In order to have a better insight into the day-to-day lives of people living in the Eastern Desert we must examine their domestic architecture in both military and civilian contexts. While surviving examples range from the Prehistoric period until early Christian times, we will focus on the Ptolemaic and Roman era when evidence indicates a relatively large population living in the area on a more or less permanent basis.

As a result of extensive survey work throughout the Eastern Desert, archaeologists have found large numbers of architectural remains. Many are immediately recognizable as temples, warehouses, areas of industrial activity (mining and quarrying related processes, metal and glass working, and brick making), fortified and unfortified road stations, as well as other public buildings and domestic structures. There are also thousands of road marking cairns and, especially along the Myos Hormos–Coptos road, about sixty-five to seventy signal and watch towers (skopeloi).

The original or main function of many structures, however, often cannot be determined. Some buildings, clearly, had multiple purposes. We must assume that sizeable numbers of structures, whatever else they might have been, also served as domestic spaces for living, cooking, sleeping, or relaxing. Ptolemaic road stations and mining communities present us with the problem of identification of work as opposed to domestic areas. Since no Ptolemaic-era desert settlements have ever been excavated, we can only hazard a guess as to which rooms, based only on walls visible above ground level, might have served domestic functions.

Some of the most easily identifiable domestic/residential structures, however, can be found inside Roman military installations. The centuriae (barracks) of Roman soldiers are canonical in their appearance and general location inside Roman forts throughout the empire; these centuriae mimicked in stone, brick, and timber the ground plans of tents that Roman troops pitched while on campaign anywhere in the empire and would, theoretically, have accommodated a group of eight men. The Romans called this small unit a contubernium. Rooms in other enigmatic late Roman era settlements also clearly served domestic purposes, as we shall see later in this chapter.

Our investigation of domestic architecture will estimate the size of the populations of some of these ancient desert communities as well. The vast majority of the settlements discussed here-mining, quarrying, military, and those of unknown function-scattered throughout the Eastern Desert, have not been examined to any extent. Some have been surveyed, that is, drawn in plan, but very few have been excavated. Thus, we can only surmise that a substantial percentage of structures in any one of these communities served as areas of domestic activity. Determining the sizes of the ancient populations that dwelt in these various settlements is, thus, very tentative as we cannot be at all certain which structures were places where people lived as opposed to those used for more public activities, storage, or animal pens. Nevertheless, estimates have been made for the quarries at Mons Claudianus, a small nearby satellite quarry at Umm Huyut, at Mons Porphyrites, and at Mons Ophiates. Archaeologists, including ourselves and others, have also calculated numbers of inhabitants for the late Roman gold mining settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir, for five late Roman desert communities, for the fort at Abu Sha'r, for some of the praesidia in the desert, especially those excavated by the French along the Myos Hormos–Coptos road, and for some amethyst and emerald mines. Very approximate estimates have also been made for population numbers at Berenike and Myos Hormos.

The Earliest Inhabitants of the Desert

The Eastern Desert was not always as inhospitable as it is today. Prior to the last Ice Age, about twelve thousand years ago, the region received more precipitation, which resulted in the presence of a larger variety and number of flora and fauna. Stone tools show that already in the Late Paleolithic period (before about 10,000 BC) both the desert and Red Sea coast were inhabited. These people were not isolated from the rest of the population of Egypt; some of the earliest evidence for contact between the Nile Valley and the Red Sea dates to about 10,000 BC.

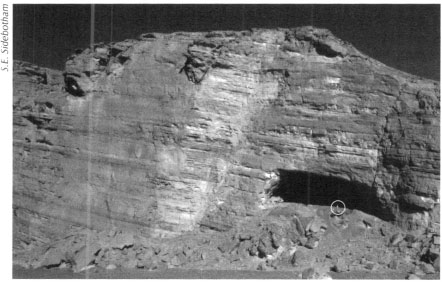

At Sodmein, some thirty-five kilometers west-northwest of Quseir, a cave part way up a limestone cliff forms the oldest known human shelter in the Eastern Desert (Fig. 10.1). Inside, Belgian archaeologists excavated seven archaeological levels of the Middle and Late Paleolithic period the oldest one of which dates back approximately 115,000 years. This layer contained huge fireplaces and stone tools. In a much later phase, just after 5000 BC, the Belgian team excavated the earliest remains of domestic goats thus far identified in Egypt.

The settlements of the Badarian period (5500-about 4000 BC) along the Nile in Upper Egypt comprised temporary structures. People used the huts, windbreaks and storage pits to support themselves in small-scale agricultural, fishing, and hunting activities. It is likely that they also sent occasional hunting expeditions deep into the Eastern Desert.

Fig. 10.1: Sodmein Cave, occupied in the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) period.

Note figure standing at mouth of cave.

Later, some domiciles undoubtedly comprised light structures, like the 3500 BC house excavated in Hierakonpolis, which consisted of a wooden frame covered with reeds and skins atop a wooden wall. Similar types of buildings were still used in the Roman period, when they housed workers of the quarries and goldmines in the Eastern Desert. Temporary structures like the tents of the modern ‘Ababda Bedouin, made of wooden skeletons covered with skins and mats may also have been used.

Most domestic architecture in these earlier periods, however, has left no trace in the archaeological record. For example, the Early Dynastic (soon after 3000 BC) quarry at Manzal al-Seyl, located about seventy-five kilometers northwest of Hurghada and south of Ras Gharib (discussed in Chapter 4), preserves few if any huts or other structures, aside from some stone rings. This suggests that tents or other portable and impermanent forms of housing were used to accommodate the workmen. Since no potshards were found either during the initial discovery of the site or when we visited it in 1997, dating is difficult. Nor can the age of Manzal al-Seyl be determined from symbols appearing on the stone vessel blanks left abandoned in the quarries. Since, however, the quarries produced numerous stone vessels made of green tuff and tuffaceous limestone, which were used for burial offerings only in the First-Third Dynasties (2920-2575 BC), they must date to this era.

During the early Twelfth Dynasty (Middle Kingdom) and extending into the early New Kingdom period a coastal settlement came into being on a coral terrace at Marsa Gawasis. An industrial area with kilns for copper working indicates that this settlement was inhabited for longer periods, although the houses were simple structures and, apparently, only for temporary use.

The earliest evidence of domestic architecture that our own fieldwork has revealed thus far was in Wadi Abu Mawad. Many small single, double, triple, and quadruple roomed structures hugged the lower edges of some steep but low mountains along both sides of a relatively narrow and winding wadi. Structures were built of locally available stones in haphazard plans. The shards we gathered for study were not Ptolemaic, Roman, or Islamic so, by default, they had to be pharaonic. We could not determine when in pharaonic times this settlement had been occupied, but a number of pictographs carved onto the walls of rock outcrops survive nearby including one of a giraffe; whether this rock art was contemporary with the settlement remains uncertain. This conglomeration of structures was probably a mining camp though we could not be certain of this identification. Nearby were numbers of shallow pits on the side of a hill, perhaps the remains of some prospecting activities associated with this community.

David Meredith received his PhD at University College London in 1954. In contrast to others who visited and wrote about the Eastern Desert noted throughout this book, Meredith was more of a library scholar. He apparently did not care for the desert all that much. Relying mainly upon the notes and observations of others, he nevertheless produced impressive publications that were quite thorough in their presentation. According to Leo Tregenza, with whom Sidebotham had two interviews, one in 1988 and the last in 1993, Meredith only visited the Eastern Desert twice. Nevertheless, he was incredibly prolific throughout the decade of the 1950s, writing many articles and producing in 1958 an important map of the Greco-Roman antiquities known in the Eastern Desert for the important Tabula lmperii Romani series.

Settlements of the Ptolemaic and Roman Period

As noted above, we know much more about later settlements, especially of the Roman era, when activities in the Eastern Desert intensified and logistics were dramatically improved. During this period the functions of these sites are more evident, but not necessarily mutually exclusive. This is especially true at the mines and the quarries, where the bulk of the populations were civilian, but where there was also clearly a military presence.

The forts guarding the quarry sites of Mons Claudianus, Mons Porphyrites, and Mons Ophiates (in Wadi Umm Wikala) also contain rooms, some of which must have served as sleeping and eating areas, though both would not necessarily have been found in the same room, as was the case at Abu Sha'r, which we discuss more below. It is often difficult to determine which activities many of these spaces originally served as functions for a specific room may well have changed over the life of the facility in which it was located and, in some instances, rooms were later abandoned, often cleared of their interior décor, and converted to trash dumps where huge amounts of rubbish were deposited. The latter was true at Mons Claudianus and at Abu Sha'r.

Mons Claudianus

The archaeologists who most recently surveyed and excavated at Mons Claudianus made some population estimates. The smaller fort (the excavators referred to this structure as the “hydreuma”), near the large fort, accommodated about fifty men while they calculated that the nearby workers’ village housed about 150 persons. This is only a small portion of the site. The few graves found around the settlement and their extremely robbed condition precluded population estimates based on mortality figures gleaned from burials. An interesting ostracon found during the excavations, however, lists the distribution of water to those present on the site on a specific day in about AD 110, an era of intense activity at the site of Mons Claudianus. The text names 917 people of whom at least sixty, may be more, were soldiers. Of course, these numbers would have fluctuated over the course of any given year and, naturally, as operations at the quarries waxed and waned over the centuries.

Mons Porphyrites

At the Mons Porphyrites quarries British archaeologists found several areas of habitation scattered over a wide area dating from the first through fifth centuries AD. While some ancient burials, mostly badly robbed, were studied (see Chapter 8), the ancient written documents found at the site during British excavations between 1994 and 1998 do not provide, unlike those at Mons Claudianus, any indication of the extent of the population here at any point in antiquity. An approximation of the number of people (excluding nearby support stations in Wadi Umm Sidri, and at Badia’) can, nevertheless, be made based upon analysis of seven major areas of habitation in the region of the quarries. The settlements from south to north include: Southwest village, Loading Ramp village, Lykabettus village, Porphyrites fort (and village just to the south), Foot village, Northwest village, and Bradford village.

Southwest village preserves about eighty rooms in a number of structures. Some rooms are large enough to accommodate more than one person. We estimate eighty to one hundred sixty people lived here. Loading Ramp village was smaller, with about twenty-five to thirty relatively small rooms that could, we calculate, have accommodated about twenty to twenty-five people. Lykabettus village seems to have been relatively large with over sixty-two rooms some of which could have housed more than one person. We estimate that sixty to one hundred twenty people could have resided here. The large fort in Wadi Ma‘mal, called by the excavators ‘Porphyrites fort,’ and associated, but very ruined, Workers’ village just to the south, are difficult to calculate as the village is in such ruinous condition. The fort preserves numerous rooms of which we estimate twenty-four to thirty were for habitation. Thus, the fort itself perhaps accommodated on a permanent basis thirty to thirty-five people and the ruined village to the south several dozen. Foot village preserves only sixteen rooms, which are not large, suggesting a maximum population of ten to fifteen people. The Northwest village was somewhat larger (with about forty rooms) capable of housing at least thirty-five to forty people. Bradford village was by far the smallest and was used for a relatively short period of time. Its approximately ten potentially inhabitable rooms within seven buildings suggest a population of eight to ten persons. Thus, the seven villages and one fort in the Mons Porphyrites area accommodated approximately 267 to 441 more or less ‘permanent’ inhabitants. If we consider outlying pockets of a few workmen here and there living in temporary shelters or small rock enclosures, guards at the various watch towers scattered around the site plus the crews arriving and departing to haul the stone, this would add another several dozen to perhaps one hundred persons. This would make the entire operation at Mons Porphyrites about half the size of that at Mons Claudianus, that is, about four hundred to five hundred persons, when crews hauling stone to the Nile were present.

Wadi Umm Wikala/Wadi Semna

We conducted survey work between 1997 and 2000 at the first to early third century AD Roman quarry at Wadi Umm Wikala/Wadi Semna (ancient Mons Ophiates). After Mons Claudianus and Mons Porphyrites, Mons Ophiates was the third largest hard stone quarry operating in the Roman period in the Eastern Desert. Yet, despite this, we determined that the residents in the two main areas of surviving structures, one near the quarries in Wadi Umm Wikala, and the other in a large praesidium about 1.8 kilometers to the south in Wadi Semna, numbered only approximately one hundred to two hundred. We calculated that the ninety-three extant rooms accommodated about two persons each with some rooms, of course, used for storage or administrative purposes. These figures do not take into account buildings washed away by desert floods, of which there was good evidence, and they also do not consider the several dozen outlying quarries that were worked at different times, and not simultaneously, throughout the life of the site. Judging from the sizes of the various quarried areas anywhere from a few to perhaps a few dozen worked at each location. Rarely do any structures survive in the more remote quarries suggesting no long term activities took place there; as with some of the other quarries and mines examined in this chapter, it is likely that many workmen lived in tents, which have left no trace. Again, population figures would have fluctuated as work at the quarries waxed and waned and as Nile-based crews came and went to haul stone and bring in supplies.

Umm Huyut

In June 1993 our survey located, based on analysis of the abundant pottery we collected there, a small early Roman (first-second century AD) community and associated quarries at Umm Huyut. Only about six kilometers as the crow flies (about fifteen kilometers by desert track) south of the main center in Mons Claudianus, this diminutive settlement comprised only fourteen buildings made of dry laid stone. One of these was a large public structure approached by two staircases; it would not have served any domestic purpose, but was either religious or administrative. The remainder of the rooms ranged in size from relatively small to sizeable. There was also a lookout post or well-preserved hut above one of the quarries. We estimate that perhaps twenty people resided at Umm Huyut.

The various mining settlements-gold, amethyst, and some of the beryl/emerald-usually preserve buildings comprising low walls about one to one and a half meters high consisting of one, two, less often three, and rarely four rooms. We assume, since the walls of the vast majority of these quickly erected edifices are relatively low and there is little tumble surrounding them, that the superstructures were likely made of more perishable materials such as matting tied to upright wooden poles, or some type of tent-like edifices. The rooms are invariably relatively small and are roundish and oval to rectangular in plan. Frequently though not always, one room usually could not be reached from inside an abutting room via a common doorway; those wishing to move from one room to the next often had to go outside and enter the adjacent room by a separate portal.

Some rooms contained a single raised feature made of stone (a mastaba) that may have served as a bed. Other rooms attached to those with mastabas, were too small for humans to have occupied and likely served as storerooms or animal pens. In a few rare instances small niches or bins also survived inside some of the rooms. On occasion the fronts of those structures comprising multiple rooms had a small raised courtyard. We have rarely found any evidence of burning (suggesting that there was cooking) in any of these rooms; perhaps much of that type of activity took place out of doors. This would have been especially prudent and necessary if the superstructures of these buildings had been made of highly flammable tent-like material or matting. In addition, heat generated by cooking fires in such small enclosed spaces would have been intense and rather unbearable especially in the summer months.

The presence of very few, or lack of any, structures at some of the mining sites, and in areas that have clearly not been washed away by desert flash floods, suggests that some temporary non-stone made features catered to the needs of the workers. The reasons for dearth of more permanent architectural remains indicate in these instances that the work at such quarries and mines was either of short duration overall or of a brief enough period of time each season that more permanent dwellings were not viewed as necessary.

Gold Mining Settlements

Samut

In a gold mining center at Samut, north of the large fort in the wadi of the same name, situated near the ancient road linking Berenike to Edfu, we located another impressive settlement comprising work areas, ramps and platforms, and several substantial walled buildings including one that resembled a fort. This impressive ‘fort’ had in its interior a series of large rooms, which must have included residential areas, but if so, they did not resemble, in size anyway, any structures of similar function we have seen elsewhere in the region. Pottery from this site, which included some interesting amphora handles stamped with marks of those who made them, indicated activity here in the late Persian occupation and Ptolemaic eras (fourth century Be into third and perhaps second century BC).

Umm Howeitat al-Qibli

In 1998 our survey spent five days in two separate visits drawing a detailed plan of the large Ptolemaic gold mining settlement at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli. Divided into two sections by a wadi oriented roughly east-west, the south side of the settlement comprised a few small structures, but was dominated by a large walled installation, resembling a fort, which must have been the administrative center of the community. Interestingly, the walls of this fort-like structure, which preserved a large open area with rooms on the southern and eastern sides, included many recycled gold ore grinding stones.

The preponderance of the architectural remains at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli, however, consisted of buildings on the north side of the wadi. These included areas where ore processing took place-the fist-sized quartz hand pounders were still laying in bunches-around a somewhat elevated work platform; saddle-shaped grinding stones lay nearby (Fig. 9.2). Clearly, in addition to working here, many people also lived on this side of the wadi. Most structures on the northern side of the site were in very ruinous condition. The majority had such dilapidated walls that few entrances or other details could be identified. In this area we picked up a small early Ptolemaic bronze coin. Pottery shards were abundant and dated activity at the site in the early to middle Ptolemaic period (third-mid second century BC).

Many of the small to medium-sized rooms inside structures found toward the eastern and western ends of the northern side of the wadi at Umm Howeitat al-Qibli undoubtedly served residential purposes. Many of the structures on the north side of the wadi were too small for public activities involving more than a few people and were also clearly separated, in some cases apparently by long partition walls, from the areas where ‘industrial’ and work-related functions took place. Those work areas that we readily identified lay more or less in the center of the settlement on the north side of the wadi; smaller structures, in some cases no doubt domestic areas, lay to the east and west of the work areas.

Bir Umm Fawakhir

As mentioned in Chapter 9, a team from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago conducted a detailed survey and limited excavations in the 1990s at the late Roman/early Byzantine period (fourth to sixth centuries AD) gold mining settlement at Bir Umm Fawakhir. This site is located in the Wadi Hammamat about halfway along the Myos Hormos–Nile road. The Chicago team counted the number of structures at the site (Pl. 10.1), which were scattered up and down several adjacent wadis, and concluded that, at its zenith, there were approximately one thousand people in residence at Bir Umm Fawakhir. This was certainly an impressive number and the logistics of supplying everyone and the various animals there with adequate food and water must have been considerable.

Amethyst Mining Settlement

Wadi Abu Diyeiba

In June 2004 during our survey of the Ptolemaic and early Roman amethyst mines in the Wadi Abu Diyeiba area, about twenty-five kilometers southwest of Safaga, we were surprised to find so few structures of any kind since we counted about four hundred to five hundred trenches, some up to one hundred meters long by twenty meters deep by three meters wide, where digging for amethysts took place. A potentially sizeable, but unknown number of workmen were employed to remove these semiprecious stones; yet we found in three different locations a combined total of less than about twenty structures and some of these were clearly not for domestic use. Many, if not most, of the stone building remains lay some distance from the areas where the amethysts were mined. We must conclude that the bulk of those working and residing in the Wadi Abu Diyeiba mining area likely lived in tents, which, of course, have left no traces in the archaeological record. How extensive the use of tents might have been and to what degree this hinders estimation of numbers of residents are questions that remain to be answered.

Some desert communities were surprisingly large and the buildings well crafted. Among these are the emerald and beryl mining settlements at Sikait and Nugrus (see Chapter 12), for example, which consisted of hundreds of edifices. At these mining centers builders paid much more attention to construction techniques than we find at most sites in the Eastern Desert. This was due primarily to the nature of the locally available building stone which, when quarried, sheered off in thin flat sections that could be easily stacked. This is in great contrast to most desert settlements that were made of locally available cobbles and small boulders picked up off the desert floor in their environs. The thin flat stone slabs allowed construction of thicker and more stable walls. This, in turn, permitted the creation of multiple-storied structures fashioned with great care. The larger edifices at Sikait and Nugrus have substantial walls of some height (up to four meters) and thickness (over a meter) with surviving windows, multiple doors, often of impressive dimensions, many with lintels extant, interior niches and shelves, and other accoutrements (Pl. 10.2). Some clearly had stone roofs intact while others were likely of stone or timber, which has long since disappeared. While these larger structures were likely for public rather than private use, we have excavated several edifices at Sikait that were clearly domestic, at least in their primary functions.

During summer 2002 and winter 2002-2003 we excavated trenches in the lowest areas of the mining community at Sikait on both the eastern and western sides of the wadi that bisects the site. We found well-built structures that had large open, walled-in courtyards in which a range of domestic activities took place. These included cultivation of small gardens (Fig. 10.2). Gardening was evident from the numerous small stone boxes used, no doubt, to contain wooden trellis works for plants, bushes, shrubs, or small trees (see Chapter 12). Several of the open courtyards also preserved evidence of small-scale industrial activities and, likely, limited animal husbandry. These pastimes would have alleviated the boredom and supplemented the diets of those living and working here with some fresh produce. Most of the food consumed here was likely hauled great distances from the Nile Valley and to a lesser extent from the Red Sea.

One high status multiple-storied residence at Sikait had operated from the turn of the Christian era until late antiquity (Figs. 10.3-10.4). In this building we recovered some of the earliest items found during our excavations: a few possible Nabataean shards and a Nabataean coin, which arrived on the site sometime at the turn of the Christian era or some decades thereafter.

Fig. 10.2: Remains of stone boxes that contained wooden trellises for plants in a courtyard of one of the houses at Sikait. Scale = twenty centimeters.

We found remains of a few wells in the wadi linking Sikait to two sister settlements, those at Middle Sikait and North Sikait, but most wells and water sources were long ago buried beneath flood-borne sediments carried through the wadi by torrential rains (see Chapters 2 and 13). Should we ever be able to locate these wells using ground penetrating radar and somehow determine when in the lives of these settlements the various water sources were used, we could begin to obtain some idea of the population sizes of the communities that served them. The large numbers of graves surrounding the settlements in Wadi Sikait and Nugrus have been badly robbed and dates for their deposition, therefore, cannot, in many instances, be determined. Thus, attempting to calculate population sizes at different points in the histories of Nugrus or Sikait (both of which operated at least from the first to the sixth centuries AD) based upon the associated cemeteries, is not possible.

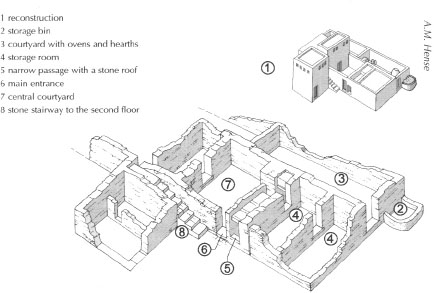

Fig. 10.3: High-status multiple-storied residence at the Roman-era community at Sikait.

Fig. 10.4: Reconstruction of one of the high-status multiple-storied residences at the Roman-era settlement at Sikait shown in Fig. 10.3.

The numerous praesidia (Roman forts) examined during our surveys both along the several ancient trans-desert roads and at quarries, and those sites excavated by other European teams, especially along the Myos Hormos–Coptos road and inside the quarry forts at Mons Claudianus and Mons Porphyrites, suggest that barracks for troops are less easily identified in those cases until excavation provides additional clues. In the praesidia many rooms about the interior faces of the main fort walls. Where excavated, some have proven to be store rooms, baths, and headquarters; others undoubtedly served more domestic purposes.

Abu Sha‘r

The best example of domestic quarters for the Roman military in the Eastern Desert appears in the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r, which we discussed in Chapter 3.

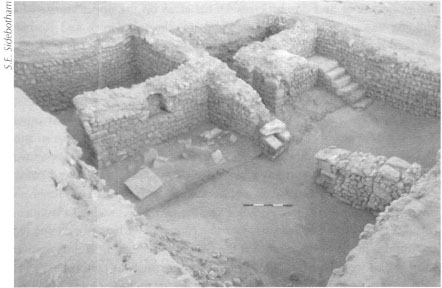

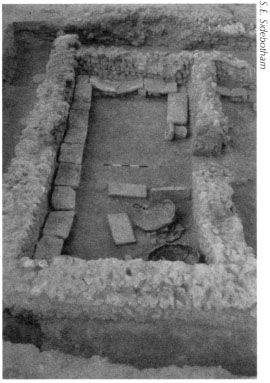

Fifty-four centuriae (barracks for troops) are readily apparent in the area between the north gate and the principia (headquarters). Some of the additional thirty-eight or thirty-nine rooms found abutting the interior faces of the main enceinte of the fort may also have served as barracks, but we cannot be certain of this as we excavated only a few of the rooms of the centuriae and even fewer rooms adjacent to the main fort walls during our expedition between 1987 and 1993. Each barracks room measured only about three by three or three by four meters, a relatively small space that would have accommodated at most three men in very cramped conditions (Pl. 10.3). Thus, there was no room for a contubernium (tent group), consisting of eight men. The small living area meant that few domestic activities other than sleeping could have occurred in these centuriae. In the southwestern part of the fort, one room where the roof had collapsed subsequently had dumped in it numbers of large skeletons and huge shells of green sea turtles mixed with other types of trash. In this and similar circumstances determining the original function of such rooms is extremely difficult or impossible.

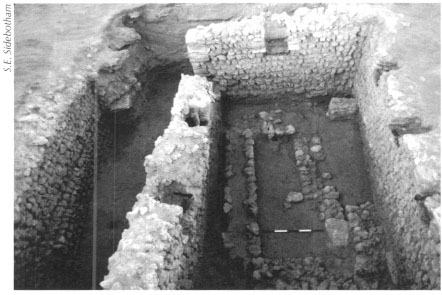

Most dining for troops stationed at Abu Sha'r would likely have been communal and in rotation and would have taken place elsewhere inside the fort. In the southeastern interior part of the fort our excavations in the summers of 1991 and 1992, in fact, uncovered an extensive food preparation area including a large oven with a floor made of kiln-fired bricks measuring 3.4 meters in diameter (Pl. 10.4). Remains of wood, some pieces of which were embedded with nails, indicating some previous use, lay nearby. This was clearly destined for consumption as fuel in the oven. There were also quantities of ash that had recently been removed from the oven. Located in the same large, and we assume only partially roofed, room with the oven were fragments of grinding stones made of vesicular basalt. These would have been used to grind grain or other foodstuffs. Five long and barrel vaulted granaries (called horrea in Latin) lay immediately west of and adjacent to this kitchen area. We never located any large room, which we could definitively identify as a mess hall/dining facility. Most extra-curricular activities involving several men, such as gaming and gambling-as we know from a number of game boards recovered in our excavations-would in all probability also have taken place in areas other than the barracks. Due to the number of gaming boards we found in one room abutting the southern interior fort wall, we surmised that it might have served primarily as an entertainment area.

Let us estimate the numbers residing at the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r. Identifying fifty-four small barracks and probably others abutting the fort walls and with no more than two or three men per barracks, we arrive at a rough calculation of approximately 150 to 200 men garrisoning this fort. As this was a mounted unit (known from the fragmentary Latin inscription we found tumbled at the west gate-see Chapter 3), probably dromedary rather than cavalry, the space allotted to each soldier may have been more generous than for infantry.

Other estimates of population sizes of Roman forts in the desert include calculations made for the garrison at Apollonos, probably located in Wadi Gemal, An ostracon that was part of the archive of the Nikanor family, discussed in Chapter 7, records some grain supplied to the installation there. Based on this document various modern estimates put the total garrison strength somewhere between sixteen and thirty-six men. Yet, the structure we see today is one of the largest forts surviving in the entire Eastern Desert. Two huge walls of this fort, though badly damaged and with the other two completely washed away, measure 119 meters and 78 meters long respectively. Sixteen to thirty-six men could not possibly have been sufficient to defend such a large installation The ruined walls we see today, were, in all probability, erected after the Nikanor ostracon was written. In its substantially larger and later manifestation, perhaps over two hundred men garrisoned this 0.92 hectare-large cantonment.

Frots on the Myos Horrnos-Coptos Road

French archaeologists made some interesting estimates of garrison sizes of Roman praesidia they examined along the Myos Hormos–Coptos road. They based these on space available and notations in ostraca from the excavations of the forts. Ostraca were recovered from the forts of Maximianon and westward toward Coptos on the Nile; none east of Maximianon were found. The garrisons there, along with the ostraca, were primarily from the period of the Flavian emperors (Vespasian and his sons Titus and Domitian, AD 69-96) until those of Trajan (AD 98-117) and Hadrian (AD 117-138)-probably also the era when the large fort in Wadi Gemal, discussed above, was erected. Some of the praesidia clearly continued to operate into the later second century AD; there was limited evidence at a few of the stations of late Roman occupation and activity.

One specialist on the Roman military allots 5 to 6 square meters for each legionary, 2.84 to 3.82 square meters for each auxiliary and six square meters for each cavalryman in a typical Roman camp environment, while another scholar suggests between 2 and 4.5 square meters per man. As we know from the ostraca, the praesidia on the Myos Hormos-Nile road also accommodated women and children, however, which makes the calculations of these archaeologists somewhat artificial. Nevertheless, in the praesidium of Maximianon (which measures overall in its interior space 51.22 by 51.8 meters) estimates range of a garrison strength of 28 to 42 men (a turma-unit-of cavalry was 30 to 32 men) to calculations at the low end of 15 to 17 men.

Quseir al-Qadim/Myos Hormos

At the port of Quseir al-Qadim (ancient Myos Hormos) a large multipleroomed area, excavated by the American team in the late 1970s and early 1980s and dubbed the Indian quarter (Fig. 10.5), preserved evidence suggesting that people often lived, manufactured, and sold wares or conducted their businesses in the same location. Continued excavations by a British team between 1999 and 2003 revealed much additional information about this emporium. The ancient name was definitively proven to be Myos Hormos, thus ending a lengthy scholarly controversy. The British excavators believed that the number of inhabitants varied seasonally, but when ships were in port, there was an estimated population of about one thousand, perhaps somewhat more.

Berenike

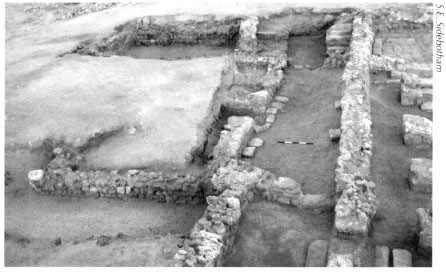

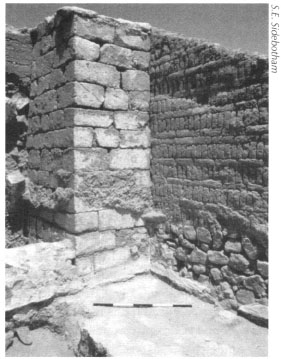

At Berenike in the so-called late Roman (late fourth-fifth century AD) commercial-residential quarter, located between the Serapis temple and the church, it was clear that the large multiple-storied structures dominating this portion of the city had a dual function (Figs. 10.6-10.7 and Pls. 10.5-10.6). The ground floors were areas where business was conducted while the upper floor or floors, which had collapsed upon the lower, were rooms where domestic activities took place. Pottery from these upper floors was invariably coarse cooking crockery or finer tablewares used for dining; these types of pottery are prime archaeological indicators of domestic activities This arrangement of public work and business areas on the ground floor and domestic-residential areas on the upper stories of a building was quite common throughout the classical Greek and Roman Mediterranean world and typical of ancient Egyptian town life as well.

Fig. 10.5: The large multiple-roomed area at the port of Quseir al-Qadim, dubbed the ‘Indian Quarter.’ Scale = one meter.

Fig. 10.6: Structure in the late Roman (late fourth-fifth century AD) commercial-residential quarter at Berenike. Scale = one meter.

Fig. 10.7: Structure in the late Roman (late fourth-fifth century AD) commercial-residential quarter at Berenike. Scale = one meter.

Other domestic areas at Berenike included the Christian ecclesiastical building at the eastern edge of the city (Fig. 10.8), which we discussed in Chapter 6. We excavated inside this large structure between 1996 and 2001 uncovering the entire church as well as areas where cooking and other domestic activities took place. The church lay in the southern area of this ecclesiastical compound while a large east-west running corridor separated it from the northern side where a great deal of food preparation took place; one of these rooms preserved an amphora in situ with remains of numerous tiny anchovy bones, tell-tale evidence that the jar once contained a pungent fish sauce known to the Romans as garum. Although we have not completed excavations in the northern area of the Christian ecclesiastical complex, we suspect that we will also find living and sleeping facilities connected to the food preparation rooms. The amount of space for these putative living and sleeping areas in the unexcavated portions of the complex suggests that a relatively small number of people actually lived here compared to the rather extensive kitchen facilities we have uncovered. Perhaps the food preparation areas were not solely for use by those residing here, but also accommodated others living elsewhere in the city who participated in church activities.

Fig. 10.8: Domestic area of the Christian ecclesiastical building at Berenike (left of photo scale). Scale = fifty centimeters.

Early nineteenth century visitors to the ruins of Berenike attempted to estimate its ancient population. G.B. Belzoni, who discovered the site in 1818, calculated that there were about two thousand houses and arrived at a population of about ten thousand, whereas a few years later J.R. Wellsted figured between 1,000 and 1,500 houses with a population of about five thousand. These figures seem rather too high. There is no way to estimate populations of the Ptolemaic and early Roman communities at Berenike as so little of either has been excavated and no recognizable domestic architecture identified from these early periods. The best known epoch of Berenike‘s eight-hundred-year-long history is the late Roman, beginning in the middle of the fourth and extending into the fifth century AD Based upon what we have excavated and calculating the numbers and sizes of rooms enclosed by the tops of walls of unexcavated structures, which are certainly from this late period, we propose a rather modest population for the late Roman city of about five hundred, perhaps upward of one thousand people or somewhat more. Since all the ancient written documents and the limited archaeological evidence we have recovered from Berenike suggest that the port was at its zenith in the early Roman period, that is, the first century AD, the population of the city then, especially when ships were in port during the times of year allowed by the monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean, would have been somewhat greater than in the late Roman city.

Settlements with Unknown Functions

Our surveys have identified over a dozen settlements with an unknown, but possibly Christian ecclesiastical function (Fig. 10.9).We investigated five of these in detail between 1996 and 2000. It was evident that these communities had originally been larger; but floods have washed away an unknown number of structures over the intervening centuries.

Determining population sizes by examining extant ancient cemeteries associated with these settlements proved impossible as we noted very few graves with no assurance that even those were directly affiliated with any of these communities. Determining numbers of residents by available water supplies was also hindered by lack of any visible evidence of sources or quantities of water that would have been accessible to those dwelling there.

Fig. 10.9: Map of settlements with an unknown, but possibly Christian, ecclesiastical function.

Given all these limitations, however, we estimated the populations of the following: Bir Handosi with 47 structures surviving accommodated perhaps 50 people, Qaryat Mustafa ‘Amr Gama with 109 extant structures housed 122 persons, Bir Gidami with 119 structures contained 131 people, Umm Howeitat al-Bahari with 126 structures accommodated 149 souls, and Hitan Rayan with 141 structures housed 176 individuals. Given their sizes, most rooms capable of human habitation could have accommodated one or occasionally two people and we see a rough parity between the number of structures and number of people at each of these sites at 1:1 with slightly more people than structures. This was probably somewhat different at other desert settlements preserving structures similar in appearance and size to those of these putative Christian communities regardless of when these other settlements would have functioned and what activities may have been associated with them, The ratio of buildings to people may have been greater in gold mining areas as they would have consumed more water and used more structures for the various phases of the gold mining process thereby leaving less water and fewer structures for human domestic activities.

Construction of Houses in the Roman Period

Most settlements in the Eastern Desert were difficult to access from the Nile. Although dragging building materials from the Nile Valley to the desert was occasionally undertaken, most structures erected in the Eastern Desert comprised materials available in the immediate neighborhood, especially unshaped cobbles and small boulders dry-laid or erected using mud mortar. The absence of abundant water supplies in the Eastern Desert made large-scale use of bricks, by far the most important building material for houses, palaces, and forts in the Delta and the Nile Valley, a rare phenomenon. We do have, however, a number of examples of mud-brick architecture especially at the fort at Abu Sha'r (Fig. 10.10), and in some of the praesidia on the Abu Sha‘r/Mons Porphyrites-Nile road at Deir al-Atrash and at al-Heita. Fired brick is rather more common than might be expected, used in some quantity in hydraulic installations, especially water catchment basins. These fired bricks were, likely, imported from the Nile Valley.

Fig. 10.10: Mud-brick architecture at the fort at Abu Sha'r, Scale = one meter.

Some of the Ptolemaic and Early Roman walls of the buildings in Berenike were made of sand bricks and limestone, which were rarely used in late Roman times in the city. The walls of the buildings of late Roman Berenike, on the other hand, were mainly constructed of layers of ancient softball-to basketball-sized coral heads (Fig. 10.11) reinforced with wooden beams. The coral was obtained from nearby fossilized reefs, while most of the wood, much of it teak, likely came from wind-and sea-damaged ships requiring repair. Also used, on a much lesser scale, were cobbles found on the desert plain and blocks of gypsum and anhydrite quarried from nearby Ras Banas. Some of the gypsum/anhydrite blocks were recycled from earlier buildings in the city. These blocks tended to be used as corner stones in buildings or in staircases. In the case of the church at Berenike these blocks were recycled as benches (Fig. 10.12).

In the desert area surrounding Berenike, on the other hand, building materials were very different from those used in the city. The desert installations in Wadi Kalalat, Siket, and Hitan Rayan, for example, were built of naturally occurring hard stone cobbles and small boulders, obtained from the surrounding wadis and nearby mountains. Even deeper in the desert, in the settlements of Shenshef, Sikait, and Nugrus as noted above, walls were almost exclusively made of the stone slabs quarried from the steep hill sides of the wadis. When water was available in reasonable amounts, walls were plastered with mortar or a sandy render.

Windows were usually set high in the rooms. In general elsewhere in the Roman Empire, windows in houses on the ground floor were small and had wooden, terra-cotta, stone, or iron grilles. The smaller ones had wooden shutters. Probably all windows in the Eastern Desert houses had shutters of some sort, to minimize the effects of sun and wind and keep out as much blowing sand and dust as possible. Glass windows were also known. We found window glass associated with the extramural bath at the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r. There were a few fragments of windowpane glass found at Berenike as well. Other materials might also have been used for windowpanes, as was the case elsewhere in the Roman world.

Fig. 10.11: Detail of a wall constructed of coral heads in a late Roman building at Berenike.

Fig. 10.12: Benches in the fifth-century church at Berenike. Scale = one meter.

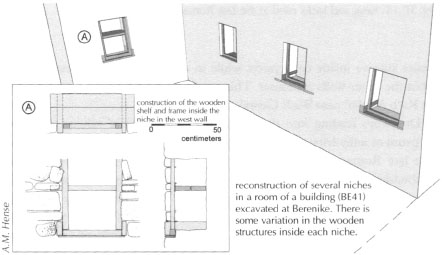

Wall niches (Figs. 10.13–10.14)were a common method to create cupboards. Some of the niches in the houses of late Roman Berenike were lined with small gypsum/anhydrite blocks, as was also the case in the fifth century church at the eastern end of the town. In other examples in Berenike in the Late Period the niches had wooden shelves and a wooden frame, which sometimes supported small wooden doors. In other Eastern Desert settlements shelves of stone were used to save wood. Good examples of the latter appear at Sikait, Shenshef, Nugrus, and in the recently destroyed praesidium in Wadi Semna near the hard stone quarries in Wadi Umm Wikala (Mons Ophiates).

We even know what was placed in some of these niches. In one of the houses of Berenike a wooden box containing large bronze nails was excavated, while those in the church had oil lamps for illumination. Several of the houses in Berenike had niches associated with the staircases. In these examples it is very likely that they contained oil lamps as well.

Except for the eastern end of the church, all floors thus far excavated at Berenike have been made of beaten earth; most houses in desert settlements also had the same type of flooring. Elsewhere in the Eastern Desert only some of the more important edifices, like the so-called administration Building and the large rock-cut temple in Sikait, had stone paved floors. Floors of the upper stories of the houses of Berenike had to be relatively lightweight by necessity, because the supporting walls were not very stable. These upper floors consisted of a more complex construction, using timber and matting supported by rows of wooden beams.

Roofs of some buildings in Berenike, Abu Sha‘r, and Myos Hormos, consisted of organic materials, such as wooden beams and layers of palm ribs, matting, or reeds covered with mud plaster. We excavated large roof beams approximately four meters long in late Roman houses in Berenike. We also found wooden roof beams collapsed onto the floors of some of the buildings in the late Roman fort at Abu Sha'r. As mentioned above, Sikait, Nugrus, and Mons Claudianus preserve some rooms and buildings roofed with stone slabs.

Staircases in Berenike consisted of gypsum/anhydrite ashlars, a number of which had been recycled from earlier buildings. In some cases, these lower stone stairs likely served as supports for wooden ladders or staircases. Sometimes in the Eastern Desert settlements, complete stone-built stairs survive inside courtyards, while in at least one other location they abut the outer walls of houses. This can be seen in some of the buildings at Ka‘b Marfu‘ near Wadi Gemal.

Fig 10.13: Niche in building in late Roman commercial-residential quarter in Berenike. Scale = twenty centimeters.

Fig. 10.14: Reconstruction of niches in a building in late Roman commercialresidential quarter in Berenike.

Fig. 10.15: Keys and locks used at the late Roman Berenike buildings.

Doorways leading into the streets had thresholds of ashlars made of gypsum or anhydrite; wooden beams supplemented some of them. One of the late Roman Berenike houses had a threshold with a bronze pivot embedded in it. Bronze facings of locking mechanisms found both at Berenike and Sikait suggest that security of the house was deemed very important. Several doors in late Roman buildings at Berenike were built or strengthened with bronze nails. There were a couple of options for locking the doors, sometimes used in combination. Locks with copper alloy or iron keys (Fig. 10.15) could be supplemented with horizontal bars and wooden props.

It is clear that the study of domestic architecture and the concomitant estimation of population sizes of various settlements in the Eastern Desert and along the Red Sea coast in antiquity are in their infancy. Additional excavations must take place to identify-more accurately than surface surveying can accomplish-the layout, construction methods and materials, location, and numbers of domestic dwellings. Crucial to the problem of estimating the sizes of ancient populations would be identification and quantification of available water sources at different periods in history; estimation of population from extant funerary remains, most of which are badly looted (Chapter 8), is clearly not an approach that, by itself, will achieve any satisfactory results. If in the future, however, we combine counting structures and their sizes in each community, estimating water availability and consumption for each, and using the paltry funerary evidence that does survive, we might begin to arrive at population estimates for some of the Eastern Desert settlements at different periods.