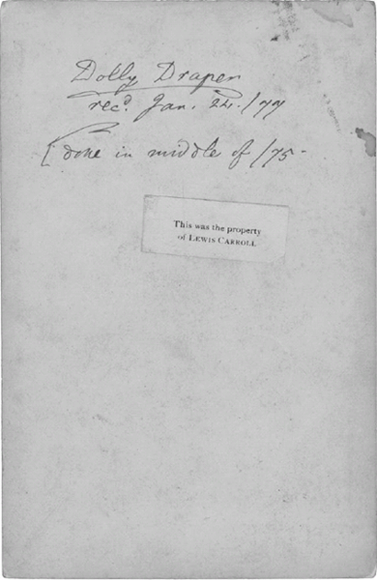

ON 24 JANUARY 1877 the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832–1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, wrote to Ellen ‘Dolly’ Draper, daughter of Ellen and Edward Thompson Draper, thanking her for a photograph of herself she had sent to him.1 As was his custom, Carroll marked the back of the print with the date of acquisition and the date the image was taken: ‘Dolly Draper rec’d Jan 24/77 done in middle of /75’. Not a photograph by him, but a photograph kept by Carroll, the costume piece had qualities in common with his own work: it ‘is just the sort of photograph I like doing: I take my little friends in all sorts of wild dresses and positions, and I have lately taken several little girls as “Penelope Boothby” in a mob-cap like the one you have on’ (VII, 19). I have located this photograph of Dolly Draper.2 It captures the twelve-year-old child lounging outdoors under a garden parasol (illus. 1). Even without the benefit of Carroll’s inscription on the reverse (illus. 2), the sitter’s identity is clear from the props to which his letter refers. For the cap is very like the one worn by Xie Kitchin in his portraits of her from the same decade and a large sleeping dog, mentioned in Carroll’s letter, is unmistakably present in the composition. Yet, with its relaxed garden setting, the mood of the photograph is different from his.

On 5 February of the same year Carroll sent a photographic portrait of himself to Dolly Draper, who remained for him at this point one of three ‘unseen little friends’. The carte de visite, an assisted self-portrait possibly taken in 1872, was printed at Henry Peach Robinson’s studio (illus. 3). It shows Carroll seated in semi-profile wearing a white bow tie. Holding a book on his lap, he looks low off to the right past the page he is in the process of turning.3 On 19 April 1877, however, two months after dispatching this likeness to her, Carroll corresponded further regarding images of Dolly Draper. This time, however, he wrote to her father thanking him for his ‘really overflowing generosity’ in sending ‘such a number of [his] photographs’.4 While there are no precise details of those images sent by Edward Draper, Carroll’s subsequent note to him, ‘I shall specially treasure those of Dolly’ (VII, 30), indicates that among them were several of the child. In all probability they resembled the extant photograph and, escaping the trappings of professional studios, their informality appealed to Carroll.

2 Reverse of Dolly Draper, 1875, with Lewis Carroll’s inscription.

As fellow amateur photographers Carroll and Draper were not unusual in exchanging prints by mail and during his lifetime Carroll acquired a number of photographs in this manner. Indeed, changing hands through the post, photographs were frequently on the move. Letters provided wonderfully convenient vehicles for transporting photographic portraits to places remote from the people and locations they depicted. For Carroll, as the Draper correspondence demonstrates, photographs sometimes accompanied letters. On occasion they provided the sole reason for sending them. In this context, as well as guaranteeing order, Carroll’s conscientiously maintained cross-referenced photographic and letter registers reflect a mutual involvement of their visual and linguistic entries.5 Although both of these encyclopaedic documents are now lost, the recorded existence of thousands of photographs and letters testifies to an important, though largely unremarked, closeness for Carroll between the two forms of expression, photography and letter writing. Letters facilitated connections between photographs and places. They did so not simply by detailing sittings for Carroll’s camera or by recording the circumstances of his purchase on his travels of cartes de visite. Rather, they provided a discursive space in which to explore conceptual connections, often intricate ones, between the medium of photography and particular locations.

This book is concerned precisely with such connections. It recognizes as central to them, as evident in the case of Dolly Draper, photographs of female children. The reference in my title to ‘photography on the move’ incorporates the geographical movement of Carroll as a nineteenth-century amateur photographer along with the migration of photographs themselves to places far from their points of origin. I range, therefore, from instances when Carroll travelled with his camera to those photographs he bought on his travels and had made in professional studios. His monumental trip to Russia without a camera in 1867, the subject of chapter Four, affected his subsequent ‘costume’ photographs in visibly distinctive ways, while his regular visits to Ore House, near Hastings, for speech therapy, explored in chapter Five, raised subtle connections between the nature of a photographic sitting and his experience of speech as imperfect. Theatrical events in London in the 1860s and ’70s, on the other hand, the focus of chapter Three, inspired photographic preoccupations anticipating those Carroll found in the seaside resort of Eastbourne in the 1880s, the focus of chapter Six. While, on the surface, he led a relatively sheltered life – most of it bound by the termly rhythms of Christ Church – places other than the college and the university town of Oxford loomed large in Carroll’s experience both actually and imaginatively. Accessed by the train, as chapter Two demonstrates, they fed his fascination for photography just as his experience of particular locations was itself shaped by photographic interests.

3 Lewis Carroll, Self-portrait, 1872(?), albumen print.

Yet the phrase ‘photography on the move’ alludes also to Carroll’s interest in what he thought of as ‘moving pictures’. These took many forms. Quite apart from theatrical performances in conventional auditoria, Carroll enjoyed a host of popular spectacles such as swimming entertainments, skating and acrobatics taking place in novel venues. I am interested in what he regarded as the capacity of the ‘still’ photograph to preserve movement, as it were, in such contexts. Towards the end of his life, in 1886, such an impulse to capture the virtuosity of a range of performers found fruition in his play Alice in Wonderland: A Musical Dream Play.6 It also gestured towards emerging cinema.

Carroll bought his first camera on 18 March 1856 from Ottewill and Company in London, nine years before the publication of what would become his most well-known book, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Costing £15, the purchase represented a serious investment for a prospective amateur photographer and when the portable folding rosewood box arrived on 1 May he began to experiment with ‘spoiled collodion’ that his friend Reginald Southey had given to him (II, 67).7 With Southey’s help, Carroll was soon adept at the new technology and for the next 24 years – using the wet collodion process that required considerable skill to secure good results – he took, processed, mounted and catalogued photographs at every available opportunity.

Not all amateurs were able to master with the assurance Carroll did the photographic method made available by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851.8 Firstly, a negative, a sheet of glass the same size as the eventual print, had to be coated with collodion made from gun cotton – cotton dissolved in nitric and sulphuric acid – mixed either with ether, or alcohol and potassium iodide. After a few seconds, the photographer dipped the glass plate in a bath of nitrate that reacted with the potassium iodide to form light-sensitive silver iodide. The plate was then exposed in the camera. At all times during the intricate process the plate had to remain damp, hence the name ‘wet-plate process’. Once exposed the plate was developed immediately in a solution of pyrogallic and acetic acids, fixed and washed. Opportunities for error were considerable throughout the process; debris such as dust or a hair would be captured as an eternal fault on the eventual print. At first, managing with makeshift arrangements that often involved setting up his equipment in the homes of friends, from 1863 Carroll rented a space in Badcock’s Yard in St Aldates. Finally, in 1872, he had a glass studio constructed above his rooms at Christ Church. There, Carroll continued to take photographs regularly; at the time of his death in 1898 his records indicate around 3,000 negatives. From the first assembling albums of those photographs he took, as Edward Wakeling indicates, his personal effects included ‘thirty-four photographic albums, not all of these contained exclusively his own photographs’; of these ‘at least twelve’ have survived.9

The physical act of taking a photograph, from the initial sitting to the final print together with those technical skills it required, fascinated the author of the Alice books and preoccupied him for a significant period of his life.10 He began photography at a time when the medium was still relatively new and held considerable intrigue. During its early decades photography possessed a peculiar cultural status, one signalled by its combined mechanical, physical and chemical origins. Unlike those manual methods of reproduction that preceded it, such as engraving, photography eliminated the trace of a hand; the causal, or indexical, connection to a referent determined the unique materiality of the photographic print. By a seemingly perfect correspondence with the object, together with those negative/positive shadow/light dichotomies that mark a temporal dimension to its presence as burnt into the plate, a photograph is always belatedly the thing it represents.

In 1880 Carroll recorded taking what appears to have been his last photograph and scholars have speculated upon this apparently sudden termination of one of his favourite activities. Some argue that he lost interest in the medium. Others cite as a primary cause the replacement of the wet plate photographic process by the dry plate. Still others eschew technical reasons in favour of personal ones, suggesting that Carroll’s concern over increasing gossip about his relationships with girls and young women determined his decision.11 Yet, as this book will demonstrate, effectively Carroll did not ‘give up’ photography in 1880. Since throughout his life he had sourced, and frequently bought, images by other photographers, post 1880 he continued to do so. In addition, he contrived opportunities to have photographs taken for him. He was involved in the hire of a camera and orchestrated photographic sittings at professional studios. As he continued to invest in them as material objects, and in the medium as a unique conceptual vehicle, Carroll accommodated in different ways what remained an enduring impulse to acquire photographs. Anticipating what Roland Barthes later referred to as ‘clocks for seeing’, cameras, and the business of photography, could not simply be put aside in the latter stages of his life.12

Carroll was therefore as much an owner and consumer of photographs as a maker of them. Yet his reputation as an auteur, an accomplished practitioner, has to some degree obscured his identity as an avid purchaser and collector of cartes de visite and other photographic forms. Carroll owned many studio and amateur portraits of children. Some of these originated from sittings he superintended. Others he sourced from studios and shops. Some he solicited from friends and acquaintances, or, as in the case of Dolly Draper, from children themselves. Carroll notes, for example, in his diary for 14 June 1869, a visit to meet the mother of a child, Mary Beatrix Tolhurst, whose photograph he had admired at the house of an acquaintance (VI, 89). On 3 August of that year he invited Charles and Elizabeth Tolhurst of Bracknell to Oxford so that he might photograph Beatrix. Though Carroll’s photographs from that session have not come to light, I have located a carte de visite of the child he received subsequently in 1871. Made in the studio of Byrne & Co., Richmond, it shows the eight-year-old Beatrix Tolhurst posing with a hoop beside a highly carved table (illus. 4).13 Branches appear in the foreground to accentuate the simulated woodland scene evident in the backdrop. In his signature violet ink, Carroll has neatly spaced on the front of the card her name and ‘Xmas 1871’. Few such studio portraits in Carroll’s possession appear to have survived, however, but those that have alter a well-rehearsed story.

In the light of such circumstances, exhibitions of Carroll’s photographs always appear somewhat misplaced. Not simply in the sense that, transposed from the intimate leaves of albums to large gallery spaces, many nineteenth-century photographs do, but also because understanding of what photographs meant for Carroll changes in the context of photographs taken by others he owned, sought to own and, in some cases, treasured. Geoffrey Batchen, considering the modern snapshot, has rightly pointed out how traditional models of authorship from art history fail where that popular and very personal photographic form is concerned.14 While there are obvious differences between nineteenth-century cartes and modern snaps, the former anticipate in vital ways the conundrum posed by other people’s snapshots, ‘boring’, as they often are, to anyone without a personal investment in them. Since Victorian studio conventions encouraged repetition of particular visual codes through props and backdrops – the familiar Doric column or sylvan vista – many photographic portraits of the period appear impersonal, meaningless even, to those encountering them without a connection to their subjects. It is for similar reasons that photographs Carroll acquired have generated little interest aside from as documents supplying faces to the names of actors in his life. Yet, akin to snapshots, such seemingly innocuous studio and amateur portraits are significant for the circumstances of their origins and the sentiments they aroused in their owner. Those sentiments themselves accrue through the personal attachment of such images to specific times and places.

4 Byrne & Co., Richmond, Beatrix Tolhurst, received by Carroll, 1871, carte de visite.

This book seeks to remember some of these forgotten photographs and to consider their significance to Carroll alongside photographs he took himself. For as material objects to which he was attached, such studio and amateur photographs – read in the context of his diaries and letters in which Carroll frequently alludes to their acquisition – reveal a great deal about the aesthetic, technological and conceptual capabilities of the medium that absorbed him. The attachment of photographs to particular places also demonstrates the limitations involved in separating aesthetic from psychic and social concerns in Carroll’s work. I thereby explore photographs Carroll took, variously acquired, and hoped to acquire. I am interested in those ways in which he conceived them; inscribed them; displayed them; dispatched them by post; sequenced them in albums; and subsequently presented those albums to children and parents to encourage others to be pictured. Those photograph albums in turn provided vital triggers for conversation and the spinning of stories.15 So too did a number of studio portraits he commissioned. To parcel off photographs he created from those Carroll collected is to curtail understanding of his investment in the medium as closely involved with habitual aspects of his life. Much remains to be told about Carroll’s consumption of photographs. The acts of sourcing, trading and collecting them, in addition to taking and processing photographs, were vital components of a larger ‘photographic’ impulse that attached to place and moved with Carroll when he travelled.