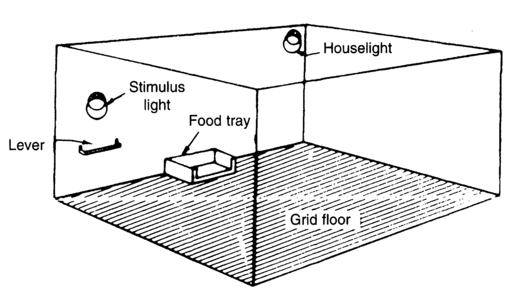

Figure 2.1 Essential features of a Skinner box for a rat, or other small rodent. The box is situated inside a sound-attenuating housing to exclude extraneous noises and other stimuli.

As we saw in the previous chapter, the notion that much of animal behavior consists of reflexes was well-known to the scientific community by the latter part of the nineteenth century, and Pavlov's ideas about conditioned reflexes as a model for much of learnt behavior were also rapidly and widely disseminated. However, there is much behavior that apparently occurs at the instigation of the individual, rather than being elicited by the onset of an external stimulus. This includes those actions of human beings traditionally described as voluntary, purposeful, spontaneous, or willful, and this class of behavior was thought to be beyond the scope of a scientific or experimental analysis until the turn of the twentieth century. The relationship between this sort of behavior and reflexive behavior is well illustrated by the following passage:

... when a cat hears a mouse, turns towards the source of the sound, sees the mouse, runs toward it, and pounces, its posture at every stage, even to the selection of the foot which is to take the first step, is determined by reflexes which can be demonstrated one by one under experimental conditions. All the cat has to do is to decide whether or not to pursue the mouse; everything else is prepared for it by its postural and locomotor reflexes (Skinner, 1957, p. 343; italics added).

The cat's behavior in this situation has an essential non-reflexive ingredient, although reflexes are vital for the success of its attempt to catch the mouse. Hidden in the simple statement, "all the cat has to do is to decide," lies the point of departure for an analysis of purposive behavior, whose occurrence is not related to the presence of an eliciting (that is, immediately-producing) stimulus, either as a result of the history of the species (as in a reflex) or as a result of the history of the individual (as in a conditioned reflex).

The experimental analysis of so-called purposive behavior has proceeded in a fashion typical of the development of scientific explanation and understanding in many other disciplines. Typically, a small number of systematic relationships are established first and repeatedly investigated. As new relationships are added to those previously established, the group of principles or "laws" begins to give a partial understanding of the area. Starting with Thorndike's extensive pioneer work on learning in cats and chicks, psychologists have searched for relationships between purposive behavior and other events. Consider the problems in beginning such an analysis: how do we go about finding variables or events to which purposive behavior might be significantly related? Initially, we must proceed by intuition and crude observation. Very often, forward-looking philosophical speculation precedes scientific investigation of a problem, and in this case the British philosopher, Herbert Spencer, wrote:

Suppose, now, that in putting out its head to seize prey scarcely within reach, a creature has repeatedly failed. Suppose that along with the group of motor actions approximately adapted to seize prey at this distance ... a slight forward movement of the body [occurs]. Success will occur instead of failure ... On recurrence of the circumstances, these muscular movements that were followed by success are likely to be repeated: what was at first an accidental combination of motions will now be a combination having considerable probability (Spencer, 1878).

Here, a quarter of a century before Thorndike, Spencer suggests that the effect of an action is all important in determining its subsequent occurrence: "those muscular movements that were followed by success are likely to be repeated". This is the key idea that led Thorndike to the law of effect and Skinner to a thorough-going experimental analysis of behavior.

If a piece of behavior has a purpose, then that purpose can be described by the usual consequences or effect of that behavior. Indeed, we could almost say that purposive behavior is that behavior which is defined by its consequences. For example, we say that we tie a shoelace to keep our shoe on, but an equivalent statement is that we tie a shoelace, and on previous occasions when we tied it, it did stay on. Furthermore, we identify instances of shoelace tying by their effects: if the shoe stays on, then this counts as an example of "shoelace tying"; otherwise, it does not. Many other everyday behaviors can be subjected to a similar analysis; going to school, making a cup of coffee, playing a musical instrument, and so on.

Apparently, we have two ways in our language to account for the same behavior. These are: (1) the purposive, in which we use the term to (or, in order to) and imply the future tense; or (2) the descriptive, in which we state the present behavior and conjoin it with what happened in the past. Which is more appropriate for use in a scientific analysis of behavior? Consider the following example:

During the war the Russians used dogs to blow up tanks. A dog was trained to hide behind a tree or wall in low brush or other cover. As a tank approached and passed, the dog ran swiftly alongside it, and a small magnetic mine attached to the dog's back was sufficient to cripple the tank or set it afire. The dog, of course, had to be replaced (Skinner, 1956, p. 228).

In this example, the dog's behavior can be explained by reference to past events, as it presumably had been rewarded for running to tanks by food, petting, and the like, but not by reference to its purpose. We can immediately reject the idea that the dog ran to the tank in order to be blown up. This extreme case illustrates the general principle that the future does not determine behavior. When we use "purposive language", we are drawing on our knowledge of the effects of our behavior on earlier occasions; it is that "history" which determines behavior.

In brief, a very real and important class of behavior, arising out of situations that seem to involve choice or decision, is called purposive behavior. Such behavior, it should be apparent at once, falls into Descartes' category of "voluntary" and constitutes action that is often called "willful", or said to be done by "free choice". Our present analysis indicates that this behavior is in some way related to, and thus governed by, its consequences on previous occasions. For that reason we shall henceforth replace the older term, purposive, with Thorndike's term, "instrumental", or Skinner's term, "operant". Calling behavior "instrumental" or "operant" suggests that, by operating on the environment, the behavior is instrumental in obtaining consequences. Neither of these terms implies the confusing conceptual scheme that "purposive" does, yet both attempt to capture the fundamental notion that the past consequences of such behavior are one of its important determinants.

If a hungry laboratory rat is put into a small enclosure, such as the one shown in Figure 2.1, and certain procedures are carried out, a number of interesting changes in the behavior of the rat may be observed. For present purposes, the significant features of the enclosure, or Skinner box, are: (1) a tray for delivery of a small pellet of food to the rat; and (2) a lever or bar, protruding from the front wall that, when depressed downward with a force of about 10 grams, closes a switch, permitting the automatic recording of this behavior. The significant features of the rat are as follows: (1) it is healthy and has been accustomed to eating one meal each day at about the same hour as it now finds itself in the box; (2) it has previously been acclimatized to this box during which time food was occasionally delivered into the tray, and it now readily approaches the food tray and eats food whenever it is available.

Figure 2.1 Essential features of a Skinner box for a rat, or other small rodent. The box is situated inside a sound-attenuating housing to exclude extraneous noises and other stimuli.

Consider the following simple experiment. The rat is left in the box for an observation period of 15 minutes. During this time, no food is delivered, but the rat engages in a lot of exploratory behavior. It noses the corners, noses the food tray, occasionally depresses the lever, rears up against the walls, and so forth. Other activities observed include sniffing and grooming. None of these responses is reflexive. That is, no specific eliciting stimulus can be identified for any of them. Thus, we call them emitted responses. Clearly, there are stimuli present that are related to the occurrence of these responses – the general construction of the box obviously determines which responses can occur, for example – but none of the stimuli elicits specific responses at specific times.

The rate and pattern of the emitted responses of an animal in an environment in which no special consequences are being provided for any response defines the operant-level of those responses. Operant-level recordings will provide an important baseline against which we shall later compare the effects of providing special consequences for one or a number of the emitted responses.

After the observation period, the following procedure is initiated. Each time the rat presses the lever, a pellet of food is delivered into the tray. As the rat has previously learned to retrieve food pellets and eat them as soon as they are delivered, each lever-pressing response is now immediately followed by the rat eating a food pellet. We have introduced a contingency between the lever-pressing response and the delivery of food pellets. Provided the operant-level of lever-pressing is above zero (that is, lever presses already occur from time to time), this new contingency will produce a number of behavioral changes. Soon the rat is busily engaged in lever pressing and eating pellets. These marked changes in its behavior have occurred in a relatively short period of time. In common parlance, the rat is said to have learned to press the lever to get food. Such a description adds little (except brevity) to the statement that the rat is pressing the lever frequently now and getting food, and this follows a number of occasions on which lever pressing has occurred and been followed by food.

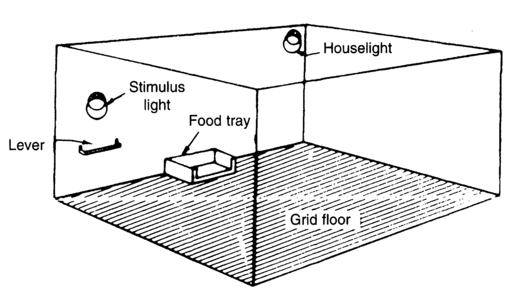

Figure 2.2 Event records, or "time lines", illustrating a contingency between, or independence of, Event A and Event B. An event occurs when the recording line shifts from the lower ("off") position to the upper ("on") position. In an operant conditioning experiment, Event A might be a lever press and Event B might be food delivery.

The experiment we have described is an instance of the prototype experiments on operant behavior carried out by B. F. Skinner in the 1930s. The most striking change in behavior that occurs when food is presented to a hungry rat as a consequence of lever pressing is that lever pressing dramatically increases in rate. This is an example of operant conditioning, because the increase in rate is a result of the contingency between the lever-pressing response and the food. If there is a contingency between two events, A and B, this means that B will occur if, and only if, A occurs. We say that B is dependent upon A, or that A predicts B, because when A occurs, B occurs; but if A does not occur, B will not occur. Sequences of events in which B is contingent upon A and when B is independent of A are illustrated in Figure 2.2. In our present example, food (B) is contingent upon lever pressing (A). Another way of saying this is that food (B) is a consequence of lever pressing (A). This is a simple example of a reinforcement contingency, a term which we will use later for more complex examples.

What we wish to do is to describe in detail, and as quantitatively as possible, the changes in behavior that result from the simple operation of providing a special consequence for only one of an individual's normal ongoing activities in a situation. To do that, we shall consider four complementary ways of viewing the changes in the rat's behavior when, as here, one of its behaviors is selected out and given a favorable consequence:

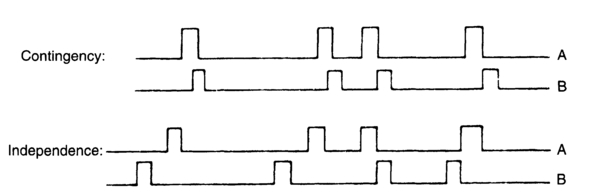

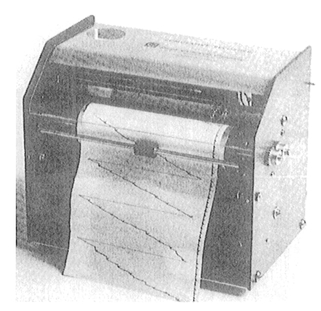

The increase in response frequency can clearly be seen on the ink recorder developed by Skinner: the cumulative recorder illustrated in Figure 2.3. The pen moves continuously across the paper in one direction at fixed speed, and this axis thus records elapsed time. Whenever a response occurs, the pen moves in a perpendicular direction by a small step of fixed size. The resulting cumulative record shows the number of responses and the time during which they occurred, and so illustrates the pattern of behavior. Examples of actual records from experimental participants exposed to a procedure like the one outlined are shown in Figure 2.4. When a contingency between lever pressing and food was established for these experimental participants, there was a relatively abrupt transition to a high rate of response. It should be noted that the time spent in the experiment before this transition varied and, in the examples in Figure 2.4, could be up to 30 minutes. Once the transition had occurred, the rate of responding was fairly constant; this is shown by the steady slopes of the graphs. The transition, because of its suddenness, resembles "one-trial" learning, rather than a gradual change. Ink recorders of the type used by Skinner in the 1930's have now been replaced by computer systems which can be programmed to draw graphs of the progress of an experiment using exactly the same dimensions as those shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.3 A cumulative recorder of a type that was used extensively until replaced by computer software systems. When operational, the paper moved continuously through the machine. Other details are given in the text. (Courtesy of Ralph Gerbrands Co. Inc.).

Figure 2.4 Cumulative records obtained from four hungry rats on their first session of operant conditioning. Lever presses were reinforced with food. Each lever press produced an incremental step of the recorder pen (Skinner, 1938).

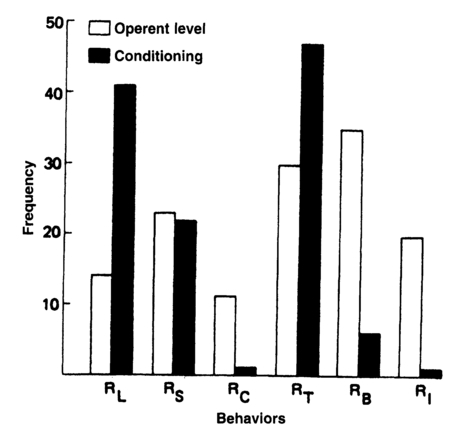

In any case of operant conditioning, there will always be concomitant changes in other behavior as the operant response increases in frequency. If the experimental participant is a laboratory rat, and it begins to spend a large part of its time lever pressing, retrieving and eating food pellets, there must necessarily be a reduction in the frequency of some of the other responses (R's) that were previously occurring in the Skinner box. For example, in an undergraduate classroom demonstration of lever-press operant conditioning at Carnegie-Mellon University, the following behaviors of a hungry rat were recorded over 15 minutes of operant level, and then over a subsequent 15 minutes of conditioning the lever pressing:

RL = lever pressing

RS = sniffing

Rp = pulling of a small chain that dangled into the box from overhead

RT = nosing the food tray

RB = extending a paw to a lead block that rested in one of the far corners

Rl = remaining approximately immobile for 10 consecutive seconds.

It was found that while lever pressing and tray nosing increased, the other responses that were not associated with eating declined. Indeed, the operant conditioning process can be seen as one of selection. Those responses that are selected increase in relative frequency, while most of the remainder decline. Figure 2.5 illustrates with a histogram how the pattern of behavior had changed.

Sequential changes in responding also occur. When food is made contingent upon a response, other activities involved in food getting increase in frequency, but this is not the only change that takes place. A sequence of responses is rapidly established and maintained. In the lever pressing example, the sequence might be:

lever press>tray approach>tray entry>eat food> lever approach>lever press...and so on.

This continuous loop of behavior is quite different from that seen in operant level. Two members of the established loop will serve to illustrate the point. Let us ignore, for the moment, all the other possible behavior in the situation and confine our attention to (1) pressing the lever, and (2) approaching the food tray. Prior to conditioning of the lever press, these two responses occur in such a way that, when the animal performs one of them, it is likely to repeat that one again rather than perform the other (Frick and Miller, 1951). Thus, a fairly typical operant-level sequence of lever press (RL) and tray-approach responses (RT) might be

Figure 2.5 Relative frequencies of several behaviors occurring in a Skinner box before and after operant conditioning of lever pressing. Details are given in the text.

RL RL RT RL RL RL RT RT RT ...

During conditioning, this sequence quickly changes to the alternation

RL RT RL RT RL RT ...

with hardly any other pattern to be seen (Millenson and Hurwitz, 1961). This re-organization of behavior probably takes place as soon as rapid responding begins.

Changes in response variability always occur in operant conditioning. "The rat presses the lever" describes an effect the rat has on the environment, not a particular pattern of movements by the rat. There is a wide range of movements that could have the specified effect. Presses can be made with the right paw, with the left, with nose, shoulder, or even tail. We group all of these instances together and say that the class of responses that we call lever pressing is made up of all the possible ways of pressing a lever. However, not all members of the class are equally likely to occur in an experiment nor, on the other hand, does the same member occur repeatedly. Several processes interact to determine exactly which forms of the response are observed. First, there is a tendency for the topography of the response to become stereotyped under certain conditions. By "topography" we mean the pattern of muscular movements that make up the response; when this becomes stereotyped, the response looks exactly the same on each occasion that it occurs. One situation in which stereotyped behavior develops is when very little effort is required to make the response. Guthrie and Horton (1946) took photographs of cats and dogs who were required to make a pole-tilting response to get out of a box, and found that successive instances of the response made by particular individuals were strikingly similar. Relatedly, photographs of sportsman engaged in skilled performances on different occasions (for example, a tennis player serving) often look identical. A second process involved is described by Skinner's (1938) "law of least effort". This states that the form of the response made will tend to be that which requires the least effort. In the experiment described above, it is typically found that, while different participants start out by pressing the lever in various ways, as the experiment progresses, they show an increasing tendency to use an economical paw movement to press the lever. Thirdly, the biology of the species influences what can be learnt. Thorndike was the first to realize that not all behaviors can be equally easily changed by certain effects or consequences. Seligman (1970) called this the preparedness of certain behaviors to be modified by certain consequences, and related this phenomenon to the evolutionary history of the species.

In summary, when operant conditioning is implemented in a simple laboratory situation such as a Skinner Box, behavior changes in four ways:

Lever pressing, string pulling, and pole tilting, represent convenient acts chosen by experimenters to study the effects of environmental consequences on behavior. The suitability of these responses for studying operant conditioning depends critically upon their ability to be modified as described. Formally, responses are defined as operants if they can be increased in frequency and strengthened in the four stated ways by making certain consequences contingent upon them. The selection of the operant response for experiments is often said to be "arbitrary", in that the experimenter is generally not interested in lever pressing per se, but only as an example of a response that can be modified by its consequences. In general, lever pressing and other simple pieces of animal behavior are chosen for experiments because they are easily observed and measured by the experimenter, and can be executed at various rates and in various patterns by the organism. Throughout this book, we will continuously extend the applicability of the principles of operant conditioning and the term "operant" well beyond lever presses and rats.

Which are the consequences of behavior that will produce operant conditioning? This is a central issue that we have carefully avoided this far. In his version of the law of effect, Thorndike stressed the importance of "satisfiers". He stated that if a satisfier, or satisfying state of affairs, was the consequence of a response, then that response would be "stamped in", or increased in frequency. At first sight, Thorndike seems to have provided an answer to the question we posed, but he merely leaves us with another: which events will act as satisfiers? It seems obvious that food may be satisfying to a hungry organism, and "armchair reflection" might produce a list of events likely to prove satisfying in general, such as warmth, activity, play, contact, power, novelty, and sex. We might also notice that there are some events that become very satisfying once the organism has been appropriately deprived. Food comes into this category, along with water when thirsty, air when suffocating, and rest when fatigued. Interestingly, it is also evident that when we are satiated, these reinforcing effects are clearly removed and may even be reversed. Consider how disagreeable it is to be obliged to eat a meal immediately after completing a previous one, or to stay in bed when completely rested.

So far, we are only guessing; how can we firmly establish whether certain events are reinforcing or satisfying? One way is to see whether they have the consequence specified by the law of effect, or, more specifically, produce the four outcomes listed in the previous section. However, according to Thorndike's definition, they must have these properties, or these events are not satisfiers! A plausible alternative suggestion was made by Hull (1943). He claimed that all such events reduce a basic need or drive of the organism and that this drive reduction is crucial to their response-strengthening effect. Subsequent research has failed, however, to support Hull's suggestion, for there are many satisfiers whose ability to reduce a basic need seems questionable. These include "artificial sweeteners" that have no nutritional value but make soft drinks just as attractive as the sugar they replace.

Thorndike's term, "satisfier", carries the implication that such events will be pleasurable, or "things that we like", but this does not help us to identify them in practice. It simply changes the form of the problem again: how do I know what you like? The things we like are, in the final analysis, the things that we will work for, but this again takes us back to the law of effect, because to say that we will work for them is just another way of saying that we will do for them what our rat will do "for" food. At this point, we shall exchange Thorndike's term, "satisfier", for Skinner's less introspective term, reinforcing stimulus, or simply, reinforcer. The operation of presenting a reinforcer contingent upon a response we will denote as reinforcement.

A reinforcing stimulus can be defined as an event that, in conjunction with at least some behavior of an individual, produces the changes in behavior specified by the law of effect and listed in the previous section. So far, we lack an independent method of identifying reinforcers other than by their effects on behavior. Moreover, the work of Premack (1965) suggests that this represents an inherent limitation. In a series of ingenious experiments, Premack established that the property of being a reinforcer can be a relative one, and that for any pair of responses a situation can be devised in which the less probable response can be reinforced by the opportunity to carry out the more probable response, and that this relationship is reversible. He made these surprising findings by breaking some of the unwritten "rules of the game" in conditioning experiments.

In one experiment, Premack (1962) studied rats making the operant response of turning an activity wheel and being reinforced with water. To ensure that water acted as a reinforcer, the rats were made thirsty at the time of the experiment and this made water a reinforcer for wheel turning. In this very conventional part of the experiment, wheel turning duly increased in frequency. In another part of the experiment, however, Premack reversed the relationship: he allowed the rats continuous access to water, but prevented access to the activity wheel except for 1 hour/day. In this unusual situation, he found that if the opportunity to run in the wheel was made contingent upon licking water from a tube, the rats spent between three and five times as long drinking during that hour than they did when this contingency was not in effect. He thus established that it is not a "law of nature" that wheel turning by rats can be reinforced with water. Instead, this result depends on the usual practice of depriving rats of water, but not activity, prior to the experiment. If the conditions are reversed, then running in the wheel can be shown to reinforce drinking. In an earlier study (Premack, 1959) the same strategy was adopted with children and the two activities of eating candy or playing a pinball machine. When the children were hungry they would operate the machine (an operant response) in order to obtain candy (a reinforcer), but when they were not hungry they would eat candy (an operant response) in order to obtain access to the pinball machine (now a reinforcer)!

The concept of "a reinforcer" is evidently a relative one; a fact that we should especially bear in mind before uncritically calling any particular stimulus in the everyday world a reinforcer. Following the line of analysis started by Premack, other researchers (including Eisenberger, Karpman, & Trattner, 1967; Allison & Timberlake, 1974; Allison, 1993: and see Leslie, 1996, Chapter 4 for a review) have demonstrated that the amount of the operant response required and the amount of access to the reinforcer that follows must also be taken into account to specify the reinforcement relationship. Most generally, it appears that reinforcement involves a set of relationships between environmental events in which the individual is "deprived" of the currently preferred rate of access to the reinforcer unless the operant response increases above its currently preferred rate. This is called the response-deprivation principle (Allison & Timberlake, 1974, and see Leslie, 1996, Chapter 4 for a brief formal statement of the principle).

As we have now defined reinforcement with reference to the current behavioral repertoire, we should take care — in the laboratory or in real-world applications — not to presume that a stimulus will necessarily continue to be a reinforcer if the conditions are radically changed. Conditions such as food deprivation are termed establishing operations, because they change the current behavioral repertoire in such a way as establish a particular event as a reinforcer. Applied researchers have recently turned their attention to establishing operations because they are not only important conditions of operant reinforcement, but may also provide a direct means of obtaining a required behavior change (see Chapters 7 and 9).

It follows form the argument developed here, that reinforcement cannot be essentially linked to biological needs or corresponding drives in the way that Hull (1943) suggested. However, it remains true that it is often possible to use the reduction of a basic drive, such as the presentation of water for a thirsty animal or food for a hungry one, as a reinforcing operation, and that for practical purposes reinforcers are often "transsituational", that is effective in many situations. This is particularly true with human behavior which is strongly affected by conditioned reinforcement, which will be described in Section 2.9.

The matters that we have been discussing in this chapter are variously referred to in the literature of psychology as simple selective learning, trial-and-error learning, effect learning, instrumental learning, instrumental conditioning, operant learning, and operant conditioning. We prefer to use the term simple operant conditioning for the situation where a reinforcing stimulus is made contingent upon a response that has a nonzero frequency of occurrence prior to the introduction of reinforcement. If a reinforcing stimulus is contingent upon a response, that stimulus will be presented if and only if the required response has been made.

Formally, the simple operant conditioning paradigm is defined as follows. Each emission of a selected behavioral act or response is followed by the presentation of a particular stimulus. If this arrangement results in an increase in response frequency, relative to operant level and relative to other behavior occurring in the situation, the incorporation of the response into a behavioral loop and the narrowing of the topography of the response, then we say that the selected behavior is an operant response, that the stimulus functions as a reinforcer for that operant, and that what occurred was operant conditioning. The reinforcement contingency can be represented diagrammatically as follows:

The arrow stands for "leads to" or "produces". This diagram can, in turn, be summarized as:

R → S+,

where R represents an operant response class and S+ the reinforcing stimulus it produces. S+ is used to denote a positive reinforcer. The distinction between positive reinforcement, of which simple operant conditioning is an example, and other types of operant conditioning, will be explained later.

This section is included partly to illustrate the breadth of application of simple operant conditioning and partly to direct our attention to some characteristically human behavior. The usual elements of all languages are sounds produced by the vibration of expelled air from the lungs, moving through and across a set of muscles in the larynx called the vocal chords. The tension of these muscles, a major determinant of the sound produced, is under the same kind of neural control as movements of the other parts of the body, and the emitted sound patterns can be considered as examples of operant behavior. The jaws, lips, and tongue act in combination with the larynx to mould the sounds and produce the more than forty different humanoid sounds known as phonemes that are used in various combinations in languages. Because the sounds of phonemes are directly dependent on the movements of the vocal apparatus, measurement of phoneme production constitutes an indirect measure of behavior, in the same way that measurement of the depression of a lever constitutes an indirect measure of the movements used by the rat in depressing that lever.

Human speech develops from the crude sounds emitted by infants. Surprisingly, the human infant during the first 5 months of life emits all the sounds used in every human language, including French nasals and trills, German gutturals, and so on (Osgood, 1953). This sound production is not elicited by stimuli, nor should it be confused with crying. Rather, in the early months of life, a baby exhibits a very high operant level of sound production. He or she may lie for hours producing gurgling sounds, sputterings, whistles, squeaks, and snorts. The technical term babbling is used to denote the spontaneous emission of these behaviors. An important advance in babbling occurs at about the sixth month, when the sequential structure of babbling is altered so that the infant tends to repeat its own vocal production (uggle-uggle, oodle-oodle, luh-luh-luh, and so forth).

The changes that occur from babbling to speaking are complex, and no single graph could describe the progress with any completeness. However, one important change that takes place is the change in relative frequency of the different sounds uttered as the baby grows older. Thus, in France, the phonemes involved in the French r and the nasal vowels are strengthened by the "reinforcing community": that is, the child's parents, its playmates, and eventually, its teachers. In English-speaking countries, a different set of phonemes is shaped into words by a different reinforcing community. Halle, De Boysonn-Bardies, and Vihman (1991) found that in four French and four Japanese 18-month-old children aspects of their vocalization, both in babbling and word utterances, already resembled the speech of adults in the two languages.

In one classic experiment, the behavior of 3-month-old babies was observed while they lay in their cribs. During two observation sessions, an adult experimenter leaned over the crib, at a distance of a little more than a foot from the child, and remained relatively motionless and expressionless. During this time, a second observer recorded the frequency of sounds produced by the infant. In two subsequent sessions, the procedure was the same, except that the first experimenter followed each non-crying sound with a "broad smile, three 'tsk' sounds, and a light touch applied to the infant's abdomen with thumb and fingers of the hand opposed" (Rheingold, Gewirtz, and Ross, 1959, p. 28). This is, of course, just:

R (babble) → S+ (smile, clucking, touch of abdomen)

The effect of this operant conditioning procedure was to raise the frequency of babbling well above its operant-level rate during these conditioning sessions.

Even more striking were the findings of Routh (1969), working with 2-to 7-month-old infants. Using the same reinforcing stimuli, he reinforced either vowel or consonant sounds rather than all vocalizations. He found that vocalizations increased under both conditions, but infants differentially increased the type of vocalization currently in the reinforced class. Experiments of this type provide ample evidence that human vocal behavior is susceptible to control by operant conditioning.

Operant conditioning is a phenomenon which is by no means limited to the simple animal and infant behaviors we have discussed so far. We study laboratory animals because we can rigorously control their environment, past and present, but operant behavior (behavior that can be modified by its consequences) constitutes a large proportion of the everyday activities of humans. When we kick a football, sew up a hem, give a lecture, discuss the latest in fashions, bemoan the weather, and wash the dishes, we are constantly emitting operant behavior. True, our complex skills entail much more complicated sequences than the simple repetitive loop of the rat, described earlier; but surprising complexity can also be generated in the behavior of the rat, cat, pigeon, and monkey (many examples are included in Leslie, 1996).

It is not difficult to demonstrate simple operant conditioning in humans in an informal manner: we can even perform demonstrations on our friends without great difficulty. For example, with "unaware" participants, it is possible to demonstrate that reinforcing certain topics of conversation, or the use of certain classes of words, by showing approval or agreement, will rapidly change the conversational speech of the participant. (We are apt to find the demonstration more dramatic and convincing if we prevent our human participant from "becoming aware" that we are performing such an experiment, because that seems to rule out the possibility that he or she is following an implicit verbal instruction, rather than "being conditioned"; verbal behavior is discussed in Chapter 6.) Nonetheless, the direct verification of the laws of operant conditioning on human behavior is important, for it shows that despite very great apparent differences between humans and other animal species, certain functional similarities exist, and it is these similarities that, in the end, justify our frequent reliance on the study of the behavior of other organisms.

For these reasons it is important that formal experiments on simple operant conditioning with humans be conducted, and many have been carried out. For example, Hall, Lund and Jackson (1968) measured the rates of study of six 6- to 8-year old children in class, who all showed much disruptive behavior and dawdling. When attention from the teacher was made contingent upon studying, there was a sharp increase in study rates. A brief reversal of the contingency, where attention occurred after non-studying, produced low rates of studying, and reinstatement of the contingency (studying → teacher attention) once again markedly increased studying.

This example of simple operant conditioning produced conspicuous changes in a highly complex form of behavior. A very different example of a dramatic effect of operant conditioning on human behavior is provided by the classic study of Hefferline and Keenan (1963). They investigated "miniature" operant responses involving a movement so small that electronic amplification must be employed to detect it, and the participant is generally not able to report observing his or her own responses. In one experiment, small muscle-twitch potentials were recorded from the human thumb. Dummy electrodes were placed at other points on the participant's body to distract attention from the thumb response. Introduction of a reinforcement contingency, in which small sums of money could be earned by incrementing a counter, led to an increase in very small thumb twitches, even when the participant was unable to say what the required response was.

One way of categorizing the Hefferline and Keenan experiment is as "conditioning without awareness"; it showed operant conditioning occurring without the participants being able necessarily to report verbally on the contingencies that were affecting behavior. This is an exception to what appears to be the usual situation, where we can verbalize the rule describing the contingency which is in operation. Indeed, once that verbal behavior occurs it generally seems to determine what nonverbal behavior will occur. A participant in a gambling game may, for example, decide that "The coin generally comes down 'heads'". If that behavior is reinforced by chance when the coin falls that way up on the first two occasions in the game, that verbal behavior may be highly persistent — and the person may always select 'heads' — despite many subsequent disconfirming events when the coin comes down as 'tails'. We will discuss the relationship between verbal and nonverbal behavior in later chapters and will see that there are complex relationships between the two. While it is often the case that rule following occurs, and the nonverbal behavior then seems to be insensitive to its consequences because it is controlled by the verbal behavior (such as the rule "The coin generally comes down 'heads'"), it is also true that this type of verbal behavior is itself quite sensitive to its consequences. That is, if formulations of the rule are reinforced — we might follow statements that "The coin is unbiased" with social approval, for example — this verbal behavior will change quite rapidly.

It is apparent from even a cursory examination of the world about us that some of the special consequences that we have been calling reinforcers have a more natural or biological primacy than others, and we have already noted that this led to Hull's (1943) theory that drive reduction was crucial to reinforcement. Food, water, and sex fall into a different, more "basic", category than books, money, and cars. Yet people, at one time or another, work for all of the things in the latter category. We can distinguish between these two categories by the manner in which a stimulus comes to be effective as a reinforcer. For each individual, there exists a class of reinforcers whose powers are a biological consequence of the individual's membership of a certain species. These reinforcers are as much a property of the species as are the leopard's spots, the cat's fur, the dog's tail. Possibilities of reinforcement which come built into the organism this way define the primary or unconditioned reinforcers, but there is also a second group of conditioned reinforcers, which appear more variable and less predictable from individual to individual than the primary set.

Money, cars, holidays, newspapers, prestige, honor, and the countless other arbitrary things that human beings work for constitute a vast source of reliable and potent reinforcers. But these objects and events have no value for us at birth. Clearly, they must have acquired their capacity to reinforce at some time during each individual's past history. A particular past history is a prerequisite; witness the occasional adult for whom some of the conventional reinforcers seem to hold no value. Moreover, gold has little importance for a Trappist monk, primitive man would hardly have fought for a copy of a best-selling novel, and not everybody likes Brahms. The context is also important: the business executive may enjoy a telephone call from a friend when work is slack, but be irritated by it occurring during an important meeting. Another way of putting this is that establishing operations (see Section 2.5) are important for conditioned as for unconditioned reinforcement.

While the importance of conditioned reinforcers is much more evident in human behavior than in the behavior of other species, the ways in which previously unimportant stimuli (lights, noises etc.) come to have conditioned reinforcing value have been extensively investigated in laboratory experiments with other animal species. It turns out that a relatively simple rule determines when a stimulus acquires conditioned reinforcing value: a stimulus acquires conditioned reinforcing value if it signals a reduction in the delay of (unconditioned) reinforcement (Fantino, 1977). Extrapolating this principle to human development, we would expect children to be reinforced by access to stimuli that signal forthcoming meal times, other treats, or a period of parental affection. Because the stimuli that have these functions vary from one child's experience to another's, we would anticipate that conditioned reinforcers vary in value from individual to individual.

The stimulus that seems to have most general properties as a conditioned reinforcer is, of course, money. Money has the culturally-defined property of being exchangeable for just about any other item: it therefore has the capacity to reduce the delay of many types of reinforcement. We can defined a generalized conditioned reinforcer as one that has acquired reinforcing value through signalling a reduction in delay (or presentation) of many primary reinforcers. Money fits this definition, but it is still not a perfectly generalized conditioned reinforcer, because we still tend to prefer some forms of money to others (Lea, Tarpy and Webley, 1987). Thus, we might prefer gold coins to notes, or refuse to put our money in the bank and keep the cash at home instead. These "irrational" habits presumably reflect the fact the reinforcing value of money is acquired and affected by details of the past histories of individuals. Generalized conditioned reinforcers are often used to increase adaptive behavior in applied or clinical settings (see Chapter 9).

Our definition of the simple operant conditioning paradigm (Section 2.6) stated that instances of an operant response class are followed by presentations of a reinforcing stimulus, but we have not yet provided a definition of response classes. One of the reasons that the science of behavior has been late in developing lies in the nature of its subject matter. Unlike kidney tissue, salt crystals or rock formations, behavior cannot easily be held still for observation. Rather, the movements and actions of organisms appear to flow in a steady stream with no clear-cut beginning or end. When a rat moves from the front to the back of its cage, when you drive 500 miles nonstop in your car, or when you read a book, it is difficult to identify points at which the continuous behavior stream can be broken into natural units. A further complication is that no two instances of an organism's actions are ever exactly the same, because no response is ever exactly repeated.

As a first step towards defining a response category, or response class, we might define a set of behaviors that meet certain requirements and fall within certain limits along specified response dimensions. This would be a topographically-defined response class, where topography is defined as specific patterns of bodily positions and movements. We can then check whether this response class meets the criterion of an operant response class by following occurrences of instances of the class with a reinforcing stimulus. If the whole class becomes more frequent, then we have successfully defined an operant response class.

Consider some examples. We might define the limits of a certain class of movements, such as those of the right arm, and attempt to reinforce all movements within the specified limits. If reaching movements then occur, are reinforced, and increase in frequency, we can conclude that reaching (with the right arm) is an operant. Words are prominent examples of the formation of culturally-determined response classes. All sounds that fall within certain acceptable limits (hence are made by muscular activity within certain limits) make up the spoken word "please". When a child enunciates and pronounces the word correctly, reinforcement is provided and the class of movements that produce "please" is increased in frequency. In both these cases, the reinforced operant class is likely to be slightly different from the topography originally specified.

In nature, it seems unlikely that reinforcement is ever contingent on a response class defined by topographical limits in the way just described. In the laboratory, reinforcement could be made contingent on a restricted subset of behaviors defined in that way. But even there, units are more usually approximated by classing together all the movements that act to produce a specified change in the environment. We call this a functionally-defined operant. It is defined as consisting of all the behaviors that could produce a particular environmental change, and thus have a particular function for the organism. It contrasts with a topographically-defined operant which, as we have seen, would be defined as consisting of movements that fall within certain physical limits.

The use of functionally-defined operants greatly facilitates analysis, because not only do such units closely correspond to the way in which we talk about behavior ("he missed the train" or "please shut the door"), but also measurement is made easier. When a rat is placed in a conventional Skinner box, it is easy to measure how many times the lever is depressed by a certain amount; it is much more difficult to record how many paw movements of a certain type occur. Similarly, it is fairly easy to record how often a child gets up from a seat in a classroom, but hard to measure the postural changes involved.

While we can alter the specifications of an operant for our convenience, it must be remembered that the only formal requirement of an operant is that it be a class of behaviors that is susceptible, as a class, to reinforcement. If we specify a class that fails to be strengthened or maintained by reinforcing its members, such a class does not constitute an operant response.

One of the most important features of operant conditioning is that response classes, as defined in the previous section, can change. Formally, this process is called response differentiation and its practical application is called response shaping.

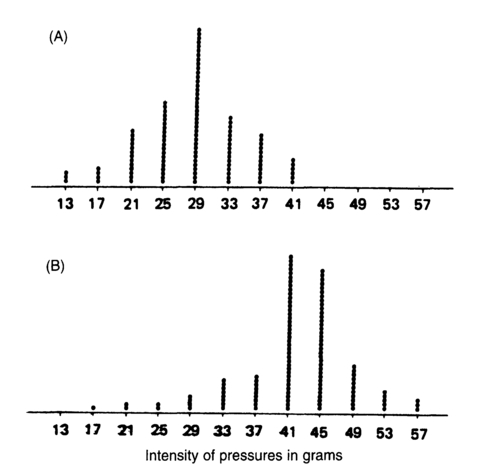

What we have defined as simple operant conditioning is a special case of response differentiation. Let us consider a case in which the specification of the behavioral class to be reinforced is in terms of a single behavioral dimension. In the definition of the lever press of a rat, the minimum force required to depress the lever can be specified. This minimum force is an example of a lower limit of a behavioral dimension. Hays and Woodbury (cited in Hull, 1943) conducted such an experiment, using a minimum force of 21 grams weight. That is, to "count" as a lever press, there had to be a downward pressure on the lever of 21 grams weight or more. After the conditioning process had stabilized, they examined the distribution of response force for a large number of individual responses. While many responses were close to 21 grams in force, there was a roughly symmetrical distribution with a maximum at 29 grams, or 8 grams above the minimum force required. The force requirement was then changed to a minimum of 36 grams. Over a period of time, the rat's behavior changed correspondingly, and the center of the distribution of response forces became 41 to 45 grams. Conditioning of this new class of behavior had thus been successful, but there had been a further important consequence of this conditioning. Novel emitted forces, never before seen in the animal's repertoire (those over 45 grams), were now occurring with moderate frequency. The results of the experiment are shown in Figure 2.6.

This differentiation procedure, where certain response variants are differentially reinforced, had resulted in the appearance and maintenance of a set of novel behaviors. This occurred through the operation of two complementary processes. At the time it was put into effect, the new requirement of 36 grams encompassed some existing forces which continued to be reinforced. Secondly, the 36-grams minimum requirement excluded many forces previously reinforced. When these responses were emitted under the 36-grams minimum procedure, they were subjected to extinction, which is discussed in the next chapter. Extinction is the procedure of removing reinforcement from a previously reinforced class of behavior. It has the principal effect of reducing the frequency of occurrence of that class, and it also increases response variability.

Figure 2.6 Distribution of response forces when (A, upper graph) all responses with a force of more than 21g were reinforced, and (B, lower graph) when all responses with a force of more than 36 g were reinforced (after Hays and Woodbury, cited in Hull, 1943).

The great power of the response differentiation procedure, when used with a changing series of response classes, lies in its ability to generate and then sustain behaviors hitherto unobserved in the person's or animal's repertoire. This power is extended very much further in cases in which progressive and gradual differentiations can be made to take place over time. We call this method of introducing new behavior into the repertoire response shaping by successive approximation. By such a process of successive approximation on the lever-force dimension, Skinner (1938) was able to train 200-gram rats to perform the Herculean feat of pressing a bar requiring a 100-grams minimal force! A better-known example from human behavior is the record time for the 100 meters race: a time that would have been the world record in 1950 is now routinely improved on by athletes in training. We can think of this as a skilled performance that has been shaped within individuals, and passed on by other means between individuals.

Response shaping by successive approximation has a straightforward and very important use in the operant-conditioning laboratory. Suppose an experimenter wishes to reinforce the pecking of a wall-mounted key or disk by pigeons with food. This response often has zero operant-level frequency (that is, prior to training it does not occur at all) and thus must be shaped. The experimenter successively approximates the desired form of the behavior, beginning with a form that may not resemble key pecking at all. For example, all movements in the vicinity of the key may first be reinforced. Once these movements have increased in relative frequency, reinforcement is made contingent on head movements directed towards the key. Once such movements are frequent, reinforcement is made contingent upon striking the key with the beak, and finally, upon depressing the key with the beak. The process of introducing a response not previously in the repertoire can be very easy or very difficult. The degree of difficulty experienced probably reflects the preparedness of the organism to associate the specified response and reinforcer as well as the stringency of the response differentiation required by the experimenter.

Response shaping is a highly important technique in the application of behavioral analysis to human problems. Many such problems can be characterized as behavioral deficits: the individual concerned does not succeed in making "normal" responses and thus his or her behavior is not maintained by the social consequences that influence the behavior of others. Stuttering, for example, may prevent the individual from routinely engaging in conversation with others. Howie and Woods (1982) successfully used a shaping procedure to produce and increase fluency of speech in adult stutterers. Participants were reinforced in each session of training if they met the currently required rate of stutter-free speech, if they avoided stuttering, and if they completed a target number of syllables using a continuous speech pattern. If they were successful, the required rate of stutter-free speech was increased by 5 syllables per minute for the next session, until a rate of 200 syllables per minute was achieved. Shaping adaptive responding in applied or clinical settings will discussed in greater detail in Chapter 9.

We can provide a scientific account of the types of behavior described as "purposive", but the first step is to recognize that such behavior is influenced by its previous consequences. A hungry pigeon in an operant test chamber, or Skinner box, will peck at the response key because this behavior has previously been followed by food presentation.

Skinner advanced the study of such behavior by deciding to use rate of response as a measure, and by devising the Skinner box within which laboratory animals can emit responses from time to time. If a contingency, or relationship, is arranged between an emitted response and a reinforcing consequence, then a number of characteristic behavioral changes ensue and we say that operant conditioning has occurred. These changes include an increase in response frequency, the sequential organization of behavior, reduction in response variability, and reductions in other (non-reinforced) behavior.

Operant conditioning will only occur when the stimulus made contingent upon the operant response acts as a reinforcer. The property of being a reinforcer, or reinforcing stimulus, is not inherent in a stimulus. Rather, it depends upon the state of the organism and the environment at the time. Operant conditioning will occur if the organism is currently deprived of its preferred rate of access to the reinforcer and if occurrence of the operant response results in an increase in that rate of access. Food is thus a reinforcer for key pecking by a hungry pigeon because the current preferred rate of feeding is very high, and delivery of food as a reinforcer increases the actual rate of feeding towards that preferred rate. In this example, food deprivation is an establishing operation that ensures that operant conditioning will occur in the experiment.

There are many interesting demonstrations of operant conditioning with humans. These include studies of vocalization by infants and of very small movements in adults. The latter example is important because the operant response classes increased in frequency even though the participants in the experiment were unaware of the particular response required.

Human behavior is much affected by conditioned reinforcement. That is, behavior is changed when the consequence is a stimulus with a function that has been established through the previous experience of the individual. The most potent example of a generalized conditioned reinforcer is money, but other conditioned reinforcers (such as a liking for a particular type of music) will be specific to the individual and result from their own particular history.

We tend to assume that behavior, or response classes, should be described topographically, or in terms of the bodily movements involved. In fact, operant conditioning generally involves functional response classes, in a functional response class, all the members have a particular effect on the environment. Examples of this type of functional class are a pigeon pecking at a key mounted on the wall or a person writing a series of words. Operant response classes can be established through response shaping. This is necessary when the initial behavioral repertoire does not include the required response. In the shaping process, successively closer approximations to the required response are reinforced. The outcome is a change in the behavioral repertoire to include the desired response.