Adequate bookkeeping is a basic necessity both for intelligent estimating and profitable operation. Most earthmoving contractors start in business with some knowledge of how to get work done, but with little or no understanding of how to keep track of what they are doing.

Fortunately, it is not necessary for the contractor to keep the books personally. Large organizations have their own bookkeeping departments with full-time employees. A very small operator can hire an accountant or bookkeeper for part-time work, even for one evening per week or month, for a fraction of the money that will be saved. Even if the contractor can do the figuring, he or she will be wise to have a trained person check the books regularly.

A usual procedure for the small contractor is to hire a bookkeeper to make up a system, and to train him or her or an employee in using it. Daily entries and rough work are done by the contractor, and the bookkeeper makes periodic inspections of the records, posts items to the proper accounts, balances the books, and calls attention to mistakes and omissions. The frequency of the book-keeper’s visits will depend on the volume of work, and upon the care and competence with which the contractor keeps the books.

Books should be kept on a double-entry system, in which a record is made of two sides of each situation or transaction. For instance, a sale might result in the receipt of cash; therefore both the receipt and the sale are entered, and the books are “in balance.”

The checking account is usually the basis for the books and records. Entries are made on the stubs and/or in a separate book, to correspond with both bank deposits and checks written. The figures are reconciled with the bank statement monthly. In this manner each month is put into balance.

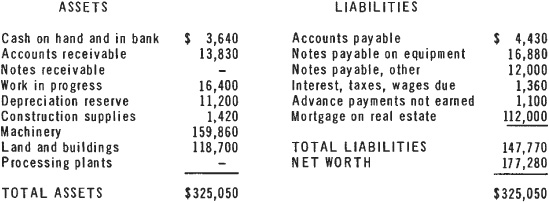

Balance Sheet. The balance sheet shows what the business owns and what it owes. An individual owner of a business that is not incorporated may include the nonbusiness property and debts. It is better practice to keep them separated as much as possible.

A contractor’s balance sheet might include the items in Fig. 11.1.

Equipment plays an important part in the company’s financial picture, so their managers must understand how their equipment decisions affect the balance sheet. Several financial ratios figured by use of the balance sheet measure company performance, liquidity, profitability, leverage and efficiency.

A current ratio, which is current assets divided by current liabilities, is important from an equipment point of view because, if a new piece is paid for with cash, it strains both working capital and the current ratio.

Leverage is the debt to equity ratio. It is found by dividing the total liabilities by the total net worth. A value of 3 or less is considered acceptable. The fixed asset ratio is the net fixed assets divided by the total net worth. The assets may be owned by lenders whereas the net worth is the company owners’ equity. Most heavy and highway contractors have fixed asset ratios over 50 percent.

Net worth is the amount left after subtracting total liabilities from total assets. It is listed as a liability in order to balance the two columns, and because it may be said that the business owes this amount to its owner or owners.

Day Book. Every contractor should keep a daily record in a book of what he or she does. It should show jobs worked, labor time, machine time, services provided, and materials used. Definite figures in feet (meters), yards (cubic meters), tons (kg), hours, and/or dollars are best. Such a record is easier to use than a collection of sales and job tickets, that are likely to get mixed up or lost. However, these tickets should be kept also, at least until payment for the work is received.

The day book may also serve as a diary for nonbookkeeping matters, such as important contacts with customers; promises of work and material to customers or from subcontractors or suppliers; important difficulties with weather, footing, breakdowns, or employees. It should record money spent, at least if it is in cash.

Such a daily record provides data for settling disputes about work done, payroll, and other matters, keeping track of work in progress and materials used, for obtaining adjustments in insurance rates, and backing up income tax returns.

Other Records. Contractors, like everyone else in business, must fill out forms for income tax for themselves and for withholding and social security for the employees. The contractor will probably have to keep track of sales and use taxes, fuel taxes, compensation insurance, and perhaps truck mileage.

Other records will depend on the volume and variety of business, and how much he or she believes in paperwork. Records can get too numerous and too detailed, but in the construction field they are usually too few and too carelessly kept.

Ownership Costs versus Operating Costs. These costs all have to be known for the success of a job, but the ownership costs have to do with finance and accounting whereas operating costs depend on how many hours the equipment or the job is ongoing. The various costs included in each category will be discussed and covered in the following sections.

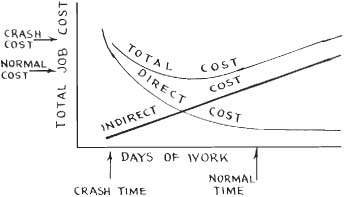

It is customary to divide contractors’ costs into overhead and operating expenses. Overhead, often miscalled “fixed cost,” may be divided into overhead and job overhead.

Overhead. Overhead is made up of costs which do not vary immediately or directly with volume or type of work. It may include the following items:

Drawing accounts, or living expenses, of owner or partners

Management and supervision—salaries of executives, engineers, superintendents, and foremen

Office rent, payroll, and supplies

Interest paid on loans, or charged against capital investment

Insurance for fire, theft, and liability if paid on the ownership of equipment and premises

Ownership taxes on land, equipment, and other capital assets

Depreciation

It is better to base the overhead cost recovery on the revenue generated by the equipment or the job rather than on the cost of the equipment or the labor. Then, if the job generates more than it was expected to, the overhead cost recovery rate will be less per unit produced.

Job Overhead. This heading may include any of the overhead items which are increased to take care of a particular job. When a contractor takes on a big project, the office and supervision force may be enlarged several hundred percent for its duration. This increase, arising from the one job, can justifiably be charged against it.

If job conditions require providing guaranteed pay, meals, rooms, or services to field employees, such expense may be labeled overhead, operating, or job overhead.

Job overhead may also include a proportion of home office overhead.

Operating Costs. This heading includes

The field payroll of employees hired by the hour or day, or for the job

Payroll taxes

Liability and compensation insurance based on payroll, work, volume, or job conditions

Machinery fuel, lubrication, maintenance, and repair

Machinery rental, delivery, and changing rigs

Expendable supplies

Borderline Costs. It is often difficult to classify particular expenses, to decide just which account should carry them. As long as the contractor is consistent, he or she can list them very much as desired. However, following accepted practices makes it easier to keep bookkeepers, and to explain matters to banks or bonding companies when it is necessary to do so.

Personal expenses. The contractor who runs his or her own business should keep books sufficiently to distinguish between business and personal expenses. However, he or she should bear in mind that these come out of the same pocket, and that living costs are part of business overhead to the extent that it is up to the business to provide money to cover them.

It is common practice for owners to draw a fixed amount, and to consider this to be the only personal charge on the business. However, if personal expenses are in excess of the drawings, and the difference results in running up bills, these will ultimately have to be paid by the business, and might better be considered a charge against it from the first.

If personal expenses are not closely accounted for, a one-person business which is profitable in itself may go steadily downhill, without the proprietor’s ever understanding why.

Importance. An important consideration for a contractor or a pit operator is the amount of capital required to carry customers’ accounts. In most localities it is difficult or impossible to work on a cash basis. Even when the primary business is selling a commodity in great demand, as gravel in a gravel-scarce area, and operations are started successfully on a cash-for-each-load formula, good customers have a way of working away from it through a series of steps, such as pay after several loads, at the end of the day, at the end of the week, and at the end of the month, to a regular charge account, perhaps tying up thousands of dollars for long periods. Losses on jobs, or difficulty in collecting accounts, may change a well-heeled customer into a slow-paying one.

Credit granted to one makes it triply difficult to refuse it to others.

It takes more backbone, or perhaps uncooperativeness, than is possessed by the average contractor to resist this technique of opening and increasing accounts. Also, it is often true that an enterprise cannot maintain a profitable volume except on credit, particularly if competition is severe.

The contractor who does small and medium-size jobs for a number of different customers has no choice but to extend credit. Insistence on cash in advance or even on payments during work usually means the loss of too many jobs.

Receivables not only tie up a large amount of working capital, but include a probability of bad-debt losses. These can be minimized by good judgment in extending credit and skillful collection methods, but they cannot be entirely avoided.

A bank is usually willing to lend money on receivables. If the account has a good credit rating or local reputation, it may advance the full amount, less a discount which serves for an interest payment, on the understanding that any money received from that customer goes directly to the bank. Or a certain portion of the total amount of receivables may be lent on a regular interest-bearing note.

The cost of such discounts or interest, and an allowance for uncollectible accounts, should be figured into the prices charged for material and services.

Offering discounts directly to the customer for cash or prompt payment is helpful in bringing quick money from good accounts, but is not very effective with those who are really hard up, and who constitute the major problem.

If a business is run partly with owned machinery, and partly with units rented from others, an over-large or doubtful account with a contractor may be tactfully collected by hiring the customer’s machinery until he has worked it off. Sometimes an arrangement is made to pay the customer partly in cash to enable him or her to keep up with the payroll, and to apply the balance to the bill.

Liens. A contractor or subcontractor can usually file a lien for an unpaid bill against the property on which the work was done. Such a lien stays in force for a number of years, and must be paid when the property is sold, mortgaged, or remortgaged.

In most states it is necessary to file a lien quite soon after completion of the work. The contractor or supplier must be aware of the local time limitation, and not allow an unpaid account to run until it is too late.

An old account can sometimes be brought up to date for lien purposes by making one more shipment of material, or performing one more service for which a charge can be made, as it is the date of the last item that determines the last date for filing.

Filing a lien does not prevent a contractor from taking other collection action, such as a lawsuit or attachment of other assets.

Bonds. Government and government agencies can usually be depended on to pay their bills, although they are sometimes slow and they may dispute amounts. But a subcontractor may have to be careful that the general contractor does not collect without paying out.

In almost all public jobs, and in many large private ones, the general contractor must put up a bond. This usually means that a responsible insurance company guarantees that the contractor will complete the work and pay all suppliers and subcontractors. If the contractor fails to pay any bill incurred on the job, the creditor can collect from the bonding company.

However, claims under bonds must be filed very promptly, often within 90 days of the date of the work, or protection is lost.

Most losses due to late filing of liens and claims under bonds are due to originally friendly relations between the parties, so that collection of the account is not handled in a businesslike way.

Work in Progress. A contractor may tie up substantial amounts of cash and credit in jobs before he or she is able to even ask for payment. On small jobs he or she may have to wait until the work is finished, on big ones there is usually an arrangement by which the contractor is paid in installments as the work progresses.

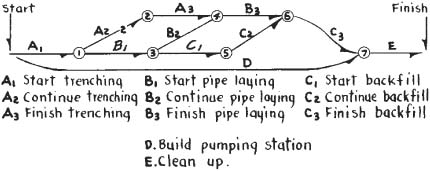

Installments may become due on completion and approval of parts or stages of the work, as a building contractor may receive a first payment when the foundation is completed, another when framing is done, and so on. The owner, in turn, may receive installments on the mortgage loan at such times.

In highway and other large heavy construction projects, a number of different stages may be worked at the same time. Rough grading and even clearing may be in progress on one part of the job while fine grading is being completed on another.

For this reason payments are made at regular intervals on the basis of measurements and estimates of the amount of work completed. Five or 10 percent of the amount due is usually held back until the end of the job. Payment may be made 1 to 20 days after the end of the work period, which is usually a month, but may be at shorter or longer intervals.

A schedule involving frequent and prompt payments reduces the contractor’s need for working capital. However, the contractor must have money on hand to keep going if a payment is delayed by disagreements or other difficulties.

The extent of such delays is largely dependent on the policies of the owner, and the owner’s reputation may enable the contractor to make proper allowance for them in advance.

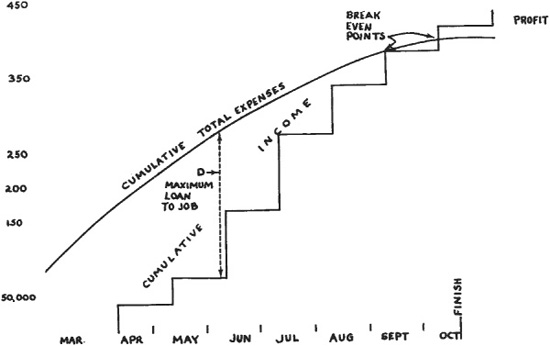

Cumulative Cost and Income. The graph in Fig. 11.2 shows a simplified example of the drain on a contractor’s resources during an installment-payment contract. The job is assumed to use no more than the contractor’s regular equipment, so that none need be purchased specially. Costs are actual expenditures, plus calculated machinery depreciation.

The cost curve shows the approximate amount spent at any time during the job. The stepped line indicates the total received in payments. The vertical distance between these lines first shows the amount “loaned” to the job, and later the profit.

FIGURE 11.2 Cash requirements of job.

The line “Maximum Loan to Job” is the greatest distance, and indicates the minimum amount of cash and credit that will be required to carry the job under normal conditions. If the May payment were smaller or the June payment were delayed, the line would be longer, indicating a need for more money.

Purchase of a machine, whether new or used, involves consideration of the type and amount of work in hand and expected, price and availability of suitable models, as well as operator skills, work habits, and personal preference. With the establishment of large national equipment rental companies offering lower rental rates, the alternative of renting construction equipment versus purchasing it should be considered.

Size. The arguments about machine size can appropriately be restated here. A big excavator is more costly to buy and to move, and requires more working space. It will dig more dirt in a given time, will handle harder and coarser formations, and will show a lower cost per yard (cubic meter) if it has space to work and is teamed with other equipment of proper size. It is harder to service and repair because of volume of fuel and lubricants used, and weight of parts. It gets stuck more easily and seriously in soft spots, but seldom hangs up on rough ground.

When space is restricted, ground is soft, or other conditions are unfavorable to the large unit, a small machine may not only work at a lower cost per yard (cubic meter), but may handle a larger volume as well.

Under conditions of equipment shortage, the large unit often has a proportionately higher resale value than the small one. There is a steady trend toward the use of bigger equipment, resulting in reduced labor expense per unit of production.

New or Used? Some successful contractors buy nothing but new equipment, while others buy only used pieces. Before the Tax Reform Act of 1986 in the United States there was a tax incentive to buy new capital equipment. Now, with the ever-increasing cost for new equipment, more contractors resort to buying used equipment, or rent (short-term) or lease (long-term) new equipment. In general, but not always, a new machine will have less mechanical trouble, and will receive better service from the dealer. It is more costly in purchase price, and in percentage of loss when sold. It has advertising or prestige value. It may be difficult or impossible to secure in the make, size, and model wanted within a reasonable time.

A purchaser of used equipment should have a good knowledge of mechanical condition and current values, and must be alert for liquidations, auctions, and other forced sales where good values can be obtained. Considerable time may be required to find a particular make and model at a good price, and haste may make it necessary to pay too much. On the average, repairs will be more costly and service less satisfactory than on new units.

The expert buyer of used machinery is often able to sell the purchases at a profit, sometimes obtaining considerable work from them first. The average buyer, however, will seldom accomplish this, and is liable to be stuck with worthless machines now and then.

Primary production machines such as excavators and wheel loaders are replaced about every three years with a new generation of equipment that significantly outperforms its predecessor. Firms competing in a market that endeavors to constantly improve quality at low cost can not afford to hang on to key machines through two or three rebuild cycles. If they do not upgrade production units regularly, their competitors using new machines will be able to outproduce them.

Cost. A contractor should figure the cost of an intended equipment purchase in two ways—total outlay of cash and credit involved in buying the machine and putting it to work, and the relationship between its cost of ownership and operation and the money it can earn.

The expenditure, particularly the cash down payment, is the most important figure to the contractor with limited capital, but may be merely a factor in considering long-term costs for the large or well-financed operator.

FIGURE 11.3 Example of purchase cost, 2-yard (1.5-cu.m) track loader.

Care should be taken to include in the estimated cost all expenses involved. These may include list price, taxes, delivery to the freight station and then to the job or yard; extra front ends or other units to adapt the machine to different types of work; accessories such as cabs, lights, spare tires, parts, and special tools; repairs or alterations necessary immediately; and allied equipment required to get full use of the machine.

Some of these items are self-explanatory. Immediate repairs are required only on used machines and include such items as replacement of worn tires or tracks, mechanical repairs, engine work, or complete overhaul.

Alterations may be changes made to adapt to overloads or special work, or may be necessary to correct mistakes or omissions of the manufacturer. They can include fishplating and other types of reinforcement, building up wearing surfaces with hard steel, and adding safety guards.

Allied equipment might be a trailer to carry the machine, ramps for loading it, and different sizes of excavator or hauler to match its size.

It is also advisable to add up the interest or finance charges that will be incurred in making the purchase. As these are not actually part of the price, they should be added after the original cost figures are determined.

For example, if a contractor decides to replace an old loader with either a new or a used 2-yard (1.5-cu.m) machine, he or she might study the comparative costs by setting up figures such as those in Fig. 11.3.

When contractors buy a piece of equipment at a fair price, they do not “spend” the amount they pay. They invest it. They exchange their money for something of equal value.

But the value of machinery starts to decrease as soon as it is delivered, because of use, wear, weathering, and passage of time. This decline in value represents the true spending of the invested money, and it is entered in the books and deducted from taxable income as an expense—depreciation.

It would be expensive and unsatisfactory to have a machine appraised every year to determine how much it had depreciated. It is also necessary to estimate in advance the rate of depreciation, as it is an important factor in establishing the price to be charged for the machine’s work.

Depreciation, also known as accelerated cost recovery, is therefore calculated in advance according to various formulas. Each of them provides a basis for balance sheets, profit and loss statements, and income tax. Annual depreciation is converted to an hourly figure for estimates and cost records.

More simply, hourly depreciation is the cost of a machine divided by the number of hours that it is expected to work.

Useful Life. Depreciation schedules must be based on the number of years the equipment is expected to be in service. Its useful years depend on the type of equipment, the class of work it will do, how much of that work it does, the care it receives, industry standards, and income tax decisions. At best, the time selected represents only an informed guess.

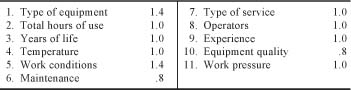

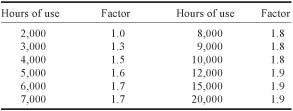

Bulletin F was the United States Internal Revenue Service’s guideline to equipment life for many years. Extracts are shown in Fig. 11.4. It has been retired as a guide, but may still be used as a reference and basis for discussion.

FIGURE 11.4 Depreciation periods from Bulletin F.

FIGURE 11.5 Guideline for depreciation periods.

There is now a class life setup, with 5, 7, or 10 years as life periods for the contractor, shown in Fig. 11.5.

Schedules calling for more increased early depreciation than is allowed under the declining-balance method are likely to be disapproved.

Used equipment may be given the same depreciation period as if it were new, or any shorter period that appears to be reasonable.

Fast Writeoff. It is considered to be good practice to depreciate equipment at the fastest possible rate. This is called fast writeoff. It permits charging the largest proportion of costs against the machine when it is new and best able to carry the burden, and when it is doing the specific work for which it was bought.

Fast writeoff also keeps the book value of equipment down near its real value.

The most important advantage of fast writeoff is related to income tax. The faster the depreciation, the greater the deduction that can be made now, and the less to be left for an uncertain future. However, this expected advantage might turn out badly, as a contractor may waste the heavy depreciation on unprofitable years, and not have the deductions in later profitable periods.

Capital Gain. If a machine is sold for more than its depreciated value, the profit is a capital gain that is generally taxed at less than the rate of ordinary income, while depreciation is deductible at the full rate. A substantial tax saving may therefore result from a fast writeoff that overdepreciates equipment. The U.S. Internal Revenue Code now allows an equipment exchange provision that saves money in the turnover of a piece of equipment for similar replacement.

Salvage Value. This is the value of a machine after it is fully depreciated. It may be the actual sale price, or the value it might be assumed to have to the contractor when it is theoretically overage and worn out.

Salvage value varies greatly with the type of equipment, its condition, its scarcity, and the local prosperity of the construction industry. Sometimes it is only a few dollars per ton for scrap, at other times, but more rarely, as much as 60 percent of new cost. It is usually estimated at somewhere between 5 and 20 percent of purchase price.

The declining-balance depreciation method leaves a small salvage value automatically. With other methods, any estimated salvage is subtracted from purchase price before figuring depreciation.

Amounts allowed for salvage can be adjusted to simplify arithmetic. For example, if a machine with a 5-year life cost $16,346.93 and might be expected to bring $1,000 to $1,500 salvage, the salvage value could be taken as $1,346.93, leaving an even $15,000 to be depreciated.

Internal Revenue sometimes insists on deducting salvage value before figuring depreciation, and sometimes does not. It is better to depreciate the full purchase price when possible. This simplifies bookkeeping and makes an allowance for a probable increase in replacement cost, a matter that will be discussed below under Price Increases.

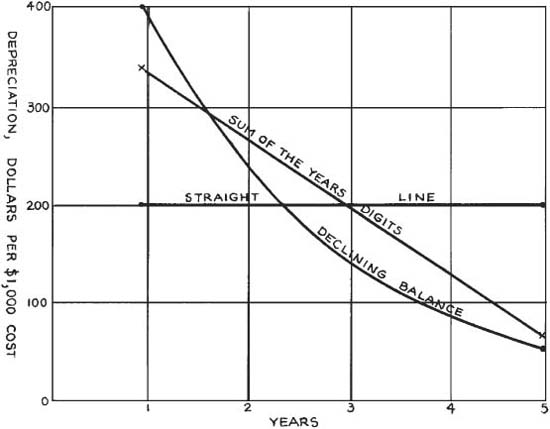

There are two official tax methods of computing depreciation for periods of 3 years or longer. These are known as the straight-line and the declining-balance methods. For short periods of less than 5 years only straight-line is used.

Information in regard to taxes may become obsolete while it is being printed. It should always be checked before use.

Straight Line. Straight-line is the simplest method, gives a uniform basis for figuring machine costs, and avoids complications in reserve for depreciation. The only thing it lacks is fast writeoff.

The cost of the machine, less any salvage value, is divided by the number of years it is expected to be useful. The resulting figure is the annual depreciation. It is the same amount each year.

Declining Balance. This method is based on the total cost of the machine. The maximum depreciation rate is twice that allowed by the straight-line method, but it is applied only to the value at the beginning of the year, which is the original cost less all depreciation that has been deducted.

For example, a $20,000 piece of equipment with a 5-year useful life would depreciate 20 percent or $4,000 each year under the straight-line method. With declining-balance, depreciation the first year would be 40 percent of $20,000, or $8,000, the second year 40 percent of $12,000, or $4,800, the third year 40 percent of $7,200, or $2,880. At the end of the fifth year a salvage value of $1,555.20 would remain.

If the machine’s life expectancy were 8 years, the depreciation each year would be 25 percent of the value at the beginning of the year.

Sum-of-the-Years Digits. This method, formerly recognized by the Internal Revenue Service, is based on cost less estimated salvage value. The number of years of useful life is taken as the first figure in a descending series, which for a 5-year period would be 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, and for 8 years 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. The series is added together, giving 15 for the 5-year period or 36 for 8 years.

A fraction is made by placing the number of years of life from the beginning of the year over the total obtained by adding all the numbers in the series together. This is multiplied by the cost to give the depreciation for the year.

On a $20,000 machine with a 5-year life, first-year depreciation will be  (or ⅓) times $20,000, or $6,666.67. In the second year, machine life from the beginning of the year is 4 years, so the fraction is

(or ⅓) times $20,000, or $6,666.67. In the second year, machine life from the beginning of the year is 4 years, so the fraction is  , or $5,333.33.

, or $5,333.33.

The whole series of deductions would be  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , totaling

, totaling  , or the entire cost.

, or the entire cost.

On an 8-year basis the first-year depreciation would be  (or

(or  ) of the cost, or $4,444.44. The next year would be

) of the cost, or $4,444.44. The next year would be  , and so forth.

, and so forth.

Choice of Method. Declining-balance and sum-of-the-years-digits formulas are designed to put more of the depreciation at the beginning of the life. They provide the fast writeoff that is liked by industry, and they conform most accurately to the actual loss of value of equipment in normal markets.

However, they cause problems in converting to an hourly basis for use in figuring job costs. Using a different rate each year would be difficult. If there were several machines of the same model but different years, the attempt to charge different prices for them would be confusing to the bookkeeper and aggravating to the customers, and would make accurate pricing of a job almost impossible.

The contractor should use straight-line depreciation in figuring hourly costs, regardless of the method used for income tax and annual reports.

Figure 11.6 shows graph lines for these three types of depreciation, and Fig. 11.7 gives annual depreciation figures per $1,000 of cost. This table can be applied for calculations on any price of machine, by multiplying by its cost divided by 1,000. That is, for a machine costing $15,500, the table figures are multiplied by 15½.

Hours of Use. A contractor may elect to depreciate machinery on an hourly-use basis, without regard to calendar time. The contractor may buy a bulldozer for $25,000 and expect to use it 5,000 hours. He or she will charge $5.00 per hour against its jobs, and at the end of the year depreciate it by $5.00 times the number of hours it worked. If it were busy 600 hours, depreciation would be $3,000; if working time were 1,400, the year’s depreciation would be $7,000.

Units of Work. A machine’s production may be used as a basis for depreciation, if it can be measured accurately. A mine may buy a 5-yard (3.8-cu.m) shovel for $900,000 in the expectation that it will work 20,000 hours and load 8,000,000 tons (7,280,000 metric tons) of rock and ore before it is scrapped. If business is good, it may work 6,000 hours per year; if it is very poor, the machine might be entirely idle.

Under such conditions annual depreciation would not be appropriate. Instead, the $900,000 value of the shovel might be divided by the 8,000,000 tons it is expected to handle, giving a depreciation figure of $0.1125 (11¼¢) a ton. Each year it is depreciated on the basis of the number of tons loaded.

FIGURE 11.6 Three depreciation methods.

FIGURE 11.7 Annual depreciation on $1,000 cost.

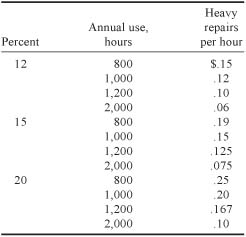

Tires. It is common practice to deduct the value of tires from the purchase price of equipment, charging them as operating expense and depreciating the balance as a capital investment.

The advantages and disadvantages of this approach will be considered later. It is subject to disapproval by the Internal Revenue Service unless the contractor can prove from records that such tires usually last 1 year or less.

Repairs as Capital. Repairs are considered an operating expense as long as they do not add greatly to the value of a machine. But major overhauls, particularly if done late in the depreciation years, may be considered to be a capital expense that must be depreciated over several years.

For example, if a contractor spends $4,000 rebuilding a $10,000 machine in the last year of its depreciation schedule, he or she may have to list the expense as a capital investment, and set up a new schedule for it.

Fully Depreciated Equipment. If a machine is kept beyond the end of its depreciation period, no further depreciation is charged against it. However, the hourly price for it should remain the same. The part of its earnings that formerly paid for depreciation becomes profit, one of the “hidden profits” that help to keep contractors in business.

However, this extra profit may easily turn into a loss because of high repair costs and too much downtime. It is not good business to run old machines unless they are in good condition.

Short-Term Use. Many contractors buy machines for particular jobs, and sell them as soon as they finish. Others have a policy of turning in equipment after a certain amount of use, to reduce maintenance and job delays and to have the prestige value of up-to-date machines. Cost estimates are then based on the difference between purchase price and estimated sales price.

For example, a contractor may buy a fleet of $240,000 scrapers for use in two seasons of about 1,200 hours each, after which they will sell for one-third of their cost. Each of them will depreciate $160,000, and that cost per hour will be $33.33. This would compare with no-salvage depreciation of $24.00 for 10,000 hours or $48.00 per hour for 5,000 hours.

When periods of use are to be very short, it may be cheaper and/or less risky to rent equipment. This will be discussed later in the chapter.

The contractor who intends to stay in business should set up a depreciation reserve, in which funds can accumulate to replace equipment as it wears out or becomes obsolete. This reserve may be a separate bank account, a fund maintained inside the regular account, or perhaps only a page in the ledger.

As depreciation is charged against a machine and deducted from income, it should be paid into the reserve. If emergencies prevent saving the actual cash, the amount should at least be entered as a liability so that it will not be forgotten.

Need for Reserve. Machines wear out and must be replaced. Money is needed for the replacement, and it should be provided by the machines as they work. Otherwise the capital invested in them is consumed and destroyed.

If whatever money it made has been eaten up, the contractor may not even have the down payment on new equipment. Without adequate books the contractor will find it hard to understand why he or she should finish a number of busy and apparently successful years without money to replace machinery.

Inventory and Reserve. When a machine is purchased, its value is listed as an asset under Equipment Inventory or some such heading. The depreciation is deducted from this each year, and added to the Depreciation Reserve. On a $16,000 machine with a 5-year life, the straight-line method would work out as in Fig. 11.8.

FIGURE 11.8 Inventory depreciating into reserve, 5-year basis.

Inadequate Depreciation. Most manufacturers recommend that construction equipment, aside from big loaders and special units, be depreciated on the basis of 10,000 hours of use in 5 years. But as we will see later, most contractors are doing all right if they work 1,000 hours per year.

On the recommended basis a $100,000 bulldozer would depreciate $20,000 per year and $10.00 per hour, and its price on jobs would be set accordingly. But at the end of a year, it might have worked only 1,100 hours because of weather, job delays, and repairs.

The jobs would owe the depreciation reserve $20,000 for the year, but the machine would have earned only $11,000 for this purpose. There would be a deficit in the reserve of $9,000, which would have to come out of profits, or if there were none, out of other funds.

If this machine use had been more realistically figured at 1,000 hours per year for 5 years, depreciation would be $20,000 per year and $20.00 per hour. In 1,100 hours of work in 1 year, the machine would have been able to provide the full $20,000 for the reserve, plus a $2,000 surplus for profit. The extra $10.00 an hour might make jobs harder to get, but if that is the actual depreciation, the contractor must charge accordingly or lose money.

If experience shows that the machine will last 10 years at the 1,000 hours per year rate, its schedule could be set up for 10,000 hours in 10 years, and $10.00 per hour. On this basis the 1,100 hours of work would pay the $10,000 depreciation charge, with $1,000 left over. But if the machine had to be scrapped at the end of 5 years, the reserve fund would be short $50,000.

It may seem to the reader that this is just a matter of juggling figures. But the figures are very real, and understanding them and arranging them properly may mean the difference between prosperity and bankruptcy.

A contractor who can really use a machine for 10,000 hours is justified in basing estimates on long use. But if he or she is getting only 3,000, 5,000, or 6,000 hours out of the equipment now, basing costs on longer use is foolish and dangerous.

Price Increases. Contractors share with all other users of modern machinery the problem of price increases. The price of any equipment is likely to increase during its life, so that the replacement cost is more expensive than the original cost. This arises both from a general rise in prices, and from improvements in equipment that add to its cost.

A properly kept depreciation account for a single machine will seldom contain enough money to buy a new one if the original unit is scrapped at the end of its calculated life. Other funds or loans have to be added to buy a replacement.

This difficulty may be partly or wholly overcome by figuring that the machine has no salvage value. Since it almost always has some salvage value, even if only for junk steel at $10.00 per ton, and is often worth a substantial amount if in good condition, its value plus the depreciation reserve may provide fully for a replacement of the same type and size.

Another hedge against price inflation is to increase the depreciation charge against the machine whenever its replacement price is increased, so that it is the same as for a new model.

For example, if a $20,000 machine were depreciated on a 5,000-hour basis, the hourly depreciation would be $4.00. If after 2 years the price of similar machines were increased by the manufacturer to $23,000, the depreciation charge against the old machine would be increased to $4.60. This is for internal bookkeeping only, and cannot be used on income tax returns.

This has the advantage of partially providing for replacement at an increased price, and of keeping prices uniform with new units that might be added.

Advance in prices to cover rise in replacement costs is particularly important for firms that obtain a substantial part of their income from renting out machinery.

Improvements may be made in equipment so that a new model is not strictly comparable to one 2 or 3 years old. However, the only point of importance in regard to upgrading the old model in price per hour is whether the changes produce an important increase in production. They often do not.

There are at least three different ways to consider an investment in equip ment. They are: initial, total, and average annual investment.

Initial Investment. This is the net cost—the total of cash paid and debts incurred to buy a machine. It causes a shift in the balance sheet, adding to machinery inventory by reducing cash and/or increasing liabilities. This could be called the market value method for covering the equipment cost.

At the beginning of each year the value is estimated and covered by the estimated hours the piece of equipment will be used that year. This method results in a higher charge in the earlier years but lower in the years nearer the end of the machine’s life

Total Investment. It is customary, although not particularly reasonable, to charge equipment with the interest on any cash invested in it. Also, property taxes and loss insurance are paid on the basis of machine value. This method could be called the amortization method which uses a discounted cash flow annuity calculation. It is the method banks and finance houses use. It will likely result in a charge slightly higher than with the average annual investment method.

Since a certain part of the initial investment is amortized—that is, paid off in depreciation charges—each year, the investment on which such charges are figured is reduced in a series of steps. For the first year it will be the purchase price, the second year purchase price less one year’s depreciation, and so on.

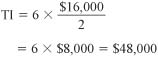

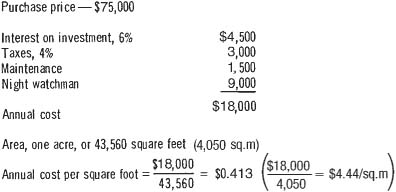

Such charges are most easily worked out for the whole life of a machine by using the total investment. This is found by adding the machinery inventory value for every year of the unit’s life. In Fig. 11.8 the total of the first column, $48,000, is the total investment for that machine.

Total investment (TI) may also be found by adding 1 to the depreciation period in years (DP, yrs), and multiplying by one-half the original cost. Stated as a formula, this is

TI = (1 + DP, yrs) × cost/2

For a $16,000 machine used for 5 years,

If interest were to be charged against the unit at 6 percent, the total interest for its life would be 6 percent of $48,000, or $2,880.

Average Annual Investment (AAI). This is a more realistic figure that averages the purchase cost over the years of machine life. It can be found by dividing the total investment by the number of years.

FIGURE 11.9 Average annual investment for $1,000 cost.

Average annual investment may also be obtained by multiplying the cost by the years of depreciation (DP, yrs) plus 1, and dividing by twice the years of depreciation. Stated as a formula,

Figure 11.9 gives the average annual investment for $1,000 purchase cost for the most used depreciation periods up to 25 years. To use this, multiply the figure appearing after the number of years of life by the number of thousands of dollars in machine cost.

Rates. Interest rates vary greatly with different types of loans, with the risk and bookkeeping involved for the lender, and with the general level of interest rates at the time the loan is made. They can be very confusing.

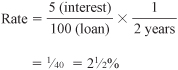

If a person borrows $100 and pays it back at the end of a year, plus $6.00 interest, the interest rate is 6 percent. If he or she keeps the money for 2 years and pays only $6.00 interest at the end of that time, the rate is 3 percent.

If the $100 is borrowed on a discount basis with the interest paid at the beginning, the borrower will receive $94 when the loan is made, and pay back $100 at the end of the year. Here the real rate is 6.38 percent (100/94 – 1).

On an installment loan with an advertised rate of 6 percent on the unpaid balance, the borrower will receive $100 and pay $106 in 12 equal monthly payments. The real interest rate is about 11 percent, as the average indebtedness for the year is only $54.16.

True interest rates can be found by dividing the amount borrowed into the interest paid, and multiplying by a fraction made of 1 over the time in years, or 12 over the time in months.

If $5.00 in interest is paid on $100 borrowed for 2 years, we have

If the term of the loan were 4 months, then

Interest on Equipment. As mentioned before, interest should be charged against a machine even if it is bought for cash. If the purchase is financed at a rate of more than 6 percent, the higher rate is charged, while if interest is less than 6 percent or if none is paid, the charge is kept at 6 percent. Interest is figured on a yearly basis on the average annual investment.

This custom does not conform to good accounting practice, and is in conflict with methods of treating money tied up in other ways.

Equipment Debt. There is good reason for charging interest on equipment purchase loans against the equipment, although a good case could also be made for charging it to general overhead. Carrying it as an equipment expense has the advantage of simplicity and of automatically identifying the source of the charge.

General Debt. A second case is to charge bought-for-cash equipment with the same interest rate being paid on open loans for general purposes. It should be considered that money borrowed for general business use is a general overhead item, and responsibility for it is shared by field, shop, and office equipment, materials on hand, cash in the checking account, accounts receivable, and work in process.

The value of owned equipment is usually much greater than the amount of the general debt. If a machinery inventory of $100,000 were charged with 6 percent interest because of a debt of $20,000, it would be paying $4,800 more than the cost of the interest.

If this equipment were charged with the actual interest, the $1,200 paid would be applied to the whole $100,000, so that interest would be at the rate of 1.2 percent. If the debt were carried by all the money-consuming items mentioned above, which might easily total $150,000, the effective interest rate would be only .8 percent.

No Debt. A third situation is to assign an interest charge of 6 percent to equipment, even though its owner pays no interest on any kind of debt. The idea is that the contractor could invest money elsewhere if he or she did not buy equipment. But the only investments that a contractor can make and still keep the money available in the business are savings accounts and short-term bonds, that might pay 5 percent or less.

It is of course both possible and likely that funds invested outside the business would fail to return 6 percent interest, and might be partly or wholly lost.

Equipment is not a bond or mortgage that justifies itself by paying interest. It pays its way by production. To saddle it with interest charges is to ask it to produce a profit before it goes to work. In this highly competitive business, such an arbitrary increase in its cost basis may make the difference between getting a job and losing it.

However, since assuming of interest charges is now a widespread practice in the industry, it will be taken into account in some of the cost calculations that follow.

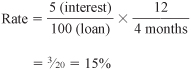

Installment Interest. The interest rate on an installment contract is found by dividing the total debt into the total interest.

Total debt (TD) is a figure that is similar to total investment. It is found by adding 1 to the number of monthly installments (1), multiplying by the loan, that is, the amount borrowed before interest, and dividing the result by 24. The formula is

The amount of interest is found by adding all the installments together, or multiplying their number by their amount, and subtracting the amount of the loan.

For example, $12,000 of a $16,000 purchase is financed in 36 monthly notes, 35 for $393.33 each and a final one of $393.45, totaling $14,160. Subtracting $12,000, we find that the interest totals $2,160. By the formula above, the total debt is $18,500. Dividing $18,500 into $2,160, we have .117, or an interest rate of 11.7 percent.

Some contractors want to know the interest rate of finance charges on the whole purchase price. If the above machine had 5-year depreciation, its total investment would be $48,000. This would be divided into the $2,160 interest, showing a rate of 4.5 percent on the machine.

If the machine is to be charged with 6 percent interest on the nonfinanced part of the investment, the total debt is subtracted from the total investment, and the remainder multiplied by .06. In this example, we would have $48,000 minus $18,500, or $29,500, multiplied by .06 to give an interest charge of $1,770. Added to the finance charge, this would give a total interest cost of $3,930 and an average rate of a little less than 8.2 percent.

It is worthwhile for a contractor to understand interest rates. The contractor will then have a clear picture of the extra expense involved in financing equipment, and may be able to save substantial amounts by being able to detect mistakes or fraud in papers.

The cheapest way to finance the purchase of a piece of equipment is to borrow from a bank on a straight time note at the regular rate of interest. Such a loan may be obtained by pledging collateral such as stocks, bonds, or accounts receivable. A substantial contractor may be able to obtain such a loan without putting up security.

Installment Plans. Most equipment financing is done on a straight-line installment basis, with a down payment of 20 to 40 percent (usually 25 percent) and the balance plus interest paid in equal monthly installments over a period of 1 to 5 years, with 18-month to 3-year terms the most common.

The finance or interest charge may be 10 percent per year on the original amount of the loan. That is, if $1,000 is borrowed to be repaid in 12 monthly installments, the interest is $100.00. If installments extend over 3 years, this charge is $300.00. It works out to an actual rate of around 19 percent, the higher cost being found on the longer terms.

Installment payments are secured by a chattel mortgage on the equipment, that is recorded in the town or city records. The borrower must be sure to have this canceled by filing a release from the finance company or bank when she or he has completed payments.

When the value of the equipment and/or the contractor’s ability to make the payments is questionable, the lender may ask for additional security, such as an endorser on the notes, or a mortgage on additional pieces of equipment that have no debt against them.

If loan installments are not paid on time, an extra charge may be made for each one that is delayed. The lender also has the privilege of demanding immediate payment of the whole sum if even one payment is unreasonably delayed, and may seize and sell the equipment to collect. Machinery sold in such proceedings is not likely to bring its full value, and the contractor may still owe a balance even after the equipment is lost.

Schedules may be made up to allow omitting payments in off seasons, usually three or four winter months. Such a provision will either make the other payments larger, or stretch them over more years. Most contractors manage to make regular winter payments with surplus from working months, collection of accounts, or short-term borrowing from banks.

Property Tax. The contractor must pay a variety of taxes, including real estate, personal property, excise, and payroll levies. Here we are concerned wit the personal property taxes payable on the assessed value of equipment.

This is entirely a local matter. In some states the local governments are permitted or required to tax machinery and other movable property in the same manner as real estate. This tax may range from 2 to 5 percent of the assessed value of the equipment, depending on the type of equipment, its costs, age, and condition. In other states or localities there are no property taxes whatever on construction equipment.

It is customary for estimating advice to suggest using the nationwide average tax of 1.5 to 2 percent of value in figuring ownership costs. However, in this case, average costs have little bearing on particular costs. Contractors must find out what taxes, if any, they will pay before they can use them in figuring.

The tax is usually low in country districts and high in cities, but it varies with local financial policies. A high rate with a low assessment may mean a lower tax than a lower rate and full-value assessment.

Assessments may or may not follow the depreciation schedule of the contractor. But it is a general practice to assess a machine for at least 20 percent of its cost as long as it looks as if it might run.

Registration. Highway vehicles must have registration plates. The cost is moderate for cars, pickups, and jeeps, but may be very heavy for big trucks.

In most states this tax is based on weight and/or capacity. In some there is an additional mileage charge. There is no close relationship to purchase price, so that it cannot be handled on a percentage basis.

Registration is an overhead expense, mileage an operating item. Both are added to other costs in setting a price on a truck’s services, but this must be done on an individual basis.

Liability Insurance. Highway vehicles are not covered by a contractor’s general liability and property damage insurance. They have special coverage at much higher rates.

This is another ownership expense that is not related to purchase cost. Its amount is affected by vehicle weight, type of use, accident record of the owner, and miles driven.

Loss Insurance. The cost of insurance against fire, collision, upset, and theft is an ownership cost that is charged against each piece of equipment in proportion to its value. There are equipment theft prevention systems available that should reduce the insurance cost if one is installed.

The charge for insurance of this type is known in insurance circles as a judgment rate, as it is set for each locality or contractor according to the insurance companies’ judgment of the risks involved.

The rate for fire, collision, and upset in a combined extended-coverage policy is usually about 1 percent of the actual value of the equipment, for the small contractor with a few machines used in miscellaneous work. Very large earthmoving or construction projects, such as the St. Lawrence Seaway sections, may be given a rate as low as ½ percent. This is in spite of the fact that some of the machines work under very dangerous conditions, as the extreme risk positions are outbalanced by many behind-the-lines units working under safe and stodgy circumstances.

The highest rates for this coverage may be 1½ to 2 percent. These are charged where the job conditions are more dangerous than average, or where the contractor is considered to be careless or reckless in management.

Theft insurance may be written into these policies as an extra coverage. With a $50.00 deductible clause it may be free in country districts where stealing is rare, and up to ½ percent of value in cities. One-quarter percent is a usual charge. Companies may refuse to issue theft coverage at any price in certain cities or areas.

Premiums are usually charged on the basis of the contractor’s valuation of his or her equipment, as long as the contractor follows any reasonable and consistent system of depreciation. Each year, or at more frequent intervals, the contractor sends the insurance company a list of equipment, showing date of purchase, original cost, and present value. The premium is charged as a percentage of the total.

Caterpillar offers the Cat Machine Security System (MSS) on individual machines and it has proven successful in stopping thievery of those machines.

Topcon’s Tierra device on a piece of equipment provides for bidirectional communication and data sharing with a central base and remote computers. With Internet connections and a global positioning system (GPS) it shows the locations of pieces of equipment on a given jobsite. If a piece unexpectedly goes outside the jobsite an e-mail or text message alert is sent to people monitoring that job to prevent a theft.

If a unit must be replaced because of insured loss, payment is made on the basis of the actual value of similar equipment in the locality at the time of loss. However, the company has the right (which it may not use) to refuse to pay more than the value of the machine stated in the policy schedule.

Therefore, if the value stated in the policy schedule, which should be the same as in the equipment inventory, is more than the actual value, the premium on the excess might be wasted money. If schedule value is less than real value, the equipment is not fully protected against complete loss. However, complete loss is rare except in very small units, and most payments under these policies are for repairs.

Storage. It is unusual for there to be any storage cost directly chargeable to a piece of equipment. Most contractors have at least one home lot, often near their repair shop. This has room for a number of pieces of equipment. The rest are kept out on jobs, where they must be to earn their keep. They usually can be left on or near a job until they are moved directly to the next one.

Ownership and maintenance of a storage yard are strictly a general overhead expense, as this facility is not expanded and reduced with purchase or sale of machines.

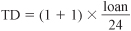

However, a contractor who wants to charge it against individual machines can do so by finding the annual cost per square foot of the yard, and charging each machine according to the number of square feet it occupies when it is there.

For example, a piece of industrial land in outskirts of a city might cost $75,000 per acre ($18.50 per sq.m), including a graded and stabilized surface. It might be assessed at full value, with a tax rate of 4 percent. As this is not an income-producing investment, 6 percent interest might be charged against it. Cost per square foot ($/sq.m) might be worked out as in Fig. 11.10, to $0.413 ($4.44/sq.m).

A large scraper might occupy a space 50 feet (15.2 m) long and 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, or 600 square feet (55.7 sq.m). Allowing 400 more feet (122 m) for maneuver space, its requirement would be 1,000 square feet (93 sq.m). Annual cost would then be 1,000 × .413, or $413. This machine might cost about $50,000, and have an average annual investment of $90,000, so storage would be nearly 0.5 percent of value. A shovel of similar value would need less than half as much space.

It is unusual to store large pieces of equipment indoors. If it is considered necessary to do so because of vandalism, extreme cold, or other conditions, the cost may be as high as 5 percent of investment.

FIGURE 11.10 Cost of storage yard.

FIGURE 11.11 Ownership costs per $1,000 average annual investment, without depreciation.

Summary. Figure 11.11 shows the normal range in ownership costs or carrying charges, on a per year per $1,000 of average annual investment basis.

There is a wide range, from .5 to 23.5 percent. Most estimating advice recommends using 10 to 13 percent. Ten percent is an easy figure to remember and to use, but 8 percent is likely to be more accurate if interest charges are limited to those actually paid.

The contractor or estimator should not rely on any general average of costs, but should find out what they really are for her or his own situation.

Trimble’s Connected Community. (TCC) is an online collaboration tool that enables construction contractors and clients to manage project data, by keeping track of the project and communicating with employees and others who need to know the information.

One of TCC’s important features is its file-management system, where an equipment fleet manager can organize and analyze equipment data, such as travel times, fuel costs, and down time. That data can be shared by anyone else, say, an equipment operator who has access to the community via the Internet.

Another important use of the TCC is to upload a new design change that needs to go to the field as soon as it is approved. With approval the field supervisor can have the change downloaded and made available to a loader, excavator or whatever equipment needs the information.

TCC can collect digital photos of the project site on a daily basis for progress reporting. It can also provide a calendar of project meetings and deadlines, and equipment availability.

Annual depreciation and other ownership costs are converted to an hourly figure as a basis for charging out equipment time. At first glance this appears to be easy. It is only necessary to divide the annual costs by the hours worked per year, or the total work hours by the total costs.

For example, a machine whose fixed costs during a year are $3,600 and that worked 1,200 hours in that year will show fixed cost per hour of $3.00. Or if its total costs for life are $18,000 and its total hours of work are 6,000, the figure is still $3.00.

But it is difficult to settle on the number of hours that equipment can be expected to work, as that is affected by a number of variable factors.

This discussion will be limited to the problems of those contractors who work a single shift and are subject to delays in weather, getting jobs, and keeping equipment running—which includes most of them. It will also deal chiefly with the contractor’s first-line equipment that has work most of the time.

Maximum Use. Estimating advice from manufacturers usually recommends a basis of 2,000 hours per year, and a 5-year life. But most construction work is done in 8-hour days and 5-day weeks, with shutdowns for a minimum of six holidays. The maximum number of hours that can be worked in a year is 2,040 on this program. It is usual to lose an extra 5 days in special holidays or shutdowns, reducing the year to 2,000 work hours.

Bad Weather. Weather often makes outdoor heavy construction work impractical or impossible. One New England state highway department estimates that weather and ground conditions permit the following number of days per quarter:

These figures are on the optimistic side for the area, and they are based on working Saturdays when necessary to make up for rained-out weekdays.

A 5-year survey by the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads indicates that the nationwide average of shutdowns on highway jobs that are due to weather amount to about ⅕ of working time.

The southeast and south central states do not have to stop work for snow and ice, but they do have rain that may have equally bad results. Only in certain areas in the southwest can the 2,000-hour figure be even closely approached on a permitted-by-weather basis.

Maximum working hours are affected by job conditions. Work in rock, gravel, or sand, or on surfaced haul roads, can continue under conditions that would make a job in loam or clay impossible. Pressure of a deadline can make it worthwhile to work under very unfavorable conditions, just in the hope of making some progress.

The type of equipment also affects lost time during weather. A dragline piling wet soil may not be affected by rain unless it is flooded out. Crawler equipment keeps going after rubber-tire types give up. Vehicles may carry part loads where full ones would make them bog down.

If there is a lack of any specific information to the contrary, the estimator should allow for a loss of 20 percent of annual working time because of unfavorable weather.

No Work. Equipment can work only when there is a job. This means not only work in general, but for the specific machine under consideration.

Some contractors find little difficulty in keeping busy all working season or all year; others must get through frequent or prolonged periods of insufficient work or no work. The differences depend on construction activity in the area, the specialties of the contractor and the demand for such specialties, the aggressiveness and reputation of the contractor, and a factor of luck in bidding and in selling services.

Even when a contractor has a job, it may not be for all the equipment. The contractor may even have to leave his or her own machinery idle and work with hired equipment at a job that is outside the regular field.

As a general average, a capable contractor may hope to keep the first-line equipment busy on jobs about 80 percent of the time that weather permits working.

Downtime. Even when weather is good and work is available, a machine may not be able to work because of need for repairs to itself or to another unit whose operation is necessary to it, or as a result of shortage of materials, strikes, or other causes. This nonworking time on the job is called downtime.

Studies conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, now the Federal Highway Administration, show that equipment downtime on the job is likely to be between 20 and 65 percent of working time, with age and condition of equipment and competence of management being the most important factors in the variation.

Most of this downtime is considered to be working time (if the machine were rented, rental would be charged), but the owner must take its loss into consideration in figuring the work gotten out of the machine.

Such downtime is in addition to the small delays that are taken into account by using a 45- or 50-minute work hour.

Work Hours Summary. A rule of thumb for the hours that heavy equipment will work is to assume a one-shift, 2,000-hour year; take off 20 percent for bad weather, leaving 1,600 hours; take off another 20 percent for lack of work, leaving 1,280 hours, and another 20 percent (an absolute minimum) for lost time on the job, leaving a net working time of 1,024, or say 1,000 hours. This is the Rule of the Three Twenties.

Like all rules of thumb, this can be way off. But before it is discarded, the estimator should study his or her own conditions carefully to see if they are really better, or quite possibly worse.

This rule does not apply to mines and pits, that may work three shifts on a 7-day week, and have up to 8,600 scheduled machine work hours in a year. They do not ordinarily lose as high a proportion of this time.

A number of machine cost computations in this book use a 1,200-hour year as a basis. This is due partly to the fact that many contractors consider the lost time on the job to be working time, and partly to the longer-than-5-year life enjoyed by many machines. That is, the hourly costs come out nearly the same whether the machine is used 1,200 hours per year for 5 years or 1,000 hours for each of 6 years.

Equipment Training. The John Deere company has what they call an Equipment Training Simulator introduced in 2008. It is used for training operators of backhoes and complements their simulator for four-wheel-drive loaders. Another simulator will be introduced for motor graders in 2009.

Eight highly detailed and realistic lessons teach the proper operator technique, machine control, and safe operation on a virtual job site.

Equipment Life. The useful life of construction equipment varies depending on how it is used and maintained, also how long the contractor wants to keep using it as opposed to replacing it with a new piece. A study conducted for Construction Equipment magazine in the 1990s found that the average life of major equipment kept in a contractor’s fleet was about 7,000 hours. Figure 11.12 shows the range of useful hours to replacement for key types of equipment according to the study.

A contractor might use a fleet information system (FIS) computer program to help decide on the equipment life for a piece or set of equipment he or she owns. The program calculates what-if costs based on current information. The computer software projects ownership and operating costs of a machine being analyzed for replacement. Estimated downtime is calculated based on the reliability and life averages for similar equipment. Cost and life data is drawn from the database maintained with the firm’s fleet management records.

The FIS system then balances costs with the expected revenue the machine will earn, based on its past averages of usage and revenue earned. The system also estimates residual value expected at the time of replacement, including any repairs that might have to be made.

The result is an expected cost per hour for a rebuilt machine, which can be compared to the costs for buying and operating a new machine. If the decision is to retire the old machine, the equipment life of that machine has been determined.

Equipment Life Based on Repair Cost. It has been shown that the life of a piece of equipment depends on cost of repairs to the machine. The cost of those repairs per hour is at a minimum after 7,000 to 10,000 hours of use depending on the type of equipment and its use. Then they jump because of requirements for a new set of tires, hydraulic pump, rebuild of the transmission, or maybe a new engine. That time of minimum cost of repairs in the life of a piece of equipment might be called its sweet spot.

FIGURE 11.12 Useful life targets for key machines.

Auxiliary and Emergency Equipment. Most contractors own a certain amount of equipment for which they find little use. For example, a general contractor who seldom does rock work may keep a compressor and drill to have them immediately available if required.

If a contractor owns a compressor or pump that is used only 50 hours per year, the depreciation per working hour is 20 times as much as that of another contractor who uses hers 1,000 hours. The depreciation on such a unit must be charged to general overhead, as the machine cannot hope to earn it.

Equipment Investment Analysis. The total investment analysis for a piece of construction equipment is an involved process. Major factors to take into account are the selling price, resale value, financing costs, accelerated cost recovery (depreciation), insurance, and a variety of taxes. These must account for the estimated market value, the finance period, the finance charge or addon interest rate, and the residual book value. To make a satisfactory analysis is more involved than can be shown properly in this book. It can be done with the help of a professional financial person or using a guide like the one produced by Caterpillar, Inc.

The expense of operating a piece of equipment is likely to include the following:

Fuel: both fuel and handling

Lubrication: cost of oil, grease, lube equipment, and labor

Maintenance and repair: parts, supplies, shop equipment, and labor

Labor: operator, oiler, helper, ground men, supervision

Fuel. Fuel cost varies widely with the power, type, and condition of engines; the type and condition of equipment; type of work; and the grade of fuel.

Fuel consumption in relation to horsepower and load is discussed in the next chapter.

Fuel costs vary with the prices of crude oil, distance from the source, quantities delivered, seasonal demand, and taxes imposed.

The delivery quantity may be very important. The contractor with a tank of 275- or 550- gallon (1,040- or 2,080-liter) capacity may have to pay up to 5¢ per gallon more than a big competitor who can take 2,000 or 3,000 gallons (7,570 or 11,400 liters) at a time. However, this difference can be reduced or eliminated if the small order can be filled on the same trip as others in the locality.

There are state taxes of 9¢ to 36¢ per gallon that apply to fuel used in highway vehicles, and the federal gasoline tax in the United States is nearly 20¢ per gallon. Generally, any vehicle that is registered for highway use must be charged with the state tax, even if operation is off the roads.

Taxes may be paid by the distributor at the highest rate and passed on to the contractor, who then must report the amounts used at lower tax rates to obtain a refund. Or the fuel may be delivered tax-free, and the user required to make monthly or quarterly statements of use, with payment of tax due. Payment by the distributor is usually most convenient.

These taxes are substantial enough that it pays the contractor to keep careful account of her or his use of fuel. A tally sheet must be kept at the pump or in the distribution truck, showing quantities, type of equipment, and class of use. The bookkeeper needs the information on these sheets to make up reports, for either tax payment or refunds.

Lubrication. There is considerable variation in lubricant prices and applications, with resulting confusion to the purchaser. In general, the best quality and most suitable lubricant is the most economical regardless of its price per gallon or per pound, as the cost of labor in using it, and the expense of repairing wear and damage resulting from poor lubrication are vastly greater than the price differences.

Oil. Equipment manufacturers recommend that engine oil be changed at regular intervals, that may vary from 75 to 200 hours in different makes or models. The time between changes may be shortened under dusty or extreme temperature conditions, or lengthened where work is light, air is dust-free, and/or a special type of filtering or reclaiming apparatus is used.

Crankcase capacities vary widely with size and design of engines. They may hold a quart of oil for every 3½ horsepower (2.6 kw), or only a quart for 13 horsepower (9.7 kw).

While oil consumption may be negligible in new engines, it may be as high as  of fuel consumption in engines that have badly worn piston rings and/or external leaks. However, no properly run job would tolerate oil loss of more than

of fuel consumption in engines that have badly worn piston rings and/or external leaks. However, no properly run job would tolerate oil loss of more than  of fuel use, as pumping oil into cylinders is accompanied by losses of fuel and power, and leaks are likely to allow dirt to get in.

of fuel use, as pumping oil into cylinders is accompanied by losses of fuel and power, and leaks are likely to allow dirt to get in.

Oil in transmissions, rear ends, and final drives is usually changed twice per year, the most important change being in the fall. Loss between changes is usually negligible, but may become severe because of failure of seals and gaskets, or cracks in housings. Any type of leak may allow dirt to enter, so prompt repair is important.

In general, an allowance of 3 times the reservoir capacity per year will take care of two changes and losses by leakage or accident.

Grease. Equipment varies tremendously in its requirement for grease. For example, a 20-ton (18,200-kg) crawler tractor may use from 1 to 5 pounds (0.5 to 2.3 kg) of grease in old-fashioned track rollers every 8 hours or less. A similar machine having positive seals may need lubricant in the rollers only at 1,000-hour intervals or when the rollers are rebuilt.

Here records are the only indication of what to expect. Even if they only indicate the pounds of grease bought and the total equipment work hours in a year, they will at least provide an average requirement for the fleet.

Small equipment is carried in the tools account and is difficult to separate, while big units are depreciated in the same manner as other equipment. Lacking information to the contrary, a 6,000-hour life may be assumed for them.

Lube Labor. The pay of the people who operate a grease truck or a stationary rack is definitely charged to lubrication. But an oiler on a shovel, in addition to taking care of oiling and greasing, is likely to assist the operator with other maintenance, repair, moves, and in many other ways. It is usual to carry their pay in the same account as that of the operators.

A great deal of lubrication is done by the operators themselves. They may be paid for ½ hour overtime a day to take care of this and fueling, or may do it during the shift in pauses in the work.

A grease truck crew can take care of about three machines per worker hour. This figure is an average of daily lubrications that may take 5 minutes or less, periodic thorough jobs where all points are reached and all reservoirs checked, and complete lubes including oil change.

Rule of Thumb. In view of all the variables and borderline costs, the estimator is justified in accepting and using the rule of thumb that costs of lubrication equal one-third of the cost of diesel fuel or one-quarter of the cost of gasoline. There will usually be some error as a result, but it is likely to be less than that resulting from a superficial attempt to work out the actual figures.

The important thing about keeping track of these costs is to decide on a system and stick to it. A contractor who uses a different method each time he or she thinks of one will not be able to make comparisons between different jobs and different years.

Always keep in mind that the biggest lube expenses are the failures—the breakdowns that are caused by improper or neglected lubrication.

There is no definite line of division between maintenance and repair. It is usual to say that maintenance includes items such as cleaning, inspection, adjustment, routine replacements, and hard face or other build-up welding, while repair consists of fixing or replacing worn or broken parts.

Lubrication is often treated as a maintenance expense, and it is probably the most basic and important of all the maintenance operations.

Many contractors and most equipment rental firms divide repairs into two classes—major repairs, overhauls, and painting; and small repairs and maintenance. The first class may be called shop work, as it should be done in the repair shop even if it actually has to be done in the field, and the second class is called field repairs and maintenance.

In rental arrangements, the shop repairs are usually done by the owners, the others by the lessee, although the contracts do not say so specifically.

A repair, whether in the shop or the field class, serves simply to fix or replace a defective or broken part, together with any associated parts that have caused the breakdown or have been affected by it. An overhaul involves thorough inspection and all necessary rebuilding of an entire unit.

For example, a transmission with a broken gear may be repaired by simply replacing the gear; but if it were overhauled, it would be completely disassembled, all parts would be cleaned and checked, and any defective ones replaced.

Whatever classification is used, there is nothing that is more important to the contractor’s success than careful maintenance and prompt repair, as it will save equipment and money.

Estimating Repairs. A contractor must have a fairly accurate idea of the future cost of maintaining and repairing a machine, before a price can be put on its use. If good records have been kept, the contractor can check his or her own experience, and use it as a basis on which to allow for future expenses.

If there are no records, or if new equipment and/or new jobs are so different that old records do not apply, estimating must be done on the basis of reports of other people’s records or ideas. These must be modified to suit particular conditions.