Chapter 9. CSS3: Modules, Models, and Images

Unlike CSS2, CSS3 has been divided into a set of modules. By splitting CSS3 into modules, the W3C has been able to work on different modules at different speeds, with some modules already at the Recommendation level, and others moving toward final recommendations at a slower pace.

There are over 20 modules in the CSS3 specifications, with each module deserving its own chapter (or two, or three). Unfortunately, we can’t cover all of them. In this chapter, we will cover the CSS topics that are relevant in creating the look and feel of CubeeDoo. To include a few more properties, we will also look at re-creating the look and feel of the native iPhone settings screen.

The native iPhone application look and feel can be done with simple

CSS. With border-radius, background

properties, gradients, text-shadow,

box-shadow, background-size, text-overflow, and some older, well-known and

supported CSS 2.1 and earlier properties, we can create the look of an

iPhone. We’ll then apply those features to CubeeDoo.

No images means we can create the native iPhone application look without requiring extra HTTP requests and without needing a graphics program. Because we’re using CSS, should your project manager choose to alter the color scheme of your application, you can do so without having to open up an image-editing program.

CSS3 allows for creating websites with less code and fewer images than you may be accustomed to, and fewer images mean fewer HTTP requests, which improves performance. CSS3 also allows for multiple background images on a single element, which may help reduce the number of DOM nodes required to create the look and feel of your site. Reducing the number of DOM nodes improves performance, especially when it comes to page reflows and memory consumption.

Some of the CSS3 features are new. Others have been supported for years. One thing to note, however, is that just because using some of these features can save on the number of HTTP requests, using CSS3 instead of images is not always the best solution. You have to weigh the pros of maintenance and HTTP requests saved against the time needed for the browser to calculate and draw CSS graphics and the memory limitations of mobile devices. Some CSS effects, like very large radial gradients, use up memory, and can make the browser sluggish if you request a device to draw repeatedly to the memory.

Less code can mean both better performance and easier site maintenance. However, not all CSS features perform well on devices with limited memory. When we cover “risky” CSS topics, I will explain any performance ramifications of that feature, and how to avoid slowing down or crashing the user’s browser.

As some CSS3 and HTML5 features can have performance drawbacks, I

won’t leave images out completely. We’ll cover multiple background images

and border-image, two features that use

images to quickly and easily create buttons and backgrounds in Chapter 11.

We will not cover the speech, paged media, or ruby modules since they are for aural readers, printers, and Asian language sites, respectively.[57] We will cover transforms, transitions, and animations in the next chapter.

Although it predates CSS3, we will spend time on the CSS box model. The CSS box model is the basis of web page layout since CSS’s inception, so it’s important to fully grasp.

CSS Box Model Properties

Before we jump into the new CSS3 properties and values, it is important to understand the CSS box model and the properties that make up the box model. All modern mobile browsers support and have always supported border, margin, and padding properties:

border-bottomborder-bottom-colorborder-bottom-styleborder-bottom-widthborder-colorborder-leftborder-left-colorborder-left-styleborder-left-widthborder-rightborder-right-colorborder-right-styleborder-right-widthborder-styleborder-topborder-top-colorborder-top-styleborder-top-widthborder-widthmarginmargin-bottommargin-leftmargin-rightmargin-toppaddingpadding-bottompadding-leftpadding-rightpadding-top

border

The border properties and border shorthand can be used to set borders on any rendered element. Border

shorthand values can be used to style the top, right, bottom, and left

sides of an element. Longhand properties can be used to style a single

property on a single side (either top, right, bottom, or left). For

example, border-style: dotted; will

set the border on all four sides of an element to dotted, whereas

border-style-right: dashed; will set

only the right border to dashed.

The important things to know about border are:

border-styleis required for a border to show up.border-styleis required forborder-imageto work (see Chapter 11).When declaring the

widthand/orheightof an element, the width of the left and right borders will be added to the width of your element, and the height of your top and bottom borders will be added to the height of your element as per the W3C box model, as shown in Figure 9-2. This box model annoyance can be overridden with thebox-sizingproperty, described in the section .

Note

If using the shorthand, the border style is required, with width and color declarations being optional, and being set to the default values if omitted.

border-style

The border-style property

sets the style of an element’s four borders.

There are no new border-style

values in CSS3, but there are different ways of styling borders with

properties such as border-radius and

border-image, described in upcoming

sections.

The values for the border-style

property values include the keywords of dashed, dotted, double, groove, hidden, inset, none, outset, ridge, and solid.

The style of hidden is

displayed like none, and takes up no

space in the box model. If you want a transparent border that takes up

space in the box model, select a border-style value

other than none or hidden and set

the color to transparent. The hidden value is only really relevant in

defining table element border styles.

Older WebKit browsers ignored border-color when rendering inset, outset, groove, and ridge border styles. This has been resolved in

newer versions of WebKit.

A visible value for border-style is required for a border to show

up, as the default value is none. If

you want to override a border on an element, set the border-style to the default of none.

A visible border is required for the border-image property to work, which we’ll

cover in Chapter 11.

border-color

The border-color property

allows you to define the color of the border on elements

upon which you are setting a border. You can use any of the CSS color

value types as described in the section CSS Color Values in Chapter 8. The default value is

currentColor: if border-style is declared, but no border-color is defined, the border color will

be the color of the text, or currentColor.

Making triangles with CSS

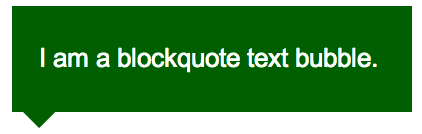

Borders are part of a nifty trick in creating triangles. To make a text box look like a quote bubble with generated content, create a box with height and width set to zero, set three of the border colors to transparent, and the fourth side’s border will make the triangle.

blockquote {

background-color: green;

position: relative;

color: white;

padding: 15px 25px;

margin: 10px 10px 0;

}

blockquote:after {

border: 15px solid;

border-color: green transparent transparent;

top: 100%; left: 10px;

width: 0; height: 0;

position: absolute;

content: '';

}In the preceding code snippet, I created a pseudoelement with no width or height, showing just one of the four border sides, which creates the appearance of a triangle. There is a link to an example of this in the online chapter resources. Figure 9-1 shows the code in action.

How would you make the speech bubble tail occur on the right or the left of the content, instead of below it?

border-width

The border-width property

sets the width of an element’s four borders. The keyword

values of the border-width property

include thin, medium, thick, and inherit, with the default value being medium. You can also use any of the length

values (px, em, etc.) described in Chapter 8.

To make the border for the triangle in Figure 9-1, we created a 15 px thick border on generated content that has no height or width. We made only the top border visible by declaring the top border green and all others as transparent.

The border-width property is

important to the border-image

property: if you don’t declare the border-width portion of the border-image shorthand, the border-image will inherit the border-width values.

Border width is also important to understand in terms of shadows and inset shadows. You can create some interesting effects using thick borders and shadows: we’ll cover that later in this chapter.

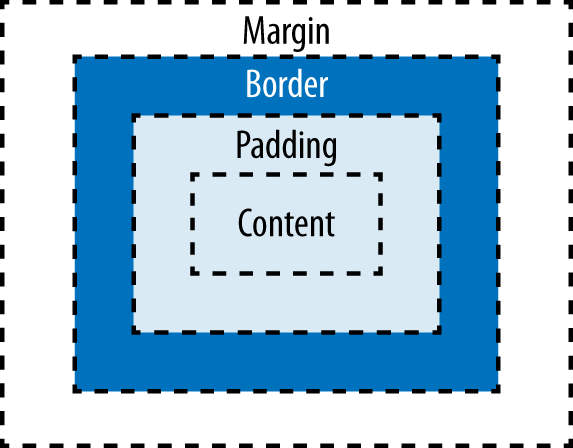

The CSS Box Model

All HTML elements are drawn to the screen as a rectangular box. The CSS box model defines the rectangle (or box) made up of margins, border, padding, and content that make up every element. The box model allows us to space out our elements across the page, defining the width of the content, the space between the content of an element and its border, and the space between multiple elements.

As shown in Figure 9-2, the components of the box model include content, padding, border, and margin:

- Content

The content of the box, where text and images appear.

- Padding

The padding is the space between the content and the border. If an element has a background image or color, the padding area will have that color or image as a background by default.[58]

- Border

The border surrounds the padding and is inside the margin: the border starts where the padding ends. They do not overlap. The border takes up space in the box model. If the element has a background image or color, and the border is dashed or otherwise fully or partially transparent, by default the background will show through the border.

- Margin

The margin is the area on the outside of the border. The margin is transparent. If the element has a background color or image, it will be contained within the border, and will not show through the margin area.

In order to set the width and height of an element, you need to fully understand how the box model works. In the traditional box model, the declared width and height given to an element is for the content area only. The width and height you declare include the padding and borders.

Note

Width = left border + left padding + width + right padding + right border

Height = top border + top padding + height + bottom padding + bottom border

Note in Figure 9-2 that the margin area is colorless. That is because the width is not included in the width and height calculations of the width and height properties. The margin, if greater than 0, does take up space.

The size the element occupies in your layout is the content, the padding, border, and margin.[59]

Note

Total width = left margin + left border + left padding + width + right padding + right border + right margin

Total height = top margin + top border + top padding + height + bottom padding + bottom border + bottom margin

box-sizing

The box-sizing is one of the

best, if not the best, features given to us by CSS3, especially if you

think Microsoft got the box model right in IE, and the W3C got it wrong.

Before, if we declared an element to be 100% width, we avoided declaring

a border or padding on that element, as it would end up being wider than

its container. The box-sizing

property solved this: simply set the box-sizing property to border-box:

.box {

width: 100%;

padding: 10px;

border: 1px solid currentColor;

-webkit-box-sizing: border-box; /* for older Android (3.0) */

-moz-box-sizing: border-box; /* for firefox */

box-sizing: border-box;

}Note

If you want 100% to be 100% in spite of padding and border, you

can mimic the IE6/IE7 box model by setting the box-sizing property to border-box.

The box-sizing property has

been supported since IE8, but must be prefixed in all versions of

Firefox, and in mobile WebKit browsers up to iOS 4.3, Android 3.0, and

Blackberry 7.

Until calc() is fully

supported, box-sizing: border-box is

a panacea!

Margins

Another part of the box model that some people find confusing is the effect of margins on two adjacent elements. Positive margins are not additive: if two adjacent abutting elements have positive margins, the distance between them will be the larger of the two margins, not the sum of both margins. Unless one of those margins is negative; then the distance between the elements will be the sum of positive and negative margins.

Learning CSS3

Now that the box model is out of the way, we can jump into some very useful CSS3 features. We’re going to start by creating the look and feel of the native iPhone app with CSS only. The HTML for our examples is:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8"/>

<title>iPhone Look and feel</title>

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width; initial-scale=1.0;"/>

</head>

<body>

<header>

<nav>

<ul>

<li class="button cancel">Cancel</li>

<li class="button done">Done</li>

</ul>

<h1>Languages</h1>

</nav>

</header>

<article>

<ul>

<li lang="en-us">English</li>

<li lang="fr-fr">Français</li>

<li lang="es-es">Español</li>

...

</ul>

</article>

</body>

</html>With this bit of HTML code, and some CSS, we’ll be creating a web page that looks like the languages system preferences on the iPhone, as shown in Figure 9-3.

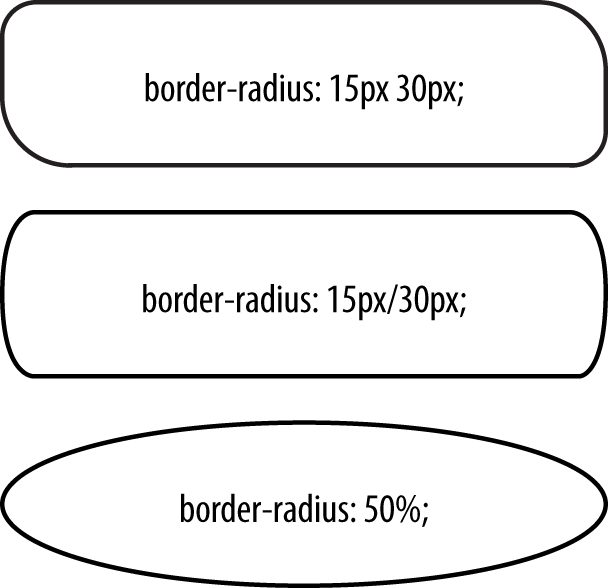

border-radius

New in CSS3, but not really new to mobile browsers, is native rounded corners created

with the border-radius property.

Border radius is a quick, lightweight way to improve your UI without

increasing download time.

Prior to being able to create native rounded corners with the CSS

border-radius property, web

developers created rounded corners by including extra markup. The

four-corner method required four added elements, each with background

images, absolutely positioned in each of an element’s four corners. The

sliding door method, the most popular of the methods, also required

images and additional markup.

While all these methods created the look of native rounded corners, they required otherwise unnecessary elements be added to the page as hooks and containers for required background images, and they required the creation and download of images. For performance, we want to minimize the number of HTTP requests, download time, bandwidth usage, and DOM nodes. We also can enjoy saving the effort of creating images, and then re-creating them as border radius length, color scheme, or other design changes are made.

The biggest drawback of the image solutions for developers were

that any changes made to border color, background color, containing

element background color, roundness, or dimensions would require new

images to be made. The drawback for users (and therefore the corporate

bottom line) is that image methods slow down the download speed and

impact the performance on handheld devices with limited memory. The

border-radius property enables

developers to include rounded corners natively: no more corner images!

Another bonus is no pixelation on zoom!

The border-radius property is

shorthand for:

border-top-right-radius: border-bottom-right-radius: border-bottom-left-radius: border-top-left-radius:

... in that order.

The syntax for the border-radius property is:

border-radius: length{1,4} / length{1,4} /* shorthand */

border-(top|bottom)-(left|right)-radius: length length /* longhand */In the shorthand, the values before the slash, if a slash is included, are the horizontal radii, and the values after the slash are the vertical radii, as shown in Figure 9-4. For the longhand values, each can take two values: the first value is the horizontal radius, the second, if present, is the vertical radius. No slash is included in the longhand syntax. If only one value is present, the vertical radius will be the same as the horizontal radius, creating a symmetrical rounded corner with the second value copied from the first. If either length is zero, the corner is square, not round.

When four values are given, the order of the corners is topleft, topright, bottomright, bottomleft. Similar to TRBL of borders, if you

only declare two values, then the first is for topleft/bottomright, and the second value is for

topright/bottomleft.

If targeting a radius value with the DOM, the values are:

myObj.style.borderTopLeftRadius myObj.style.borderTopRightRadius myObj.style.borderBottomRightRadius myObj.style.borderBottomLeftRadius

Note that the dash (-) has a

meaning in JavaScript. We don’t want to subtract radius from left from

top from border, which is what border-top-left-radius would do. In

JavaScript, the CSS property is camelCased when included as a property

of the style property of the DOM node. That being said, to keep

presentation and behavior separate, avoid using JavaScript to alter CSS

property values. Instead, define your styles in stylesheet style blocks,

and use JavaScript to change class or state.

border-radius for native-looking buttons on the iPhone and in CubeeDoo

Let’s put our knowledge to work! Native iPhone applications, as shown earlier in Figure 9-3, have several elements with rounded corners: the Cancel and Done buttons, and the main content of the page. By relying on CSS3, we can create these rounded elements of any size, color, and edge radius without any images. Let’s focus on the CSS for the content area:

1 article ul {

2 border: 1px solid #A8ABAE;

3 border-radius: 10px;

4 background-color: #FFFFFF;

5 width: 300px;

6 margin: 10px auto;

7 }Line 2 of our CSS creates a 1 px gray border. In line 3, we

include the border-radius property

to add a 10 px radius to our border. If you are supporting Android 2.1

or iOS 3.2, you can include a -webkit- prefixed property immediately

before the prefixless property. You may not want to do this: older

versions of Android didn’t handle border radius very well: omitting

the prefixed border radius saves a bit of memory in these older, less

performant browsers, and avoids the bug where scrolling makes the

border-radius temporarily disappear. Your application will look a

little different in older versions of Android, with no rounded

corners. Your users likely won’t notice the missing rounded corners,

but they’ll notice if your application fails. For that reason, I

stopped including the prefixes for rounded corners a long time

ago.

In line 6, we employed the margin shorthand property to move the

unordered list 10 px down from the navigation and center the content

area by setting the left and right margins to

auto. Since two values for margin were declared, the first value is for

Top and Bottom, and the second value is for Left and Right. (Confused?

See Avoiding TRouBLe: Shorthand Properties and Value

Declarations in

Chapter 8.)

We’ve also stylized the list items. The CSS for the list items is:

8 article ul {

9 list-style-type: none;

10 }

11 article li {

12 line-height: 44px;

13 border-bottom: 1px solid #A8ABAE;

14 padding: 0 10px;

15 }

16 article li:last-of-type {

17 border-bottom: none;

18 }Most of that CSS should be very familiar to you. Note the

:last-of-type pseudoclass in line

16. Structural selectors were covered in Chapter 7. With article

li:last-of-type {border-bottom: none;}, we are able to tell

the browser to not include a bottom border on the

last list item in every <ul>

that is found in an <article>.

I did not use article

li:not(:last-of-type) to set the borders on all of the

elements except the last one, but I could have. We have a border

bottom on the <ul> itself, if

we don’t omit the border bottom from the last <li>, there will be a double border at

the bottom of each unordered list.

What else has rounded corners? Feel free to add rounded corners to the Done and Cancel buttons on the iPhone app and the buttons and cards on CubeeDoo. The code for the rounded corners is in the chapter files.

CSS Gradients

Using the border radius property, we were able to create rounded corners, and create the look and feel of the content area of the native application with no added HTML elements, no images, and very few lines of CSS.

In addition to having rounded corners, the Cancel and Done buttons

have gradient backgrounds. We could include a separate background image on

the Cancel button, and a background image of a different color for the

Done button. With a small border-radius

we could create a close approximation of the native iPhone buttons. We

could then throw another background image in for the back of the

navigation, and another background image for the background of the whole

page. In fact, the iPhone has a PNG sprite with the buttons on it that the

native iOS applications all use as border images. Yes, we can do that,

too. However, with CSS3, this plethora of images, even a single sprite,

and their additional HTTP requests, are unnecessary. The native iOS

application layout can actually be done completely with CSS, without

importing a single .svg, .gif, .webp, .png, or .jpeg.

Gradients are not properties, they are values. Gradients can be used

anywhere an image can be, including background-images, list-style-images, and border-images. They are supported in all modern

browsers, but with varying prefixed syntaxes in older browsers.

A gradient is a CSS image generated by the browser based on developer-defined colors fading from one color to the next. Browsers support linear and radial, and repeating linear and radial gradients. Conical gradients have been added to CSS Images Level 4, but are not ready for production and aren’t covered here.

We’ll cover the current vendor-prefixed syntax supported in all browsers but only now necessary in WebKit browsers. The prefixless version of CSS gradients has gained support and should be included as the default value in your CSS. We still need to cover the prefixed syntax and the very old WebKit syntax so we can support older mobile devices.

Gradient Type: Linear or Radial

There are two main types of gradients: linear and radial. Most gradients you include will be linear. So, you’ll want to start your property value with:

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, /* Really old WebKit[60] */ background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient( /* Android, iOS thru 6.1, BB10 */ background-image: linear-gradient( /* iOS7, Chr26+, IE 10+, FF 16+, O12.1+ */

For radial gradients, you would include:

background-image: -webkit-gradient(radial, /* Really old WebKit */ background-image: -webkit-radial-gradient( /* Android, iOS thru 6.1, BB10 */ background-image: radial-gradient( /* IE 10, FF16, O12.1, Chr26, iOS7 */

In the following examples, we’ll use only the WebKit vendor prefix for prefixed version of the second syntax, and the nonprefixed version will reflect the third and final syntax. Hopefully, this will make the markup more readily understandable. Vendor prefixes are no longer needed in Mozilla or Opera browsers,[61] and were never used in any version of Internet Explorer.

Radial Gradients

We are not covering radial gradients in this book. If you would like to learn more about radial gradients, there is a link to a tutorial in the online chapter resources.

This book is about mobile development. Radial gradients and mobile devices aren’t always best of friends. When you create a radial gradient, the entire gradient is put into memory. If the radial gradient is small, single colored, with no transparency or gradations, the memory it uses will be small. However, this radial gradient is rarely the scenario. Whereas linear gradients are small images that are tiled in browser memory, radial gradients are a single much larger image that can take up a lot of memory and even crash mobile browsers on devices with limited RAM.

Images that are too large get tiled in memory. While devices differ, I make the safe assumption that images that are more than 1024 px get tiled in memory. With radial gradients, you can quickly achieve such large images.

It is OK to use radial gradients on mobile devices. Just realize that there can be performance issues that you have to consider.

Linear Gradients

The syntax for the prefixed linear gradient is:

-prefix-linear-gradient(<angle|keyterm>, <colorstop>, [<colorstop>,] <colorstop>)

Where angle is the angle in

degrees of the gradient path or a key term combination of

top or bottom and/or left or right indicating the starting point of the

gradient line and, at minimum, one declared color, with optionally more

colors, and optionally the position of said colors along the gradient

path.

The syntax for the final linear gradient syntax is:

linear-gradient([<angle>| to <keyword>], <colorstop>, [<colorstop>,] <colorstop>)The main differences are (1) the to keyword, (2) how the keyword’s gradient angles work, and (3) the value of

the angles.

With the prefixed syntax, we indicated where the gradient line

came from. The prefixless keyword syntax includes the word to, indicating where the line is heading to,

rather than where it came from.

Prefixed, the gradient line starts at the point that would be the end of the hypotenuse of a right triangle whose other two points were the midpoint of the box, and the closest corner.

The simplified unprefixed syntax added the to keyword to differentiate it: now the

gradient line goes from one side or corner to the opposite side or

corner, passing through the center of the box. Confused? Don’t worry.

I’ll explain.

Gradient angles and directions

For linear gradients, the direction of the fade is controlled in

the CSS by the <angle> or key

term. You can include a keyterm or value for the angle in degrees, rads, grads, or turns.

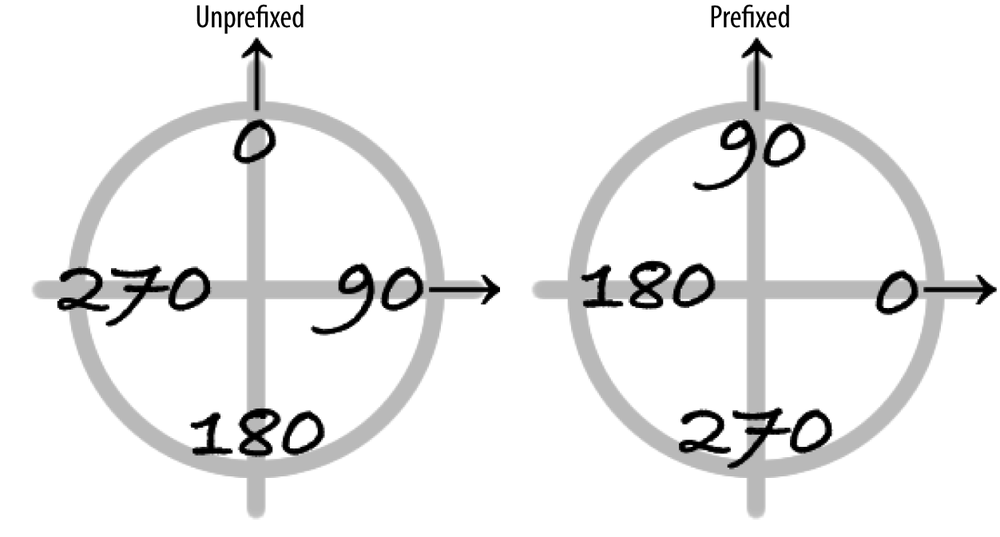

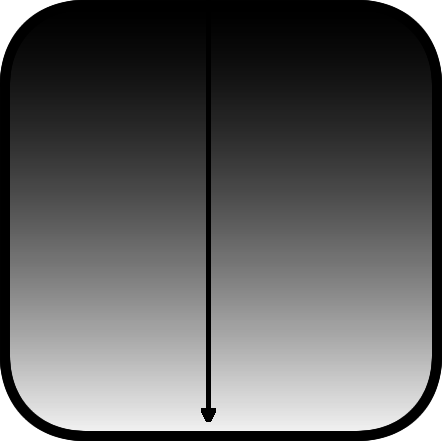

When an angle is given, the gradient path passes through the center point of your background image at the angle specified. There is a difference between prefixed and unprefixed syntax, however. The prefixed syntax angles go in the direction of the angle, and 0 deg is up, with 90 deg to the right. The prefixed angles go counterclockwise, and 0 deg is to the right. See Figure 9-5.

When declaring linear gradients, first include the prefixed versions for older browsers. When prefixed, 0 deg is to the right, and angles go counterclockwise, which may be counterintuitive. The last CSS property/value pair should be the default value without a prefix. When no prefix is present, 0 deg points upward or north, and positive angles increase as you rotate clockwise, with 90 deg pointing to the right. The gradient line passes through the center of the element at the angle specified.

Instead of using angles, you can declare the gradient path using

key terms. The keywords are the sides top,

bottom, left, or right, or corners such as top left or bottom

right.

In the prefixed syntax, the key term is the starting point of

the gradient path. The gradient will start in the general area

described by the key term, passing through the center of the background-image,

to the opposing side or corner area. For example, top will head from the top center point to

the bottom center point, passing through the center point of the

element box, and top right will

start in the top right area, passing through the center point, to the

bottom left area, though not necessarily to the corner itself.

The default CSS declaration should include the value, with no

prefix, prepended with the word to

(when using keywords), indicating where the gradient line should end.

The gradient line will start from one side or corner, pass through the

midpoint, and end at the side or corner indicated by the key term. For

example, to top will head from the

bottom center point to the top center point passing through the center

point of the element box, and to top

right will start in the bottom left corner, passing through

the center point, to the top right corner.

The default values are top,

or 270 deg for the prefixed version, and to

bottom or 180 deg in the final, unprefixed version, which

have the exact same appearance, as shown in Figure 9-6. To make the

gradient fade from black to white as it goes from top to bottom, you

could write any of the following:

/* prefixed */ -webkit-linear-gradient(#000000, #FFFFFF); -webkit-linear-gradient(top, #000000, #FFFFFF); -webkit-linear-gradient(270deg, #000000, #FFFFFF); /* un-prefixed */ linear-gradient(#000000, #FFFFFF); linear-gradient(to bottom, #000000, #FFFFFF); linear-gradient(180deg, #000000, #FFFFFF);

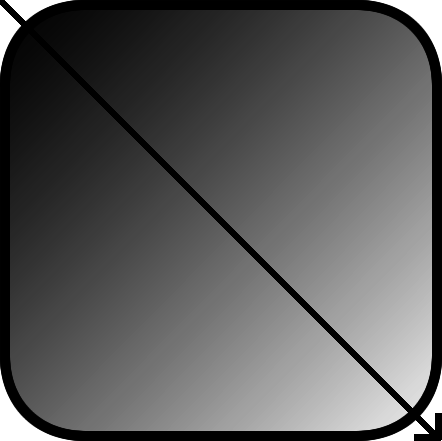

To create a gradient that has a path that goes from the top left to the bottom right, as shown in Figure 9-7, you could write the following two lines, which are similar but not identical:

/* top left to bottom right */ -webkit-linear-gradient( top left, #000000, #FFFFFF); linear-gradient(to bottom right, #000000, #FFFFFF);

Note that while prefixed 315deg or unprefixed 135deg will create the same gradient as each

other, those gradients are not the same as top left or to

bottom right, which are not identical to each other.

Prefixed 315deg and

unprefixed 135deg will go from

top left or to bottom right if your element is a square,

but only the to bottom right will

go from corner to corner if your background image is an elongated

rectangle. Why? When an angle is used, the gradient path passes

through the center of the defined background image at that angle, no

matter the aspect ratio of the box.

Note

By default, the gradient path passes through the center of the defined element because, by default, the background image is 100% of the width and height of the defined element. If you change the background position or the background size, the gradient path will not actually pass through the center of the defined element, but will always pass through the center of the background image you are defining, no matter the size or position.

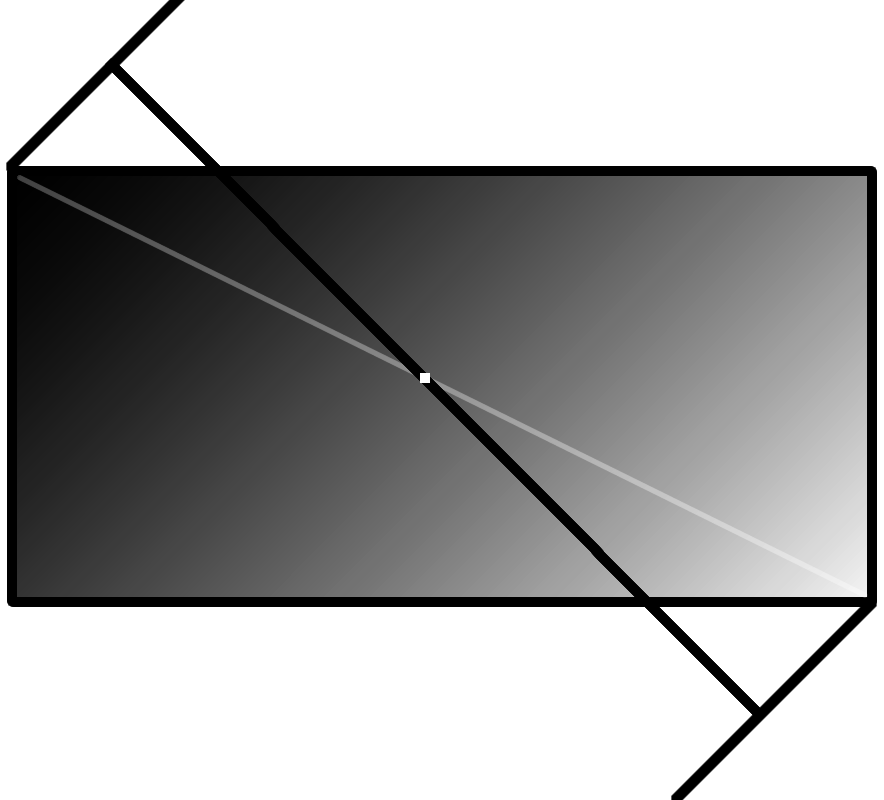

With the final syntax, or nonprefixed syntax, the key terms define that the gradient path ends in one corner after passing through the center of the background. With the prefixed or older syntax, when not a square, the gradient path extends beyond the edges of your rectangle, allowing for the start and end of your gradient to be displayed. So when prefixed, it only goes from corner to corner in this case if our box is an actual square, as shown in Figure 9-8:

background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(top left, #000000, #FFFFFF); background-image: linear-gradient(bottom right, #000000, #FFFFFF);

In Figure 9-8,

the black line shows the gradient path for top left, passing through the center of the

background image, represented by a tiny white square in the middle.

The gray path is the path the gradient takes when it supports the

un-prefixed gradient with to bottom

right instead of top

left. In the prefixed version, the end points of the

gradient path are beyond the boundary of the image, defined as the

farthest corners of the box from the center of the background image

where a line drawn perpendicular to the gradient-line would intersect

the corner of the box in that direction.

Gradient colors

Now that we know how to declare the angle of the gradient, we can include the colors of the gradient. We created a linear gradient that faded from black to white along the entire path of the gradient. To continue with our very exciting black to white example, what if we wanted to fade from solid color to solid color, displaying the solid colors on both ends for about 10% of the width of the element? That is easy to do by defining color stops.

To declare a color stop, declare the color and the position of the stop. If your first stop is not at 0%, the first color will be solid from 0% or 0 px until the first color stop, where it will begin to fade into the next color. The same is true if your last color stop is not at 100%.

If you don’t declare the position of the color stop (you just declare the color), the color stops will be evenly distributed across the full width (or height) of the background image, with the first color stop at 0% and the last at 100%.

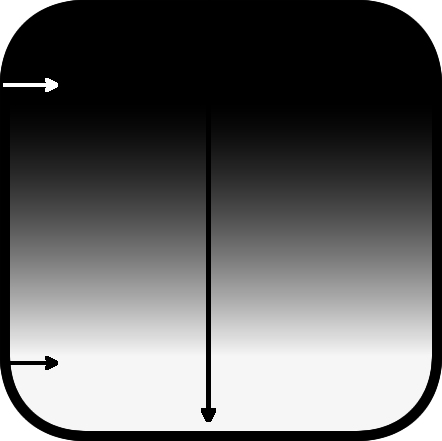

The position can be declared as a percentage of the width of the background image, or as an absolute length. If our background image is 200 px tall, these four declarations are equivalent (Figure 9-9):

-webkit-linear-gradient(top, #000000 10%, #FFFFFF 90%); -webkit-linear-gradient(top, #000000 20px, #FFFFFF 180px); linear-gradient(to bottom, #000000 10%, #FFFFFF 90%); linear-gradient(to bottom, #000000 20px, #FFFFFF 180px);

Notice that in the Figure 9-9 example, the top and bottom are both solid colors for 10% of the height of the element, before starting to fade from black to white. From the top to the 10% mark the image is solid black. From the 90% mark to the bottom, the image is solid white. It fades from black to white for 80% of the height.

The two arrows indicate the color stops, where the solid color ends and where it starts fading into the next color. We are not limited to two colors. You can add as many color stops as necessary to make the effect you are looking for (but remember, just because you can doesn’t mean you should).

Sometimes you also have more than two colors. For example, if you want to revert back to the look and feel of a 1996 website coded with cool 2013 features of linear gradients, you can create a rainbow background:

1 background-image: linear-gradient( 2 red, 3 orange, 4 yellow, 5 green, 6 blue, 7 purple);

This can also be written as:

1 background-image: linear-gradient( 2 red 0%, 3 orange 20%, 4 yellow 40%, 5 green 60%, 6 blue 80%, 7 purple 100%);

These equivalent gradients will create a rainbow with red on top, fading into orange, yellow, green, blue, then purple equally over the height of the element, as seen in the online chapter resources.

If you want your background to be an ugly striped rainbow instead of an ugly gradient rainbow (those are your only two options), we can create striping with hard color stops. A hard color stop is two color stops at the same point creating a sudden change in color rather than a gradual gradient:

1 background-image: linear-gradient( 2 red 16.7%, 3 orange 16.7%, 4 orange 33.3%, 5 yellow 33.3%, 6 yellow 50%, 7 green 50%, 8 green 66.7%, 9 blue 66.7%, 10 blue 83.3%, 11 purple 83.3%);

This gradient will be red for the first 16.7% since the first color stop is at that mark. Remember, if your first stop is not at 0%, the first color will be solid until the first color stop. At the color stop of 16.7%, it will begin to fade into the next color. The next color stop is also at 16.7%. Our fade into orange is over 0%: this is what creates the striping effect. There is no gradual change from one color to the next. Rather, we have hard color stops. Hard stops are good for striping, and also used in popular effects like candy buttons.

If we want a gradient to be only slightly opaque (or, if you’re a glass half full type of person, slightly transparent), use HSLA or RGBA colors:

linear-gradient(180deg,

rgba(0,0,0,0.1) 10%,

rgba(0,0,0,0.9) 90%);iPhone and CubeeDoo linear gradients

Now that we understand gradients, we can create the navigation bar for our faux iOS app, which is a fairly simple linear gradient.

First we have the iOS header bar. We first define a regular blue bar—everything except the gradient:

1 header {

2 /* the general appearance */

3 padding: 7px 10px;

4 background-color: #6D84A2;

5 display: block;

6 height: 45px;

7 -moz-box-sizing: border-box;

8 box-sizing: border-box;

9 line-height: 30px;

10 border-bottom: 1px solid #2C3542;

11 border-top: 1px solid #CDD5DF;Lines 3 through 11 define the general appearance. Note in line 4 that we have declared a background color. When using gradients or any type of background image, you always want to declare a background color, in case the background image fails, such as for older browsers that don’t support gradients. Another reason to declare a background color is instead of creating gradients of every color for every template color scheme you create, you can create a few translucent white gradients, and use them over your solid background colors, creating a single, reusable gradient for all of your color schemes.

As we’ve included both height and padding, we’ve declared box-sizing:

border-box to use the IE box model. We’ve also included

the -moz- prefix, which is still

necessary as the property is still considered experimental, though

it is supported everywhere.

Let’s first start by declaring solid colors. The header bar is solid in the top half, and then gets darker from the halfway mark to the bottom. We declare a solid color for the top and start fading at the 50% mark:

15 background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(top, 16 rgb(176, 188, 205) 50%, 17 rgb(129, 149, 175) 100%); 18 background-image: linear-gradient(to bottom, 19 rgb(176, 188, 205) 50%, 20 rgb(129, 149, 175) 100%);

The gradient’s first color stop is at 50%, therefore the background will be solid blue (no fading) until that point. The background then fades into a different color blue in the bottom half.

If we want our gradient to work in BlackBerry 7, Android 3.0, and other archaic browsers, we also have to include the original prefixed syntax:

12 background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, 0 0, 0 100%, 13 color-stop(0.5, rgb(176, 188, 205)), 14 color-stop(1.0, rgb(129, 149, 175)));

This works. But let’s make our gradients more reusable. Instead of creating a new gradient for every color, we can create a translucent white gradient to place on top of buttons and navigation bars of any color: create one gradient and use it everywhere. We can create a reusable gradient by using RGBA (or HSLA) to provide a transparent to slightly opaque gradient enabling us to quickly change color schemes if desired:

21 background-color: rgb(129, 149, 175); 22 background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, 0 0, 0 100%, 23 color-stop(0.5, rgb(255, 255, 255, 0.4)), 24 color-stop(1.0, rgb(255, 255, 255, 0))); 25 background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient( 26 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4) 50%, 27 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0)); 28 background-image: linear-gradient( 29 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4) 50%, 30 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0)); 31

In this second example, we’ve removed top and to

bottom from the latter two syntaxes since it is the

default, and the 100%, since by default, if the position is omitted,

the last color stop is at 100%.

By using alpha transparency instead of solid colors, we are able to create the iPhone native application look, as demonstrated in the online chapter resources. The transparency, however, allows for quick and easy color scheme changes. We can use this same gradient for our header for all of our color schemes. If we had a green color scheme we could simply change the background color to a darkish green.

How about the button gradients? The button gradients also have a gradient that covers half of the height of the button. We could use the same gradient syntax as before, except we invert the gradient (since the bottom is solid on the buttons, whereas the top is solid on the bar):

.nav li {

background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(bottom,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4) 50%,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0));

background-image: linear-gradient(to top,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4) 50%,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0));

}

.cancel {background-color: #4A6C9B;}

.done {background-color: #2463DE;}But that isn’t exactly what we want. Eye candy buttons actually have a hard change, not a soft change, when the gradient and the solid color meet. To look right, we want our gradient to only take up 50% of the height. There are three ways to do this:

You already know how to position a background image with the

CSS 1 background-position

property (background-position: 0

15px), so let’s do it with the CSS3 background-size property to make it more

flexible (and learn about this new property).

background-size

The background-size property

specifies the size of your background images. The value can be any

absolute or relative length, or the key terms contain, cover, and auto.

The contain value scales the

image down if necessary while preserving its aspect ratio, which may

leave uncovered space. A rectangular background image in a square

element set as background-size:

contain will not fill the entire area, but rather will scale

the background image down until it fully fits within its container. The

area that is left uncovered depends on the values of the background-position property, and on the value

of the background-repeat property.

The cover value scales the

image so that it covers the whole area, completely covering the element,

but perhaps not showing part of the image if the element box and the

image do not have the same aspect ratio. A rectangular background image

in a square element set as background-size:

cover will be cut off. auto

leaves the background image the same size as the original. The three

keyterm values are illustrated in Figure 9-10.

You can also specify the background size in absolute or relative

lengths. If defining in absolute or relative lengths, you can include

one or two values. If one value is declared, the width will be that

value, and the height will scale up or down so that there is no

distortion, as shown in the last example in Figure 9-10. If you prefer to

scale based on the height, declare auto for the width.

If you provide two values, they are in the order width and height, and the background image will be stretched (or shrunk) to match your stated values. In Figure 9-10, we see that at 150 px by 150 px (in a 250×250 box), the image is distorted to fit the defined size.

Only in the case when both width and height are defined do we get the possibility

of distortion. Contain, cover, auto, and declaring only one value, will

always maintain the original aspect ratio of the image. If you need to

declare a width or height, you can declare just one to ensure that no

distortion occurs, setting the other value to auto.

We can use background-size on

the gradient for our buttons, as we want the top to be a gradient, and

the bottom to be solid. The difference with the candy buttons is that we

don’t want the gradient to fade into the solid color. Rather, we want a

hard stop. As noted previously, there are a few ways to create this

effect. Here in Example 9-1, we are making use of the

background-size property.

1 .button {

2 background-image:

3 -webkit-gradient(linear, 0 100%, 0 0%,

4 from(rgba(255,255,255, 0.1)),

5 to(rgba(255,255,255,0.4)));

6 background-image:

7 -webkit-linear-gradient(bottom,

8 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1),

9 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4));

10 background-image:

11 linear-gradient(to top,

12 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1),

13 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4));

14 background-repeat: no-repeat;

15 background-size: 100% 50%;

16 }

17 .cancel {

18 background-color: #4A6C9B;

19 float: left;

20 }

21 .done {

22 background-color: #2463de;

23 float: right;

24 }We’ve defined a gradient that is similar to the header gradient,

but goes from bottom to top instead of top to bottom. We then make it

occupy only the top of the button by employing the background-size property: telling the gradient

to only occupy 50% height by 100% width.

We don’t want our background gradient to tile, or repeat

vertically, so we include background-repeat:

no-repeat. We could have also declared:

background-size: 2px 50%; background-repeat: repeat-x;

Make the background only 2 px wide, and repeat that image

horizontally. We use 2 px (or larger) instead of 1 px because of a bug

in some versions of Chrome. We declare all background properties

separately instead of using the background shorthand so we don’t accidentally

overwrite any background property values, resetting them by accident to

their default values.

By default, gradient background images fill up the entire background of an element. However, since we are defining the size of the gradient as different than the default 100% by 100%, we need to consider whether we want the background image to repeat. In this case, we didn’t.

Note

When I create a CSS reset, I generally include a blanket

statement setting background-repeat:

no-repeat on most elements. Although no-repeat is not the browser default, it is

most often the designer’s preference. By not using the background shorthand, I don’t overwrite my

reset.

DPI and background-size

The background-size property

is the property that makes high-resolution images work on high DPI

devices.

High-resolution images look nice and crisp on high DPI devices,

but all images go across the wires at the same resolution. If you want

to display high-resolution images, you display an image that is

generally twice as wide and twice as tall as the display size. This is

where the background-size property

plays a vital role in mobile CSS.

Let’s say your corporate logo is 100 px tall by 300 px wide. For

most devices, a 100 px × 300 px PNG would be appropriate. For high DPI

devices, a 200 px × 600 px PNG will look even better. The resolution

of the images are the exact same: one is just four times larger than

the other. To fit that larger image in the original space—the 100 by

300 CSS pixels—and make it a crisp-looking higher resolution image,

use background-size.

The default value for background-size is auto, which will make the image appear 200

px × 600 px. If your #logo div is

100 px × 300 px, you can declare:

#logo {

width: 300px; height: 100px;

background-image: url(logo.png);

background-size: contain; /* OR */

background-size: 300px 100px;

}

@media

screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2),

screen and (min--moz-device-pixel-ratio: 2),

screen and (-min-moz-device-pixel-ratio: 2),

screen and (-o-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2/1),

screen and (min-device-pixel-ratio: 2),

screen and (min-resolution: 192dpi),

screen and (min-resolution: 2dppx) {

#logo {

background-image: url(hidpi/logo.png);

}

}Declaring background-size:

contain; or background-size: 300px

100px; both work, as the width and height of the div are the

same size you want the image to be.

There is a downside to the background-size property: images with

background-size declared take twice

as long to render the image: the time to decode the image and the time

to resize. The extra few milliseconds can be an issue if you are

animating larger images or are otherwise experiencing lots of reflows

and repaints.

Stripey Gradients

We’ve covered most of the background images on our fake iOS application, but not all. How about the striped background of the iOS app? Do we need a GIF for that? Not so fast. As noted earlier, we can make stripes with CSS gradients. The background of the iOS app is a gradient: a striped gradient.

If you declare two color stops at the same position you will not get a color fading into another—a gradient—but rather a hard line. This is an important trick in creating shapes. For example, to make stripes you could define:

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, 0 0, 100% 0, color-stop(0.4, #ffffff), color-stop(0.4, #000000), color-stop(0.6, #000000), color-stop(0.6, #ffffff)); background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(right, #ffffff 40%, #000000 40%, #000000 60%, #ffffff 60%); background-image: linear-gradient(to left, #ffffff 40%, #000000 40%, #000000 60%, #ffffff 60%);

This gradient will go from right to left, starting white and ending white with a black stripe down the middle from 40% to 60%, as shown in Figure 9-11.

The gradient for our body background image has hard stops. For this effect, we create a hard color stop, ending the first color and starting the next color with no fade. It is a 7 px wide background image, repeated:

1 background-color: #C5CCD4; 2 background-image: 3 -webkit-gradient(linear, 0 0, 100% 0, 4 color-stop(0.7142, #C5CCD4), 5 color-stop(0.7142, #CBD2D8)); 6 background-image: 7 -webkit-linear-gradient(left, 8 #C5CCD4 0.7142%, 9 #CBD2D8 0.7142%); 10 background-image: 11 linear-gradient(to right, 12 #C5CCD4 0.7142%, 13 #CBD2D8 0.7142%); 14 background-size: 7px 2px;[62] 15 background-repeat: repeat;

Because the color stops are in the same location, the first color will abruptly “fade” into the next color, creating a hard line. Before the first stop, the color is the color of the first stop. After the last stop, the color is the color of the last stop.

The only thing with the gradient code we created in lines 2–13 is

that it created one background image that will, by default, cover 100%

of the element on which it is applied. For the background image for the

body of our web application, we need our image to tile into columns or

pinstripes. For that effect, we need to size the image and tile it both

horizontally and vertically, or at least horizontally. We do that with

the background-repeat and background-size properties.

Because we’ve declared the background size to be 7 px wide, the

background image will have a 5 px stripe of

#C5CCD4

followed by a 2 px wide stripe of #CBD2D8. We then repeated that tiny image both

vertically and horizontally. We could also have created this gradient

using pixels instead of percentages:

background-image:

-webkit-gradient(linear, 0 0, 100% 0,

color-stop(5px, #C5CCD4),

color-stop(5px, #CBD2D8));

background-image:

-webkit-linear-gradient(left,

#C5CCD4 5px,

#CBD2D8 5px);

background-image:

linear-gradient(to right,

#C5CCD4 5px,

#CBD2D8 5px);Or, instead of using background-size and background-repeat, we could instead have

created a repeating gradient with the repeating-linear-gradient() value.

Repeating Linear Gradients

CSS3 provides us with background-size

and background-repeat, which enables

us to create interesting effects, including the stripey background.

However, CSS3 also provides us with repeating-linear-gradient:

background-image:

-webkit-repeating-linear-gradient(left,

#C5CCD4 0,

#C5CCD4 5px,

#CBD2D8 5px,

#CBD2D8 7px);

background-image:

repeating-linear-gradient(to right,

#C5CCD4 0,

#C5CCD4 5px,

#CBD2D8 5px,

#CBD2D8 7px);

background-size: 7px 7px;

background-repeat: repeat;There are a few quirks to note about repeating gradients. The width of the gradient will be the value of the last color stop: in our case, 7 px. You must declare the 0 value and the last value. Unlike regular linear gradients, it does not default those values for you.

Also, not all browsers support the native sizing feature of

repeating gradients.[63] If you use repeating linear gradients, until this is

fixed, check to see if you need to include a background-size and repeat the gradient with

background-repeat, as done in lines

14 and 15.

Repeating linear gradients have similar browser support as unprefixed regular linear gradients. They are currently supported in all major browsers, since BlackBerry 10, iOS 5, Safari 5.1, and Chrome 10, with vendor prefixes still required in some WebKit browsers. As noted earlier, they don’t render correctly in Chrome or Chrome for Android. However, I often like the effect of Chrome’s poor handling of repeating linear gradients.

Gradients in CubeeDoo

Although Chrome for Android doesn’t correctly render repeating linear gradients, I’ve included a repeating gradient for the background of the CubeeDoo application. I actually like the effect of the quirky Chrome rendering, and don’t mind a slightly different background in different browsers until it is correctly supported across all browsers.

In smaller devices, the CubeeDoo board takes up the full viewport. In larger devices, the game only takes up a portion of the screen, so the background of the page on larger devices has a repeating linear gradient as a background, as does the game board:

body {

background-color: #eee;

background-image:

-webkit-repeating-linear-gradient(-135deg,

transparent 0,

transparent 4px,

white 4px,

white 8px),

-webkit-repeating-linear-gradient(135deg,

transparent 0,

transparent 4px,

white 4px,

white 8px);

background-image:

repeating-linear-gradient(-135deg,

transparent 0,

transparent 4px,

white 4px,

white 8px),

repeating-linear-gradient(135deg,

transparent 0,

transparent 4px,

white 4px,

white 8px);

}Note that we’ve actually included two gradients as two background images, creating a diamond effect across the board.

Multiple background images

How can we include two gradients? CSS3 allows for multiple background images on a single

DOM node. Simply separate the various background images, no matter

what type of images, with commas. In the preceding example, you’ll

note that in a single background-image declaration there are two

repeating linear gradients separated by a comma.

We also included two gradients as the background image for the board, creating a checkerboard effect. The gradient background of the board is so small, it doesn’t fully render in lower DPI devices, but it does create a texture for all devices:

#board {

color: #fff;

height: 400px;

width: 100%;

float: left;

text-align: center;

background-color: #eee;

background-image:

-webkit-gradient(linear, 0 0, 100% 100%,

color-stop(0.5, rgba(255,255,255,0)),

color-stop(0.5, rgba(255,255,255,0.5))),

-webkit-gradient(linear, 0 100%, 100% 0,

color-stop(0.5, rgba(255,255,255,0)),

color-stop(0.5, rgba(255,255,255,0.5)));

background-image:

-webkit-linear-gradient(-135deg,

rgba(255,255,255,0) 50%,

rgba(255,255,255,0.5) 50%),

-webkit-linear-gradient(135deg,

rgba(255,255,255,0) 50%,

rgba(255,255,255,0.5) 50%);

background-image:

linear-gradient(-135deg,

rgba(255,255,255,0) 50%,

rgba(255,255,255,0.5) 50%),

linear-gradient(135deg,

rgba(255,255,255,0) 50%,

rgba(255,255,255,0.5) 50%);

background-size: 2px;

}You’ll note that we are again declaring multiple background

images on a single node, and only one background-size value. When only one value

is declared in background-size, the

length value is for both the height and width. When there is only one

value for multiple background images, all background images will be

the same size. If the background images were of different sizes, you

would declare multiple background sizes separated by commas, with the

order of the background-size

declarations being the same order as the background-image declarations.

I recommend against using the background shorthand property, as it sets

all the background properties to their default values, even if you

didn’t intend for that to happen. If you do use the shorthand with

multiple background images, only declare the background-color on the last background

declaration.

Candy buttons and hard stops

Now that we know how to do hard stops with gradients, let’s revisit our

candy buttons. We employed the background-size property to fake a hard edge

on the gradient, but we could have used a gradient with a hard color

stop:

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, 0% 0%, 0% 100%,

color-stop(.5, rgba(255, 255, 255, 0)),

color-stop(.5, rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1)),

color-stop(1, rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4)));

background-image: -webkit-linear-gradient(bottom,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0) 50%,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1) 50%,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4));

background-image: linear-gradient(to top,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0) 50%,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1) 50%,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4));As you can see, there are many ways to skin a cat, or, in this case, handle a gradient.

Tools for gradients

Although it is important to understand how to create linear gradients (which is why we went into great detail about it), sometimes it is easier to use a tool. The online chapter resources have links to resources, tools, and gradient libraries, to help you get up and running.

You may note that we’ve included a background color. Always include a background color because your site will be viewed in browsers that don’t support gradients, you may push a typo in your gradient code, or your tile may fail to repeat itself. By including a background color, you can prevent the effect of having missing contrast between text and background in case your background image/gradient fails.

Note

If using gradients for bullets on a list item, the size of the image cannot be specified in WebKit. WebKit will default the gradient image to a size relative to the font size of the list item.

Shadows

Now that we have a good understanding of linear gradients, background-size, and

rounded corners, let’s revisit our buttons to give them more depth. We

have most of the newer CSS features down ... except for shadows and

perhaps the less commonly known text-overflow

property.

The code for our buttons includes the following:

1 .button {

2 background-color: #4A6C9B;

3 background-image:

4 -webkit-gradient(linear, 0 100%, 0 0%,

5 from(rgba(255,255,255,0.1)),

6 to(rgba(255,255,255,0.4)));

7 background-image:

8 -webkit-linear-gradient(bottom,

9 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1),

10 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4));

11 background-image:

12 linear-gradient(to top,

13 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1),

14 rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.4));

15 background-size: 100% 50%;

16 background-repeat: no-repeat;

17 color: #FFFFFF;

18 border: 1px solid #2F353E;

19 border-color: #2F353E #375073 #375073; /* T LR B */

20 border-radius: 4px;

21 text-decoration: none;

22 font-family: Helvetica;

23 font-size: 12px;

24 font-weight: bold;

25 height: 30px;

26 padding: 0 10px;

27 text-shadow: 0 −1px 0 rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.6);

28 overflow: hidden;

29 max-width: 80px;

30 white-space: nowrap;

31 text-overflow: ellipsis;

32 -webkit-box-shadow:

33 0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255, 0.4);

34 -webkit-box-shadow:

35 0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255, 0.4),

36 inset 0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255,0.4);

37 box-shadow:

38 0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255, 0.4),

39 inset 0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255,0.4);

40 }That’s a lot of code! With our great new gradient skills, most of it

(through line 26) should be familiar to you, but there may be a few

properties that you may not be familiar with, such as such text-shadow, box-shadow, and text-overflow. Fear not! We have those

covered.

I created a blue to darker blue button with a background color that shows through our translucent white gradient. Lines 18–20 create a border of different blue hues with a radius of 4 pixels. Line 15 defines the size of our gradient: the top part of the button is a gradient and the bottom has a solid background color showing through, so I defined a gradient image that is full width, but only half the height of our element.

Since the gradient image does not take up 100% of the area of the

element, it will tile vertically by default. We don’t want it to. By

declaring background-repeat: no-repeat

on line 16, the image will not repeat. Had I defined the image to have a

size of 2 px width (background-size: 2px

50%;), we would have had to repeat the image horizontally with

background-repeat: repeat-x;.

The rest, through line 26, provides for text color, typeface,

weight, and size, and removal of link underlining. While the HTML sample

code has no links, often links are styled as buttons, and links are

underlined by default. Had I used a link instead of a <li>, the links would have displayed as an

inline element by default, giving height no meaning. But, as we’re

floating our buttons in the nav, whatever element has the class of

cancel and done will display as

block.

The text-shadow on line 27 is new

to us, though not new to the CSS specification! Let’s discuss.

Text Shadow

Text shadows were added to CSS 2, and removed in CSS 2.1. They’re back! But in reverse order.

Apple likes to have their text pop. On Apple.com, they’ve created popping text by including images for their text because they want to ensure their website looks similar in all browsers. Yes, they actually have a sprite image for their navigation copy, and another image for the gray navigation bar behind it. They have us all download over 3.5 MB of images on first page load because they want to ensure that all visitors, even those on IE6 (if people aren’t paying to upgrade their 10-year-old computer, I don’t think they’re switching to a Mac) have the same experience.

In the mobile space, we don’t have to worry about craptastic

desktop browsers like older IEs not supporting text-shadows. We don’t have to include sprites

for our navigation. We can use text-shadow instead of images—keeping the

number of HTTP requests low and making internationalization much less of

a hassle.

The text-shadow property

specifies a text shadow to be added to the text content of an element.

The syntax for text-shadow values is

a space-separated list of leftOffset,

topOffset, blur, and shadow-color. The two shadow offsets are

required. The blur radius and color values are optional:

text-shadow: <leftOffset> <topOffset> <blurRadius> <color>[,

<leftOffset> <topOffset> <blurRadius> <color>][,

<leftOffset> <topOffset> <blurRadius> <color>];There are two offset length values: (1) the horizontal distance to the right of the text if it’s positive, or to the left of the text if the value is negative, and (2) the vertical distance below the text if it is positive, or above the text if it is negative.

The third value defines the width of the blur. The larger the blur value, the bigger the blur, making the text shadow bigger and less opaque. Negative values are not allowed. If not specified, the blur radius value defaults to zero, creating a sharp shadow edge.

The offsets are required, but they can be set to zero. If they are

both set to zero, the shadow will be a glow, showing evenly on all

sides. This feature, along with currentColor (see Chapter 8) can be used to your

benefit.

Some fonts, like Helvetica Neue Light, when viewed in high DPI devices, are too thin to read. By declaring:

text-shadow: 0 0 1px currentColor;

the text can be made more legible. The one line of CSS creates a 1

px glow directly behind the text in the current color of the font. By

using currentColor, you can make a single property/value declaration for all

your text without worrying about different elements having different

color text.

When multiple shadows are included, the shadow effects are applied in the reverse order in which they are specified: the last shadow is drawn first and each preceding text shadow is placed on top of it.

Text shadows can be created to be very, very wide. Even so, a text shadow has no effect on the box model. A text shadow can increase beyond the boundaries of its parent element without increasing the size of that element’s box. Because of this, if you put a very wide negative horizontal offset, you may inadvertently cover the preceding text (there is an example in the online chapter resources).

A trick to good-looking text shadows is to include a blur value

and to provide a slightly transparent version of the shadow color,

generally rgba(0,0,0,0.4); for a

slightly gray shadow. While seemingly gray, the translucent black allows

for background colors/image to show through the shadow.

However, I am not a designer. And I am definitely not Apple’s

designer. Apple appears to use a one pixel dark-gray top shadow. We add

this to page title (the <h1>)

and to our buttons on our Languages page to make the text pop:

text-shadow: 0 −1px 0 rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.6);

The preceding code provides for a 1 px text shadow sitting on top of the letters that is slightly transparent.

Note

Note that text-shadow is

not a prefixed property. Also note that large

translucent shadows combined with other CSS properties can take a long

time to paint and can use up memory.

Fitting Text with width, overflow, and text-overflow

Lines 28 through 31 of our code example above ensure

that the button does not take up too much room. We have very limited

space on our mobile devices. In our Languages example, we are trying to

fit three elements in that top navigation area: two buttons and the page

title. So, we need to ensure not only that the buttons don’t take too

much space, but that our h1 isn’t too

wide either. “Languages” fits here, but what if our page title were

“Supported Languages”?

Generally, declaring a width on an inline element, like <button>, has no effect. However, since

we’re floating our buttons, visible floated elements are default

displayed as block (instead of list-item, inline, inline-block, etc.), so width works!

text-overflow property

The text-overflow property

is part of the Basic UI specification. The text-overflow property allows you to clip

text that is too wide for its container. The ellipsis value causes ellipses, or three

periods, to be appended to the text at the point where it is

clipped:

text-overflow: ellipsis | clip

Employing text-overflow:

ellipsis; is not enough to cut off text and include

ellipses. If the text wraps or is allowed to extend beyond the

boundaries of the containing block, then the words won’t be cut off

and the ellipses will not appear.[64] Ellipses will only appear when the containing box has

overflow set to something other than visible (visible allows the text to flow out of the

box) and white-space set to

nowrap or pre. You can also use the clip value, which will clip the text but

without putting ellipses.

By using the ellipses key

term, the clipping will occur after whatever last letter can

completely fit into the parent box. There has been discussion about

breaking on specific characters rather than letters. Firefox has

included this experimental string

value since Firefox 9.

While you really should never clip text, the limited real estate on the navigation bar of a mobile application often requires it. It is generally not good user experience design to hide text in this (or any other) way. If you are going to clip text, use ellipses to improve user experience. The ellipses informs the user that text has been clipped:

h1 {

white-space: nowrap;

width: 180px;

overflow: hidden;

-o-text-overflow: ellipsis; /* opera mini, mobile */

text-overflow: ellipsis;

}The white-space, overflow, and, generally, width properties have to be declared for the text-overflow property to work, which means

it doesn’t work on elements that are displayed inline.

white-space property

The white-space property

specifies how whitespace inside an element is handled.

Values for the white-space property

include normal, nowrap, pre, pre-line, pre-wrap, and inherit. When set to normal, text will wrap at the end of the

line, and whitespace will be reduced to a maximum value of one space.

Setting the value to nowrap will

force the text to not line break to fit the width of its parent

container. The prewrap is often

more legible than nowrap: while it

maintains or preserves the original whitespace, it wraps when it

reaches the end of its containing block.

For text-overflow: elipses;

to work, the text can’t wrap. This is why we have included this CSS 1

feature here.

Box Shadow

Box shadows are most noticeably used to create drop shadows to make elements

pop off the screen. In CubeeDoo, we use box-shadow to make the cards pop off the board

a bit. In our effort at creating a CSS3 native iPhone application look,

we employ the box-shadow property to

create two subtle shadow effects on the buttons.

The box-shadow property enables

the developer to add drop shadows or inset shadows, or both, to

elements. One or more box-shadows can

be attached to a box, by which you can create some pretty nifty effects.

Shadows are drawn just outside the border, or just inside the border in

the case of inset.

In terms of the box-model,

shadows are similar to outline and

text-shadow, in that they do not

influence the layout: they may overlap other boxes. It is supported in

all browsers starting with IE9. Include the default vendor-less syntax

and the -webkit- vendor prefix

version for Android 3.0 and iOS 5.

The syntax and rendering of box-shadow is similar to text-shadow, but with two additional optional

features, blur spread and inset:

box-shadow: inset <leftOffset> <topOffset> <blurRadius> <spread> <color>[,

inset <leftOffset> <topOffset> <blurRadius> <spread> <color>][,

inset <leftOffset> <topOffset> <blurRadius> <spread> <color>];The values for box-shadow

property include none for no shadow

(the default), or a list of space-separated values for left-offset,

top-offset, blur radius, spread radius, and color, with the optional

inset keyword for inner shadows

(versus drop shadows). If more than one box shadow is to be included,

separate each shadow with a comma.

The vertical and horizontal offset values are both required.

Similar to text-shadow, the first

three values define the horizontal position, vertical position, and blur

radius in that order. The fourth value—the blur spread—makes the shadow

grow bigger if positive, and shrink if negative. The inset key term, if included, makes the shadow

an inset shadow instead of a drop shadow. The inset key term, blur radius, blur spread, and

color values are optional.

Note that inset is only an

option for box-shadow and is not part

of text-shadow. Also note that

Android up to 3.0 and iOS 3.2 require the -webkit- vendor prefix, and do not support the

inset values. iOS 4.x and Blackberry

7 require the -webkit- vendor prefix

as well, but support inset shadows.

For example (not from the online chapter resources):

1 -webkit-box-shadow: 2 3px 4px 5px 6px rgba(0,0,0, 0.4); 3 -webkit-box-shadow:[65] 4 3px 4px 5px 6px rgba(0,0,0, 0.4), 5 inset 1px 1px 1px #FFFFFF; 6 box-shadow: 7 3px 4px 5px 6px rgba(0,0,0, 0.4), 8 inset 1px 1px 1px #FFFFFF;

Within each grouping we have two comma-separated box shadows. The values making up each of the two box shadows is a space-separated list, including:

The left or horizontal offset of the shadow is the first length value. A negative value will put the shadow on the left.

The top or vertical offset is the second length value. A negative value will put the shadow above the box.

The optional blur radius is the third length value. Negative values are not allowed. If it is 0, the shadow is solid. The larger the value, the blurrier the shadow will be.

The optional blur spread is the fourth length value, if it is present. Positive values make the shadow grow bigger. By default, the shadow is the same size as the element.

The optional color. Using alpha transparency is recommended if your blur radius is greater than 0, as the effect is much prettier if you start from a slightly transparent version of black than if you start with an opaque version of gray. However, translucent shadows use more memory and can take longer to paint, which is an issue on devices with limited RAM or if you’re animating and/or repainting the element frequently. If the color is not defined, browsers will by default use

currentColor.The optional

insetkey term, if present, will create an inset shadow instead of a drop shadow.

In our example, the first shadow will be a 5 px wide gray

transparent shadow on the bottom right of the element. The second box

shadow value in each grouping includes the optional key term inset. This second shadow will be a fully

opaque white 1 px outline (or inline?) on the inside of the box. The

shadows appear on the outside and inside of the border, if there is one,

respectively.

The values of the x-offset, y-offset, and optional blur radius and

spread radius need to be written in that order. The order of the last

two values in the declaration (inset and color) location aren’t

important, but keep the order consistent for ease of reading and

maintenance. The order of shadows when including multiple shadow values

does make a difference. Similar to text-shadows, box-shadows are drawn in the reverse order of

their declarations. Drop shadows are always drawn behind the box, as if

it had a lower z-index, and do not show through

alpha transparent boxes (unlike alpha transparent text, where text

shadows show through), as shown in the online chapter

resources.

A thick border with an inset shadow can make for an interesting effect, but animating a large translucent shadow can actually crash a browser, as all shadows, images, and gradients are calculated and painted to the screen from back to front, even if they are never made visible to the user.

Warning

On mobile, all properties are drawn to the page even if not visible. Be warned that if you add 20 shadows and gradients, even if they are overlapping, beyond the confines of the page, under another element, or otherwise not visible, they are still painted. Repainting 20 layers and calculating the added effect of transparencies on each pixel may take too long to animate at 60 fps.

While shadows have been supported since the first iPhone, shadows can use a lot of memory and can hang the browser, especially if the shadows are semitransparent (versus opaque), and even more so when the element on which the shadow is set is animated. The browser must recalculate each pixel on each repaint, even if the shadow is not visible.

Warning

In mobile browsers, large shadows, especially inset shadows, use a lot of memory and can hang the browser.

Lines 37–39 of our CSS for the candy buttons include a double shadow:

box-shadow:

0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255, 0.4),

inset 0 1px 0 rgba(255,255,255,0.4)This declaration will include two semitransparent white shadows: a

1 px shadow on the outside bottom of the box and a 1 px shadow inside

the button, at the top of the box. We also declared this with the

-webkit- prefix with two shadows and

also with the inset shadow removed for very old Android browsers.

Putting It All Together: CubeeDoo

We have several shadows in CubeeDoo. Here are some excerpts from the CSS. This is not all the code that is in the CSS files. I am only including the selectors, properties, and values that should make sense to you up to this point:

1 #board > div {

2 box-shadow: 1px 1px 1px rgba(0,0,0,0.25);

3 }

4 .back {

5 border: 5px solid white;

6 }

7 .back:after,

8 .face:after {

9 position: absolute;

10 content: "";

11 top: 0;

12 left: 0;

13 right: 0;

14 bottom: 0;

15 border-radius: 3px;

16 pointer-events: none;

17 }

18 .back:after {

19 background-repeat: no-repeat;

20 background-color: #fff;

21 background-size:

22 50% 50%,

23 0 0;

24 background-image:

25 url('data:image/svg+xml;utf8,<svg width="40" height="40"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"><g><text xml:space="preserve"

text-anchor="middle" font-family="serif" font-size="40" id="svg_1"

y="30" x="20" stroke-width="0" stroke="rgb(119, 160, 215)"

fill="rgb(119, 160, 215)">❀</text></g></svg>'),

26 -webkit-linear-gradient(-15deg,

rgba(0, 0, 0, 0), rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.05));

27 background-image:

28 url('data:image/svg+xml;utf8,<svg width="40" height="40"