13

13

The form of the song lyric discussed in chapter 12 is, as suggested by the Chinese term xiaoling, comparatively short and small in scale. In this chapter, we shall look at another form of the genre, the “long song lyric” (manci). Our examination will reveal that the differences between these two forms are found not only in their length but, more importantly, also in their structure and their capacity for poetic description and expression.

The origin of the manci, like that of the xiaoling, can be traced back to the popular song-verse tradition of the Middle Tang (ca. 750), but, unlike the xiaoling, it took much longer for the manci to be appropriated by literati poets and to be developed, in the Song dynasty, into a major poetic genre. An important reason is that the musicality of the manci—or manqu ci (slow-paced song verse)—is much more complicated than that of the xiaoling. Whereas the professional songwriters were masters of tones and beats but lacked the literary caliber to advance the poetic quality of their works, the educated elite—when they deigned to practice this “low” genre, with its irresistible melodious appeal—found its musical features too complicated for dilettantes. Refining this art form and bringing its literary potential to the full required the combination of a popular musician’s ear and a scholar’s pen. This rare combination was nowhere to be found until the eleventh century, when Liu Yong (987–1053) appeared on the scene.

Even when he wrote about love, the most stereotyped subject of the song lyric, Liu Yong did not just repeat clichés and recycle stock poetic situations. In lyrics on the new subjects he introduced to the genre, he produced descriptions of various aspects of urban life, a detailed delineation of personal feelings of a frustrated scholar, and the landscape seen through the eyes of a melancholy wanderer. The poetic form of the shorter xiaoling could not meet his needs. He therefore turned his eyes and ears to the longer form offered by the manci.

While other literati poets, with few exceptions, were interested in or, rather, capable of writing only xiaoling when they composed song lyrics, Liu Yong wrote mostly manci. Not satisfied with merely putting words to the existing tunes, he composed new tunes to better carry his words. For him, a manci should not be an elongated xiaoling but an organism permitting an elaborate description and narration to develop with a certain order and logic. To achieve this, he drew on the descriptive syntax of the rhymed prose (fu) of past ages, on the one hand, and, on the other, learned from the flexible everyday language of the popular tradition. The descriptive power of his song lyrics benefited most, however, from his understanding of the intrinsic musicality of the manci from the popular tradition. The collection of his works is appropriately titled Collection of Musical Pieces (Yue zhang ji): he set many of his songs in specific musical keys (diao), rarely done by other scholar-poets, to ensure that they were sung in the right way to achieve optimal effects. His sensitive awareness of the musicality of the song lyrics of the popular tradition, especially the contours of the sound patterns or structural shapes of the songs, as realized in the performances by musicians and singers, taught him how to organize an extended poetic presentation. One of the most effective organizational devices he developed was the lingzi (leading word). Used at juncture points in a description or narration, leading words comment on the perceptional experiences, facilitate continuity, ease transitions, help create the desired rhythm, control sound flow, and, perhaps most importantly, reveal the relationship between the component parts of the descriptive or narrative whole, whether this relationship is linear, multilayered, or both.1

Most of Liu Yong’s innovations became the generic features of the manci. He left to the ci poets who followed a powerful poetic vehicle capable of tasks unimaginable in the xiaoling, such as the multifaceted description of scenery, the presentation of the twists and turns of complicated human feelings, and the narration of the drama of human relationships.

Liu Yong’s contribution to the establishment of manci conventions was unanimously acknowledged by the ci practitioners and critics who came after him. Nonetheless, his manci works were considered by many as vulgar and his language as excessively low. The true reason for such harsh criticism was that both his conduct in private life and the self-image he created in some of his songs showed him as a songwriter from the pleasure quarters more than as a member of the educated elite.

Among his critics was Su Shi (1037–1101), whose versatile talent and comprehensive achievements secured him a leading position in almost every sphere of the cultural and literary activities of his time. Although Su Shi was critical of Liu Yong’s language, which was the living language used by the singers and entertainers of the time, he admired Liu Yong’s art. In his own creative experiments with the new manci form, he carried on the work that Liu Yong had started.

What Su Shi did to the song lyric was quite appropriately summarized as “treating ci as shi,” and he was both praised and criticized for this practice. The consequence of his experiment was augmented by his position as a formidable figure on the literary scene, with a sensitive personality and a stock of personal experience enriched by his eventful involvement in the political life of his day. After him, no one could say that the ci was only a low genre.

Some critics questioned whether the new type of song lyric he introduced could still be called ci. For example, in her essay “A Critique of the Song Lyric” (Ci lun), his younger contemporary Li Qingzhao (1084–1151) dismissed his ci works as “nothing but shi poems with irregular lines.” A fine musician and an accomplished ci writer herself, Li Qingzhao insisted on a rigorous identity of the song lyric as an independent poetic genre. She advocated a careful distinction between the ci and the shi. Of the many features of the genre she discussed in her essay, the most important was the musicality of the ci tune. Although she claimed that Liu Yong’s language was “as low as dirt,” she commended him for having been a connoisseur of the music of the ci.

The expressive power and pliability of the manci form are also seen in the works of Xin Qiji (1140–1207). Besides being a ci poet, Xin was first of all a man of action, having participated in his youth in a major military uprising against the Jurchens, who ruled the northern part of China, and having made a name for himself trying to accomplish the impossible task of reclaiming the lost territory of central China after he went to the south and joined the Southern Song (1127–1279) court. His manci works are informed by his legendary life experiences and his ebullient personality. In his hands, the poetic form that was originally fit for only boudoir sentiments became an effective vehicle for conveying the complicated feelings and emotions of a larger-than-life heroic figure.

In Liu Yong’s best lyrics, the poetic mood and the sentiment of the persona are conveyed through the thoughtful presentation of elaborate descriptions of scenery and the narration of a series of poetic events:

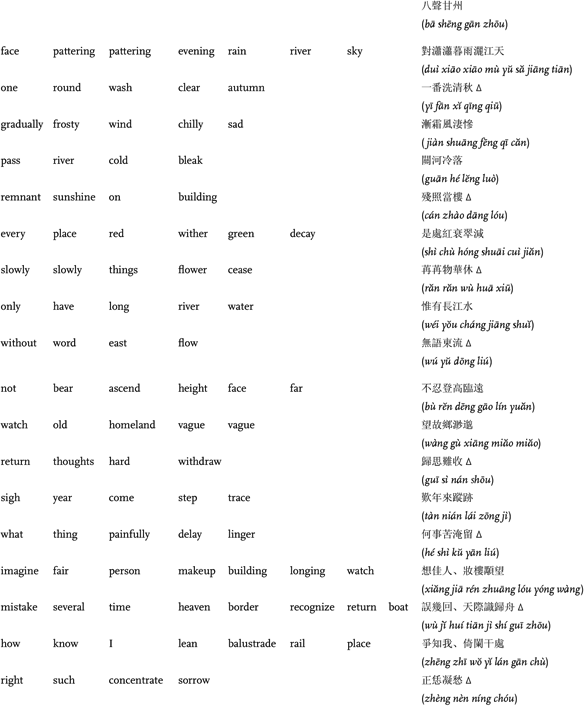

To the Tune “Eight Beats of a Ganzhou Song”

I face the splashing evening shower sprinkling from the sky over the river

2 And washing clean the cool autumn.

Gradually the pressing frosty wind gets more and more chilly,

4 The mountain passes and rivers turn bleak,

While the last ray of the sun lingers on the balcony.

6 Here and there the red withers and the green decays—

Slowly nature’s blossoms fade.

8 Only the water of the Yangtze

Silently flows east.

10 I cannot bear to ascend the height and look into the distance.

I look toward my homeland afar, not to be seen;

12 Thoughts of returning home just would not stop.

I sigh over my wanderings these years;

14 What is it that keeps me here?

I imagine my fair one is now gazing earnestly out of her window,

16 Mistaking again and again some returning boat on the horizon for mine.

How could she know that I, leaning against the balustrade here,

18 Am lost in sorrow?

[QSC 1:43]

The verb “[I] face” at the very beginning of the poem seems to be unnecessary, since even without it, the scene’s being in front of the persona is quite obvious. But it is precisely words of this kind that deserve our special attention. They are typical examples of leading words, the most important device that Liu Yong developed for the manci form.

In the first stanza, the autumn scene is not described but is methodically presented in four steps. A leading word (or phrase) is used to lead and to define each step, explaining which aspect of autumn is being perceived and from what perspective. The four steps are linked in such a way that they echo one another while moving along in linear order, reflecting nuanced changes in the persona’s mood as he undergoes four different phases in his sensual experience of autumn.

The first leading word, “face,” which stands at the beginning of the song and introduces the evening scene (lines 1–2), highlights the active interaction between the gazer and what is gazed and intensifies the impact of the “cool autumn” (line 2) on the poet. The second step (lines 3–5) follows by reflecting on that coolness of the season. The persona’s sensual perception takes a turn here. While the first step emphasizes—as suggested by the leading word “face”—the spatial vastness of nature, the second step probes its temporal depth. The leading word “gradually” (line 3) tells how the autumn chill invades slowly but inexorably, turning mountains and rivers “bleak” (line 4). The lingering setting sun, the “remnant” (can) of the day that has passed (line 5), also implies the gradual yet unstoppable lapse of time and symbolizes the dying of the year. The time element in the second step has some bearing on the persona as well: he has been lingering on the balcony long enough to notice the inching away of the sunlight and the ever-advancing autumn.

The phrase “here and there,” which marks the beginning of the third step (lines 6–7), also performs a leading function. It indicates that the persona now turns his eye to the things around him and sees the signs of dying and decay. The spatial (“here and there”) and the temporal (“slowly” [line 7]) aspects of autumn are subjected to scrutiny one more time. The persona then looks afar again to see if there is anything alive, and he finds that “only”—thus begins the fourth step (lines 8–9)—the Yangtze is in movement. Symbolizing the unending flow of time, the eastward-flowing river never stops. The image of the ceaselessly flowing river underscores the bleakness of the scene in the previous lines.

The purpose of this carefully planned four-step presentation of autumn is to prepare for the poet’s emotional response in the second stanza. Here we see the structural function of the stanzaic division in the song lyric (chap. 12). In Liu Yong’s manci, the division plays an even more important role in the organization of his poetic description and narration.

Again, a step-by-step scheme becomes visible as the persona unfolds his inner thoughts in the second stanza. It begins where the first stanza leaves off, but not without a twist first—the persona admits in line 10 that he “cannot bear to ascend the height” and look afar. But this is exactly what he does in lines 11 and 12. From the vantage point of a balcony, he watches, at a time of year when things are decaying, the Yangtze River and lets its eastward-flowing water carry his thoughts to his faraway homeland. Careful readers might have noticed that this segment is preceded by the leading word “[I] look” (line 11). Actually, the next segment (lines 13–14) and the segment that follows (lines 15–16) also begin with leading words, while the concluding segment (lines 17–18) opens with a multisyllabic leading phrase, “How could she know.” These leading words not only mark the juncture points in the development of the persona’s emotions and feelings, but, more significantly, also point out or foretell the direction of his perceptions and thoughts: after what happens in the first stanza, where the poet’s mood is affected by his multifaceted experience of autumn, he looks (wang) afar and becomes homesick; he then retreats into himself, sighing (tan) over his situation. The longing and regret cause his thoughts to again go out and into the far distance, and he imagines (xiang) that his “fair one,” in another place and from another balcony, is at that moment looking at the Yangtze and waiting for his return. Finally, he gives another spin to what he sees in his mind’s eye, wondering how could she know (zheng zhi wo) (but she should!) that exactly at that moment, from the balcony on his side, he is also facing the same eastward-moving Yangtze and thinking about her.

Thanks to the colloquial tone of the leading words and the irregular beats they add to the syntax, the flow of the poet’s thoughts is carried by a rhythmic and flexible sound pattern. Leading words thus help give a material shape to the structure and order of Liu Yong’s poetic presentation. One might feel that his leading words function like stage directions and make the poetic acts and situations explicitly clear, perhaps too clear. However, Liu seems to have found a way to make his plainness sophisticated. In the poem, his presentation is linear yet by no means flat. With the help of the leading words, it explores time and space, involves things far and near, part and whole; it weaves what is outside with what is inside, and even shifts between here and there, this and other. The reflective twist and turn in the latter half of the second stanza is extremely clever: there is only one Yangtze River, but there are two balconies.

In his studies of the contributions of the song lyric to the formal evolution of Chinese poetry, Yu-kung Kao has highlighted some basic differences between the generic formal features of the regulated verse and of the song lyric. According to Kao, in the regulated verse, the poetic self is the source as well as the content of the poetic process.2 The single vision of the “lyrical self” at the “lyrical moment” of here and now shapes the poetic act, which takes the form of a four-couplet structure. A poet often uses the opening couplet to introduce the poetic situation, the two couplets in the middle to present the direct and immediate impressions from his observation of things and events, and the concluding couplet to reveal the inner state of the lyrical self.

The case is different with the song lyric. The basic structural unit of the song lyric, especially in its more sophisticated manci form, is not the couplet but the strophe.3 What the strophe is to the song lyric is comparable to what the couplet is to the regulated verse. A strophe consists of an indefinite number of lines that share a center of focus.4 Such a strophic unit can therefore be called a concentricity. As each line in this unit can describe things or narrate events “from a different angle or at a different point in time, involving various kinds of mental activities in addition to sense impressions, the structure can also be called one of ‘stratification.’”5 This structure of concentricity and stratification works at more than one level. While each strophic unit has its own center, all the units within a song lyric have a common center at a higher level. In this way, the whole song lyric is sustained by an “incremental structure.”6

Looking again at Liu Yong’s lyric, we can see this incremental structure at work. The four steps in the poet’s presentation of autumn in the first stanza and the four segments in the second (altogether eight beats as the tune title indicates) are all strophic units. Each of them captures a particular moment in a series of poetic events, representing one stage in the development of the theme. Working as a whole, and with the help of the stanzaic division, they allow the poet to unfold his description of scenery and narration of inner activities step by step. It is fair to say that Liu Yong’s creative use of leading words in the manci marked the beginning of the literati ci poets’ conscious experiment on the multifaceted structure; such utilization of leading words eventually became the most important aesthetic feature of the genre.

Just as Liu Yong introduced exciting innovations to the techniques of the manci, Su Shi expanded its thematic scope. Su Shi’s manci lyrics prove that the ci could be skillfully used to express sentiments that were generally thought to be suitable only for shi poetry.7 Moreover, the formal properties of the manci provided him with powerful poetic devices that could be used to convey personal feelings and emotions that were too intense and too exquisite to be fully expressed in shi poetry.8 As a result, not only did he further expand the subject matter of manci, but he also gave many of his songs a genuine personal voice, an unambiguous autobiographical tone as found in traditional shi poetry.9 He was sometimes accused of ignoring the intrinsic musicality of the ci, but, at his best, the spontaneous flow of his thoughts and feelings unfold with a natural ease and fit comfortably the syntax and the phonetic modules of the manci tunes, which had developed from the sound patterns that Liu Yong had discerned in the performances of the popular musicians and singers half a century before.

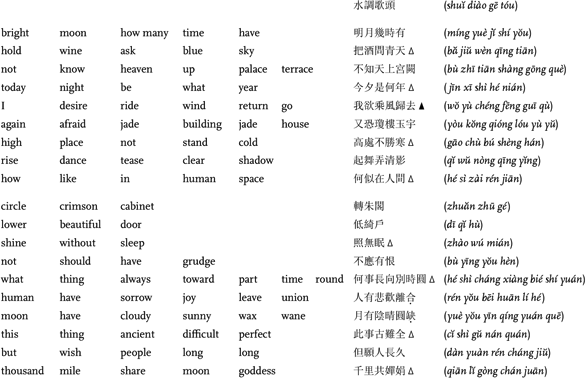

To the Tune “Prelude to the River Tune”

On the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival of bingchen [1076], I enjoyed drinking until dawn—I got completely drunk. This piece was composed for the occasion and also to express my thoughts for my brother Ziyou.

For how long has the bright moon been there?

2 I hold up the wine cup and ask the blue sky.

I wonder in the palaces in heaven

4 What year tonight is.

I wish to ride the wind and return there,

6 But fear the crystal towers and jade galleries

So high up there would be too cold for me.

8 I rise to dance with my solitary clear shadow,

How does this compare to the human world!

10 Going round the crimson hall,

Creeping in through the decorated doorway

12 It shines on the sleepless me.

I should not owe it any grudge

14 Then why would it always turn full when we are separated?

Men are sad now, joyous then, because of parting and reunion;

16 Moon cannot but wane and wax, wax and wane.

Things can never be perfect.

18 I only hope we will both live long,

And, while a thousand miles apart, share the same moon’s beauty.

[QSC 1:280]

The first thing of note in this poem is its opening comments, which tie the song to a specific occasion and lend it a genuine personal voice. Su Shi was the first to introduce this common practice of classical poetry into the writing of a song lyric.

When he wrote this piece, Su Shi no doubt had in mind a poem by the great Tang poet Li Bai (701–762), “Questioning the Moon with Wine Cup in Hand.” Commentators have also pointed out the link between Su Shi’s opening question and the “Questions for Heaven” (Tian wen) posed by Qu Yuan (340?–278 B.C.E.) more than a thousand years earlier. The echo across history adds an extra dimension to the existential quest in this song: a millennium of earnest human search in the face of the indifference of eternity. The awe and puzzlement felt by the poet is carried not so much by the question itself as by the yearning posture of one individual in the middle of the night facing the infinite openness of the sky, wishing to reach to the bottom of the cosmic truth.

The tension created at the very beginning between inquisitive humankind and the mysterious universe continues in the interaction between the poet and the moon. The moon of mid-autumn is generally believed to be the brightest of the year, and on that night it has such a great allure for the poet that he hopes to “return” to it (line 5), as though his origin were in the otherworldliness of that heavenly body. (The Daoist implication is detectable in the wind-riding image borrowed from two Daoist texts, the Zhuangzi and the Liezi.) However, he instantly hesitates, fearing that the palaces high up there might be too cold for him (lines 6–7). His uncertainty about where he belongs is expressed in the ambiguity of the last two lines of the first stanza. When he dances with his own shadow in a half-drunken state under the ethereal moonlight, he feels suspended above the human world; hence his uttered question “How does this compare to the human world!” (line 9). But a totally different reading is also possible: he gives up his thoughts of flying to the moon and finds satisfaction in pleasing himself on earth: How can anything compare with this human world? The ambiguity seems to be deliberate; it suggests the mumbling of someone who is completely drunk and fits the pattern of the poet’s oscillating thinking that we have seen so far.

The communication between the poet and the moon is actually a one-man show. The poet thinks out loud, reasoning with himself, yet he stages his monologue in a dramatic situation in which he reaches out to the moon and tries to engage it in a dialogue. The fact that the moon appears to be a reluctant interlocutor only adds to the dramatic effect. Its silence prompts further questions, reflections, and doubts from the poet and gives him an excuse to continue his philosophical rambling. This small drama continues in the second stanza. While what really happens is that the sleepless poet watches the moon and follows its slow movement (lines 10–12), he describes the situation in such a way that it appears as though the moon has come to disturb him and caused his sleeplessness. Instead of admitting his oversensitivity to the subtle changes in nature, the poet accuses the moon of always making him feel the pain of separation (lines 13–14). Then he changes his mind. He forgives the moon and uses the occasion to theorize his new understanding of the inevitability of the human situation (lines 15–16). The originally pensive mood changes. The song ends on a positive, even optimistic note.

This second song lyric by Su Shi is a good example of how the poet adapted the conventional subjects of classical poetry to the manci form:

To the Tune “The Charm of Niannu”:

Meditation on the Past at Red Cliff

The Great Yangtze runs east,

2 Its waves have swept away heroes of past ages.

Lying to the west of the old fort, it is said,

4 Is the Red Cliff, known because of Zhou Yu of the Three Kingdoms.

Rugged stone walls pierce the sky.

6 Angry waves beat the banks,

Churning up water like piles of frosty snow.

8 The mountains and the River look like a painting,

And how many heroes were once here!

10 Thinking far back, I see Zhou Gongjin,

With Little Qiao as his new bride,

12 Beaming with valor.

He has feather fan in hand and is in silk headdress, and while chatting merrily,

14 The powerful enemy vanishes in flying ash and smoke.

My mind wandering over the old kingdom,

16 I become so sentimental that one may well laugh at me:

Too early have gray hairs crept onto my head.

18 Life is like a dream,

So let me offer this cup to the moon over the river.

[QSC 1:282]

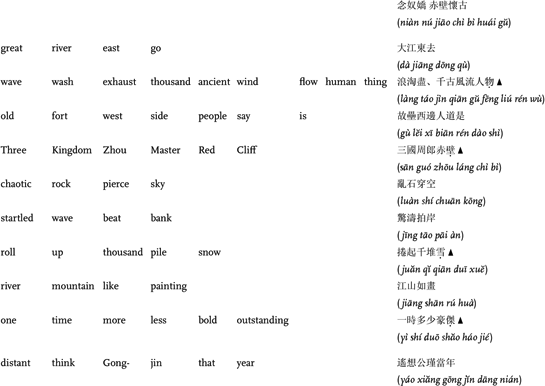

The poet wrote this meditation on the past when he came to an ancient site on the banks of the Yangtze thought by many to be Red Cliff, where a formidable fleet led by Cao Cao (155–220) from the kingdom of Wei was wiped out in 208 by Zhou Yu (Zhou Gongjin, 175–210), the commander of the army of the kingdom of Wu. The decisive battle prevented Wei from annexing Wu and another kingdom, Shu, and ushered in the Three Kingdoms period (220–280).

The song begins with a sigh: even those heroic figures could not avoid being swept away by the eastward-flowing Yangtze! The theme of ubi sunt is expressed through the poem’s images. Compared with the awe-inspiring “painting” (line 8) of nature in the first stanza, human existence appears ephemeral and human efforts insignificant. The “rugged” cliffs and “angry waves” of the great river are as real and threatening as they appear immediately before the poet’s eyes (lines 5–7), while heroes of past ages have been reduced by time to insubstantial hearsay—“it is said” (line 3)—nowhere to be seen. The conclusion of the first stanza has a ring of both irony and sentimentality. Where are those heroes who “once” (line 9) competed with each other here for the control of the mountains and the Yangtze River?

In the second stanza, in his spiritual wandering over the “old kingdom” (line 15), the poet sees General Zhou Yu, one of those heroes. It is interesting to note that although Zhou Yu was a warrior “beaming with valor” (line 12), who made his enemies vanish in “ash and smoke” (line 14), he is also depicted as a scholar, with a “feather fan” and “silk headdress” (line 13). The mention of his newlywed and legendarily beautiful wife reveals his own youthful charm, and his graceful composure in the face of an overwhelming enemy shows his mental and intellectual capability rather than his military prowess. Many traditional commentators and modern scholars have expressed the belief that the poet nostalgically projects himself—a scholar—into the image of Zhou Yu. This reading makes sense when one considers that autobiographical reflection brought forth by a meditation on history is one of the important elements of a poem of this type. Internal evidence from the song itself, however, supports a different interpretation. The gentler, intellectual side of the image of the young general, in contrast with the image of nature depicted as “rugged” and “angry” in the first stanza, foregrounds the vulnerability of humankind. Human life is beautiful yet evanescent, created only to be swept away. The juxtaposition of the young general so vividly called forth in the poet’s reflections of the ancient hero, long dead, with the living yet rapidly decaying gray-haired poet lamenting the past (line 17) expresses the poet’s perplexity over the inscrutable and devastating power of time. Indeed, the almost perfect image of the young general—whose link with the present is barely maintained in such terms as “it is said” and “once”—is an illusion embedded in a distant time frame. As the poet tells us, in order to see his hero, he has to think “far back” (line 10) into the past. Not unexpectedly, the poet ends his spiritual journey with the melancholy sigh that life is but a dream (line 18) and offers his “cup to the moon over the river” (line 19). In Chinese, the phrase can also be read as “the moon’s reflection in the river,” symbolizing the illusoriness and intangibility of human existence.

The next ci poet to be discussed is Li Qingzhao, one of the most prominent female figures in the history of Chinese poetry. Her sensitive heart, keen eye, and musical ear lend her manci works an unusual psychological depth:

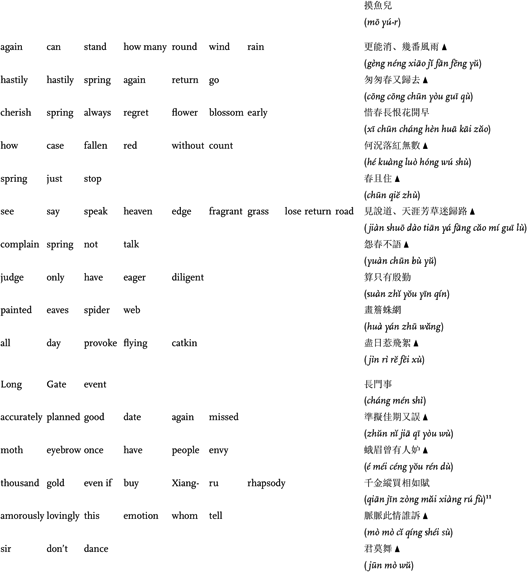

To the Tune “One Beat Followed by Another, a Long Tune”

Searching and searching, seeking and seeking,

2 Chilly and cold, quiet and desolate,

Sad, sorrowful, miserable.

4 This time of year when it’s warm now, soon cold again,

I just cannot take care of myself.

6 Two or three cups of bland wine

Are not enough to resist the rushing evening wind.

8 The wild geese passing by

Break my heart,

10 And they are none other than my old acquaintances!

In piles chrysanthemums are everywhere.

12 Withered and damaged;

Now who will pick them?

14 I cling to the window;

All alone, what am I going to do before it gets dark?

16 The drizzle on the wutong leaves

Drips and drops, drops and drips into evening.

18 How can all this

Be summed up by one word, “sorrow”?

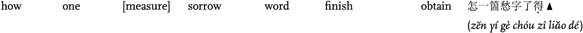

[QSC 2:932]

The tune title of this piece (“Shengsheng man”) tells part of the story—a manci with doubled sounds. The poem is best known for its beginning. Readers need only look at the transliteration and word-for-word translation to experience the expressiveness of the fourteen doubled dental and labiodental sounds. The two verbs in line 1 are synonyms, as are the two adjectives in line 2 and the three in line 3. The repeated words form a three-line enjambment of sounds charged with meaning. The repetition of “searching” and “seeking” (line 1) not only prolongs the action but also implies its futility. The poet finds nothing but coldness and loneliness hemming her in (line 2). This brings in endless sorrow, reiterated six times in a triple doublet structure in line 3.

The fourteen syllables in the first three lines summarize the situation the poet finds herself in and foretells what follows in the poem. No matter what she does, she cannot escape from sorrow. She tries to repel the autumn wind (line 6), but she knows that her effort is futile (line 7). The wine is not strong enough to resist the autumn chill, nor can it help her forget her sorrow. Inaction also proves ineffective in driving away sorrow: “wild geese” fly overhead (line 8). Wild geese, long acting as messengers between loved ones and friends in Chinese literature, here serve only to make the poet painfully realize that their service is no longer needed (it is generally believed that this song was written after the poet’s husband died in 1127). Her recognition of the flock as “old acquaintances” intensifies the pain (lines 9–10). Their reappearance brings back memories of people and events from her past and brings to her attention the cyclic change of the seasons. Her heart breaks.

The second stanza continues the motif of the seasonal changes. Like the wild geese, the withering chrysanthemums remind the poet once again that this is the time when everything decays (lines 11–13). In the damaged flowers she sees herself. She is no longer in her prime, and what remains of her life will be wasted in solitude. There seems nothing else for her to do but to just “cling to the window” (line 14). In fact, this appears to be what she has been doing all day long: with a cup in her hand, she sits listlessly there, allowing the passing wild geese and the dying flowers outside the window to torture her heart. Her fear and despair express themselves fully in the exclamation in line 15: How can she drag out the day like this? Behind this exclamation is not ennui but a dread of the life she is living. She is so afraid of the futility of her searching and seeking and all that meets her eye that she cannot wait for the night, the darkness, to come. But even she herself knows that darkness will not bring her solace. The autumn rain on the wutong leaves has been falling all afternoon and promises to extend into the night (lines 16–17). The dripping and dropping of the rain—mimicked by the four onomatopoeic syllables beginning with a “d” sound—like that of tears, echoes the sound repetition of the beginning of the song, suggesting that the sorrowful sigh that opens the song does not stop but goes on all the way through to the end.

The whole piece can be summed up by one word, “sorrow.” As we have seen, the poet emphasizes this at the beginning by repeating the idea of sorrow six times in line 3. Now, at the end of the song, she tells us that the word “sorrow” just cannot express what she has tried so hard to say. Suddenly the poet sounds like Zhuangzi (ca. 369–286 B.C.E.), the language skeptic who wished that he could “have a word” with someone “who had forgotten words.”10 However, the poet has also inherited Zhuangzi’s dilemma. She has no other medium but language, ironically, even when she wishes that her readers would bypass language. Her best hope is that some kind of unmediated grasp of her sentiment can be achieved by those readers who are willing to go beyond language and try to experience what her words attempt to convey. Seen in this light, her unconventional use of sounds at the beginning of the song can be read as a direct appeal to readers’ sensual, rather than simply intellectual, perception.

The last ci master we consider here is Xin Qiji, the most prolific ci writer in the Song dynasty. Together with Su Shi, Xin Qiji has been labeled as a representative of the school of “heroic abandon” (haofang), as opposed to that of “delicate and restrained” (wanyue). But his art defies such an oversimplified categorization. This first poem no doubt reveals his heroic side, yet the style of the second is hard to pin down if mention of “delicate restraint” is forbidden:

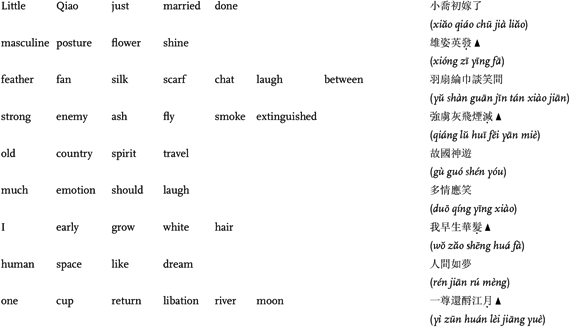

To the Tune “Congratulating the Bridegroom”

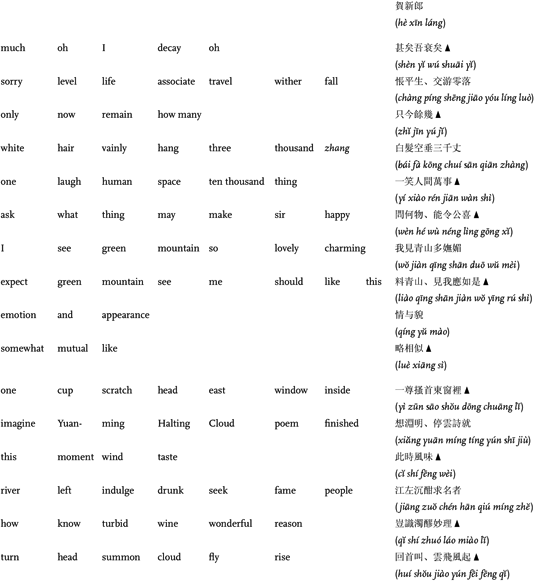

I have composed songs to the tune of “Hexinlang” for all the gardens and pavilions in my district. One day when I was sitting by myself at the Halting Cloud Pavilion, the gurgling streams and green mountains vied with one another to please me. Presuming that they also wanted me to write something for them, I put down a few lines. They might bear some resemblance to Tao Yuanming’s poem “Halting Clouds,” in which he expresses his longing for his friends.

Too much I have decayed!

2 Alas, all my life I’ve seen friends and companions fade away,

And now how many of them are left?

4 With gray hair hanging in vain three thousand zhang long,

I laugh away all worldly things.

6 Is there anything left, you ask, that might cheer me up?

I see in green mountains such alluring charm;

8 I expect that they see the same in me,

For in heart and in appearance

10 We are a bit similar.

Goblet in hand, scratching my head by the east window,

12 I presume that Tao Yuanming, having finished his poem “Halting Clouds,”

Was in the same mood now I am.

14 Those on the south side of the Yangtze who got drunk only to seek fame,

How could they know the magic of the turbid wine?

16 Looking back, I conjure a gust of wind and send clouds flying.

I regret not that I can’t meet the ancients,

18 But that the ancients had no chance to see my wildness.

The number of people who understand me

20 Is no more than two or three.

[QSC 3:1915]

The poet’s arrogant reference to the “ancients” in lines 17 and 18, close to the end of the song, is a clever adaptation of an earlier text. As recorded in the Nanshi (History of the Southern Dynasties), Zhang Rong (444–497), a literary prodigy of the Southern Dynasties (420–589), once bemoaned that he had been born too late to compete with the ancients: “I regret not that I can’t meet the ancients; what I regret is that the ancients had no chance to meet me.” Now, seven hundred years later, when Zhang Rong himself had become an “ancient,” Xin Qiji has appropriated his voice. The only word he added in recasting the earlier text was kuang (wildness, arrogance). Obviously, he believed that his most valuable asset was being wild and arrogant, and his wish was that his wild quality be fully appreciated. But what does this wildness really mean?

A casual reading of the song shows that the poet is saddened by his own aging and the passing away of his friends, and yet, in mocking his long gray hair, he accepts his lot with a sense of humor. He finds solace in nature and, of course, knows the true taste of wine. Judging from these stock poetic gestures, it seems that what the poet celebrates is the wildness of a hermit.

The poet is not, however, a hermit. He is not another Tao Qian (Tao Yuanming, 365?–427), the well-known recluse-poet (chap. 6) to whom Xin Qiji likens himself in the second stanza. The assumed philosophical calmness can hardly conceal the struggle of a restless spirit, which is wild in a totally different sense of the word. Even early in the song, in the first stanza, where the “I” makes every effort to take things lightly and express himself calmly, one can sense the conflict between his superficial composure and his suppressed wild spirit. For example, after declaring that he can dismiss all “worldly things” with a laugh (line 5), the poet asks himself the rhetorical question whether there is anything left that might make him happy (line 6). The answer is yes. The “alluring charm” of the “green mountains” greatly pleases him (line 7), and he “expects” that he would be very charming in the eyes of the charming mountains (line 8). One should note that this is not a simple case of “pathetic fallacy.” The poet puts in the mouth of the green mountains a eulogy on himself and makes them a medium through which his ego finds self-gratifying confirmation. It thus becomes clear that the “worldly things” that the poet wants to “laugh away” do not mean only worldly concerns but also all the mediocrity of the world. It is his contemptuous dismissal of the mediocre world that brings about the question: (Since you think nothing is worth mentioning in this world) “is there anything left … that might cheer” your heart? As we have seen, the poet begins by posing himself as a modest noncontender. He laments how much he has declined, claims that he is aloof from the world of fame and gain, and seeks solace in nature, as would a hermit. After listening to him more carefully, we find that each of his statements carries an overtone suggesting that he is far apart from the common herd.

The tension between the serene surface and the undercurrent of agitation continues in the second stanza. The image presented in lines 11–13 is taken from Tao Qian’s poem “Halting Clouds”: a lonely drinker, eager for his friend to come, scratches his head restlessly, just as that anxious lover in the Shijing (The Book of Poetry) does when waiting for his fair lass. With this image, the poet again assumes the air of a hermit and implies his longing for a true friend who understands him.

It is interesting to note that although this key image is borrowed from Tao Qian, the poet unabashedly takes it as his own. He does not want to say that it is he who resembles Tao Qian; instead, he “presumes” that Tao Qian would be in the same mood as he is now. This self-centered stance is not unlike that in the first stanza when he commandingly “expects” that the green mountains should consider him charming. He thus makes the “ancient” Tao Qian come to see him. He really wants to be admired in this way, for the “special flavor” he now “relishes” (the literal meaning of cishi fengwei [line 13]) is the thrill of being an elitist solitary drinker. The use of the phrase cishi fengwei shows how dearly he treasures this special moment: he wants to prolong and savor every bit of it.

This is also why, in lines 14 and 15, he snorts with contempt at “those on the south side of the Yangtze who got drunk only to seek fame.” The similar political and military situation of Tao Qian’s time and that of the Southern Song allows the poet to hint that those seekers of fame on the southern bank of the river also include his despicable contemporaries. What he really despises in them is not so much their craving for fame as their being undeserving of what they crave. “How could they know the magic of the turbid wine?” asks the vehement poet (line 16). For him, they have no right to pretend that they know the special flavor of being wild.

The irony is that while the poet jeers at those seekers of fame, he himself is one who grudgingly guards against potential sharers of the honor and fame that he gives himself. As if to manifest how different he is from the mediocre, he abruptly makes a high-flown gesture that has nothing to do with being a hermit: he threatens to “conjure a gust of wind and send clouds flying” (line 16), alluding to “Dafeng ge” (Song of the Great Wind), by the first Han emperor, Han Gaozu (Liu Bang, 256–195 B.C.E.), which is said to have been written during his ostentatious homecoming after having donned the emperor’s dragon robe.

What follows then is the stunning outcry, “I regret not that I can’t meet the ancients, / But that the ancients had no chance to see my wildness” (lines 17–18). The “ancients” become pitiable because they do not have the chance to see the poet’s “wildness”—his aggressive egotism. It is they, not he, who suffer a loss. When he ends the song with “The number of people who understand me / Is no more than two or three” (lines 19–20), the poet is not repeating his earlier lament that most of his friends have faded away; the two lines allude, rather, to a passage in the Analects where Confucius sighs, “No one knows me” (14:37), yet the poet changes it into a delightful exclamation of sudden enlightenment. The reason that only two or three understand him is that few people are on a par with him: he stands alone in this world, peerless.

The force of the poet’s sudden outburst of self-pride is enforced by the rhythmic tone of his utterance. To write in the ci form is to “fill in words” in the existing tune patterns. In this sense, a ci poet does not enjoy too much freedom. But Xin Qiji knows how to make the best of the existing tune patterns. He ignores, for example, the pause within line 18 dictated by the meter in order to allow his wild exclamation, which starts in line 17, to rush on almost without stop in a sequence of fifteen syllables. When this forward movement is abruptly halted and the whole piece brought to an end by the two brisk three-syllable lines, we cannot but feel the tension resulting from the sudden halt of this onward force and from the confidence and certainty carried by these terse closing lines.

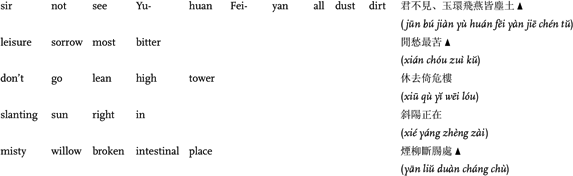

If the song lyric examined in the preceding poem exemplifies Xin Qiji’s heroic style, the following one demonstrates that he was also capable of a very different kind of poetic voice, one marked by delicacy and restraint:

To the Tune “Groping for Fish”

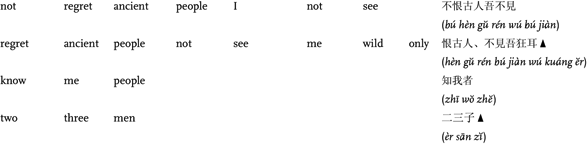

In the sixth year of chunxi [1179], I was transferred from the post of assistant fiscal intendant of Hubei to that of Hunan. This song was written at the farewell party given by my colleague Wang Zhengzhi at the Small Hill Pavilion.

How many more winds and rains can it withstand?

2 In such a hurry, again spring is leaving.

So dear I hold vernal times that I have always been afraid that flowers would bloom too soon,

4 And how can I bear to see countless fallen petals?

Spring, just stay for a while longer.

6 It is said that fragrant grasses have spread over the end of the earth and blocked your way home.

Why didn’t you say a word?

8 I only see the spider’s enticing webs,

Under painted eaves,

10 All day long, flirt with flying catkins.

What a story about the Tall Gate Palace!

12 Another carefully planned reunion is upset.

Charming beauty did invite jealousy.

14 Even if a beautifully worded letter can be procured with gold,

To whom can I deliver this tender heart?

16 You, do not dance!

Have you not seen how those favored beauties fall to dust?

18 The bitterest is lonely grief.

So do not lean against the high balustrade,

20 For it is there that the sun goes down

Amid the heartbreaking misty willows.

[QSC 3:1867]

In this song, the persona laments, through a female voice, the passing away of spring and the wasting of the spring of her life. But even a casual reading reveals that this is allegorical poetry. The true reason for the persona’s fret is found in line 13: “Charming beauty did invite jealousy.” Judging from the information provided in the prefatory comments, it is probable that the composition of the song was prompted by the poet’s reflection on certain unpleasant experiences in his political life.

The song begins with the persona voicing her worry about the inevitable—that spring is “again” (you) going away (line 2). The phrase “how many more” (line 1)—expressed by geng (still, even more) and jifan (several times) in the original—indicates that the persona has been watching closely the coming and going of the “winds and rains” and is deeply troubled by their devastating effects on the delicate spring. She has “always [chang] been afraid that flowers would bloom” too early and fall too soon (line 3). No doubt the “countless fallen petals” on the ground are too much for her (line 4).

She pleads with spring to stay, employing her persistent, although poorly argued persuasion (lines 5–7). The tone of her voice is not demanding, merely entreating. The uncertainty and hesitation of her voice are suggested by the qualifying tone of the word qie (just, why not) (line 5) and the phrase jian shuo dao (it is said) (line 6). The stupidity of her attempt to talk spring into coming back and her grumbling that spring gives her no response tell us not only how distraught but also how guileless she is. The image of a fair lady with a delicate heart is instantly established. The series of well-conceived time-measurement words and phrases—you, geng, jifan, chang, and others—vividly portray a feminine subject extremely susceptible to outside stimuli. The three verbs related to this tender and sensitive subjectivity—xi (to hold dear, pity), hen (to regret), and yuan (to complain)—are all tinged with emotional fragility.

As her monologue continues in the second stanza, the fair lady divulges the secret of her sorrow by alluding to a story about a royal consort of Emperor Wu of the Han (r. 140–87 B.C.E.) who managed to regain her lord’s favor by asking the best-known literary talent of the day to write on her behalf a moving rhyme-prose to the emperor. Here, however, the poet has changed the consort’s success story into a tragedy: the long-cherished hope of the miserable consort to regain the favor of her lord is dashed by the slander from her jealous rivals. How deep her disappointment and how keen her heart’s pains are can be read from the carefully chosen words zhunni (well planned) and another you (again, once more) (line 12). Such careful planning and breathtaking anticipation are frustrated once again, and despair ensues. She seems to suggest that she would rather give up, since, even if she could have a moving letter written, there seems no way for her to find its recipient. Her heart, so tender, has no one to pour (su) itself out to (line 15).

The tender female voice speaks throughout (or almost throughout) the song. The disquieting late-spring scene—fallen petals, spiders’ webs under eaves, setting sun—is seen through the sensitive female eye. The allusion that links the two parts of the song lyric delineates the distress of a tender heart wounded by neglect. All these elements seem to work together to sustain a coherent story line.

The almost flawless story line of the song and the consistent voice scheme are disrupted, however, by the discordance created by the middle segment of the second stanza (lines 16–17). The segment consists of an imperative (line 16) and a negative interrogative (line 17). Both are bluntly directed at a second person, a jun (you or sir). Usually used as a form of polite, honorific address, jun here functions specifically as the target of the poet’s contempt and hatred. “Sir,” commands the poet, “do not dance!” The contrast between the apparently polite and respectful form of address and the content of this imperative is so great that it not only reveals the poet’s anger but also carries a threat. To make sure that the threat is not taken lightly, the poet launches yet another round of attack: “[Sir,] have you not seen how those favored beauties fall to dust?” The emphatic power of the negative interrogative is so forceful and aggressive that it can be taken only as an unforgettable follow-up to the foregoing threat.

If we read this sudden outburst of emotion in context, we see that it could never be expressed by the voice of the fair lady, gentle though sometimes grumbling, with which we have become familiar. Although the persona’s tone gets bitter at the beginning of the second stanza, it is still restrained. Her bitterness comes not so much from her hatred of those who envy her as from her regret that there is no way to make her tender feelings known. The word zong (even if [line 14]) reveals the helplessness and resignation implied in the rhetorical question in line 15. The lady does not show any sign of anger even at the end of the song. It seems that she prefers to keep all the suffering to herself; sorrow and bitterness are carefully held at the tip of a well-trained tongue.

Then suddenly, a new voice, forceful and aggressive, breaks out from the plane of this story line and claims a new level of meaning of its own. The tension between the two planes has its merits. It is not that it helps bring out the allegorical meaning of the poem, which is already clear enough. Rather, the true self of the poet intrudes into the allegorical process of the song he so carefully presents, and speaks in a different voice, appealing to his readers with the immediacy and intensity of his message. Here perhaps lies another merit of the juxtaposition of the two planes of meaning. By displaying the evident conflict between the two voices, the poet deliberately shows how hard he tries, although in vain, to restrain his pent-up emotions. The poet’s candor is tricky and his naïveté a pretense, because they are part of his design. What is most noticeable in this design is his overdoing of an otherwise well-wrought allegory. The poet cannot wait for the implied meaning to emanate naturally from the metaphor of his story line. Instead, with the sudden outburst of emotion in the middle of the second stanza, he impatiently calls his readers’ attention to the message his allegory carries.

NOTES

1. For a detailed discussion of Liu Yong’s use of lingzi, see Kang-i Sun Chang, The Evolution of Chinese Tz’u Poetry: From Late T’ang to Northern Sung (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980), 123–133. See also Shuen-fu Lin, “The Formation of a Distinct Generic Identity for Tz’u,” in Voices of the Song Lyric in China, ed. Pauline Yu (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 20–21, and Stuart Sargent, “Tz’u,” in The Columbia History of Chinese Literature, ed. Victor H. Mair (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 319.

2. Kao Yu-kung, “Xiaoling zai shi chuantong zhong de diwei” (The Place of Xiaoling Lyrics in the Poetic Tradition), Cixue 9 (1992): 17.

3. Shuen-fu Lin was the first to employ this Greek prosodic term, which literally means “act of turning” and hence a division of a poem, to refer to a structural unit in a song lyric (The Transformation of the Chinese Lyrical Tradition: Chiang K’uei and Southern Sung Tz’u Poetry [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978], 106–107).

4. Kao, “Xiaoling,” 17.

5. Kao, “Xiaoling,” 17.

6. Kao, “Xiaoling,” 18–19.

7. Lin, “Formation of a Distinct Generic Identity for Tz’u,” 22–24.

8. Ronald C. Egan, Word, Image, and Deed in the Life of Su Shi, Harvard-Yenching Studies, vol. 39 (Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, and Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1994), 326–327.

9. A detailed discussion of this issue can be found in Egan, Word, Image, and Deed, 315–317, 322–330.

10. The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968), 302.

11. Although the last character of line 14, fu, fits into the rhyme, it is not marked as a rhyming character because its position is designated as ju (unrhymed) in standard rhyme books.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Chang, Kang-i Sun. The Evolution of Chinese Tz’u Poetry: From Late T’ang to Northern Sung. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980.

Cheng, Ch’ien. “Liu Yung and Su Shih in the Evolution of Tz’u Poetry.” Translated by Yinghsiung Chou. In Song Without Music: Chinese Tz’u Poetry, edited by Stephen C. Soong, 143–156. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1980.

Egan, Ronald C. Word, Image, and Deed in the Life of Su Shi. Harvard-Yenching Studies, vol. 39. Cambridge, Mass.: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, and Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1994.

Fong, Grace S. “Persona and Mask in the Song Lyric (Ci).” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 50, no. 2 (1990): 459–484.

Hightower, James R. “The Songwriter Liu Yung: Part 1.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 41, no. 2 (1981): 323–376.

———. “The Songwriter Liu Yung: Part 2.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 42, no. 1 (1982): 5–66.

Kao, Yu-kung. “Chinese Lyric Aesthetics.” In Words and Images: Chinese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting, edited by Alfreda Murck and Wen C. Fong, 47–90. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Lian, Xinda. The Wild and Arrogant: Expression of Self in Xin Qiji’s Song Lyrics. New York: Lang, 1999.

Lin, Shuen-fu. “The Formation of a Distinct Generic Identity for Tz’u.” In Voices of the Song Lyric in China, edited by Pauline Yu, 3–29. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

———. The Transformation of the Chinese Lyrical Tradition: Chiang K’uei and Southern Sung Tz’u Poetry. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Liu, James J. Y. Major Lyricists of the Northern Sung, a.d. 960–1126. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Lo, Irving Yu-cheng. Hsin Ch’i-chi. New York: Twayne, 1971.

Owen, Stephen. “Meaning the Words: The Genuine as a Value in the Tradition of the Song Lyric.” In Voices of the Song Lyric in China, edited by Pauline Yu, 30–69. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Sargent, Stuart. “Tz’u.” In The Columbia History of Chinese Literature, edited by Victor H. Mair, 314–336. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

CHINESE

Huadong shifan daxue Zhongwen xi gudian wenxue yanjiushi 華東師範大學中文系古典文學研究室, ed. Cixue lun gao 詞學論稿 (Research Papers on the Study of Song Lyrics). Shanghai: Huadong shifan daxue chubanshe, 1986.

Kao Yu-kung 高友工. “Xiaoling zai shi chuantong zhong de diwei” 小令在詩傳統中的地位 (The Place of Xiaoling Lyrics in the Poetic Tradition). Cixue 詞學 9 (1992): 1–21.

Leung Lai-fong 梁麗芳. Liu Yong ji qi ci yanjiu 柳永及其詞研究 (A Study of Liu Yong and His Song Lyrics). Hong Kong: Sanlian shudian, 1985.

Liu Yangzhong 劉揚忠. Xin Qiji cixin tanwei 辛棄疾詞心探微 (In Search of the “Heart” of Xin Qiji’s Song Lyrics). Jinan: Qi Lu shushe, 1989.

Miao Yue 繆鉞 and Yeh Chia-ying 葉嘉瑩. Lingxi ci shuo 靈溪詞說 (Talking About Song Lyrics by the Ling River). Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1987.

Shi Yidui 施議對. Ci yu yinyue guanxi yanjiu 詞與音樂關係研究 (On the Relationship Between Song Lyrics and Music). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue yuan chubanshe, 1985.

Tang Guizhang 唐圭璋, ed. Quan Songci 全宋詞 (Complete Song Dynasty Song Lyrics). 5 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1965.

Zeng Daxing 曾大興. Liu Yong he ta de ci 柳永和他的詞 (Liu Yong and His Song Lyrics). Guangdong: Zhongshan daxue chubanshe, 1990.