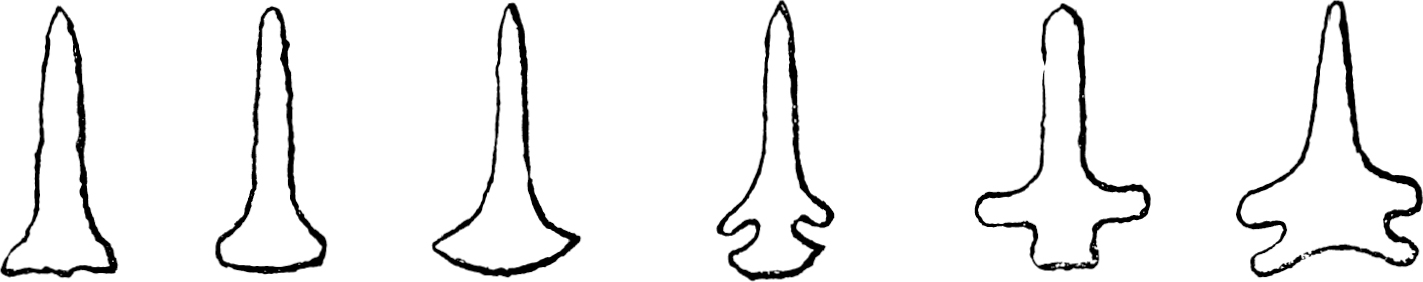

An anomaly in arrowpoints should not be overlooked. One of the prehistoric implements of America is that which usually has been called the perforator or drill, though sometimes, jocularly, “hairpin.” It consists of the bore or pile, which is round or nearly so, pointed as though suitable for drilling or boring, with a stem or base after the fashion of arrowpoints. It has usually been supposed that this spreading base was to be held between the thumb and fingers, gimlet fashion, and used as a drill. Some of these implements appear to have been made primarily for this purpose, while others have the full and complete base, stem, shoulders, and sometimes barbs, of the stem end of an arrowpoint, and of these it has always been said or supposed, that the perforator or drill had a secondary use, and was possibly a broken arrowpoint. The blade is chipped away on either edge until the pile or bore is very nearly round and quite pointed. These have never been classed as arrowpoints or spearheads, but it is curious to remark that the only wounds shown in the two human skulls in the U. S. National Museum should have been made by stone implements or arrowpoints of this peculiar kind. Reference is made to figs. 198 and 200, where the skulls are represented with the wound and weapon as originally found, but the latter are also withdrawn and shown in their entirety. With this apparently conclusive evidence of their use as arrowpoints, they can not be omitted from this classification.

The bow and arrow as a projectile engine comprises several parts. This paper has treated only one, the arrowpoint or pile, as it is called in archery, for the reason that the investigation has been confined in point of time to the prehistoric, and all or nearly all parts of the engine, except the stone arrowpoint, have decayed or been destroyed by lapse of time. Bows with their strings, arrow shafts with their feathering, spear shafts, and, with a few excepted illustrations to be given, knife handles, have all perished. Dr. Otis T. Mason says:1

Of the ancient inhabitants of this continent the perishable material of arrows constituting the shaft and other parts has rotted and left us naught but the stone heads. Even those of bone and wood and other material have passed away, so as to leave the impression that the Indians of this eastern region used only stone; but all authorities agree that other substances were employed quite as frequently as the last named.

YEW BOW FROM PREHISTORIC LAKE DWELLING.

Robenhausen, Switzerland.

A single specimen of a bow was preserved in the bog peat of the lake dwellers and has been found and exhibited to the eye of man—“only this, and nothing more.” Fig. 192 represents the original of this specimen, now in the museum in Zurich, Switzerland, and found by Jacob Messikommer in the peat bog which was originally the lake dwelling of Robenhausen. The author has visited this station more than once and has found many pieces of wood well preserved. The piles themselves in this, as in all other pile dwellings, are of wood, and almost every museum possesses specimens in certain stages of preservation. The work on this specimen identifies it specifically as a bow. The end “horns” show the notch for the retention of the bow string, while the center has a certain style of decoration.

Those interested in ancient bows, or bows of primitive, not prehistoric, peoples are referred to Doctor Mason’s paper.

Mention has previously been made of the possibility of the use by prehistoric man of the implements described in this paper for other purposes than as arrowpoints or spearheads (pp. 823, 935, 938, 977). The importance of the subject requires further investigation.

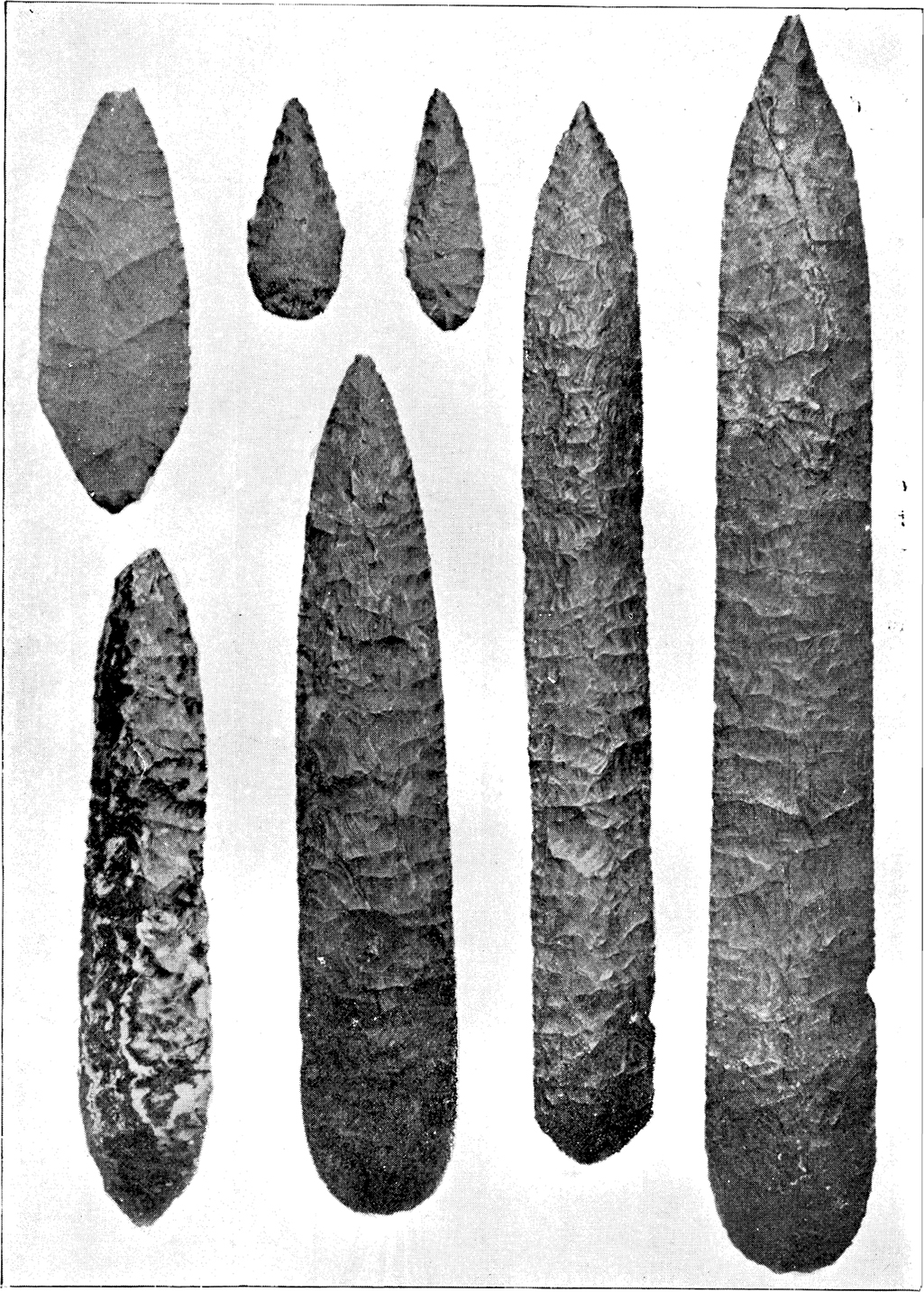

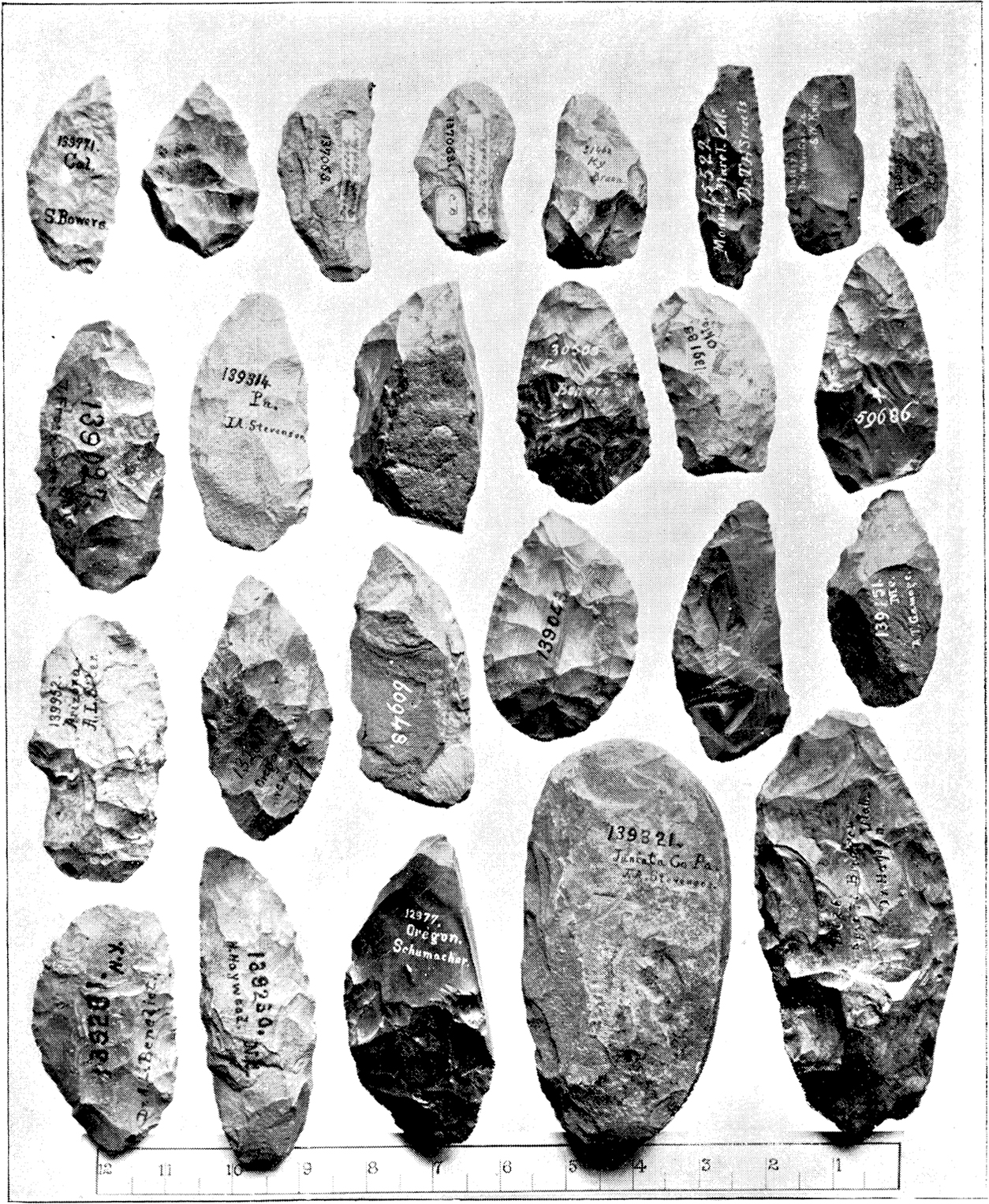

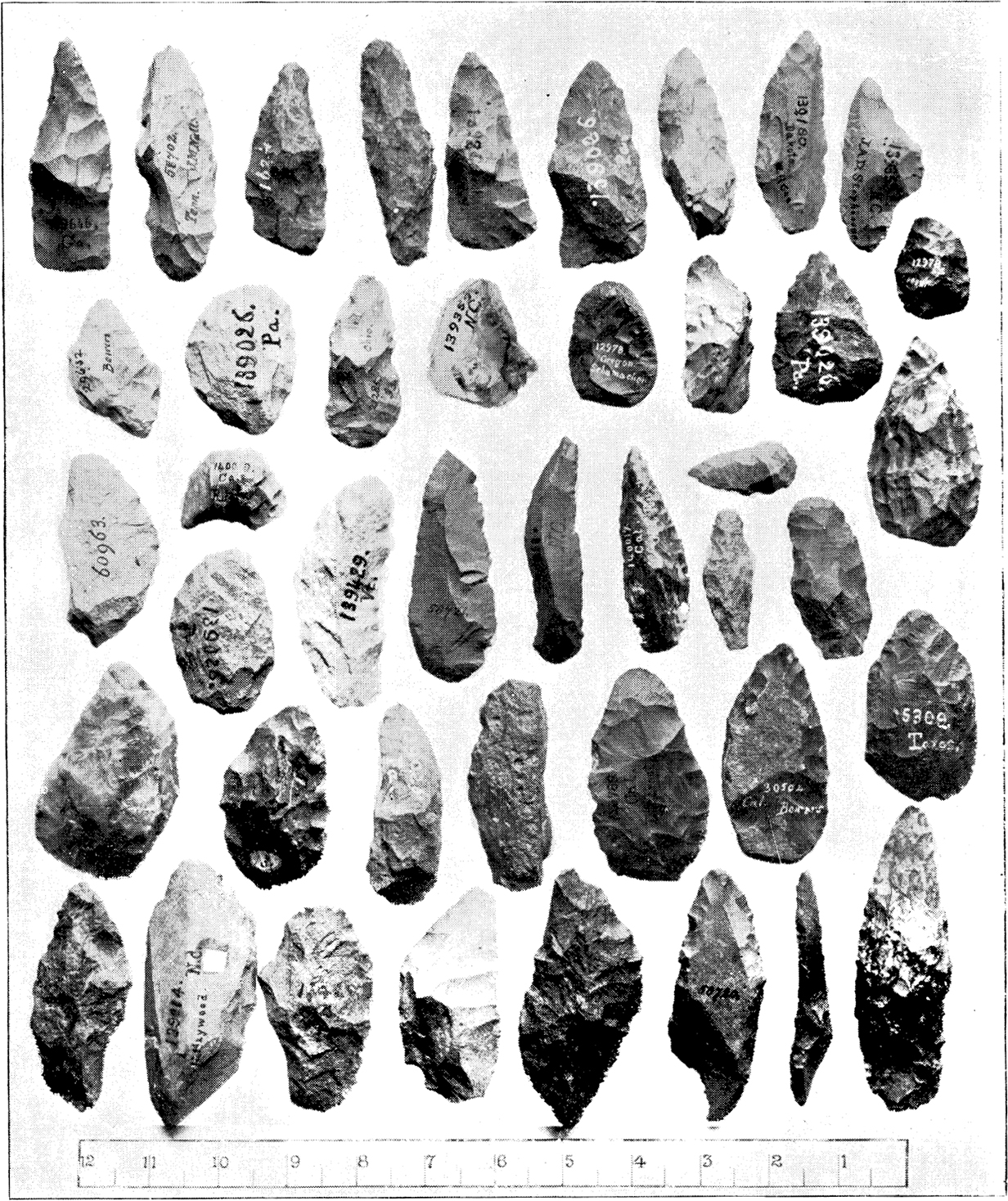

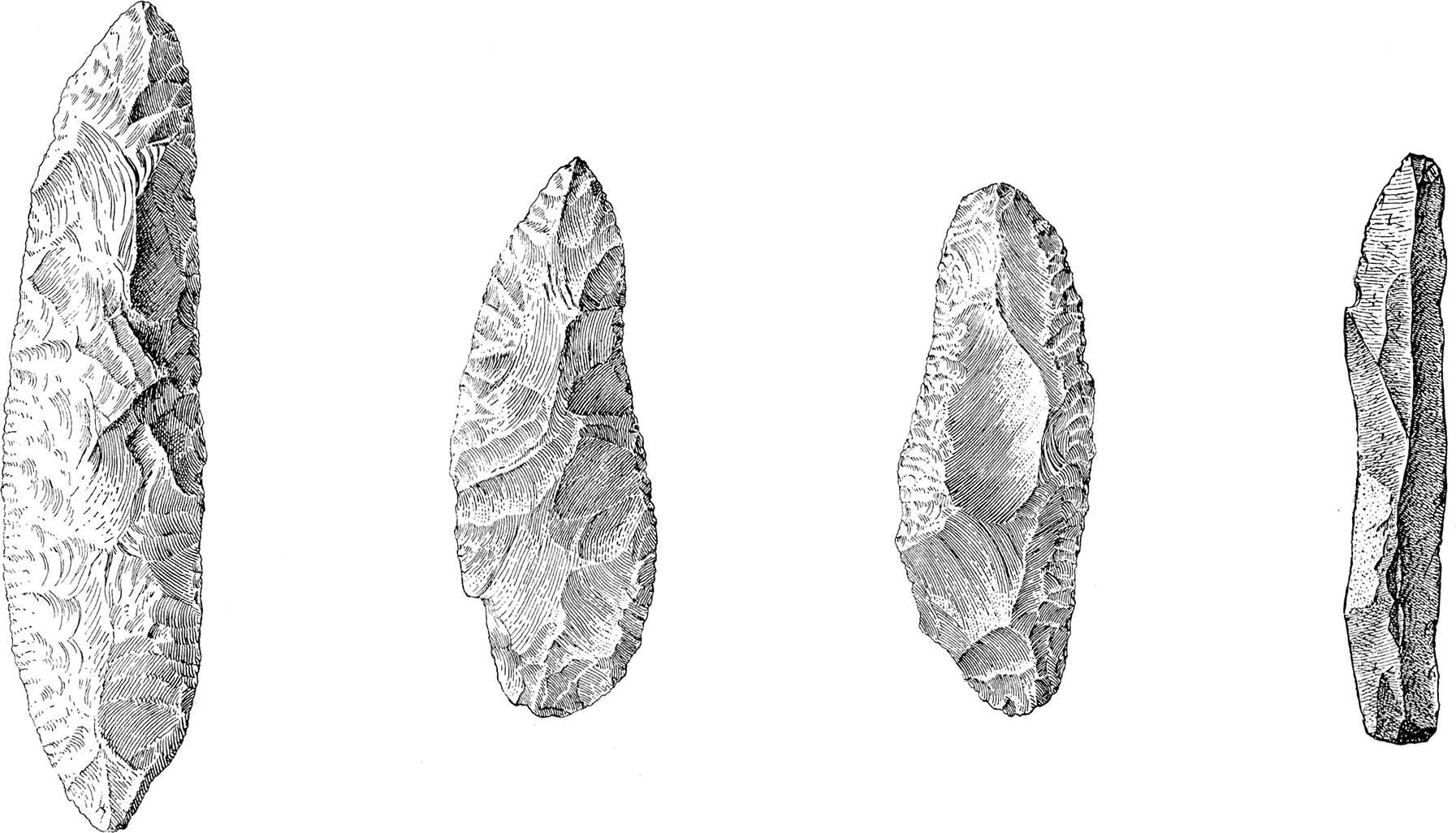

Reference to the classification of these implements will show many varieties, such as leaf-shaped, triangular, stemmed, notched, shouldered, and barbed, yet all these are variations only in details, the general form, the material, and the processes of manufacture being the same. The principal differences between the various kinds, those most affecting their use and purpose, are in size and weight. It seems strange that implements of such similarity in all functional characteristics should differ so much in size and weight, and it is unreasonable to believe that implements of such extremes—one very light and small, the other large and heavy—could have been employed in the same manner or have served the same purpose. It would indeed be strange if implements 15 or more inches long, as the Arvedsen specimen (Plate 65), or those in Plates 61 and 64 in this paper and Plate 27 in “Prehistoric Art,” over 12 inches in length, should have been employed in the same manner and for the same purpose as the small obsidian or jasper “jewel points” from California and Oregon. Yet these are of the same material, have the same style and mode of manufacture, their principal, if not their only, difference being in size and weight.

These implements, with their extreme variations, are not confined to any particular locality or country. The large, finely wrought, leafshaped blades have been found in Mexico as well as in central France, and the small “jewel points” are found in California and Oregon as well as in Italy, with a sprinkling of each scattered over western Europe.

FLINT AND OBSIDIAN LEAF-SHAPED BLADES, HANDLED AS KNIVES.

Hupa Valley, California.

U. S. National Museum.

LEAF-SHAPED FLINT BLADES, IN WOODEN HANDLES, FASTENED WITH BITUMEN.

Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz islands, California.

Wheeler’s Survey, etc., VII, p. 59, pl. IV.

LEAF-SHAPED BLADES OF FLINT AND CHALCEDONY, SHOWING BITUMEN HANDLE FASTENING.

California.

Wheeler’s Survey, etc., VII, pl. I.

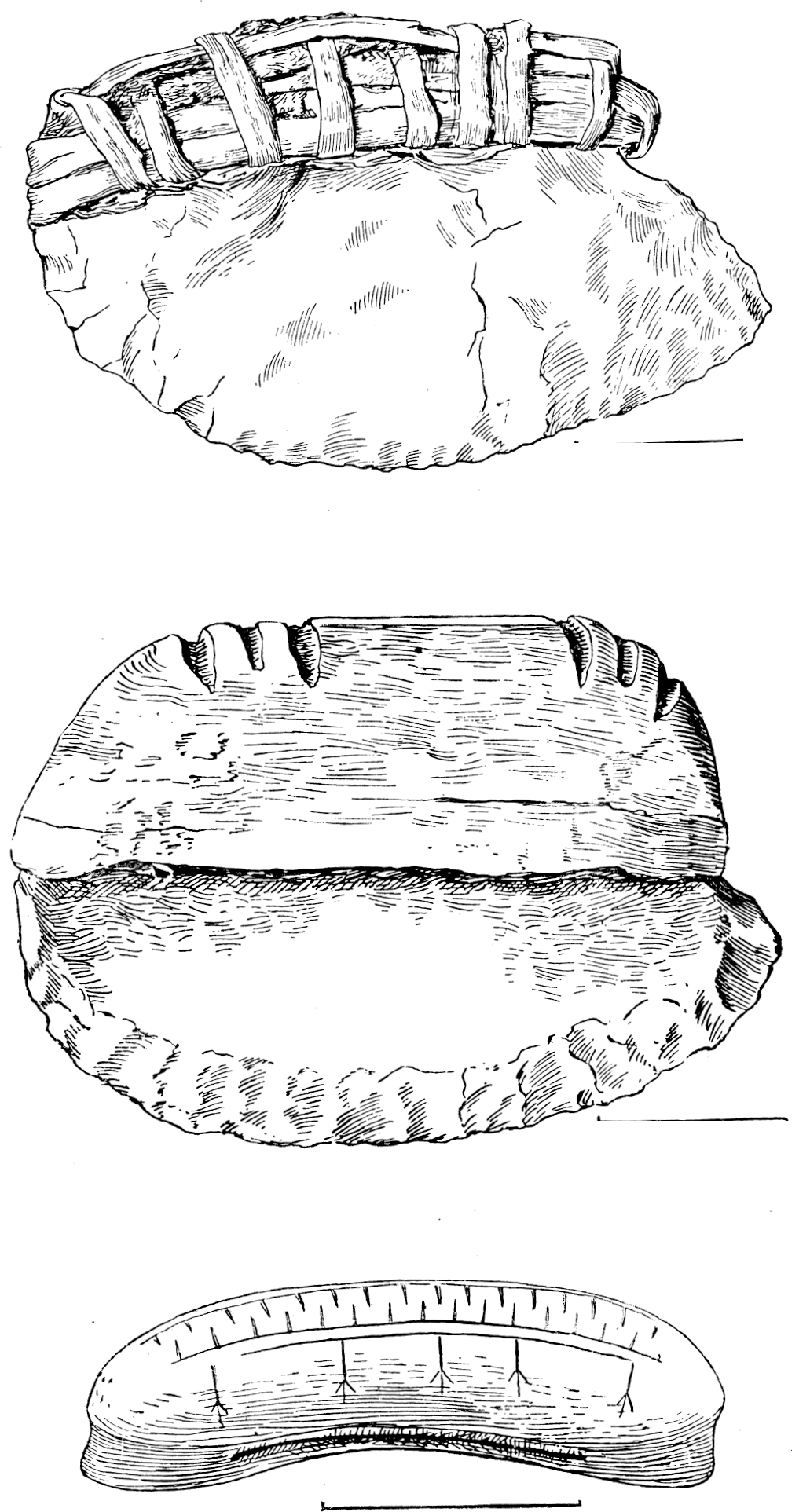

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 44.

Fig. 1. WOMAN’S KNIFE (Ulu). Blade of hornstone, leaf-shaped, with a projection from one margin. The handle is of the most primitive character, being formed of osier, wrapped backward and forward longitudinally, and held firmly in place by cross twining and weaving of the same materiál. The interstices are tilled with fish scales. Length,  inches.

inches.

(Cat. No. 63765. U.S.N.M. Eskimo of Hotham Inlet, Alaska. Collected by Lieut. G. M. Stoney, U. S. N.)

Fig. 2. WOMAN’S KNIFE (Ulu). Blade of chert or flint material, inserted in a handle of wood. On the upper margin of the latter at either corner are three cross gashes or grooves.

(Cat. No. 63766, U.S.N.M. Eskimo of Hotham Inlet, Alaska. Collected by Lieut. G.M. Stoney, U. S.N.)

Fig. 3. WOMAN’S KNIFE (Ulu). Handle of walrus ivory. Ornament, groove, and herringbone on top; lines and alternating tooth-shaped cuts on the side, with five scratches resembling inverted trees. Pocket groove for blade, abruptly wedge-shaped, like the kernel of a Brazil nut. Length,  inches.

inches.

(Cat. No. 44598, U.S.N.M. Eskimo of Cape Nome, Alaska, 1880. Collected by E. W. Nelson.)

ULU OR WOMAN’S KNIFE.

Hotham Inlet and Cape Nome.

Mason, Report U. S. National Museum, 1890, pl. LXI.

COMMON ARROWPOINTS, HANDLED BY THE AUTHOR TO SHOW THEIR POSSIBLE USE AS KNIVES.

U. S. National Museum.

HUMPBACKED KNIVES.

Side and edge views.

District of Columbia, United States, and Somaliland, Africa.

Cat. Nos. 195900, 195398, U.S.N.M.

HUMPBACKED KNIVES.

Side and edge views.

United States.

Cat. Nos. 171487, 1073, U.S.N.M.

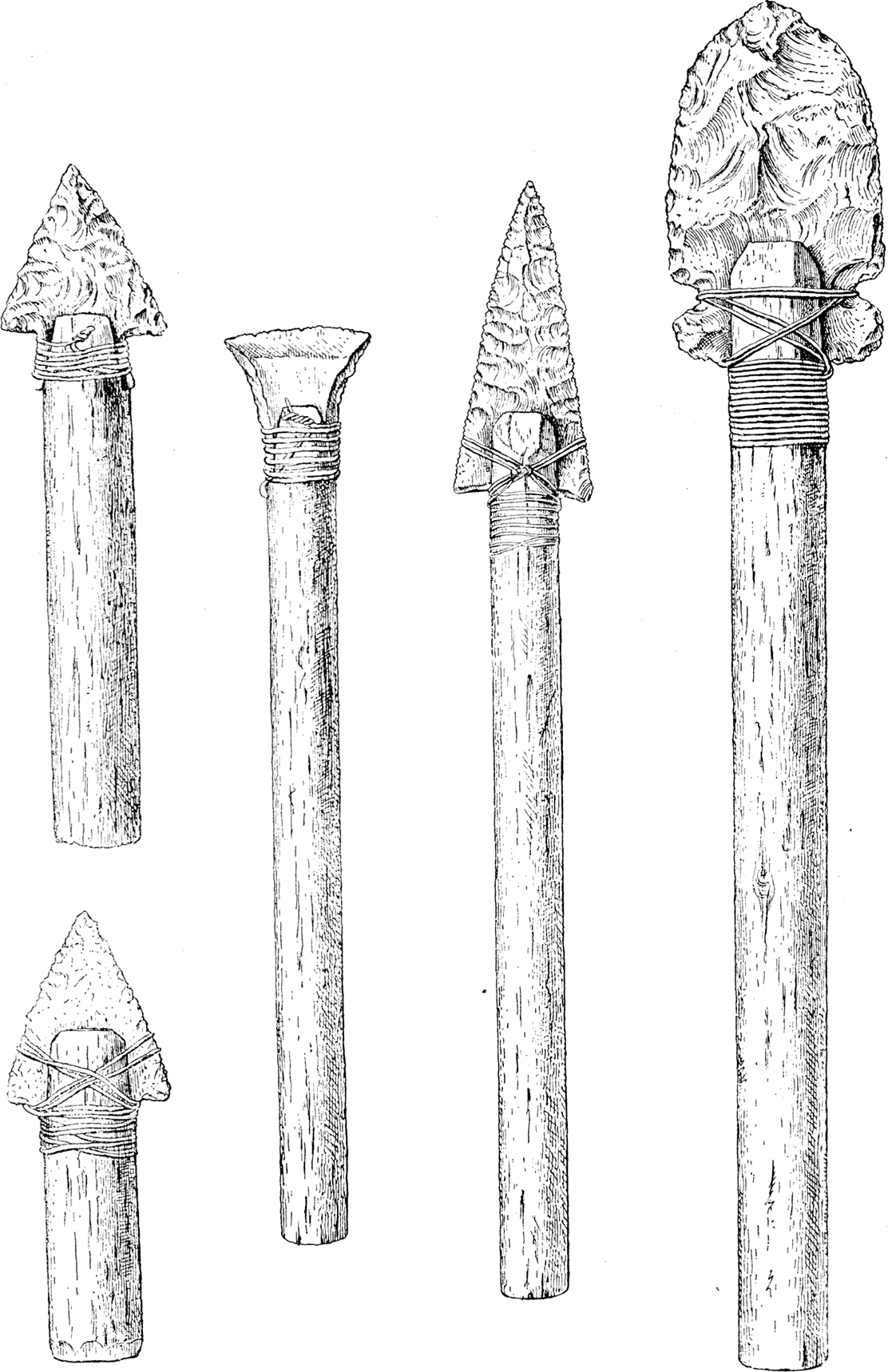

The handle or shaft to which these implements were fastened and with which they were used may assist us in their classification. Imagine a hickory sapling 10 or 12 feet long, which can best be understood by the average American boy when described as a “hoop-pole,” cut, smoothed, seasoned, toughened, or hardened by fire,  inches in diameter at the butt and tapering to a half or three-quarters of an inch at the top, into which one of the small jewel points had been inserted. This implement, held in the hands and used for thrusting, would undoubtedly be called a spear or lance. If the length of the handle was reduced to 4 or 6 feet, it would be a javelin suitable for throwing; with a light reed or cane shaft 2 or 3 feet in length it would be an arrow; and with a handle, however large, if but 3 or 4 inches in length, the implement would become a knife (Plates 41–43). The same classification applies to a larger implement attached to a larger or longer shaft equally well as to the smaller implement with the shorter shaft.

inches in diameter at the butt and tapering to a half or three-quarters of an inch at the top, into which one of the small jewel points had been inserted. This implement, held in the hands and used for thrusting, would undoubtedly be called a spear or lance. If the length of the handle was reduced to 4 or 6 feet, it would be a javelin suitable for throwing; with a light reed or cane shaft 2 or 3 feet in length it would be an arrow; and with a handle, however large, if but 3 or 4 inches in length, the implement would become a knife (Plates 41–43). The same classification applies to a larger implement attached to a larger or longer shaft equally well as to the smaller implement with the shorter shaft.

The foregoing in its application to prehistoric implements is, to a certain extent, theoretical, for their shafts or handles were of wood and by lapse of time have decayed and are lost. We know this as a matter of fact. Among the hundreds of collectors throughout the United States, where tens of thousands of ancient arrowpoints and spearheads have been collected, we have no record of any of them having been found with handle or shaft attached. This is not strange nor is it peculiar to these implements. The polished stone hatchets doubtless had wooden handles, yet of all of the thousands found, there have been less than a dozen reported in the United States with their wooden handles.1 Like the arrowpoint or spearhead, it is usual to find them without any trace of a handle. Objects of wood used in prehistoric times have rarely been found, and the instances thereof are usually confined to those either protected by water2 or those in the sandy desert, where there was no moisture to cause decay.3

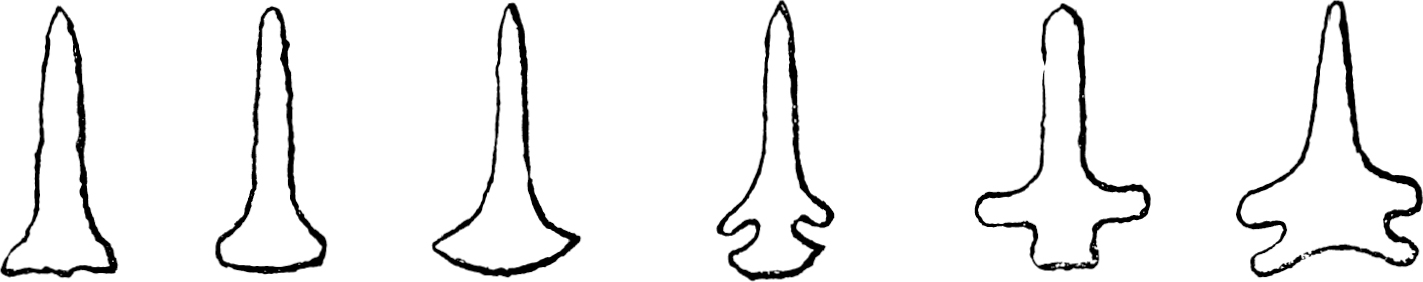

There are some of these implements with their handles which, being found under these favorable conditions, or belonging to modern savages, have been preserved for inspection. Col. P. H. Ray, in his investigations and collections among the Hupa Indians,4 reported a number of leaf-shaped implements, which, if found alone, would have passed for spearheads, as have thousands of others of similar form collected throughout all that portion of the world occupied by prehistoric man. The implements found by Colonel Ray are now in the U. S. National Museum under Professor Mason’s charge (Plate 41). The first series consists of eight specimens. The material is obsidian or chalcedony varying from dark-brown to a dull blue, with veins of blue throughout the brown. The blades vary from 4 to  inches in length, from

inches in length, from  to

to  inches in width, and are from

inches in width, and are from  to

to  inch thick. Handles of pine, from

inch thick. Handles of pine, from  to

to  inches, were attached to all of them. Five of these were glued or gummed, three were lashed. Another of these blades, similar in all respects to the former, was obtained by Colonel Ray, but the wooden handle was replaced by a wrapping of otter skin. The blade is

inches, were attached to all of them. Five of these were glued or gummed, three were lashed. Another of these blades, similar in all respects to the former, was obtained by Colonel Ray, but the wooden handle was replaced by a wrapping of otter skin. The blade is  by

by  by

by  inches. Specimens of the foregoing are set forth in Plate 41, a reference to which will make the description clear. The smaller specimen in this plate represents a series of knives obtained by Maj. J. W. Powell from the Pai Utes. The latter is described and figured by Dr. Charles Rau,1 who says:

inches. Specimens of the foregoing are set forth in Plate 41, a reference to which will make the description clear. The smaller specimen in this plate represents a series of knives obtained by Maj. J. W. Powell from the Pai Utes. The latter is described and figured by Dr. Charles Rau,1 who says:

Collectors are ready to class chipped-stone articles of certain forms occurring throughout the United States as arrow and lance heads, without thinking that many of these specimens may have been quite differently employed by the aborigines. Thus the Pai Utes of Southern Utah use to this day chipped-flint blades, identical in shape with those that are usually called arrow and spear points, as knives, fastening them in short wooden handles by means of a black substance. Quite a number of these hafted flint knives (fig. 1) have been deposited in the collection of the National Museum by Maj. J. W. Powell, who obtained them during his sojourn among the Pai Utes. The writer was informed by Major Powell that these people use their stone knives with great effect, especially in cutting leather. On the other hand, the stone-tipped arrows still made by various Indian tribes are mostly provided with small, slender points, generally less than an inch in length, and seldom exceeding an inch and a half, as exemplified by many specimens of modern arrows in the Smithsonian collection. If these facts be deemed conclusive, it would follow that the real Indian arrowhead was comparatively small, and that the larger specimens classed as arrowheads, and not a few of the so-called spear points, were originally set in handles and were used as knives and daggers. In many cases it is impossible to determine the real character of small leaf shaped or triangular objects of chipped flint, which may have served as arrowheads or either as scrapers or cutting tools, in which the convex or straight base formed the working edge. Certain chipped spearhead-shaped specimens with a sharp, straight, or slightly convex base may have been cutting implements or chisels. Arrowheads of a slender elongated form pass over almost imperceptibly into perforators, insomuch that it is often impossible to make a distinction between them.

Another series of similar implements (Plate 42) with handle attached are in the U. S. National Museum. They are from southern California, and are reported in Wheeler’s Geographical Survey.2 These specimens were collected by Mr. Shumacher from Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz islands. The material, while differing much, was uniformly of hard stone, such as flint, chalcedony, or jasper. The blades are inserted in redwood handles, fastened with gum or bitumen, and bear the evidence of long exposure. The dryness of the country whence they came was probably the cause of their preservation.

These wooden-handled knives were not confined to the coast nor, indeed, to California, but were found far in the interior. The Hazzard collection from the cliff ruins of Arizona and New Mexico, now in the Archæological Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, which made such a memorable display at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, contains a series of similar knives of flint inserted in wooden handles from 4 to 6 inches in length, of the same style and kind as the California specimens in Plate 42.

Forming part of the same series are eleven other specimens without handles, but with the traces of bitumen on the base showing where a handle had been attached. It should not be forgotten in considering these implements that they come from a country which abounds in the ordinary arrowpoints and spearheads of all kinds and sizes, some of which show extremely fine chipping.

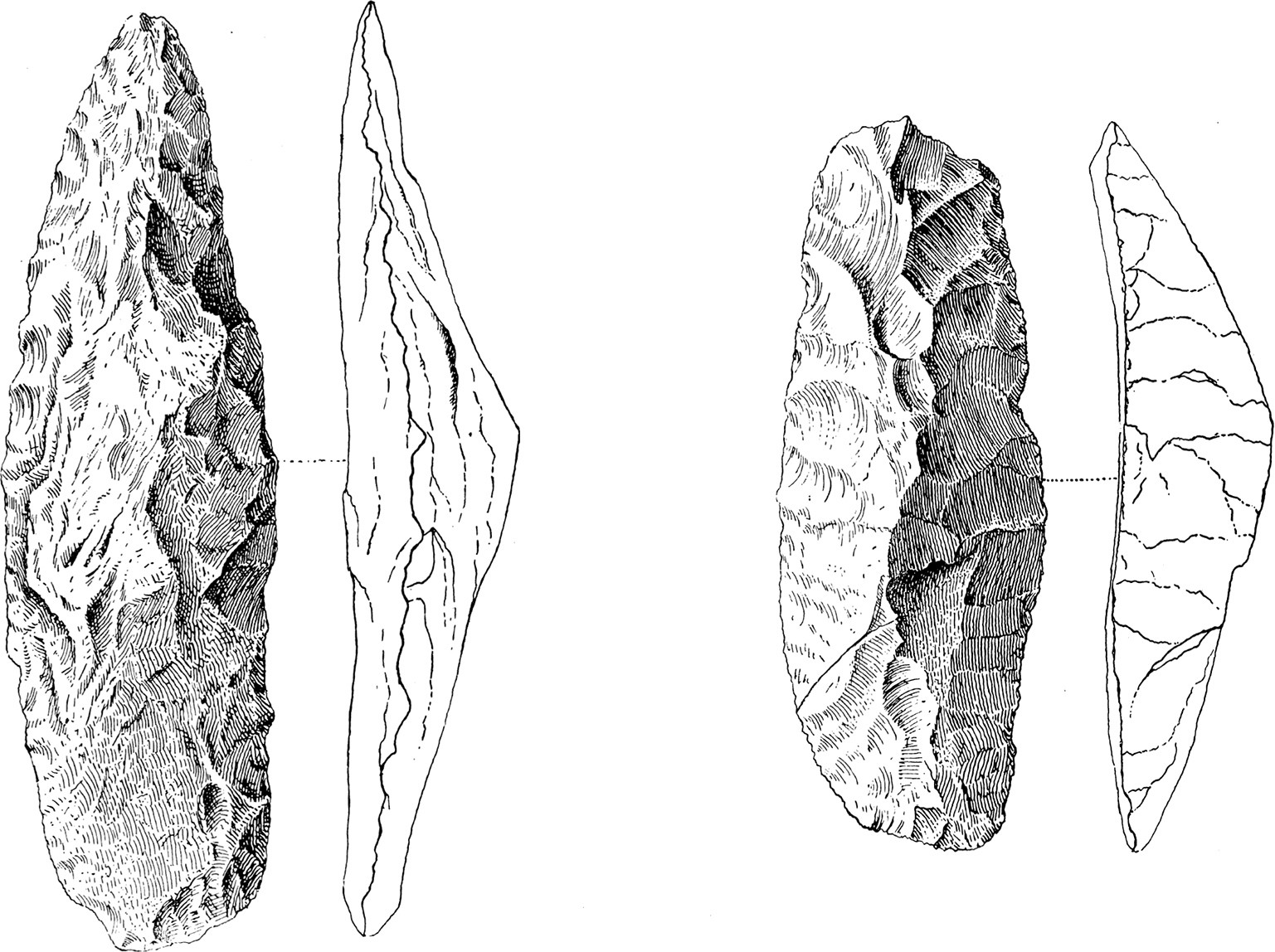

There is still another series1 (Plate 43) quite different in form and make, but to which the same remark applies. Some of them represent the highest order of flint chipping. They form Class C of the division of leaf-shaped implements of the author’s classification. They are long, shin, and narrow, with a well-wrought base which may be square, convex, or concave, while the point is sharp and symmetrical. The peculiarity which determined their classification was the parallelism of their edges throughout their length. An inspection of the specimens renders it evident that they were never intended as arrowpoints or spearheads. Their extreme thinness, together with the breakable character of the flint of which they are made, would cause them to break in any shock that might be given by throwing, lancing, or shooting. Those of the series with convex bases are covered with asphaltum or bitumen for 1 or  inches of the base. This is evidence of their insertion in a handle, which, in view of the circumstances, and their association with the former specimens, we can only conclude was short, and that the implement was intended to be held in the hand and used as a knife or dagger.

inches of the base. This is evidence of their insertion in a handle, which, in view of the circumstances, and their association with the former specimens, we can only conclude was short, and that the implement was intended to be held in the hand and used as a knife or dagger.

Flint or chert points similar in every way to arrowpoints, and inserted in short antler handles, were found by Prof. F. W. Putnam and Dr. C. L. Metz, in their excavations of the Mariott mound in the Little Miami Valley, Ohio.2 Ten or a dozen of these knife handles were found, in one of which was inserted a bone instead of a stone blade.

In the Swiss lake dwellings small polished stone hatchets or chisels are frequently found inserted in short antler handles. Many of these antlers were tenoned for insertion in a heavy wooden handle, evidently for use in chopping, as an ax,3 but many of the antler handles were without tenons, and were evidently intended to be held in the hand and used as knives or chisels and not as axes.4

Flint or chert arrowpoints, inserted in short wooden handles for use as knives, are found in the ancient tombs of Peru. Sharpened and barbed points of bone and of ivory, inserted in short handles of wood, bone, and ivory, the lower end pointed for insertion in a lance shaft for use as harpoons, are in common use among the modern Eskimos. This short handle can be detached, thus making, if need be, a knife of the implement.

An illustration of large blades, more or less leaf-shaped, and which, if alone, would be taken for spearheads, is shown in fig. 193, where such an implement of nephrite, beautifully wrought and finely polished, is inserted in a short handle, evidently for use as a knife. The illustrations, shown in Plate 44, of Eskimo specimens from Hotham Inlet, Alaska, collected by Lieut. Commander G. M. Stoney, U. S. N., are still more pertinent. Figs. 1 and 2 have blades of chert or hornstone of the usual leaf shape. Fig. 2 is handled for use as a knife by being inserted edgewise in a handle of wood. Fig. 1 is interesting, for its leaf-shaped characteristics are more easily identified, while its handle, instead of being of wood or fastened with bitumen or asphaltum, as have been nearly all others, is made of osier wrapped back and forth over a part of the upper edge of the blade, catching upon the irregularities of the flint edge and drawn tight so as to be held firmly in place. This was used as a fish knife, its interstices being yet filled with fish scales. Dr. Mason,1 describing this instrument, says:

ESKIMO KNIFE WITH NEPHRITE BLADE, IVORY HANDLE, AND WOODEN SHEATH.

Norton Bay, Alaska.

Blade,  inches.

inches.

E. W. Nelson. Cat. No. 176072, U.S.N.M.

There are thousands of pieces of shale, slate, quartzite, and other stones in the National Museum, which correspond exactly with the blades of the Eskimo woman’s knife. These have been gathered from village sites, shell heaps, the surface of the soil, from graves, mounds, and Indian camps in countless numbers. * * * In the matter of attaching the blade to the handle or grip the Eskimo’s mother-wit has not deserted her. Many of the blades are tightly fitted into a socket or groove of the handle. Boas, who lived among the Cumberland Gulf Eskimos, tells us that glue is made of a mixture of seal’s blood, a kind of clay, and dog’s hair. (Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, VI, p. 526.)

Fig. 3 in this plate represents a handle for a similar blade, which is, however, missing. It is made of walrus ivory, the groove in which the blade has been inserted being plainly seen.

Fig. 194 represents one of the thin leaf-shaped blades from Wyoming. It is of agatized wood, is very thin, and has been finely chipped. One edge is more convex than the other and is much the sharper. Compared with the Ulu knife (Plate 44, fig. 1), no reason appears why a similar handle would not make it the same knife.

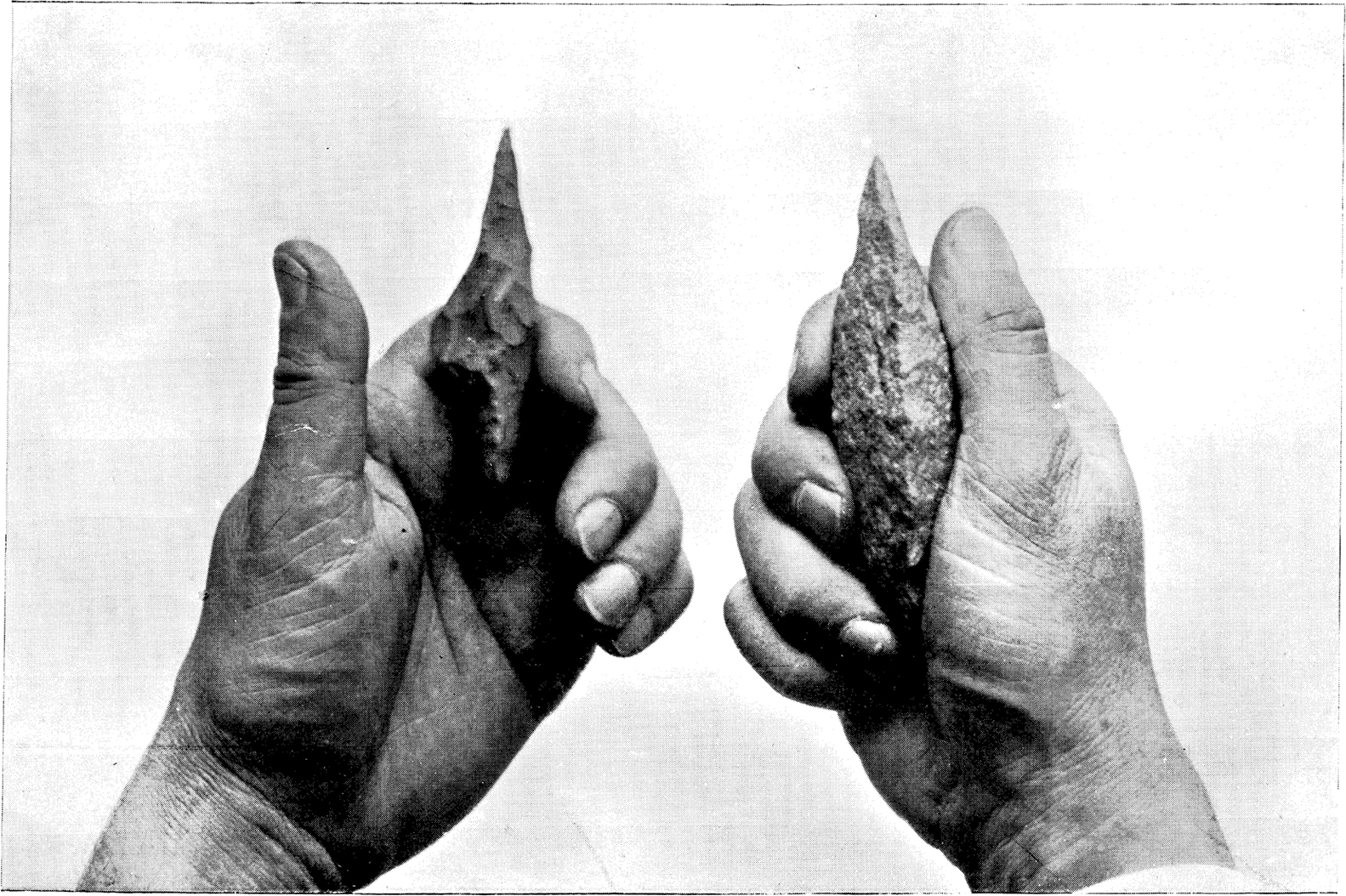

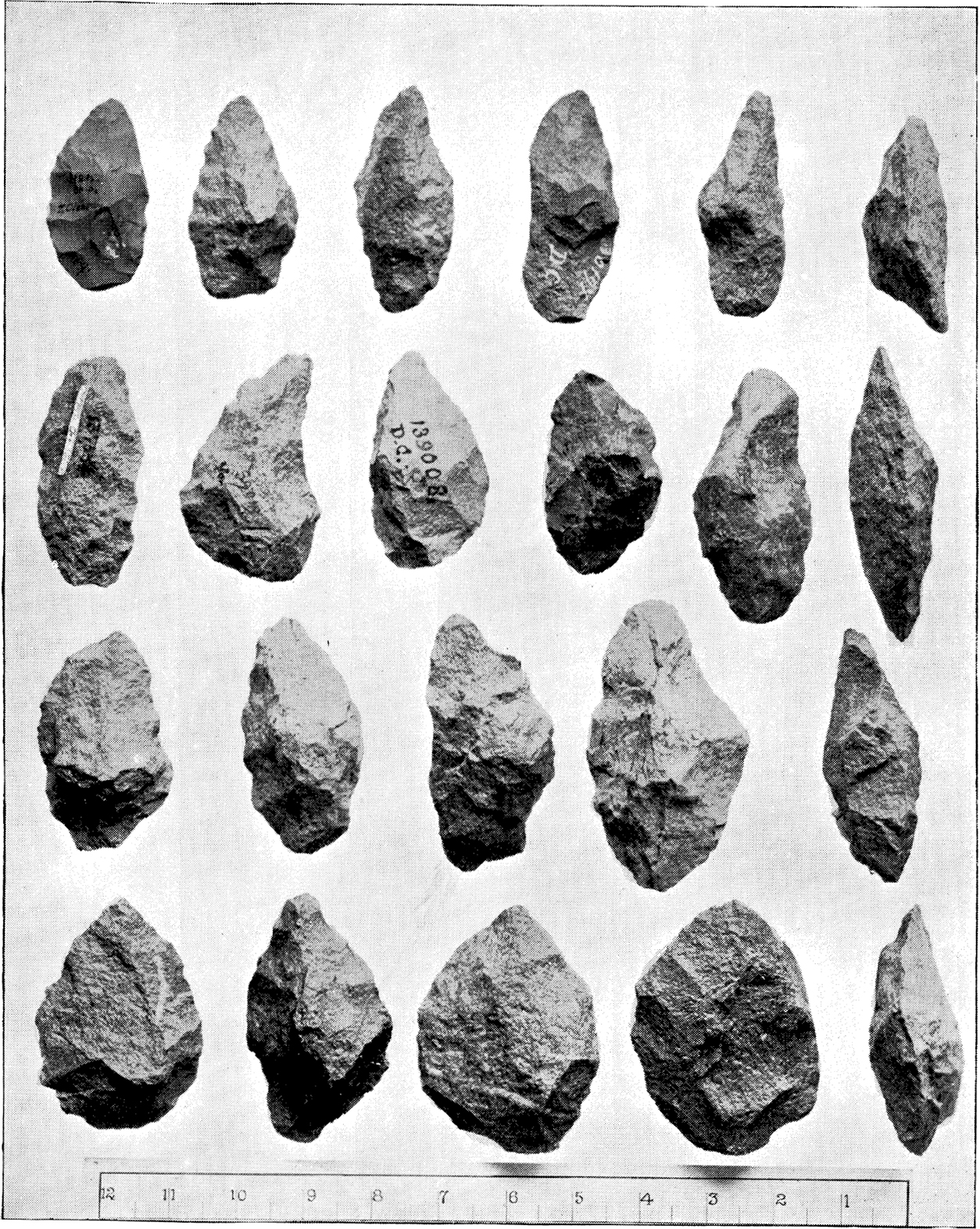

Plate 45 shows a series of common arrow or spear heads which have been inserted and wired in handles by the author. The handles vary from 6 inches in length down. They are intended to illustrate the proposition which has been herein presented—that with long handles they are arrows, with longer handles they become spears, while with short handles they become knives, and the distinction is only recognizable by the handle.

No attempt has been made in the foregoing arguments to show a difference, except in the handle, of the implement used as a spear or arrow and its use as a knife. The announcement is made as a working hypothesis that the average stone arrowpoint or spearhead collected throughout the country as an Indian implement or weapon may have been either spear, javelin, arrow, or knife, dependent upon the kind of handle employed.

LEAF-SHAPED BLADE OF AGATIZED WOOD.

Wyoming.

Natural size.

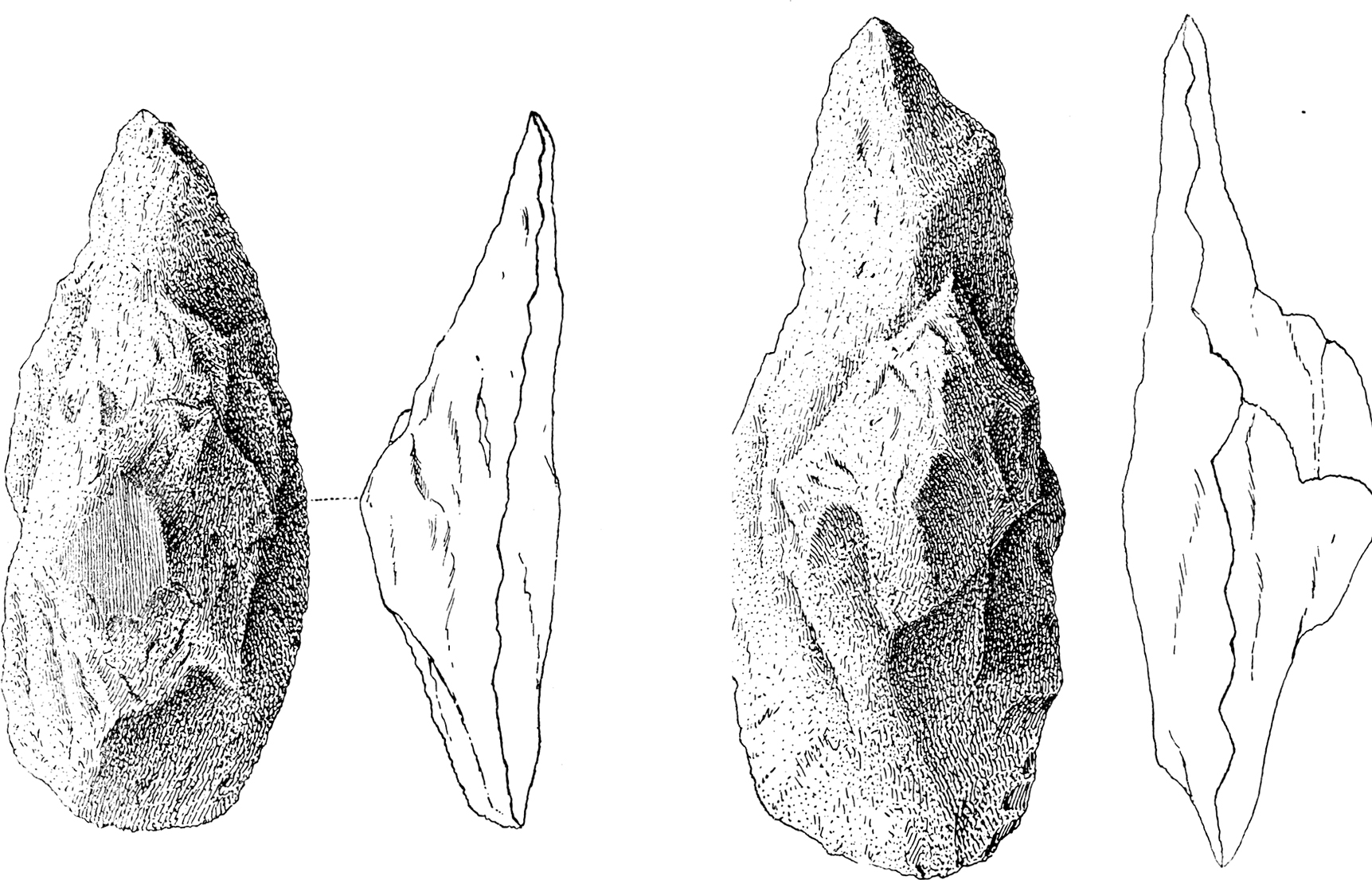

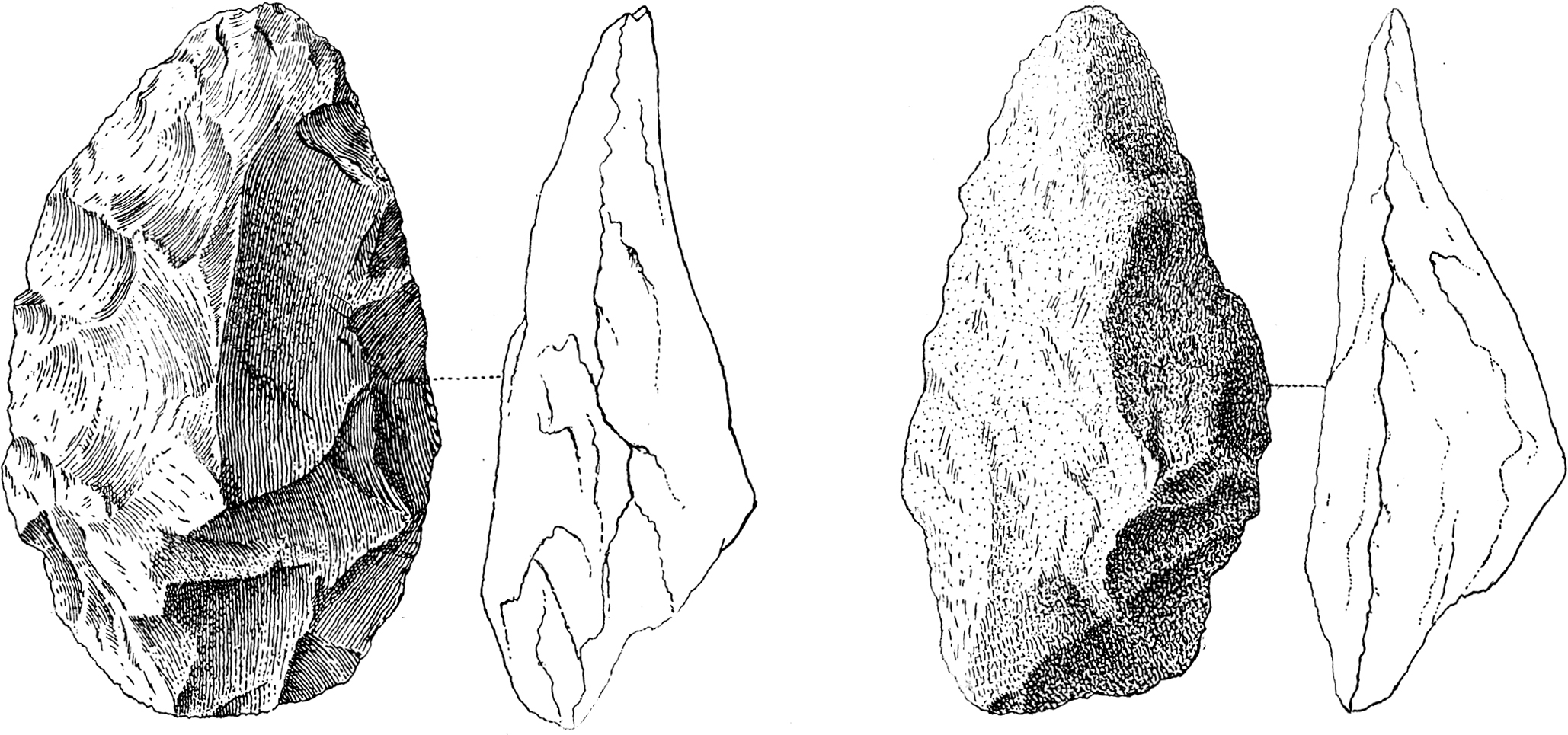

There are other implements of the same material and manufacture, but with variations of form, which are not, and were never intended to be, arrow or spear heads. These, when viewed in profile from either the side or edge, show that they could not have served as piercing implements or weapons. Their edges are on the sides and not at the points, and they could only have been used for cutting and not for piercing, and were, therefore, knives. Plates 46 and 47 present specimens of this class. They are here presented in side and edge views to show this peculiarity, for viewed from the side only they appear as ordinary leaf-shaped implements worked all round to an edge. The points are not sharp, and it is doubtful if they could ever pierce any resisting substance, projected with whatever force. The impossibility of their use in this manner becomes more apparent when the edge view is considered. This shows the want of symmetry in the implement and completely changes the idea presented by the side view. There is on the top, if one may so call it, a decided hump, and, for want of a better name, these implements have been called “humpbacked.” One of them is the chalcedonic flint, while the other three are quartzite. They are rude and have all been made by chipping. Each implement has only one rounded edge sharp enough for use, and could be used when held in the hand after the manner of the fish knife (Plate 44, fig. 1).

The manner of holding these humpbacked implements for use is shown in Plate 48, where two of them are held in the hand so as to present the cutting edge. This (in Plate 48) leads to another hypothesis, that is, that these implements were used ambidextrously, and furnish evidence of right- and left-handedness on the part of prehistoric man. It is certain that the shape of an occasional implement fits the left hand better than it does the right. Certain specimens show this more or less plainly. Their humps are not in the center but off to one side, sometimes to the right, other times to the left, while the experiment of grasping them in the hand (as shown in Plate 48) demonstrates that they are more easily manipulated and more effective when used right and left handed respectively, than when used indifferently.

It has been suggested that these implements were only accidents or failures made by the aboriginal workmen when endeavoring to make the usual leaf shaped implement, but such is not regarded as a correct deduction.

It would be foolish to assert that there were no accidents or failures in the prehistoric quarry or workshop. The author has shown in Plate 63, the chips and débris which he personally took from Flint Ridge, Ohio. Anyone having the slightest familiarity with such work has seen and will recognize thousands of such specimens. At Piney Branch, District of Columbia, they were to be numbered by the hundreds of thousands and to be measured by the ton. But it is equally daring to assert that everything found was an accident or failure, and that implements with the specialization of these now under discussion were but waste, the débris and rejects of the workshops and the accidents or failures of the workmen. Their number is too large, their dissemination too general, their distribution too extensive, and their specialization and adaptability too evident to permit such a conclusion to pass unchallenged. The evident existence of an intentional cutting edge around one side of the oval can not be ignored, while their fitness to either hand, as shown in Plate 48, and their adaptability for use as knives or for cutting purposes, are evidences against the reject or waste theory that can not be set aside by mere declarations, however persistently or pertinaciously made. No reason is, or, I take it, can be given why the workman, having gotten his implement into its present humpbacked condition, should not have continued his work by striking off the hump if he desired it to be stricken off, either with a direct stroke of the hammer or by the mediation of a punch, thus reducing its thickness and making it the usual leaf-shaped implement. The conclusion seems inevitable that his failure to do this is evidence of the want of his desire to do so, and that he left it thus—specimens being found throughout the country—is evidence that he desired to make a different implement from the leaf-shaped. This different implement was for cutting and not for piercing, was to be held in the hand and not used as a projectile, and finally is a knife and not an arrowpoint or spearhead.

MANNER OF HOLDING “HUMPBACKS” FOR USE AS KNIVES.

“HUMPBACKS” CHIPPED SMOOTH, SHOWING INTENTIONAL KNIVES.

United States.

Cat. Nos. 138985, 171487, U.S.N.M.

“HUMPBACKS” OF QUARTZITE WITH ONE CUTTING EDGE, USED AS KNIVES.

United States.

Cat. No. 1390081, U.S.N.M.

RUDE KNIVES OF FLINT AND HARD STONE, CHIPPED TO A CUTTING EDGE ON ONE SIDE OF THE OVAL.

United States.

RUDE KNIVES OF FLINT, JASPER, ETC.

Some in flakes, chipped to a cutting edge on side of oval; some have a well-developed hump. United States.

KNIVES WITH STEMS, SHOULDERS, AND BARBS, RESEMBLING ARROWPOINTS AND SPEARHEADS, BUT WITH ROUNDED POINTS UNSUITABLE FOR PIERCING.

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 53.

KNIVES WITH ROUND POINTS.

Fig. 1. WHITE FLINT.

(Cat. No. 19022, U.S.N.M. Indiana.)

Fig. 2. FLINT.

(Cat. No. 10004. U.S.N.M. Camden County, Georgia. Chas. R. Floyd.)

Fig. 3. QUARTZITE.

(Cat. No. 18050, U.S.N.M. Edgartown, Massachusetts. J. W. Clark.)

Fig. 4. PYROMACHIC FLINT.

(Cat. No. 34341, U.S.N.M. Frankford, Ohio. A. R. Crittenden.)

Fig. 5. BROWN CHERT.

(Cat. No. 3210, U.S.N.M. Mound near Nashville, Tennessee. Maj. J. W. Powell.)

Detailed examination confirms the view that these implements were intentionally manufactured and were not mere accidents or failures. Plate 49 represents two of these humpbacked implements, side and edge views. From these it is evident that the making of the hump is intentional. Not only is the hump recognized and permitted, but it has been adopted and treated accordingly. It has not here been left rude or unseemly, but has been carefully smoothed by chipping over its entire surface, the hump being as well preserved as in the rudest specimens. The specimens in this plate are both of flint, one from Wisconsin, the other from Georgia; both are flat on the bottom, rounded on top, and brought by chipping to a sharp cutting edge and without point. If these two specimens were the only ones thus treated, their evidence would be insufficient, but the Museum possesses numerous examples of the same kind which tend to prove the same fact. Plates 50 to 52 present some of these specimens, and a comparison will show the similarity. Their number shows that those in Plate 49 are not isolated specimens, while their number and extensive distribution throughout the country demonstrates their common use as one of the tools or implements belonging to the prehistoric culture of the country. These plates are intended also as evidence of the major proposition—that is, that many of the flint and other objects heretofore classed as arrowpoints or spearheads were really knives. These implements have no sharp points and could never have served for any piercing or thrusting purpose, but, on the other hand, have been made sharp on one, rarely on both edges, and could have been used only for cutting. The cutting edge is usually convex; the outer edge or back is thick and heavy. It has not been worked, and must be held in the hand to be used saw or knife fashion. It is submitted that they show themselves to have been cutting implements used after the manner of knives, and not to have been either arrowpoints or spearheads.

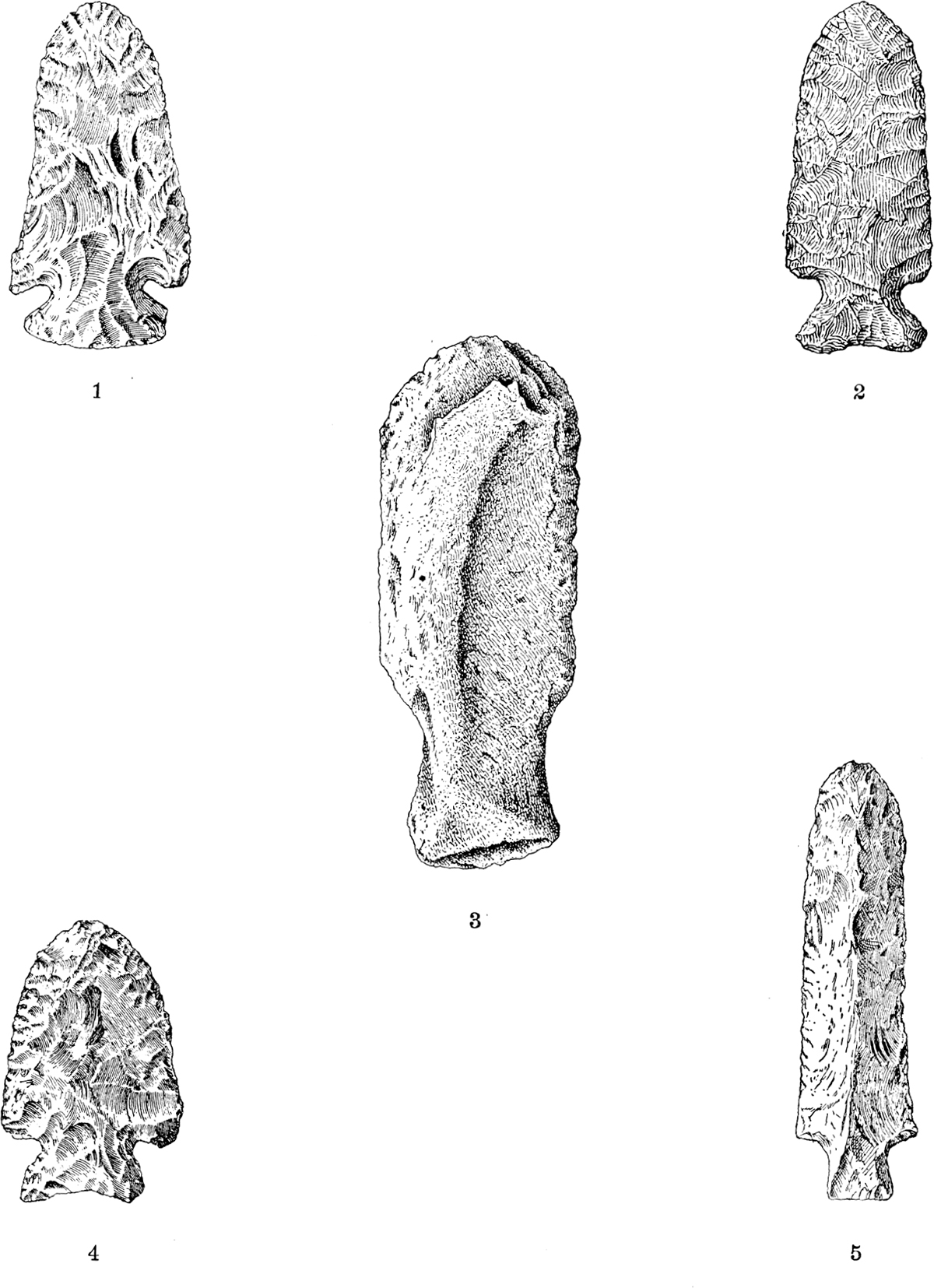

The major proposition of this chapter is that many aboriginal implements having the appearance of arrowpoints or spearheads, and heretofore generally so classed, were not such, but were in reality knives intended for cutting or sawing purposes. The specimens on Plate 53 are evidence in favor of this. The lower or butt end of these specimens has a stem, with base, notches, shoulders, barbs, sharp edges, etc., and in all these regards they resemble the ordinary arrowpoint or spearhead. The point, however, while symmetrically formed and thoroughly worked, is not sharp, but is a well-rounded oval, impossible for thrusting or piercing.

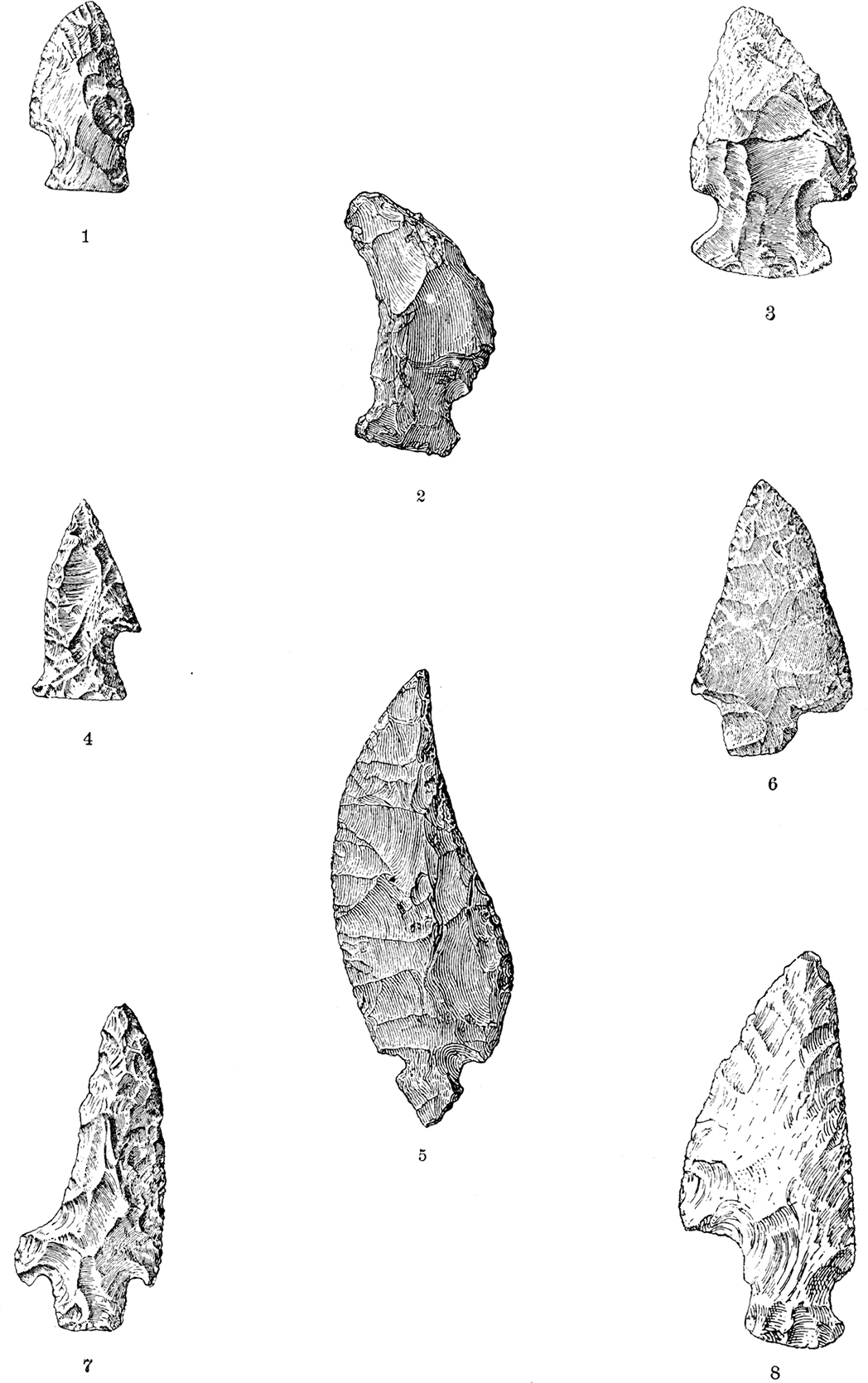

On page 941 of the classification of arrowpoints and spearheads, among peculiar forms, a certain series is shown as Class H, asymmetric. These are there mentioned as being possible knives, and were inserted to complete the classification. No opportunity then offered to investigate their true character or to bring out their peculiarities. Plates 54 and 55 and fig. 195 are here introduced in continuation of that investigation. The original of fig. 195 belongs to the collection of Dr. Roland Steiner. There are 122 specimens of this series which are represented by fig. 195 and certain specimens on Plate 55. They resemble arrowpoints and spearheads, having the same stem, base, shoulders, and barbs. So far as relates to the stem end, their resemblance is perfect, and they might belong to any class of stemmed arrowpoints or spearheads. Some are rather thick and rude, but many are thin and finely chipped. Their peculiarity is their asymmetric form. They are lopsided, or onesided. The shoulder or barb is on only one edge. The other has been chipped off in the ruder specimens from one side only, making a concave scraping-edge, possibly for arrow shafts, while the finer ones are chipped from both sides and are not concave; but in both kinds of specimens the shoulder or barb is on one side only, and that has been brought to a smooth, sharp edge. An examination of these specimens, a number of which are shown in Plates 54 and 55, shows clearly their asymmetric character and makes apparent at a glance their knife-like appearance. A short handle attached with sinew, as in the case of ordinary arrowpoints or spear heads (Plate 45), or with gum or bitumen, as in the California specimens (Plates 41–43), will make a knife suitable for all known savage needs.

UNILATERAL KNIFE OF YELLOW FLINT.

Georgia.

Steiner collection. Cat. No. 171159, U.S.N.M.

All differentiation rendering them suitable for knives renders them unsuitable for arrowpoints or spearheads. They are heavier on one side than on the other, which renders them lopsided and would throw them out of the line of flight and destroy their efficacy as projectiles. It is believed that even a slight examination demonstrates the correctness of the conclusion that they were knives, rather than arrowpoints or spearheads.

Concluding the chapter on knives, it is deemed wise to introduce for comparison a series of those which heretofore passed for and have been recognized as knives. The author does not remember any specimens of the asymmetric or unilateral form in Europe, except those from Solutré which do not belong to the Neolithic period. Knives were, however, by no means rare among the prehistoric implements of that country. One of these knives is represented in Plate 56, fig. 1. It is nothing more than a smooth flake struck from a nucleus of flint in such way as to make or leave a natural edge sharp for use. Specimens similar to this in appearance and manufacture, and supposed to have been made and used as knives, are found in great profusion throughout western Europe, almost every excavation in a prehistoric occupation bringing these flakes to light in greater or less number. The same statement can be made in respect to America. Plate 57, figs. 1, 2, are specimens of similar flint flakes from America, supposed to have been used as knives. Flakes of the same general character, but chipped to a sharp edge, are found in both Europe and America and are also supposed to have been used as knives. Whether they have been dulled by use and the edge then restored by chipping is unknown. It is known, however, that the worked flakes, either primarily or secondarily chipped to an edge, have been found in many of these places and that they are generally accredited as knives. The other specimens on Plates 56 and 57 are representatives of these worked flakes.

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 54.

UNILATERAL KNIVES.

Fig. 1. YELLOW FLINT.

(Cat. No. 10824, U.S.N.M. Bahala Creek, Copiah County, Mississippi. T. J. R. Keenan.)

Fig. 2. BROWN CHERT.

(Cat. No. 60597, U.S.N.M. Lincoln County (?), Tennessee. C. S. Grisby.)

Fig. 3. CHERT.

(Cat. No. 34863, U.S.N.M. Falmouth Island, in Susquehanna River, Pennsylvania. J. Orendorf and F. G. Gailbraith.)

Fig. 4. DARK-GRAY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 7672, U.S.N.M. Groveport, Ohio. W. R. Limpert.)

Fig. 5. MOTTLED-GRAY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 23265, U.S.N.M. Mound on Etowah River, Georgia. B. W. Gideon.)

UNILATERAL KNIVES.

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 55.

UNILATERAL KNIVES.

Fig. 1. BROWN JASPER.

(Cat. No. 31583, U.S.N.M. (Locality unknown.) Dr. T. H. Bean.)

Fig. 2. PALE-GRAY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 32753. U.S.N.M. Richmond, Jefferson County, Ohio. Samuel Houston.)

Fig. 3. PINK FLINT.

(Cat. No. 171459, U.S.N.M. Burke County, Georgia. Dr. R. Steiner.)

Fig. 4. GRAY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 62104, U.S.N.M. Mason County, West Virginia. R. W. Mercer.)

Fig 5. FLINT.

(Cat. No. 30179, U.S.N.M. (cast). Illinois. Dr. J. F. Snyder.)

Fig. 6. GRAY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 59221, U.S.N.M. Tennessee. C. L. Stratton.)

Fig. 7. WHITE FLINT.

(Cat. No. 196505, U.S.N.M. Louisiana. Phillips collection.)

Fig. 8. WHITE FLINT.

(Cat. No. 4935, U.S.N.M. Illinois.)

UNILATERAL KNIVES.

FLINT FLAKES CHIPPED ON ONE EDGE ONLY, INTENDED FOR KNIVES.

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 56.

FLINT FLAKES CHIPPED ON ONE EDGE ONLY, INTENDED FOR KNIVES.

Fig. 1. FLINT.

(Cat. No. 27001, U.S.N.M. Cumberland Mountains, Tennessee. Gen. J. T. Wilder.)

Fig. 2. FLINT.

(Cat. No. 60265, U.S.N.M. Tennessee. C. S. Grigsby.)

Fig. 3. FLINT.

(Cat. No. 19234, U.S.N.M. Louisville, Kentucky. Dr. James Knapp.)

Fig. 4. FLINT.

(Cat. No. 100257, U.S.N.M. Spiennes, Belgium. Thomas Wilson.)

FLINT FLAKES CHIPPED ON ONE EDGE INTENDED FOR KNIVES.

EXPLANATION OF PLATE 57.

FLINT FLAKES CHIPPED ON ONE EDGE, INTENDED FOR KNIVES.

Fig. 1. GRAYISH FLINT.

(Cat. No. 29024, U.S.N.M. Milnersville, Guernsey County, Ohio.)

Fig. 2. GRAY JASPERY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 98089, U.S.N.M. Kentucky. W. M. Linney.)

Fig. 3. YELLOW JASPER.

(Cat. No. 7050, U.S.N.M. Union County, Kentucky. S. S. Lyon.)

Fig. 4. PALE-GRAY FLINT.

(Cat. No. 32421, U.S.N.M. Lick Creek, Orange County, Indiana. F. M. Symmes.)

The subject of knives is not exhausted. It has not even been considered except as it involves arrowpoints or spearheads.

The author of the Manuel du Chirurgien d’Armée declared that military surgery had its origin in the treatment of wounds inflicted by arrows and spears, and in proof thereof he quoted from ancient classics1 and cited Chiron and Machaon’s patients, Menelaus and Philoctetes, and Eurypyles treated by Patroclus. He believed the name “medicus” in the Greek anciently signified “sagitta,” an arrow,2 and declared that Hippocrates used a particular forceps, “beluleum,” for extracting arrows, which his successor, Diodes, improved and called “graphiscos.”3 Heras of Cappadocia, in the wars of Augustus, invented the duck-bill forceps. Celsus4 taught the necessity of dilating the wound in order to extract the arrowhead, and Paulus Ægineta5 treated arrow wounds in a peculiarly successful manner.

The author, Baron Percy, who thus showed his knowledge of classic medical literature, supposed he had discovered the origin of surgery and was dealing with the earliest wounds made by man with the machinery of war.

The discovery in the present century, of prehistoric man, and the repeated findings of his graves and cemeteries belonging to the Neolithic and Bronze ages, and the thousands of skeletons therein, many of them with wounds and fractures—these things have completely overturned the ideas of Baron Percy as to the earliest human wounds and the origin of surgery.

In an earlier chapter we have seen how the ages of stone and bronze had practically passed away without any historical mention of their existence. The beginning of history is subsequent to them. Nowhere in the Eastern Hemisphere, nor elsewhere except among modern savages, have stone arrowheads been known in historic times. Arrowpoints may have been used by the million in times of antiquity, but those known to history, noted by historians, were all of iron or bronze; none were of stone. In the army of Xerxes only one tribe, blacks from the interior of Africa, had arrows tipped with stone. All others used iron or bronze. The age of stone arrowpoints or spearheads had passed away before the time of Xerxes. All of which only shows how sadly mistaken was the author of the Manuel du Chirurgien d’Armée in his opinion as to the origin of surgery and the dates of the earliest wounds made by man’s weapons.

It has been thought by many persons, among them a number highly qualified to judge, that there were no burials made during the Paleolithic period in western Europe. Whether this be true or not, it must be admitted that, either because of the rarity of the burials or the immensity of time which has elapsed, or possibly the failure to discover the graves, or for these reasons either singly or collectively, there have been comparatively few of the skeletal débris of Paleolithic man found. And this would satisfactorily account for the few examples of wounds found. The skeletons from the cave at Cro-Magnon show evidence of wounds. The femur of the man has been broken, while the forehead of the woman that lay beside him bears a large gash, made apparently with a flint hatchet.

Broca, who examined these specimens, is of the opinion that the latter bore traces of suppuration and evidences of healing.1

Dr. Hamy reports many of the bones in the cavern at Sordes as having curious wounds, one a gaping wound in the right parietal of a woman who, like that of Cro Magnon, must have survived the injury for some time. Pieces of bone had been removed and there was evidence of healing.2

There has been some question as to whether these caves belonged to the Paleolithic period. It makes but little difference to the present argument, for we will soon see that in the Neolithic period such wounds, made sometimes by hatchets or by blows of other weapons, and sometimes by thrusts received by arrows or spears, were found in considerable number.

Dr. Prunières, of Marvajols (Lozère), France, a surgeon, anatomist, and an early student of prehistoric anthropology, conducted many original excavations into the dolmens, tumuli, and burial places of his neighborhood, and had the good fortune to make a large collection of objects pertaining to prehistoric man in that country. He took special care to search for and preserve all those relating to physical anthropology, especially those showing skeletal peculiarities. The following is a partial list of objects in his collection relating to arrow wounds:

The superior portion of a tibia, with a deep and suppurated wound, in which is still embedded a flint arrowpoint.

Fragment of the iliac bone, in the internal part of which is embedded an arrowpoint in a wound which showed signs of suppuration.

Another fragment of iliac bone, in the external part of which was embedded an arrowpoint of flint in a suppurated wound.

A dorsal vertebra with flint arrowpoint in a wound in the body of the vertebra—no suppuration.

HUMAN VERTEBRA (PREHISTORIC) PIERCED WITH FLINT ARROWPOINT (TRANCHANT TRANSVERSAL).

Cartailhac, La France Prehistorique, p. 254, fig. 124.

Lumbar vertebra with a wound which had been much enlarged by suppuration and an arrowpoint embedded it it.

A vertebra with an arrowpoint buried in the body. (Presented before the Congress at La Rochelle.)

A vertebra with an arrowpoint buried in the wound.

An astragalus with arrowpoint in the wound.

The caverns of Baumes-Chaudes and L’Homme Mort were the most complete charnel houses of Neolithic times, each containing about three hundred skeletons capable of identification. It was out of this wealth of material that Dr. Prunières was able to obtain such numbers of peculiar specimens.

The prehistoric anthropologists of France have always realized the importance of examining and preserving the pathologic or traumatic specimens, and so De Mortillet, Cartailhac, Nadaillac, De Baye, and others have reported many specimens bearing evidence of arrow wounds.

Fig. 196 represents a human vertebra pierced by an arrowpoint, tranchant transversal, from the cavern of Pierre-Michelot (Marne), collected by Baron de Baye. Fig. 197 represents a human tibia with an arrowpoint inserted, found in the dolmen of Font-Rial near Saint-Affrique (Aveyron). Baron de Baye has been, after Dr. Prunières, one of the most successful seekers for these specimens. In the cavern of Villevenard he found one skull containing three tranchant-transversal arrowheads, while another was lodged between the dorsal vertebræ. Other human vertebræ pierced with flint arrowpoints were found in the caves of Petit-Morin. In one sepulchral cavern the Baron found 73 flint arrowpoints, and, as in the case of Villevenard, their position was such as to lead to the supposition that they had been sticking in the flesh of the body at the time of interment and had fallen down as decomposition progressed. A human vertebra was found by M. Cartailhac in the covered ways of Castellet, near Arles, with a stone arrowpoint incrusted therein. The absence of any exostosis shows that death quickly followed. The list of examples or specimens showing arrow wounds might be augmented considerably, but enough instances have been given to show that the use of arrows and other weapons was habitual, and no reason is known why an investigation, if carried to any considerable extent and in any great detail, might not make a large addition to the data already obtained.1

HUMAN TIBIA (PREHISTORIC) PIERCED WITH FLINT ARROWPOINT (TRANCHANT TRANSVERSAL).

France.

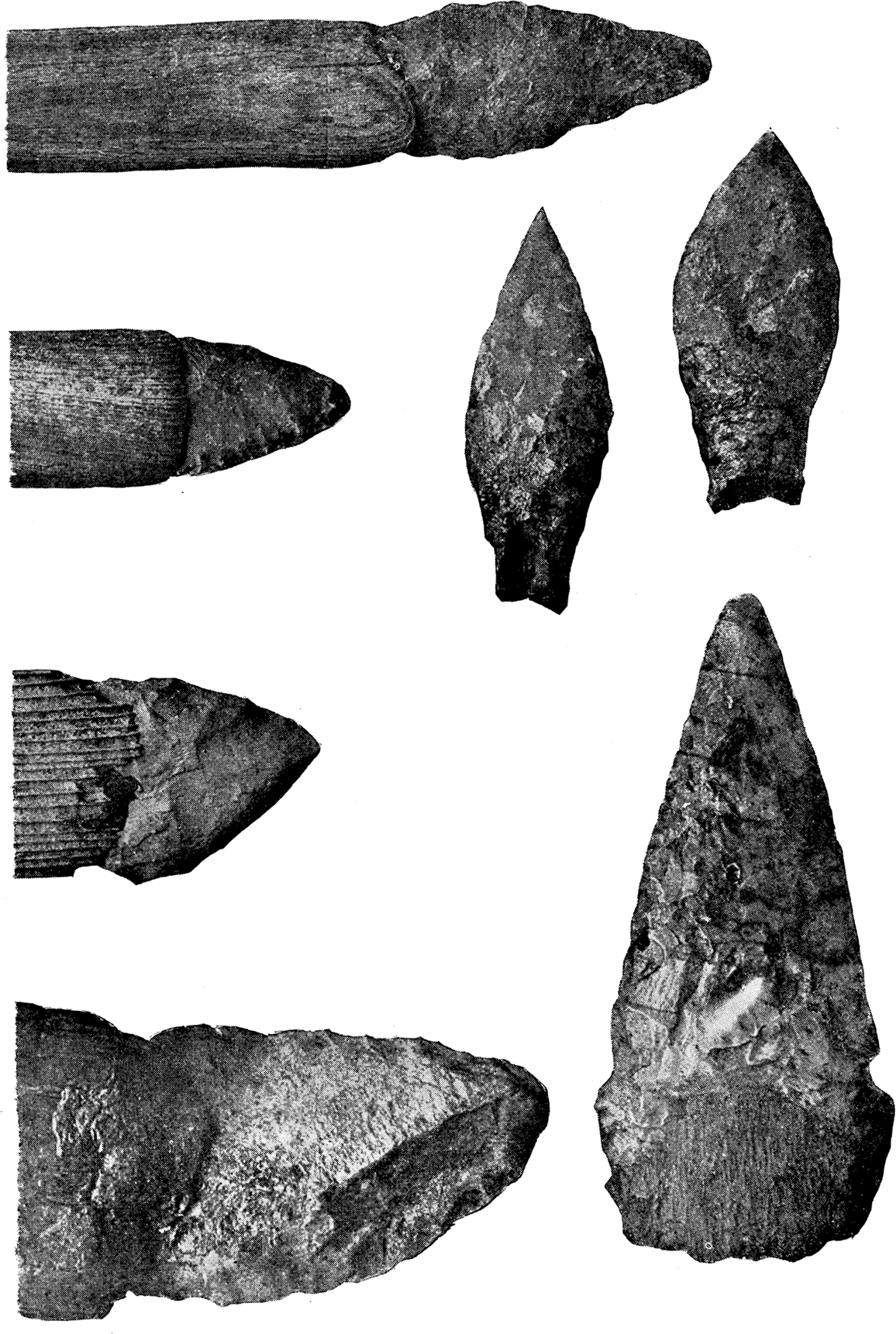

Fig. 198 (fig. 39—5531, Army Medical Museum) represents an ancient arrow wound in the skull of an aborigine. The skull was originally received by the Smithsonian Institution from Dr. O. Yates, Alameda County, California, and transferred to the Army Medical Museum. It shows a man of advanced age. A long flint arrowpoint had penetrated the skull through the left orbit, and the figure shows it in place as originally found impacted. This specimen is to be remarked as one of a class called perforators or drills and possibly used as such, but here used as an arrowpoint.

ANCIENT SKULL PIERCED WITH A FLINT ARROWPOINT, PERFORATOR.

California.

ARROWPOINTS OR SPEARHEADS INSERTED IN ANCIENT HUMAN BONES.

Cavern, Kentucky.

Cat. No. (loan) 1062, U.S.N.M.

Fig. 199 (fig. 37—5553, Army Medical Museum) is also a prehistoric specimen. It is from one of the Indian mounds in the vicinity of Fort Wadsworth, Dakota, excavated by Surg. A. T. Comfort, U. S. A., in 1869, and consists of a human lumbar vertebra with a small arrowpoint of white quartz incrusted in it. It is covered with a new bony formation, showing that the wounded man survived the injury some months at least.

ANCIENT HUMAN VERTEBRA PIERCED WITH QUARTZ ARROWPOINT, HEALED.

ANCIENT SKULL PIERCED WITH PERFORATOR ARROWPOINT.

Illinois.

Fig. 200 (Cat. Nos. 60281, 60282, U.S.N.M.) represents an ancient aboriginal skull from Henderson County, Illinois, forwarded by M. Tandy. It had a hole in the squamosal bone on the left side, in which, when found and received by the Museum, was a stone arrowhead, still another perforator or drill.

Fig. 201 (Cat. No. 173995, U.S.N.M.) represents a human skull from a mound in Missouri. The subject had received a serious wound in the supraorbital arch at the outside of the left eye. The wound involved all the bones of the interior arch, which was broken down. The wound had entirely healed, the cicatrization was complete, and all the wasted or destroyed pieces of bone around the wound had sloughed off and the reparation of the bone been fully effected. Of course the missile with which this wound had been inflicted did not remain in the wound, and it was not found, but from the smallness of the wound and its penetration one can only conclude it was made by an arrowpoint.

ANCIENT SKULL, ARROW WOUND OVER LEFT EYE ENTIRELY HEALED.

Missouri.

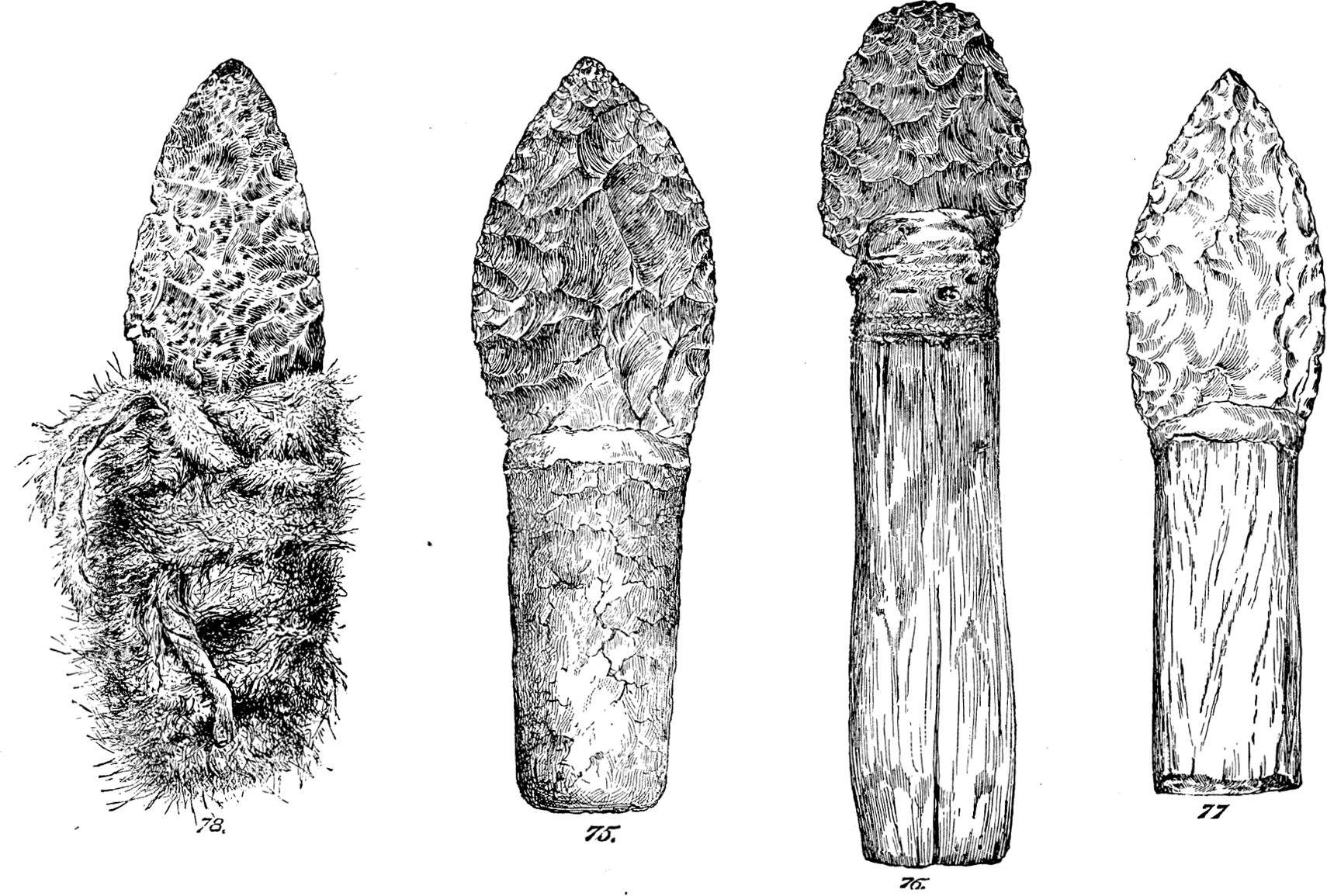

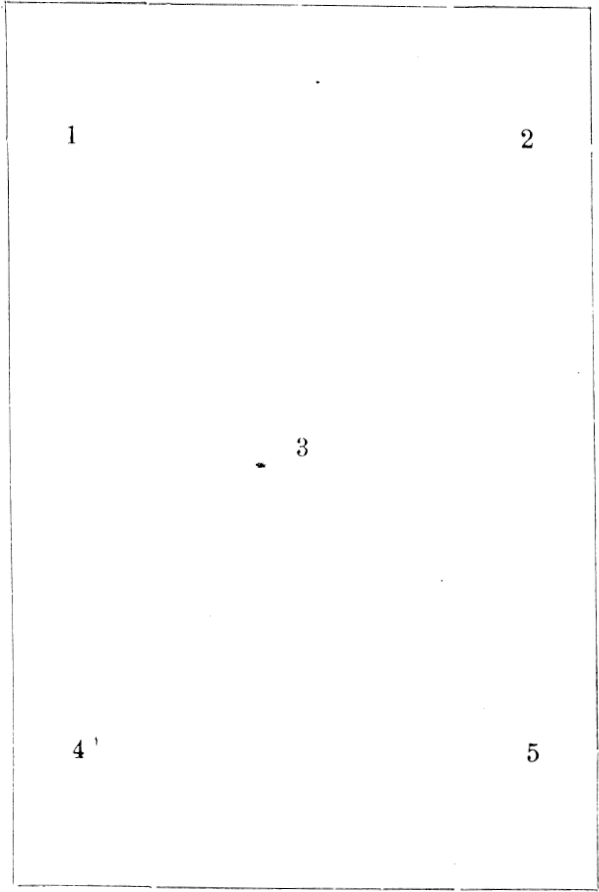

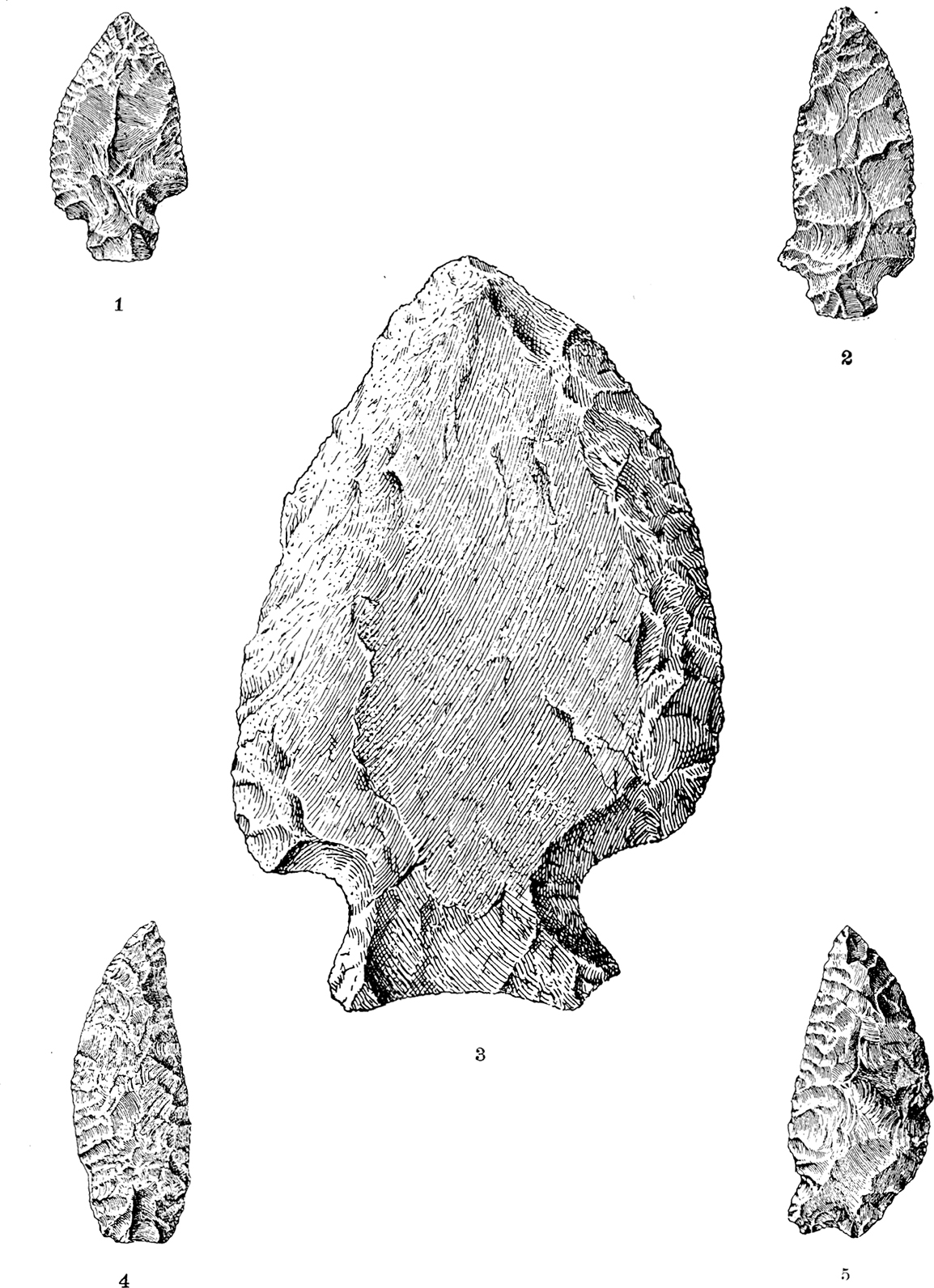

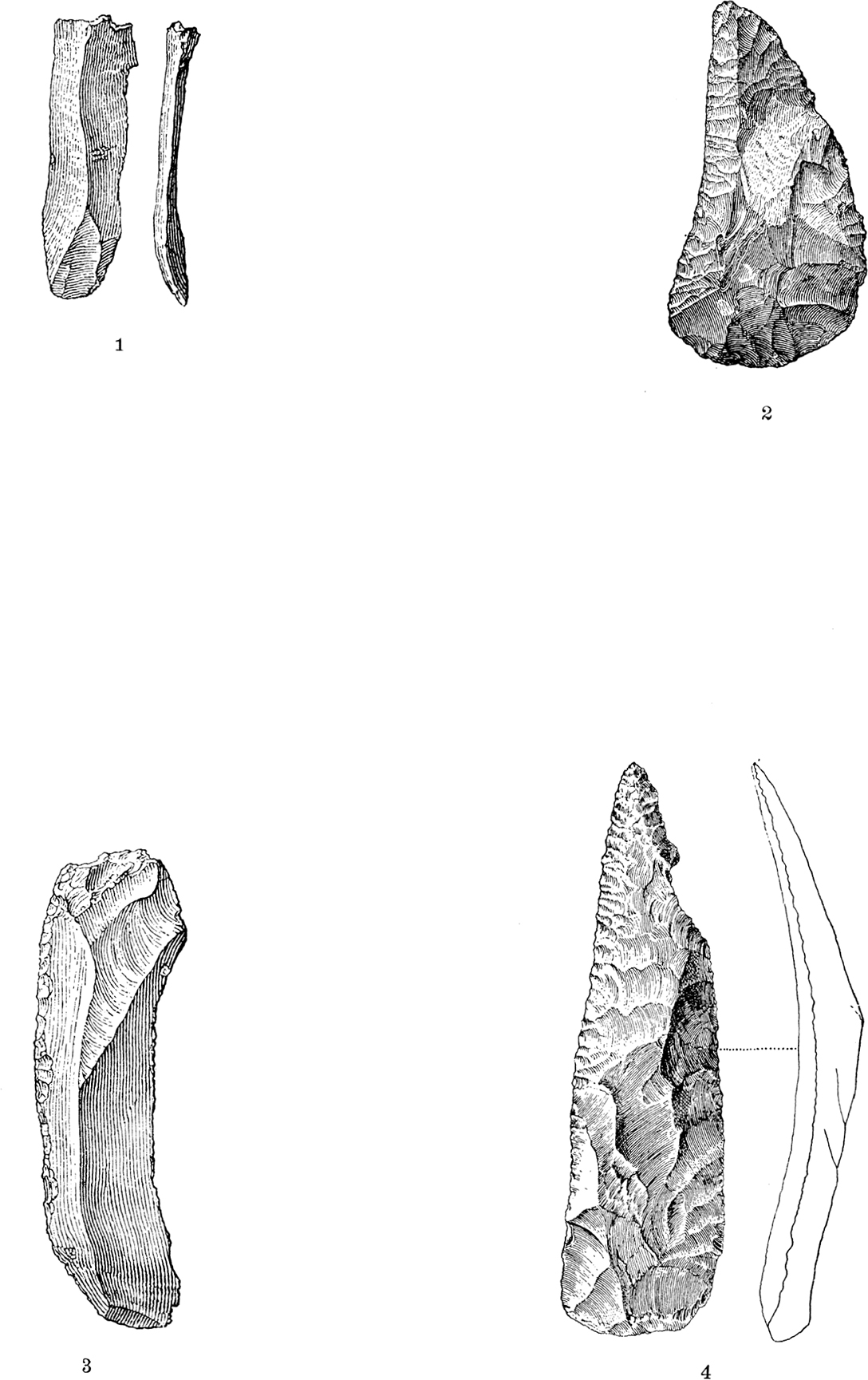

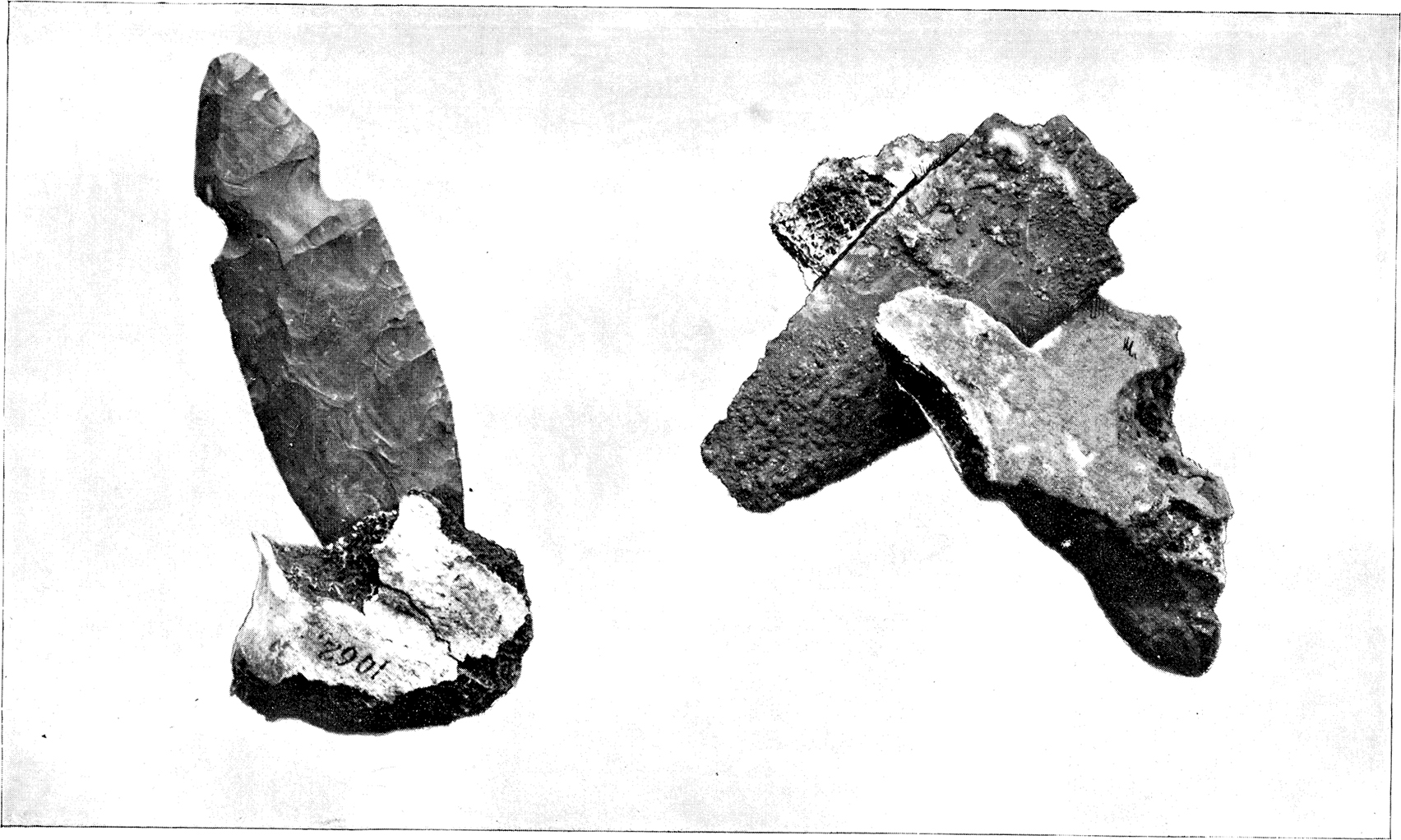

Plate 58 represents two prehistoric specimens of flint arrow or spear beads found inserted in human bones. These specimens were sent to the U. S. National Museum by Dr. John F. Younglove, of Bowling Green, Kentucky. Fig. 1 represents an implement  inches long,

inches long,  inches wide, and one-fourth of an inch thick. The stem is broken, which shortens it considerably. It had pierced entirely through the human pelvic bone in which it was found. Fig. 2 is 4 inches long,

inches wide, and one-fourth of an inch thick. The stem is broken, which shortens it considerably. It had pierced entirely through the human pelvic bone in which it was found. Fig. 2 is 4 inches long,  inches wide, and one-fourth of an inch thick. It is inserted in the head of a human femur(?). Fig. 1 is loose so that it may be taken out of its present socket, while fig. 2 is firmly embedded and can not be removed. The material of both is the black or brown lusterless pyromachic flint common to the country in which it was found. The specimens came from a cavern about 4 miles northeast of Bowling Green, and an equal distance from Old Station. The opening at the surface was about 3 feet in diameter and the hole about 40 feet in depth. At its bottom the cave extended horizontally several hundred feet through solid rock. There is no way of telling whether these implements were used as arrows or spears; the shafts which would alone determine that have entirely disappeared, or at least no fragments of either wood or sinews were reported. If arrows, they must have been used with an enormous bow; it is more likely that they were mounted upon a larger and heavier shaft and used as spears or javelins.

inches wide, and one-fourth of an inch thick. It is inserted in the head of a human femur(?). Fig. 1 is loose so that it may be taken out of its present socket, while fig. 2 is firmly embedded and can not be removed. The material of both is the black or brown lusterless pyromachic flint common to the country in which it was found. The specimens came from a cavern about 4 miles northeast of Bowling Green, and an equal distance from Old Station. The opening at the surface was about 3 feet in diameter and the hole about 40 feet in depth. At its bottom the cave extended horizontally several hundred feet through solid rock. There is no way of telling whether these implements were used as arrows or spears; the shafts which would alone determine that have entirely disappeared, or at least no fragments of either wood or sinews were reported. If arrows, they must have been used with an enormous bow; it is more likely that they were mounted upon a larger and heavier shaft and used as spears or javelins.

Looking at these heavy projectiles, considering the conditions of the hand to hand fight wherein they were used, and the force with which they were hurled, it is astonishing that at least one of the fighters, it the specimens belong to different individuals, not only survived the shock, but the patient recovered with the weapon embedded in the wound, for its cicatrization is found to be complete.