Gold Mines in the Eastern Desert

The most important and consistently sought-after natural resource available in the Eastern Desert throughout antiquity was gold (Fig.9.1). We have archaeological and written evidence from at least the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods (2920-2152 BC) that expeditions both large and small ventured forth into the arid regions between the Nile and the Red Sea in search of this valuable metal. There are frequent references, especially in inscriptions associated with the king and his courtiers, throughout the pharaonic period to valuable objects as well as the precious artifacts themselves wrought from or decorated with gold including various types of jewelry, altars, chariots, columns, drinking vessels, death masks, thrones, statues, doors, and even whips. These items indirectly attest the acquisition of gold from regions of the Eastern Desert. The late Predynastic town at Nagada, near the mouth of the Wadi Hammamat at the edge of the Eastern Desert, was known as Nubt (‘Gold Town’), perhaps indicating that it grew rich from the gold trade. Interest in and exploitation of gold mines in the Eastern Desert accelerated during the Middle (2040-1640 BC) and New (1550-1070 BC) Kingdoms.

New Kingdom private tombs, such as that of mayor Sobekhotep, sometimes include depictions of Nubians bringing gold as tribute. During the New Kingdom, gold was also obtained from Syria-Palestine by way of tribute, despite the fact that Egypt was already much richer in gold than the Levantine city-states. The Egyptians’ wealth in gold made them the envy of their neighbors in the Near East. This jealousy is frequently expressed in the so-called Amarna letters, an important cache of documents discovered in 1887 at the city of Tell al-Amarna (ancient Akhetaten) in Middle Egypt that was founded by pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1335 BC). Almost all of the Amarna letters preserve diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and either the great powers in western Asia, such as Babylonia and Assyria, or the vassal states of Syria and Palestine. In one letter from Tushratta of Mitanni we read, “May my brother send me in very great quantities gold that has not been worked, and may my brother send me much more gold than he did to my father. In my brother's country gold is as plentiful as dirt.…”

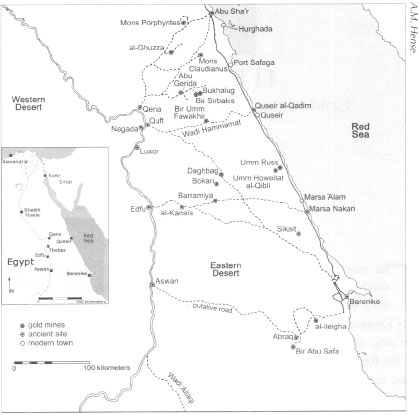

Fig.9.1: Map showing locations of goldmines in the Eastern Desert mentioned in this chapter.

Gold mining continued in the Late Period (712-332 BC) and in Ptolemaic and Roman times (late fourth century BC-sixth century AD). In some instances mines first opened in the pharaonic era continued to be exploited in later times. In other cases new mines were opened where none had been before. The quest for gold continues to lure large joint foreign-Egyptian ventures today. It would be a fascinating exercise to estimate the quantities of gold extracted from the region throughout history.

The importance attached to the success of the gold mining operations and the potential wealth derived from them necessitated that the government strictly control them throughout Egypt's history. Gold paid for elaborate royal building projects and allowed various Egyptian regimes over the millennia to maintain the military forces and the diplomatic leverage necessary to advance Egypt's political agendas both domestically as well as beyond her borders. In the pharaonic period Egypt's major foreign areas of interest lay along the Nile south of her traditional frontier in Nubia and on the Levantine coast of the Mediterranean, and in Ptolemaic times those spheres expanded to include more southerly areas of the African coast of the Red Sea, Cyprus, parts of southern Asia Minor, and some of the Aegean islands. In the Roman period, of course, Egypt was only one province in a large multi-cultural empire spanning parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa that, at its height, stretched from Scotland to the Persian Gulf and from the eastern shores of the Black Sea to Morocco. While Egypt was an important source of gold for the Romans, other regions of their empire including Wales, Spain, and Dacia (modern Romania) also supplied the imperial government with this precious metal.

The most productive gold-bearing areas in Egypt were those immediately southwest of the modern Red Sea city of Hurghada and reaching to the region west and southwest of Berenike and southeast of Aswan into Wadi ‘Allaqi. Some expeditions went even farther afield. Not content with exploitation of Egypt's mines, at several points in her long history, expeditions were mounted into regions well to the south of Egypt's traditional boundaries into areas of the Eastern Desert of what is today northern Sudan. In pharaonic times and later the gold-bearing areas of Egypt and Sudan were divided into three major zones which the Egyptians called, from north to south, the Land of Coptos, the Land of Wawat and the Land of Kush. These stretched between approximately 27° and 18° North latitude and encompassed large swaths of the Eastern Desert. Inscriptions from the time of the Twelfth Dynasty (Middle Kingdom) pharaoh Senwosret III (1878-1841 BC) refer to gold mining expeditions dispatched to regions south of Coptos and inscriptions emblazoned on the temple of Medinet Habu from the reign of Ramesses III (1194-1163 BC) of the Twentieth Dynasty also refer to gold derived from various areas of the Eastern Desert.

This vast realm of the Eastern Desert provided gold to the pharaohs, but interestingly during Roman times the regions exploited seem to have been far more circumscribed and confined primarily to the central and southern areas of Egypt's Eastern Desert. Numerous mines and associated settlements with their ubiquitous grinding stones can still be seen from different periods of Egypt's long history of gold mining. Surprisingly, however, only a small handful of mines has ever been studied through detailed surface surveying and mapping, and only one has been partially excavated and the results published. Numerically, the ancient gold mines of the Eastern Desert far outnumber the hard and soft stone quarries we discussed in Chapter 4. The transport problems surrounding the shipment of stone products, particularly the large columns, basins, and other architectural elements sought in the Roman period from these quarries, would not have existed in the gold mines as the ore or even in some instances the refined product could be removed relatively easily by pack animals such as donkeys and camels. Unlike the stone transported from the quarries, however, security considerations would have been paramount for those convoys hauling gold from the mines to the Nile Valley.

The Turin Papyrus, discussed in Chapter 4, depicts a map drawn in Egypt's New Kingdom period during the reign of the Twentieth Dynasty pharaoh Ramesses IV (1163-1156 BC). The map shows a portion of the Eastern Desert where quarrying and gold mining operations took place at that time. Mining operations ranged, as our various archaeological surveys have shown, from small prospecting type endeavors to huge undertakings involving hundreds of people. We would very much like to know the nature of ancient geological prospecting that took place and the kinds of people who undertook it in order to locate the most promising auriferous veins prior to their exploitation.

Preserved for us are numerous ancient texts that record expeditions launched into the desert to exploit gold deposits. These are from the pharaonic period; most are official and list the names of the expedition leaders and the number of people sent as well as the monarchs who commanded them. We do have, however, one fascinating, but relatively late account (from Ptolemaic times) of the mining methods and wretched conditions experienced by those hapless souls who actually had to ferret out the gold. Probably not much had changed between this account written in the first century BC and the situation as it existed during the preceding several millennia.

Diodorus Siculus, originally from the island of Sicily as his name implies, visited Egypt sometime between 60 and 56 BC and, apparently, researched his book entitled Bibliotheke(Library) at that time. Diodorus drew heavily on his predecessor Agatharchides of Cnidus, who had written a volume in the second century BC entitled On the Erythraean Sea, for much of his information. While only about a third of Diodorus’ tome survives, his section on gold mining in the Eastern Desert is fascinating and instructive. Debate rages among modern scholars as to which area of Egypt's Eastern Desert Diodorus describes. Some believe it is the Wadi‘ Allaqi region of southern Egypt and northern Sudan while others argue that the area described lies farther north. It hardly matters for our immediate purposes.

Diodorus set the grim scene: Egypt's Eastern Desert, he says, contained myriads of gold mines, many of them very large and very old, dating back, perhaps, to pharaonic times.

Overseers began the work by locating quartz veins where the gold was found. As we know from numerous, lengthy modern geological and archaeological studies, gold obtained from the Eastern Desert is almost invariably imbedded in quartz veins that spider web through the igneous basement rocks. Diodorus continues by relating that following these veins and extracting the gold ore from them was extremely expensive and was brutal and hazardous work. Many individuals laboring in these mines had been condemned to them for criminal offenses or as captives in war. Some of those toiling in the mines had been falsely condemned and should not have been there. Bound in chains, the mining activities took place day and night; there was no escape except a cruel death either in the mines or in futile attempts to flee into the vast menacing desert realms. The guards at these mines, Diodorus relates, were foreigners who spoke languages different from the miners so that there was minimal possibility of fraternization or collusion.

Miners kindled fires to heat and crack the gold-bearing quartz veins. Workers then crushed the crumbled bits using sledges and further reduced these fragments into smaller pieces using hammers. Those working in the dark, narrow, and twisting tunnels carried lamps tied to their heads and forced their bodies to twist in contorted forms to negotiate the small spaces.

Small boys entered the mineshafts and carried out the ore while older men took the ore and pulverized it with iron pestles in stone mortars until it was reduced further in size. Old men and women took the resulting residue and put it into mills standing in rows and in groups of two or three they ground it to the consistency of fine flour. These workers, Diodorus tells us, could not take care of themselves and wore no clothing. Anyone seeing them took great pity for their plight. These people worked until they died and many looked forward to the ultimate escape.

The end of the process involved skilled workmen taking the fine powder and distributing it on an inclined board and then pouring water over it. The water washed away the unwanted lighter-weight material leaving only the heavier gold behind. That ore was then placed in measured amounts into terra-cotta jars. The gold ore was mixed with lead, salt, tin, and barley bran and the jars were then closed with lids and sealed with mud. This concoction was baked in a kiln for five days and nights. The jars were then removed and allowed to cool. Subsequent examination of the jars’ contents revealed almost pure gold with few impurities.

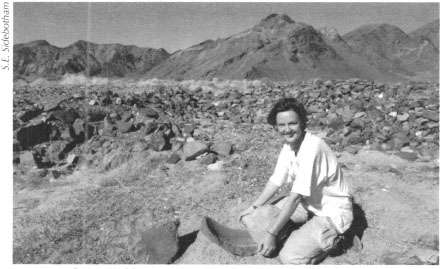

Diodorus’ vivid and heartbreaking description raises many questions. For example, where did the fuel for the kilns come from in these remote desert outposts? Archaeological evidence corroborates the actual mining process: terra-cotta oil lamps have been found in mines used for lighting—during one of our surveys we found such a lamp still in its original position in an alcove carved along a shaft in one of the emerald mines in Middle Sikait—and a sculpted relief now in a mining museum in Bochum, Germany, shows a miner probably carrying a lamp. Those boys conveying the rocks from the mines would have used leather or woven sacks, buckets, or baskets and examples have been found of these in many ancient mines from around the Roman world, especially in Spain; we recently found a woven mat basket discarded in one of the emerald mines in Wadi Sikait. Mortars and grinding stones appear in profusion from Eastern Desert gold mines; we found a particularly well-preserved collection of these during our survey of the Ptolemaic-era gold mines at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli (Fig. 9.2) about fourteen kilometers west of the Red Sea between Marsa ‘Alam and Quseir. The grinding stones seem to have been mainly of the ‘saddle’ variety in Ptolemaic and earlier times and round in the Roman period, though this was not invariably the case.

Our surveys have also found large circular ore grinding facilities that Diodorus does not describe, at the site of Daghbag (Pls. 9.1-9.2), which may be associated with Compasi, mentioned in a number of ancient accounts as a station on the trans-desert route linking Berenike to Coptos. These novel and industrial-sized circular-shaped ore crushing devices were made of hewn stones carefully fitted together and possessing depressions along their long axes to allow a large vertical grinding wheel to be driven by a draft animal. This technology had come to Egypt in the Ptolemaic period from Attica, the region around Athens. In this area of Greece much silver mining, clearly on an industrial scale, had taken place from the early fifth century BC on. The Ptolemies were well acquainted with Attica as the result of their involvement in the Chremonidean War in the third century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 BC) and it was likely in these circumstances that this technology came to their attention.

Fig. 9.2: Ptolemaic gold mining site at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli, with mortars and grinding stones used in gold ore processing.

While we ourselves have not seen other large grinding facilities like those at Daghbag, several German scholars reported the existence of similar ones at the more southerly Ptolemaic-Roman gold mining settlements of Bokari and Barramiya. In addition, large washing tables have also been found in the Eastern Desert often constructed of stone and mortar, but these have been seen at only a few gold mines in the region. This may indicate that only the larger operations actually washed and ‘prepared’ the gold as described in Diodorus’ account; alternatively, the dearth of these washing tables may simply be due to insufficient examination of the vast majority of gold mines in the Eastern Desert from any period in its history. Even so, there are references to gold washing that occur in texts from the period of the Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh Seti I (1306-1290 BC) associated with the rock-cut temple at al-Kanaïs, discussed in Chapter 6. There is another reference to gold washing in the famous Kubban Stele, an important inscription found in a village of the same name dating to the reign of Ramesses II (1290-1224 BC). Thus, it seems clear that Diodorus’ description of washing the gold at the mines had a long history. Yet, Diodorus may well have omitted, through oversight or lack of information, the use of water in another aspect of the gold mining process. Once the rock had been heated water may have been poured over it to cool it quickly thereby cracking it and breaking it up. This would have facilitated the mining and processing operations.

What about Diodorus’ assertion of the servile status of the workers? In the pharaonic period mining and quarrying expeditions were carried out under military control and many of the laborers may well have been convicts or prisoners of war. While in Ptolemaic times forced labor may have prevailed in the mines, the picture is not as clear for the Roman period and the evidence is decidedly mixed on this issue. Perhaps slave, forced free (called corvée), and voluntary free labor was used at different times and places in the Roman era. Certainly there is no indication from the thousands of ostraca found at the. Roman quarry at Mons Claudianus that slaves were used there, but rather skilled free laborers who earned up to twice as much as their counterparts in the Nile Valley. Such may have been the case in the Roman-era gold mines of the Eastern Desert as well. Nevertheless, some ancient Roman written sources refer to use of criminals, slaves, and Christians condemned to mines and quarries as punishment; with the present state of our archaeological evidence, we cannot ascertain, however, which mines might have used them.

Gold Mining Sites in the Eastern Desert

Surveys by German scholars have located scores if not hundreds of gold mining settlements ranging from the Early Dynastic period to the Islamic era. Often the same location continued to be worked over long periods of time, frequently this was done intermittently. Our surveys during the summers of 1996-1999 visited a number of Ptolemaic and Roman gold mines and we drew detailed site plans and maps of the remains of some of the more impressive ones. These included al-Ghuzza, Bir Sirbakis, Bukhalug, Umm Howeitat al-Qibli, and Abu Gerida. We cannot describe all of these, but let us discuss a few investigated by our team and one other excavated by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

The only ancient gold mining settlement studied in extensive detail, including limited archaeological excavations, is that at Bir Umm Fawakhir (Fig. 9.3). Located near the famous Wadi Hammamat, surveys and excavations were conducted here by a team from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago throughout the 1990s. The large settlement scattered up and down several adjacent wadis dated primarily to the late Roman/early Byzantine period (fourth to sixth centuries AD) and would have been, according to the excavators, an important source of revenues for the central government at that time. Scholars investigating this site estimate that at its peak it had a population of about one thousand. It was certainly one of the larger gold mining operations known from any period in the Eastern Desert. The location of earlier mines and quarries along the well-traveled trans-desert route between Myos Hormos and Coptos meant that transport of metals and stone and their protection was greatly facilitated and it may well be that this particular area of gold acquisition prospered in part due to its location on a major transportation artery.

A surprising aspect that our surveys have noted about the vast majority of these gold mining operations from many different eras, including that at Bir Umm Fawakhir, is the lack of associated fortifications or apparent defenses of any kind. This is extremely odd given the value of the metal mined and the temptation among Bedouins and outlaws to attack and rob the settlements or caravans conveying the ore to the Nile. The route linking Myos Hormos to Coptos—along the course of which lay the gold mines and the large associated settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir—preserves a number of praesidia (forts), but these guarded the caravan route or provided escorts for convoys and important individuals as we know from thousands of ostraca recently excavated by French archaeologists. Most of these defenses, certainly those nearby, had long since fallen out of use by the time the late Roman/early Byzantine mining operations at Bir Umm Fawakhir were booming. Other than the skopeloi (lookout/watch towers) that can be found on some of the high points surrounding the mines, what means of defense did these mining settlements possess to prevent marauders or bandits from pilfering the valuable metal? The dearth of forts and other defensive features suggests that there may have been little to fear from outsiders; perhaps troops lived at these mines and since none except Bir Umm Fawakhir has been excavated, evidence of their presence has not yet been discovered.

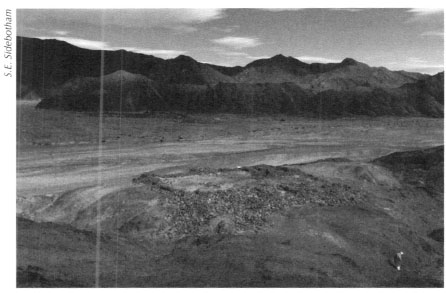

Fig. 9.3: Late Roman-era gold mining community at Bir Umm Fawakhir.

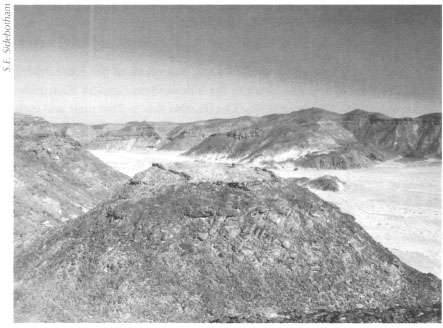

The Ptolemaic and possibly early Roman mining center at Abu Gerida seems to have been extremely important to a number of satellite gold mines. It was clearly much larger than the visible remains now suggest as major portions of the settlement have been washed away by flash floods over the centuries. This gold mining center is the only one we have noted in our surveys that preserves a walled enclosure, perhaps some kind of fort, atop an adjacent hill (Fig. 9.4). Yet, there is no evidence that any gold mining actually took place at Abu Gerida. Its location, the fragments of statues and inscriptions, and the remains of stone molds used for making and repairing metal tools which our survey discovered, indicate, however, that the settlement at Abu Gerida must have played an important administrative role in gold mining operations conducted in the immediate neighborhood. In addition, there is a granite quarry nearby from which the inhabitants of Abu Gerida obtained the material to make the grinding stones used in the gold mining process.

Fig 9.4: Walled enclosure, perhaps some kind of fort, atopa hill adjacent to the Ptolemaic-early Romangold mining centerAbu Gerida.

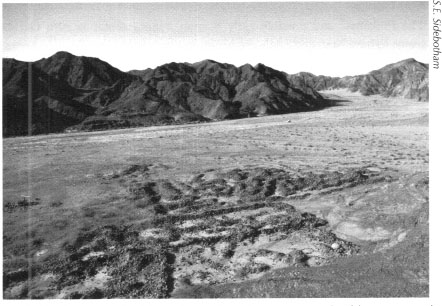

Fig. 9.5: Ptolemaic gold mining settlement at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli. Houses and gold-working facilities on north side of the wadi.

The gold mining operations at al-Ghuzza, just south of the route linking Mons Porphyrites and Abu Sha‘r to the Nile at Qena (ancient Kainepolis/ Maximianopolis), like those at Abu Gerida, also date to Ptolemaic and early Roman times and preserve, in addition to a number of edifices mostly of unknown function, several long, narrow water channels. Our survey could not be certain what function these channels served; they may have been for drinking, irrigation, washing, or gold ore processing as described so vividly by Diodorus. Possibly such channels had multifunctional purposes.

Probably the most informative ancient gold mining operations our archaeological surveys have studied are those at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli (Fig. 9.5). The impressive and sizeable remains at this site appear on both sides of a generally east-west running wadi. On the south side is a large walled enclosure with multiple rooms, which may have had an administrative function (Fig. 9.6). Inside it our survey team recovered portions of a small stone foot from a long-lost statue, probably of a reclining lion or sphinx. Walls of this structure were built of local stone and a number of recycled gold ore grinding stones. On the northern side of the wadi—amid which the ‘Ababda still use a well of unknown date for watering their goats, donkeys, and camels—lay scores of dilapidated structures, probably living quarters. Some shafts survive tunneled horizontally into the adjacent mountainside. Nearby was a gold ore processing area complete with grinding stones and fist-sized quartz pounders used, no doubt, in efforts to remove the ore from the surrounding stone—mainly quartz. All the pottery we collected at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli dates to the third and second centuries BC indicating that the mines had not been worked earlier and had been abandoned thereafter.

Fig 9.6: Large walled enclosure with multiple rooms on the south side of the Ptolemaic gold mining settlement at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli.

A little farther north of Umm Howeitat al-Qibli, in the region of Umm Russ, are the scant remains of an early Roman mining operation, now almost entirely obliterated by the presence of a large and still impressive modern British mining camp erected at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A branch of the Via Nova Hadriana, which we found during our survey of that road between 1996 and 1999, leads off to these mines, which attests their importance into at least the early second century AD.

Giovanni Battista Brocchi was born in Bassano del Grappa, Italy in 1772. He is best known for his interest in mineralogy and botany, especially in Italy. He studied at the University of Pisa and was eventually appointed professor of botany at Brescia. He published on these subjects as they pertained to Italy. Brocchi's interest in Egypt came relatively late in his life. He sailed there in 1823 to study the geology and was supported in his endeavors, as were many of his European contemporaries, by Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha. His Giornale delle osservazioni fatte ne‘visggi in Egitto, nella Siria e nella Nubia was published posthumously in two volumes in 1841. Volume II is especially important as in it Brocchi mentions a number of ancient sites in the Eastern Desert noted by no other European travelers until our own surveys. Unfortunately, Brocchi died prematurely in Khartoum, Sudan in 1826 at the age of fifty-four.

While numerous gold mines and settlements from various periods of Egyptian history have been located, few have been investigated in any detail. More effort should be made to study and understand the ancient mining techniques and the methods ancient peoples used to live and work in Egypt's hyper-arid Eastern Desert.