Figure 5.1 A shuttle box designed to study avesive contingencies with rats. When the shutte raised, the rat can jump the hurdle and get into the other half of the apparatus.

The first step in our systematic account of operant behavior was the definition of simple operant conditioning. It was defined as the presentation of a response-contingent stimulus, which produced a number of characteristic response changes that included an increase in response frequency. We called the stimulus in that paradigm a positive reinforcer and, to this point, have generally restricted the account of operant behavior to those situations involving such positive reinforcement.

Only casual observation is needed, however, to detect the operation of another kind of reinforcement, defined by the operant conditioning that occurs through the response-contingent removal of certain environmental events. We see that birds find shelter during rainstorms, dogs move to shady spots when the summer sun beats down upon them, and people close windows when the roar of traffic is loud. In these instances behavior is emitted that removes or terminates some environmental event: rain, heat or light, and noise, in the examples given. These observations suggest the existence of a distinctive class of reinforcing events. Because the operation that defines these events as reinforcing is their removal, and is opposite in character to that of positive reinforcers (defined by their presentation), they are known as negative reinforcers (S–). In general, negative reinforcers constitute those events whose removal, termination, or reduction in intensity, will increase or maintain the frequency of operant behavior.

In this chapter, we shall describe two important experimental paradigms, escape and avoidance, as procedures with a characteristic outcome. In these procedures, negative reinforcers (aversive stimuli) operate as the special response-contingent stimuli that are used in characteristic ways to produce the outcome characteristic of each procedure. A third procedure which also involves aversive stimuli and has a characteristic outcome, is punishment. This involves the response-contingent presentation of an aversive event, and has the characteristic outcome that the frequency of the operant response is reduced by this contingency. Finally, we shall consider classical conditioning procedures where the US has aversive properties. In parallel with what we have found in our consideration of positive operant reinforcement and classical conditioning with appetitive US's, there are similarities in the outcomes of operant conditioning procedures involving aversive stimuli and aversive classical conditioning. Throughout this chapter, we shall, as in earlier chapters, seek to identify basic processes of operant and classical conditioning, to describe their action and interaction in particular situations. Here and in later chapters we seek to demonstrate the applicability of these behavioral processes isolated in the laboratory to significant issues in human life. Unlike positive reinforcement, the use of aversive contingencies is strongly linked to ethical concerns. Some of these will be introduced in this chapter, and we will return to them when considering the management of human behavioral problems in detail in later chapters.

In the laboratory, aversive stimuli have typically taken the form of electric shocks, prolonged immersion in water, and high intensities of light, sound, or temperature. These are the events that, in common parlance, we call "annoying", "uncomfortable", "painful", "unpleasant", "noxious", and "aversive". Of these terms, we shall use the word "aversive" as a technical synonym for negative reinforcement.

Aversiveness suggests the key notion of "averting", "moving away from", or "escaping from" a situation. We may reasonably expect to find that the acquisition of behavior that leads to escape from (or termination of) an aversive stimulus is a fundamental behavioral process. After all, if an organism is not equipped to escape from potentially physically damaging stimuli, its survival is endangered, it is thus likely that evolution will have equipped most species with the capacity to learn through escape contingencies.

We need a clear definition of escape in order to distinguish it from other aversive procedures that will be introduced later, in the escape procedure, a stimulus is presented and termination of that stimulus is contingent upon the occurrence of a specified operant response. If this contingency results in an increase in frequency of the response, and in the other associated behavioral changes described for positive reinforcement in Chapter 2, then escape learning has occurred. We can also conclude that the stimulus presented is an aversive stimulus, which is acting as a negative reinforcer for the response specified because its termination is the crucial event.

We can represent the escape procedure symbolically by the following three-term relationship:

S-: R1 → S°

R1 = specified operant response

S° = absence of aversive stimulus

Note the following important points:

Typically, an experiment involves a number of escape trials, each terminating after a correct response or a fixed period of exposure to the aversive stimulus, separated by intertrial intervals in which no stimuli are presented.

Various simple procedures have been used for experimental studies of escape training. In an early study by Muenzinger and Fletcher (1936), a rat was placed in a T-shaped maze that contained an electrically charged grid floor. The floor was wired so that as long as the animal remained on the grid, a continuous shock was administered to its paws. A cover over the maze prevented the rat from escaping the shock by jumping out of the apparatus. One escape route remained; the animal could find safety by running consistently to a designated arm of the T.

Behavior in the T-maze is usually measured on each trial by timing the rat from start to safe, or by counting the "incorrect" turns ("errors") into the unsafe arm of the T. On early trials, the rat is equally likely to run right or left, but as acquisition of the response of turning to the safe side proceeds, responses to the "incorrect" side decrease.

More recent studies of escape have generally used apparatus in which a long series of trials (S– presentations) can be presented at appropriate intervals without the participant having to be removed. In the Skinner box, for example, lever presses can be arranged to terminate electric shocks coming from the grid floor. But the most common apparatus for the study of escape conditioning has been the shuttle box of Figure 5.1. This box is simply a two-compartment chamber, where the measured operant response is movement from one chamber to the other (usually movement in either direction counts as a response). Movement is detected by spring switches under the floor, or by photocells. The aversive stimulus (S–) is usually pulsed electric shock delivered through the grid floor. Escape behavior is rapidly acquired in this apparatus, possibly because the required operant response (running) is closely related to the unconditioned behavior elicited by the shock.

Figure 5.1 A shuttle box designed to study avesive contingencies with rats. When the shutte raised, the rat can jump the hurdle and get into the other half of the apparatus.

Many experimental studies have employed rats as participants and electric shock as the S–. These choices were made because it is relatively easy to deliver a controlled shock to a rat through the grid on which it is standing. Other stimuli (for example, noise or blasts of air) are less easy to control, and other species present a variety of methodological problems. These biases of experimenters towards using methods that are convenient are understandable, but have not been based on much knowledge as to how representative the situation studied is of escape learning in general, so we must be ready to expect some surprises when the escape paradigm is used with other species and other stimuli.

However, it has been possible to demonstrate some generality of the effects of various different procedures for escape training. Results for rats which learned to press a lever which turned off electric shocks intermittently delivered through the grid floor appear in Figure 5.2A, while Figures 5.2B and 5.2C document the results of similar experiments with other aversive agents. Figure 5.2B illustrates the effects of increasing the intensity of a sound on VI lever-pressing escape rate of cats. The results of Figure 5.2C were obtained from a group of rats whose pushing of a panel on Fl contingencies terminated lights of various intensities. Both the (B) and (C) panels of Figure 5.2 demonstrate that escape behavior may reach a maximum rate and then decline if the aversive-stimulus intensity is made very great. The decline in responding associated with very intense aversive events is not well understood, but is thought to be due to a general suppressive (emotional) effect of strong aversive stimuli. This "side-effect" will be discussed later.

Figure 5.2 Escape response rates as function of the intensity of three different aversive stimuli. A Dinsmoor and Winograd, 1958; B Barry and Harrison, 1957 C Kaplan, 1952.

Since we are interested in possible parallels between negative and positive reinforcement, we may ask to what variable in the field of positive reinforcement does aversive stimulus intensity correspond? Superficially, the intensity of a negative reinforcer seems analogous to the magnitude of a positive reinforcer. Intensity of S– and magnitude of S+ are both stimulus properties of the reinforcer, and increases in both variables can generate increases in responding in some procedures. However, closer analysis of the functional role that these two variables play in negative and positive reinforcement, respectively, suggests that the analogy is only superficial. The principal effect of raising the intensity of a light, or a sound, or a shock, from a low to a high value, is that the reinforcement of behavior is made possible through termination of the new intensity. Increasing the intensity of an S– has, therefore, the effect of a reinforcement-establishing operation. Thus, in the presence of a weak intensity of light, or noise, a rat will not show conditioning of a response that terminates the light or noise. Similarly, with a small value of food deprivation, a response that produces food will not be strengthened. Conversely, high values of both shock intensity and food deprivation make it possible to use shock termination and food presentation as reinforcers for operant behavior. Thus, shock intensity is better described as a motivational variable, than as a reinforcement magnitude variable.

Ethical concerns have limited the number of experiments on escape behavior with human participants (but see Chapter 7 for some examples of where assessment of escape-motivated behavior requires repeated presentation of aversive stimuli). That is, we are reluctant to carry out, or sanction others carrying out, experiments which necessarily involve people being presented with aversive events. Our concern is perfectly reasonable — as is concern with the ethics of carrying out experiments with nonhuman animals that involve aversive stimuli — but it can be argued that it is misplaced because escape behavior is very important in humans as in other species. Consequently, our general scientific curiosity should be aroused, and, more importantly, a better knowledge of how it occurs in humans would enable us to devise intervention strategies for significant human problems. Let us consider the example of self-injurious behavior. This is a very distressing problem that greatly reduces the quality of life of a large number of people with learning difficulties. One way of conceptualizing this phenomenon would be as a failure of escape learning that normally occurs. For most of us, the pain of striking our head on a wall, for example, rapidly leads to a change in behavior and this is a form of escape learning. It may be that some people lack the capacity to readily learn in this way, or, more likely, that other escape contingencies (perhaps escape from social pressures) have a greater influence on their behavior. As with all forms of conditioning, we need basic research on escape procedures with human behavior, and comparative studies with other species, in order to understand the behavioral processes and to design effective interventions for serious behavioral problems.

Consider the escape paradigm applied to the example of someone walking in the rain:

This seems to be a clear case of escape behavior; putting up the umbrella is reinforced by escape from the rain. Consider, however, another behavioral element of this incident; the fact that the person was carrying an umbrella. Can we explain the "umbrella carrying response" in terms of an operant reinforcement contingency? It seems likely that umbrella-carrying on a showery day is reinforced by the avoidance of getting wet that would otherwise occur. We can thus state:

Note the differences between this three-term relationship and the one for escape. The discriminative stimulus (SD) for making the response is not now an aversive stimulus as well: it need not actually be raining when we leave the house for us to take an umbrella. Furthermore, the consequence of making the response is rather different. In the escape paradigm, S– offset occurs as soon as the response is made. In the avoidance paradigm, S– is prevented from occurring by the response.

In an avoidance procedure, a stimulus is programmed to occur unless a specified operant response occurs. Occurrence of that response cancels or postpones these stimulus presentations, if this contingency results in an increase in frequency of that response, then avoidance learning has occurred, and the stimulus has negative reinforcement properties for that response. Notice that the avoidance procedure supplements the escape paradigm in giving us a second, independent, way of discovering negative reinforcers, and thus defining aversive stimuli.

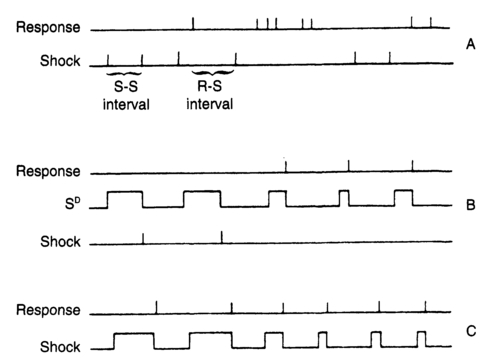

Representing avoidance diagrammatically is awkward, because the crucial element is the postponement or cancellation of an event which has not yet occurred. Figure 5.3 illustrates "timelines" for two types of avoidance schedule which have often been used in experimental studies. (The aversive stimuli are assumed to be electric shocks.) In free operant avoidance (Figure 5.3A), shocks occur at regular intervals, the shock (S-S) interval, unless an operant response occurs. If it does, the next shock is postponed for a period of time, the response-shock (R-S) interval. On this schedule, no shocks will ever be delivered if each response follows the preceding one within the response-shock interval. In discriminated avoidance (Figure 5.3B), a discriminative stimulus (SD) precedes each shock delivery. A response during the "warning signal" SD cancels the shock delivery and (usually) terminates the SD. Responses during the intertrial interval have no effect. Every shock will be avoided if one response occurs during each SD.

Figure 5.3 Event records or timelines illustrating the procedures of (A) free operant avoidance; (b) discriminated avoidance; and (c) escape.

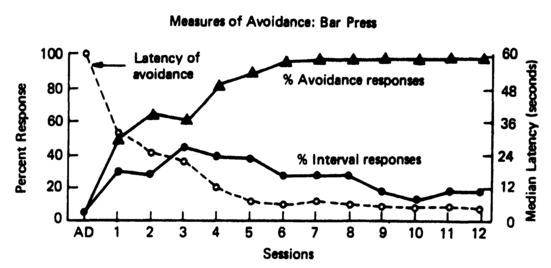

Some data on the acquisition by rats of a iever-press response to avoid an aversive stimulus of foot shock are shown in Figure 5.4. After an intertrial interval which averaged 10 minutes, a 1,000 Hz tone SD was presented. If the lever was pressed during the SD, it was terminated and shock was avoided. This study also involved an escape contingency. If the rat failed to make the avoidance response within 60 seconds, shock was delivered continuously until a response occurred (Hoffman and Fleshier, 1962). Figure 5.4 shows that the average response latency for the group of rats declined steadily across sessions, while the number (percentage) of avoidance responses increased. Both latency and number of responses reached an asymptote in the seventh session and showed little further change. The third measure shown is the number (percentage) of intertrial intervals (SΔ periods) in which a response occurred. Comparison of the avoidance curve with the intertrial interval responding curve gives a classic example of the development of a discrimination: SD responding increases first, then SΔ responding increases. Then, as SD responding continues to increase, SΔ responding reaches a peak, thereafter declining towards zero. The acquisition of avoidance behavior and its discriminative control thus proceeds in the fashion familiar to us from many types of positively reinforced behavior, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Figure 5.4 Three measures of behavior during acquisition of a discriminated lever-press avoidance response. Data are from a group of 12 rats (Hoffman & Fleshier, 1962).

In discriminated avoidance, the response generally has two consequences: SD termination, and shock avoidance. What happens when only one of these consequences is provided for the response? Kamin (1957) found that while shock avoidance per se produces a certain level of responding, the SD-termination contingency also enhances responding. So the removal or absence of the SD for the avoidance response appears to be a reinforcing event, an idea to which we shall return shortly.

Free operant avoidance is, as its name implies, a procedure in which a response occurring at any time serves to postpone or eliminate programmed aversive events. No signals are ever presented to warn the participant of impending aversive stimuli. This schedule, first devised by Sidman (1953) and illustrated in the time-lines of Figure 5.3A, leaves the animal free to respond at any time, and without any external cues, or signals, as to when to make that response.

An example of the acquisition of a lever-pressing response by a rat on Sidman's free-operant avoidance schedule is shown in Figure 5.5. In this case, both the R-S and S-S intervals were 30 seconds. After an initial period where many of the shocks used as aversive stimuli were delivered, the rat developed fairly rapidly a sustained moderate rate of responding, which resulted in shocks being delivered only occasionally (Verhave, 1959). This means that only rarely did the rat pause for more than 30 seconds (the R-S interval) or fail to respond within 30 seconds of receiving a shock (the S-S interval).

This is a remarkable performance when you consider that when the rat is successful, nothing happens. That is, since no external stimulus consequences are presented, the only feedback from making a response constitute so-called kinesthetic aftereffects (that is, sensations produced within the body by the movements involved in pressing the lever) and whatever small noise the lever makes. Compare this situation with the discriminated-avoidance schedule, where an explicit SD signals the time to respond, and SD termination usually follows completion of the response.

Figure 5.5 Cumulative records of lever press avoidance during training of a rat on free operant avoidance. Shock deliveries are indicated by small vertical marks. The first record is at the bottom of the figure. From the second record onwards, very few shocks were delivered (Verhave, 1959).

As discussed in Chapter 2, everyday descriptions of avoidance behavior are couched in purposive terms. In the case of avoidance, we say that we turn the wheel of a skidding car away from the direction of the skid to avoid a crash, that one builds a bridge in a certain way to avoid its collapsing, that a deer flees in order to avoid a pursuing wolf. The term "to", or "in order to", imputes a certain purposive quality to the behavior. Purposive or teleological explanations are generally rejected by scientists on the grounds that such explanations purport to let a future (and, therefore, nonexistent) event be the cause of a present (existing) event; and because purposive explanations add nothing to the bare facts. Consequently, behavior theorists persistently sought to explain the facts of avoidance by a mechanism that was clearly non-teleological. However, in attempting to frame an account of avoidance behavior that was analogous to simple operant conditioning or escape behavior, they struck a serious problem. In both simple operant conditioning and escape learning, behavior is reinforced by making a stimulus change consequent upon that behavior (even with intermittent reinforcement, some responses are immediately followed by the reinforcing stimulus). In avoidance learning, however, the aversive stimulus is present neither after the response nor before it. Rather, it occurs intermittently in the absence of responding.

There are at least two routes to a solution of this problem. Either some stimulus, or stimulus change, must be identified which is a consequence of responding and acquires the power to reinforce avoidance responses; or we accept the facts of avoidance behavior as a basic, and irreducible, process in which behavior changes because that change produces a reduced frequency of aversive events over a period of time. A review of the extensive experimental research literature shows that, in various nonhuman species, negatively-reinforced behavior can be maintained by conditioned aversive stimulus termination, safety signal presentation, aversive stimulus density reduction, and delay of the aversive stimulus. This suggests that while short-term consequences (for example, the onset of a safety signal) may have big effects, consequences over a longer period (for example, the occurrence of a period of time with a lower frequency of aversive events) may also be effective. However, avoidance behavior sometimes fails to develop where one or more of these inducing factors are present.

The main reason for "failures" is that every avoidance procedure involves not only a negative reinforcement contingency, but also the necessary ingredients for aversive classical conditioning, which is discussed in Section 5.4. Aversive stimuli are repeatedly paired with either apparatus cues or SD's, and we often find that species-typical aversive behaviors are elicited by avoidance situations (Bodes, 1970). Species-typical aversive behaviors represent those unconditioned behaviors that occur naturally in response to attack. In rats — most often used in experimental studies — the most readily identifiable ones comprise freezing, flight, and attack, and these behaviors are sometimes incompatible with the required operant response. When factors relating to the evolutionary history of the species start to "interfere" with the outcome of conditioning experiments, the choice of operant response class is no longer arbitrary, in the sense defined in Section 2.4, and, relatedly, the findings may not generalise to other species and to human behavior. Fortunately, with avoidance, as with the other behavioral processes we have introduced, most of the findings are not restricted in this way.

Punishment is a procedure in which aversive stimuli are made contingent upon behavior. The modification of behavior by contingent presentation of aversive stimuli is an extremely controversial subject. Punishment is an emotive word, and much progressive thinking in education, psychotherapy, child rearing, penal reform, relationship-improvement programs, and even radical social change, is based on the premise that our first step must be to eliminate punishment. The validity of this claim depends on what is meant by punishment, the effects (direct and indirect) that punishment has, and ethical considerations. These issues are discussed in Chapter 10.

We define punishment, similarly to other behavioral processes, as a procedure with a characteristic outcome. In the punishment procedure, a stimulus is made contingent upon a specified response. If a variety of characteristic effects occur, particularly a reduction in frequency or suppression of that response, then we say that punishment has occurred, and that the contingent stimulus is a punisher, a punishing stimulus, or an aversive stimulus. We can represent the procedure as:

R → S–

where R is the specified response, and

S– is an aversive stimulus.

Clearly, the punishment paradigm supplements escape and avoidance procedures as an independent way of assessing the aversiveness of contingent stimuli. However, note that, in parallel with all other operant procedures, the effect of the contingent stimulus depends on the particular situation, the particular response selected for study, and other contextual variables. We cannot assume, for example, that the verbal command, "Sssh!", which effectively silences a child talking in church, will also have this effect in a schoolroom. Neither can we assume that a stimulus identified as an effective punisher for one operant will necessarily effectively punish another operant behavior, or that a stimulus found aversive from escape or avoidance procedures will necessarily act as a punisher. In practice, the ubiquitous punishers in laboratory experiments with nonhuman participants have been, almost exclusively, electric shocks, as has also been the case in studies of escape and avoidance. Occasional studies with humans have also used shocks, but, as we shall see later, aversive stimuli that do not cause pain are more ethically acceptable. All the issues concerned with the application of punishment procedures with human behavioral problems are discussed in Chapter 10.

In ordinary language, the word "punishment" is used ambiguously. It can either mean the delivery of an aversive stimulus contingent upon a response, as here, or simply the delivery of an aversive stimulus in no particular relation to behavior. We have removed this ambiguity, and we shall see later in this chapter that there are important behavioral differences between the two procedures. We also depart from ordinary language in specifying that punishment has only occurred when a particular behavioral effect is seen.

Early laboratory work on punishment appeared to support the conclusion that punishment yields only a transient effect on operant behavior (Estes, 1944; Skinner, 1938), and this conclusion is still occasionally quoted. However, as long ago as 1966, an authoritative review was produced by Azrin and Holz of later findings where reliable punishment effects were obtained. They pointed out that a number of methodological requirements must be met to enable punishment phenomena to be investigated successfully, and these were not always achieved in the early studies. There must be a reliable methodology for maintaining operant behavior in the absence of punishment, which is supplied by the use of schedules of intermittent positive reinforcement, and there must be a punishing stimulus which can be defined in terms of physical measurements (so that it can be reliably reproduced), delivered in a consistent manner to the experimental participant, and which cannot be escaped from (for example, by leaving the experimental situation). The punishing stimulus should also be one that does not elicit strong behavioral responses itself, and which can be varied in intensity over a large range. From the 1960s, use of intermittently reinforced operant behavior in Skinner boxes with electric shock delivered as the punishing stimulus, met all these requirements. The main conclusions of Azrin and Holz (1966) were consistent with the hypothesis that punishment can have effects that are broadly opposite to those of positive reinforcement: within limits, more intense and more frequent punishment produces greater response suppression, provided that the punishing stimulus is reliable and immediately follows the response. Interestingly, if the punisher is itself delivered on an intermittent schedule, then the effects are analogous to those seen with positive reinforcement. Thus, response suppression tends to increase towards the end of the ratio requirement if the punisher is delivered on a fixed ratio schedule, and towards the end of the time interval if the punisher is delivered on a fixed interval schedule. Other factors they identified as contributing to punishment effectiveness were that long periods of punishment should be avoided, that punishment should be correlated with extinction but not with delivery of a positive reinforcer, and that punishment effectiveness increases when an alternative (reinforced) response is available. Not all the data they reviewed was from nonhuman studies, and Figure 5.6 shows a clear effect of punishment (by "an annoying buzzer sound") on human operant behavior, which was greatly enhanced when an alternative reinforced response was also available.

Inhibitory stimulus control (as described in Section 4.9) can also be demonstrated with punishment procedures. Using pigeons pecking at an illuminated plastic key located on the wall for food reinforcement, Honig and Slivka (1964) punished key-pecking in the presence of one wavelength of the light used to illuminate the key. They found that response rates were suppressed in the presence of that wavelength, and response suppression generalized to other wavelengths with suppression declining as the wavelengths become more different from the punished wavelength. This effect is directly analogous to that seen when responding is extinguished in the presence of one visual stimulus (SΔ) while being reinforced in the presence of others (SD).

Figure 5.6 Cumulative records of the punished responding of human participants on a VI schedule of reinforcement under three conditions. When an alternative response was available, punishment totally suppressed responding (Azrin & Holz, 1966, based on data from Herman & Azrin, 1964).

Punishment can be shown to modify human behavior under laboratory conditions. We need not employ painful aversive stimuli, since we can rely on the aversiveness of loss of potential reinforcements. Bradshaw, Szabadi, and Bevan (1977) examined the effects of a punishment contingency on the performance of humans pressing buttons for points on a variable-interval (VI) schedule. The points could be exchanged for money at the end of the experiment. After initial training, multiple VI schedules were used, in which different reinforcement rates were obtained in different components, and a variable-ratio (VR34) punishment contingency was superimposed on alternate sessions. Reinforcement on the VI schedules were always signaled by a very brief green light flash and the addition of one point to the score on a counter in front of the participant. When punishment occurred, a red light flashed on briefly and one point was subtracted from the counter.

Figure 5.7 Response rate, with and without a punishment contingency for three human experimental participants as a function of reinforcement rate in the components of a multiple VI schedule. The bars give standard errors (Bradshaw, Szabadi, & Bevan, 1977).

The results from their three participants are shown in Figure 5.7. Without punishment, response rate was a negatively accelerated function of reinforcement rate in each component of the multiple schedule, and the data are a good fit to an equation describing Herrnstein's (1961) matching law. The matching law, which is discussed further in Chapter 11, is a quantitative formula which relates rate of responding for an operant to obtained rate of reinforcement for that response. As can be seen, the response rate increases towards an asymptote. This function has been shown to fit data for a very large number of experimental studies with nonhuman participants, and is here shown to fit human data. During punishment, the maximum (asymptotic) response rate was greatly reduced for all participants, but the data were still a good fit to the curve predicted by the matching law. This shows a consistent and extremely orderly effect of punishment on human operant performance.

It is also important that the effectiveness of punishment is evaluated in significant non-laboratory situations and a number of such studies are described in Chapter 10. Given that, within laboratory settings and applied settings, punishment can be an effective contingency, many questions still remain. One of the most interesting is the question as to what behavior increases if a punishment contingency is successful in greatly reducing one category of behavior. Not much research has been done on this, but Dunham (1971) suggested, based on experiments with gerbils in which several different behaviors were recorded while one was punished, that it was the most frequent unpunished behavior that increased in probability, and thus filled the time made available by suppression of the punished behavior. However, Crosbie (1993) in a formally similar study with human participants found that when one of four operant responses was punished with monetary loss, in a similar fashion to the Bradshaw et a!. (1977) study, the punished response was reduced in frequency but no rule of the type suggested by Dunham predicted which responses would increase in frequency.

Escape, avoidance, and punishment procedures all involve programmed relationships between responses and aversive stimuli. The other general class of aversive contingencies involves relationships between neutral (conditioned) stimuli and aversive stimuli, and are varieties of classical conditioning. Classical conditioning can occur in procedures that were designed to demonstrate the operant conditioning phenomena of escape, or avoidance or punishment. These findings can be seen as a "nuisance" (given that the classical conditioning was not the main focus of study), but are better taken as illustrations of how operant and classical conditioning interact in laboratory settings as well as in natural settings.

Aversive classical conditioning is studied directly when contingencies are arranged between CS's and aversive US's. Many aspects of the resultant process parallel appetitive classical conditioning. Indeed, many Pavlovian phenomena were originally demonstrated with aversive conditioning. The responses most often studied were salivation and leg flexion in dogs, and eyeblinks and heart rate in humans and other species. However, all these paradigms involve restrained organisms. If freely-moving participants are used, some effects are seen in aversive classical conditioning that distinguish it from appetitive classical conditioning.

These effects are twofold: species-typical aversive behaviors and suppression or disruption of ongoing behavior can be elicited by the aversive CS, In some situations, these are two sides of the same coin, because the elicited aversive behaviors interfere with the ongoing behavior; but in others disruption occurs during an aversive CS that cannot be attributed to species-typical aversive behaviors. The latter case is called conditioned suppression and is discussed later.

Although species-typical aversive behavioral repertoires vary from species to species (as the term implies), there are some common behaviors in these repertoires. Zener (1937) carried out an early investigation of classical conditioning in which, following initial training, he removed the restraints from the dogs and then observed the effects of presenting various CS's. Where a localized CS (such as a light coming from a lamp) had previously been followed by an appetitive US, the dogs approached it (and licked it!), but where the CS had previously been followed by an aversive US, the dogs simply ran away from it once given that opportunity. Withdrawal of this type has, not surprisingly, been found to be a common classically conditioned species-typical aversive behavior, in situations which allow it to occur. A fair amount of other information is available about the laboratory rat, which at one time was the experimental psychologist's favorite experimental participant, and piecemeal data on other species have been recorded. It is widely agreed that freezing, defecation, flight (running away), and aggression are components of the rat's aversive repertoire. Of these, defecation and freezing can be conditioned to a CS associated with aversive stimulus (Hunt & Otis, 1953), and components of aggressive behavior are seen if a pair of rats receive a CS that has been paired with aversive stimulus (Ulrich, 1967).

Our lack of detailed information about the human behavioral repertoire makes it difficult to assess the role of species-typical behavior. However, the pioneer behaviorist, J. B. Watson, suggested that our emotional responses are acquired through classical conditioning of species-typical behavior, and similarly many contemporary accounts of the effects of "stress" on human behavior state that these species-typical emotional responses commonly occur in complex social situations where they are not appropriate or useful. One such response is the pronounced change in heart rate which occurs in fear and stress, and this has often been shown to be influenced by classical conditioning.

A typical study of conditioned suppression was carried out by Hunt and Brady (1951). They trained liquid-deprived rats to press a lever for water reinforcement on a VI schedule. When response rate on this schedule had become stable, a clicker CS was presented periodically for 5 minutes, and immediately followed by a brief electric shock US to the rat's feet. Some of the typical behavioral changes that ensued are shown in the cumulative lever-pressing records in Figure 5.8. The first CS presentation had little discernible effect, but the accompanying US (denoted by S in panel B) temporarily slowed the response rate. After a number of CS-US pairings, the CS suppressed responding almost totally, but responding recovered as soon as the US had been delivered. Because suppression of responding during the CS is dependent on a conditioning history, it is called conditioned suppression.

The conditioned-suppression procedure, first developed by Estes and Skinner (1941), has proved to be a very sensitive behavioral technique. The effect of the CS is usually described in terms of the degree of suppression of the positively-reinforced operant behavior relative to the rate of the operant response during the non-CS periods. Measured in this way, conditioned suppression increases with magnitude of the US, decreases with length of the CS, and is in general, such a sensitive indicator of classical-conditioning parameters that it has often been treated as the best method of studying classical-conditioning effects (for example, Rescorla, 1968), although it actually measures the reduction in, or disruption of, operant responding.

The sensitivity of the conditioned-suppression technique has led to its widespread use in evaluation of drug effects (Millenson & Leslie, 1974). The drugs tested have mostly been those known clinically to reduce anxiety, because conditioned suppression has often been treated as a model of fear or anxiety. Recent studies have demonstrated that conditioned suppression can be used to disentangle neuropharmacological mechanisms. For example, the conditioned-suppression reducing effects of some anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) drugs can be selectively reversed by another drug with a known effect in the brain. From this evidence we can deduce much about the pharmacological action of the anxiolytic agent.

Figure 5.8 Cumulative records showing development of conditional suppression in a rat lever pressing for water reinforcement on a variable-interval schedule (Hunt and Brady, 1951).

Laboratory demonstrations, along with our everyday experience, suggest that punishment is a pervasive and important behavioral process. Like positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and classical conditioning, the sufficient conditions for its occurrence are frequently met in the natural environments of humans as well as of other organisms. As Azrin and Holz (1966) point out, to "eliminate punishment from the world" would involve elimination of all contact between the individual and the physical world, because there are so many naturally occurring punishment contingencies. We learn not to do a great many things, such as touching hot surfaces, falling out of bed, shutting our fingers in doors, and all the other ways in which we avoid natural aversive consequences.

If we agree that the contingencies of punishment specified by the physical world are not eradicable, can we and should we nevertheless minimize the number of punishment contingencies operated by individuals and institutions upon individuals? We can distinguish between those that involve painful stimuli and those that involve response cost or time out. "Time-out" refers to all procedures which involve temporary prevention of access to positive reinforcers. In everyday life, these include removal of attention (being ignored), withdrawal of privileges, and levying fines. Many experimental studies with nonhuman animals have shown that painful stimuli elicit aggressive behaviors and these can become predominant. Clearly, this is highly undesirable and would seem to be sufficient reason to reject the use of punishment contingencies that involve painful stimuli, if alternatives can be found. Time-out has been used effectively to modify behavior in a number of procedures, and unsurprisingly works best when there is a high rate of reinforcement prior to time out (Kazdin, 1994). We will provide a detailed account of its application in Chapter 10.

There is a more subtle problem that applies to all types of punishment contingency that are administered by another individual or an institution. Through classical conditioning, the agent may itself become aversive, or the aversive properties of the situation may result in avoidance learning. The punishment contingency will then be ineffective, because it will no longer make contact with the individual's behavior. Instead, the individual will refuse to have anything to do with the other individual or the institution.

Against the drawbacks of punishment, must be set any advantages it may have over alternatives. Its chief advantage is undoubtedly the rapidity with which response suppression can be produced. It is often pointed out that an equivalent change can be produced by positive reinforcement without undesirable side-effects, but reinforcing an alternative response may not have as specific or rapid effects on the behavior to be eliminated. If a child persists in running off the sidewalk into the path of vehicles, socially administered punishment may be the only way of preventing the "natural" punishment contingency from having more drastic effects. Again, in Chapter 10 we will review recent studies that have successfully used punishment to eliminate an otherwise life-threatening behavior.

It might be objected that the issues raised in this section so far concern the "pragmatics" rather than the "ethics" of using punishment. From the point of view of behavioral analysis, however, these two topics cannot be dissociated. An ethical precept, such as "hitting people is wrong", can only be evaluated by defining the terms involved, assessing the consequences of implementing the procedure so defined, and comparing these with the consequences of alternative procedures, or of doing nothing. As indicated by the choice of example of ethical precept given above, a major contemporary concern is whether procedures that involve inflicting pain should be used, particularly in child rearing or with other vulnerable individuals. The discussion in this section, and indeed in the whole of this chapter, indicates that rather than trying to answer apparently simple questions of this sort directly it will be more productive to go through the steps of defining terms, specifying procedures, and then assessing outcomes, or consequences, of such interventions and their alternatives.

It is perfectly possible, at least in principle, to carry out such analyses for specific cases, perhaps of a child who is highly disruptive in classroom settings or of a person with learning difficulties who engages in self-injurious behavior, but we should note that throughout this volume two major themes have been the importance of context, or control by discriminative stimuli, and of personal history. Thus we can anticipate that any judgment that is arrived at as to the appropriateness of punishment or another non-aversive intervention will apply to that specific case in the context where the behavior of concern occurs and in the light of the relevant history of reinforcement of the person. A case of disruptive classroom behavior might, for example, be successfully eliminated by the threat that all the children in the class will miss a break period if it continues (this a group punishment contingency); while self-injurious behavior might decline if social interaction were to be provided as an alternative activity. Such examples show how behavioral analysis uses general principles to explain how people are different from each other and require individualised assessment and treatment if their behavior is to change. They also suggest that general ethical precepts, such as "hitting people is wrong", cannot be shown to be true or false. In Chapter 11, we will review how human rights of individuals in treatment should be protected. Amongst the guidelines presented there is "an individual has a right to the most effective treatment procedures available". This is a key idea in evaluating the appropriate use of aversive contingencies.

Although completely general conclusions on these issues cannot be drawn, it is possible to discover whether there is a broad consensus as to how to proceed. Wolf (1978) argued that it was appropriate to establish the social validity of applied behavioral analysis by assessing public opinion as to the social significance of its goals, the appropriateness of its procedures and the importance of its effects. Relatedly, Kazdin (1980) devised the "treatment evaluation inventory", which presents people with a written (but hypothetical) case description along with a description of a number procedures and asks them to rate acceptability of each of the procedures for the behavioral problem described. Blampied and Kahan (1992) used this inventory with 200 people recruited from a cross-section of the general public and asked them to rate the acceptability of response cost, social reprimands, time out, overcorrection and physical punishment (the actual use of all these procedures is reviewed in Chapter 10) for a 10-year-old boy or a girl, at home or at school. They found that response cost procedures (where a "fine" or other penalty is imposed) were rated the most acceptable, with physical punishment being markedly less acceptable than any of the others.

This discussion has dealt with the genera! implications of aversive contingencies in human behavior. Chapter 10 includes an extended discussion of the use of behavioral techniques designed to decrease human behavior in problem cases, and there we will see that, as suggested here, many of the difficult issues can be resolved in specific cases. It will also be clear, however, that value judgments are inevitably involved and we will return explicitly to those in a review of human rights issues in Chapter 11.

Behavior is affected riot only by positive reinforcement contingencies but also by operant and classical conditioning processes involving aversive contingencies. Consequently, this chapter presents a review of the operation and effects of aversive contingencies.

Escape learning, a form of operant conditioning, is perhaps the simplest and most basic type. A variety of experimental procedures have been used in studies of nonhuman animals to show how conditioning proceeds when the operant response results in termination of an aversive stimulus. In such procedures, the presentation of the aversive stimulus acts as an establishing operation, because it motivates the animal to remove it. While few studies have involved human participants for ethical reasons, it is important that we understand escape because it is just as important for humans as for other species.

In avoidance learning, an aversive stimulus is programmed to occur unless the operant response occurs. Again, a variety of different procedures have shown this contingency to be effective in modifying the behavior of nonhuman animals. The success of other species on this apparently more complex task suggests that the same set of behavioral processes is involved as in other tasks. More complex experiments have shown this to indeed be the case. However, there are some instances where the avoidance contingency fails to produce the expected change in operant behavior. In these instances, the occurrence of other unconditioned or classically conditioned behavior is responsible for the "failure". This illustrates the importance of understanding all the effects that aversive stimuli may have.

Punishment is a procedure in which aversive stimuli are made contingent upon the operant response and thereby reduce its frequency. This also has reliable effects in experiments with nonhuman animals, provided various methodological concerns are addressed. A small number of experimental studies with humans have also produced consistent effects The general pattern is that punishment has effects that are broadly opposite to those of positive reinforcement, it is important to realize that "punishment" is here used as a technical term that does not have all the meanings it has in everyday language.

Classical conditioning has often been demonstrated in experiments with aversive unconditioned stimuli, and the outcome is similar to that when positive, or appetitive, unconditioned stimuli are used. However, the form of the conditioned response often involves behaviors associated with fear and escape when aversive stimuli are used. This means that these behaviors may "interfere" with operant behavior in any procedures where aversive stimuli are being used. These issues are addressed directly with the conditioned suppression procedure, where aversive classical conditioning is superimposed on positively reinforced operant behavior. This procedure has provided a useful baseline for investigation of many variables, including anxiety-reducing drugs.

Discussion of aversive contingencies invariably raises ethical issues. It is important to remember that aversive contingencies exist in the physical as well as the social environment of everyone, and we should therefore make efforts to understand their operation. We will see in later chapters that there is good evidence to prefer the use of positive reinforcement contingencies to change behavior wherever possible, but that this is not possible in every case. This further underlines the need to know how aversive contingencies affect behavior. Later chapters will provide a detailed account of the appropriate use of contingencies designed to reduce unwanted problematic behavior, and relate this to the human rights of individuals in treatment. The use of aversive contingencies is a major issue in the assessment of the social validity of behavior analysis, and techniques for this assessment have been developed in recent years.