Geography, Climate, and People

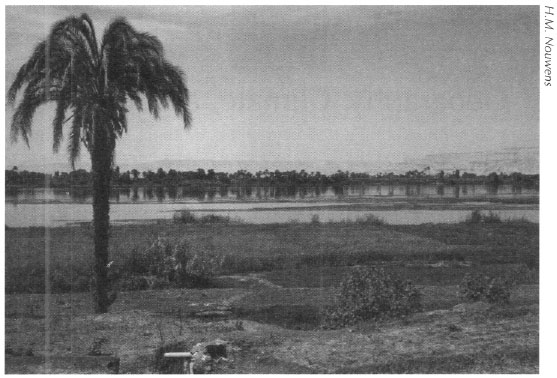

Egypt lies in northeastern Africa and, including the Sinai Peninsula, covers an area of approximately 1,002,000 square kilometers (Pl. 2.1). The major geographical feature, which allowed Egypt to prosper for thousands of years, was the Nile (Fig. 2.1), one of the longest rivers in the world. Its sources include Lake Tana in Ethiopia for the Blue Nile, and Lake Victoria, which borders Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania, for the White Nile. These join at Khartoum. The third branch is the Atbara River, which originates in northern Ethiopia and meets the Nile near a city of the same name. From there all three branches flow northward, as one, into Egypt. In Egypt the river valley itself is divided into Lower Egypt (the Delta region in the north) and Upper Egypt to the south. The Nile flooded every year starting in late summer and early autumn, covering the valley with a layer of fertile silt and clay. When the floods receded, leaving riverine sediments deposited on the floodplain, farmers rejoiced; their fields had been naturally fertilized. The ancient Nile-centric Egyptians called the Nile Valley, where most of them lived, the ‘Black Land’ (Kemet).

The Nile River divides Egypt into eastern and western portions, both of which are deserts. West of the Nile lies the Western Desert or the Sahara; to its east stretches the Eastern Desert. These deserts, which the valley inhabitants called the ‘Red Land’ or Desheret, cocooned and protected them from numerous invasions. The deserts, however, also initially prevented Egypt from experiencing as much commercial, religious, or intellectual interaction with her neighbors as the other early Near Eastern river valley civilization in Mesopotamia.

Fig. 2.1: View of the Nile, one of the longest rivers in the world.

The geography and geology of the Eastern Desert must be seen within the context of the Red Sea (Pl. 2.2) that forms its eastern edge, and the Nile River valley, which acts as its natural western boundary (Pl. 2.3). The Red Sea is a relatively recent creation in geological terms, about twenty-five million years old. It appeared when two of the earth's tectonic plates, which now comprise the African and Arabian landmasses, drew apart, resulting in a long, narrow, and almost totally enclosed salt lake. Today the Red Sea is about 2,250 kilometers long and, at its greatest, about 355 kilometers wide. The maximum depth ever recorded is 2,850 meters. Its only natural outlet is at the Bab al-Mandab (Gate of Tears), an approximately twenty-nine kilometer-wide strait between Yemen and Djibouti, into the Indian Ocean.

The littorals of the Red Sea are deserts with few good locations for large natural harbors. Those few marsas (anchorages) that eventually and temporarily metamorphosed into harbors were formed when seaward ends of valleys were flooded by rising sea levels at the end of the Ice Age (about twelve thousand years ago). The murky marine environments they created precluded the growth of fringing coral reefs or killed off those that had once flourished there. This resulted in natural breaks in the reefs, which were attractive lures for sailors seeking refuge from the strong prevailing northerly winds and dangerous shoals and reefs of the Red Sea. Yet, these marsas were themselves doomed. Sediments prevented coral growth, but if unchecked, they also eventually inundated the harbors themselves rendering them so heavily silted and shallow as to become useless as places of refuge except for the smallest boats, such as occurred at Berenike, a Ptolemaic-Roman harbor along the Red Sea coast in southeastern Egypt.

From the floral and faunal points of view, the Red Sea would seem a northern extension of the larger Indian Ocean and, to some extent, it is. Yet there are forms of marine life unique to the Red Sea suggesting an evolutionary trend that sets it somewhat apart from the Indian Ocean. As a result of the creation of the Suez Canal in the nineteenth century, some Red Sea fish species have appeared in the Mediterranean and a lesser number of Mediterranean fauna migrated into the Red Sea. Despite its relatively young geological age—and until recently the dearth of densely inhabited coastal areas—and poor natural harbors, the Red Sea is probably one of the earliest large bodies of water noted in the surviving written records of human history.

The Eastern Desert has more in common geologically with the Sinai Peninsula and the Negev than with the Western Desert. Between the Wadi ‘Araba and Wadi Sha‘ayb in the north, today crossed by the seldom used crumbling paved highway between Za‘farana on the coast and the Nile at al-Krymat opposite Beni Suef, and the Sudanese border in the south, the Eastern Desert encompasses an area of about 220,000 square kilometers, which is approximately equivalent to the size of Italy or the American state of Minnesota or Utah. Red Sea coastal plains in the northern and central areas vary dramatically in width from only several hundred meters or less up to fifteen kilometers or more before reaching the multi-hued red and black granite mountains that form the watershed between the Red Sea and the Nile (Pl. 2.4). These, in turn, give way in many, though not all, instances to a riverine plain in the west, or occasionally sandstone or limestone shelves that lead down to the Nile.

Farther south along the Red Sea coast, somewhere between Berenike and Shalateen, about ninety kilometers south of the former, the sharp and craggy mountains of the northern and central parts of the Eastern Desert eventually become large, open plains punctuated by low, flat plateaus and isolated hills and mountains that are scattered some distance apart from one another across a barren, flat landscape.

Until the beginning of the middle Miocene (about 15 million years ago) the Red Sea hills were stripped of their sedimentary cover. During the early Miocene (beginning about 24 million years ago) these hills must have formed a formidable mountain range. By the middle Miocene the Gulf of Suez area overflowed into the Red Sea. During the late Miocene (about ten million years ago) the lowering of sea level and desiccation of the Mediterranean Sea, with which the Red Sea was connected, severed the Red Sea from the world's oceanic system and converted it into a series of lakes. The Pliocene (5,300,000–1,600,000 years ago) saw a marine transgression from the south, which reached only the southern part of the Gulf of Suez. During the late Pleistocene sea level reached at least three different phases ranging from about one to eleven meters above modern sea level and it was still one meter higher in early recent times (the Holocene Age: about 6500–4500 BC).

By about five thousand years ago the Eastern Desert was in the final stages of becoming the desiccated, hyper-arid region that we know it as today. This was the result of the receding glaciers of the last Ice Age. Thus, the Eastern Desert is a relatively new climatic entity though its sedimentary and volcanic igneous bedrock predates one hundred million years, and its plutonic igneous and metamorphic ‘crystalline basement’ exceeds 550 million years in age.

As a result of desertification, the savanna fauna of Egypt, including elephant, giraffe, and rhinoceros, disappeared before the Pyramid age beginning in the Third Dynasty (2649–2575 BC). Today, sporadic heavy rains falling in the mountains of the Eastern Desert, and occasionally along the coast, especially in November and December, and the residues of that moisture that either temporarily pool on the surface or percolate down into subterranean strata, are the major sources of water for plants, animals, and humans. Where recorded in the region of Quseir on the Red Sea, average annual precipitation is a paltry four to five millimeters. On those rare occasions when the rains are heavy, huge pools and waterfalls transform this mountain and desert landscape. Floods of great strength, called seyul, spew torrents of water down through the wadis (Fig. 2.2) carrying everything in their path. They are death traps for any living thing unfortunate enough to be there. Yet, the immediate after effects are a blossoming of the desert with ephemeral verdant covering, spotted here and there with bright yellows and hues of purple, blue, red, and orange. Sometimes myriads of butterflies briefly appear as miraculous by-products of these torrential downpours and the resultant greening of the desert. Yet the enervating heat and hyper-arid climate soon reclaim the region. Even so, tough and resilient trees like the acacia, and scrub bushes can be found here and there throughout the desert even during the driest periods; these are mainstays of existence for the nomads who dwell here with their camels, donkeys, and herds of goats and sheep.

Fig 2.2: Wadi Nugrus in the Eastern Desert.

With a modern measurable 2,500-millimeter per annum evaporation rate—and it was probably much the same throughout most of the pharaonic period (3000–332 BC) and certainly in Ptolemaic (304-30 BC) and Roman times (30 BC-AD 641/642)—it is no surprise that any humans living in the Eastern Desert had to learn very quickly how to find, protect, store, and distribute water in the most careful and efficient manner possible. It followed that, aside from the indigenous peoples, it would be a highly centralized power that seized control of the principal water sources and the routes emanating to and from them. This tight regulation of the desert by the central government reached its acme during Ptolemaic times and especially during the Roman period.

People long resident in the Eastern Desert from Paleolithic times (about 250,000-10,000 BC) on had discovered the best routes, the most dependable sources of water, the habits and haunts of the animals that they stalked, and the optimal places to live. Later travelers and inhabitants of the area into the Roman period and later made repeated use of the tracks and water supplies exploited by their prehistoric and other more immediate antecedents.

Roads from the pharaonic period followed along paths established and preferred by their Paleolithic, Mesolithic (about 10,000-5000 BC), and Neolithic (about 5000-3400 BC) predecessors; we know this from the survival side-by-side of clearly prehistoric with dynastic graffiti and petroglyphs. Ptolemaic and Roman period roads continued expanding into the region, with soldiers, merchants, quarrymen, miners, and others traveling, exploiting, and living there with increasing regularity and in ever-growing numbers. These terrestrial lines of communication in the northern and central regions of the Eastern Desert crossed in a general east-west pattern, not broad expanses of flat desert plains for the most part, but rather followed wadis, the easiest routes winding through natural passageways amid the peaks of igneous and metamorphic rocks. The mountains in this area range, in general, from about one thousand to 2,200 meters in height, Gebel Shayib al-Banat, southwest of Hurghada, being the tallest (2,187 meters).

It was from the Nile Valley that the earliest recorded explorers entered the Eastern Desert in Paleolithic times. Initially, they sought stones with interesting colors or patterns to make vessels, small figurines, and jewelry. Those peoples, predominantly of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic periods, and their descendants hunted, made stone tools and weapons, and left crude drawings of animals, mainly gazelle and ibex-like quadrupeds, ostriches and, later, sickle shaped boats, chipped into the rock faces of places they frequented attesting their presence and passing.

At first glance, to those living in the Nile Valley during the pharaonic period, the adjacent deserts were vast, empty, uninviting, and even dangerous. Deserts were places where wrongdoers were sent to perish as exiles or as forced workers in mines or quarries and were also regions of the dead where cemeteries were located. Religion especially linked the Western Desert with the land of the dead; it was regarded as the entrance to the underworld where the sun disappeared each night. The deserts in general were associated with disorder and forces hostile to creation. Seth, the traditional Egyptian god of chaos, received the epithet ‘red god,’ since he was said to rule over the deserts and the general disorder that they represented, as opposed to the vegetation and fertility of the Nile Valley which were associated with the god Osiris, Seth's mythical counterpart.

Yet the Eastern Desert formed an unavoidable bridge linking the Nile to the Red Sea whose exploitation followed beginning in the late Predynastic period (before about 3000 BC). Furthermore, the Egyptians knew that the Eastern Desert, a forbidding and otherwise frightening place, was a repository of valuable caches of mineral wealth, which were irresistible draws for them. The god-kings of Egypt understood that the Red Land had varieties of hard stones, mainly volcanic porphyries and other colorful rock types, and gold, copper and iron, and gems, especially amethyst and beryl/emerald, which provided them and their subjects with raw materials they could not live without. Especially favored were metagraywacke and metaconglomerate from Wadi Hammamat (from Early Dynastic to Roman times) and dolerite porphyry from Rod al-Gamra. The latter was quarried, apparently, only in the Thirtieth Dynasty (380-343 BC). These stones were needed to erect both massively impressive and also smaller more or less permanent monuments to the glory of the pharaohs: lithic religious and funerary memorials and their sculptural decoration in and close to the Nile Valley that aggrandized their reigns. Trekking into the desert to acquire these raw materials became, although eventually commonplace, always an ordeal most preferred to forgo.

With the political unification of the Two Lands, Upper and Lower Egypt, beginning in about 3000 BC, and from the Archaic period (Dynasties One-Two, about 2920-2649 BC) and Old Kingdom (Dynasties Three-Six, about 2649-2152 BC) on, incursions into this barren and forbidding ‘Red’ Land of the Eastern Desert from the comfortable, fertile, and vibrant ‘Black’ Land of the Nile Valley seem to have been mainly at the urging of the pharaohs. Throughout the Middle (2040-1640 BC) and New (1550-1070 BC) Kingdoms and continuing until Roman times and later, these quarrying expeditions into the Eastern Desert grew in size and number as more sources of ornamental stones, together with gold and other metals, were exploited on a larger scale. These geological riches commemorated the power and prestige of the rulers and the state and supplied the necessary wealth to afford both these expeditions themselves and those of conquest into the more southerly reaches of the Nile and into the eastern Mediterranean.

The Ptolemies, a foreign dynasty founded by one of Alexander the Great's Macedonian generals, ruled Egypt for about three centuries beginning in the late fourth century BC. During that time the status of the Eastern Desert changed dramatically. Ptolemaic interest in the region was more pervasive and a permanent infrastructure was created to deal with increased and more frequent exploitation of the geological wealth of the area. The trans-Eastern Desert highways also served intrepid entrepreneurs seeking other merchandise in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, especially at this time aromatics and spices. Diplomatic embassies passed between Ptolemaic Egypt and other Hellenistic states in the Eastern Mediterranean and Aegean on the one hand, and Arabia and India on the other, but we do not know how important such contacts might have been to any of the parties involved.

The Ptolemies, most notably Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BC), builder of the famous lighthouse at Alexandria, and his immediate successors especially needed the gold of the region to pay for their political and military endeavors within Egypt and particularly throughout the eastern Mediterranean. It was in this latter area that the bulk of their efforts were focused against other former generals of Alexander who had also embarked on their own dynastic state-building aspirations. The major Ptolemaic opponents in the Near East were, initially, the Antigonids, led by Antiginous Monapthalmous (the One-Eyed) and his son Demetrius Poliorcetes (Besieger of Cities) and, after 301 BC, the Seleucids.

In addition to gold, the Ptolemies also believed that their armies required elephants, a species then unavailable in Egypt, but found in relative abundance to the south in areas of what are today Sudan and Eritrea. Soldiers from the Mediterranean discovered in the course of Alexander the Great's conquests in the east during the 330s and 320s BC and his battles with Indian and other forces, that elephants could be effective weapons of war, the armored units of their day. The huge expense and logistical organization required to secure, transport, and train the beasts, and the otherwise increased commercial and naval activities of the Ptolemies in the region, necessitated that various Red Sea ports in Egypt be joined to the Nile with roads and support facilities.

The Ptolemies are reported to have had a massive Mediterranean fleet of several thousand ships with which they retained an empire stretching into the northern Aegean Sea and including parts of mainland Asia Minor and Cyprus. These regions supplied critical timber for shipbuilding, copper (the primary component of bronze) and other important raw materials required by their military. Portions of the Levantine coast of what are today Israel and Lebanon changed hands periodically between the Ptolemies and their most potent and long-term adversaries, the Seleucids. It was in this arena that the mighty Ptolemaic fleet and its elephant phalanxes were dispatched.

A number of ancient authors including Theophrastus from Lesbos, an island in the Aegean, Agatharchides of Cnidus, a city in Asia Minor, and Diodorus Siculus, from Sicily as his name implies, provide details about the Red Sea, and the coastal and inland areas of the Eastern Desert in Ptolemaic times. Their writings, some of which are now lost, and those of other Ptolemaic period authors, are preserved in some instances only in later Roman accounts. Theophrastus, a student of the philosopher Aristotle who lived throughout much of the fourth and into the early third century BC, discussed minerals derived from the Eastern Desert. Agatharchides, although writing in the second century BC, used mainly sources from the previous century when penning his book, On the Erythraean Sea, as the Red Sea was then called. He is a font of information and lore about the peoples dwelling along the Red Sea littoral and his stories have an anthropological ring to them. Diodorus visited Egypt in the middle of the first century BC and left some fascinating descriptions of the Eastern Desert in his day in his book Bibliotheka. Of special interest to us is Diodorus’ detailed account of Ptolemaic period gold mining activities in the Eastern Desert. There are also numerous inscriptions carved on stone, texts on papyri, and records on ostraca (broken pottery shards or flakes of limestone) from the Ptolemaic period that provide copious information on various facets of the Eastern Desert.

In the Roman period, which began after the suicides of Marc Antony and Cleopatra VII in 30 BC and the Roman Emperor Octavian-Augustus’ annexation of Egypt, the main interests in the Eastern Desert were mining, quarrying, and international trade. The Romans sought especially gold and hard stones. The latter were hauled with great effort across the desert to the Nile Valley and from there downriver via Alexandria to far-flung corners of the empire to decorate temples and other buildings in Rome, Constantinople, and lesser imperial metropoleis. Extensive archaeological remains and accounts of a number of ancient authors reveal how important mining and quarrying in the Eastern Desert were to the Romans.

The international trade that passed through the Eastern Desert onward to the Nile and Mediterranean from the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea ports especially fascinated some Roman-era authors. They also reported on the names, customs, and physical appearances of peoples living along the coast and in the desert itself. Of particular importance in the history of the Roman occupation of Egypt are several early and late Roman period authors whose ‘books’ survive. One is Strabo who wrote his lengthy Geography in the few decades before and during the Christian era. The encyclopedist Pliny the Elder composing his Natural History in the 50s to 70s AD and dying in the same eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in August AD 79 that buried the Italian cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, is a great source for anyone interested in the Rome-India trade, and in the Eastern Desert and the mineral wealth of the area.

The anonymously authored Periplus of the Erythraean Sea appeared about the middle of the first century AD. It is a handbook written, likely, by a knowledgeable and experienced sea captain or merchant detailing the ports, peoples, and products of many emporia in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. One later savant, Claudius Ptolemy, who wrote The Geography sometime in the middle of the second century AD, provided latitudes and longitudes for the thousands of places he listed from northwest of Britain to Southeast Asia. He is most knowledgeable, of course, about the Roman Empire, but because he underestimated the circumference of the earth by about twenty-five percent, his locations are inaccurate. Yet his was, perhaps, the most detailed account of the location of ancient ports of the Red Sea and he is the only surviving ancient author who reports an emporium called Leukos Limen, somewhere on the Egyptian coast, which has never been conclusively located or identified. Subsequently, maps and itineraries of other authors appeared, the most famous of the latter being the Antonine Itinerary and the Peutinger Table. The latest ‘ancient’ itinerary that includes the Eastern Desert is the so-called Ravenna Cosmography, the compiler or compilers of which clearly had no firsthand experience with the Red Sea or the Eastern Desert and undoubtedly simply cribbed their data from earlier sources. Other late Roman period authors like the Theban Olympiodorus in the fifth century AD and the court gossip Procopius, writing during the reign of the famous emperor Justinian I (527-565), provide insights into the peoples dwelling in the Eastern Desert in their day and earlier and the relationships these ‘Barbarians’ had with Roman authorities. Accounts of the mid-sixth century monk Cosmas Indicopleustes (One who sails to India) in his book Christian Topography deal with ports in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean and while his descriptions in some cases are somewhat fanciful, they cannot be totally dismissed.

Controlling the Eastern Desert

From pharaonic times on, the central authorities controlling the Nile Valley always found it difficult to impose their will on the desert regions. Thus, it was the ideal place for bandits, malcontents, tax evaders, the religiously or politically persecuted, and others to escape the long and often repressive arm of the law. It is fairly clear even in the Ptolemaic and Roman eras that complete domination of the desert was never achieved and, in fact, was deemed impossible by any central power. Placement of the various forts indicates that the Ptolemaic and Roman governments sought only to control the main lines of communications, major sources of water and important nodes of mineral wealth. Monitoring those passing through the region was important, but control of the entirety of this vast area was impractical and unnecessary. This left many of the indigenous peoples relatively free to do as they pleased.

In pharaonic times desert inhabitants such as the Medjay caused problems and later in the Roman period, groups such as the Blemmyes and the Nobadae appear repeatedly in the writings of ancient authors as openly challenging the Nile-based authorities. Occasionally, these seemingly nomadic groups attacked and occupied important cities along the Nile or major mining regions of the desert and possibly one or more of the Red Sea ports, too. The authorities never completely or permanently subdued them. This did not mean that all contacts between the desert dwellers and the ‘outsiders’ were necessarily confrontational. Occasionally we have evidence that some type of modus vivendi existed, which had either been formally ratified by treaty or had been a de facto arrangement, which was in all parties’ best interests.

Movement across the Eastern Desert was never easy even at the height of the Roman occupation. Unpaved roads and lack of milestones made travel more risky than in other parts of the Mediterranean world at that time, and modes of transport were limited to human pedestrian traffic, donkeys, and later camels and horses. Although wheeled transport was used in the Roman period, it was mainly, though not exclusively, confined to hauling quarried stone to the Nile especially from the large sites of Mons Porphyrites and Mons Claudianus in the central parts of the desert. Some wagons and chariots carrying water, provisions and passengers are known to have traveled along a road between the Nile at Coptos (modern Quft) and the Red Sea near Quseir. Each type of transport had its advantages. Wagons could carry heavy loads, but required large numbers of draft animals, were very slow, might bog down in sand, and could not negotiate steep terrain; wheels could break leading to long delays or abandonment of heavy cargoes.

Modern Interest in the Eastern Desert

There was some early modern ‘western’ interest in and exploration of both the Eastern Desert and the Red Sea coast from at least the sixteenth century when the Portuguese naval commander Dom João de Castro (1500-1548) recorded his journeys. Yet, most investigations of the flora, fauna, geology, indigenous human inhabitants, and ancient ruins in the region have taken place during the past two centuries or so. The interest really began after the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, late in the eighteenth century. Accompanying his army was a separate contingent of scientists and artists who studied and recorded as many of the antiquities as they could. Publication of their research soon thereafter in Europe under the title Description de l‘Égypte opened the floodgates to other explorers eager to learn more about Egypt. Understandably, most concentrated their efforts on the impressive monuments in the Nile Valley; these were, relatively speaking, easily accessible and offered a wealth of opportunity to study and remove to Europe the more interesting remains. Though some of these men ventured into the deserts, the remote, empty, and inhospitable arid zones were not major attractions. Initially, many European travelers to the Eastern Desert had been commissioned by the Egyptian government to locate sources of gold and precious gemstones, such as emeralds, in order to renew their exploitation for the benefit of the state. This was especially so when Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha ruled Egypt in the early part of the nineteenth century. Sometimes, these Europeans explored the region specifically for antiquities and were financed by wealthy patrons or from their own proceeds and were not officially backed by political power brokers in Cairo.

There are a number of travelers whose importance to any discussion of the Eastern Desert cannot be overlooked. These include J. Bruce, F. Cailliaud, G.B. Belzoni, G. Forni, L. de Bellefonds, J.G. Wilkinson, J. Burton, J. Wellstead, G.B. Brocchi, Hekekiyan Bey, K.R. Lepsius, G.A. Schweinfurth, W.S. Golénischeff, A.E. P. Weigall, G.W. Murray, E.A. Floyer, D. Meredith, L.A. Tregenza, and the geologists T. Barron and F.W Hume. Each of these men made important contributions to our understanding of various aspects of the Eastern Desert providing insightful observations on the flora and fauna, the geology, the indigenous populations, and the ancient archaeological remains. Many of them made etchings, drew plans, and took measurements of ancient remains and, later on, took photographs. While some of these travelers, like James Burton, seldom if ever published their notes and those now linger forgotten in libraries throughout Europe-Burton's are in London-others wrote books and articles on the results of their explorations for scholars and the general public. Their credibility is not uniformly good as some clearly obtained at least some of their information from second or third hand sources (Bruce) or mistakenly located on maps sites they had visited (Bellefonds), or made fanciful rather than accurate drawings of what they had seen (Cailliaud). None of these men really engaged in what we would call scientific archaeology today for few attempted any actual controlled and fully documented excavations aside from clearing a few grandiose looking structures here and there. The importance of what they accomplished lies more in their noting the existence of these places and drawing what they saw or thought they had seen. Perhaps unconsciously, they left it to scholars of the last half of the twentieth and early part of the twenty-first centuries to excavate and provide detailed analyses of the histories of these remote and hauntingly beautiful desert remains. In a number of cases we have found ancient ruins that they overlooked.

James Bruce was born in Kinnaird, Stirlingshire in 1730. He abandoned the study of law for a life of adventure. He traveled to Spain and Portugal, and married and became a widower within a year. After his wife's death he studied Arabic and the classical languages of Abyssinia, and resolved to travel to the source of the Nile. Bruce arrived in Egypt in 1765 and visited the Valley of the Kings where he partly cleared the tomb of Ramesses III (1194-1163 BC). He also traveled to areas of the Egyptian Red Sea coast and Eastern Desert and published his findings in a book with the lengthy title of Travels between the Years 1765 and 1773, Through Part of Africa, Syria, Egypt and Arabia, into Abyssinia, to discover the Source of the Nile. His detailed accounts of Abyssinia reflect firsthand knowledge, but some of his descriptions of regions of Egypt's Eastern Desert, especially those around the beryl/emerald mines of Gebel Sikait are more suspect; they may well be based on second and thirdhand reports. Needless to say, he failed to discover the source of the Nile. James Bruce, who had survived disease, the desert, and the dangerous politics of warring African kingdoms, died in Scotland in 1794, after falling down a flight of stairs.

Archaeological and Anthropological Work in the Eastern Desert

There is a modem popular belief that the Eastern Desert is desolate and devoid of any significant archaeological remains. Yet this hyper-arid region is, quite the contrary, the repository of many hundreds of archaeological sites dating from Paleolithic to Roman times and later. The earliest remains are burials and caves containing lithic tools. Later there are ancient quarries and mines. Especially abundant are the myriads of Ptolemaic and especially Roman remains in the form of roads, thousands of kilometers worth and all unpaved, mines, quarries, ancient forts (called by the Romans praesidia), many if not most of which protected wells (called hydreumata by both Greek and Latin speakers), and water catchment and storage tanks and cisterns (called lakkoi in Greek and lacci in Latin). Additionally, later Christians escaped to the Eastern Desert to form monasteries and other communities.

Archaeological work in the Eastern desert after 1960 was slow to take off. Some investigations took place during the decades of the 1960s and 1970s, but it was really during the course of the 1980s that there was increased interest in the archaeological remains of the Eastern Desert. This accelerated during the 1990s and continues, albeit on a smaller scale, in this decade. Unfortunately, work in the area today is greatly hampered by both logistical and financial considerations and the acquisition, frequently difficult or impossible, of permits from the necessary authorities. More easily accessible sites along the Red Sea coast or on or near modern major paved trans-desert highways receive most attention from archaeologists which, of course, skews any statistical evidence we might have for analysis of ancient historical trends in the Eastern Desert as a whole. Farther afield in the more remote regions small mobile teams of scholars engage in surveys. These seek to locate ancient sites and roads over a broad area and are best described as ‘site extensive’ surveys. These provide a good general overview of what remains exist, their appearances, locations, and their approximate dates and functions. Those expeditions that concentrate on drawing detailed plans of ancient sites, either because nothing more can be done due to time, money, or the impending destruction of the site as the result of modern mining, quarrying, or other development plans, engage in what we term ‘site intensive’ surveying. Drawing detailed plans and architectural elevations of ancient remains during a ‘site intensive’ survey might also be a prelude to future excavations We have more to say about the different surveying methods and specific examples in Chapter 5.

Some modern anthropological work has attempted to determine the relationship between the ancient inhabitants of the Eastern Desert, like the Medjay, the Blemmyes, and the Nobadae, and those modern Bedouin now residing in the region: the Ma‘aza, the ’Ababda, and the Bisharin. We discuss these groups in some detail in Chapter 11.