18

18

Rhythm, Syntax, and Vision of Chinese Poetry

Line configuration and poetic vision are probably the two most important subjects of inquiry in traditional Chinese poetry criticism. The study of line configuration, called jufa (sentence rules), is essentially an analysis of how monosyllabic and disyllabic words form a poetic line or couplet to create certain unique rhythm and aesthetic effect. Poetic vision, called yixiang/yijing (idea-image/idea-scape), refers to a heightened presentation of outer and inner realities, characterized by the “beyondness” of one kind or another—“the meaning beyond words” (yan wai zhi yi), “the image beyond images” (xiang wai zhi xiang), “the scene beyond scenes (jing wai zhi jing),” and the like. The traditional study of poetic vision is usually an impressionistic description of such “beyondness” in the rarefied terms of aesthetics.

Bifurcated as they seem, concrete line configuration and nebulous poetic vision are inextricably intertwined. While line configuration provides the foundation for the creation of poetic vision, poetic vision breathes life into poetic lines, making them dynamic and engaging. Traditional Chinese critics became aware of this connection long ago. As early as the sixth century, Zhong Rong (ca. 469–518) pointed out the connection between pentasyllabic lines and new pleasurable, inexhaustible tastes of poetry.1 More than a millennium later, the Qing critic Liu Xizai (1813–1881) went one step further to explore the deeper connection between internal rhythms of tetrasyllabic, pentasyllabic, and heptasyllabic lines and different poetic visions.2 In a way, our close reading of the 143 poems in this anthology is an innovative continuation of this millennia-old critical endeavor. Drawing from modern linguistic and aesthetic theories, many of us have sought to understand why poetic lines, if configured in certain manners, can yield ineffable aesthetic experience. Here I shall synthesize our findings and present a broad outline for a systematic study of the rhythms, syntax, and visions in Chinese poetry.

RETHINKING JUFA: TOWARD AN INTEGRATION OF RHYTHM AND SYNTAX

Rhythm and syntax are two principal issues in the study of line configuration in Chinese poetry. Rhythm primarily concerns the oral-aural dimension and syntax primarily the spatiotemporal-logical dimension in the ordering of words.

In studying line configuration, traditional Chinese scholars were preoccupied with rhythm to the neglect of syntax. Six Dynasties critics like Zhi Yu (d. 211) and Liu Xie (ca. 465–ca. 522) recognized that major genres and subgenres each have their distinctive line types. Some employ lines of fixed length (trisyllabic, tetrasyllabic, pentasyllabic, heptasyllabic, and so on), and others feature lines of irregular length. These two broad categories of poetry have been labeled qiyan shi (poetry of equal-character lines) and zayan shi (poetry of variable-character lines), respectively. These critics also held that this rich variety of line types resulted from efforts to accord poetic speech with different external musical rhythms.3 Beginning from the Song dynasty, critics became aware of internal line rhythm that arises from a fixed pattern of mandatory pauses between monosyllabic words and disyllabic words. This internal rhythm is semantic in the sense that it predetermines how characters are to be clustered to generate meaning. Consequently, it not only intensifies our experience of the sound but also contributes to the sense of poetry. A clear recognition of this crucial semantic importance did not occur until Qing times, when Liu Xizai and others began to explore the aesthetic implications of various shi rhythms.

The neglect of syntax by Chinese critics has much to do with the Chinese language itself. As a notion originating in Western linguistics, syntax denotes the spatiotemporal-logical grid in which words are arranged. Chinese is a noninflectional language, and its words are not cast into a fixed spatiotemporal-logical relationship by tense, voice, and other inflectional tags. Syntactic linkage is effected by a well-ordered, readily discernible semantic rhythm, with or without grammatical function words (xuzi). This semantic rhythm normally gives the reader ample useful hints on how to cluster words to form a meaningful sentence. Hence Chinese philology has no notion of syntax as a prescriptive spatiotemporal-logical grid of words. So it is only natural that traditional Chinese scholars would not seek to probe the inner workings of poetic vision through syntactic analysis.

The neglect of syntactic analysis is highly regrettable. Poetic vision is an intense mental experience induced by words and images cast in an extraordinary order. An examination of poetic syntax, therefore, is crucial to any attempt to illuminate the inner workings of poetic vision. Since the publication of Ma Jianzhong’s (1845–1900) Ma shi wen tong (Mr. Ma’s Grammar) in 1898, Chinese linguists have worked assiduously to construct a syntax-based Chinese grammar. Thanks to their endeavors, we now have a good enough knowledge of Chinese syntax for investigating the linguistic foundation for ineffable poetic vision. Here, by integrating the traditional jufa studies with modern syntactic analysis, I shall outline the evolution of Chinese poetic rhythms and syntax and assess their efficacy in evoking poetic visions.4

TWO BASIC SYNTACTIC CONSTRUCTIONS: SUBJECT + PREDICATE AND TOPIC + COMMENT

In common as well as poetic speech, Chinese words are organized into sentences according to two competing yet complementary principles: spatiotemporal-logical and analogical-associational.

If organized according to the first principle, words exhibit a partial or complete subject + predicate construction. The subject + predicate construction consists of an agent (subject) and the agent’s state or action (predicate) that may or may not involve a recipient (object). A complete subject + predicate construction enacts or implies a temporal-causal sequence from an agent to its action and to the action’s recipient. In English and other Western languages, this construction is the primary framework for both poetic and common speech. But in Chinese, this construction is far less important or pervasive than in English. In poetry in particular, it is merely one—sometimes the lesser—of the two ways that words are organized.

It should be noted that a typical Chinese subject + predicate construction is far less restrictive than its English counterpart. Neither subject nor predicate is fixed in time and space, as they are in Western languages by inflectional tags for tense, case, number, gender, and other aspects. Thus the reader has to contextualize, with or without the aid of grammatical function words. This process of contextualization compels the Chinese reader to intensely engage with depicted realities and feel as though they were really unfolding right before his eyes. This rich poetic potential of Chinese subject + predicate construction, made possible by the absence of inflection, has not gone unnoticed by Western critics. It was singled out by two prominent American critics, Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) and Ezra Pound (1885–1972), to support their assertions about the superiority of Chinese as a medium for poetry.5

The other syntactic construction is called topic + comment by scholars of Chinese language.6 Instead of an active agent responsible for an action or a condition, the “topic” refers to an object, a scene, or an event “passively” being observed. The “comment” refers to an implied observer’s response to the topic. As a rule, the response tells us more about the observer’s state of mind than about the topic. The absence of a predicative verb between the topic and the comment aptly underscores their relationship as noncontiguous and noncausal. The noncontiguous topic and comment are yoked together by the implied observer through analogy or association, in a moment of intense observation. The result is quite different from that of a temporal cognitive process. Topic + comment tends to reactivate the vortex of images and feelings, previously experienced by the observer, in the mind of the reader. Given its extraordinary evocative power, it is no surprise that this construction has been preferred for lyrical expression since the time of the Shijing (The Book of Poetry).

THE EVOLUTION OF CHINESE POETIC RHYTHMS AND SYNTAX

As shown in the preceding seventeen chapters, the birth of each major poetic genre or subgenre was marked by the formation of one or more distinctive semantic rhythms. The emergence of new semantic rhythms, in turn, led to a reconfiguration of both subject + predicate and topic + comment constructions. What follows is a brief outline of the most important reconfigurations of these two constructions over the millennia.

Tetrasyllabic Shi Poetry

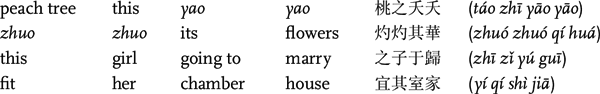

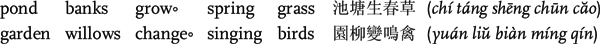

We begin with the semantic rhythm and syntactic constructions of early tetrasyllabic shi poetry. As shown in chapter 1, the Book of Poetry is made up largely of poems composed in tetrasyllabic lines. A tetrasyllabic line almost uniformly consists of two disyllabic segments. So 2 + 2 becomes the distinctive semantic rhythm of tetrasyllabic shi poetry. Depending on the words chosen, this 2 + 2 rhythm enacts either a subject + predicate or a topic + comment construction:

In this stanza from “The Peach Tree Tender” (C1.2), lines 3 and 4 each constitute a subject + predicate construction. Line 3 introduces a complete declarative statement (“This girl is going to be married”) and line 4 a truncated one, with the subject omitted (“fit for her chamber and house”). Lines 1 and 2 each introduce a topic + comment construction. In line 1, the “peach tree” marks the topic of attention, while “yaoyao,” a reduplicative (lianmian zi), constitutes the comment on the peach tree by the perceiver. Line 2 displays the same structure even though the comment (zhuozhuo) is placed before the topic (peach flowers).

Lines 1 and 2 exhibit the distinctive features of the originative topic + comment construction in the Book of Poetry. It typically yokes together two disparate segments—an external object and an inward response—without any connective. It is also marked by a prodigious use of reduplicatives as the comment. While English reduplicatives are usually onomatopoeic (for example, “hush-hush” and “ticktock”) and sometimes conceptual as well (for example, “hanky-panky” and “helter-skelter”), reduplicatives in the Book of Poetry primarily express a perceiver’s emotional response to external phenomena by translating it into alliterative and rhyming sounds untainted by conceptualization. This emotive use of reduplicatives has had a lasting impact on Chinese poetry.

Sao Poetry

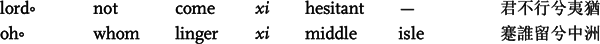

The Chuci (Lyrics of Chu) furnishes us with the first instance of a significant remolding of the topic + comment construction. The basic rhythm of early Chuci works is 3 + 2. As shown in the following excerpt, the initial trisyllabic segment is made up of a monosyllabic word and a binome and entails a minor pause (as indicated by ◦). Thus the semantic rhythm may be detailed as (1 + 2 or 2 + 1) + 2. The total number of 5, however, should not be confused with the actual character count of a line. A line of an early Chuci work contains one pause-indicating character, xi, placed in the middle (after the third word). This 3 + 2 rhythm gives rise, in most cases, to a topic + comment construction:

These opening lines of “The Lord of the Xiang River” (C2.1) are clearly topic + comment, with the trisyllabic segment as the topic and the disyllabic segment as the comment. Although line 4 seems like subject + predicate, it should also be taken as topic + comment. The long pause created by xi makes the “cassia boat” more an afterthought than the object of the verb “ride.” A comparison of these topic + comment constructions with those in the Book of Poetry reveals two important changes, which ironically seem to weaken the evocative power of the topic + comment.

The first change is the addition of an extra character to the topic. This extra character creates an imbalance between topic and comment. In all these lines, the topic expands from a simple object (as in the Book of Poetry) to a self-contained syntactic construction: a mini subject + predicate in lines l and 2 (“The lord would not come”; “Oh for whom are you lingering?”), a mini topic + comment in line 3 (“You, lovely” [yao miao, an assonant reduplicative]), and again a mini subject + predicate in line 4 (“Quickly I ride”). This expansion makes the trisyllabic segment a site of concentrated emotional expression in and of itself.

The second change is the insertion of the pause indicator xi between the topic and the comment. This pause provides a sense of closure to the topic and, in effect, reduces the ensuing comment to an afterthought. The weakening of the comment is also reflected in its shift from emotional response to pure supplemental information, as shown in line 2 (“middle isle”). As a weakened comment or simply an appendage, the disyllabic segment of a typical early Chuci line can often be omitted without impairing a line’s meaning. In “The Lord of the Xiang River,” for instance, all the lines would still be perfectly coherent without the disyllabic segments. In terms of aesthetic effect, however, these disyllabic segments are indispensable because they help to create the quick and powerful rhythm of a shaman chant and dance and amplify emotional expression.

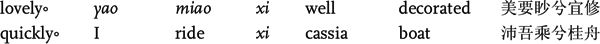

In later Chuci works, represented by “On Encountering Trouble” (C2.3), the pause indicator xi is repositioned, as shown in the following excerpt, to the end of the first line of a couplet. This may seem an insignificant move, but it actually brings about a profound change in both rhythm and syntax.

Having from birth this inward beauty,

10 I added to it fair outward adornment:

I dressed in selinea and shady angelica,

And twined autumn orchids to make a garland.

Swiftly I sped as in fearful pursuit,

Afraid that time would race on and leave me behind.

15 In the morning I gathered the angelica on the mountains,

In the evening I plucked the sedges of the islets.

The days and months hurried on, never delaying,

Springs and autumns sped by in endless alternation.

I thought how the trees and flowers were fading and falling,

20 And feared that my Fairest’s beauty would fade too.

[CCBZ, 3–47]

As shown in the word-for-word translation, the pause indicator xi has yielded the middle position to a connective—yi (to, in order to), yu (and), zhi (of), qi (a word linking subject and predicate), yu (in), and so on. This creates a new rhythm, 3 + 1 + 2, and makes the lines genuinely hexasyllabic. This new rhythm is slower and less powerful than that of early Chuci works and seems to reflect a shift from shamanistic performance to a narrative-descriptive presentation.

The substitution of syntactic connectives for xi brings about a dramatic change of syntax. As noted earlier, xi produces a long pause and effectively breaks a line into two distinct parts (a trisyllabic topic and a disyllabic comment). By contrast, these syntactic connectives combine the trisyllabic and disyllabic segments into one uninterrupted line. If a xi-separated line is by default a topic + comment construction, such a connective-linked line is almost invariably a subject + predicate construction. A notable exception is where an extended noun phrase takes up an entire line (line 1).

The syntactic role of the disyllabic segment is determined by the connective that precedes it. As shown in the excerpt, the connective zhi, roughly equivalent to “’s” in English, introduces the disyllabic segment as the object of a transitive verb (lines 15–16 and 19–20). The connective qi normally introduces the disyllabic segment as the main verb while making the preceding trisyllabic segment the subject (lines 17–18). The connective yi, equivalent to “in order to” in English, almost always introduces an auxiliary clause of purpose (lines 10 and 12). The list of connectives used in Chuci lines is quite short, and they tend to recur very frequently in a long poem like “On Encountering Trouble.” While these connectives each help to form a particular kind of subject + predicate, they share one feature: they produce strictly linear one-directional sentences and do not allow an inversion of the subject + predicate order. This undoubtedly contributes to the building of a forward momentum highly desirable for an extended narration or description. It is perhaps for this reason that these sao-style lines are heavily used not only in the Chuci but also in the fu poetry of later times.

Fu Poetry

The fu genre features two dominant rhythms, 2 + 2 and 3 + 1 + 2, inherited from the Book of Poetry and Lyrics of Chu, respectively. The preponderance of these two rhythms in the Han fu corpus should not surprise us, as the rise of the fu genre has been widely attributed to the influence of those two ancient collections. Some fu works, like “Fu on the Imperial Park” (C3.1), by Sima Xiangru (179–117 B.C.E.), extensively use the 2 + 2 Shijing rhythm along with a secondary Chuci rhythm of 3 + 1 + 2. Other Han fu works feature a parallel use of these two rhythms. These poems seem entitled to the appellation of “four and six” given to “parallel prose” (pianwen), a prose characterized by alternating tetrasyllabic and hexasyllabic lines. In fact, they are often called parallel fu because of their likeness to parallel prose. There is nothing particularly innovative about Han fu writers’ employment of the 2 + 2 and 3 + 1 + 2 rhythms. A noteworthy change is the tendency to use a long succession of 2 + 2 lines to enumerate objects and things and then depict their conditions or actions. In “Fu on the Imperial Park,” for instance, we see again and again an exuberant catalog of splendid objects and things (lines 96–100, 202–208, and so on), followed by an equally exhaustive description of their appearance and motions (lines 101–107, 209–218, and so on).

Pentasyllabic Shi Poetry

Pentasyllabic shi poetry ushers in a 2 + 3 rhythm seldom consciously employed before the Later Han. Once firmly established, this new rhythm quickly gained popularity and became the core rhythm for all major shi subgenres developed since the Later Han. Having already given a technical analysis of this rhythm in chapter 5, I shall examine here how it enabled Six Dynasties and Tang poets to remold both subject + predicate and topic + comment constructions. Let us begin with a famous couplet from “Climbing the Lakeside Tower” (C6.7), by Xie Lingyun (385–433):

The 2 + 3 rhythm of this couplet may seem at first sight an insignificant reversal of the 3 + 2 Chuci rhythm. In reality, the significance of this transposition cannot be overstated. After the middle-positioned xi (or any other connective) is eliminated and the trisyllabic segment swaps position with the disyllabic segment, the top-heavy imbalance of the 3 + 2 Chuci rhythm is corrected. What arises is a balanced, dynamic rhythm of 2 + 1 + 2 or, alternatively, 2 + 2 + 1. In this new rhythm, the odd 1 is no longer confined to the trisyllabic segment (as in the Chuci 3 + 2 line) and, in fact, becomes the pivot for the entire line, engaging its two segments in a dynamic interplay.

The rhythm of Xie Lingyun’s couplet is 2 + 1 + 2. The initial 2 and ending 2 are noun binomes in both lines, and the odd 1 is a verb in both. Seeing this succession of noun + verb + noun, we, conditioned by our habitual manner of reading, almost automatically read the couplet as subject + predicate with two direct objects: “Pond banks giving birth to spring grass, / Garden willows change into the singing birds.” Our sense of logic, however, immediately makes us realize that the two verbs depict the poet’s imaginative perception rather than real phenomena of nature.

This leads us to see a genuine topic + comment construction underlying what we may call a pseudo subject + predicate. “Pond banks” and “spring grass,” and “garden willows” and “singing birds” are the twin topics. The verbs, “grow” and “change,” placed between them are the comments. The two comments reveal the poet’s perceptual illusion resulting from a dramatic condensation of time in his reverie-like perception. Condensing months of gradual seasonal changes (the grass’s growth and the birds’ return) into a startling moment of change, Xie Lingyun entertains the illusion of the pond banks giving birth to green grass and the garden willows changing into singing birds. As we reexperience Xie Lingyun’s imaginative transformation of physical realities, we cannot but share the poet’s sense of delight and wonder at the sudden advent of spring. Moreover, this montage of disparate images—barren pond banks with green grass, (implied) leafless willow gardens with singing birds—brings forth a cosmic vision, one characterized by perpetual growth and change. Indeed, the comments “grow” and “change” are none other than the twin cardinal cosmic principles expounded in the Book of Changes: “To grow and grow is called the Changes” and “[The alternation of] one yin and one yang is called the Dao.”7

Xie Lingyun’s construction of this famous couplet presages how Tang poets, especially the High Tang masters, would exploit the expressive potential of the 2 + 3 rhythm in pentasyllabic poetry. Like Xie Lingyun, they would spare no effort to utilize syntactic ambiguities to conflate a pseudo subject + predicate and a genuine topic + comment. They focus, too, on exploiting what is often called the verse eye—an animating and often logically impossible verb that engenders, as in Xie Lingyun’s couplet, an enchanting perceptual illusion.

Tang regulated verse presents us with topic + comment constructions of varying degrees of complexity. Du Fu’s poem “The Jiang and Han Rivers” (C8.2) features a relatively simple topic + comment construction in which the topic (disyllabic segment) is a noun binome depicting a broad scene and the comment (trisyllabic segment) is a mini subject + predicate depicting the poet’s physical and emotional conditions. As I have already discussed the aesthetic effect of this construction in that poem in chapter 8, let me consider a complex twin topic + comment construction, in which both the topic and the comment are mini subject + predicate constructions:

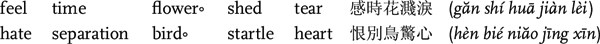

In this famous couplet from Du Fu’s “Spring Scene” (C8.1), each line contains two subjects: an implied subject (who “feels time” and “hates separation”) in the initial disyllabic segment and an explicit nonhuman subject (that “sheds tears” and “startles heart”) in the ensuing trisyllabic segment. As I have explained in chapter 8, the omission of the first subject gives rise to a syntactic ambiguity that allows for four different readings of the couplet (see pp. 165–167). This couplet also invites a fifth reading as a complex topic + comment:

Feeling time—flowers shed tears,

Hating separation—a bird startles the heart.

This reading is contingent on a deliberately prolonged pause (as indicated by the dashes) that breaks the spatiotemporal-logical link between the disyllabic and trisyllabic segments. When so separated, the disyllabic segments (“feeling time” and “hating separation”) become the topics being contemplated by the poet; and the trisyllabic segments (“flowers shed tears” and “a bird startles the heart”) become the poet’s comments on his own emotional state. These comments may be taken as flashes of mental images in the poet’s mind that reveal his otherwise indescribable feelings. Indeed, they enable us to reexperience the montage-like leaps of his mind during his intense self-reflection.

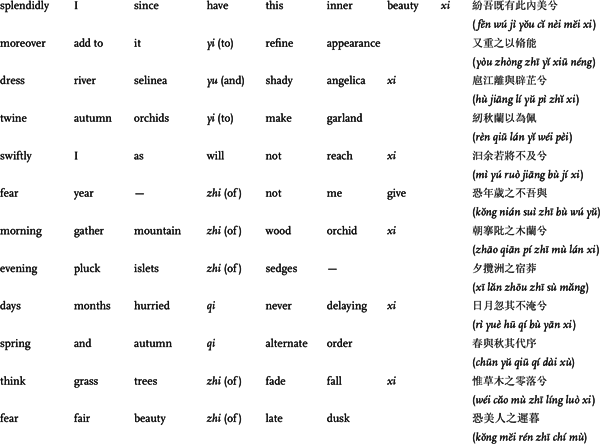

Heptasyllabic Shi Poetry

“Upper 4 and lower 3” (shang si xia san) is the phrase frequently used by traditional Chinese critics to characterize the rhythm of heptasyllabic poetry. In traditional Chinese writing, words are arranged vertically from top to bottom and lines from right to left on a page. So “upper 4” denotes the initial tetrasyllabic segment and “lower 3” the ensuing trisyllabic segment. Together the two segments form a 4 + 3 rhythm. To many modern critics, however, 2 + 2 + 3 is a preferable description of this rhythm because it better reveals heptasyllabic poetry’s inherent bond with, if not genesis in, pentasyllabic poetry, whose rhythm is 2 + 3. Wang Li, for example, considers a heptasyllabic line as essentially a two-character extension of a pentasyllabic line. So he classifies heptasyllabic lines into seven major types, according to the parts of speech and positioning of the two additional characters.8

In my view, the 4 + 3 and 2 + 2 + 3 rhythms are not one and the same, as commonly believed, but represent two distinct rhythms of heptasyllabic poetry. As I shall demonstrate in the following, they co-arise with different kinds of syntax and produce very different aesthetic effects.

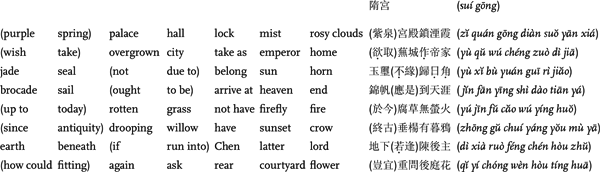

The 2 + 2 + 3 rhythm consists of a core 2 + 3 rhythm plus an auxiliary 2. Of the first four characters, which two are to be considered auxiliary could sometimes be a rather arbitrary decision. Yet a simple rule seems to work well in most cases: the auxiliary 2 should be the two characters that could be taken out with the least impact on a line’s meaning. Applying this rule, we can easily identify the auxiliary 2 in each line of the following poem by Li Shangyin (813–858):

Purple Spring’s palace halls lay locked in the twilight mist;

2 He wished to make the Overgrown City a home of emperors.

The jade seal: if it had not somehow become the Sun-horn’s,

4 Brocade sails, then, would have reached heaven’s end.

To this day the rotten grass is without fireflies’ flash,

6 From antiquity lie the drooping willows, with the sunset crows.

Beneath the earth, if he would run into the Latter Lord of Chen,

8 How could it be fitting to ask about “Rear Courtyard Flowers”?

[QTS 16:539.6161; also translated and discussed under C9.6]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 172]

The auxiliary 2, as shown by the parentheses, appears at the beginning or in the middle of a line, giving rise to two distinct patterns: (2) + 2 + 3 and 2 + (2) + 3. Without the auxiliary 2, this poem would be essentially a jumble of descriptive fragments relating to the Sui emperor Yang (Yang Guang, 569–618). With the auxiliary 2, the poet manages to construct two mutually intertwined frameworks of contrast—between past and present and between reality and imagination—within which all the fragments coalesce into a whole.

Now let us see how the auxiliary 2 brings about this magical transformation. In the first couplet, the auxiliary 2 is made up of a noun and a modal phrase. In line 1, “Purple Spring,” a river in the Chang’an area, makes it clear that the palace in an abandoned state (“lay locked in the twilight mist’) is the official Sui Palace in the capital city of Chang’an. In line 2, the modal phrase “wished to make” reveals the reason for the abandoned state of that palace: Emperor Yang “wished to make the Overgrown City a home of emperors.” “Overgrown City” refers to Guangling, present-day Yangzhou on the Yangtze; “home of emperors” is a reference to the resort palace built in the Overgrown City for his excursions to the Yangtze region. Thanks to the auxiliary 2, the poet turns the otherwise objective depiction of the two palaces into an indictment against Emperor Yang. His extravagance knew no end: the grand capital palace was not enough for him, and he had others built for him far away from the capital. His abandonment of the capital palace in favor of his resort palace attested to his wanton neglect of state affairs.

In the second couplet, the auxiliary 2 features a pair of conjunctions that knit two lines into a complex subject + predicate. The first conjunction, “if … not [for certain reasons],” introduces a past subjunctive conditional clause: “The jade seal: if it had not somehow become the Sun-horn’s.” In traditional Chinese physiognomy, “sun-horn” denotes the hornlike protrusion on the forehead of someone who is or is destined to be an emperor. Here “Sun-horn” specifically refers to Li Shimin (Emperor Taizong of the Tang, 600–649), who overthrew the Sui and founded the Tang dynasty. The second conjunction, “ought to be,” helps to construct a past subjunctive result clause: “Brocade sails, then, would have reached heaven’s end.” “Brocade sails” refers to the huge pleasure boat used by Emperor Yang in his excursions to the Yangtze region. While the conditional clause tells of Emperor Yang’s dethronement by Li Shimin, the result clause reveals its cause—his inordinate pursuit of pleasure. This complex subject + predicate also invites a different reading, with Emperor Yang as the speaker. In that case, we would imagine that in the underworld (anticipating the last couplet) Emperor Yang was ruefully saying that if he had not lost his empire to Li Shimin, his pleasure boat would have reached to heaven’s end. Whether read in the voice of the poet or that of Emperor Yang, these two lines unmistakably deliver a scathing mockery of the debauchery and extreme folly of this dethroned emperor.

In the third couplet, the auxiliary 2 rounds out the subject + predicate by supplying adverbials of time. The two adverbials are intended to link past and present. In line 5, “to this day” links the present dearth of fireflies to a tale of the past: Emperor Yang ordered that all fireflies be caught to light lanterns for his nighttime pleasure trips. Conversely, “from antiquity” in line 6 traces the present sight of old willow trees back to the time when they were planted along the Grand Canal by order of Emperor Yang. It also reminds us of the story that Emperor Yang renamed his favorite tree, willow, as “Yang willow” after his own surname. What now remains of these once-glorious trees are inauspicious crows perched in them. Thanks to the two adverbials, this couplet yields a double vision of present desolation (old trees, crows, and sunset) and bygone imperial extravagance (nighttime excursion and pleasure boats on the willow-flanked canal). By juxtaposing these two worlds, the poet amplifies his mockery of the emperor’s foolish, self-destructive pursuit of pleasure.

In the last couplet, the auxiliary 2 once again combines two lines into a complex subject + predicate. In line 7, “if he would run into” ushers in yet another subjunctive clause, “Beneath the earth, if he would run into the Latter Lord Chen,” while “how could it be fitting” turns line 8 into a rhetorical question. This subjunctive clause, like that in the second couplet, leads us into the realm of imagination. The imagined meeting between the two emperors is an ingenious play of irony. Lord Chen, notorious for his debauchery, was the last emperor of the Chen dynasty. The new companion he might meet in the underworld is none other than Emperor Yang, who defeated and overthrew his empire. Here the reader may fancy seeing Lord Chen gleefully saying to himself upon this meeting: “My conqueror now lost his empire for exactly the same sins that had led to my own downfall.” This play of irony continues in the next line: “How could it be fitting to ask about ‘Rear Courtyard Flowers’?” “Rear Courtyard Flowers,” a song composed by Lord Chen, is a well-established symbol for extravagance and debauchery. By raising this rhetorical question, the poet means to say that Emperor Yang, upon meeting Lord Chen, would nonetheless consult him on matters of corporeal gratification. This, then, shows that Emperor Yang was totally oblivious to the irony of his fate and completely beyond repentance. Even though in life he could not sail his pleasure boat to “heaven’s end,” he was obviously determined to do so in the underworld. With this poignant rhetorical question, the poet brings his ridicule of Emperor Yang to a climax.

Our reading of “Sui Palace” shows that the auxiliary 2 is anything but auxiliary as far as the entire poem is concerned. Although it is ancillary to the literal sense of an individual line, the auxiliary 2 is of pivotal importance in the construction of complex subject + predicate sentences in the poem. Without the help of these sentences, Li Shangyin could not have moved so smoothly between past and present, between reality and fiction, and, in the process, blended narration and commentary into an enchanting vision of history.

In my view, the other heptasyllabic rhythm, 4 + 3, should be reserved solely for describing lines in which the tetrasyllabic segment is self-cohesive and detachable from the trisyllabic segment. This line configuration strikes us as an expanded version of the 3 (+ xi) + 2 lines of early Chuci works. Indeed, it, too, produces a top-heavy dynamic in both sound and sense. The combination of two self-cohesive segments necessitates a relatively longer pause in between than the one that exists between 2 + 2 and 3. Certainly this pause is not as long as that created by the pause indicator xi in a Chuci line. Yet it seems sufficient to produce a similar impact on the syntax: breaking the line into an initial main and an ensuing supplementary part. The following poem, composed almost entirely of 4 + 3 lines, displays this bipartite syntax:

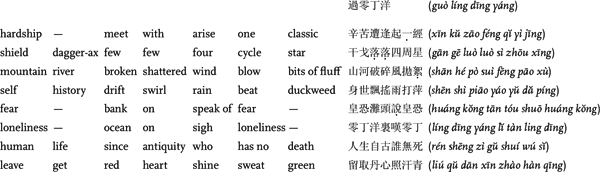

Crossing the Sea of Loneliness

All the hardships I’ve encountered—they began with one classic;

2 Shields and dagger-axes have grown few and far between—four cycles of stars.

Rivers and mountains are shattered—bits of fluff blown in the wind;

4 My life drifts and swirls—patches of duckweed beaten by the rain.

Along the Bank of Fears I told of fears,

6 On the Sea of Loneliness I sighed over loneliness.

Whose life, ever since antiquity, is without death?

8 Let my loyal heart shine on the bamboo tablets!

[QSS 68:3598.43025]

[Tonal pattern IIa, see p. 172]

This poem was written by Wen Tianxiang (1236–1283), a Song loyalist who bravely fought against the Mongols and died a martyr’s death. The poem begins with an unusual series of four topic + comment lines. As shown by the dashes, the two parts of lines 1–4 are not spatiotemporally or logically linked and must be understood in terms of topics and comments. Moving down the tetrasyllabic column, we see the changing topics of the poet’s deepening reflection: his career path, his recent military action, the country’s present condition, and his present condition. As the topics move from past to present, the poet’s comments (the trisyllabic column) become more and more emotionally charged. The first comment, “they began with one classic,” is largely explanatory. It tells us that his career began with his study of the Confucian classics. The other three comments enact a montage-like leap to a concrete image. In line 2, “four cycles of stars” primarily denotes the span of four years during which Wen Tianxiang ceaselessly waged battles against the Mongols despite the vanishing of military resistance across the country. It also carries a spatial connotation—the starlit sky above the deserted battlegrounds. In line 3, “bits of fluff blown in the wind” turns the topic, the country’s destruction, into a heartrending image. The weighty “rivers and mountains” (a metaphor for the country) are now turned into soft, weightless “bits of fluff” irretrievably blown away. In line 4, “patches of duckweed beaten by the rain” works in the same fashion; it changes the topic, the rise and fall of the poet, into a pathetic image of a rootless, constantly battered plant.

The second half of the poem exhibits a change to subject + predicate constructions. The tetrasyllabic and trisyllabic segments of all four lines are merged to form declarative statements. Lines 5–7 are simple subject + predicate lines, but the last line is a complex twin subject + predicate. In lines 5 and 6, the tetrasyllabic segments are extended adverbials of place, while the trisyllabic segments are the core subject (implied) + predicate. When an adverbial is extended from two (as in pentasyllabic poetry) to four words, it becomes the focus of a line. This foregrounding of adverbials works perfectly at this juncture of the poem. The “Bank of Fears,” on the Gan River in the southern province of Jiangxi, is a place Wen Tianxiang passed through in 1277 in a hasty retreat after losing a battle to the Mongols. So the poet is not speaking about the present but reminiscing about his recent telling of fear in that place named Fears. The next adverbial, however, brings the time frame to the present. The “Sea of Loneliness” is none other than the bay Wen Tianxiang was crossing when writing the poem two years later. Once again, the emotive import of a place-name amazingly coincides with what the poet was feeling in that place. Being escorted back to northern China by the Mongols as a trophy of their complete conquest of China, the poet felt the extreme pain of humiliation and loneliness. The ending couplet marks a dramatic turning in the poet’s mood. The sublimation of his sorrow into heroic defiance is achieved through an impassioned contemplation on life’s meaning. Line 7 advances the premise, “Whose life, ever since antiquity, is without death?” and line 8 presents the conclusion: “Let my loyal heart shine on the bamboo tablets [history books]!” Ever since the poet’s death, this couplet has become probably the best-known Chinese motto for heroic action and sacrifice. To this day, Wen Tianxiang is remembered and admired by millions of Chinese for this great couplet as well as for his heroic action.

My analysis of the two heptasyllabic poems reveals an inherent relationship between the two heptasyllabic rhythms and certain syntactic constructions. The 2 + 2 + 3 rhythm usually co-arises with a single but fully developed subject + predicate, often complete with adverbials of time or place. This rhythm is not particularly conducive to and, in fact, not frequently used for the construction of a topic + comment line. For instance, there is none in Li Shangyin’s “Sui Palace.” Conversely, the 4 + 3 rhythm often goes with a complex twin subject + predicate. Only when the tetrasyllabic segment is an extended adverbial or nominal phrase do we see a simple subject + predicate in 4 + 3 lines. Thanks to the long pause between its tetrasyllabic and trisyllabic segments, a 4 + 3 line also readily lends itself to the topic + comment construction. As just shown, half of Wen Tianxiang’s “Crossing the Sea of Loneliness” is made up of topic + comment lines.

Ci Poetry

The dominance of the shi rhythms (2 + 3, 2 + 2 + 3, and 4 + 3) remained unchallenged until the rise of ci poetry during the Late Tang and the Song. Unlike the sao, fu, and shi genres, ci poetry does not exhibit an overall uniform semantic rhythm. Each of the roughly four hundred major ci tunes has its own fixed combination of lines (mostly irregular) and employs a unique set of semantic rhythms. This absence of uniformity enabled ci poets to be far more innovative than practitioners of other genres in the use of semantic rhythms. Of the many new features of ci rhythms, two are most noteworthy: the ingenious use of existent shi rhythms and the creation of radically new ones.

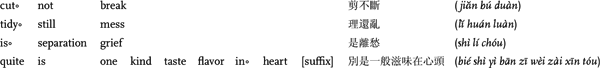

The most ingenious use of shi rhythms was the creation of a multiline syntactic construction scarcely used in earlier poetic genres. Lines 4–7 from “To the Tune ‘Crows Call at Night’” (C12.1), by Li Yu (937–978), are a good example of this novel construction:

4 Cut, it doesn’t break,

Tidied, a mess again—

6 [This] is separation grief.

[This] is altogether a different kind of flavor in the heart.

[QTWDC 4.450]

These four lines employ shi rhythms: the trisyllabic 1 + 2 in the first three lines and the heptasyllabic 4 + 3, with an additional disyllabic segment, in the fourth line. Although each line is a mini subject + predicate, none functions independently. Instead, the lines work together to form an extended subject + predicate construction. The first two lines constitute the subject, while the next two are its twin predicates. This subject + predicate relationship is clearly underscored by the verb “is” (shi) in lines 6 and 7. Interestingly, the word shi in line 6 can also be glossed as the demonstrative pronoun “this,” thus instead presenting us with a multiline topic + comment construction. In this reading, the first two lines are the topic; the third line, the comment; and the fourth line, a further amplification of the comment.

The breakup of a long sentence into multiple lines is often similar to enjambment in Western poetry. Like enjambment, a multiline subject + predicate or topic + comment construction attempts to subvert the established alignment between line and completion of a syntactic construction. Often, especially where “leading words” (lingzi) are employed, a line ends abruptly in the middle of a sentence in order to achieve a special effect (for instance, “Meditation on the Past at Red Cliff” [C13.3], lines 3 and 13). The two multiline constructions represent a revolutionary break from poetic tradition. All earlier poetic genres and subgenres, including the irregular-line yuefu, almost uniformly feature end-stopped lines. Typically, an end-stopped line is paired with another to form a couplet—a larger unit with a stronger sense of closure. A multiplication of couplets, in turn, brings an entire poem to completion. While these principles of line formation are faithfully observed in shi, sao, and fu poetry, they are anything but sacred in ci poetry. In availing themselves of typical shi lines (trisyllabic, tetrasyllabic, pentasyllabic, and/or heptasyllabic), ci poets often did what Li Yu did in “To the Tune ‘Crows Call at Night’”—breaking away from the habit of coupling and composing sentences that extend over three or more lines.

Apart from their use of existent shi lines, ci poets created two new line types: the monosyllabic and the disyllabic.9 Obviously, the scarcity of monosyllabic and disyllabic lines in earlier genres has much to do with the entrenched practice of making each line a complete subject + predicate or topic + comment construction. Monosyllabic and disyllabic lines are simply too short for either. Once ci poets had freed themselves from this practice, it was only natural for them to make prodigious use of monosyllabic and disyllabic lines, placing them in the pivotal position of a poem.

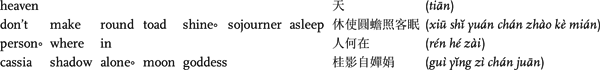

To the Tune “Sixteen-Character Song”

Heaven—

don’t let the moon shine upon the sojourner!

Where is the loved one?

[Under] the shadow of the cassia tree, alone watching the moon goddess.

[QSC 2:1030]

This short poem, by Cai Shen (1088–1156), exhibits a radically lopsided topic + comment construction. The monosyllabic line “Heaven” constitutes the topic, the pivotal point of the entire poem. The remainder is, in effect, a series of amplifying comments by the implied observer. First, he addresses heaven, asking it to prevent the “round toad,” a Chinese mythical metaphor for the moon, from shining on him, the lonesome sojourner. This apostrophe is followed by his brief monologue: “Where is the loved one? / Under the shadow of the cassia tree [another mythical metaphor for the moon], alone watching the moon goddess.” There seems to be a deliberate ambiguity with regard to who is (are) watching the moon goddess: the subject could be “I,” “she,” or “we each.” Calculatedly lopsided, this topic + comment construction produces a maximum effect of novelty and amplification.

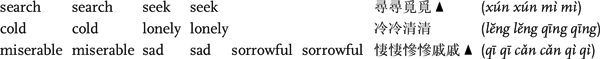

A doubling or tripling of monosyllabic or disyllabic segments is often used to increase the intensity of emotional expression. Consider, for instance, these powerful opening lines of the famous poem “To the Tune ‘One Beat Followed by Another, a Long Tune’” (C13.4), by Li Qingzhao (1084–1151):

The poem begins with a doubling of reduplicatives with long vowels—xu xu, mi mi (line 1) and leng leng, qing qing (line 2)—immediately followed by a tripling of reduplicatives in line 3 (qi qi, can can, qi qi). This creates an unprecedentedly prolonged rhythm of 2 + 2; 2 + 2 / 2 + 2 + 2 or simply 2 +2 +2 +2 +2 +2 + 2. This drawn-out rhythm effectively translates the poet’s unending sorrow and yearning into an intense aural experience. The tripling of reduplicatives in line 3 is particularly noteworthy. Such a tripling of reduplicatives, and, for that matter, any semantic or syntactic unit, was rarely seen in earlier poetry. A sudden, prodigious use of it in ci poetry seems to have been calculated to challenge the doubling tendency prominent in all earlier poetic genres.

Qu Poetry

The Yuan sanqu corpus has about 160 established tunes, of which 50 or so are frequently used. Many of these tunes display semantic rhythms similar to those of short ci poems (xiaoling). It seems no coincidence that all stand-alone sanqu tunes (as opposed to those in a song suite [santao]) are called xiaoling as well. Working with similar semantic rhythms, sanqu poets nevertheless created new syntactic constructions of their own. The following two examples show how two radically different topic + comment constructions were fashioned out of the same tune.

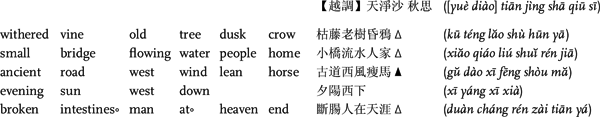

To the Tune “Sky-Clear Sand” [yuediao key]: Autumn Thoughts

Withered vines, old trees, crows at dusk,

2 A small bridge, flowing water, people’s homes,

An ancient road, the west wind, a lean horse.

4 The evening sun goes down in the west.

One heartbroken man at the end of the earth.

[QYSQ 1:242]

As shown by the word-for-word translation, this poem by Ma Zhiyuan (1250?–1323?) bears much formal resemblance to the excerpt of Li Qingzhao’s poem “To the Tune ‘One Beat Followed by Another, a Long Tune’” (C13.4). It also makes an extensive use of tripling. Lines 1–3 constitute a tripling of hexasyllabic lines, and each line, in turn, a tripling of binomes. Thus we have a string of ten binomes (nine in lines 1–3 plus one in line 4). This produces an even more prolonged rhythm of 2 + 2 + 2 … than in Li Qingzhao’s poem. The aesthetic effect, however, is just the opposite. In Li Qingzhao’s poem, all the disyllabic segments are emotionally charged reduplicatives. Their rapid succession hastens the tempo and enhances the intensity of emotional expression. In Ma Zhiyuan’s poem, however, all of the ten binomes are nouns for objects or scenes. Placed in succession, they suggest slowly shifting views of a traveler on the move. First, he catches sight of “withered vines” along the ancient path. Following the vines upward, he sees an old tree and the crow perched in it. Next, a “small bridge” comes into his view, with the brook meandering and leading his gaze to the village homes afar. Finally, the village is left behind, and the ancient path appears again—a “lean horse” and traveler trudge into the sunset. All these images, static or devoid of forceful motion, suggest the slow pace of a grueling journey and the traveler’s sense of weariness. The flitting appearance of a pleasant village scene serves only to set off the unending desolation and sorrow faced by the traveler. In terms of syntax, the ten binomes constitute multiple topics of observation, while the final line is the speaker’s comment on all these topics. This top-heavy topic + comment strikes us as the reverse of what we saw in Cai Shen’s “To the Tune ‘Sixteen-Character Song.’” Whereas Cai Shen’s poem begins with one topic followed by multiple lines of comments, Ma Zhiyuan’s poem consists of ten topics placed in succession and only one line of comment at its end.

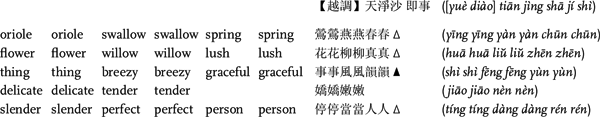

Out of the same tune, “Sky-Clear Sand,” Qiao Ji (1280–1345) fashioned an even more innovative topic + comment construction, one in which the comment has imperceptibly merged with the topic:

To the Tune “Sky-Clear Sand” [yuediao key]: Of This Occasion

[QYSQ 1:592]

Comparing “Of This Occasion” with “Autumn Thoughts,” we note two prominent differences in the handling of disyllabic segments. First, Qiao Ji’s poem is entirely made of disyllabic segments, while Ma Zhiyuan’s poem has two trisyllabic segments (3 + 3 beat) in the last line. The makeup of the disyllabic segments is also markedly different. Whereas the ten disyllabic segments in Ma Zhiyuan’s poem are all noun binomes, all fourteen disyllabic segments in this poem are reduplicatives.

These fourteen reduplicatives are of a kind rarely used in earlier poetry but quite frequently used by Qiao Ji and some other sanqu poets. Originally employed as comment in the originative Shijing topic + comment construction, reduplicatives were continually reinvented over the millennia as a prized means of emotional expression. In Li Qingzhao’s “To the Tune ‘One Beat Followed by Another, a Long Tune,’” all the reduplicatives are produced from established verbal and adjectival binomes. The making of such reduplicatives betrays a process opposite to the evolution of Shijing reduplicatives. Many, if not all, of the Shijing reduplicatives can be regarded as unmediated, “preconceptual” responses to external stimuli, and only over time did some of them become conceptualized as established adjectives or adverbs. By contrast, the making of new reduplicatives by Li Qingzhao speaks to a process of “deconceptualization”—that is, taking a binome apart and turning its two characters into reduplicatives to create a succession of rhythmic and emotionally expressive sounds. For instance, xumi (search for) becomes xu xu mi mi, and lengqing (cold and lonely) becomes leng leng qing qing.

With Qiao Ji, this process of deconceptualization became even more radical. To him, seemingly no part of speech was off-limits to deconstruction and deconceptualization. In “Of This Occasion,” he turns all the words—monosyllabic words (“oriole” and “person”), binomes (“delicate, tender”), adjectives (“vivid”), and nouns (“flower” and “willow”)—into reduplicatives. If the radical reduplication in this poem is undone, we can perceive a series of four topic + comment constructions:

Orioles and swallows—the spring,

Flowers and willow—vivid.

Things—graceful,

Delicate, tender.

Perfect—the person

The topics are two common objects of observation in Chinese poetry: the flora and fauna of springtime and a beautiful woman. Like earlier poets, Qiao Ji presented the two in juxtaposition for the best effect of mutual illumination. The blending of nature’s luster and a beauty’s radiance makes each ever more enchanting. The comments are fairly commonplace adjectives. Here Qiao Ji could have deconceptualized and turned these adjectives into reduplicatives, as Li Qingzhao did, while leaving the topics in their regular nominal form. The poem would then have assumed the form of the originative Shijing topic + comment. But this is not what Qiao Ji chose to do. To achieve a dramatic novel effect, he turned every single word, whether originally the topic or the comment, into a reduplicative. As the topics, too, become emotionally charged reduplicatives, they practically merge with the comments into one. Thus each word captures not only what the poet saw but also his delighted response to it. The extraordinary syntax of this poem shows how far the topic + comment construction evolved from its originative Shijing form.

In this brief chapter, I have been able to depict the evolution of Chinese poetic syntax and poetic vision in only the broadest strokes. The five major genres feature a much broader array of subject + predicate and topic + comment constructions than what has been presented here. An exhaustive investigation of the two syntactic constructions and their efficacy for embodying poetic vision must be left to a future book-length study. Nonetheless, I hope that this broad outline has provided enough to stimulate a meaningful discussion on this important topic.

NOTES

1. Zhong Rong, Shipin jizhu (Collected Annotations of the “Grading of Poets”), ed. Cao Xu (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1994), 36–39.

2. Liu Xizai, Yi gai (Essentials of the Arts) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1978), 69–71.

3. Consider, for instance, the distinction between yuefu or yuefu-style poetry (chaps. 4 and 11) and ci poetry (chaps. 12–14).

4. Yu-kung Kao was the first scholar to explore the possibility of analyzing Chinese poetry in terms of its use of these two syntactic constructions, in Zhongguo meidian yu wenxue yanjiu lunji (Studies of Chinese Aesthetics and Literature) (Taipei: Taiwan National University Press, 2004), especially 165–208.

5. Ernest Fenollosa, The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry, ed. Ezra Pound (San Francisco: City Lights, 1936).

6. Yuen Ren Chao, A Grammar of Spoken Chinese (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968), 69–72.

7. Xici zhuan (Commentary on the Appended Phrases), A4, A5, in Zhouyi yinde (A Concordance to “Yi ching”), Harvard-Yenching Institute Sinological Index Series, supplement no. 10 (Taipei: Chinese Materials and Research Aids Service Center, 1973), 40.

8. Wang Li, Hanyu shilü xue (Chinese Prosody) (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin jiaoyu chubanshe, 1979), 234–352.

9. Although a monosyllabic or disyllabic line appears occasionally in an irregular-line yuefu, sao, or fu poem, it is usually just an exclamatory utterance or a conjunction that has no substantive meaning in itself (for instance, “Fu on the Imperial Park” [C3.1], lines 74 and 79; “Song of the East Gate” [C4.5], line 19).

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Birch, Cyril, ed. Studies in Chinese Literary Genres. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

Chao, Yuen Ren. A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968.

Cheng, François. Chinese Poetic Writing. Translated by Donald A. Riggs and Jerome P. Seaton. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Lin, Shuen-fu, and Stephen Owen, eds. The Vitality of the Lyric Voice: Shih Poetry from the Late Han to the T’ang. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Liu, James J. Y. The Art of Chinese Poetry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Owen, Stephen. Traditional Chinese Poetry and Poetics: Omen of the World. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Yu, Pauline. The Reading of Imagery in the Chinese Poetic Tradition. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

CHINESE

Chou Fa-kao 周法高. Zhongguo gudai yufa gouci pian 中國古代語法構詞編 (A Historical Grammar of Ancient Chinese: Syntax). Academia Sinica, Special Publications, no. 39. Taipei: Institute of History and Philology, 1962.

Kao Yu-kung 高友工. Zhongguo meidian yu wenxue yanjiu lunji 中國美典與文學研究論集 (Studies of Chinese Aesthetics and Literature). Taipei: Taiwan National University Press, 2004.

Wang Li 王力. Han yu shigao 漢語史稿 (A Draft History of Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1980.

———. Hanyu shilü xue 漢語詩律學 (Chinese Prosody). Shanghai: Shanghai renmin jiaoyu chubanshe, 1979.