A Roman Imperial Road and the Northern Part of the Eastern Desert

Many tracks and roads of various sizes and importance. crisscrossed the Eastern Desert from prehistoric times onward and these continued in use and were enlarged and extended later, especially in the Ptolemaic and Roman eras. These thoroughfares joined many desert settlements and Red Sea ports to one another and, eventually, to emporia on the Nile. In this chapter we will examine the Via Nova Hadriana, the latest known ancient route built in the Eastern Desert (Fig. 3.1). This highway also reaches farther north and is the longest of any in the region, about eight hundred kilometers. We will also look at some other ancient sites in the northern part of the Eastern Desert.

The Via Nova Hadriana was only one of several major highways that crossed the Eastern Desert in Ptolemaic and Roman times. These thoroughfares all invariably led to western termini on the Nile. The major Nile cities included, from north to south, Sheikh al-‘Ibada (ancient Antinoopolis), Dendera (ancient Tentyris) and nearby Qena (ancient Kainepolis/Maximianopolis), Quft (ancient Coptos), Edfu (ancient Contra Apollonopolis Magna and Apollonopolis Magna), and Aswan (ancient Syene). All these cities, except Kainepolis, had been founded and were active in the pharaonic period. Later in Ptolemaic or Roman times, however, these became more prominent. These Nile entrepôts did not exist solely to service roads leading into the Eastern Desert; they were self-sustaining without these desert highways. In fact, aside from the recovery of some inscriptions bearing on these Nile ports, little is actually known of the roles they played in Eastern Desert and Red Sea activities.

Fig. 3.1: Map showing the Via Nova Hadriana, associated sites, and road networks,

The one exception is Coptos. This site, about forty kilometers north of Luxor, has been sporadically excavated over the past century or so and has much to tell of its role in Eastern Desert and Red Sea activities. Inscriptions found at Coptos reveal the presence of merchants and troops. Some of the latter hailed from the Syrian Desert caravan city of Palmyra as recorded in one text dated July AD 216. These mounted soldiers patrolled the roads across which caravans bore merchandise from the lucrative Red Sea-Indian Ocean trade. A recent archaeological project conducted at Coptos by Assiut University and the University of Michigan unearthed pottery indicating close connections with many of the forts guarding the roads leading to the Red Sea ports of Myos Hormos and Berenike and with these emporia themselves.

Lying on the edge of the Nile, the ruins of the ancient city of Antinoopolis first came to the modern western world's attention as the result of Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798. Accompanying his 25,000-man army was a sizeable and impressive group of 165 scholars, scientists, engineers, and artists who avidly studied, described, and produced measured drawings and sketches of the natural wonders and ancient man-made monuments of Egypt. They were interested in all periods of Egyptian antiquity, including the Roman, and eventually presented their findings to the general public in a monumental publication entitled Description de l’Égypte. This magnum opus, published between 1809 and 1828, comprised twenty-four tomes including ten folio volumes with over three thousand illustrations, five of which were devoted to antiquities and ancient monuments. In these impressive, often still reproduced and cited publications, the French scholars drew images of the remains of ancient Antinoopolis. Unfortunately, much of what they saw and recorded over two hundred years ago has since disappeared; local villagers have robbed many of the building stones to recycle. However, those Napoleonic-era drawings together with plans sketched by the British savant J.G. Wilkinson (Fig. 3.2), who visited Antinoopolis several decades after Napoleon's scientists, provide us with an idea of what has been lost since the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Recent excavations at Antinoopolis have added to our knowledge by unearthing ancient texts, a beautiful array of brilliant polychrome textiles and clothing, and other artifacts that bring to light what life was like in this important Middle Egyptian city from the second century AD until late antiquity.

Fig. 3.2: Plan of Antinoopolis (c. 1821-1833), drawn by J.G. Wilkinson. Ms. G. Wilkinson XLV. K.6 dep. a. 15, fol. 158; Gardner Wilkinson papers from Calke Abbey, Bodleian Library, Oxford; courtesy of the National Trust.

Sir John Gardner Wilkinson was, from the archaeological point of view, undoubtedly the most important of all the early nineteenth century visitors to the Eastern Desert. He was born in Little Missenden, Buckinghamshire, in 1797. He studied at Exeter College, Oxford, but left in 1818 without taking a degree. In 1820, while visiting Italy, Sir William Gell, an antiquarian, persuaded him to give up his plans for an army career and join, instead, the ranks of archaeologists and Egyptologists.

During his initial visit to Egypt between 1821 and 1833 Wilkinson traveled extensively and took copious but extremely illegible notes, and made many drawings and plans, most of surprising accuracy. Wilkinson was the first to translate correctly many of the ancient Egyptian royal names and he was also the first to make a survey, something he did single-handedly, of all the major sites of Egypt, including the tombs then known in the Valley of the Kings. He assigned numbers to the twenty tombs then identified, establishing the recording system still used today. He published the results of his research in several books and articles. Most important for any study of the Eastern Desert is his volume Topography of Thebes, and General View of Egypt, which appeared in 1835. His book, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, published in 1837, was the most comprehensive overview of ancient Egypt of its time. In 1839 Wilkinson was dubbed a knight, while in 1852, he was granted a DCl from the Oxford University. His drawings, preserved now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and descriptions are important for our understanding of what many of the ancient sites looked like over a century and a half ago. These, in some instances, record features that have since disappeared. Wilkinson died in Llandovery in Wales in 1875.

Hadrian founded Antinoopolis in AD 130 to honor his deceased paramour Antinoos. Originally from Bithynia in Asia Minor, Antinoos had been a favorite of the emperor's for several years. Yet, while on a sightseeing junket and tour of inspection in Egypt with the emperor, Antinoos mysteriously drowned in the Nile. It has never been determined if his death was an accident, suicide, or the result of foul play. In any event, Hadrian was so distraught that he ordered statues carved, coins minted, and a religious cult established in honor of his beloved. He also founded his eponymous city on the east bank of the Nile on the site of an earlier settlement. Hadrian then linked his new metropolis by road to near the Red Sea coast and thence it ran parallel to that littoral terminating at the emporium of Berenike. It was, in fact, the only Roman road in the Eastern Desert to join all the Red Sea ports (except at Suez) to one another by a land route.

According to a famous inscription carved on stone in Greek and dated February 25, AD 137, the Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 117-138) built the eponymous Via Nova Hadriana as a new road from Antinoopolis to Berenike on the Red Sea. The inscription goes on to record that Hadrian furnished his flat, level highway with wells, stations, and forts. Although similar in appearance to other Roman roads in the Eastern Desert, the function and orientation of the Via Nova Hadriana was, on the whole, different from those older companion routes. While earlier major ‘classical’ (that is, Ptolemaic and Roman) roads in the Eastern Desert had a generally east-west orientation and connected ports on the Nile with counterparts on the Red Sea coast, or joined mines and quarries in the desert to the Nile, the Via Nova Hadriana seems not to have had these major functions. In other words, while the other highways provided communication networks for commercial and military reasons, as well as for administrative and control purposes, the Via Nova Hadriana primarily seems to have been constructed as an administrative route. In this respect, the Via Nova Hadriana, although unique in the Eastern Desert, was not, however, unusual for the Roman Empire as a whole; other roads in the Roman Near East also seem to have had primarily an administrative function. For example, the famous Via Nova Traiana, built in the neighboring Roman province of Arabia (basically Jordan and parts of the Negev and southern Syria) during the reign of Hadrian's immediate predecessor, the Emperor Trajan (AD 98-117), seems to have had an analogous function. The Via Nova Traiana linked the southern Syrian city of Bostra to the Red Sea port at Aila/Aelana (modern Aqaba in Jordan). The length and course of the Via Nova Hadriana simply would not have been attractive to merchants shipping goods between the Nile and the Red Sea; the more southerly and older routes in the Eastern Desert were better situated, more direct and shorter for those purposes. As a result, they would have permitted faster and easier travel thereby reducing costs and time on the road, all important considerations to merchants wishing to keep overhead costs down and get products to markets as quickly as possible. Although some small mining and quarrying operations may have benefited from their locations near the Via Nova Hadriana, no major mines or quarries lay close to the road itself. Some gold mines, an amethyst quarry, and some other as yet unidentifiable late Roman settlements located in the desert not far from the Red Sea probably had trunk roads linking them to a coastal road that pre-existed the Via Nova Hadriana. From the time of Hadrian on, the Via Nova Hadriana itself would have replaced this earlier coastal highway. Yet, the need to link desert settlements to a coastal highway probably would not have been a major consideration to those engaged in the initial construction of the Via Nova Hadriana.

The Via Nova Hadriana, like all those ancient roads found thus far in the Eastern Desert, was unpaved. The Romans had similar unmetalled roads elsewhere in the empire; they called these viae terrenae. For the vast majority of the Eastern Desert tracks, paving was totally unnecessary. We must assume by their locations in such an arid landscape that any traffic they bore would have been relatively light compared to that carried by their paved counterparts in Europe. Most travel in the desert would also not have been vehicular, but human pedestrian and animal, which would not have required paving, except perhaps in extremely soft sandy areas. Those sandy areas today that preserve paving appear to have been constructed in relatively modern times to assist movement of motor traffic associated with quarrying operations in the earlier part of the twentieth century. In all likelihood, any ancient paving that might have once spanned the sandy zones would probably have been washed away long ago by the seyul.

There is an extremely long and impressive paved road section that we stumbled upon in August 1997, but our very sagacious Ma‘aza Bedouin guide told us that it had been built by the British about the time of the Second World War to connect Safaga on the Red Sea with Qena on the Nile. For many kilometers this impressive desert highway comprises millions of pieces of cobble-sized stones with the edges bounded by curbing.

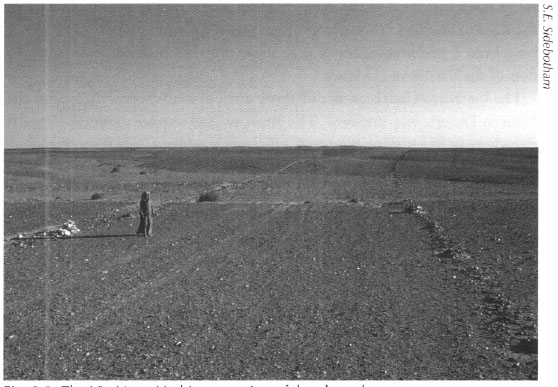

Basically, the ancient desert thoroughfares were cleared of major surface debris, mainly cobbles, boulders, and other impediments, and this material was pushed aside forming windrows, which were the roads’ boundaries (Fig. 3.3). The resulting smooth surfaces enhanced travel and the windrows also served to mark the course of the road in lieu of paving. The surviving windrows that our surveys have encountered, measured, and photographed are not, on average, wide or tall and seem surprisingly similar in their shape for long stretches. We assume they were created by hand, but there must have been some mechanism for smoothing them to a near uniform appearance; perhaps draft animals pulled timber beams along the route acting as a kind of bulldozer to create this rather even impression.

Fig. 3.3: The Via Nova Hadriana: section of the cleared route.

Fig. 3.4: Cairns of piled stones flanking the Via Nova Hadriana.

Cairns of piled stones, ranging in diameter from 55 centimeters to 1.5 meters, flanked the Via Nova Hadriana (Fig. 3.4); these could be found just inside the windrows, atop them or some distance outside them. Along some lengths of the Via Nova Hadriana cairns were spaced extremely close together while along other segments they lay farther apart. The placement of those cairns outside the windrows may provide a clue as to the methods employed in the road's construction. If used as route markers, the cairns placed outside the windrows would have been rather superfluous, as the windrows themselves would have served that function well (Pl. 3.1). The cairns that we now see lying outside the windrows may have been markers placed by initial survey crews and intended to signal the actual course that the route would eventually take. They may have been general indicators of where the route should pass leaving it to the judgment of the follow-up crews, who actually cleared the route and created the windrows, where within the lines of cairns they should place the route. There are also sections, and these occur well north of Berenike, but south of Marsa Nakari (perhaps the ancient port of Nechesia), where cairns survive, but there is no evidence that windrows were ever created. This could indicate that these portions of the route were, in fact, never completed. Alternatively, it could suggest that the putative builders following the cairn-laying survey crews determined that the natural surfaces in these areas were sufficiently clear and firm that no windrows were necessary.

As mentioned before the Via Nova Hadriana was only a small part of the massive Roman imperial road network. In the Roman era, the lands surrounding the Mediterranean were crisscrossed by tens of thousands of kilometers of paved and well-maintained roads; one estimate puts these at about eighty thousand kilometers worth, with an additional 320,000 kilometers of secondary routes. These were well marked along their edges by milestones. Generally columnar in shape, made of stone, and standing about two meters high, these Roman milestones provide a great deal of information about the emperors and provincial governors who built and maintained the thoroughfares and the distances in Roman miles (a Roman mile is 1,478.5 meters, less than an English mile) that any particular milestone lay between two important urban centers. Moreover, these ancient highway signs are a bonanza of information on who built the roads and they also inform us when and which urban areas they linked together. Some bore texts in paint, long since worn away by the sun, wind, and rain, while others were carved and the incised letters filled with paint, usually red. Most were written in Latin, but in the eastern portions of the Roman world Greek might also be used and occasionally even more local dialects, such as Palmyrene, are found on some milestones in Syria.

The Via Nova Hadriana, like other Roman-era roads in the Eastern Desert, however, lacked these traditional Roman milestones. It can, for much of its length, as indicated above, be traced by the cleared surfaces and the resulting windrows its builders often provided and by cairns. Unlike other major roads in European portions of the Roman Empire such as the famous Via Appia in Italy or the Via Egnatia—that ran from coastal Albania through northern Greece to Constantinople, and which were elaborately and costly paved engineering marvels marked by milestones—those in many desert regions, including the Eastern Desert, did not require the great expense and high maintenance costs of their European counterparts. We do not understand, however, why those roads in the Eastern Desert also lacked milestones.

Oddly, very few milestones, or possible road markers, have been found anywhere in Egypt. A few, possibly from the Ptolemaic period, but written in hieroglyphs, survived until recently along the banks of the Nile. Some may appear from Roman times marking the route to Saqqara. Other possible mile markers have been found in the Delta areas of Lower Egypt and in the deep south in Nubia, but their absence in the Eastern Desert greatly handicaps those of us looking to reconstruct the history of road building in the area in Roman times. Instead, the relatively good state of preservation of some of the unpaved routes, of the stations and forts along them, and the potshards that we collect from them allow us to date when the roads were used, if not their actual period of construction.

It has been estimated that the durable paved roads of Roman Europe cost about 125,000 denarii (a denarius was a silver coin, about one and a half day's pay for a legionary soldier in the early Roman period) per mile to build. Their sturdy construction meant that repairs, as are also indicated on some of the milestones, were needed only once every twenty years or so. Though undoubtedly laid out by Roman army engineers and created by the military, it was the civilian communities through or near which these highways passed that were usually responsible for their subsequent maintenance. We have no figures, however, reporting costs for ‘building’ the cleared thoroughfares of the Eastern Desert. By their very nature, construction costs would, indeed, have been relatively cheap compared to the outlays required for their paved counterparts, but who maintained them? Aside from a few scattered desert settlements, mainly mining, quarrying, or military road stations, a few late Roman period communities whose functions are still not entirely clear to us but whose locations lay off the main roads, and the Red Sea and Nile ports, there were no civilian settlements along most of the desert roads, so we do not know how the expenses for their maintenance were handled or who actually repaired them when required; we suppose the military dealt with these issues. In any case, repairs would have been relatively simple consisting of filling in areas eroded by seyul, and restacking windrows and cairns. Repair of elevated sections would have been the most labor-intensive assignments.

The Via Nova Hadriana, like all of the ancient roads we have investigated in the Eastern Desert, varied dramatically in width. Our survey has taken numerous measurements and we have found that distances separating windrows on the Via Nova Hadriana range from just a few meters to a staggering 46.5 meters wide. Unbelievably, our surveys over the years have found Roman road segments that are even broader; one we measured near the quarry at Mons Porphyrites was fifty-three meters wide! These widths are, on average, several times greater than those of paved Roman roads known in Europe and the Near East. Why was there such a great variation in the width of the Via Nova Hadriana, and other desert roads as well? We cannot be certain, but we can speculate. It may be that wider stretches lay nearer the road builders’ camps and were attempts to impress their superiors. The broader segments may also reflect operations of larger work crews. Narrower sections, or those that clearly received less attention through lack of windrows or smaller and fewer cairns, may have lain farther from the camps, had fewer laborers engaged in their ‘construction,’ and attracted less scrutiny by ranking overseers. These, therefore, might have received more desultory attention. We noted where the main road leaves Berenike for the Nile, and is co-terminal with the Via Nova Hadriana, that it is wider closer to the port and becomes narrower farther from it. Yet that 46.5-meter-wide segment of the Via Nova Hadriana noted above lay nowhere near any road station let alone close to any major or even less significant Red Sea port.

But there are other fascinating aspects of the Via Nova Hadriana. For example, in at least two places on the east-west portion of the route artificially elevated sections or ramps were constructed to facilitate movement of traffic from high ground to low. One elevated road segment occurs near Antinoopolis in the Wadi ‘Ibada; it measures about eighty-five meters long and directed the highway around the northern edge of a very deep section of the wadi. The other is a ramp about sixty meters long varying from 4.3 to 5.1 meters wide that lay east of the small road station in Tal‘at al-Arta and connected high ground on the east down to the wadi floor on the west. In another section of the Via Nova Hadriana, paralleling the coast just north of Wadi Qwei, the road seems to bifurcate as it leaves the wadi floor to the north for higher ground for reasons that remain a mystery. Two kilometers north of Wadi Qwei the two roads join; perhaps each was used at a different period in the long history of this desert highway or they were one-way conduits, one bearing southbound traffic and the other northbound.

The Via Nova Hadriana survives in relatively good condition where it traverses the desert between Antinoopolis and the Red Sea. In some places it is actually overlain by a seldom-used modern paved highway linking Ras Gharib on the Red Sea to Sheikh Fadl on the Nile some 245 kilometers away. Once the Via Nova Hadriana starts its journey parallel to the coast, however, its state of preservation is, in many places, somewhat more deteriorated. The reasons for this are varied. First, the water flowing east from the Eastern Desert mountain watershed into the Red Sea has washed away large swaths of the road as the seyul cut perpendicular to its ancient course. Second, it is along and adjacent to the coast, precisely where the Via Nova Hadriana runs, that much modern building activity has taken place; new roads, pipelines, tourist resorts, scuba diving centers, and the growth of Red Sea towns and cities have all led to the destruction of those lengths of Hadrian's highway that come within a few kilometers of the sea.

At certain points along its course, a number of ancient roads intersected the Via Nova Hadriana running, in general, perpendicular to and west from it. These other highways all seem to predate construction of the Roman period Via Nova Hadriana and were major ones joining the Nile to the Red Sea, such as the ancient Quseir/Quseir al-Qadim (Myos Hormos)-Quft (ancient Coptos) road that linked Marsa Nakari (perhaps the ancient Nechesia) on the coast to Edfu (Apollonopolis Magna) on the Nile, or the two joining Berenike first to Edfu and then later to Coptos on the Nile. We will discuss these other roads in later chapters. In at least one instance a small trunk road linked the Via Nova Hadriana to the major roads connecting Berenike to the Nile.

The Via Nova Hadriana did not, in general, run close to the coast, though in a few places, such as just south of Wadi Safaga and immediately north of Quseir, it came within only a hundred meters or so of the sea. The reasons for this, though nowhere mentioned in any surviving ancient written document, are strikingly obvious. First, if the course of the Via Nova Hadriana had lain very close to or right along the coast it would have had to traverse numerous wadis as they debouch into the Red Sea and this would have resulted in large sections being periodically washed away by the powerful seyul flowing into the sea. This would have resulted in the need for frequent repairs. Travel along such a route close to the coast would also have been very troublesome and slow with frequent ups and downs as one ascended and descended the myriads of wadis, which often become more pronounced close to the coast. Fresh water also would not have been found in such close proximity to the Red Sea. Wells dug by a road near the coast would have provided either salty or very brackish water that could not be consumed by humans and, depending upon the extent of its salinity, only with difficulty by donkeys, camels, and horses. Instead, it was the intention of the builders that the road run parallel to the coast, in general, from several kilometers up to fifteen kilometers inland yet, where possible, east of the main chain of the Red Sea Mountains. By opting for this route, the land across which the Via Nova Hadriana ran was, in general, flatter, making road construction, maintenance, and travel along it easier. Any wells dug on or near the road segments this far from the sea would also have provided fresh water. Stations were spaced on average thirty-two kilometers apart with the closest known being about twelve kilometers from one another and the farthest being more or less sixty-five kilometers apart. While our archaeological surveys have traced the Via Nova Hadriana running directly into several Red Sea ports themselves, such as Myos Hormos and Berenike, it bypassed others by four or five kilometers, such as that at Marsa Nakari, or the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r, which then were joined with it by smaller trunk routes. Clearly some of the larger and more prominent Red Sea entrepôts warranted diversion of the Via Nova Hadriana directly to and through them while smaller coastal towns, like Marsa Nakari, for whatever reason, were not so favored.

Sites along the Via Nova Hadriana

Along the east-west trans-desert portion of the Via Nova Hadriana the Romans apparently built no forts (praesidia), but created, rather, unfortified stations and wells (hydreumata). The lack of fortifications along this stretch of road contŕasts sharply with the presence of praesidia along the coastal portion of the Via Nova Hadriana. Praesidia are also found extensively along other Roman roads in the Eastern Desert. Clearly, Roman officials responsible for construction of the Via Nova Hadriana did not perceive threats to the water supplies or lines of communication along the east-west course of the road to the same extent that they did with the coastal portions of the highway and as they did with other Roman roads in the Eastern Desert. We are not certain why this was the case. Perhaps whatever desert dangers there were, mainly marauding Bedouins or bandits, confined their activities to the roads carrying traffic of a more lucrative nature farther south and found the east-west part of the Via Nova Hadriana not worth their attention.

Along the road across the desert between Antinoopolis and the coast, most stations and the route itself survive in relatively good states of preservation despite the fact that those water stops had little substantial architecture associated with them at any point in their history. The fine preservation is undoubtedly due to the general remoteness of the road sections, wells, and stations from any modern areas of habitation or ‘development’ and to the fact that, while subject to some flooding, the road and stations in this area are not exposed to the same intense waterborne seyul that occur along the coast.

One excellent example of such an unfortified stop on this east-west part of the highway is at Makhareg (Pl. 3.2) about forty kilometers east of Antinoopolis. Remains at Makhareg comprise a few buildings and a large well that were actively used from the second to fifth centuries AD. Our survey also recovered Pre- or Early Dynastic stone tools suggesting that the station and route merely exploited earlier ones that passed through the region. Huge mounds of earth surrounding the well itself indicate its repeated clearing and excavation over the centuries and its critical importance to people passing by or dwelling in this part of the Eastern Desert. Nearby is evidence of failed attempts to irrigate cropland in relatively recent times. While no hydraulic features except the well survive at Makhareg, other sites along this portion of the road preserve hydraulic tanks made of kiln-fired bricks and coated with waterproof plaster, features typically found throughout the Eastern Desert at Ptolemaic and Roman water stops. The road station at the early Roman site of Umm Suwagi, about 110 kilometers east-northeast of Antinoopolis and seventy kilometers from Makhareg, is a good example of this.

Once the Via Nova Hadriana arrived close to the coast and began to veer south-southeast the stations took on a different appearance; we believe that our survey has not found all of these stops. We also postulate that at least one trunk road left the east-west component of the Via Nova Hadriana and veered north toward the Christian monasteries at St. Antony and St. Paul. Christians from Upper and Middle Egypt making a pilgrimage to either or both of these two desert monastic centers could best do so by traveling from the Nile at Antinoopolis along the Via Nova Hadriana. Unfortunately, our surveys along the Via Nova Hadriana between 1996 and 2000 had insufficient time and resources to investigate the existence of this putative route to those still functioning monasteries.

All the Roman stops that have survived on the Via Nova Hadriana as it parallels the Red Sea coast, and that we have examined, take on the appearance of praesidia defending intramural hydreumata and cisterns (lakkoi/lacci) or, in some cases, wells located near, but extramural to the forts. Yet, in some instances these praesidia also had other functions as well. For example, the praesidium at Abu Sha'r al-Qibli, where we found ostraca indicating use of the fort in the earliest period of the Via Nova Hadriana and immediately preceding its construction, also supported operations at the larger late Roman fort on the coast at Abu Sha'r, about 5.5 kilometers to the east, beginning in the early fourth century AD. Moreover, the praesidium at Abu Sha'r al-Qibli supported traffic between the larger fort at Abu Sha'r, during its military phase, and the road that led to the Nile at Qena (Kainepolis/Maximianopolis). Several stations on this latter road operated in late antiquity clearly supporting coastal operations at Abu Sha'r by linking it to Qena. We will discuss this route and some of these stations in a later chapter.

Other especially noteworthy praesidia on the Via Nova Hadriana include those at the second and possibly third century AD fort at Abu Gariya, between the modern coastal cities of Hurghada and Safaga, and about sixteen kilometers from the Red Sea, and the early Roman fort in Wadi Safaga (Pl. 3.3), about fifteen kilometers southwest of Safaga. In both these cases, cisterns and rooms inside the ancient fortification walls can still be seen. At Abu Gariya the interior well has been re-excavated in modern times and is still used by the Ma‘aza Bedouin; a three chambered cistern also appears that has been refurbished in modern times though it is uncertain who did this. A water trough outside and north of the Abu Gariya installation suggests that pack and transport animals were watered there and not allowed inside the praesidium itself. This type of extramural watering facility for animals survives at other forts in the Eastern Desert and, as we will see in Chapter 13, was so placed for very practical reasons. At the Wadi Safaga installation, sections of the perimeter walls at the southern corner have been washed away by powerful seyul over the intervening centuries and no indication of an intramural hydreuma is now visible, but remains of waterproof plaster coating a kiln-fired brick basin in the interior of the fort do indicate the existence of internal water storage facilities.

Sites in the Northern Eastern Desert

That part of the Eastern Desert north of the massive Roman quarries at Gebel Abu Dukhan (ancient Mons Porphyrites) has been little surveyed and, not surprisingly, much less is known about the ancient remains in this region than in the areas to the south between Mons Porphyrites and Berenike. Other archaeologists and our own surveys have recorded a few other ancient settlements in northern parts of the Eastern Desert including some copper mines in Wadi Dara. Moreover, our survey investigated one particularly strange and undatable ancient copper mining site in August 1997 in Wadi al-Missara. Here, in addition to the usual array of workers’ huts, our survey located several odd parallel straight lines of stones laid on the ground that do not appear to have been roads; until now we have no idea of their purposes.

About fifty kilometers south of the modern Red Sea town of Ras Gharib at Gebel Zeit a few prehistoric sites have been noted where investigators found lithic tools and other implements from the Paleolithic period and later. Furthermore there were some Twelfth Dynasty (Middle Kingdom, 1991-1783 BC) to late New Kingdom period galena mines, the latter of which were carefully investigated by teams from the Institut français d'Archéologie Orientale in the 1980s. In the Roman period an ancient petroleum seep at Gebel Zeit provided bitumen (Pl. 3.4).

One major site in this northern portion of the Eastern Desert that is probably best known is the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r. When our expedition excavated there between 1987 and 1993 it lay about twenty kilometers north of the center of Hurghada. Today it is completely surrounded by a tourist resort, construction of which began in late 1989 or 1990. The earliest modern European visitors to the fort at Abu Sha'r to record their observations were the British travelers J.G. Wilkinson and his companion James Burton in the 1820s, both of whom drew plans of the site (Fig. 3.5). From that time on many scholars identified the remains at Abu Sha'r with the Ptolemaic and Roman Red Sea port of Myos Hormos. Superficial comparisons of the site and its surroundings with ancient descriptions in the texts of Strabo (Geography) and Pliny the Elder (Natural History) confirmed in the minds of many nineteenth- and twentieth-century savants that the ruins at Abu Sha'r had to be the port of Myos Hormos. This association continued in some scholarly circles into the late 1980s despite evidence produced by our excavations conclusively demonstrating that the ruins at Abu Sha'r could not possibly be those of ancient Myos Hormos.

Fig. 3.5: Plan of Abu Sha‘r, drawn by Richard Burton in the 1820s. Courtesy of the British Library, London.

Fig. 3.6: Reconstruction of the Roman fort at Abu Sha'r,

Our excavations at Abu Sha'r identified the remains not of a walled port town, but rather of a late Roman military garrison (Fig. 3.6). The typical Roman fort here enclosed an area 77.5 meters by 64 meters. The enceinte was originally probably 3.5 to 5 meters high and made of stacked hard stone cobbles and small boulders transported from the mountains and wadis some kilometers west of the fort. The walls were built on sand and had, surprisingly, virtually no foundations. Along the outer enceinte were twelve or, less likely, thirteen rectilinear shaped towers made of relatively soft, brilliant white gypsum blocks that had been carefully hewn. There were two primary gates, the main and largest one lay on the west wall and another slightly smaller one on the north (Fig. 3.7). We also discovered a smaller portal at the southern end of the western wall that had been blocked sometime in antiquity for unknown reasons. The interior of the fort contained a kitchen, food storage areas (called horrea by the Romans), a headquarters building (principia in Latin), fifty-four barracks rooms (called centuriae by Roman soldiers) plus a larger building of unknown function—perhaps an administrative building or commandant's quarters—in the southwest. There were also numerous rooms abutting the interior faces of the fort's defensive wall. We recovered catapult balls (Fig. 3.8), made of white gypsum in one of the towers and in a few of the rooms abutting the main fort wall. Outside the fort's north gate lay the largest Roman bath building ever discovered in the Eastern Desert plus an extensive trash dump. The former preserved the hot bath (caldarium in Latin) complete with elevated floor beneath which heat circulated to warm the water, as well as the stoke hole for the furnace. We found windowpane glass suggesting that part of the bath had windows.

Fig. 3.7: North gate of the fort at Abu Sha'r.Scale = one meter.

Excavation of the large extramural trash dump north of the fort and east of the bath produced abundant finds that told us a great deal about the daily life of the troops stationed here. These included many fish hooks made of copper, bronze, and iron, fishing nets, net weights, and fish remains. Clearly marine fauna comprised an important element of the garrison's diet and fishing probably also provided a pastime that relieved a great deal of boredom in this remote desert outpost. The narrow weave on the fishing nets and examination of the bones of the fish and of the remains of mollusks revealed that the troops caught mainly species that dwelt on or near the reef and in shallow waters and seldom ventured far from shore to catch larger pelagic fish. In the fort we also found large numbers of gaming boards and gaming pieces (Fig. 3.9) suggesting that this was another amusement to keep the troops busy during their off-duty hours. The boards tended to be incised on discarded pieces of gypsum blocks used in the fort's construction and the gaming pieces were most often shards of pottery shaped into round counters.

Fig. 3.8: Catapult balls in the south tower flanking the west gate of the fort at Abu Sha'r.

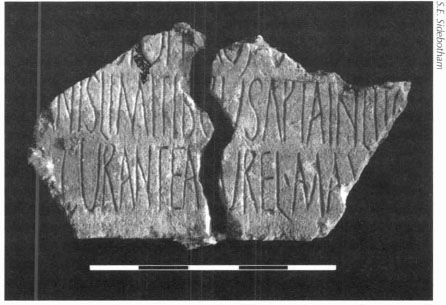

We were also very lucky to recover large fragments of Latin inscriptions when excavating the western gate in June 1990 (Fig. 3.10); we also found two inscriptions in Greek plus numerous graffiti at the northern gate in summer 1992. The contents of these ancient texts were very exciting and provided far more information about the fort and the troops stationed here than we could have reasonably expected. The Latin inscriptions announced that the fort's garrison was called the Ala Nova Maximiana and that it was a mounted unit of either cavalry or dromedaries. From the number of barracks preserved inside the fort we estimated the unit comprised about 150 to 200 men. According to the Latin texts, which are fragmentary—we did not recover them all—the fort had been founded (or perhaps refounded) during the joint reigns of four emperors: Constantine I, Licinius I, Galerius, and Maximinus II; at the time Aurelius Maximinus was Roman governor of this part of Egypt. The periods that these various emperors and the governor ruled allow us to date the inscription to the years AD 309-310. The fragmentary text further alluded to the fort at Abu Sha'r as part of the Roman limes, an administrative zone, by the sea. The mention in the text of the Latin term for merchants and traders (mercatores) suggests that one of the fort's functions was to promote or protect commerce.

Fig. 3.9: Fragments of game boards found at Abu Sha'r. Scale = ten centimeters.

Fig. 3.10: Fragments of monumental Latin inscription over the west gate at Abu Sha'r. Scale = one meter.

The inscriptions we excavated at the north gate told a very different story and provided insights into the history of the installation late in its existence. All the texts that we recovered here were written in Greek and were Christian ecclesiastical in nature. The two most impressive texts were carved into the arch over the entrance to the north gate. In addition, numerous graffiti scoured the northern gate area in the form of personal names, all written in Greek, and Christian crosses. One graffito mentioned “Andreas who sailed to India.” At the point when the north gate received all this Christian graffiti, almost none appeared at the west gate. This indicates that the west gate, so irnportant during the earlier military occupation, had been abandoned and had collapsed by the time of the Christian ecclesiastical use of the fort. What happened to the Roman military garrison and why and how did a Christian group move into the fort?

The information from our excavations indicates that sometime in the late fourth or early fifth century the military peacefully abandoned the fort. There is no evidence at all that the installation was attacked or sacked or otherwise subject to violence. We are not certain why the army withdrew, but it seems to have been part of a broader trend that is evident elsewhere in the eastern Roman Empire at the same time. The military seems to have abandoned a number of forts in the eastern Roman Empire during the late fourth and early fifth centuries AD. at Abu Sha'r there was, then, a period—whose length we could not determine—of non-usc followed by the arrival of the Christians. Fleeing the crowded Nile Valley for a variety of reasons in the late third, fourth, and fifth centuries, one lucky group of Christians would have found the fort an ideal place to live and worship with its ready-made defenses. These people seem to have been fewer in number than the military garrison that had preceded them as there is no evidence that they used the barracks or some of the other interior buildings at all. They converted the military headquarters into a church and, possibly into a martyrium, a place where the bones of some martyr were interred and worshiped. Yet, Abu Sha‘r was not unique in its transformation from a Roman military installation into a Christian ecclesiastical center. This happened on several occasions in the neighboring province of Judea. We are not certain when or why the Christians finally abandoned Abu Sha‘r. We found pottery at Abu Sha'r that might date into the sixth and seventh centuries and an unidentifiable ‘Byzantine’ coin that was minted after AD 498, but we recovered nothing that would allow us to date definitively when the fort was finally abandoned in antiquity by these Christian desert dwellers.