Emerald and Amethyst Mines in the Eastern Desert

We noted previously that Egypt was blessed with great geological wealth. Here we will deal specifically with some of the precious and semiprecious gemstones that were available in the Eastern Desert. Our interest will focus on amethysts and beryls/emeralds. Two regions of the Eastern Desert produced amethysts in antiquity: Wadi al-Hudi and Wadi Abu Diyeiba. The area around Gebel Sikait, Gebel Nugrus, and Umm Kabu, about 120 kilometers northwest of Berenike, were sources for beryls/emeralds (Fig. 12.1).

The earliest gemstones mined in the Eastern Desert were amethysts. From Late Predynastic times (about 3000 BC) onward amethysts were used in jewelry, mainly beads, and small amulets. The ancient Egyptians called amethyst hesmen; the English word ‘amethyst’ derives from the Greek amethyston. The fourth-century BC writer Theophrastus in his book On Stones, indicates that the term derived from the nomenclature of a wine of the same color.

Wadi al-Hudi, an extensive area covering some three hundred square kilometers southeast of Aswan, is geologically diverse with several mining and quarrying sites. The desert hillocks of Wadi al-Hudi have been exploited for their minerals since at least the early second millennium BC; during the pharaonic and Greco-Roman periods the Egyptians traveled there to seek barite, gold, mica, and especially amethyst.

Fig. 12.1: Map showing locations of emerald and amethyst mines and other sites in the Eastern Desert.

AMETHYSTS

Amethyst is a translucent violet-colored form of quartz (silicon dioxide) with a glassy sheen. Although the mineral was mined in Egypt from Late Predynastic times onward, the era of its greatest popularity was the Middle Kingdom (2040-1640 BC). In this period amethyst was primarily used in jewelry such as necklaces, girdles, anklets, and multiple-string bracelets. Occasionally amethyst beads were even capped with gold, threaded with gold beads into amulet-case shapes, and carved into various amulet forms including scarabs.

In the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BC), however, amethyst was less commonly used for personal adornment, possibly because it had become very difficult to obtain, as there was a temporary dearth of known sources, although it may be that its strong coloring did not combine easily in the composite inlays popular at the time. Yet, by the Ptolemaic period, the mineral regained its popularity and continued to appear in jewelry, especially in the form of truncated biconical (late Ptolemaic and early Roman period) or pear-shaped beads (sixth and seventh centuries AD). Indeed, Pliny the Elder, writing in the AD 50s-70s in his encyclopedic Natural History, referred to Egyptian amethysts, and in about AD 200 Clement of Alexandria wrote that amethysts were among “the stones which silly women wear fastened to chains and set in necklaces.”

The Wadi al-Hudi region was the primary location in Egypt for mining amethyst in the pharaonic period and it appears to have peaked in the Middle Kingdom from the late Eleventh to the Thirteenth Dynasty (2040-1640 BC). At this time the violet hued semiprecious stone was particularly favored in the superb jewelry of the pharaohs, their queens, and princesses. During the Old Kingdom the principal amethyst mines appear to have been located at Toshka in the Western Desert. While there is some evidence for the continued exploitation of Wadi al-Hudi after the Middle Kingdom, the principal amethyst mines of the later Ptolemaic and Roman periods were in Wadi Abu Diyeiba, southwest of the modern Red Sea town of Safaga.

It appears that the mining of amethyst during the Middle Kingdom was on a par with the extraction of turquoise in Sinai, the quarrying of choice stone in Wadi Hammamat, and similar enterprises elsewhere. In the Middle Kingdom, judging from the inscriptions alone, at least thirty-nine expeditions were sent to the turquoise mines in Sinai, fifteen to the Wadi al-Hudi amethyst mines, and thirteen to the Wadi Hammamat region.

Expeditions to the amethyst mines and quarries were dispatched at intervals by royal command. Although the leadership of these expeditions varied from reign to reign, it always fell to representatives of the king and his administration. In addition to the caravan-leaders, the inscriptions at Wadi al-Hudi paint a broad picture of other personnel such as stonemasons, large forces of ‘recruits,’ ‘braves,’ ‘laborers,’ overseers, and certain specialists. The minerals obtained went to the royal and state treasuries, which would enable the king to reward his high officials appropriately. On a symbolic level the campaigns could demonstrate the king's control over the most far-flung regions, while on a political level it seems likely that the mining and quarrying expeditions, like military campaigns, were dispatched to reinforce centralized political control.

The principal landmark of the Wadi al-Hudi area is a prominent rocky hill, Gebel al-Hudi, which is located about halfway along the broad flat floor of the main wadi. Wadi al-Hudi stretches for about twelve kilometers, with a complex network of ridges and smaller wadis. The traces of ancient mining and quarrying expeditions are scattered throughout this adjacent region of smaller valleys rather than on the floor of the main wadi itself.

In the eastern part of the area are five ancient sites all of which are probably Roman or later (Fig. 12.2). From north to south they comprise a barite mine with a few huts, a small hill fort, and two gold mines with associated settlement areas, consisting of stone- and mud-brick workers’ huts, and shelters that were partly formed by caves in the rock face.

The amethyst mines at Wadi al-Hudi were rediscovered by the geologist Labib Nassim in 1923 on the western side of the wadi where several areas of archaeological interest can be found clustered together amid a succession of high rocky ridges and valleys. These include two hilltop settlements to house the miners, one of which dates to the Middle Kingdom. The other, about three kilometers to the south, can be attributed to the Roman period.

Miners of the Middle Kingdom constructed a substantial settlement (3,500 square meters) atop an asymmetrical conical-shaped hill, adjoining an amethyst mine, at the northern end of Wadi al-Hudi. The settlement had a dry-laid stone enceinte, which provided good defense against attack.

At three corners of the wall are rough protruding piers, each provided with a crudely constructed platform that enabled the defenders inside the enclosure to gain a good view around the settlement and maximize their height above any attackers. Inside the rough stone-fortified enclosure are about forty dry-laid stone-built workmen's shelters, covering the slopes of the hill on all sides. At the summit of the hill was a substantial building, which accommodated successive mining expedition leaders.

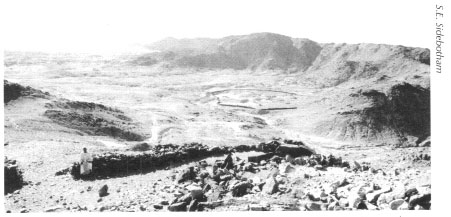

Fig. 12.2: View from the fortified hilltop settlement into Wadi al-Hudi. Another fortified installation is visible on lower ground in the middle distance.

South of the Middle Kingdom settlement is a major L-shaped open-pit amethyst mine. The deposits of purple amethyst appear to have been completely worked out in pharaonic times. A low row of stones surrounds the edges of the mine; these apparently acted as a simple demarcation line or boundary. There are also some spoil heaps.

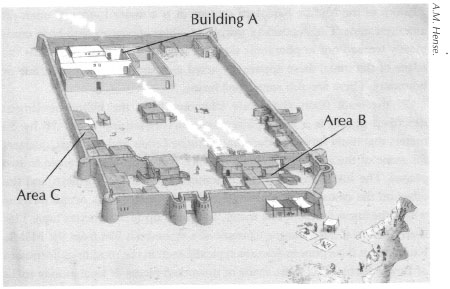

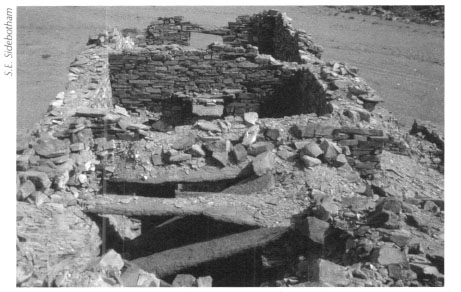

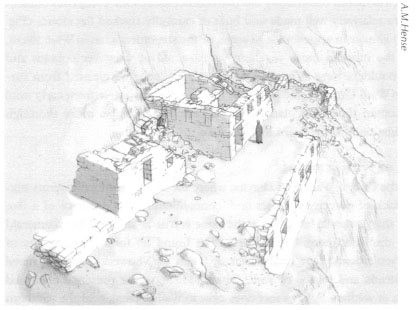

On the wadi floor, about one kilometer from the hilltop settlement described above, is a rectangular stone fort measuring about 70 by 50 meters that likely served as the administrative center and, perhaps, quarters for some of the officials (Figs. 12.3-12.4). It was probably erected in two phases. The installation had two entrances, one on the northern and the other on the eastern side, and some of the perimeter walls of the fortress, with a thickness of about one meter, still stand up to two meters high. This is an unusual if not a unique example of a stone-built fort from the Middle Kingdom; it incorporates features typically seen in the mud brick fortresses of Lower Nubia. The walls, made of unworked pieces of local granite rocks of various sizes, preserve arrow slits, while curved bastions provide a line of fire for the fort's defenders; these project from the perimeter walls and at the corners of the fort.

The interior of the fort, which preserves a number of stone rooms and buildings, can be divided into three main sectors. The most notable and carefully built interior structure is Building A, which might have functioned as the original ‘organizational center’ of the fort. This building, which is farthest away from either entrance, consists of relatively large and well-defined rooms and has walls that are preserved to about the same height as the perimeter enceinte. It was built, however, well away from this enclosure wall, which created a kind of corridor to allow defenders to man the entire circuit of the main wall quickly in case of attack.

Fig. 12.3: The Middle Kingdom fort at Wadi al-Hudi. The amethyst quarry was to the left of this structure.

Fig. 12.4: Reconstruction of the Middle Kingdom fort in Wadi al-Hudi.

Attached to Building A are adjoining rooms with walls that are lower and less well preserved and which are comparable in quality of workmanship to the rooms built in Area B, in the northeastern sector of the fort. Yet, some of the rooms in Area B were, in contrast to the rooms of Building A, erected directly against the outer wall of the fortification in a way that would have complicated any defensive operation. The third complex of rooms, Area C, is in the southeastern part of the fortified building; its walls are relatively low and of inferior construction.

The area of Wadi al-Hudi preserves numerous inscriptions, freestanding steles, graffiti, and rock-carvings, some of which have been stolen while others have been transferred to the Cairo and Aswan Museums. The Wadi al-Hudi texts provide useful information on the number of gemstone mining expeditions, the caravan-leaders and the personnel working at the site. Although the dated graffiti and steles range from the end of the Eleventh through the Twelfth Dynasty (1991-1783 BC) and into the Thirteenth Dynasty (Sobekhotep IV, 1730-1720 BC), the inscriptions seem to make clear that the amethyst mines were especially exploited in the reign of Senwosret I (1971-1926 BC), as well as frequently in the reigns of Senwosret III (1878-1841 BC) and Amenemhat III (1841-1797 BC).

Many of the larger rocks in the hilltop settlement still bear carved geometric shapes, figures and hieroglyphic inscriptions, particularly near the summit and on the eastern side of the hill. Another hill, with a large number of inscriptions and drawings, is roughly midway between the hilltop settlement and the Middle Kingdom fort.

A large stone stela was originally set up during the beginning of the Twelfth Dynasty on a hill where many other Middle Kingdom inscriptions were carved in the rock. The commissioner of this large inscribed dedication was the royal official Hor, who was sent to Wadi al-Hudi by King Senwosret I:

The majesty of my lord, this chief god of the Two Lands, who has decreed the labor ‘beautiful is he in this land’* has sent me, having assigned to my charge a troop, to do what his ka desires concerning this amethyst of Ta-sety. I have brought a great quantity there from which I have collected like (what I collect) at the door of a granary, been dragged on a sledge and loaded on pallets.

Another stela, commissioned by the steward Hetepu, provides some insight into the number of people involved in the mining operations. It preserves an account of another mining expedition sent by pharaoh Senwosret 1:

List of the expedition of the Lord-Life, Prosperity, Health that came to fetch amethyst for the sake of all the wishes of the Lord-Life, Prosperity, Health. General of Troops and Retainer of the South, Resuwi, son of Intef, son of Renesi. Strong troops of recruits of all of the Southern City, 1000 able-bodied men; braves of Elephantine, 200 men; braves of Ombi, 100 men;from the Residence, chief prospectors 41 men; officers of the Steward Hetepu, 56 men; caravan leaders, 50 men….

Only three years later, the official Mentuhotep proudly recollected his deeds in the Wadi al-Hudi:

I ordered the excavation of new mines. I did not fall behind what others had done. I fetched there from in great quantity, I hewed out lumps of amethyst.

He also reminded travelers of the firm grip the king had on the area:

His dread renown having fallen upon the Hau-nebu, the desert dwellers being fallen to his onset. All lands work for him; the deserts yield to him what is within them….

After the cessation of operations in Wadi al-Hudi in the Middle Kingdom there is little evidence that amethyst mining was again undertaken in Egypt until the Ptolemaic period. At that time new areas were exploited in the Wadi Abu Diyeiba region. Our surveys in and around Wadi Abu Diyeiba revealed four hundred to five hundred long narrow trenches covering an area of approximately three square kilometers. The largest of the trenches was about one hundred meters long, twenty meters deep, and three meters wide. We picked up bits and pieces of low grade amethysts on the spoil heaps near some of these trenches. Exposure to the sun over extended periods of time will fade the purple hue and this fact may help explain why our survey recovered so few fragments of these semiprecious gems.

Associated with these mining operations in Wadi Abu Diyeiba were three small areas of building remains. The largest concentration comprised, at most, only ten or twelve badly dilapidated structures. Numerous, apparently modern, robber holes in this location indicate repeated attempts in relatively recent times to loot antiquities and vandalize the remains. We conducted surveys here in June 2000 and June 2004. In our most recent fieldwork we found half a dozen fragments of inscriptions in Greek. Religious in content, the ancient texts indicate the popularity of deities at the settlement including Isis, Pan, Apollo, Serapis, and Harpocrates. One of the inscription fragments we recovered joined with and completed a text discovered and published many decades ago that dated to the reign of Ptolemy VI and his wife Cleopatra II (175-145 BC). We also found scores of representations of human feet carved into the surrounding sandstone. Elsewhere in Egypt and the ancient Mediterranean world such representations of human feet are associated with the worship of the goddess Isis and such is likely the case in the settlement at Wadi Abu Diyeiba as well. Isis, as we have noted in earlier chapters, was an extremely popular deity worshiped in the Eastern Desert.

In conjunction with these Greek inscriptions we also recovered a small altar made from the locally available sandstone and two pictorial reliefs, which we discussed in detail in Chapter 6. The appearance of so many texts, pictorial reliefs, an altar, the representations of human feet and other religious artifacts indicates that this ‘main’ settlement was probably the administrative as well as religious focal point of the amethyst mining operations in the region.

Only about a kilometer southeast of this main site we found the remains of a small satellite settlement comprising a few crude huts several of which made use of giant boulders for portions of their walls. Also about a kilometer southwest of the main settlement we discovered what appears to be a small temple or shrine, which we discussed in Chapter 6 (Fig. 6.4).

There is no evidence of the existence of small huts near any of the mining trenches, which suggests that the ancient workers lived in tents; these, of course, have left no traces in the archaeological record. The work force was probably never very large; we estimate approximately one hundred individuals. Lack of fortifications suggests that those who worked here felt relatively secure from attack and further indicates that the work force likely comprised free labor, which required no guards, rather than forced slave labor that would have necessitated close supervision. While there is today no evidence of wells in the area from which the work crews would have obtained their water, these were undoubtedly sunk in the various wadis where the work took place and have, over the centuries, been filled in by waterborne sediments carried during the infrequent but torrential rains and resulting flash floods in the region.

We have far more information about the ancient beryl and emerald mines partly because many more remains survive from these operations and we have studied them in more detail than the amethyst mines. Beryl is a mineral that almost always occurs as elongated crystals with a hexagonal cross-section, and which is colorless in its ordinary form. However, one of the gemstone varieties of beryl is emerald, which has a distinctive green color. True emeralds are bright, uniform medium to dark green, and transparent. Yet, the famous Egyptian emerald mines produced very few of these true emeralds; the Egyptian beryl usually has a cloudy translucency and a light green color.

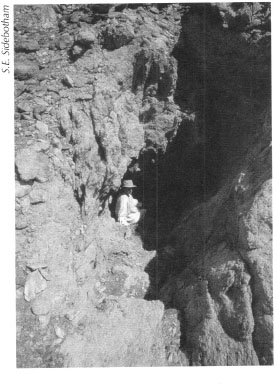

The beryl/emerald mines lie about 120 kilometers northwest of Berenike and about thirty-five kilometers southwest of Marsa Nakari in a region known to the Romans as Mons Smaragdus (Emerald Mountain). This area is not a single mountain at all, but a series of mountains and wadis covering a zone of about 250 square kilometers in the region of Gebels Sikait, Nugrus, and Umm Kabu. In this area our surveys have located nine major beryl/emerald mining settlements. The terrain is honeycombed with hundreds if not thousands of open pits and vertical and horizontal mining shafts (Fig. 12.5) as well as an abundance of potshards attesting intensive efforts especially in the early through late Roman periods and, to a lesser extent, in Islamic times. Many ancient authors, including Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Claudius Ptolemy, report on the mines and the bustling activity surrounding their exploitation. Lesser-known authors writing later in the third and up to the sixth centuries AD also recount the wealth produced from the mines. A local man, Olympiodorus from Thebes on the Nile, recorded in the fifth century AD that one could not visit the emerald mines without the permission of the King of the Blemmyes, a desert tribe that exercised some political power in the region at that time. The latest ancient reference is by Cosmas Indicopleustes, a Christian monk who spent time in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean region in the sixth century.

Fig. 12.5: Middle Sikait. entrance to a Roman and Islamic-era beryl/emerald mining shaft.

From the remains of painted letters and numbers surviving above some of the mine entrances and the presence of relatively modern structures, it is evident that emerald mining operations continued, in some places, well into the twentieth century. This is confirmed by reading some of the accounts of earlier twentieth century British geologists who worked in the region. We also have some, though at this point not much, evidence that at least one of these settlements was inhabited and, therefore, the mines worked, in Ptolemaic times.

The Mons Smaragdus area was the only source of beryls/emeralds known to the Romans that lay inside their empire. Other regions mined in antiquity in the Old World could be found in India and possibly Austria though the latter may have been worked only in post-Roman times. Mining in the Islamic period in the Mons Smaragdus area does not seem to have been on as grand a scale as in the Roman era and once the Spanish began to exploit the higher quality emeralds from the mines in Columbia, South America in the sixteenth century and later, most beryl/emerald mining activity in Egypt came to a halt. Today there is some danger that these ancient mines in the Mons Smaragdus region and their related settlements will be damaged or destroyed in the search for beryllium. Used as a highly heat resistant material in the aerospace industry, the great value of beryllium may lead to reopening of the mines in this area with potentially catastrophic consequences for the ancient archaeological remains.

Let us examine a few of the larger and more interesting of these beryl/emerald mining settlements. Our fieldwork has investigated to one degree or another all nine known ancient settlements associated with beryl/emerald mining, but we will discuss here only five of these. The one best known, due to our intensive, detailed survey work and limited excavations, is that in Wadi Sikait, known in antiquity as Senskis or Senskete. Farther north up Wadi Sikait we have examined and surveyed two other related sites. Though their ancient names are unknown, we have simply labeled them Middle Sikait and North Sikait. Two others of great interest, but which we have only examined in a cursory fashion thus far, include one in Wadi Nugrus, just southwest of Sikait and one in Wadi Umm Harba, east of Sikait.

Our initial survey work in winter 2000 and summer 2001 drew a detailed site plan of the remains visible above ground in Wadi Sikait and North Sikait. Our survey work continued, but was not completed, at Middle Sikait in summer 2002. While there was a rather sketchy overall plan of the ruins at Sikait drawn by Wilkinson in the early nineteenth century (Fig. 12.6) and a geological-archaeological one published in 1900 by D.A. MacAlister, surprisingly, ours was the first detailed and precise map ever drawn of the ancient archaeological remains.

Fig. 12.6: Roman-era beryl/emerald mining community at Sikait, drawn by J.G. Wilkinson (Ms. G. Wilkinson sect. XXXVIII. 39 page 80; Gardner Wilkinson papers from Calke Abbey, Bodleian Library, Oxford; courtesy of the National Trust).

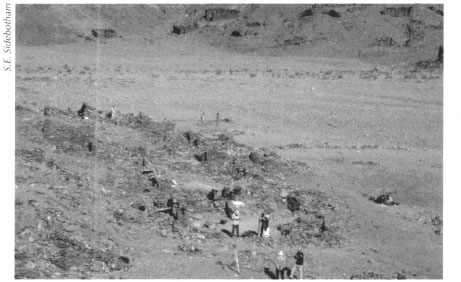

The southernmost site in Wadi Sikait preserves the remains of scores if not hundreds of structures that march up the steep slopes of the mountains. The wadi runs more or less north-south thereby dividing the settlement into eastern and western portions (Figs. 12.7-12.8). As mentioned in Chapter 10, many buildings have façades intact and portions of their interiors still standing and include complete doors with lintels, windows, shelves, and other features. Most impressive are two temples on the eastern side of the wadi cut into the mountainsides, which we discussed in Chapter 6. In addition, there is also a large freestanding edifice on the western side of the wadi at the southern end of the settlement, which we called the ‘Administration Building’ and another, which we called the ‘Tripartite Building’ located farther up the side of the hill to the north and west of the Administration Building. An amazing architectural façade at the northern end of the site on its eastern side we dubbed ‘Six Windows.’

Fig. 12.7: Wadi Sikait running more or less north-south, dividing the Roman-era beryl/emerald mining settlement into eastern and western portions. Excavations on the western side of the wadi.

Fig. 12.8: Plan of the Roman-era emerald mining community at Sikait.

Early European travelers to the southernmost settlement in Wadi Sikait, however, were most attracted to the two rock-cut temples. Frédéric Cailliaud, a French metallurgist and jeweler from Nantes, first discovered the ruins at Sikait in 1816 and made a return trip in 1817. One of many Europeans employed by the Egyptian ruler Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha early in the nineteenth century, Cailliaud had been commissioned to search specifically for the lost emerald mines. At that time nobody, except a handful of Bedouins, actually knew where exactly they might be found or if it would be feasible and profitable to reopen them. Cailliaud only had Bedouin tales and the imprecise accounts of ancient Roman authors to guide him. The description he published and the fanciful drawings he made of the two rock-cut temples, which appear in Chapter 6, subsequently piqued the interest of others to visit the remains including the famous Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni and British savant J.G. Wilkinson. The larger rock-cut temple lying somewhat farther north up the wadi is far more impressive and is, indeed, the object of attention of the bulk of the tourists who visit the site; most only examine this edifice and rarely venture to other parts of the ancient settlement.

FRÉDÉRIC CAILLIAUD

Of importance to our understanding of the Eastern Desert were the travels of the French goldsmith and metallurgist Frédéric Cailliaud. Born in Nantes in 1787, he studied mineralogy in Paris. He left for Egypt after visiting the Netherlands, Italy, Sicily, Greece, and Asia Minor. There he traveled with Drovetti in 1816 through Nubia as far as Wadi Halfa. Cailliaud became one of several Europeans employed by Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha in the early nineteenth century, and he was commissioned to find the lost emerald mines, rumors of which had circulated from various Bedouin and other accounts. He succeeded in discovering them in 1816 and returned the following year for a more extended visit. These sojourns resulted in descriptions and several drawings of the ancient mining settlement in Wadi Sikait which he published in 1821 in a book entitled Voyage à l'oasis de Thèbes et dans les déserts situées à l'orient et à l'occident de fa Thébaïde fait pendant les années 1815, 1816, 1817 et 1818. While undoubtedly impressive and artistically attractive, these etchings are somewhat fanciful and are not accurate renditions of the remains in Wadi Sikait. Nevertheless, Cailliaud's discoveries attracted others to visit the site to record, often more accurately than he, what was to be seen there. The emeralds from the region proved to be very low grade and while some mining efforts were made thereafter, they were not successful; the gemstones from Columbia, South America were not only vastly superior in quality to those from the Sikait region, but were also cheaper to mine and ship. Cailliaud also traveled to the Khargha and Siwa Oases, and along the Nile as far as Meroë. He returned to France in 1822 with a large collection of objects. Two years later, he was appointed an assistant curator at the Museum of Natural History in Nantes, where he died in 1869.

Opposite this larger rock-cut temple on the western side of the wadi and approached by several staircases and a ramp is by far the most impressive freestanding building anywhere in the ancient settlement and, arguably, in the entire Eastern Desert. Our survey dubbed this impressive structure the Administration Building, though we have little evidence that it served this purpose (Fig. 12.9-12.11 and Pl. 12.1). Cailliaud believed that this structure was a temple, but this identification also lacks any supporting evidence. Cailliaud produced several drawings of this edifice that, although imprecise, are more accurate than those he made of the aforementioned rock-cut temples. Wilkinson also made some plans of this impressive structure. Completely intact, except that portions of the eastern and southern walls lean dangerously at an angle, this three-room building has walls standing to heights of almost four meters, a main portal on the east, and a subsidiary entrance on the south. Two small windows pierce the main walls, one on the north and the other on the south side. The outermost room had been paved in large flat stones carefully fitted together. The wall separating the first and second room has an impressive portal flanked in the wall by niches with shelves topped by pediments. We do not know if these two larger rooms were ever roofed. If so, likely the roof was in timber as the span would have been excessively wide and the monolithic stones required would have been too heavy for the walls. A second smaller portal connects the second room to a smaller third room. This latter room is partially cut into the bedrock and is filled with debris including some sizeable tumbled stone roof beams averaging 2.25 meters long; several original stone roofing beams remain intact in their original positions over this third room (Fig. 12.11).

Fig. 12.9: Sikait, panoramic view of the so-called Administration Building.

Fig. 12.10: Reconstruction of the so-called Administration Building at Sikait.

Fig. 12.11: Sikait, the so-called Administration Building, roof construction.

The so-called Tripartite Building (Figs. 12.12-12.13) lies a little north and up the hill from the Administration Building. This impressive structure perches at the upper end of a winding street that leads up from the wadi bottom below. The edifice rests atop an impressive artificial platform that has partially collapsed. Divided into three major rooms, one exterior door and a window survive intact and numerous shelves and interior doors are evident in various states of preservation. Like the Administration Building, the Tripartite Building was also constructed through partial excavation into the surrounding bedrock. We do not know what function this impressive edifice served, but we anticipate that future examination, including excavation and consolidation work, may provide the answer.

Fig. 12.12: Sikait, the so-called Tripartite Building.

Fig. 12.13: Reconstruction of the so-called Tripartite Building at Sikait.

There are a number of other impressive structures visible at Sikait, unfortunately all serving functions that remain a mystery to us. One of the most haunting is the façade of a structure that we called Six Windows (Fig. 5.2), which we mentioned briefly above. Based upon six surviving windows in its two southern-facing façades, this building was equally alluring to earlier travelers including J.G. Wilkinson who, on his visit to Sikait in the early nineteenth century, drew a panoramic sketch of the settlement with Six Windows shown prominently in the foreground from behind.

Our excavations on the lowest modern visible levels of Sikait on both the eastern and western sides of the settlement revealed extensive activity in late Roman times. Houses dominated this lower part of the settlement. These had large open courtyards in which animal husbandry and some gardening took place (see Chapter 10). Gardening was evident from the numerous small stone boxes used, no doubt, to contain wooden trellis works for plants, bushes, shrubs, or small trees. We even found the remains of a root system intact leading from some of these boxes, but unfortunately the species of the plant could not be identified. Some of the boxes preserved charred remains in their interiors. These small, shallow stone boxes with no stone bottoms were fairly uniform in appearance and size. They survived in areas that would have been directly exposed to the sun as well as in shaded locations, which would have received only indirect sunlight. This suggests that several different species of plants were cultivated. The stone boxes appeared individually or in groups of four to six scattered throughout the courtyards. Several of the open courtyards also preserved evidence of small-scale industrial activities and, likely, limited animal husbandry. These pastimes would have provided a form of entertainment or been hobbies for those dwelling in this forlorn location and would have had the added benefit of supplementing their diets with some fresh produce. Otherwise most of the food consumed here was likely hauled in great distances from the Nile Valley and to a lesser extent from the Red Sea.

We also found a number of locally carved items made from the readily available, very soft, and easily worked schist-talc stone including beads, children's toys such as camels and dolls, bracelets, and loom weights or spindle whorls. Some of the thousands of beryl/emerald fragments we recovered had been pierced to make beads for jewelry for local use. We also retrieved over 2,500 beads many of which appear to have been imported from India and Sri Lanka. Many of these beads were high quality including gilded specimens and ones made from carnelian and quartz, which indicates that at least some of the residents of Sikait had a fair degree of discretionary wealth.

We excavated evidence in the form of a few potshards, possibly, and a coin that there was contact between Sikait and the caravan kingdom of the Nabataeans, whose capital was carved from the mountains at the rose-red city of Petra, in modern Jordan. The archaeological context in which our excavations in winter 2002-2003 recovered these fascinating artifacts suggests that they arrived on the site in the early first century AD, which was the zenith of Nabataean commercial activity throughout the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

As we noted above, Sikait was but one of nine emerald mining centers that we have discovered thus far in the region of Mons Smaragdus. A few kilometers farther up the same wadi we found a large site that we named Middle Sikait. Though preserving few buildings, the hundreds of mine shafts and plethora of associated potshards scattered over a wide area indicate a hive of activity here in at least the first, second, and fourth centuries AD. The most impressive single feature of Middle Sikait is a massive artificial ramp or causeway several meters wide that clings to the sides of peaks as it snakes about 1,600 meters up from the wadi floor to a building concentration part way up the mountain side (Fig. 12.14). The large buildings found at the upper end of the ramp appear to have had public functions though given our paltry evidence at this time, we cannot determine what those might have been. Mines and pathways, artificially cut in the mountains and built up of rubble where necessary, cover a large area. Watchtowers and lookout points appear at strategic locations throughout the site. In one particularly alluring example, a rock-cut staircase leads down into a deep shaft that spiderwebs off into many directions no doubt following potentially rich veins. Outside this example is a tabula rasa carved beside the entrance (Fig. 12.5). Perhaps at one time this preserved painted letters, or numbers, long since faded away, indicating the mine number and labor force assigned here; surely this would have facilitated the Roman administrators’ penchant for keeping accurate records of the lucrative activities conducted in this mine. We can only assume that similar tracking methods were used at many if not all the mineshafts, but we have noted no others.

Somewhat farther north of Middle Sikait, up Wadi Sikait, we have completed a survey of the mining community in a location we named North Sikait. This less impressive settlement comprising scores of structures dates only to late Roman times and may suggest that as earlier more easily accessible and transportable sources of emeralds became exhausted these less accessible sources farther up the wadi were tapped. Many of the mineshafts here have been worked in modern times as the presence of painted numbers and letters indicates and as the existence of clearly modern structures in the nearby wadi attests.

Fig. 12.14: Ramp at the Roman-era beryl/emerald mining community at Middle Sikait.

Another impressive mining community nearby and only a few kilometers south and west of the main, southernmost settlement in Wadi Sikait can be found at Nugrus. Our surveys have located one path that linked Sikait to Nugrus over the intervening mountains; there were undoubtedly many others. Strewn along and near the path we noted hundreds of mining shafts and dozens of buildings and graves of those who lived, worked, and perished in these remote mountains in the Eastern Desert. Undoubtedly a thorough archaeological survey of this area would reveal even more. We also marveled at the remains, unique as far as we know, of a bridge-like structure that crosses a steep cliff face along this mountain trail.

Analysis of the potshards we have collected at Nugrus indicates that the community thrived in at least the early and late Roman periods. If we ever excavate the ancient remains, we may well discover that Nugrus had a much longer history than its potshards now suggest.

Nugrus, like Sikait, clings to the relatively steep sides of the wadi of the same name. Our survey of this settlement, which comprises scores of buildings, has only just begun and has concentrated primarily thus far on recording about twenty of the best-preserved structures (Figs. 12.15-12.16 and Pl. 12.2).These contain windows, doors, interior shelves and, in some cases, stone roofs. One impressive structure rests atop a large and elaborate artificial platform. As at Sikait, and despite some excellent preservation, we have no concrete evidence of what purpose most of the buildings served. Somewhat south of the main concentration of structures, our survey located a very nice multi-roomed edifice portions of which preserve doors and stone roofing, which we described in Chapter 6 as a temple.

We discovered another mining settlement only in winter 2002-2003 that lay in Wadi Umm Harba, east of Sikait. Approached by a winding narrow path cut through the mountains, which includes rock cut stairways and artificial ramps similar to those we found at Middle Sikait, this mountain track was marked by cairns leading from the southern limits of Middle Sikait to a settlement in Wadi Umm Harba. Comprising about forty-five structures and surrounded by scores if not hundreds of mining adits, pits, and vertical shafts, this quaint community has two distinct areas. One comprises edifices that are relatively well made and built of carefully stacked flat stones (Fig. 12.17) similar in appearance to some of the structures seen in Wadi Sikait, while the other is more cavalierly constructed of whatever cobbles and small boulders were at hand. The cursory evidence we gleaned from surveys in Wadi Umm Harba indicates that the site was active from early until late Roman times. We plan to return here to conduct a more thorough investigation at some point in the future.

As in the case of Wadi Abu Dieyiba where the absence of fortifications suggests lack of perceived threats and, concomitantly, the presence of a free rather than a servile labor force, the same is true at all of the beryl/emerald mines discussed here. Our surveys have found no forts guarding any of these settlements. Our excavations at Sikait did, however, unearth metal arrowheads and pieces of scale armor indicating the presence of armed guards or soldiers. A large fort does exist in Wadi Gemal, near the southern limits of the beryl mining area. This may be the praesidium of Apollonos referred to in a number of ancient texts. The remains of this massive fort of Roman date, one of the largest thus far recorded in the Eastern Desert, covers almost a hectare. It seems by its location, however, not to have served to coerce local labor forces, but more to reassure and provide an important administrative center for regional mining activities. The positioning of this fort on the main route between Berenike and the Nile also indicates that it played a role in the support and monitoring of trans-desert commerce and communications between the Nile emporia of Edfu and Coptos on the one hand and the Red Sea port of Berenike on the other.

Fig. 12.15: Structure at the Roman-era beryl/emerald mining community at Nugrus.

Fig. 12.16: The same structure at Nugrus.

Fig 12.17: Structures at the Roman-era beryl/emerald mining settlement in Wadi Umm Harba.

While we have found amethysts and beryls/emeralds in profusion at the various mining centers, what evidence do we have of their actual use in jewelry from ancient times? There are two valuable sources of information on this. One is, naturally, the jewelry itself. Found in ancient tombs and elsewhere, these gemstones were frequently set in stunning gold necklaces, earrings and bracelets. Numerous examples of these survive and can be seen in museums around the world with particularly fine specimens in the British Museum in London.

Another fascinating source from the ancient world that sheds light on the appearance and use of jewelry set with amethysts and beryls/emeralds survives in the form of painted mummy portraits from Roman Egypt (Pl. 12.3) These so-called Fayyum mummy portraits, used to cover the mummified and wrapped remains of mainly mid-level bureaucrats and their families, survive in large numbers and depict the busts of deceased men, women, and children particularly from the first, second, and third centuries AD. Many of the women appear with elaborate coiffeurs, wearing their finest clothing and donning their most valuable possessions: necklaces and earrings of gold set with a variety of precious and semiprecious stones including pearls, amethysts, and emeralds. These mummy portraits are the prized possessions of several museums and private collections. Some of the finest can be seen in the British Museum and Petrie Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna, and the J. Paul Getty Museum in California.

* The name of the mine or mining project.