The Southernmost Sites in the Eastern Desert

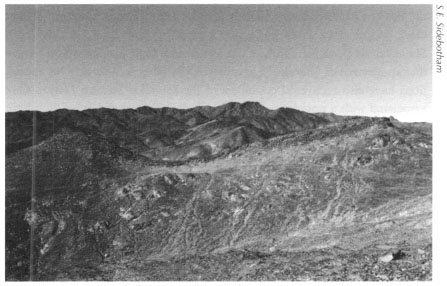

The extreme south is the least known and, therefore to us, the most intriguing part of the Eastern Desert (Fig. 15.1). Compared to the northern regions, this area is even more inhospitable, the water sources scarcer, the terrain more unforgiving, and the heat more intense. Due to these impediments, and the need for special and difficult-to-obtain military permits, this part of the desert has been little explored. Some hardy Westerners ventured into this arid landscape in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and recorded their encounters with the Bedouin. To their surprise, they saw many traces of ancient human activity, ranging on the one hand from drawings and doodlings on rock faces, and broken pottery to settlements, fortifications, and temples on the other. Certainly, of all the vast stretches of the Eastern Desert, this hauntingly beautiful region offers the greatest future potential to reveal new archaeological remains, sites that until now are known only to the local ‘Ababda and Bisharin Bedouin.

European explorers during the past 170 years or so have discovered that people lived in the southernmost areas of the Eastern Desert beginning from at least six thousand years ago. Finds of pottery indicate that groups of nomads and hunters in the late Paleolithic period left the Nile Valley, at least temporarily, and traveled to Abraq if not farther afield. Petroglyphs depict cattle and boats the Nile Valley inhabitants used to navigate the river.

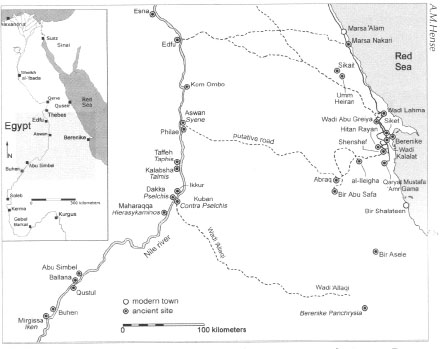

Fig. 15.1: Map showing the location of the southernmost sites in the Eastern Desert mentioned in this chapter.

Around 3500 BC in Lower Nubia, the area south of Aswan up to the Second Cataract, people of the so-called A-Group emerged. Possessing a culture distinct from contemporary Egypt, from about 3200 BC onward they were middlemen in the exchange of exotic goods between Egypt and the far south. Along the trade route through Lower Nubia gold, ivory, incense, ebony, and panther skins streamed into Egypt. Nubia itself produced large quantities of cattle, something that remained an export from the region for thousands of years to come.

Activity during this time increased substantially in the Eastern Desert, as remains of hundreds of tumuli found in the region south of Abraq and many rock drawings in the same area indicate. The cemetery of Bir Asele shows more organized types of burials. As we pointed out in Chapter 8, parallels for this Predynastic (before about 3000 BC) cemetery are known from the Sinai, which makes it less likely that a local group constructed it. On the other hand, all pottery finds from the Bir Asele cemetery are of Nubian style. Pharaonic Egyptians greatly preferred burial in the Nile Valley. Perhaps these graves in the Bir Asele necropolis belonged to some group of individuals, cooperating in extensive mining or commercial operations in the region.

Over four centuries following the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in about 3000 BC, the early pharaohs undertook a series of military campaigns against the population in Lower Nubia. A victory inscription of King Sneferu (2575–2551 BC) of the Fourth Dynasty, father of Khufu (2551–2528 BC) the builder of the largest pyramid at Giza, describes an Egyptian military campaign, which resulted in the capture of thousands of prisoners and the removal of one hundred thousand head of cattle. The kings of the early Egyptian dynasties took full control of the resources and trade of this southern region, which probably caused a drastic decline in the economy of the A-Group people. Combined with climatic changes, this economic collapse resulted in a sudden depopulation of the area, which allowed the Egyptians to move in. Settlements and trade posts, like the fortified town of Buhen, were built to control direct commerce with the far south. As happened many times in the coming millennia, Egypt lost control of the area in the second half of the Fifth Dynasty (2465–2323 BC) and retreated north of the First Cataract. The decimated population quickly recovered, probably assisted by an influx of settlers from the south. This new cultural phase, called the C-Group, established small kingdoms and chiefdoms along the Nile. The C-Group people built mud-brick huts and placed their dead in low, round burial mounds. In addition to the fine red pottery comparable to that made by their predecessors, they also produced polished black and gray dishes and bowls, decorated with colored geometric patterns. Most of the wealth of these C-Group peoples was based on cattle breeding, as reflected in the many clay figurines of bulls and cows, and the burial of sheep, goats, and oxen with the deceased.

Around 2200 BC the names of the small kingdoms and chiefdoms emerged in autobiographical texts recorded in the tombs of Egyptian high officials. Directly south of Aswan, the small states called Wawat, Irtjet, and Setju had somewhat uncomfortable relations with their huge northern neighbor (Fig. 15.2). These chiefdoms are clearly described as “foreign lands” in inscriptions in the tomb of Harkhuf, the governor of Upper Egypt. These texts contain an account of the travels of Harkhuf, who led several expeditions to the south. The goal of his journeys, each of which took over seven months, was to explore the road to the land of Yam. This relatively large and prosperous kingdom south of the three aforementioned ones had a much friendlier relationship with Egypt. Praised by the pharaoh, Harkhuf brought back from Yam large quantities of exotic goods. His autobiography sums up an impressive list, containing hundreds of donkeys laden with ebony, panther skins, and elephant tusks among many other exotic items. On his last voyage, Harkhuf succeeded in bringing a ‘dancing pygmy’ at the personal request of the boy-king Pepy II (2246–2152 BC).

As we know from the autobiography of Weni, Harkhuf’s predecessor, these chiefdoms provided troops to support the Egyptian army during military campaigns in the far south and north. Because of the fame of its archers, one of the names the Egyptians gave to Nubia was Ta-Seti (Land of the Bow). Another group, the Medjay, inhabitants of the Eastern Desert south of Aswan, also supplied Egypt with soldiers. Medjay, the people of the land of Medja, in about 2200 BC began a long relationship with Egypt, and their soldiers played an important role in crucial events in the next thousand years of Egyptian history.

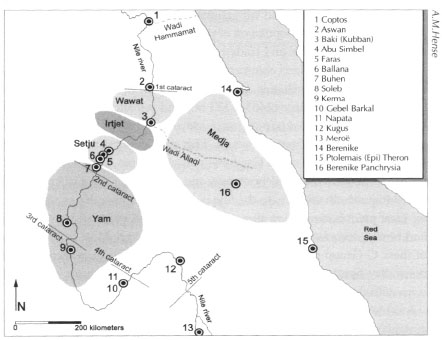

Fig. 15.2: Map with the locations of Wawat, Irtjet, and Setju.

Egyptian expeditions late in the Old Kingdom (2649–2152 BC), searching for mineral resources, trade opportunities, or loot, also entered Nubia uninvited on a regular basis. A rock inscription of governor Weni in the middle of the Eastern Desert, halfway along Wadi ‘Allaqi, some 250 kilometers southeast of Aswan, shows that these expeditions sometimes reached into the heart of the desert.

During a century of chaos, following the end of the reign of king Pepy II, a new state emerged on Egypt’s southern border. The Kingdom of Kerma, called Kush by the Egyptians, had devoured most former chiefdoms, thereby creating a mighty political power that had a less submissive attitude toward Egypt. Moreover, inhabitants of the Eastern Desert occasionally raided settlements in Upper Egypt and robbed travelers. The Egyptian pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom (204–1640 BC) reacted by pushing the border southward during several military campaigns. In earlier times Egypt obtained most of its gold from Wadi Hammamat (see Chapter 4), but as early as the reign of Senwosret I (1971–1926 BC), Egypt began to open gold mines in numerous places in Wadi ‘Allaqi. To intimidate the Kushite rulers, to secure the trade with the far south, and to protect the gold mines in Wadi ‘Allaqi, the Egyptians built eleven massive fortresses at strategic points along the Nile in Lower Nubia. The imposing mud-brick fort that dominated the plain near Buhen clearly had a propagandistic function, with its double walls and enormous towers punctuated with myriads of loopholes for archers. A little south of this fort, the Egyptians built the giant commercial center of Iken. Protected by a stone wall, Iken handled virtually all trade between Egypt and the south. In contrast to Buhen, other fortresses were built specifically for defensive purposes.

For the first time, there also emerged fortifications in the southern part of the Eastern Desert. Wadi al-Hudi, about twenty-five kilometers southeast of Aswan, became an extensively exploited mining area (see Chapter 12). A fort and a fortified settlement were built here to protect the important amethyst mines. There are indications that Wadi al-Hudi was part of the territory of the Medjay. Relations between Egypt and the Medjay were good, as they now served in large numbers in the Egyptian army. A delegation likely of Medjay is reported to have visited the Egyptian royal court, shortly thereafter followed by a Medja prince and his entourage.

Around 1640 BC the Egyptian central government collapsed with the invasion of the Hyksos in the north thereby initiating the so-called Second Intermediate Period. At that time Egypt abandoned its forts in Lower Nubia and withdrew from the region. Egypt was then divided into two parts. As the Hyksos ruled the north and controlled vassal kings in Middle Egypt, only the south remained under independent Egyptian kings based in Thebes.

In about 1560 BC the Hyksos tried to invoke the help of the Kingdom of Kush to destroy what remained of independent Egyptian territory. A letter in which this cooperation was proposed was, however, intercepted and brought to the Theban king. After the defeat and expulsion of the Hyksos, this epistle probably served as a casus belli to deal with the Kushites. Systematically, Egypt conquered the territory of Kush culminating in about 1502 BC in the complete destruction of the capital at Kerma. The conquest of Nubia was completed during the reign of Thutmose II, around 1480 BC. Some old forts were restored and new ones were built in the vicinity of the Fifth Cataract. Egyptian settlers, soldiers, officials, and merchants resided in small settlements spaced along the Nile. The gold mines in the interior delivered the main wealth to New Kingdom Egypt. Those in Wadi ‘Allaqi were then in their heyday, which lasted until the end of the reign of Ramesses II (1290–1224 BC). Estimates suggest that these mines produced over eighty-five percent of all of the gold used in New Kingdom Egypt. Many rock inscriptions left by scribes, soldiers, and officials are evidence of the extensive traffic through this long wadi leading deep into the Eastern Desert. To make those travels far into the arid region possible, deep wells had to be dug. We discussed some of these in Chapter 13.

The Viceroy of Kush, usually a close confidant of the pharaoh, was administrative head of the huge Nubian region. The territory seems to have been divided into districts. On the walls of his Theban tomb, Viceroy Huy, a contemporary of Tutankhamun (1333–1323 BC), receives three ‘Chiefs of Wawat’ and six‘ Chiefs of Kush.’ During the rule of the Viceroys, temples were built at Abu Simbel, Soleb, and Gebel Barkal, and many other places. Egyptian control over Nubia rapidly ceased after the reign of Ramesses II, although the Egyptians managed to retain the strategic town of Baki until the reign of Ramesses X (1112–11 00 BC). With the collapse of Egyptian power, the mines in Wadi ‘Allaqi were abandoned, and a considerable number of the inhabitants, both Egyptian and native, gradually drifted back to Egypt.

Again, there emerged an unknown number of independent kingdoms, which slowly resumed their intermediary role in the trade between Egypt and the south. As excavations have demonstrated, there was a drastic change in burial customs of the local chiefs. Even during Egyptian occupation in the New Kingdom, most of the local elite retained the traditional practice of placing the dead in burial mounds. But in the ninth century BC, the elite started to build small pyramids with offering chapels. The deceased were mummified and placed in stone sarcophagi in large burial chambers underneath the chapel. The cause of this sudden change is unknown, but it may be that missionary activities of Egyptian priests of Amun, who fled the civil war in Egypt, had something to do with it.

In approximately 780 BC, all of Nubia was united in the Kingdom of Napata, with Meroe as capital. King Piye of this powerful new state succeeded in 730 BC in adding to his territories most of the weakened and divided Egyptian provinces, up to the Nile Delta. Piye and his successors of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty presented themselves as Kings of Upper and Lower Egypt. They also restored and expanded numerous dilapidated Egyptian temples, both in Egypt and in Napata. But some fifty years later the Assyrians, who had invaded Egypt in 671 BC, drove king Taharqa back to Napata. After several military campaigns the end came with the destruction of the town of Napata in 593 BC by pharaoh Psamtek II (595–589 BC) of the revived Egyptian state.

Thereafter, Napata began to orientate itself increasingly toward the south and gradually lost its Egyptian influences. This new direction can be seen most dramatically in the written language; a Meroitic script, which has still not been deciphered, replaced the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Eventually the Kingdom of Meroe emerged with its capital at Mereë city. This metropolis served both as a religious and administrative center. In the fifth century BC the Greek historian Herodotus records an espionage mission of so-called Fish-Eaters sent by the Persian King Cambyses to the Kingdom of Meroe. In his account of the ‘Fish-Eaters,’ who were inhabitants of the Nile banks near Elephantine, Meroë is described as a fairy tale-like city, inhabited by the most pious and longest-living people in the world. A well in the city produced flower-scented water that extended the life of anyone who drank it. Prisoners were put in irons of gold, and the dead were buried in transparent coffins of crystal.

After the New Kingdom (ended 1070 BC), mining and commercial activities in the southern portion of the Eastern Desert rapidly declined. It was not until the third century BC, in the Ptolemaic period, that some mines and trade routes were re-opened. In 275 BC, King Ptolemy II sent a large army into Nubia to recapture the long-lost gold mines of Wadi ‘Allaqi. In this region the settlement of Berenike Panchrysia was built, creating the southernmost town of Ptolemaic Egypt now known. More hostile actions followed back and forth, until a peace treaty at the end of the century improved relations. Egypt maintained control of the gold mines in Wadi ‘Allagi, and trade between Meroë and Egypt rapidly increased.

Meroë exported ivory, spices, hides, and wild animals to Egypt. Major discoveries of iron deposits around the capital led to a substantial iron industry; the Kingdom of Meroe had yet another highly prized export article. In return for these products the Meroites received Hellenistic manufactured goods as well as wine, grain, and olive oil. Hellenistic designs were adopted and modified according to local taste in architecture, pottery, and stone carvings.

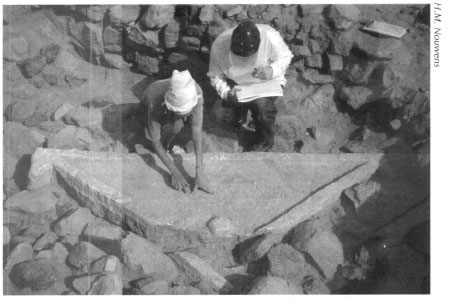

The fort of Abraq sits on a flat plateau, overlooking a large wadi along what seems to be the southernmost Ptolemaic trade route to the Red Sea coast north of Meroë (Pls. 15.1-15.2). This massive fortress, over 160 meters wide, may have been built to protect a trade route; the nearby well was probably the main reason for the location of the stronghold. Pictographs and graffiti, which include gazelles, elephants, cows, camels, warriors on horseback, and Christian crosses cover large boulders and the wadi walls near the well.

The fortress was built on a bluff that rises over fifty meters above the wadi floor. Where the bluff has a gentler slope, and is easier to climb, the outer defensive wall is over two meters thick and four meters high. In the center of the fortress, a natural rise of the rock facilitated construction of a citadel, some six meters above the level of the outer wall on the wadi side. This central building has twenty-eight rooms surrounding a large courtyard. Smaller buildings were constructed inside the outer southern wall, and at the southwestern corner a large tower once overlooked the entrance path to the fort. This path zigzags on the steep western side of the rock from the wadi floor to the entrance gate, close to the central building.

Early travelers like the Frenchman Linant de Bellefonds, who visited the fort at Abraq in 1832, and the American Colston who saw it about twenty years later, considered the stronghold an elephant hunting station. It is, however, unlikely that elephants were hunted here in the Ptolemaic period, when environmental circumstances in this area closely resembled those of the present day. It is plausible that the elephants depicted near the well are memorials of travelers coming from the south, or even records of animals imported from the south and passing Abraq en route to the Nile Valley.

An ancient trade route from the Red Sea port of Berenike, probably leading to Aswan via Abraq, once passed by the gold mines at al-Ileigha. Gold was extracted from large open pits here for the first time in the Ptolemaic period. On the hills surrounding the mines are stone foundations of simple huts, which are still visible. A large housing complex was probably the core of the fairly large settlement. The date of the buildings is still unclear; in addition to pottery of the Ptolemaic period, survey work has recovered quantities of Islamic shards dating ninth to the eleventh centuries AD.

During the Roman period, military units from various parts of that Mediterranean-wide empire were stationed in Egypt. There was a good reason for bringing foreign units, some of which had to travel thousands of kilometers. To avoid loyalty problems during revolts of the local population, non-Italian auxiliary troops were often sent to regions far from their homeland (Pl. 15.3).

The total Roman force in Egypt varied over time, but at its peak in the first century AD it comprised three legions plus auxiliaries totaling about twenty thousand troops, a number that was probably somewhat larger in the fourth century AD. Mounted soldiers with horses, and later camels, became more important as the numbers of raids and attacks by desert tribes increased and Roman forces had to react quickly over great distances. The large-scale breeding of camels in the second century AD gave the Romans a mount more adapted to the desert. The effect of this new ‘vehicle’ was a somewhat mitigated by the fact that within fifty years the marauding desert Blemmyes started to use the camel as well.

The bow was an important weapon for desert troops and excavations at Berenike and Sikait produced many types of bronze and iron arrowheads. Palmyrene troops, as we have seen in Chapters 6 and 7, had garrisons in both Berenike and Coptos in the early third century AD and inscriptions indicate that some of these were archers. This comes as no surprise as Palmyra, a desert caravan city in Syria, was famous for its mounted archers. These specialized troops would have been ideally suited to protect the important trade routes in Egypt’s Eastern Desert. What better locations to station them than at the terminal points of one of the most important desert roads: that linking Berenike to Coptos?

So far, a cohors Ituaeorum is the only unit whose presence near Berenike during the first century AD can be archaeologically proven. A fragmentary papyrus dated to the reign of Nero (AD 54–68), and found in our excavations at Berenike, records an official contract or dispute in which one of the parties served in this cohort. The Ituraeans, originating from northeast Palestine, are known to have served in various military units in Egypt and elsewhere in the Roman East. Another text found in Berenike shows the presence of two officers of the ala Thracum Herculiana in late second or early third century AD Berenike. The nominal size of an ala quingenaria was five hundred horsemen, while that of an ala milliaria was upward of one thousand in the first century AD. In Egypt, however, cavalry were dispersed over the area in smaller units, sometimes as small as thirty to sixty horsemen or camel riders.

As we noted in Chapter 7, some personal names of military men are known through documents recording their transactions, again at Berenike. The commander, Tiberius Claudius Dorion, for instance, was a successful businessman in addition to being a soldier. Notes of a Roman customs office written on ostraca during the first three quarters of the first century AD and found in a Roman trash dump in Berenike indicate that he ordered shipments of trade goods at least sixteen times.

With the enormous upsurge of activity in the southern area of the Eastern Desert in the Roman period came the need to protect the re-opened mines, trade routes, and Red Sea ports like Berenike. Several measures were taken. Garrisons were stationed in posts from Aswan to Berenike. The Romans constructed forts near the towns in the Dodekaschoinos. These included auxiliary forts on the east bank of the Nile opposite Taphis, Talmis, and especially at Pselchis, where the western entrance to the Wadi ‘Allaqi had to be protected. Near the Red Sea port of Berenike fortifications were built on the plain west of the city.

The approaches to Berenike were very heavily guarded. Thus far, ten forts have been documented within a thirty-five-kilometer radius of this large Red Sea emporium. In addition to the two nearby forts in Wadi Kalalat there was also, only about 7.2 kilometers to the west-northwest, another small praesidium at Siket, and some twenty-five kilometers to the northwest, five more forts in Wadi Abu Greiya (ancient Vetus Hydreuma). These plus a hill top fort at Shenshef and another fort in Wadi Lahma, which may have fallen out of use before early Roman times, guarded the northern road leading to the port. Berenike probably had its own garrison as well. This substantial military presence may appear to be ‘overkill’ to the modern visitor. Besides the sporadic encounters with snakes and scorpions any major danger seems unthinkable here in antiquity, without vehicles, paved roads, or sufficient water resources. The dangers in Roman times were real, however, and sometimes army-sized. In addition to pirates roaming the Red Sea, and small bands looking for caravans to loot, now and then large armies entered Roman territory. The Roman authorities did not soon forget the devastating attack of a large Meroitic army less than a decade after Egypt became part of the Roman Empire in 30 BC.

The Roman garrisons in the southern part of the Eastern Desert were housed, as was the case throughout the region east of the Nile as a whole, in fortifications. The dimensions and plans of the structures varied greatly, and depended on the functions and sizes of the garrisons. The large praesidium in Wadi Kalalat, with its giant hydreuma, measures about 80 by 90 meters. The small praesidium at Siket, about 7.2 kilometers west northwest of Berenike, with a hydreuma in its center, on the other hand, measures only approximately 24 by 32 meters. The fort at Siket provided Berenike with some water and also protected the considerably less dangerous northern approaches to the city. The strength of the contingent at Siket was probably not more than ten men who were undoubtedly sent out in rotation from nearby Berenike, whereas we estimate that the garrison size in the large praesidium in Wadi Kalalat may have been several score soldiers.

Our excavations and those of others have produced much evidence of military presence in the southern parts of the Eastern Desert. Egyptians, Greek mercenaries, Romans and their many auxiliary troops, Blemmyes and other desert tribes all had specific weaponry. This is the reason so many different types of arrowheads, the most common type of military equipment, are found in excavations. Besides the bronze flat arrowhead with two barbs, more complex ones of iron have been unearthed at Berenike, at the emerald mining site of Sikait, and at forts in their environs. This type of arrowhead was already used in pharaonic times. The more complicated arrowheads, with three or four blades, were fairly common in the Roman arsenal and are ubiquitous on military sites all over the Roman Empire. Similar arrowheads have been excavated, for example, in the limes areas of Scotland, Syria, and Palestine.

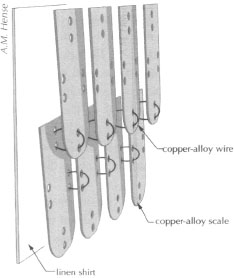

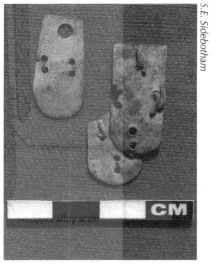

Scale armor is another indication of the presence of soldiers. Excavations have recovered parts of iron and bronze scale armor at both Sikait and Berenike. These scales were linked together with small bronze rings, and attached with threads to a thick linen shirt. Scale armor was relatively simple to produce, but required a great deal of maintenance. Especially in the east, soldiers wore scale armor throughout the early and late Roman periods (Figs. 15.3-15.4), alongside the more flexible chain mail.

Even some units of Roman cavalry became heavily armored. From the later second century AD on, Rome increasingly put into action more and more heavily mailed cavalry, the cataphractarii and clibanarii. Both the men and their mounts were covered in a complex combination of chain mail, plate armor, and scale armor. It is unlikely that cavalry like this was ever used in the Eastern Desert, in view of the rough terrain, the heat, and the enormous weight of this type of armor. It is more probable that the scale armor belonged to the equipment of the lighter armored horse- or camel-archers. These mounted archers formed the bulk of the late Roman armies, especially in remote border territories like the Eastern Desert.

Fig. 15.3: Construction of scale armor.

Fig. 15.4: Bronze scale armor found in Sikait (fourth-fifth century AD). Scale = five centimeters.

The installations in Wadi Kalalat indicate that both dangers and available numbers of soldiers dictated the size of the forts. In the late second century AD the larger fort (see Chapter 13) was abandoned and a new smaller one was built less than a kilometer to the northeast (Fig. 15.4).This latter structure measured only about 30 by 40 meters. Although the dangers had grown, the number of soldiers was reduced below a level that made the defense of the large fort either unnecessary or impossible. On the other hand, this might also indicate that the emphasis in garrison composition had shifted to mounted troops and that the main body of the horse- and camel-soldiers was now stationed closer to or in Berenike itself. That the small fort in Wadi Kalalat was more focused on defense is shown by the remnants of a low rampart, which once surrounded it. Roman forts in northern areas of the empire where the ground was more solid were surrounded by one or more ditches, which made attackers more vulnerable to the missiles of the defenders. In the loose and dry soil of the Eastern Desert, digging a trench around the fort would have undermined the walls. A low rampart five to ten meters distant from the outer perimeter enceinte of this smaller fort, with a steep angled inside and a gentle slope on the outside, created the same effect.

The typical Roman fort in the Eastern Desert usually, but not invariably, had a rectilinear ground plan. Larger ones had a tower attached at each corner and sometimes along the walls between the corner towers themselves. Towers of similar size flanked the main gate of the larger installations. Large forts that had intermediate towers along the walls did so at intervals usually not greater than forty meters. This was necessary to provide archers and javelin throwers with good fields of fire up to the foot of the wall, and to protect it against undermining, or more likely scaling, by enemy troops. Staircases at the inside corners of the perimeter walls provided access to the walls and towers.

Larger forts like the one in Wadi Kalalat also had staircases or ramps leading up to catwalks and parapets. Walls and towers were of the same height, usually about four to five meters, and were built of locally gathered, unworked cobblestones and small boulders. Only crucial parts, like the lintel, doorposts, and threshold of the main gate, were made of large hewn stone, in the case of those near Berenike usually gypsum or anhydrite, brought from nearby quarries. In addition to this, at least some forts near Berenike had monumental inscriptions above their main gates. The inscription over the entrance of the fort at Siket was found almost intact (Figs. 15.5-15.6 and Pls. 15.5-15.6). It was inscribed in a massive carefully crafted triangular shaped stone, almost 2.5 meters wide and 1.07 meters high, and according to the Latin text, the construction took place in year nine of the reign of the Roman emperor Vespasian (AD 76/77). The inscription fragments found at the main gate of the large praesidium in Wadi Kalalat, carved in Greek rather than Latin, identified the builder as Servius Sulpicius Similis, Roman prefect (governor) of Egypt in the early second century AD during the reign of the emperor Trajan (AD 98–117). Similis was also actively involved in other building projects in the Eastern Desert.

Fig. 15.5: Fallen columns that once supported the inscription over the gate of the praesidium at Siket.

Fig. 15.6: The inscription block from the praesidium at Siket, just after excavation.

Although the praesidium at Siket is small, much attention was, of course, given to the strength of the gate (Pl. 15.7). Massive stone doorposts protected the edges of the double doors. A large stone with two holes, placed behind the threshold, facilitated locking the gate at floor level. The almost three-meter-high wooden doors probably had handles on the inside for heavy bolts. The doors of the forts in the environs of Berenike were over fifteen centimeters thick, as proven by finds in the gates of the Wadi Kalalat strongholds. Excavations recovered many fragments of iron nails in the gate areas of Siket and Wadi Kalalat. Some of these nails may have served as fastenings for armor plating on the outside of the doors. During abandonment of the forts, the wooden gates were dismantled and undoubtedly stripped of their armor; the timber was, likely, recycled, probably at Berenike.

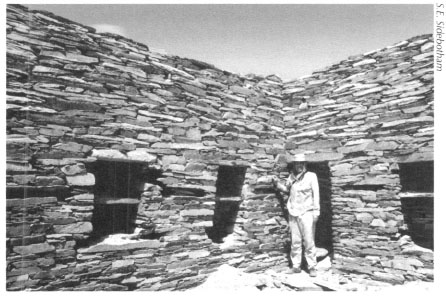

The largest, southernmost settlement built in the Eastern Desert during the Roman period that we know of was in Wadi Shenshef (Pls. 15.8-15.9). This is a late Roman site whose floruit was the fifth to sixth centuries AD. The ruins nestle along the lower and middle slopes of both sides of a wadi of the same name about twenty-one to twenty-two kilometers south-southwest of Berenike and approximately twelve kilometers in a straight line due west of the Red Sea. Several ancient mountain tracks marked by stone cairns, and comprising portions that were artificially built-up and hacked away from the edges of precipices, lead north from the heart of Shenshef to Wadi Kansisrub. From there one ancient desert track heads to Berenike via the two Roman forts in Wadi Kalalat while another leads to the contemporary site at Hitan Rayan, about ten kilometers in a straight line to the northwest. Due to its remote and mountainous location, the last six kilometers leading into Shenshef from the north must be traversed on foot or using camels, horses, or donkeys as it is completely inaccessible to vehicular traffic. Comprising approximately three hundred structures of various sizes and functions, and at least five hundred doughnut-shaped tombs, the bulk of the settlement stretches for about eight hundred meters east-west by 275 meters north-south; in addition there are numerous outbuildings including guard posts, signal and guard towers (skopeloi), and tombs scattered beyond these limits. The better-preserved structures in this wadi settlement survive to heights of two to three meters and include doors with lintels, windows, and interior shelving (Figs. 15.7-15.8).They are built of locally obtained meta-diorite/metagabbro and aplite, the latter quarried nearby.

VLADIMIR SEMIONOVITCH GOLÉNISCHEFF

Vladimir Semionovitch Golénischeff was born in St. Petersburg in 1856. At an early age Golénischeff showed a great interest in oriental culture and ancient languages. When he was only fourteen years old, Golénischeff purchased his first Egyptian object, which was the start of a large collection of antiquities. From 1875–1879 he studied at St. Petersburg University, at the department of oriental languages. Publication of a paper on the subject of a papyrus, which the young scholar had found in the Hermitage Museum, was regarded as a great success.

In 1881 Golénischeff discovered a well-preserved papyrus of the Middle Kingdom (2040–1640) containing the famous “Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor,” a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian literature.

In 1886 he became a curator of the Egyptian department of the Hermitage, where he arranged a catalogue of the museum’s Egyptian collection.

Golénischeff embarked for Egypt for the first time in 1879; during his sixty visits to Egypt he examined the most important archaeological complexes and assembled many antiquities, which were finally sold to the Russian government and transferred to the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow in 1911. Golénischeff's travels also brought him to the Eastern Desert. In the winter of 1884–1885 the Russian Egyptologist carried out an epigraphic inspection of the Wadi Hammamat. He never returned to Russia after the revolution of 1917 and settled in Nice, France. In Cairo where he was cataloguing the papyri in the Egyptian Museum for some time, he became Professor of Egyptology at the University in 1924. He died in Nice in 1947.

Shenshef is the largest, best-built, and best-preserved ancient settlement within a fifty kilometer radius of Berenike. Yet, despite detailed surveying and limited excavations, its raison d’être remains uncertain. Some of the earlier travelers to Berenike were also aware of Shenshef and provided brief descriptions of the remains; they were also puzzled by what function the site may have had. R.E. Colston in 1887 and G. Daressy in 1922 thought Shenshef was an Arab village and J. Ball in 1912 wrote that Shenshef was “a slave dealer’s stronghold where slaves were herded till they could be shipped to Berenice.” These interpretations are highly unlikely. The best overall description until the 1990s was that of G.W. Murray who published a brief account in 1926. Murray was also intrigued by the purpose of this large settlement in the desert. He speculated that inhabitants from Berenike resided here in the autumn, presumably because adverse winds curtailed sailing at that time of year from the port, but this cannot be substantiated. Murray also believed that Shenshef acted as a warehouse for precious commodities eventually destined for trade through Berenike.

Fig. 15.7: Well-preserved structure in the late Roman-era community in Wadi Shenshef with doors, lintels, and windows.

Fig. 15.8: Interior shelving in one large late Roman-era building in Wadi Shenshef.

The presence of water on or near the surface of Wadi Shenshef in proximity to the settlement for much of the year would have allowed the cultivation of a great deal of food, a fact borne out by the botanical finds and numerous grain grinding stones recovered during our surveys and excavations there. Whether this permitted a high degree of self-sufficiency let alone export of food to Berenike remains to be determined.

Excavations have indicated close contacts between Shenshef and many distant lands by way of Berenike. Imported items such as amphoras from the Eastern Mediterranean, mainly Cyprus and Cilicia in southern Turkey, black pepper from south India, and a sapphire from Sri Lanka arrived at Shenshef via Berenike. Finds of these and other high status artifacts suggest that an element of Shenshef’s population was fairly well-to-do. Our excavations have also recovered quantities of the so-called Eastern Desert Ware, associated with a population from the Eastern Desert of Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia. Perhaps these people were some of the city’s residents.

Overlooking the late Roman settlement of Shenshef, to the east and crowning a high hill about ninety meters above, are the remains of a late first century BC-early first century AD fort that extends—oddly and uniquely for forts in the Eastern Desert—from a hilltop down into a saddle and up to another hilltop (Fig. 15.9 and Pls. 15.10-15.11). Virtually all of the late Roman Shenshef settlement as well as the Red Sea are visible from this mountain redoubt. The presence of a fifth-sixth century AD civilian settlement beneath a fort several hundred years older, and which appears not to have been in operation when the civilian settlement functioned, is an enigma that we cannot explain.

The superbly situated, but oddly shaped fort at Shenshef, with an overall length of nearly 120 meters, appears architecturally to have undergone two distinct building phases. Though it remains unexcavated, certain facts about its use can be understood from examination of surviving surface features. The northwestern-most portion of the fort sits atop a summit that immediately overlooks the later civilian settlement and from which there is also an excellent view of the Red Sea. This seems to be the older and is certainly the smaller of the two sections-measuring 56.1 meters north-south by about 39 meters east-west. This northwestern section has a massive four-meter-wide gate on the west that leads down a steep path to the wadi floor. This northwestern portion also contains virtually all the internal buildings now visible in either fort section; most surface pottery (late first century ac-early first century AD) was also found here.

The later addition to the fort, which extended toward the south-southeast down into a saddle and up to another hilltop to the south, contained virtually no pottery or interior structures; it cannot, therefore, be dated. A portal about 1.7 meters wide, torn through the southeastern portion of the original curtain wall of the northern/earlier fort, joined it to the later addition. Strangely, the walls of the later addition do not actually join those of the earlier. Where they should exist there are, instead, gaps, 1.8 meters wide on the east and 2.32 meters wide on the west, which may have been entrances into the later addition. In both fort sections, walls tended to be thicker than they were high.

Fig. 15.9: Profile of the hilltop fort at Shenshef.

The great differences in dates of apparent occupation of this fort with those of the civilian settlement below and to the west indicate that this hilltop installation was originally positioned to oversee a broad area and was not intended to guard a specific location. There is no indication at this time that the fort, originally occupied at the turn of the Christian era, remained in use when the civilian settlement below functioned four hundred to six hundred years later. Hilltop forts in the Eastern Desert are unusual. Our surveys over the years have identified only about eight of approximately eighty forts in the region that are situated on high ground.

Indigenous Peoples and ‘Immigrants’ in the Eastern Desert in Ptolemaic and Roman Times

From Ptolemaic times on, the Egyptian territory of Lower Nubia regained prosperity as a result of good administration and improved agricultural techniques. The Nile town of Hierasykaminos (Maharraqa) marked the border with Meroitic Nubia. The 120-kilometer stretch of land between Hierasykaminos and Aswan was called the Dodekaschoinos (‘Land of the Twelve Miles’ in Greek). The main goal of Ptolemaic recolonization of Lower Nubia was to facilitate access to the re-activated gold mines of Wadi ‘Allaqi.

Shortly after Rome took control of Egypt in 30 BC, the long period of peace came to an end. The overly ambitious Roman governor Cornelius Gallus forced Meroitic envoys in 29 BC to sign a treaty that made the Meroitic part of Lower Nubia a Roman protectorate. The premature end of the governor, and the military debacle of his successor Aelius Gallus in Arabia, gave the Meroitic king an opportunity to turn the tables. A Meroitic army of thirty thousand men led by Queen Amanirenas defeated the Roman garrison in the Dodekaschoinos, occupied Philae, and looted Aswan. Only six years later a Roman army defeated the Meroitic troops and destroyed their capital, Napata. After renewed hostilities, the Roman emperor Augustus called a peace conference on the Aegean island of Samos. As a consequence, the Romans left that part of the Meroitic kingdom that they had occupied and the border was once again fixed at the town of Hierasykaminos. The following period of peace with Rome brought Meroe a short span of renewed international contacts and trade with Roman provinces, but the kingdom slowly lost its grip on Meroitic Nubia. This area became more or less independent, while the Nobadae and Blemmyes emerged and took control. Farther south the ancient empire of Meroe faded away during the following centuries.

We do not know much about the inhabitants of the southern Eastern Desert in this era of Ptolemaic and Roman history. Those living on the coast were called, understandably, Ichthyophagoi (Fish-Eaters). These people dwelt in scattered caves, according to Agatharchides, who lived in the second century BC, but whose information dates from the preceding century. He further described the Fish-Eaters, who buried their dead under heaps of stones, as not very warlike. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea also lists the Fish-Eaters. Farther inland, according to the Periplus, lived the tribes of the ‘Wild-Flesh-Eaters’ and ‘Calf-Eaters.’

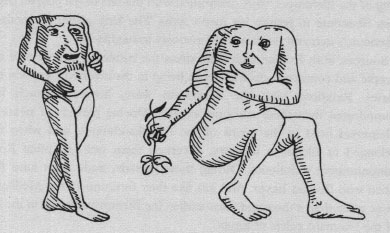

In the third century AD the Blemmyes and Nobadae started to loom large in the texts of ancient classical authors as menacing threats to Roman order, though they were certainly in the region earlier. In this period, the introduction of the camel had transformed their society drastically; previously pastoralists restricted to certain areas, they then became long-range raiders. In the 50s-70s AD Pliny the Elder described the Blemmyes in his Natural History as mythological beings. According to him, a typical Blemmye was headless with eyes and a mouth on his chest (Fig. 15.10). Members of these same desert tribes were characterized in about AD 200 by Julius Solinus, who borrowed much of his information unashamedly from Pliny and Pomponius Mela, as extremely mean, and able to capture wild animals just by leaping on them. The sixth century writer Procopius also recorded the devastation wrought by these tribes in the region.

In AD 250 the inhabitants of the Dodekaschoinos saw that Pliny’s account of the grotesque features of these desert peoples was fanciful. The Blemmyes attacked in this year for the first time the towns of the Dodekaschoinos. Roman troops were able to repel their assaults, but subsequent attacks had more serious consequences. Eleven years after they launched their initial attack, the Blemmyes entered the Dodekaschoinos again, this time overrunning the weakened garrisons completely. Before the Roman general Julius Aernilianus succeeded in driving the Blemmyes back to the First Cataract, they had plundered many Egyptian cities. During the attack of Queen Zenobia of Palmyra in the north of Egypt in AD 270, the Blemmyes conquered the whole of Upper Egypt. Many Blemmyes stayed in the Egyptian towns of Ptolemais and Coptos in peaceful cohabitation with the Egyptians, even after the Romans regained most of their territory. The Dodekaschoinos had to be given up, however, and the Romans permanently abandoned the area in AD 289.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRACES THE

BLEMMYES AND NOBADAE

“Then there is another island, south of the Brixontes, on which there are born men without heads who have their eyes and mouth in their chests. They are eight feet tall and eight feet wide.” (Fig. 15.10). A catalogue entitled Mirabilia Descripta (The Wonders of the East) provides this account of grotesque, deformed people. When this collection of descriptions of people and beasts living in Africa and Asia was compiled in the early Middle Ages, Europe had basically lost all contact with, and with it most of its knowledge of, Africa and Asia. Writers of compilations like The Wonders of the East had to fall back on ancient books. The above-mentioned text was clearly based on the description of the Blemmyes by Pliny, who wrote his Natural History, an attempt to collect all knowledge of his time, in the first century AD. At the time Pliny wrote his encyclopedia, not much was known of the desert people east of the Dodekaschoinos.

Fig. 15.10: Blemmyes. Drawing by A.M. Hense (basedon illustrations in Cosmographia [Basel 1544] by Sebastian, and the Nuremberg Chronicle [1493] by Hartmann Schedel).

This changed only in the third century AD, when an army of Blemmyes attacked Roman territory for the first time. Roman accounts explicitly refer to the Blemmyes in their border conflicts in southern Egypt. Some early Coptic Christian stories also mention local Egyptian fear of the Blemmyes. Such an account we find in the story of the Coptic saint Apa Shenoute freeing prisoners from the raiding Bedouin. It is a wonder story in which Apa Shenoute made the arms of the Blemmyes, who intended to kill him, stiff and inflexible “like dry wood.” Shenoute made his way to the king of the Blemmyes, who, confronted with the fate of his people, begged Apa Shenoute to restore his men’s arms. The king gladly responded to Shenoute’s demand to release all prisoners immediately.

Sources, both Roman and local, stress the ruthless savageness of these people and contrast them with those living in the civilized Egyptian territories. Relations with the Blemmyes were, however, much more complicated than these accounts suggest. During periods of peace, the Blemmyes lived in the towns of the Dodekaschoinos, and when those belonged to Blemmye territory, governed them well, adopting Roman administrative techniques. During these periods, trade must have flourished with Roman Egypt. And just like their forerunners the Medjay had done more than a thousand years earlier, the Blemmyes served in the army of the (Roman) rulers of Egypt.

Although mentioned frequently by their Roman contemporaries, identifiable archaeological traces of the Blemmyes and Nobadae are scarce. We know almost nothing of the Blemmyes in the first and second centuries AD. The Nobadae emerged during the first century AD in the Nile Valley south of the Dodekaschoinos. Until that time, the area was barely inhabited, but by about AD 200 the whole region was covered with settlements. The peoples responsible for the rapid development of the area were first dubbed the X-Group, later identified as the Nobadae; the Blemmyes and other local groups probably supplemented them. The X-Group, and the archaeological remains of settlements and burials, was more recently renamed the Ballana culture, which is the material culture shared by all the inhabitants of Nubia in this period. The Nobadae were organized in a village culture, without monumental buildings such as temples and palaces. The small villages were more or less independent, and governed by local monarchs and officials. The settlements produced agricultural products and cattle, which were bartered among the villages. There was also an important weaving industry in the villages. In trade with Roman Egypt, food was exchanged for luxury goods such as incense burners and glass vessels. The pottery of the Nobadae consisted of characteristic thin-walled and painted beakers and bowls. These delicate vessels are also described as ‘eggshell ware.’ The Ballana culture did not, as far as we can determine, have any wrirten literature or history, but adopted the Meroitic script for administrative purposes. The houses had thick, red-painted mud-brick walls and vaulted ceilings. Windows were placed high in the walls, and stone staircases gave access to the roofs.

The only known monumental structures built by the Ballana culture were the royal tombs near Qustul and Ballana in the third and fourth centuries AD. Mounds, varying in diameter from three to twelve meters and up to 4.5 meters high, crowned many common tombs. The final resting places of the kings and the nobles were far larger, and each had an adjoining offering chamber. The dead were wrapped in a shroud, as was the practice in Meroitic times, and placed on a canopied wooden bier. Most grave goods consisted of locally made pottery, but iron weapons and beads were also common. Moreover, the royal tombs contained bronze lamps, glass vessels, and wooden boxes inlaid with ivory. In one tomb a Ballana king and queen were found wearing large silver crowns. Like the Blemmyes, the Nobadae worshiped the old Meroitic and pharaonic Egyptian gods. Isis, also very popular throughout many parts of the Roman Empire, was one of their most important deities, and her temple at Philae was the main sanctuary for both people until very late in antiquity.

The origin of the Blemmyes is uncertain. They may have entered the Eastern Desert during the early Roman period, but it seems more likely that they largely descended from earlier Eastern Desert tribes. Recognizable archaeological traces of the Blemmyes are still extremely scarce, although finds from our excavations at Berenike and Sikait may be evidence of their presence in the area. In the late Roman period, Berenike and Sikait counted many inhabitants of local origin, as shown by the large numbers of pottery shards of so-called Eastern Desert Ware, a handmade and burnished pottery, found in excavations there. It is still unclear if this pottery belonged to the Blemmyes, or to another, still unknown, desert people.

To keep the Blemmyes at bay, the Romans invited the Nobadae in AD 289 to colonize the Dodekaschoinos. In addition, they gave both Blemmyes and Nobadae permission to visit the Isis sanctuary at Philae. The Nobadae never really succeeded in taking over the whole of Lower Nubia from the Blemmyes. They also never controlled the Eastern Desert and were unable to obtain revenues from the gold and emerald mines there, which were completely in the hands of the Blemmyes. As a consequence, the royal jewelry of the Ballana culture was made of imported silver, rather than Blemmye gold. In AD 392 an edict of the Roman emperor Theodosius I (AD 379–395) proclaimed the closure of all pagan temples, including those of Philae. Confronted with this, the united armies of the Nobadae and Blemmyes attacked and conquered Upper Egypt, which they ruled until AD 452, at which time the Roman general Maximinus defeated them. The peace treaty stipulated that the Blemmyes and Nobadae could visit the temple of Philae again, and resume their worship of Isis. Until the sixth century the Blemmyes ruled over the Dodekaschoinos, and managed to keep this ‘pagan’ enclave, as the Nobadae were Christianized by then, relatively prosperous. The Blemmyes defended their last strongholds south of Aswan until their final defeat in AD 540 by king Silko of the Nobadae. Silko and his successors expanded their kingdom to the First Cataract. By AD 600 the conversion of Upper Egypt and Nubia was complete, and most Nubian temples were transformed into churches.

Even after their defeat along the Nile, the Blemmyes retained control over a large part of the Eastern Desert. The Arab historian al-Taghribirdi (AD 1411–1470) recounts how in AD 854 the natives “of the remotest part of Upper Egypt” refused to pay their yearly tribute of five hundred slaves, dromedaries, and several giraffes and elephants to the Muslim ruler of Egypt. The desert tribes then plundered towns as far as Esna and Edfu. As in Roman days, a large punitive expedition was sent to the south. Although the account of al-Taghribirdi on the battle that followed was probably tendentious, it suggests that the Blemmyes still had a considerable camel corps. The creation of three small Nubian Christian kingdoms followed the downfall of the Blemmyes. The Arab conquest of Egypt in AD 641 brought new conflicts between these southern kingdoms and Egypt, but they succeeded for centuries in warding off occupation. The Kingdom of Makouria achieved friendly relations with the Fatimids in Egypt, and the intense trade with Upper Egypt promoted the prosperity of the land. Faras became the cultural and religious center, while in many places churches and monasteries were built. In the tenth century the Kingdom of Makouria had even gained enough power to occupy Upper Egypt. The heyday of this Christian kingdom came to an end, however, shortly thereafter, and around AD 1300 it was completely overrun by Egyptian Muslims. The southernmost kingdom, Alodia, retained its independence until the fifteenth century.

Enigmatic Settlements in the Eastern Desert

As we noted in Chapter 10, in the course of the fourth and fifth centuries AD communities whose functions have yet to be determined emerged in the Eastern Desert. Although the most spectacular, Shenshef is only one of over a dozen settlements found thus far which cannot be connected to any mine, quarry or road. Some ten kilometers northwest of Shenshef the contemporary settlement of Hitan Rayan was built in a long narrow wadi. The buildings here are much simpler, and are probably the stone foundations for tents or huts of wood, hides, and matting. The structures recall those found at Eastern Desert mining sites. Our archaeological surveys in the area, however, have not detected any mines or quarries. Both Shenshef and Hitan Rayan were built during the latest period of habitation at Berenike in the later fourth, fifth and sixth centuries AD.

Our archaeological survey discovered a settlement in Wadi Umm Arlee (Figs. 15.11-15.12) in winter 1998. This site lies approximately thirty-five kilometers southwest of Berenike and about thirteen kilometers in a straight line west of the Red Sea. We named the remains Qaryat (Village of) Mustafa ‘Amr Gama in honor of the ‘Ababda Bedouin who revealed the site’s location to the survey. The village comprises 109 structures or parts of buildings that extend up two branches of the wadi; it covers a total area of about 240 meters north-south by 390 meters east-west. There are a few doughnut-shaped tombs of ancient date on the surrounding ridges above the wadi. Evidence of water damage sustained over the years suggests that the settlement was originally somewhat larger. Buildings were probably mainly used for human habitation, food storage, and animal pens. The community had an estimated population of 122.

The structures comprising this site include mainly unpretentious small one and two room buildings and a smattering of three and four room edifices that are mainly rectilinear, a few round or oval, in plan. Surviving walls are made of locally available and unworked cobbles and small boulders and average 0.7-1.2 meters high, and only about 0.5 meters thick. In some places natural rock faces form building walls. The low walls and little surviving tumble beside them suggest that they were not originally much higher. Thus, most of the superstructures were probably made of less permanent materials that have long since disappeared, perhaps wooden frames covered by hides, cloth, or mats as is the current practice of the ‘Ababda Bedouin in the area today. Analysis of the site and the surface finds collected there, including pottery and some dipinti painted in red on the shoulders and necks of amphora fragments, indicates occupation in the fifth to mid sixth centuries AD. No definitive identification of the purpose of the site is possible though it might have been one of the many Christian laura communities known from literary sources to have been active in the Eastern Desert at that time. Laura settlements comprised numbers of cells (small rooms) loosely grouped together sometimes, but not always, in combination with a church. Monks and Christian recluses would reside in these communities for varying lengths of time. The recovery of numerous amphora fragments styled Late Roman Amphora 1, made in Cyprus and Cilicia (the southern and southeastern coast of modern Turkey) in southern Asia Minor, suggests frequent contacts with Berenike, the nearest port through which such jars could have been trans-shipped.

Fig. 15.11: Some of the buildings in the enigmatic late Roman period settlement of Qaryat Mustafa ‘Amr Gama in Wadi Umm Atlee.

Fig. 15.12: Some of the buildings in the enigmatic late Roman period settlement of Qaryat Mustafa ‘Amr Gama in Wadi Umm Atlee.

The site of Qaryat ‘Ali Muhammad Husayn, which we also named after one of our’ Ababda guides, counts at least eight rather large buildings in four different areas. There is no evidence of what its purpose might have been. It may have served as a stop on the route between Hitan Rayan and Vetus Hydreuma (Wadi Abu Greiya) as the buildings are dispersed over the wadi and not clustered in a group.

It seems from the late fourth century AD on that several groups sought refuge and relative safety in the Eastern Desert. One of these hiding places may have been the settlement of Umm Heiran not far from the large Roman emerald mining town of Sikait (see Chapter 12). Tucked away in a narrow wadi dissecting Wadi Gemal, this settlement numbered over 190 small buildings, and one larger structure, which may have been a church or administrative building. A small cemetery lay northeast of the settlement.

Survey work has discovered about ten other sites in the Eastern Desert whose similarity in locations, plans, appearances and construction techniques of buildings, and dates of activity parallel those of Qaryat Mustafa ‘Amr Gama, Hitan Rayan, and Umm Heiran. Their functions also remain enigmatic, but identification as Christian hermit (laura) communities is possible. In late Roman Egypt, the desert was a refuge for those who sought to avoid taxes, public service, or religious persecution. Large numbers of Christian monks, recluses, and hermits resided in the deserts especially in the early fifth century and these enigmatic settlements may be evidence of their activities.

All graves found near these putative ‘Christian’ settlements were late Roman ‘ring-cairn’ (doughnut) tombs. The number of graves seems rather small compared to the sizes of most settlements, which suggests that these sites were only used for short periods of time. Alternatively, as mentioned in Chapter 8, it is also possible that many of the dead were returned to the Nile Valley, which is only logical if the inhabitants were not local desert people. Most of the pottery found in these settlements is of Nile Valley or foreign, non-Egyptian, origin. The number of local hand-made pottery shards, the so-called Eastern Desert Ware, is remarkably small, which makes it likely that the population of these settlements consisted largely of Egyptians from the Nile Valley or Red Sea coastal towns.

It is possible that some, if not all, of these enigmatic desert settlements were communities where groups of prospectors would gather and start their expeditions, looking for gold or other valuable deposits. As most auriferous deposits had already been discovered during the New Kingdom, this is unlikely and no gold mines have been found associated with any of these settlements. It is also unlikely that these sites were military marching camps. The army built few of these in the late Roman period. The settlements we have found are not fortified and are not situated in any tactically or strategically important locations.