CHAPTER 25

THE FIGHT FOR THE FORTUNE

COVER-UP

THE jet carrying Howard Hughes from Mexico on April 5, 1976, touched down at Houston Intercontinental Airport at 1:50 P.M. Orderlies lifted his body out of the cabin and placed it in a green and white ambulance for the drive to Methodist Hospital, twenty-eight miles to the south. That morning an official of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute had telephoned Dr. Henry D. Mclntosh, chairman of the hospital’s department of internal medicine, to say that Hughes was seriously ill in Acapulco and would be flown to Houston that afternoon for hospitalization.* Methodist agreed to set aside a heavily guarded room for him where he was to be admitted under the pseudonym of John T. Conover. A handful of the hospital’s staff was told the identity of the prospective patient; the rest knew only that he was a very important man.

The ambulance came to a stop at a rear dock of Methodist Hospital at 2:50 P.M. and Hughes’s body was carried to the morgue in the basement. Under the supervision of Dr. Jack L. Titus, the hospital’s chief pathologist, a medical team conducted a preliminary examination. Titus noted that the body was “remarkably emaciated and dehydrated.”1 Because there was “no evidence of rigor mortis,” and based on other information he had been given, Titus concluded that Hughes had died less than three hours earlier.2 Pending final arrangements, the body was placed in a cooler and guards stationed outside the laboratory door.

Since Hughes had died in Texas and “no physician licensed in Texas was in attendance prior to death,” Titus telephoned the office of Dr. Joseph A. Jachimczyk, the medical examiner of Harris County, to report the death, and the hospital sought to notify the next of kin.3 Hughes’s closest living relative was Annette Gano Lummis, his eighty-five-year-old Houston aunt and younger sister of his mother.* Although Mrs. Lummis had lived with Hughes and his parents for a time when he was growing up, and later looked after him following his mother’s death, she had not seen her reclusive nephew since his triumphant return to Houston in 1938 following the around-the-world flight. She had corresponded with him briefly afterward until Hughes insisted that she route her personal letters to him through Nadine Henley at Romaine Street, and then she stopped writing. “I just wrote him that wasn’t the way I was corresponding,” she said later.4 Other than a two-page telegram she received in 1970, congratulating her on her eightieth birthday, Mrs. Lummis never heard from her nephew. When the hospital informed her of his death, Mrs. Lummis asked her son, William Rice Lummis, who was, coincidentally, a partner in the law firm of Andrews, Kurth, Campbell & Jones, which had represented Hughes and his father before him for so many years, to make the funeral arrangements.

By late afternoon, rumor had spread through the hospital that Howard Hughes’s body was in the morgue and a band of reporters had gathered outside the pathology laboratory. That night, a Methodist spokesman confirmed that Hughes had died earlier that day aboard a private plane carrying him from Mexico to Houston, but provided no details about his illness or the cause of death. “We were aware it was an emergency,” the spokesman said, “but we did not know the nature of the problem and we still don’t.”5 All questions were referred to a Hughes spokesman in Los Angeles.

While Hughes’s death was being announced in one part of the hospital, Dr. Jachimczyk, the medical examiner, was sequestered with a group of Methodist physicians, veteran Hughes lieutenants, and Will Lummis in another office. Dr. Jachimczyk felt that an autopsy should be performed. With the family’s permission, the autopsy could be done at Methodist by the hospital’s pathologists, instead of transporting Hughes’s body to the county morgue. The Hughes organization had hoped there would be no post mortem examination, and someone had told Lummis after he arrived at the hospital that Hughes had said he wanted to be cremated. When the meeting broke up, Lummis left for the evening to ponder Dr. Jachimczyk’s suggestion and to discuss it with his mother.

The next morning he returned to the hospital and signed the form authorizing the autopsy. It was performed that afternoon by Dr. Titus and his associates while Dr. Jachimczyk, one of his assistants, and Dr. Wilbur S. Thain and Dr. Lawrence Chaffin, the two Hughes doctors who were with him when he died, and Dr. Henry McIntosh looked on. Later that afternoon, Ted Bowen, the hospital’s president, told reporters who were crowded into a hospital briefing room: “The preliminary autopsy findings demonstrated that Mr. Hughes died of chronic renal disease.”6 Dr. McIntosh elaborated:

Renal means kidney, two of them. Chronic means a long time. And failure means that they don’t work so well. The kidneys have the responsibility of getting rid of waste products the body makes, and they come out in the urine. The kidneys are marvelous organs, and when they don’t function very well, the waste products accumulate. And unless something is done about it, the patient will die. And this is what I think has happened.7

At the press conference or in interviews, those who observed the autopsy or were connected with the Hughes organization sought to convey the impression there was nothing unusual about Hughes’s recent lifestyle or about the circumstances of his death. Dr. McIntosh described Hughes’s body as “that of a man who had lived a full life.”8 Dr. Jachimczyk assured newsmen that Hughes was simply a routine case for his office. “As far as I am concerned, it’s an ordinary death,” he said. “It’s an extraordinary individual involved, perhaps, but the death is like any other death.”9 In answer to speculation about Hughes’s mental competency, Dr. Chaffin told a reporter that Hughes’s brain was not only healthy, but was “the brain of a very smart man.”10 Another member of the autopsy team discounted rumors about Hughes’s long fingernails: “He had lovely, long fingers—the fingers of an artist.”11 Chuck Waldron, one of Hughes’s personal aides, scoffed at suggestions that Hughes might have been mentally ill: “I can assure you he was a normal man. Just like you and me.”12

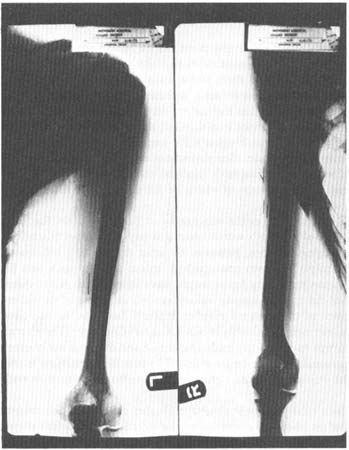

At the press briefing, Methodist officials disclosed that Hughes weighed only ninety-three pounds at death, but other, far more telling details about his physical condition were not made public. Nor were the results of a toxicological study that followed. No mention was made of the bed sores on his back, of his separated left shoulder, or of the open sore on the left side of his head where he had knocked off a tumor a few weeks before. No mention was made that X-rays taken during the autopsy showed fragments of hypodermic needles broken off in both arms. No mention was made of the needle tracks along his arms and thighs or of the extraordinarily high level of codeine in his body. Indeed, the formal autopsy report stated that the body contained only “minimum amounts of codeine.”13 In truth, Hughes had a potentially lethal amount of codeine in him when he died. Not only was this information withheld from the news media, but much of it was withheld from Hughes’s family. Lummis was not shown the X-rays of Hughes’s arms or told of the high amount of codeine. The secrecy which had maintained the Hughes legend when he was alive was at work still, preserving it and safeguarding the empire now that he was gone.

X-ray taken during Hughes’s autopsy showing fragments of hypodermic needles broken off in his arms.

Late on the afternoon of the autopsy, George H. Lewis & Sons Funeral Home picked up Hughes’s body at the hospital and prepared the $8,152 seamless casket that had been selected for his funeral. On Wednesday morning, April 7, 1976—less than forty-eight hours after his death—Hughes was buried as he had lived, privately, in a family plot alongside his father and mother in century-old Glenwood Cemetery, amid the moss-draped oak trees. About twenty persons, mostly distant relatives, attended the simple, eight-minute graveside service and listened to the Very Reverend Robert T. Gibson, dean of Christ Church Cathedral, the Episcopal church that Hughes had attended as a child, read from the church’s Book of Common Prayer. Quoting from Chapter 14 of the Book of John, he said, “We brought nothing into the world and it is certain that we will take nothing out.”14 A few hours after the funeral caravan pulled out of the cemetery, just west of downtown Houston, and into the morning rush-hour traffic, the flowers began to arrive for his grave: red roses sent anonymously; a single red rose from “Karen, California” a five- foot-high yellow and white floral arrangement shaped like an airplane, its nose tipped toward heaven, from an unidentified resident of California.15

Even before Hughes’s burial there was speculation that the industrialist, one of the nation’s two wealthiest citizens, had died without a will.16 If true, the chief beneficiary of the Hughes fortune would be the United States Treasury. The Internal Revenue Service would collect more than 60 percent of the estate, a last, huge irony given Hughes’s life-long obsession with avoiding taxes. The remainder of the estate, after payment of expenses, claims, legal fees, and other costs, would go to Hughes’s relatives, the people he had shunned the last forty years of his life, most of whom he did not know or had not seen since they were children.

The overall value of the estate was murky at best. For years the news media had exaggerated Hughes’s worth, placing it anywhere from $1.5 billion to $2.5 billion. Hughes was not, however, by strict definition, a billionaire. That is, if all his assets had been converted to cash at any one time, and his debts subtracted, the remaining figure would have fallen short of $1 billion. Even so, Hughes did rule an empire valued at well in excess of $1 billion, because, as trustee of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, he exercised control over the enormously valuable Hughes Aircraft Company. The aircraft company’s stock was owned by the medical institute and thus was not counted as part of his personal holdings or his estate. The best strict estimate is that when he died he was worth at least $600 million, perhaps as much as $900 million.

Exactly which relatives would share the Hughes millions in the absence of a will depended on where the estate was administered. If it was administered under the laws of California or Nevada, the states where Hughes had lived from 1925 to 1970, when he left the country, the entire fortune would go to his closest living relative, Annette Gano Lummis. If the estate was administered under the laws of Texas, where Hughes had lived until he was twenty years old, and which he had always listed as a residence on various legal documents, the Hughes millions would be distributed among maternal and paternal relatives, down to the level of first cousins once removed. On Hughes’s mother’s side, there were twelve first cousins, the children or grandchildren of Allene Hughes’s other sister and brother, both dead. On Hughes’s father’s side, there were three first cousins, all the grandchildren of Rupert Hughes, a brother of Howard Hughes Sr. Hughes’s heirs ranged from affluent professionals to blue-collar workers.* Because Hughes had isolated himself from the families of both his mother and father, and over the years had on a number of occasions announced his intention to leave his estate to medical research, none of the relatives had much notion of a Hughes inheritance. But when no will was produced in the days following Hughes’s death, the relatives began to doubt that one existed. Within the empire, the failure to file a will presented a potential management crisis: confusion among the empire’s 12,000 employees, who were unsure exactly who was in charge. With the empire adrift in uncertainty, the ruling triumvirate—Bill Gay, Chester Davis, and Nadine Henley—forged an uneasy alliance with the relatives to assure control of the organization. The maternal relatives themselves had closed ranks behind William Lummis, who would represent them.

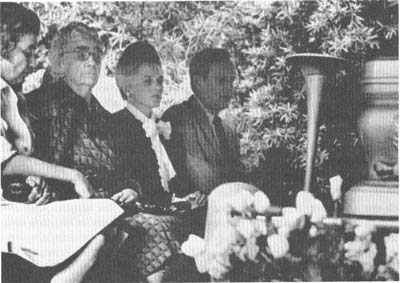

The funeral. Second from left is Annette Gano Lummis, Hughes’s eighty-five-year-old Houston aunt. Wide World Photos

Lummis was described as a “hard-working lawyer who did his job and did not make a lot of noise about it.”17 He had joined Andrews, Kurth after graduating from the University of Texas Law School in 1953 and had married the daughter of Palmer Bradley, a senior partner. In the years that followed, Lummis handled none of Hughes’s personal business, and only “a few workmen’s compensation lawsuits” for the Hughes companies back in the mid-1950s.18 Even Andrews, Kurth’s role in Hughes’s legal affairs had been greatly diminished following Hughes’s feud with Raymond Cook over control of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in 1968 and 1969, and the emergence of Chester Davis as Hughes’s chief lawyer after the industrialist was moved out of the country in 1970.*

With Hughes executives, lawyers, and relatives in seeming harmony, coordinated legal moves were made in Houston, Los Angeles, and Las Vegas on the same day, April 14, to assure tight control of the empire. Andrews, Kurth filed an application in Harris County Probate Court in Houston seeking appointment of Lummis and his mother as temporary co-administrators of the Hughes estate in Texas. Davis & Cox filed a similar petition in Los Angeles County Superior Court requesting the appointment of Richard C. Gano, Jr., as special administrator of the Hughes estate in California, and Andrews, Kurth, and Davis & Cox, and Morse, Foley & Wadsworth filed a petition in the Eighth Judicial District Court in Las Vegas seeking the appointment of the First National Bank of Nevada—as “the nominee of Annette Gano Lummis”—to serve as special administrator of the Hughes estate in Nevada.19†

In legal papers filed in Houston, simlar to those filed in Los Angeles and Las Vegas, Lummis and his mother said they believed that Hughes had “executed an effective last will and testament which, however, has not yet been located,” and that they sought a “temporary administration of the estate for the purpose of facilitating location of said will.”20 In addition, they said their appointment was “essential to avoid any loss or waste to the properties comprising the estate” and to allow for continuity in the operation of Hughes’s various businesses and for “the conservation, preservation and maintenance of the assets.”21 Judges in all three state courts—Kenneth P. (Pat) Gregory in Houston, Neil A. Lake in Los Angeles, and Keith C. Hayes in Las Vegas—routinely issued orders appointing Lummis and his mother administrators in Texas, Gano in California, and the First National Bank of Nevada in Nevada. (Lummis later was named co-administrator in Nevada)

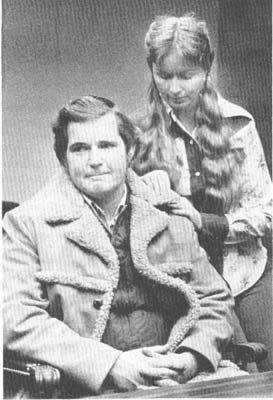

William Rice Lummis, Hughes’s first cousin and son of Annette Lummis, the heir around whom other family members united after Hughes’s death.

Wide World Photos

The old Hughes hands launched a well-publicized search for the will which they privately feared, or knew, did not exist. A safe and the filing cabinets at Romaine Street, locked since Hughes’s visits to the communications center in the 1940s, were broken open. Davis & Cox systematically questioned every lawyer, and the partners of lawyers, who worked for Hughes. Locksmiths were engaged to open a safe, a wine vault, and miscellaneous drawers and files at the home of Neil S. McCarthy, the long-deceased Los Angeles lawyer who had severed his ties with Hughes back in 1944.

Discovery at Romaine Street of “a set of two duplicate keys on a ring,” each imprinted with the number 47 and believed to fit a safe-deposit box, triggered a Cinderella-like search.22 The scores of banks with which Hughes had dealt were contacted about safe-deposit box number 47, about long-forgotten accounts, or other safe-deposit boxes, either in his own name or in the names of nominees. The will hunt reached from the Arizona Trust Company in Tucson to the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York.

Also combed were places where Hughes had spent time in years gone by, or where there might be a Hughes connection—the Columbus Hotel in Miami, the Fairmont in San Francisco, the Goldwyn studios in Hollywood, the Hughes Aircraft Company plants, the Mizpah Hotel in Tonopah, the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, the Racquet Club in Palm Springs, and even, oddly, the Franciscan Monastery in Washington, D.C.23 Dozens who knew or worked for Hughes, and people employed by people employed by Hughes, and their friends and family members, were interviewed, from the secretary of Frank Andrews, the senior partner in Andrews, Kurth who had died in 1936, to the widow of Neil McCarthy. A classified advertisement was placed in about forty newspapers around the country to elicit leads: “Howard Robard Hughes Jr., son of Howard Robard Hughes Sr., and Allene Gano, born Dec. 24, 1905, died April 5, 1976. Anyone having information regarding this death, please phone 213-986-7047.”24

Not surprisingly, such a search for the last will and testament of the nation’s wealthiest eccentric yielded many a bizarre tip. A Santa Monica woman, who predicted earthquakes according to a mathematical formula “based on a very ancient, archaic method of computing,” calculated that the will lay in an airplane then in Acapulco but soon scheduled to fly to Bolivia.25 Her deduction, she said, had been confirmed by a psychic, who, more precisely, had mentally located the will “in the plane’s ceiling, behind a sliding panel almost all the way back in the tail section.”26 A weathered old man in tattered clothes and tennis shoes made periodic visits to the district court clerk’s office in Las Vegas, insisting that he had been Howard Hughes’s secret financial adviser.

The Hughes organization had hired its own psychic—Peter Hurkos. A one time Dutch house painter, Hurkos, or Peter Van der Hurk, as he had been known, billed himself as a psychometrist, “one who divines facts about an object or its owner by touching or being near the object.”27

There are several versions of Hurkos’s role in the great will search, but one part is generally agreed on. Many Hughes lieutenants supposedly still believed that the will rested in a long-forgotten safe-deposit box in a Houston bank. Hurkos advised that he could pinpoint the location of the document if they provided him with photographs of Houston banks and an article of Hughes’s clothing. Andrews, Kurth detailed one of its lawyers and a secretary to photograph all the bank buildings in Houston. At one of them, a suspicious bank official notified the FBI about the amateur photographers. Eventually, the photographs and a pair of Hughes’s shoes were delivered to Hurkos. But, no, the shoes would not do, said Hurkos. They had never been worn; indeed Hughes had worn no clothing in years—the fact that finally led Hurkos to withdraw the application of his psychic powers.*

Efforts to locate a will were not going well. The only evidence of wills related to those that veteran Hughes associates had long known about. The first, of course, was the will Hughes had executed in 1925, just before his marriage to Ella Rice. That will was believed to have been destroyed following the couple’s divorce, and a new draft prepared in 1929. But there is no indication that the second was signed, and, in any event, no copy exists. A third draft will, prepared in 1938, which may or may not have been signed, apparently was placed in safe-deposit box number 3102 in the First National Bank of Houston. But Hughes’s personal files contained a copy of a telegram sent to the bank on May 29, 1944, requesting that the bank “please make forceable entry into my deposit box number 3102 and send contents to me….”28 By 1976, that safe-deposit box had been rented to other bank customers for more than a quarter of a century and no trace remained of the documents put there in 1938. Finally, there was the draft will that Nadine Henley had typed and retyped as Hughes continually revised it from 1944 to 1950. That document, locked away for many years in a safe-deposit box in a Hollywood bank, then transferred to Romaine Street by Nadine Henley, had never been signed. And that was it for the Hughes wills—one signed in 1925 and presumably destroyed; one drafted in 1929, but no evidence it was ever signed, and in any event now lost; one prepared in 1938, but again no evidence it was signed, and which was also lost; and another prepared in the 1940s but never signed.

While the Hughes organization looked for a will that did not exist, in Austin, Texas, John L. Hill, the fifty-two-year-old state attorney-general, a modestly liberal—by Texas standards—populist politician with aspirations for higher office, decided that he would take an interest in the Hughes estate. If Hughes was a legal resident of Texas—and after all, he was born and raised in Texas, the source of all his wealth was a Texas-based company, and he died in Texas—then Texas was entitled to collect tens of millions of dollars in inheritance taxes. A highly regarded lawyer, Hill soon pulled together a team of attorneys led by a tenacious young assistant, Rick Harrison, chief of the taxation division in Hill’s office. Within days lawyers quietly fanned out across the country to collect information on the financial holdings, business interests, and personnel of the Hughes empire. On June 10, 1976, Hill officially staked out Texas’s claim, filing papers in Harris County Probate Court saying that Hughes’s “domicile” throughout his life was Texas and that Texas was entitled to a “sizeable tax.”29

About the same time that John Hill made his decision in Austin, Avis Hughes McIntyre, the stepdaughter of Hughes’s uncle, Rupert Hughes, reached a similar decision at her home in Montgomery, Alabama. A sophisticated and witty woman of seventy-five, accustomed to the gracious and more civilized lifestyle of another era, Mrs. McIntyre had concluded, when it appeared that Hughes had not left a will, that it was time “to enter the rat race” with other Hughes relatives to win a share of the fortune.30 She telephoned her lawyer, a family friend of twenty years, and instructed him to join the growing field of litigants in the Hughes estate on behalf of herself and her brother, Rush Hughes.

The lawyer was George W. Dean, Jr., who had practiced law in his hometown of Montgomery until 1966, when he moved to Destin, Florida, and settled both his family and law practice into a rambling home along the edge of Choctawhatchee Bay, an arm of the Gulf of Mexico about forty-five miles east of Pensacola. Blessed with an incisive mind, and a retentive memory that rivaled Hughes’s, Dean was regarded by colleagues and adversaries alike as a brilliant legal strategist. He had been the architect of a precedent-setting civil rights legal action in the mental health field in which a United States district court ruled for the first time that persons committed involuntarily to state institutions for the mentally ill or the mentally retarded had a “constitutional right” to treatment.31 At age forty-seven, Dean, the epitome of Old World courtliness and southern charm, possessed two characteristics that would quickly set him apart from traditional Hughes attorneys: an unflagging compulsion to seek out the truth, regardless of the consequences, and to lay it out for all to see; and an engaging sense of humor marked by, as one associate put it, a keen appreciation of the general absurdity of life.

It was no small task that Avis Hughes McIntyre had given Dean. Her inheritance rights, and those of her brother, were not clear-cut. Neither had been born into the Hughes family and neither had been adopted.

Rupert Hughes had been married three times. He and his first wife, Agnes Wheeler, had a daughter, Elspeth, born in 1897. The couple was divorced and in 1908 Rupert married Adelaide Manola Bissell, an actress with two young children by a previous marriage that had also ended in divorce. They were Avis, born in 1900, and Rush, born in 1902. Elspeth, Rupert’s daughter, lived with her mother, who also remarried, in Washington, D.C., and later in Cleveland. Avis lived with her mother and Rupert. Rush lived with his father, George Bissell. About three years after Rupert and Adelaide were married, they discovered to their alarm that Rush had been placed in the House of Providence, an orphanage in Syracuse, New York. Quickly securing his release, they brought the boy to the family home, then in Bedford Hills, New York. Although Rupert wanted formally to adopt Avis and Rush, their father refused to permit it, as Mrs. McIntyre recalled.32 Nevertheless, Rupert raised them as his own. They were known as Avis and Rush Hughes, and Rupert sent them to private schools—Avis to the exclusive Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Virginia, and Rush to the Mercersburg (Pennsylvania) Academy. Late in 1923, their mother Adelaide, in ill health and low spirits, set out alone on an around-the-world cruise to “regain her health and courage,” as Rupert said later.33 She found neither and while her ship was anchored in Haiphong harbor, Adelaide hanged herself in her cabin. Less than a year after her suicide, the fifty-two-year-old fiction writer, two years younger than Avis. Avis was upset that Rupert had married for a third time, to Patterson Dial, an aspiring twenty-two-year-old fiction writer, two years younger than Avis. Avis was upset that Rupert had married “such a young woman,” and after meeting Patterson and Rupert in New York one day in 1924, she never again saw or talked to Rupert, although they did occasionally exchange letters.34 Rush Hughes, who became a radio announcer for NBC and played bit parts in the movies, saw Rupert on only a few occasions after Rupert’s marriage to Patterson.

But establishing her right to inherit a share of the Hughes estate was not Mrs. McIntyre’s only interest. For some time she had been intrigued about Hughes’s mysterious last years and why his movements had been cloaked in secrecy. She asked Dean to investigate. That assignment would prove no less challenging.

THE MORMON WILL

Late in the afternoon of April 27, 1976—before Dean and Hill began, independently, to piece together the story of Howard Hughes’s life—a public relations officer of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints returned to his twenty-fifth floor office in the church’s world headquarters building in Salt Lake City and found a Mormon church envelope on top of his desk. The handwritten address on the envelope said: “President Spencer W. Kimball, Church of Jesus Christ, Salt Lake City, Utah.”

Inside the envelope was a slip of notepaper and a second sealed envelope. A handwritten message on the notepaper said: “This was found by Joseph F. Smith’s house in 1972—thought you would be interested.”*

The second, inner envelope bore this handwritten message:

Dear Mr. McKay,*

please see that this Will is delivered after my death to Clark County Court House, Las Vagas [sic], Nevada.

Howard R. Hughes.

And inside the second envelope was a three-page will written on yellow legal paper. It said:

Last Will and Testament.

I, Howard R. Hughes, being of sound and disposing mind and memory, not acting under duress, fraud or the undue influence of any person whomsoever, and being a resident of Las Vegas, Nevada, declare that this is to be my last Will and revolk [sic] all other Wills previously made by me—

After my death my estate is to be devided [sic] as follows—

first: one forth [sic] of all my assets to go to Hughes Medical Institute in Miami—

second: one eight [sic] of assets to be devided [sic] among the University of Texas—Rice Institute of Technology of Houston—the University of Nevada—and the University of Calif.

third: one sixteenth to Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday [sic] Saints—David O. McKay—Pre.

Forth [sic]: one sixteenth to establish a home for Orphan Cildren [sic]—

Fifth: one sixteenth of assets to go to Boy Scouts of America,

sixth: one sixteenth to be devided [sic] among Jean Peters of Los Angeles and Ellas Rice of Houston—

seventh: one sixteenth of assets to William R. Lommis [sic] of Houston, Texas—

eighth: one sixteenth to go to Melvin DuMar of Gabbs, Nevada—

ninth: one sixteenth to be devided [sic] amoung [sic] my personal aids [sic] at the time of my death—

tenth: one sixteenth to be used as school scholarship fund for entire Country—the spruce goose is to be given to the City of Long Beach, Calif.

the remainder of my estate is to be devided [sic] among the key men of the company’s [sic] I own at the time of my death.

I appoint Noah Dietrich as the executer [sic] of this Will—signed the 19 day [sic] of March 1968

Howard R. Hughes.35

Two days after finding the will, Mormon church officials flew to Las Vegas and turned the document over to the district court. “How the envelope containing the papers was delivered to the headquarters of the church and who delivered it, we do not know,” Wendell Ashton, the church’s public-relations director, announced. “Circumstances surrounding delivery of the envelope frankly puzzle us after a day of extensive checking. Whether or not the will is the actual will of Mr. Hughes or is a hoax, we do not know.”36 Another church official explained that “we simply don’t know whether it’s a hoax or not. It came into our possession. We felt we should lay our cards on the table and let the proper authorities determine if it’s authentic or a hoax.”37*

Thereby began an elaborate hoax that would make Clifford Irving’s “autobiography” of Hughes pale into insignificance. Although finally no more successful than Irving’s caper, those who executed it would gain a certain satisfaction. Unlike Irving and his wife, whose misdeeds were swiftly ferreted out and who were convicted and sent to prison, the identity of the perpetrators of the counterfeit will not only would go undetected, but local, state, and federal law enforcement authorities made no serious effort to seek out and prosecute the forgers, a situation that differed markedly from the zealous pursuit of the Irvings by several law enforcement agencies. Moreover, the Mormon will hoax would prove immensely more costly than the Irving flimflam: teams of lawyers, legal secretaries, and private investigators spent millions of dollars contesting the will’s authenticity and establishing it as a forgery.

In the beginning, many wanted to believe in the will, if for no other reason than the fairytale bequest it made to a Utah service station operator, Melvin Earl Dummar. A story headlined “$156 Million Good Deed” in the Los Angeles Times typified articles published by newspapers across the country:

A “good samaritan” deed eight years ago by a 31-year-old Utah service station owner may have earned him more than $156 million when he was named as an unexpected beneficiary in the purported last will and testament of the late billionaire Howard R. Hughes.

Melvin Dummar, owner of a service station in the small community of Willard, Utah, Thursday was named in the document as the beneficiary of a one-sixteenth share of Hughes’s vast estate, estimated to be worth as much as $2.5 billion.

Reached at his home late Thursday by United Press International, Dummar said he had found a man who later said he was Hughes lying beside a road, bleeding from one ear, in January, 1968, and had lent him a quarter after giving him a ride to Las Vegas, where Hughes lived at the time.

Recalling details of the incident, Dummar said he had been driving in the Nevada desert—“in the middle of nowhere between Tonopah and Beatty—and I picked up this guy who I thought was a bum.”

The man, Dummar said, had been bleeding from his ear and had been lying by the side of the road, wearing “some kind of baggy pants and tennis shoes.”

Dummar said he offered to take the man, who he described as tall, skinny with a short, stubby beard and a big scar on the left side of his face, to a hospital, but the traveler refused.

As they drove along, Dummar said, the man told him he wanted to be driven to the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas.

“I dropped him off behind the Sands. He didn’t tell me what happened. He didn’t say nothing and wouldn’t talk until we got to Las Vegas.”

“That’s when he told me he was Hughes.”

Dummar, a Mormon, lived in Gabbs, Nev., in 1968 and worked in a magnesium mine there until moving to Willard about 18 months ago.

Dummar said the man asked “if I could loan him some money and I think I gave him a quarter.”38

Melvin Dummar and his family adapted well to the publicity that gushed forth. Ronald B. Brown, whose mother was married to an uncle of Melvin’s, flew to Willard, Utah, from his Bellflower, California, home to manage the descending hordes of newspaper, radio, and television reporters. A onetime country club greensman and marketer of new inventions, Brown made the arrangements and laid down ground rules for the media.39 As he later described his role in dealing with reporters, “I just told them about—specifically I mentioned to them his [Melvin’s] state, that they shouldn’t be pressing because it would interfere with his emotional state at that point, and that if I noticed that it was pressing that I would completely cut off the interview at that time.”40

Brown got together with Melvin’s father and dashed off a rough manuscript of nearly one hundred typewritten pages recounting the early life of the Hughes heir, conferred with New York publishers, including a top official of one paperback publishing house, who sight unseen, Brown said, “expressed a real desire to have it.”41 Universal studios made arrangements with Melvin to produce a motion picture of his life—with suitable emphasis on the Hughes rescue. The studio flew Melvin and his second wife to Hollywood where they stayed at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel—“the fanciest place I ever saw,” Melvin said—and signed his first wife to a contract giving her 0.25 percent of the film’s profits.42 Brown, Melvin, Melvin’s father, and other family members discussed plans for “setting up a business to sell promotional items” using Melvin’s name.43 And after years of writing songs that no one would buy, Melvin, who looked like an overweight Glen Campbell, was suddenly beseiged by people who wanted to publish his music. His works included “A Dream Can Become a Reality,” “Souped Up Santa’s Sleigh,” and “Rockview Blues,” a song he wrote while driving a milk truck.44

Melvin Dummar and his wife shortly before the trial to determine the validity of the will which named him as one of the beneficiaries of Hughes’s estate.

Wide World Photos

Notwithstanding his fame as a Good Samaritan, Melvin Dummar had a curious background. The fourth of eight children of Arnold and Chloe Dummar, he was born on August 28, 1944, at Cedar City, Utah, and raised in Fallon, Nevada. In addition to his stint as a milk-truck driver, he sold cosmetics door to door and had worked in a magnesium mine in Nevada and in a lath and plaster business operated by his father in California. He had enlisted in the air force for four years in February 1963, but was discharged after only nine months because of his “emotional makeup.”45 In 1968, the same year that Hughes allegedly wrote his Mormon will, Melvin was arrested and charged with forging endorsement of a $251 payroll check issued by his employer, Basic Refractories Inc., in Gabbs, Nevada. When the jury could not reach a verdict, the judge dismissed the charge. A former drama student, Melvin, had a knack for working his way onto television game shows. He appeared on “Let’s Make a Deal” in 1970 “dressed as a hobo,” and again in 1971 when, he said, he wore “orange pants and an orange sweat-shirt with a string of oranges around my neck with an orange hat on it shaped like an orange.”46 Next it was “The New Price Is Right” and “Hollywood Squares” in 1974, and a repeat performance on “Let’s Make a Deal” in 1975. On one occasion, Melvin used an assumed name—that of his wife’s stepfather, Wayne Sisk—to go on “Let’s Make a Deal,” and he signed a statement saying: “I have not appeared as a contestant on any other audience participation program or game quiz show for the past year nor twice within the past five years nor have I participated on Let’s Make A Deal within the past five years.”47* As “Wayne Sisk” on “Let’s Make a Deal,” Melvin won an automobile, a freezer, and a range.48 On “Hollywood Squares,” he won a Pontiac Astre. Dummar’s wife, Bonnie—it was the second marriage for both—was a thirty-year-old blonde, with waist-length hair, who had once served sixty days in the Orange County jail for welfare fraud. And one of Dummar’s aunts had compiled material on Howard Hughes as research for a proposed magazine article.

Melvin Dummar and his family aside, there were many who fervently embraced the Mormon will and declared it authentic. “There’s no question,” announced Noah Dietrich, now eighty-seven, the former Hughes executive who had been fired after a bitter falling out with the industrialist in 1957 and who was named as executor in the Mormon will. “It’s his handwriting and it’s his signature. It’s not just similar, it’s the real thing.”49 A Bountiful, Utah, handwriting analyst who examined the will at the request of the Mormon church before it was turned over to the district court in Las Vegas, issued a preliminary opinion that “the document is genuine.”50 An autograph expert in New York declared that the Hughes signature on the will “is indeed genuine…. The signature looks exactly like Hughes and I think it would be exceedingly difficult to forge all aspects of that signature.”51 And two handwriting analysts retained by ABC News said they were sure that Hughes had written the will.

Even so, evidence mounted quickly that the will was a fraud. After examining the document, one after another of the nation’s leading handwriting experts labeled it a forgery. The New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer printed extensive articles discrediting the document. Anyone who had studied Hughes’s handwriting recognized that while the will’s handwriting resembled Hughes’s, it was at best an earnest imitation. And beyond the graphic similarities, there was no resemblance at all. The Mormon will contained errors in fact, spelling, grammar, and language usage completely at odds with Hughes’s precise nature and the voluminous record of his known writings. The differences were most glaring when the Mormon will was placed alongside memoranda Hughes wrote both in the weeks immediately preceding and following the March 19, 1968, date on the alleged will. Although not a perfect speller, Hughes was as good as many who earn their living by the printed word. He turned out page after page of laboriously handwritten messages running to hundreds of words without making a single mistake in spelling or language usage, a pattern that suited his compulsive behavior. The 261-word Mormon will, on the other hand, was pockmarked by sixteen misspelled words—better than one in every twenty words—and another dozen errors in capitalization and style. There were mistakes that Hughes would never make, indeed, did not make before or after the date of the alleged will. The simplest words were spelled incorrectly: “Cildren” for “children,” “devide” for “divide,” “forth” for the number “fourth,” “revolk” for “revoke,” “amoung” for “among,” “executer” for “executor.” Even the name of his cousin, Lummis, was misspelled as “Lommis.”* By referring to the Hercules as the “spruce goose,” the will writer had used a term that Hughes abhorred. Those who worked for him never used it in his presence. In fact, Hughes did not own the Hercules on the date of the Mormon will. Title to the aircraft was held by the General Services Administration. On the envelope in which the will was delivered, Las Vegas was misspelled “Las Vagas.”

A page of the so-called “Mormon” will with misspelled words circled.

In the face of evidence developed very early that the will was a hoax and that there had been violations of both state and federal criminal statutes, law enforcement authorities at every level either remained amazingly aloof or bungled what little work was done. Judges in state courts where the will was filed—but especially in Nevada, which retained custody of the document—failed to press criminal proceedings after their courts were drawn into the fraud. This indifference was best demonstrated when a full year went by before the Mormon will was submitted to the FBI for fingerprint analysis—a delay that almost certainly foreclosed any possibility of finding and prosecuting the persons who had committed the fraud. In April of 1977, when the Mormon will was belatedly forwarded to the FBI laboratories in Washington by Nevada attorney-general Robert List, FBI technicians found “eight latent fingerprints and two latent palm prints” on the will and the envelope in which it was delivered.52 The FBI promptly reported its findings to List:

Eight latent fingerprints have been identified as finger impressions of Buddy Hardy. One of the latent palm prints has been identified as a palmar impression of Loretta Bowman. The remaining latent palm print was compared, insofar as possible with the submitted palm prints, but no identification was effected. Inasmuch as the submitted palm prints were not fully and clearly recorded, conclusive comparisons could not be made.53

Who was this Buddy Hardy, who left eight fingerprints and a palm print on the forged will and envelope? According to an FBI official, he was “a photolab technician in the police department in Las Vegas that was evidently photographing [the documents].”54 And Loretta Bowman? She was the district court clerk in Las Vegas.

Throughout 1976, while law enforcement authorities displayed no enthusiasm for investigating the forged will, Melvin Dummar doggedly stuck to his twin stories: that he had absolutely nothing to do with writing the Mormon will or its mysterious appearance in the Mormon church headquarters, and that he had picked up a man in the Nevada desert in 1968 who said he was Howard Hughes.

One night in January of 1968, “maybe an hour before the sun went down,” Dummar said, he got into his blue, two-door, 1966 Chevrolet Caprice and left his home in Gabbs, Nevada, planning to drive to Las Vegas—an eight-hour trip—and then on to Cypress, California, to visit his daughter, who was living with his estranged wife.55 When he reached Tonopah, Dummar said, he stopped for perhaps three hours, “got something to eat and gambled a little bit,” and then, near midnight, continued on his way south toward Las Vegas.56 On a lonely desert stretch of Route 95, between Tonopah and Beatty, about five miles south of the Cottontail Ranch—a legal bordello famous for its service to libidinous drivers on the dreary 450-mile trek from Las Vegas to Reno-Dummar pulled off the highway onto a rutted lane to relieve himself and rest for a few hours. He had gone “approximately a hundred yards,” he said, when the headlights of his car picked up a man “lying on his stomach” in the middle of the road.57 “When I got out of the car and started walking toward him,” Dummar said, “he was trying to get up himself and he was on his hands and knees when I got to him and I just put my arm around him and helped him on up.”58 Dummar said the man, more than six feet tall, skinny, and over sixty years old, was wearing a sport shirt, slacks, and a pair of tennis shoes. He said he noticed blood coming out of the man’s left ear—“the blood had dried. It wasn’t fresh blood, but it had been on his collar of his shirt and partially on his neck or his hair.”59 Dummar said he also noticed a scar or “a discoloration of the skin” on the left side of his face, extending “from the temple down into his cheek.”60 His immediate reaction, Dummar said, was that the stranger “had been dumped there, that somebody had beaten him up and dumped him there.”61 During the two-hour drive to Las Vegas, Dummar said, his passenger said little. Dummar said he told the man that he once applied for a job at the Hughes Aircraft Company, and the man said “he was familiar with it because he owned it.”62 He said he was Howard Hughes. When they arrived in Las Vegas, Dummar said, “I asked him if he would like me to take him to a doctor or hospital. I could remember him telling me, no, that he would be all right.”63 Dummar said he let the man out of his car behind the Sands Hotel, handed him some change, and that he replied, “Thank you, Melvin.”64

Although vague on many details of this experience, Dummar did not waver on the essential elements in the months following discovery of the Mormon will. Similarly, as late as December of 1976, he continued to insist that he played no part in writing the will or delivering it to the Mormon church. Questioned under oath during a deposition proceeding in December of 1976, Dummar’s answers were unequivocal:

LAWYER: When was the first time you saw a copy of that purported will?

DUMMER:… It was in April at the end of April and a news reporter from Salt Lake City… brought a copy of it up and gave it to me.

LAWYER: Prior to that time you had never seen a copy of the will?

DUMMER: No, I hadn’t.

LAWYER: Have you ever seen the original of it?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: Let me ask you straightaway, Mr. Dummar, at the outset, did you write that will?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: Did you have anything to do with the writing of it?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: Did you write either of the envelopes and the messages, the message on either of the envelopes or the note which was included in the will…?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: Did you have anything to do with writing those notes or those envelopes?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: Did you ever have any of those documents in your possession at any time?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: Do you as of today, Mr. Dummar, have any idea how this purported will ended up on the desk of one of the Mormon Church employees on the 25th floor of the church office building headquarters?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: You had nothing to do with getting the will there?

DUMMER: No.

LAWYER: You never had your hand on this outside envelope?

DUMMER: No.65

Even when Nevada attorney-general List informed Judge Keith Hayes in Las Vegas that the FBI had found Dummar’s left thumb print on the outer envelope containing the Mormon will, Dummar continued to deny involvement.* “I talked to Melvin last night,” one of Dummar’s lawyers said following the attorney-general’s disclosure. “He was crying and he told me again he didn’t do it. He said if anybody anywhere has any information on how the will got to where it was found, he wishes they would come forward.”66 Harold Rhoden, the shrewd Los Angeles lawyer seeking to have the will validated, tossed out a possible explanation for the discovery of Dummar’s thumb print on the envelope. “Suppose,” Rhoden said, “this is a print not put there by human amino acid but by a Summa Xerox machine?”67

Two weeks later Dummar told Rhoden that he had been “lying” all along and Rhoden arranged for a special hearing before Judge Hayes to allow Dummar to recant his previous testimony in favor of a new story. Before a packed courtroom in the Clark County Court House on January 25, 1977, Dummar offered his revised version.

“About 10 o’clock in the morning” of April 27, 1976, Dummar testified, a stranger “between forty and fifty” years old, driving a blue Mercedes Benz, pulled into his service station in Willard, Utah.68 “He asked me if I was Melvin Dummar. I told him yes,” Dummar said.69 The man said “he had been looking for me for some time.”70 Dummar said he did not ask the man’s name, nor did he ask why he had been looking for him because “I didn’t care,” and besides, “lots of people come in and ask if I was Melvin Dummar.”71 For about half an hour, Dummar testified, the stranger followed him around while he waited on other customers and they chatted and eventually “the conversation led to what did I think of Howard Hughes dying?”72 The stranger, Dummar said, told “me something about a will of Howard Hughes that had been found” in Salt Lake City in 1972.73 “He said it was found somewhere around Joseph Smith’s house, in his house or around it or by it.”74 Dummar said the man asked him, “wouldn’t it be nice if someone like me was in a will of Howard.”75 Dummar said he told him “it would be nice.”76

After the stranger disappeared without saying good-bye or explaining why he had been looking for him, Dummar said, he was “tinkering around” in the service station—“sweeping the floor, washing windows, I don’t know what I was doing”—when he noticed an envelope on a counter top “right where my books and school work was.”77* Dummar said the envelope bore this handwritten note: “Dear Mr. McKay, Please see that this will is delivered after my death to Clark County Court House, Las Vegas, Nevada. Howard R. Hughes.”

Rather than tear the envelope open, “because I was afraid of what was in it and I didn’t want anybody to know I opened it,” Dummar testified, he steamed it open.78 “I had an electric frying pan and I plugged [it] in, put water in it and turned it up as high as it would go.”79 He had opened other mail the same way, Dummar said, when he wanted to look “at letters my ex-wife had written to her boyfriend and what have you, before she could mail them.”80 When he got the envelope open, Dummar said, he found the will, read it, and returned it to the envelope. Then, he said, “I took the will back out of it because I couldn’t believe what I read, and I read it again, and I done that several times.”81 Finally, he said, “I then took some other envelopes and used my finger and got some of the glue off of other envelopes and got them wet and got it transferred, the glue, onto this envelope and sealed it back up, and I put it in a little oven. I thought it would help seal it up.”82

At that point, said Dummar, who was studying for the Mormon priest-hood, he decided to take the will to the president of the Mormon church, although he did not know his name. “I planned to take it and find out who the president of the church was…” he said.83 “I was going to explain to the president of the church and have a word of prayer with him and tell him the story and kind of let him handle it and advise me, because I could trust him.”84

Dummar said he waited for his wife to return with the car. When she came home, he told her he was going to school, but said nothing about the stranger who had left a will in the gas station that named him as a beneficiary of the Howard Hughes fortune. He did not mention the will, Dummar said, because his wife “had been kidding about Howard Hughes” since they were married in 1973.85 On several occasions, he testified, she told him, “one of these days Uncle Howie is going to leave us in his will.”86*

Dummar said he left the gas station about 3 P.M., drove to Salt Lake City, went to the Visitor’s Center on Temple Square, and asked where he could find the president of the church. He was directed to the twenty-fifth floor of the church office building across the street. On the way out of the Center he picked up a Mormon church envelope as a souvenir, he said. When he got off the elevator on the twenty-fifth floor, Dummar said he asked a woman receptionist if he “could see the president of the church.”87 Dummar said the woman told him the president “was in conference or he was busy at that time and I would have to wait.”88 He went down the hallway to a restroom, Dummar said, took the Mormon church envelope he had picked up at the Visitor’s Center, and wrote across the front: “President Spencer Kimball, Church of Jesus Christ, Salt Lake City, Utah.” Next, he took a slip of notepaper and wrote, “This was found by Joseph Smith’s house in 1972—thought you would be interested.” He placed the envelope containing the will and the note he had just written inside the Mormon church envelope addressed to President Kimball, “walked out, walked across the hallway, laid it on a guy’s desk and left.”89

Undaunted by Dummar’s new story and the negative opinions of so many handwriting experts, Harold Rhoden plunged ahead in his attempt to have the will probated as authentic. A resourceful lawyer who had represented Dietrich in other lawsuits with Hughes, Rhoden had acquired a silent partner in the will campaign. In an arrangement most peculiar to a legal action that Judge Hayes had loftily declared “a search for truth,” a Los Angeles stock market speculator was underwriting a substantial portion of Rhoden’s legal expenses.90 He was Seymour Lazar, whose reputation for moving in and out of the market—in one year he traded more than $300 million worth of stocks by his own count—once prompted him to observe that “if I bought stock in the morning and still owned it at noon, it was a long-term investment for me.”91 This time, instead of playing the market, Lazar was gambling in the courtroom, confident that Rhoden would persuade a judge and jury that the Mormon will was genuine. The potential return on his investment was staggering. “It’ll cost me $250,000 minimum,” he told a reporter, “but I’m hoping for a good chunk of the attorney’s fees… maybe in the eight-figure category, for my efforts.”92 Rhoden held out yet another possibility for his backer. “I’m told Lazar is very sophisticated financially,” he said. “He could probably be very helpful in the management area [of Hughes] if we’re successful.”93

In addition to advancing cash, Lazar had spent weeks in Europe lining up handwriting analysts who would support the Mormon will, a global search made necessary when most of the recognized experts in the United States declared the will a fraud. Indeed, even handwriting authorities initially retained by Lazar in the United States had advised him and Rhoden that the Mormon will was a hoax. Such was the opinion—to name but one—of Lon H. Thomas, a former questioned-documents examiner for the United States Secret Service and retired chief of the documents section of the Central Intelligence Agency. In a December 9, 1976, letter to Rhoden, Thomas noted:

In response to request from Mr. Seymour Lazar on December 2, 1976, I have made an exhaustive and thorough examination/comparison of the handwriting on the documents listed below. He requested that an expert opinion be rendered as to whether the will was actually written by Howard R. Hughes or whether it is a forgery…. It is my opinion that the handwriting in the will and on the envelope was not written by Howard R. Hughes. It is my judgment that all of the questioned writing is a forgery.”94

Rhoden’s defense of the Mormon will was also complicated by Dummar’s admission that he had handled the document and his amended story that it had been left at his gas station by an unidentified man driving a Mercedes Benz. But within days of Dummar’s latest revelations, the mysterious stranger surfaced. Or at least a man who claimed to be the man who visited Dummar’s service station and left Howard Hughes’s will there. His name was LeVane Malvison Forsythe. He, too, had a curious background and told a curious story.

A burly, fifty-three-year-old construction worker, Forsythe had managed thrift stores for a mental retardation association in Los Angeles in 1969 and 1970, when he was fired following a stormy controversy with the association’s board. He was accused of misusing the association’s funds and placing phantom workers on the payroll, including an “investigator” who was paid in cash, or whose checks were cashed at taverns and liquor stores, sometimes by Forsythe himself, but whom no one had ever seen and Forsythe himself said he could not find. Parents of retarded children were angered that children were being paid six cents an hour for work they did, while Forsythe was drawing a $20,000-a-year salary.

Forsythe eventually drifted off to Poulsbo, Washington, where, by his own account, “for a year I did nothing but just fish,” and then moved on to Anchorage, Alaska, where he became a part-owner of a construction company that was building a hospital.95 When Rhoden introduced Forsythe as the man who had delivered the Mormon will to Melvin Dummar, Forsythe fashioned an extraordinary account of his life as a secret Hughes agent.

Forsythe said that shortly after meeting Hughes in 1946 or 1947, he began handling confidential assignments for him, delivering letters and packages around the country. Whenever Hughes had a mission for him, Forsythe said, the industrialist sometimes called his mother’s home and left a message using the code name “Ventura.”96 Other times, Forsythe said, he met Hughes at different locations. In executing his missions, Forsythe said, he “generally used a fictitious name,” and that over the years he assumed “more than fifty” aliases.97 “I traveled all over the place,” he said. “And everytime I was out I used different names. I had to look at the name on my suitcase to remember who I was supposed to be.”98

Forsythe said he did not know the contents of the letters and packages he delivered, nor could he recall the names of any of the persons to whom he delivered them. But over a twenty-five-year period, he said, he made “approximately fifty of these secret deliveries.”99 In addition, Forsythe said, his “Uncle Claude” had served as a middleman, transferring packages from Hughes to Forsythe for delivery.100

“It was the latter part of July or August of 1972, or first part of August,” Forsythe said, when he received a telephone call from Hughes asking him to come to the Bayshore Inn in Vancouver.101 A short time later, he said, he flew to Vancouver, went to the hotel room that Hughes had given him, knocked on the door, and “was told to come in…. I opened the door. It was ajar; it wasn’t completely closed.”102 There were no guards, no security system. Inside the room, he said, he found Hughes, wearing a bathrobe, seated in a chair, “a towel on his lap.”103 After exchanging some small talk, Forsythe said,

[Hughes] told me why I was there, why he had requested me to be there…. That he had a brown envelope that was laying on the table and he wanted me to—entrust me with it. And that I was—I would probably be retaining it for some time…. And wanted to know if I would accept that responsibility and that the document, the brown envelope, contained instructions in case of his death. And he asked me if I was willing to accept that responsibility…. I told him I would accept that responsibility.104

Forsythe said Hughes told him that “on no occasion was I to open that envelope until he had passed away…. He said [he] may call for it back. If he calls for it back, he didn’t want it opened.”105 Forsythe said he kept the envelope for nearly four years and that on the day Hughes died, he opened it. Inside, he said, were three envelopes, one addressed to Chester Davis, one addressed to Mr. McKay, which contained the Mormon will, and a third envelope, marked “open this one,” which contained $2,800 in $100 bills.106 Forsythe said he then flew to Salt Lake City under an assumed name—“I didn’t really want anyone to know LeVane Forsythe went to Salt Lake City…. I didn’t want them to put me together.”107

When he arrived at the airport, Forsythe said, he hired a driver and a car, which “was maybe two or three years old” and “could have been a Ford or Chevrolet.”108 When he got into the car, Forsythe said, he handed the man a slip of paper with Dummar’s gas station written on it and asked the man if he knew where it was. He said “no, but he would find it.”109 They finally pulled into a gas station—Forsythe could not describe it, “to me it was not very impressive, you know what I mean? I mean it was not a new operation”—and someone pointed out Melvin Dummar to him.110 Forsythe said he talked briefly with Dummar. “The exact conversation I don’t recall,” he said, “but I wanted to satisfy myself that he was Melvin Dummar…. I threw a couple of questions out at him…. ‘What do you think of Howard Hughes’ death,’ or something of that nature.”111 Forsythe said he followed Dummar around for a while, then placed the envelope addressed to Mr. McKay on a counter top inside the service station, and left without mentioning the envelope to Dummar.

Forsythe’s timely appearance on Dummar’s behalf came six years after his provident appearance in another Hughes legal proceeding. Several days after Hughes had vanished from the Desert Inn in November of 1970, Hank Greenspun’s Las Vegas Sun carried a front-page article indicating that the industrialist had been spirited away against his will and that there had been an eyewitness to the incident. At the time, of course, there was much confusion surrounding Hughes’s disappearance, and the story of the eyewitness, at least in the beginning, seemed to lend credence to Bob Maheu’s charge that Gay and Davis had seized control of the empire and fired him without Hughes’s approval or knowledge. The eyewitness was none other than LeVane Forsythe.

In the stormy legal proceedings that followed, during which the Maheu and Gay-Davis factions battled for control of Hughes’s Nevada properties, Forsythe volunteered his testimony to the district court in Las Vegas.* When District Court Judge Howard W. Babcock eventually ruled that Maheu had been lawfully fired and that the proxy giving control of Hughes’s Nevada properties to Gay, Davis, and Holliday was valid, he took special note of Forsythe’s testimony:

Mr. Maheu… produced a witness, Mr. LeVane M. Forsythe, who testified concerning events which represent to his mind the departure from the Desert Inn Hotel of a person in the company of two others under circumstances which suggest mystery and intrigue. The Court observed the appearance, manner and demeanor of this witness. His testimony is not credible, it is not worthy of belief. The Court can only conclude that his testimony is fantasy, not fact.112

After Harold Rhoden, who was championing the Mormon will, discovered Forsythe, he counseled his prospective star witness that attorneys for the Hughes estate would attempt to discredit his story and assured Forsythe that he would produce evidence to back up his story on delivering the Mormon will to Dummar’s gas station, according to a transcript of tape-recorded telephone conversations between the two men subsequently entered into the court record.

In one telephone conversation with Forsythe, Rhoden went to great lengths to assure Forsythe that Keith Hayes, the district court judge who was handling the Hughes estate in Nevada, and who would preside over the Mormon will trial, would welcome his testimony.

RHODEN:… We can use a judge in Las Vegas who will protect you. Who will see to it nothing bad happens. He’s a judge extremely friendly towards us and wants that will to be admitted, and he’d welcome you with open arms—

FORSYTHE: Uh-huh.

RHODEN: Like a savior, because the guy’s a Mormon.

FORSYTHE: Yeah.

RHODEN: To save this for his church—

FORSYTHE: Yeah.

RHODEN: So, he’d—he’d welcome you—

FORSYTHE: Yeah.

RHODEN:… He’s very—the judge knows. He very much wants to hear your story—

FORSYTHE: Yeah.113

FALLOUT

By the spring of 1977, as pretrial maneuvering over the Mormon will raged, Will Lummis moved to bring some order to the chaos that was the Hughes empire. He had the power to do so. In May of 1976, after Lummis had assumed responsibility for administering the Hughes estate, Summa Corporation, with the approval of its general counsel Chester Davis, petitioned the New Castle County Chancery Court in Wilmington to give Lummis control of the company’s stock pending the outcome of the will search and the multiple estate proceedings. Chancellor William Marvel agreed and issued an order on May 11, 1976, authorizing Summa to recognize Lummis “as its sole stockholder.”114

Shortly thereafter, Lummis gave up his law practice of twenty-three years as a partner in Andrews, Kurth, Campbell & Jones, and moved his family from Houston’s quiet and exclusive River Oaks section to Las Vegas, there to become chairman of the board of Summa Corporation.* Although he received a salary of $180,000 a year as chairman, Lummis arranged with the probate courts to have that money deducted from his substantially larger fees as administrator of the estate. In keeping with his low profile, Lummis moved slowly among the ranks of veteran Hughes executives. He went far not to antagonize or challenge those who had run the empire for so many years. As a result, longtime Hughes lieutenants seriously underestimated the new man at the top. As one Summa executive put it later, “Lummis is a well-organized businessman who studies things thoroughly and then acts. I think they mistook his patience and good manners for weakness.”115

Despite assurances to the contrary, Lummis soon realized that his famous cousin had been neither a financial genius nor in control of his business affairs when he died. Indeed, Summa was revealed as a business and financial nightmare. Nearly every operation was losing money, and corporate waste and profligate executive spending abounded. The company was spending upward of $2 million a year to lease and maintain more than a dozen aircraft around the world. Some of the planes had not been flown in years. Others were used to ferry Hughes executives and their families around the United States and Europe. Suites were maintained at the Essex House in New York and the Barclay in London for favored Hughes lieutenants. Summa built tennis courts, rented Mercedes Benzs, and handed out low-interest loans running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars to certain executives. For one fortunate executive, Summa bought his house, paid for a full-time maid, and even his food bills.

By the spring of 1977, Lummis had a firm fix on the extent of the corporate disaster over which he presided. The reports were devastating:

From 1971 through the first nine months of 1976, Summa annually sustained net operating losses which totaled in excess of $131 million. The operations which sustained those losses were directed by Davis, Gay, and Henley. During the same period, none of the major gaming competitors of Summa in Nevada suffered any operating loss for even one of the years involved…. Primarily through the sale of TWA and the oil tool division, Summa had, or had received from January 1, 1966 to September 30, 1976, cash of approximately $715 million. But on September 30, 1976, its total liquid assets were only $142 million and by March 31 [1977], they had declined to $94 million. This lack of liquid assets threatened the very viability of Summa because it was only through interest earned on its cash that Summa had been able to continue to survive in the face of its regular operating losses.116

In December of 1976, after a series of disputes with Chester Davis, most notably over the role Summa should play in the administration of the estate, Lummis asked Davis to resign from the board. Davis refused. Now, in addition to the legal war over the legitimacy of the Mormon will, there would be a war for control of the empire, pitting the old Hughes hands against Lummis and the other Hughes relatives.

The showdown came in May of 1977. At a Summa board meeting on May 18, the Gay-Davis faction pushed through a resolution authorizing the “expenditure of up to $49,978,000” for a massive renovation program at the Desert Inn Hotel and Casino—a property that Summa did not own, but leased.117 The resolution was approved 5 to 2—Gay, Davis, Holmes, Myler, and Henley voted in favor. Lummis and West cast the dissenting votes. Rankin abstained. At the same meeting, the Hughes veterans also rejected proposals by Lummis and his associates to retain Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith—which had just completed an appraisal of Hughes’s holdings for probate court—to act as financial advisers to Summa, and to declare a $32-million dividend to the estate in order to meet its mounting financial obligations. In addition, the old Hughes hierarchy also opposed setting aside funds for damages in the TWA lawsuit in Delaware and the Air West lawsuits in San Francisco. Judgments had already been entered against Hughes in both these cases. While the amount of the damages remained to be fixed, the total could reach $100 million.118

A week later, on May 26, Lummis removed Davis, Holmes, and Myler from the Summa board, reduced the size of the board from eight to seven directors, and elected as their successors Vernon C. Olson, Summa controller for a number of years, and E. R. Vacchina, a senior vice-president of the First National Bank of Nevada—special co-administrator of the Hughes estate in Nevada. Lummis also took over as chief executive officer of Summa, but allowed Bill Gay—who had been president since Hughes’s death—to continue in that post. This was merely a reprieve for Gay, whose compensation in 1976 had been $360,523—including a bonus of $108,583 for a year in which Summa’s losses exceeded $20 million. He, too, would soon be gone.

While Lummis was struggling in Las Vegas to reverse years of mismanagement in the empire, fend off challenges from veteran Hughes executives, and oversee the ongoing administration of the estate—including preparations for the upcoming Mormon will trial—George Dean and Texas attorney-general John Hill were preparing, independently, for a series of critically important pretrial proceedings that would disclose the results of intensive, year-long investigations.

Immediately after entering the Hughes estate litigation in 1976, Dean had recruited a team of lawyers to help him, first, to establish that his clients, Avis and Rush Hughes, were lawful heirs to the Hughes fortune, and second, to determine exactly what had occurred in the Hughes empire, especially during Hughes’s last years. Dean’s legal team included T. Norton Bond, a thirty-year-old Pensacola, Florida, lawyer with a disarmingly engaging manner and a bear-trap mind, and Robert H. Roch, who had graduated at the top of his Baylor University Law School class and was a founding partner in a young and aggressive Houston law firm, Fisher, Roch & Gallagher, which in the few years since it was formed had elevated personal injury law to an art form, its work distinguished by an unusual thoroughness in trial preparation. Dean and his associates had come up with an obscure legal concept known as “equitable adoption,” which held that in certain circumstances children not formally adopted were entitled to the same inheritance rights as adopted or biological children. They contended that after Rupert Hughes had married his second wife, Avis and Rush, her two children by her first marriage, were known throughout their childhood as Avis and Rush Hughes. Because Rupert had treated them as his own—sending them to private schools, introducing them as his son and daughter, giving away Avis in marriage, and helping Rush obtain work—they were “equitably adopted children,” Dean and his colleagues argued.119 Although Rupert Hughes’s three grandchildren from his first marriage at first challenged the concept, by the spring of 1977 Dean was near an understanding that Avis and Rush would share in the Hughes estate in the absence of a will.* Later that summer a new settlement agreement was drawn up providing for distribution of the Hughes fortune to the industrialist’s only living aunt, Annette Gano Lummis, sixteen cousins on his mother’s side of the family, and five cousins on his father’s side of the family, including Avis and Rush.†

John Hill’s staff had meanwhile accumulated a massive collection of Hughes’s private papers and records, including 10,000 documents that had been seized by Mexican authorities at the Acapulco Princess Hotel shortly after Hughes died. To establish that Texas was Hughes’s legal residence at the time of his death, and thus entitled to collect the state’s 16-percent inheritance tax, Assistant Attorney-General Rick Harrison and his staff had been sifting through and cataloging the papers, which included memoranda to and from Hughes on many sensitive subjects, and the daily logs kept by the aides, with their enigmatic, coded entries such as “8 c,” or “6 BB’s,” or “8 c’s (23 left),” or “he took 6 of the 25 # 4’s,” or “E Day.”

In May and June of 1977, a small army of lawyers representing various and often conflicting interests in the Hughes estate gathered in Los Angeles to take sworn testimony of the aides who had lived with Howard Hughes for nearly the last twenty years of his life. Using information gleaned from the empire’s internal documents, Harrison, Dean, Roch, and other lawyers drew from the reluctant witnesses a picture of Hughes that had never before been documented: a Hughes who had been taking drugs for thirty years, who had consumed enormous quantities of narcotics without any medical reason, who had spent most of the last two decades of his life in bed or on his reclining chair, naked. The aides interpreted the cryptic references on the daily logs: “BB” stood for Blue Bombers, the name the aides gave to the blue-colored ten-milligram Valium tablets that Hughes took; “c” stood for codeine tablets he dissolved in water and injected; “# 4’s stood for Empirin Compound No. 4 tablets, which also contained codeine; and “E Day” meant enema day. The aides acknowledged that the entries on the logs did not begin to tell the full story of Hughes’s massive drug habit. As Waldron confided under questioning by Harrison:

HARRISON: And did you enter [in the logs] medication he received?

WALDRON: If he should ask if he took something and I said, “I don’t know,” he said, “Well, I just took two; go put it down.” Then I would. Other than that, I wouldn’t know whether he took any.

HARRISON: Did you only put down on the log medication when Mr. Hughes said to put it down?

WALDRON: That’s correct. Or if I happened to be in the room and I saw him taking something. I would put it down so that the next person on would know that he had.120

In other words, if Hughes neglected to mention that he had administered himself narcotics or tranquilizers, or the aides did not happen to see him take the drugs, no record was made.

On June 26, 1977, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article disclosing that over the years Hughes “was illegally given massive quantities of narcotics, tranquilizers and other pain killing drugs” and that “the drugs were obtained with prescriptions issued in the name of persons other than Hughes.”121 Four days later, the United States Drug Enforcement Administration launched an investigation of the Hughes drug-supply operation.

For the next few months the Texas attorney-general’s office and the Dean team compiled evidence not only of Hughes’s bizarre behavior, but of questionable financial, business, and legal transactions carried out in his name. Meanwhile, District Court Judge Keith Hayes in Las Vegas and Probate Court Judge Pat Gregory in Houston each set November 1977 trial dates in their respective courts to determine the authenticity of the Mormon will.

Jury selection began on Monday, November 7, in Las Vegas, and the following week in Houston. The Houston trial lasted until February 15, 1978, when the jury of three men and three women, after deliberating some ninety minutes, voted unanimously on the first ballot that the Mormon will was not written by Hughes and that Hughes was a legal resident of Texas at the time of his death, thereby requiring the estate to pay inheritance taxes. In Las Vegas, the trial progressed at a more leisurely pace, continuing through March, into May, and on to June 8, 1978, when the jury of five men and three women, after deliberating eleven hours, voted unanimously that Hughes did not write the Mormon will.

Only one serious challenge to the estate remained. The more than three dozen other “wills” submitted to various probate courts had been accepted for what they obviously were—hoaxes. But when Will Lummis began exerting a growing influence late in 1976 over the Hughes empire business operations—setting the stage for the break with Bill Gay and Chester Davis that would follow—the two veteran Hughes lieutenants responded by initiating their own will contest. In January of 1977, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which was controlled by Gay and Davis as members of a two-man executive committee, filed a petition in Las Vegas district court seeking to have the Hughes fortune awarded to the medical institute even in the absence of a will.

In the petition, prepared by the medical institute’s longtime Washington counsel Hogan & Hartson, the medical institute contended that Hughes “executed a Last Will and Testament which was unrevoked and validly existing at the time of [Hughes’s] death, the substance of which provided that the [Hughes] estate… be… bequeathed” to the medical institute.122 The medical institute claimed that the will “has not yet been produced by the person or persons in possession thereof and the identity of such person or persons is presently unknown.”123 If the will cannot be found, the medical institute argued, “then it has been lost or destroyed without the knowledge or consent of [Hughes].”124 The institute asked the court for an opportunity to prove its theory and have the missing will “admitted to probate.”125 In effect, Gay and Davis boldly hoped to convince the court that somewhere there was a Hughes will, that the will was lost or destroyed, and that the “lost will” named the medical institute as the lone beneficiary of the Hughes estate.