The Temples and Shrines of the Eastern Desert

As one might imagine, over the long history of human activity in the Eastern Desert, many of those who dared to travel, work, and live in this hostile environment came from the Nile Valley and beyond. They brought with them their cultural baggage including, of course, their languages and religious beliefs. The latter must have been of special interest and concern in the alien and potentially deadly arid desert landscape. Prayers to a number of deities for good luck, safe travel, and good health appear on a wide variety of written documents including ostraca, papyri, and formal inscriptions as well as graffiti carved on the rock outcrops lining desert routes and around the all-important wells. The desire to appease and secure the good will of the gods is also obvious from a number of shrines and temples that have been found and studied. Who were the deities of special interest to those in the desert and how were they honored?

A wide range of evidence, including written as well as sculptural and architectural, survives in the Eastern Desert spanning the many millennia between pharaonic and late Roman times. Major centers of human habitation including some of the desert forts, the Red Sea ports and the quarries and mines, where carefully surveyed or excavated, preserve evidence of shrines, relatively elaborate temples and, later, churches. We cannot examine them all, but we will highlight the more interesting and better preserved of these remains.

One of the oldest pharaonic religious monuments in the Eastern Desert survives in Warn Gawasis on the Red Sea coast, between Safaga and Quseir. This Middle Kingdom (2040–1640 BC) shrine, comprising a number of stone anchors, was dedicated to sailors. French excavators found other places of worship at Gebel Zeit, north of Hurghada on the Red Sea coast. These pharaonic era sanctuaries were dedicated to Hathor “Mistress of Galena,” Horus “Lord of the Desert,” Min, and Ptah.

One of the most unusual pharaonic shrines in the Eastern Desert, however, survives at al-Kanaïs (Pls. 6.1-6.2), which ironically means ‘the churches’ in Arabic, though there is nothing notably Christian on the site. Located just south of the modern paved highway connecting Edfu on the Nile with Marsa ‘Alam on the Red Sea coast, and lying only about forty-six or forty-seven kilometers east of the former, there survives a Ptolemaic-Roman praesidium just north of a rock outcrop on which appear hundreds of inscriptions from many different eras. Just southwest of the praesidium and west of the bulk of the rupestral graffiti and inscriptions stand the well-preserved remains of a rock-cut temple built by Seti I (1306–1290 BC), father of Ramesses II (the Great) of the Nineteenth Dynasty. The door leading to the interior of this New Kingdom period temple has been blocked, sometime in the modern era, presumably to protect it from vandals, but the portico, comprising a colonnade with a roof, juts from the rock face and marks a grand façade for the now inaccessible interior. Affiliated and contemporary inscriptions indicate that Seti I ordered the small temple built together with a water station, a settlement, and a well. Presumably these structures, and the well, assisted those traveling across the region to exploit gold in the farther reaches of the desert.

From the Late Period (the Achaemenid Persian occupation: 525–404 BC and 343–332 BC) and Ptolemaic eras (late fourth century BC-30 BC) there survive few recognizable religious edifices in the Eastern Desert. There are two shrines dating from the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes (246–221 BC). One located at Umm Fawakhir on the Quseir-Quft road no longer exists. The second is a façade at Bir Abu Safa, deep in the southern reaches of the Eastern Desert.

Local Bisharin Bedouin indicated to our survey team that an ancient spring at Bir Abu Safa, together with a well, was one of several stops on an ancient track that connected Abraq to the Nile and that this putative trans-desert route terminated somewhere near Aswan. At some point in the late third century BC a small structure, now weatherworn, was cut into the lower mountain face immediately above the point where the spring surfaces. This small façade lies about one hundred kilometers southwest of the Ptolemaic-Roman port ruins of Berenike, some thirteen kilometers south of Abraq as the bird flies and about twenty-two kilometers via Wadis Hode in and Abraq south of the Ptolemaic and early Roman fort at Abraq.

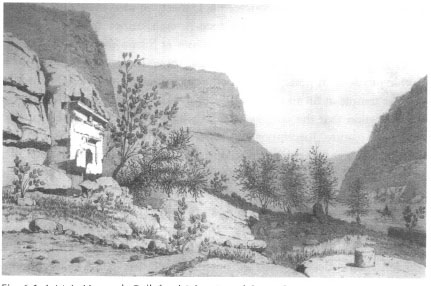

In March 1832 Linant de Bellefonds visited and briefly described this small shrine-like structure at Bir Abu Safa. His is the first recorded Western account of this feature. He also drew a picture of it and the immediate surroundings (Fig. 6.1), which he published, together with a map rnislocating the site, in his book L’Etbaye, pays habité par les Arabes Bicharieh. Géographie, ethnologic, mines d’or. He noted an inscription above the false door and believed it to be of Ptolemy ill Euergetes (246–221 BC). Yet he made no copy of the text so, until recently, we could not be certain that he was correct. If he was, year nineteen of Ptolemy Ill's reign would equate to 228/227 BC. Bellefonds believed that the square holes in the architrave/entablature were to accommodate some type of roof or awning to protect the water. The water, however, pools too far from the façade for such a putative sunshade to have been effective. More likely, if there was an awning, it was to protect any visitors standing immediately before the structure.

Fig. 6.1: L.M.A. Linant de Bellefonds’ drawing of the Ptolemaic-era temple at Bir Abu Safa, which he visited in March 1832. From L. de Bellefonds, L’Etbaye pays habité par les Arabes Bicharieh, géographie, Ethnologie, mines d’or (Paris: A. Bertrand, 1868).

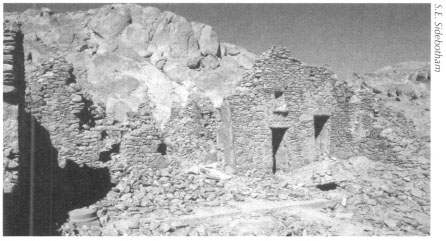

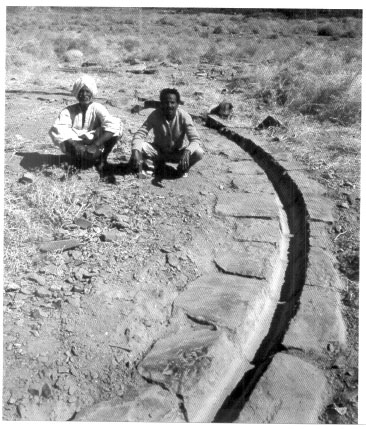

Our survey in September 2002 observed that the soft stone carving does, indeed, represent a building façade, measuring a mere 5 meters high by 4.6 meters wide, but lacking an interior. Although completely carved from the sandstone bedrock, lines have been scored into its façade to resemble quarried building blocks (Pl. 6.3). The faint traces of a four-line inscription in Greek survive above the main ‘opening.’ Our recent studies confirm Bellefonds’ conclusion that the structure was, indeed, dedicated by Ptolemy III in 228/227 BC.

This is the only structure of its type currently known from the Eastern Desert. Other rock-cut temples exist in the region, for example that of Seti I (1306–1290 BC) of the Nineteenth Dynasty at al-Kanaïs noted above, and those of various Egyptian-Greco-Roman deities from the Roman period, if not earlier, at the emerald mines at Sikait. Yet, the Sikait structures have interiors and their functions, though religious, seem to have nothing to do with water. Although the third century AD inscription on the smaller temple at Sikait records the construction of a well nearby, there is no indication that the temple itself had any religious affiliation with this hydraulic feature. Inscriptions associated with the temple of Seti I at al-Kanais indicate that the erection of a settlement and the excavation of a well were part of the same building project.

There was a long classical Greek and Roman tradition throughout the Mediterranean and elsewhere among peoples of the Near East, like the Nabataeans, of monumentalizing both water sources and terminal points for their conveyance in the form of fountains and nymphaea. The façade at Bir Abu Safa is clearly Ptolemaic, but in an Egyptian setting and connected with water. One might note that classical Greco-Roman associations of nymphs (who were guardian spirits of sources of pure water) with Pan are well known. Pan was often identified with the Egyptian deity Min in desert regions. His worship is readily apparent in the numerous Paneia (areas of worship dedicated to Pan) in the Eastern Desert. Thus, Pan would have been an appropriate guardian and focal point of devotion at the small shrine at Bir Abu Safa in the midst of the barren landscape of the Eastern Desert.

A small trickle of water, part of a geological syncline carrying rainwater through the mountain, emits just below the western side of the façade and runs downhill where it pools beneath an acacia tree. Today Bisharin Bedouin water their sheep, goats, donkeys, and camels at a nearby well about one hundred meters west of this ‘temple.’

We have also discovered small enclosed structures at gold and amethyst mines of Ptolemaic and early Roman date that appear to be religious in nature. We have found these at the putative Christian laura community at Bir Handosi, at the gold mining center of Bokari, and at the amethyst mining settlement in Wadi Abu Diyeiba.

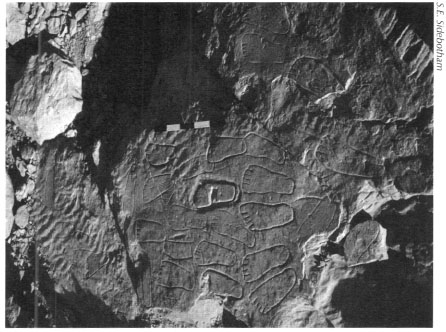

During a survey we conducted in June 2004 at the amethyst mining area of Wadi Abu Diyeiba, southwest of the modern Red Sea port of Safaga, we found fragments of half a dozen inscriptions in Greek that record religious activities. Add these new discoveries to texts found previously in the area and a picture develops of Ptolemaic religious preferences of miners and Administrators from at least the second century BC if not earlier. Pan, Harpocrates, Isis, and Serapis were popular. At least one of the inscription fragments we found joined with and completed a text recovered and published many decades ago dating to the reign of Ptolemy VI and his wife Cleopatra II (175–145 BC). Some of the sandstone bedrock as well as looser stones around the main settlement, which must have been the administrative center for the mining operations, had carved on them representations of dozens of human feet and hash marks (Fig. 6.2). Found in other areas of Egypt and in the Nile Valley as well as other regions of the classical Mediterranean, such carved feet are sacred to Isis; the hash marks were elongated abrasions produced by deliberate rubbing made by pious pilgrims.

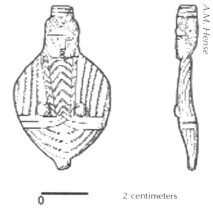

In conjunction with the Greek inscriptions we also recovered a small altar made from the locally available sandstone and two pictorial reliefs. One of the fragmentary reliefs preserves a portion of a female facing the viewer and wearing a headdress; this may be a representation of Isis. The second relief, which we reconstructed from numerous shattered pieces of sandstone, depicts a canopied structure supported by two simple columns. Beneath the canopy walking toward the left is a man holding what appears to be a flail or fly whisk. He may be a priest or other important official (Fig. 6.3).

Fig. 6.2: Carved representations of human feet and hash marks at the amethyst quarries at Wadi Abu Diyeiba. Scale = twenty centimeters.

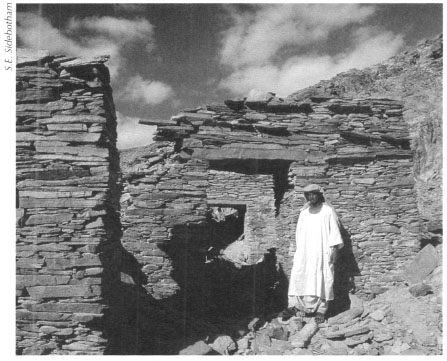

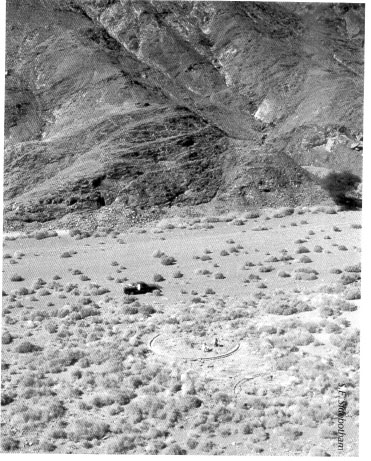

About a kilometer from the main settlement our survey found a small building atop a low ridge at the base of a mountain, approached by a series of steps, now destroyed, and a long narrow defined path (Fig. 6.4). Built of locally available granite with a small interior, this building resembles a small temple with surrounding precinct wall (temenos). The covered part of the structure is small and could not have been entered by a person standing upright; perhaps the interior originally held a cult image that has long since disappeared. Though our survey could not date the building, its association with the amethyst mining activities all around suggests that it also belongs to the Ptolemaic era, or, less likely, to early Roman times.

Fig. 6.3: Relief found at the amethyst quarries at Wadi Abu Diyeiba, probably dating to the second century BC. Scale = twenty centimeters.

Fig. 6.4: Small temple at amethyst quarries at Wadi Abu Diyeiba.

LOUIS MAURICE LINANT DE BELLEFONDS

Born in Lorient, France, on 23 November 1799, Louis Maurice Linant de Bellefonds, the son of a naval officer, was destined for a career at sea. After finishing his exams at age fifteen, Louis participated in a surveying and charting operation along the coasts of Canada and the USA. Three years later, during an expedition through several countries in the Near East, he was invited to proceed to Egypt to make maps and illustrations for several savants working there. After a year in Cairo, in 1818 he accompanied a team on an expedition as far south as Dongola. Being a brilliant artist and draftsman, he subsequently joined many expeditions in Egypt, Sudan, and Arabia. As he was asked to perform and lead new travels himself, he became the first European to see many ancient sites in Egypt's deep south and in Sudan. He explored Sudan and the White Nile in 1827, and searched for gold in the Eastern Desert under commission of Muhammad ‘Ali, the ruler of Egypt. In 1831 his wife died of cholera in their home in Cairo. He had produced by that time a large number of drawings and notes on countless monuments, many of which are now lost or severely damaged. After 1835 the time of his long exploratory travels was over, and he then focused on engineering work for irrigation projects. He also played an important part in designing the Suez Canal. Louis Linant de Bellefonds became Egyptian Minister of Public Works in 1869 and earned the title of Pasha in 1873. He died in Cairo on July 19, 1883.

Roman and Early Christian Sanctuaries

The most numerous, and best preserved surviving religious shrines in the Eastern Desert, however, appear in the latest period of ancient use of the region: the Roman and early Christian. Let us look at several of the more spectacular Roman period temples and other evidence of worship before engaging in an overview of some of the Christian remains.

The large quarry settlements noted in Chapter 4 at Mons Porphyrites, Mons Claudianus, and Wadi Umm Wikala (ancient Mons Ophiates) preserve some excellent examples of temples dating from the first and second centuries AD, but there are also equally fascinating examples as well at some other desert sites. We will look at the beryl/emerald mining settlements at Sikait and Nugrus, which also preserve impressive architectural and written remains of the hoary cults practiced by peoples residing in these remote locales. There are also a few others in the general vicinity of the quarries and emerald mines.

Sanctuaries at the Hard Stone Quarry Settlements

Studied off and on since the early nineteenth century, the quarry complex at Mons Porphyrites preserves, in the main settlement in Wadi Ma‘mal, at least three temples with accompanying inscriptions that leave their identification in no doubt. There is also a recently discovered inscription found in one of the satellite villages near Wadi Ma‘mal that appeals directly to two deities who were quite popular throughout the region in the Roman period. All the texts relating to the religious facilities at Mons Porphyrites date to the first and second centuries AD and all were written in Greek, the lingua franca of the Eastern Roman Empire. In the main settlement in Wadi Ma‘mal, where the large fort can be seen, lies undoubtedly the most spectacular religious structure at the site. Although dilapidated, this architectural gem of a temple to Serapis, who represents the conjoining of Osiris and the Apis Bull, and who was popular from Ptolemaic times on, rests atop a small rise on the eastern side of the wadi and south of the main fort we examined in Chapter 4. Although tumbled down, most of the blocks, columns, column capitals, entablature, and the dedicatory inscription survive more or less intact, fallen near their original position. This allows for a fairly complete picture of the ancient appearance of the building. J.G. Wilkinson, the British traveler, was so impressed by what he saw that he drew a detailed sketch of the tumbled remains on his visit in the early nineteenth century (Fig. 6.5). Access to the shrine was via a staircase on the north. Originally the temple itself faced west and had four monolithic columns made of local stone that graced its entrance. The inscription that once stood over the entrance above the columns indicates that the temple was erected early in the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian during the tenure of the governor Rammius Martialis (AD 117–119).

Nearer to and immediately south of the small bathhouse is a more ruinous temple dedicated to Isis. Isis was a goddess who epitomized the archetypical Egyptian wife and mother; she was extremely popular in Ptolemaic and Roman times and was often associated (syncretized) with a number of other deities. Worship of Isis would not be at all unusual in this desert environment. First discovered in the early twentieth century at the base of one of the ramps leading to a quarry in the mountains to the east, the identification was confirmed by the find of a beautiful four-line inscription precisely dated to January 28, AD 113, late in the reign of the emperor Trajan (AD 98–117). Fortunately, the inscription was studied and photographed by the British excavators prior to its theft by unknown persons using, to judge by the substantial tire tracks, a large truck in the winter of 1997/1998.

Fig. 6.5: The Serapis temple at Mons Porphyrites, drawn by J.G. Wilkinson (Ms. G. Wilkinson XLV. D169.V; Gardner Wilkinson papers from Calke Abbey, Bodleian Library, Oxford; courtesy of the National Trust).

Farthest from the main fort and on the west side of the wadi at the base of the impressive 1,700 meter-long ramp that led to the Lykabettus quarries (mentioned in Chapter 4) are the remnants of the temple of Isis Myrionomos (Isis of the Many Names) (Fig. 6.6). Although in better condition than the Isis temple located near the fort, the temple of Isis Myrionomos is not as well preserved as that of Serapis on the other side of the wadi and about 360 meters away. James Burton and J.G. Wilkinson first saw the inscription associated with the Isis Myrionomos temple and published what remained in 1832. The text dates to year 22 of the Roman emperor Hadrian (AD 117–138). A number of subsequent European visitors noted the inscription thereafter, but it has, unfortunately, since disappeared.

Fig. 6.6: Isis Myrionomos temple at Mons Porphyrites.

The erection of three temples in relatively close proximity to each other within about a twenty-five year period early in the second century AD probably indicates the intense level of activity at the quarries at that time. Surprisingly, British archaeologists working in one of the satellite quarry and village complexes, named the Bradford Quarry after the man who discovered it, north of the main fort in Wadi Ma‘mal and the temples we just described, found another inscription. Recovered inside a building that must be a shrine or temple, the text in Greek records in fascinating detail that a man named Gaius Cominius Leugas discovered the Mons Porphyrites quarries and the multi-colored varieties of ‘marble’ that could be found there. It also mentions that he dedicated a sanctuary to Pan and Serapis for the well-being of his children on July 23, AD 18, that is, early in the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius (AD 14–37). A large image of Pan/Min graces the stone standing left of the inscription. Pliny the Elder notes during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius that varieties of colored marbles were first discovered in the Eastern Desert. This newly found inscription would be some confirmation of Pliny's claim.

Lying south-southwest of Mons Porphyrites, the Mons Claudianus quarries also boast the remains of an extremely well-preserved temple (Fig. 6.7) located only a short distance from the large and impressive main fort and bath building that we discussed in Chapter 4. The temple comprises multiple rooms indicating, no doubt, that each was the preserve of one of the gods worshiped there. The rooms have niches and alcoves and with some walls preserved to heights of several meters complete with intact doors and windows. A once impressive staircase leads up to the complex from the south, from the direction of the main fort. Approached by multiple doors, excellently preserved niches, some with their mud wall plaster intact, column capitals and at least three inscriptions in Greek, this is arguably the best-preserved Roman-era religious structure in the entire Eastern Desert. The temple was sacred, as the main inscription tells us, to “Zeus Helios Great Serapis” and other gods who shared his temple. Thus, the building might be called a Roman ‘Pantheon’ in the desert. While there is no absolute proof of the date of this building, all the evidence suggests that it was erected during the reign of Trajan (AD 98–117). A nearby altar preserving a datable text suggests that was sometime in AD 108–109. J.G. Wilkinson records finding a terra-cotta head of Isis in the environs of the temple during his visit in the earlier part of the nineteenth century, which may suggest one of the many deities venerated here.

Fig. 6.7: The temple at Mons Claudianus, sacred to ‘Zeus Helios Great Serapis’ and other gods who shared his temple.

Our survey work in June 1993, March 1995, and August 1997 found, with the help of a Ma‘aza Bedouin friend, the ancient quarry and settlement at Umm Huyut. Located very near and just south of Mons Claudianus, the stone from Umm Huyut was similar in appearance (o that from Mons Claudianus, but was used, as we noted in Chapter 4, for smaller items than were produced at Mons Claudianus, The small settlement at Umm Huyut had rather nondescript and unimpressive buildings with the exception of one (Pl. 4.13). It stood atop a small rise, was nicely constructed with benches in the interior and approached by two staircases. The southeastern end of the structure preserved a square ‘niche.’ It was clearly the most important building in the settlement. Was it for administrative or religious purposes or could it have combined both functions? No inscription or other evidence provided any indication of what activities took place here in the early Roman period.

Southwest of Mons Claudianus and on the road that joined it to the Nile at Kaineopolis/Maxirnianopolis (modern Qena) is a small quarry located at a place called Fatireh al-Beida. Though long known to scholars, the site was only first carefully examined by our small survey team in August 1997. Amid the rather unremarkable remains of workers’ huts our small three-person survey noted a relatively impressive structure that appears to have had a cultic-religious function. Unfortunately, we found no accompanying inscription to indicate the deity that might have been worshiped here.

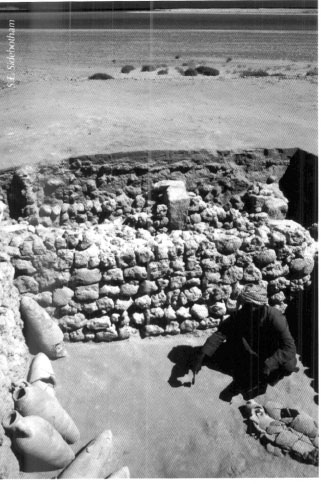

At the Mons Ophiates quarries, which lay generally south of those at Mons Claudianus, travelers earlier in the twentieth century reported seeing several inscriptions. One of these was clearly religious in content and suggested the presence of a shrine or temple. In fact, the building in question lies on the opposite side of the narrow wadi from what must have been the main administrative complex on the site, a walled enclosure containing a water cistern. Comprising two separate rooms connected originally by a doorway that was blocked sometime in antiquity, portions of this religious structure have been washed away over the centuries by floods passing through the adjacent wadi. Nevertheless, segments of the walls preserve impressive doors and windows with one corner wall still standing to a height of 5.4 meters. As we noted in Chapter 4, the lengthy inscription in Greek found here in the early twentieth century and first published in 1909, indicates that this edifice was erected late in the reign of the emperor Augustus (on May 26, AD 11) to the popular desert deity Pan/Min. In one of the rare examples where the names of architects are mentioned, this text, which also boasts an image of Pan/Min similar to that found on the Mons Porphyrites stone we noted above from the Bradford Quarry, records that Mersis and Soter, who are otherwise unknown, designed the building.

Sanctuaries at the Emerald Mining Settlements

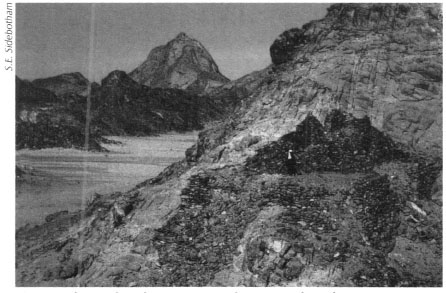

Deeper in the southern reaches of the Eastern Desert in a region the Romans knew as Mons Smaragdus, the only sources of beryl/emeralds to be found anywhere inside the Roman empire were exploited from at least the first century AD until the sixth. This area was also mined in Islamic and modern times. Hundreds if not thousands of shafts and pits honeycomb this region in which our surveys over the years have identified and studied nine principal mining settlements. While some of these preserve few edifices, several of the other ancient communities are Pompeii-like in the preservation of some buildings. Two of the largest and most impressive of these desert emerald mining communities are those in Wadi Sikait and the adjacent Wadi Nugrus. Wadi Sikait has, in fact, three settlements, which our project has named Sikait, Middle Sikait and North Sikait.

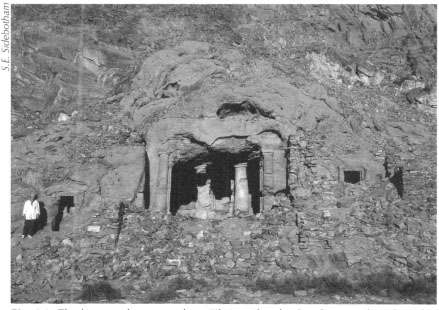

The French goldsmith and metallurgist Frédéric Cailliaud first discovered Sikait in 1816 and made a follow-up visit in 1817. He was in the employ of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, Egypt's ruler at me time, and had been commissioned to search for me lost emerald mines with a view to reopening them. Muhammad ‘Ali, however, never did reopen me area to extensive exploitation. The gemstones from the Sikait area were low grade and me mines were remote and difficult to access. There were also much higher quality and more easily accessible emeralds available from the mines in Columbia, South America. These various factors meant mat while some modern mining in the Sikait region has been undertaken, it was never extensive. Cailliaud made several impressive, but fanciful, drawings of two of the more alluring features at Sikait: the larger and smaller rock-cut temples (Pls. 6.4-6.5).

Sikait, the southernmost of the three settlements and by far the most impressive, preserves at least two identifiable rock-cut temples. Hewn directly into the sides of the mountain, the larger of the two has attracted the most attention from visitors over the past two centuries (Pl. 6.6 and Fig. 6.8). This large three-chambered temple at one time had an extensive-up to 4.5 meters long—three or four line inscription over the front entrance. Our survey found just a few letters of the beginning and end of the text in Greek. The rest may well lay fragmented and buried in the tumble beneath the entrance. It would be fascinating to uncover these broken stones to determine who carved this structure and to which deities it was dedicated. It is noteworthy that none of the earlier visitors to this temple mention the existence of these texts, which can only really be clearly seen at certain times of day and in particular types of light. Graffiti (carved) and dipinti (painted) from ancient to modern times emblazon the interior walls of the temple and include some from the nineteenth-century travelers. At the back in the third room on the altar we only recently noticed a large Christian cross carved over the badly worn remnants of a hieroglyphic text (Fig. 6.9).

Fig. 6.8: The large rock-cut temple at Sikait with side chambers north and south of the main entrance.

Fig. 6.9: Remains of hieroglyphs and a Christian cross found on the altar in the large rock-cut temple at Sikait.

This tantalizing evidence suggests use of the temple before the arrival of the Romans, perhaps during the Ptolemaic era, as well as by the later Christians. We hope to excavate here someday in conjunction with conservation and restoration measures to help preserve this wonderful antiquity for future generations. We have undertaken some consolidation work inside this building as well; we erected a support pillar in place of its ancient and now broken and fallen antecedent and have also shored up some of the walls (Pl. 6.7 and Fig. 6.10). In the course of excavating to install the temporary support we recovered a beautifully preserved tetradrachm (four-drachma coin) of the emperor Nero (AD 54–68) on the reverse of which is depicted the bust of the deified emperor Tiberius (AD 14–37). We also found a small, highly stylized statuette of Isis (Fig. 6.11) that is very similar in appearance to depictions of Isis in artwork from the ancient Kingdom of Meroë in what is today Sudan. Perhaps this latter discovery provides some evidence for one of the deities worshiped in this impressive shrine cut into the face of the mountain.

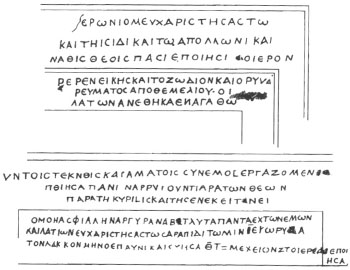

The second, smaller and less impressive rock-cut temple (Fig. 6.12) farther south in the same wadi as the larger structure preserves still today, and in its original position, portions of a lengthy inscription in Greek (Pl. 6.8 and Fig. 6.13). Various nineteenth-century visitors including Wilkinson and the Frenchman Nestor L'Hôte undertook the transcription of this text. That inscription, carved over the entrance of the small shrine, is extremely informative. It relates that the Roman emperor Gallienus (AD 260–268) dedicated the small rupsetral temple to Serapis, Isis of Senskis (the ancient name of Sikait), Apollo, and other gods on the 20th of February of an unknown year during his reign. It also mentions the excavation of a nearby well on June 15. Much of the text has disappeared and even fragments we saw lying on the ground in front of the temple on our first visit in 1991 have since been stolen. It is possible, indeed likely, that this temple was in use long before Gallienus and that his inscription is merely the latest period of recorded activity at this petite shrine. During our winter 2002/2003 field season we erected three pillars made of pieces of locally available stone at the entrance of this structure as temporary support to prevent collapse until we can conduct more careful consolidation and conservation (Fig. 6.14). There are other rock-cut structures at Sikait as well as several additional well-preserved and impressive freestanding edifices that may also have been temples, but we do not know this for certain.

Fig. 6.10: Large rock-cut temple at Sikait. Temporary conservation /consolidation measure to shore up the sagging interior roof. The column was erected in the position of the original one.

Fig. 6.11: Small metal stylized figurine of Isis from the large rock-cut temple at Sikait.

Fig. 6.12: Small rock-cut temple at Sikait.

Fig. 6.13: Inscription in Greek over the entrance of the small rock-cut temple at Sikait, drawn by N. L’Hôte O. Letronne ND, Recueil des inscriptions grecques et latines de I’Égyple. Atlas. Paris: Imprimerie royale, PL. XVI).

Fig. 6.14: Small rock-cut templeat Sikaiafter consolidation.

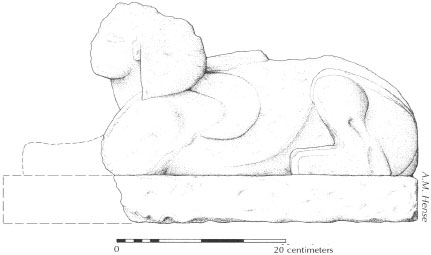

In a large wadi southwest of Sikait is the ancient emerald and beryl mining settlement of Nugrus, Here are the remains of several hundred structures approximately twenty of which survive in spectacular condition. One building, part way up a hill southeast of the main site, is most certainly a temple (Figs. 6.15-6.16). Approached by a long and elaborate set of stairs, the multi-roomed shrine rests atop a well-built artificial platform. The thick walls are built of careful1y stacked locally quarried stone. Several doors with their lintels, as well as niches survive in excellent condition. Amid the ruins our survey recovered the lower portion of a seated cult statue. Only the legs and throne, the sides of which are much worn, but seem to preserve hieroglyphs, survive to a height of less than twenty-five centimeters (Fig. 6.17). Yet, we could not establish which deity was honored in this finely wrought building.

Fig 6.15: Nugrus, part of the temple on the east side of the Roman-era beryl/emerald mining community.

Fig. 6.16: The temple at the Roman-era settlement at Nugrus.

At Ka‘b Marfu‘, in the emerald mining district of the Eastern Desert, an impressive structure built halfway up the side of a mountain immediately draws the visitor's attention. Nestled atop a massive four-meter high artificial platform and approached by an impressive flight of stairs from a major cluster of buildings in the wadi below, this structure must have been a temple (Figs. 6.18-6.19). Doors provided access from two sides, a main one from the south and a smaller one from the east. Our survey found no inscription indicating the purpose of this noteworthy edifice, but its prominence and elevation well above the rest of the settlement strongly suggests that it was for religious activities.

Fig. 6.17: Statue fragment from the temple at Nugrus

Sanctuary at a Settlement of Unknown Function

Lying thirty to thirty-five kilometers southwest of the Red Sea port of Quseir are the extensive remains at Bir Kareim. Long believed to have been one of the sources of potable water to the Red Sea port of Quseir al-Qadim (ancient Myos Hormos), brief and incomplete surveys were conducted here in the winters of 1978 and 1980 by a team from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, the same group that excavated Quseir al-Qadim. They believed that Bir Kareirn was also a Roman gold mining settlement. Yet, a brief return visit to Bir Kareirn by our survey team in August 1998 located none of the telltale gold grinding stones that are ubiquitous at other Ptolemaic and Roman gold mining settlements in the Eastern Desert. Thus, until we undertake more detailed work here, we cannot be certain of the purpose of this sizeable and apparently early Roman settlement. In any case one of the more prominent edifices on the site is a temple or rather a structure that closely resembles in plan a temple; it is built of a purple-red stone very different from that used in the other buildings in the settlement. It has two courts and a tripartite cella (enclosed cult area) near the rear wall. This architectural arrangement would suggest that the building had a religious function. We do not know to whom the putative temple was dedicated or who erected it. The structure sits at the base of a prominent mountain. In 1980 the survey team found a fragment of a pictorial relief with part of a uraeus (cobra) decoration on it in the vicinity of the building. This may or may not have any bearing on the identification of the edifice as a temple.

Fig. 6.18: Drawing of the temple at the Roman-era settlement at Ka‘b Marfu‘.

Fig. 6.19: The temple at the Roman-era settlement at Ka‘b Marfu‘

Temples and cult centers in the Eastern Desert were not confined only to quarries and mines. Recent French excavations of Roman-era praesidia along the road joining the ancient Red Sea port of Myos Hormos to the Nile at Coptos (Quft) noted that each seems to have had its own protective patron deity. While worship of Pan is evident from the many small Paneia scattered throughout the desert, especially along the various trans-desert routes, he was also honored in at least one of the desert praesidia. Ostraca indicate that other apotropaic deities venerated at the forts included Apollo, Athena, the Dioscuri (the twins Castor and Polydeuces/Pollux), Serapis, and Philotera, the deified sister of Ptolemy II Philadelphus 285–246 BC). Yet, it is very rare to be able to identify a particular area inside any of these forts that was set aside specifically for the worship of these deities.

Though portions of the Red Sea ports of Myos Hormos and Marsa Nakari (perhaps to be associated with the ancient Nechesia and which lies about 150 kilometers south of Myos Hormos) have been excavated, no recognizably religious structures have been found. Archaeologists from the University of Southampton excavating at Myos Hormos in 1999–2003 believe they may have unearthed a temple or synagogue, though they are very tentative about this identification.

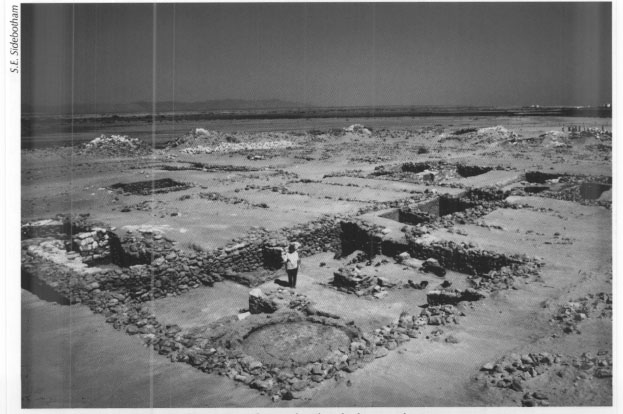

At the Red Sea port of Berenike (which lies about three hundred kilometers south of Myos Hormos and approximately 150 kilometers south of Marsa Nakari), on the other hand, we have excavated several temples, sanctuaries, and a church. We have also found inscriptions indicating the existence of other cults whose buildings now lie silently somewhere amid the buried ruins of the city.

The best-known temple at Berenike is undoubtedly that dedicated to Serapis and other deities (Figs. 6.20-6.21); it dominates the highest part of the city and its remains were somewhat visible as early as 1818 when Giovanni Belzoni first rediscovered the site. In fact, he made a drawing of what he saw at the time. Built for the most part of brilliant white locally obtainable gypsum, the temple blocks that compose the walls were joined together with clamps made of wood. This structure has fared badly over the centuries. It was the focal point of attention of many of the nineteenth century visitors who spent time ‘clearing’ the building and recovering inscriptions and pieces of statuary that once graced the structure's interior. Even then, the inscriptions, mainly in hieroglyphs, that covered the walls were in extremely fragile condition. They were so delicate that one visitor passing his hand over the walls noted pieces of the inscriptions falling off. The ancient texts that emblazoned the interior walls of the temple are mainly Roman in date, first and second century AD, though there are some from the Ptolemaic period reported to have come from the temple interior. We have to assume that this temple, or a predecessor, existed here after the foundation of Berenike by Ptolemy II Philadelphus in about 275 BC. We do not know when it ceased to be used as a religious sanctuary. More has been written about this Serapis temple prior to our excavations than any other structure at Berenike.

Between 1994 and 2001 our project uncovered several other buildings having religious functions. In addition, dedicatory inscriptions surviving on stone demonstrate that men and women, both civilian and military, paid homage to a number of deities worshiped in the port. We found three inscriptions inside the same building during the 2001 season at Berenike while excavating in the late Roman quarter. Here were located multistoried edifices that served both a commercial and residential function. A wealthy woman named Philotera honored Zeus on two inscribed stone slabs carved during Nero's reign (AD 54–68) (Pl. 6.9), while a man whose name is lost to US, but who was an interpreter and secretary and the son of Pap iris, made a dedication to Isis during the reign of the emperor Trajan (AD 98–117).

Fig 6.20: The Serapis temple at Berenike.

Fig. 6.21: The Serapis temple at Berenike.

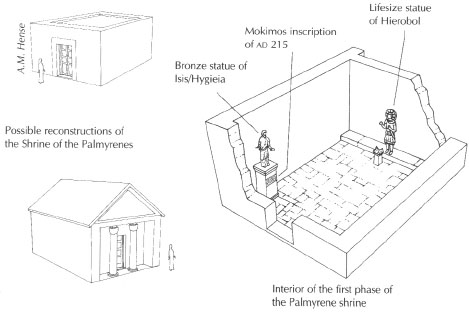

A diminutive shrine, in a small narrow structure built of coral heads and cut blocks of gypsum and anhydrite, lay west and down the hill from the Serapis temple. Though small, it contained the most spectacular finds found at any time during our excavations (Fig. 6.22). We collected fragments that comprised about sixty percent of a nearly life-sized bronze statue of a female holding either a snake or a cornucopia (Pl. 6.10). The statue originally rested on an inscribed stone base dedicated by a Roman auxiliary soldier from the Syrian Desert caravan city of Palmyra (Fig. 6.23). Serving as an archer in the Roman army stationed at Berenike, this man, whose name was Marcus Aurelius Mokirnos son of Abdaeus, offered the inscription and statue to the emperor Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna as part of the Roman imperial cult. Worship of Roman monarchs and their relatives was especially popular in the Eastern portions of the Roman world where deification of rulers had a long tradition, especially in Egypt. Mokirnos’ precisely dated offering of September 8, AD 215 was one of a number of important religious objects found in this relatively tiny and compact cult center.

Fig. 6.22: Shrine of the Palmyrenes at Berenike.

Fig. 6.23: Reconstruction of statue base, inscription, and statue fragment from the shrine of the Palmyrenes at Berenike.

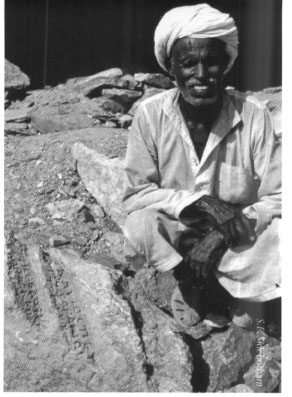

Another inscription, found in the same shrine by our camp guard after a particularly heavy rain washed it from the surrounding area into the same trench as the Mokimos dedication, proved even more exciting (Figs. 6.24). It was a bilingual text carved in both Palmyrene and in Greek with the Greek text being longer and more informative. It records several Roman soldiers plus the Roman governor of Berenike by name and rank and the dedication of a statue of the Palmyrene god Yarhibol/Hierobol. Most fascinating is the mention of Berichei, the sculptor who crafted the image of the god. His name suggests that he, too, was probably from Palmyra. Though undated, the names on the inscription indicate that it was carved sometime between about AD 180 and 212.

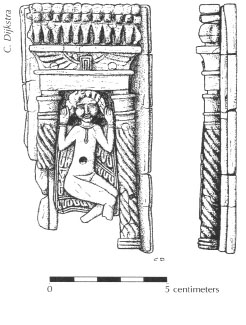

Our excavations in the same trench that produced the Mokimos and Berichei inscriptions also unearthed a large monolithic block in its original position with two carved indentations for fixing a standing statue into it. We also found fragments of lead, which would have been used to seal the statue to the base. Unfortunately, aside from a single bronze hand (Fig. 6.25), nothing else of Berichei's masterpiece survives. Other evidence of religious activity included a small stone altar with burning on the top, cultic bowls made of terra cotta, and about one hundred bowls made of wood, a small statue of a sphinx (Figs. 6.26-6.27), which had been rebuilt into one of the later walls of the shrine, and a small stone head of the Egyptian deity Harpocrates, Clearly, this shrine was extremely active in the late second to early third centuries AD and later. It also suggests that Palrnyrene troops helped to patrol the desert road joining Berenike to the Nile emporium of Coptos, where interestingly, another inscription dated to AD 216 also mentions a Palmyrene mounted unit stationed there. That these men had ample funds to make such elaborate dedications, something they probably could not have accomplished on their military pay alone, might indicate that they made extra income participating at some level in the lucrative commerce that passed through the port.

Pl. 6.4: Drawing by F. Cailliaud of the larger rock-cut temple at Sikait. From F. Cailliaud, Voyage à l'oasis Thèbes et dans les déserts situés à l‘orient et I'occident de la Thébeïde (Paris: 1821).

Fig. 6.5: Drawing by F. Cailliaud of the larger rock-cut temple at Sikait. From F. Cailliaud, Voyage à l'ossis Thèbes et dans les déserts situés à 'orient et I'occident de la Thébeïde (Paris: 1821).

Pl. 6.6: The large rock-cut temple at the Roman beryl/emerald mining community at Sikait.

Pl. 6.7: Interior of the large rock-cut temple at Sikait with broken column.

Pl. 6.8: Fragment of the inscription in Greek over the entrance of the small rock-cut temple at Sikait.

Pl. 6.9: Berenike, inscribed stone slab carved during Nero's reign (AD 54–68). Dedication by Philotera to Zeus found in the courtyard of a house in the late Roman residential/commercial quarter.

Pl. 6.10: Bronze statue originally set on an inscribed stone base dedicated by a Roman auxiliary soldier from the Syrian Desert caravan city of Palmyra. Scale = fifty centimeters.

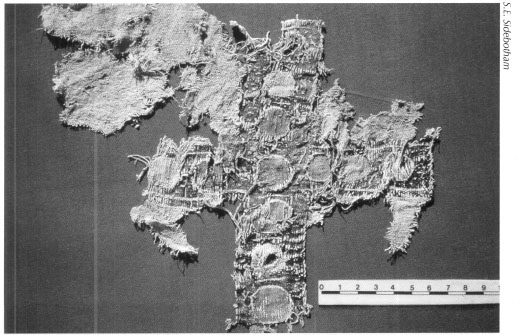

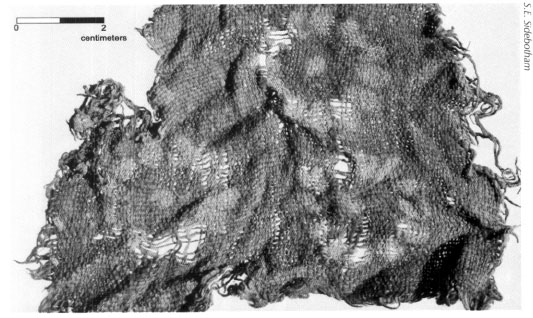

Pl. 6.11: Textile cross found in the principia/church at Abu Sha'r. Scale = ten centimeters.

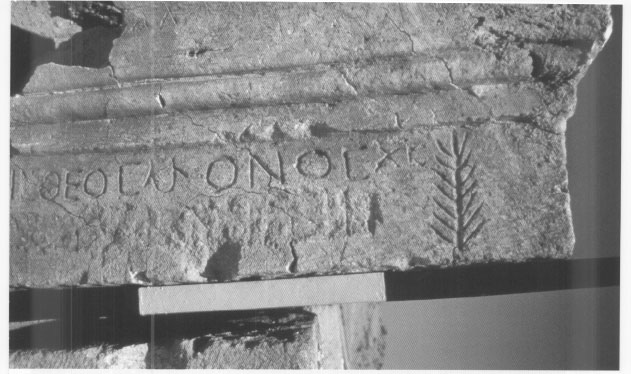

Pl. 6.12: Inscription from the north gate of the fort at Abu Sha'r, carved in Greek, which reads: “There is one God only, Christ.” Each black-and-white increment on the scale = twenty centimeters.

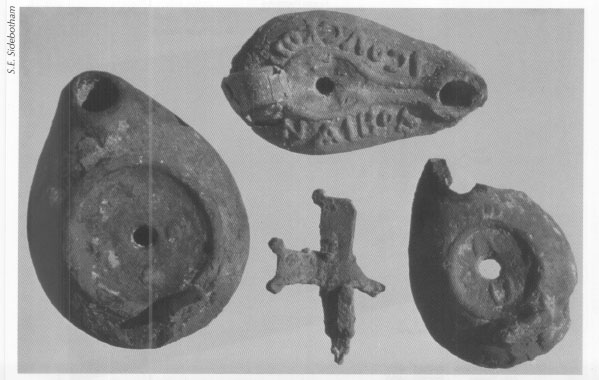

Pl. 6.13: Oil lamps with Christian symbols and a bronze cross-shaped handle from a lamp found in the large ecclesiastical complex at Berenike.

Pl. 7.1: Remains of Myos Hormos.

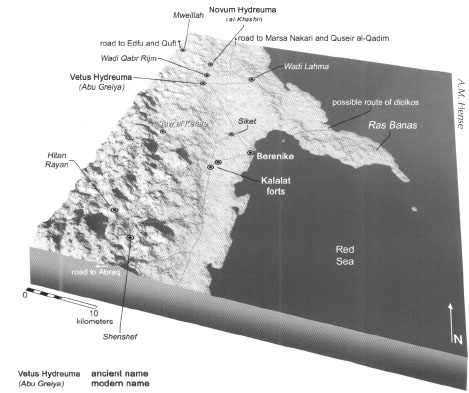

Pl. 7.2: Berenike and surroundings.

Pl. 7.3: The Red Sea port of Myos Hormos.

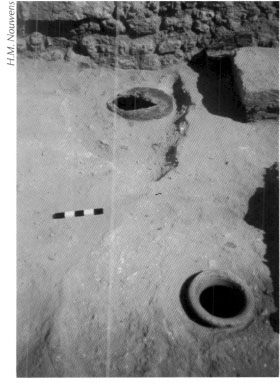

Pl. 7.4: Berenike, large round-bottomed clay jars made in india. Scale=twenty centimeters.

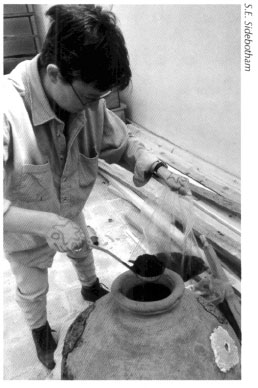

Pl. 7.5: Peppercorns found in Indian-made jar embedded in the courtyard floor of the Ser-apis Temple at Berenike.

Pl. 7.6: Warehouse in Berenike with amphorae from about AD 400

Pl. 7.7: Fifth century AD cotton resist-dyed Indian textile found at Berenike. Very similar textiles were excavated at two sites along the Silk Road in western China. Each black-and-white increment on the scale = two centimeters.

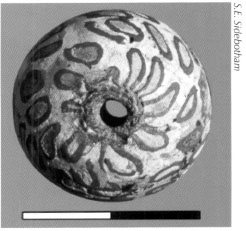

Pl. 7.8: Bead from jatim, Eastern Java found at Berenike. Each black-and-white increment on the scale = one centimeter.

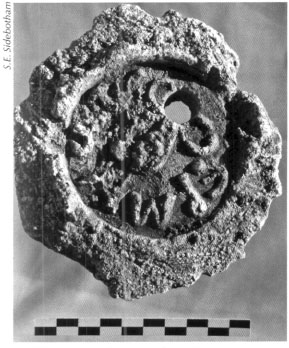

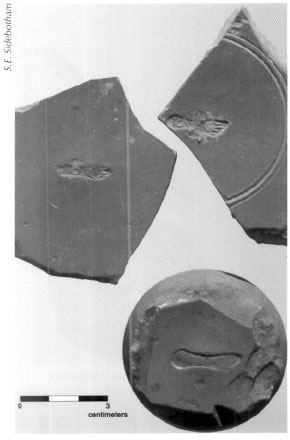

Pl. 7.9: Stamped plaster amphora stopper found at Uerenike. Scale = ten centimeters.

Pl. 7.10: Fragments of terra sigillata bowls with makers Scale = five centimeters.

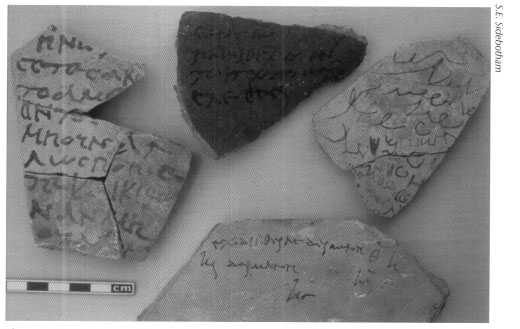

Pl. 7.11: First century AD Tamil-Brahmi graffito carved on a Roman amphora fragment. Scale = ten centimeters.

Pl. 7.12: Ostraca found at Berenike in the early Roman trash dump. Each black and white increment = one centimeter.

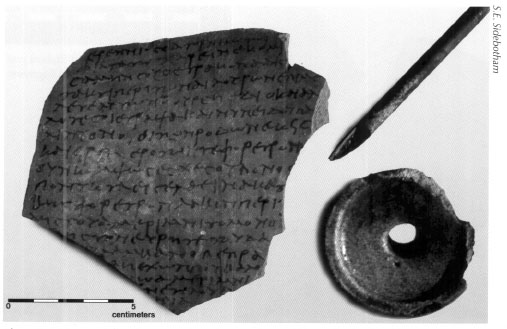

Pl. 7.13: Ostracon, inkwell, and reed writing pen found at Berenike. Scale = five centimeters.

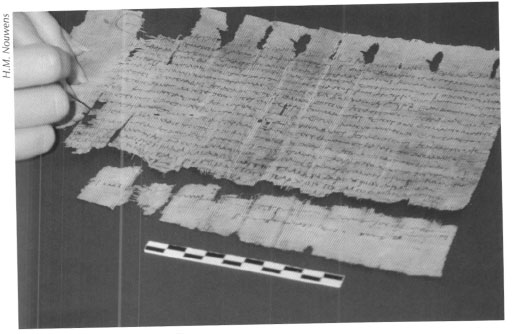

Pl. 7.14: Berenike, papyrus: bill of sale for a white male donkey and a packsaddle for 160 drachmas, dating to 26 July, AD 60 (during the reign of Nero AD 54–68). Scale = ten centimeters.

Pl. 7.15: Eastern Desert ware.

Pl. 8.1: Berenike, skeleton missing its head deposited at an unknown date in the abandoned Ptolemaic industrial area. Scale = one meter.

Pl. 8.2: Grave in the large cemetery at Taw al-Kefare, used in the fifth century AD and later.

Pl. 9.1: Large circular ore-grinding facilities at the site of Daghbag.

Pl. 9.2: Large circular ore-grinding facilities at the site of Daghbag. (Detail of Fig. 9.1).

Pl. 10.1: Reconstruction of the buildings at the late Roman/early Byzantine period (fourth to sixth centuries AD) gold mining settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir.

Pl. 10.2: Well-preserved structure (called ‘Three Windows’) at the Roman-era mining community at Sikait.

Pl. 10.3: Barracks blocks in the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r.

Pl. 10.4: View of interior of late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r looking northwest.

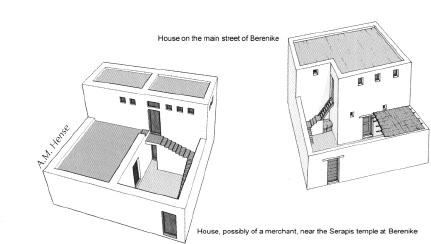

Pl. 10.5: Reconstruction of two houses at Berenike from the late Roman (late fourth-fifth century AD) commercial-residential quarter.

Pl. 10.6: Reconstruction of a multiple-storied house near the Serapis temple at Berenike.

Fig. 6.24: Bedouin excavator holding a Greek-Palmyrene bi lingual inscription (left). The Greek-Palmyrene bilingual inscription containing a dedication to the Palmyrene god Hierobol/Yarhibol. Scale = ten centimeters (right).

Fig. 6.25: Statue base with two holes in it for the feet of a bronze statue (likely of Yarhibol). Scale = fifty centimeters.

Fig. 6.26: Sphinx statue of local gypsum rock from the shrine of the Palmyrenes.

Fig. 6.27: Sphinx statue in situ in the Palmyrene shrine.

Elsewhere at Berenike our excavations recovered a statuette of Aphrodite sculpted in local stone from the early Roman trash dump and a nicely carved Aphrodite wringing her hair decorating the top of a wooden jewelry box (Fig. 6.28) from about AD 400. Both indicate that deity's popularity at the port. We also recovered a small representation of Bes, a minor Egyptian god associated with love, marriage, and the warding off of evil.

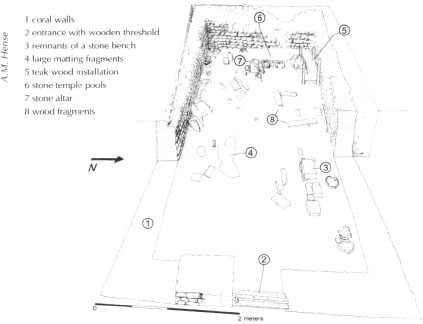

Only about eighty meters north of the Serapis temple our excavations uncovered another small, perhaps vaulted, cult center with a single narrow entrance at its eastern end. Unlike the sanctuary with the inscriptions and remains of the two bronze statues, this one had a short life at the turn of the fourth and fifth centuries AD. During two phases this shrine honored some deity whose identity remains uncertain; though this may have been a mystery cult (Figs. 6.29-6.30). Mystery cults in the Greco-Roman world were those with limited membership and special initiation rites. Often times, the initiation process was a closely guarded secret and one the inductees swore never to reveal. Isis was possibly worshiped here as she was quite popular elsewhere in the Eastern Desert and, as noted above, we recovered a second-century inscription in another trench at Berenike dedicated to her. The small enclosure contained a columnar shaped altar at the back (western) end, the top of which had been heavily burned. This altar had been used during both phases of the life of the building. Adjacent to it were four stone-carved temple-pools, items commonly found throughout the pharaonic period and later in many sanctuaries throughout Egypt (Fig. 6.31). We also recovered an intact ostrich egg painted in hues of red, a small bronze statuette, a number of terra-cotta oil lamps, and about fifty amphora toes which had been reused as torches; clearly artificial lighting was necessary. Inside and parallel to the long walls of the building were two benches. In the latest phase, reused stones served as bench tops. One of these, unfortunately very fragmentary, was a relief depicting two figures. One figure to the right stood on an elevated dais and the other stood at a lower level to the left. We do not know if this relief was an original part of this building or if it had been recycled from some other part of town. Nor do we know what to make of the scene. Could it be that the figure on the dais was a deity and that below and to our left was a priest or devotee, or could the scene be secular in nature?

Fig. 6.28: Decorated wooden panel depicting Aphrodite. Likely the lid of a jewelry box

Fig. 6.29: Small sanctuary north of the Serapis temple at Berenike, possibly used for a mystery cult. Scale = fifty centimeters.

Fig. 6.30: Drawing of small sanctuary north of the Serapis temple at Berenike, possibly used for a mystery cult.

Fig. 6.31: Stone altar, ostrich egg, and four temple pools in situ in the small mystery cult sanctuary at Berenike. Scale = twenty centimeters.

Christian Remains in the Eastern Desert

Ancient written sources, especially those of the early Christian church fathers, recount that many people from all walks of life, both men and women, fled to the desert areas to escape persecution or to worship without the quotidian distractions encountered while living in crowded villages in the Nile Valley. This process of departing the cultivated areas adjacent to the river for the desert was known as anachorsis and it was practiced not only because of religious motivation, but also by those seeking to evade taxes, escape the long arm of the law, and for a host of other reasons. In fact, the desert was long the haunt of bandits who preyed on those passing along the roads that threaded through the desiccated landscape; the bolder among them occasionally also attacked villages closer to the Nile.

Several excellent examples of monasteries in the Eastern Desert, established in the third or fourth centuries and which continue to operate today, can be found in the northern areas. The flourishing monasteries of St. Antony and St. Paul lay not far from one another. Yet little can now be seen of ancient date at these sites. Several churches from the later fourth to fifth centuries survive in the region, however, as do other material remains attesting the presence of Christian desert dwellers.

The late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r, which we discussed in Chapter 3 in conjunction with the Via Nova Hadriana, had, after its abandonment by the Roman military sometime in the late fourth or early fifth century, been reoccupied by a group of Christian squatters. Clearly less numerous than the earlier Roman garrison, as can be seen from their non-use of many of the buildings inside the fort's enceinte, they confined most of their activity to the large former headquarters which they converted into a church. Our survey and excavations at Abu Sha'r between 1987 and 1993 noted large crosses carved on some of the white gypsum stones used to construct the building. In 1991 we also recovered a beautiful polychrome cloth-embroidered Christian cross (Pl. 6.11) that must have been part of an altar decoration or monk's or priest's vestment.

Another spectacular find was an almost complete papyrus, which we discovered rolled up and placed adjacent to one of the piers that supported the roof of the headquarters/church. This twenty-seven-line-long Greek text, probably written in the fifth century, is nearly complete and refers to Slamo, the wife of a man named John, and his daughter Sarah. The papyrus had a note on the front requesting delivery to “Father John from Apollonios,” which implies that the letter itself was written by a man named Apollonios to Abba (father) John. After the usual formulaic greetings Apollonios writes, “The Lord testifies for me that I was deeply grieved about the capture of your city, and again we heard that the Lord God had saved you and all your dependents.” Needless to say, we would very much like to know the details of this part of the epistle, but we can only hypothesize. John's wife's name, Slamo, which is Semitic, may point to some place in the Sinai as being the city in question. Were John and his family here at Abu Sha'r as refugees after the capture of their city or were they visiting pilgrims who only received news of the fate of their city while at Abu Sha'r?

Also immediately in front of the apse of the military headquarters/church we recovered part of an adult human leg bone wrapped in cloth. We believe this was the remains of a venerated individual, perhaps a local saint or martyr, some of whose bones had been placed here. Worship of saints and martyrs was particularly in vogue among the early Coptic Christians of Egypt and the bones we found may well be those of a holy man whose name has long since been lost to us. To reinforce our interpretation of this building being converted to a martyr shrine (a martyrium), we found the shoulder of an amphora in the extra-mural baths at Abu Sha'r that had mart[—?] written on it in Greek. These are the first letters of the words martyrium, martyr, and their cognates.

At the time these Christians were using the fort at Abu Sha'r as a place of refuge, they were entering and exiting mainly via the surviving north gate; the principal western gate used earlier by the military had apparently collapsed and been abandoned by the period of Christian use. The arch, part of the fort wall and even portions of the crenellated battlements that had originally stood over the north gate, had fallen forward and away from the fort; we excavated and reassembled these in summer 1992. In so doing, we found cut into some of the blocks of the toppled arch two inscriptions carved in Greek, clearly Christian religious in content. One merely noted, “There is one God only, Christ,” accompanied by a palm branch, a typical symbol of victory in both pagan and early Christian art (Pl. 6.12). The second text was far longer and called upon the Lord God, ‘our’ fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, all the saints and Mary ‘Mother of God’ to have mercy upon those who carved the inscription, but whose names do not appear. Both texts were likely written in the fifth century. The north gate area itself preserved numerous graffiti from the Christian period of the fort's use as the appearance of numerous crosses indicates.

West of Abu Sha‘r in the quarry area of Mons Porphyrites various expeditions over the years, including ours, found ample evidence that Christians in the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries had lived and died in this barren wasteland. Christian cemeteries have been found in the region with a particularly noteworthy one located not far from the small village toward the top of the mountain near the so-called Lykabettus quarries. In 1989 our survey recovered the remains of a tombstone preserving a text in Greek of the deceased. His name was John and he originally hailed from the Nile city of Herrnopolis; there are several cities of that name so we cannot be certain which one was John's home. Nor can we be certain that John was here voluntarily. While it is likely he was one of those fleeing the Nile Valley for the solitude of the desert, it is also possible that he was here under duress as forced labor working the quarries, a situation which some ancient written sources indicate was a fairly common punishment for criminals or political undesirables.

In Wadi Nagat, a small offshoot of Wadi Qattar, are remains of a building; there Wilkinson, Murray, and Tregenza had noted a Christian inscription indicating the presence of an anchorite community. Murray says he removed the inscription for safe-keeping to Luxor in 1949.

The other major Christian building in the Eastern Desert is the large ecclesiastical complex we excavated at Berenike between 1996 and 2001 (Figs. 6.32-6.33). When we first began excavations in this structure, located in the extreme eastern part of Berenike, we did not recognize that it was Christian, only that it was late Roman. However, after the recovery of a large bronze cross, that was probably part of a decorated handle of an oil lamp used for illumination that we found nearby, as well as three other terra-cotta oil lamps, two of which bore crosses and the third an aphorism in the Coptic language that translates “Jesus, forgive me,” (Pl. 6.13) we were fairly certain that the large structure was, indeed, a church. The orientation of the building toward the southeast also fit with what we know about early Christian churches in Egypt. In size, the Berenike church dwarfed any of the ‘pagan’ temples we uncovered in the city. Yet, the near contemporary use of the church with the two smaller pagan cult centers noted above suggests that various religions, including Christianity, coexisted in some degree of harmony at the entrepôt in the late Roman period.

Fig. 6.32: Berenike: large ecclesiastical complex. Scale -one meter.

Fig 6.33: Reconstruction of the large ecclesiastical complex at Berenike.

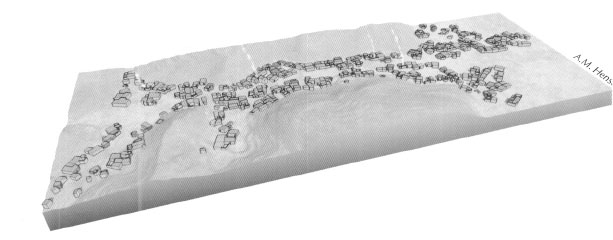

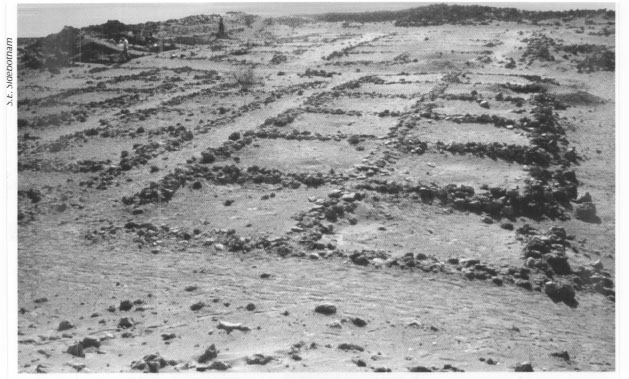

Other remains of possible Christian hermit communities can be found throughout the Eastern Desert. During our surveys we have located over a dozen villages ranging in size from 47 to 190 structures and more. These settlements were located off the main roads, but usually not more than a day's walk to some other settlement or from the Red Sea coast. Clearly they were not situated to attract a great deal of attention. Mainly circular, oval to roughly rectilinear in plan and comprising usually one room, but also occasionally two, three or even, rarely, up to four rooms, the buildings found in these settlements have a number of features in common. The walls of all structures are usually not much higher than a meter or so and invariably have wall faces comprising larger cobbles or small boulders with the fill between consisting of smaller pebbles. Upper wall portions must have been made of mats, animal hides, or tent-like structures, which have left no traces. Some of these rooms have raised benches or mastabas inside for sleeping and small alcoves, storage facilities, patios, or areas that seem to have been animal pens.

Pottery found at these sites was invariably made in the late fourth to the sixth or seventh centuries AD. Most of the shards are from amphoras (storage and shipment containers) with a significant proportion imported from southern Asia Minor or Cyprus. Palladius, a Christian writer from the fifth century, reports that Cilician amphoras were used in these desert settlements and that is precisely one of the places, on the south coast of Turkey, where the amphoras we have found in such profusion at these enigmatic Eastern Desert sites were made. A number of the necks and shoulders of these amphoras bear dipinti (writing in ink) in red paint, but these are, for the most part, completely illegible; they must indicate the volume or nature of the contents of the jars. At several of these desert sites our surveys noticed larger buildings, which may have served as communal gathering spots. For example, the ancient community, which we call Umm Howeitat al-Bahari, has one larger building with an entrance on the south; it preserves an apse-like structure at its eastern end and a bench at its western. Could this have been a small chapel or church? We do not know for certain. If it was, it could only have accommodated a small number of people at one time from this relatively large settlement.

Little evidence has come to light in the Eastern Desert for the presence of Jews though we did find a graffito in Hebrew from the late Roman period at Berenike plus some ostraca written in Greek that refer to ‘Jewish’ delicacies, an otherwise unidentifiable food no doubt.

As mentioned before, recent British excavations at the Red Sea port of Myos Hormos have found a strucrure that might have been a temple Or, more likely a synagogue. Whatever function it served, it seems to have fallen out of use early in the life of the port.

There is also, of course, evidence for Muslim presence in the Eastern Desert. We have found early Islamic pottery at some of the praesidia and there was a small mosque inside one of the praesidia on the road linking Myos Hormos to Quft. Undoubtedly associated with hajjis traveling between the Nile Valley and Mecca by sea between Quseir and Jeddah, these remains lay outside our period of interest. There was a concerted Muslim presence at Quseir al-Qadim from the late eleventh/early twelfth to the fifteenth centuries. Thereafter the port was abandoned and the new city of Quseir about eight kilometers to the south replaced it. There are also Islamic remains at ‘Aidhab (Abu Ramada), about 250 kilometers south of Berenike, that facilitated the movement of hajjis by sea between Egypt and the Arabian port of Jeddah.

Continued exploration of the Eastern Desert in the future should reveal more about the religious activities of the people who passed through or called the region home even if for only brief periods of time.