Introduction

I.1. Interfirm alliances as a source of innovation and the role of private equity

Cooperative approaches in the shape of strategic alliances between companies are a source of innovation and a factor for economic growth in developing economies. Alliances are particularly important for the development of SMEs, which are predominant in Europe, and for which internal resources are often limited [SCH 06].

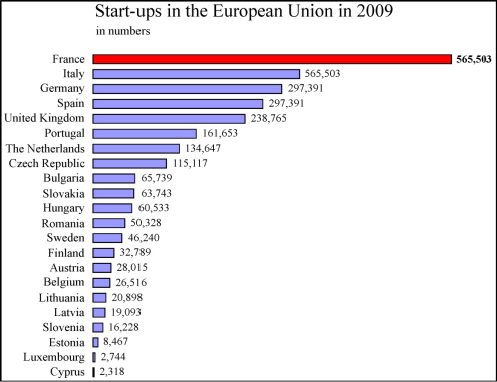

In France, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for nearly 99.9% of all companies (2010 data). Nationally, they employ 52% of employees and generate 38% of turnover, which is almost half of the value added (49%) [POR 10]. The creation of SMEs is on the rise. In 2012, France recorded nearly 549,976 new business start-ups [APC 13]. According to the latest Eurostat comparison in 2009, France had the highest number of business start-ups in the European Union (Figure I.1).

These figures highlight the importance of economic policies and measures aimed at SME development [MCC 10]. Several policies have been put in place to foster alliances and networking among SMEs [SCH 06]. The European cluster policy is an example of such a policy, as well as its French counterpart, the “Pôles de compétitivité” policy, which was launched in 2004. In the wake of Silicon Valley1, they aim to encourage interactions between various actors through the creation of appropriate environments for intensive knowledge exchange and synergies between them. Within a given territory, they help to bring together private equity firms (PEFs, that usually specialize in venture capital), SMEs, large groups, and research institutions such as universities.

Figure I.1. Business start-ups in the European Union in 2009

(source: Insee, Eurostat)

Private equity is relevant in this field because it is one the most significant source of financing for SMEs (which are usually unlisted) and therefore innovation. By their very nature, PEFs are active investors. In addition to providing capital, they provide managerial assistance to the companies they support. McCahery and Vermeulen [MCC 10] highlight the importance of the contribution of these complementary services through the example of the Japanese private equity market, where the performance is lower than in the United States and Europe. Unlike in the latter two countries, Japanese PEFs are passive investors and are therefore limited to capital injections. The authors also suggest that there are signs that governments are aware of the importance of the non-financial services provided by PEFs for the development of SMEs and innovation. After the financial crisis, government policies aimed at promoting private equity or, as mentioned above, networking among stakeholders were strengthened in various countries, including France [GLA 08; MCC 10, pp. 13–14].

In this study, we consider the following questions:

- – Can PEFs play a role in networking and forming alliances for the companies they support?

- – As active investors, do they provide companies with networking services in addition to managerial assistance, thus creating an ideal platform for their development and external growth?

French PEFs, which are the subject of our study, are involved in several ways in the formation of strategic alliances for the companies they support. For example, Axa PE, from a press release in 20092: “The Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec and AXA Private Equity have entered into a partnership to better support Québec- and European-based businesses with international development prospects […] This partnership is fully in keeping with the Axa Private Equity tradition to help the businesses we invest in to develop both industrially and geographically […] The partnership hopes to address global distribution, supplier search, research and development joint ventures, strategic alliances and international takeovers”. Since its creation over 40 years ago, one of the pioneering PEFs on the French market, Siparex Group, distinguished itself by setting up Club Siparex in 1982. This club’s mission is to: “Contribute to the creation of value in the companies the Group is investing in through exchanges and targeted networking”3. In a similar vein, Demeter Partners has written on its website: “Since 2007, the Demeter Club regularly brings together the CEOs of DEMETER and DEMETER 2 portfolios, with the following objectives: […] to develop industrial and commercial synergies amongst the companies of the DEMETER and DEMETER 2 portfolios; to let the companies benefit from our network of experts and institutional relations”4. In addition to these targeted examples, most French PEFs indicate that they make their network of contacts available to supported companies in order to help them create value for their projects.

At first glance, however, any information on such practices ends there. There are no concrete examples of alliance formation where one or more French PEFs are involved. Neither France Invest (formerly Afic, Association française des investisseurs pour la croissance), which brings together most French PEFs, nor its European counterpart, Invest Europe (formerly EVCA, European Venture Capital and Private Equity Association), nor INSEE, nor on a European scale, Eurostat, have gathered any further information on these practices. Thus, we shall take a look at the existing literature.

I.2. Lessons from the literature

A quick review of the literature suggests that the phenomenon is not new in itself. The formation of alliances for start-ups supported by private equity was mainly seen in the field of biotechnology in the 1980s and 1990s, when private equity was booming in the United States. In general, alliances between biotech start-ups and large pharmaceutical companies have already been studied (for example [STU 99]. However, such studies do not analyze the direct role of PEFs in forming alliances. Overall, the existing analyzes focus on the impact of the presence of an alliance and, in particular, the reputation of the alliance partner on the success of the start-up. Success as such is usually measured by the rapidity of exit of PEFs and the type of exit. A quick exit through an initial public offering (corresponding to an IPO of the supported company) is considered to be an indicator of success. More recently however (in the 2000s), an emerging literature has been seeking to analyze more concretely the particular role of PEFs in forming alliances.

Existing studies can be subdivided into two categories: those that attempt to directly address the question of the role of PEFs in forming alliances for supported companies, and those that question whether PEFs, or alliances, can be complementary or alternative mechanisms to the development of start-ups and their access to finance. Most studies cover the field of venture capital, which is a specific component of the private equity spectrum (ranging from support for generally unlisted companies, from start-up, to turnaround). In addition, studies on venture capitalists and alliances as alternative or complementary mechanisms are usually focused on the study of venture capitalists that are subsidiaries of an industrial group. All the studies borrow arguments from theories that fall within the efficiency paradigm. Mostly, contractual theories are used. Some studies use arguments from knowledge-based theories.

Studies in the first category focus on two points:

- – the role of venture capitalists in forming alliances for the companies they support;

- – the impact of the alliances created on the success of the start-ups that form them.

Hsu [HSU 06] analyzed the extent to which venture-capital-supported start-ups form interfirm alliances, compared to a sample of start-ups with similar characteristics (at the stage of development and the environment in which they operate) but which are not supported by venture capital. He found that both the presence of a venture capitalist and its reputation had a positive effect on the formation of alliances for supported companies and allowed for more frequent IPOs. Colombo et al. [COL 06] focused on the determinants of high-tech start-up alliances. In particular, they showed that the presence of sponsors such as venture capitalists and their reputation have a positive effect on the formation of alliances. Lindsey [LIN 02, LIN 08] argued that the likelihood of forming alliances for venture capital backed companies is higher when the alliance partners share a single venture capitalist. These are alliances formed within the investment portfolio of a venture capitalist (an “intraportfolio” alliance, as we will call it in this book). Like Gompers and Xuan [GOM 09], Lindsey argued that venture capitalists can reduce the intensity of informational asymmetry problems and uncooperative behavior among future alliance partners. Wang et al. [WAN 12] were interested in the views of venture capitalists. For these authors, forming alliances enables venture capitalists to reduce the risks associated with a hostile environment for their equity interests. They also found that the firms use alliance formation as a substitute for capital contribution and that the diversity of syndication partners has a positive impact on the number of alliances formed.

The second category includes studies by Ozmel et al. [OZM 13], Hoehn-Weiss and LiPuma [HOE 08], as well as Dushnitsky and Lavie [DUS 10]. These authors examined the extent to which venture capitalists and alliance partners are complementary or alternative mechanisms in company IPO decisions. Generally, their studies involved venture capitalists that were subsidiaries of an industrial group. Ozmel et al. [OZM 13] explicitly addressed the trade-offs made by start-ups in the biotechnology sector with regard to the choice of raising funds either through venture capital or through alliance partners. In the latter case, this was usually the affiliation of a start-up with a large pharmaceutical group. The alliance allows the start-up to obtain funds from the industrial group which, in turn, has an interest in investing in the start-up for R&D reasons. The results of the study show that the more the start-ups develop such alliances, the more likely they are to form a new alliance and simultaneously reduce the likelihood of venture capital support. On the other hand, the more the start-ups raise venture capital, the more likely it is that they will form an alliance and raise venture capital again.

In terms of IPO success, the formation of alliances has a higher impact than venture capital support. Thus, Nicholson et al. [NIC 05] showed that the formation of alliances for a biotech start-up can be seen as a sign of quality by other market players, which may be an explanation for the result found by Ozmel et al. [OZM 13].

Hoen-Weiss and LiPuma [HOE 08] analyzed how venture capital financing from an industrial group’s subsidiary, as well as alliance building and the interaction between the two can influence the internationalization of start-ups. The only fact that has a significant connection with the internationalization of start-ups would be the affiliation within an alliance of a large industrial group that is established and reputable on the market.

Dushnitsky and Lavie [DUS 10] showed that, on a sample of early stage technology start-ups, both venture capitalists and alliance partners can provide access to complementary resources. In their sample, venture capital investments increased initially with the formation of alliances, followed by a decrease.

Chang [CHA 04] analyzed the effect of the presence of a venture capitalist (via its reputation and the amount of capital it injects into the companies it supports) and the network of alliances (via the number of alliances formed and reputation of alliance partners) on the performance of new technologies (digital start-ups), measured by the time it takes to go public. This has a positive effect. Stuart et al. [STU 99] also found a positive link between the affiliation of start-ups in the biotechnology sector with reputable partners (reputable venture capitalists or partners with reputable alliances) and the rapidity of exit and market capitalization of start-ups at the time of the IPO.

On a more macroeconomic level, McCahery and Vermeulen [MCC 10] showed that there was a structural change from the involvement of large industrial groups in financing innovation following the financial crisis. Although large industrial groups used to set up their own private equity subsidiaries, they began to form more alliances either with PEFs or directly with start-ups [MCC 10, p. 27 sq.]. This resulted in more active involvement of industrial groups in the start-up selection processes and in other decisions relating to start-ups. According to the authors, this may be accompanied by problems for start-ups that are related to the potential opportunism of these large groups. In particular, the authors raised the question of whether government policies aimed at creating environments that are conducive to innovation should be revised, in order to avoid these potential problems by strengthening protections for start-ups, which are in theory more vulnerable than large industrial groups. Like Silicon Valley, lawyers and other professionals may also be involved, particularly in considering contractual solutions to protect start-ups. The authors concluded by proposing recommendations for government intervention in order to preserve a level of trust between the stakeholders.

This brief review of the literature already allows us to draw up some theoretical and empirical observations. From a theoretical point of view, the current literature is mainly based on contractual theories, though some works borrow arguments from knowledge-based theories. In general, the literature focuses on the additional services (beyond financial inputs) provided by PEFs to the companies they finance and their impact on value creation (for example [LER 95, SAP 96, HEL 02, BAU 04].

There are two main inaccuracies in the models observed. First, with the exception of the Lindsey study [LIN 08, LIN 02], the authors of studies do not specify whether the observed alliances are formed between companies that share the same venture capitalist, or if they are formed between companies supported by different venture capitalists, or if only some of the companies in the alliance are supported by venture capital. Thus, it can be assumed that the role of a venture capitalist in forming alliances differs if the alliance is formed within its own investment portfolio or with external alliance partners. This lack of distinction makes it difficult, or at least limits our ability, to compare results from the existing literature.

Second, it is not always obvious if a study is on private equity or whether it is merely limited to the venture capital spectrum. Although the respective terms appear within the studies, they are not always used appropriately. In order to truly identify whether a study is about private equity in general or one of its components, we recommend taking a closer look at the study sample. Unfortunately, even when considering the sample in detail, studies are not always clear enough, for example, they might not provide information on this subject. Sometimes “venture capital” may be referred to but the sample actually involves PEFs, which are not restricted to supporting companies at an early stage (venture backed-firms).

At the empirical level, most models are tested within the biotechnology or new technology sectors, and are done in an American context. Some rare works (usually by Colombo) apply their research to Italy. Ultimately, most studies seem to focus on venture capital and some restrict their analysis to venture capitalists that are subsidiaries of an industrial group or a company (corporate venture capital).

I.3. General questions considered in the study

In this study, we measure the extent of this phenomenon in France. More specifically, the study aims to explain the role of French private equity firms in forming alliances and their impact on value creation. It is therefore in line with the presented work but focuses on the French private equity market as a whole. It is not limited to venture capital. The problem is the following.

Based on the assumption that French PEFs are involved in forming alliances, we seek to answer two major questions:

- – How are French PEFs involved in forming alliances for the companies they support?

- – Why do they intervene? Why are they involved in forming alliances for the companies they support?

These questions can be considered from two points of view: that of the SMEs that form an alliance in the presence of a PEF and that of the PEF. In addition, we distinguish between two types of alliances: “intra” and “extra” alliances. The first concerns any type of alliance between companies that are supported by the same PEF. Alliances are therefore formed within – “intra” – the investment portfolio of a PEF. The second concerns alliances formed between at least one company supported by a PEF and another company that is not supported by the same PEF. Although an alliance may be formed between more than two companies, our explanations will be limited to alliances formed between two companies. However, our terms can obviously be applied to other alliances.

The problem is considered under the angle of shareholder value creation. In theory, the aim of this book is to answer the aforementioned general questions from a value creation point of view. This raises a third question that we seek to answer through the first two questions: what levers do PEFs use to create value through the creation of alliances for the companies they support?

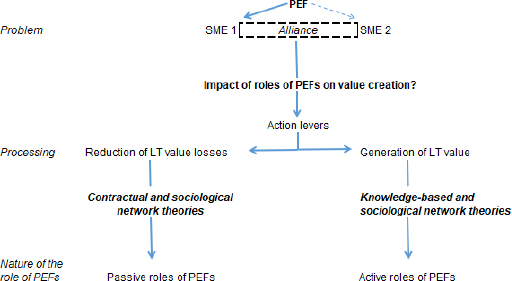

Generally speaking, value creation can be achieved through two strategic levers: the reduction of losses linked to the presence of (long-term) strategic costs, and the creation of value through generating long-term strategic gains, which are the source of organizational rents. Contract theories allow us to consider the problem in terms of presence or absence of costs (transaction and agency costs). These theories are mostly mentioned in the aforementioned literature. They highlight the “passive” roles of PEFs in forming alliances. The term “passive”, which may seem extreme, is used to illustrate an action on value through cost reduction levers (transaction and agency), as opposed to a more “positive” intervention on value through the creation of growth opportunities, with which we associate the term “active”. Knowledge-based theories, on the other hand, allow the problem to be analyzed from the point of view of long-term value creation itself, in other words a truly “active” role. They are adapted to the analysis of the second lever and remain relatively little used and exploited in the literature that is relevant to our problem. They highlight active, intentional roles – in the sense that there is a genuine intention to “actively” create value – of PEFs in forming alliances. Ultimately, using sociological network theories, we complement the argumentation that results from analyzing the problem from the angle of contractual and knowledge-based theories. Figure I.2 gives a schematic overview of the problem, its theoretical process and the nature of the role of PEFs in forming strategic alliances for the companies they support, which this theoretical process highlights.

Figure I.2. Schematic overview of the problem, its processing and the nature of PEF roles that are thus highlighted

Considering our research question through both contractual and knowledge-based approaches leads us to adopt a rather broad definition of strategic alliances (defined in section 1.2), which allows for both contractual and knowledge-based analyzes. As such, our analysis is similar to studies that propose a synthetic or dual approach [COH 05] to alliances and cooperation between companies [KOG 88, COM 99, OER 01, CLA 02, HEI 02, CHE 03].

The use of multiple theoretical frameworks allows us to refine the general questioning of how and why French PEFs are involved in forming strategic alliances for the companies they support. As we will see in the section on the theoretical analysis of the question (Chapter 2), using contractual theories that are adapted to analyzing the first lever leads to more concrete questions:

- – Do companies that are supported by PEFs face costs when forming alliances?

- – If so, does the presence of a PEF reduce these?

- – The next question is then whether PEFs are the only mechanism that can potentially reduce costs, or are there other ways?

The second lever raises questions about corporate intervention of PEFs in the creation of value itself through the formation of alliances. As we will see in our theoretical analysis, this looks at whether they are involved in creating growth opportunities or new skills and knowledge that will ensure a long-term competitive advantage for the companies they support.

From the point of view of PEFs, how do they benefit from forming alliances? Can they attempt to extract rents from alliance formation? Do PEFs provide this service in order to differentiate themselves from the market, or do they do this in search of social legitimacy?

The empirical challenge of our study is threefold:

- – first and foremost, we test our research hypotheses that result from the use of contractual and knowledge-based theories, which are supplemented by sociological network theories, and we compare the relative weight of variables from the different theoretical frameworks within a same study;

- – as we will apply our research to the field of private equity in France, our empirical study also allows us to see whether the main conclusions proposed in the current literature, which are essentially based on contractual arguments, are true and valid in the French context;

- – finally, we seek to empirically test not only the generality of our hypotheses to see if they apply to all French PEFs, but also to check the plausibility of the mechanisms underlying the causal links that are put forward.

The methodology we use is based on a multimethod study, combining a multiple case study and an econometric study.

Our study reveals that French PEFs are involved in forming alliances via two levers: contractual and knowledge. On a managerial level, this makes it possible to enhance the value of the relational service that French PEFs declare they provide. Beyond this, the study provides an explanation for the phenomenon observed after testing the causal mechanisms underlying these explanations. The results show that French PEFs play both an active and passive role in forming alliances for their investments. Thus, on the one hand, they are the basis for value creation that results from the transaction. On the other hand, they play a role in reducing value losses that are associated with cost-incurring inefficiencies as suggested by the current literature.

From the point of view of PEFs, their contribution in alliance formation appears to be motivated by a desire to differentiate themselves within the private equity market by providing an additional service to supported firms, beyond managerial assistance and provision of capital. In the specific case where a PEF takes the legal form of a joint-stock company and has a region or the State in its capital, this type of investor may also encourage the formation of alliances in order to generate commercial synergies between actors within a region. From the point of view of the SMEs that form the alliances, the presence of a PEF allows them to, on the one hand, detect growth opportunities that can be implemented through the formation of alliances. On the other hand, PEFs can help overcome the difficulties these firms face in forming alliances. This study will make it possible to identify the methods of intervention of PEFs.

The results of this study also support the joint use of contractual and knowledge-based theories to explain the phenomenon, although knowledge-based argumentation is more frequently confirmed on the whole than contractual argumentation. Finally, this study shows that certain arguments put forward by the literature do not hold in the French context.

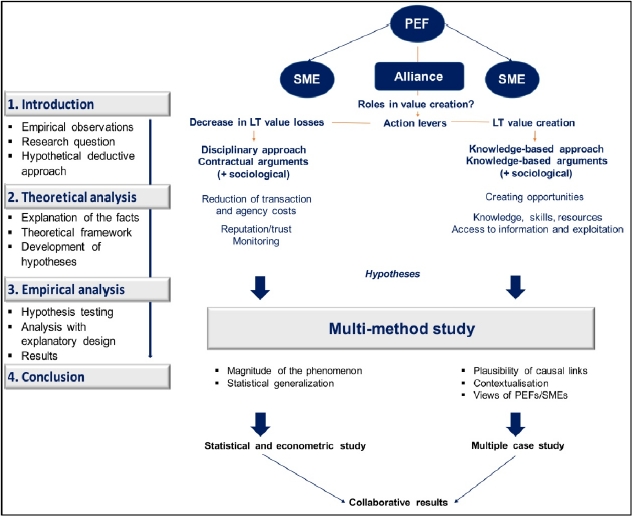

I.4. General study outline

As is the usual way for studies, this study will include an initial introductory part, a second part on the theoretical analysis of the research question, a third part that empirically tests the theoretical concept, followed by a general conclusion. Before detailing the various points, Figure I.3 shows the plan.

In Chapter 1, we present the problem. We clarify the concepts of private equity (section 1.1) and strategic alliance (section 1.2). The part about private equity includes a section on its main characteristics (section 1.1.1). This is followed by an introduction to the French market (section 1.1.2), which will enable us to position it in the world market (section 1.1.2.1) and present the different forms of PEFs (section 1.1.2.2), as well as the different players that are involved (section 1.1.2.3). After introducing the concept of a strategic alliance (section 1.2), we will then present the strategic alliance formation activity of French PEFs (section 1.3). This will make it possible to identify the importance of the phenomenon being studied. We will discuss the favorable environmental conditions for alliances to be formed on the French market (section 1.3.1) and present the first descriptive data on the phenomenon from our own survey (section 1.3.2).

In Chapter 2, we tackle the theoretical analysis of our research question from a value creation perspective. The roles of French PEFs in alliance formation are thus studied within the efficiency paradigm, respectively, in light of contractual theories (section 2.1), knowledge-based theories (section 2.2) and sociological network theories in order to complete the argumentation of the first two theoretical frameworks used (section 2.3). These three parts are built on the same principle. In a first point, we begin by presenting the bases that are necessary for understanding the theories used (sections 2.1.1., 2.2.1 and 2.3.1). After summarizing this introduction, we then apply the theory to our problem (sections 2.1.3, 2.2.2 and 2.3.2).

Figure I.3. Schematic overview of the general study outline

We successively apply contractual theories (transaction cost theory, positive agency theory) to our research question (section 2.1) according to the views of SMEs and PEFs. On the one hand, this allows us to understand the difficulties faced by private equity backed companies in forming alliances. On the other hand, this highlights the role of French PEFs in solving the encountered problems, from the perspective of reduction of value losses because of costs (transaction and agency). The roles of PEFs in building ex ante confidence in alliance formation and a disciplinary (or advisory) role once the alliance is formed can thus be brought forward. From the point of view of PEFs, the question then arises on their own interests in forming alliances for the companies they invest in.

However, the roles of French PEFs as highlighted by the contractual analysis remain passive in terms of alliance formation. By their very nature, PEFs are active investors, not passive investors. In a second part (section 2.2), knowledge-based theories allow us to focus on the intentional roles of French PEFs in forming strategic alliances for their investments. We begin by presenting the theoretical bases that are required to understand the arguments that can be adopted from these theories (section 2.2.1). We once again apply the theory to our research question from the perspectives of the alliance SMEs and PEFs (section 2.2.2). The analysis highlights the roles of PEFs in building growth opportunities and creating new knowledge for supported companies through alliance formation. They can also play a role in facilitating initial exchanges between future alliance partners. From the PEF’s perspective, alliance formation can be seen primarily as a strategic positioning of PEFs, enabling them to differentiate themselves in the private equity market. After a summary of the analysis (section 2.2.3), we pitch the contractual theories against the knowledge-based theories (section 2.2.4) and discuss the complementary of these theoretical frameworks within our study (section 2.2.5).

In a third point, sociological network theories are then used to supplement the contractual and knowledge-based argumentation (section 2.3). Primarily, we apply the concept of social capital. This theoretical analysis ends with a proposal of a theoretical explanatory model of the studied phenomenon (section 2.4).

Chapter 3 then tests this theoretical framework. We begin by explaining our methodology, which consists of a multimethod study, comprising both an econometric study and a multiple case study (section 3.1). The theoretical framework (section 3.2) is then tested. The econometric study, which is based on our own survey, tests the adequacy of our research hypotheses on the French private equity market (section 3.2.1). The main purpose of the multiple case study is to test the plausibility of advanced causalities (section 3.2.2). The results of the two studies can then be compared in order to draw conclusions about the proposed theoretical model (section 3.2.3).

This book will end with a general conclusion where we discuss the possible limitations and extensions of the work.