17

17

Shi Poetry of the Ming and Qing Dynasties

Poets in the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties continued to employ the major poetic genres of shi, ci, and qu. These two dynasties, commonly referred to as the late imperial period, witnessed the unprecedented spread of poetry writing among men and, for the first time in Chinese history, women. Numerous volumes of poetry were published, and many of them are extant. Poetry collections by women alone are recorded to be more than 3,000.1 The quantity of shi poetry that has survived greatly surpasses the some 200,000 poems from the Song (chap. 15), amounting to more than 1 million poems. No attempt has yet been made at the seemingly impossible task of compiling a complete collection, as has been done for the Tang and Song and earlier dynasties.2

The affluent period from the sixteenth century to the fall of the Ming in 1644 saw remarkable developments in commercial print culture and the spread of literacy and education to a wider public that crossed the previously stricter limitations of class and gender.3 This increase in literacy and the pervasive practice of writing poetry among an expanded community of men and women transformed the craft of poetry into a supple discursive medium for recording an extraordinary range of subjects and articulating autobiographical and everyday dimensions of experience. The continued, even increased vitality of the poetic medium in the Qing was an effect of the fervor with which individual women and men took up poetry as a technology of self-representation and as a tool of communication and social exchange. The majority of these writers necessarily have not been part of the received poetic canon. However, for the first time, the voices of individual women were no longer isolated instances, nor could women be ignored as they wrote themselves into history by means of poetry.4

Although no new prosodic forms were created in this period of extensive participation, the Ming and Qing are distinguished by dynamic developments in literary theory and criticism. Poetic theories ranged from those with formalistic concerns advocating Tang or Song poetic models for emulation, to those emphasizing spontaneous, natural expression in style and emotion. The theoretical writings and poetic practice of the most important poet-critics constituted influential literary trends both in their own time and in later periods, and these poets have, in turn, been constructed as canonical figures in literary history.5 While there may be some consensus regarding outstanding poets of the period, the sheer volume and variety of poetry militate against a common list of “masterpieces.” Difficult as it is to do justice to this relatively unexplored but extremely immense and rich field, this chapter aims to show Ming–Qing poetry as a multifaceted cultural practice by taking a two-part approach. First, I will discuss poems written by leading exponents of particular theories to illustrate schematically some of the major poetic trends in the Ming and Qing. Second, because the diversity and pervasiveness of poetry writing went beyond the elitist theoretical discourse on the art of poetry in this period, I will introduce important contexts for reading poetry as a commonplace, diurnal practice in the lives of men and women. These include the meaningful organization of individual poetic collections and the significance of the material conditions and historical specificities informing poetic production. The selections emphasize the fundamental function of poetry to inscribe life experiences in three categories of poems with contrasting but overlapping personal, social, and political contexts in the late imperial period: poems written during the disorder of the Ming–Qing dynastic transition in the mid-seventeenth century,6 poems that exemplify the pervasive autobiographical impulse in the poetic act, and poems that demonstrate the interest in recording personal experiences in everyday life. These contexts of poetic production foreground the sense of subjectivity and agency of the writers. We will see how, through poetry, men and women empower themselves with a capacity for action, even if that action may be limited to self-expression and the act of recording.

POETIC THEORY AND POETIC PRACTICE

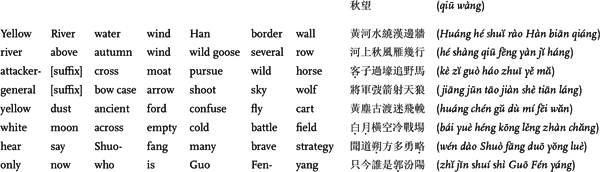

The first important literary movement to arise in the Ming was the Archaist school represented by the Former Seven and Latter Seven Masters, many of whom were scholar-officials in government. Its influence dominated the poetic scene in the sixteenth century, particularly in the capital, Beijing. The Archaist poets advocated emulation of poetic models from the past, specifically the Tang. The best-known leader, Li Mengyang (1475–1531), one of the Former Seven Masters stated famously that when it came to ideal models, “prose must be that of the Qin and Han, and poetry must be that of the High Tang.”7 They rejected Song poetry for its discursiveness and sought to imitate the grand, expansive vision, affective intensity, and perceptual qualities embodied in the allusive diction and powerful imagery of Tang verse, particularly those found in the poetry of Du Fu (712–770). The following widely anthologized heptasyllabic regulated poem by Li Mengyang exemplifies these characteristics:

The Yellow River winds around the Han frontier walls,

2 Over the river in the autumn wind, a few lines of wild geese.

The attackers crossing trenches pursue on wild horses,

4 The general with his bow case and arrow shoots at the Heavenly Wolf.

Yellow dust by the ancient ford confuses the swift chariots,

6 White moonbeam across the void chills the battleground.

Up north in Shuofang there were many bold plans, they say,

8 Only nowadays where is there a Guo Fenyang?

[MSBC, 717]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 172]

The northwestern frontier became a popular theme in High Tang poetry, attending the military expansion of the empire.8 In the Ming Archaist valorization of Tang models, the frontier theme was often taken up by both male and female poets as a literary exercise and, in some cases, as poetic records of actual expeditions. By its very subject matter, the frontier topos lends itself to capturing the strength and vigor of Tang poetry. The title of the poem, “Autumn Gaze,” sets up the anticipation of a seasonal view. Li Mengyang skillfully deploys Tang poetic conventions to re-create the broad expansive prospect of the border region. The opening couplet begins with the scene of a vast horizon suggested by the view of the Yellow River meandering along the Great Wall of the Han dynasty, using the conventional temporal displacement to the past employed in Tang poetry. The visual trajectory is directed upward to the sky by the image of wild geese migrating south, seen as distant lines above the riverscape. The two required parallel couplets in the middle each form perfect syntactic, semantic, and tonal contrasts (lines 3–4 and 5–6). These formal symmetrical structures further elaborate on details of the frontier. In an offensive attack, the non-Chinese nomadic tribes, riding on horses, cross the defensive moats into Chinese territory. Li Mengyang cleverly employs the term “wild horses,” an allusion for rousing energy (qi),9 to create the spectacle of nomadic attackers galloping across the dusty desert. This invasion is countered by the force of the defensive act of the Han general aiming his arrow at the “Heavenly Wolf” (the star Sirius), here standing for the “barbarians.” The scene depicted in this couplet with such vivid imagery, as though witnessed by the poet, is temporally ambiguous, suspended between past and present in the poet’s imagination. It is an imagined battle scene in the past triggered by the poet’s arrival at the frontier. Its pastness is reinforced in the next couplet by the timeless quality of the “ancient ford,” enduring moon, and deserted battleground frozen in history. Only with the rhetorical question in the closing couplet, in which the poet follows the desired move to the affective mode in regulated verse, does he articulate his admiration for the military glory of the Tang and his present doubts by alluding to Guo Ziyi (697–781), the Tang military commissioner of the Shuofang commandery where the poet was at the time of the poem. Guo Ziyi was one of the leading loyalist generals who helped defeat the rebellion started by An Lushan (d. 757) under the Tang emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756). He was enfeoffed as prince of the Fenyang commandery for his efforts to save the Tang and was referred to as Guo Fenyang in later periods. This poem is an esteemed emulation of Tang poetics.

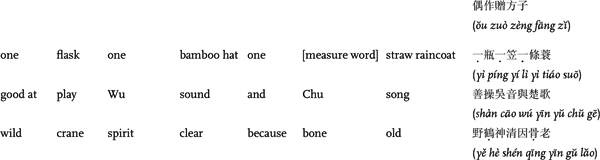

In the Archaist desire to emulate Tang diction and imagery, the individual voice of the poet is often suppressed, and the less successful efforts resulted in turgid and uninspired formalistic pieces. Toward the end of the sixteenth century, a strong opposition to Archaist practices arose, spearheaded by Yuan Hongdao (1568–1610) and his two brothers—Yuan Zongdao (1570–1626) and Yuan Zhongdao (1560–1600)—that came to be known as the Gong’an school after their native district in Hubei. Yuan Hongdao emphasized individual expression and the use of natural and simple language. He famously pronounced that poetry should “only express one’s natural sensibility [xingling] and not be restricted by conventional form.”10 In emphasizing the expression of genuine feelings in simple language, Yuan Hongdao valorized folk songs and village ditties. He also commended Song poetry, anathema to the Archaist school. The poetic language he adopted tends toward the colloquial and easy, the diction being less formal and allusive. The heptasyllabic regulated poem he sent to a friend exemplifies these characteristics:

Composed at Random: Sent to Master Fang

With a flask, a bamboo hat, and a cape of straw,

2 I am skilled at playing Wu melodies and Chu songs.

The wild crane’s clearheaded because its bones are aged,

4 Mandarin ducks gray together because their love is deep.

Pendants worn at the waist are antiques a thousand years old,

6 The topsy-turvy script written when drunk are waves ten yards long.

Recently in making verse I have become more attentive,

8 When it comes to long lines every time I study Dongpo.

[YHDJJJ 2.540]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 172]

Yuan Hongdao’s use of the conventional title “Composed at Random” calls attention to the very casualness of the occasion of writing itself. The poem begins by projecting the image of a carefree rustic man, wearing a straw raincoat, enjoying himself with a bottle of wine, and making music. The melodies of Wu and songs of Chu are precisely the kind of regional folk tunes and ditties that he endorses as genuine poetry of the people. Even when Yuan Hongdao has to observe the strict rules of tonal antithesis and syntactic and semantic parallelism required in the regulated form, as in the second and third couplets, he avoids erudite language and allusive imagery. Instead, he draws on birds with common cultural associations to further highlight his natural inclinations. The crane, a symbol of immortality, is here the poet’s self-image—old but clearheaded. The mandarin ducks, a symbol of conjugal love, represent the poet’s depth of feeling and romantic devotion. In the third couplet, the antique pendants worn at the waist and the free-flowing calligraphy convey the literati culture in which Yuan Hongdao participates; their unique characteristics suggest his individualistic manner. In the closing couplet, the poet explicitly comments on his poetic practice—his turning to the more discursive style of the great Song poet Su Shi (style name Dongpo, 1037–1101), one of whose poetic trademarks is his carefree attitude and inimitable wit.

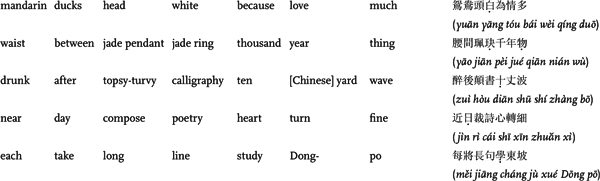

While Yuan Hongdao’s poetic theory proved to be a powerful antidote to the Archaist influence, his poetic practice did not merit much commendation by later critics. The early Qing critic Zhu Yizun (1629–1709) castigated the worst of Yuan Hongdao’s poetry for being vulgar, facetious, and flippant in expressing his unrestrained inclinations and feelings.11 Although not all above partisanship, poets of the late Ming and early Qing—such as Chen Zilong (1608–1647), Qian Qianyi (1582–1664), and Wu Weiye (1609–1672)—were prolific writers who produced poetry that stood on their own merits. Chen Zilong infused his poetry with intensity of emotion more akin to Tang verse; Qian Qianyi wrote extremely erudite and difficult poems, some reminiscent of the dense, allusive Late Tang style and others of the Song style; and Wu Weiye was acclaimed for his long narrative poems, redolent of his nostalgia for and guilt toward the fallen Ming dynasty. Wang Shizhen (1634–1711), of the younger generation, impressed his contemporaries as a talented poet and theorist. With a preference for Tang poetry, his poetics turn on the concept of shenyun (spirit and resonance), which combines the evocation of intuitive perception with a personal tone and placid imagery, as exemplified in the following heptasyllabic quatrain, the first in a series of fourteen:

In past years heartbroken on the Moling boat,

Dreams encircle pavilions by the Qinhuai River.

After ten days of drizzling rain and wisps of wind,

The misty scene of lush spring seems like remnants of autumn.

[YYJHLJS 1.226–227]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 171]

On his visit in 1661, the poet paints a wistful spring scene of the Qinhuai River district, once the magnificent pleasure quarters of the Ming southern capital, Nanjing, where talented scholars and beautiful courtesans shared in the splendor of late Ming culture. In the opening line, the poet creates a sense of distance and history by using the ancient name Moling to refer to the ill-fated city. However, immediately in line 2 the dreams that encircle suggest emotional attachment, an inability to let go of the painful truth of dynastic transition. Even if the pavilions still stand, they seem to be remnants of a vanished past that the poet clings to in a dream. This site of romance was destroyed by the invading Manchus, but the nostalgia for the lost world remains, barely articulated, pervading the scene like fine mist transforming the spring, normally a time of renewal and hope, into the wilted remains of late autumn. Nature, in Wang Shizhen’s poetic construct, resonates with human emotion.

The last poem we read by a major poet-critic is a heptasyllabic quatrain by Yuan Mei (1716–1798), the prolific poet who promoted expressing one’s “natural sensibility” (xingling) in poetry and who wrote more than 4,400 poems in his long life. Disagreeing with the orthodox critic Shen Deqian (1673–1769), who emphasized the moral, didactic function of poetry and Tang poetic models, Yuan Mei advocated naturalness and personal expression in writing poetry above learning and formal and ethical concerns. To him, what one writes should be true to one’s feelings and character, one’s “native sensibility.” Thus, recalling Yuan Hongdao of the Gong’an school, Yuan Mei also appreciated simple folk songs and natural, unadorned diction. He encouraged women to write and publish their poetry, famously taking on scores of female students, to the disapproval of more conservative critics. According to Wang Yingzhi, the modern specialist on Yuan Mei’s poetry, his vast corpus can be said to reflect his theory of “native sensibility” in practice.12 The result is often an affable charm and urbane humor.

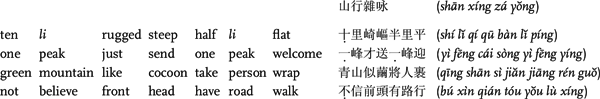

Traveling in the Mountains: Miscellaneous Poem

Rugged and steep for ten li, for half a li flat,

Just as one peak says farewell, another bids me welcome!

Green mountains wrap round me like cocoons,

I don’t believe there could be a pathway ahead.

[YMQJ 1.633]

[Tonal pattern IIa, see p. 171]

Yuan Mei records in a realistic and personable tenor his experience of traveling through a mountain range. To convey the ever-changing visual field on the mountain trail as the peaks appear and disappear, he likens them to friends who welcome and see him off one after the other. Being situated in the midst of a mountain range, Yuan Mei describes the experience of being enclosed by the surrounding peaks with the simile of a silkworm being wrapped inside a cocoon, so tightly that he declares wittily that he does not believe there is an opening ahead. Yuan Mei’s advocacy of individual, spontaneous, and natural expression in poetry widely encouraged among men and women the practice of recording everyday experience. Whether traveling, staying at home, visiting with friends, or conducting any other activity—the mundane and personal, as well as the sublime and precious—all can become subjects of poetry.

POETRY AS DIURNAL PRACTICE

The Expediency of Poetry in Times of Violence and Disorder

Chinese poetry has a long tradition of recording the sufferings and disasters caused by war. Poems dating from as early as the sixth century B.C.E. in the Shijing (The Book of Poetry) already describe the hardships of military expeditions; many are set in voices of complaint, as soldiers campaigned far from home for long periods of time and their loved ones were left behind. The yuefu ballads of the Han also represented these voices of antiwar protest.13 Yuefu poetry, as it evolved in the shi form during the Wei–Jin and period of disunion, continued the tendency to represent the sufferings of the downtrodden classes, especially in times of political and social disorder. Originally sung to musical accompaniment, some old yuefu song titles clearly indicate the theme of war and military expedition—for example, “Zhan cheng nan” (We Fought South of the Walls), “Cong jun xing” (Song of Serving in the Army), and “Yin ma chang cheng ku xing” (Song of Letting Horses Drink at the Long Wall Spring). A definite subgroup in the yuefu genre is related to the theme of war. Many yuefu titles continued to be used in the later periods; they often serve as an index to the subject of the poems.14 Although generically not considered yuefu, Du Fu’s ballads, such as “Bingche xing” (Ballad of Army Carts), “San li” (Three Officers), and “San bie” (Three Separations), and the Late Tang poet Wei Zhuang’s (ca. 836–910) long poem “Qin fu yin” (The Lament of the Lady of Qin), on the devastations of the Huang Chao Rebellion (875–884) written in the persona of a woman, are modeled on the yuefu song tradition of recounting the destruction of war from the experiences and point of view of the common people.15 In the Middle Tang, we see an explicit move among poets, notably Bai Juyi (772–846) and Yuan Zhen (779–831), to develop the xin yuefu (new yuefu) as a poetry dedicated to social criticism.

Poetry recording the writer’s own experience of war is often traced back to the poem “Beifen shi” (Poem of Lament and Indignation), attributed to the woman poet Cai Yan (176?–early third century), in which the female narrator describes the carnage wrought by the invading Xiongnu and her own capture by them at the end of the Later Han dynasty (25–220).16 But the poet who made poetry into a consistent and effective medium to record personal experience and eyewitness accounts during wartime atrocities was Du Fu.17 His long poems in the song form, such as “Bei zheng” (Northern Expedition) and “Zi jing fu Fengxian xian yonghuai wubai zi” (From the Capital to Fengxian: Expressing My Feelings in 500 Words), to name the most famous two, recount the devastation of the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763) as experienced by him and those whom he came into contact with in the chaos. They remain strong indictments of the brutality of war, all the more powerful and moving for being personal, firsthand experiences. Implicitly or explicitly, Du Fu remained the model of inspiration for poets writing about the horrors of war that they personally witnessed.

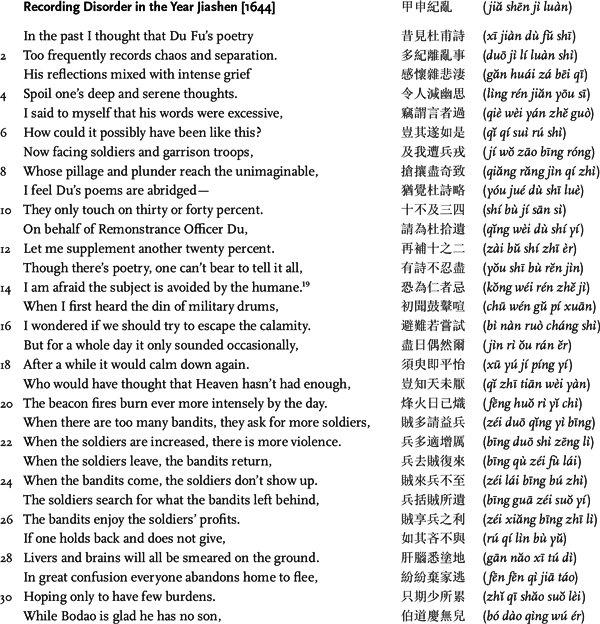

The widespread violence during the Ming–Qing dynastic transition in the middle decades of the seventeenth century not only was perpetrated by the Manchus during their military conquest, but also encompassed attacks, pillage, plunder, and destruction carried out during internal uprisings by native groups of local bandits, thugs, rebels, and roving soldiers. The lives of countless men and women, old and young, were displaced and often destroyed regardless of class and region. Recording the common experience of fleeing from Qing troops, renegade Ming soldiers, and local bandits in this disordered time forms a thematic subgenre of poetry. Many poems are identified explicitly in the title with the term bi luan (avoiding, escaping from disorder), bi bing (escaping from the soldiers), bi kou (escaping from the bandits), or bi lu (escaping from the caitiffs). Many of these poem titles also specify one of the two years in the Chinese sexagenary cycle of the Manchu conquest: Jiashen (1644) and Yiyou (1645). The fall of the Ming empire, at first heard as the tragic news that arrived from the distant capital Beijing and later the southern capital Nanjing, materialized into the presence of Manchu forces at the gates of southern cities and on the poets’ very doorsteps.

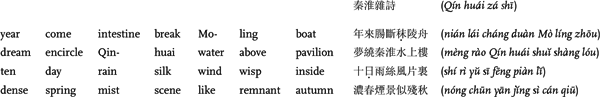

The famous dramatist Li Yu (1611–1680) lived through the worst years of the Ming–Qing transition as a fugitive in the mountains of his native district, Lanxi, and neighboring Jinhua in central-eastern Zhejiang.18 Several poems in his collection record his experience of disorder and dislocation during the two calamitous years. Even when he was writing about a disaster of such “national” magnitude, Li Yu the indefatigable individualist with a bent for the comic still employs his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style in his narrative:

[QSJS 4.2372–2373]

Li Yu begins the poem by explicitly referring to Du Fu’s war poems as a foil to the severity of the present situation (lines 1–14). In times of peace, he had thought that Du Fu had exaggerated the turmoil of the An Lushan Rebellion in his poems. But Li Yu now realizes that his previous reading was erroneous. When Du Fu’s poems are read against the present peril that Li Yu is experiencing all around him, he finds them to be insufficient expressions of the horrors of war. After noting how he and other local people hesitated when the battles began between whether to stay put or try to escape from the disaster besetting their area (bi nan), Li Yu turns to describe what clinched people’s decision to leave—the rampant and continual violence inflicted by soldiers and bandits alike. Lines 21–26 are structured with repetitions of “bandits” and “soldiers” that emphasize their mutual substitutability and the recurrence of violence. This repetitive pattern is picked up again in lines 37–46 and produces an overall parodic and theatrical effect. The poem also emphasizes the inversion of values and twists of fate in times of disorder. In lines 31 and 32, Bodao is the style name of Deng You of the Jin. During the Yongjia period (307–313), when he was trying to escape from a mutiny into the mountains with his small son and nephew, he altruistically gave up his son when he could not protect both children. As a result, he ended up sonless.20 [Zi]ping is the style name of the Eastern Han scholar Xiang Chang, who disappeared as a wandering recluse after taking care of his children’s marriages.21 Li Yu uses these two allusions to demonstrate the inversion of normative values: in such an age of violence, it would be better not to have children at all. The next couplet (lines 33–34) follows with examples of misfortunes that befall people and things of high value in the social and political chaos of the period. There is no real safety even in the deep mountains, as they are infiltrated by both soldiers and rebels. In the end, the poet could only conclude, in a self-mocking tone, with the grim and fatalistic view that an age of disorder is part of heaven’s workings, from which hapless fugitives, like inconsequential ants, cannot escape.

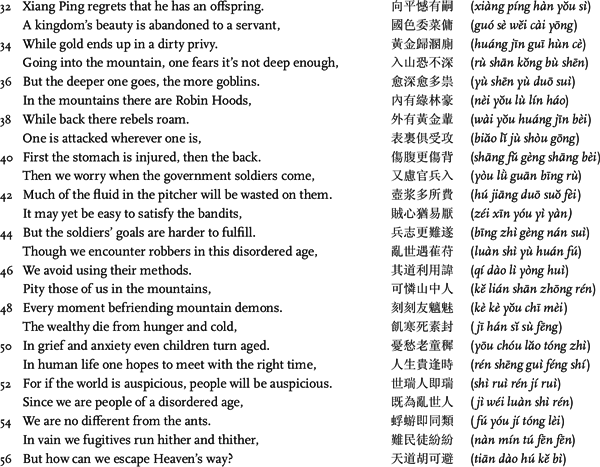

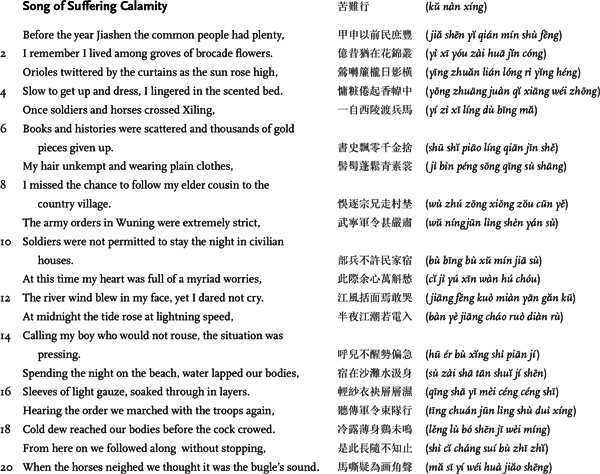

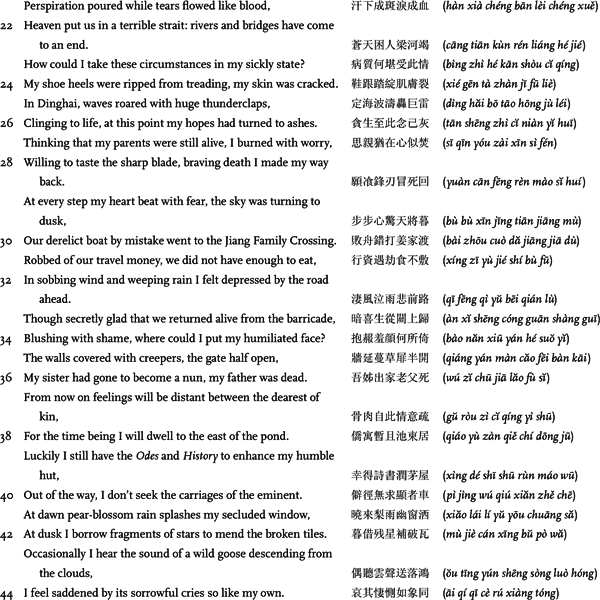

In contrast, the woman poet and critic Wang Duanshu (1621–ca. 1680), a native of Shaoxing (also in present-day Zhejiang), recorded in an entirely serious tone her plight of fleeing with the retreating Ming soldiers from the advancing Qing troops in 1645. She vividly recounts her harrowing experience in the heptasyllabic ancient-style poem “Kunan xing” (Song of Suffering Calamity):

[YHJ, gexing, 2a–3a]

The poem opens with a picture in the poet’s memory of the peaceful life of luxury before the Manchu conquest. Surrounded by feminine images such as “brocade flowers,” “curtains,” and “scented bed,” the female persona is ensconced in the inner quarters, the proper spatial location for women. This dreamlike life of comfort is rudely disrupted by the imminent arrival of invading troops in line 5. The remainder of the poem turns to a narration of the poet’s arduous flight from the Manchus, her equally harrowing journey home, and the state of devastation she discovers on her return.

Along with her young son and other kin and townspeople, Wang Duanshu was thrown onto the open road as a fugitive. She records how they fled with the retreating Ming troops when the Qing forces crossed the Qiantang River and took Shaoxing and Ningbo in July 1645.22 She describes their nightmarish march to Dinghai (on Putuo Island off the Zhejiang coast), sleeping in the open and on wet beaches along the way because they were traveling with troops. They traveled along the northern coast until they reached the island. In line 24, the image of her shoes with heels ripped from trudging poignantly reminds the reader of the difficulty of the march for women with bound feet. After the poet reaches Dinghai, she has almost lost all hope of living. Structurally at almost midpoint in the poem, the narrator, motivated by a strong sense of filial piety to look after her parents, begins to make her journey home through dangerous conditions (lines 27–28). Somewhere along the way, their boat gets lost and they are robbed (lines 30–31). Wang Duanshu probably made her way home sometime in 1646.23 However, when she arrives back, she learns that her elder sister has left home to become a nun and her father, the loyalist scholar Wang Siren (1575–1646), has committed suicide in Beijing. They both took the two common but radical responses of Ming loyalists to the Manchu conquest. Near the end of the poem, even amid her shattered life, as a learned gentry woman Wang Duanshu is able to find consolation and hope in the remains of Chinese culture, signified by the Confucian canons the Book of Poetry and the Shangshu (Classic of History) that have survived the ravages of war and foreign invasion (line 39). However, the final image of the “wild goose” injects a note of personal loss. Geese flying in formation conventionally denote the intimacy and sense of togetherness between siblings. The poet identifies with the sad cries of a wild goose, which suggests that it has lost its flock. The closure inscribes a sense of personal loss experienced by a “remnant” subject of a fallen dynasty and a survivor who has lost her sister and father.

The experience of loss and dislocation was so complex and traumatic that, for those who had the means and skill, writing must have served as a therapeutic means of regaining some sense of control, order, and personal dignity. The poetic form itself provided the formal regularity of structure, rhyme, and rhythm, into which literate victims of war and violence were able to channel their anguish and seek to manage their trauma.

Life Histories: Poetry as Autobiography

In no other comparable literary tradition was the autobiographical potential so strongly embedded in the orthodox conception of poetry as that in China. The function of poetry to articulate what was in one’s heart and on one’s mind (shi yan zhi)—private emotion as well as moral ambition—facilitated the development of the poetic medium into a versatile vehicle of self-writing and self-recording for educated men and, increasingly in the later periods, for women. This lyric expressiveness was reinforced by the strong subjectivity in the oral tradition, particularly of songs in the first-person voice, which provided much of the corpus that came to form the first canon of poetry, the Book of Poetry, privileged as a Confucian classic since the Han period (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.).

As Stephen Owen has demonstrated so cogently in his seminal study, the autobiographical dimension in Chinese poetry was taken to a sophisticated height early in the literary tradition by Tao Qian (365?–427) and later Du Fu.24 The training in and practice of shi and, later, ci poetry can be viewed as discursive regimes that produced certain articulations of individual subjectivity in imperial China. Even with the customary omission of personal pronouns in the Chinese poetic language, the common assumption among writers and readers of shi poetry of a “single unified lyric speaker”25—the poet’s persona and subjectivity—informing the poetic utterance ensured the development and persistence of a significant personal and subjective dimension in poetry. It is not surprising that poetry remained, for the majority of educated men and women, the most prevalent medium of self-representation. Situated in the present moment of inscription, the poet, by articulating emotion or intellection (yanzhi) in response to a wide range of experiences, both actual and textual, constructed and recorded a multifaceted life history with an eye to a community of contemporary and future readers that often included older versions of the authorial self, who would reread and sometimes revise particular poems or parts of poems, especially at the time of publication. The material accumulation of this process of poetic inscription over time was the making of the individual collection of poetry (bieji), which could be edited, arranged in order, and molded into a loose and selective form of self-narrative. As Owen has observed, since the ninth century, poets increasingly undertook the editing of their own poetry collections, creating what he has termed a “species of interior history,” “letting a life story unfold in the author’s sequence of responses.”26

In the late imperial period, men and women alike exploited this textual means for constructing a self-record that comprised lyrical moments of interior life, situated in or juxtaposed to external, social occasional events. These records participated in a highly formalistic and conventionalized “grammar” of poetic language. As we have seen in previous chapters, a comprehensive repertory of the basic forms and structures as well as the essential vocabulary and subgenres of the two major genres of shi and ci had been developed by the Tang and Song periods. Contextualized by titles, often also by prose prefaces and even interlineal explanatory notes by the poet, such poetic self-textualization constituted a quotidian process that would continue as the author’s life progressed. In this practice, writing poetry functioned in a way similar to keeping a diary or personal journal. When the poems were collected and compiled into a chronologically sequenced whole, the resulting text would embody a form of life history.

In poetry collections, the autobiographical narrative frame can be further reinforced by volume and chapter divisions that are named meaningfully, according to stages in the self-narrative. I illustrate this autobiographical practice in the exemplary poetry collection of Gan Lirou (1743–1819), a gentry woman of Fengxin County, in present-day Jiangxi Province, who lived in the era of peace and prosperity referred to as the High Qing.27 I discuss the overall organization of her collection in relation to the production of a life history through poetry and read examples of her autobiographical voice in selected poems.

Gan Lirou’s remarkable poetry collection is entitled Yongxuelou gao (Drafts from the Pavilion for Chanting About Snow). As a programmatic and lifelong self-representation by a woman, it epitomizes the many strands of autobiographical practices in late imperial China. Gan Lirou’s autobiographical collection stands both in contrast with and in complement to the many poetic texts by men and women—whether comparably long or exceedingly short, whether complete or fragmented and unfinished—each attempting to articulate and record some local sense of subjectivity.28 The collection is remarkable not only for demonstrating the sustained effort in self-writing that Gan Lirou made throughout her long life, but also for the way she structured the collection to tell her personal history conceived in the chronological frame of the paradigmatic life cycle of a Chinese woman in the imperial era. Gan Lirou was keenly conscious of the changing roles in her life course, which she recorded conscientiously in her poetry.

In a preface she wrote to her collection when she was seventy-three, Gan Lirou indicated how she had been stringent in selecting poems from a lifetime of writing to form the text through which she wished to be known by posterity. She stated that she had edited out half of her poems. This process of self-selection and censorship was effectively a means to shape her self-representation.

Gan Lirou arranged her poems in four chapters according to the stages of her life—as a young daughter living at home with her parents and siblings, as a loving wife and dutiful daughter-in-law after marriage, as a bereft widow bringing up her children, and, finally in old age, as a contented mother living in retirement with a successful son. She named each chapter accordingly, beginning with “Xiuyu cao” (Drafts After Embroidering), which consists of poems from her maidenhood; followed by “Kuiyu cao” (Drafts After Cooking), of poems from her married life; “Weiwang cao” (Drafts by the One Who Has Not Died), of poems from her widowhood; and finally “Jiuyang cao” (Drafts by One Who Lives in Retirement with Her Son), of poems written while she lived with her younger son after he had passed the jinshi examination and obtained official appointment as a magistrate. Each chapter title is meant to capture the most significant womanly “occupation” or status for each phase: embroidering is a young girl’s work and training in feminine skills, food preparation in daily life and on ritual occasions is the duty of a married woman, the widow is the “one who has not died” (after the death of her husband), and living in retirement with one’s son is a woman’s fulfillment in old age. As the autobiographical record of her everyday and emotional life over time, this edited collection of over 1,000 poems bears witness to the vital role that writing played throughout the various stages of one woman’s life.

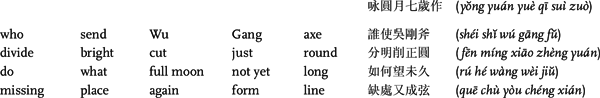

The first poem in Gan Lirou’s collection is a pentasyllabic quatrain, “On the Full Moon.” Written at age six, it was a poetic exercise prompted and then probably corrected and improved by her parents and elder siblings, a piece the poet treasured and preserved as the opening poem in her collection:

On the Full Moon: Written at Age Six

Who sent Wu Gang’s axe

Clearly to chop it exactly round?

How come not long after it’s been full

Again a crescent forms where it has waned?

[YXLG 1.1a]

[Tonal pattern I, see p. 170]

The moon, a ubiquitous trope in the poetic tradition, recurs throughout Gan Lirou’s entire collection, varying in its many emotional and cultural valences in the context of her life course. Here, in the first preserved effort by Gan Lirou, a child’s curiosity about the waxing and waning of the moon is animated by reference to the legend of the mythical figure Wu Gang cutting away at the 5,000-foot osmanthus tree on the moon.29

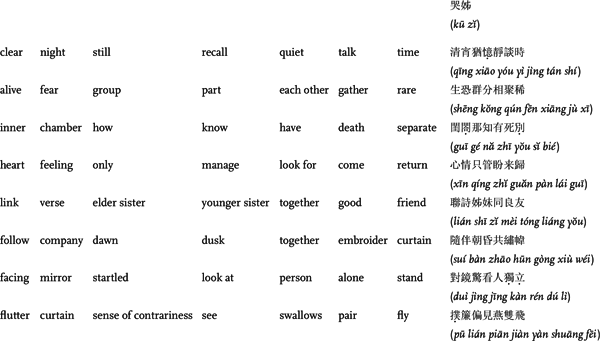

Gan Lirou’s happy childhood and adolescence were soon devastated by a series of successive deaths in the family. First an elder brother died away from home, then her only sister, followed by her mother when Gan Lirou was eighteen. She wrote many poems mourning the loss of companionship and sisterly intimacy and of maternal guidance and counsel in her journey through life. “Weeping for Elder Sister” is inscribed with memories of embroidering and writing poetry together with her sister—two activities young ladies of elite households often performed together:

In the clear night I still remember when we chatted quietly.

2 When you were alive, I feared we would part, with little chance to be together.

In our inner chambers, how could we know we’d be separated by death?

4 In my heart, I could only pine for your visits home.

Sisters linking verses were like the best of friends,

6 I followed my companion, at dawn or dusk we embroidered together.

Now in front of the mirror I am startled to see myself standing alone,

8 Why must I see a pair of swallows fluttering by the curtains?

[YXLG 1.20a]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 172]

Gan Lirou had feared only that she and her sister would be separated during their lives by marriage, when they would leave their natal home for their husbands’ families. This makes the untimely and eternal parting by death all the more poignant. After recalling their companionship as young girls in the inner quarters, the poem ends with the speaker gazing at her image in front of the mirror alone, without her sister. The image of paired swallows, conventionally signifying lovers, is used as a foil for the speaker’s loss of her companion.

After the three-year mourning period for her mother, Gan Lirou was married to Xu Yuelü, in a match her parents had made. Uncharacteristically for a young woman, Gan Lirou composed her own version of “Hastening the Bride’s Toilet,” a celebratory verse usually written by guests as the bride is fetched from her home. Herself the bride about to be fetched, she used this wedding poem to record her experience of this important rite of passage. As she puts on her bridal gown and headdress, she laments that her mother is no longer alive to perform the custom of tying the sash for her:30

Pearl headdress and patterned robe suddenly put on my body,

In marrying, I take leave of my family and part from those I love.

The way of the daughter comes to an end, that of the wife begins,

But there is no mother to tie my sash with her own hands.

[YXLG 1.35a]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 171]

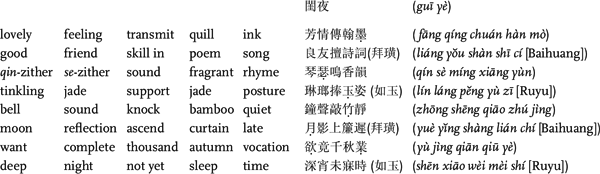

For ten years, Gan Lirou enjoyed a companionate marriage. She gave birth to two sons and two daughters. She not only was a capable and supportive wife but also served her parents-in-law in exemplary fashion and kept in touch with her father and younger brother by letters and epistolary poems. When her husband was home, the two of them also composed many linked verse together. The pentasyllabic regulated poem “Night in the Boudoir,” one of many such joint efforts by the young couple, demonstrates the romantic and poetic compatibility between them.

Your lovely sentiments transmitted in ink,

2 My good friend excels in poems and songs. (Baihuang)

Fragrant tunes rise from the zithers,

4 The tinkling gems enhance the jadelike beauty. (Ruyu)

As the temple bell sounds amid hushed bamboos,

6 The moon’s reflection rises late on the curtain. (Baihuang)

You want to put all your efforts into the vocation of a thousand years,

8 Deep in the night, not yet gone to bed. (Ruyu)

[YXLG 2.34b–35a]

[Tonal pattern II, see p. 171]

Alternately composing couplets for the same poem, husband and wife shared many conjugal moments and signed their courtesy names (Baihuang and Ruyu, respectively) to the couplets they each composed. Her husband initiates the poem by demonstrating his appreciation of his wife’s expression of love in skillful poetic composition. Gan Lirou’s first response emphasizes their conjugal harmony and mutual pleasures by using a standard image for husband and wife, the two types of zither—qin and se. The synesthesia of the visual, aural, and olfactory senses in the line “Fragrant tunes rise from the zithers” conveys the quality of and harmony in their relationship. While her husband continues in the next couplet to bring out the nocturnal universe that is exclusively theirs, Gan Lirou ends the poem by reference to the familiar theme of their mutual dedication to his studies for the examination late into the night. This is also the valued time of their being in each other’s exclusive company after the children and elders have gone to bed.

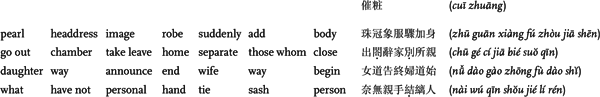

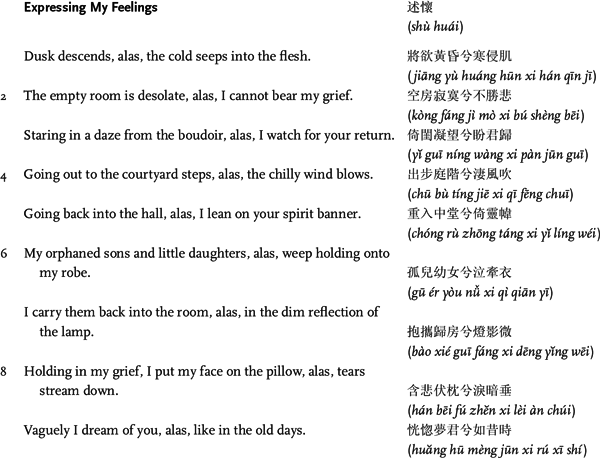

Tragically, her husband died in his thirties while studying away from home, and Gan Lirou was left a widow to bring up her small children and care for her mother-in-law. During the three-year mourning period, she wrote many poems grieving for her husband. Many of these poems make explicit the contrast between their happiness together in the past and her solitude in the present. Cast in the emotionally expressive sao style (chap. 2), “Expressing My Feelings” melds the external desolation of a funeral wake with the young widow’s passionate grief:

[YXLG 3.4a]

It is dusk, the room is empty, and the young widow is emotionally devastated while keeping wake by her husband’s spirit tablet with the small children. Her agitated emotional state is indicated by her movement of going out from the inside to the courtyard and then back again. In the final line, Gan Lirou alludes to the poem “The Cock Crows” in the Book of Poetry, which was interpreted as referring to a virtuous royal consort who woke up the ruler for his court audience when she heard the cock crowing at dawn.31 The poem has become a standard reference for a virtuous wife who attends to her husband’s affairs. The allusion emphasizes that her deceased husband can no longer heed her counsel. Her longing for him can be sought only in dreams.

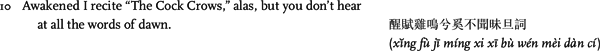

After the travails of a long widowhood, Gan Lirou was finally vindicated by her younger son’s success in passing the highest examination and obtaining an official position. With all her duties fulfilled, Gan Lirou felt she had come to terms with herself. Her poems from this period reveal that she had begun to enjoy a leisurely life in old age, finding pleasure in nature’s delights, creativity in practicing the literati arts, and peace in spiritual contemplation.

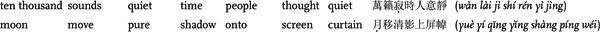

In leisure, I roll out a scroll and open the window,

2 A painting in hand, I face the twilight in the breeze.

The world seems small when one takes a broad view,

4 Looking back, one recognizes the mistakes of the past and present.

Only when I practice meditation do I realize an undefiled mind,

6 Only when I copy sutras do I know there’s a crucial point in the brush.

When the myriad sounds quiet down thoughts become tranquil,

8 The moon moves pure shadows onto the screen.

[YXLG 4.27a]

[Tonal pattern Ia, see p. 172]

The persona in “Recited at Random” expresses a philosophical attitude toward life. One’s perspectives change, depending on how one looks at phenomena. In the everyday life of old age, Buddhist practices help one to recognize worldly mistakes and purify the mind. Gan Lirou turned to spiritual practice as she grew old.

Poetry and the Pleasures of Everyday Life

Poetry as a cultural force indeed pervaded the quotidian life of literate women and men in the Ming and Qing. This is amply reflected in the large repertory of poems on the pleasures of everyday life we find in poetry collections from this period, which offer an uplifting contrast to the poems recording experiences of violence and disorder examined previously. This chapter concludes, then, with two poems by women at different ends of the life course that afford some insight into this ubiquitous dimension of Chinese poetic discourse.

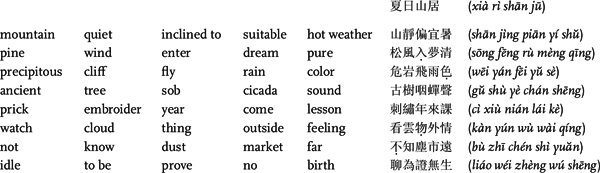

On a Summer Day: Dwelling in the Mountains

The hills are quiet, just right for hot weather,

2 Wind through the pines enters into clear dreams.

Rain colors fly across precipitous cliffs,

4 On ancient trees sob the sound of cicadas.

Stitching embroidery has been my lesson in recent years,

6 Watching clouds—sentiments beyond phenomena.

If one does not know that the dusty world is faraway,

8 In vain one will try to prove No Rebirth.

[GGZJ 1.20b]

[Tonal pattern I, see p. 171]

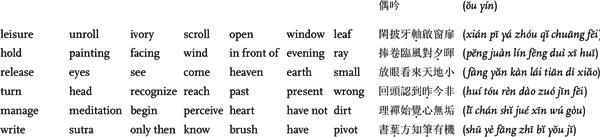

Judged from the aesthetics of poetic craft, the pentasyllabic regulated poem “On a Summer Day: Dwelling in the Mountains,” by the young Yan Liu (seventeenth or eighteenth century), is obviously inspired by and modeled after the Buddhist-inflected “nature” poems of the Tang poet Wang Wei (701–761), but one that also embodies gendered experience. Yan Liu is learning to embroider and to write poetry, requisite skills of cultured young women of gentry families in this period. On the formal level, traces of literary practice are apparent. The poem has the required rhymes and tonal antithesis; the prescribed parallelism of the second and third couplets is largely met on the syntactic but not quite on the semantic and grammatical levels. She borrows freely from the well-known vocabulary and syntax of Wang Wei’s famous regulated verses: the sound of “wind through the pines,” “watching clouds,” “beyond phenomena,” and the verb ye (sob, choke), including inverting its syntactic position with the subject “sound of cicadas” in line 4. But the one thing that is new in this poem is the motif of embroidering and its seemingly natural place in a woman’s everyday life, which encompasses seamlessly the enjoyment of nature, the art of poetry, women’s work, and spiritual contemplation.

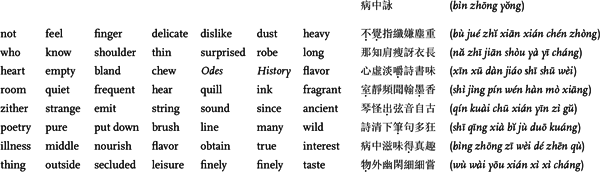

Similarly, in “Recited While Sick,” the Manchu woman Mengyue, a widow for most of her life, fully exploits the attributes of femininity conventionally associated with women’s illness and the spatial location of the inner quarters in her self-representation:32

Not aware that my fingers have turned slim, I find the dust heavy,

2 Surprised by the robe’s length, I didn’t realize that my shoulders had grown thin.

With empty mind, I quietly chew over the flavor of the Odes and History,

4 In the silent room, I frequently smell the fragrance of ink.

Since ancient times the zither strings have emitted unusual sounds,

6 So many wild phrases when I put the brush to write pure poetry.

From the flavor experienced in illness I attain true inspiration,

8 I savor slowly the hidden leisure beyond things.

[GGZX 5.17a]

[Rules of tonal patterning not observed]

The effect of the emphasis on the femininity of illness in the opening couplet does not result in the image of a fragile beauty languishing in sorrow. Instead, the persona turns to “chew over” the meaning of the Book of Poetry and Classic of History, with a mind free from mundane cares in a quiet environment. Her mind/intellect is rendered sensually as taste: she “chews” the classics, is inspired by the “flavor” of illness, and “savors … hidden leisure.” Her intellectual discernment rendered through the metaphor of taste almost fuses with her sense of smell and motion when she writes uninhibited poems with the fragrant ink. She claims that these “wild” lines of poetry are akin to extraordinary music on the ancient instrument, and concludes that it is through illness that she has reached “inspiration” and spiritual transcendence—the “hidden leisure beyond things.” This attitude takes her beyond a mundane experience of illness to a spiritual dimension in everyday existence. Such is the transformative power of poetry.

NOTES

1. A comprehensive catalog is Hu Wenkai, Lidai funü zhuzuo kao (Women’s Writings Through the Ages) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1985). For the database and digitized texts of ninety-six collections, see Ming–Qing Women’s Writings: A Joint Digitization Project Between McGill University and Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University (http://digital.library.mcgill.ca/mingqing).

2. The compilation of Ming shi poetry was begun in 1990: Quan Ming shi (Complete Shi Poetry of the Ming), 3 vols. to date (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1990–).

3. Dorothy Ko discusses the publishing boom in this period and its effects on the reading public in her seminal work Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994), 29–53.

4. There is by now a substantial body of scholarship on women’s literary culture in the Ming and Qing. For an up-to-date bibliography, see Wilt Idema and Beata Grant, The Red Brush: Writing Women of Imperial China (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2004).

5. For an overview of the major figures and their theories, see Zhang Jian, Ming Qing wenxue piping (Ming–Qing Literary Criticism) (Taipei: Guojia chubanshe, 1983), and James J. Y. Liu, Chinese Theories of Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975).

6. Due to limitations of length, this chapter does not include poetry written by men and women during the increasing social and political instabilities caused by internal rebellions and European incursions in the nineteenth century, which augmented the tradition of poetic witnessing and personal recording.

7. On Li Mengyang’s poetic theory and practice, see Yoshikawa Kōjirō, Five Hundred Years of Chinese Poetry, 1150–1650: The Chin, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties, trans. John Timothy Wixted (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), 140–149.

8. Charles Egan discusses a frontier poem, “Following the Army” (C10.11), in chapter 10.

9. Guo Qingfan, ed., “Xiaoyao you” (Free and Easy Wandering), in Zhuangzi jishi (Zhuangzi, with Collected Commentaries) (Taipei: Qunyutang chuban gongsi, 1991), 1:6, n. 3.

10. Yuan Hongdao made this statement in describing his younger brother Zhongdao’s poetry, in “Xu Xiaoxiu shi” (Preface to Xiaoxiu’s Poetry), in Yuan Hongdao ji jianjiao (The Works of Yuan Hongdao, with Annotations and Collations) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1981), 1:184.

11. Zhu Yizun, Jingzhiju shihua (Remarks on Poetry from the Dwelling of Quiet Intent) (Beijing: Renmin wenxue chubanshe, 1998), 2:478–479.

12. Yuan Mei quanji (The Complete Works of Yuan Mei), ed. Wang Yingzhi (Nanjing: Jiangsu guji chubanshe, 1993), 1:4.

13. Anne M. Birrell, “Anti-War Ballads and Songs,” in Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China (London: Unwin Hyman, 1988), 116–127.

14. See examples in the comprehensive anthology of yuefu poetry compiled by Guo Maoqian in the Song: Yuefu shiji, 4 vols. (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1979). Joseph Allen focuses on the intratextuality of the yuefu in In the Voice of Others: Chinese Music Bureau Poetry (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1992).

15. Wei Zhuang, “The Lament of the Lady of Ch’in,” trans. Robin D. S. Yates, in Sunflower Splendor: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Poetry, ed. Wu-chi Liu and Irving Yucheng Lo (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975), 267–281.

16. For a translation and discussion of authorship, see Hans Frankel, “Cai Yan and the Poems Attributed to Her,” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 5, no. 2 (1983): 133–156.

17. The most comprehensive study of Du Fu’s life through his poetry is William Hung, Tu Fu: China’s Greatest Poet (New York: Russell and Russell, 1969).

18. On Li Yu’s drama, fiction, and prose writings, see Patrick Hanan, The Invention of Li Yu (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988).

19. The meaning of this couplet is ambiguous. Li Yu seems to be suggesting that he now understands that those who are humane do not have the heart to record the violence and cruelty of war in exhaustive, graphic details.

20. Hanyu da cidian (Great Dictionary of the Chinese Language), 1.1266B.

21. Hanyu da cidian, 3.138A.

22. For the Manchu troop movements and Ming loyalist resistance, see Lynn Struve, The Southern Ming, 1644–1662 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1984), 75.

23. The more cohesive local resistance movement in Shaoxing was able to drive out the Qing occupation swiftly, and the Ming restoration movement established the prince of Lu as regent in Shaoxing a month or two later. Thus began the Longwu reign (1645–1646) (Struve, Southern Ming, 76).

24. Stephen Owen, “The Self’s Perfect Mirror: Poetry as Autobiography,” in The Vitality of the Lyric Voice: Shih Poetry from the Late Han to the T’ang, ed. Shuen-fu Lin and Stephen Owen (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986), 71–102.

25. Maija Bell Samei, Gendered Persona and Poetic Voice: The Abandoned Woman in Early Chinese Song Lyrics (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2004), 98.

26. Owen, “Self’s Perfect Mirror,” 73.

27. Gan Lirou’s autobiographical poetry writing is discussed in Grace S. Fong, Herself an Author: Gender, Writing, and Agency in Late Imperial China (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008), chap. 1.

28. For comparison with a male poet’s self-narrative in his poetry collection, see Grace S. Fong, “Inscribing a Sense of Self in Mother’s Family: Hong Liangji’s (1746–1809) Memoir and Poetry of Remembrance,” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 27 (2005): 33–58. The autobiographical impulse is also strongly articulated in women’s suicide poems and their accompanying autobiographical prefaces, as discussed in Grace S. Fong, “Signifying Bodies: The Cultural Significance of Suicide Writings by Women in Ming–Qing China,” Nan Nü: Men, Women, and Gender in Early and Imperial China 3, no. 1 (2001): 105–142.

29. On the legend of Wu Gang and the moon, see Duan Chengshi (d. 863), Youyang zazu (Miscellanea from Youyang) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1981), 9.

30. This ritual is mentioned in “Dong shan” (Mao no. 156): “A girl is going to be married … /Her mother has tied the strings of her girdle” (Arthur Waley, trans., The Book of Songs [New York: Grove Press, 1978], 117).

31. “The Cock Crows” (Mao no. 96), in James Legge, trans., The Chinese Classics, vol. 4, The She King (Taipei: Wenshizhe chubanshe, 1971), 52, 150–151.

32. It is noteworthy that the Manchus, both men and women, eagerly participated in the Han Chinese culture of poetry after the conquest.

SUGGESTED READINGS

ENGLISH

Chaves, Jonathan, trans. and ed. The Columbia Book of Later Chinese Poetry: Yuan, Ming, and Ch’ing Dynasties (1279–1911). New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

Idema, Wilt, and Beata Grant. The Red Brush: Writing Women of Imperial China. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2004.

Ko, Dorothy. Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Lin, Shuen-fu, and Stephen Owen, eds. The Vitality of the Lyric Voice: Shih Poetry from the Late Han to the T’ang. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Liu, James J. Y. Chinese Theories of Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Lo, Irving Yucheng, and William Schultz, eds. Waiting for the Unicorn: Poems and Lyrics of China’s Last Dynasty, 1644–1911. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986.

Yoshikawa Kōjirō. Five Hundred Years of Chinese Poetry, 1150–1650: The Chin, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties. Translated by John Timothy Wixted. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

CHINESE

Fong, Grace S., proj. ed. Ming–Qing Women’s Writings 明清婦女著作: A Joint Digitization Project Between McGill University and Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University (http://digital.library.mcgill.ca/mingqing).

Liu Cheng 劉誠. Zhongguo shixueshi: Qingdai juan 中國詩學史: 清代卷 (History of Chinese Poetics: The Qing Period). Xiamen: Lujiang chubanshe, 2002.

Shen Deqian 沈德潛. Mingshi biecai 明詩別裁 (Discriminating Selection of Ming Poetry). Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1958.

———. Qingshi biecai 清詩別裁. (Discriminating Selection of Qing Poetry). Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1958.

Yan Dichang 嚴迪昌. Qingshi shi 清詩史 (History of Qing Poetry). Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji chubanshe, 2002.

Zhang Jian 張建. Ming Qing wenxue piping 明清文學批評 (Ming–Qing Literary Criticism). Taipei: Guojia chubanshe, 1983.

Zhu Yi’an 朱易安. Zhongguo shixueshi: Mingdai juan 中國詩學史: 明代卷 (History of Chinese Poetics: The Ming Period). Xiamen: Lujiang chubanshe, 2002.