3

3

An Ancient-Style Rhapsody (Gufu)

“Shanglin fu” (Fu on the Imperial Park) is an example of the most important poetic form of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), the fu. The fu has no exact counterpart in Western literature. The term has been variously translated as “rhapsody,” “rhyme-prose,” “exposition,” and “poetic description.” One of the important formative influences on the Han fu is the literary tradition of Chu, especially the poems attributed to Qu Yuan, which in Han times were actually classified as fu. The Han fu inherited from the Chu poems the sao-style prosody (chap. 2), ornate diction, and the themes of the imaginary journey as an escape from the troubles of the world and the complaint of the scholar-official who feels unappreciated by his contemporaries.

Although the fu has its origins in pre-Han literature, the mature form of the fu did not emerge until the Former Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–8 C.E.), when poets, especially at the Han imperial court, began to compose long, difficult poems that became the standard against which most fu ultimately are measured. This type of fu, which later anthologists classified as the gufu (ancient-style fu), has the following features: an ornate style, lines of unequal length, a mixture of rhymed and unrhymed passages, parallelism and antithesis, elaborate description, hyperbole, repetition of synonyms, extensive cataloging, difficult language, a tendency toward a complete portrayal of a subject, and often a moral conclusion.

Other types of fu developed during the Han. For example, some writers began to use the fu as a means of personal expression. This type of fu, in which the poet vents his anger against a “hostile” ruler and court, is called the frustration fu. One common theme is the topos of time’s fate, in which the poet complains that he has been born in the wrong time for the acceptance of his ideas. Another type of fu that became increasingly common by the Later Han period (25–220) is the yongwu (poem on things). Yongwu poems are relatively short compositions on birds, other animals, plants, stones, household articles, buildings, musical instruments—even insects.

By the end of the Later Han, writers began to write shorter, more “lyrical” pieces, many of which are nearly indistinguishable from lyric shi compositions. A good example is “Deng lou fu” (Fu on Climbing the Tower), by Wang Can (177–217). Wang Can wrote this poem after climbing a wall tower at the southeastern corner of the city of Maicheng, which was located at the confluence of the Zhang and Ju rivers, about thirty miles northwest of modern Jiangling. He begins the fu by describing what he sees from the tower. He sees the Zhang River, with its small tributary that connects with the twisting Ju River and its long sandbars. In back of him he sees hills and a long plain, and in front he gazes on wet marshlands. The area also is the site of grave mounds, and the land is rich with flowers, fruit, and millets. However, as beautiful as the scene is, the poet is not happy in this place, and he expresses the regret that he is unable to return to his home in the north.

During the Southern and Northern Dynasties period, the fu continued to be a favored form of poetic writing. In this period, the form was strongly influenced by the aesthetic of the parallel couplet, and many of the fu compositions consist almost entirely of lines that are perfectly matched grammatically and semantically. This form, known as the pianfu (parallel-style fu), flourished in the late Southern Dynasties. In the Tang, an even more intricately crafted form was the lüfu (regulated fu), which was the required form for the civil service examinations.

The most distinguished fu writer of the Han was Sima Xiangru (179–117 B.C.E.). He was a native of Chengdu in the Shu commandery (modern Chengdu, Sichuan). During the 140S B.C.E., he served for several years at the imperial court and for a somewhat longer period at the court of Liu Wu (d. 144 B.C.E.), prince of Liang. In 144 B.C.E., Sima Xiangru returned to Shu, where he married Zhuo Wenjun, the daughter of a wealthy iron manufacturer. In 137 B.C.E., he took up a post at the court of Emperor Wu (Han Wudi [r. 140–87 B.C.E.]), where he served in various capacities until 119 B.C.E., when he retired to the imperial mausoleum town of Maoling. While in imperial service, one of Sima Xiangru’s main duties was to compose fu for the entertainment of the members of the court. His most famous piece is “Fu on the Imperial Park.” Although the most common title for this fu is “Fu on the Imperial Park,” the original title may have been “Tianzi you lie fu” (Fu on the Excursions and Hunts of the Son of Heaven). The work actually consists of two parts. The first part, which is eliminated from the translation given here, consists of most of “Zixu fu” (Fu of Sir Vacuous). The second section, “Fu on the Imperial Park,” is the sequel that Sima Xiangru composed for Emperor Wu.

Sima Xiangru frames the fu in a form that is a common feature of the fu genre, a debate between three men, each with an imaginary name. First there is Sir Vacuous, who represents Chu as an emissary to Qi. He has attended a hunt hosted by the king of Qi. Representing Qi is a man named Master Improbable. In the “Fu of Sir Vacuous,” each of them presents a lavish description of the hunting parks in their home states. The third protagonist is Lord No-such, who in “Fu on the Imperial Park” describes the wonders of Shanglin Park. This debate feature has its roots in the rhetorical tradition of the Warring States period, much of which consists of debates between men with opposing points of view. Each of the three imaginary gentlemen is the equivalent of a traveling persuader who applies his rhetorical skill on behalf of his ruler.

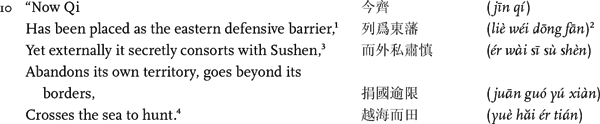

Lord No-such grinned and laughed, saying, “Chu has lost its case, but neither has Qi gained anything to its credit. Having the vassal lords present tribute is not for the articles and presents themselves, but is a means for them to report on the administration of their offices. Setting up boundaries and drawing borders are not for protection or defense, but are a means of curbing excess.

亡是公听然而笑曰:楚則失矣,而齊亦未爲得也。夫使諸侯納貢者,非爲財幣,所以述職也;封疆畫 界者,非爲守禦,所以禁淫也。

“In terms of its vassal duty, such things certainly should not be allowed. Moreover, in your speeches both of you gentlemen do not strive to elucidate the duties of ruler and subject or to correct the ritual behavior of the vassal lords. You merely devote yourselves to competing over the pleasures of excursions and games, the size of parks and preserves, wishing to overwhelm each other with wasteful ostentation and surpass one another in wild excesses. These things cannot serve to spread fame or enhance a reputation, but are enough to defame your rulers and do injury to yourselves. Furthermore, how are the affairs of Qi and Chu worth mentioning? Have you not seen the beauty of the large? Have you not heard of the Imperial Park of the Son of Heaven?

其於義固未可也。且二君之論,不務明君臣之義,正諸侯之禮,徒事爭於遊戲之樂,苑囿之大,欲以 奢侈相勝,荒淫相越,此不可以揚名發譽,而適足以貶君自損也。且夫齊楚之事又烏足道乎?君未睹夫 巨麗也,獨不聞天子之上林乎?

“And then, gazing round, broadly viewing, one sees such plenteous profusion, such a vast vista, he becomes dizzy and dazed, confounded and confused.

於是乎周覽氾觀,縝紛軋芴,芒芒怳忽。

“Places of this sort number in the hundreds and thousands. The emperor sports and plays hither and thither, and in whatever palace he spends the night or lodge where he rests, his kitchen need not be transported, his harem need not be moved, and his official staff is ready and waiting.

若此者數百千處。娛游往來,宮宿館舍,庖廚不徙,後宮不移,百官備具。

V

“And then, as the year turns its back on autumn and edges into winter, the Son of Heaven stages the barricade hunt.

於是乎背秋涉冬,天子校獵。

“At journey’s end, road’s limit, he wheels round his carriage and turns back.

道盡塗殫,迴車而還。

“The airs of Jing, Wu, Zheng and Wei, the music of the ‘Succession,’ ‘Salvation,’ ‘Martial Dance,’ and ‘Mimes,’ melodies of dissolute dissipation, the mixed medleys of Yan and Ying, the finale of ‘Stirring Chu,’ jesters and dwarfs, entertainers from Didi, everything to delight the ears and eyes, gladden the heart and spirit, all in sumptuous splendor and garish glitter pass before him.

荊、吳、鄭、衛之聲,韶、濩、武、象之樂 ,陰淫案衍之音,鄢、郢繽紛,激楚結風,俳優侏儒,狄鞮 之倡,所以娛耳目樂心意者,麗靡爛漫於前。

VII

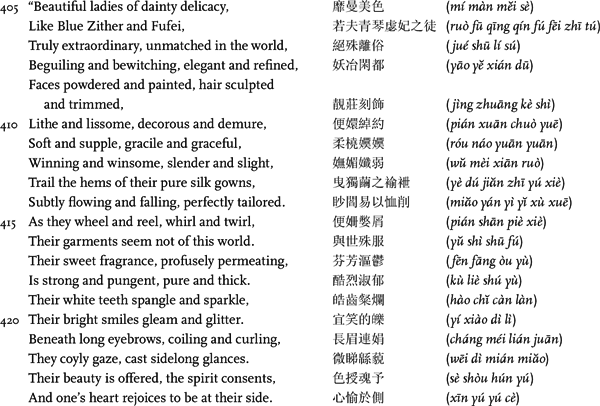

“And then in the midst of drinking, during the rapture of music, the Son of Heaven becomes disconsolate, as if He had lost something. He says, ‘Alas! This is too extravagant! During Our leisure moments from attending to state affairs, with nothing to do We cast away the days; following the celestial cycle, We kill and slaughter, and from time to time rest and repose here in this park. But We fear the dissolute dissipation of later generations, that once they have embarked on this course they will be unable to turn back. This is not the way to create achievements and pass down a tradition for one’s heirs.’

於是酒中樂酣,天子芒然而思,似若有亡,曰: 嗟乎,此大奢侈!朕以覽聽餘 閒,無事棄日,順天道以 殺伐,時休息於此,恐後世靡麗,遂往而不返,非所以為繼嗣創業垂統也。

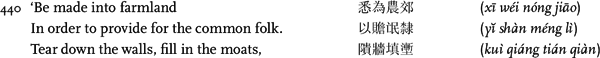

“Thereupon, He ends the feast, halts the hunt, and commands His officials, saying, ‘Let all land that can be reclaimed and opened up:

於是乎乃解酒罷獵,而命有司曰:地可墾辟:

“At this time, all in the empire greatly rejoice, face his virtuous wind and heed its sound, follow his current and are reformed, spontaneously promote the Way and revert to morality. Punishments are discarded and no longer are used. His virtue is loftier than that of the Three Kings, and his achievements are more abundant than those of the Five Emperors. Only under these conditions can hunting be enjoyed.

於斯之時,天下大說, 鄉風而聽,隨流而化,芔然興道而遷義,刑錯而不用,德隆於三皇,功羡於 五帝。若此,故獵乃可喜也。

“Looking at it from this perspective, are not the actions of Qi and Chu lamentable? Their territory does not exceed a thousand leagues square, yet their parks occupy nine hundred of them. This means the vegetation cannot be cleared, and the people have nothing to eat. If someone of the insignificance of a vassal lord enjoys the extravagances fit only for an emperor, I fear the common people will suffer the ill effects.”

從此觀之,齊楚之事,豈不哀哉!地方不過千里,而囿居九百,是草木不得墾辟, 而民無所食也。夫以 諸侯之細,而樂萬乘之所侈,僕恐百姓被其尤也。

Thereupon, the two gentlemen paled, changed expressions, and seemed dispirited and lost in thought. As they retreated and backed away from the mat, they said, “Your humble servants have been stubborn and uncouth, and ignorant of the prohibitions. Now this day we have received your instruction. We respectfully accept your command.”

於是二子愀然改容,超若自失,逡巡避席,曰:鄙人固陋,不知忌諱,乃今日見教,謹受命矣。

[SJ 117.3016–3043; HS 57.2547–2575; WX 8.361–378]

Sima Xiangru’s masterwork is his “Fu on the Imperial Park.” The traditional account of how Sima Xiangru happened to compose this piece is somewhat amusing. Sima Xiangru was living in Chengdu when he received a summons, perhaps in the year 137 B.C.E., to have an audience with Emperor Wu in the capital. It seems that one day Emperor Wu chanced upon a copy of a piece that Sima Xiangru had written at the court of Liang, “Fu of Sir Vacuous.” This poem, which is a lavish description of the hunting preserve of the ancient state of Chu, so impressed the young emperor that he exclaimed to his attendant, Yang Deyi, “Shall We alone not have the privilege of being this man’s contemporary?” Yang Deyi, who was a native of Shu, informed the emperor that his fellow townsman Sima Xiangru was the author of this piece. Emperor Wu immediately issued a summons for Sima Xiangru to appear at court.

This story is not very credible for several reasons. First, one wonders how a text of the “Fu of Sir Vacuous,” which was written in Liang, reached the imperial court. Even accepting the dubious proposition that someone in Liang sent a copy of this piece to the imperial archives, one is endlessly fascinated at the prospect of the nineteen-year-old Emperor Wu sitting in his palace study with a bundle of bamboo strips trying to decipher the text of a fu written in a difficult script and replete with rare words. This is a wonderful story, but it strains credibility.

According to the traditional account, in his audience with Emperor Wu, Sima Xiangru belittled the quality of his earlier composition, which after all concerns only the “affairs of the vassal lords.” He then offered to compose for the emperor a “fu on the excursions and hunts of the Son of Heaven.” With brushes and bamboo slips given to him by the master of writing, Sima Xiangru composed a long fu on the imperial hunting park, Shanglin Park. Emperor Wu was so pleased with the poem that he appointed Sima Xiangru to a position at the imperial court. Although there is nothing implausible about this part of the account, one wonders how much the historian has embellished it to fit the conventional story of the scholar-poet from the hinterland who rises from obscurity to prominence at the imperial court.

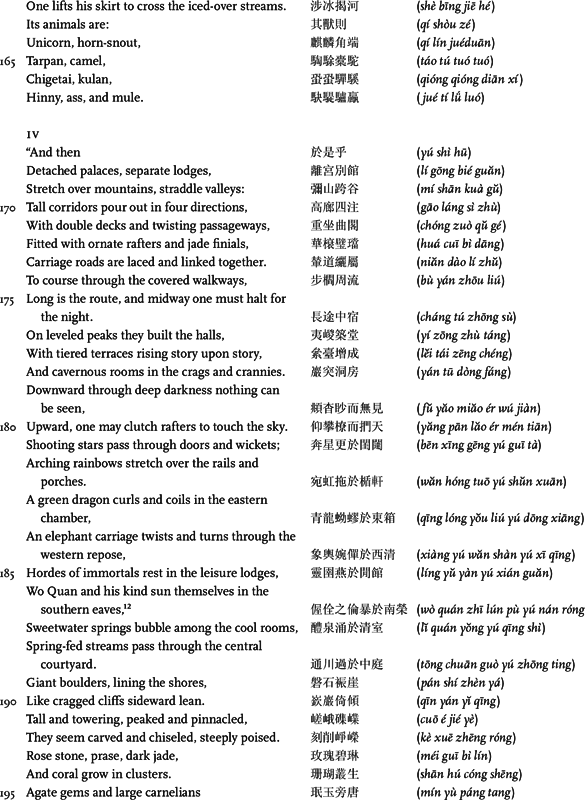

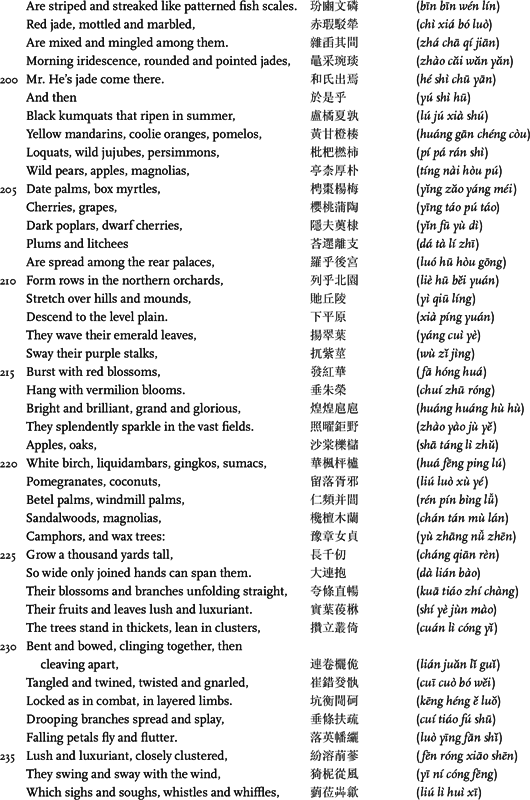

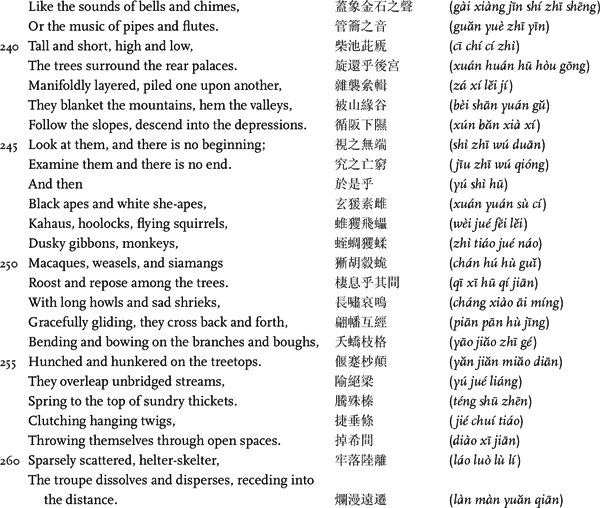

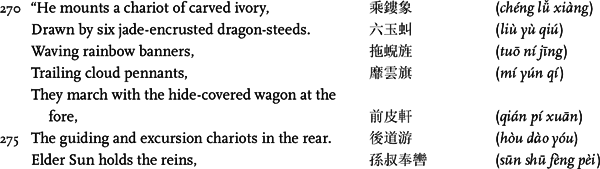

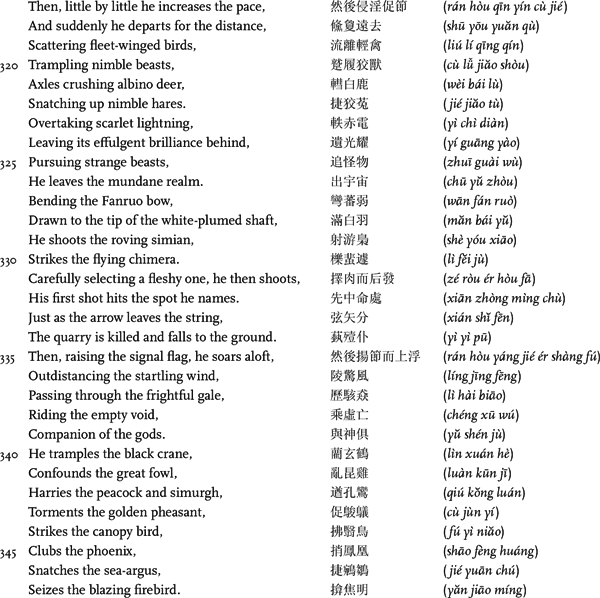

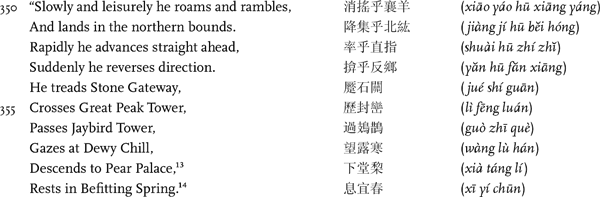

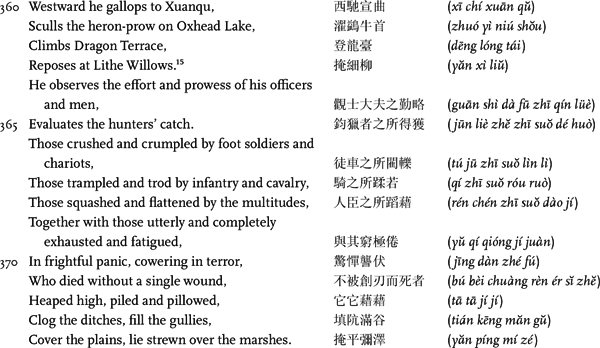

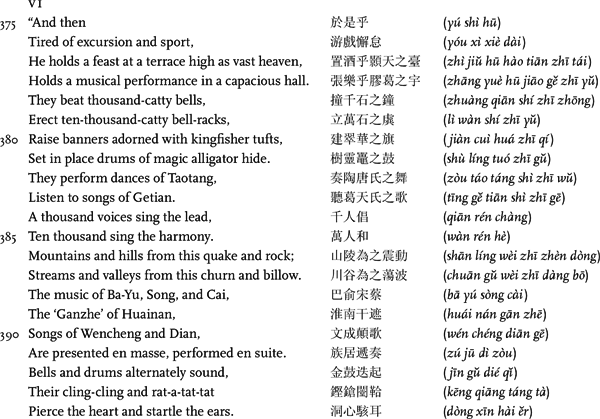

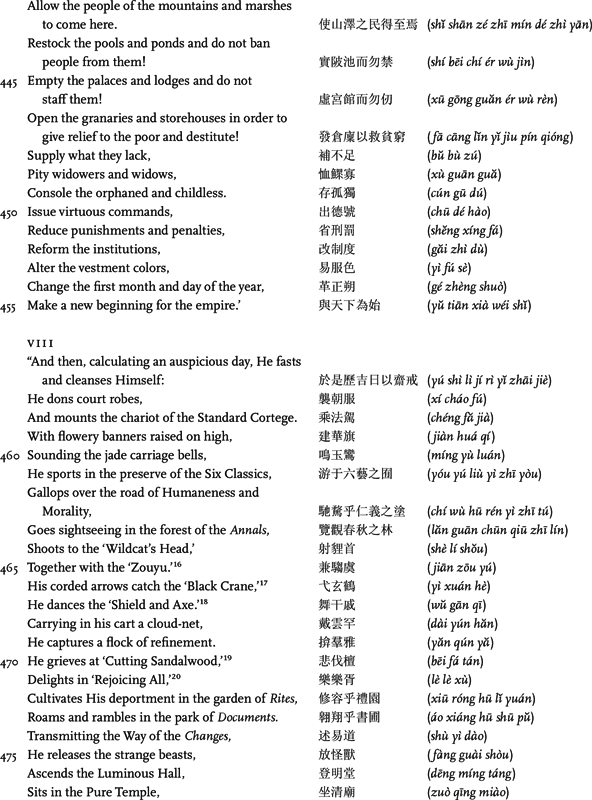

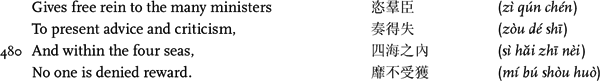

“Fu on the Imperial Park” begins with Lord No-such admonishing the emissaries of Chu and Qi for failing to “elucidate the duties of ruler and subject or to correct the ritual behavior of the vassal lords.” He accuses them of “competing over the pleasures of excursions and games, the size of parks and preserves, wishing to overwhelm each other with wasteful ostentation and surpass one another in wild excesses.” Such things, he claims, only serve to defame one’s ruler and do injury to oneself. He then proceeds with the most lavish account of them all, a description of Shanglin Park. Most of the first part of the fu consists of a series of catalogs of rivers, water animals, birds, mountains, plants, land animals, palaces, stones and gems, trees, and the animals that dwell within them. He follows with an effusive portrayal of what purports to be a typical excursion-hunt, although virtually all of the account is full of hyperbole meant to impress the reader with the emperor’s power. At one point, the emperor soars aloft and, as a companion of the gods, chases fabulous creatures through the sky. At the end of this celestial journey, the emperor descends to earth, where he moves rapidly through palaces and towers, and halts at a hall where he holds a banquet accompanied by song and dance.

In the midst of merriment and intoxication with wine, the emperor suddenly becomes lost in contemplation. As he reflects on the extravagance of his excursions, he fears that his successors will imitate his behavior. Resolving to abandon the activity, he dismisses hunters and revelers, and opens the park for the use of the common people. He now resolves to turn his attention to matters of state. He declares that he will model his conduct on the Confucian classics and that he will perform the proper rituals. By this action, the emperor becomes the equal of the great sage-rulers of antiquity, and thus he is superior to the princes of Chu and Qi, who are portrayed in the “Fu of Sir Vacuous” as rulers who sacrificed the welfare of the common people to their own pursuit of idle pastimes. At this point, Sir Vacuous and Master Improbable are overwhelmed and speechless. When they finally manage a reply, they say, “Your humble servants have been stubborn and uncouth, and ignorant of the prohibitions. Now this day we have received your instruction. We respectfully accept your command.”

The emperor for whom Sima Xiangru wrote “Fu on the Imperial Park,” Emperor Wu, ascended the imperial throne at the age of sixteen and ruled for more than half a century, from 140 to 87 B.C.E. During Emperor Wu’s reign, the Han fully consolidated its power internally and began to expand into new territories. Emperor Wu’s generals led military expeditions, which gained the Han control over new territory in the northeast, southeast, southwest, and west. Emperor Wu’s expeditions to what the Chinese of the Han called the Western Regions increased Chinese knowledge of Central Asia and opened trade routes that brought countless precious objects, rare animals, and plants to the imperial storehouses and imperial park. The era of Emperor Wu was an age of great pride in the might and magnificence of the empire, and much of the cultural activity of the period is fundamentally “imperial.” Thus during this period, the religious rites, education, philosophical thought, art, music, and literature were all related in important ways to the institution and person of the emperor.

“Fu on the Imperial Park” is a type of fu called dafu (literally, large fu). Such pieces are called “large” because they are long, but also because they are on grand topics such as capitals, palaces, and parks. The dafu usually have a tripartite structure consisting of a “head” (shou), “middle” (zhong), and “tail” (wei). In the head, the poet introduces the topic. In “Fu on the Imperial Park,” the head occupies all of part I, in which the imperial spokesman Lord No-such belittles the expositions of the emissaries from Chu and Qi and then proposes to describe for them the superior features of Shanglin Park. The middle is the longest section of the fu, which extends for some four hundred lines from part II through part X. In this section, Sima Xiangru describes the park’s terrain, lists the various creatures and objects that are found there, and gives a brief account of the imperial hunt. The tail, which begins with part XI, is the moralistic conclusion, in which the emperor is portrayed as repudiating the extravagance of the park and transforming himself into a dutiful sovereign who shows concern for the livelihood of his people.

Although Sima Xiangru did not compose “Fu on the Imperial Park” for any particular occasion, it is a celebratory poem. During the Former Han, the court held elaborate spectacles, including hunts, military reviews, pageants, and ceremonies. Most of these events were celebrated in verse, and the favored verse form was the fu. In all these activities, one can see a common aesthetic, what I have termed “beauty of the large.” The first occurrence of this term is in “Fu on the Imperial Park.” At the beginning of the piece, Lord No-such lectures the representatives from Chu and Qi for failing to discuss the proper duties of ruler and subject and to admonish their lords for their dissolute behavior. He then asks them: “Have you not seen the beauty of the large? Have you not heard of the Imperial Park of the Son of Heaven?”

The term that is translated as “beauty of the large” is ju li. The second part of the expression is the word li, which literally means “beauty,” but also implies the idea of brilliance, splendor, and display. The word ju, which I have translated as “large,” actually describes a size greater than simply “large.” In describing people, it means a person who is larger than ordinary persons—that is, a giant. In his use of ju, Sima Xiangru perhaps wished to convey the idea that the beauty of the imperial park is something grander and larger than that of other royal parks. In this sense, ju means “monumental” or “colossal.” One could also translate ju li as “monumental beauty” or “colossal beauty.”

The aesthetic of the large is clearly reflected in the courtly fu of the Emperor Wu period. In “Fu on the Imperial Park,” Sima Xiangru presents an elaborate description of the imperial park and the spectacles that take place there. Sima Xiangru portrays the imperial park as a locus of imperial prestige and majesty. He praises the park and the activities that take place there as a way of celebrating imperial splendor and power. The purpose of the catalogs of rare creatures and luxury goods that he includes in his fu was to provide concrete evidence of the Han court’s power and prestige. The park also was the major center for conducting military reviews and maneuvers. The grand structures of the park, and the military parades and hunts staged there, served to impress visitors, particularly those from foreign places, with the might and magnificence of the Han imperium.

The aesthetic that informs the catalogs of “Fu on the Imperial Park” is that of fullness, all-inclusiveness, abundance, and amplitude. The Han fu poets replicated in their fu the desire of the Han imperial court to fill the park with as many things—precious objects, animals, birds, plants—as possible. This tendency to celebrate plenitude is reflected in the following passage from the Later Han fu writer Zhang Heng (78–139), who says that the plants, animals, and birds in the park were so numerous that they could not all be counted:

Plants here did grow;

Animals here did rest.

Flocks of birds fluttered about;

Herds of beasts galloped and raced.

They scattered like startled waves,

Gathered like tall islands in the sea.

Bo Yi would have been unable to name them all;

Li Shou would have been unable to count them all.

The riches of the groves and forests—

In what were they lacking?21

The attempt of the fu writer to provide an exhaustive account imbues the fu with amplitude and all-inclusiveness, which E. M. W. Tillyard has identified as a quality of the “epic spirit.”22 Completeness, comprehensiveness, and immensity are as important to the “large fu” as they are to the epic. The enumeration of the profusion of things is a distinguishing feature of the dafu. The fifth-century Chinese literary critic Liu Xie (ca. 465–ca. 522) said that Sima Xiangru’s “Fu on the Imperial Park” achieved beauty because of its profusion of things “grouped by kind”—that is, his catalogs.23 Han fu writers themselves speak about this feature of the genre. For example, Yang Xiong (53 B.C.E.–18 C.E.) says the following about the process of writing a fu: “[The writer of a fu] must speak by setting forth things by kind. He uses the most luxuriant and ornate language, grossly exaggerates and greatly amplifies, striving to make it such that another person cannot add anything to it.”24 Yang Xiong calls attention to the full and overflowing quality of the fu, in terms of both its style and its content. His statement that one should fill up the poem with catalogs of names and a profusion of words to the point that no one could think of anything else to add is a reflection of the aesthetic of the large that dominates courtly fu writing.

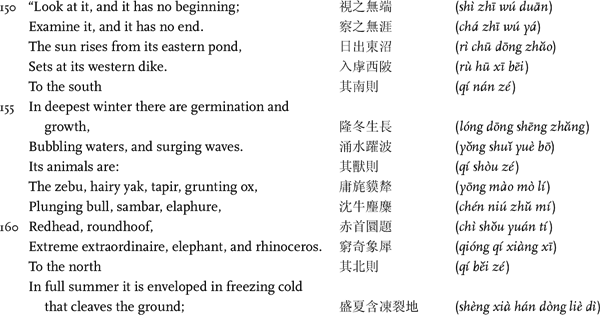

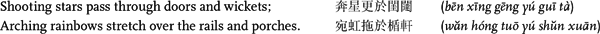

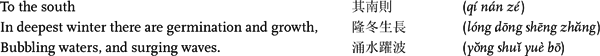

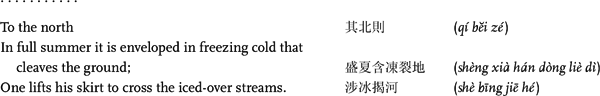

There is even a statement attributed to Sima Xiangru that eloquently expresses the fu aesthetic of completeness, totality, wholeness, and amplitude: “[T]he heart of a fu writer embraces the entire universe and broadly observes humans and things.”25 This statement is usually understood to mean that the fu writer attempts to create an exhaustive definition of his subject. Thus “Fu on the Imperial Park” is more than a simple description of the hunting park; it is, in effect, a praise poem to the Han dynasty and its ruler. A distinctive feature of Sima Xiangru’s style is the frequent use of lavish description and overstatement. Liu Xie termed this quality “exaggerated ornamentation” (kua shi). According to Liu Xie, this practice began with the Chu poet Song Yu (fl. third century B.C.E.) and reached its peak in what he called the “eccentric effusions” of Sima Xiangru.26 One of Sima Xiangru’s favorite devices of exaggerated ornamentation was hyperbole. Thus Shanglin Park’s lodges are so high:

The park extends so far that it has separate seasons in its northern and southern halves:

The park is so large:

The effect of these exaggerations is to demonstrate that the park and the Han emperor occupy the center of the cosmos, and that everything radiates from the seat of imperial power. Thus Shanglin Park, in effect, stands pars pro toto for the empire at large, and the panoply of rare and exotic objects that are contained in it are representations of the profusion of marvelous things that exist within the Han cultural sphere. As such, they evoke associations with the magnificence and might of the Han empire. Although Sima Xiangru’s rhapsody contains warnings to Emperor Wu about the folly of ostentation and extravagance, they are secondary to his lavish and flattering portrayal of the institution and person of the emperor.

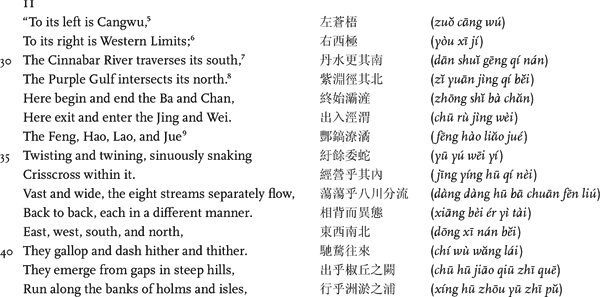

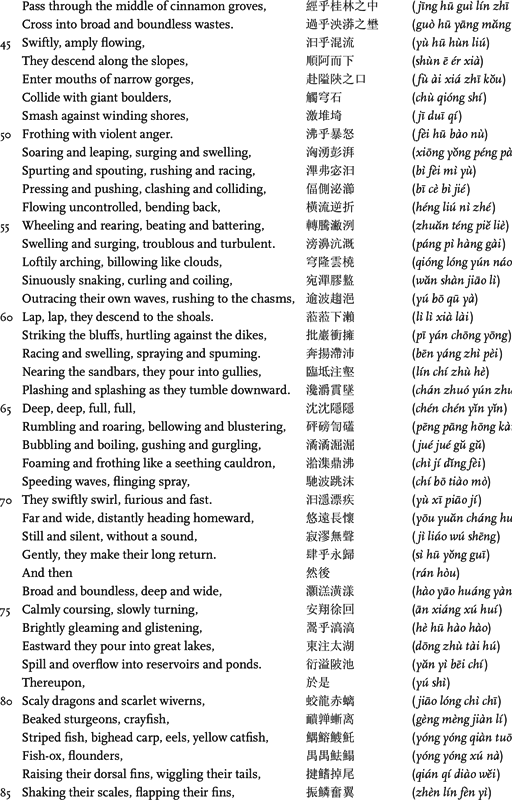

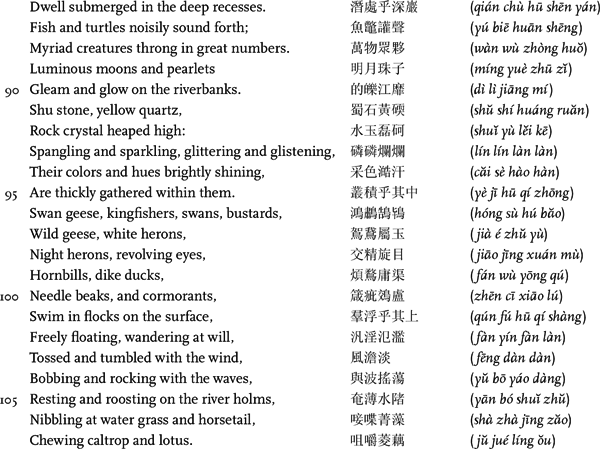

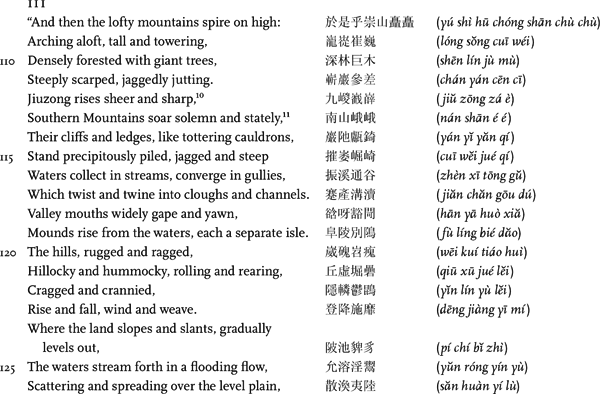

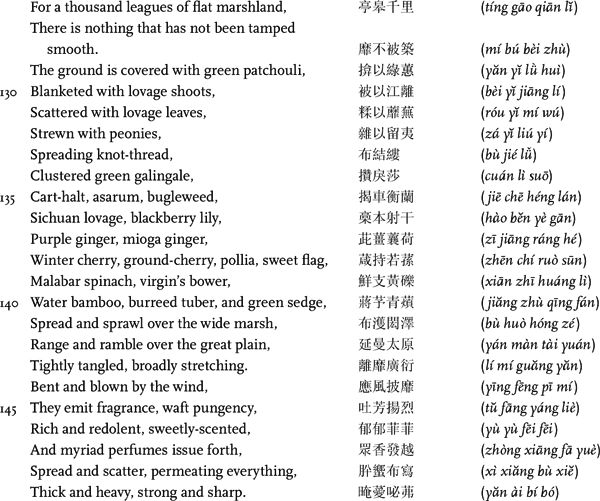

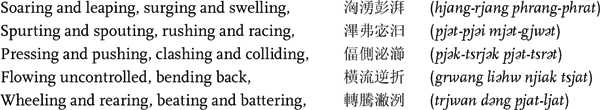

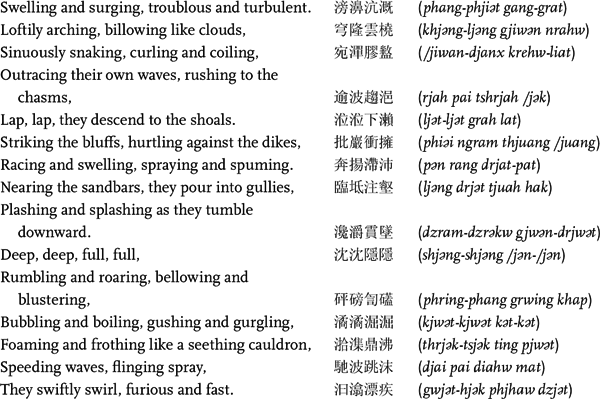

Another important feature of the fu is the quality known as pu or puchen. During the Han period, the word fu was often explained with homophones that basically have the same meaning, “to spread out” or “to display”: fu (phjah), bu (pak), and pu (phjuoh). During the Six Dynasties period, literary critics began identifying “display” as a defining feature of the fu genre. For example, Zhi Yu (d. 211) said that “fu is a term meaning ‘display,’” and fu is “a means by which the writer devises images and exploits language to the utmost to display his intent.”27 Liu Xie, in the Wenxin diaolong (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons), makes “display” an essential stylistic feature of fu composition: “Fu means to display: to display ornament and exhibit refinement, to give form to an object and express intent.”28 This display quality of the fu I term “epideictic.” The word “epideictic” is derived from the Greek word meaning “display,” and thus it is a good parallel with the Chinese terms pu and puchen. In the Han fu, the epideictic style is characterized by extensive cataloging, use of polysyllabic descriptive expressions, and repetition of synonyms. The following passage, which describes the rivers in the park, is a good example of the epideictic style:

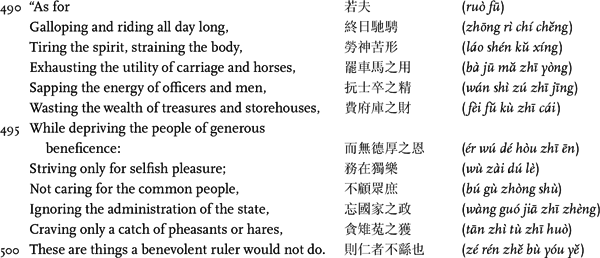

The transcription in the right-hand column is an approximation of the pronunciation during the Han.29 Its purpose is to call attention to the rhyming and alliteration, which is not always evident in modern Mandarin pronunciation. For example, the two syllables in bice do not rhyme in modern Mandarin pronunciation, but, in the Han dynasty Chinese pjək-tsrjək, they rhyme perfectly. Similarly, the modern Mandarin hangxie does not alliterate, but the Han dynasty reading gang-grat does. The phonetic representation of the passage shows the strong auditory quality of the fu.

Thus Sima Xiangru employed numerous alliterative and rhyming binomes: xiongyong (hjang-rjang [soaring and leaping]), pengpai (phrang-phrat [surging and swelling]), bifei (pjət-pjəi [spurting and spouting]), bice (pjək-tsrjək [pressing and pushing]), and pielie (phat-ljat [beating and battering]). Some of the expressions are synonyms, such as juejue (kjwət-kjwət) and gugu (kət-kət), both of which describe the bubbling and frothing of the waters. They are also probably onomatopoeic expressions.

The presence of so many alliterative and rhyming words in this passage provides evidence for another important quality of the fu in the Han period—its oral, recitative character. The primary medium of presentation of fu at the Former Han court was oral. Although we do not know whether “Fu on the Imperial Park” was actually performed after Sima Xiangru completed it, we do know that Emperor Wu employed professional rhapsodes, who not only recited but also extemporaneously composed fu for various court occasions. One of Emperor Wu’s favorite rhapsodes was Mei Gao (fl. ca. 140 B.C.E.), who was at the Han court at the same time as Sima Xiangru. Mei Gao probably was the most prolific fu writer of the Former Han. A catalog of the imperial library compiled at the end of the Former Han dynasty recorded 120 fu under his name.30 Regrettably, none of his works survives. According to his biography in the Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty), Mei Gao

accompanied the emperor when he went to Sweet Springs, Yong, and Hedong; made inspection tours of the east; performed feng sacrifices on Mount Tai; diked the break at Xuanfeng Temple on the Yellow River; went sightseeing at the touring palaces and lodges of the Three Capital Districts; visited mountains and marshes; and participated in fowling, hunting, shooting, chariot driving, dog and horse races, football matches, and engravings. Whenever there was something that moved His Highness, he immediately had Mei Gao rhapsodize [fu] on it. He composed quickly, and no sooner received the summons than he was finished. Thus, the pieces he rhapsodized are numerous.31

Although the text does not specifically state that Mei Gao chanted the poems, the fact that it does use fu in its verbal sense (to fu something, to recite a poem about, to chant), as well as the speed with which he composed, suggest that at least some of his fu were extemporaneous oral compositions.

The textual history of “Fu on the Imperial Park” also tells us something about the oral quality of the piece. There are two early versions of the poem, one in the Shiji (Records of the Grand Scribe), compiled by Sima Qian (145–86? B.C.E.), and the other in the Han shu, compiled by Ban Gu (32–92). Although the Shiji antedates the Han shu, through textual analysis, scholars have determined that the version of “Fu on the Imperial Park” included in the Han shu is earlier than that found in the Shiji. Many of the differences between the two texts involve the writing of alliterative and rhyming compounds as well as the names found in the various lists of animals, birds, and plants. For example, where the Han shu writes 屬玉 (zhuyu), the Shiji gives 鸀鳥 + 玉 (zhuyu) for “white heron.” The latter form, which adds the “bird” classifier on the left-hand side, is clearly an emendation intended to add a semantic element to the graph. A large number of the words in the History of the Han Dynasty do not have these semantic classifiers. It should be noted that when Sima Xiangru composed his fu, there were no standard forms for writing many words, especially the rare and difficult expressions that occur in “Fu on the Imperial Park.” Because many of the words that Sima Xiangru used did not have standard orthography, the original text of his fu must have contained numerous graphs that we probably would not easily recognize today. It is quite probable that the poet simply transcribed the words based solely on their sounds. Thus this would explain the absence of semantic classifiers in the Han shu version. In addition, if the fu were recited, as many scholars now believe was the case, the poet would have transcribed it phonetically using homophonous graphs to represent the unusual and rare words.

NOTES

1. In the Zhou period, various states were designated as “defensive barriers” of the Zhou kingdom. Qi was the defensive barrier in the east.

2. The modern romanizations of the verse part of this poem were added by the editor.

3. Sushen was a non-Chinese state probably located on the Liaodong Peninsula.

4. This line refers to the king of Qi’s hunts in Qingqiu, a foreign kingdom located in either the China Sea or Korea.

5. Cangwu refers to Jiuyi Mountain, located in modern Hunan. This is the traditional location of the burial place of the legendary emperor Shun. However, this direction is to the south, rather than the east, of Shanglin Park. Thus some scholars have speculated that an artificial mountain named Cangwu was constructed in the eastern limits of the park.

6. Western Limits is the name for the western terminus of the Han empire. A river named Bin flowed through this area, and it is possible that Shanglin Park had a replica of it.

7. The Cinnabar River probably flowed to the south of Shanglin Park.

8. Purple Gulf should be the name of a river located to the north of the park; however, the exact location of this river is not certain.

9. Lines 32–34: the Ba, Chan, Jing, Wei, Feng, Hao, Lao, and Jue are rivers that flowed from the southern part of the park north to the Wei River.

10. Jiuzong Mountain is located about thirty miles northwest of Chang’an.

11. The Southern Mountains are the Zhongnan Mountains, located directly south of Chang’an.

12. Wo Quan is the name of an immortal.

13. Lines 354–358: the Stone Gateway, Great Peak Tower, Jaybird Tower, Dewy Chill Lodge, and Pear Palace were all in the Sweet Springs Palace, located about seventy-five miles northwest of Chang’an.

14. Befitting Spring was located in the eastern part of the imperial park.

15. Lines 360–363: Xuanqu Palace was located near Kunming Pond, which was an artificial lake in the park just to the west of Chang’an. Oxhead Lake and Dragon Terrace were located in the western part of the park. Lithe Willows was a viewing tower located to the south of Kunming Pond.

16. “Wildcat’s Head” and “Zouyu” were two musical pieces that were played for the archery performance of the emperor and vassal lords, respectively.

17. “Black Crane” is the name of a dance composition reputedly composed by the ancient sage-ruler Shun.

18. “Shield and Axe” was an ancient military dance.

19. “Cutting Sandalwood” is a poem in the Book of Poetry that is traditionally interpreted as criticizing greedy, incompetent officials who deprived worthy men of their rightful positions.

20. “Rejoicing All” is a phrase from a poem in the Book of Poetry that describes the vassal lords coming to court to receive favors from the ruler.

21. Xiao Tong, comp., Wen xuan, or Selections of Refined Literature, vol. 1, Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals, trans. David R. Knechtges (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982), 207, with minor changes.

22. E. M. W. Tillyard, The English Epic and Its Background (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), 6–8.

23. Liu Xie, Wenxin diaolong (The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons) (Sibu beiyao ed.), 2.14b.

24. Quoted in Ban Gu, Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1962), 87B.3575.

25. Quoted in Xijing zaji (Miscellaneous Notes on the Western Capital) (Sibu congkan ed.), 2.4a.

26. Liu Xie, Wenxin diaolong 8.4a.

27. Zhi Yu, “Wenzhang liubie lun” (Treatise on Literature Divided by Genre), in Zhongguo lidai wenlun xuan (An Anthology of Writings on Literature Through the Ages), ed. Guo Shaoyu (1962; repr., Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju, 1979), 157.

28. Liu Xie, Wenxin diaolong 2.13a.

29. I base the reconstructions on W. South Coblin’s studies of Western Han phonology: “Notes on the Western Han Initials,” Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies 14, nos. 1–2 (1982): 111–132, and “Some Sound Changes in the Western Han Dialect of Shu,” Journal of Chinese Linguistics 14, no. 2 (1986): 184–225.

30. Ban Gu, Han shu 30.1749.

31. Ban Gu, Han shu 51.2367.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH, FRENCH, AND GERMAN

Gong Kechang. “The Poet Who Laid the Foundation for the Fu: Sima Xiangru.” In Studies on the Han Fu, translated and edited by David R. Knechtges, with Stuart Aque, Mark Asselin, Carrie Reed, and Su Jui-lung, 132–162. American Oriental Series, vol. 84. New Haven, Conn.: American Oriental Society, 1997.

Hervouet, Yves. Le Chapitre 117 du “Che-ki” (Biographie de Sseu-ma Siang-jou). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1972.

———. Un poète decour sousles Han: Sseu-ma Siang-jou. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1964.

Kern, Martin. “The ‘Biography of Sima Xiangru’ and the Question of the Fu in Sima Qian’s Shiji.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 123, no. 2 (2003): 303–316.

Knechtges, David R. The Han Rhapsody: A Study of the Fu of Yang Hsiung (53 B.C.–A.D. 18). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Watson, Burton, trans. Chinese Rhyme-Prose: Poems in the Fu Form from the Han and Six Dynasties Periods. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.

Xiao Tong, comp., Wen xuan, or Selections of Refined Literature. Vol. 1, Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals. Translated by David R. Knechtges. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982.

———. Wen xuan, or Selections of Refined Literature. Vol. 2, Rhapsodies on Sacrifices, Hunting, Travel, Sightseeing, Palaces and Halls, Rivers and Seas. Translated by David R. Knechtges. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

———. Wen xuan, or Selections of Refined Literature. Vol. 3, Rhapsodies on Natural Phenomena, Birds and Animals, Aspirations and Feelings, Sorrowful Laments, Literature, Music, and Passions. Translated by David R. Knechtges. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Zach, Erwin von, trans. Die chinesische Anthologie: Übersetzunge nausdem “Wen Hsüan.” 2 vols. Edited by Ilse Martin Fang. Harvard-Yenching Studies, vol. 18. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958.

CHINESE AND JAPANESE

Cao Daoheng 曹道衡. Han Wei Liuchao cifu 漢魏六朝辭賦 (The Fu of the Han, Wei, and Six Dynasties). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1989. Reprint, Taipei: Qunyu tang, 1992.

Chien Tsung-wu 簡宗梧. Hanfu yuanliu yu jiazhizhi shangque 漢賦源流與價值之商榷 (On the Origins and Value of the Han Fu). Taipei: Wen shi zhe chubanshe, 1980.

———. Sima Xiangru Yang Xiong jiqi fu zhi yanjiu 司馬相如揚雄及其賦之研究 (Studies of Sima Xiangru and Yang Xiong and Their Fus). Taipei: Chien Tsung-wu, n.d.

Fei Zhengang 費振剛, Hu Shuangbao 胡雙寶, and Zong Minghua 宗明華, eds. Quan Hanfu 全漢賦 (Complete Han Fu). Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 1993.

Gong Kechang 龔克昌, ed. Quan Han fu ping zhu 全漢賦評注 (Complete Han Fu, with Criticism and Commentary). 3 vols. Shijiazhuang: Huawen wenyi chubanshe, 2004.

———. Zhongguo cifu yanjiu 中國辭賦研究 (Studies of the Chinese Rhapsody). Jinan: Shandong daxue chubanshe, 2003.

Gong Kechang and Su Jui-lung 蘇瑞隆. Sima Xiangru 司馬相如. Shenyang: Chunfeng wenyi chubanshe, 1999.

Jin Guoyong 金國永. Sima Xiangru ji jiaozhu 司馬相如集校注 (Commentary on the Collected Works of Sima Xiangru). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1993.

Li Xiaozhong 李孝中, ed. Sima Xiangru ji jiaozhu 司馬相如集校 (Commentary on the Collected Works of Sima Xiangru). Chengdu: Ba Shu shushe, 2000.

Ma Jigao 馬積高. Fushi 賦史 (History of the Fu). Shanghai: Guji chubanshe, 1987.

Nakajima Chiaki 中島千秋. Fu nos eiritsu tot enkai 賦の成立と展開 (The Rise and Development of the Fu). Matsuyama: Seki Hironari, 1963.

Wan Guangzhi 萬光治. Hanfu tonglun 漢賦通論 (General Survey of the Han Fu). Chongqing: Ba Shu shushe, 1989.

Zhu Yiqing 朱一清 and Sun Yizhao 孫以昭, eds. Sima Xiangru ji jiaozhu 司馬相如集校注 (Commentary on the Collected Works of Sima Xiangru). Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1996.