Introduction

3. Historical and Social Background

6. Literary Purpose and Theology

1. DATE

The setting of the book(s) of Chronicles1 is the postexilic community of Judea.2 Nevertheless, the specific time of the writing of Chronicles remains open to debate. Proposals range from the Persian time frame (400s BC) to the Greek/Hellenistic time frame (300s–200s BC) to the Maccabean/Hasmonean time frame (100s BC). The attention given to temple worship and priestly duties would seem to imply a date following the dedication of the Second Temple (that is, after 516/15 BC).3 In addition, the extent of the family line of Zerubbabel traced by the Chronicler (cf. 1Ch 3:19–24) would imply a date following the reforms of Ezra and Nehemiah (i.e., after the mid to low 400s BC).4

Moreover, the language and content of Chronicles does not seem to reflect a Greek setting, implying that the text was composed prior to 333 BC.5 In addition, the use of Chronicles by other literary works from Maccabean/Hasmonean times (such as Sirach) implies that the text was in existence and seen as having some degree of authority prior to 180 BC.6 In sum, these observations indicate a likely range of 430–340 BC for the writing of Chronicles, with some preference for the earlier side of this range (ca. 430–400 BC).7

The content of Chronicles extends from Adam (1Ch 1:1) through the Persian king Cyrus (cf. 2Ch 36:22–23). This noted, the genealogical section at the beginning of Chronicles (1Ch 1–9) actually extends beyond the time of the closing section of Chronicles (2Ch 36) and into the postexilic setting (as reflected in the family line of Zerubbabel; 1Ch 3:19–24).8 In addition, this structure of Chronicles shows that while the historical time frame of Chronicles is clearly postexilic, the theological time frame of Chronicles is exilic.9 That is to say, while the text was composed (or at least completed) after the exile, the book of Chronicles nevertheless ends on the eve of the postexilic time frame.10 This contrast can be appreciated from the following overview of the postexilic time:

The Persian Empire and Postexilic Judea

2. AUTHORSHIP

The most relevant factor that should be stressed on the topic of the authorship of Chronicles is that the book of Chronicles (along with much of the OT) lacks any notation of authorship. Thus it is anonymously authored and, from the vantage point of inspiration, such anonymity was clearly the intent of God.

The most common theme considered in the authorship of Chronicles is the issue of the relationship between the author(s) of Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah.11 Among those who propose a common author for these works (namely, Ezra), the supporting evidence includes a degree of similarity in vocabulary and Hebrew syntax, a penchant for source citations and lists, a degree of overlapping ideological and theological concerns (such as the temple and priests), and Ezra-Nehemiah’s picking up where 2 Chronicles ends (cf. 2Ch 36:23 and Ezr 1:1–4). Such factors also led to the early Jewish perspective (cf. the Babylonian Talmud) that Ezra was the author of Chronicles.12

In spite of such points of similarity, there are also a number of thematic distinctions between Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah, such as the level of attention directed to the Davidic monarchy (high in Chronicles, low in Ezra-Nehemiah), stress on the Sabbath (low in Chronicles, high in Ezra-Nehemiah), and interest in the prophetic office (high in Chronicles, low in Ezra-Nehemiah).13 Such points of difference have caused a number of scholars to reject the view of a common author for Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah.14

All told, the issue of the authorship of Chronicles is likely to remain an unsettled area of biblical scholarship. Given that God saw fit to have Chronicles become a part of canonical biblical literature as an anonymous work, it seems fitting to refer to the (human) author as “the Chronicler” and focus interpretive energies on the theological message of the Chronicler.

3. HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL BACKGROUND

Following the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC and large-scale deportations of the citizens of Judah to Babylonia, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar appointed Gedaliah as governor of Judah in Mizpah, to the north of Jerusalem (cf. 2Ki 25:22–24).15 The establishment of this new administration prompted those who had scattered in battle or had fled to neighboring regions to return to Judah (cf. Jer 40:5–12). Yet before long Gedaliah was assassinated, which resulted in more deportations, more flights abroad (especially to Egypt), and a sparsely inhabited Judah. During this time Edom took advantage of Judah’s dire situation by occupying the southern parts of what had been Judah, particularly in the region between Beersheba and Beth Zur.16

Meanwhile, the Nabateans settled in Transjordanian areas previously belonging to Edom as well as Cisjordan wilderness regions. All things considered, those who remained in the land (“the poorest people of the land”; cf. 2Ki 25:12; Jer 52:16) were concentrated in the central hill country to the north of Jerusalem over the course of the exilic period.17 The end of the bleak exilic period begins with the absorption of the Babylonian Empire into the Persian Empire in 539 BC.18

Following the Persian takeover of the Babylonian Empire in 539 BC, all of what had been Judah (as well as the northern kingdom, “Israel”) fell under one of the large administrative units of the Persian Empire (satrapies) known by the geographical description “Beyond the [Euphrates] River.” Within this region was the small province of Judea (frequently referred to by the Aramaic Yehud; cf. Ezr 5:8).19 Yehud was further divided into five or six districts (depending on whether Jericho is counted as a district) with the following administrative centers: Jerusalem, Beth Hakkerem, Mizpah, Beth Zur, and Keilah (cf. Neh 3). The Decree of Cyrus in 539/538 BC enabled those exiled to Babylonia to return to their homeland and rebuild what was left of Judea (see commentary at 2Ch 36:22–23; cf. Ezr 2:1–67; Ne 7:5–73).20 While still clearly under the hegemony of the Persian Empire, Judea was nevertheless granted some degree of political autonomy under the governorship of Sheshbazzar and subsequent leaders. A partial list of the leaders of Yehud is summarized below:21

Governors of Postexilic Judea (Yehud)

| Name | Dates |

|---|---|

|

Sheshbazzar |

538–20 BC |

|

Zerubbabel |

520–? BC |

|

Elnathan |

Late 6th century BC |

|

Nehemiah |

445–33 BC |

|

Bagohi (or Bagavahya/Bagoas) |

Ca. 408 BC |

|

Yehezeqiah |

4th century BC |

Before long, the euphoria following the Decree of Cyrus gave way to the reality of the bleak situation in Judea. Discouragement replaced hope as the returnees faced the daunting challenge of rebuilding homes and cities, reestablishing societal infrastructure (such as agricultural production), and rebuilding the Jerusalem temple. These challenges were exacerbated by episodes of internal and external opposition.22

Nonetheless, spurred on by the ministries of Haggai and Zechariah, work on the temple was restarted and completed in 516/515 BC (cf. Ezr 6:14–15), resulting in another high point of optimism within the postexilic community. In time, however, the situation in Judea again reached a state of despair, as reflected in the report that reached Nehemiah in the Persian citadel of Susa (cf. Ne 1:2–3).23 These challenges lead to the appointment of Nehemiah as governor of Yehud (cf. Ne 5:14) and the commissioning of Ezra in the realm of religious affairs (cf. Ezr 7:25–26).24

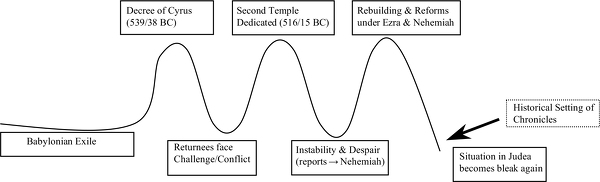

The leadership and rebuilding organized by Nehemiah and the spiritual revival facilitated by Ezra fostered a new era of hope and optimism within Yehud. This mood of optimism is enhanced by territorial gains in the west and south, enhanced security, and the fortification and repopulation of Jerusalem.25 However, the end of the Ezra-Nehemiah time frame is punctuated with instances of recurring spiritual and societal problems. The closing verses of Nehemiah lament the neglect of God’s house (Ne 13:4–11), violation of the Sabbath (Ne 13:15–16), and intermarriage with foreigners (Ne 13:23–2826).27 The issue of intermarriage implies spiritual compromise and fostered cultural fragmentation, as some within the Judean community became unable to speak the “language of Judah” (cf. Ne 13:24).28 Thus, once again, a time of hope and promise in Judea gave way to more challenge and discouragement. In other words, waves of hope within the postexilic community repeatedly give way to periods of despair and discouragement—a cycle that can be visually seen in the following graph:

Cycles of Hope and Discouragement in Postexilic Judea

The manifold challenges facing those in Judean Yehud and the possibility that dispersed Judeans might opt to stay abroad might factor into the phrase that the Chronicler chose to end his work as follows: “Anyone of his [Yahweh’s] people among you—may the LORD his God be with him, and let him go up.” This final exhortation is an invitation to those still outside the Promised Land to come and rejoin “all Israel.” As such, the theological setting of Chronicles is the eve of the postexilic setting—a hopeful contrast to the difficult historical situation in Judea. Thus, while the Chronicler’s time frame may be one of disappointment, the Chronicler nonetheless proclaims a message of hope and possibility (also see “Literary Purpose and Theology,” below).

4. GENRE

The OT books we know as 1 and 2 Chronicles have carried a variety of names over time.29 For example, the name of Chronicles in the Greek translation of the OT (the Septuagint [LXX]) is Paraleipomenōn tōn basileōn Iouda, which means “[the] things omitted concerning the kings of Judah.” The implication of this title may have influenced the relocation of Chronicles within the Christian Bible from the end of the OT to just after 1 and 2 Kings.30 The resulting canonical placement unfortunately suggests that the purpose of Chronicles is simply to provide supplemental information for the texts in the Deuteronomic History (particularly Samuel and Kings), rather than having its own literary-theological message.31

By contrast, the name for Chronicles in the Hebrew Bible (dibrê hayyāmîm, meaning “the matters/events of the days”)32 suggests a historical and annalistic purpose to the message of Chronicles. Similarly, the name for Chronicles in the Latin Vulgate is Chronicon (or Chronikon) Totius Divinae Historiae, meaning “Chronicle of the Total Divine History,” suggesting a wide-ranging engagement of God’s involvement in human history.33

One consideration in analyzing the genre of Chronicles is the fact that Chronicles has more in common with the genre of “annal” than it does with the genre of “chronicle.” While both of these literary genres include individuals, records, and deeds, a chronicle is typically an abbreviated listing of historical events, while an annal features more sustained summaries of historical events with narrative shaping (including a variety of genres and subgenres)34 and an overall ideological purpose.35 The narrative shaping of annals typically summarizes the deeds of rulers and people against the backdrop of divine blessing (or judgment).36 In short, the genre of annal, like the text and content of Chronicles, features documentary details (what took place), ideological aspects (the significance of what took place), and literary elements (the shaping and stylistics of the account of what took place).

5. SOURCES

Chronicles, like the genre of annalistic literature discussed above, reflects the usage (selectivity) and shaping (literary-theological) of a wide range of sources from the administrative realm (e.g., kings and officials, military, taxation, royal assets) and the religious realm (e.g., temple officials, temple assets, temple procedures and responsibilities, prophetic oracles).37 Kings of the biblical world often left detailed accounts of invasions, military maneuvers, political relationships, and the like in extensive royal annals.38 The various references to source books in the OT indicate that this was also practiced in ancient Israel.39

Sources could later be consulted and referenced in the composition of additional literary works as reflected in Chronicles. Lastly, some ancient Near Eastern annals (such as those of Thutmose III) use phraseology reminiscent of Chronicles and Kings, including the expression “as it is written in,” to bring the reader’s attention to earlier, authoritative texts. A selection of sources cited in Chronicles is as follows:40

- • The Genealogical Records during the Reigns of Jotham King of Judah and Jeroboam King of Israel (1Ch 5:17)

- • The Genealogies Recorded in the Book of the Kings of Israel (1Ch 9:1)

- • The Book of the Annals of King David (1Ch 27:24)

- • The Book of the Kings of Israel and Judah (2Ch 27:7; 35:27; 36:8)

- • The Book of the Kings of Judah and Israel (2Ch 16:11; 25:26; 28:26; 32:32)

- • The Book of the Kings of Israel (2Ch 20:34)

- • Annotations [NASB: “Treatise”] on the Book of the Kings (2Ch 24:27)

- • The Annals [NASB: “Records”] of the Kings of Israel (2Ch 33:18)

- • The Written Instruction of David the King of Israel (2Ch 35:4)

- • The Written Instruction of Solomon (2Ch 35:4)

- • The Records of Samuel the Seer (1Ch 29:29)

- • The Records of Nathan the Prophet (1Ch 29:29; 2Ch 9:29)

- • The Records of Gad the Seer (1Ch 29:29)

- • The Prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite (2Ch 9:29)

- • The Visions of Iddo the Seer (2Ch 9:29)

- • The Records of Shemiah the Prophet and Iddo the Seer That Deal with Genealogies (2Ch 12:15)

- • The Annotations [NASB: “Treatise”] of the Prophet Iddo (2Ch 13:22)

- • The Annals of Jehu the son of Hanani (2Ch 20:34)

- • The Words of David and of Asaph the Seer (2Ch 29:30)

- • The Records of the Seers [= ḥôzāy; another term for prophets] (2Ch 33:19)

Beyond these directly noted sources, the intimate details reflected in temple organization, military structure, and the like imply that the Chronicler used other sources as well. Moreover, the genealogies of 1 Chronicles 1–9 clearly draw on genealogical sources that are not directly cited (esp. those of Genesis).41 As the list of sources given above illustrates, a number of the sources referenced by the Chronicler have a prophetic connection, reflecting the role of the prophet in declaring the Word of God and mediating the covenant between Yahweh and Israel (also cf. 2Ch 26:22; 32:32). Similarly, note also the nearly identical content shared between passages in Kings and sections of Isaiah and Jeremiah (e.g., Isa 36–39 and 2Ki 18–20; Jer 52 and 2Ki 25).

6. LITERARY PURPOSE AND THEOLOGY

Understanding Chronicles through the lens of an annal aids in the understanding of such variations of subgenre, content, and stylistics seen throughout Chronicles and allows interpretive attention to shift to the purpose of such literature. In short, annalistic literature such as Chronicles is not history for history’s sake.42 Instead, such texts arrange historical information (often gleaned from earlier texts; see “Sources”) with an overarching political and/or religious agenda, such as teaching and inspiring the adoption of a certain perspective (e.g., spiritual, theological, political, ethnic) significant to the historical context (social, political, etc.) of the original audience (see “Historical and Social Background,” above).43 In the case of Chronicles, a theology of covenantal hope (much more than the oft-cited notion of “immediate retribution”)44 guides the selection, shaping, and structure of the text, with the goal of imparting this perspective to the Chronicler’s readers and hearers.45 This perspective makes the tone of the Chronicler’s presentation of historical events didactic, almost sermonic, in its literary style and presentation.46

The Chronicler’s survey of events in the history of Judah (often, but not always, from a positive perspective)47 is articulated through a theological framework centered on covenant.48 In short, the book of Chronicles recounts the faithful acts of God as a means of provoking the seeking of God, hope in God, and covenantal faithfulness (obedience) within the Judean community.49 Establishing continuity between the past and present is one of the ways in which the Chronicler weaves together this theological message of (covenantal) hope—as well as call to covenantal obedience—for his postexilic audience.50 Note that the apostle Paul had a similar understanding of earlier biblical literature that showcased the faithfulness of God and simultaneously called God’s people to obedience and perseverance: “For everything that was written in the past was written to teach us, so that through endurance and the encouragement of the Scriptures we might have hope” (Ro 15:4; cf. 1Co 10:11).

As Paul’s writings suggest, the message of Chronicles of covenantal hope, seeking God, obedience, and faithful endurance transcends the Chronicler’s time and percolates with meaning for God’s people at all times. Similarly, the Chronicler is careful to emphasize that deeper internal issues, such as faithfulness, obedience, and personal purity, must coincide with external acts of worship.51 Moreover, the Chronicler repeatedly draws focus to God so that the hope of his audience (“all Israel,” not simply Judah)52 is focused on God and his covenantal faithfulness and reconciling nature. As such, the temple is fundamental to the Chronicler’s message of hope as the temple was both a tangible and symbolic image of divine presence, divine-human reconciliation, and divine-human fellowship (cf. 2Ch 7:12–22).53

Lastly, the final phrase of the Chronicler’s work (“Let him go up”) leaves the audience with a sense of anticipation of what might happen next and the realization that they (the Chronicler’s original audience) are the ones who will finish this story! This final exhortation is an invitation to those still outside the Promised Land to come and rejoin “all Israel.”54 Thus, while the Chronicler’s historical time frame may be one of disappointment (see “Date” and “Historical and Social Background,” above), the Chronicler nonetheless proclaims a message of covenantal hope and possibility.55 The Chronicler’s review of historical events functions to shape the theological awareness of the postexilic Judean community—much as the book of Deuteronomy recaps history to the new generation waiting to enter the Promised Land who were born during the “exile” of the wilderness wanderings.56 In both, there is the possibility and hope of entering the land given by Yahweh and living as a covenantal community wholeheartedly in their commitment to him.57 Thus the Chronicler ends his work with a message of the hope and possibility that comes with covenantal faithfulness, a note of covenantal hope also expressed by God through Jeremiah:

“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the LORD, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future. Then you will call upon me and come and pray to me, and I will listen to you. You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart.” (Jer 29:11–13)

7. SYNOPTIC ISSUES

Synoptic issues with Chronicles typically parallel passages from 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, or 2 Kings and less often involve sections from 1 Samuel, Ezra, Nehemiah, and the Psalter.58 For better or worse, commentaries on Chronicles are often little more than a running comparison of synoptic issues featuring either a sustained apologia with frequent harmonization or a sustained string of unabashed speculation regarding the ideology behind the Chronicler’s assumed “changes” to earlier texts.59 Unfortunately such approaches come at the detriment of engaging the meaning and theological message of the Chronicler’s text on its own terms.60 Instead, the biblical texts with which Chronicles has parallel passages or differing thematic emphases (such as Samuel and Kings) reflect selectivity, shaping, and emphasis in line with their respective authorial intent in a given pericope. Thus, distinctions and differences in parallel texts (such as Kings and Chronicles) may simply reflect different approaches to telling the same story or reflect a different voice (such as thematic emphasis or theological point) drawn from one event.61

While plausible suggestions can be given for instances of differences between parallel texts, the matter of the synoptic issue between Chronicles and other OT books is largely a philosophical-presuppositional area that goes hand in hand with one’s view of the Bible vis-à-vis inspiration and inerrancy.62 For evangelical readers of Chronicles the issue of potential differences between two biblical texts speaking on the same topic can be disconcerting and oftentimes motivates the drive for harmonization—even when such harmonization stretches the limits of plausibility. Yet the impulse to force solutions should be resisted; God does not need us to protect him or his Word. Moreover, forced and implausible solutions to synoptic difficulties will hardly change the mind of the skeptic. Thus it is often preferable to leave a point of interpretive tension as it is rather than to provide a forced solution.63

While interpretation is largely a presuppositional issue, there is a handful of categories wherein synoptic issues are typically addressed and that will be covered below.

Synoptic Issues Involving Numbers

Differences in numbers are one of the major categories treated in synoptic studies, though it should be noted that there is complete agreement in numbers between Chronicles and parallel texts in 195 out of 213 instances.64 In several of the instances where numbers differ, the number reflected in Chronicles is actually the correct number. For example, the Hebrew text has “40,000” stalls for chariot horses at 1 Kings 4:26[5:6], while the text at 2 Chronicles 9:25 has the correct reading of “4,000” stalls (also cf. the LXX at 1Ki 10:26).65

In other cases, the difference simply reflects a distinction in the basis of counting or reckoning.66 For example, the Chronicler has a different tabulation at 1 Chronicles 9:6 from that found at Nehemiah 11:6 (690 versus 468) that may relate to a different approach to counting (“men” is noted at Ne 11:6, whereas 1Ch 9:6 has “people”). Alternatively, the difference may simply be a factor of the time gap between the point in time utilized by the Chronicler and that utilized by Nehemiah.67 Similar explanations can be posited for the difference in the enumeration of priests reflected in Chronicles and Nehemiah (1,760 in 1Ch 9:13 versus 1,192 in Ne 11:12–14).

Other synoptic issues involving numbers may be simply stylistic differences, such as rounding versus not rounding numbers as reflected in the following summaries of David’s reign:

He ruled over Israel forty years—seven in Hebron and thirty-three in Jerusalem. (1Ch 29:27)

In Hebron he reigned over Judah seven years and six months, and in Jerusalem he reigned over all Israel and Judah thirty-three years. (2Sa 5:5)

In this example, the Chronicler opted to report David’s reign in whole years (“seven years”), while the author of 2 Samuel also included the months (“seven years and six months”). Note that the Chronicler also includes the months of David’s reign in his earlier genealogical survey (cf. 1Ch 3:4). Instances in rounding may also explain some differing numbers of military figures in synoptic accounts.68

Synoptic Issues Involving Perspective

In addition to the handling of numbers, synoptic differences may reflect a different point of reference or perspective that is not necessarily mutually exclusive (i.e., it can be both-and and is not necessarily either-or). For example, note the following statements regarding the ascension of Solomon:

Solomon sat on the throne of his father David. (1Ki 2:12)

Solomon sat on the throne of the LORD. (1Ch 29:23)

Note that these statements, while different, are both true.69 The statement in Kings stresses God’s faithfulness to fulfill his promise with respect to the Davidic covenant (see 2Sa 7:12), while the statement in Chronicles stresses the ultimate reality of God’s universal kingship and (by extension) the role of the Israelite king as undershepherd to God. The Chronicler’s manner of expressing Solomon’s reign is consistent with his authorial intent (Tendenz) to emphasize that the people led by the king are God’s people (cf. 2Ch 1:10), the kingdom is God’s kingdom (cf. 1Ch 17:14; 2Ch 13:8), and that the king sits on God’s throne (cf. 1Ch 29:23; 2Ch 9:8).70

Similarly, the Chronicler tends to emphasize the involvement of “all Israel” in important spiritual events in line with his focus on the whole covenantal community of Yahweh. For example, while the account of the taking of Jerusalem in Samuel (cf. 2Sa 5:6–10) focuses on the efforts of a small band of warriors, the Chronicler notes the involvement of “all the Israelites” in this important event (cf. comments on 1Ch 11:4–8).71

Lastly, the presentation of Manasseh in Chronicles emphatically shows the forgiving and reconciling nature of Yahweh experienced by Manasseh at the end of his days (cf. 2Ch 33)72 in line with his message of covenantal hope for God’s people, while the account in Kings summarizes the spiritual infidelity that characterized the vast majority of Manasseh’s reign (cf. 2Ki 21) in line with his distinct authorial intent.73

Synoptic Issues Resulting from Scribal Error

Another area of synoptic differences may relate to errors in textual transmission. Although many evangelical believers hold to the view of the inerrancy of Scripture, the doctrine of inerrancy refers to the originally crafted manuscripts of biblical books (called “autographs”) and does not extend into scribal/textual transmission of the biblical texts.74 By the sovereign will of God, the transmission process was not inerrant; consequently, there may be variations in the manuscripts of biblical books in which only one reading is correct.

While these variations are statistically small, they do factor into a number of noted synoptic divergences.75 For example, 2 Samuel 24:13 has “seven” years in the Hebrew text (MT) rather than “three” years as recorded at 1 Chronicles 21:12. Nonetheless, the NIV translates “three” at 2 Samuel 24:13, given the LXX at this verse as well as the parallel text here (see the NIV note), reflecting the likelihood of a scribal transmission error.76 In addition, the similarity of certain Hebrew letters77 likely brought about unintended spelling variations over time.78 Moreover, the overlapping usage of some of these similar-looking letters as composite vowels, prefixes (verbal, definite article), consonants, suffixes (possessive/pronominal, direct object), and verbal inflection markers no doubt facilitated some of the transmission errors observed.

8. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Braun, R. L. 1 Chronicles. Word Biblical Commentary. Waco, Tex.: Word, 1986.

Day, J. “Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature.” Journal of Biblical Literature 105 (1986): 385–408.

Dillard, R. B. 2 Chronicles. Word Biblical Commentary. Waco, Tex.: Word, 1987.

Hill, A. E. 1 & 2 Chronicles. NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003.

Ishida, T., ed. Studies in the Period of David and Solomon and Other Essays. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1982.

Japhet, S. I & II Chronicles: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1993.

Johnstone, W. 1 and 2 Chronicles. Volume 1: 1 Chronicles 1–2 Chronicles 9: Israel’s Place among the Nations. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 253. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1997.

———. 1 and 2 Chronicles: Volume 2: 2 Chronicles 10–2 Chronicles 36: Guilt and Atonement. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 254. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1997.

Keel. O. The Symbolism of the Biblical World. Translated by T. J. Hallet. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1997.

Kitchen, K. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

Mabie, F. J. “2 Chronicles.” Pages 286–393 in Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary on the Old Testament, volume 3. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

McConville, J. G. I and II Chronicles. Daily Study Bible. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1984.

Provan, I., V. P. Long, and T. Longman III. A Biblical History of Israel. Louisville, Ky./London: Westminster John Knox, 2003.

Rainey, A. F., and R. S. Notley. The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Carta, 2005.

Selman, M. J. 1 Chronicles. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1994.

———. 2 Chronicles. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1994.

Thiele, E. R. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983.

Thompson, J. A. 1, 2 Chronicles. New American Commentary. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1994.

9. OUTLINE

- I. The Chronicler’s Genealogical Survey of All Israel (1Ch 1:1–9:44)

- A. From Adam to the Sons of Israel (1:1–2:2)

- B. The Tribes of Israel (2:3–9:1)

- 1. The Tribe of Judah (2:3–4:23)

- a. The Family Line of Judah Part One (2:3–55)

- b. The Line of David (3:1–9)

- c. Listing of Davidic Kings (3:10–24)

- d. The Family Line of Judah Part Two (4:1–23)

- 2. The Tribe of Simeon (4:24–43)

- 3. The Transjordanian Tribes (5:1–26)

- a. The Tribe of Reuben (5:1–10)

- b. The Tribe of Gad (5:11–17)

- c. Military Accomplishments of the Transjordanian Tribes (5:18–22)

- d. Transjordanian Manasseh (5:23–26)

- 4. The Tribe of Levi (6:1–81)

- 5. The Northern Tribes (7:1–8:40)

- a. The Tribe of Issachar (7:1–5)

- b. The Tribe of Benjamin Part One (7:6–12)

- c. The Tribe of Naphtali (7:13)

- d. The House of Joseph (7:14–29)

- i. The Tribe of Cisjordan Manasseh (7:14–19)

- ii. The Tribe of Ephraim (7:20–27)

- iii. The Settlement of Ephraim and Cisjordan Manasseh (7:28–29)

- e. The Tribe of Asher (7:30–40)

- f. The Tribe of Benjamin Part Two (8:1–40)

- 6. Genealogical Summary (9:1)

- 1. The Tribe of Judah (2:3–4:23)

- C. Postexilic Resettlement (9:2–34)

- D. The Line of Saul (9:35–44)

- II. The United Monarchy (1Ch 10:1–2Ch 9:31)

- A. The Closing Moments of Saul’s Reign (10:1–14)

- B. The Reign of David (11:1–29:30)

- 1. David’s Enthronement and Consolidation of Power (11:1–12:40)

- a. David’s Coronation over All Israel (11:1–3)

- b. David’s Taking of Jerusalem (11:4–8)

- c. David’s Power and Support (11:9–12:40)

- 2. Return of the Ark of the Covenant Initiated (13:1–14)

- 3. David’s Family (14:1–17)

- 4. Return of the Ark of the Covenant Completed (15:1–16:43)

- 5. The Davidic Covenant (17:1–27)

- 6. David’s Military Victories and Regional Hegemony (18:1–20:8)

- a. David’s Victories to the North, East, South, and West (18:1–14)

- b. David’s Officials (18:15–17)

- c. David’s Battles against the Ammonites (19:1–20:3)

- d. David’s Additional Battles against the Philistines (20:4–8)

- 7. David’s Presumptuous Census and Selection of the Temple Site (21:1–22:1)

- 8. David’s Preparations for the Temple and Leadership Transfer (22:2–29:30)

- a. David’s Preparation of Temple Materials and Craftsmen (22:2–4)

- b. David’s Initial Charge to Solomon and the Leaders of Israel (22:5–19)

- c. David’s Organization of Levitical Families (23:1–32)

- d. Priestly Divisions (24:1–31)

- e. David’s Organization of Levitical Musicians (25:1–31)

- f. Levitical Gatekeepers (26:1–19)

- g. Levitical Treasurers (26:20–28)

- h. Levites Serving Away from the Temple (26:29–32)

- i. David’s Military Leaders (27:1–24)

- j. David’s Officials (27:25–34)

- k. David’s Second Charge to Solomon and the Leaders of Israel (28:1–10)

- l. David Gives the Temple Plans to Solomon (28:11–19)

- m. David Gives Another Charge to Solomon (28:20–21)

- n. Gifts for the Temple Project (29:1–9)

- o. David’s Benedictory Prayer of Praise (29:10–20)

- p. Solomon’s Public Coronation (29:21–25)

- q. David’s Death and Regnal Summary (29:26–30)

- 1. David’s Enthronement and Consolidation of Power (11:1–12:40)

- C. The Reign of Solomon and the Construction of the Temple (2Ch 1:1–9:31)

- 1. Solomon Assumes the Davidic Throne (1:1)

- 2. Solomon and All Israel Worship at Gibeon (1:2–6)

- 3. Solomon’s Dream Theophany and Request for Wisdom (1:7–13)

- 4. Solomon’s Equine Force and Chariot Cities (1:14)

- 5. Solomon’s Wealth (1:15)

- 6. Solomon’s Regional Trade in Horses and Chariots (1:16–17)

- 7. Solomon’s Construction of the Jerusalem Temple (2:1–7:22)

- a. Workers Conscripted and Phoenician Assistance Sought (2:1–18)

- b. Temple Building Details (3:1–17)

- c. Temple Furnishings (4:1–5:1)

- d. Deposit of the Ark of the Covenant and Temple Dedication (5:2–7:22)

- 8. Solomon’s Building and Trading Activity (8:1–18)

- 9. Visit of the Queen of Sheba (9:1–12)

- 10. Summary of Solomon’s Wealth (9:13–31)

- III. The Reigns of Judean Kings during the Divided Monarchy (2Ch 10:1–36:19)

- A. The Reign of Rehoboam (10:1–12:16)

- 1. Division of the Israelite Kingdom (10:1–11:4)

- 2. Rehoboam’s Fortifications and Administration (11:5–23)

- 3. Invasion of Pharaoh Shishak (12:1–12)

- 4. Rehoboam’s Regnal Summary (12:13–16)

- B. The Reign of Abijah (13:1–14:1)

- C. The Reign of Asa (14:2–16:14)

- 1. Asa’s Reforms and Military Strength (14:2–8)

- 2. Invasion of Zerah the Cushite (14:9–15)

- 3. Azariah’s Prophecy and Asa’s Further Reforms (15:1–19)

- 4. Asa’s Battle with the Northern Kingdom and Treaty with Aram (16:1–6)

- 5. Asa Rebuked by the Prophet Hanani (16:7–10)

- 6. Asa’s Regnal Summary (16:11–14)

- D. The Reign of Jehoshaphat (17:1–21:3)

- 1. Jehoshaphat’s Early Years (17:1–19)

- 2. Jehoshaphat’s Alliance with the Northern Kingdom (18:1–19:3)

- 3. Jehoshaphat’s Judiciary Reforms (19:4–11)

- 4. Jehoshaphat’s Battle against an Eastern Coalition (20:1–30)

- 5. Jehoshaphat’s Regnal Summary Part One (20:31–34)

- 6. Jehoshaphat’s Further Alliance with the Northern Kingdom (20:35–37)

- 7. Jehoshaphat’s Regnal Summary Part Two (21:1–3)

- E. The Reign of Jehoram (21:4–20)

- F. The Reign of Ahaziah (22:1–9)

- G. The Coup and Rule of Queen Athaliah (22:10–23:21)

- 1. Athaliah’s Coup (22:10–12)

- 2. Jehoiada’s Counter-coup and Installment of Joash (23:1–21)

- H. The Reign of Joash (24:1–27)

- I. The Reign of Amaziah (25:1–28)

- J. The Reign of Uzziah (26:1–23)

- K. The Reign of Jotham (27:1–9)

- L. The Reign of Ahaz (28:1–27)

- 1. Introduction to the Reign of Ahaz (28:1–4)

- 2. The Syro-Ephraimite Crisis (28:5–25)

- 3. Ahaz’s Regnal Summary (28:26–27)

- M. The Reign of Hezekiah (29:1–32:33)

- 1. Hezekiah’s Reforms and Temple Purification (29:1–36)

- 2. Hezekiah’s Passover Celebration (30:1–31:1)

- 3. Hezekiah’s Further Reforms (31:2–21)

- 4. The Invasion of the Assyrian King Sennacherib (32:1–23)

- 5. Hezekiah’s Illness (32:24–26)

- 6. Hezekiah’s Wealth and Accomplishments (32:27–31)

- 7. Hezekiah’s Regnal Summary (32:32–33)

- N. The Reign of Manasseh (33:1–20)

- O. The Reign of Amon (33:21–25)

- P. The Reign of Josiah (34:1–35:27)

- 1. Josiah’s Reforms (34:1–33)

- a. Introduction to Josiah’s Reign (34:1–2)

- b. Josiah’s Destruction of Idolatry (34:3–7)

- c. Josiah’s Temple Repairs (34:8–13)

- d. Discovery of the Book of the Law (34:14–33)

- 2. Josiah’s Passover Celebration (35:1–19)

- 3. Josiah’s Confrontation with Pharaoh Neco (35:20–24)

- 4. Josiah’s Regnal Summary (35:25–27)

- 1. Josiah’s Reforms (34:1–33)

- Q. The Reign of Jehoahaz (36:1–3)

- R. The Reign of Jehoiakim (36:4–8)

- S. The Reign of Jehoiachin (36:9–10)

- T. The Reign of Zedekiah and the Fall of Jerusalem (36:11–19)

- A. The Reign of Rehoboam (10:1–12:16)

- IV. The Exilic Period (2Ch 36:20–21)

- V. The Decree of Cyrus (2Ch 36:22–23)

1. In this commentary the term “Chronicles” is frequently used in place of “1 and 2 Chronicles” since these books were originally one literary work (cf. the verse enumeration and midpoint identification employed by the Masoretic scribes). Consequently, the outline schema used in the commentary does not start over in 2 Chronicles, but rather continues the outline from 1 Chronicles to underscore this literary unity (see Outline, below).

2. The term “Judea” (also known by the Aramaic “Yehud”; cf. Ezr 5:8) is used to distinguish the small geographical area of the postexilic community from the larger tribal area of Judah.

3. Similarly, mention of the Persian daric coin at 1 Chronicles 29:7 would necessitate a date after the minting of this coin (ca. 515 BC).

4. The family tree of Zerubbabel (one of the early postexilic Judean leaders, ca. 537–20 BC) is noted in 1 Chronicles 3:19–21 and traces Zerubbabel’s family line for two generations (Hananiah and Pelatiah), which would bring the time frame to the mid or low 400s BC. Conversely, some claim that Zerubbabel’s family tree is traced for six or seven generations, which would amount to a later time frame. See the discussion in V. P. Hamilton, Handbook on the Historical Books (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004), 477. For the approach of seven generations from the exile of King Jehoiachin (ca. 597 BC), see A. E. Hill, 1 & 2 Chronicles (NIVAC; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003), 41 (cf. 1Ch 3:17–24).

5. S. Japhet, I & II Chronicles: A Commentary (OTL; Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox, 1993), 42.

6. Along similar lines, a portion of a scroll of Chronicles was discovered at Qumran (4Q118), reflecting composition prior to the second century BC.

7. The earlier side of this range would place the writing of Chronicles prior to the havoc in the environs of Judea (and much of Canaan and Syria) in the early fourth century BC caused by Egyptian revolts against Persian hegemony.

8. In a sense, the literary-theological message of Chronicles is first told genealogically and then narratively (cf. Hamilton, Handbook on the Historical Books, 477). This fact has given rise to the view of a two-stage composition of Chronicles, that is, 1 Chronicles 10–2 Chronicles 36 (or 1Ch 10–2Ch 34) shortly after the Decree of Cyrus (ca. 530–500 BC) and 1 Chronicles 1–9 (and possibly 2Ch 35–36) following the reforms of Ezra and Nehemiah (ca. 450–400 BC; cf. F. M. Cross, “A Reconstruction of the Judean Restoration,” JBL 94 [1975]: 4–18). While this is not necessarily a problematic view, the interrelationship across chs. 8, 9, and 10 of 1 Chronicles is not consistent with such a sharp literary break at 1 Chronicles 10.

9. W. Johnstone, 1 and 2 Chronicles; Volume 1: 1 Chronicles 1–2 Chronicles 9: Israel’s Place among the Nations (JSOTSup 253; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1997), 10–11.

10. Thus Chronicles retells earlier (biblical) history to a different audience in a different Sitz im Leben (life setting).

11. For bibliography on the relationship of Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah, see Japhet (I & II Chronicles, 3–4), and R. L. Braun, 1 Chronicles (WBC; Waco, Tex.: Word, 1986), xxv–xxvi, and xxviii. Also see the discussion in M. J. Selman, 1 Chronicles (TOTC; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1994), 65–69.

12. This view was likewise championed by Albright (cf. W. F. Albright, “The Date and Personality of the Chronicler,” JBL 40 [1921]: 104–24) and permeated the earlier edition of this commentary (J. B. Payne, “1, 2 Chronicles,” EBC first ed. [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1988], esp. 304–7).

13. Alternatively, the annalistic (or chronographic) nature of the text (see “Genre,” below), particularly the integration or earlier documents written by a variety of authors, might explain the observable thematic differences. Thus, if Ezra played a role in the composition of Chronicles, it may have been primarily in the selectivity, shaping, and cohesion of preexisting texts with preexisting thematic and theological points of emphasis. On the issues of language and authorship, see M. Throntveit, “Linguistic Analysis and the Question of Authorship in Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah,” VT 32 (1978): 9–36; W. G. E. Watson, “Archaic Elements in the Language of Chronicles,” Bib 53 (1972): 191–207.

14. See S. Japhet, “The Supposed Common Authorship of Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah Investigated Anew,” VT 18 (1968): 330–71.

15. For details concerning the fall of the southern kingdom, see comments at 2 Chronicles 36:11–19.

16. Cf. Ps 137; Ob 1–4; Arad Letter #24 (COS, 3.43K). In Hellenistic times this area came to be known as Idumea.

17. On options concerning the “seventy-year” period of the exile, see comments on 2 Chronicles 36:20–21.

18. On the time frame of the exilic period, see comments at 2 Chronicles 36:20–21. For the experiences of the exilic community in Babylonia, see R. Zadok, The Jews in Babylonia during the Chaldean and Achaemenain Periods (Haifa: Univ. of Haifa Press, 1979), and D. Smith, The Religion of the Landless: The Social Context of the Babylonian Exile (Bloomington, Ind.: Meyer-Stone, 1989).

19. Other Persian administrative districts in the vicinity of Judea/Yehud include Samaria to the north (stretching from the Jezreel Valley in the north to the border of Judea in the south from the Sharon Plain in the west to the Jordan River in the east), Gilead in the Transjordanian area to the east of Judea, the region of Kedar/Geshem/Edom to the south of Judea, Ashdod to the west of Judea on the coastal plain including some of the Shephelah (cf. Ne 2:10, 19; 4:1–12; Y. Aharoni, The Land of the Bible [rev. and enl.; trans. and ed. A. F. Rainey; Philadelphia: Westminster, 1988], 413–23; M. Avi-Yonah, The Holy Land from the Persian to Arab Conquests [536 B.C. to A.D. 640]: A Historical Geography [rev. ed.; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1977], 13–31. Finally, note that the proposal of Sanballat, Tobiah, and Geshem to “meet” in the “Plain of Ono” following the completion of the wall (cf. Ne 6) implies that this area was in the vicinity of the intersection of the borders of Samaria, Judea, and Ashdod.

20. On the political involvement of Persia within the affairs of the Judean community, see J. Cataldo, “Persian Policy and the Yehud Community during Nehemiah,” JSOT 28 (2003): 240–52; J. L. Berquist, Judaism in Persia’s Shadow: A Social and Historical Approach (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995), esp. 131–240; and S. E. McEvenue, “The Political Structure in Judah from Cyrus to Nehemiah,” CBQ 43 (1981): 353–64.

21. The dates of several of these leaders of Yehud are not certain. Note that the governors Yehezer and Ahzai may fill in some of the period between Elnathan and Nehemiah. See the analysis of data pertaining to postexilic leaders in C. Meyers and E. Meyers, Haggai, Zechariah 1–9 (AB; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1987), 9–15.

22. Most of this opposition stems from those whose heritage traced back to the mixed people groups, which resulted from the repopulation policies of the Assyrians. For detailed treatment of the postexilic setting, see L. L. Grabbe, “A History of the Jews and Judaism,” in The Second Temple Period: Yehud: A History of the Persian Province of Judah (Library of Second Temple Studies; London: T&T Clark, 2004); C. E. Carter, The Emergence of Yehud in the Persian Period: A Social and Demographic Study (JSOTSup 294; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999); P. R. Ackroyd, The Chronicler in His Age (JSOTSup 101; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1991). Also see the articles in O. Lipschits and M. Oeming, eds., Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period (Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2006).

23. Note also that by this time it had become clear that Zerubbabel was unable to restore/inaugurate the Davidic covenant (as per Jer 31–33 and Eze 37). There is little to no stress on the Davidic lineage of Zerubbabel within Chronicles, perhaps reflecting a milieu wherein focus had shifted from an individual laden with messianic imagery (cf. the presentation of Zerubbabel in Hag 2:20–23) to the collective hope of the community of believers, as perhaps implicit in the repeated expression of “all Israel” (43 times) within Chronicles. Moreover, the repeated use of “all Israel” in Chronicles might also reflect an effort to transcend the political and sectarian points of division that had developed within the postexilic community and to instill a vision for those still abroad. The difficulty of this period may have been exacerbated by the taxation and tribute requirements imposed on Yehud by Persia (cf. Carter, Emergence of Yehud, 259). In any event, sundry economic difficulties were a given in the struggling Yehud.

24. These appointments take place in the mid-fifth century BC. For the historical context of these appointments see the earlier table, “The Persian Empire and Postexilic Judea,” above. Note that the time frame of Ezra and Nehemiah (ca. 460–30 BC) is approximately 75–110 years after the Decree of Cyrus.

25. At the beginning of the time frame of Ezra and Nehemiah, the geographical extent of Yehud was largely centered in the central hill country, the Jordan valley (Jericho), and some cities in the Shephelah (cf. Ne 3:1–25; 11:29–36). By the end of the Ezra-Nehemiah period, the territory of Judea had expanded to the west and south and now extended from (approximately) Jericho-Bethel-Ono in the north to En Gedi-Beth Zur-Azekah in the south and from Emmaus and Azekah-Gezer-Ono in the west and to the Dead Sea-Jordan River in the east (see the city list in Ne 11:25–36). The summary notice of Nehemiah 11:30 describes Judean occupation as being “from Beersheba to the Valley of Hinnom.” Note that the lack of security in and around Jerusalem is implied by the necessity of casting lots to determine who would occupy Jerusalem following the completion of the wall (cf. Ne 11).

26. This intermarriage even included the son of the high priest.

27. Note that a number of the challenging aspects in Nehemiah 13 reflect an ongoing multinational/multiethnic presence in and around Jerusalem, a scenario that contributed to cultural-social fragmentation as well as spiritual compromises of various sorts. The continued fragmented nature of the broader Jewish community in the period following that of Ezra and Nehemiah is reflected in fifth-century BC Aramaic letters from the Elephantine corpus (cf. COS, 3.46–53).

28. The language of the postexilic context is referred to as Late Biblical Hebrew. On some of the distinctions and peculiar aspects of this stage of biblical Hebrew, cf. W. G. E. Watson, “Archaic Elements in the Language of Chronicles,” Bib 53 (1972): 191–207; C. H. Gordon, “North Israelite Influence on Postexilic Hebrew,” IEJ 5 (1955): 85–88; and S. Gevirtz, “Of Syntax and Style in the ‘Late Biblical Hebrew’—‘Old Canaanite Connection,’” JANESCU 18 (1986): 25–29.

29. On the different names attached to the book of Chronicles over time, see G. N. Knoppers and P. B. Harvey Jr., “Omitted and Remaining Matters: On the Names Given to the Book of Chronicles in Antiquity,” JBL 121 (2002): 227–43.

30. Most ancient Hebrew manuscripts situate 1 and 2 Chronicles at the end of the final section of the Hebrew Bible (the Writings). The threefold division of the Hebrew Bible is as follows: (1) Torah/Law (Pentateuch [Genesis to Deuteronomy]; (2) Nebiim/Prophets (Former Prophets: Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings; Latter Prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel; and the twelve Minor Prophets [Hosea–Malachi]); and (3) Ketubim/Writings (balance of the OT). The term “Tanak” comes from the initial consonants of the Hebrew terms for these three sections. Jesus’ words in Matthew 23:35 concerning the death of the priest Zechariah (probably referring to 2Ch 24:20–22) seems to imply that 2 Chronicles was understood as the end of the Hebrew canon during the time of Christ.

31. On the importance of approaching 1 and 2 Chronicles as an independent literary work, see T. Sugimoto, “Chronicles as Independent Literature,” JSOT 55 (1992): 61–74.

32. This phrase is found at 1 Chronicles 27:24.

33. As Japhet notes, “God’s rule of his people is expressed by his constant, direct, and immediate intervention in their history” (Japhet, I & II Chronicles, 44). Jerome’s name for Chronicles in the Latin Vulgate gave rise to the name “Chronicles” used today. On the importance of genre in understanding points of contrast between Samuel/Kings and Chronicles, see R. Bruner, “Harmony and Historiography: Genre as a Tool for Understanding the Differences between Samuel-Kings and Chronicles,” ResQ 46 (2004): 79–93.

34. Annals feature the use of other genres, such as lists, genealogies, cultic/temple records, and other archival documents (Kenton L. Sparks, Ancient Texts for the Study of the Hebrew Bible [Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2005], 408). Similarly, note that the book of Chronicles has a number of subgenres, including lists (e.g., kings, officials, cities, gatekeepers, temple items), genealogies (see the discussion of genealogies in the overview to 1 Chronicles 1–9), prophetic oracles, poetry, legal instruction, narrative, and speeches. On speeches and hortatory elements in Chronicles, see L. C. Allen, “Kerygmatic Units in 1 and 2 Chronicles,” JSOT 41 (1988): 21–36. The variety of subgenres in Chronicles together with content the text shares with other biblical texts (esp. Samuel and Kings) has made identifying the macrogenre of Chronicles somewhat of a cottage industry.

35. Moreover, annals are “episodic” texts in that they summarize historical events at regular intervals without necessarily being chronologically exhaustive. Similarly, in the case of Chronicles, the text is historical, given that the overview of events and people are presented in a more or less chronological order against the implied backdrop of divine agency. In the words of Japhet (I & II Chronicles, 32), Chronicles is a presentation of consequent events, focused on the fortunes of a collective body, Israel, along a period of time within a defined chronological and territorial setting. The events do not constitute an incidental collection of episodes but are both selected and structured. They are represented in a rational sequence, governed by acknowledged and explicitly formulated principles of cause and effect, and are judged by stringent criteria of historical probability. The Chronicler wrote this history with full awareness of his task, its form and meaning.

36. That is, the ruler’s deeds (or misdeeds) are commonly interwoven with references to divine favor and disfavor (cf. Sparks, Ancient Texts, 363).

37. Similarly, within the ancient Near Eastern literary setting, annals would commonly utilize chronicle accounts as sources. For example, in the Egyptian Middle Kingdom, miscellaneous records of temple and palace administration were recorded in documents known as “daybooks,” which were utilized as sources for recording the accomplishments of individual rulers in annalistic accounts (see CANE, 2435). Such daybooks might be referenced as sources that could be consulted within an annalistic account, as evidenced in the fifteenth-century BC Annals of Thutmose III (cf. CANE, 2436).

38. Cf. the numerous inscriptions of the fifteenth-century BC Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III and the seventh-century BC Assyrian monarch Sennacherib.

39. For example, note the reference to “the Book of the Wars of the LORD” in the book of Numbers (Nu 21:14) and the references to “the Book of Jashar/Yashar” in Joshua and Samuel (Jos 10:13; 2Sa 1:18).

40. Note that some of these sources may be alternative names for the same document (such as variations of references to the “Book of the Kings”). For further examples of sources in Chronicles, see Hamilton, Handbook on the Historical Books, 2; Hill, 1 and 2 Chronicles, 44; and Japhet, I & II Chronicles, 20. Note that Chronicles refers to sources at similar junctions as reflected in the book of Kings (e.g., 2Ch 12:15 and 1Ki 14:29; 2Ch 16:11 and 1Ki 15:23; 2Ch 20:34 and 1Ki 22:45; 2Ch 25:26 and 2Ki 14:18. See also J. A. Thompson, 1, 2 Chronicles [NAC; Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1994], 23).

41. Moreover, note that genealogical records often overlap with military counts (cf. 1Ch 7:9; 7:40). Also see the Overview on 1 Chronicles 1–9.

42. J. H. Walton, Ancient Israelite Literature in Its Cultural Context: A Survey of Parallels between Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1989), 114.

43. Ibid., 115–19. Walton prefers to call Chronicles a chronographic text.

44. Studies on the Chronicler all too frequently reflect an automaton parroting of a “retribution” hermeneutic for interpreting the Chronicler’s presentation of the history of Judah. For example, Braun (1 Chronicles, xxxvii) makes the following declaration: “It needs to be stated that retribution is the major, if not the sole, yardstick used in writing the history of the post-Solomonic kings.” Conversely, Selman (1 Chronicles, 62) is correct to conclude that “it seems therefore that immediate retribution is too narrow a term to express adequately the Chronicler’s theology of judgment and blessing and it would be wise to revise substantially the use of the term.” Selman, 63, is also correct to observe that the Chronicler emphasizes much more the “hope of restoration rather than the sad reality of retribution.” Also see M. A. Thronveit, “Chronicles, Books of,” in Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005), 109–12. Again, while the Chronicler may “flatten” his summaries of certain historical events (e.g., not engaging the extended drama of David’s becoming king over all Israel), the retribution approach has too many “exceptions” across the span of the Chronicler’s work to justify its usage as a central interpretive principle. For a presentation of the retribution view, see R. B. Dillard, “Reward and Punishment in Chronicles: The Theology of Immediate Retribution,” WTJ 46 (1984): 164–72.

45. Note that even the genealogical survey of the Chronicler (1Ch 1–9) exhibits selectivity (cf. the absence of various individuals such as Abel) and shaping (cf. the Chronicler’s presenting of family lines such as that of Noah in such a way as to end with the person through whom God’s redemptive plans will unfold; cf. 1Ch 1:5–27).

46. Cf. W. M. Schniedewind, The Word of God in Transition: From Prophet to Exegete in the Second Temple Period (JSOTSup 197; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1995), 249–52.

47. With respect to selectivity and shaping within the book of Chronicles, commentators frequently stress the Chronicler’s tendency to cover the history of Judah from a positive light (e.g., David’s affair with Bathsheba and treachery with Uriah are not mentioned in Chronicles). Dillard’s remark is typical: “Any fault or transgression which might tarnish the image of David and Solomon has been removed” (R. B. Dillard, “The Chronicler’s Solomon,” WTJ 43 [1980]: 290). While the Chronicler’s positive orientation is true to an extent given the text’s orientation toward covenantal hope, this perspective is commonly overstated in studies on Chronicles. For example, the Chronicler includes a significant number of instances of covenantal unfaithfulness, including David’s attempt to move the ark of the covenant that was not done “in the prescribed way” and was done without inquiring of God (see David’s words at 1Ch 15:13; cf. 1Ch 13) and David’s census that was “evil in the sight of God” (1Ch 21:7; cf. 1Ch 21). The latter is arguably more emphasized in Chronicles than Samuel (cf. Braun, 1 Chronicles, 217). In addition, the opening phraseology of 1 Chronicles 20 reminds the reader via intertextuality (albeit subtly) of the unfortunate backdrop to this Ammonite battle (namely, the Bathsheba/Uriah incident; 2Sa 11). In addition to David, the reference to the prophecy of Ahijah (2Ch 10:15) invites the reader to review the glaring critique of Solomon vis-à-vis the Deuteronomic covenant in 1 Kings 10–11 that leads to the division of the Israelite kingdom. Similarly, the phraseology at 2 Chronicles 10:4 describes the labor required of Solomon with the same terminology used of the Egyptians in their bondage of the Israelites (e.g., Ex 6:6–9). Similar examples can be given for other Judean kings, such as Asa (cf. 2Ch 16) and Jehoshaphat (cf. 2Ch 19:1–3; 20:37). In addition, a number of important “positives” for Judah are not included in the Chronicler’s account (see examples in Japhet, I & II Chronicles, 536).

48. The theological element of history gave rise to the phraseology Heilsgeschichte (“salvation history”) in biblical studies, reflecting the purposeful activity of God within history (cf. Walton, Ancient Israelite Literature in Its Cultural Context, 120–22).

49. As Selman notes (1 Chronicles, 51), the Chronicler was a “theological optimist who wanted to bring fresh hope to his people.” The Chronicler likewise shows that covenantal faithfulness extends to obedience to the covenantal structures established by God, particularly the Davidic monarchy/dynasty. For example, the stress of the poetic words of Amasai in 1 Chronicles 12:17–18 is that complete dedication, loyalty and service (“help”) to David begets not only success (lit., “peace [upon] peace” or “supreme peace”) for David but also success (again lit., “peace”) upon those who are faithful to David. On the centrality of David within the Chronicler’s message, see R. North, “Theology of the Chronicler,” JBL 82 (1963): 369–81.

50. See P. R. Ackroyd, The Chronicler in His Age, 273–89. Also see idem, “The Chronicler as Exegete,” JSOT 2 (1977): 2–32; W. M. Schniedewind, “The Chronicler as Interpreter of Scripture,” in The Chronicler as Author: Studies in Text and Texture (ed. M. P. Graham and S. L. McKenzie; JSOTSup 263; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1999), 158–80; J. Goldingay, “The Chronicler as Theologian,” BTB 5 (1975): 99–121; S. Japhet, The Ideology of the Book of Chronicles and Its Place in Biblical Thought (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1989).

51. As reflected in David’s successful move of the ark (cf. 1Ch 15:12–15), Hezekiah’s reforms (cf. 2Ch 29:11), and Josiah’s reforms (cf. 2Ch 35:5).

52. Israelite unity is at the heart of the Chronicler’s message of covenantal hope. While the Chronicler is largely silent on matters of the northern kingdom, the Chronicler incorporates praiseworthy aspects of those in the north in his genealogical survey (cf. 1Ch 5:20; 7:40) and in his narrative account, including the northern kingdom’s mercy toward southern kingdom captives (cf. 2Ch 28:9–15), the positive response of some to Hezekiah’s Passover invitation (cf. 2Ch 30:11), and even their efforts to destroy symbols of idolatry and syncretism (cf. 2Ch 31:1). The Chronicler’s emphasis on the “good days” of Judah is consistent with his intent of spurring on hope and covenantal faithfulness for his audience, while his presentation of the shortcomings of even David and Solomon ensure that the focus of his audience is on God, not humanity.

53. Hence much of the Chronicler’s presentation of the reigns of David and Solomon touches on the construction of the Jerusalem temple. Similarly, the Chronicler’s detailed presentation of the roles of priests and Levites connects with their covenantal responsibilities to facilitate divine-human reconciliation and divine-human worship/fellowship as well as to instruct God’s people concerning holiness and righteousness. The specific role of priests as teachers reflects the covenantal framework in which priests are charged by God to “teach the Israelites all the decrees the LORD has given them” (Lev 10:11; cf. Dt 33:8–11). The teaching of God’s will infuses God’s people with the spiritual direction needed to walk in a manner pleasing to him.

54. On the ending of Chronicles on a note of hope, see W. Johnstone, “Hope of Jubilee: The Last Word in the Hebrew Bible,” EvQ 72 (2000): 307–14.

55. As noted (see “Date” and “Historical and Social Background”), the theological setting of Chronicles is the eve of the postexilic setting—a hopeful contrast to the difficult historical situation in Judea seen during the Chronicler’s time period.

56. Recall that in the early decades of the return to Judea following the Decree of Cyrus in 539/538 BC, few returned. (Note that the families of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther obviously did not chose to return.) Also, recall Jeremiah’s advice to those heading into exile to “settle down” and even to pray for the welfare of their new place of residence (Jer 29:5–7). Thus, many of the postexilic Judeans hearing the message of Chronicles would have been born in exile and have had little or no emotional-spiritual connection to the Promised Land.

57. Note that both Deuteronomy and Chronicles exhort people to remember and obey their covenantal relationship with Yahweh while recounting the faithful acts of God. The recounting of the past sets the trajectory for considering the present and future. Moreover, in both there is the aftermath of divine judgment that involved prolonged time outside the land of promise as well as the presentation of hope and possibility for the future.

58. Helpful references for seeing parallel passages include J. D. Newsome, A Synoptic Harmony of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), and J. C. Endres et al., eds., Chronicles and Its Synoptic Parallels in Samuel, Kings, and Related Biblical Texts (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical, 1998).

59. Speculation may also be coupled with a preexisting hermeneutical-interpretive bent such as the “good” presentation of Judah or the (supposed) theme of immediate retribution (see note 44, above). For example, in referring to the Chronicler’s coverage of the reign of Amaziah, Dillard notes the following: “Comments in his Kings Vorlage have been expanded to provide the theological rationale for weal or woe and to demonstrate once again the validity of the author’s theology of immediate retribution” (Dillard, 2 Chronicles, 202).

60. As noted by Braun (1 Chronicles, xxii), the synoptic approach is frequently laden with “artificiality and forced exegesis” and inadequately covers portions unique to Chronicles. This commentary strives to focus on the meaning of the Chronicler’s text as received and with respect to its own biblical and theological agenda. As such, pertinent synoptic issues will not be ignored but will typically be addressed in the Notes section of the commentary. On approaching Chronicles on its own terms, see Sugimoto, “Chronicles as Independent Literature,” 61–74.

61. Moreover, points of genre may affect the (re)telling of an account in synoptic passages (compare the poetic account of the crossing of the Sea in Ex 15 with the narrative account in Ex 14). On the importance of genre in understanding points of contrast between Samuel/Kings and Chronicles, see R. Bruner, “Harmony and Historiography: Genre as a Tool for Understanding the Differences between Samuel-Kings and Chronicles,” ResQ 46 (2004): 79–93. Incidentally, different elements of detail, point of view, and literary style are not atypical for ancient Near Eastern texts reporting on the same event as reflected in the multiple works depicting Ramesses II’s battle against the Hittites at Qadesh (cf. CANE, 2436).

62. As such, synoptic challenges are typically addressed via one’s existing interpretive grid. With respect to the historical veracity of the Chronicler’s account, see S. Japhet, “The Historical Reliability of Chronicles,” JSOT 33 (1985): 83–107, and W. M. Schniedewind, “The Source Citations of Manasseh: King Manasseh in History and Homily,” VT 41 (1991): 450–61. On the genealogical section of 1 Chronicles 1–9, see G. A. Rendsburg, “The Internal Consistency and Historical Reliability of the Biblical Genealogies,” VT 40 (1990): 185–206. For an exegetical approach to synoptic issues, see W. E. Lemke, “The Synoptic Problem in the Chronicler’s History,” HTR 4 (1965): 349–63.

63. For a conservative evangelical methodology for engaging biblical challenges, see W. D. Barrick, “‘Ur of the Chaldeans’ (Gen 11:28–31): A Model for Dealing with Difficult Texts,” MSJ 20 (2009): 7–18, esp. 17–18.

64. In the texts where there is a numerical difference, Chronicles has a higher number in eleven instances and a lower number in seven instances. See the helpful chart in Hill, 1 & 2 Chronicles, 31.

65. In fact the NIV (rightly) corrects the MT 40,000 to 4,000 per 2 Chronicles 9:25.

66. See the extensive discussion in J. B. Payne, “Validity of Numbers in Chronicles,” NEASB 11 (1978): 5–58.

67. Cf. Hill, 1 & 2 Chronicles, 180.

68. Such as the notation of 470,000 versus 500,000 men of Judah noted in Joab’s census (cf. 1Ch 21:5 versus 2Sa 24:9). On the large numbers reflected here and other interpretive possibilities, see the extended discussion at 2 Chronicles 11:1.

69. Note that a difference in perspective may account for the oft-noted synoptic difference regarding “the LORD” (2Sa 24:1) versus “S/satan” (1Ch 21:1) in inciting David to conduct his ill-fated census. See a full discussion at 1 Chronicles 21:1–7.

70. Cf. Hill, 1 & 2 Chronicles, 12.

71. Similarly, the Chronicler notes the involvement of the broader community in the relocation of the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem (cf. 1Ch 13 vs. 2Sa 6).

73. Similarly, the account of Saul’s death by his own hand at 1 Chronicles 10:4–5 is described in 2 Samuel 1:5–10 as coming by the hand of an Amalekite whom Saul asked to put him out of his misery as he lay upon his spear (2Sa 1:6–9; cf. 1Ch 10:5; 1Sa 31:4). While some try to present this as a contradiction, the account of 2 Samuel can easily be understood as providing additional details of Saul’s final moments. In both scenarios, Saul has brought about his death. Note that the account in 2 Samuel has the same point of tension with the summary of Saul’s death at 1 Samuel 31:4–5.

74. As the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy states, “Since God has nowhere promised an inerrant transmission of Scripture, it is necessary to affirm that only the autographic text of the original documents was inspired and to maintain the need of textual criticism as a means of detecting any slips that may have crept into the text in the course of its transmission. The verdict of this science, however, is that the Hebrew and Greek text appears to be amazingly well preserved, so that we are amply justified in affirming, with the Westminster Confession, a singular providence of God in this matter and in declaring that the authority of Scripture is in no way jeopardized by the fact that the copies we possess are not entirely error-free.” See http://theapologeticsgroup.com

75. Careful textual criticism often brings the correct reading to light.

76. Similarly, recall the issue of the number of stalls for chariot horses noted earlier.

77. For example, note the similarity of the following Hebrew letters: ![]() /

/![]() /

/![]() ;

; ![]() /

/![]() /

/![]() ;

; ![]() /

/![]() /

/![]() ;

; ![]() /

/![]() /

/![]() /

/![]() ;

; ![]() /

/![]() .

.

78. Cf. the spelling variations noted in the Chronicler’s genealogical summary in 1 Chronicles 1–9. See examples in Selman, 1 Chronicles, 92 (n. 1). This noted, name and spelling variations may also reflect synchronic or diachronic changes in the Hebrew language (cf. examples in Hill, 1 & 2 Chronicles, 183; Japhet, I & II Chronicles, 218–19).