and Booth (2015). Used with permission.

Fifth-grade math teacher Susana Knowles sometimes uses a process called My Favorite Mistake to share her thinking. Ms. Knowles has students complete a problem or exercise on an index card at the beginning of class, and then quickly sorts through them to locate one that has a common error or an interesting strategy to get to the correct solution. She rewrites it so that the child’s handwriting is not recognizable, and always assigns a pseudonym. “I always call him ‘Amazing Aloysius,’ because he dazzles us with what he knows and doesn’t know, and always makes us think. Amazing Aloysius might make an error or has an interesting path to a solution so that the rest of us can learn,” she explained.

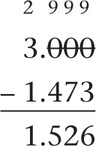

During a unit on subtracting decimals, Ms. Knowles gave her students the following to solve.

3 – 1.473

She chose this particular example, because it is one that students often struggle with as they work to regroup. Several students made the same error, so Ms. Knowles copied the following on the board.

For several minutes, the teacher speculated about ways that the student arrived at the solution, asking herself aloud, “I wonder why Amazing Aloysius decided to rewrite this problem vertically?” “I wonder why he chose to put a decimal point followed by three zeroes?” and “I wonder why he crossed off the zeroes and made them all nines?” She paused after each question and let students reply. “It gives them the chance to see how I can ask myself questions to justify what the student did and why he may have done it. It also clears up misconceptions that students may have based on earlier misconceptions.”

What Is Direct Instruction, and When Is It Appropriate?

There are times in a lesson or sometimes with particular students—particularly when students are struggling to understand an idea and other student-centered approaches are not yielding the results a teacher wants—when assistance or explanation from a teacher helps to focus the mathematics so that students can get a different perspective (in this case, the teacher’s perspective). Before delving into this, we need to recall from Chapter 1 what we mean by direct instruction. As we hope you will see, direct instruction does not mean lecturing. Instead, as Lobato, Clarke, and Ellis (2005) note, there should be “teaching actions that serve the function of stimulating students’ mathematical thoughts via the introduction of new ideas into the classroom conversation” (p. 136).

Video 4.4 Direct Instruction: The Right Dose at the Right Time

http://resources.corwin.com/VL-mathematics

Often in mathematics, “direct instruction” is interpreted to mean “show-and-tell” math where the teacher launches a lesson by showing students how to do a procedure, gives them all the vocabulary terms they could ever want, and then sends them off to work on problems independently. This often happens in traditional lecture pedagogy. But we are not talking about a scripted transmission model or didactic teaching. By contrast, recall that in Chapter 1 we defined direct instruction more as a carefully scaffolded and guided instructional process that is done with great intention. It is when the teacher decides the learning intentions, makes them clear and visible to students, may do some demonstration, checks for understanding, and recaps what they have done by tying it all together with closure.

It is important to recognize that there is a big difference between teaching and telling. Direct instruction should focus on teaching and improve the ways in which teachers provide students with information. As Munter et al. (2015a) noted, “Those more aligned with direct instruction do not argue that teachers should simply provide facts and procedures to students and ask students to memorize and practice them over and over until proficient. Likewise, those more aligned with dialogic instruction do not advocate ‘pure discovery learning,’ in which students somehow manage to re-invent the mathematics curriculum” (p. 24). There are three important things to keep in mind about direct instruction:

- It should not be used as the sole means for teaching mathematics (Munter et al., 2015b). It should be used strategically to build students’ surface knowledge when they need it.

- It does not have to—nor should it—consume a significant portion of the instructional minutes available for learning. The majority of instructional time should actually be devoted to students doing mathematics and talking about their work and understandings to build deeper level learning.

- It does not have to be used solely at the outset of a new unit of study or the beginning of a lesson. There is evidence that effective direct instruction can follow students’ exploration of an idea or concept (Loehr, Fyfe, & Rittle-Johnson, 2014). There is also evidence that students can solve problems targeting concepts that are new to them (Kapur, 2012).

Irrespective of where and when within a lesson or unit it occurs, there are times when students need some direct instruction, as it is especially useful in developing students’ surface-level learning.

Direct Instruction of the Mathematical Practices

We do not want to limit the discussion about direct instruction to skills. Yes, there is evidence that computational and procedural skills can be increased through direct instruction (e.g., Flores & Kaylor, 2007). Direct instruction can also be used to develop students’ thinking. Think back on the list of mathematical practices we introduced in the preface (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010):

- Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them.

- Reason abstractly and quantitatively.

- Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.

- Model with mathematics.

- Use appropriate tools strategically.

- Attend to precision.

- Look for and make use of structure.

- Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning.

Like the practice or process standards in non-Common-Core states and nations around mathematical problem solving, reasoning, communication, and modeling (see Appendix C), these are habits of mind and ways of thinking that students may, or may not, figure out on their own. We really hope that teachers don’t wait for students to figure out ways of attending to precision through precise mathematical language any more than we hope that they will wait for students to learn how to use certain features of graphing calculator software. Designing lessons and activities that naturally involve students using these practices is the most ideal. These practices are something that students must experience and do as they develop as budding mathematicians. Direct instruction can allow students to see these mathematical practices in action. None of us developed our ability to use appropriate tools strategically in isolation or in one sitting. Rather, we developed that practice over time as we were provided examples and non-examples, listened to others, and tried our hand at it. For novices, the mathematical practices often need to be taught directly, explicitly, intentionally, and frequently through teacher modeling. Over time, and with practice, students will begin to incorporate these habits into their daily work. In other words, direct instruction about the mathematical practices can provide students with surface levels of comprehension about them, setting them up to move to deep learning and transfer their learning, which occurs when they begin to practice the mathematical practices and consolidate their understanding in collaboration with others.

Ms. Senger has a bulletin board dedicated to the mathematical practices. There is a poster for each practice that describes the practice in language that is accessible to her seventh- and eighth-grade students. Early in the year, she begins class by discussing one of the practices, what it means and what it looks like. She purposefully designs lessons so that a practice is transparent, and she often stops and points out when students are using the practice during the lesson. She does this for each practice over the first few weeks of school. These mathematical practices are worth explicitly applying again and again, in many different contexts, across a wide range of math content. By mid-October, the students are well versed in each of the practices. Ms. Senger then plans her mathematics tasks and lessons so her students are using several of the practices at any given time. Ms. Senger leaves the bulletin board up all year because these habits of mind are constantly under development, and students should be thinking about how to use them throughout a lesson. In fact, at the end of some lessons, Ms. Senger’s exit ticket asks students to reflect and describe which practices they used that day and what they learned about doing mathematics from their use.

The practices are not just for older students. Some of the most effective mathematics lessons in earlier grades include students using these practices to make sense of the mathematics they are doing. Let’s revisit Mrs. Franklin’s class as they are beginning to work with ideas of multiplication. The game they are playing has them modeling equal-group situations as they begin to make sense of the structure of multiplication. As students learn how to write a multiplication equation and use the appropriate vocabulary to describe what the numbers in the equation mean, they are using precision. What is so powerful about these practices is that instruction should not stop in order for students to apply these practices; rather, the practices are an integral part of doing mathematics. And these practice-related experiences have positive effect sizes.

Mathematical Talk and Metacognition

When using the above mathematical talk activities (number talks, guided questioning, worked examples, and direct instruction), teachers are able to demonstrate the kinds of questioning and listening strategies that exemplify excellent mathematical practice, as well as give their students opportunities to begin building these habits of mind.

Perhaps more importantly, this is when students can begin to practice the self-verbalizing and self-questioning skills that will help them think critically about the conceptual and procedural processes they are using. Teachers can model these talk patterns for students and encourage them to practice them in a number of ways. For example, teachers can get students in the habit of using “I” and “Because.”

A lot of teachers say “we” or “you” during their lessons, but “I” statements do something different and more powerful for the brains of students. They activate the ability—some call it an instinct—of humans to learn by imitation. The use of “I” statements also encourages empathic listening, which is why this approach is used in conflict resolution and marriage counseling. When students are encouraged to use “I” statements, they recognize that they are the force acting upon and understanding the mathematical ideas and employing the mathematical practices. This is particularly useful when constructing viable arguments and critiquing the reasoning of others (MP 3). When students hear their teachers and peers using “I” statements regularly, they will begin to build the habit too.

Another important habit to build is using the word “because.” In mathematics, it’s important to explain why you’re thinking what you’re thinking. If a teacher or peer is explaining his or her own thinking, using because reduces the chance that students will be left wondering how someone knew to do something or why that person was thinking a certain way. Similarly, reduce the what and increase the why and how questions. Thinking about one’s thinking is a metacognitive act, and students will start to think more metacognitively when they hear others, including their peers, do so. Metacognition is thinking about one’s own thinking, and there is plenty of research showing that students who use metacognitive strategies tend to achieve more (Schoenfeld, 1992; Veenman, Van Hout-Wolters, & Afflerbach, 2006).

Some of the metacognitive strategies useful in mathematics include having a plan for approaching the task, using appropriate skills and strategies to solve a problem, monitoring and noticing when a problem doesn’t make sense, self-assessing and self-correcting, evaluating progress toward the completion of a task, and becoming aware of distractions (Rosenzweig, Krawec, & Montague, 2011; Throndsen, 2011).

A handful of your students might do this instinctively, but if you’re serious about all of your students reaping the benefits of thinking about thinking, you’ll need to teach metacognitive strategies explicitly, and mathematical talk can be a great vehicle for doing so. Remember that students need to be taught to assess their learning in relation to the success criteria. This is key to moving them forward from surface learning to deep learning. Figure 4.7 contains sample sentence frames that teachers can use to facilitate student metacognitive thinking, organized into the three phases of planning, monitoring, and evaluating.

Strategic Use of Vocabulary Instruction

Vocabulary knowledge is a strong predictor of understanding across content areas (Graves, 2006), and at the 0.67 effect size, strong vocabulary programs fall well into the zone of desired effects. With quality instruction, students move from everyday language to more formal mathematical language, eventually developing a mindset for thinking mathematically. This also speaks to mathematical practice 6, which, in referring to attending to precision, includes precision with mathematical language. Furthermore, Simpson and Cole (2015) note that vocabulary instruction has to extend beyond word learning and believe that “for students to be successful in mathematics classrooms, educators must become cognizant of the role of language in establishing classroom norms, negotiating identities, and challenging inequitable distributions of power” (p. 369).

Vocabulary instruction, like other aspects of the mathematics curriculum, must be taught for depth and transfer (Bay-Williams & Livers, 2009), but it often begins during the surface phase of learning so that students can begin to build the academic language they’ll need to discuss and debate their thinking with precision going forward. Unfortunately, too many children and adolescents experience vocabulary instruction as making passing acquaintance with a wide range of words that are disconnected from conceptual understanding. Students assume that many of the words won’t be used again, and that next week there will be a new list.

So what does it mean to know a word? Vocabulary knowledge should be viewed across five dimensions (Cronbach, 1942, cited in Graves, 1986):

- Generalization through definitional knowledge

- Application through correct usage

- Breadth through recall of words

- Precision through understanding examples and non-examples

- Availability through use of vocabulary in discussion

Furthermore, there are different types of words that serve different functions. As we discussed in Chapter 2, researchers (e.g., Beck et al., 2013) suggest that vocabulary can be divided into three main categories:

- Tier 1—everyday words

- Tier 2—general academic words that change their meaning in different content areas and contexts

- Tier 3—domain-specific words that are consistently used in a given content area

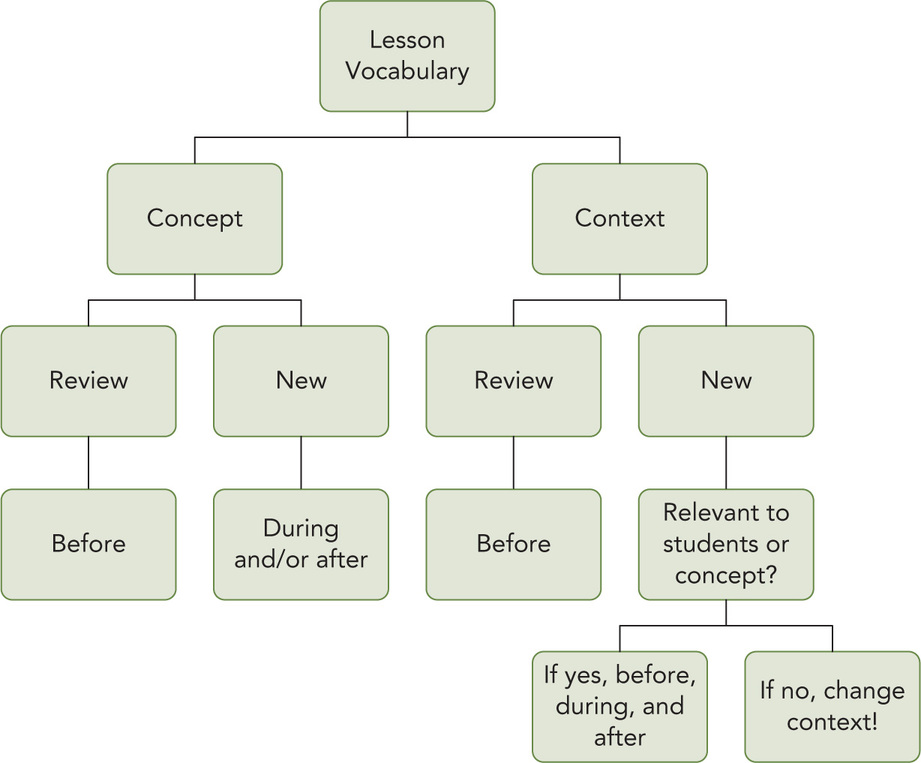

In addition to identifying words that students need to know, the timing for providing instruction on those words is important. In too many cases, students are exposed to new words before they need to use them. Livers and Bay-Williams (2014) suggest that mathematics teachers have three options for introducing vocabulary:

- Preteaching—providing instruction at the beginning of a lesson

- Just-in-time—during the course of the lesson as students need to use the word

- Formalizing—or at the end of the lesson once students have explored a concept

These researchers note, “Vocabulary support must assist in giving students the appropriate terminology they need to engage in the lesson but not give away the mathematical challenge of the lesson” (p. 154). How many of us have heard (or even taught) students to reduce fractions? But we are not reducing anything at all! When we change

There are several teaching strategies one can use to foster good use of academic language. We’ll focus on two: word walls and graphic organizers.

Word Walls

A word wall is an ongoing, organized display of key words that provides visual reference for students throughout a unit of study or a term. To keep students focused on the academic vocabulary expected of them, teachers post the targeted vocabulary on the wall, bulletin board, or white board. Teachers may elect to include a brief definition, picture, or example with the word. Words can be placed on the word wall at the beginning of a unit or as new vocabulary is introduced throughout the unit. Students are reminded to use the words as they talk with one another. Cunningham (2000) warned that having a word wall is unproductive unless we are also “doing” the word wall—meaning actively referencing it throughout the lessons. Biddle (2007) notes that her students use the math word wall in their discussions and in their journal writing.

Figure 4.8 Decision Making for Language Support

Source: Livers and Bay-Williams (2014). Used with permission.

Word walls can be used especially in vocabulary-heavy units such as geometry. However, they can also be effective as new concepts are introduced or as words take on new contexts. Mr. Gray began his fifth-grade year with a study of number theory. Some of the vocabulary (factor, multiple, product) was review and other terms (divisible, prime, composite, prime factorization) were new to the students. Mr. Gray prepared the words for the word wall by writing them on colorful cardstock with a contextual example for each word. At the beginning of the class, he asked students to add the new words for that day to the wall. Students became “detectives” as they watched and listened for the words to be used in the lesson. Students were responsible for recording the words and the examples in the vocabulary section of their mathematics journals for future reference. Interestingly with the words and examples, students did not mix often-interchanged words such as factor or multiple and prime or composite. Mr. Gray took down the words at the end of the unit so that students were not overwhelmed with the number of new and review vocabulary as the year progressed, although they regularly reviewed previously learned vocabulary.

Graphic Organizers

Students can also master vocabulary by creating graphic organizers such as a Frayer model, Word Splashes, or Anchor Charts. A graphic organizer is a visual display that demonstrates relationships between words, facts, concepts, or ideas.

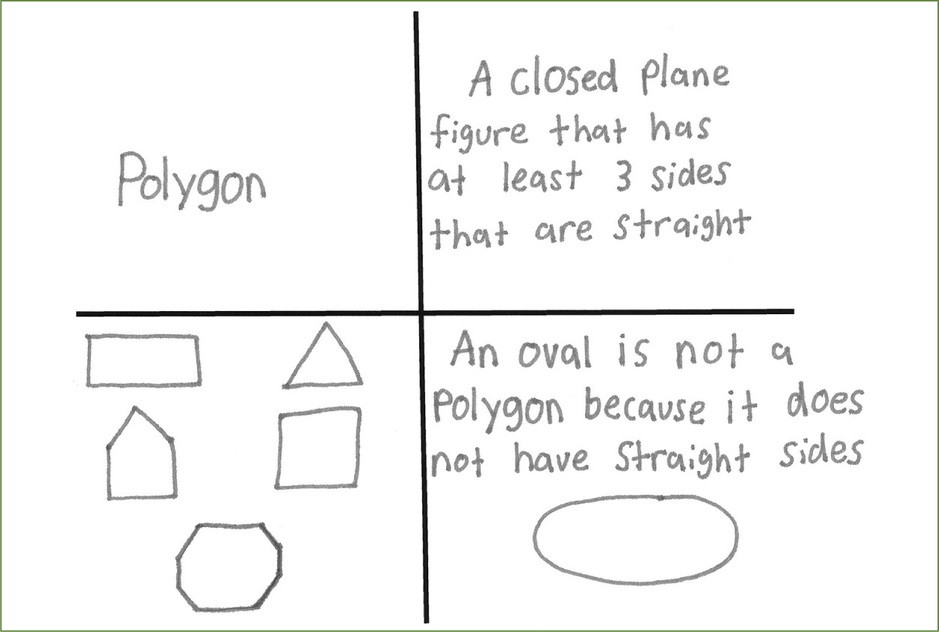

Grecia Cordova uses the Frayer model to help her students develop a deeper understanding of new vocabulary (Frayer, Frederick, & Klausmeier, 1969). Her sixth-grade students divide a 4 × 6 index card into four quadrants and write the targeted word in the upper left-hand quadrant. The definition, written in the students’ own words after the teacher explains the meaning, is included in the upper right-hand corner. Next, they write a non-example or opposite of the word in the bottom right-hand corner. In the bottom left-hand corner, students illustrate the meaning of the word. The image they choose is vital and is thought to embed newly learned information into a visual memory students can retrieve. Ms. Cordova explains, “I ask students to create these word cards as I introduce new terms for them, and then they use these for rehearsal and memorization.” An example of Horacio’s word card for polygon appears in Figure 4.9.

Strategic Use of Manipulatives for Surface Learning

Manipulatives, such as Cuisenaire rods, linking cubes, algebra tiles, and tangrams, have long been used in mathematics classrooms, and with good reason—because they work (Domino, 2010; Gersten et al., 2009). Manipulatives can also be virtual (check out the National Library for Virtual Manipulatives at Utah State University, http://nlvm.usu.edu/en/nav/vlibrary.html). Whether physical or virtual, these tools are used by students, either individually or in small groups, to explore math concepts in order “to help them build links between the object, the symbol, and the mathematical idea they represent” (National Research Council, 2001, p. 354). This is an example of using a surface learning technique with an eye toward deep learning, in that the use of manipulatives bridges students’ learning as they move from surface to deep.

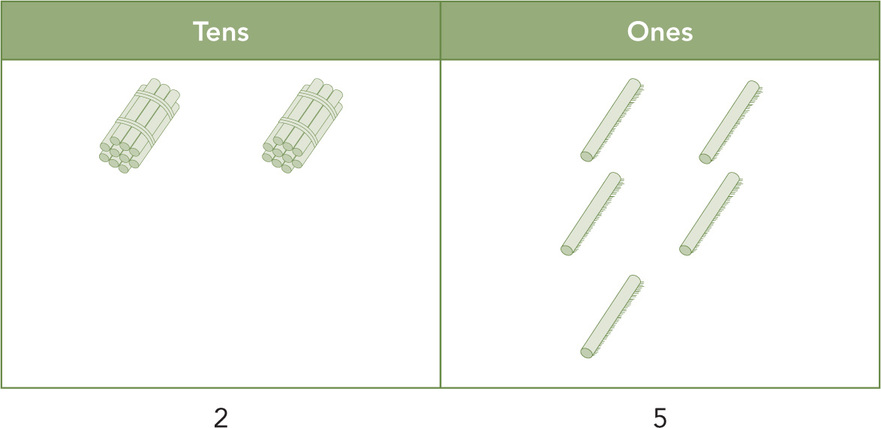

Understanding place value in our number system is one of the most foundational ideas for elementary children to understand. A full comprehension of place value includes understanding the relationship between the place each digit holds in a multidigit number and the value of that place. For example, in the number 3456, the digit 3 actually represents three thousands, whereas in the number 2453, the digit 3 represents three ones. Without this understanding, students cannot compare or order numbers, and they have great difficulty developing strategies for whole-number operations.

There are many place value tools, such as arrow cards, expanded notation, and base ten blocks, but Mr. Martin’s favorite are coffee stirrers and small rubber bands or twist-ties. He begins by having each first grader make his or her own place value mat (Figure 4.10), and students begin to count with the straws. However, as soon as they get ten ones, they put a rubber band around the straws and the ten becomes a new unit with its own place on the place value chart. Students build numbers up to ninety-nine. They compare the models on their place value chart with numbers on the hundreds chart that hangs in the classroom. They write the numerals under their models and compare their number with the numbers that others in their group have modeled. As students begin to add (put together) two-digit and one-digit numbers, they physically put ten ones together and move that bundle to the tens place before they ever write an equation. In Grade 2, Mrs. Sofal continues to build on previous experiences as students extend their place value chart to the hundreds place and continue to regroup in addition and subtraction. This provides students with the opportunity to make sense of place value in a very physical way, thus building the surface learning that will become deep learning as they apply this knowledge to develop algorithmic procedures.

Figure 4.10 Manipulatives on a Place Value Mat

Source: Clipart courtesy FCIT, http://etc.usf.edu/clipart.

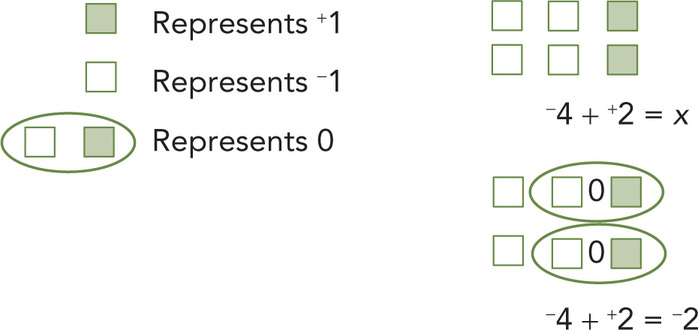

In middle school, Sara uses algebra tiles to teach addition of integers. It is important that students see this as another example of addition that they have studied since kindergarten. The students understand addition as an operation that joins sets of objects or numbers together, so she uses algebra tiles to extend this understanding to adding positive and negative numbers. Sara wants to emphasize that we are still adding two sets (in this case, sets of tiles representing negative 4 and positive 2), so she writes the example using the signs with each number: –4 + +2 = x. She asks the class what the example represents, and Ian responds, “We’re putting together a set of four negative tiles with a set of two positive tiles.” The class uses the tiles to create a model of the situation. They talk about what happens when one negative joins one positive and after discussing several real-life examples, they agree that this would result in zero. As they return to their models, they can see that they have two pairs that combine to make zero. They note that there are two negative tiles left, so the sum is –2.

By using algebra tiles to work these problems and recording their work in sketches and equations, students build their surface learning knowledge of adding integers and connect it to their previously learned knowledge of adding whole numbers. As their surface learning of adding integers becomes stronger, they will transition to the convention of not writing the sign for positive addends. From these patterns, as they take their learning into the deep phase, they will begin to make generalizations and develop the rules we use to add integers efficiently.

Strategic Use of Spaced Practice With Feedback

We have situated the dual approaches of spaced practice (often known as distributed practice) and feedback within our discussion of surface learning, because like the previous strategies (especially metacognition in number talks, guided questions, and worked examples), they teach children as much about thinking as they do about tasks. In building the learner’s awareness of the processes they use, we bridge surface-level acquisition and consolidation by fostering the skills they will need to plan, investigate, and elaborate as they deepen their learning. In this context, spaced practice is about maintenance of recently acquired knowledge, not rehearsal. Spaced practice has to do with the frequency of different learning opportunities—having multiple exposures to an idea over several days to attain learning, and spacing the practice of skills over a long period of time.

By way of example, most textbooks focus student practice on the current skill being taught. A student might be expected to do up to 25 exercises that focus on a particular skill such as adding mixed numbers. Some teachers will adjust the assignment to doing a specific set, perhaps odd-numbered examples. But the point is that once the assignment is complete, there is no ongoing practice. Assignments or class practice is more effective when done in regularly spaced intervals, rather than clustered together for a short, intensive period of time (massed practice). Although explanations for why this phenomenon exists vary, recall of information is better after spaced practice when compared with massed practice sessions. However, spaced practice shouldn’t be limited to practicing computational skills. Effective teachers build problems that require previously learned concepts and skills into warm-ups, homework, and collaborative group work in order to maintain knowledge that might otherwise atrophy.

Mathematics educator, author, and consultant Steve Leinwand (2016) describes a 2–4–2 strategy for mathematics homework that is designed to build distributed practice into the homework process. Daily homework includes 2 problems on the new skill, 4 cumulative review problems, and 2 problems that support reasoning and justification by requiring students to show and explain their work. The four cumulative review problems come from content taught the day before, the week before, and the month before the current assignment (one item each); the fourth problem in this group could be a diagnostic readiness check for a lesson in the near future or an additional cumulative review problem. By incorporating this idea of distributed practice into a homework routine, teachers can more easily ensure they are using this research base effectively.

Distributed practice events can further provide students and the teacher with essential feedback about the progression of learning. Brookhart (2008) defines feedback as “just-in-time, just-for-me information delivered when and where it can do the most good” (p. 1). At their best, these spaced practice events can and should be used formatively by the student such that his or her learning becomes visible. Feedback to the student is important at this stage, and we encourage teachers to extend beyond feedback about the task (e.g., noting the number of correct and incorrect responses).

Rather, feedback about the process, not just the task, moves students to deeper learning. We want students to note their errors and have chances to address them. But simply supplying the correct answer for the incorrect one doesn’t do much for their thinking. Feedback that prompts a student to seek more information or reconsider her approach and reasoning, or points out a path to pursue, gives the student agency and puts her in the driver’s seat of her own learning. In turn, it reduces reliance on outside judgments of her progress (you) as she begins to see it for herself, and better still, realizes she can act upon it. That, by the way, contributes to a positive math mindset (Boaler, 2016). For example, saying to a student, “You identified that you answered the third one incorrectly. Could a mathematics model help you sort out the problem?” mediates her thinking, without doing all the thinking for her. We’ll discuss feedback in much greater depth in Chapter 7, especially as it applies to the ability to self-regulate.

Strategic Use of Mnemonics

Mnemonics are memory devices that assist learners to recall substantial amounts of information, such as mathematical concepts like orders of operation and the quadratic formula. “It is a memory enhancing instructional strategy which involves teaching students to link new information that is taught to information they already know” (DeLashmutt, 2007, p. 1). As is often the case, mnemonics could be a short song, an acronym, or a visual image that is easily remembered to help students who have difficulty recalling information.

How often have you used this strategy (even if you couldn’t name it) to recall a string of words? “Roy G. Biv” to remember the colors of the light spectrum (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet) or “HOMES” to recall the names of the U.S. Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior). In addition to name and musical mnemonics, other techniques include using an image or an expression (“Every Good Boy Does Fine” to recall that the lines on the musical treble staff are E, G, B, D, and F). A mnemonic device is a memory aid used to link a string of words together.

Mnemonics can be useful if used appropriately. Too often, they are used to replace an understanding or to present students with a trick that overrides an important understanding, and often lead to misconceptions (Karp, Bush, & Dougherty, 2014). Thus, it is important to ensure that students understand the reasoning behind the mnemonics and not just the procedures for using them. Mnemonics work to get students to surface-level understanding, but we cannot leave them there. As Jeon (2012) notes, simply memorizing the order of operations through a mnemonic such as PEMDAS, or Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally, does not mean that students know how to use the information.

Mnemonics are especially helpful with the vocabulary of mathematics. For example, the fact that both denominator and down start with the letter d is helpful to remember that the denominator is the bottom number in a fraction. Some teachers extend this to connect the u in numerator with the word up. This mnemonic does not replace an understanding of what the numerator and denominator mean; it simply helps students place the labels correctly as they work with the terms.

A challenging set of vocabulary in measurement is the metric system prefixes. One common device for helping learners sequence them correctly is King Henry Doesn’t Usually Drink Cold Milk. The first initials of this sentence correspond to the prefixes kilo-, heca-, deca-, unit, deci-, centi-, and milli-. Students must still know the prefixes and how they correspond to the scale of the unit. In addition, they have to distinguish between the two d prefixes (deca-, or ten times, and deci-, or one tenth). Using understanding (decimals involve units smaller than 1) rather than depending on memorization makes sense and therefore makes it more likely for students to remember the distinction.

Conclusion

A strong start sets the stage for meaningful learning and powerful impacts. Teachers need to be mindful of where their students are in the learning cycle. Surface learning sets the necessary foundation for the deepening knowledge and transfer that will come later. But there’s a caveat: teaching for transfer must occur. Too often, learning ends at the surface level. But the challenge is this: we can’t over-correct in the other direction, bypassing foundational knowledge in favor of critical and analytic thinking. Students need and deserve to be introduced to new knowledge and skills thoughtfully and with a great deal of expertise on the part of the teacher. And teachers need to recognize the signs that it is time to move forward from surface learning to deep learning.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- Consider the mathematical discourse in your classroom. What opportunities do students have to explain and justify their thinking? What questioning strategies could you use to provide additional opportunities for students to show their deep learning through explanation and justification?

- Consider the important mathematical topics for your grade level. What is the surface learning phase of each topic? What would that look like in the uni-/multi-structural levels of a SOLO chart? What specific strategies might you use to help students develop surface learning for each of these topics?

- How do you use manipulatives in your mathematics instruction? Are students encouraged to use multiple representations as they work on mathematics collaboratively? What strategies can you use to make these tools more available to your students?