Figure 10.1 Duration of asthmatic responding at bedtime during baseline and extinction phases (Neisworth & Moore, 1972).

In many applied and clinical situations the behavior analyst is faced with the task of decreasing behaviors that may be maladaptive for the client. In such situations there should of course be a very clear rationale for the need to reduce behaviors. Maladaptive behaviors may be generally defined as behaviors that result in some form of negative outcome for the person or for others. For example, a child's aggression towards other classroom students may result in physical harm to those students, or harm to the aggressive child through retaliation. The aggressive child might also be removed from the classroom setting, thereby losing access to appropriate educational opportunities. Again, the behavior analyst must conduct a rigorous assessment of the function of the behavior and establish a firm rationale for reducing such behavior prior to any intervention (see Chapter 7).

It is rare to see behavior change programs that are designed exclusively to reduce maladaptive behaviors. Typically, interventions consist of a combination of strategies designed to decrease maladaptive responding while simultaneously increasing appropriate responding. Many of these strategies were described in Chapter 9. These programs ideally consist of a three-stage process. This includes: a) a functional analysis to identify the maintaining contingencies; b) elimination of those maintaining contingencies for the aberrant behavior (through extinction); and c) presentation of the reinforcer that previously maintained the aberrant behavior, but is now contingent upon appropriate alternative behaviors (Reichle & Wacker, 1993). Such programs thus include the use of positive reinforcement to enhance appropriate behavior. However, in some situations it may simply not be possible to use this three-stage process to develop interventions to reduce maladaptive behavior. For example, in some cases a functional analysis may not be successful in revealing maintaining contingencies, and if these contingencies remain unknown then it is technically impossible to place the behavior on extinction. In such circumstances, punishment strategies may be required to achieve behavior change (Lerman, Iwata, Shore, & DeLeon, 1997). In other circumstances, although the function of the maladaptive behavior is clear, it may not be possible or desirable to replace the maladaptive behavior with alternative behaviors. For example, if a child's night time wakings are maintained by parent attention (that is, the parent enters the child's bedroom and comforts the child when crying begins or continues), then the intervention of choice may be to place the child's crying on extinction (that is, the parent should no longer enter the child's bedroom contingent upon crying). In this situation it would not be appropriate to replace the child's crying with a functionally equivalent alternative behavior.

Because functional analysis combined with positive reinforcement strategies may not be sufficient to deal with all behavioral problems, it is important that the behavior analyst be familiar with behavioral techniques that can be used to reduce maladaptive behavior. Additionally, it is essential that the behavior analyst be familiar with the basic principles of behavior from which these technologies are derived. In Chapters 3 and 5, the fundamental properties of extinction and punishment as identified in basic research were described. While both extinction and punishment result in an overall reduction in responding, there are other characteristics of responding when behavior is either punished or placed on extinction (such as the extinction burst, or the possibility of avoidance behavior following the introduction of punishment). The behavior analyst must be aware of all characteristics of these behavior reduction strategies in order to implement such strategies efficiently and effectively.

In this chapter the use of extinction and punishment procedures in applied settings will be described. Some of the general ethical issues surrounding the use of these techniques (particularly the use of consequences that may be described as aversive in treatment strategies) were reviewed in Chapter 5, and specific issues are dealt with in the present chapter. In the final chapter, these issues will be related to the human rights of individuals in treatment. Suffice it to say at this point that aversive consequences should be considered as a treatment of last resort and only administered under strict guidelines.

Extinction was defined in Chapter 3 as a procedure in which the contingency between the reinforcer and response is removed. The eventual outcome of this process is a reduction of the rate of the behavior towards its operant level. Other properties of behavior during the extinction process include topographical changes in responding, extinction bursts, extinctioninduced aggression, and spontaneous recovery. We noted in Chapter 9 that researchers have taken advantage of topographical changes in responding under extinction conditions to teach novel behaviors, and the other behavioral effects of extinction will be discussed in this section.

As noted in Chapter 3, extinction can be accomplished in two ways. First, the reinforcer can be removed or eliminated completely. Second, the reinforcer can be delivered but in a noncontingent manner. While both of these procedures effectively extinguish behavior there may be distinct applied advantages for using noncontingent delivery of reinforcing stimuli rather than eliminating the reinforcer entirely in many instances. This will be discussed in detail later in this section. Obviously, for extinction to be effective, the reinforcer for the maladaptive behavior must be clearly identified prior to the intervention. Recent research has identified the importance of using functional analysis methodologies to identify the operant function of behavior prior to implementing extinction, and this research will be described in Section 10.2.

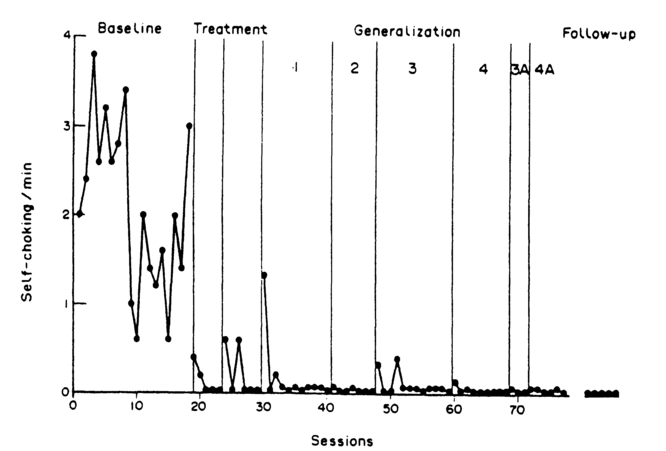

An extinction burst has been defined as a transitory increase in responding almost immediately after shift to an extinction procedure when reinforcers are no longer forthcoming for that response. This effect has been reported in several applied behavior analysis studies (for example, Iwata, Pace, Kalsher, Cowdery, & Cataldo, 1990). In an early example, Neisworth and Moore (1972) trained parents to ignore the asthmatic behavior of their child. In this particular example of extinction, the reinforcer was eliminated completely. The child's asthmatic behavior, which consisted of coughing, wheezing, and gasping, usually occurred in the evenings around bedtime. During the extinction procedure, the parents did not attend to his asthmatic attacks once the boy was put to bed. Additionally, the boy received a monetary reward contingent on reductions in asthmatic behavior. The duration of coughing and wheezing was measured once the child was placed in bed. The results of the intervention are displayed in Figure 10.1. The effectiveness of this intervention was evaluated using a reversal design. It is clear from the data that there is an immediate increase in the duration of asthmatic behavior once the intervention is implemented. Asthmatic behavior then decreases dramatically under the intervention condition. A return to baseline results in an increase in asthmatic behavior and once again we see an extinction burst when the intervention is applied for the second time. The second extinction phase also seems to demonstrate another fundamental property of extinction. In this second phase the extinction process is more rapid and contains fewer responses (see Chapter 3 for experimental studies of this effect). However, this additional interpretation of the second extinction phase must be viewed with caution, as the target behavior was not allowed to return to original baseline levels of responding in the second baseline phase. This illustrates an ethical concern often present in applied studies; in this case, considerations of the boy's health led to modification of the procedure used.

Figure 10.1 Duration of asthmatic responding at bedtime during baseline and extinction phases (Neisworth & Moore, 1972).

The occurrence of the extinction burst has been put forward as one of the major drawbacks for using extinction as a sole therapeutic intervention in applied contexts (see, for example, Kazdin, 1994). It may be difficult for staff or parents to tolerate an initial increase in responding no matter how benign the undesirable behavior might be. There would be obvious ethical problems with using extinction in cases where the behavior was of danger to the client or others. Additionally, parents or staff may interpret the increase in intensity of the behavior as a failure of the behavioral program and may therefore revert to reinforcing the behavior. This may in effect shape the targeted behavior into a more intense form of aberrant behavior. However, the extinction burst may not be as common as previously implied in introductory text books on applied behavior analysis (for example, Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 1987). in fact there are not large numbers of applied demonstrations of the extinction burst. Lerman and Iwata (1995) systematically examined the prevalence of the extinction burst in a sample of 113 sets of extinction data. They found that increases in frequency of behavior when extinction was applied occurred in only 24% of the cases studied. In a subsequent analysis of the basic and applied research literature on extinction, Lerman and Iwata (1996) concluded that continued research is needed to directly examine the functional properties of the extinction burst.

It was noted in Chapter 3 that the extinction burst seems to be associated with one particular operation of extinction. The extinction burst seems to occur when the reinforcer is no longer available, and not under the alternative extinction operation where the contingency between the behavior and the reinforcer is broken but the reinforcer continues to be delivered in a noncontingent manner, in Chapter 9 we noted that the noncontingent delivery of reinforcing stimuli (NCR) can be an effective method to rapidly decrease aberrant behavior. During NCR interventions, reinforcement is typically delivered on a fixed-time schedule and is not influenced by the client's behavior. The formal definition of a fixed-time schedule of reinforcement is one in which the reinforcer is delivered after a fixed period of time, regardless of whether or not a response occurs, delivery of the reinforcer is thus not contingent on the behavior. It is instructive to compare the effects of eliminating the reinforcer for the target behavior (as demonstrated above in Neisworth & Moore, 1972) with delivering the reinforcer noncontingently. Figure 10.2 illustrates the effects of delivering attention noncontingently for self-injurious behavior that is maintained by attention (Vollmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, & Mazaleski, 1993). Self-injury for Brenda consisted of banging her head on solid stationary objects and hitting her head with her fist. A functional analysis identified social attention as the maintaining contingency for self-injury. Attention was then delivered on a fixed time schedule. Self-injury was measured as number of responses per minute and NCR was evaluated using

Figure 10.2 Responses per minute of self-injurious behavior during baseline when attention is delivered contingent on self-injurious behavior and during NCR intervention (phase 2 in the graph) when attention is delivered noncontingently (Vollmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, & Mazaleski, 1993).

an ABAB design (with a DRO intervention implemented in the final B phase). The results of the NCR intervention demonstrate an almost immediate elimination of self-injurious behavior. No extinction burst or gradual reduction in self-injurious behavior occurred. Vollmer et al. (1993) subsequently hypothesized that NCR produces such dramatic reductions for two possible reasons. First, the contingency between responding and the reinforcer is removed (that is, extinction is in effect). Second, the person continues to have access to the reinforcer on a relatively rich (although noncontingent) schedule which may result in satiation. Noncontingent delivery of reinforcing stimuli may therefore act as a form of extinction and as an abolishing operation: while levels of deprivation can establish a stimulus as a reinforcer, or increase the power of a stimulus as a reinforcer, the opposite operation is also equally possible. Satiation with a stimulus can abolish that stimulus as a reinforcer, at least for the time being. In other words, a rich schedule of noncontingent delivery of a reinforcer may abolish that stimulus as a reinforcer, in addition to breaking the contingency between the response and the reinforcing stimulus. This provides two mechanisms by which the procedure can be effective in eliminating unwanted behavior, without creating any of the ethical problems that can arise when access to a highly-preferred reinforcer is restricted.

The elimination of a reinforcer for a behavior often results in a gradual decrease in responding until the behavior ceases to occur. The rate of this gradual reduction in responding can be attributed to prior history of reinforcement for that response. There is ample basic research to demonstrate that intermittent schedules of reinforcement can increase resistance to extinction (Mackintosh, 1974, and see Chapter 3). However, little systematic applied research has demonstrated a functional relationship between history of conditioning and resistance to extinction (see Lerman & Iwata, 1996, for a review of relevant studies).

In applied studies, this gradual reduction in responding may be particularly problematic when the target behavior is dangerous to self and others. Additionally, many aberrant behaviors may have a long history of intermittent reinforcement prior to the application of extinction. This may result in persistence of responding under extinction conditions. In an early and often-cited example of the use of an extinction protocol with severe aberrant behavior, Lovaas and Simmons (1969) systematically removed all attention contingent upon head-banging for a child with severe disabilities. Extinction was the sole treatment used in this particular case. The child was placed alone in a room and was unobtrusively observed over an extended period of time. The authors concluded that extinction eventually occurred but only after an extensive amount of self-injury had occurred.

To allow a child to engage in such destructive behavior for extended time periods is generally agreed to be inappropriate, and this study is sometimes used as an example to caution therapists against using extinction as a sole intervention with such behavior disorders. It is important for behavior analysts to consider the results of basic and applied research which demonstrates this gradual reduction in responding during extinction under more controlled experimental conditions. This phenomenon is readily demonstrated in the laboratory, as illustrated in Chapter 3, but has rarely been systematically observed in applied settings.

Another behavioral phenomenon associated with the process of eliminating reinforcement is that of spontaneous recovery. As noted in Chapter 3, spontaneous recovery means that there is a temporary reemergence of the behavior under the extinction condition. Under experimental conditions, the recovery of responding is typically not as strong as original responding prior to the extinction program. The danger with spontaneous recovery during applied interventions is that the behavior may be unwittingly reinforced by those caregivers who are implementing the extinction program. Reinforcement during spontaneous recovery could place the behavior on an intermittent schedule of reinforcement and thus make it more difficult to eliminate.

Spontaneous recovery is clearly illustrated in an applied intervention to decrease nighttime waking in young children through extinction (France & Hudson, 1990). Nighttime waking, which occurs with approximately 20 percent of children, can cause severe disruption for parents. In this study the parents of seven children were trained to ignore nighttime wakings. Nighttime waking was operationally defined as sustained noise for more than 1 minute from the onset of sleep until an agreed upon waking time for the child the next morning. The effectiveness of the intervention was examined using a multiple baseline design across children (see Figure 10.3). The frequency of night wakings each week was plotted during baseline, intervention, and follow up assessments. These results clearly illustrate gradual decreases in the frequency of night wakings once the intervention was implemented. Additionally, there are clear instances of spontaneous recovery with all children during the intervention phase.

One of the most frequently described side effects of placing behavior on extinction is the occurrence of extinction-induced aggression. Breaking the contingency between behavior and reinforcement seems to constitute an aversive event which results in aggression and other forms of agitated behavior (Lerman & Iwata, 1996), and there is ample evidence from experimental studies to document this effect (see Chapter 3).

The occurrence of aggression under extinction conditions is sometimes cited as one of the reasons for not recommending the use of extinction as the sole treatment in applied settings (e.g., LaVigna & Donnellan. 1986). Unfortunately, little applied research to date has documented such side effects of extinction. In fact, some studies have shown that such agitated side effects may not occur in many cases where extinction is applied. For example, Iwata, Pace, Kalsher, Cowdery, and Cataldo (1990) examined the influence of extinction on self-injurious behavior that produced escape from tasks for seven individuals with developmental disabilities. Extinction consisted of not allowing participants to escape from demanding situations contingent upon self-injurious behavior; a procedure which is commonly described as escape extinction. Iwata et al. (1990) found that brief extinction bursts occurred, but no agitated side effects were reported.

Figure 10.3 Frequency of night wakings for seven children under an extinction intervention. The large solid dots represent nights in which the infant was ill. Some level of spontaneous recovery is evident with all children (France & Hudson, 1990).

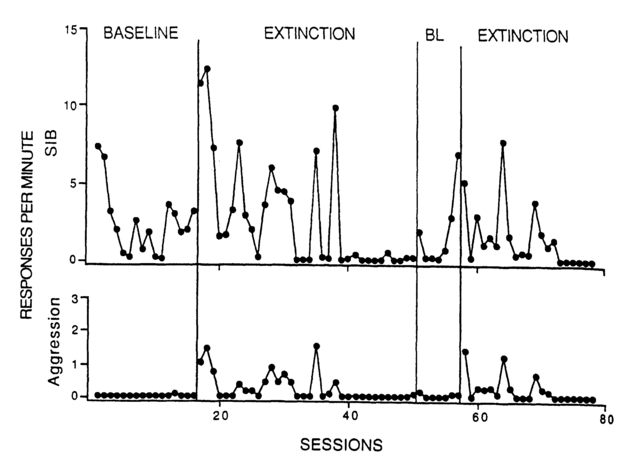

This is not to say that extinction-induced aggression has not been reported in applied research. For example, Goh and Iwata (1994) carried out a rigorous assessment of extinction-induced aggression for a man with severe disabilities who engaged in self-injurious behavior in order to escape from demanding tasks. During the extinction condition, self-injurious behavior did not result in escape from tasks. An evaluation of the escape extinction intervention was conducted using a withdrawal design (see Figure 10.4). In the baseline phases of the design, self-injurious behavior produced escape from demanding tasks. In addition to examining self-injurious behavior under baseline and extinction conditions, the authors also examined aggression under these experimental conditions (aggression is plotted separately in Figure 10.4). This data set demonstrates some of the fundamental properties of extinction such as the extinction burst, a gradual reduction of behavior during extinction, and a more rapid extinction process during the second application of extinction. Additionally, the presence of aggression is also clearly documented when the extinction process is implemented on both occasions.

Extinction-induced aggression seems to occur occasionally when extinction is implemented as the sole intervention. The applied behavior analyst should seriously consider the implications of such a possibility when planning to implement an extinction program. Those who will implement the program must be aware and prepared for the potential occurrence of aggression. If there was a potential danger of serious aggressive outbursts (for example, when working with an adult client with a history of aggressive behavior) then the use of extinction alone may not be a practical choice of treatment.

Figure 10.4 Rate of self-injurious behavior (upper panel) and aggressive responses (lower panel) for an individual under baseline and extinction intervention (Goh & Iwata, 1994).

It was noted in Chapter 3 that resistance to extinction can be influenced by the effortfulness of responding, if responding requires more physical effort during extinction, then extinction will occur more rapidly. While this phenomenon may have significant applied implications for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of interventions using extinction it has not received a significant amount of attention in the applied behavior analysis literature (Friman & Poling, 1995; Lerman & Iwata, 1996). Response effort has been systematically manipulated in several recent applied studies (Horner & Day, 1991; Shore, Iwata, DeLeon, Kahng, & Smith, 1997; Van Houten, 1993). During these studies extinction was not in effect for the target responses. However, an examination of the influence of response effort in some of these studies is instructive and may present avenues for future research involving the manipulation of effort under extinction conditions within applied contexts.

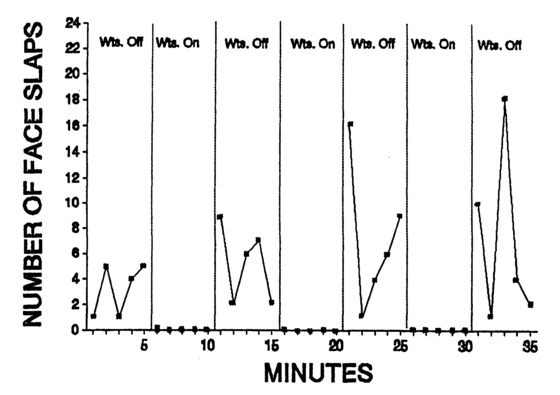

Figure 10.5 The number of face slaps per minute when wrist weights were on and when they were off (Van Houten, 1993).

Van Houten (1993) evaluated the influence of an intervention which consisted of placing wrist weights (1.5 lbs each) on a boy who self-injured. The boy was diagnosed with severe developmental disabilities and engaged in high rates of face slapping. The effects of wrist weights on the number of self-injurious face slaps were initially evaluated using a withdrawal design (See Figure 10.5). The wrist weight condition eliminated face slapping. Additionally, Van Houten (1993) also reported that the boy continued to engage in adaptive toy play under the wrist weight condition. Wrist weights therefore eliminated self-injurious behavior (SIB) but did not interfere with adaptive behavior for the boy. These results seem to indicate that the wrist weights eliminated hand-to-head SIB by increasing the effortfulness of responding.

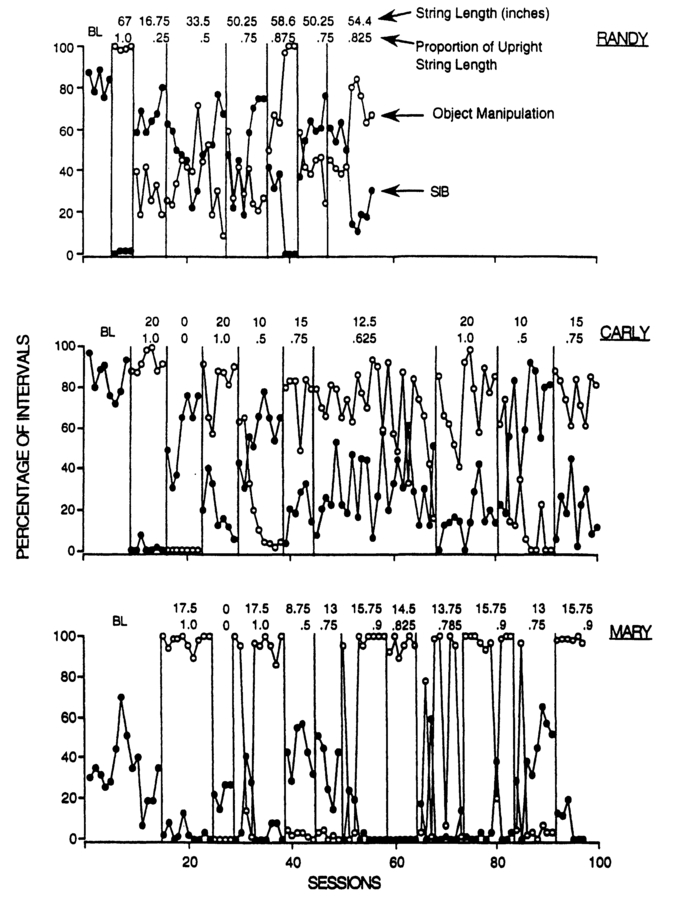

Shore et al. (1997) examined the influence of response effort on reinforcer substitutabiIity for three individuals with SIB. Functional analyses prior to the intervention indicated that SIB appeared to be maintained by automatic reinforcement for all three individuals. Following the functional analysis a preference assessment (see Chapter 9 for a description of preference assessment protocol) was conducted to identify highly preferred leisure stimuli for these individuals (i.e, vibrating massager, plastic rings, and a small plastic tube). The effortfulness of manipulating these preferred stimuli was then systematically evaluated and the results of this evaluation are presented in Figure 10.6. When the leisure materials were not available then all three individuals engaged in high levels of SIB (see baseline phase of each graph). When the participants had free access to the leisure materials (phase 2 of the graphs) then SIB was almost completely eliminated and all participants engaged in high levels of manipulation of the leisure materials (described as object manipulation in the graphs). The leisure objects were then secured by a piece of string to a work top or table. The effortfulness of responding or accessing the leisure materials (i.e., by bending over the table) was systematically examined by varying the length of string. The remaining phases of the graphs illustrate the influence of varying the length of string and thereby the effortfulness of manipulating the leisure objects. Overall, the results demonstrate that as the effortfulness of manipulating the leisure objects increased there were decreases in object manipulation with corresponding increases in SIB.

Both of these research examples demonstrate that effortfulness is a potentially important variable to examine in applied settings. These studies showed that increases in response effort could eliminate SIB (Van Houten, 1993) and result in changes in response allocation (Shore et al., 1997). To date, no study has examined the influence of changes in response effort for behavior that is placed on extinction in applied settings. If increasing the effortfulness of responding can result in a more rapid reduction of behavior when extinction is in effect then the empirical examination of such techniques in applied contexts warrant scrutiny.

Figure 10.6 Percentage of intervals containing SIB and object manipulation during baseline (BL) and across effort (string-length) conditions for three participants. Numbers above each condition indicate length of the string attached to an object (top number) and proportion of string length while the participant was seated in an upright position (bottom number) (Shore, Iwata, DeLeon, Kahng, & Smith, 1997).

For extinction to occur, the contingency between responding and reinforcement must be removed. One of the first important steps prior to implementing an extinction program is to identify what reinforcers are maintaining the targeted behavior. Functional assessment or analysis techniques should therefore be used prior to implementing an extinction program in order to identify maintaining contingencies. In fact, the extinction protocol used in a subsequent intervention will be determined by the function of the behavior to be extinguished. Many texts which discuss applied behavior analysis interventions have described the application of extinction in terms of ignoring the target behavior when it occurs (e.g., LaVigna & Donnellan, 1986). This implies that the behavior is maintained by attention from those who are doing the ignoring. We have already described several examples of extinction protocol with behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement (i.e., attention from others) and social negative reinforcement (i.e., escape from demanding instructional situations) earlier in this chapter. The extinction procedures described earlier in these studies differed depending on the functional properties of the behavior to be extinguished. For example, with behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement, the reinforcer was either removed (through ignoring occurrences of the behavior) or delivered noncontingently (on a fixed-time schedule). For behavior maintained by social negative reinforcement an escape extinction protocol was implemented whereby the individual was no longer allowed to escape from ongoing activities contingent upon the target behavior. Additionally, the contingency between the target behavior and escape can be broken by allowing the individual to escape from ongoing activities on a fixed-time schedule (Vollmer, Marcus, & Ringdahl, 1995). Extinction protocol can therefore differ dramatically depending on the maintaining contingency for the target behavior.

In fact, if the function of the target behavior is not identified prior to the intervention, the behavior analyst could unwittingly select an "extinction intervention" that may actually reinforce the behavior. For example, a student may leave his desk in order to escape instructional interactions with the teacher (i.e., the behavior is negatively reinforced by escape from tasks). The teacher typically admonishes the student when he leaves his desk at inappropriate times. The teacher might then infer that the student's inappropriate out of seat behavior is maintained by teacher attention (i.e., is positively reinforced by attention from the teacher). Under this false assumption the teacher may opt to place the behavior on extinction by ignoring out of seat behavior. In this particular situation the teacher's use of "extinction" may actually result in an increase in out of seat behavior. It would have been more appropriate for the teacher to implement an escape extinction protocol whereby the student was not allowed to escape ongoing academic activities.

In some instances of SIB with individuals with developmental disabilities the aberrant behavior may be maintained by automatic or sensory consequences, it is hypothesised that the self-injurious response directly produces the stimulation that acts as the reinforcer for responding with these individuals. Automatic reinforcement of SIB is usually concluded when levels of SIB are not sensitive to changes in social contingencies and/or S!B occurs when the individual is alone. Extinction interventions designed to eliminate behavior maintained by social positive or social negative reinforcement will have little effect on automatically reinforced responding. Extinction protocol for SIB that is automatically reinforced usually consists of techniques designed to eliminate stimulation that is directly produced by the response (Rincover, 1978). These extinction protocol are described as sensory extinction.

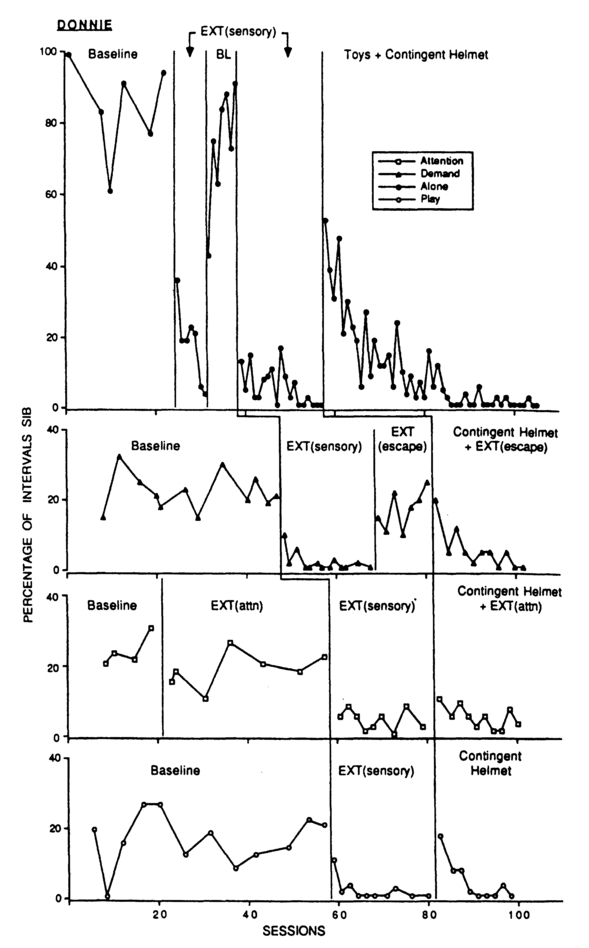

Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, and Miltenburger (1994) examined the influence of various extinction protocol on SIB (head hitting) that was maintained by automatic reinforcement for a boy with severe developmental disabilities. The results of this intervention are presented in Figure 10.7. A functional analysis initially demonstrated undifferentiated levels of SIB across attention, alone, play, and demand analogue analysis conditions (see the four baseline data sets in the figure). These analogue analysis results allowed for the conclusion that the behavior was maintained by automatic reinforcement. The effects of sensory extinction was then examined in the alone condition (see first leg of the graph). Sensory extinction was achieved by placing a padded seizure helmet on the boy for the entire length of the session or contingent upon episodes of SIB in a session. The sensory extinction protocol produced dramatic reductions in SIB. Next, the sensory extinction protocol were compared with an escape extinction protocol (see second leg of the design). Again sensory extinction produced reductions in SIB but escape extinction had no effect on responding. The sensory extinction protocol was then compared with planned ignoring of SIB (see third leg of the design). Ignoring SIB produced no effect whereas sensory extinction reduced SIB. These results are a rigorous demonstration of the

Figure 10.7 Percentage of intervals of SIB maintained by sensory consequences. Various hypothesized maintaining variables were removed (sensory extinction in panel 1, escape extinction in panel 2, and planned ignoring in panel 3 of the graph). The behavior decreased only in the sensory extinction condition (Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994).

importance of matching extinction interventions to the function of the behavior. In this study the extinction strategies that were designed to eliminate behavior maintained by social negative reinforcement (i.e., escape extinction) and social positive reinforcement (i.e., ignoring) had no effect on the target behavior. The behavior only decreased under the sensory extinction (i.e., padded helmet) condition.

Extinction is a process whereby the contingency between responding and reinforcement is broken. The ultimate outcome of this process is an elimination of the behavior. Extinction can be accomplished by removing the reinforcer or by delivering the reinforcer on a noncontingent basis. For extinction to be effective the behavior analyst must first identify the maintaining contingencies via a functional analysis. Extinction interventions vary depending on the function of the behavior to be extinguished. For example, behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement is placed on extinction by removing social reinforcement contingent upon performance of the behavior. Alternatively, behavior maintained by negative reinforcement is placed on extinction by eliminating escape contingent on performance of the behavior. There are many properties of the extinction process, such as extinction bursts, extinction-induced aggression, gradual reductions in behavior, and spontaneous recovery that the behavior analyst should consider prior to using extinction in an applied setting. Those who will implement the extinction program must be prepared for such issues as potential increases in the intensity of the behavior or the reemergence of the behavior at later points in time. If there is any concern that those who are targeted to implement the program may not be capable of doing so over extended periods of time, or if very rapid behavior change is required, then alternative intervention strategies should be considered.

in Chapter 5 we outlined the basic properties of punishment as demonstrated by experimental research. In this section of the current chapter we will examine the use of punishment in applied settings. Punishment can be defined as the application or removal of a stimulus contingent on responding that decreases the probability of responding. As discussed in Chapter 5, it is important to remember that punishment is defined functionally in terms of changes in responding. Punishment in behavioral analysis is therefore very different from the way the term is used in everyday language, in everyday use punishment is typically equated with an aversive consequence for engaging or not engaging in an activity. For example, a student may be expelled from school for fighting, or a person may be fined or imprisoned for driving a car without insurance. The everyday use of the term punishment is therefore not defined in terms of its influence on responding. An aversive consequence is usually equated with causing some form of hurt or pain to the individual. In behavioral analysis a punishing stimulus does not necessarily have to cause pain. In fact, in some cases a painful stimulus can act as a reinforcer. For example, a spanking may increase and not decrease behavior. In this situation spanking would be defined as a reinforcing and not as a punishing consequence.

Painful stimuli as well as stimuli that do not cause physical discomfort can act as punishers in the behavioral sense and are sometimes used by behavior analysts to decrease aberrant behavior. It is important to recognize that punishment protocol should be the interventions of last resort for the behavior analyst. Punishment procedures should only be used in cases where less intrusive and positive alternatives (e.g., differential reinforcement strategies, functional equivalence training etc.) have been considered or tried and have failed to reduce the behavior. Additionally, it would be difficult to justify the use of many types of punishment techniques described below with behavior other than that which is dangerous to self or others (e.g. self-injurious or aggressive behavior). Punishment techniques should only be used in the context of an intensive intervention to increase appropriate alternative behaviors for an individual. As evidence of the importance and controversy surrounding the use of punishment techniques the National Institutes of Health (NIH) convened a consensus development conference to discuss the use of such techniques. This conference concluded that

"Behavior reductive procedures should be selected for their rapid effectiveness only if the exigencies of the clinical situation require such restrictive interventions and only after appropriate review. These interventions should only be used in the context of a comprehensive and individualized behavior enhancement treatment package." (NIH, 1989, p. 13)

Today, punishment is often described as a form of default technology by behavior analysts (e.g., Iwata, 1994). In other words, punishment is the treatment of last resort and it is typically used only in cases where the function of the aberrant behavior has not been identified. In cases where a functional analysis can identify the maintaining contingencies for aberrant behavior then an intervention other than punishment may be most appropriate to eliminate the behavior. In situations where the maintaining consequences are identified the behavior analyst can withhold these consequences when aberrant behavior occurs and deliver the consequences contingent on appropriate alternative behavior, if maintaining contingencies for aberrant behavior cannot be identified through a functional analysis then it becomes impossible to withhold reinforcement contingent on aberrant responding. One treatment option may then be to override the maintaining reinforcement contingencies with a more powerful punishment contingency in order to eliminate aberrant responding. Again, punishment protocol should only be implemented in the context of a more general program to teach alternative appropriate responding to the individual.

Punishment techniques can be divided into three general categories: The presentation of aversive events contingent on responding, which is described in this section; the removal of positive events contingent on responding, which is described in Section 10.6; and finally, there are a variety of punishment techniques that require the client to engage in activities contingent on performance of the target behavior, and these techniques are described in Section 10.7. With all these techniques, the events used can only be defined as punishers if their contingent application reduce the probability of the target behavior.

Aversive events can be divided into unconditioned or conditioned aversive events. Unconditioned aversive events are stimuli that by their nature are aversive to humans. The aversive properties of such stimuli are unconditioned or unlearned. Examples of unconditioned aversive events include electric shock, the smell of amonia, and loud noise. Conditioned aversive events are stimuli that have acquired aversive properties through pairing or association with unconditioned aversive stimuli or other conditioned aversive stimuli. For example, the verbal reprimands of a parent (e.g., "No!") to a child may become aversive through pairing with spanking or loss of privileges (such as TV time). The use of unconditioned and conditioned aversive events to reduce or eliminate maladaptive behavior has been examined by behavior analysts.

Electric shock has been used as a punishment technique in a small number of cases. The shock itself is typically of a very mild form and is delivered to the arm or leg. Shock has usually been restricted to the treatment of behaviors that are severely maladaptive or life-threatening. Alternative and less intrusive interventions have typically been tried and have failed in such cases (Linscheid, Iwata, Ricketts, Williams, & Griffin, 1990). Shock has been particularly successful in cases where life-threatening behavior is resistant to other forms of therapy. In fact shock can typically produce an almost immediate suppression of the target behavior. For example, electric shock has been found to be quite effective in treating chronic rumination or vomiting in infants (Cunningham & Linscheid, 1976; Linscheid & Cunningham, 1977). This is a life-threatening condition that can result in severe weight-loss and dangerous medical complications. Linscheid and Cunningham (1977), used electric shock to treat chronic vomiting (episodes of vomiting occurred on average over 100 times per day) in a 9-month-old child. A mild shock was applied to the child's leg at the onset of each vomiting episode. Vomiting was virtually eliminated after 3 days of treatment. Episodes of vomiting did not occur for up to 9 months following treatment.

Other unconditioned aversive stimuli have been used to treat dangerous or life-threatening behavior. Peine, Liu, Blakelock, Jenson, and Osborne (1991) examined the use of contingent water misting to reduce self-choking in an adult with severe developmental disabilities. This man engaged in self-choking to the point of syncope. Self-choking consisted of squeezing the neck region with either hand or forcefully twisting an item such as a towel or shirt around the neck. He aggressed towards staff if they attempted to redirect his behavior. The water misting procedure consisted of spraying the man in the face contingent on self-choking. A spray bottle which delivered 0.5cc of water (at room temperature) per application was used. This treatment produced rapid reduction of self-choking (see Figure 10.8). Additionally, the experimenters measured generalization of the treatment gains across multiple settings in the institution. As can be seen in Figure 10.8, the water misting procedure resulted in an elimination of self-choking across these settings. These treatment gains were maintained for up to 8 months as seen in the follow-up assessment phase of the figure.

Figure 10.8 Rates of self-choking by a deaf-blind man with mental retardation before and during water mist treatment and its generalization and follow-up. The numbers in the generalization phases indicate different settings (Peine, Liu, Blakelock, Jenson, & Osborne, 1991).

One of the most frequently cited conditioned aversive stimuli used to reduce aberrant behavior is that of verbal reprimands (Kazdin, 1994), As mentioned earlier, verbal reprimands can become aversive stimuli through pairing with other conditioned or unconditioned aversive stimuli. Verbal reprimands do not necessarily act as aversive stimuli with all individuals or with the same individual in every context. In some instances verbal reprimands may act as reinforcers. For example, Iwata et al. (1994) demonstrated that contingent attention in the form of verbal reprimands can serve as a consequence that maintains aberrant behavior with many people with developmental disabilities. Whether verbal reprimands will act as reinforcing or punishing stimuli depends on the learning history of the individual.

When they do function as aversive stimuli, verbal reprimands can be an easy to implement and relatively benign way of reducing aberrant behavior. It is important to realize that verbal reprimands, as used by behavior analysts, do not include hurtful statements or statements that ridicule. Verbal reprimands typically consist of telling an individual not to engage in a particular form of aberrant behavior. Additionally the individual is informed of the negative consequences for engaging in such behavior.

For example, Rolider and Van Houten (1984) examined the use of verbal reprimands to reduce the aggressive behavior (hitting, pinching etc.) of a 4-year-old girl towards a younger sibling (see Figure 10.9). An initial DRO procedure which consisted of positive physical attention (hugs and kisses from the mother) for every 15 minutes without aggressive behavior did not produce a reduction in aggressive behavior below the baseline assessment condition (see the figure). Finally, a DRO plus verbal reprimand intervention was implemented. The verbal reprimand condition consisted of holding the child by the shoulders, making eye contact, then telling the girl that she was hurting her sibling and that she was not to do this again. The DRO plus verbal reprimand intervention virtually eliminated aggressive behavior in the girl (see the final phase of the figure).

Figure 10.9 Frequency of aggressive behavior of a young girl towards her younger sibling under Baseline, DRO, and DRO plus verbal reprimand conditions. (Rolider & Van Houten, 1984).

The individual delivering verbal reprimands is usually in close physical proximity, maintains eye contact with, and often physically holds the person being reprimanded. In fact verbal reprimands have been shown to be more effective in reducing behavior if they are delivered with these additional behaviors (Doleys, Wells, Hobbs, Roberts, & Cartelli, 1976; Van Houten, Nau, MacKenzie-Keating, Sameoto, & Colavecchia, 1982).

Aversive consequences, when made contingent upon performance of aberrant behavior, can rapidly reduce that behavior. Aversive consequences can be either unconditioned (i.e., inherently aversive) or conditioned (i.e., learned) stimuli. Unconditioned aversive stimuli such as water misting or electric shock have been demonstrated to produce rapid and long lasting reductions with very severe behavior problems. When using conditioned aversive stimuli such as verbal reprimands it is important to establish that such stimuli are in fact aversive for the client concerned. Under those rare and extreme situations where aversive stimuli are selected for use they should be embedded within a more general behavioral program to increase adaptive responding in the client.

The removal of positive events contingent on responding can also be used to decrease maladaptive behavior. Two general techniques have typically been used by behavior analysts to remove positive events contingent on maladaptive responding. These techniques are called time out from positive reinforcement and response cost.

Time out from positive reinforcement consists of a series of protocols whereby the person is removed from all positively reinforcing events for a brief period of time. Time out can be either exclusionary or nonexclusionary. With exclusionary time out the person is removed from the current environment where the maladaptive behavior is occurring and placed in a barren room (usually termed a time out room) where no reinforcing items are available for a brief time period. Exclusionary time out is a particularly useful method with maladaptive behaviors such as tantrums and aggression as such behaviors can be disruptive to other individuals in the setting (for example, other students in a classroom). Once the brief time period has elapsed and the individual is observed not to be engaging in the aberrant behavior then they are allowed to return to the original activities. The person should not be released from time out when they are engaging in the targeted maladaptive behavior. Otherwise the time out procedure may in fact reinforce or strengthen the target behavior (i.e., the person may learn to associate escape from time out with the maladaptive behavior). Brief rather than extended time periods in time out should be used. Brief periods in time out seem to be as effective as extended time out periods in reducing maladaptive behavior (Kazdin, 1994). Additionally, extended time out periods may interfere with ongoing educational or rehabilitative programming for the person.

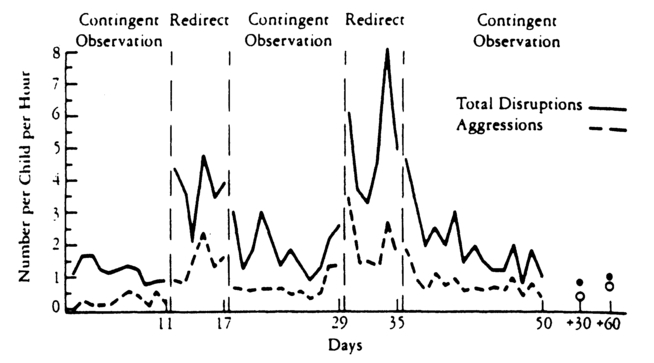

An alternative to exclusionary time out is non-exclusionary time out. In non-exclusionary time out the individual remains in the setting where the aberrant behavior occurs. But the person does not have access to reinforcers in this setting for a brief period of time. Non exclusionary time out is typically a more acceptable time out procedure to professionals and parents because the person is not placed in isolation for a period of time. Additionally, the person has the opportunity to continue to observe educational activities while they are in the time out condition. One frequently cited form of non-exclusionary time out is called contingent observation. Porterfield, Herbert-Jackson, and Risley (1976) used contingent observation to reduce disruptive behaviors such as aggression and tantrums in a preschool classroom. Once targeted maladaptive behaviors occurred, staff removed the child away from toys and other children to a corner of the classroom. The child was told to remain in the corner and observe the other children playing appropriately. Staff then returned to the child after one minute and asked the child if they were ready to return to the group. If the child was not engaged in the maladaptive behavior (e.g., tantrums) and indicated that they wanted to return to the group then they were allowed to play again. This contingent observation technique was compared with a redirection intervention on disruptive behaviors in the classroom (see Figure 10.10). The redirection intervention consisted of redirecting the child's attention to another activity (such as another toy) when they engaged in disruptive behavior. The results of both of these interventions, as shown in Figure 10.10, demonstrated that contingent observation was a more effective technique in reducing overall levels of disruption and aggression for this preschool class.

In some situations non-exclusionary time out may not be the procedure of choice as some persons may attempt to escape from time out and return to ongoing activities. In such situations exclusionary time out may be considered as a back-up procedure (i.e., if a person escapes from nonexclusionary time out then they may be placed in exclusionary time out). In order for any time out protocol to be maximally effective the person must have a rich "time in" environment. In other words the ongoing environment from which the person is removed should be highly reinforcing. The removal of reinforcers contingent on aberrant behavior to reduce that behavior can only occur if there are reinforcers in the person's environment. Again, this point highlights previous discussions in this and earlier chapters of the importance of using punishment programs only in the context of positive programming to teach adaptive skills to individuals.

Figure 10.10 Number of disruptions and aggressive behaviors per child per hour for 50 days in a day care center with follow-up at 1 and 2 months (Porterfield, Herbert-Jackson, & Risley, 1976).

In some cases, exclusionary and non-exclusionary time out will not be effective. This is particularly true for individuals whose aberrant behavior occurs independent of the social environment. For example, individuals with autism often engage in high rates of self-stimulatory behavior (e.g., hand flapping, body rocking) irrespective of the social environment. As such behavior seems to be automatically reinforced (i.e., the behavior produces its own reinforcement), time out does not remove the source of reinforcement. Rolider and Van Houten (1985) developed a form of time out technique, called movement suppression time out, which seems to be effective with such forms of automatically reinforced aberrant behavior. In one example these authors compared the effectiveness of movement suppression time out with a DRO intervention to reduce aberrant behavior in a 9-year-old boy who was diagnosed with autism. The boy engaged in arm biting which frequently broke the skin and mouthing inappropriate objects such as cloth and rocks which he sometimes swallowed. The DRO procedure consisted of reinforcing comments and hugs from his mother if he did not engage in these behaviors for 10 minutes. Movement suppression time out consisted of physically guiding the child to a corner of the room, positioning his chin against the corner of the wall with both hands behind his back and both feet together touching the wall. The child was not allowed to move for 3 minutes and was physically repositioned if he moved in any way. The results of the DRO and movement suppression time out interventions are displayed in Figure 10.11. As can be seen in the figure the DRO intervention had little effect on aberrant responding. The movement suppression procedure resulted in rapid elimination of both arm biting and mouthing. Movement suppression time out was implemented for an extended period of time (see the follow up phase of Figure 10.11) and aberrant behavior was eliminated during this period.

Figure 10.11 Number of arm bites (top panel) and mouthing incidents (bottom panel) under Baseline, DRO Alone, and Movement Suppression Time-Out. Followup observations on the target behaviors are also presented (Rolider & Van Houten, 1985).

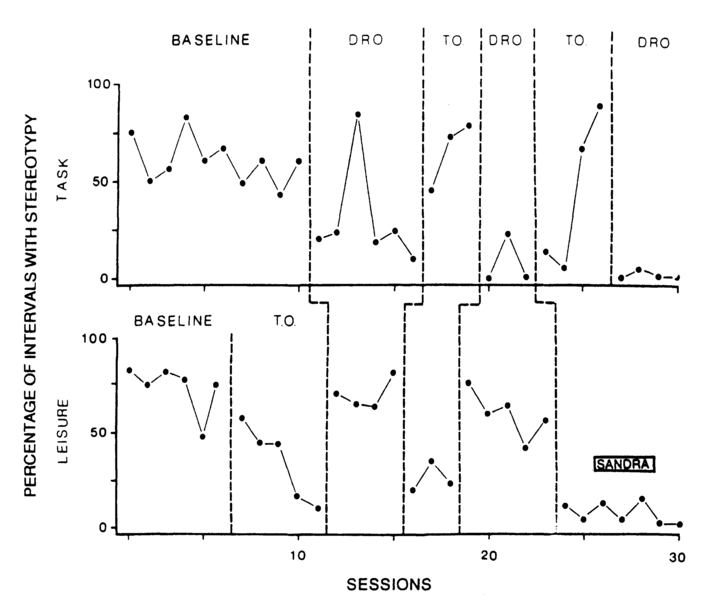

The effects of time out procedures may be determined by the context in which they are implemented. Under certain ongoing conditions which a person may find aversive a time out procedure may in fact reinforce maladaptive behavior because it allows the individual to escape from these ongoing events. Under such conditions a time out procedure will result in increases in maladaptive responding. Alternatively, during ongoing activities which the same person finds to be positive, the same time out procedure may act as a punisher. In this second condition the time out procedure will result in decreases in maladaptive responding. Haring and Kennedy (1990) demonstrated this influence of context on the effectiveness of time out protocol with a number of individuals. The effects of time out on aberrant responding under task and leisure conditions for one individual with developmental disabilities are displayed in Figure 10.12. The contextual influences on DRO protocol were also examined with this individual but will not be addressed in this discussion. The task condition involved identifying common items such as money and various foods

Figure 10.12 Percentage of intervals with stereotypy across Baseline, DRO, and Time-Out conditions in task (top panel) and leisure (bottom panel) contexts (Haring, & Kennedy, 1990).

during teaching trials. The leisure condition involved listening to the radio. The maladaptive behavior exhibited by this individual consisted of stereotyped responding. Time out under the task condition involved removing instruction contingent on stereotyped responding for a period of 15 seconds. Time out under the leisure condition consisted of removing the leisure items (turning the radio off) contingent on stereotyped behavior for a period of 15 seconds. The time out conditions under the task and leisure contexts were structurally identical (i.e., removal of items contingent on maladaptive behavior for 15 seconds). However, as can be seen in Figure 10.12, the time out intervention served a different function within the task and leisure contexts. Time out resulted in increases in stereotypy under the task condition and decreases in stereotypy in the leisure condition.

Response cost is another punishment technique which involves the removal of positive events or stimuli contingent on responding. We noted in Chapter 5 that this type of punishment can be shown to have reliable and orderly effects in experiments with adult humans. In applied contexts, response cost is a form of penalty that is imposed on the individual for engaging in a particular maladaptive behavior. This type of technique is readily recognizable to the general public (e.g., fines for late payment of domestic charges or for parking a car inappropriately etc.) and is viewed as an acceptable method to reduce maladaptive behaviors (Grant & Evans, 1994). Response cost differs from time out protocols in a number of ways. With response cost the reinforcer may be permanently withdrawn (as when somebody is fined for a traffic violation). In time out the reinforcers are withdrawn for a brief period of time. Additionally, with time out, all opportunities for reinforcement are removed for a period of time. Aside from a penalty, all other positive events continue to be available with a response cost intervention.

Response cost protocols are often used as part of a token economy system. In fact token economy systems that incorporate response cost components are more effective than either procedure if used alone (Bierman, Miller, & Stabb, 1987). Upper (1973) incorporated a response cost system as part of a token economy to increase adaptive responding of psychiatric patients in a hospital ward. Patients were fined for such behaviors as sleeping late, public undressing, and aggressive outbursts. The response cost protocol, when incorporated into the token economy system, resulted in dramatic reductions of these aberrant behaviors.

In many situations response cost procedures can be implemented alone. Rapport, Murphy and Bailey (1982) used a response cost system to decrease classroom disruption in two school children who were diagnosed with hyperactivity. For each episode of disruptive or inattentive behavior the child would lose 1 minute from their break time period. The contingent removal of time from break for disruptive behavior not only decreased aberrant behavior but also resulted in increases in academic performance.

A number of behavioral techniques are designed to punish maladaptive behavior by removing positive stimuli contingent on responding. Time out from positive reinforcement describes a set of techniques which are designed to remove all positive consequences contingent on maladaptive responding for a brief period of time. Time out protocol can be exclusionary (where the person is removed from the environment) or non-exclusionary (where positive items are removed but the person remains in the environment where the maladaptive behavior occurred). Movement suppression time out is a recent technique designed to reduce maladaptive behavior such as some forms of stereotypy which are sometimes automatically reinforced. Alternatively, response cost procedures involve a penalty whereby some item (such as tokens) are permanently removed contingent on maladaptive behavior.

Overall, these procedures are more acceptable to the general public — that is they have greater social validity (see Chapter 5) — than the use of aversive consequences to reduce aberrant behavior. Time out procedures are generally effective if the person is removed from ongoing activities for a brief period of time (i.e., typically not more than several minutes). The person should not be allowed to escape from time out if they continue to engage in the aberrant behavior at the end of the time period, instead the behavior analyst should wait until they desist in aberrant behavior and then release them from time out. If aberrant responding persists for extended time periods under time out conditions then alternative interventions should be considered. Time out is only effective as a punisher if the person is removed from activities that they find to be reinforcing. Time out may actually act as a reinforcer if the person is removed from ongoing aversive activities. Response cost procedures are often used within the context of a token economy system. Token economies which incorporate a response cost component are typically more effective than token economies which do not. Response cost procedures, when implemented alone, can also be very effective in reducing behavior.

A variety of punishment procedures employ the performance of activities contingent on maladaptive behavior. In other words the person must perform aversive activities after they engage in the targeted aberrant behavior. One of the most frequently described activity punishers is that of overcorrection (Foxx & Azrin, 1972; Foxx & Bechtel, 1983). Overcorrection typically consists of two components: restitution and positive practice. Initially the individual is required to restore any items in the environment that have been damaged as a result of the maladaptive behavior. For example, if an individual engaged in an aggressive outburst and overturned a chair then the individual would be required to replace the chair in its original position. The positive practice component involves repeated practice of a behavior that is an appropriate alternative to the maladaptive behavior. To continue with the overturned chair example, the individual might then be required to straighten all chairs in the room. In many situations the difference between restoring the environment and practicing appropriate alternative behaviors may be unclear, in the above exaimple the restitution component (i.e., replacing the thrown chair) is in a sense a form of positive practice. Suffice it to say that overcorrection involves restoring the environment following the maladaptive behavior and then practicing appropriate alternative behaviors.

Merely restoring the environment (sometimes called simple correction) does not seem to act as a punisher when used without positive practice. For example, Azrin and Wesolowski (1974) compared a simple correction protocol with an overcorrection protocol to reduce theft among people with developmental disabilities in an institutional setting, in the simple correction condition the person was required to return the item that was stolen. As can be seen in Figure 10.13, this simple correction procedure did not eliminate theft in the setting. A positive practice component was then combined with the simple correction protocol. Positive practice involved purchasing an item similar to the stolen item and giving the purchased item to the victim. The simple correction procedure combined with positive practice (this is described as a theft reversal intervention in Figure 10.13) resulted in the elimination of stealing among the 34 individuals in the institutional setting. Other research has also demonstrated that restitution plus positive practice is more effective than restitution alone in reducing maladaptive behavior (e.g., Carey & Bucher, 1981).

Figure 10.13 Number of stealing episodes each day for a group of 34 persons with developmental disabilities in an institutional setting. Frequent stealing occurred under the simple correction procedure (person was to return the stolen item). Stealing was eliminated in the overcorrection (theft reversal) phase (person returned the stolen item and gave the victim a further item of equal value) (Azrin & Wesolowski, 1974).

In many cases the maladaptive behavior may not actually involve disruption or damage to the environment. For example, if a child engages in self-stimulatory behavior (such as hand flapping or body rocking) then little in the environment is altered. In such cases positive practice alone can be used. Contingent on the maladaptive behavior the child would be required to practice alternative appropriate behaviors. For example, Azrin and Powers (1975) required students who spoke out without permission in class to practice raising their hands and waiting for the teacher's permission to speak. Positive practice trials were conducted in the classroom during recess periods. The intervention markedly reduced classroom disruption with these children.

Overcorrection procedures may have some advantages over the other punishment protocol described thus far in this chapter (i.e., contingent presentation of aversive stimuli and contingent removal of positive events). The positive practice component of overcorrection protocol allows the individual to practice appropriate alternative behaviors. Overcorrection can therefore serve an educative as well as a punishing role. It also allows the therapist to focus on alternative appropriate behaviors rather than only focusing on reducing maladaptive responses. In some instances, however, overcorrection procedures may be difficult to implement. For example, if the individual is unwilling to follow through with restitution and positive practice the therapist may have to physically guide the person through the tasks. This may be particularly problematic with adults who may aggress in such situations. Also, implementing overcorrection protocol can be intensive and time consuming for the therapist. It would be difficult for a therapist to implement overcorrection protocol correctly in a situation where the therapist is simultaneously responsible for the supervision of other individuals.

Contingent exercise is another form of activity punisher that has been used to reduce maladaptive behavior. The individual is required to engage in some form of physical exercise following the targeted behavior. Contingent exercise differs from overcorrection in that the individual is not required to restore the environment nor is the individual required to practice appropriate alternative behaviors. Luce, Delquadri, and Hall (1980) used contingent exercise to reduce the aggression and disruption of two emotionally disturbed boys in a special education setting. Hitting other children was targeted for one child. The child was required to stand up and sit down on the floor 10 times contingent upon hitting another child. This brief contingent exercise markedly reduced the amount of hitting in the class (see Figure 10.14).

Activity punishers are typically described in terms of two general techniques: overcorrection and contingent exercise. With overcorrection the individual must restore any damage to the environment caused by the aberrant behavior and repeatedly practice appropriate alternative behaviors. Overcorrection is often viewed as a more acceptable punishment procedure than the contingent use of aversive stimuli because it includes an educative component (i.e., the person is required to perform appropriate alternative behaviors to the aberrant behaviors). Positive practice can be used effectively without restitution in situations where the aberrant behavior does not result in damage to the environment. Overcorrection may be difficult to implement in situations where the behavior analyst is required to supervise many individuals simultaneously. Additionally, overcorrection may not be the treatment of choice with individuals (especially adults) who are noncompliant and who may aggress to avoid such activity. Several studies have examined the use of contingent exercise as a punishment technique. While contingent exercise can reduce aberrant responding it does not include an educative component. As with overcorrection, contingent exercise may be difficult to implement when supervising groups and in cases where the individual may be noncompliant with regard to engaging in the exercise regimen.

Figure 10.14 Number of hits per day during school period. During Baseline the hitting was ignored and no consequences were delivered. During the Contingent Exercise condition the child had to engage in stand up and sit down on the floor exercise contingent upon hitting (Luce, Delquadri, & Hall, 1980).

Punishment protocol should be considered the intervention of last resort. As mentioned earlier, these techniques are best reserved for the treatment of behavior that is of danger to the person or others. Punishment is usually considered in situations where other less intrusive interventions (e.g., differential reinforcement strategies) have been tried and have failed to reduce maladaptive responding. Punishment interventions are not typically used in isolation but are combined with interventions to increase appropriate alternative behaviors, in addition to a knowledge of the various punishment techniques described in the previous sections, the behavior analyst should be aware of some of the advantages and disadvantages of using punishment protocols.

One of the major advantages of using punishment is that it can produce an almost immediate reduction or elimination of the maladaptive response. This is particularly true with unconditioned aversive stimuli such as electric shock (Linscheid, et al., 1990). In cases where unconditioned aversive stimuli are used the reduction in aberrant responding is often quite dramatic and the treatment gains generally last for extended periods of time after the intervention is removed. This effect on responding is generally true for the other types of punishment protocol described in this chapter. Aberrant behavior may however re-emerge following the removal of some punishment techniques. If punishment protocol do not produce the desired reduction in responding following several applications then alternative protocol should be considered. It is not appropriate to expose an individual to extended periods of aversive contingencies if these contingencies do not have the desired functional effect.

In addition to eliminating aberrant responding, punishment protocol may also result in positive side effects. For example, Rolider, Cumrnings, and Van Houten (1991) evaluated the effects of punishment on eye contact and academic performance for two individuals with developmental disabilities. Both individuals engaged in aggression and other forms of escape behavior during academic instruction. Punishment protocol used in this study included a form of restraint or movement suppression time out and contingent exercise. The effects of punishment on academic achievement and eye contact was evaluated across therapists — with one therapist delivering punishment during instructional trials while the other therapist did not. The results demonstrated greater levels of academic achievement and increased levels of eye contact during instructional trials with the therapist who delivered the punishment protocol. Matson and Taras (1989) provided an extensive review of the positive side effects which have been documented when using punishment protocol. For example, some of the positive side effects of electric shock to treat rumination have included weight gain, increased social behavior, decreased crying and tantrums, improved self-feeding, and overall increases in activity levels.

There are also several disadvantages associated with using punishment techniques in applied settings, many of which have already been alluded to in this chapter. The use of punishment techniques with humans, especially individuals with developmental disabilities who may be unable to give informed consent, has been the source of much public controversy in the last decade. Many parent support groups (e.g., The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps) have taken stances against the use of punishment. Indeed several States in the United States have banned the use of punishment protocol in treatment. Much of this debate has been infused by a lack of understanding of the technical meaning of the term punishment in behavior analysis. Many of the position statements from non behavioral interest groups equate punishment with the more everyday usages of the term. Punishment is sometimes equated with such notions as cruelty, revenge, harm etc. While these debates may be devisive at times they do highlight the need to use punishment as a treatment of last resort, with very clear guidelines for its use, and within the context of a more general behavioral program to teach adaptive skills to the person. In the next and final chapter, we will relate these issues to the human rights of individuals in treatment.

Punishment procedures can also produce negative side effects. Many of these negative side effects have been reported with almost all types of punishment protocol. Emotional side effects include such behaviors as crying, tantrums, soiling, wetting, and general agitation. Many of these negative side effects occur when punishment protocol are first implemented and tend to decrease as the intervention is continued. It is important to note that these emotional side effects have been reported relatively infrequently in the literature. Interestingly, it is also commonly observed that in experimental studies with nonhuman animals, punishment does not persistent produce those behaviors classified as emotional.

Punishment has also been demonstrated to produce avoidance behavior in applied settings. Morris and Redd (1975) examined avoidance behavior in nursery school children. These children were supervised by men who (a) praised on-task behavior; (b) reprimanded off-task behavior; (c) praised on-task behavior and reprimanded off-task behavior; (d) ignored the behavior of the children. Children engaged in higher levels of on-task behavior with the men who reprimanded or who praised and reprimanded. When asked about which of the men they would like to play with the children chose the man who praised on-task behavior. The man who used reprimands only was ranked as the least preferred play companion. These results may highlight a more general problem with using punishment protocols in applied settings. Various neutral stimuli in an applied setting may become conditioned aversive stimuli through pairing with aversive protocols. The use of punishment with an individual could therefore result in many aspects of an environment such as a school setting becoming aversive for that individual. As we noted in Chapter 5, this would be predicted from a theoretical consideration of the effects of using aversive stimuli.

Relatedly, and as mentioned throughout this section on punishment, an individual may aggress towards the therapist in order to escape from a punishment protocol. This may be particularly problematic with adults as it may be difficult for the therapist to control aggressive outbursts while implementing a treatment. In such situations the therapist may unwittingly reinforce escape-maintained aggression if the individual is allowed to escape from treatment. Alternative treatments to punishment should obviously be considered in such situations.

When a therapist, parent, or other care provider uses punishment they are in effect providing examples of how to control another individual's behavior. Those who observe such practices can learn that such techniques can be used to control the behavior of others. The effects of what is often called modeled punishment have been extensively described in the literature (Kazdin, 1987). Children who are referred to clinicians for severe aggression usually come from homes where physical aggression is used by parents to control their children, in such home environments children learn that physical aggression is an acceptable and powerful tool for controlling the behavior of others.

It was mentioned earlier that one of the major advantages of punishment techniques is that they can produce rapid elimination of the maladaptive behavior. However, the maladaptive behavior can recover once these techniques are withdrawn. Recovery seems to occur under conditions where the behavior has not been completely eliminated during the punishment intervention. Additionally, conditioned punishers may lose their effectiveness over time which can result in a return of the target behavior to baseline levels. Such recovery following the removal of punishment may be overcome if punishment of the undesired response is embedded within a more general behavioral program to teach alternative appropriate behaviors.

The use of applied behavioral procedures based on the principles of extinction and punishment were described in this chapter. Punishment and extinction describe processes which result in a reduction or elimination of behavior. With extinction the contingency between the reinforcer and response is removed. Punishment involves the application or removal of a stimulus contingent on the performance of the target behavior. Prior to using extinction and punishment it is important that the behavior analyst establish a firm rationale for reducing targeted behaviors (see Chapter 7). The use of some of these strategies, particularly the use of aversive stimuli as punishers, should be considered the treatment of last resort and administered under strict guidelines. Typically, extinction and punishment protocols are used to eliminate aberrant behavior in the context of an intervention to increase appropriate alternative behaviors for the person.

There are certain characteristics of responding when behavior is punished or placed on extinction. For example, one can expect an initial increase in responding when a behavior is placed on extinction (i.e., an extinction burst). Additionally, behavior may re-emerge under extinction contingencies (i.e., spontaneous recovery). Punishment and extinction contingencies can also result in avoidance and aggressive behavior on the part of the client. It is important that those who administer extinction or punishment protocols be familiar with such characteristics in order to implement such protocols efficiently and effectively.

Extinction of responding can be accomplished by removing the reinforcer entirely (i.e., reinforcement is no longer available) or delivering the reinforcer noncontingently on a fixed-time schedule. In both cases the contingency between responding and reinforcement is removed. Noncontingent delivery of reinforcing stimuli has been examined relatively recently in the applied literature and seems to produce rapid reductions in responding without creating ethical problems that can arise when access to highly-preferred reinforcers is removed.

It is vital that the reinforcement contingencies are identified before any extinction protocol can be implemented. In fact an extinction protocol should be determined by the function of the behavior to be extinguished. Extinction protocols will differ depending on whether the behavior is maintained by social positive reinforcement, social negative reinforcement, or automatic reinforcement.

There are three general categories of punishment protocols. One class of punishment techniques involves the presentation of aversive stimuli contingent on the performance of the behavior targeted for reduction. These aversive stimuli can either be unconditioned (e.g., electric shock) or conditioned (e.g., verbal reprimand). A second class of punishment protocol involves the removal of positive events contingent on performance of the targeted behavior. In time out from positive reinforcement, the individual is removed from ail reinforcing events for a predetermined period of time. Response cost protocols involve the permanent removal of some item or event in the form of a penalty or fine contingent on maladaptive responding. A final class of punishment techniques requires the client to engage in some form of activity contingent on the target behavior (such as overcorrection or contingent exercise).

There is much current debate about the use of punishment in therapy, particularly when it is used with individuals with developmental disabilities. Punishment is sometimes seen as being synonymous with abuse and cruelty. In behavioral analysis, however, punishment is defined functionally in terms of its influence on responding. Punishment protocols should only be used as a treatment of last resort for behavior that is dangerous to self or others.