7

7

The period from the second half of the fifth century to the first half of the sixth century in many ways represents a watershed in the evolution of classical Chinese poetry. During the Yongming reign (483–493) in the Qi dynasty (479–502), a group of poets devoted themselves to creating euphony by balancing the tones of Middle Chinese prosody. Although not universally followed in their own time, the rules they devised, honored and perfected by Tang dynasty poets, became the basis of so-called regulated verse (lüshi) and exerted an enormous influence on later Chinese poetry. One of the initiators of prosodic innovation was Xie Tiao (464–499), an aristocrat whose life was cut short at age thirty-five by his refusal to participate in a palace coup.

The changes that occurred in classical Chinese poetry, however, went far beyond tonal euphony. During the long and peaceful rule of Liang Wudi (Emperor Wu of the Liang [r. 502–549]), a devout Buddhist, southern China witnessed an age of splendid cultural achievements with unprecedented literary and religious activities. The literary salon of Crown Prince Xiao Gang (503–551) was the site of an altogether new poetry, named gongti shi (palace-style poetry) after the Eastern Palace, the official residence of the crown prince. Denounced by Confucian moralists as decadent and often mistakenly described as a poetry dedicated to the portrayal of court ladies and romantic love, it was, in fact, a poetry informed by a Buddhist vision of the illusory nature of the material world and characterized by a prolonged, focused, and illuminating gaze at physical reality.

Xiao Gang, also known as Emperor Jianwen of the Liang (r. 549–551), was probably one of the most underestimated and misunderstood classical Chinese poets. He spent most of his youthful years as regional governor and was appointed crown prince in 531. In 548 Hou Jing, a northern general who had defected to the Liang, turned on his benefactors and, in the following year, captured the Liang capital. Emperor Wu of the Liang died shortly thereafter, and Xiao Gang ruled for two years as a puppet emperor under Hou Jing before being murdered by Hou Jing’s men. Yu Xin (513–581), the most famous member of Xiao Gang’s salon, spent the second half of his life in the north after the south had been devastated by the Hou Jing Rebellion.

XIE TIAO

Belonging to the same illustrious clan as the famous landscape poet Xie Lingyun (385–433), Xie Tiao nevertheless achieved a completely different style from that of his senior and had a more visible impact on the development of the regulated verse of the Tang.

[XQHWJNBCS 2:1425]

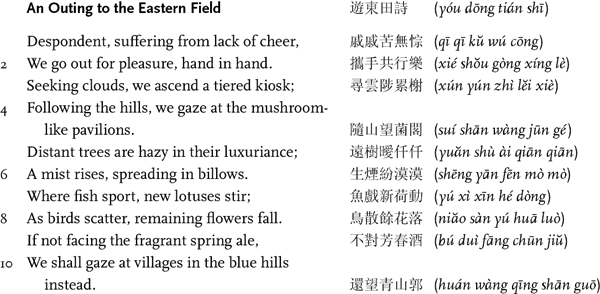

Less dense in diction than the works of his Liu Song predecessors, Xie Tiao’s poems often flow with an easy grace. Although still far from Tang regulated verse, “An Outing to the Eastern Field” comes close in terms of its brevity (ten lines as opposed to the sixteen or twenty lines of an average Xie Lingyun poem) and its attention to tonal euphony. The third couplet, for instance, is a perfect example of tonal patterning, with deflected and level tones alternating in the key positions in the first line of the couplet (second and fourth characters) and then level and deflected tones used in the corresponding positions in the following line.

The pleasurable outing is set against a background of mysterious melancholy—the poet never tells us what it is that makes him despondent. The Eastern Field was at the foot of Zhong Mountain, where Crown Prince Wenhui (458–493) of the Qi had constructed a luxury villa. Xie Tiao himself was said to have owned a villa in the same area. The poet claims that he and his friend ascend the lofty terrace to seek clouds, but once they climb to the top, a mist rises and spreads everywhere; along with the lushly growing trees, it blocks the poet’s view of the distant vista.

Perhaps because of the obstruction of his view, the poet, in the fourth couplet, turns his eyes to a scene close at hand. The new growth of the lotus leaves indicates the season: it is early summer. The stirring of the new lotus leaves leads the poet to notice the playing fish; the “sport” of the fish, a symbol of marital happiness and fertility, is imbued with sexual undertones. The liveliness and vitality of nature are, however, soon offset by a scene of dispersal and destruction. Following the principle of the parallel couplet, which demands that the reader understand the second line of a couplet in the same way as the first line, we are able to construct the causal relationship between the scattering of the birds and the falling of the blossoms from the tree; that is, it is the movement of the birds that shakes the flowers off the branches, and it is most likely the human presence—the approach of the poet and his friend—that has startled the birds. The flowers are mere remnants of their former splendor (and as such, fall easily): as summer begins and lotus grows, spring is coming to an end, and tree blossoms are fading away. Even as the fish are mating and the lotuses are sprouting new leaves, there are withering and death. Or, if we turn the argument around, nature is ever renewing itself, and there is always new life (the tree will blossom again next year)—not so, however, for human beings.

Moved by the cycle of nature he observes, the poet thinks of drinking spring ale, a gesture reminiscent of “Duan ge xing” (Short Song) by the Jian’an poet Cao Cao (155–220): “Facing the ale, one should sing, / How long does human life last?” Thoughts of mortality and the impermanence of things may have initially driven the poet out to make merry on a fine late-spring day, but nature turns out to be not so much a consolation as a reminder of the brevity of human life. While it is the poet’s vision that connects all the things in nature and makes them into self-contained scenes in well-crafted couplets, there is an irreconcilable difference between man and nature that marks the human presence in the landscape as essentially alien. All that is left for the poet to do is to “gaze” (wang) from a distance, to be an onlooker able to appreciate but unable to participate in nature’s cycle of renewal.

The fourth couplet in Xie Tiao’s “An Outing to the Eastern Field” is a well-known parallel couplet in Chinese literary history. Its force comes from an intricacy that goes well beyond prosodic or formal perfection. It says much in a limited space, and what it says depends very much on how it is said.

[XQHWJNBCS 2:1420]

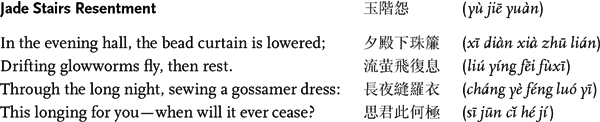

“Jade Stairs Resentment” (also translated as “Lament of the Jade Stairs” [C10.10]) is a quatrain (jueju), a verse form that had grown increasingly popular in the fifth to sixth centuries. Quatrains could be written in either five-or seven-syllable lines, although the full development of the seven-syllable quatrain occurred only in the Tang. There are several theories regarding the origin of jueju, one of which is based on the literal meaning of jue: “cut-off.” According to this theory, poets used to compose quatrains in response to one another, but when a quatrain received no response, it became “cut-off lines,” or jueju. During the Southern Dynasties, poets were fascinated with quatrain songs performed at court; these songs, although commonly regarded as folk songs, were often composed by court musicians as well as by aristocrats—sometimes the emperor himself. Xie Tiao’s quatrain, written to a yuefu title, was much more decorous than many of the quatrain songs in the court music repertoire, but it nonetheless belonged to such a tradition.

“Jade Stairs Resentment” describes a woman yearning for her absent beloved. Everything points to her loneliness: the lowering of the bead curtain implies that no one is coming and she is ready to retire, the flying and resting of the glowworms denote the passage of time, and the sewing of clothes through night suggests sleeplessness. Everything becomes a sign of something else that is kept well hidden, just like the resentment (yuan) of the woman. In lines 1–3 of the poem, the only word that might suggest the woman’s feelings is the term modifying “night,” which she perceives as “long.” This subjective sense of “long” prepares the reader for the last line, which breaks into a rhetorical question: “This longing for you—when will it ever cease?” The emotional power of the ending is very much intensified by the holding back of the first three lines.

For the informed reader, there is much more to the poem. In ancient Chinese lore, glowworms were believed to be produced by rotten grass—an indication that the lady’s courtyard is overgrown with weeds, yet another sign of her having no visitor. Since glowworms generally appear in late summer, their inclusion in the poem also functions as a marker of the season; autumn is a time not only of cooling passions but also of decay. Her resentment (yuan) of the absent lover is, therefore, strengthened by this subtle reminder of the brevity of youth, beauty, and human life itself. The larger temporal background, however, invests her sewing with a sense of irony: it is, after all, not a piece of warm clothing for the approaching cold weather but a “gossamer dress” appropriate only for summer. Does this anachronistic gesture bespeak a desperate desire to prolong the summer days? Or, as the ancient saying goes: “A woman adorns herself for the one who loves her.” Is she cherishing the hope that one day her beloved will return and that she will wear the dress for him? Or does the line suggest that she is soon to be put away like the gauze dress? In this quatrain, we hear the echo of a yuefu poem attributed to Lady Ban (ca. first century B.C.E.), in which a gossamer fan worries that it will be discarded once the cold season arrives. These interpretations do not necessarily exclude one another but altogether contribute to the richness of the image of sewing.

Xie Tiao’s poem exemplifies one particularly desirable quality for a quatrain, which is the use of simple language to create a world of complex nuances. Although one may still detect Xie Lingyun’s influence in some of Xie Tiao’s landscape poems, on the whole Xie Tiao’s poetry is characterized by a refined elegance that differs remarkably from Xie Lingyun’s exuberant density. Xie Tiao was one of the most revered poets in the early sixth century; his graceful, measured expression of feelings in simple, clear diction became the new poetic ideal for the court poets of the Liang dynasty (502–557).

XIAO GANG

The major theme of Xiao Gang’s poetry is transience. It is a Buddhist theme, but it is also a universally human one. To identify the major theme of Xiao Gang’s poetry as transience does not mean that Xiao Gang was always writing about the impermanence of human life; it means simply that he was intensely concerned with moments: his poetry uses words to arrest fleeting moments in the flow of time. It was perhaps for this reason that he was so taken by shadows and wrote about shadows so often in his poetry, as shadow marks a specific time of day, a particular moment. By portraying the world in terms of moments, Xiao Gang represented both its fragility and its aliveness. Many critics have accused Xiao Gang of being too delicate; in a gendered distinction of qualities, delicacy still suggests femininity, a quality considered unseemly in a man and doubly suspicious in a ruler. Such a view, however, mistakes an extraordinary power of observation for mere delicacy. In the end, the delicacy of Xiao Gang’s poems is no more than an extension of the vibrant and ephemeral world depicted in them.

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1947]

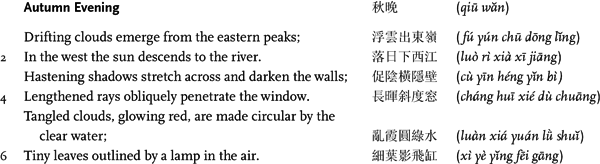

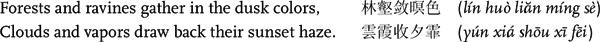

“Autumn Evening” depicts a particular time of the year and a particular time of the day. Both autumn and twilight are times of division as well as of transition and ambiguity: the heat of summer has not quite turned into the cold of winter; the day has ceased to be day, but the night has not quite begun. In the west, the sun is setting; in the east, where the moon should be, drifting clouds are pouring out from the mountains. Even as the last rays of the sun penetrate the window, shadows are gradually spreading over the walls, and darkness is closing in from all sides.

In the gathering darkness, two sources of light catch the poet’s attention. The tangled clouds, glowing with the red of sunset, are reflected in a circular pool, shining forth with a momentary splendor. The circularity of the pool also gives the tangled clouds a shape—a roundness that, in Buddhism, indicates perfection, be it the perfection of the Buddhist teachings or of enlightenment. In the next line, we see another light source: lamps are lit, which indicates the increasing density of the dark. The poet notices the dark silhouettes of tiny tree leaves outlined by the lamplight. Thus, in a world gradually sinking into shadows, the poet traces luminous patterns and forms, affirming an order created by human effort.

In these lines, we can see a peculiar vision of the world—and a peculiar way in which poetry is made to work. We may compare Xiao Gang’s fragmentary poem with couplets by previous masters, such as the couplet from “Zeng Wang Can” (To Wang Can), a poem by Cao Zhi (192–232):

[XQHWJNBCS 1:451]

or the couplet from Xie Lingyun’s poem “Written upon Returning over the Lake from My Meditation Lodge at Stone Cliff”:

[XQHWJNBCS 2:1165]

These couplets, although no less beautiful or poetic, are clearly of a different kind from Xiao Gang’s couplets, as they are more straightforward, more linear in their movement. In Xiao Gang’s poem, even the first couplet, which is the simplest of the three in its movement, requires a going back in reading for us to better grasp the picture, for we would not understand the significance of the clouds in the eastern sky until we are told that the sun has sunk to the river’s level in the west; only then do we realize that darkness is all around. The poem represents a moment when, at a time of decreasing visibility, vision is focused on even the smallest change in nature, and as a result, nature becomes illuminated, just as the lamplight delineates the dark shape of the tiny autumn leaves.

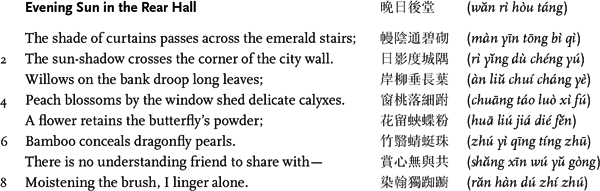

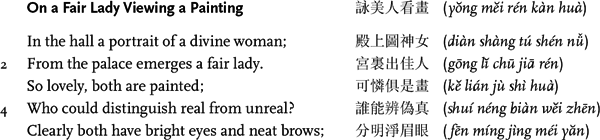

Another poem, “Evening Sun in the Rear Hall,” again opens with the movement of shadows:

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1955]

The “emerald stairs,” which are actually seen by the poet, and the remote corner of the city wall, which can only be imagined by the poet because he is in the rear hall, are linked by shifting shadows: just as the sun moves across the sky, so the shadows move across the earth. From this point on, the boundary between what is seen by the bodily eye and what is seen by the mind’s eye becomes blurred. “Willows on the bank” of a river, a distant scene, are juxtaposed with the “peach blossoms by the window,” a scene close at hand. Indeed, the poet is so close to the peach blossoms that he can see the shedding of their delicate calyxes. This also reminds the reader that, just as the day is advancing, springtime is also coming to an end.

The third couplet again sets side by side an image grounded in empirical experience and a semi-imaginary scene. According to the Bowu zhi (A Comprehensive Account of Things), a work by the Western Jin writer Zhang Hua (232–300) that records many fantastic phenomena: “On the fifth day of the fifth month [that is, mid-to late June], if one buries the head of a dragonfly under a west-facing window, after three days of not eating anything, it will turn into a green pearl.” Now, if a butterfly indeed has powder on its wings and may leave it on the flower petals, “dragonfly pearls” are no more than a figment of the poet’s imagination. Moreover, he claims that they are concealed by the growing bamboo, so that this fantastic image is negated as soon as it is evoked, and the reader is left wondering if that which is being concealed is actually there.

But even if it might be empirically true that a butterfly stains a flower with its powder, is it visible to even the most perceptive human eyes? Much of what is depicted in this poem seems more the product of the poetic imagination than of even the most careful observation. In this poem, the act of looking and seeing is also the act of visualizing and creating. Perception becomes indistinguishable from representation. Precisely for this reason, it is difficult to find an appreciative friend to share the scene with, for the scene is as much real as imagined, and visualization is always a private, individual act. Sitting alone in the late afternoon—with time flying away in the shifting shadows of the sun, darkness approaching, and springtime ending—Xiao Gang finds that the only enjoyable activity is to write.

Xie Lingyun, the great landscape poet of the fifth century, had once famously said that a fine hour, beautiful scenery, an appreciative friend (shangxin), and an enjoyable activity were four things hard to come by all at once. Indeed, the desire for an appreciative friend is so prominent in Xie Lingyun’s poetry that it became his hallmark. Xiao Gang’s poem both pays tribute to the earlier master and demonstrates the immense difference that separates the two: while Xie Lingyun’s poetry often attempts to offer a panoramic view of the landscape and creates an impression of all-inclusiveness and a cosmic vision, Xiao Gang’s intense gaze is focused on a much smaller sphere, and he resorts to the mind’s eye no less than to his physical vision to detect and construct the complex relations existing among the myriad things of the world apparently all standing alone. As Stephen Owen has said, “His was a poetry of beautiful, enigmatic patterns, often drawing the eye closely to some detail.”1

Beginning in the Qi dynasty, yongwu shi (poetry on things) became increasingly popular. It gradually developed into an important subgenre of classical Chinese poetry, continually practiced throughout history and, in fact, enjoying a place in modern poetry as well. Of Xiao Gang’s extant poetic collection, which contains over 250 poems, about one-sixth belong to the yongwu category. The usual yongwu poem of the Qi describes the characteristics of a given object and often ends with an appraisal of how the object may be of service to its human owner. As Cynthia Chennault has noted, “Instead of things that stand free in nature, the new trend of Southern Qi odes was to depict small decorative items which had incidental uses, such as musical instruments, utensils for a banquet, a lady’s toiletry articles, and so on.”2 And yet, it is noteworthy that only one-fifth of the approximately forty yongwu poems by Xiao Gang are about inanimate objects. Xiao Gang was far more interested in portraying natural phenomena or living things, from clouds and rain to horses, birds, flowers, and insects. They are not depicted as static, inanimate, and generic, but as specific, particular, and vulnerable to the ravages of time.

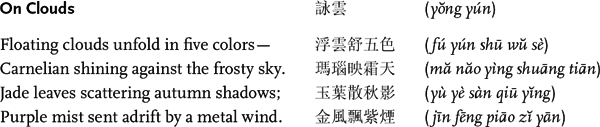

“On Clouds” is a fine example of Xiao Gang’s yongwu poetry:

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1953]

This poem shows Xiao Gang’s familiarity with the literary tradition and his ability to make it new. The first line evokes “Fuyun fu” (A Poetic Exposition on the Floating Clouds), by the Western Jin writer Lu Ji (261–303), in which he compares the clouds of “five colors” to lotus blossoms, rose of Sharon, agate, and carnelian. Lu Ji also describes the clouds as “jade leaves,” which are blown off “golden branches.” Noticeably, what Xiao Gang chooses to take from Lu Ji’s metaphors are not organic things of nature, such as lotus or rose of Sharon, but “carnelian” and “jade leaves,” to which he adds “a metal wind”—in Chinese cosmology, autumn is considered the season of metal, and so the autumn wind is also referred to as a “metal wind.” The result is striking, for the airy, constantly shifting forms of clouds are connected with the hard textures of minerals and metal. On the one hand, the poet uses words of insubstantiality, such as “floating,” “shadows,” and “mist”; on the other, those of solidity, like “carnelian,” “jade,” and “metal.” That the sky should be “frosty” intensifies the sense of coldness and hardness and accentuates the ethereality of the shape-changing clouds.

The clouds depicted in this quatrain are specifically autumn clouds. Real leaves wither and decay in autumn, but not these jade leaves. And yet, as the metal wind blows, even the jade leaves are scattered and turned into mere puff.

The jade leaves would have had a special resonance for Xiao Gang and his contemporaries, who grew up against an intensely Buddhist background, were devout Buddhist believers, and regularly attended Buddhist lectures. The Buddhist paradise, known as the Pure Land, is described as a land made of diamonds and decorated lavishly with the Seven Jewels, including agate, carnelian, jade, and gold (which, in Chinese, is the same word as “metal” [jin]). In the Pure Land, even trees are made of precious gems: of some trees, The Sutra of the Buddha of Infinite Life says the roots are made of diamonds, the trunks of gold, the branches of silver, the twigs of beryl, the leaves of lapis lazuli, the flowers of coral, and the fruits of red pearls; the sutra goes on and on in this manner. That trees should be made of various jewels might seem unnatural or artificial to some lay readers, and yet diamonds, silver, lapis lazuli, and coral are things of nature, as is organic vegetation. Being made of jewels only means that the trees in the Buddhist paradise do not wither and decay, as do trees in the mortal world; they are beyond the cycle of life and death. Xiao Gang was obviously fascinated by the blissful land sumptuously portrayed in the sutras. In another poem, “Xizhai xing ma” (Riding in the Western Residence), we see such a couplet:

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1950]

Viewed in the Buddhist context, Xiao Gang’s poem “On Clouds” becomes poignant. As the illusory jade leaves are scattered by the autumn wind, we see the contrast between the solidity and permanence of the diamond land inhabited by heavenly beings and the fragility of the human world inhabited by the poet—and us.

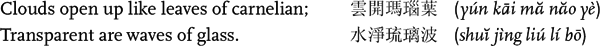

Many of Xiao Gang’s poems are informed by his intimate knowledge of Buddhist texts. The following poem, “On a Fair Lady Viewing a Painting,” recalls the Buddhist story of the mutual deception of a carpenter and a painter. The carpenter played a practical joke on his painter friend by making a wooden statue of a pretty girl, which the painter took to be real and fell in love with. Upon learning of his error, the painter decided to get back at the carpenter. He made a painting of his hanging himself, which looked so real that the carpenter was led to think that the painter had committed suicide. Terrified, the carpenter rushed to cut the rope—only to discover that it was an object in a painting. This story illustrates the fallacy of human perception and the unreal nature of the physical world. It is included in the Jinglü yixiang (Differentiated Manifestations of Sutras and Laws), a large Buddhist encyclopedia commissioned by Xiao Gang’s father, Emperor Wu of the Liang, in 516.

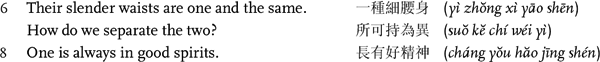

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1953]

In a rather humorous tone, Xiao Gang points out that both women—the one in the painting and the one viewing it—are “painted,” no doubt alluding to the court lady’s heavy makeup. The last couplet, as Kang-i Sun Chang has observed, underlines the “permanent value of art”: only the painted woman is always in good spirits.3 The modern reader may find it distasteful that Xiao Gang should treat the real woman as an object of art by comparing her to a painting; and yet, the contrast effectively brings out the vital energy and fragility of the human condition: unlike the painted beauty, the real woman may become sick, grow old, get angry or become sad, and easily lose her “good spirits,” which only a painted beauty is privileged to possess “always.” Indeed, for those who were saturated in Buddhist teachings and frequently attended Buddhist lectures, like the Liang royal family and members of the nobility, the very statement “One is always in good spirits” is tongue-in-cheek: painting is one of the best-known metaphors in the Buddhist scriptures for the illusive nature of the phenomenal world, and so the “permanence” of a painting is itself an illusion because it is relative, measured against the brevity of human life.

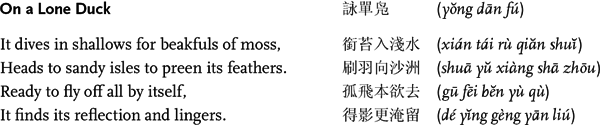

Buddhist doctrine teaches that when a child sees the moon in the water, he tries to grab it, while the wise adult laughs at the child for doing so. The wiser adult understands that the impulse to grab the moon in the water is owing to the child’s adhering too much to the sense of “I” and that of “what I see” as reality. In fact, “I” is constituted of the Five Skandhas (wuyin or wuyun)—form, feeling, perception, impulse, and consciousness—all essentially illusory and transitory. Considered in this light, the following yongwu poem by Xiao Gang, “On a Lone Duck,” seems to take on a more complicated meaning, as the lonely duck, enamored of its own reflection, is sadly deluded in its attachment to something insubstantial and unreal:

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1973]

The last line contains an unsolvable paradox: the poet suggests that the discovery of its own reflection prompts the duck to stay, and yet, its staying conditions the existence of the reflection. The illusion of having a companion (that is, its own reflection in the water) gives rise to fond attachment, but the attachment itself turns out to be the raison d’être for the illusion and its preservation. Cause and effect become hopelessly entangled.

Two general points need to be made about the reception and evaluation of Xiao Gang’s achievements as a poet. First, modern critics tend to focus their attention on Xiao Gang’s poems about palace ladies and boudoir life, but these poems take up less than half of his extant oeuvre, and their preservation is due primarily to their inclusion in the sixth-century poetic anthology Yutai xinyong (New Songs of the Jade Terrace), which was intended for an upper-class female readership. This is the only pre-Tang poetic anthology that has survived more or less intact to the present day. But when these poems are taken to represent the entire corpus of Xiao Gang’s largely lost writings, we are prevented from seeing that he has a much wider range. Second, while the modern feminist critique of voyeurism may be applied to some of Xiao Gang’s poems on women, it is worthwhile to remember that in appreciating the poetry of a different age, we should take its historical and cultural contexts into account. Xiao Gang lived in an intensely Buddhist era, and the key to understanding the larger significance of his poems is to remember that for Xiao Gang and his contemporaries, sensuous forms paradoxically bespoke the illusory, ephemeral nature of the phenomenal world. One of Xiao Gang’s most notorious poems on a beautiful woman taking a daytime nap is, as some Chinese scholars have pointed out in recent years, clearly influenced by the long versified account of Śākyamuni Buddha’s life (Acts of the Buddha), translated into Chinese by the monk Bao Yun (376?–449) in the fifth century. In the account, sleeping palace ladies remind Śākyamuni, who was then the crown prince just like Xiao Gang, that alluring forms of the physical world are but an illusion, and his determination to forsake the secular life is subsequently strengthened.

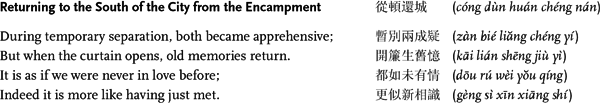

If we look beyond the conventional criticism of Xiao Gang either as a decadent prince indulging in sensuous pleasures or as a male chauvinist voyeur, we will notice some wonderful love poems in his collection, such as the quatrain “Returning to the South of the City from the Encampment.” This quatrain was written when the young Xiao Gang was serving as the governor of Yongzhou (in modern Hubei Province) between 523 and 530, during which period he carried on several military campaigns against the Wei, the enemy dynasty in northern China.

[XQHWJNBCS 3:1969]

Like many of his contemporary poets, Xiao Gang was skillful at producing a vignette and sketching a dramatic situation. In this poem, the poet describes the reunion with his beloved, and he chooses to focus on the moment when the lovers first set eyes on each other after a temporary parting. During their separation, they have been tortured by suspicion and fear about the inconstancy of the beloved; now that they are together again, there is a moment of pause before they rush into each other’s arms, a moment of hesitation, even abashment, before old memories revive and a new passion is awakened. Although the poem was written more than 1,500 years ago, the lovers’ sentiments as portrayed in it are fresh and familiar, as if it had been composed only yesterday.

YU XIN

Yu Xin grew up in the southern elite culture; his father, a famous poet, was one of Xiao Gang’s closest companions, and Yu Xin himself had enjoyed Xiao Gang’s favor and patronage. After the Hou Jing Rebellion, Yu Xin went to Jiangling (in modern Hubei) and served under Xiao Gang’s younger brother, Xiao Yi (Emperor Yuan of the Liang [r. 552–555]). In 554, Yu Xin was sent on a diplomatic mission to Chang’an (modern Xi’an), the Western Wei (535–556) capital, and was subsequently detained. While Yu Xin was there, Jiangling fell to the Western Wei army; on January 27, 555, Emperor Yuan was brutally killed. Shortly afterward, the new Liang emperor was deposed by a powerful southern general, Chen Baxian (Emperor Wu of the Chen [r. 557–560]), who founded the Chen dynasty (557–589), the last of the Southern Dynasties. Yu Xin was never able to return to his native land. The Western Wei was soon overthrown and replaced by the Northern Zhou dynasty (557–581), and Yu Xin held a number of official positions under the new regime. He was treated with affection and respect by the Zhou princes, who loved poetry, but the poems of Yu Xin’s later years are marked by sadness over the fate of the south and the Liang princes and by a profound sense of survivor’s guilt.

Yu Xin was a consummate southern court poet, a master of elegant, restrained expression, which was the legacy of the fifth-century aristocratic poet Xie Tiao. In Yu Xin’s later poems, the intricate parallelism developed by the Liang court poets is employed with a much simplified diction and an apparently casual ease, which, combined with his frequent description of a bleak, sparse northern landscape in autumn and winter, convey a particular emotional force. Nevertheless, Yu Xin manages to frame the intensity of his feelings with a cultivated grace that is the hallmark of the southern courtier, and his poetry achieves powerful poignancy precisely because of such decorous restraint. Yu Xin’s works not only became a model for the northern poets of the late sixth century, but also produced a far-reaching influence. Du Fu (712–770), the great Tang poet, was an admirer of Yu Xin and praised him in the following lines: “Yu Xin, all his life, was most forlorn: / In his old age, his poetry and rhapsodies moved rivers and passes.”

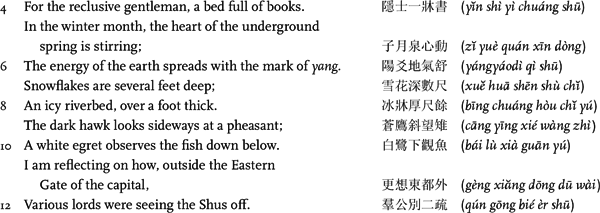

[XQHWJNBCS 3:2377]

“A Cold Garden: On What I See” has a deceptive title, for the poet is depicting not only what he sees but also what he does not see: underneath the several feet of snow and a frozen riverbed that human vision cannot penetrate, the “underground spring” is stirring and the “energy of the earth” is spreading. This optimistic statement is immediately undercut by the next couplet: a “dark hawk” is circling in the sky, flying so low that the poet can tell it is looking sideways, and a “white egret” is also searching for food. These birds of prey are waiting patiently for the snow and ice to melt so they can strike their victims—the pheasant and fish now being protected by the thick coverings of nature. The poet sees the movement of those creatures of prey and knows that it bears the sign of spring’s imminent arrival; he also knows that with the return of spring, there will be bloodshed and death. The poet’s thoughts turn to something beyond his garden: another time, another place, when the noble lords of the Western Han took leave of the two Shus—Shu Guang and Shu Shou (fl. first century B.C.E.)—the two imperial tutors who retired at the summit of their careers and were upheld as role models in “getting out before it was too late.”

The peaceful, erudite indoor pleasures—the walls painted with “roaming immortals,” the books in bed—are thus enclosed in a cold wintry landscape beset by lurking dangers, murderous plots, and small deaths. Nature is neither at peace nor in harmony; it is populated with creatures of prey and victims. The poet’s little house may be safe and warm, as opposed to the cold and harsh world outside, but he cannot help thinking warily of the arrival of springtime—a rare moment in Six Dynasties poetry indeed, when spring becomes so threatening and ominous. In the last couplet, the natural world and the social world are brought together in the poet’s mind: Yu Xin seems to be entertaining the possibility of withdrawing from public service like the two Shus. He is, in truth, reflecting on an escape route for himself, who is at the moment both protected and trapped, like a pheasant or a fish, by the deep snow and ice.

Yu Xin uses almost no allusions in the whole poem, except for a reference to the two Shus in the last couplet. And yet, the white egret observing the fish echoes a well-known story about Zhuangzi, in which the ancient philosopher Zhuangzi and his friend Hui Shi look at the fish swimming in the water and hold a famous discussion about “whether one knows if the fish are happy.” The irony here, of course, is how the fish might be swimming happily under the ice while completely ignorant of their menacing observer and the danger they face.

The political situation in the Northern Zhou court toward the last years of Yu Xin’s life was indeed unstable, as the ambitious minister Yang Jian (Emperor Wen of the Sui [r. 581–604]) garnered all power into his own hands. In 579, Yu Xin retired because of illness. In the following year, several of his former imperial patrons, including the prince of Teng, who had written a preface to Yu Xin’s collection of literary writings, were executed on Yang Jian’s orders. In 581, Yang Jian forced the abdication of the last Northern Zhou emperor and established the Sui dynasty (581–618).

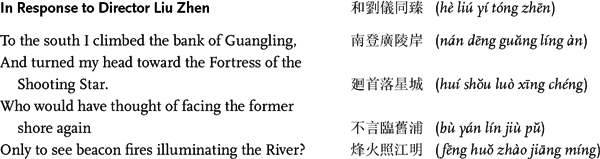

In the autumn of 581, the Sui emperor commanded a military campaign against the Chen dynasty in the south. Yu Xin’s friend Liu Zhen (d. 598), who had also served under the Liang in his youth, was sent along as the commander-in-chief’s secretary. The following quatrain, “In Response to Director Liu Zhen,” was apparently composed on this occasion. If so, it would have been one of Yu Xin’s last datable poems, for he died soon afterward in the same year.

In this quatrain of twenty characters, there are two place-names (which take up one-fourth of the poem): Guangling and the Fortress of the Shooting Star. The Fortress of the Shooting Star was to the west of Jiankang (modern Nanjing), the capital of the Liang, where Yu Xin had spent most of his youthful years. Guangling (modern Yangzhou) is located just to the north of the Yangtze River, very close to Jiankang. It had been conquered by the Zhou army two years earlier. Yu Xin, an old man now, did not take part in the military campaign undertaken in 581, and his description of Guangling and the Fortress of the Shooting Star was, as indicated by the title of the poem, imagined from his friend Liu Zhen’s perspective:

[XQHWJNBCS 3:2401]

The first two lines are directly taken from a well-known poem, “Qi ai” (Seven Sorrows), written by Wang Can (177–217). In 192, Wang Can was forced to flee the western capital Chang’an and go to the south during the chaos of the civil war. On his way there, he observed the devastation caused by years of fighting; before going on, he turned back and looked at the once prosperous metropolis once more:

To the south I climbed the slope of Ba Mound

and turned my head to gaze on Chang’an.

And I understood why someone wrote “Falling Stream”—

I gasped and felt that pain within.4

Ba Mound (Baling) was the tomb of Emperor Wen of the Western Han (r. 179–157 B.C.E.), and the allusion to his reign, a period characterized by peace and prosperity, was intended to bring out a poignant contrast with the present state of Chang’an. “Xia quan” (Falling Stream) is the title of a poem from the Shijing (The Book of Poetry) that, according to the traditional commentary, expresses a longing for a wise king:

Biting chill, that falling stream

that soaks the clumps of asphodel.

O how I lie awake and sigh,

thinking of Zhou’s capital.5

Yu Xin’s quatrain is therefore like a textual set of Chinese boxes, with one box containing another containing yet another. We should keep in mind, however, that these literary echoes would have been so obvious to Yu Xin’s contemporaries or any educated premodern Chinese reader that the quatrain, rich with associations, would have remained transparent.

Just as Wang Can had looked back at Chang’an from Ba Mound, Yu Xin imagined his friend ascending the riverbank at Guangling to gaze on the Fortress of the Shooting Star, which was an indirect way of referring to the old Liang capital, Jiankang. And yet, looking through historical sources, we find that the Shooting Star was not a walled city (fortress) after all; there was a Hill of the Shooting Star to the west of Jiankang, and that was the very place where the Liang troops had fought against and eventually overpowered Hou Jing’s rebel army. As a matter of fact, the Liang general who had set up a camp at the Hill of the Shooting Star was none other than Chen Baxian, who later forced the abdication of the last Liang emperor and founded the Chen dynasty. Was Yu Xin’s choice of place-name an acknowledgment of the irony of history? Or was it simply a way to avoid a painful direct reference to Jiankang? Or was it because the verbal image of the shooting star matched so beautifully with the real beaconfires raging along the Yangtze River?

In many ways, the city of Jiankang was indeed a Fortress of the Shooting Star, whose light, although brilliant, was transient in the course of human history. Remaining the capital of the south for three centuries, it was once the “jewel in the crown of south China’s commercial empire,” whose population “topped one million individuals, including Han Chinese, aboriginal peoples, and foreigners (especially merchants and members of the Buddhist Sangha).”6 During the long, peaceful, and prosperous reign under Xiao Gang’s father, Jiankang had reached a dazzling height of cultural glory. But even in Yu Xin’s day, Jiankang had already lost its former splendor; devastated by the Hou Jing Rebellion, its light had long dimmed. What Yu Xin did not know was that, eight years after his death, following the conquest of the Chen in 589, an edict by Emperor Wen of the Sui ordered the destruction of the entire city of Jiankang: “its walls, palaces, temples and houses were to be destroyed and the land returned to agriculture.”7 Yu Xin’s quatrain was prophetic in a way that he would never have wanted it to be. The star fell from heaven; once the raging beacon fires died out, it would be dark.

From the time he left Jiangling in 554 until his death in 581, as far as we can tell from the historical sources, Yu Xin not only never returned to the south, but never even got as close to Jiankang as Guangling. The quatrain, one of his last, envisions his old capital illuminated by a blazing light before being engulfed by darkness. The pathos lies not only in seeing one’s hometown torn apart by war and destruction, but also in witnessing the fall of an empire and the end of an age.

The Chinese like to situate a poem in the context of a poet’s life and times: indeed, without the background information, we would never have known what a poignant poem “In Response to Director Liu Zhen” is, and how much emotional power, intensified by restraint, is packed into a quatrain of twenty words. Yu Xin was the last of the Southern Dynasties masters. It would soon be the Tang, the golden age of Chinese poetry.

NOTES

1. Stephen Owen, trans. and ed., An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (New York: Norton, 1996), 326.

2. Cynthia Chennault, “Odes on Objects and Patronage During the Southern Qi,” in Studies in Early Medieval Chinese Literature and Cultural History: In Honor of Richard B. Mather and Donald Holzman, ed. Paul W. Kroll and David R. Knechtges (Provo, Utah: T’ang Studies Society, 2003), 332.

3. Kang-i Sun Chang, Six Dynasties Poetry (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986), 156.

4. Wang Can, “Qi ai” (Seven Sorrows), in Owen, Anthology of Chinese Literature, 252.

5. “Xia quan” (Falling Stream), in Owen, Anthology of Chinese Literature, 253.

6. Shufen Liu, “Jiankang and the Commercial Empire of the Southern Dynasties: Change and Continuity in Medieval Chinese Economic History,” in Culture and Power in the Reconstitution of the Chinese Realm: 200–600, ed. Scott Pearce, Audrey Shapiro, and Patricia Ebrey (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Asia Center Press, 2001), 35–36.

7. Arthur F. Wright, “The Sui Dynasty (581–617),” in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 3, Sui and T’ang China: 589–906, Part 1, ed. Denis C. Twitchett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 112.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Birrell, Anne M., trans. New Songs from a Jade Terrace: An Anthology of Early Chinese Love Poetry. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986.

Chang, Kang-i Sun. Six Dynasties Poetry. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Chennault, Cynthia. “Odes on Objects and Patronage During the Southern Qi.” In Studies in Early Medieval Chinese Literature and Cultural History: In Honor of Richard B. Mather and Donald Holzman, edited by Paul W. Kroll and David R. Knechtges, 331–398. Provo, Utah: T’ang Studies Society, 2003.

Graham, William T., Jr. The Lament for the South: Yu Hsin’s “Ai Chiang-nan fu.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Graham, William T., Jr., and James R. Hightower. “Yu Hsin’s ‘Songs of Sorrow.’” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 43, no. 1 (1983): 5–55.

Mather, Richard B. The Age of Eternal Brilliance: Three Lyric Poets of the Yung-ming Era (483–493). 2 vols. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Owen, Stephen. “Deadwood: The Barren Tree from Yu Hsin to Han Yu.” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 1, no. 2 (1979): 157–179.

———. The Making of Early Chinese Classical Poetry. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Asia Center Press, 2006.

Rouzer, Paul F. Articulated Ladies: Gender and the Male Community in Early Chinese Texts. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Asia Center Press, 2001.

Tian, Xiaofei. Beacon Fire and Shooting Star: The Literary Culture of the Liang (502–557). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Asia Center Press, 2007.

Wu Fusheng. The Poetics of Decadence: Chinese Poetry of the Southern Dynasties and Late Tang Poetics. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

CHINESE

Cao Daoheng 曹道衡 and Shen Yucheng 沈玉成. Nanbeichao wenxue shi 南北朝文學史 (A History of the Northern and Southern Dynasties). Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1991.

Liu Yuejin 劉躍進. Yutai xinyong yanjiu 玉臺新詠研究 (A Study of the “New Songs of the Jade Terrace”). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2000.

Lin Yi 林怡. Yu Xin yanjiu 庾信研究 (A Study of Yu Xin). Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 2000.

Zhang Bowei 張伯偉. Chan yu shixue 禪與詩學 (Zen and Poetics). Taipei: Yangzhi wenhua, 1995.