Shrines, Bathtubs, and Stone Quarries

How the Stone was Quarried and Moved

Along the Desert Roads to the Nile

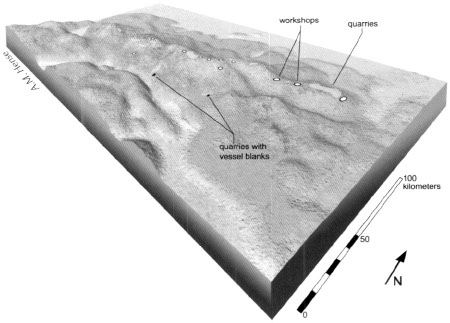

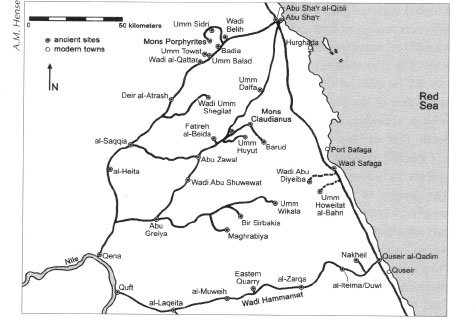

Earlier chapters referred briefly to the presence of stone quarries in the Eastern Desert (Fig. 4.1). The oldest date from the Late Predynastic period shortly before the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by Menes/Narmer in about 3000 BC. Smaller stone objects including cups, bowls, and cosmetic palettes seem to have been the main products deriving from the quarries at this early date. Graffiti and inscriptions found in long-abandoned stone workings attest the activities of quarrymen and masons from Early Dynastic times approximately five thousand years ago.

While we cannot examine all the quarries that were exploited during the millennia of our interest in the Eastern Desert, we will discuss a number that are especially well preserved or suitably well studied. These occur especially in the Ptolemaic and Roman eras. We can, by looking at these, provide some insights into the great effort in time, money, organization, and suffering that went into finding, quarrying, and dragging the stones from these remote desert lairs to the Nile.

In the pharaonic period, anyway, the ultimate destinations of these stones were the temples and other structures erected for the deities and to the glory of the god-kings along or near the Nile. In later Roman times, however, most of the stone deriving from Eastern Desert quarries was built into huge imperial structures well beyond Egypt's shores. We can only stand in awe of a civilization that was capable of conducting such huge quarrying endeavors in remote desert regions and successfully hauling the stones, which were often giant monoliths, to destinations sometimes thousands of kilometers away in the far reaches of the Roman Empire.

Fig. 4.1: Map of the Eastern Desert showing important stone quarries.

Stone Quarries in the Late Predynastic to Late Pharaonic/Late Dynastic Periods

A University of Toledo survey recently discovered a diorite quarry dating to the Late Predynastic period at Gebel Umm Naqqat. The quarry, lying seventy kilometers southwest of Quseir, consists of two sloping, discontinuous, trench-like excavations. Since no tool marks or other indications appear on the quarry walls showing what methods were used to extract the two varieties of pegmatitic diorite, quarrymen likely exploited the natural fractures within the rock. Through a combination of pounding and levering they were probably able to dislodge blocks between fractures. Given the close fracture spacing, however, the largest blocks obtainable would have been less than one meter across.

The Toledo survey found only one manufactured stone tool, a twentyseven-centimeter-long pounder that had been crudely notched at one end to take a wooden handle. Instead of using manufactured stone tools to quarry the diorite, workers likely used large, heavy, natural well-rounded cobbles made of the local gabbro. Once loosened, the blocks of diorite were shaped into vessel blanks with the aid of smaller pounders. These vessel blanks were the ultimate product of the quarry. In addition to the quarry, other discoveries at Gebel Umm Naqqat included seven stone rings forming remains of a Late Predynastic cemetery, and an early Roman settlement, consisting of eleven well-preserved stone huts.

Nearby, west of the quarry at Gebel Umm Naqqat, is Wadi Sutra and this is the likely route by which the quarried diorite was taken away. This wadi runs northwest and joins Wadi Miya ten kilometers from the quarry. From there it leads to the Nile Valley.

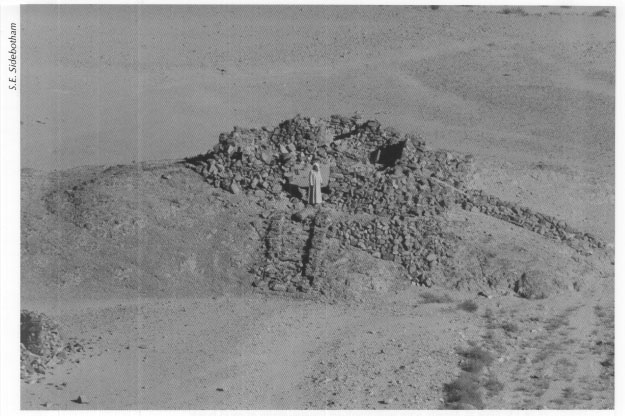

In the Early Dynastic period volcanic tuff and tuffaceous limestone were quarried at Gebel Manzal al-Seyl in the central Eastern Desert (Pl.4.1). Like the diorite at Gebel Umm Naqqat, this material was used for the production of stone vessels, mainly for funerary purposes, which reached the level of mass production in this period.

From the Predynastic period onward extensive mining and quarrying activities took place in or near Wadi Hammamat (Valley of Baths), one of the dry canyons in the rugged mountains of the Eastern Desert (Fig. 4.2). Wadi Hammamat, which led to a major source of gold exploited at Bir Umm Fawakhir, lies about halfway between Quseir on the Red Sea and Quft (ancient Coptos) on the Nile and constitutes the shortest and one of the most important routes across the Eastern Desert. Within Wadi Hammamat itself are quarries for both the so-called breccia verde antica, a variegated green stone, and for the famous bekhen stone, known to geologists as a type of graywacke that does not occur anywhere else in Egypt, and which was highly prized by the ancient Egyptians. The breccia verde antica was used mainly for royal sarcophagi in late New Kingdom to Late Period pharaonic times (thirteenth to fourth centuries BC) while in the Roman era it was shaped into columns, basins, and wall and floor inlays.

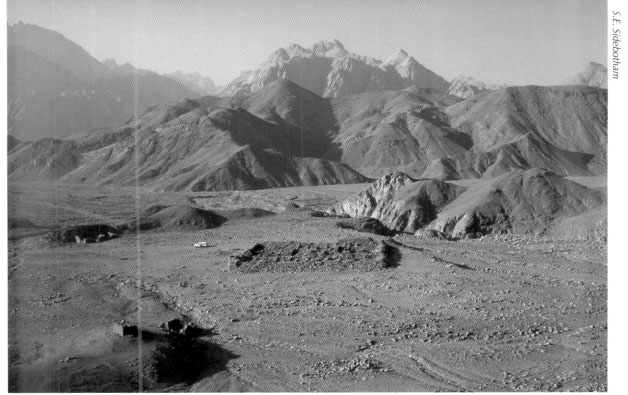

Fig. 4.2: Wadi Hammamat (Valley of Baths), one of the dry canyons in the rugged mountains of the Eastern Desert.

The most striking reference to Wadi Hammamat is the so-called Turin Mining Papyrus, an ancient vividly colored map drawn on a scroll of papyrus during the reign of Ramesses IV (1163-1156 BC) of the Twentieth Dynasty (Fig. 4.3). The map came from a private tomb in the ancient village of Deir al-Medina near Luxor and is now housed in a museum in the northern Italian city of Torino. It was discovered between 1814 and 1821 by agents of Bernardino Drovetti, the French consul general in Egypt. It is the earliest surviving topographical map known from ancient Egypt and one of the earliest maps in the world with real geological content as it incorporates color-coded geological zones.

Fig. 4.3: The Turin Mining Papyrus.

The map illustrates a region of wadis and hills along with the locations of some mines and quarries, three roads, and some trees in the main wadi. Written on it are numerous short texts in hieratic script. On the largest and best preserved fragment of the papyrus are several cultural features, including a commemorative stela from the time of Seti I (1306-1290 BC) of the Nineteenth Dynasty, a cistern (or ‘water-reservoir’), four houses forming a gold working settlement, a shrine dedicated to ‘Amun of the pure mountain,’ and a well. The main wadi is marked by colored spots, while the hills are shown as stylized conical forms with wavy flanks laid out flat on both sides of the wadi.

Although there has been some debate about which region the map represents (some scholars assert that portions of the auriferous regions of Wadi ‘Allaqi, southeast of Aswan, are depicted), it is likely that it records a fifteen kilometer stretch of Wadi Hammamat. Located here were, as we have already noted, the ancient gold-working settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir and the famous bekhen stone quarry, to which Ramesses IV alone sent at least three major quarrying expeditions, one involving no fewer than 8,362 men! The top of the map is oriented toward the south with west on the right side and east to the left. There is no constant scale, but by comparison with the actual distances in Wadi Hammamat it is evident that the scale varies between fifty and one hundred meters for each one centimeter on the map.

The papyrus map was probably drawn as an aid to or a record of Ramesses IV‘s bekhen stone quarrying expedition to Wadi Hammamat late in the third year of his reign. The author of the map might be Amenakhte, son of Ipuy, ‘Scribe of the tomb,’ who worked as the chief administrative officer in the village of Deir al-Medina, where builders of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings lived.

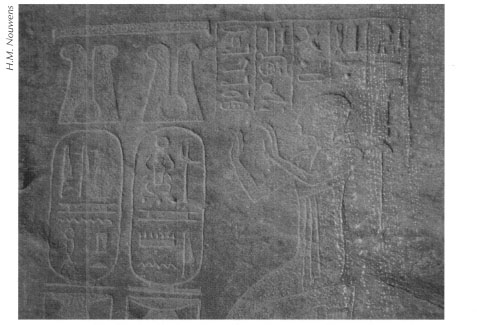

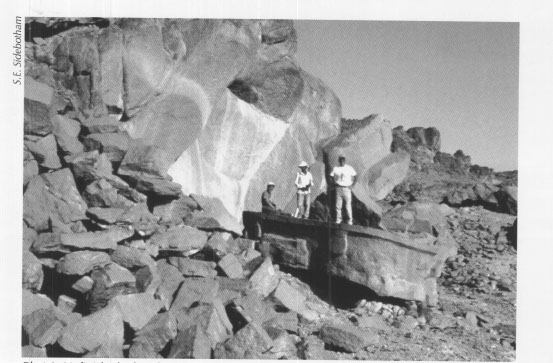

Rock faces surrounding the quarries at Wadi Hammamat as well as east and west of the quarries are covered with prehistoric petroglyphs depicting animals and hunters and more than four hundred inscriptions, which date from the Old Kingdom to the end of the Roman period (Figs.4.4-4.5). The hieroglyphic and hieratic inscriptions record the activities of expeditions sent to obtain the precious stone from this area. On the north side of the wadi, remains of ancient quarrying activity include debris and a split, abandoned stone sarcophagus halfway up the cliff face.

Fig.4.4: Petroglyphs in Wadi Hammamat, depicting animals and hunters.

Fig. 4.5: Hieroglyphic inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat.

The inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat typically include a dedication to the Coptos divine triad of Isis, Horus, and Harpocrates or to Min, the ithyphallic fertility god who served as the protector of mining areas in the Eastern Desert. Min, who was already worshiped in the late Predynastic period, was first associated with Coptos and later with Akhmim, known as Panopolis in the Ptolemaic period, because of the Greeks’ association of Min with the god Pan. Surmounting some of the inscriptions is an offering scene or an image of the god(s) mentioned above.

Furthermore, most of the inscriptions, which are historical records of royal activities, provide the name of the expedition leader and his titles, as well as the name of the pharaoh who ordered the quarrying activities. In other cases details of the expeditions are given, such as the labor force employed or the number of blocks quarried. It is from these reports of special achievements or events that we learn about the workings of the expeditions in the Wadi Hammamat. These include the methods used for quarrying, and the problems the quarrymen encountered in finding, selecting, and transporting the required material.

Although the first hieroglyphic inscriptions recording quarrying expeditions date to the great pyramid builders of the Old Kingdom (2649-2152 BC), the Middle Kingdom inscriptions (2040-1640 BC) are among the fullest and most informative. Especially noteworthy are the lengthy accounts of pharaoh Mentuhotep IV of the Eleventh Dynasty; they report his dispatch of ten thousand men and ample provisions for them to bring back some suitable stone to use for the king's sarcophagus and lid. According to the texts no fewer than two miracles happened during this expedition. A fleeing gazelle gave birth on the very block that was chosen for the king, and a rare flash flood revealed a well of clean water, all-important in this hyper-arid region. Another Middle Kingdom inscription, carved during the reign of Senwosret I (1971-1926 BC), tells of seventeen thousand men sent to obtain stone for sixty sphinxes and 150 statues, while an inscription, dating to the reign of Amenemhat III (1844-1797 BC), vividly illustrates the technical difficulties encountered in fulfilling the king's orders to secure certain materials.

The New Kingdom pharaohs (1550-1070 BC) are poorly attested in Wadi Hammamat before the Ramesside period; those few inscriptions provide little more than some royal names. The last hieroglyphic inscriptions date to the reign of Nectanebo II (360-343 BC) of the Thirtieth Dynasty. Thereafter, the record continues in a nearby shrine to Pan where there are demotic and Greek texts, dating to the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

The history of the Wadi Hammamat extends much further back than pharaonic times. Artifacts from the Badarian period (about 5500-about 4000 BC) and numerous Predynastic petroglyphs (rock carvings), found immediately northeast of the bekhen stone quarries, attest its early importance.

From before the era of writing, humans scratched depictions of animals and themselves on rock faces throughout the Eastern Desert. In the prehistoric era, in addition to representations of gazelles, long-horned cattle, giraffes, elephants, ostriches, and other animals, the artists who produced these images also carved sickle-shaped boats, animal traps, and human hunters. This art may represent game that they stalked for food or may embody more magical or religious meanings; we simply do not know. The richness of wildlife, however, is a strong indication that the Eastern Desert was more abundantly watered in late prehistory than it is today. The style in which these carvings were made, by comparison to designs painted on pottery, allows us to date them to sometime before the late fourth millennium BC.

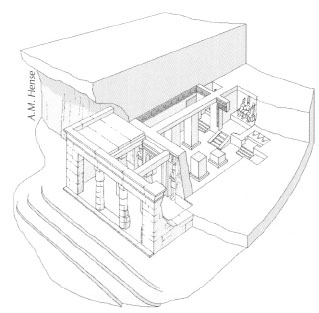

An excellent example of a late pharaonic (Thirtieth Dynasty) quarry was only recently discovered at Rod al-Gamra (Fig. 4.6). The dolerite porphyry stone pried from the desert terrain there using iron tools was employed to produce naoi. These were stone boxes in which relatively small cult statues might be placed. Five of the naoi quarried there remain on the site, abandoned for reasons we can only imagine. Rod al-Gamra lies not far south of the ancient route linking Berenike on the Red Sea to the Nile at Edfu (ancient Apollonopolis Magna), a road used extensively between the third century BC and early Roman times and one we will discuss in a later chapter. Yet, there is little or no indication that the people traversing this highway during those later times knew of the quarry.

Arthur Edward Pearce Brome Weigall was born in November 1880. He left Oxford to join the Egypt Exploration Society Fund as an assistant to Sir Flinders Petrie. Between 1905 and 1914 he was the Egyptian Government's Inspector General of Upper Egypt, Department of Antiquities. After he left Egypt in 1914 he became a designer for London theaters and a film critic for the Daily Mail. He wrote about Howard Carter's excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb for that newspaper in 1922 and 1923. He published extensively in several genres (novels and history) and on a variety of topics: Greek and Roman history, modern Egyptian history, the history of ancient Egypt, and Egyptian archaeology. Of his prolific publications on ancient Egypt the most relevant for our purposes is Travels in the Upper Egyptian Deserts. He died in a London hospital in January 1934 at the age of fifty-three.

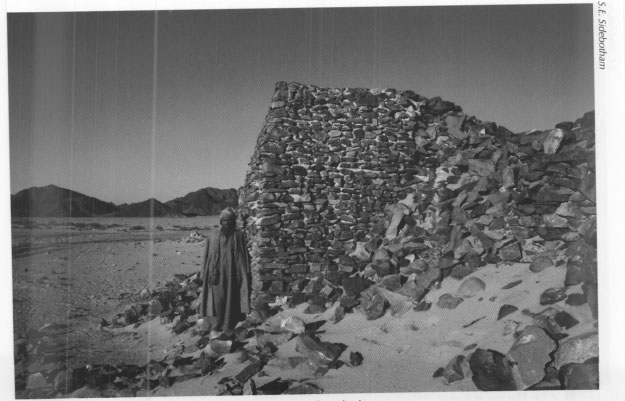

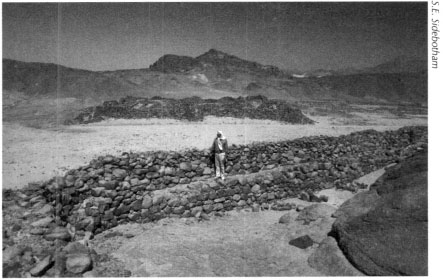

A few stone huts or buildings—made of local cobblestones stacked forming walls built with little or no use of mortar or binding—that might have accommodated workers or administrative officials survive, so we can only hypothesize that activities at Rod al-Gamra were not conducted over extended periods. Perhaps only a few dozen people ever labored here at any one time and they may well have lived in tents. The sizes of the naoi preserved on the site are not substantial; the largest is less than 1.5 meters long by 82 centimeters wide by 80 centimeters deep, so their conveyance to the Nile would not have been overly difficult. We assume they were hauled there on small wagons pulled by teams of donkeys or horses. Examples of these naoi can still be seen at Egyptian religious sites and in museums in Europe; a fine specimen, which dates to the Thirtieth Dynasty, complete with a small cult statue inside, may be viewed in the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna, though we cannot be certain that this particular example came from Rod al-Gamra,

Stone Quarries in the Roman Period

The best-known and largest quarries in the Eastern Desert are, however, Roman in date and the extent of the work and the logistical complexities entailed in their ongoing operation dwarf anything that preceded them. Most Roman quarrying operations sought the various beautiful hard stones, mainly granites, diorites, porphyries, and others, available in the Red Sea Mountains that form the watershed between the Nile and the Red Sea. There was even a marble quarry, exploited in Roman times at least, located at Gebel Rukham just north of the modern highway joining Marsa ‘Alam on the Red Sea with Edfu on the Nile. Some ‘soft’ stones (especially limestone and sandstone) also came from the Eastern Desert, mainly nearer the Nile. There was also a very soft talc or schist (called baram in Arabic) quarried and used locally in the Eastern Desert in a number of locations at various times; small bowls, beads, jewelry including bangles, and children's toys were the main products.

There are many facilities surviving from the Roman era that allow us to reconstruct how the quarrymen accessed the stone, removed it from high peaks to wadi floors below, and then transported it to the Nile. First they chiseled wedge holes along the line between the block they sought to extract from the quarry and the bedrock in which it lay. They then inserted metal wedges which they continued to hammer, thereby cracking the rock. The block could be further worked into the rough shape desired before being shipped to the Nile. No stones were ever carved and worked to their final finished appearance in the quarries for by doing so the item stood a good chance of being damaged during transport to its final destination. Thus, a thin protective ‘coating’ of stone was left on each product, which would be removed, and the final desired appearance achieved only at the point of destination.

There is evidence in at least one quarry, in Wadi Umm Shegilat, which lies south of Mons Porphyrites and northwest of Mons Claudianus, that the Romans occasionally sawed the stones to desired proportions after they were removed from the quarry and prior to shipment to the Nile.

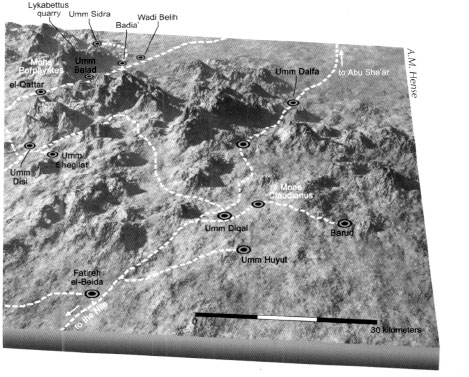

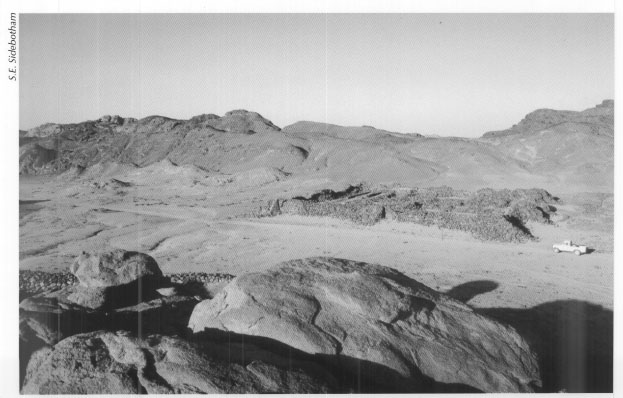

There are dozens of Roman period quarries known from the Eastern Desert, but the largest and most important ones and those that have been excavated and best-studied lie in the central portion of the region. From north to south they include the massive operations at Mons Porphyrites, those at Mons Claudianus and the ones in Wadi Umm Wikala (ancient Mons Ophiates). There were others, too, some clearly satellite operations affiliated with the larger ones especially at Mons Porphyrites and Mons Claudianus (Pl. 4.2) and we will briefly look at those as well.

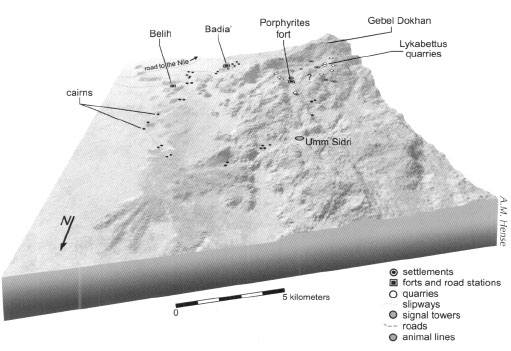

The expansive quarrying operations at Mons Porphyrites, in and around Gebel Abu Dukhan (Mountain of Smoke/Smoky Mountain) lay northwest of the modern Red Sea city of Hurghada. The site was first rediscovered by James Burton in 1822, but aside from a brief article he wrote for a British newspaper the following year it was really the intrepid and indefatigable J.G. Wilkinson who presented a paper on his and Burton's findings in 1830 and then published the first lengthy account of the site in 1832. A number of European and American visitors followed as well as many published reports of their journeys. Between 1994 and 1998 a British team undertook a detailed study that included surveying and mapping the remains and excavating portions of the site. Theirs is the fullest record we have of the ancient settlements and quarries at Mons Porphyrites.

The quarrying operations at Mons Porphyrites seem to have been confined to the Roman period, from the first into the fifth centuries AD. Study of the pottery, coins, ostraca, papyri, and inscriptions found at Mons Porphyrites does not indicate any earlier exploitation of the site, though in the 1920s the British surveyor and cartographer G.W Murray noted some evidence for an Early Dynastic presence in this region. Early Christian hermits seem to have lived in the area during the latest phases of quarry activity and also, apparently, after the quarries were abandoned. They had a cemetery near some of the ruins, which has preserved tombstones inscribed in Greek from their time. There were, however, no Islamic quarrying endeavors at Mons Porphyrites. Briefly between the 1880s and 1990s there were various projects that sought to obtain the much coveted ‘imperial’ purple porphyry of Mons Porphyrites, but none was large nor, ultimately, successful in the long run.

The quarries at Mons Porphyrites (Pl. 4.3) are scattered over a large area and there were several settlements built to accommodate the workers and administrators responsible for operations. As with all human activities in the desert, the primary concern was the acquisition, storage, and distribution of adequate supplies of water and food. The large and impressive remains of hydraulic installations throughout the quarry and residential areas indicate that most if not all water was obtained from digging wells in surrounding wadi floors. Water from the wells was then channeled into storage facilities or flowed into troughs for consumption by the numerous draft animals required to haul supplies to and stone from the site to the Nile Valley. Water from one such well north and below the main fort (praesidium) in Wadi Ma‘mal was probably laboriously transported by porters in leather bags or amphoras up the hill and poured into a large cistern (known as a lakkos in Greek or laccus in Latin) inside the Roman praesidium, which was the largest building at Mons Porphyrites. Nearby were a small bath and several temples. One settlement in the quarries has the remnants of a broken tub or sarcophagus made of purple porphyry (Pl. 4.4) while British archaeologists found a spectacular Roman-era inscription written in Greek at another quarry village. This engraved stone, which depicts an image of the Egyptian god Min/Greek deity Pan, records on July 23, AD 18 (early in the reign of the emperor Tiberius) that Gaius Cominius Leugas discovered Mons Porphyrites and the various types of stone it provided. It goes on to state that he dedicated a sanctuary to (the gods) Pan and Serapis for the well-being of his children. The Greek deity Pan was associated with the pharaonic ithyphallic fertility god Min, who served as a protector of mining areas in the Eastern Desert and was also guardian of desert travelers. Serapis was a hybrid of the Egyptian god Osiris and the Apis Bull, with the attributes of a number of other Hellenistic deities.

George William Murray was a Scotsman born in 1885. He was educated at Westminster School and joined the Survey of Egypt in 1907 where he served as political officer for the northern Red Sea region during the First World War. He was appointed Director of Desert Surveys in 1932. An avid mountaineer, he worked for the Survey of Egypt for forty-five years drawing maps of Sinai and the Eastern and Western Deserts. His breadth of knowledge of the land and the people of the Eastern Desert is unsurpassed. He also exhibited great curiosity about the ancient remains and reported these in a number of articles and in his book Dare Me to the Desert. Murray died in Aberdeen, Scotland in 1966 and was survived by his wife Edith.

Fig. 4.6: The late pharaonic (Thirtieth Dynasty) quarry at Rod al-Gamra.

The most sought after stone from Mons Porphyrites was the ‘imperial’ purple porphyry used in structures such as columns, sculpture, and sarcophagi, especially those of the Roman emperors and their families. Spectacular examples survive. The famous statue of the Tetrarchs, four Roman emperors who ruled jointly between AD 293 and 305, built into one corner of the Basilica San Marco in Venice is carved from the purple porphyry of Mons Porphyrites. The impressive and intricately carved and highly polished sarcophagi of Helena, the mother of the emperor Constantine the Great (AD 306-337) and of his daughter Constantia, now in the Vatican Museum in Rome, are perhaps the finest examples of sculpted art from the Mons Porphyrites quarries. Black porphyry was also sought. These stones, especially the purple variety, were in demand long after quarrying operations ceased. Although work at Mons Porphyrites came to a halt in the fifth century AD, ‘imperial’ purple porphyry columns, clearly recycled from other earlier structures, appear in the church of Hagia Sophia built in the early sixth century by Justinian I (AD 527-565) at Constantinople.

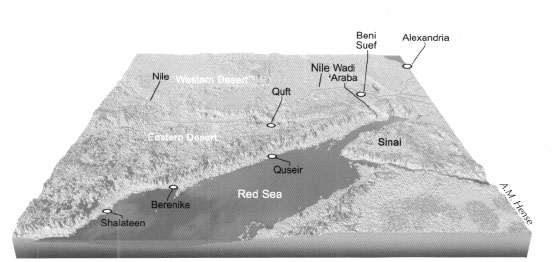

Pl. 2.1: Map of Egypt, the Eastern Desert, and the northern end of the Red Sea.

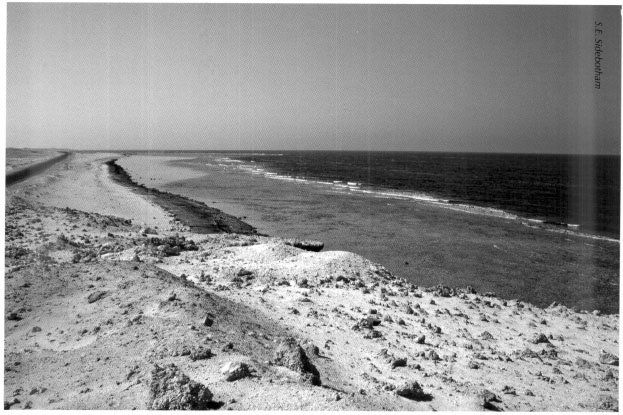

Pl. 2.2: View of Egypt's Red Sea coast.

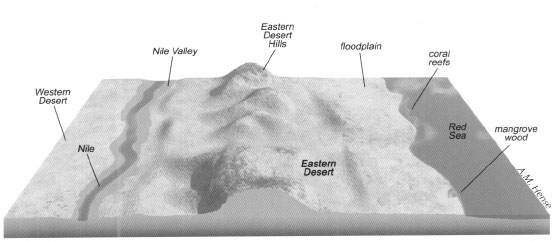

Pl. 2.3: Cross-section of the Nile Valley and the Red Sea area.

Pl. 2.4: The multi-hued red-and-black granite mountains in the Eastern Desert that form the watershed between the Red Sea and the Nile.

Pl. 3.1: The Via Nova Hadriana near Antinoopolis.

Pl. 3.2: Remains at Makhareg, about forty kilometers east of Antinoopolis, comprising a few buildings and a large well.

Pl. 3.3: The early Roman fort in Wadi Safaga, about fifteen kilometers southwest of Safaga.

Pl. 3.4: Reconstruction of Gebel Zeit, located about fifty kilometers south of the modern Red Sea town of Ras Gharib.

Pl. 4.1: Manzal al-Seyl in the central Eastern Desert where in the Early Dynastic period volcanic tuff and tuffaceous limestone were quarried.

Pl. 4.2: The area of Mons Claudianus and Mons Porphyrites.

Pl. 4.3: The quarries at Mons Porphyrites.

Pl. 4.4: Mons Porphyrites bathtub or sarcophagus in Northwest Village.

Pl. 4.5: Ramp of 1,700 meters length connecting the Lykabettus quarries at Mons Porphyrites to the wadi floor below.

Pl. 4.6: The Serapis temple at Mons Porphyrites.

Pl. 4.7: The well-preserved praesidium at Umm Balad (ancient Domitiane/Kaine Latomia).

Pl. 4.8: The quarry complex at Mons Claudianus.

Pl. 4.9: Unfinished tub or basin in quarry at Mons Claudianus

Pl. 4.10: The large fort at Mons Claudianus.

Pl. 4.11: Small fort and tower near Mons Claudianus.

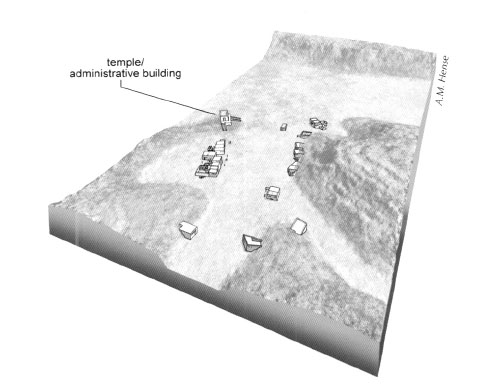

Pl. 4.12: Quarry settlement at Umm Huyut.

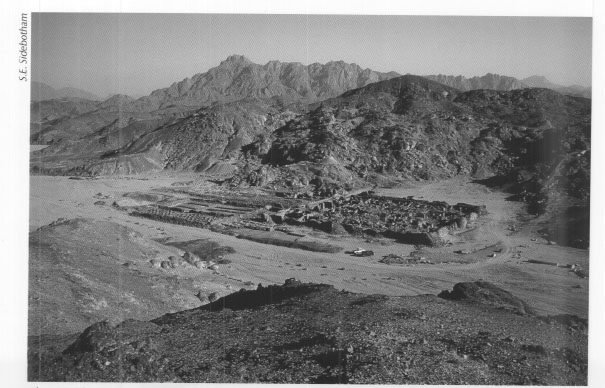

Pl. 4.13: Possible shrine or administrative building at Umm Huyut.

Pl. 4.14: The fort at Badia’

Pl. 4.15: Deir al-Atrash: gate with flanking towers made of mud brick.

Pl. 4.16: Deir al-Atrash: corner tower made of stacked stone.

Pl. 4.17: The lower fort at al-Heita with mud-brick superstructure, including nice examples of round towers flanking the main south-facing gate. Unfinished hill top fort center and above.

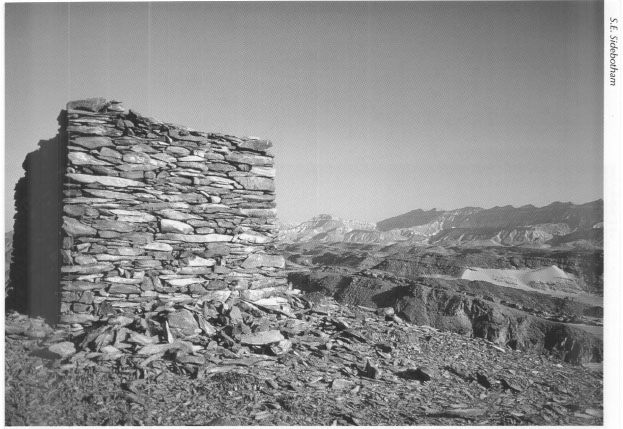

Pl. 4.18: Signal tower on the Quseir-Nile road.

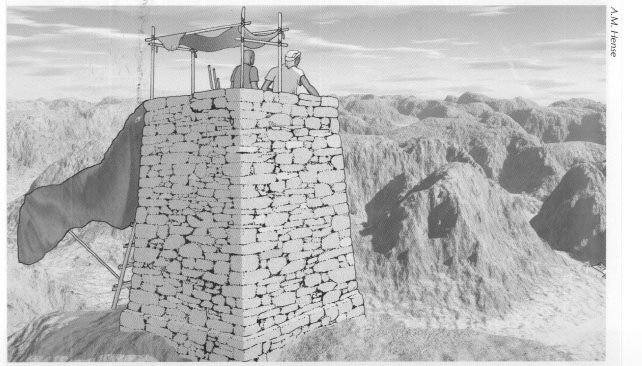

Pl. 4.19: Reconstruction of signal tower on the Quseir-Nile road.

Pl. 4.20: Praesidium at al-Zarqa (ancient Maximianon).

Pl. 4.21: Interior stairway in the praesidium at al-Zarqa (ancient Maximianon).

Pl. 6.1: The temple at al-Kanaïs, built by Seti I of the Nineteenth Dynasty.

Pl. 6.2: Drawing of the temple at al-Kanats

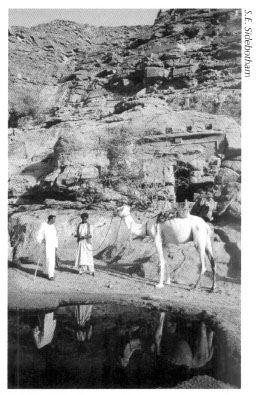

Pl. 6.3: Bedouin guides in front of the Ptolemaic-era temple at Sir Abu Safa.

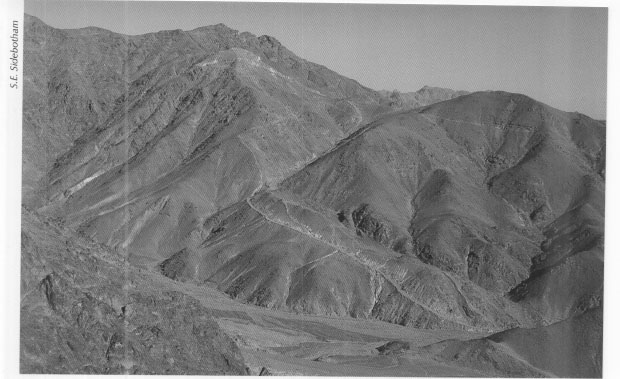

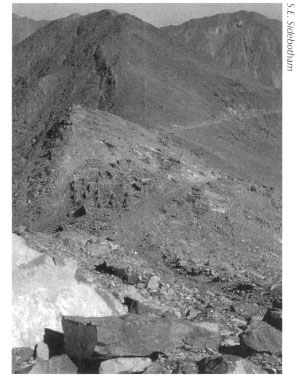

Once the stone was actually cut free from the basement rock in which it had lain and had been shaped, it had to be removed, often from quarries near the peaks of mountains. To move the stone artificial ramps—often of impressive dimensions—were constructed that wound down the sides of mountains. In the Mons Porphyrites complex, for example, the stone was laboriously, yet carefully dragged, we assume manhandled on wooden sledges and slowly lowered using a series of ropes and pulleys operated by quarrymen themselves or using horses or donkeys. Several of these slipways survive in excellent states of preservation, especially the lengthy one connecting the so-called Lykabettus quarries at Mons Porphyrites (Fig. 4.7) to the wadi floor below which was over 1,700 meters long (Pl. 4.5). Ramps like this one reveal the great expenditure of effort and the incredible infrastructure needed to remove the stone. Numerous footpaths along which workmen moved between quarries and settlements appear in a spider web-like manner throughout the region.

Fig 4.7: Part of Lykabettus quarry, village, and ramp at Mons Porphyrites.

Leading from the quarries at Mons Porphyrites was a road and elaborate infrastructure to ensure the successful conveyance of the stones to the Nile Valley. One way station at Umm Sidri near the quarries preserves animal tethering lines and hydraulic facilities designed to handle the hordes of pack and draft animals moving the stone out of the quarry on its long journey to the Nile. Another nearby site has a massive loading platform. Clearly stones were dragged up a ramp leading to the top of the platform from which they were wrestled into the beds of awaiting wagons that would then haul them to the Nile. All quarry facilities were built of local cobblestones and small boulders stacked to form walls. On the other hand, hydraulic installations including tanks, channels, troughs, and so on were sometimes made of kiln-fired bricks as well as local cobblestones. Whether of kiln-fired bricks or stacked stone, those features directly exposed to water were then coated with a waterproof lime plaster. These hydraulic features often survive in remarkable states of preservation.

Study of the ancient written documents from the quarry settlements and analysis of the human bones from the badly looted ancient cemeteries at Mons Porphyrites clearly identify men, women, and children who lived and died there. They appear to have been free labor, toiling at the quarry of their own volition, and not slaves. Wages paid to those working at Mons Porphyrites in the mid-second century AD were probably similar to those earned by their counterparts at nearby quarrying operations at Mons Claudianus, which was a maximum of about forty-seven drachmas a month for a highly skilled man regardless of his profession. Apparently, top pay depended on experience more than upon the type of work performed. Forty-seven drachmas was about twice what a skilled laborer earned working in the Nile Valley, but only about half of what a Roman legionary received each month in the second century AD.

The residents of Mons Porphyrites had an abiding interest in religion; the remains of several impressive temples survive attesting their devotion. Aside from the sanctuary in one of the outlying quarry villages dedicated by Gaius Cominius Leugas to the deities Pan and Serapis that we noted above, there are, near the large fort in Wadi Ma‘mal and not far from the base of the long ramp leading to the Lykabettus quarries discussed above, temples built to Isis, Isis Myrionomos, and Serapis (Pl. 4.6). Detailed inscriptions carved in Greek on large finely wrought local stone, some still surviving on the site, indicate that these temples were erected and flourished beginning in the reigns of the Roman emperors Trajan (AD 98-117) and his successor Hadrian (AD 117-138). It was in these years that activities at Mons Porphyrites seem to have peaked.

Satellite Settlements of Mons Porphyrites

Satellite quarries of Mons Porphyrites also produced stones for export to the Nile; those at Umm Towat and Umm Balad (the ancient Domitiane, later Kaine Latomia, which means ‘New Quarry’ in Greek) are good examples. The latter quarry, which operated in the late first and second centuries AD, has a well preserved praesidium guarding it (Pl. 4.7) and was joined by an excellent example of a cleared desert road linking it to the main thoroughfare between Mons Porphyrites and the Nile. French archaeologists have only just undertaken work here and among their discoveries were numerous ostraca that provide the ancient name of the settlement and quarry and the dates of its operation.

The quarry complex at Mons Claudianus (Pl. 4.8) is perhaps even more spectacular than that at Mons Porphyrites. Mons Claudianus lies southsoutheast of Mons Porphyrites and the stone obtained here was hard grandiorite/tonalite gneiss. Though the quarries at Mons Claudianus appear to have operated for a shorter time than those at their more northerly neighbor, that is, from the first to third centuries AD, the sizes of the stones quarried from Mons Claudianus were, in general, substantially larger than those pried from Mons Porphyrites. They were also apparently used more frequently in gargantuan Roman imperial building projects throughout the ancient Mediterranean. For example, large monolithic columns from the quarries at Mons Claudianus decorate the front porch of the Pantheon in Rome and the Basilica of Trajan in his forum, the largest one of its kind, also in Rome. Columns made of Mons Claudianus stone can be seen in the Flavian Palace (first century AD) on the Palatine Hill and in the Baths of Caracalla (an emperor who ruled AD 211-217) at Rome. Mons Claudianus columns also appear in the emperor Hadrian's villa at Tivoli just east of Rome and at the retirement palace of the emperor Diocletian (AD 284-305) at Split on the Adriatic coast of Croatia (Fig. 4.8).

Fig. 4.8: The products of the stone quarries of Mons Porphyrites and Mons Claudianus.

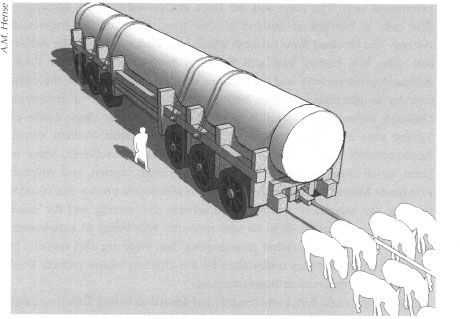

The massive dimensions and weights of some of the quarried objects found at Mons Claudianus are truly staggering. Numerous columns, tubs, and other rupestral products can still be seen now silently reclining in abandoned workings around the area. One giant monolithic column now broken and discarded in a quarry behind the main settlement measures in excess of eighteen meters long with an estimated weight of 207 tons (Fig. 4.9). A huge unfinished tub or basin 5.8 meters long by 2.98 meters wide lies derelict and unfinished in another hilltop quarry (Pl. 4.9). It must weigh dozens of tons. We assume that these monolithic monstrosities would not have been quarried in the first place if some means of transporting them to the Nile were not available. We can only imagine the size and appearance of the vehicles, and the number of draft animals and people used to haul these giant blocks across the desert to the Nile (Fig. 4.10).

Though there are several impressive Roman period settlements in the region, the main focal point for activities at Mons Claudianus was clearly the large fort (pl. 4.10 and Fig. 4.11) and associated bath, temple of Serapis, and animal tethering lines. The surprisingly well-preserved temple and its elaborate inscription lie within a stone's throw of the fort and the extramural bath. The latter was not large and probably could accommodate only a handful of bathers at one time. Parts of the hypocaust system—the elevated floor beneath which heat circulated—for the caldarium (the hot baths) can still be seen beneath the broken floor. Archaeological surveys and excavations conducted here and in the environs by an international team lead by the Institut français d'Archéologie Orientale between 1987 and 1993 produced the largest single cache of ostraca ever excavated anywhere in the ancient Greco-Roman world. Approximately 9,200 ostraca, written predominantly in Greek, some in Latin, detail many aspects of the lives of the men, women, and children who made Mons Claudianus their home. In addition to precise pay records showing top salaries of forty-seven drachmas per month, and the usual requests for various foods to be sent from the Nile Valley to supplement what must have been a rather monotonous diet, there are also remains of school practice exercises undertaken by the children whose parents lived and worked in this remote desert outpost.

Fig 4.9: Eighteen-meter-long monolithic column now broken and abandoned in a quarry behind the main settlement of Mons Claudianus.

Fig. 4.10: Reconstruction of a transport wagon with column.

Fig. 4.11: Somewhat fanciful view of the large fort at Mons Claudianus, drawn by G.A. Schweinfurth. From G. Schweinfurth, Auf unbetretenen Wegen in Aegypten (Hamburg-Berlin: Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, 1922).

Close by the main fort, bath, temple, and animal tethering lines is another concentration of buildings that includes a fine example of a large hydraulic tank. This settlement is, in turn, joined to yet another small fort with large guard tower (Pl. 4.11). A large modern water tank constructed by a unit of the New Zealand army during the Second World War near this small fort and tower attests the keen and ongoing interest in securing and protecting water in this hyper-arid region throughout history.

Fig. 4.12: Praesidium at Barud (ancient Tiberiane) that guarded a nearby quarry.

Nearby satellite quarries of Mons Claudianus boast interesting if not huge remains. One of these was at Barud, whose ancient name was Tiberiane, where there is a fine example of a praesidium with internal cisterns (lakkoi/lacci) that guarded the quarry. There is an excellent view of this structure from the nearby mountaintop southwest of the fort (Fig. 4.12). Despite the name that would seem to imply a connection with the emperor Tiberius (AD 14-37), the pottery from Tiberiane dates to the second and possibly into the third century AD suggesting that no activity took place here in the first century AD.

Another quarry, with four areas of excavation complete with skopeloi (watch or signal towers) and a nicely made stone hut, at Umm Huyut (Pl. 4.12) was also clearly a satellite operation of Mons Claudianus. Our survey only discovered this site when our Ma‘aza Bedouin friend and guide Salah ‘Ali Suwelim showed it to us in June 1993. He claims that he first found it in 1981. Only small stone products including pedestals (possibly for use as altars), small columns, and other items were obtained here and some can still be seen abandoned between the quarries and the small settlement. Comprising fourteen buildings of dry laid stone, one edifice was particularly large, prominent, and well built (Pl. 4.13). We have not been able to identify with any certainty what function this building served. It perches on a small natural rise approached by two staircases, one on the northwest and the other on the southwest, with a rectangular shaped niche at the southeastern end and benches abutting the southern and western interior walls. Clearly, it must have played an important administrative role and perhaps religious, but we found no inscription or other artifacts that provided any clue. Pottery we collected from the surface at Umm Huyut for study was early Roman (that is, first to second centuries AD) in date. The geographical and chronological proximity of Umm Huyut to Mons Claudianus and the similarity in appearance in the types of stones taken from both locations can be explained by the differences in the sizes of the products that these respective places produced. Mons Claudianus clearly provided and shipped huge stone pieces while those extracted from Umm Huyut were quite diminutive by comparison. Our survey could find no ancient road leading from Umm Huyut, but there must have been one and it undoubtedly headed west where at some point it joined up with the main road leading from Mons Claudianus toward the Nile; there must have also been one that linked it to Mons Claudianus.

Wadi Umm Wikala (Mons Ophiates)

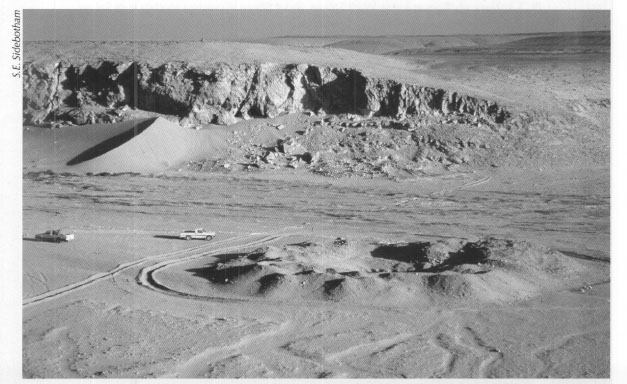

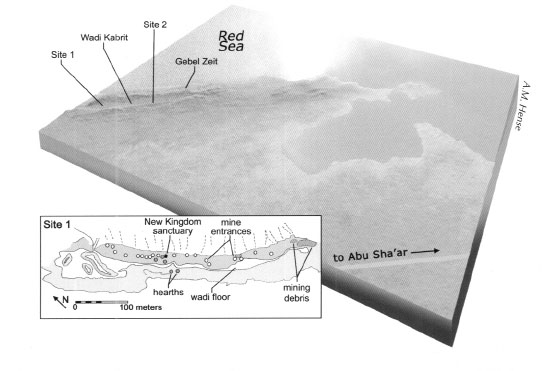

The third set of quarries that have been studied, though not in as great detail as those of Mons Porphyrites and Mons Claudianus, are those in Wadi Umm Wikala, near Wadi Semna (Fig. 4.13). These lie south-southeast of Mons Claudianus and are substantially smaller than either those or the ones at Mons Porphyrites. The ancient name for the workings here was Mons Ophiates (Snaky Mountain) and its period of operation was confined to early Roman times with the latest evidence for quarrying being possibly in the third century AD. The stone sought was gabbro, mainly from the summits or upper slopes of the surrounding mountains. The mountain peaks also have numerous cairns, skopeloi (watch/signal towers), and slipways similar in appearance to those seen at Mons Porphyrites and

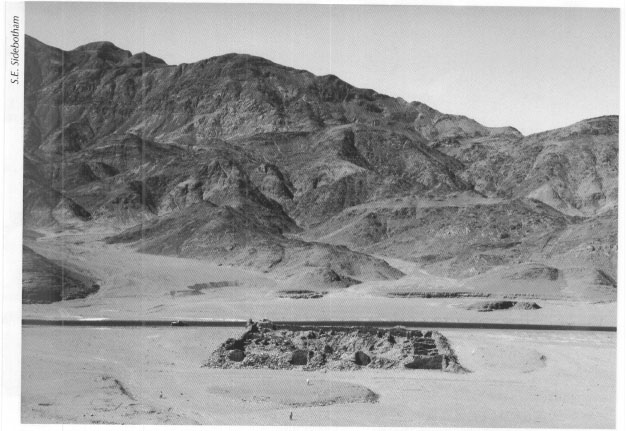

Fig. 4.13: Wadi Umm Wikala (Mons Ophiates): objects from one of the quarries in foreground and praesidium in background.

Mons Claudianus, down which the quarried stones were hauled. Our surveys between 1997 and 2000 found thirteen quarry excavations and a number of places where someone had prospected for useable stone in the early Roman period. Many of the partly finished products extracted here lay abandoned only a few dozen meters away from one of the main buildings on the site, a praesidium enclosing a cistern (lakkos/laccus). Many of the stones destined for export were small comprising, for the most part, columns, basins, pedestals, cornices, and wall and floor tiles. A few semifinished products that lie abandoned in a more remote working some distance from the praesidium are quite large, and include column bases. We found these gathered near the end of a loading platform; for some reason these pieces were never placed on wagons and hauled out of the quarry area. Yet, even the largest stones quarried from Mons Ophiates were nowhere near the dimensions of the behemoths obtained from Mons Claudianus. Their transport to the Nile probably seldom caused many problems though our survey once found some larger Mons Ophiates stones dumped along an ancient track some distance from the site suggesting, perhaps, that they had been abandoned when the vehicle carrying them had broken down. Stone from Mons Ophiates has been found in a number of Roman structures outside Egypt and was so highly valued that it was later stripped from them and recycled. Good examples of recycling appear in the Basilica of St. Lorenzo in Rome and also in the Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican where Mons Ophiates stone was used as a base for a bronze statue of St. Peter.

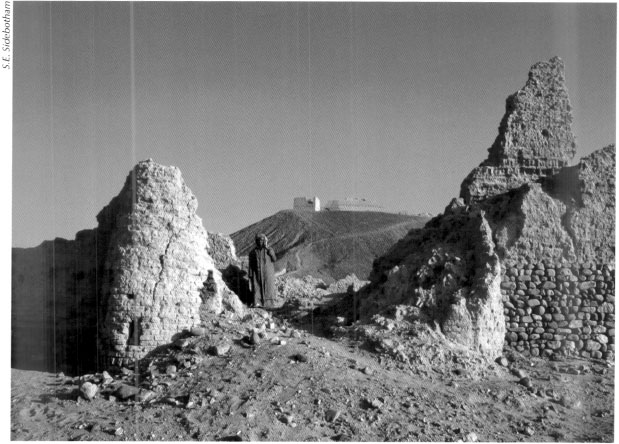

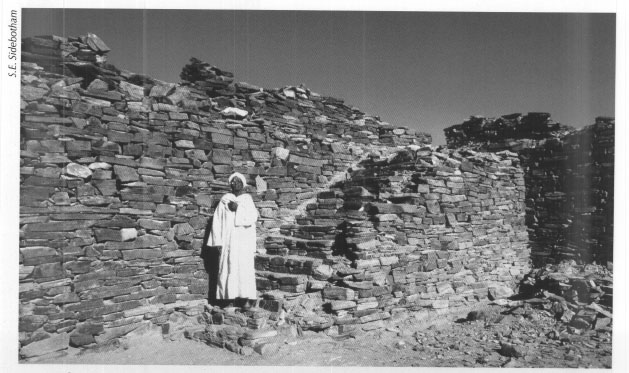

Just across the wadi from the praesidium at Mons Ophiates are the remains of a multi-roomed structure built of locally available cobblestones and boulders. A little dilapidated, but with some walls still standing to a height of 5.4 meters in one corner and preserving some windows, it was in or near this structure that F.W. Green discovered an important Roman period inscription written in Greek. He published this stone in 1909, which several later visitors and scholars have republished over the years. This important text records in the fortieth year of the emperor Augustus (May 26, AD 11 to be exact) that an official, styled archimetallarchos in Greek, named Popilius Iuventius Rufus, who was overseer of the emerald and topaz mines, pearl fisheries, and quarrying operations in the Eastern Desert, dedicated a sanctuary to (the god) Pan. The text also mentions by name the architects Mersis and Soter who designed the building. Other lesser structures lay nearby, probably the remnants of quarters for some of the personnel living and working here; heavy flooding in this part of the wadi has clearly carried away a number of these edifices; small cemeteries and individual graves, all of ancient date, lay scattered in various locations around the quarrying operations. A few kilometers away to the south near a modern railway lay the remains of another impressive fort. Though now badly destroyed, our survey was fortunate to have studied this now lost treasure before its untimely destruction by a front-end loader for reasons and by persons unknown between late August 1998 and June 1999.

Quarry Roads, Water Stops, and Forts

Though substantially closer to the Red Sea than the Nile Valley, it is clear that the stone quarried at Mons Porphyrites was, like that from Mons Claudianus and Wadi Umm Wikala and their satellite operations, transported to the Nile and not to the Red Sea. All indications from detailed study of the roads joining the quarries to the Nile and the Red Sea show this (Fig. 4.14).

Numerous roads of various sizes and importance crisscross this central portion of the Eastern Desert, which was clearly a busy area in the early and middle Roman periods as well as in later Roman times. The three major thoroughfares we will examine include the one leading from the fort at Abu Sha'r and its nearby satellite installation at Abu Sha'r al-Qibli and that passed by the Mons Porphyrites, Umm Balad, and Umm Towat quarries on its way to the Nile. The second led from the Mons Claudianus area west-southwestward to the Nile. At Abu Zawal this route bifurcated with a more northerly route sharing the one from Mons Porphyrites from the station at al-Saqqia onward to the Nile. The more southerly one passed by the major Roman watering point with extensive animal tethering lines in Wadi Abu Shuwehat, then via the large stop with a pair of stations and animal tethering lines at Abu Greiya, which lies just north of the modem paved highway linking Safaga to Qena on the Nile. The third road led from Quseir and Quseir al-Qadim (ancient Red Sea port of Myos Hormos) to Quft (Coptos) on the Nile via the Wadi Hammamat and the Mons Basanites quarries.

Fig. 4.14: Map of quarry road network.

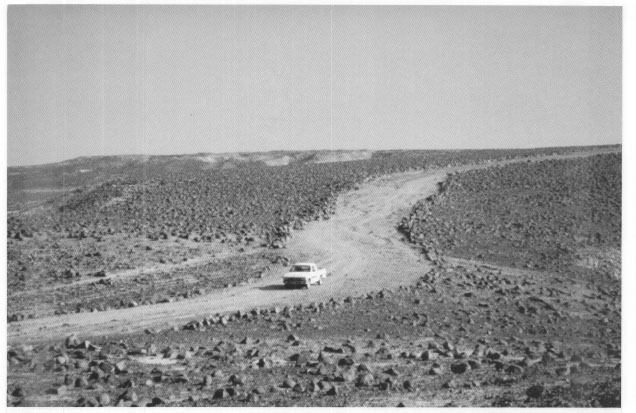

As we noted in Chapter 3, the Via Nova Hadriana was merely a smoothed track and such, too, was the case with the other ancient Eastern Desert highways in the Roman era. Those few areas that preserve paving made of small boulders and cobblestones appear in very sandy areas and were undoubtedly created in the early twentieth century to facilitate vehicular transport between Mons Porphyrites and the Nile. The major ancient Roman roads leading to the Nile from the quarries had dotted along their lengths water points, often praesidia with wells (hydreumata) and cisterns (lakkoi/lacci). In the Roman period the cisterns, and usually the wells, lay inside the protective walls of the praesidia. Most praesidia between Mons Porphyrites, Mons Claudianus, and the Nile also had outside their walls tethering lines and drinking troughs to accommodate the many draft and pack animals hauling supplies to and large stone products from the quarries. Some stone conveyed from Mons Porphyrites could conceivably have been hauled by pack animals, perhaps camels and donkeys, though some of the larger items would have required sledges or wheeled vehicles pulled by large teams of beasts. Virtually all those stone products conveyed from Mons Claudianus would have required massive wheeled transports to haul them to the Nile approximately 120 kilometers away. The impressions made by some of these huge wheeled contraptions can still be seen on the flat desert floor near the station at Deir al-Atrash and closer to the Nile in the Naq al-Teir plain in the region of the praesidia at al-Saqqia, al-Heita, and near the unfortified road station at Bir Salah. Our surveys in this area in 1989 and 1996 noted, measured, and photographed many of these wagon ruts (Fig. 4.15) as did earlier British visitors including George W. Murray and our late friend Leo Tregenza. The gauges of these wheeled vehicles range from as narrow as 2.13 meters to as wide as 4 meters. The latter seems to have been a wagon or cart with three sets of wheels. We might guess that the narrow gauges represent vehicles bearing the generally smaller stones from Mons Porphyrites while the larger sets reflect the substantially huge and heavy stone cargoes transported from Mons Claudianus. Both quarries used the road from the station at al-Saqqia onward to the Nile, but we will never be certain which tracks came from which quarry.

Fig. 4.15: Roman wagon ruts on the Abu Sha‘r-Nile road.

The crews traveling between Mons Claudianus and the Nile also had another route option available to them that ran farther south via several watering points including those in Wadi Abu Shuwehat and Abu Greiya, before arriving, like its more northerly counterpart, at the Nile city of Kainepolis (modern Qena). Abu Greiya is especially impressive as there are two praesidia, one of which is partly covered by the modern paved highway linking Safaga on the Red Sea to Qena on the Nile about forty-one or forty-two kilometers away. Between the two forts are the remains of large and well-preserved animal tethering lines. J.G. Wilkinson was the first to draw a sketch plan of this site and our survey drew a detailed measured one in summer 1998.

Sections of these roads have route-marking cairns, though not as numerous as those found on the Via Nova Hadriana. There are also signal towers, which are especially numerous and well preserved on the Quseir-Quft road. On the other two highways, however, signal and watchtowers are not frequent and tend to appear in the more mountainous areas through which the roads pass. A few cleared sections, as on the Via Nova Hadriana, and portions preserving the ruts of Roman wagons (as noted above) also survive. The two northerly roads also have watering and resting points for the draft, pack animals, and crews. The ones on the Mons Porphyrites-Nile road are the most numerous and best preserved. Some of these praesidia were so well located and important that they were repaired in the twentieth century for continued use. Surprisingly, no animal tethering lines exist on the Quseir-Nile road to support quarrying operations in the Roman period in Wadi Hammamat/Mons Basanites. We do not know why this was the case.

Good examples of these Roman rest stops, especially those that are large and fortified and have extensive animal tethering lines on the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites-Kainepolis road, include those at Badia’ near Mons Porphyrites, Umm Balad that protected a small satellite quarry, Deir al-Atrash (Monastery of the Deaf One), al-Saqqia, and al-Heita. These clearly accommodated traffic coming from the quarries of Mons Porphyrites and its environs and some-those at al-Saqqia, al-Heita, and one other-also serviced traffic from Mons Claudianus. A smaller fort at Wadi Belih is too far from Mons Porphyrites to have been associated with operations there, but it is also too early to have been affiliated with the late Roman activities on the Red Sea coast at Abu Sha'r. Its function remains a tantalizing mystery. Likely the fort at Wadi Belih was a stop on the road leading from the Red Sea coast at Abu Sha'r al-Qibli to the Nile in the period during the initial use of the Via Nova Hadriana in the early second century AD.

It is clear that some of these installations, like that at Deir al-Atrash, had wells inside their protective walls while others depended on extramural sources of water, which were then conveyed and stored inside the adjacent forts, like those at Badia’ and Umm Balad. What all these praesidia had in common, however, was extensive animal tethering lines that, together with the forts themselves, were built of locally available cobblestones and small boulders. The animal tethering lines often lie some distance from the water troughs; it is clear that the strategy was to water the animals and move them quickly away from the troughs to the tethering lines so that they would not foul the water and so that they could rest and eat elsewhere. In this manner large numbers of animals could be quickly circulated into the watering area and just as rapidly moved away to allow the next batch to be watered, as we discuss further in Chapter 13. Such facilities are found only between the quarries and the Nile; none appear between the quarries and the Red Sea. This clearly demonstrates, despite the greater distances, that the stones from the quarries were transported to the Nile and not to the Red Seaports.

Badia’ was unusual; near the fort (Pl. 4.14) and animal lines lies a huge rock outcrop which has a large, thick oval shaped fortification wall around it, again, made of locally obtained small boulders and cobbles (Fig. 4.16). The reason for this strange feature in such close proximity to the nearby praesidium remains a mystery.

The small fort protecting the quarries at Umm Balad (ancient Domitiane/Kaine Latomia) is exceptionally well preserved with an intramural cistern and an ancient trash dump in front of its gate; this was only recently excavated by a French team. Deir al-Atrash, about halfway along the road between the Red Sea and the Nile, preserves fine examples of extramural animal tethering lines and associated water troughs as well as channels that piped water from the intramural well to those exterior troughs. Remains of a large well lined with stones and part of a barrel-vaulted building made of mud brick grace the interior of the fort. The stones lining the well may have been a feature common to many of the large hydreumata in the desert though few of these linings remain visible. Such stone linings would have facilitated deeper well excavation and would have minimized their collapse and the resultant pollution of the water. There is also a large tower made of mud brick near the well. This enigmatic structure, which has only one parallel in the Eastern Desert that we have ever seen (at al-Heita, discussed below), may have contained a device known as a shaduf used to lift water from the well to the internal channels that then conveyed it to exterior troughs for consumption by the draft animals. The front gate of Deir al-Atrash preserves an exquisite example of mud-brick architecture as one of the two square towers protecting that entrance stands to a height of about 2.5 meters (Pl. 4.15) while an excellent example of a tapering stone tower at the southwestern corner of this fort has recently, unfortunately, been destroyed by vandals (Pl. 4.16).

Fig. 4.16: Rock outcrop surrounded by an oval wall, near the fortification at Badia’.

Although the fort at al-Saqqia is small, it was clearly important as the find of painted wall plaster from inside one of the rooms suggests. It may have accommodated an important administrative official in charge of water distribution to the numerous convoys that passed by. It was near al-Saqqia that the roads from both Mons Claudianus and Mons Porphyrites met and it is, thus, no surprise that the watering and animal tethering facilities here are quite sizeable.

The penultimate installation on the Mons Porphyrites road before reaching the Nile was that at al-Heita (which means ‘the wall’ in Arabic). There are badly looted animal tethering lines and at least one animal-watering trough together with a cistern, which lay south of the main entrance of the fort on lower ground. This lower fort has much of its mud-brick superstructure, built atop cobble walls, intact, including nice examples of round towers flanking the main south-facing gate (Pl. 4.17). Mud-brick edifices comprise some internal structures that were built with barrel vaulting; at one point part of the outer perimeter wall was heightened in mud brick which resulted in the blockage of an earlier stone staircase. A mud-brick tower similar in appearance to that at Deir al-Atrash survives, though no well is visible that it might have served. There is also a fort atop a hill north of the lower praesidium. This installation, built except for its foundations entirely of mud brick, some sections of which are over four meters high, appears never to have been completed. Its purpose atop the hill remains unknown. It is a rare, though not unique, example of a fort built on a hilltop in Roman times in the Eastern Desert.

The third Roman highway we will examine is that connecting Quseir and Quseir al-Qadim on the Red Sea with Quft (Coptos) on the Nile. Probably the best known and most studied of the three ancient routes we have examined, it was also the shortest of the Roman roads joining the Red Sea with the Nile. It was, thus, heavily traveled in antiquity. Certainly the quarry about midway along this road, in Wadi Hammamat, had been exploited from Predynastic times on. There were also nearby quarries at Mons Basanites, which were active in the Roman era. The eight surviving praesidia dotting the course of the highway are, in their current appearance, Roman in date. Surveys over the years have recorded their presence, appearance, and dates of construction and use, and the most recent work conducted by a French team has included excavations at several of these praesidia. They were built between Flavian times (AD 69-96) and the reigns of the emperors Trajan (AD 98-117) and Hadrian (AD 117-138). Apparently before the Flavian emperors the region was peaceful enough that only unfortified water points were needed. Translations of ostraca excavated at some of these praesidia indicate that barbarian/Bedouin attacks became frequent enough that forts had to be constructed between the late first and early second centuries AD. In addition to accommodating traffic between the quarries in Wadi Hammamat and the Nile, these forts also assisted civilian commercial caravans bearing merchandise arriving from India and southern Arabia at the Red Sea emporium of Myos Hormos. Ostraca from these desert praesidia indicate that one of the functions of the garrisons was to escort these caravans.

The ostraca also show that the majority of the troops garrisoning these forts were Egyptian. Most written communications, including official orders, however, were conveyed in Greek with very little Latin being used. Some of these forts continued in late Roman times to provide logistical support to the gold mining operations at Bir Umm Fawakhir in the fifth and sixth centuries AD. Later, Muslim hajj traffic between the Nile and Quseir also made use of some of these forts as the presence of a small mosque inside one of the praesidia (that at Bir Hammamat) indicates.

Between the various praesidia on the Quseir-Nile road were approximately sixty-five to seventy skopeloi. These watch/guard/signal towers (Pl. 4.18-4.19) lay in a variety of locations either on mountaintops, or part way down their slopes or on flat ground in the wadis below. They are inter-visible with each other and with the forts. Manned in rotation by groups of two or four men, presumably sent out from the nearest praesidium, signals would most often have been sent only locally and seldom along the entire length of the road between the Red Sea and the Nile. Fire signals would rarely, if ever, have been used. There was little flammable material available in the desert and flames would have been difficult to see in the daylight hours due to the of a signal tower on the bright sun, haze, and dust. In any case, there is no evidence of burning inside any of the towers. Our hypothesis is that prearranged signals were sent using reflective surfaces such as mirrors or highly polished metal plates or waving signal flags, perhaps of varying sizes, shapes, and colors.

Fig. 4.17: Cross-section of a signal tower on the Quseir-Nile road.

Three of the better-preserved praesidia on the Quseir-Nile road can still be seen at al-Iteima (also known as Duwi or Hammad), closer to the Nile at al-Zarqa (ancient Maximianon) (Pls, 4.20-4.21) and at al-Muweih (ancient Krokodile). The last two are the best known from recent French excavations which recovered numerous ostraca detailing many aspects of the lives of those who lived in these remote desert outposts. Maximianon actually boasted a small bath inside the fort. It is clear from the ostraca found in these desert forts along the Quseir-Nile road that most food, wine, and other commodities were imported from the Nile Valley. Yet, some vegetables were locally cultivated, as were chickens and pigs. There is even slight indication that beer may have been brewed in some of these remote desert forts. According to the ostraca found in them, terms of service in these praesidia ranged from at least three to seven months; they may have been longer for some of the soldiers.

Most praesidia on these three roads, and on other routes in the Eastern Desert, lay on low ground. In fact of the three thorough fares examined here, only the fort at al-Heita noted above, lay on higher ground. Common sense and basic defensive military tactics In normal circumstances would dictate their location on high ground. Yet, most are placed immediately at the base of a mountain or hill. If the mission of these praesidia had been to protect large swaths of territory then their location on elevated terrain would have been a sine qua non. Clearly this was not the case. It was unrealistic to attempt to control the entire Eastern Desert; this would have required a huge expenditure of money and troops. The forts had much more limited and realistic objectives; they were carefully situated along regularly and frequently used routes and guarded precious water supplies. They were also designed to control nodes of mineral wealth, lines of communication and travel, and monitor wayfarers.