12

12

Beginning in the Tang dynasty (618–907), new music from Central Asia began entering China and soon became all the rage at the cosmopolitan Tang court and in Tang urban culture. From the lyrics set to this so-called banquet music (yanyue), there arose a new poetic genre, the ci (song lyric). Characterized by uneven line lengths and strictly determined rhyme and tone schemes, this genre developed into a major alternative to shi poetry during the Song dynasty, when it is traditionally thought to have reached its height.

Early song lyrics were associated with women and the entertainment quarters, where courtesans sang the popular new music. These female entertainers were well trained in poetry and music and enjoyed extensive social and literary interaction with intellectuals and poets. Courtesans often set to music and performed the works of well-known poets, but they also performed their own songs and exchanged poems with the literati in their circles. This “feminine” connection played an important role in setting the ci’s thematic range and made problematic its legitimacy as a genre for serious literary pursuit. It also makes the ci a particularly interesting genre from the point of view of feminism and gender studies.1 The predominance of feminine themes in early ci meant that a female courtesan might be found singing the female-voiced song of a male poet, whose work, in turn, drew on female voices in the tradition as well as on male imitations of those voices.

Although its lines may be uneven, the ci is far from free verse. The poems were written to hundreds of tune patterns, each of which strictly determined the number of characters per line, the placement of rhymes, and the position of tones. Originally the ci were actually sung to these tunes, but eventually the tunes themselves were lost, and all that remained were the hundreds of ci patterns with their many variations. To this day, one speaks of “filling in the words” to a song lyric (tian ci) according to the matrix associated with its tune title. The earliest ci poems evince a thematic relationship to their tune titles (for example, a poem to the tune “Willow Branch” is at some level about willows), but later ci are usually totally unrelated to the subject of the original tune.

Another name for the ci is chang duan ju (literally, long and short lines). The uneven lines of the ci are able to accommodate a larger number of colloquial elements and xuzi (function words [literally, empty words]) and tend to employ more continuous syntax than their shi counterparts. These long and short lines originally must have reflected the structure of the new music, perhaps corresponding to the number of notes in a line, for example. Although there are examples of yuefu poems that employ uneven lines (see, for example, C4.4), the majority of yuefu poems have lines of five characters. Yuefu poems also have in common with the ci an origin in music. However, while the ci of a particular tune title are united by a common prosodic matrix, yuefu poems that share the same title are united by their common theme or subject (chap. 4).

Some tune titles do require even lines; in fact, many of the earliest literati song lyrics in the short form (xiaoling, as opposed to the long form, manci, which developed later) closely resemble the regulated quatrain (jueju [chap. 10]), having four lines of seven characters each. But in place of the tight, unitary structure of regulated shi poetry (chap. 8), the structure of the ci is at once more fluid and less unified, displaying much less parallelism and often shifting between imagistic presentation and the quotation of inner speech. And as opposed to the suspension of time that occurs in Tang regulated verse as it moves from the temporal to the universal and back again, the ci moves more freely between past, present, and imagined time in its depiction of complex emotional states and processes.

During the Song, with the development of the long form of the ci, these characteristics became more pronounced. The manci (chap. 13) accommodates more narration and allows for the exploration of more complex and multifaceted emotional states. This is partly a result of its increased length (usually between seventy and one hundred or even two hundred characters, as opposed to fewer than fifty-eight characters in the xiaoling) and partly a result of the increased use of so-called line-leading words (lingzi). These short words or phrases used at transitional points in the poem “increased rhythmic flexibility, enhanced semantic continuity, and highlighted the distinct turns in the complex unfolding of the poet’s feelings.”2

To put flesh on some of these generic characteristics of the ci, let us look at a poem by one of the best-known poets of the genre, the last emperor of the Southern Tang, Li Yu (937–978). The Southern Tang was one of the smaller kingdoms that arose during the post-Tang period of division known as the Five Dynasties. Taken prisoner in 975 by the new Song emperor, who eventually had him poisoned, Li Yu is credited with having broadened the thematic range of the ci and made it more personal.

To the Tune “Crows Call at Night”

(or “Pleasure at Meeting” [Xiang jian huan])

Without a word, alone I climb the West Pavilion.

2 The moon is like a hook.

In the lonely inner garden of wutong trees is locked late autumn.3

4 Cut, it doesn’t break,

Tidied, a mess again—

6 This separation grief.

It’s altogether a different kind of flavor in the heart.

[QTWDC 4.450]

The most visually striking feature of this song lyric is the variation in line length. This particular tune title requires lines of three, six, and nine characters. Like the five-or seven-character lines of Tang regulated verse, these lines can be broken down into units of two and three characters each. The nine-character lines can be seen to derive their rhythm from the basic (2 +) 2 + 3 rhythm of a regulated-verse line, with the addition of one more segment of two characters at the beginning of the line. Similarly, the three-character line has one less two-character segment than a regulated-verse line. This relationship demonstrates how the semantic rhythm of the ci at once derives from and constitutes a deliberate departure from that of the shi.

Regulated shi poetry of the Tang requires a single rhyme in the level (ping) tonal category. In contrast, the ci permits the rhyme to be in either the level or the oblique tonal category and allows for more complex rhyme schemes. As the following diagram of the tonal patterning of this tune shows, two rhymes are in evidence. The first is in the level tonal category (as indicated by ─ and the hollow triangular rhyme marker △), and the second is in the deflected or oblique (ze) tonal category (as indicated by | and the solid triangular rhyme marker ▲; symbols in parentheses indicate that either tonal category is acceptable in that position) (for a discussion of tonal categories, see pp. 170–172).

The strict tonal alternation of regulated verse is absent, and in its place is a tonal patterning that presumably followed the contours of the poem’s musical setting in some fashion. Since the music of these tunes has been lost, it is not clear exactly what form this relationship took—whether the tonal category corresponded to a melodic contour, for example, or to the length of notes (oblique tones are more abrupt, while level tones are more drawn out). As time went on, poets began to differentiate not only the two tonal categories of ping and ze but also the specific five tones themselves.

Note that rhyme occurs in each line of this poem, while in regulated verse it occurs only at the end of a couplet. This corresponds to the fact that in the song lyric, the couplet gives way to the strophe as the basic structural building block of the poem.4 A strophe is a unit of one to four lines ending in a rhyme. In English translations of ci poems, a strophe often corresponds to a sentence, since strophes tend to function as semantic units.

In the ci, the stanza break comes to serve an important aesthetic function, with the expectation that it will introduce a change in meter, rhyme, setting, or mood, in a practice known as huan tou. The form this transition takes in any particular song lyric is a unique and important element of the poem’s aesthetic effect. In this sense, the ci is both similar to and different from Tang regulated verse; the third couplet of a regulated shi poem was also expected to introduce a thematic shift or change (chap. 8). But in regulated verse, a strong metrical and tonal equivalence unites the second and third couplets, thus in effect subordinating the thematic shift to the tight unity of the poem. This is replaced in the ci with variation of both line length and tonal patterning.

In Li Yu’s poem, the thematic transition is marked metrically by the three short lines and by a change in rhyme. The setting shifts from the external surroundings of the lonely speaker to internal musings on his or her own emotions. In the first stanza, the speaker’s loneliness, confinement, and aging are reflected in the lonely wutong trees and the lateness of an autumn locked deep in the garden. The second stanza is an immediate, self-reflexive consideration of the speaker’s grief, prized by generations of readers for the remarkable imagery of the first two lines and for the enigmatic gesturing toward a characterization of that grief in the highly colloquial concluding line. But to really appreciate the literary achievement that a poem like this one by Li Yu represents (and to which this brief reading does not begin to do justice), we should look first at the development of the genre before his time.

There are two major sources of early ci poetry. The first is the extensive trove of manuscripts unearthed in the first decades of the twentieth century in the Buddhist caves at Dunhuang in Gansu Province. Along with paintings and manuscripts of various religious and nonreligious genres, the find unearthed numerous early song lyrics, mostly anonymous and characterized by wide thematic variation. The second major source is the literati ci anthology Huajian ji (Among the Flowers Collection), which dates from the Five Dynasties period. The anthology, compiled in the mid-tenth century, collects five hundred poems, by early ci masters Wen Tingyun (813?–870) and Wei Zhuang (836–910), along with a number of poets of the court of the western kingdom of Shu. (By the Song dynasty, poets began publishing individual collections of their own ci poetry.)

The first poems considered are a pair of anonymous poems from Dunhuang. They constitute a dialogue between a man and a woman that plays with the conventions of female abandonment (thematic table of contents 2.3) in a lively dramatic exchange. These conventions of abandonment and neglect have a long history in the tradition, the roots of which can be traced back in the literati poetic tradition to the Shijing (The Book of Poetry) and the Chuci (Lyrics of Chu).

The first poem of the pair presents the male speaker’s accusatory interrogation:

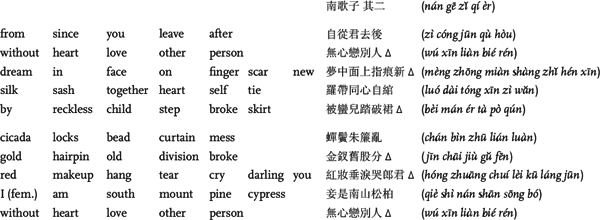

To the Tune “Southern Tune,” No. 1

Standing leaning at the beaded curtain,

2 With whom have you been sharing your heart?

The new scratches on your face are plain as day.

4 Who tied the love knot in your silk sash?

And who’s torn the hem of your skirt?

6 Why are your cicada locks in disarray?

And your hairpin—why is it broken?

8 For whom these tear streaks in your rouge?

Tell me straight, here before the hall.

10 Don’t hem and haw.

[QTWDC 7.893]

The colloquial flavor of the poem makes itself felt in the sheer number of interrogatives (six in a ten-line poem). The male speaker enumerates in accusatory tones aspects of the woman’s appearance, some of which have erotic overtones (the scratches on the face and the mussed hair). The woman’s position in a doorway could be regarded as a suggestive, beckoning posture. The “love knot,” or “heart” knot, in her sash would usually have been tied by her lover. The hairpin may have been the speaker’s own love token.

The man’s interrogating voice draws attention to his power to exact an account while, ironically, piling up proofs of his own neglect. The female speaker turns these proofs into a catalog of evidence for her own devotion in the second poem of the pair:

To the Tune “Southern Tune,” No. 2

Since you went away

2 I’ve no heart to love another.

New scratches on my face appeared in my dreams.

4 I tied the love knot in my own silk sash.

It was the child who stepped on my hem.5

6 The beaded curtain mussed my cicada locks.

The hairpin broke along an old crack.

8 These streaks in my makeup are from crying for you.

I’m like the cypresses on South Mountain—

10 I’ve no heart to love another.

[QTWDC 7.893]

The second poem carries on the colloquial flavor of the first and reproduces its rhyme scheme. Note that there is a slight variation in line length between the two poems (in lines 5 and 10). This is more common in early, popular ci examples, but later ci pattern books also commonly list a number of variations on the same tune title. The first line sets the tone for the reproaches that will follow by foregrounding the fact that it is the man who had left her. Her straight answers to each question in turn enumerate evidence of the man’s neglect (“I tied the love knot in my own silk sash [since you were not here to tie it]”) and her own faithfulness (“These streaks in my makeup are from crying for you”). The speaker uses the humble first-person feminine pronoun qie (literally, concubine) in line 9 and the intimate second-person address langjun (used by a woman for her husband or lover) in line 8; together, these place the entire defense in the context of an intimate and faithful relationship. The “cypresses” and pine trees in line 9 are traditional symbols of integrity and faithfulness because they do not change with the seasons. The poem ends with a word-for-word reiteration of the declaration of devotion in line 2.

The first poem follows the contours of the male gaze as it takes in elements of the woman’s appearance that are conventionally associated with abandonment, beginning with her posture in a doorway and then moving up and down her body. As such, it makes explicit the suggestion of eroticism that had been attached to some conventional depictions of abandoned women, especially in the sensuous palace-style poetry of the Six Dynasties period, which preceded the Tang (chap. 7). When the second speaker couches the same elements in a defense of her faithfulness, the audience associates them with other abandoned women’s voices from the folk tradition, in which male changeability is typically contrasted with female constancy. These references lend credibility and weight to the woman’s defense, although it is still difficult for us to resist questioning its reliability.

The next three poems in this selection are found in the literati ci anthology Huajian ji. Although it represented an effort to legitimize the song lyric as a genre, the Huajian ji is largely dominated by what were considered “feminine” themes of love and abandonment. It is the influence of the more ornate and sensuous strain of abandonment complaints, influenced by Six Dynasties palace-style poetry, that we see in this first selection, by Wen Tingyun. A skilled musician with a reputation for frequenting the pleasure quarters, Wen Tingyun is usually credited with having adapted the popular form of the ci for a literati audience; he also originated a number of tune patterns. The influence of literati sensibilities should be apparent in the poem’s diction and imagery.

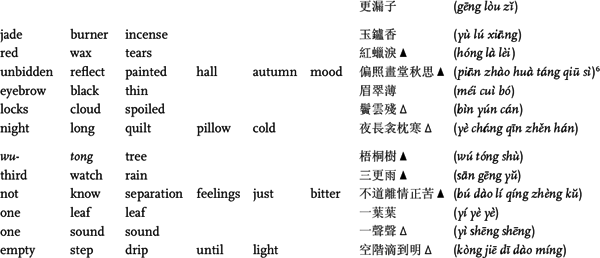

To the Tune “On the Water Clock at Night”

Incense in the jade burner,

2 Red wax tears

Unbidden, reflect an autumn mood in the painted hall.

4 Blackened brows fade,

Cloud locks are tousled,

6 The night is long, quilt and pillow cold.

Wutong trees and

8 Third-watch rain are

Unaware of separation throes.

10 Leaf after leaf,

Sound by sound

12 Drips on the empty steps ’til dawn.

[QTWDC 2.210]

The neglect of makeup, the cold bedding and pillow, and the woman’s sleeplessness are clear markers of the abandonment convention. The context of the “painted hall” suggests a high-class subject, and the presentation of small details of her appearance in bed alone (her fading brows and tousled locks on a cold pillow) subtly suggest the presence of a male voyeur.

Several things immediately set this poem apart from the anonymous examples from Dunhuang we have just looked at. Whereas both the male and female speakers in the two poems were just that—speakers—this poem presents the abandoned woman’s emotional state through a depiction first of the interior scene in the first stanza, and then of the exterior scene in the second. The only voice we hear is that of the rain dripping onto or from the large leaves of the wutong tree, in which nature seems to conspire to compound the woman’s grief. But from the very beginning, elements of the woman’s surroundings are made to bear emotional weight. The candle’s tears in line 2 are a typical example of the poetic device of fusing emotion and scene (qing jing jiao rong). This practice of imbuing physical elements of the scene with human emotion brings to mind the Western notion of the “pathetic fallacy,” a term coined by John Ruskin in the nineteenth century for a practice he deplored.

In lines 3 and 9, pian (unbidden) and zheng (just, exactly) are what are known as “empty words” (xuzi), particles that lack concrete referents but that add instead to the subjective and emotional quality of the lines. The use of empty words, or function words, contributes to the ci’s characteristic tendency to qualify its imagistic presentation. The rough parallelism discernible in the relationships between the paired three-character lines suggests a greater degree of attention to poetic craft than we saw in the Dunhuang poems; this is, of course, in keeping with the poem’s literati authorship.

A second example of Wen Tingyun’s song lyrics presents a more eroticized and objectified picture of its female subject. The poem’s more suggestive quality is perhaps not surprising, given that it is less a complaint of abandonment than a depiction of morning ennui in the context of a new love affair.

To the Tune “Buddha-Like Barbarian”

Layer on layer of little hills, golds shimmer and fade,

2 Cloud locks hover over the fragrant snow of a cheek.

Lazily rising to paint on moth eyebrows,

4 Dallying with makeup and hair.

Blossoms are mirrored behind and before,

6 Flower faces reflect one another.

Newly embroidered on a jacket of silk

8 Are pair after pair of golden partridges.

[QTWDC 2.194]

This poem employs more elevated diction and more ornate imagery than “On the Water Clock at Night.” In general, it is imagistically denser, using less-continuous syntax and more juxtaposition of imagery. Set entirely in the interior of the subject’s intimate boudoir, the poem presents a series of images through which the actions of the subject’s morning routine become perceptible. The first two lines, often cited by subsequent critics, evoke the image of the female figure by reference to the resplendent screen that hides her in line 1, and the smallest physical detail of her recumbent pose in line 2. The potential motion implicit in the locks of hair that are, literally, about to cross her white cheek makes this line particularly memorable. These loosely connected images set off the progression of the voyeur’s gaze as the subject languidly rises, attends to her hair and makeup, and examines herself in the mirror.

Despite its intimacy, the observer’s perspective on the female subject remains external, the only suggestions of the woman’s emotional state being her laziness at her toilet and the pairs of partridges (suggesting conjugal happiness) that she has recently embroidered. None of the imagery, from the shimmering golden hills in line 1 to the flowers in the woman’s hair in lines 5 and 6, reflected in mirrors in front of and behind her, seems to have any emotional function other than to highlight and reflect the woman’s beauty in her ornate setting. At the same time, this contentment with a surface treatment of its subject (of which the reflection of a reflection in lines 5 and 6 is emblematic) is itself important to the poem’s emotional effect. Although the woman has no apparent cause for discontent, the motions of her morning routine are imbued with a sense of ennui.

Morning languor appears in a more melancholy context in this poem by Wei Zhuang, also from the Huajian ji. Wei Zhuang’s poems are generally considered more directly lyrical than those of Wen Tingyun. Here this quality is particularly evident in the first stanza:

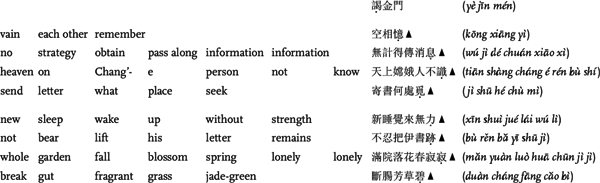

To the Tune “Audience at Golden Gate”

Vain to remember him,

2 No way to get news through.

Chang’e in the heavens doesn’t recognize me.

4 Where shall I seek him, to send him a letter?

Waking, languid, from new sleep,

6 Can’t bear to take up the remains of his letter.

A courtyard full of fallen blossoms—spring is lonely, lonely

8 —Heartbreaking, the fragrant grasses green.

[QTWDC 5.542]

The general sense of vanity (and, in particular, the frustration of communication) with which the poem begins is an element of the abandonment convention. Other conventional elements include the indifference of nature or heaven (speakers would commonly appeal to Chang’e, the goddess of the moon, for help, for presumably she would be able to see the absent lover) and the references to the end of spring and the irretrievable loss of time. The first stanza is entirely devoted to the subject’s inner speech, while the second introduces natural imagery that is made to bear the full weight of her emotion. Not only have the blossoms fallen, but the courtyard is full of them, in a reflection of the speaker’s overwhelming, overflowing sense of loss. The spring is described as lonely. Notably absent are details of the boudoir in which she wakes. Instead, all the imagery suggests the reflection of her interior thoughts in the exterior world, in another example of the fusion of feeling and scene.

It is important to note that in the last line, the relationship of heartbreak in the first two characters with the “fragrant grasses green” is not explicit. As translated here, the heartbreak applies to the speaker, who sees the grasses, the color of which reminds her, again, of late spring and hence of the irretrievable loss of time. Another translation would be “Heartbroken, the fragrant grasses green,” in which the emotion is linked more explicitly to the grasses. While in either case the emotion must ultimately be traced back to the speaker, the poetic effect is quite different. In Chinese, these phrases can simply be juxtaposed. No decision needs to be made concerning the attribution of the emotion. This is one of the ubiquitous problems in the translation of Chinese poetry into English: the translator is often forced to make a choice one way or the other in order to craft a smooth English line. The same is true for the choice of pronoun where none is present in the original or for the choice of verb tense. For the Chinese reader, these details can remain unspecified, allowing the poem to retain its polysemous and indeterminate, evocative quality.

A similar interior perspective and direct, unornamented style characterize the ci poems of Li Yu, with whose poem we started this chapter. Li Yu is generally considered to have been a total failure as a political leader—indeed, some have suggested that his failure in this arena may have been a prerequisite of sorts for his accomplishment in the literary arena. The following poem should allow us to observe how Li Yu takes the genre to a new level of personal expression.

To the Tune “Beautiful Lady Yu”

Spring flowers, autumn moon—when will they end?

2 Past affairs—who knows how many?

Last night in the small pavilion the east wind came again.

4 I dare not turn my head toward my homeland in the moonlight.

The inlaid balustrade and jade stairs must still be there

6 —It’s only the youthful faces that have changed.

I ask you, how much sorrow can there be?

8 Just as much as a river full of spring waters, flowing east.

[QTWDC 4.444]

Certain elements are familiar from the female-voiced abandonment complaints we have already seen: the interrogatives, the use of the second-person pronoun jun, the colloquial elements and empty words, like bukan (not dare) and qiasi (just like). The east wind, like the rain in Wen Tingyun’s “On the Water Clock at Night,” seems to conspire against the speaker by coming yet again. But the context is less particular and more universal and philosophical. The opening parallelism, “spring flowers, autumn moon,” evokes a sense of the entirety of time (by reference to opposing seasons) and nature (by its opposition of an earthly with a cosmic image). When read in the light of the reference to the speaker’s “homeland” in line 4, the “past affairs” transcend the personal to encompass national history. At the same time, the particularity of the speaker’s emotion is retained. Line 3 situates the speaker in a specific place at a specific time, and line 4 gestures toward the intensity of his emotion by depicting him unable even to look toward the object of his nostalgia (and here it is a place, not a person, for which the speaker longs). The poem closes with a question and an answer that once again link emotion and scene. Unlike the typical fusion of feeling and scene, however, in which the connection between the two remains implicit, here the speaker seems to cast about in his mind for an image that adequately captures the swelling and unstoppable quality of his emotion, which he then offers in an explicitly apt comparison: qiasi (just as much as) a flooded river overflowing with the melting snows of spring.

The gender of the speaker in this poem is ambiguous, but since critics traditionally have interpreted Li Yu’s poems in the light of the details of his biography, the speaker has usually been assumed to be the poet himself. Because this and others of Li Yu’s best poems date from the period of his captivity at the Song court, references to the homeland and changed human circumstances are easy to connect to Li Yu’s personal situation.

The next poem has variously been attributed to Feng Yansi (903–960) (under the tune title “Magpie Perching on a Branch”) of the Southern Tang, who flourished during the reign of Li Yu’s father, and to Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072), a statesman and an essayist of the Northern Song. Feng Yansi’s ci poetry consistently draws on the conventions of abandonment complaints, and Ouyang Xiu’s ci poetry also falls within the tradition of Feng and the poets anthologized in the Huajian ji. For this reason, the dispute over the poem’s authorship is difficult to resolve. The ci had, by the Northern Song, become a popular pursuit of intellectuals, functioning as a sort of parallel genre to the shi that, while it lacked the shi’s seriousness of subject matter, was considered an artistic pursuit worthy of a public figure such as Ouyang Xiu. The shi and ci at this point occupied different spheres, characterized by a division of labor in which the ci was assigned the treatment of delicate emotions. If the shi was seen as a vehicle of the will or intent (shi yan zhi [the shi gives voice to the intent]), then the ci was seen as a vehicle of feeling (ci yan qing [the ci gives voice to emotion]).

To the Tune “Butterflies Lingering over Flowers” (or “Magpie Perching on a Branch” [Que ta zhi])

Deep in the walled garden, deep—how deep?

2 Mist stacks on willows,

Uncountable layers of screens and blinds.

4 The jade bridle and ornate saddle are in the brothel district—Though the tower is tall, one can’t see Zhangtai Road.7

6 A driving rain, a mad wind, late in the third month.

A door keeps out the twilight,

8 But there’s no way to keep spring from going.

With tear-filled eyes I ask the blossoms,

but the blossoms do not answer—

10 In a swirl of red they fly into the swings.

[QTWDC 4.369]

The first stanza piles up images of blocked vision and seclusion, multiplied indefinitely by the question “how deep?” and the adjective “uncountable.” The reference to the absent lover’s bridle and saddle in the entertainment district clearly marks the poem as an abandonment complaint. The poem moves from scene to feeling, in a typical progression known as “entering the emotion through the scene” (you jing ru qing), but then it closes with a particularly memorable natural image, for which the poem has been prized. Unlike Li Yu’s speaker in “Beautiful Lady Yu,” the speaker in “Butterflies Lingering over Flowers” does not make explicit her closing question; the dynamic response of the flowers, rather than answering the speaker’s unspoken question, seems to embody her chaos of swirling emotion. Wang Guowei (1877–1927), a late Qing critic strongly influenced by Western aesthetics and philosophy, cited these last two lines as an example of a “personal” scene or state, a you wo zhi jing, as opposed to what he regarded as the superior impersonal, or literally “selfless,” scene or state, the wu wo zhi jing (chap. 6). These lines are also a masterful example of the fusion of feeling and scene and an ingenious variation on the image of fallen blossoms (signifying the end of spring and the passage of time). Even while the blossoms mirror the speaker’s emotions, they also refuse to serve as her interlocutor; she asks, but they do not speak, leaving her alone with her grief. While male speakers in shi poems tend to find communion and consolation in nature, in this and other female-voiced ci poems, nature is more often unfeeling, adding to the speaker’s grief, or at least failing to provide the comfort she seeks.

Our final poet, Yan Shu (991–1055), was another Northern Song statesman whose ci poetry followed in the tradition of Feng Yansi and the Huajian ji poets. With Ouyang Xiu, he is considered a master of the xiaoling. These poets’ song lyrics remain largely within the “delicate and restrained” wanyue school, as opposed to the “bold and unrestrained” or heroic haofang school, which developed as the thematic range of the ci broadened even further during the Song. The following poem is acclaimed for its subtle and implicit expression of separation grief. This degree of implicitness, in which there is no explicit reference to the object of the speaker’s complaint, has traditionally been praised by critics with the phrase “not a word verbalizes complaint” (wu yi zi yan yuan).

To the Tune “Sand in Silk-Washing Stream”

A new song, a cup of wine;

2 Last year’s weather at the old pond terrace.

The setting sun sinks in the west—when to return?

4 Do what one may, blossoms will fall;

As if we knew each other, the swallows come back.

6 In the little garden I pace a fragrant path alone.

[QSC 1:89]

The even, seven-character lines of this ci might suggest a similarity to regulated verse, except for the number of lines (six) and the absence of parallelism in the first stanza. All three lines of the first stanza are independent strophes disconnected from one another, so that the reader must construct the relationship between them. Were the new tune and the cup of new wine situated at the old pond terrace last year, or are they in the present? Is the sunset of line 3 happening now, or is it remembered? Or, again, is the sunset adopted simply as a philosophical emblem of the past and of loss? In contrast to the relative discontinuity of these three lines, the first two lines of the second stanza are, in fact, a very well regarded parallel couplet, complete with tonal opposition.

The thoughts of the speaker, who paces alone on the fallen blossoms that make the path fragrant, remain veiled. The only explicit reference to the speaker’s situation is in the word “alone,” but several other elements lead us to read this as a poem about separation grief (notably, a common theme of shi poetry). There is the practice of sending off a friend with a cup of wine, the recollection of something that happened “last year,” the question of when something or someone (the sun or the friend) will come back, the return of the swallows. But the emotion remains at arm’s length, as vague as the sense of familiarity aroused by the swallows: “as if we knew each other.”

If each line of the first stanza is disconnected from the next, each line of the second stanza approaches the speaker’s emotion from a different direction. Yan Shu’s poem addresses its subject from without, leaving an empty space at the center where the complaint (yuan) remains unspoken.

In conclusion, it may be useful to review some characteristics of the shorter, xiaoling, ci poems, which have been the subject of this chapter. Generally consisting of two stanzas (although some have only one), the poems are structurally simpler than the more elaborate manci (chap. 13). Often the break between stanzas marks a move from past to present, from interior to exterior, from speech to scene, or vice versa. In the manci, these shifts become more complex. Early literati ci may betray the influence of shi aesthetics in their use of juxtaposed scenes and states; although the ci allows more elaboration of the relationship between them than does the shi, it remains for the manci to take this elaboration further, incorporating descriptive and narrative sequences that the xiaoling could never accommodate. Thematically, the xiaoling tends to restrict itself to subjects involving the delicate and personal emotions surrounding love, abandonment, separation, or nostalgia, treating these subjects with a characteristic allusiveness that accords with its brevity and concision. The manci came to accommodate a broader variety of subjects and a greater range of emotion, which its length and complexity allowed it to treat in a more exhaustive manner. But the xiaoling set the stage for the manci and the development of the haofang (heroic) style by adapting a popular medium for literati use and carving a niche for it in the hierarchy of literary forms that were acceptable for intellectual pursuit.

NOTES

1. My approach in this chapter is certainly informed by these perspectives, although it is by no means strictly feminist.

2. Shuen-fu Lin, “The Formation of a Distinct Generic Identity for Tz’u,” in Voices of the Song Lyric in China, ed. Pauline Yu (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 21.

3. The wutong is the Chinese parasol tree (Firmiana simplex).

4. Shuen-fu Lin, The Transformation of the Chinese Lyrical Tradition: Chiang K’uei and Southern Sung Tz’u Poetry (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978), 106–107.

5. Other manuscripts have a closely related character meaning “monkey” in place of “child.”

6. The character sì is read here with the fourth tone because the pattern for this tune title requires an oblique tone rhyme in this position.

7. Zhangtai was a street in Han dynasty Chang’an that became a euphemism for the brothel district.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Bryant, Daniel, ed. and trans. Lyric Poets of the Southern T’ang: Feng Yen-ssu, 903–960, and Li Yü, 937–978. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1982.

Chang, Kang-i Sun. The Evolution of Chinese Tz’u Poetry: From Late T’ang to Northern Sung. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Egan, Ronald C. The Literary Works of Ou-yang Hsiu (1007–72). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Fusek, Lois, trans. Among the Flowers: The “Hua-chien chi.” New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Lin, Shuen-fu. The Transformation of the Chinese Lyrical Tradition: Chiang K’uei and Southern Sung Tz’u Poetry. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Liu, James J. Y. Major Lyricists of the Northern Sung, a.d. 960–1126. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Rouzer, Paul F. Writing Another’s Dream: The Poetry of Wen Tingyun. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Samei, Maija Bell. Gendered Persona and Poetic Voice: The Abandoned Woman in Early Chinese Song Lyrics. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2004.

Wagner, Marsha. The Lotus Boat: The Origins of Chinese Tz’u Poetry in T’ang Popular Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

Wei Chuang. The Song Poetry of Wei Chuang (836–910). Translated by John Timothy Wixted. Tempe: Center for Asian Studies, Arizona State University, 1978.

Yates, Robin D. S. Washing Silk: The Life and Selected Poetry of Wei Chuang (834?–910). Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1988.

Yu, Pauline, ed. Voices of the Song Lyric in China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

CHINESE

Kang Zhengguo 康正果. Fengsao yu yanqing: Zhongguo gudian shici de nüxing yanjiu 風騷與艷情—國古典詩詞的女性研究 (Virtue and Love: A Study of Femininity in Classical Chinese Poetry). 1988. Reprint, Taipei: Yunlong, 1991.

Lin Meiyi 林梅儀. Dunhuang quzici jiaozheng chubian 敦煌曲子詞斠證初編 (A Preliminary Collection of Dunhuang Lyrics, with Emendations). Taipei: Dongda tushu gongsi, 1986.

Murakami Tetsumi 村上哲見. Tang Wudai Beisong ci yanjiu 唐五代北宋詞研究 (A Study of the Song Lyrics of the Tang, Five Dynasties, and Northern Song). Translated by Yang Tieying 楊鐵嬰. Shaanxi: Renmin, 1987.

Ren Bantang 任半塘 [Ren Na 任訥]. Dunhuang geci zongbian 敦煌歌詞總編 (A Comprehensive Anthology of Dunhuang Song Lyrics). 3 vols. Shanghai: Shanghai guji, 1987.

Shi Yidui 施議對. Ci yu yinyue guanxi yanjiu 詞與音樂關係研究 (A Study of the Relationship of Song Lyrics with Music). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue, 1989.

Wang Guowei 王國維. Jiaozhu Renjian cihua 校注人間詞話 (Collected Comments on “Talks on Song Lyrics in the World of Men”). Edited by Xu Diaofu 徐調孚. Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju, 1961.

Xia Chengtao 夏承燾 and Wu Xionghe 吳熊和. Zenyang du Tang Song ci 怎樣讀唐宋詞 (How to Read the Song Lyrics of the Tang and Song). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin, 1958.

Yeh Chia-ying [Ye Jiaying] 葉嘉瑩. Jialing tanci 迦陵談詞 (Jialing’s Talks on Song Lyrics). Taipei: Chun wenxue, 1960.

Zhang Yiren 張以仁. Huajian ci lunji 花間詞論集 (Collected Writings on the “Among the Flowers Collection”). Taipei: Zhongguo wenzhe yanjiusuo choubeichu, 1996.