10

10

The two jueju quatrain forms, the pentasyllabic jueju (wujue) and the heptasyllabic jueju (qijue), are the shortest and most focused forms generally used by the Tang poets. Like the two “regulated verse” (lüshi) forms, which are exactly twice as long, both wujue and qijue are in the tonally regulated “recent-style poetry” (jinti shi) category. Brevity is both constraining and potentially liberating. It forces writers to pare every topic down to a few essential images, and then to harmoniously arrange them subordinate to a single controlling theme: “Jueju contain only four lines and not much space, so every line and every character must have meaning and flavor. Poems cannot bear even the least brushstroke of floating mist [words and phrases not to the point] or wasted ink.”1 Brevity also encouraged the projection of meaning beyond the literal text by the reliance on symbolic poetic language and the development of artful structural techniques. Gao Buying (1875–1940) explained: “The number of characters in jueju is not large, so if the meaning becomes exhausted then the spirit will be withered; if the language is obvious then the flavor will be short-lived. Only continual suggestiveness can make people lower their heads and imagine endlessly. This is the Greater Vehicle.”2 Many traditional critics thus considered the two jueju forms to be the most difficult. Tang poets reveled in the challenge “to see big within small” (xiaozhong jianda) and so used jueju for the weightiest of topics: presentations of philosophical or religious states, expressions of fundamental emotions, reflections on history, descriptions of vast landscapes, and so on. As with other Tang poetry, the general tendency was to merge themes of the natural world with those of personal states of mind—often described as a “fusion of feeling and scene” (qing jing jiao rong). Yet, when successful, jueju could reach a level of intensity unparalleled by poems in longer forms. One might say that the best jueju are short bursts of flame, as compared with the slow smolder of longer poems.

The term jueju literally means “cut-off lines,” and it was believed by many critics that this meant the wujue and qijue forms had originated as quatrain segments cut from the eight-line lüshi forms. Adherents of this reductive view posited that the truncation of lüshi yielded four structural possibilities for jueju:

1. Where neither couplet is parallel, the structure constitutes the two outer couplets of lüshi.

2. Where both couplets are parallel, it constitutes the two middle couplets of lüshi.

3. Where the first couplet is nonparallel and the second parallel, it constitutes the first half of lüshi.

4. Where the first couplet is parallel and the second nonparallel, it constitutes the second half of lüshi.

A major implication is that jueju aesthetics also derived from those of lüshi. However, it is now generally accepted that the term jueju dates to earlier than the advent of lüshi and was related to the Six Dynasties practice of multiple authors’ composing pentasyllabic “linked verse” (lianju). When an individual quatrain segment was taken out of context of a lianju, or if it never had other quatrains linked to it, then it was called cut-off lines (jueju) or broken lines (duanju). Moreover, the fixed-length quatrain form long predated the fixed-length octet. Although the truncated lüshi theory is ahistorical, there is no doubt it influenced the interpretation and composition of jueju during the Song and later dynasties. Yet, for reading Tang poetry, we can start from the premise that jueju development and aesthetics are independent of the lüshi forms.3

I begin this chapter with close readings of representative poems, to provide readers a sense of the thematic scope and aesthetic potential of jueju. A detailed examination of common jueju features then follows.

WUJUE

Although Tang poets all used wujue to record concentrated poetic experience, and pursued the same fundamental aesthetic goals for the form, differing styles of poems can be discerned. Here I present two basic styles of Tang wujue, differentiated primarily by the choice of themes and the type of language employed. The first can be called a “colloquial style” and the second a “descriptive style,” although both terms require qualification. For a context in which to approach these styles, a brief look back at pentasyllabic quatrain composition in the Six Dynasties period (222–618) is helpful.

Six Dynasties yuefu songs were a major source for wujue. These anonymous songs fall into three subcategories: “Wu songs of the Jiangnan region” (Jiangnan Wu sheng), from the southern capital area (present-day Nanjing); “western songs of Jing and Chu” (Jing Chu xisheng), from the area around the confluence of the Yangtze and Han rivers (present-day Wuhan); and “songs accompanied by drum, horn, and transverse flute” (gu jiao hengchui qu), from the north. These quatrains, predominantly love songs in a first-person female voice, were cited as a source for Tang wujue by literary historians as early as Gao Bing (1350–1423) and Hu Yinglin (1551–1602). Thematically, the songs are limited mainly to broken love affairs—and the occasional happy reunion. Description of the settings and characters is also quite limited. The language is colloquial, direct, and highly emotionally charged. Analysis of linguistic elements suggests the oral performance milieu: the extant texts are characterized by strong and continuous syntax, a use of first- and second-person pronouns, and often puns. Most tellingly, a continual use of the linguistic categories of deixis and modality gives the impression of direct speech. Deixis includes words and expressions that are ambiguous without specific knowledge of the context of the speech act (for example, “Hey you! Bring that over here!”).4 Modality refers to subjectivity of expressions, as inferences, conditionals, imperatives, questions, and so on; it is the grammaticalization of speakers’ subjective attitudes and opinions.5

Colloquial elements in the songs also created a tone and pace starkly different from those in contemporary shi, which strongly influenced the course of wujue (and qijue) development. In languages that use alphabets, the distinction between written and spoken forms at any one time is not that great; the written generally follows the vernacular and remains a language of action and direct communication. However, Chinese characters do not spell out spoken words, but are symbols for words; this fact allowed the classical written and the vernacular forms semi-independent evolutions. Classical Chinese did not develop in the direction of easy communicability or even clear referentiality, but toward dense, concise, and erudite presentation. It tended toward monosyllabism and was undergrammaticalized and ambiguous relative to the spoken language. Thus the injection of vernacular elements into jueju had the effect of considerably lightening the tone and speeding the pace relative to denser forms like lüshi.

Another product of Six Dynasties yuefu music was the fixed-length pentasyllabic quatrain form itself: it appears that popular southern musical tunes and phrasing dictated the length. A singer standing in front of an audience creates a context full of dramatic potential. The language and phrasing used are designed for maximum emotional impact. The fixed-length quatrain form of Six Dynasties music required the singer to say more by saying less and so was the catalyst for the gradual invention of standard compositional formulas that relied on implicit suggestion. Fixed length had not heretofore been a feature of Chinese poetry. It can reasonably be argued that experimentation with quatrains in the Six Dynasties led to interest in the fixed-length octet and eventually the development of the lüshi forms.

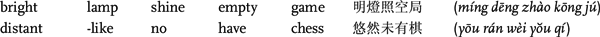

One Six Dynasties technique to overcome short fixed length was to employ clever homonym puns in the final couplet of quatrains, which, depending on which side of the pun one considered, cast the lines in wholly different ways. Consider the following couplet from a “Ziye ge” (Ziye Song):

The lines can be rendered, “The bright lamp shines on the empty chessboard /—For a long time there won’t be any game.” Yet when puns in the last line are factored in, it also reads, “The oil burns on but no date [for our reunion] has been set.”6 Other Six Dynasties songs omit puns, but the goal of projecting meaning and emotional resonance beyond the literal words remains intrinsic.

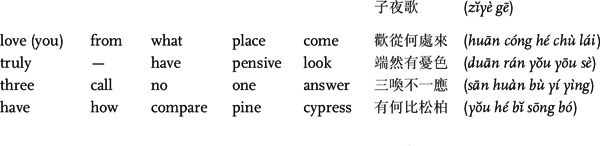

A representative example of Six Dynasties yuefu songs is another “Ziye Song”:

Whence have you come my love

That you wear such a melancholy look?

Three times I call, but not a single response—

Why can’t men be constant as pine and cypress?

[XQHWJNBCS 2:1042]

In the space of a four-line speech act, the mood of the singer changes completely, from concerned solicitude for her lover to resignation or even anger at his (apparent) betrayal.

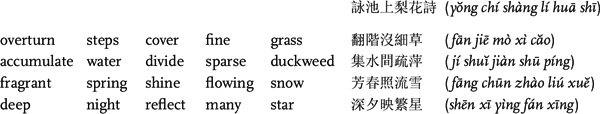

Six Dynasties literati shi poets also adopted the pentasyllabic quatrain form and explored its potential. Yet, stylistically, their written quatrain-length shi are almost the opposite of the yuefu quatrain songs. Like longer contemporary shi poetry, these quatrains are in a descriptive mode, aiming toward what the critic Zhong Rong (fl. 502–509) called “artful structure and descriptive similitude” (qiaogou xingsi).7 Such poems create a vibrant verbal texture (often through parallelism) but maintain a somewhat neutral or distanced emotional stance. This effect is in part due to the fact that the writers tended to avoid the use of grammatical function words, which were considered “empty words” (xuzi), in favor of “content words” (shizi)—nouns, verbs, adjectives, and so on. The goal was to encompass objective reality through written patterning. Declarative statements dominate, and images are chosen primarily to appeal to the visual sense—in aggregate, to paint mental pictures with words. Yet, what such language may lack in personal tone, it more than makes up for in philosophical/cosmological resonance, for it developed in the context of nature poetry by poets such as Xie Lingyun (385–433 [chap. 6]). The poem “In Praise of Pear Blossoms on the Pond,” by Wang Rong (468–494), typifies the literary quatrain style:

In Praise of Pear Blossoms on the Pond

On ruined steps they cover the fine grass

In pooled water they scatter among the duckweed

Fragrant spring shines on flowing snow

Deep night reflects myriad stars

[XQHWJNBCS 2:1403]

The transformation of the pear blossom petals floating in the wind to snow and stars is both striking and beautiful. The lines in each couplet are strictly parallel, but the language evokes an element of dynamism due to the use of strong verbs in the third position in every line—such key words were termed juyan (verse eyes) by later critics.

The same literati poets who wrote shi quatrains were also a major audience for the yuefu songs. Cross-fertilization was both natural and inevitable. Yuefu quatrain songs by named authors incorporate descriptive language (including parallelism) more than do most of the anonymous songs. And as time went on, shi quatrains increasingly exhibited elements derived from the subjective voice of the yuefu singer. In particular, Yu Xin (513–581) did much to transform the literati pentasyllabic quatrain into a medium for personal statement; his works can be considered precursors of many Tang wujue.8

Both of the two proposed styles of Tang wujue build on Six Dynasties antecedents, but in different ways. Colloquial-style quatrains hark back directly to the Six Dynasties songs by presenting archetypal yuefu characters in dramatic situations using a first-person colloquial voice to express fundamental emotions. Often such Tang quatrains are “ancient jueju” (gujue), a term applied by commentators such as Wang Li to the minority of jueju that do not follow the rules of tonal prosody or use oblique-tone rhymes.9 The reason for bypassing the tonal patterns appears to have been a conscious attempt by poets to evoke an archaic flavor in their verse. Yet the colloquial style is reflected in many proper wujue poems as well—it is theme and voice that dictate their inclusion. Two colloquial-style quatrains are presented, given pride of place at the outset. It should be noted, however, that it is unlikely that these poems were actually sung in the Tang. The musical tradition of Six Dynasties pentasyllabic quatrains—and that of the old Han yuefu as well—had all but died out by the Early Tang dynasty. Poets were making use of the ready-made resonance of old yuefu as source material for new kinds of poetry.

The descriptive style in fact is more prevalent in Tang wujue composition. It can be explained as a hybrid that merges the descriptive and visual power of shi with the emotional voice of the yuefu singer. One compositional method dominates: the first couplet is devoted to a description of images and often demonstrates parallelism; the second couplet is a continuous syntactic proposition and frequently exhibits deixis and modality. The first couplet is generally in the declarative mode and provides the setting or necessary background information for the second couplet. In the second couplet, the emphasis is on the subjective evaluation of all of the poem’s imagery. The voice of the singer is internalized by the poet and becomes less stridently expressive and more subtly reflective. Strong emotion remains, but it is generally presented through indirection and understatement.

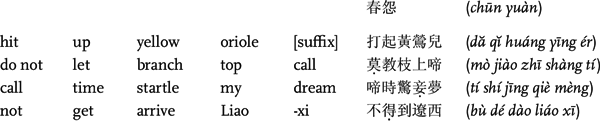

A premier example of the colloquial-style wujue is “Spring Lament,” by Jin Changxu (fl. 713–742). No other poem by Jin Changxu is extant, and he is a virtual unknown. Yet this poem struck a chord with readers and was held up by some as the model for jueju composition.

Hit the yellow oriole

Don’t let it sing on the branches

When it sings, it breaks into my dreams

And keeps me from Liaoxi!

[QTS 22:768.8724; QSTRJJ, 219–221]

[Tonal pattern Ia (imperfect), see p. 171]

The Qing dynasty critic Shen Deqian said of this poem, “It proceeds continuously in a single breath.”10 Strong, forward-moving syntax is evident in every line, and each couplet is a complete sentence. The point where one couplet ends and the next begins potentially could mark a break in continuity and thus retard the flow of a poem; this poem adopts the common solution of repeating the character in the last position of one couplet in the first position of the next. Further, the eight verbs (out of twenty characters!) give the language dynamism and power. The first-person pronoun qiè (a humble form used by women) and the modal constructions in line 1 (dăqĭ [hit], an imperative), line 2 (mò jiào [don’t let], a negative imperative), and line 4 (bù dé [cannot get], a judgment concerning ability) emphasize the voice of the speaker/singer and tie the poem to the earlier tradition of performed yuefu poetry. The impression is of a voice from the heart.

Thematically, the poem is firmly in the yuefu tradition. An archetypal lonely woman despairs over the fate of her absent husband or lover, who is gone to be a soldier on the border. Liaoxi refers to the region to the west of the Liao River, in present-day Inner Mongolia. Only in dreams are they together—until she is rudely awakened by the oriole. The poem seems just that simple, but the image of the oriole in fact carries subtle associations. On one level, the springtime bird is certainly calling its mate to the nest; this symbol of togetherness is in ironic contrast to the woman’s lonely state. Yet on another, more disturbing level, the image may allude to poem no. 131 in the Shijing (The Book of Poetry), in which the song of the oriole is a harbinger of the death of warriors for their lord. Thus the bird not only keeps the lonely woman from dreams of happiness but also represents her worst fears.

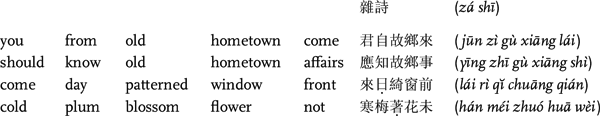

Wang Wei (701–761) is universally recognized as a master of wujue, particularly for his limpid landscape descriptions, which often contain Buddhist allegories. Yet the few colloquial-style quatrains he composed are also justly famous. He writes of lovers’ separation, this time from the man’s point of view, in the second of three “Miscellaneous Poems”:

You’ve come from our hometown

And must know what’s happening there

The day you left, by the patterned window

Was the cold plum tree in bloom?

[QTS 4:128.1304; QSTRJJ, 107–108]

By addressing the poem to the second-person pronoun jun, a dramatic situation with two actors is created, with the poet taking the speaking role. An impression of direct and natural speech is given by the strong syntax used throughout and the use of grammatical function words—the preposition zi (from) and the negative question word wei. The repetition of guxiang (hometown) in lines 1 and 2 and lai (to come) in lines 1 and 3 imparts a sense of informality to the speaker’s words and emphasizes the linguistic continuity. The words jun, guxiang, and lairi (come day; that is, the day of departure) are examples of deixis (person deixis, place deixis, and time deixis, respectively), as their exact referents require knowledge of the speech context. The inference in line 2 and the question in line 4 are modal statements that imply a speaker as point of reference.

The subtle emotion of the second couplet is what makes this poem memorable. In line 3, the word qichuang (patterned window; that is, a window with delicately carved or latticed decoration that makes it resemble qi [patterned silk]) almost certainly refers to a woman’s boudoir. We assume that the occupant is the speaker’s wife or lover, from whom he is separated. The question in line 4 is thus projected onto the personal level. The “cold plum” becomes a symbol of the couple’s love, which has endured separation the way plum trees endure the cold of winter. The rest of the question reveals the speaker’s anxiety about the continuing strength of this love: his asking whether the flowers bloom is an indirect way of asking whether his wife’s or lover’s feelings are as strong as before.

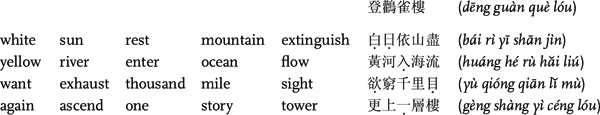

A representative example of quatrains in the descriptive style is Wang Zhihuan’s (688–742) famous “Climbing Crane Tower”:

White sun rests on mountains—and is gone

Yellow River enters sea—and flows on

If you want to see a further thousand miles:

Climb another story in the tower

[QTS 8:253.2849; QSTRJJ, 54–56]

[Tonal pattern I, see p. 170]

Crane Tower commanded a vista from a bend in the Yellow River, at a site in present-day Yongji, Shanxi Province. On one level, this is a simple landscape poem, in praise of the view. Yet when we analyze the relationships between the images in the parallel first couplet in the light of the modal conditional proposition in the second couplet, our thoughts may shift to the metaphysical realm.11 The permanence of mountains is paired with the transience of water, the light of day with the dark of night, and the termination of movement (resting, disappearing) with continuing movement (entering, flowing). A cosmological cycle of yin and yang is described. Indeed, we might go further: we are exactly at the midpoint in the cycle when yang yields to yin—the point of balance. The first couplet thereby creates a seemingly complete conception of the world, but then the second couplet asserts that there is an even greater view open to those who climb higher in the tower. Implicit is that there is a truth about the cosmos that is beyond our normal understanding. There is a Tang dynasty basis for this interpretation: Guifeng Zongmi (780–841), both a patriarch of Huayan Buddhism and a major Chan (Zen) master, uses the analogy of climbing a nine-story tower to describe the relationship between cultivation and enlightenment.12

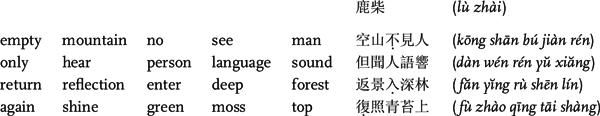

Wang Wei shared with Tao Qian (Tao Yuanming, 365?–427) a love of nature and a frequent tendency to use natural description as a springboard to philosophical and religious investigation. “Most mature nature poetry … would seem to look upon the configurations of landscape as symbols charged with a mysterious power.”13 While Tao Qian was a follower of the Daoist philosophers, Wang Wei was a devout Buddhist—he studied with the Chan master Daoguang for ten years and even converted part of his country estate into a monastery. His landscape poems are characterized by an integrated minimalism: in them, nature is distilled to a few essential images, which are harmoniously arranged in a balanced and stable whole that yet pulses with the energy of their interrelationships. Nature is the main actor; the poet becomes a distanced observer, or even seems to be absent. An overall impression of direct and unmediated reality is imparted, although in fact the landscapes are idealizations created by Wang Wei’s poetic imagination. He carefully chooses his images to appeal to the senses, primarily the eye; this has given rise to an oft-repeated maxim about Wang Wei: “In his poems, there are paintings” (shizhong you hua). Following are two fine examples of his landscape wujue; the first, “The Deer Fence,” is from his famous “Wang River Collection,” which describes sites at his estate at Lantian, south of the Tang capital of Chang’an (present-day Xi’an, Shaanxi Province):

On the empty mountain, no one is seen

But the sound of voices is heard

Returning: light enters the deep forest

Again: it shines on the green moss

[QTS 4:128.1300; QSTRJJ, 112–113]

This deceptively simple poem is in fact more difficult than it looks—one book discusses how nineteen different translators have rendered it in nineteen different ways! 14

What is an “empty mountain”? Clearly it is not barren, as we are informed that there is a “deep forest” there. Kong (empty) is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit Buddhist term śūnyatā. Primarily the word is a negation, a denial that phenomena have self-existence—that is, permanence independent of causes and conditions. Yet emptiness does not imply nihilism, for it is also “empty.” Rather, it is a practical term that has meaning only in the context of salvation; in Edward Conze’s description, through the exercise of wisdom (prajñā), the practitioner negates the world and thereby gains emancipation from it.15 Paul Williams has explained: “To see entities as empty is to see them as mental constructs, not existing from their own side and therefore in that respect like illusions and hallucinatory objects.…Emptiness is the ultimate truth (paramārthasatya) in this tradition in the sense that it is what is ultimately true about the object being analyzed, whatever that object may be.”16 Meditation on emptiness leads to the realization of the only permanence or self-existence, which is variously called the dharma body or law body of the Buddha (dharmakāya), the Buddha realm (dharmadhātu), or enlightenment, nirvāṇa. Thus Wang Wei’s “empty mountain” is the mountain as it really is from the perspective of an enlightened person. The first couplet as a whole affirms that this truth is not distant from our human world—it is indeed right here among us. The schools of Chinese Buddhism followed the traditional Indian Mādhyamaka (Middle Way) understanding that the true nature of phenomena is nondual: all things lie somewhere between the extremes of being and nonbeing. This is as true for the unconditioned law body as it is for things in this conditioned world—thus there is no possible separation between nirvāṇa (the other shore, or enlightenment) and saṃsāra (this shore, or the world of suffering, the round of rebirth). Looked at from another perspective, both nirvāṇa and saṃsāra are empty; thus both are the same. The implication is that all things are related and all are interpenetrated by the law body. Enlightenment is not transcending one reality to reach another, but is the discovery of the law body within this reality.

The second couplet—as always in jueju—is dominant. Why is the light returning and shining again on the green moss? Consider that in a dense forest on a mountainside, logically the only times during the day when moss on the forest floor might be illuminated are sunrise and/or sunset, when light can shine in underneath the tree canopy. The description Wang Wei presents suggests that this is part of his meaning: fanying (returning light) 17 recalls the phrase huiguang fanzhao (returning light shining back), which refers to the glow of colored light in the sky right at sunset. There is something suggestive about the scene: the light seems to purposefully illuminate the moss, over and over again. Both the light and the moss become important symbols—but for what?

An enlightenment metaphor is at work here. The interpenetration of nirvāṇa and saṃsāra suggests that the law body is innate within us. Indian writers termed this aspect tathāgatagarbha (Buddha essence, Buddha nature) and held that it is a common possession of all sentient beings. This Buddha nature is, on the one hand, what makes us yearn for nirvāṇa in the first place and, on the other, what makes it possible for us to reach it. Enlightenment does not produce anything; instead, it is a paring away of illusions (caused by ignorance) to reveal the Buddha already within us.18 Chinese Buddhists referred to this realization in many ways, one of which was the borrowed term huiguang fanzhao—here, the returning light shining back illuminates one’s original nature.

That explains the light, but what of the moss? One feature of early Chinese Buddhism was an expansion of the scope of tathāgatagarbha: it came to be viewed as the common endowment of not only sentient beings, but also nonsentient things.19 The idea is implicit in several sutras, but it became a major focus in China, particularly through the influential teachings of the Huayan school. Conze has summarized basic Huayan thought as follows:

Each particle of dust contains in itself all the Buddha-fields and the whole extent of the Dharma-element; every single thought refers to all that was, is and will be; and the eternal mysterious Dharma can be beheld everywhere, because it is equally reflected in all parts of this universe. Each particle of dust is also capable of generating all possible kinds of virtue, and therefore one single object may lead to the unfolding of all the secrets of the entire universe.20

Although moss is perhaps the most insignificant thing in the forest, Wang Wei presents it as a symbol of absolute truth.

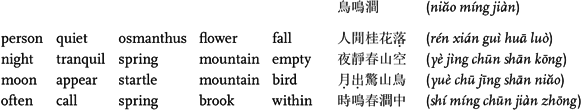

With the previous poem in mind, even a glance at the following wujue, “Calling-Bird Brook,” suggests its Buddhist overtones:

Man quiet: sweet osmanthus falls

Night tranquil: the spring mountain empties

The rising moon startles mountain birds

Which call awhile in the spring stream

[QTS 4:128.1302; QSTRJJ, 119–120]

[Tonal pattern II (imperfect), see p. 170]

Both the emptiness of the mountain in spring and moonlight so powerful that it startles birds in the spring stream can be readily interpreted as Buddhist metaphors. Let us look closely at only the first couplet, as it introduces an aspect of Buddhist thought and practice not yet mentioned. The couplet is strictly parallel and made up of only content words (shizi). Thus the relationships between the images are suggested through juxtaposition and not grammatically marked. Although we could read each of the two lines as simply additive, I prefer to read each as a cause-effect proposition (because the man is quiet, therefore the sweet osmanthus falls; because the night is tranquil, therefore the spring mountain is empty). Such an interpretation is in keeping with ideas about meditation practice contemporary to Wang Wei. The major influence on Early and Middle Tang Buddhism in this regard came from the Tiantai school, whose founder, Zhiyi (538–597), had reformulated and systematized earlier Hinayana meditation techniques and set them firmly in a Mahayana context. Practice revolved around the dynamic relationship between zhi (śamatha [cessation, calming]) and guan (vipaśyanā [insight, contemplation]). The two always go together. In Zhiyi’s words, “śamatha (or zhi) is the hand that holds the clump of grass, vipaśyanā (or guan) the sickle that cuts it down.”21 In Wang Wei’s poem, “man quiet” and “night tranquil” are zhi, and “osmanthus falls” and “spring mountain empties” are guan. Cessation of mental activity allows the poet to experience true reality. When the realization of emptiness is attained, out comes the bright moon of enlightenment.

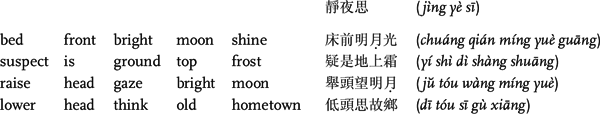

Li Bai (701–762)—brilliant, insouciant, frequently inebriated, and mostly unemployed—was a master of both the wujue and qijue forms. His “Quiet Night Thoughts” exemplifies perfect control of structure to create a suggestive closure:

Before my bed, the bright moonlight

I mistake it for frost on the ground

Raising my head, I stare at the bright moon;

Lowering my head, I think of home

[QSTRJJ, 146–147; QTS 5:165.1709]

The first couplet presents an arresting image: the poet is awakened by brightness streaming in the window, and he misinterprets its origin. The moon up above seems to him to be the reflection of frost down below. The second couplet ties the images of moon and frost to the poet’s homesickness and thereby makes them significant. Repeating mingyue (bright moon), line 3 directly refers to line 1. As line 3 directly refers to line 1, we expect line 4 to refer to line 2. That is, line 4 will in some manner concern frost on the ground. Frost is not mentioned directly, but with the poet’s lowering his head, it is implied. This is because the first couplet has presented a two-part visual scene in which the moon is above and the frost is below. The second couplet repeats the first half of this pattern in line 3—the poet looks up to see the moon. In line 4, the poet looks down, and so we assume the rest of the pattern. The round (full) moon, which in Chinese poetry often carries connotations of unity and family togetherness, has caused the traveler to lower his head and think of home. Yet his thoughts are permeated by the frost, now transformed into a symbol of his homesickness and still carrying its connotations of coldness, harshness, and destructiveness. Thus the poem has very subtly projected us into the poet’s raw emotional state. The first couplet provides the images and structural pattern that are the backbone of the second couplet. However, the second couplet is dominant, as it reinterprets what has come before.

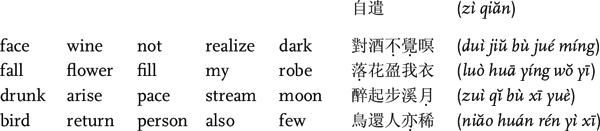

By far, Li Bai’s favorite topic was Li Bai. More than any other Tang poet, he created a recognizable poetic persona, a free-spirited, spontaneous, larger-than-life bohemian. This persona is reflected in “Amusing Myself”:

Facing wine—I don’t notice the dusk

Falling flowers cover my robe

Drunkenly I rise, and walk with the moon in the stream

Birds have gone back, and people are few

[QTS 6:182.1858; QSTRJJ, 155–156]

Li Bai presents himself as a figure of fun—the drunken poet covered in flowers and following the moon’s reflection in the stream. The vignette is utterly charming. Yet poems like this should make us ask ourselves: Is the Li Bai who appears in his poems the real Li Bai or a fictional construct? This is an important issue in the Chinese context, as the root of the poetic impulse is said to be shi yan zhi (poetry expresses intent), which would suggest that poems are always spontaneous, true reflections of the writer’s inner being.

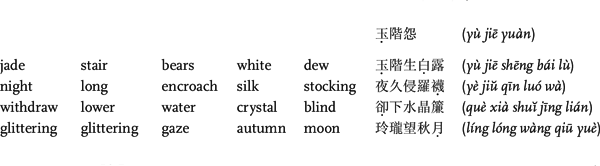

Let us read one more wujue poem by Li Bai. The lonely woman figure in yuefu was not limited to the common folk. The abandoned palace lady offered a host of new possibilities, particularly for rich description. The prototypical lady of this type was Ban Jieyu, once the favored consort of Emperor Cheng (r. 32–6 B.C.E.) of the Western Han dynasty. She was displaced when the emperor became infatuated with the lovely Zhao Feiyan and her sister. Fearing jealous recriminations, she retired to serve the dowager empress in Changxin Hall, a separate building within the Changle Palace complex. A poem attributed to Ban Jieyu describes her love as like a round silk fan, pure and white as snow, which is put away in a box when the chill of autumn comes.22 The story and poem became the basis for a host of yuefu compositions by later writers, under titles such as “Jieyu’s Lament” and “Changxin Lament.” I discuss a series of poems about Ban Jieyu in the following qijue section of this chapter. Li Bai’s “Lament of the Jade Stairs” is a contribution to the tradition. Although the theme of this poem derives from the ancient yuefu tradition, the language places it squarely in the descriptive style of wujue:

On jade stairs, the rising white dew

Through the long night pierces silken hose

Retreating inside, she lowers crystal shades

And stares at the glimmering autumn moon

[QTS 5:164.1701; QSTRJJ, 143–145]

Li Bai’s poem is in part a tribute to the Six Dynasties poet Xie Tiao (464–499), whom he much admired. Xie Tiao had also composed a poem on the theme, “Jade Stairs Resentment” (C7.2). Although lovely, Xie Tiao’s work is much simpler than Li Bai’s. Li Bai borrows several elements—the lady’s sleepless night, the jeweled blinds, the glittering light, silk clothing—and creates a masterwork through the subtle interplay of the images.

Li Bai’s lines describe the palace lady in terms of both her languor and her obsession with the past. Despite her opulent surroundings and dress, she feels only sorrow as, under the light of the moon, she stares over the palace walls to where the emperor dwells. The poem presents the constancy of her love, by means of her long, sleepless watch from the courtyard and the boudoir; the fickleness of the emperor is only suggested by contrast. The full moon is the key, not only because it is generally a symbol for family reunion but also more specifically because in the shi poem attributed to her, Ban Jieyu had written:

Newly cut, fine white silk

Fresh and pure as frost and snow

I sew it into a “togetherness fan”

Round, round like the bright moon.

She had given it to the emperor, who cast it aside when the warmth of their relationship was replaced by the cool of autumn. Thus the “autumn moon” in Li Bai’s poem is an ironic symbol of her abandonment. The glittering of the “crystal shades,” which scatter the moonlight into a thousand stars, recalls the drops of dew on “jade stairs” in line 1—or is it that both the crystal and the dewdrops suggest that she stares through the window with eyes filled with tears?

QIJUE

Although a small number of Six Dynasties heptasyllabic quatrains are extant, and Early Tang poets experimented with the form, stylistically mature qijue poetry was an invention of the High Tang poets, most notably Wang Changling (698–ca. 755) and Li Bai. Qijue developed along with Tang popular music, for which it was the major song form. Thus initially the thematic scope was narrow: qijue lyrics were generally limited to popular yuefu themes (which, for the Tang, can be roughly divided into frontier songs about homesick soldiers and boudoir songs about abandoned ladies) and those describing parting from friends and loved ones. Only gradually did the scope of qijue themes expand, until by the Middle and Late Tang, the form had become a flexible tool for personal expression.

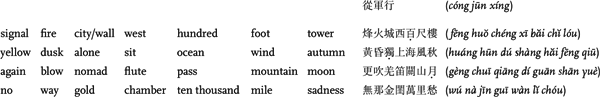

Let us look at one of Wang Changling’s frontier poems, from a set called “Following the Army”:

Signal fires west of the wall, hundred-foot watchtowers

Climbing alone at dusk—an autumn of desert wind

What’s more—“Mountain Pass Moon” plays on a nomad flute

No way to reach the golden chamber, past ten thousand miles of sadness

[QTS 4:143.1443–1444; QSTRJJ, 77–80]

[Tonal pattern IIa, see p. 171]

Typically, the poem presents no actual warfare; qijue poets were more interested in the emotions of the soldiers when in moments of rest between battles. A secondary interest was the great desert itself, which had a strangely romantic attraction for the city dwellers of Chang’an. Wang Changling liberally spices his qijue with Central Asian geographic names, nomadic accoutrements, and bleak vistas. In this poem, a soldier climbs a tower to look back toward his home in China; when he hears “Mountain Pass Moon” (a song associated with homesickness), he despairs of the distance to the “golden chamber” where his wife or lover waits. The huge landscape between them is suddenly suffused with their mutual pain.

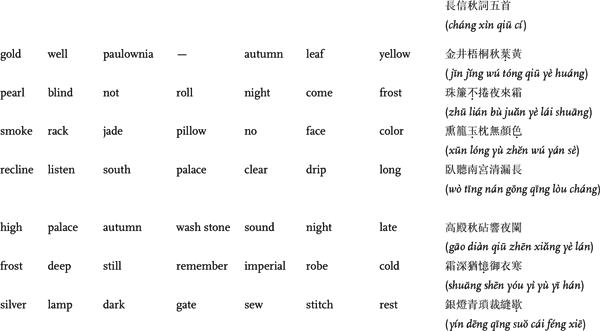

One of Wang Changling’s innovations was the qijue poem series, a useful means to overcome the brevity of the form. Each stanza is a complete qijue, but when all are read together, there is an exponential buildup of emotional resonance. Whereas the total length is similar to that of heptasyllabic ancient poetry (qigu), the effect of the presentation is quite different: the qijue series comprises multiple moments of great intensity. A fine example is Wang Changling’s five-poem series “Autumn Songs of the Hall of Abiding Faith,” which is his version of the Ban Jieyu theme:

Autumn Songs of the Hall of Abiding Faith

On the paulownia by the golden well, autumn leaves have yellowed

The pearl blinds are not rolled against the night-coming frost

By fragrant drying rack and jade pillow, her face is pale

She lies listening to the south palace clock—clear drops without end

An autumn wash stone by the high hall sounds far into the night

Deep frost still recalls the chill of an imperial robe

Beside silver lantern and painted door lock—she puts aside her sewing

And looks toward the golden city, and her Bright Lord

Clutching a broom at daybreak, she opens the golden hall

Then, clasping her round moon fan, she wanders for a while

Her jade face can’t compare with the brightness of cold crows

Which still carry reflections of the sun at Zhaoyang Palace

Obsessed with thoughts of a truly ill-fated life

In dreams seeing her lord, and upon waking, almost believing

Torches shine in the western palace, proof of night revels

In palace corridors this night, clearly someone has found favor

The autumn moon is bright within Changxin Hall

The slapping sound of washing clothes below Zhaoyang Palace

In a mansion of white dew—traces of thin grass

Under a canopy of red silk—limitless feelings

[QTS 4:143.1445]

[Tonal pattern IIa (poems 1–3), Ia (poem 4), combination of IIa and Ia (imperfect) (poem 5), see p. 171]

The series presents Lady Ban through the course of two nights and a day. The cumulative effect is to show the obsessive quality of her despair and the hellish nature of her existence. Her emotion is in strong contrast to her opulent surroundings, which, as a result, appear as a prison. Solitude and too much time on her hands allow her imagination to run wild; in the fourth poem, she does not actually know that the emperor is in the Zhaoyang Palace romancing Zhao Feiyan. The entire series takes place in her fevered mind. Note that the second couplet of the fifth poem uses static parallelism. There is no resolution, no conclusion, for Lady Ban. Moreover, only in this final poem is the tonal prosodic pattern slightly off (it does not follow the nian rule [chap. 8]), which gives a disquieting effect.

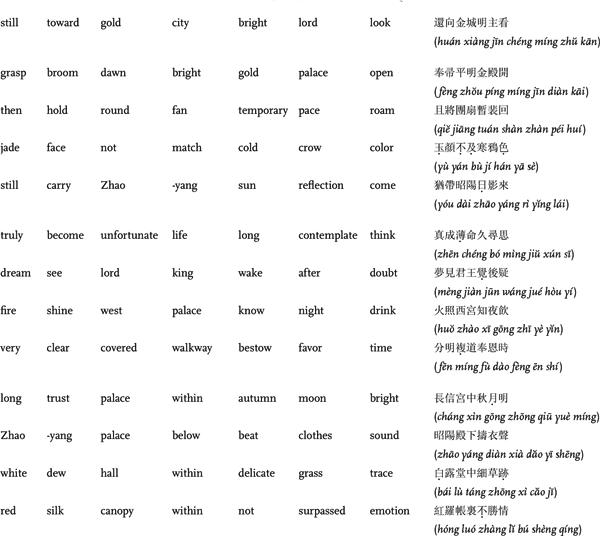

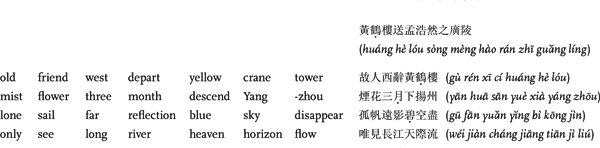

Poetry of parting is judged by its power to present personal affection in novel ways. A fine example is Li Bai’s “Sending Off Meng Haoran to Guangling at Yellow Crane Tower”:

Sending Off Meng Haoran to Guangling at Yellow Crane Tower

An old friend leaves the west at Yellow Crane Tower

And in flower mists of the third month descends to Yangzhou

The far shadow of a lone sail is lost in the azure sky

I see only the Yangtze River, flowing to the edge of heaven

[QTS 5:174.1785; QSTRJJ, 163–164]

[Tonal pattern IIa (imperfect), see p. 171]

In just a few words, Li Bai evokes the vastness of the Yangtze River. His focus on the river landscape belies his true purpose—expressing his grief at parting from a friend. In line 3, Meng Haoran’s boat slowly sails over the horizon, and in line 4, there is only the great river. By subtle implication, Li Bai reveals that he has been standing atop Yellow Crane Tower all the while, watching the scene and thinking of his friend.

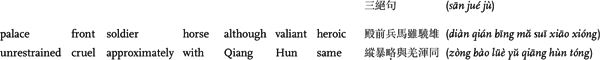

The great poet Du Fu (712–770) is not well known for his jueju quatrains; as the critic Gao Buying put it, “Du Fu’s talent encapsulated heaven and sustained the earth; he could not fully bring his strengths to bear in a little quatrain.”23 Yet, in his last years, Du Fu did turn his hand to quatrains, especially qijue, and Gao Buying pointed out that the forceful and direct works he produced constituted a new style. By challenging the countervailing aesthetic, it appears that Du Fu was deliberately trying to widen the scope of the jueju genre. The following is an example:

Palace guards should be heroic and brave—

Not wild and cruel, like Tangut and Tuyuhun!

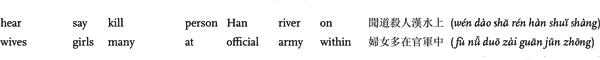

I hear they’re killing men up on the Han River;

Many girls and women are in the army camps

[QTS 7:229.2490; QSTRJJ, 252–253]

[Tonal pattern IIa (imperfect), see p. 171]

In about 759, an ailing Du Fu moved his family to Shu (Sichuan); he remained in the south for the rest of his life. In the spring of 765, Shu was thrown into chaos by the fighting of military factions. In the autumn of the same year, the Gansu Corridor in the northwest was repeatedly wracked by invasions of Tangut, Tuyuhun, Tibetan, and Uighur forces, some of whom reached as far as the area of the Chinese capital. Countless refugees fled south to safety. However, at the Han River, an army of the Imperial Guard set upon them, extorting money, raping, and killing. Du Fu wrote this poem to express his outrage. He is deliberately unpoetic here (if we consider frontier poetry like that by Wang Changling to be the norm for military topics); his point is to shock and shame his countrymen.

A greater influence on qijue development came from the regulated verse of Du Fu’s late period, particularly his qilü (chap. 9). To express the complexities of a lifetime of hard experience, Du Fu abandoned the unity of scene that characterizes most High Tang poetry and, through the use of dense symbolism and rich cultural allusions, created sudden shifts of point of view that obliterate barriers of time and space, and distinctions between self and world. Late Tang qijue often present a shortened version of Du Fu’s “shifting style”: the first couplet describes an experience in the present that serves as a catalyst for mental projection in the second couplet. Thus later qijue poets often juxtaposed different realms of existence: past glory with present ruin, consciousness of age with memory of youth, mundane reality with supramundane legend or imagination.

A fine example is “Red Cliff,” by Du Mu (803–852). Du Mu had a moderately successful bureaucratic career in the polarized political climate of the period, but the image presented in his qijue (and affirmed in popular anecdotes about him) is that of a playboy. Even a weighty historical subject like that of “Red Cliff” becomes, in Du Mu’s hands, a romantic daydream:

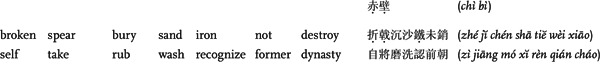

Buried in sand a broken spear, its iron not yet gone

I take up and burnish it, and recall an ancient age

If east wind had not aided young Master Zhou

Still: spring would bind the Qiao girls deep in Bronze Bird Tower

[QTS 16:523.5980; QSTRJJ, 676–678]

[Tonal pattern IIa, see p. 171]

The final years of the Han dynasty coincided with a great power struggle for dominance. Eventually only three great warlords were left: Cao Cao (155–220) of Wei to the north, Sun Quan of Wu to the southeast, and Liu Bei of Shu Han to the southwest. When Cao Cao invaded the south, Wu and Shu Han allied to fight him. The site of the climactic battle in 208 between the two forces was at Red Cliff, on the Yangtze River in modern Puqi, Hubei Province. Confident of victory, Cao Cao had chained his troopships together, bow to stern, and sailed east downriver to meet his foes. Making use of a fortunate change in the direction of the wind, the general of the allied forces, Zhou Yu, dispatched a wave of fireships and succeeded in annihilating the enemy fleet. Thus the fate of the empire depended on a turn of the wind. Du Mu’s focus is, however, not the battle but the two daughters of the Han official Qiao Xuan, who were acknowledged as great beauties of the empire. The elder had been the wife of Sun Ce, Sun Quan’s deceased elder brother, and the younger was the wife of Zhou Yu. One of the goals of Cao Cao’s invasion was, reputedly, to claim the Qiao sisters for himself; he planned to remove them to Bronze Bird Tower, his pleasure palace at a site in modern Linzhang, Hebei Province. Cao Cao had also ordered that, after his death, all his palace ladies and dancing girls were to reside there and maintain sacrifices to his memory. What a pity, Du Mu suggests, if Cao Cao had succeeded and the Qiao girls had been taken from the world!

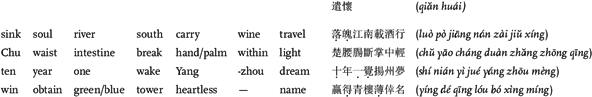

In “Dispelling Sorrow,” an older and wiser Du Mu looks back on his life of pleasure and does not like what he sees:

I sunk my soul in the river lands, wandered with wine,

Broke the hearts of Chu girls dancing lightly in my hands

Ten years on, I wake from a Yangzhou dream—

All I’ve won: a callous name in the green mansions

[QTS 16:524.5998; QSTRJJ, 684–685]

[Tonal pattern IIa, see p. 171]

“Dancing lightly in my hands” (zhangzhong qing) is a glancing allusion to the great Han beauty Zhao Feiyan, who, it was said, was so light that she could dance on the emperor’s palm. “Green mansions” is a euphemism for the dwellings of the courtesans.

Li Shangyin (813–858) deserves his reputation as one of China’s most obscure poets; some critics have explained certain poems as autobiographical works about clandestine love affairs with palace ladies and Daoist priestesses, while others see the same poems as simple expressions of personal sadness, or even as satirical political allegories.

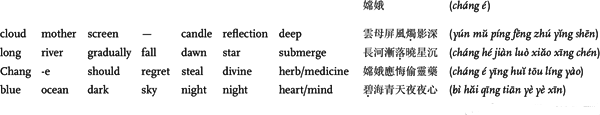

Behind the mica screen, candles cast deep shadows

The Great River slowly sinks, and dawn stars are drowned

Chang-e must regret stealing the elixir—

Over blue sea, in dark sky, thinking night after night

[QTS 16:540.6197; QSTRJJ, 755–757]

[Tonal pattern IIa, see p. 171]

Chang’e, the goddess of the moon, had been the wife of the legendary archer Yi. After he saved humankind by successfully shooting down nine of the ten suns that were burning up the earth, the Queen Mother of the West rewarded him with the elixir of immortality. Chang’e stole and consumed the elixir and became immortal. However, in doing so, she lost her corporeality and, to her surprise and horror, floated up to the moon, where she remains. Li Shangyin integrates the Chang’e legend into his own melancholy reflections. After sitting up through the night by candlelight, he watches the “Great River” (Milky Way) fade in the dawn light. His thoughts turn to Chang’e, up in the moon. Yet who or what is she to him? A former lover who is now unattainable? An unattainable ideal? Or does he see himself in Chang’e, a loner emotionally or spiritually cut off from others by circumstances? The first couplet may provide a hint: the candles reflected in the mica screen glitter like a thousand stars in his room, just as Chang’e is surrounded by stars in the sky.

PROSODY OF JUEJU

By now readers are familiar with the prosodic rules of regulated verse, so those of jueju should pose few difficulties. The prosody of jueju allows for some variation, but it is by and large standardized. Line length is fixed and regular, and, as in most other forms of shi poetry, lines are read with breaks or pauses in predictable places. As Zong-qi Cai writes in chapter 5, the pentasyllabic line is made up of a disyllable and a trisyllable separated by a caesura and presents semantic rhythm in either of two patterns: 2 + (1 + 2) or 2 + (2 + 1). The extra two characters in the heptasyllabic line are added to the beginning of the pentasyllabic structure, thus giving 4 + 3, or, more specifically, (2 + 2) + (1 + 2) or (2 + 2) + (2 + 1).

Every two lines are a couplet, which is not only a formal unit but also a semantic/thematic unit. A rhyming word always falls at the end of each couplet. The basic rhyming scheme of jueju is xAxA, which presents the first half as one discrete unit, followed by the second half comprising a unit of identical meter, with the resonating punctuation of the rhyme at the very end. This scheme is typical for wujue, although it is found occasionally in qijue as well. All but two—“Spring Lament” and “Quiet Night Thoughts”—of the pentasyllabic quatrains discussed earlier follow the pattern xAxA. The AAxA rhyming scheme is typical for qijue but rare for wujue. Every one of the qijue examples follows the pattern AAxA, although due to pronunciation change (especially the loss of entering tones), the rhymes are not always evident in modern Mandarin.

Tonal patterning provides a textured pattern of sound that both demarcates the individual couplets and unifies them in a balanced quatrain structure (chap. 8). In short, there are only four possible tonal patterns for regulated jueju: standard types I and II, and variant types Ia and IIa. As wujue seldom rhyme the first line, types I and II are dominant; since qijue usually rhyme the first line, types Ia and IIa are most common. Yet observance of tonal patterns is not quite as strict in jueju as in lüshi. “Violations” can be found in all positions (words) of a pentasyllabic or heptasyllabic line. Sometimes otherwise regulated poems break the nian rule, which ties couplets together. Tonal patterns of jueju examples that contain violations are marked in the preceding as “imperfect.” Presumably, prosody for jueju was more flexible due to the close connection that both wujue and qijue had with music.

Moreover, as mentioned, a subset of Tang jueju examples does not conform to normal tonal prosodic patterns and/or use oblique tone rhymes. Due no doubt to the influence of the Six Dynasties yuefu tradition, these gujue examples are overwhelmingly pentasyllabic. The qijue was primarily a Tang invention, so it follows that heptasyllabic gujue are rare. The earlier examples without an identification of a tonal pattern are gujue, composed during the Six Dynasties or the Tang. Notably, these gujue works still often contain an element of prosodic design, although it is idiosyncratic. Wang Wei’s “The Deer Fence,” for example, uses oblique tone rhymes and displays clear tonal alternation in each line—but not between lines in each couplet. Distinguishing between a regulated jueju with an imperfect tonal pattern and a gujue with level-tone rhyme that displays some tonal design can at times be a matter of opinion (see, for example, Li Bai’s “Amusing Myself”).

CLOSURE

Closure is considered by many what jueju do best. Various epithets used to describe jueju—“one note, three echoes” (yichang santan), “meaning beyond the words” (yan wai zhi yi), “flavor beyond flavor” (weiwai zhi wei), and “lines that end but meaning that does not end” (ju jue yi bujue)—all clearly refer to strong closure.

The closure functions akin to the way musical phrasing can create an emotional response. Let us first consider how semantic rhythm contributes to closure. While there are no strict rules for this aspect, frequently jueju poets present patterns of the final trisyllables in the four lines, which aid closure. For example, in “Quiet Night Thoughts,” both lines in the first couplet end (2 + 1), while both lines in the second couplet end (1 + 2). Closure is particularly evident in “Lament of the Jade Stairs” and “Red Cliff.” In both poems, the lines in the first couplet end (1 + 2). Line 3 changes to (2 + 1), while line 4 returns to (1 + 2) and the familiar pattern.

Jueju rhyming schemes, whether xAxA or AAxA, also help to create closure. In the former, rhyming characters are present at the end of each couplet, but the reader or listener experiences the rhyme only once—at the very end. The repetition of couplet structure and the rhyme integrate the two halves and complete a stable pattern, engendering a gratifying sense of closure. AAxA also leads to closure, but in a different way. The ringing of the rhyme in line 2 marks the first couplet as a seemingly finished unit. The poem in a sense starts again in line 3, and the reader or listener has a certain expectation that the second half will follow the pattern of the first. The omission of the rhyme in line 3 then presents a disquieting break in the sequence. However, the return to the familiar rhyme in line 4 confirms the original pattern and unites the two couplets.

It is also revealing to consider the tonal patterns in terms of closure of both couplets and entire quatrains. Since the patterning is determined by the opposition of tones two syllables at a time, and because the lines have an odd number of characters, maximum contrast within the single line will always be imperfect. Only when two lines with exactly opposite tonal patterns are combined does the prosody balance perfectly. The reader or listener perceives the completion of the couplet structure, confirming expectations created by the ongoing sequence.

The tonal alternation of two couplets again emphasizes closure. Remember that the various line combinations result in only two standard couplets. In xAxA rhymed quatrains, one of each is required, yielding either standard type I or standard type II. Consider the resulting structures from the perspective of the reader or listener. The first couplet presents a unified and complete prosodic structure of maximum tonal contrast. Yet, rather than repeating the pattern, line 3 begins a different pattern; only when line 4 is finished does it become apparent that the second couplet also presents a structure of maximum tonal contrast. The two couplets affirm an identical structural principle but do so in different ways. The revelation of this dual quality of sameness within difference and difference within sameness creates closure. Put another way, it is because the pattern of the second couplet differs and yet follows the same principle that closure is ensured: if both couplets used the same pattern, the prosody would be merely repetitive, and no ending point would be implied.

When the rhyming scheme is AAxA, the prosody indicates closure in a somewhat different way. In the variant patterns types Ia and IIa, the first couplet does not present perfect maximum contrast but only generally does so. The only perfectly balanced unit is the second couplet, so it dominates, prosodically speaking. Yet it does not provide closure all on its own but also reintegrates the first couplet: notice that the pattern of line 4 is identical with that of line 1—the poem has returned to its starting point.

Apart from prosody, the organization of contents is invariably designed to lead to a sense of closure as well. The first couplet tends to be a setup for conclusion in the second couplet, and it is at first glance not necessarily memorable. Unlike in lüshi, in jueju parallelism is not required, although it is an option. When found, it is more frequent in first couplets, where it efficiently presents multiple scene-setting images in a few words. However, parallelism is generally avoided in second couplets, because its static quality makes conclusions difficult. The second couplet is the focus of the poem: it is successful when it completely integrates all four lines. Closure of a theme in jueju does not imply predictability. The first couplet sets up a theme or topic, perhaps by suggesting a question, a dramatic situation, or an archetypal character. The reader has an expectation of where the poem is going, but the successful jueju will “turn” (zhuan) the pattern in the second couplet and bring about a gratifying closure in a way that is surprising, transformative, yet still a natural outgrowth of what has been said before.24

The subtle design of Li Bai’s “Quiet Night Thoughts” has already been mentioned. Another illustrative example is Jin Changxu’s “Spring Lament.” The first couplet sets a conundrum: Why does the speaker so desperately want to stop the singing of the birds? The second couplet sends us in an unexpected direction but, at the same time, explains the mystery. The power of genre also helps to create thematic closure. As jueju became established, knowledgeable readers became accustomed to looking for closure in the second couplet, even when doing so was difficult. The “green moss” in Wang Wei’s “The Deer Fence” is an “image in suspension” that is at first glance enigmatic, but, because of its position in the poem, the reader knows it must be important and so actively tries to unify it with the rest of the poem.

Finally, a word about the differences between the two forms. Frequently, critics have assumed that the qijue is merely a longer version of the wujue. However, there are significant structural differences between the two that led to clear divergences in their aesthetic potentials and the styles that poets developed.

The pentasyllabic line invariably follows a 2 + 3 meter, which is most often used to present a single subject + predicate or topic + comment structure (thematic table of contents 5.2 and 5.3). The two parts of the line are read together as related units. Alternatively, both lines in a couplet may constitute one continuous proposition. It is possible, but very uncommon, for one pentasyllabic line to present two separate topic + comment structures. This is because the two-character part of the line is too short to say very much. The three-character part, however, shows considerably more potential to complete a topic + comment, with its 1 + 2 or 2 + 1 pattern variability. Thus when we consider the pentasyllabic quatrain, generally we see a maximum of four topic + comment structures, but more usually three (as second couplets tend to be continuous propositions to create closure) or even two.

The heptasyllabic line, with its 4 + 3 meter, can and frequently does present two distinct topic + comment structures. (In fact, this is its birthright: the heptasyllabic line developed gradually out of the tetrasyllabic couplet during the Han and Six Dynasties periods.) 25 A heptasyllabic quatrain could thus theoretically comprise as many as eight topic + comment structures, although a number between four and six is the norm, as poets tended to employ a balance of imagistic language (that is, undergrammaticalized content words) and continuous propositions. Although the qijue form is only eight characters longer than the wujue, it contains far more space for development; moreover, since the overtones in a poem are often suggested through implicit comparisons between the parts, the more parts there are, the more potential there is for complexity.

The rhythm of the heptasyllabic line also differs from that of the pentasyllabic line, which has implications for how poets approached it. When pentasyllabic poetry is chanted, it rather naturally falls into eight beats per line: tum tum, tum tum tum (rest, rest, rest) / tum tum, tum tum tum (rest, rest, rest). The length of the silent rests gives the overall rhythm a slow and stately quality, which implicitly suggests that the content is weighty and important. When heptasyllabic poetry is chanted, it also naturally falls into eight beats per line: tum tum tum tum, tum tum tum (rest) / tum tum tum tum, tum tum tum (rest). The four-beat unit at the beginning of the line creates more momentum than does the two-beat unit at the beginning of the pentasyllabic line; moreover, the single beat of rest at the end of the heptasyllable gives the impression that each line rushes into the next. Thus heptasyllabic poetry has a distinctive flow, continuity, and lightness. The best poets of qijue carefully crafted the sound quality of the syllable combinations, employing alliterations, internal rhymes, and reduplication more frequently than in the pentasyllabic line. Hu Yinglin observed: “Pentasyllabic jueju emphasize the real and tangible; usually the substance exceeds literariness. Heptasyllabic jueju emphasize the lofty and beautiful; usually literariness exceeds substance.”26

The differences between wujue and qijue had a clear impact on poetic practice. After the Tang, wujue became increasingly rare; we can conclude that poets no longer saw creative potential in the form—the great Tang writers had exhausted it. Qijue, on the contrary, remained one of the most popular and expressive poetic forms throughout the classical period.

NOTES

1. Wang Kaisu (Qing dynasty), Saotan balüe (Eight Sketches of the Literary World), quoted in Qianshou Tangren jueju (One Thousand Jueju Poems by Tang Writers), ed. Fu Shousun and Liu Baishan (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1985), 1020.

2. Gao Buying, ed., Tang Song shi juyao (The Essential Shi Poems of the Tang and Song) (Hong Kong: Zhonghua, 1985), 750.

3. Charles Egan, “A Critical Study of the Origins of Chüeh-chü Poetry,” Asia Major, 3rd ser., 6, pt. 1 (1993): 83–125.

4. Stephen C. Levinson, Pragmatics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

5. F. R. Palmer, Mood and Modality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

6. Shuen-fu Lin, “The Nature of the Quatrain from the Late Han to the High T’ang,” in The Vitality of the Lyric Voice: Shih Poetry from the Late Han to the T’ang, ed. Shuen-fu Lin and Stephen Owen (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986), 306–308. Lin proposes three major jueju characteristics derived from Six Dynasties songs: simple diction, dynamic syntactic continuity, and sententiousness (296–331).

7. The term is from Zhong Rong, Shi pin (An Evaluation of Poetry). See Kang-i Sun Chang, “Description of Landscape in Early Six Dynasties Poetry,” in Lin and Owen, Vitality of the Lyric Voice, 105–129.

8. Daniel Hsieh, The Evolution of Jueju Verse (New York: Lang, 1996), 206–216.

9. Wang Li, Hanyu shilü xue (Studies in Chinese Verse Regulation) (Shanghai: Jiaoyu, 1963), especially 33–41.

10. Shen Deqian, Tangshi biecaiji (A New Selection of Tang Poetry), quoted in Fu and Liu, Qianshou Tangren jueju, 220.

11. The second couplet is technically parallel as well, but the conditional proposition gives it continuous syntax; this type of parallelism is called liushui dui (running-water parallelism).

12. Peter N. Gregory, “Sudden Enlightenment Followed by Gradual Cultivation: Tsung-mi’s Analysis of Mind,” in Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought, ed. Peter N. Gregory (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1987), 279–320, especially 281–284.

13. J. D. Frodsham, The Murmuring Stream: The Life and Works of the Chinese Nature Poet Hsieh Ling-yün (385–433), Duke of K’ang-Lo (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1967), 1:90. For the development of landscape verse, see 86–105.

14. Eliot Weinberger, Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem Is Translated (Mount Kisco, N.Y.: Moyer Bell, 1987).

15. Edward Conze, Buddhist Thought in India: Three Phases of Buddhist Philosophy (London: Allen and Unwin, 1962), 60–61.

16. Paul Williams, Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations (London: Routledge, 1989), 2.

17. The second character here is read ying, not jing (scene).

18. Williams, Mahāyāna Buddhism, 96–115.

19. Williams, Mahāyāna Buddhism, 112.

20. Conze, Buddhist Thought in India, 229.

21. Quoted in Neal Donner, “Sudden and Gradual Intimately Conjoined: Chih-I’s T’ien-t’ai View,” in Gregory, Sudden and Gradual, 201–226, especially 212–213.

22. Lu Qinli, comp., Xian Qin Han Wei Jin Nanbei chao shi (Poetry of the Qin, Han, Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983), 1:116–117. A rhyme-prose (fu) composition in the Han shu (History of the Han Dynasty) is also attributed to Ban Jieyu.

23. Gao, Tang Song shi juyao, 750.

24. In chapter 8, Zong-qi Cai describes the functional hierarchy of the four couplets using the traditional critical terms qi (introduction), cheng (elaboration), zhuan (transition), and he (conclusion). Traditional critics also frequently applied this quadripartite pattern to jueju, with the difference that each part was assigned to an individual line. However, difficulties arise when attempting to interpret jueju in this way, as it requires that the two lines in a couplet fulfill different functions, which is counter to usual poetic practice. If we instead employ a simpler bipartite pattern, then the terms remain useful. Thus the first couplet of a jueju is for introduction/elaboration, and the second is for transition/conclusion.

25. Luo Genze, “Qiyanshi zhi qiyuan ji qi chengshu” (The Origin and Maturation of Heptasyllabic Poetry), in Luo Genze gudian wenxue lunwen ji (Collection of Discourses on Classical Literature by Luo Genze) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji, 1985), 167–209.

26. Hu Yinglin, Shi sou, quoted in Fu and Liu, Qianshou Tangren jueju, 1020.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Egan, Charles. “A Critical Study of the Origins of Chüeh-chü Poetry.” Asia Major, 3rd ser., 6, pt. 1 (1993): 83–125.

Hsieh, Daniel. The Evolution of Jueju Verse. New York: Lang, 1996.

Lin, Shuen-fu. “The Nature of the Quatrain from the Late Han to the High T’ang.” In The Vitality of the Lyric Voice: Shih Poetry from the Late Han to the T’ang, edited by Shuen-fu Lin and Stephen Owen, 296–331. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

CHINESE

Fu Shousun 富壽蓀 and Liu Baishan 劉拜山, eds. Qianshou Tangren jueju 千首唐人絕句 (One Thousand Jueju by Tang Poets). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1985.

Luo Genze 羅根澤. “Jueju sanyuan” 絕句三元 (Three Sources of Jueju). In Luo Genze gudian wenxue lunwen ji 羅根澤古典文學論文集 (Collection of Discourses on Classical Literature by Luo Genze). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1985.

Shen Zufen 沈祖棻. Tangren qijueshi qianshi 唐人七絕詩淺釋 (Qijue Poems by Tang Poets, with Annotation and Commentary). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1981.

Sun Kaidi 孫楷第. “Jueju shi zenmeyang qilaide” 絕句是怎麽樣起來的 (How Did Jueju Develop?). Xueyuan 學苑 1, no. 4 (1947): 83–88.

Yang Shen 楊慎. Jueju yanyi jianzhu 絕句衍義箋注 (The Meaning of Jueju, with Annotation and Commentary). Edited by Wang Zhongyong 王仲鏞 and Wang Dahou 王大厚. Chengdu: Sichuan renmin chubanshe, 1984.

Zhou Xiaotian 周嘯天. Tang jueju shi 唐絕句史 (History of Tang Jueju). Chongqing: Chongqing chubanshe, 1987.