Once somebody has set up your account, here’s what it’s like getting into, and out of, a Mac. (For the purposes of this discussion, “you” are no longer the administrator—you’re one of the students, employees, or family members for whom an account has been set up.)

When you first turn on the Mac—or when the person who last used this computer chooses  →Log Out—the Login screen shown in Figure 13-1 appears. At this point, you can proceed in any of several ways:

→Log Out—the Login screen shown in Figure 13-1 appears. At this point, you can proceed in any of several ways:

Restart. Click if you need to restart the Mac for some reason. (The Restart and Shut Down buttons don’t appear here if the administrator has chosen to hide them as a security precaution.)

Shut Down. Click if you’re done for the day, or if sudden panic about the complexity of accounts makes you want to run away. The computer turns off.

Log In. To sign in, click your account name in the list. If you’re a keyboard speed freak, you can just type the first letter or two—or press the up or down arrow keys—until your name is highlighted. Then press Return.

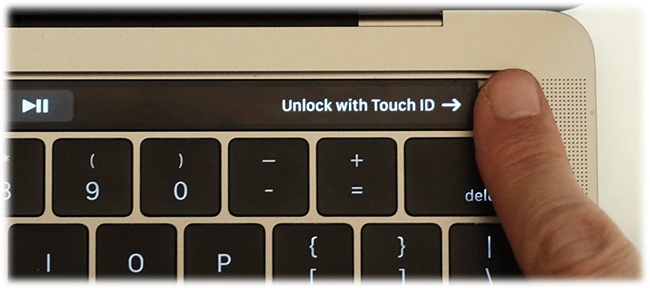

Either way, the password box appears now, if a password is required. (Of course, if you’re lucky enough to have a Touch Bar on your Mac, and you’ve taught it to recognize your fingerprint [Chapter 4], then no password box appears. You can just touch your finger to the power button to log in, as shown in Figure 13-10.)

Figure 13-10. Touch ID—the fingerprint reader on Macs with Touch Bars—really is the ultimate. You can wake your Mac and prove your authenticity simultaneously, with a single touch of the power button.

If you accidentally clicked the wrong person’s name on the first screen, you can click Back. Otherwise, type your password, and then press Return (or click Log In).

You can try as many times as you want to type the password. With each incorrect guess, the entire password box shudders violently from side to side, as though shaking its head no. (If you see a

icon in the password box, guess what? You’ve got your Caps Lock key on, and the Mac thinks you’re typing an all-capitals password.)

icon in the password box, guess what? You’ve got your Caps Lock key on, and the Mac thinks you’re typing an all-capitals password.)If you try unsuccessfully three times, your hint appears—if you’ve set one up. And if even that safety net fails, you can use your Apple ID as the key to resetting your password. See the box on the facing page.

Once you’re in, the world of the Mac looks just the way you left it (or the way an administrator set it up for you). Everything in your Home folder, all your email and bookmarks, your desktop picture and Dock settings—all of it unique to you.

Unless you’re an administrator, you’re not allowed to install any new programs (or, indeed, to put anything at all) into the Applications folder. That folder, after all, is a central software repository for everybody who uses the Mac, and the Mac forbids everyday account holders from moving or changing all such universally shared folders.

When you’re finished using the Mac, choose  →Log Out (or press Shift-

→Log Out (or press Shift- -Q). A confirmation message appears; if you click Cancel or press Esc, you return to whatever you were doing. If you click Log Out or press Return, you return to the screen shown in Figure 13-1, and the sign-in cycle begins again.

-Q). A confirmation message appears; if you click Cancel or press Esc, you return to whatever you were doing. If you click Log Out or press Return, you return to the screen shown in Figure 13-1, and the sign-in cycle begins again.

When you choose  →Log Out and confirm your intention to log out, the Login screen appears, ready for its next victim.

→Log Out and confirm your intention to log out, the Login screen appears, ready for its next victim.

But sometimes people forget. You might wander off to the bathroom for a minute, but run into a colleague there who breathlessly begins describing last night’s date and proposes finishing the conversation over pizza. The next thing you know, you’ve left your Mac unattended but logged in, with all your life’s secrets accessible to anyone who walks by your desk.

You can tighten up that security hole, and many others, using the options in the Security & Privacy→General panel of System Preferences:

Require password [immediately] after sleep or screen saver begins. This option gives you a password-protected screensaver that locks your Mac when you wander away. Now, whenever somebody tries to wake your Mac after the screensaver has appeared (or when the Mac has simply gone to sleep according to your settings in the Energy Saver panel of System Preferences), the “Enter your password” dialog box appears. No password? No access.

The pop-up menu here (which starts out saying “immediately”) is a handy feature. Without it, the person most inconvenienced by the password requirement would be you, not the snitch from Accounting; even if you just stepped away to the bathroom or the coffee machine, you’d have to unlock the screensaver with your password. It would get old fast.

Instead, the password requirement can kick in after you’ve been away for a more serious amount of time—5 minutes, 15 minutes, an hour, whatever. You can still put the Mac to sleep, or you can still set up your screensaver to kick in sooner than that. But until that time period has passed, you’ll be able to wake the machine without having to log in.

Show a message when the screen is locked. Whatever you type into this box will appear on the Login screen (where you click your name in the list) or the screensaver. It could be, “Getting coffee…” or your name and cellphone number, or anything you like.

Disable automatic login. This is just a duplicate of the “Automatic login” on/off switch described in Figure 13-9. Apple figured that this feature really deserved some presence on a control panel called Security & Privacy.

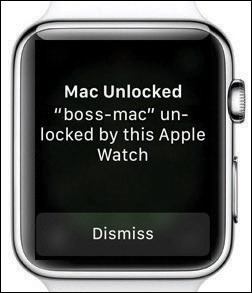

Allow your Apple Watch to unlock your Mac. You don’t need a password to unlock your Mac anymore—if you’re wearing an Apple Watch. It acts as a wireless master key that logs you in automatically, as described in the box on the facing page. This master switch for that glorious feature appears only if you’ve turned on two-factor authentication (Tip).

If you click the Advanced button (at the bottom of the Security & Privacy pane of System Preferences), you get these bonus tweaks:

Log out after [60] minutes of inactivity. You can make the Mac sign out of your account completely if it figures out that you’ve wandered off (and it’s been, say, 15 minutes since the last time you touched the mouse or keyboard). Anyone who shows up at your Mac will find only the standard Login screen.

Require an administrator password to access system-wide preferences. Ordinarily, certain System Preferences changes require an administrator’s approval—namely, the ones that affect the entire computer and everyone who uses it, like Date & Time, Users & Groups, Network, Time Machine, and Security & Privacy. If you’re not an administrator, you can’t make changes to these panels until an administrator has typed in her name and password to approve your change.

However, once Mr. Teacher or Ms. Parent has unlocked one of those secure preference settings, they’re all unlocked. Once the administrator leaves your desk, you can go right on making changes to the other important panels (Network and Time Machine and Security & Privacy) without the administrator’s knowledge.

Unless this “Require an administrator password” box is turned on, that is. In that case, an Administrative account holder has to enter her name and password to approve each of those System Preferences panes individually.