The first consideration of anyone venturing into the Eastern Desert is the availability of adequate quantities of potable water (Figs. 13.1-13.2). Without this primary resource no other activity can take place. Yet precipitation in the Eastern Desert, where measured scientifically in recent times at Quseir on the Red Sea coast, is quite meager, ranging from 4–5 millimeters per annum. Averages were probably much the same in the Ptolemaic-Roman period, though perhaps somewhat greater early in the pharaonic era before the Eastern Desert became increasingly the desiccated region that it is today. Thus, ancient technologies used in the area for finding, storing, managing, and distributing this most basic of all human needs had, by necessity, to be very highly developed.

We understand firsthand the preoccupation with water supplies that ancient peoples had while living in the Eastern Desert. During our numerous desert surveys and archaeological excavations over the years, which we have conducted in both summers and winters, we constantly monitor our large array of twenty-liter plastic jerry cans to ensure that they are not leaking and that we have enough water to carry us until we can be resupplied or until the end of our fieldwork. Since it is basically unavailable to us in the desert, carrying hundreds of liters of water for a survey of several weeks takes up most of the space and weight in our vehicles. This problem is, of course, greatly magnified on an excavation lasting several months and involving scores of people. We do not have the advantage that our ancient forbearers had of obtaining much, if any, of our water from desert wells. These are now few and far between compared at least to the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. Today, those wells that we do encounter are often the preserve of the Bedouin who must water their charges; it would be most inappropriate of us to tap these for our own uses.

Fig. 13.1: Map showing sites in the central Eastern Desert with cisterns and wells or recipients of water supplies mentioned in this chapter.

As we noted in Chapter 5, our personal experiences have shown that a human, when moderately exerted in the desert, drinks at least four to six liters of water a day in the summer, less in the winter. When we add to this amount additional water consumed for bathing, cooking, and so on, we have found that each human requires an average of ten to fifteen liters per day in the summer, less in the winter.

Fig. 13.2: Map showing sites in the southern Eastern Desert with cisterns and wells or recipients of water supplies mentioned in this chapter.

Water used by donkeys and camels, the primary pack animals, would have been critical considerations to those living and traveling through the region. The amounts they consumed would, of course, vary dramatically depending on a whole host of factors including their ages, health, and size, the distances to be traveled, weight of the loads and temperature. On a typical travel day a donkey can carry 70 to 90 kilograms in panniers while a camel averages 200 to 225 kilograms; a camel can carry substantially more than this if transporting over shorter distances, as can a donkey in a non-desert environment. A camel can drink water far more saline than a donkey can tolerate and can, if necessary, go far longer without water than a donkey. A donkey does, however, have the advantage of being able to negotiate stonier ground than a camel.

Based on modern studies in hot weather a pack donkey must drink about ten liters a day while a pack camel averages twenty liters. Stories of great endurance prove exceptions to the rule. In 1926, for example, G. W. Murray, when visiting the Gebel ‘Elba area in the extreme southeastern corner of the Eastern Desert, reported that his camels did not drink for an extraordinary 128 days! This, he writes, was due to cool weather, short, easy daily journeys, and the animals’ consumption of copious quantities of succulent plants.

Of course, Murray’s was a one time visit. How and where exactly did ancient peoples obtain water in the desert on a more or less regular basis for relatively large numbers of humans and animals?

We have ample evidence of the prominent role water played for people in the Eastern Desert from the Old Kingdom period (2649–2152 BC) until Roman times (30 BC-seventh century AD). One of the earliest hydraulic features in the Eastern Desert is the remains of an Old Kingdom installation at a location called Sad al-Kafara (Dam of the Infidels), about thirty kilometers east of Cairo. The dam was probably constructed during the reign of Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Khufu (2551–2528 BC), builder of the largest pyramid at Giza. The dam would have measured originally about 113 meters long at its top by about 14 meters high by approximately 98 meters thick at its base. Parts have since been washed away and the structure may never have been completed in antiquity. Its precise purpose remains a mystery.

Other evidence from the New Kingdom, specifically the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, also deals with water use in the Eastern Desert. From the Nineteenth Dynasty there are two inscriptions from the reign of Seti I (1306–1290 BC) and one from his more famous son Ramesses II (1290–1224 BC); surviving from the Twentieth Dynasty is a map. The Seti inscriptions, found at the rock-cut temple built by that pharaoh at al-Kanaïs, mentioned in Chapter 6, lie forty-six to forty-seven kilometers east of Edfu. These texts indicate that wells were dug in the proximity of the temple to provide water to those voyaging between the Nile and the desert gold mines. Ramesses’ inscription appears on the famous Kubban Stele where he boasts of finding water in a well dug to a depth of only six meters while his father had previously found none. Ramesses’ well, like those of his father, was also intended to support gold mining activities in the desert.

The Turin Papyrus map, dating to the reign of Ramesses IV (1163–1156 BC) and described in Chapter 4, shows, among other features, a wall surrounding a well, probably to prevent infilling by flood-borne sediments. There is also a cistern, gold mines, and a bekhen stone quarry as well as roads radiating from the map’s focal point off to other regions of the desert. The well on the map probably signifies the ready availability of water in the area rather than a single specific well. Water would have been used for human needs—drinking, washing, cooking, irrigation for small gardens—and animal consumption, as well as the industrial processing of gold we describe in Chapter 9. We know that even during his short reign, Ramesses IV sent several expeditions to the region, the last one being huge and comprising 8,362 men. Unless some or all the water these thousands of human beings required was brought from the Nile, about eighty-four kilometers away, which is highly unlikely, they would have obtained what they needed from wells excavated nearby. No trace of these ancient wells would survive, of course, as they were long ago smothered by water- and wind-borne sand.

Times of Year to Travel in the Desert

Ancient graffiti and ostraca dated to Roman times found in the desert, taken together with known sailing seasons to and from the Red Sea ports, indicate that desert travel, quarrying, and mining operations were perennial and not confined only to the cooler winter months. Such was probably also the case in earlier times. Since travel into the desert took place perennially, the pressure on water supplies must have been especially intense during the summer months. Fortunately, we have far more evidence for how water was stored and distributed in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods than any other era of antiquity.

Sources of Water in the Eastern Desert

There were, and are still today, two major sources: surface runoff after rare and heavy rains, and sub-surface water. The former is mainly seasonal, appearing after the rains, when they do fall, usually in November and December; we also include springs in this category. On the other hand, subsurface water is perennial and, as a result, far more dependable. Let us examine these supplies.

Surface water is, of course, easier to locate and obtain than sub-surface, but its quantity, quality, and dependability are extremely erratic. One method is natural accumulation of rainwater in qulut. Another is rainwater run-off flowing from mountains that is deliberately channeled by human action into cisterns, water catchments or perhaps smaller, more portable containers. The last is from springs.

Qulut occur naturally in depressions of eroded hard stone, mainly igneous and metamorphic, like granite and other crystalline rocks that are found along wadi beds or at the bases of seasonal waterfalls. They hold vastly varying quantities of water depending, of course, on their sizes, the amount of water that has accumulated in them and their locations in direct sun light or shade. Qulut would not have played a major role as regular and reliable sources of water acquisition for consumption by humans or pack animals though the Bedouins might have—as they do today—occasionally watered herds of goats, sheep, donkeys, and camels at such places. Most qulut are only useful at certain times of year, immediately following heavy rains. They are often not easily accessible, or large enough along or near the major trans-desert roads in the region for regular and sustained use.

Let us provide some examples of exceptional qulut we have seen during our desert surveys. The most impressive must be the one near Umm Disi, west of Hurghada. When we visited it in August 1997 it was large enough to swim in (Pl. 13.1). From reading accounts of earlier visitors to this remote location part way up a mountain slope it is evident that amounts of water there could vary amazingly from one year to the next depending, of course, completely upon rainfall. One visitor wrote that he saw the qalt at Umm Disi bone dry while another reported that it brimmed with an estimated one hundred thousand liters of water.

Other qulut we have seen on our surveys are much smaller than Umm Disi. The one about 1,550 meters down the wadi southeast of the center of the late Roman-era desert settlement of Wadi Shenshef, 21.3 kilometers in a straight line southwest of Berenike, was quite large when we saw it in winter 1996. There were other pools with varying amounts of water in them between that large qalt and the main settlement in Wadi Shenshef. We do not know if this qalt and nearby pools supplied the ancient settlement, though they potentially could have done so whenever sufficient amounts of water had accumulated in them.

A French project conducted in the late nineteenth century reported two qulut in the region of the ancient Roman beryl/emerald mines at Nugrus and Sikait. Our surveys have not seen these qulut, but the French go on to report that one of them was in a small side tributary of “Wadi Nougourans” in a depression in gneiss, a hard ‘basement’ rock. It must have contained an impressive amount of water, for their report published in 1900 indicates that the source was sufficient for their entire field season for twenty persons. The same French team noted another qalt in Wadi Sikait that produced potable water for only a short time. In addition to being easily and quickly fouled by animals, that water remaining in qulut becomes increasingly saline as it evaporates. This makes qulut even less reliable as sources of potable water.

Springs (‘ayn singular/‘uyun plural in Arabic) were another source of water in the Eastern Desert for ancient travelers. Though these derive from the subsurface, they appear naturally on the surface and so are best discussed in this category. Springs usually produce very pure water, but are rare in the Eastern Desert and generally remote from most areas of substantial habitation or from the major ancient desert roads. They also provide too little water to be important perennial supplies though they are good supplements or sources for very limited numbers of people and animals making infrequent visits. The early twentieth century British geologist F.W. Hume described two of the most noteworthy springs he knew of in the Eastern Desert, one in Wadi Qattar and another in Wadi Dara. One of our surveys in January 1989 visited Qattar, just off the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites–Nile road, but we found that spring dry.

During our fieldwork in the area of the ancient beryl/emerald mines of Sikait in June 2002 one of our ‘Ababda Bedouin workmen showed us a small spring about one kilometer east of the main site. He claimed that it produced about ten liters of potable water per day. Hume also noted a spring near Sikait that produced about fifty liters of “excellent water issuing from a rock drop by drop.” He did not, however, indicate where in the Sikait area he saw this spring, but his description suggests that it was not the same one the Bedouin showed us in 2002.

Richard Pococke was born in Southampton in 1704 and studied religion at Oxford. He visited (perhaps in 1737–1741) Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, Crete, Cyprus, and Greece. The first volume of his Description of the East and Some Other Countries was completely devoted to Egypt. His extensive descriptions of the ancient monuments were accompanied by plans, maps, and drawings. Among his maps were the first modern one of the Valley of Kings and the first accurate map of Egypt.

His interest was not restricted to ancient monuments; his book also describes the landscape, flora and fauna, and the habits and material culture of the eighteenth-century Egyptians. Pococke drew a map of Cairo and described Coptic monasteries and Islamic monuments. After his lengthy travels he took up an appointment as bishop of Meath. He died in 1765.

Another example we saw in September 2002 was in the deep south of the Eastern Desert. This is a spring associated with the Ptolemaic temple façade at Bir Abu Safa, which we described in Chapter 6.

Several forts on the Berenike–Nile roads used artificially built channels, apparently in early Roman times, to direct rainwater flow from nearby mountains into the cisterns (lakkoi) inside adjacent praesidia. We do not know whether this was the sole source of water for these installations or merely supplementary to more traditional methods of acquisition from wells, which were located either inside or outside the forts’ walls.

Subsurface water, mainly obtained from wells (bir singular/abyar plural in Arabic), was, and remains today, the most common, abundant, and reliable source of water available in the Eastern Desert. While we have descriptions from pharaonic sources about the excavation of wells, none from this period survive in the archaeological record. Our best archaeological source for the physical appearance of wells is from Ptolemaic and especially Roman times. Wells (hydreumata) and their partially sanded-up remains survive inside numerous praesidia in the Eastern Desert. Most are circular in plan, frequently quite large, and they often dominate the center of these desert forts.

One of the most impressive wells we have ever seen is in the large praesidium in Wadi Kalalat only about 8.5 kilometers southwest of Berenike (Figs. 13.3 and Pl. 13.3-13.4). This huge installation provided some of the water supply for Berenike; it, and a small fort only nine hundred meters to the northeast, guarded the southern and western approaches to Berenike in the early Roman period. The larger fort has a stone-lined well in its center that measures about thirty-two meters in diameter, with a stairway leading into the sandy depths, probably originally to the surface of the water. The well is now almost completely filled up with wind-blown sand, but its imposing contours are still visible. The large fort was abandoned in the second century AD for reasons that still remain a mystery; maybe the well water became too saline or the water table had dropped; thereafter a much more modest fort was constructed to the northeast. This smaller installation, also partially buried by shifting sands, may have had an interior well, but if so, it has been completely filled in.

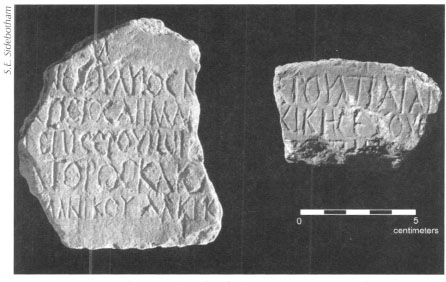

Fig. 13.3: Inscription fragments found in the large praesidium in Wadi Kalalat from the time of the prefect Servius Sulpicius Similis (AD 109–110), governor during the reign of the Roman emperor Trajan (AD 98–117).

Staircases provided access to many of these wells and remains of staircases can be seen not only in the Wadi Kalalat example, but also at others in the region. The finely preserved fort at al-Zarqa (ancient Maximianon) on the Myos Hormos–Nile road (see (see Chapter 4) has portions of the well staircase intact. Most ancient wells, where they are at least partially visible, were lined with locally obtainable cobblestones or fired bricks to minimize internal collapse and maintain some degree of water purity.

In the first part of the twentieth century the Geological Survey under British supervision re-excavated and relined many of these earlier Roman wells and added staircases and concrete basins. They did this, like their ancient predecessors, to facilitate mining and quarrying activities in the Eastern Desert. These modern repairs may provide some idea of what their ancient predecessors originally looked like. Examples of modern reworking can be seen at the Ptolemaic-Roman praesidium at al-Kanaïs (on the Berenike–Edfu and Marsa Nakari-Edfu roads) (Pl. 13.2) where the modern well and basin are probably not near the original location of the ancient ones. We have also noted modifications to the station at Qattar on the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites–Nile road made in the 1920s or 1930s when, as an ‘inscription’ carved into the wet concrete of one of the hydraulic tanks indicates, Farouk was Amir of Egypt (1920–1937). Other sites with modern adaptations or modifications can be seen at Abu Greiya on the southern portion of the Mons Claudianus–Nile road just north of the modern asphalt highway about forty-two kilometers from Qena, and at the praesidium at Abu Zawal (Place/Father of Ghosts), a gold mining camp, also on the Mons Claudianus–Nile road. The cisterns and well inside the station at Abu Gariya (see Chapter 3) on the Via Nova Hadriana have also been remodeled in modern times as have those at Seyala and Bir al-Hammamat on the Myos Hormos–Coptos road.

The mid-nineteenth-century German traveler Karl Richard Lepsius was impressed by the ancient and still functioning well at Bir al-Hammamat noting that it was “broad …. , about eighty feet deep, lined with stones, into which there is a descent by a winding staircase.” The Arabs told Lepsius that Christians had built it and recent archaeological surveys and excavations at the nearby gold mines at Bir Umm Fawakhir date that site to the fifth and sixth centuries AD, the Christian period in Egypt. We would expect traffic between Bir Umm Fawakhir and the Nile to make frequent use of water facilities en route and the supply at Bir al-Hammamat was a natural stopping point, one those responsible for the miners’ welfare would have improved to facilitate access to the water. The stop at Bir al-Hammamat, whose ancient name remains unknown, also catered to later Muslim pilgrims making the hajj to Mecca from the Nile Valley of Upper Egypt as attested by the remains of a small mosque built into one corner of the praesidium. The well itself looks the same today, though clearly the superstructure covering it is a more recent addition of about 1830 or perhaps later.

Roman-era praesidia in many instances probably also obtained water supplies from extramural wells. Extensive ground penetrating radar studies of areas around some of these forts and wadis adjacent to the main ancient trans-desert roads should be undertaken to determine if this was the case and extent to which it was practiced.

Civilian or quasi-civilian settlements in the Eastern Desert (see Chapter 10) include those whose exact status remains uncertain. Some of these communities comprise over one hundred buildings and must have had, a priori, reliable and perennial sources of water. We have conducted site intensive surveys of six such settlements, which may or may not have been Christian laura-hermit communities. These ranged in size from forty-seven to about 190 (at Umm Heiran near Sikait) structures each comprising between one and three relatively small rooms, rarely more. Sometimes there are larger structures on these sites.

Our surveys of these communities found many similarities. The sites, in general, dated from late fourth through sixth centuries AD, sometimes later. All would have acquired water from wells sunk in their environs. We collected large numbers of shards of a type of jar called Late Roman Amphora 1 from these desert settlements and know that these jars were made in Cyprus and Cilicia on the southern coast of Asia Minor. It is surprising to find amphoras imported from such distances at these relatively remote and ‘low status’ sites. Yet, we know from ancient literary sources that some Christian desert settlers consumed imported wine. The Christian writer Palladius writing his Historia Lausiaca in AD 419–420 recounted his personal experiences as a Christian hermit in the Egyptian desert and he is one of the more important sources for the history of early Christian monasticism in Egypt. Necessity and practicality would have compelled the residents of these humble settlements to recycle the jars in which wine may have originally been shipped and stored. Once empty of their original contents, however, these jars would have served ideally as water containers. Palladius, in fact, mentions that Cilician pots and water jars were used at a number of Christian desert communities and it is likely no coincidence that we have found fragments of shipment and storage jars of this type, the Late Roman Amphora 1 amphoras noted above, in great numbers at all of the putative Christian sites we studied in the Eastern Desert.

The large Red Sea ports hauled potable water from varying distances in the desert because water deriving from wells dug by the sea would have been too brackish for human consumption. We know in the case of Berenike that at least three forts ranging from 7.2 to 8.5 kilometers west of the city, two in Wadi Kalalat and one at Siket, supplied drinking water to the port and we have more to say about Siket in Chapter 15. At Myos Hormos, too, it seems drinking water came from either Bir Nakheil immediately west of the port or from Bir Kareim about thirty-five kilometers to the southwest or perhaps from both places. Evidence suggests that water was laboriously hauled by pack animals from the wells to the ports; there is no evidence that aqueducts were used.

Given the high rates of evaporation in the desert and increased salinity of water remaining after evaporation it was essential to store and protect it carefully. As we have already mentioned, modern average evaporation statistics in the Red Sea Governorate of Egypt are 2,500 millimeters per annum versus annual precipitation of four to five millimeters. With similar rates in the Greco-Roman period it was critical that water be ingeniously retrieved, carefully stored, and sparingly distributed. The wells and cisterns visible throughout the desert are testaments to Ptolemaic-Roman care for the water supplies. Protective lining of wells with stones or bricks allowed them to be deeper; these linings also minimized collapse thereby keeping the water more pure. Thick coatings of lime-based waterproof plaster covering carefully crafted water cisterns made of cobbles or fired bricks, combined with shelves at the tops on which would be affixed wooden and leather or cloth covers, reduced evaporation and kept the water cleaner by reducing the amount of dirt that might otherwise blow or be accidentally dropped into them.

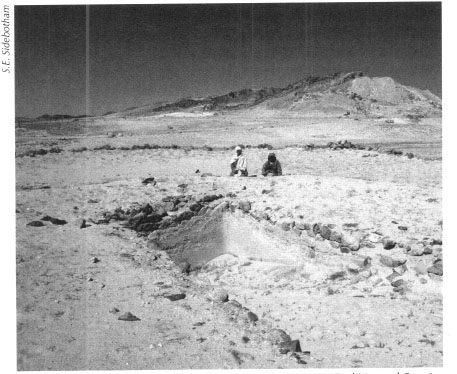

Reliable figures on amounts of water stored are sporadic and derive only from our own calculations and those of our European colleagues. No ancient written sources from the region record the amounts of water available at any of these wells or cisterns. At the Ptolemaic station at Abu Midrik on the Berenike–Apollonopolis Magna road we estimate that the two circular cisterns there could hold approximately 88,000 liters though there is no way to determine if they ever actually did so or how often. The early Roman praesidium at the quarry at Umm Wikala held 8,800 liters while that at the Ptolemaic-early Roman station at Rod Umm al-Farraj (Fig. 13.4) on the Marsa Nakari–Edfu road held approximately 39,000 liters. French archaeologists report that the tanks at al-Muweih (ancient Krokodilo) on the Myos Hormos–Nile road had a theoretical maximum capacity of over 200,000 liters. A small cistern inside the main fort at Mons Claudianus, on the other hand, held a mere ten thousand liters.

Fig. 13.4: The cistern at the Ptolemaic-early Roman station at Rod Umm al-Farraj.

Karl Richard Lepsius was born in Saxony in 1810. He was the founder of modern scientific archaeology and is best known for his catalogue of Egyptian archaeological remains and for establishing a chronology for Egyptian history. He studied Greek and Roman archaeology at Leipzig, Gottingen, and Berlin, where he received his doctorate in 1833. Before his first visit to Egypt he expanded upon Champollion’s work on hieroglyphs. Sponsored by King Wilhelm IV of Prussia, Lepsius led a famous expedition to Egypt and Nubia between 1842 and 1845 the purpose of which was to record monuments and collect antiquities. The expedition was a milestone as it contributed greatly to our knowledge of Egyptian monuments (many now lost or badly damaged), language, mythology, and geography. Upon his return to Prussia, Lepsius was appointed professor at Berlin University and he published his findings in the monumental multi-volume Denkmaler aus Ägypten und Äthiopen (1849–1858). The set ones are comparable to the Napoleonic magnum opus Description de l'Egypte. In 1865 Lepsius became keeper of the Egyptian Antiquities Department in the Berlin Museum. In the same year he led another expedition to the Delta region of Egypt. His last visit to Egypt was to witness ceremonies surrounding the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. He continued writing until his death in Berlin in July 1884.

Overall the larger sizes and greater numbers of the Roman-era forts compared to their Ptolemaic predecessors suggest that there were more people and animals residing in and passing by these installations in the early centuries of the Christian era than previously. Evidence of aqueducts or other devices to divert, control, or deliver water from one point in the desert to another do survive though we do not always understand precisely their functions. Conduits could have been used for both water acquisition and distribution though the bulk of the evidence suggests that most pipelines were for distribution. There must have been numerous examples of piping water from sources to points of storage and distribution in the Eastern Desert in antiquity, but few have been identified or studied. Many are no doubt hidden by sand or, in some cases, no longer survive.

Lengths of pipes or evidence for their existence indicate conveyance of water from hydreumata inside praesidia to adjacent or nearby lakkoi in several examples including the large fort in Wadi Kalalat, at Abu Greiya (possibly ancient Jovis) on the Berenike–Coptos road and likely that in Wadi Safaga on the Via Nova Hadriana. French archaeologists have also found them at al-Zarqa (ancient Maximianon) on the Myos Hormos road and at Khashm al-Menih/Zeydun (ancient Didymoi) on the Berenike–Coptos route.

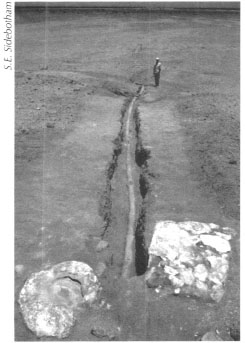

There are only two examples of terra-cotta and stone pipes built over distances of several hundred meters or more that have been recognized and studied in the Eastern Desert. One is late Roman and the other can be no more precisely dated than to the Roman era. Both examples carried water to military installations. The one at the late Roman fort at Abu Sha‘r on the Red Sea coast north of Hurghada (see Chapter 3) brought water from a well about one kilometer southwest of the fort under pressure through a closed system of terra-cotta pipes coated on the outside with plaster (Figs. 13.5-13.6). This pipeline entered the fort through the main western gate, but its terminus inside the fort remains uncertain, though it may have been the headquarters (principia), which was later in the fourth or early fifth century converted into a church. There was probably also a branch of this water pipeline that bifurcated just before reaching the west gate and headed north supplying the fort’s large extramural bath.

The second example of a pipeline brought water about 477 meters from the well at Bir Abu Sha'r al-Qibli to a small praesidium which we excavated in part in 1993. This small fort had been a station on both the second century AD Via Nova Hadriana (sec Chapter 3) and had also served the late Roman fort at Abu Sha‘r which lay 5.5 kilometers to the east. Thus, a precise date for this pipeline cannot be established. The internal diameter of this plaster and rock conduit was about ten centimeters and water flowing through it would have filled several water tanks the remains of which can still be seen located outside the southern wall of the small praesidium.

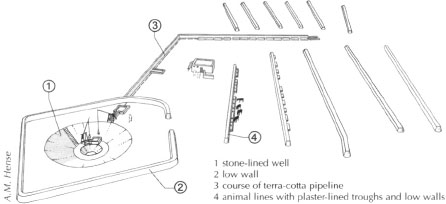

Our surveys have also found evidence for the conveyance of water from inside forts to small extramural water tanks, presumably to supply varying numbers of passing pack animals. Such external tanks can be seen at Deir al-Atrash (‘Monastery of the Deaf One’) on the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites–Nile road, at Abu Gariya on the Via Nova Hadriana, and at Abu Greiya (ancient Jovis?) on the Berenike–Coptos road. There are also large, but extremely damaged, remains of hydraulic tanks both east and west of the main fort walls of the large praesidium in Wadi Kalalat near Berenike. Moreover, there is a large unfortified hydraulic installation in Wadi Abu Shuwehat on the southern route between Mons Claudianus and the Nile at Kainepolis (Figs. 13.7-13.8). Here there was at least one large well surrounded by a low stone wall, no doubt to keep animals from approaching too close to the source and also to prevent waterborne sediments from clogging the water source. One or more terra-cotta conduits, now in fragmentary states of preservation, fed water from this well to numerous troughs made of terra-cotta and plaster associated with a series of animal tethering lines that accommodated traffic hauling stone from Mons Claudianus to the Nile. A small hole part way up and through the eastern perimeter wall at the praesidium of Maximianon on the Myos Hormos–Nile road possibly conveyed water for extramural consumption by animals or liquefied waste from the fort interior to the exterior.

Fig. 13.5: Pipeline leading from a well to the late Roman fort at Abu Sha‘r, about one kilometer away, on the Red Sea coast north of Hurghada.

Fig. 13.6: Pipeline from a well one kilometer from the main fort at Abu Sha‘r.

There has been some debate about the function of the so-called ‘aqueduct’ leading from the hydraulic complex in Wadi Umm Diqal toward the main settlement at Mons Claudianus. Earlier visitors believed that the long stone walls were the remains of an aqueduct, but recent investigations by a French-directed team that excavated and surveyed extensively in this region between 1987 and 1993 do not support this identification. More likely, the walls diverted wadi floods (seyul/seyal in Arabic) away from important architectural features or graves; possible parallels have been reported near Bir Nakheil west of Myos Hormos and in Wadi Qattar on the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites–Nile road; our survey has not seen these. Others of similar function survive in Libya and in the ancient Kingdom of Kush in what is today Sudan.

In 1826 J.G. Wilkinson, the same British traveler who drew the first plan of Berenike, noted a well and small length of possible aqueduct leading away from it toward lower ground in Wadi Abu Greiya (ancient Vetus Hydreuma) (Fig. 13.9), the first stop on the road leading from Berenike to the Nile. This well and putative aqueduct lay immediately south and at the base of the mountain atop which perches a facility our survey named ‘Hill Top Fort Number 5.’ Our survey work in the area has not revealed the conduit or wall that appears on Wilkinson’s plan, but comparison of Wilkinson’s numerous other plans and maps of antiquities that he drew in the Eastern Desert with actual remains have proven him to be generally accurate and reliable. Thus, we have no reason to doubt the existence of the wall or conduit he drew though we might argue with him about the function. Perhaps Wilkinson’s now missing feature was a water diversion wall similar to that found in Wadi Umm Diqal in the Mons Claudianus area or some type of conduit designed to transport water from the well near the hilltop forts downhill and eastward toward the two large low-lying wadi forts in Wadi Abu Greiya about two or three kilometers away following the wadi floor. The nearest fort to the well and now missing wall is early Roman in date, precisely the period when travel along the road between Berenike and the Nile would have been at its peak and extra water would have been required for human and animal visitors.

Fig 13.7: Water distribution system and animal tethering lines at the large unfortified hydraulic installation in Wadi Abu Shuwehat.

Fig. 13.8: Water distribution system and animal tethering lines at the large unfortified hydraulic installation in Wadi Abu Shuwehat.

Fig. 13.9: Plan of three forts at Vetus Hydreuma, drawn by J.G. Wilkinson (Ms. G. Wilkinson dep.a.15.49 (middle); Gardner Wilkinson papers from Calke Abbey, Bodleian Library, Oxford; courtesy of the National Trust).

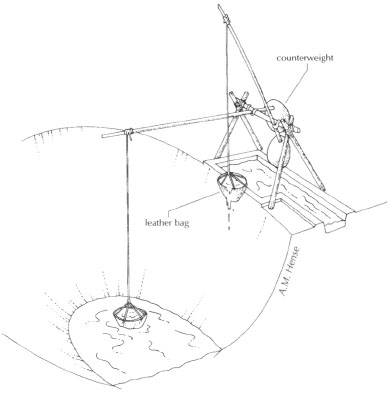

Water lifting devices may also have been used at several Eastern Desert installations including Deir al-Atrash and the lower fort at al-Heita, both on the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites–Nile road, perhaps at Abu Zawal, noted above, at Gerf (likely the ancient Aristonis) on the Berenike–Coptos road and at Abu Sha‘r al-Qibli on the Via Nova Hadriana also noted above. Called a shaduf in Arabic today (Fig. 13.10), a kelon in Greek and a telo, tolleno, or ciconia in Latin, this device can still be found along the Nile and was used to convey water from a lower elevation to a higher. A shaduf is basically a long pole with a bucket-like device at one end and a counterweight, often made of mud or clay, on the other, resting on a vertical beam that allows the long pole to dip down into the water source.

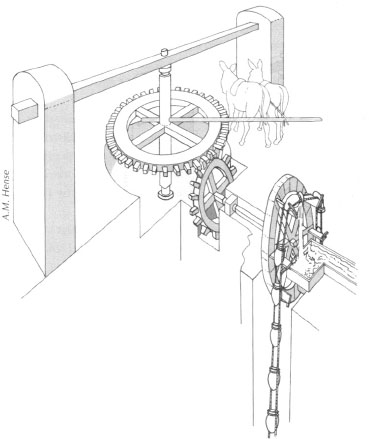

Waterwheels, saqyas in Arabic, mechane in Greek, were also used in the Eastern Desert in Roman times (Fig. 13.11). These devices were animal-powered waterwheels that had pots attached to lift water to higher ground. British excavators believe that such a device was probably used at Mons Porphyrites to draw water from a well just below the main fort. There are remains of saqya pots and references to women operating a waterwheel in some ostraca from the quarries at Mons Claudianus, from the station at Didymoi on the Berenike-Coptos route and from Maximianon on the Myos Hormos–Coptos road. Saqya pots and fragments have been found especially at late Roman/Byzantine sites in Egypt and papyri and other texts record their use throughout the land at that time. A large Roman-era station on the Mons Porphyrites/Mons Claudianus/Abu Sha‘r–Nile road with extensive hydraulic facilities and animal tethering lines is today called al-Saqqia (Pl. 13.5) which may suggest the use of waterwheels here in Roman times.

Fig. 13.10: Water lifting device, called a shaduf in Arabic

Fig. 13.11: Drawing of a waterwheel, called a saqya in Arabic.

Water would have been used to irrigate desert gardens, which are known to have existed from archaeological remains and from references in ostraca especially along the Myos Hormos–Nile road. There is also evidence for such desert cultivation at and near Berenike and near the praesidium at Abu Sha‘r al-Qibli. As we noted earlier, courtyards of houses at the Roman emerald mining settlement of Sikait preserve small stone boxes that may have contained trellises used to support growing crops or to protect young saplings (see Chapters 10 and 12).

There are also references in various Christian literary sources to desert cultivation. In the fourth and fifth centuries, the Historia Monachorum in Aegypto, Athanasius ‘The Life of St.Antony, and Palladius’ Historia Lausiaca all report that monks residing in the desert had their own gardens that produced fruits, vegetables, and some grains to make bread. The practice was probably more widespread in antiquity than we realize as analysis of mud bricks used in structures in the Eastern Desert shows pollen from locally cultivated plants mixed with the bricks.

Small-scale industrial activities in the desert also required water. Christian desert hermits wove baskets, ropes, and mats, and fibers used in their manufacture would have been soaked in water to make them more pliable. Brick making, metal working, gold refining, and glass working, all of which are activities known either in the Eastern Desert or at the Red Sea ports, would also have required water.

Possible pollution of water supplies as a result of their use in mining, quarrying, and industrial activities raises interesting and still to be studied questions about the impact on the health of those residing in the region. Ostraca indicate constant health problems of the eyes and gastrointestinal systems of many living in the Eastern Desert. Could some of these problems be caused by pollution of the water sources?

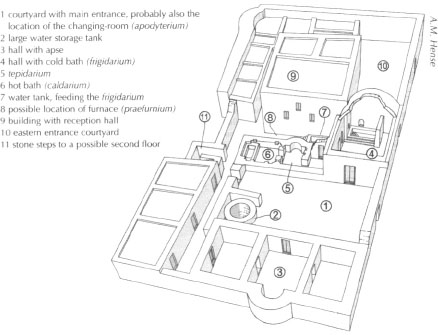

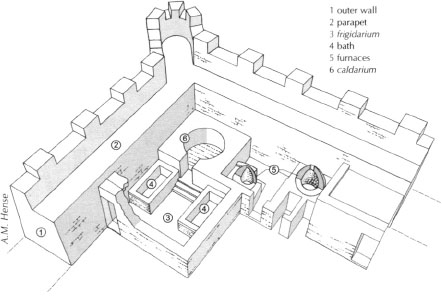

Few formal bathing facilities have been excavated in the Eastern Desert and most if not all have been found in Roman military contexts. More will probably be discovered as additional sites come under excavation. Thus far archaeologists have identified five baths in the region. Our excavations partially uncovered a relatively large one just outside the north gate of the late Roman fort at Abu Sha‘r (Fig. 13.12). Another smaller one can be seen at the quarry settlement at Mons Claudianus (Fig. 13.13). The praesidia at Maximianon (Fig. 13.14) on the Myos Hormos–Nile road and at Didymoi on the Berenike–Coptos road also each preserve small baths. A fifth has been found near the large fort at Mons Porphyrites. Interestingly, excavations of two large civilian settlements in the region, the Red Sea ports of Berenike and Myos Hormos, have revealed no baths, but surely such communities must have possessed them. At Berenike our excavations immediately north of the Serapis temple recovered glass items used specifically for bathing and recycled kiln-fired bricks preserving remains of mortar, which must have had an original hydraulic function. These artifacts point to the possible presence nearby of a bathing facility.

Fig. 13.12: Bathing facilities just outside the north gate of the late Roman fort at Abu Sha‘r. Scale = one meter.

Fig. 13.13: Bath at the quarry settlement at Mons Claudianus.

Accommodations for animals hauling stone especially between quarries and mines in the desert on the one hand and the Nile on the other also provided water for their consumption. Such facilities are especially evident on roads between Mons Porphyrites and Mons Claudianus and the Nile, but also between Marsa Nakari and the Nile and the emerald mines at Sikait and the Nile. Good examples of these include Badia’, Bab al-Mukhenig (Pl. 13.6), and Deir al-Atrash on the Mons Porphyrites–Nile road and Abu Greiya on the Mons Claudianus–Nile road. Farther south in the Eastern Desert the station at Rod Umm al-Farraj on the Marsa Nakari–Nile road and the one at Wadi Gemal East on the Sikait–Nile road are excellent examples. In addition to the watering facilities, tethering lines, as we have seen in Chapter 4, were also key features of these stations catering to traffic passing between quarries and mines on the one hand and the Nile on the other.

Fig. 13.14: Bath at Maximianon fort.

The methods used for water acquisition, storage, protection, and distribution in the Ptolemaic and Roman era in the Eastern Desert were undoubtedly similar to those used in earlier pharaonic times in the region. The most noteworthy differences would have been the generally larger scales and greater frequency with which these activities in the later period would have been conducted.

In Ptolemaic and Roman times it seems that mainly the military was responsible for all aspects of water procurement and distribution in the Eastern Desert. This is evident from the fact that most if not all of the important water sources known to the Ptolemaic and Roman officials were undoubtedly guarded or otherwise fortified. No surviving manuscripts of ancient authors discuss this and few of the thousands of ostraca and papyri found in the region are helpful in shedding light on this issue either. Inscriptions found at some of the praesidia and stops along the desert highways indicate that the periods of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC) and the Flavian emperors (AD 69–96) were ones of concern for water procurement and protection. There must have been additional eras of repair and refurbishment at the ports, mines, and quarries and at other peak periods of activity in the Eastern Desert. These would likely have been especially in the early Roman epoch from the emperors Augustus and Tiberius (30 BC-AD 37), the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian (AD 98–138), the rule of the Severan emperors (AD 193–217) and again in late Roman times beginning in the middle of the fourth century when there was an evident renaissance in the Red Sea trade and in gold mining activities in the region.

Clearly more survey and excavation must take place in the future in the Eastern Desert and along the Red Sea coast in order to have a better idea of how this important issue of water supply was handled.