C H A P T E R F O U R T E E N

C H A P T E R F O U R T E E N

C H A P T E R F O U R T E E N

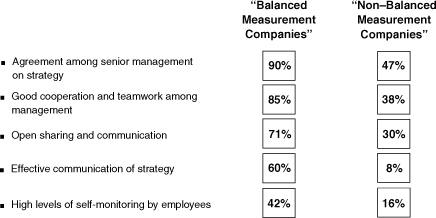

C H A P T E R F O U R T E E NWE HAVE NOW DESCRIBED THE FIVE FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES for organizations to become strategy-focused. Many organizations, since 1996, have been able to implement successful Balanced Scorecard programs. We have provided examples throughout the book of such organizations, and the evidence for success is larger than these individual stories. For example, the Metrus Group, Inc., surveyed 122 organizations to compare the performance of measurement-managed organizations with non-measurement-managed ones.1 In a measurement-managed organization, “senior management was reported to be in agreement on measurable criteria for determining strategic success and in which management updated and reviewed semi-annual performance measures in … primary performance areas.” The survey (see Figure 14-1) also showed that measurement-managed companies tend to have better teamwork at the top, better communication throughout the organization, and better self-management at the bottom. Better alignment translated into better results for the Balanced Measurement companies:

83 percent had financial performance in the top third of their industry

83 percent had financial performance in the top third of their industry

74 percent were perceived as industry leaders by their peers

74 percent were perceived as industry leaders by their peers

97 percent were perceived as pioneers or leaders on changing the nature of their industries

97 percent were perceived as pioneers or leaders on changing the nature of their industries

Figure 14-1 Impact of Measurement Systems on the Alignment and Awareness of Organizations

Source: Data from J. H. Lingle and W. A. Shieman, “From Balanced Scorecards to Strategic Gauges: Is Measurement Worth It?” Management Review (March 1996): 56-62.

A survey of 113 worldwide organizations conducted by the Conference Board for A. T. Kearney, Inc., showed that for companies linking their formal performance management systems to strategy,2

52 percent had stock performance above their competitors

52 percent had stock performance above their competitors

30 percent had the same stock performance as competitors

30 percent had the same stock performance as competitors

18 percent had performance below competitors

18 percent had performance below competitors

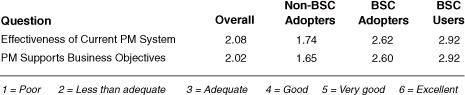

A survey conducted by the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA) concluded that Balanced Scorecard performance management systems were providing better results than traditional approaches (see Figure 14-2).

In the IMA study, Balanced Scorecard performance management systems were significantly more effective than non-Balanced Scorecard users, although neither approach was deemed more than “adequate” in the scales that were used. Perhaps more significant, when asked, “Is the Balanced yes, 30 percent answered “not yet, but will be,” and 7 percent answered “too early to tell.”

Figure 14-2 Effectiveness of the Performance Measurement (PM) System

Source: M. L. Frigo and K. Krumwiede, “Balanced Scorecard: A Rising Trend in Strategic Performance Measurement,” Journal of Strategic Performance Measurement (February/March 1999): 42-48.

But not all adopting organizations have succeeded with their Balanced Scorecard programs. Several, despite spending considerable effort, and in some cases considerable resources, could not implement the new measurement and management framework.3 Many organizations report to us that the Balanced Scorecard is “harder than it looks.”

In our first book, we provided a generic approach for building an initial Balanced Scorecard.4 We are still using essentially this process today in contemporary implementations. With more experience during the past five years, and with templates relevant for particular strategies and particular industries, the initial process can now be shortened by 50 percent or more from the sixteen weeks typically required back in 1996.5 But the basic process remains otherwise unchanged and hence does not require a new or modified treatment in this book. Even with our publication of this generic approach, some companies still experience difficulties in applying the concept. We have identified three classes of problems that inhibit the creation of Strategy-Focused Organizations: transitional issues, design issues, and process issues. We discuss each class in turn.

Some disappointments arose after major organizational changes. As one example, several companies, well along in their Balanced Scorecard implementations, were acquired or merged. The senior management team in the new organization had no interest in the new approach and abandoned the project. Even successful companies, well along in their Balanced Scorecard management system, can experience this source of failure. For example, the ACE Group of Companies acquired CIGNA Property & Casualty, one of our leading exemplars, in December 1998. ACE did not retain the management system or management team that had led CIGNA P&C, in four years, from its position at the bottom of the fourth quartile to a top-quartile performer. Within six months, CEO Gerry Isom had left, along with Tom Valerio, the vice president of transformation who had championed the Balanced Scorecard management system. AT&T Canada merged with MetroNet Communications Corporation in January 1999. CEO Bill Catucci left at the conclusion of his three-year management contract. Soon thereafter, the project champion also left. One year later, the Balanced Scorecard is being revived, but only after several of its most important champions had left. The future of the Balanced Score-card in the new ExxonMobil company was similarly uncertain as of February 2000.

Companies typically pay high premiums for their acquisitions. When they want to emphasize a cost-cutting strategy to justify the premium paid, the Balanced Scorecard may not be perceived as a valuable downsizing tool. And if the senior executives of the acquiring company are most adept at cost-cutting and driving productivity improvements, they may undervalue the growth-enhancing features of the scorecard. People who have become good surgeons—cutting waste and inefficiency wherever they can find—don’t suddenly become creative architects, designing new organizational forms and developing innovative growth strategies.

One failure reported in the literature6 actually was a story in which the scorecard won a local battle but got lost in a larger war. The first reports from the new Balanced Scorecard system made it clear that the current president’s strategy wasn’t working, so the company changed course. This was the local success as the scorecard provided feedback on a bad strategy. But the company’s owners attributed the bad strategy to the president, who was summarily fired. The new president implemented a new strategy and, in the process, discarded the Balanced Scorecard, which he associated with the old, failing strategy.

These transitional issues arose in two of our first projects in the nonprofit sector as well. The Balanced Scorecards at both the United Way of Southeastern New England (UWSENE) and the United Way of America did not survive a change in leadership. The chief executive officer at the UWSENE retired from the organization shortly after the initial scorecard project had been completed. During the project, he had not actively involved his board in developing the scorecard, believing that the board should monitor the strategy but not participate in its formulation. In the search process for a new chief executive, the board did not place high weight on finding a leader who would be committed to the new strategic performance management system. It selected a retired bank executive who felt that his immediate priorities were to deal with operational issues left by his predecessor and to ensure that each position had a complete job description. The Balanced Scorecard was new to him, he had no commitment to it, and he never implemented it, much to the disappointment of several managers who had invested much time and energy in the new system. The board, given its lack of involvement with the Balanced Scorecard, did not press the issue.

At the United Way of America (UWA), the CEO resigned unexpectedly during the project. The new CEO, hired from outside the UWA, arrived with her own management style and highly formalized planning process that she wanted to implement. The Balanced Scorecard did not fit within her planning process and did not survive the transition.

Even these two projects, however, were not complete failures. The projects at both the UWA and the UWSENE had become highly visible throughout the national United Way organization and in many other nonprofit organizations. The internal project leaders at the UWA and the UWSENE became highly visible spokespersons and trainers for nonprofits around the United States that wanted to implement the concept. So the first two pilot projects in nonprofit organizations could be viewed as local failures, but perhaps national successes. The projects demonstrated the concept and created skilled and articulate implementers who subsequently served as national resources for many other agencies.

In Chapter 13, we discussed the type of leader for whom the Balanced Scorecard represents a fit with regard to leadership and management style. This style emphasizes vision, communication, participation, and employee initiative and innovation. When such a leader is replaced by a manager who likes to be completely in control—a leader whose management style includes formal, hierarchical planning systems; extensive job descriptions to ensure that individuals operate within their functional slots; and management control systems to monitor that all subunits and employees are complying with centrally determined plans—then the Balanced Scorecard is not likely to survive the transition.

As disappointing as these events are, they represent the minority of Balanced Scorecard implementation failures. Our experience is that disappointing results are more often self-inflicted, owing to factors internal to the business rather than attributable to external events.

Some failures occur when companies actually build poor Balanced Score-cards. For example, companies may use too few measures (only one or two measures per perspective) and fail to obtain a balance between the outcomes they are trying to achieve and the performance drivers of those outcomes. Others include far too many measures and never identify the critical few. As another example, Art Schneiderman claims that some scorecards fail because they don’t contain the correct “drivers” of the desired organizational outcomes, or don’t link to specific improvement programs for the scorecard process measures.7 While this is certainly possible, our experience is that companies who imbed the scorecard in active strategic learning and improvement processes (see the discussion in Chapters 12 and 13) learn over time about the appropriate and effective drivers of organizational performance. Companies whose scorecard projects fail because of poor design are typically not designing scorecards to tell the story of their strategy.

For example, companies that build KPI scorecards are not likely to realize performance breakthroughs. KPI scorecards can drive improved operational performance, but unless they are accompanied by an explicit strategy to capture the benefits, the organization will experience disappointing outcomes.8

A similar problem exists with stakeholder scorecards. Performance measurement systems that focus on keeping customers, employees, suppliers, and the community satisfied usually lack a strategy to create sustainable competitive advantage. Both KPI and stakeholder scorecards omit critical internal processes and the linkages for driving breakthroughs for customers and shareholders.

Failures also occur when business and shared service units are not aligned with an overall strategy. We described in the introduction to Part Two how a European bank’s strategy failed, even while using the Balanced Scorecard, because it had failed to align the strategy and the scorecard of its IT division to the business units’ strategy. If each business unit follows its own path in developing a Balanced Scorecard, organizations will not have a common strategic vocabulary; they will have instead “Scorecard Babel.” Many large enterprises lost interest in the scorecard concept because each unit did it differently, with no overall coordination or linkage for group and corporate-level synergies. Senior executives lacked a coherent framework for the diverse Balanced Scorecards used by their operating and service units. Without common high-level management processes, either in deployment or feedback and review, any local Balanced Scorecard success is likely to be temporary.

The most common causes of implementation failures, however, are poor organizational processes, not poor scorecard design. We have seen at least seven different types of process failures in companies’ scorecard projects:

Perhaps the biggest source of failure occurs when the project has been delegated to a middle-management team. A clear symptom of this occurs when the team refers to the project as a metrics or performance measurement project. Often the middle management team has been actively engaged in a TQM or continuous improvement project, and the Balanced Scorecard is viewed as the logical extension of the TQM measurement philosophy. The Balanced Scorecard is certainly compatible with TQM and continuous improvement initiatives (such as the Baldrige Award in the United States or the EFQM framework in Europe). But to position the Balanced Scorecard as a quality improvement project is to miss its enormous potential to focus and align the organization on strategy, not merely operational improvements. Quality programs help organizations do things right. Strategy is about doing the right things. Middle management teams can help organizations improve existing operations. But to transform and align organizational processes and systems to strategy requires leadership from the top.

Senior management commitment is required for several reasons. First, senior management must articulate the organization’s strategy. Our research has revealed that few middle managers understand the organization’s strategy. Therefore a middle management team is unlikely to capture the organization’s strategy when building a Balanced Scorecard. Only the senior executive team has been empowered to make the difficult choices and tradeoffs required for an effective strategy. Senior management is unlikely to delegate to a middle management task force the right to select targeted customer and market segments, and to identify the value proposition that will attract, retain, and deepen relationships with targeted customers. Lacking either knowledge or decision rights about strategy (usually both), the middle management team cannot formulate a Balanced Scorecard linked to the business unit’s strategy. Senior management is also required if consensus about the strategy is difficult to achieve; the business unit CEO must serve as the tie-breaker if the project reaches an impasse because of a lack of consensus about the strategic choices.

But even more important than the senior executive team’s knowledge and authority, the process of building an effective scorecard requires an emotional commitment from them. We refer to this as the “bacon and eggs breakfast” requirement. The chicken is involved in creating this meal, but the pig makes a real commitment to it. The senior executive team needs to have real “skin in the game.” They should be investing hours of their time. Some of this time is consumed in one-on-one interviews with the project team. More important is the time spent in actual meetings where the senior executives debate and argue among themselves about the objectives and measures on the organizational scorecard and the cause-and-effect linkages on the strategy map defining the strategic hypotheses. These meetings build an emotional commitment to the strategy, to the scorecard as a communications device, and to the management processes that build a Strategy-Focused Organization. Such senior management commitment seems both necessary and also sufficient for success.

In some companies, a senior executive, such as the chief financial officer or the chief planning officer who was an important member of the senior leadership team, built the scorecard by himself. Rather than lead a team process to develop the scorecard, the lone executive made two assumptions. First, he believed that the senior leadership team was already busy dealing with many initiatives, both collectively and within their own responsibilities, and had too many meetings already on their calendars. Adding another series of meetings to build a Balanced Score-card with this team would be difficult. Second, with his analytic abilities and deep knowledge of the organization’s strategy, he could build the scorecard by himself. And he did. Arguably, he built an excellent scorecard—one that captured the organizational strategy well and had an appropriate balance of outcomes and performance drivers in the four perspectives.

Subsequent interviews, however, revealed that nothing had changed in the organization. Sure, the senior leadership team had less financial data to review and more nonfinancial statistics. But the staff executive who built the scorecard had to admit that decisions were still being made the same way, and the leadership and management style of the organization still focused on influencing the variables that had always been used by senior management.

The commitment both to the strategy and its implementation requires that the senior leadership team be actively involved in formulating the scorecard objectives, measures, and targets. Otherwise, their attitudes and their behavior will not change. If people claim that they already attend too many meetings, the project leader should use meetings already scheduled—such as the so-called strategic reviews—to drive the scorecard development process. Organizations that currently have too many meetings are the ones for which a Balanced Scorecard management system is most needed.

Of course, trying to build a scorecard with too many people can also prove fatal. The intensive interactions suggest that group sizes be kept to a number at which active discussion from all participants can occur and achieving consensus is a realistic goal. Companies can involve a broader set of people in the scorecard creation process by cascading scorecards from the top level down to divisions, business units, and departments. Also, rather than have everyone work simultaneously on the scorecard at their level in the organization, smaller subgroups can be formed to focus on a single perspective or on one of the several strategic themes that define the overall strategy. The work of the subgroups becomes integrated in a broader, larger meeting.

The opposite error of not involving the senior executive team is to involve only the senior executive team. For the scorecard to be effective, it must eventually be shared with everyone in the organization. The goal is to have everyone in the organization understand the strategy and contribute to implementing it (as described in Part Three).

When the scorecard is disseminated throughout the organization, it provides the basis for setting local initiatives and promoting knowledge and learning on key organizational processes. It facilitates the sharing of best practices, either through publicized stories in company newsletters or, more formally, through knowledge-sharing networks. Companies that do not deploy the scorecard throughout their organization lose the potential for employee innovation, creativity, and learning. They fail to make strategy everyone’s everyday job.

Some failures have occurred when a project team allows the “best to be the enemy of the good.” The team, believing in the big-bang theory of organizational change, feels it has only one chance to launch the scorecard, so it wants to produce the perfect scorecard. The team believes that it must have valid data for every measure on the scorecard, so it spends months refining the measures, improving data collection processes, and establishing baselines for the scorecard measures. Eighteen months after the start of the Balanced Scorecard project, management has yet to use it in any meeting. When interviewed, executives at the company respond, “I think we tried the Balanced Scorecard last year, but it didn’t last.” The problem was not that it didn’t last. It had never begun.

As we mentioned in Chapter 12, most successful implementations of the Balanced Scorecard start with missing measurements. Sometimes up to one-third of the measures are not available in the first few months. Yet management still uses the scorecard as the agenda for its review and resource allocation processes, thereby embedding it into the management system. The scorecard becomes a living document. Conversations take place around objectives and measures, even without specific data on the measures. And the measures themselves evolve with use and experience.

Learning by doing is a powerful paradigm. The scorecard is not a onetime event. It is a continuous management process. The objectives, the measures, and the data collection will be modified over time, based on organizational learning.

Some of the most expensive failures have occurred when companies implemented their Balanced Scorecard as a systems project rather than as a management project. These failures typically occur when an outside consulting organization, particularly one specializing in installing large systems, convinces someone in the company to hire the consultants to install a Balanced Scorecard management system. The consultants spend the next twelve to eighteen months, and several million dollars, automating all existing data-collection systems and providing a standard reporting interface, and perhaps even data mining capabilities, so that managers can have an executive information system on their desktop. The executive information system enables managers to access any existing piece of data or sort through the extensive database in many different ways. Not surprisingly, hardly anybody uses the new system. Automating and facilitating access to the thousands and millions of data observations collected in a company is not what we had in mind when we developed the Balanced Scorecard.

Recall that organizations that already had extensive databases and systems still lacked up to one-third of the measures on their initial Balanced Scorecard. Automating and mining existing data would never identify the critical missing measurements. Recall as well the notion of balance. Giving managers access to more than 100,000 possible pieces of data is not a substitute for having an organized strategy map, with cause-and-effect linkages across the twenty to thirty measures that truly represent the most important strategic variables.

And, most important, consider the issues raised by the first two pitfalls. Organizations that delegate the scorecard to an outside systems consulting and implementation firm will rarely engage the senior management team in a strategic dialogue. It should not be surprising, therefore, that the senior managers don’t use their new desktop information system and certainly never manage the company differently just because they now have direct access to the minutiae of all the data in their company.

The Balanced Scorecard must start with a comprehensive strategic review that engages the managers within the organization. It cannot be delegated to an IT group or a systems implementation firm. The scorecard should start with a management process, not a systems process.

Systems and technology are important, as we discussed in Chapters 11 and 12. By imbedding the scorecard into ongoing data collection, information reporting, and learning and review processes, the scorecard becomes a living part of the organization. But the systems and technology input comes after the initial management process that generates the objectives, measures, targets, initiatives, and linked scorecards throughout the organization. And more important, the front-end management process generates the commitment to manage the organization via the scorecard.

Hiring consultants who treat the Balanced Scorecard as a systems project is related to another pitfall: hiring consultants for whom the project represents the first scorecard implementation they will have done. After our articles and book were published, many consulting organizations responded to companies’ requests for assistance in implementing the scorecard. All too often, unfortunately, consultants just renamed whatever measurement or information systems approach they were accustomed to delivering as “the Balanced Scorecard.” Using inexperienced consultants or consultants who deliver their favorite methodology under the rubric of the Balanced Scorecard is almost surely a recipe for failure.

This point was driven home forcefully to us when we learned of a large financial institution that had just spent several million dollars on a Balanced Scorecard project that was widely perceived as a major failure. We made an appointment to meet with the president of the division to learn what had occurred. Was it a problem with the scorecard concept and management system that we needed to address? Upon arrival at the meeting, the president told us immediately:

We screwed it up; the scorecard is fine. I saw it work with great effect at my previous company. But the project wasn’t positioned well in this organization, and the consultants we hired, while claiming great expertise on the subject, didn’t have a clue about how to organize the project or implement the system.

We like the idea of tying compensation to the strategic measures on the scorecard, as we described in Chapter 10. Companies use the link to compensation as a powerful lever to gain the attention and commitment of individuals to the strategy. But some companies skip the strategy translation part of the scorecard process. They just introduce new, nonfinancial measures to their incentive compensation plan. This can happen when companies build a stakeholder scorecard by including indicators on environmental performance, employee diversity, and community ratings. Managers, of course, now focus more attention and energy on the new indicators. Performance on the nonfinancial measures improves. But overall financial and customer performance do not improve, leading to some tension and conflict in the organization. Managers wonder why the Balanced Scorecard did not work for them. The answer is quite obvious. Scorecards used to introduce nonfinancial indicators into a compensation plan do not capture how the nonfinancial measures lead to improved customer and financial performance. The link to compensation drives financial performance when based on a strategy scorecard, not a stakeholder or KPI scorecard.

Many companies are already enjoying benefits from their Balanced Score-card management systems. Implementation failures do occur, but most are self-inflicted. After a change in leadership or change in control, organizations may revert back to traditional management systems because the new leader has not experienced the benefits from operating a Strategy-Focused Organization. Other failures represent breakdowns in implementing the concept, such as inadequate sponsorship and commitment from the senior management team, designing scorecards not linked to a strategy, using inexperienced consultants, and deploying inadequate resources.

In this book, we have provided the principal steps that enable the Balanced Scorecard to create the Strategy-Focused Organization:

The journey is not easy or short. It requires commitment and perseverance. It requires teamwork and integration across traditional organizational boundaries and roles. The message must be reinforced often and in many ways. But organizations that sustain the effort and maintain adherence to the five principles will avoid the pitfalls and be on the road to breakthrough performance.

1. J. H. Lingle and W. A. Schiemann, “From Balanced Scorecards to Strategic Gauges: Is Measurement Worth It?” Management Review (March 1996): 56-62. See also W. A. Schiemann and J. H. Lingle, Bullseye: Hitting Your Strategic Targets through High-Impact Measurement (New York: The Free Press, 1999).

2. “Making Strategy Pay,” a report describing a 1999 research study performed for A. T. Kearney by The Conference Board (Chicago: A. T. Kearney, 1999).

3. B. Birchard, “Where Performance Measures Fail,” p. 36 in “Closing the Strategy Gap,” CFO Magazine (October 1996); J. Kersnar, “Hitting the Mark,” CFO Europe (February 1999): 46-48; A. Schneiderman, “Why Balanced Scorecards Fail,” Journal of Strategic Performance Measurement (January 1999): 6-11.

4. Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, “Building a Balanced Scorecard: The Process,” pp. 300-10 in The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

5. See, for example, the Balanced Scorecard Fast Track Development program offered by the Balanced Scorecard Collaborative (http://www.bscol.com).

6. See Birchard, “Where Performance Measures Fail.”

7. See, for example, Schneiderman, “Why Balanced Scorecards Fail.”

8. See, for example, the problems encountered after implementation of a corporate scorecard at Analog Devices in R. S. Kaplan, “Analog Devices: The Half-Life System,” 9-190-061 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 1990). The subsequent decline in performance is described in the teaching note to the case (5-191-103) and in J. D. Sterman, N. Repenning, and F. Kofman, “Unanticipated Side Effects of Successful Quality Improvement Programs: Exploring a Paradox of Organizational Improvement,” Management Science 4, no. 2 (1997): 503-21.