8

8

Pentasyllabic Regulated Verse (Wuyan Lüshi)

The Tang dynasty, one of China’s greatest dynasties, is seen by many as the golden age of Chinese poetry. It saw an unprecedented rise of poetry’s status. Poetry was made an essential part of the civil service examinations and became something of a national pursuit. The number of Tang poems composed and collected was staggering. The Quan Tang shi (Complete Shi Poetry of the Tang), compiled in 1705, contains nearly 49,000 poems by 2,200 poets.

Shi poetry reached its apex of development, marked by two important formal innovations, during the Tang. One was the rise of heptasyllabic poetry (chaps. 9 and 10), a form only sporadically used before the Tang, to compete with the long-dominant pentasyllabic poetry (chaps. 5–7). The other was the establishment of recent-style poetry (jinti shi), a heavily regulated type of shi poetry. The term “recent style” was invented to indicate a mandatory implementation of syntactic, structural, and tonal regulations in this new shi type, while the older term “ancient style” (guti) was broadened to designate all unregulated shi poetry. From the Tang onward, these two distinctive types constituted the main categories of shi poetry.

Recent-style poetry consists of two main subcategories of its own: lüshi (regulated verse) and regulated jueju (quatrains). Lüshi has a fixed length of eight lines, but its variant, pailü (extended regulated verse), is longer, ranging from ten all the way up to about three hundred lines. Jueju poems are invariably four lines. Both lüshi and jueju are further divided by line length into two: pentasyllabic and heptasyllabic.

Lüshi is undoubtedly one of the most complicated kinds of poetry in the world. In writing a lüshi poem, a poet must strictly follow complex, interlocked sets of rules for word choice, syntax, structure, and tonal patterning. Using a famous poem by Du Fu (712–770) as an example, I shall explain these sets of rules to lay the groundwork for an in-depth study of pentasyllabic lüshi in this chapter and heptasyllabic lüshi in the next. A good understanding of these rules is also important for the study of both pentasyllabic and heptasyllabic quatrains in chapter 10.

The introduction of mandatory sets of rules radically changed the dynamic of poetry writing. The challenge faced by a lüshi poet was not just to express himself, but to do so with self-imposed, severe constraints in practically all formal aspects. Inferior lüshi poets could easily become prisoners of all these formal rules and turn their works into a trivial language game. But in the hands of great poets, lüshi could become a most effective means of achieving the time-honored Chinese poetic ideal—to convey what lies beyond language. My close reading of four poems by Du Fu, Li Bai (701–762), and Wang Wei (701–761) will show how these three greatest Tang poets exploited various formal rules to the best advantage and created enchanting Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist visions of the universe and the self, with little use of abstract philosophical concepts.

THE LÜSHI FORM

The poem chosen to demonstrate the complex lüshi form is “Spring Scene,” written by Du Fu in March 757. About nine months earlier, the capital city of Chang’an had fallen into the hands of the rebel general An Lushan, and Du Fu had been captured and briefly detained by the rebel troops. This poem about his war-torn country and family is one of the best known and most frequently recited of the pentasyllabic lüshi poems.

The country is broken, but mountains and rivers remain,

2 The city enters spring, grass and trees have grown thick.

Feeling the time, flowers shed tears,

4 Hating separation, a bird startles the heart.

Beacon fires span over three months,

6 A family letter equals ten thousand taels of gold

My white hairs, as I scratch them, grow more sparse,

8 Simply becoming unable to hold hairpins.

[QTS 7:224.2404]

Reading this translation, an English reader may not find the kind of poetic greatness that he or she has encountered in, say, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, or Keats. There is no profound philosophical or religious contemplation, no astonishing flights of imagination, no dazzling display of poetic diction. Nonetheless, as I shall demonstrate, Du Fu’s “Spring Scene” deserves no less acclaim. The poetic greatness of Du Fu is of an entirely different kind. To appreciate it fully, we must go beyond the English translation and find out how the poem was composed and read in the original.

Word and Image

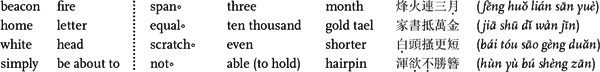

To begin, let us look at a word-for-word translation of the poem and consider its use of words and images:

[Tonal pattern I, see p. 171]

We are first struck by the extraordinary lexical economy: a total of only forty words. Many literary critics and scholars contend that the lexical economy stems from the noninflectional nature of the Chinese language. Inflection refers to the variation in words used to delineate the relations of tense, voice, gender, number, case, person, and so on in an alphabetic language like English. By contrast, in Chinese these complex relations are expressed by means of a rather small number of “empty words” (xuzi) with the aid of context and semantic rhythm (thematic table of contents 3.3). Unencumbered by inflectional variations, Chinese is far more economical than a Western language in its use of words. To attribute the lexical economy of Tang regulated poetry solely to the Chinese language itself, however, is not entirely convincing. The rise of this condensed poetic form also has much to do with the evolution of the Chinese poetic tradition. In a Tang regulated verse, forty or fifty-six words could do so much only because most of those words had accrued so much evocative power in the long poetic tradition before the Tang. Thanks to their repeated and innovative use during the millennium preceding it, many words and collocations had become imbued with various feelings and thoughts and could evoke touching scenes of history or fiction in the mind of the informed reader. There is no doubt that the increased efficacy of the poetic lexicon led to a steady shortening of poem length toward the end of the Six Dynasties (C7.3, 7.4, and 7.6) and to the eventual birth of the lüshi form in the Tang.

Imagistic appeal is another prominent feature revealed by the word-for-word translation. The poem is made up overwhelmingly of “content words” (shizi), words that have an actual and usually visualizable referent, thirty-six in all. Indeed, these content words produce vivid images of the following kinds:

Tangible things: grass, wood, flower, tear, bird, beacon, fire, home, letter, gold tael, head, hairpin

General scenes: country, mountain, river, city, spring

Concrete actions: shed, startle, scratch, hold

Mental conditions: feel, hate

Physical conditions: broken, remain, thick, separation, span, equal, white, able

Temporal conditions and quantities: time, three, month, ten thousand, shorter

Only the remaining four words (“even,” “simply,” “about to,” and “not”) are empty words. Such a lopsided ratio between content and empty words is characteristic of regulated verse in general and of High Tang regulated verse in particular. Having only forty or fifty-six words to work with, a lüshi poet often sought to maximize the use of imagistic content words while keeping empty words to a minimum.

The conspicuous absence of personal pronouns is another noteworthy feature apparent in the word-for-word translation. Contrary to the assertions by some scholars, the absence of personal pronouns is not characteristic of all Chinese poetic genres. For instance, the pronoun “I” (for example, wo, wu) appears profusely in many Han–Wei yuefu and gushi poems. Only in the Tang regulated verse do we observe an almost uniform exclusion of personal pronouns, especially that of the lyrical “I.” The hiding of the lyrical “I” produces a further liberating effect on the reader. Thanks to the absence in Chinese of the inflectional marking of time and space, Chinese readers enjoy much more freedom than readers of inflected languages in situating the depicted poetic experience. Moreover, with the lyrical “I” hidden, Chinese readers can easily enter the role of the poet and vicariously reenact his process of poetic creation. In consequence, the dynamics of reading is drastically changed from passive reception to active re-creation, as we shall see shortly.

Rules of Syntax

For readers familiar with Western modernist poetry, it is not hard to see that the three features just noted—lexical economy, maximization of imagistic appeal, and minimal use of nonimagistic words—are practically the same aesthetic ideals pursued by Imagist poets like Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. Indeed, the word-for-word translation of “Spring Scene” may seem at first glance to resemble an Imagist poem marked by a jumble of disjointed images. However, although the two traditions seem to share similar aesthetic ideals, they definitely follow opposite strategies to achieve them. While Imagist poets tend to maximize the impact of words and images by breaking up their syntactic connections, Chinese lüshi poets seek to produce the same impact by exploiting two covert nexuses of syntactic linkage inherent in the lüshi form.

The first is the nexus of words within a line. Taking another look at the word-for-word translation, we can clearly see that each line consists of a disyllabic and a trisyllabic segment, separated by a caesura (as indicated by the dotted line). Each trisyllabic unit has a one-character word and a binome, separated by a very slight pause (as indicated by ◦). So, instead of being a cacophony of disjointed words, each line creates a pleasurable 2 + 3 semantic rhythm, or, more accurately, a 2 + (1 + 2)/2 + (2 + 1) rhythm (thematic table of contents 3.3). This semantic rhythm, first firmly established in Han pentasyllabic yuefu and gushi poetry during the third century, is faithfully observed in pentasyllabic lüshi and jueju. It is also adopted intact in heptasyllabic lüshi and jueju.

The second is the nexus of words between the two lines of a parallel couplet. In a lüshi poem, the two middle couplets are strictly required to be parallel in thematic categories as well as in parts of speech. “Spring Scene” provides a well-wrought parallelism of this kind. In the second couplet, we note a neat pairing of “feel” with “hate” (emotive verbs), “time” with “separation” (nouns of time and space), “flower” with “bird” (nouns of natural life), “shed [tears]” with “startle” (verbs of emotional response), and “tear” and “heart” (nouns related to emotion). In the third couplet, there is the meticulous matching of “beacon fire” with “home letter” (binomes relating to the transit of messages), “span” with “equal” (verbs indicative of temporal-spatial linkage), “three” with “ten thousand” (numbers), and “month” with “gold tael” (nouns of measurement).

These two nexuses of words signify a well-codified web of prescribed syntactic links underlying the forty or fifty-six words and integrating them into a unified whole.

Rules of Structure

There are also two structural rules, one mandatory and the other optional, that serve to bind together the four couplets of a lüshi work. The first rule is a mandatory alternation of nonparallel and parallel couplets (duiju). The majority of lüshi works begin with a nonparallel couplet, continue through two parallel couplets, and end with another nonparallel couplet. A lüshi poet normally should not end a poem with a parallel couplet, although he could choose to begin with a parallel one. This alternation of the two couplet types gives rise to a tripartite structure of beginning, middle, and end. This structure does not, however, effect a straight sequence of narration or description. Instead, a poem’s middle part often functions to suspend the temporal flow and allow for an intense perception and reflection in the timeless lyrical present. References to a specific time and place seldom occur in this middle part. In “Spring Scene,” for instance, the two middle couplets are composed solely of words and images detached from any specific time and place.

The second structural rule is the optional observance of a four-stage progression: qi (to begin, to arise), cheng (to continue, to elaborate), zhuan (to make a turn), and he (to conclude, to enclose). This four-stage progression was widely observed in High Tang lüshi. In every poem discussed in this chapter, for instance, the four couplets are cast in this fashion. Now let us trace the four-stage progression in “Spring Scene”:

Performing the function of qi, the opening couplet sets the time, place, and theme for the entire poem. In the first line, what is human (“country”) is set against what is natural (“mountain,” “river”), and what is “broken” by men is pitted against what “remains” in nature. The contrast between human destruction and nature’s luxuriance is not explicitly stated but implied in the second line. The thick growth of grasses and trees clearly signifies the state of an abandoned city in the springtime.

The second couplet performs its expected function of cheng: to continue by focusing on a set of paralleled images. Turning away from the external scene, the poet here begins his mental engagement with the images of “flower” and “bird.” The fixing of his inward gaze on these two images eventually leads him into a reverie-like experience. Instead of giving a discursive account of this experience, however, Du Fu lets us directly experience it through a masterful play of syntactic ambiguities. The omission of the subject in the disyllabic segment allows us to infer different subjects and therefore have five different readings of the couplet (the fifth reading is discussed in chap. 18). First, we can take the poet himself to be the implied subject of both the disyllabic and trisyllabic segments, and give this reading of the couplet:

I feel about this wretched time so badly

that even flowers make me shed tears.

I hate separation so much

that a bird[’s call] startles my heart.

In this reading, the verbs “shed” and “startle” are taken in the causative sense. The poet is the real subject, who sheds tears and gets startled, while the flowers and the bird are merely nominal subjects or simply the cause of the poet’s emotional response.

Then, with a slight stretch of the imagination, we may combine the word “time” with “flower” and “separation” with “bird” to produce two binomes: seasonal flower and straying bird. This leads to a second reading of the couplet:

Feeling affected by the seasonal flowers,

I shed my tears.

Hating to see the straying bird,

My heart is startled [by its call].

This reading entails a change of semantic rhythm to 3 + 2, or (1 + 2) + 2. The 2 + 3 rhythm of a pentasyllabic line generally could not be altered, but Du Fu is known to have deliberately violated established semantic rhythms to achieve a special effect (a more detailed discussion of this issue appears in chap. 9). Thus this second reading is quite plausible.

Next, we can take the flowers and bird to be the subjects of the trisyllabic segments and come up with a third reading of the couplet:

As I feel the wretched time, flowers shed tears,

As I hate separation, birds are startled in their hearts.

Finally, we can take the flowers and the bird to be the subjects of both the disyllabic and trisyllabic segments. This allows for the fourth reading:

Feeling the wretched time, flowers shed tears,

Hating separation, birds are startled in their hearts.

The four readings of the second couplet present three distinct perspectives on human suffering. In the first two readings, human suffering is regarded from a purely human point of view. From such a perspective, nature appears separate from man and hence indifferent to his suffering. Worse still, nature’s indestructibility and perpetual renewal, and its springtime luxuriance, only serve to painfully remind man of his frailty and misery. This unsympathetic contrast of man with nature is a time-honored theme in Chinese poetry and is unambiguously employed in the first couplet of this poem. Although this contrast is sustained by the first two readings, it is subverted in the third and fourth readings. In the third reading, human suffering is viewed from the broader perspective of man and nature as a whole. When so viewed, man’s suffering is none other than nature’s, and vice versa. For this reason, there is a touching resonance between man’s lamenting his wretched time and flowers’ shedding their tears. In the fourth reading, human suffering is viewed from the perspective of an empathetic nature. Here, it is not man but nature that gives expression to human sorrow.

The succession of these three perspectives reveals a radical change of realities as perceived by the poet: from a disheartening juxtaposition of suffering man and indifferent nature, to the mutual resonance between man and nature, and finally to a complete empathy between man and nature. As we follow this change of perceived realities, we can vicariously relive the poet’s innermost experience as he deepens his observation into a reverie.

This third couplet faithfully performs the function of zhuan: to engineer a turning by introducing a contrasting set of parallel images. The turning in this particular case is a shift from nature to the human world. In contrast to the flowers and bird, we have now things of the human world: “beacon fire” (fenghuo) and “home letter.” At first glance, these two seem to make an odd pair, as there is no apparent similarity between beacon fire and letter. But once we learn of the ancient practice of lighting a fire atop a watchtower to relay the message of an invasion by nomads, we can see that the two binomes make a perfect pair. Du Fu’s exploitation of the double entendre of fenghuo is indisputable. While using this meaning of “beacon fire” to produce an ingenious parallelism with “home letter,” he taps its other meaning as “flames of war” to reveal the causes of the country’s ruin and the separation of his family. The verbs “span” and “equal” are also perfectly paired, as they each denote a linkage in space or time. The lighting of a beacon fire normally signifies a linkage of two or more points in space, and so does the delivery of a family letter. However, the “beacon fire” and “home letter” are instead perceived to span time. “Three months” explicitly marks a long duration. In Chinese, the word san can function as either a cardinal number (three) or an ordinal number (third), depending on the context in which it occurs. According to many scholars, it works both ways here in the binome sanyue. First, “three months” furnishes a nice parallelism with “ten thousand gold taels” in the next line. It seems to denote the first three months of 757, when the rebels and government troops fought pitched battles. It may also allude to a historical event that occurred in 206 B.C.E.—the three successive months of the burning of the Qin capital (located in essentially the same place as the Tang capital) after the rebel forces of Xiang Yu (232–202 B.C.E.) had overrun and torched it. Then, “third month” refers to March 757, when Du Fu composed this poem. The verb lian (span) leads to the suggestion that Du Fu might have been thinking of the yearlong warfare spanning the two “third months” (March 756 and March 757). “Ten thousand gold taels” is far less ambiguous. It is meant to signify the high value ascribed by Du Fu to a family letter due to the extraordinary length of separation. It also reveals the extreme difficulty of communication because of the partition of the land by the warring parties. Finally, we should take note of a touch of irony in this third couplet: it is two linking verbs that set forth all the temporal and spatial realities of separation.

The final couplet unfailingly performs its expected twin functions of he: to move toward a closure and to make a well-rounded whole (yuanhe) by joining beginning and end. If, in the third couplet, we see a shift from the country to the family, here we observe a further shift from the family to the poet himself—the quickened process of his aging. A return to the poet’s experiential world in the final couplet is a conventional move in a lüshi poem. As noted earlier, the two middle couplets are strictly parallel and usually stripped of references to a specific time or place, thus projecting a timeless world in the imagination of the poet. By contrast, the final couplet is by convention nonparallel and, as such, particularly conducive to a realistic portrayal of the poet’s present condition. Consider how the dispensing of parallel syntax enables the poet to depict his own condition with a long, uninterrupted sentence: “My white hairs, as I scratch them, grow more sparse, / Simply becoming unable to hold hairpins.”

Unlike in the first three couplets, there is a single subject, the white-haired head, and all the remaining words are devoted to describing it. In presenting such a close-up portrayal of his white-haired head, the poet intends to tell us not so much his physical condition as his innermost suffering. Although it may seem to be an understatement of the poet’s intense emotion, this close-up is actually a very powerful expression of it. When a poet’s sorrow reaches the point of rapidly ruining his health, what better way can he find to indicate the depth of his suffering than by depicting the destruction of his body? While rendering pointless any abstract emotive words, this evocative image of the poet’s white-haired, balding head inevitably harks back to the broken country in the first line and thus produces the dual effect of “moving in a cycle, going and returning” (xunhuan wangfu). As the sensitive reader goes through again the images of the broken country, the scattered family, grieving nature, and the aging poet, he perceives a grand Confucian cosmic vision, characterized by the inseparable, empathetic bonds a moral man forges with his fellow human beings, his country, and the universe at large. By his creation of such a Confucian vision of the universe and the self, Du Fu earned the appellation of “poet-sage” (shisheng), the highest honor to which a Confucian-minded poet could aspire.

Rules of Tonal Patterning

Chinese tonal meter is much more complex than English poetic meter. Whereas a sonnet writer only needs to alternate five unstressed and stressed syllables within a line, a lüshi poet has to do more. He must meticulously alternate level and oblique tones between as well as within lines. Level tones refer to the first and second tones—the flat tone (for example, mā) and rising tone (má)—in Mandarin. Oblique tones consist of the third and fourth tones—the falling-rising tone (mă) and the short falling tone (mà)—of Mandarin and the entering tones (rusheng) of Middle Chinese.1 This patterning of tones is constructed with a precision that leaves nothing to chance.

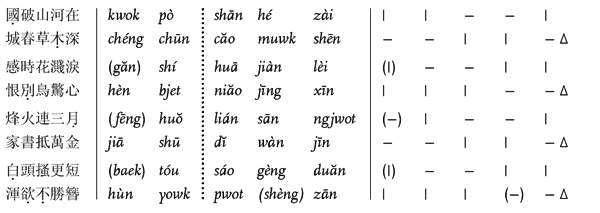

Ironically, this precision is what makes the complex tonal patterning easy for us to observe and master—it becomes a fairly simple matter of observing its three basic rules.2 Turning again to “Spring Scene” for our example, let us go through these rules and work out all the major tonal patterns of recent-style shi poetry, as shown in the table.

The first rule demands a maximum contrast of tones within a line. This rule dictates that the tones of a pentasyllabic line must appear in two opposite pairs, a pair of level tones (─ ─) and a pair of oblique tones (│ │), with an odd “one” (─ or │) tipping the balance. This casting of tones mirrors the semantic rhythm of 2 + (1 + 2/2 + 1). If the odd one is placed at the end of a line, we have the first two of the four line types in recent-style shi poetry: (1) │ │ ─ ─ │ and (2) ─ ─ │ │ ─. If it is placed at the beginning of a line, we have the other two line types: (3) ─ ─ ─ │ │ and (4) │ │ │ ─ ─.3

The second rule demands a maximum contrast between the two lines of a couplet. In a standard couplet, the tonal combination of the opening line is antithetically matched by that of the closing line. For instance, if the opening line is │ │ ─ ─ │, the closing line must be ─ ─ │ │ ─. Alternatively, ─ ─ ─ │ │ is to be followed by │ │ │ ─ ─. These two line combinations (1 and 2; 3 and 4) constitute the two standard couplets in recent-style shi poetry.

Tonal Pattern of “Spring Scene”

Reverse combinations of the four line types (2 and 1, 4 and 3), however, are not permissible. What complicates the matter here is two unbending rhyming rules: all even lines must rhyme and all rhyming words must be in level tones (as indicated, in the tables, by the hollow triangular rhyme marker △). So line types 1 and 3, which end with oblique tones, cannot be the closing lines of a couplet. The resulting loss of two alternative couplet forms is, however, partially compensated for by the formation of two variant couplets. Poets choosing to employ rhyme in both lines, instead of in just the second line, of the opening couplet had no choice but to use both line types 2 and 4, which end with a level tone. They could combine them in the order of 2 and 4 (─ ─ │ │ ─, │ │ │ ─ ─) or 4 and 2 (│ │ │ ─ ─, ─ ─ │ │ ─). It is important to stress that these two variant couplets are used only in the opening couplet.

The third rule demands a partial equivalence between two adjacent couplets. Known as nian (to make things stick together), this rule is intended to help integrate the relatively self-contained couplets into a whole. It stipulates a correspondence in tone between the first two words in the closing line of a couplet and those in the opening line of the next couplet (as indicated, in the table showing the standard jueju tonal patterns, by the shaded areas). To avoid monotony, these two adjacent lines cannot be of the same line type. For instance, ─ ─ │ │ ─ cannot be followed by another ─ ─ │ │ ─. The next line must be ─ ─ ─ │ │.

So this leaves us with only two possible ways of combining two couplets into a quatrain. If line type 2 is employed in the second line, it must be followed by line type 3 in the third line; if line type 4 is employed in the second line, it must be followed by line type 1 in the third line. This combining process yields the two standard jueju tonal patterns, as shown in the table.

The use of rhyme in both lines of the opening couplet gives rise to two variant jueju tonal patterns, as shown in the next table. If we compare this table with the preceding one, we can clearly see that the two variant tonal patterns are almost identical to the two standard ones, with only a slight one-line variation (as indicated by the shaded areas). In these two tables, I have added in parentheses the tones for the two additional characters in a heptasyllabic line, which contrast with those of the first two words of a pentasyllabic line. As shown by the vertical lines, the tonal patterns of heptasyllabic jueju are an exact copy of those of pentasyllabic jueju, with only the addition of two more characters.

Standard Jueju Tonal Patterns

Variant Jueju Tonal Patterns

Once we have worked out the four jueju tonal patterns, it is easy to construct the four lüshi tonal patterns. All we have to do is follow the same rule of partial equivalence between couplets and add two more couplets—that is, another quatrain—to each of the four jueju tonal patterns. This brings us to the four lüshi tonal patterns. As shown by the horizontal dotted lines in the two tables, the four lüshi tonal patterns constitute a doubling of the two standard jueju tonal patterns. This doubling is exact and complete in the two standard lüshi patterns, but involves a slight, one-line variation (the shaded part) in the two variant lüshi tonal patterns.

Standard Lüshi Tonal Patterns

Variant Lüshi Tonal Patterns

In the final analysis, we can say that there are only two basic types of tonal patterning: type I and type II. All the tonal patterns presented are merely their derivatives at different removes. A fourfold division (I, II, Ia, IIa) is derived through a slight variation of the opening line for the sake of rhyming. At the next remove, an eightfold division is derived through a further differentiation by poem length (four-line jueju versus eight-line lüshi). At the last remove, even a sixteenfold division may be derived through yet another differentiation by line length (pentasyllabic versus heptasyllabic). This analysis, I hope, lays bare the inherent relationships among all the tonal patterns of recent-style shi poetry.

It is important to remember that the tables represent perfect tonal patterns that exist in theory but not always in practice. Rigid adherence to a tonal pattern can lead to a sacrifice of meaning for the sake of tonal regularity. So poets often took advantage of a certain amount of freedom to diverge from the set tonal patterns. For an example of the employment of one of these tonal patterns, let us return to Du Fu’s “Spring Scene.” The tonal pattern employed is type I. With four entering tones (kwok, bjet, yowk, pwot) restored, this poem demonstrates a much more rigorous observance of the required tonal pattern than if read in modern standard Chinese. Nonetheless, we can note four instances of variation from the established tonal pattern. For instance, from a purely technical point of view, the first character in line 3 should be in level tone, but the character găn is in oblique tone. Generally speaking, it is often permissible to deviate from the required tones of the first and third characters in a pentasyllabic line or the first, third, and fifth characters in a heptasyllabic line. All but one of the four violations here occur in the first word of a line. Students who wish to reconstruct the tonal pattern of a lüshi or regulated jueju poem need only mark out its alternation of level and oblique tones and then find out to which tonal pattern it conforms. The tonal patterns for all recent-style shi poems presented in this book are identified at the end of each citation and listed in the preceding tables.

THE LÜSHI FORM AND YIN-YANG COSMOLOGY

The establishment of any regulated poetry, whether Chinese lüshi or English sonnets, represents an endeavor to formalize and amplify our delight in the natural order of language—the rhythm of both its sounds and its sense. On a more abstract plane, the lüshi form may be seen to reflect the order of the universe at large. To embody the grand cosmic order in a finite work has been a high artistic ideal long pursued by the Chinese, and the lüshi form is a prime example of this quest. In collectively developing the lüshi form during the Qi–Liang and the Early Tang periods, Chinese poets, consciously or unconsciously, modeled it on the yin-yang cosmological scheme to such an extent that it practically became a microcosm of that scheme. Indeed, all its syntactic, structural, and metrical rules bear the imprint of the yin-yang operation as represented by this well-known symbol:

In this symbol, the sharp contrast of the black and white parts is meant to show the opposition of the basic cosmic forces of yin and yang. This fundamental opposition is mirrored in the major aspects of the lüshi form. As we have seen, its basic semantic rhythm consists of a contrast between a disyllabic segment and a trisyllabic segment that is usually made up of a binome and a monosyllabic word. Also, the construction of a parallel couplet often entails a matching of opposite or different images (heaven versus earth, and so on). The organization of four couplets, too, often involves a broad, bipartite contrast between nature and man, scenes and emotions. On the level of prosody, we note a maximum contrast between level and oblique tones both within a line and between two lines of a couplet.

The black and white dots inside the opposed areas of the symbol are meant to show a subtle equivalence between yin and yang that accompanies and tempers their mutual opposition. In the lüshi form, too, such an equivalence of bipolar opposites is readily noticeable. For instance, the two middle couplets each demand a stringent equivalence in parts of speech, often set against an antithesis in meaning. In addition, there is the prosodic rule of partial equivalence (nian) between any two adjacent couplets.

The gently curved borderline between the white and black parts of the symbol is intended to indicate a tendency of yin and yang to transform themselves into their opposites—yin becomes yang, and yang becomes yin. The dynamic interplay of yin and yang thus follows a cyclical path of thrust and counterthrust, ascendancy and decline, instead of a teleological path of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. In lüshi prosody, the regular alternation of parallel and nonparallel couplets traces a similar cyclical path.

Finally, the circle of the yin-yang symbol itself speaks to the all-inclusiveness, completeness, and eternity of the yin-yang operation. In the lüshi form, the repetition of the same or essentially the same tonal patterns in two quatrains and the joining (he) of the beginning and ending couplets are no doubt intended to create the image of a cyclical, perpetual return that resonates with the everlasting cosmic order.

VISIONS OF THE UNIVERSE AND THE SELF

That the lüshi form represents a microcosm of yin-yang cosmology does not mean that all lüshi poems project a grand cosmic vision. In fact, countless lüshi poems are devoted to trivial subjects—although even the trivial gains significance when presented in the lüshi form. Nonetheless, when it reached its apex of development during the High Tang, the lüshi did become a prized vehicle for conveying grand cosmic visions. In each of the three poems to be examined, we perceive a distinct vision of the universe and the self.

By the Jiang and Han rivers broods a homeward traveler,

2 Between heaven and earth is one worthless scholar.

A lone cloud, and the sky (and I) join in being faraway,

4 A long night, and the moon (and I) share the loneliness.

The setting sun—yet I remain ambitious at heart,

6 The autumn wind—from illness I will recover.

From antiquity all the old horses that people kept,

8 Not always were chosen for long distances.

[QTS 7:230.2523]

[Tonal pattern I, see p. 171]

This poem by Du Fu disproves the simplistic notion that poetry is a temporal art, while painting is a spatial one. It lends itself to both a spatial and a temporal reading. If we divide the poem into two columns along the vertical line separating the disyllabic and trisyllabic segments, we may read it vertically, column by column. Such a reading is spatial in the sense that it breaks up the line-by-line sequence of normal reading to reveal two highly coherent clusters of images. One consists of images of the universe, ranging from the “Qian Kun” (an alternative name for heaven and earth) to the panoramic river scenes and to atmospheric phenomena (“cloud” and “autumn wind”). The other cluster consists of a series of remarks about the self: Du Fu as a “homeward traveler,” his sense of failure, his exile and loneliness, and his determination to achieve his ambitions despite his illness and aging. While this spatial reading underscores the juxtaposition of the universe and the self, a temporal reading reveals the poet’s inner process of observation and contemplation.

Reading the poem line by line, we see a topic + comment construction in all but the last two lines (thematic table of contents 5.3). In each of the first six lines, the initial disyllabic segment presents a topic, a broad cosmic image observed by the poet; the trisyllabic segment, however, introduces a comment induced by the act of observation. In the opening couplet, the immense universe (“the Jiang and Han rivers” and “heaven and earth”) induces a pathetic and diminutive self-image: “homeward traveler” and “worthless scholar.” In the second couplet, the images of “lone cloud” and “long night” thicken the mood of loneliness and melancholic brooding, but the ensuing comments signify a slight relief from loneliness through an empathetic joining of man and nature. Like the second couplet of “Spring Scene,” this second couplet creates the idea of a nature–man empathy through a deft manipulation of syntactic ambiguities. Here, “join” and “share” imply two or more subjects, but only one is made explicit (“sky” and “moon”). Depending on which implicit subject(s) we supply, this couplet lends itself to three different readings:

A lone cloud and the sky are together faraway,

A long night and the moon share the loneliness.

A lone cloud, and the sky (and I) are together faraway,

A long night, and the moon (and I) share loneliness.

A lone cloud—the sky (and I) are together faraway,

A long night—the moon (and I) share the loneliness.

The coexistence of these three possible readings serves to create a sense of togetherness in the world—the togetherness of inanimate things and the togetherness of nature and man. The conception of this pervasive togetherness reveals a lessening of the poet’s loneliness and prepares us for a rather dramatic “turning” in the third couplet. The turning is dramatic because of the unusual juxtaposition of “setting sun” and “autumn wind”—two common images of decay and melancholy—with a surprisingly positive attitude toward the onset of illness and old age. The setting sun only spurs the poet to strive for great accomplishments, and the autumn wind only speeds up his recovery from illness. Echoing this optimistic note, the poem ends with a metaphorical statement about the true worth of an aging man.

The poet with whom Du Fu is often paired is his friend Li Bai, widely known as the “poet-immortal” (shixian). Widely hailed as the two greatest Chinese poets, they are the subject of a continuing debate about which is greater. They have often been perceived to be diametrically opposite types. Du Fu is sober, earnest, and morally committed, whereas Li Bai is inebriated, carefree, and transcendent. Although such a simple dichotomy inevitably obscures the complexity of the two poets’ lives and works, it has taken hold of the popular imagination. Consequently, they are both best remembered for those works that reveal these character traits. While many of Du Fu’s great poems are lüshi works, most of Li Bai’s best-loved and most widely recited works are ancient-style poems (chap. 11). The highly restrictive lüshi form seems to have been ill suited to Li Bai’s unbridled temperament and poetic style. Yet, in fact, he wrote a number of lüshi poems, in which we catch a glimpse of the quintessential Li Bai:

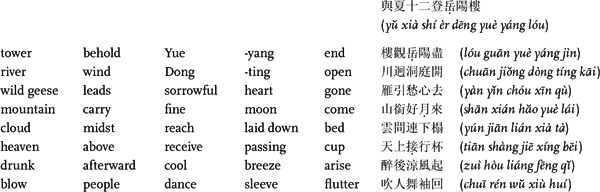

Climbing the Yueyang Tower with Xia Shi’er

From the tower I look afar to where the Yueyang region ends,

2 The river winds along to where Dongting Lake opens.

The wild geese, taking along the heart’s sorrow, have gone,

4 The mountains, carrying the fine moon in their beak, come.

In the midst of clouds I reach the honored guest’s bed.

6 In heaven above I receive the passing wine cup.

After I have gotten drunk a cool wind rises,

8 Blowing on me, sending my sleeves dancing and fluttering.

[QTS 6:180.1838]

[Tonal pattern II, see p. 171]

The opening couplet shows the poet in the act of viewing a panoramic scene. In the second couplet, his gaze shifts to two concrete images. The flying “wild geese,” a common image for homesickness, are here used to signify the relief of homesickness, or the “heart’s sorrow.” This transformation of a conventional image is followed by a sudden flight of imagination: the mountains have become giant birds “carrying the fine moon in their beak” and flying toward us.

The third couplet engineers a turn quite characteristic of the poet-immortal: a flight into the celestial world. Taking the poet as the implicit subject, however, we can render the couplet as follows: “In the midst of clouds I reach the honored guest’s bed. / In heaven above I receive the passing wine cup.” The appearance of the poet in the final couplet makes this reading sensible and appropriate. Here Li Bai does not make man and nature equal companions, as Du Fu does, but elevates man or, rather, himself above nature to the extent that he becomes an immortal residing amid clouds and receiving a passing cup in heaven. Like Du Fu, he avails himself of personification. But for him, personification is largely a means of turning nature into a joyful playmate. The wild geese that take away the heart’s sorrow and the mountains that bring in the fine moon for enjoyment become his imagined playmates.

As Li Bai consistently endows nature with his unique character traits, it is little wonder that most of the personifying verbs in his poems are not those of grief and lamentation (like “shed tears”) but depict instead energetic, sprightly, and often magical action. In transforming nature into a playmate at his bidding, he in effect elevates himself to the status of the creator or master of the universe. He is not at all shy about this, and in fact speaks explicitly in the voice of the heavenly master in a poem like “Drinking Alone Under the Moon, No. 1” (Yue xia duo zhuo [QTS 6:182.1853]). His lively self-deification as lord of the universe is considered by many as the hallmark of Li Bai’s greatest poems. At the very least, it sets his poems apart from the earlier quotidian poems on roaming immortals (youxian) and helps earn him the title of poet-immortal. Moreover, it has inspired the great ci poems of heroic abandon by Su Shi (1037–1101) and Xin Qiji (1140–1207) (C12.2 and C12.5).

In stark contrast to Li Bai’s unabashed deification of the self, we observe a deliberate suppression of the self in this poem by Wang Wei:

Taiyi Peak approaches heaven’s capital,

2 The linked mountains extend to the edge of the sea.

White clouds, when I look back, converge,

4 The greenish haze, once I walk in to see it, disappears.

The divided regions, when seen from the middle peak, change,

6 Shaded or in the sun, the myriad valleys look different.

I wish to find lodgings for the night in a dwelling of man,

8 Across the brook calling to a woodcutter.

[QTS 4:126.1277]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 172]

Unlike Du Fu and Li Bai, Wang Wei does not tell us about his emotional and physical conditions or his imagined feats of transcendence. Instead, he leads us through successive acts of intense visual perception. In the first couplet, he points out the Zhongnan mountains in the distance, first directing our gaze upward via Taiyi Peak to heaven and then horizontally along the linked mountains all the way to the sea. In the second couplet, he leads us away from the panoramic scene and engages us in a hide-and-seek with two atmospheric images up close. By a turning in the third couplet, he changes the object of observation from the mountains to the vast plain below. This new panoramic scene delights us with its kaleidoscopic formation of patterns and colors under the effects of the sunlight and clouds. In the last couplet, he shifts back to a nearby scene and shows us traces of man: a woodcutter and a call to him from the other side of a valley brook, asking for a place to stay for the night.

A renowned painter credited with founding the Southern School of Landscape Painting, Wang Wei is often praised for the painterly qualities in his poetry. This poem is certainly an excellent example of the painterly qualities in his finest landscape poems. It alternates panoramic scenes with close-ups and delights us with its delicate play of colors (“white clouds” versus “greenish haze,” the chiaroscuro effect of the sun). It constantly shifts the angle of observation—now horizontal and vertical, now from below upward and from above downward. All these painterly qualities work together perfectly to yield a rare feast of visual pleasure. Moreover, the depicted scenes and images trace the stages of a day’s journey of landscape viewing: starting with a distant view (first couplet), continuing through an uphill climb (second couplet) and the arrival at the summit (third couplet), and ending with a descent into the valley at dusk (last couplet).

This poem is also a perfect example of an even more important quality of Wang Wei’s finest landscape poems: their artistic embodiment of a Buddhist worldview. Interestingly, if we direct our attention to the last word in each line of the two middle parallel couplets, we notice a string of four terms frequently used in Chinese Buddhist texts to explain the Buddhist worldview: he, wu, bian, and shu. The word he is part of the term hehe (Sanskrit sāmagari), which refers to a composite of causes and conditions (yinyuan; Sanskrit hetupratyaya) underlying the existence of all phenomena, objective or subjective. The word wu is part of the term wu’er (negation of two sides; neither … nor), which denotes a Mahayanist exercise of double negation aimed at preventing the reification of any thing or concept as the ontological absolute. Insofar as all things, physical existences or mental constructs, arise from a composite of causes and conditions, they cannot possibly possess any essential substance, and therefore are all subject to mutability (bian) and differentiation (shu). It follows that Buddhist truth is neither being nor emptiness (śūnyatā).

Wang Wei’s brilliant employment of these four terms in this poem attests to his consummate achievement as a visionary poet. With a touch of genius, he turns each of the four abstract philosophical terms into a lively verse eye, a pivotal word that animates an entire poetic line (thematic table of contents 4.2). Together, these four verse eyes engender a sustained play of perceptual illusion. The first two verse eyes, he (converge) and wu (disappear), render the atmospheric images of clouds and haze ever so elusive that their very existence becomes a question. Next, the other two verse eyes, bian (change) and shu (become different), turn the valleys and the plain into a spectacle of changing shapes and colors. This play of perceptual illusion culminates in the final couplet. There, we are led to envision a dwelling of man hidden in the woods, and yet we cannot actually see it and have to ask the woodcutter for its whereabouts. We seem to see a woodcutter out there, and yet we cannot get close and have to shout across the valley brook. The echoes of our own call in the empty valley, we surmise, may be the only answer we get. As this perceptual illusion reaches its climax, a sensitive reader may experience something like Buddhist enlightenment, or at least share the Buddhist insight into the illusory nature of existence and emptiness, the universe and the self. For this perfect fusion of the artistic and religious, the sensory and suprasensory, Wang Wei is rightly honored with the title “poet-Buddha” (shifo).

NOTES

1. All entering tones end with an unaspirated consonant: p, t, or k. Although prevalent during Tang and Song times, entering tones no longer exist in modern standard Chinese but are preserved in many regional Chinese dialects like Cantonese and Hakka. Owing to its loss of entering tones, modern standard Chinese is considered by many to be less desirable than a dialect like Cantonese for reading Tang regulated verse out loud. (See, at the end of this volume, “Phonetic Transcriptions of Entering-Tone Characters.”)

2. I am deeply indebted to my teacher Professor Yu-kung Kao for his insightful comments on the three rules.

3. The fifth and sixth possible line types (│ │ ─ ─ ─ and ─ ─ │ │ │) are not employed in recent-style shi poetry.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Kao, Yu-kung. “The Aesthetics of Regulated Verse.” In The Vitality of the Lyric Voice: Shih Poetry from the Late Han to the T’ang, edited by Shuen-fu Lin and Stephen Owen, 332–385. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Kao, Yu-kung, and Mei Tsu-lin. “Meaning, Metaphor, and Allusion in T’ang Poetry.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 38, no. 2 (1978): 281–356.

———. “Syntax, Diction, and Imagery in T’ang Poetry.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 31 (1971): 49–136.

Owen, Stephen. The Great Age of Chinese Poetry: The High T’ang. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1981.

Varsano, Paula M. Tracking the Banished Immortal: The Poetry of Li Bo and Its Critical Reception. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2003.

Wang Wei. The Poetry of Wang Wei: New Translations and Commentary. Translated by Pauline Yu. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980.

CHINESE

Chen Tiemin 陳鐵民, ed. Wang Wei ji jiaozhu 王維集校注 (The Works of Wang Wei, with Collected Collations and Commentaries). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997.

Gao Buying 高步瀛, ed. Tang Song shi juyao 唐宋詩舉要 (The Essential Shi Poems of the Tang and Song). 2 vols. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1978.

Qiu Zhao-ao 仇兆鰲 (1638–1713), ed. Du shi xiangzhu 杜詩詳注 (The Poetry of Du Fu, with Detailed Commentaries). 5 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1979.

Qu Shuiyuan 瞿蛻園 and Zhu Jincheng 朱金城, eds. Li Bai ji jiaozhu 李白集校注 (The Works of Li Bai, with Collected Collations and Commentaries). 4 vols. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1980.